This chapter first compares the statutory accessibility and generosity of Unemployment Insurance in the United States to other OECD countries, taking state‑level differences in design into account. It then looks at the statutory entitlement to Unemployment Insurance for current workers, and jobseekers, in the United States. It analyses the reasons for non-entitlement, and how they influence statutory access to Unemployment Insurance for workers and jobseekers of different socio‑economic, including racial and ethnic, groups, as well as men and women. It then examines how the pandemic-related extensions to UI would affect statutory entitlements if kept in place in a non-pandemic labour market, and how they would affect household incomes and poverty.

Benefit Reforms for Inclusive Societies in the United States

2. Accessibility of unemployment insurance in the context of recent extensions

Abstract

2.1. Introduction

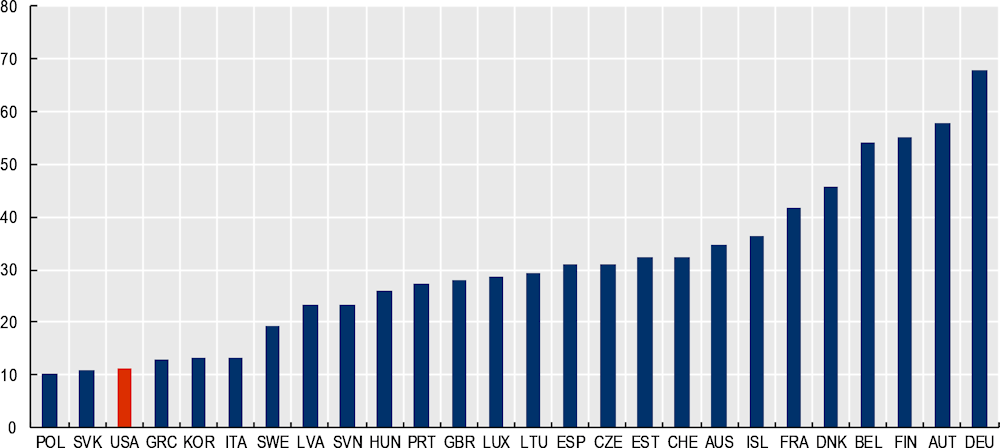

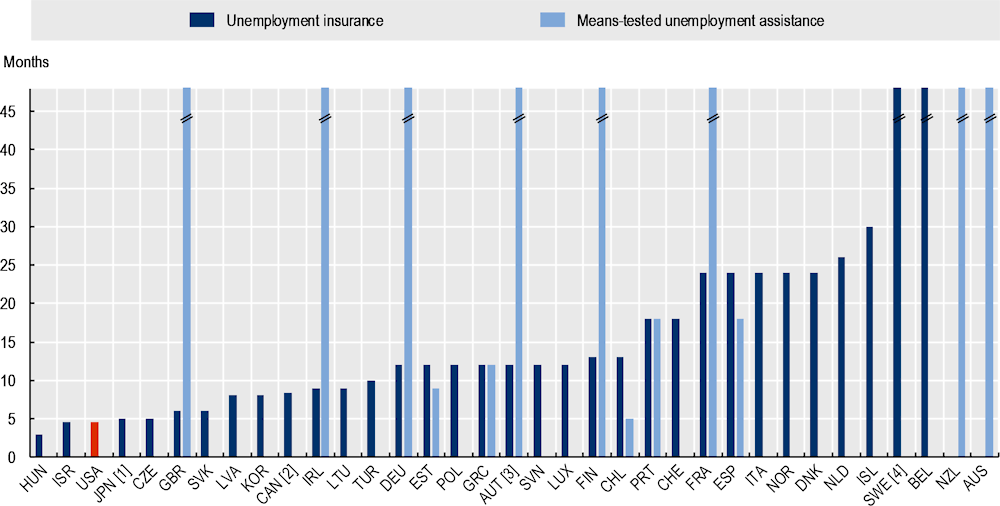

Prior to the onset at the COVID‑19 pandemic, the coverage of unemployment insurance (UI)1 benefits in the United States was lower than in most other OECD countries: 11% of all US jobseekers received benefits in 2016, compared to about 30% in the United Kingdom, Spain or Australia, and around 60% and over in Austria and Germany (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. About one in eight unemployed workers receives unemployment benefits in the United States

Share of unemployed workers receiving unemployment benefits, 2019 or latest available year

Notes: “Unemployed” refers to the standard ILO definition, i.e. out of work, actively looking for work, and available to start work. Some European countries are excluded due to missing information in EU Labour Force Survey data. 2015 figures for Australia, 2018 for the United States. LFS data for Sweden do not include a series of benefits that are accessible to jobless individuals who: i) are not in receipt of core unemployment benefits, and who ii) satisfy other conditions such as active participation in employment-support measures.

Source: KLIPS for Korea; Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) for Australia; European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) for European countries, CPS for the United States.

A number of factors contribute to these cross-country patterns. Statutory benefit durations in the United States are comparatively short in “normal” times, though they may be extended during downturns. Between 2011 and 2016, nine states cut the maximum duration of unemployment benefit receipt. Partly as a result, US coverage rates fell by a quarter between 2007 and 2016 (Wentworth, 2017[1]). Other possible reasons for a downward trend include an increase in the number of discontinued claims, with a rising number of recipients who had their benefits stopped because they fail to comply with behavioural requirements such as active job-search. It might also be connected to increased funding pressures and new IT-based claims administration systems in some states, that may be difficult to navigate for some claimants (Vroman, 2018[2]; Congdon and Vroman, 2021[3]; Wentworth, 2017[1]). Another reason for comparatively low coverage in the United States is that voluntary quits generally do not confer entitlement to UI.2 Although entitlements in other countries can also be restricted in the case of voluntary quits, a majority of countries do not disqualify jobseekers outright but instead reduce or delay payments.

This chapter first examines the statutory reach and generosity of unemployment compensation for US workers and jobseekers, with a particular focus on disadvantaged labour market groups, such as racial and ethnic minorities, women, and non-standard workers. It then simulates how the pandemic-related extensions to UI (phased out in late 2021), if kept in place, would affect statutory eligibility and generosity in a non-pandemic labour market. The assessment of statutory entitlement seeks to identify aspects of the current UI design that translate into low UI receipt rates. It does so by looking at employment circumstances that may drive non-eligibility (e.g. past self-employment, low earnings, or short employment histories), and at jobseeker characteristics that may be associated with these employment and earnings patterns (e.g. gender, race or ethnicity). The chapter’s results on statutory entitlement can be seen as an upper bound of de facto coverage, as those entitled to receive UI might not receive it in practice due to non-take up, cross-group differences in the administration of benefits (e.g. due to discrimination), or non-compliance with behavioural requirements. Patterns of de facto UI receipt are analysed in Chapter 1.

As most OECD countries, the United States significantly shored up income support following the initial shock of the COVID‑19 pandemic. The substantial extensions, in particular the US Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), allowed unemployment compensation to absorb the bulk of pandemic-related income losses. At the hight of the pandemic, 16% of working-age Americans were in receipt of unemployment benefits (see section 2.5). Emergency measures greatly increased both coverage and the generosity of payments. Their direct effects were largely progressive as job-losses were concentrated in low-wage service industries (Ganong, Noel and Vavra, 2020[4]). These changes took place in the context of pandemic-related job losses whose scale and pace were unprecedented. They were also highly concentrated in sectors, workplaces and jobs that were contact-intensive and deemed non-essential. The effects of the extensions therefore do not carry over to a non-pandemic labour market, with a very different level and distribution of unemployment risks. The second part of this chapter therefore employs a simulation approach to quantify the potential of PUA-type extensions to strengthen the reach of UI, alter its generosity, and tackle income insecurity and poverty, in a labour market that is less exceptional, and not impacted by a pandemic.

Both parts of the analysis use representative micro-data from the Survey of Income and Programme Participation (SIPP), with individual-level information on employment histories and earnings. It employs a (partial) simulation approach that applies detailed, state‑level policy rules to determine entitlements to unemployment compensation, both before the pandemic extensions (policy rules of 2016) and after it (policy rules of 2021). The simulations account for individuals’ work and earnings histories as well as their state of residence. The simulation approach permits determining not only who is or is not eligible for UI, but also the reasons for non-entitlement.

The chapter is structured as follows: Section 2.2 describes the simulation method. Section 2.3 summarises the principal institutional design features of the UI system at the state level, and benchmarks it against the designs used in other OECD countries. Section 2.4 analyses drivers of differences in UI entitlement between socio‑economic and ethnic groups. Finally, section 2.5 simulates the consequences of the PUA extensions for UI accessibility and poverty in a pre‑pandemic labour market.

2.2. Simulating entitlement to unemployment compensation

The (partial) UI simulations used for this analysis determine the statutory coverage (who would be entitled?) and the generosity (how much would they receive?) of unemployment compensation in the United States at the individual level, using information on individual labour market history and previous earnings, as well as state of residence, from microdata. The methodology is similar to (Kuka and Stuart, 2021[5]), but does not limit the scope to recent job separations – instead, the simulation sample includes those currently in employment, as well as jobseekers without a recent labour market history.

The simulations combine policy rules for 50 states and the District of Columbia with individual-level survey microdata to determine workers’ legal entitlement to UI: receipt (yes/no) and amount. The simulations consider individuals’ labour market history, earnings and state of residence. They therefore account for key factors driving people’s UI benefit receipt. They do, however, disregard factors affecting unemployment compensation payments in practice, such as sanctions following non-compliance with behavioural requirements after entitlement was established (e.g. active job search or participation in training programmes). Individuals who would be legally entitled to receive support might also not claim it for a number of reasons, such as information gaps, the (perceived) complexity of the claims process, real or perceived discrimination in the administration of claims, or social stigma associated with benefit receipt. Indeed, international empirical evidence has found take‑up rates for UI ranging between 60% and 80%, see (Hernanz, Malherbet and Pellizzari, 2004[6]) and (Blasco and Fontaine, 2021[7]) for evidence on Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States and (Kuka and Stuart, 2021[5]) for the United States. Thus, while legal entitlement is a key condition for access to UI, simulations of statutory UI entitlement constitute an upper-bound estimate of UI coverage in practice (see section 2.4.1). They can be complemented by indicators of de facto receipt, as described in Chapter 1.

The simulations look, in turn, at two distinct populations, leading to two different sets of questions and answers:

1. Working individuals. What UI benefits would current workers be entitled to if they became unemployed during the observation period? This approach assesses the general capacity of the system to provide income protection for all groups of workers, regardless of their actual risk of facing joblessness. For instance, it includes those with a low unemployment risk in “normal times”, but who might be affected by future crises.

2. Unemployed individuals. This approach examines the accessibility of UI, and the values of UI entitlements, for those workers who actually were unemployed during the observation period. It therefore accounts for the specific unemployment risks of different population groups, e.g. distinguishing by race/ethnicity, gender, previous standard/non-standard work and educational attainment.

This two‑pronged strategy therefore probes two different aspects of the UI system: 1) its ability to insure all workers in the event of job loss, and 2) the actual level of support it provides to those actually experiencing unemployment. Looking at entitlement at the individual level allows zooming in on disadvantaged labour market groups, including women, racial minorities, low-educated workers, those with a history of self-employment, etc.

The analysis is based on a representative sample for the US labour force in the year 2016 (the fourth wave of the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation, SIPP, see Annex 2.A for descriptive statistics). The SIPP, designed for monitoring programme participation, provides detailed information on incomes and benefit receipt, and the 2014 panel tracks participants over four years, allowing the simulation of long benefit extensions such as PUA.

Calculations rely on state unemployment insurance laws published by the Department of Labor (US Department of Labor, 2016[8]), supplemented by state legal codes and administrative documentation when additional information was required. The simulations comprise statutory eligibility and benefit rules for each of the 50 US states plus the District of Columbia. They assume that benefit receipt starts in the first month of unemployment, and continues until either the maximum entitlement period ends, a new job starts, or the jobseeker discontinues looking for a job (e.g. to pursue further education/training).

Simulation (i) for working individuals assesses statutory entitlements for all individuals who are currently working (at least one hour per week for pay or profit, that is including self-employed workers, following the ILO definition) if they were to involuntarily lose their job. Simulation (ii) for unemployed individuals assesses statutory entitlements for all individuals who are currently unemployed (out of work, actively looking for work, and available to start work, again following the ILO definition). Box 2.1 summarises the key steps of the simulation.

Box 2.1. Individual-level simulations of (statutory) UI entitlement: methodological choices

Simulations are based on the 2014‑16 panel of the Survey of Income and Programme Participation. The sample includes all working-age individuals (aged 18 to 64) in the year 2016 with a complete labour market history (three years of monthly employment status information and non-missing earnings) who have not taken early retirement.1 To correct for seasonality, the simulations determine eligibility to UI for each month in 2016 and average across months.2.

Part-time workers are wage and salaried workers working below 35 hours per week. Self-employed workers include workers in the residual category of “other work arrangement” according to guidance from the Census Bureau that these workers are mostly independent contractors or consultants. Workers who are wage and salaried workers as well as self-employed are categorised as self-employed if their earnings from self-employment in a given month are higher than their wage or salaried income (and vice‑versa). For individuals with missing earnings the simulations use the number of hours worked as either a wage or salaried worker or as self-employed to determine the primary status. Because some workers combine self-employment with wage and salary income (2% of working individuals, or 20% of all self-employed individuals, in the SIPP 2016 sample), some (mainly) self-employed workers fulfil the eligibility requirements for UI.

Sample 1: Working individuals

The working individuals approach looks at statutory eligibility for UI for all individuals who are currently working according to the International Labour Organization (ILO) definition of at least one hour work per week for pay or profit (this includes self-employed workers) if they lost their job involuntarily (since voluntary job separations do not give rise to UI entitlement). For simplicity, the simulation assumes that multiple jobholders lost all of their jobs.3.

Sample 2: Unemployed individuals

The unemployed individuals approach looks at UI eligibility for all individuals who are currently unemployed according to the ILO definition of not working and actively looking for work and being available for work in a given week.

The simulations assume that individuals are eligible for UI (if they fulfil the relevant state‑level eligibility conditions) from the moment of job loss until the maximum duration of unemployment compensation is exhausted. For example, individuals losing their job involuntarily in May 2016 with a maximum UI duration of up to five months would be defined as eligible for UI for the months June‑October 2016. For simplicity, the simulations assume that eligible individuals receive UI payments starting in the month after they separated from their job without any interruptions. They are eligible up until they exhaust their maximum benefit duration or start another job. While some individuals may only start claiming benefits at a later point in time, this cannot be identified in the data.

The SIPP contains survey information on whether a job separation was voluntary or involuntary – workers who left their jobs voluntarily are assumed to not be entitled to UI. Note that there are cases where voluntary job-leavers are also entitled to UI, however, these cannot be identified from the survey data.4.

The simulations do not restrict eligibility to individuals who have been continuously looking for work since they quit their last job. Individuals who leave the labour force for a period of time (i.e. are not actively looking for a job) and later starting to actively look for work are considered as potentially eligible for UI. Again, the simulations use the date of separation from their last job as a reference to determine eligibility. That is, if a worker loses her job in January, but only starts actively looking for work in March, she is not in the sample in the month of February, as she is not ILO unemployed. She re‑joins the sample in March, but her (simulated) maximum receipt period still starts in February.

Some states exclude individuals with positive earnings from UI receipt. As the simulation sample is restricted to unemployed workers who by definition do not work for pay or profit, this does not influence the simulations. Only one percent of unemployed individuals in the sample report positive earnings, and 80% of them do so only in the first month of their unemployment, indicating that these are related to their previous job (back payments, leftover annual leave etc.).

1. Early retirees are those who have received any retirement income within the past year.

2. The sample also excludes a small number of observations that report negative annual income.

3. See Annex 2.B for details on voluntary separations.

4. E.g. workers who leave their jobs because they face discrimination or sexual harassment at work are entitled to UI in most states, see also section 3.2.

2.3. Unemployment insurance: Accessibility and generosity in US states and internationally

The UI system in the United States is decentralised – states determine minimum earnings thresholds, maximum durations and benefit levels, and administer payments. While each state is free to design its own programme, the federal government provides tax incentives to employers in states whose systems fulfil certain minimum requirements set out in federal legislation (US Department of Labor, 2019[9]). Unemployment compensation is funded by employer contributions. Some States use a system of experience rating, with employers with a history of more frequent dismissals paying higher contributions. Contribution rates vary widely across states, with rates between 0.1 to 5.4 percent of the first USD 7 000 of an employee’s earnings. In periods of high unemployment, when contributions are insufficient to cover benefits, states usually increase rates (US Department of Labor, 2021[10]).

State‑level UI programmes cover most wage and salaried workers,3 including railroad workers, federal employees, and recently active military service members. Self-employed workers are not covered by UI (with the exception of PUA extensions).

2.3.1. Minimum earnings requirements differ across states …

All states establish entitlement by assessing previous earnings over the five quarters preceding a job loss (the so-called base period). However, actual minimum earnings requirements differ quite substantially across states. Many state rules stipulate minimum earnings conditions for either the highest-earnings quarter, or for the base period as a whole.4 In addition, states often require earnings to be at least somewhat evenly distributed across the base period and/or to exceed a certain multiple of the minimum unemployment benefit. Some states require claimants to have worked a certain minimum number of weeks or hours.

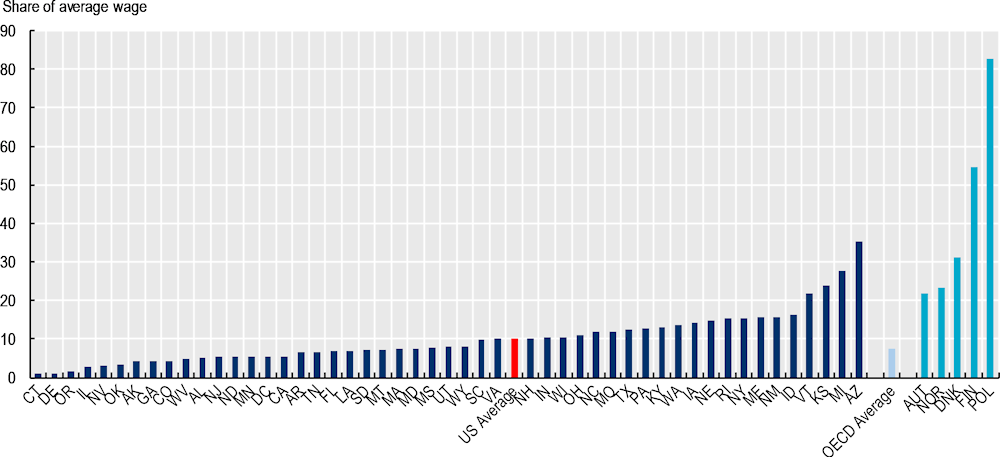

For claimants with a continuous work history over the entire base period, minimum earnings requirements vary enormously, ranging from 1% of the state‑level average wage in Connecticut to 35% in Arizona (Figure 2.2). In contrast, most OECD countries do not operate minimum earnings requirements at all, either because workers qualify if they satisfy the minimum contribution periods (regardless of earnings) or because their out-of-work support programmes are entirely means-tested and therefore independent of past employment and earnings (e.g. Australia or New Zealand, see (Hyee, Fernández and Immervoll, 2020[11]). Indeed, in 2020, and in addition to the United States, only 5 of 33 OECD countries with available information had a minimum earnings threshold for UI in place. For countries that do have minimum earnings requirements, thresholds tend to be higher than in most US states, e.g. 22% of the average wage in Austria, or 54% in Finland (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2. Minimum earnings thresholds differ across states

US states and selected OECD countries, 2020

Notes: Minimum earnings that give rise to UI entitlement, as a share of the state‑ or country-level average wage. US states: jobseeker living alone with constant earnings over the base period. Other OECD countries: 40‑year‑old jobseeker living alone with a stable and “long” contribution history at the average wage. OECD average includes countries with zero minimum earnings requirements.

Source: OECD calculations based on the US Department of Labor’s comparison of state UI laws: https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2020/complete.pdf, OECD tax-benefit model (version 2.4.0) for other OECD countries: http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

2.3.2. … but minimum contribution periods are similar across states, and short when compared to other countries

For jobseekers with low to average earnings, three months of continuous wage or salaried employment is sufficient to qualify for unemployment compensation in 12 US states, and six months in all states (Figure 2.3). This is a relatively short contribution period compared to other countries – in the United Kingdom, at least two years of contributions are required to receive the contribution-based new-style jobseeker’s allowance, although jobseekers who do not fulfil this requirement may claim (means-tested) Universal Credit (see Box 3.3). Similarly, in Germany, the minimum contribution period for the first-tier “unemployment benefit I” (Arbeitslosengeld I) is 12 months, but jobseekers who do not meet this requirement may access the means-tested unemployment assistance “unemployment benefit II” (Arbeitslosengeld II, see Box 3.4).

Figure 2.3. Two quarters of earnings are enough to receive benefits in all states

Minimum contribution period for UI eligibility in US states and other OECD countries in months, 2020

Notes: (1) And at least 30 days of employment in the 12 months prior to the start of the unemployment spell; (2) Or 200 days in last two years; (3) Assuming 40 hour work week; (4) 6 months in any one of the past two years. (5) Must also have been a member of the insurance fund for at least 12 months; (6) or 26 weekly contributions in each of previous two years. Must also have made 104 weekly contributions in whole career; (7) 28 weeks in the case of repeated unemployment; (8) Must also have been continuously with the employer for last 120 days. The 12 US states with only three months (one‑quarter) of required minimum contributions are: CA, CO, CT, DE, GA, MN, MA, NJ, OK, RI, WA, VA. While the reference period is 15 months for all US states, some US states provide for alternate base period calculation which can result in a reduced reference period of 12 months if that is more beneficial to the individual.

Source: OECD calculations based on the US Department of Labor’s comparison of state UI laws: https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2020/complete.pdf; other OECD countries: OECD TaxBEN model (version 2.4.0) http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

2.3.3. State‑level differences in statutory rules do not lead to big differences in UI accessibility …

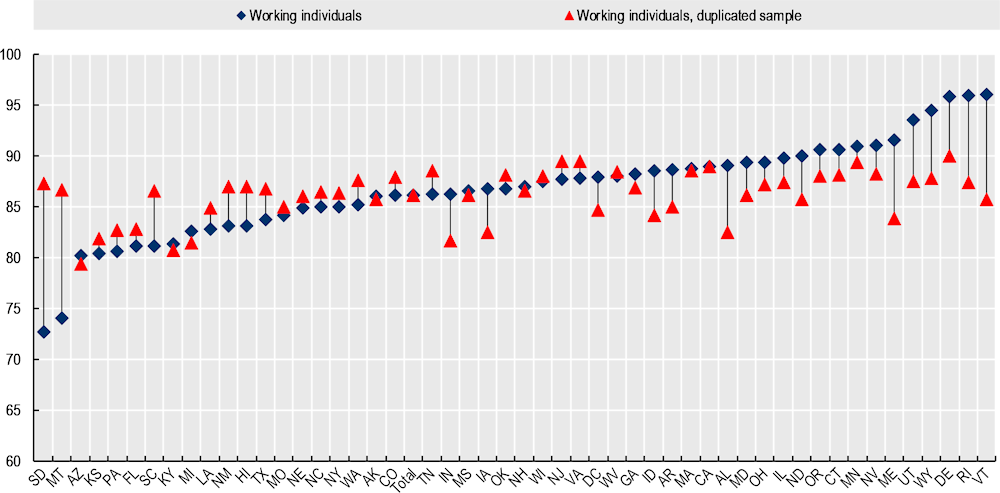

The share of current workers who would be entitled to UI in the event of an involuntary job loss ranges from 73% in South Dakota to 96% in Vermont (Figure 2.4, blue series).5 These differences are mostly due to differences in the composition of workforces across states, in terms of employment form, earnings levels and employment stability, as opposed to statutory rules. To see this, and following (Kuka and Stuart, 2021[5]), an alternative simulation strategy applies the UI statutory rules of each state to the entire US workforce – that is, it simulates statutory coverage as if the UI system of each state applied to all US workers. This controls for differences in workforce characteristics and enables a focus on state‑level statutory rules. Using this “duplicated sample” simulation approach, cross-state differences diminish significantly: statutory coverage under this scenario ranges from 79% in Arizona to 90% in Delaware (Figure 2.4, red series). Overall, only about a quarter of the variance in statutory coverage across states are directly due to states’ different entitlement rules, while 73% can be explained by cross-state differences in workforce composition. For instance, high statutory coverage in Vermont is mostly due to the low incidence of self-employment in the state, whereas 20% of current workers are self-employed in South Dakota.

Figure 2.4. Labour force composition accounts for most of the cross-state variation in UI coverage upon job loss

Share of working individuals eligible for unemployment compensation by state (2016), in percent

Note: Simulated statutory UI coverage among all workers in each state if they were to lose their job during the observation period. “Total”: unweighted average across shown states. “Duplicated sample”: simulated statutory UI coverage applying each states’ statutory policy rules to the entire working-population across the United States, after adjusting for differences in average earnings by state. The approach isolates the effect of policy rules on coverage abstracts from differences in workforce composition by state.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

2.3.4. … but cross-state differences in generosity are significant

Most states employ the so-called “high-quarter” method to determine benefit amounts as a function of claimants’ earnings in their highest-earning quarter during the base period. Some states instead calculate benefit amounts relative to total earnings over multiple quarters, relative to annual wages or relative to average weekly wages.

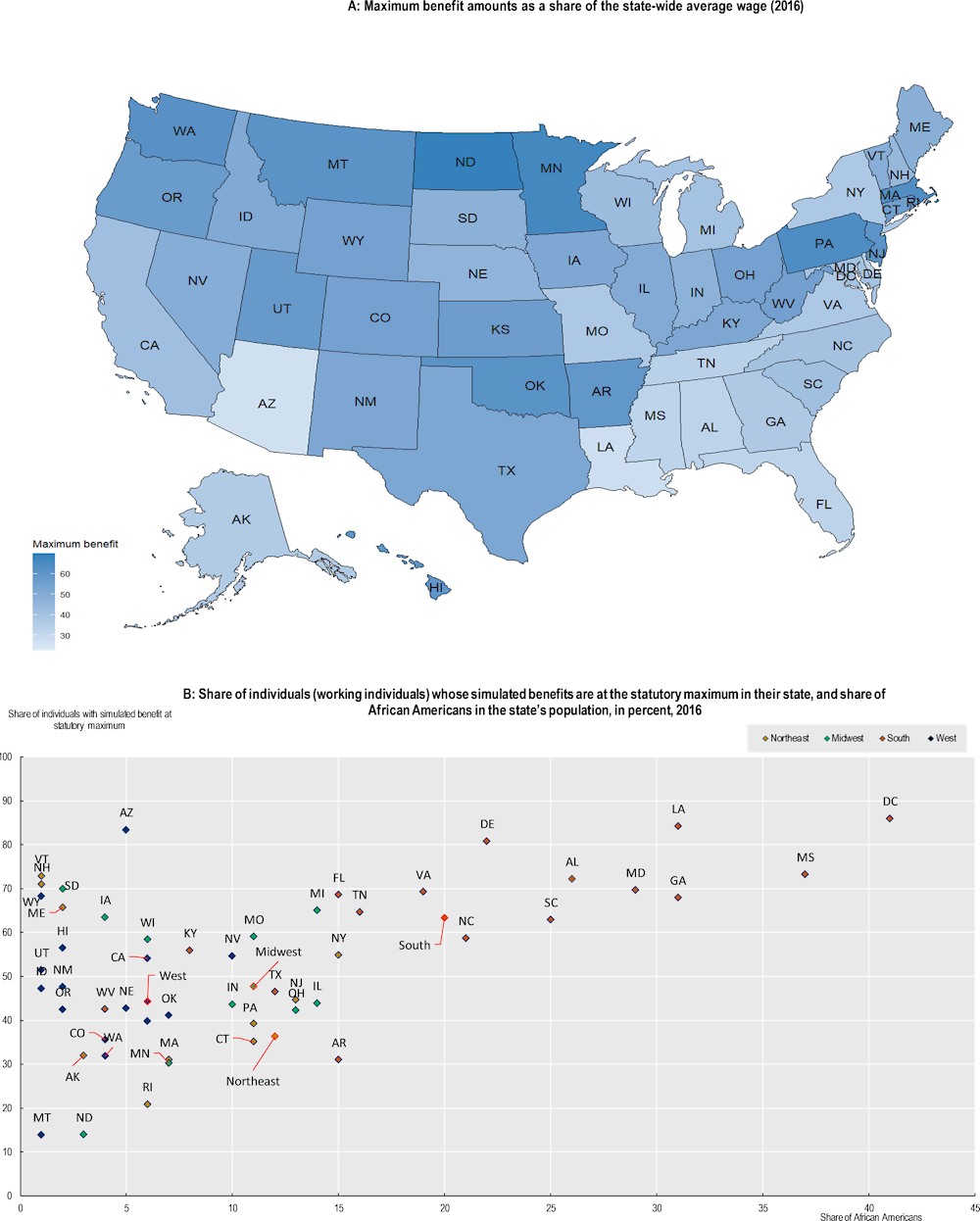

Effective maximum benefit amounts vary widely across states, from below 30% of the state‑wide average wage in Washington D.C., Arizona and Louisiana to 70% in North Dakota. (Figure 2.5, Panel A). Southern states, where the population share of African Americans is higher, offer comparatively modest benefit ceilings. Indeed, the share of workers for whom the maximum benefit would be binding ranges from under 15% in Montana and North Dakota to over 80% in Louisiana and Washington, DC (Figure 2.5, Panel B). Lower potential entitlement amounts in Southern states could be one factor behind the lower take‑up of unemployment compensation among African Americans (Kuka and Stuart, 2021[5]).

Figure 2.5. UI benefits are more generous in the northern states

Notes: Panel C: Average worker, working individuals: average benefit amount calculated over all full-time workers (working individuals). US and OECD average are unweighted. OECD countries: full-time worker at the average wage without dependents.

Source: Panel A: (US Department of Labor, 2016[8]), Comparison of State Unemployment Laws 2016, http://www.oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/statelaws.asp#Statelaw.Other.

Panel B: OECD calculations based on SIPP 2014 and Census Bureau 2020 data (share of African Americans in State population, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/IPE120221).

Panel C: United States: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). Other countries: OECD Tax-Benefit Policy Database, http://oe.cd/TaxBEN

On average across the US, gross replacement rates for full-time workers at the average wage are 39%, compared to 45% for the OECD average (Figure 2.5, Panel B).6 Several high-income countries such as France and the Netherlands have gross replacement rates of 50% and higher. This implies comparatively low income security for workers with average to high incomes in many states.

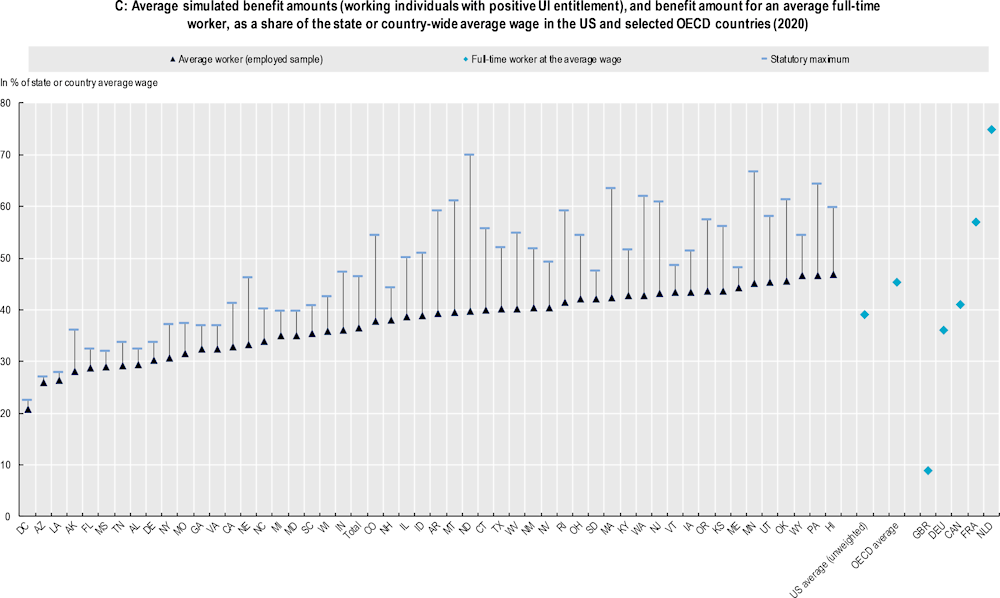

2.3.5. Benefit receipt durations are short in international comparison

Maximum benefit durations vary by state. Some states have flat duration limits for all claimants (in 2021, ten states provided benefits for a flat 26 weeks and North Carolina offered a maximum of 12 to 20 weeks depending on the state’s unemployment rate). Others tie receipt durations to claimants’ work and earnings history, sometimes in combination with the state’s unemployment rate. For claimants with the lowest past contributions, maximum durations are shortest in Washington (one week) and Oregon (three weeks), with most states providing a minimum of eight to 14 weeks. However, even for claimants with the most contributions, maximum receipt durations only exceed 26 weeks in Massachusetts (30 weeks in periods of high unemployment) and Montana (28 weeks for individuals with the highest past contributions). In 2021, 44 states provided benefits for a maximum of 26 weeks (US Department of Labor, 2021[10]). In addition to the regular UI benefit there is an Extended Benefits (EB) programme which extends benefit eligibility by 13 weeks when a state experiences high unemployment.7 In 2016, the reference year for the simulations, benefits were not extended in any state.8

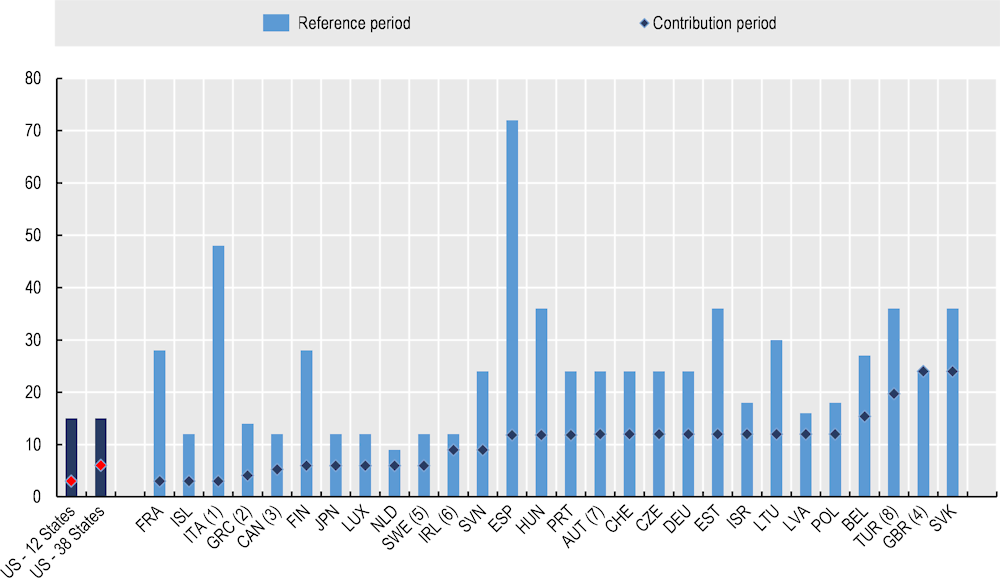

Compared to other OECD countries, maximum benefit durations in the United States are low. On average across 33 OECD countries operating contribution-based unemployment benefits, the maximum benefit duration is 17 months (Figure 2.6). In addition to unemployment insurance benefits, 12 countries have unemployment assistance programs in place that provide means-tested payments to unemployed individuals who have exhausted their UI benefits and, sometimes, to those who were not entitled to UI (where it exists) in the first place.9

Figure 2.6. Benefit duration limits are amongst the lowest in the OECD

Maximum duration of unemployment benefits, 2020

[1] Claimants deemed to be difficult to re‑employ may receive up to 360 days of unemployment benefits. [2] The maximum benefit duration is determined by the regional unemployment rate. The estimated maximum duration shown here is based on the national unemployment rate for December 2019. [3] The unemployment assistance programme in Austria is contribution-based and not means-tested. [4] After 300 days of UI benefit receipt, recipients are referred to the “Job and Development Guarantee” programme, which combines activation measures and income support without pre‑defined duration.

Note: Unemployment benefits as of 1 January 2020, 40‑year‑old with a “long” employment record with past earnings of 2/3 of national average wage. Benefit durations in the United States vary by State and unemployment rate. For example, the maximum benefit duration in California varies between 14 and 26 weeks depending on wages earned during the base period. Higher wages generally result in longer maximum durations. The 20‑week benefit duration shown for the United States refers to Michigan.

Source: OECD Tax-Benefit Policy Database, http://oe.cd/TaxBEN

2.4. Accessibility gaps and their drivers

As discussed in section 2.2, this chapter analyses statutory UI coverage, as opposed to de facto (empirical) coverage. In other words, it focuses on the effect of state‑level policy rules, abstracting from the implementation of these rules or the propensity of otherwise eligible jobseekers to apply for benefits. Before turning to the chapter’s main results, section 2.4.1 discusses other factors influencing benefit receipt.

2.4.1. Take‑up, benefit sanctions and the claims process

Estimates of the share of eligible jobseekers who actually claim unemployment benefits range between 30% and 70% depending on the country and data source (Blasco and Fontaine, 2021[7]). Non-take‑up of benefits can be caused by information gaps, language‑ and other barriers to putting in a claim, real or perceived discrimination in the claims process,10 and social stigma associated with benefit receipt.

But non-take‑up can also be connected to a low expected value of benefits (caused by low weekly payments, jobseekers expecting to find a new job quickly, or a low maximum benefit duration). Indeed, (Anderson and Meyer, 1997[12]) show for the United States that a 10% increase in the weekly amount of unemployment benefits would increase the take‑up rate by 2‑2.5 percentage points, whereas a 10% increase in benefit receipt duration would increase take‑up by 0.5 to 1 percentage point. Increasing the value of unemployment benefits may therefore not only increase benefit payments mechanically but may also increase the rate at which they are claimed.

In the United States, take‑up seems to be an important driver of racial differences in UI receipt rates. Examining UI receipt between 1986 and 2015, Kuka and Stuart (2020[13]; 2021[5]) find that only 42% of eligible African Americans take up UI, compared to 55% of white jobseekers. About 30% of this gap is explained by African American jobseekers’ lower pre‑unemployment earnings (leading to lower benefit amounts). The fact that African Americans are much more likely to live in the South where benefits are a lot less generous (see section 2.3) explains a further 20% of this racial gap. Similarly, (Skandalis, Marinescu and Massenkoff, 2022[14]), using administrative data on UI claims, find that African American jobseekers have an 18% lower replacement rate than their white peers, with 10% of this gap explained by differences in work history, and the remainder by differences in state‑specific entitlement rules. This implies that raising benefit entitlements in the South to levels comparable to the rest of the country would not only increase benefit payments, but also strengthen coverage, as well as job-search, training and other activation measures that are tied to benefit receipt. Such changes would disproportionally benefit African American jobseekers.

Otherwise eligible benefit claimants may also be denied benefits for non-compliance with behavioural requirements, such as active job-search. Such sanctions are a design feature of many UI systems across the OECD, and they are often partial, e.g. reducing or delaying entitlements rather than precluding or stopping them completely (see http://oe.cd/ActivationStrictness). In practice, benefit denials can also be unintended, e.g. if they are connected to specific aspects of the administration of benefit claims or a transition to new assessment processes. For instance, Oklahoma introduced a new online system in 2014 as part of a state effort to reduce unemployment durations, requiring jobseekers to register online and upload a CV within seven days of putting in a claim for benefits. While the requirement to register with the PES had been in place before, it was not stringently enforced until the introduction of the new online system. Many claimants struggled with the new system and sought assistance in PES offices. In the year after the system’s introduction, claims denied for not satisfying reporting requirements increased more than three‑fold (Wentworth, 2017[1]).

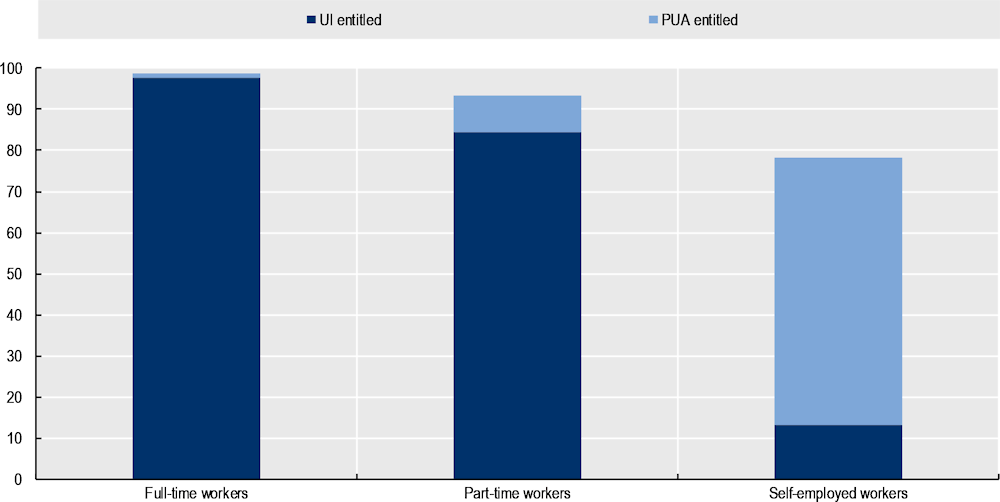

2.4.2. Coverage of those currently in work is high, and varies little between groups

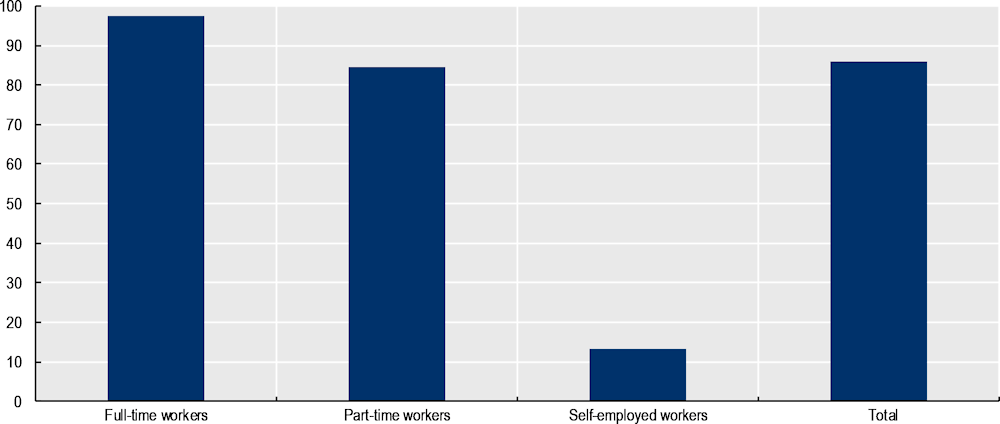

Compared to other countries, unemployment compensation in the United States is comparatively accessible in terms of minimum contribution periods and earnings requirments (see section 2.4). Consequently, among currently working individuals, almost all (98%) full-time workers and most (84%) part-time workers would be entitled to UI if they lost their job (Figure 2.7). Self-employed earnings do not give raise to UI entitlements in their own right, but those becoming jobless after self-employment can receive UI if they also had wage and salaried income in the past (13% of self-employed workers).

Figure 2.7. For current workers, employment status is a principal driver of access to UI

Share of working individuals meeting UI entitlement conditions, by employment status (2016), in percent

Note: Share of all working individuals who would meet the entitlement conditions to UI in their state if they lost their job involuntarily, given their past earnings history, averaged over 2016.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

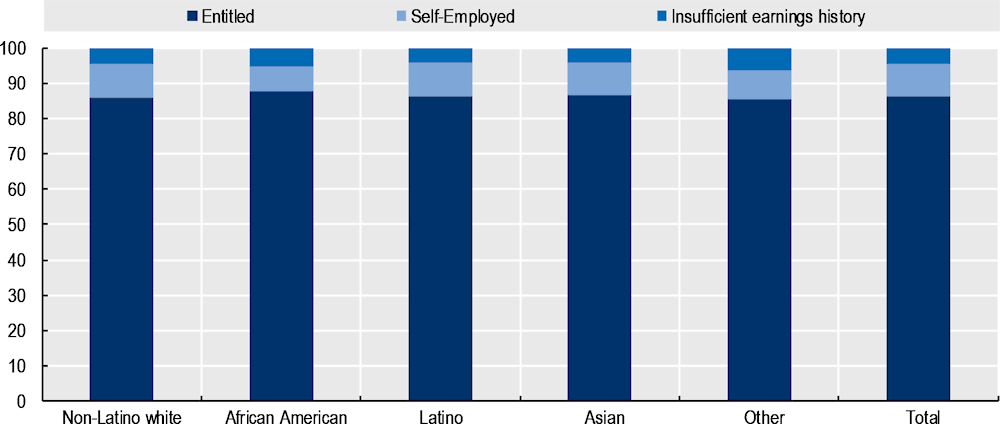

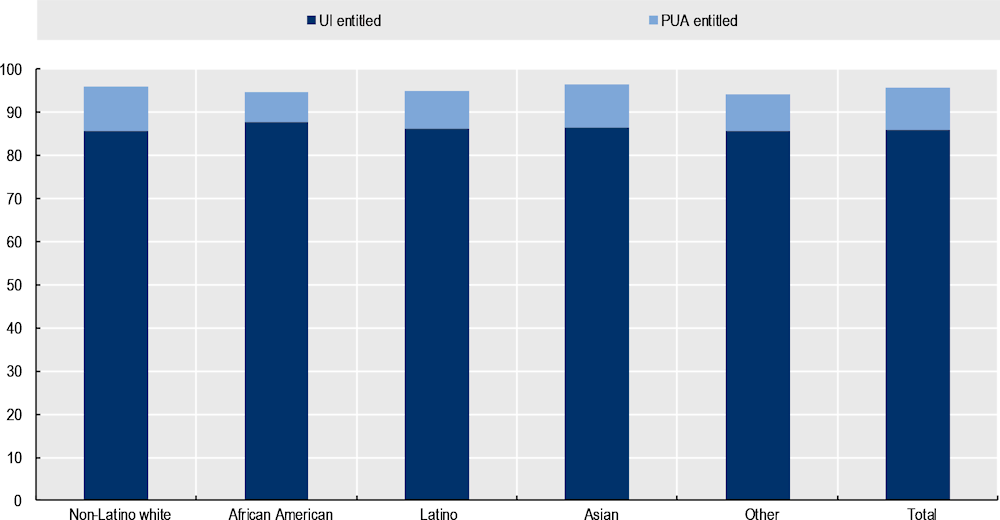

There are only marginal differences by race: African Americans have the lowest incidence of self-employment of all racial groups and are therefore most likely to meet UI entitlement requirements (88%, Figure 2.8). But the difference to non-Latino white workers (86%) is small. There are no notable differences in UI entitlements of current workers by gender. Differences by region are equally minor, in line with the fact that minimum earnings and contribution periods do not vary significantly by state and are only binding for very low earners (see Annex 2.C). Young (19‑29) and Prime‑age (30‑49) workers (88%) are more likely to qualify than older workers (82%), with the difference again due to a higher incidence of self-employment among older workers. Access to UI does differ somewhat by education: workers without a high school degree are most likely to be self-employed, whereas very few highly educated workers (tertiary degree) do not fulfil the necessary earnings requirements.

Figure 2.8. In the working individuals, UI eligibility does not significantly vary by race

Share of working individuals meeting UI entitlement conditions, by race, (2016), in percent

Note: The simulated eligibility is the eligibility of all workers theoretically eligible for unemployment compensation if they lose their job. For details on the definition of racial and ethnic categories see the Reader’s Guide.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

2.4.3. Long-term unemployment is a primary reason for low coverage among jobseekers …

The unemployed sample consists of individuals who reported being unemployed in the SIPP data. This includes individuals who do not have a job during the reference week and are available for and actively looking for work (ILO definition). This sample therefore excludes the underemployed (part-time workers looking for more hours or self-employed workers looking for wage or salary employment) as well as those marginally attached to the labour force (open to work and have looked in the past, but not actively searching). As in other countries, some individuals may receive unemployment compensation while not actively looking for work, e.g. because of care responsibilities.

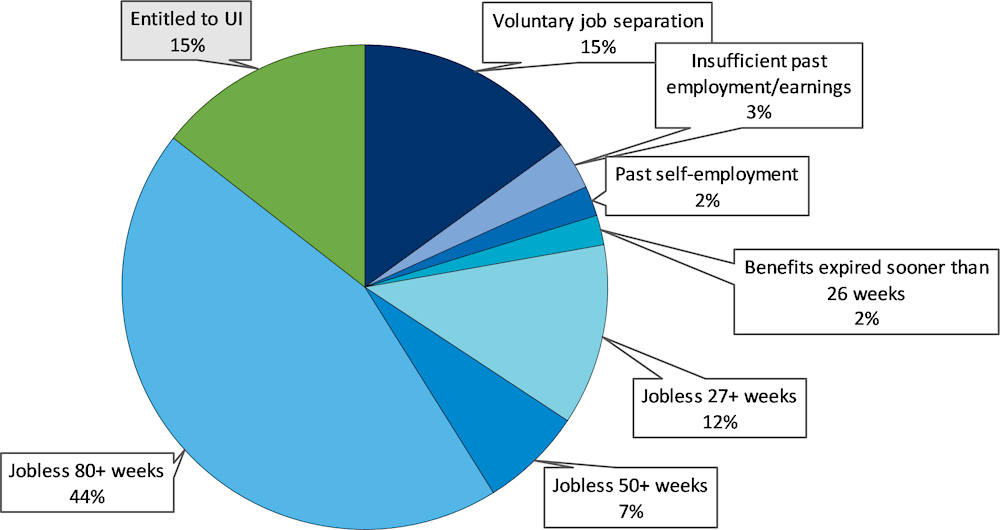

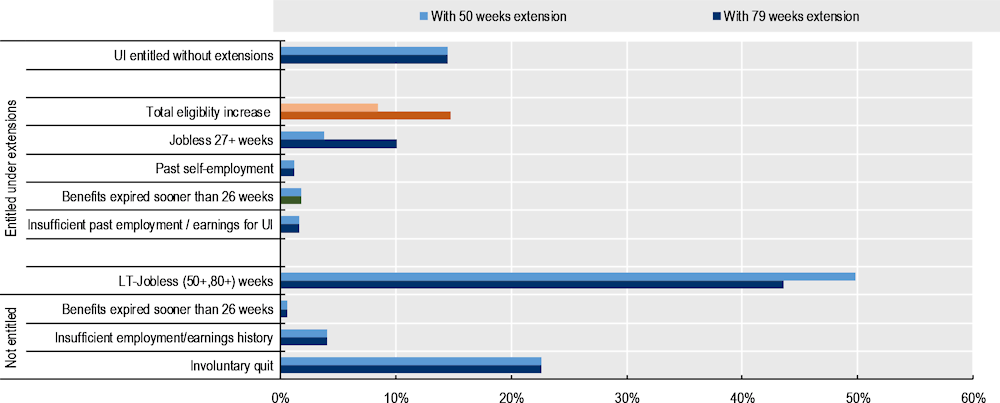

Only 15% of current jobseekers are entitled to unemployment benefits (Figure 2.9). The main reason for non-coverage is long-lasting joblessness: 63% of jobseekers have been out of work for longer than 26 weeks, the maximum unemployment duration in most states. 51% have been without work for 50 weeks or more, and 43% for 80 weeks or more. Even if they were entitled to UI when they became unemployed, they would have exhausted their entitlements during the observation period. An additional 2% were entitled to fewer than 25 weeks, because they live in a state that has a shorter maximum receipt duration,11 or that determines maximum benefit duration based on past work history (“benefits exhausted after less than 26 weeks” in Figure 2.9).

Other factors leading to non-entitlement include voluntary job quits (about 15% of all unemployed), past self-employment (2%), or insufficient work/earnings history from past employment (3%).

Figure 2.9. Most unemployed are not entitled due to long out-of-work durations

Breakdown by reason of non-entitlement, 2016

Note: “Benefits expired sooner than 26 weeks”: was entitled to fewer than 25 weeks of benefits because of a short work history/low earnings and the statutory rules of their state.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

It is worth highlighting that the share of unemployed workers who have been out-of-work for 12 months or longer (about 50%) is much higher than the commonly reported incidence of long-term unemployment (the share of all unemployed with unemployment durations of 12 months or longer), which stood at about 16% to 17% in 2016, depending on the data source.12 The reason for the discrepancy is that the simulations must consider the entire out-of-work spell prior to the reference month in order to establish entitlement.13 By contrast, the long-term unemployment rate considers jobseekers who have been continuously unemployed (jobless, available for work and actively looking for a job) for 12 months or longer.

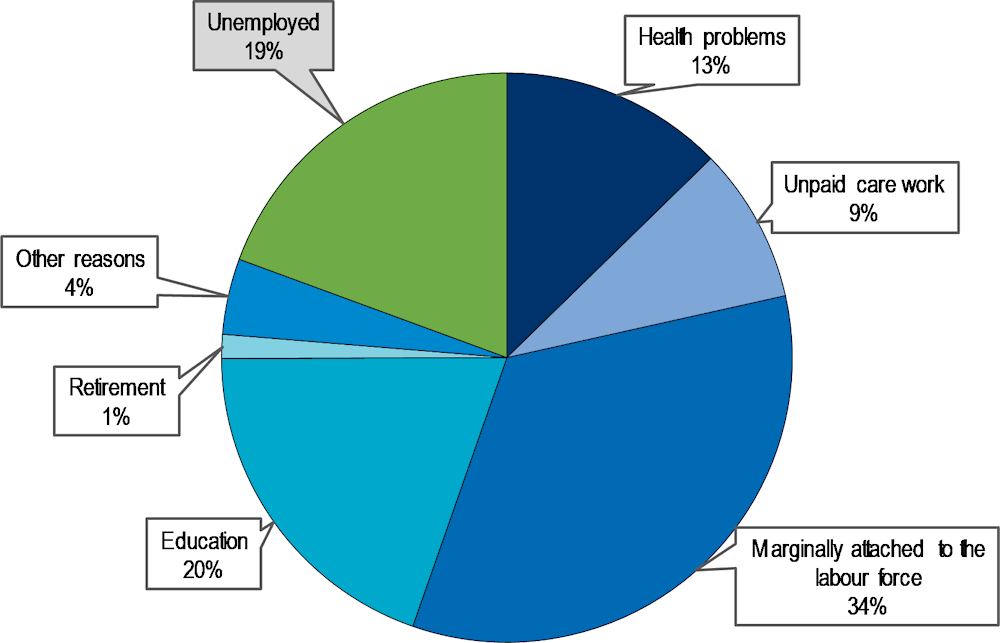

In practice, longer out-of-work spells very often include periods of labour-market inactivity. Figure 2.10 shows a breakdown of all months spent out of work prior to the current reference month, for all unemployed individuals in the sample, calculated on average over the year 2016.14 Only 19% of the total sum of out-of-work months were unemployment spells according to the ILO definition. One‑third was spent jobless, but not actively looking for work (“marginally attached to the labour force” – open to finding a job, and with a history of past job search, but not actively looking for work), and 20% were time spent in education (reflecting often difficult school-to-work transitions). Another 13% were spent unable to work because of health problems, and 9% doing unpaid care work. Thus, the majority of unemployed workers do not start their job search immediately after a losing a job. They are therefore difficult to reach by an unemployment insurance system designed for displaced workers.

Figure 2.10. Many unemployed workers were labour-market inactive before starting to look for a job

Breakdown of the sum of all months spent out of work for currently unemployed individuals, spells extending to 2016

Note: The graph shows the sum of all months unemployed individuals have spent out of work during their current unemployment spell, calculated prior to the reference month, looking back until the beginning of the panel (January 2013). That is, on average over all ILO-unemployment-months in 2016, 20% of all out-of-work spells extending into 2016 were spent in education, 13% were spent unable to work because of health reasons, etc. “Marginally attached to the labour force” means open to finding a job, and with a history of past job search, but not actively looking for work.

Source: OECD calculations based on 2014 SIPP data.

2.4.4. … and African Americans are most likely to be long-term unemployed

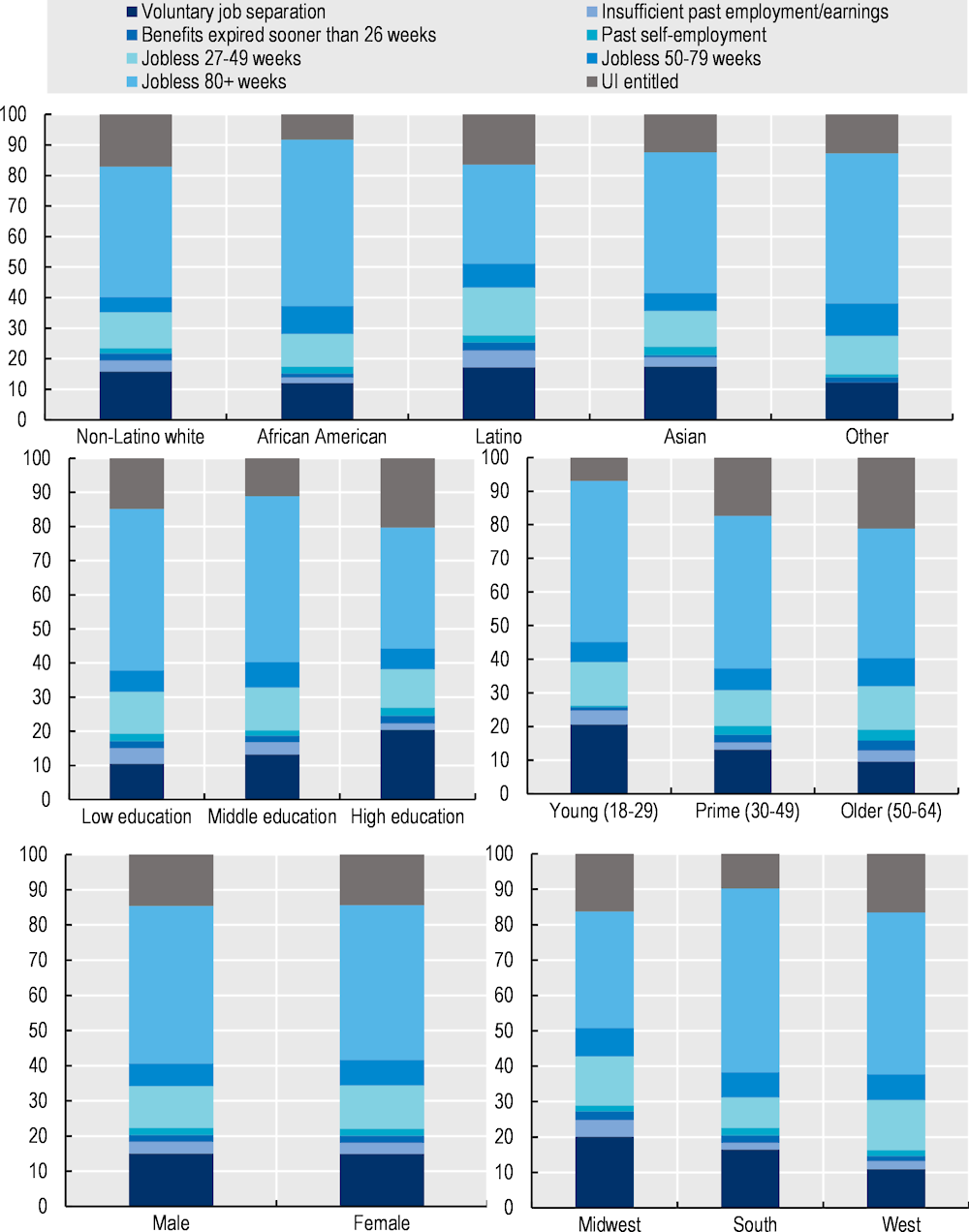

There are significant differences in UI coverage among demographic groups and regions, and much of this is driven by differences in the incidence of long-term unemployment (50+ weeks15). African Americans are least likely to be entitled to UI, at only 8% of the unemployed, compared to 16‑17% among non-Latino whites and Latinos. African Americans are also much more likely to have been out of work for 50 weeks or longer (64%) compared to non-Latino whites (48%), Latinos (40%) and Asians (52%, Figure 2.11)

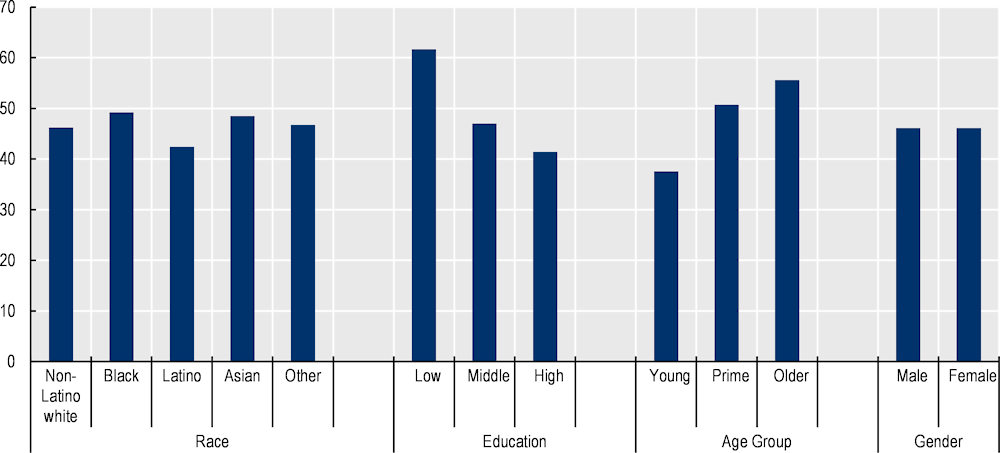

Figure 2.11. Incidence of long-term unemployment drives patterns of coverage gaps

Jobseekers by reason of non-entitlement and socio-demographic characteristics, 2016

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). For details on the definition of racial and ethnic categories see the Reader’s Guide.

Only 7% of young unemployed individuals (18‑29) are entitled to UI, compared to 17% for prime‑age (30‑49 years) and 21% for older jobseekers (50‑64 years). Young jobseekers are more likely than prime‑age and older unemployed workers to have voluntarily left their previous job or to be out of work for over 50 weeks. Highly educated workers are the group most likely to be covered by UI (20%), and those with high school, but no college degree are least likely to be covered (11%). There are no significant gender differences (as was also the case for the working sample in section 2.4.2, Figure 2.11).

Statutory UI entitlement rates are significantly lower in the South (10%) than in other regions (17‑18%, Figure 2.11). This is related to the higher incidence of long-term unemployment in the South (50%), compared to 41% in the Northeast and 32% in the Midwest. Both white and African American jobseekers are more likely to be long-term unemployed in the South than in other regions.16 African American jobseekers are more likely to be long-term unemployed than Latino and non-Latino white jobseekers in all regions, but, the difference in the shares of long-term unemployment between African American and white jobseekers is greater in the South than in other regions. Thus, African Americans are not only more likely to live in the South (see Figure 2.5, Panel B) where long-term unemployment is higher for all racial and ethnic groups, but they are even more likely to be long-term unemployed if they live in the South.

2.5. Would the COVID‑19 emergency extensions close coverage gaps?

This section simulates the impact of key COVID-related UI extensions in a non-crisis labour market. The assessment is intended as a thought experiment, rather than a statement about the parameters of future reforms that are desirable or realistic. The aim of the simulations is to inform the debate on whether extensions that are related to those undertaken in response to COVID‑19 could also help to address the structural coverage gaps that were documented in the sections above, or whether other or additional measures would be needed.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC), and Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) dramatically increased coverage and generosity of unemployment compensation. The FPUC topped-up unemployment benefit amounts, whereas the PEUC increased the duration of payments and the PUA extended eligibility to many previously non-eligible individuals. Box 2.2 provides a detailed description of these programmes. The main measures are:

Extension of unemployment compensation to self-employed workers (modelled in the simulations reported below);

Extension of the maximum receipt duration to a flat 50/79 weeks for all recipients (modelled);

Extension of UI entitlements to all workers who worked for at least one week at the state’s minimum wage during the calendar year preceding unemployment (modelled);

Increase of the minimum benefit amount in all states (modelled);

Top-up of weekly benefit amounts by USD 300 to USD 600 (varying over time) (not modelled).

As a result of both pandemic-related layoffs and the increased coverage resulting from the emergency measures, unemployment benefit receipt increased dramatically during the COVID‑19 pandemic. In contrast to most other OECD countries, the labour market shock caused by the initial COVID‑19 outbreak in the United States was largely absorbed by UI payments. By contrast, the job-retention scheme in the United States (Short-time Compensation) remained marginal throughout the crisis. At the height of the pandemic-related labour-market shock, the number of unemployment benefit claimants, including workers on temporary lay-off, reached nearly 16% of the US working-age population (Figure 2.12). Spending jumped from less than USD 4 billion per month before the pandemic to USD 120 billion per month in June 2020. It gradually declined afterwards but remained at elevated levels throughout 2021 (US Department of Labor, 2022[15]).

In addition to the increase in coverage, the top-ups of weekly benefit amounts by USD 300 to USD 600 (varying over time, and not modelled in this chapter) significantly increased benefit payments, and replaced more than 100% of pre‑pandemic earnings for more than 75% of beneficiaries (Ganong, Noel and Vavra, 2020[4]). In spite of these very generous benefit levels, the effect of the top-ups on employment was smaller than expected in a non-pandemic labour market. (Marinescu, Skandalis and Zhao, 2021[16]) show that, while online job applications did decrease, the number of vacancies was so low that this depressed search behaviour did not affect employment. Firms recalling former workers likely played a role in the dampening of the disincentive effect of weekly top-ups (Ganong et al., 2022[17]). See (Whittaker and Isaacs, 2022[18]) for a succinct overview of the literature.

Figure 2.12. In the United States, Unemployment benefits absorbed the bulk of the COVID‑19 employment shock

Recipients of unemployment insurance and job retention scheme support as a percentage of the working-age population

Note: The figures reported are claimant not recipient numbers, and aggregate over different programmes, including Unemployment Compensation, and PUA. For details on the programmes included and methodological notes, please consult the SOCR-HF database.

Source: OECD Social Benefit Recipients – High-Frequency database (SOCR-HF), https://www.oecd.org/fr/social/soc/recipients-socr-hf.htm

Box 2.2. COVID‑19 related extensions to unemployment compensation

The United States introduced the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act on the 27 March 20201. The CARES Act introduced three measures for newly unemployed workers: the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC), and Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA).

On the 27 December 2020, the federal government extended these programmes and added another, the Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation (MEUC). The federal government again extended these programs on the 11 March 2021 with the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).

Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC)

The FPUC provided a supplemental payment to individuals who were receiving regular unemployment benefits or other related unemployment compensation programs who had not exhausted the maximum benefit duration2. From the 4 April 2020 to its initial expiry on the 25 July 2020, the FPUC topped-up unemployment benefits by a flat rate of USD 600 per week. After the initial expiry of the FPUC, a similar benefit, the Lost Wages Assistance programme, provided a flat rate federal top up of USD 300 per week to unemployed workers eligible for UI payments between the 1 August 2020 and the 5 September 2020. The government then reauthorised the FPUC from the 1 January 2021 to the 13 March 2021, with the same flat rate benefit of USD 300. The American Rescue Plan Act again extended the USD 300 top-up until the 6 September 2021, at which time it expired.

Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC)

The PEUC programme initially provided up to 13 additional weeks of unemployment benefits to individuals who had exhausted their regular state benefits (which typically last between eight and 28 weeks). Claimants were required to continue to fulfil the requirements of unemployment compensation (i.e. able to work, available for work, seeking work) and not be receiving regular compensation from any other state or federal programme. The Continuing Assistance Act further increased the number of additional weeks to 24, and the ARPA further extended this to 53 weeks. The PEUC programme expired on the 6 September 2021.

Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA)

The PUA programme was a new unemployment assistance programme introduced with the CARES Act of 2020. The programme provided benefits to individuals with some attachment to the labour market who were not otherwise eligible for regular unemployment compensation. This included the self-employed and gig-workers and individuals with insufficient work history or earnings. Individuals qualified if they were unemployed, partially unemployed, or unable to work because of COVID‑19. An inability to work included having COVID‑19, living with someone who has COVID‑19, being a primary caregiver for a child or other dependent, a need to quarantine, a drop in demand due to COVID‑19, and other COVID‑19 related reasons.

The programme paid retroactive benefits from 27 January 2020 until the programme expired on 5 September 2021.3 Minimum benefits were raised to half of each state’s average weekly benefit payments prior to the crisis (see Annex 2.D, (US Department of Labor, 2020[19])). The programme initially provided up to 39 weeks of benefits (less any weeks of state‑provided extended benefits for regular unemployment compensation). The Continuing Assistance Act (CAA) increased the duration to 50 weeks, and ARPA increased it to 79 weeks. The simulations consider both the original 50 weeks extension as well as the overall 79 weeks.4

. Two smaller support measures, signed on 6 March and 18 March 2020, preceded the CARES Act, providing increased medical testing capacity and provided paid sick leave and unemployment assistance for some families affected by COVID‑19.

1. Two smaller support measures, signed on 6 March and 18 March 2020, preceded the CARES Act, providing increased medical testing capacity and provided paid sick leave and unemployment assistance for some families affected by COVID‑19.

2. Benefits briefly lapsed during the end of 2020 while lawmakers negotiated legislative extensions.

3. In addition, the MEUC programme, which is small in size and not covered in detail, allowed states to provide an optional top-up of USD 100 to recipients of some types of unemployment insurance benefits (notably excluding PUA benefits). By September 2021, USD 46.8 million had been disbursed across 20 States.

Source: (US Department of Labor, 2021[20]), Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers (Continued Assistance) Act of 2020, https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_15-20_Change_3.pdf

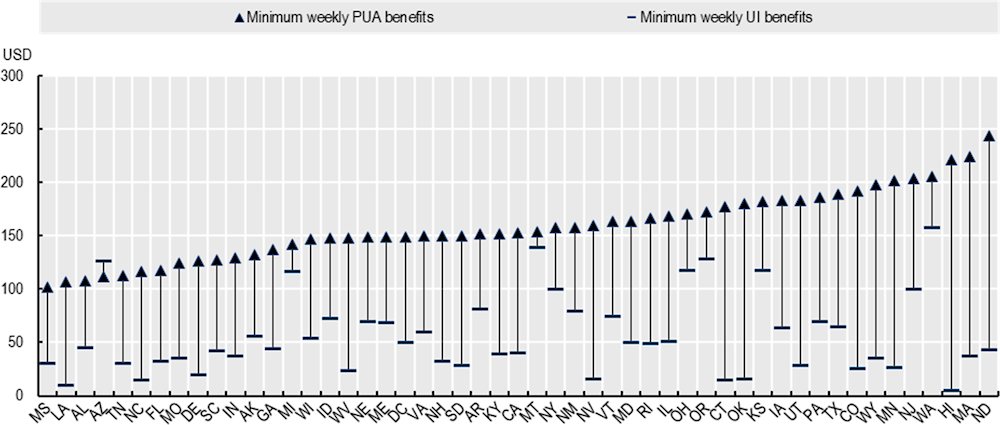

2.5.1. For working individuals, the extension of UI to the self-employed almost closes coverage gaps

For the sample of currently working individuals, that had a high base‑line level of entitlement among wage and salaried employees (see section 2.4.2), the expansion of unemployment compensation to self-employed individuals was the most significant.

Overall, the share of current workers entitled to UI in the event of a job loss increases from 86% to 95%. As 98% of full-time workers were already entitled to UI under the pre‑pandemic system (Figure 2.7), PUA leads to a marginal increase for them (+1 percentage points), while the increase is sizeable for part-time workers (from 84 to 93%). For self-employed workers, the share with UI entitlement jumps from 13 to 77% (Figure 2.13). Coverage for self-employed workers is still incomplete since, under PUA, statutory entitlement is based on the previous calendar year’s earnings, while a sizeable share of self-employed workers started their business only in the current year.

Figure 2.13. The PUA extended eligibility mainly for self-employed workers

Share of working individuals eligible for unemployment compensation by main status (2016), in percent

Note: Share of the working sample with statutory entitlement to unemployment compensation if they lost their job involuntarily.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

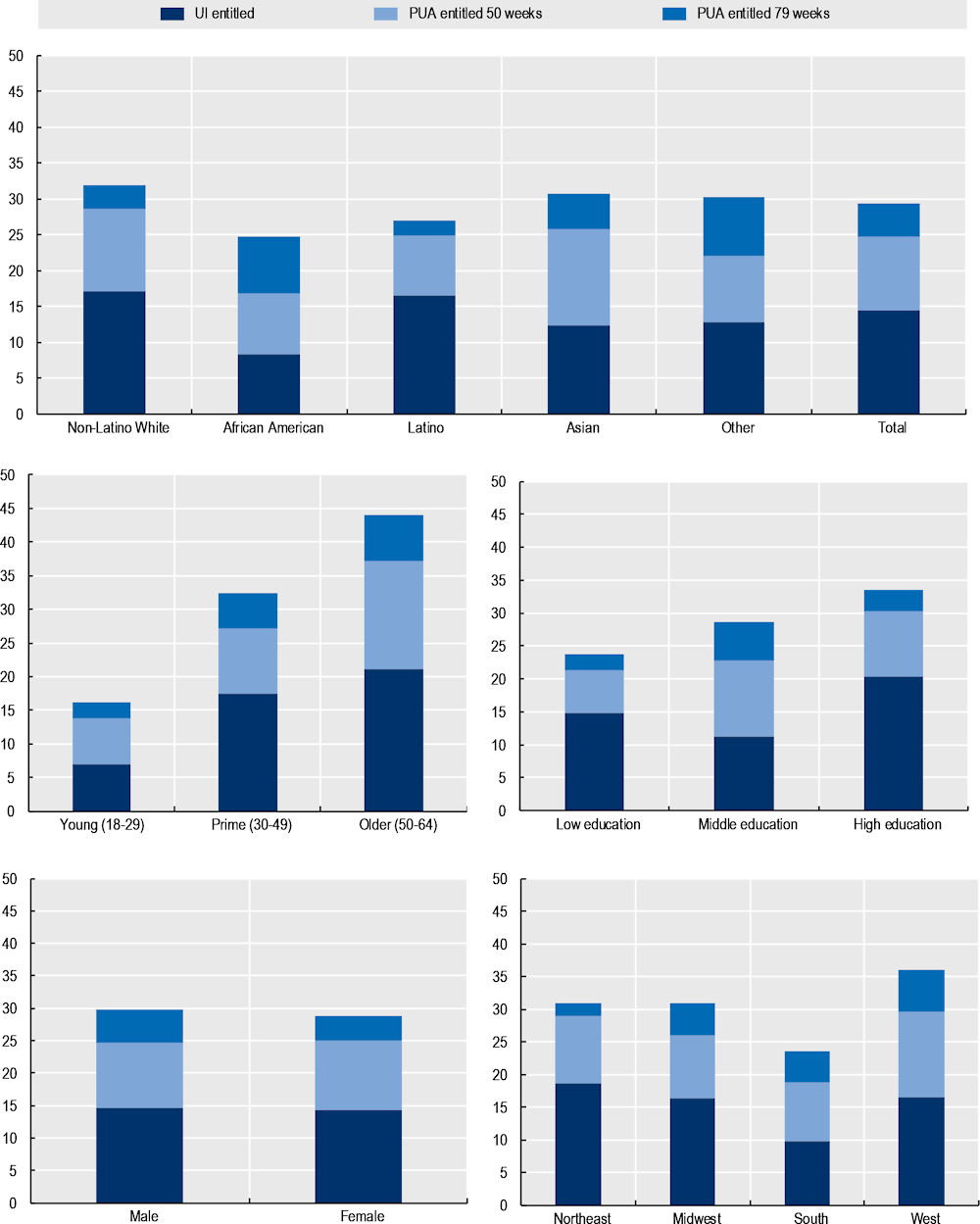

All racial groups benefit from the PUA extensions (Figure 2.14). Coverage gains are greater for Non-Latino whites (10 percentage points) than for African Americans (7 percentage points), owing to the higher incidence of self-employment among non-Latino whites. Because statutory coverage is already high for all groups of the working sample to start with, these changes do not result in major gradients across race and gender, however. Coverage gains are also broadly balanced across regions (between 9 and 10 percentage points). Differences are more pronounced across age groups, as coverage increases by 7 percentage points for young and 13 percentage points for older workers, again driven by a higher share of self-employed workers among older age groups. Self-employment is also more prevalent among low educated workers, leading to stronger increases in statutory coverage in this group (see Annex 2.E).

Figure 2.14. A PUA-type extension would raise statutory entitlements for workers across all racial and ethnic groups

Share of working individuals entitled to UI, with and without PUA, by race, 2016 in percent

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). For details on the definition of racial and ethnic categories see the Reader’s Guide.

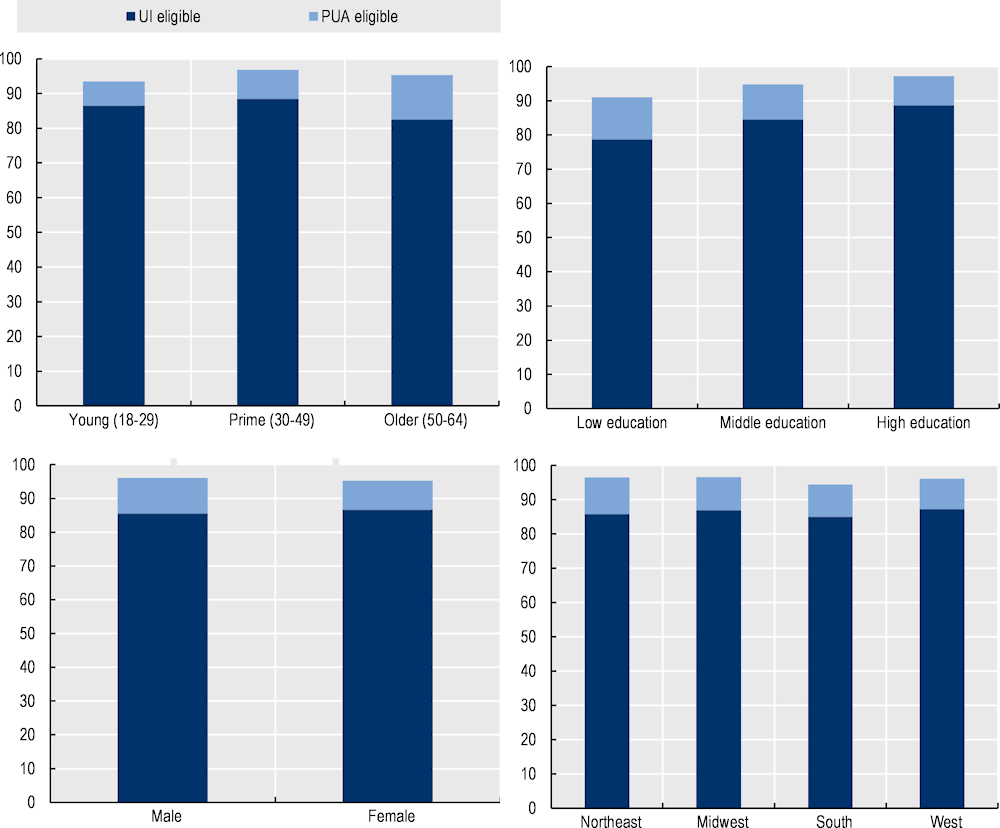

2.5.2. PUA extensions would be insufficient to ensure coverage for the long-term unemployed

The main reason for large coverage gaps among jobseekers is the high incidence of long-term unemployment (section 2.4). PUA did result in significantly longer maximum benefit receipt durations – from between 12 to 26 weeks depending on the state prior to emergency extensions, to a flat 50 weeks initially, and then to 79 weeks in March 2021. The simulations follow the stepwise PUA extension to 50 and 79 weeks.

With a maximum duration of 50 weeks and given the patterns of unemployment in the 2016 SIPP data, the share of jobseekers with entitlements to UI increases by 8.5 percentage points (Figure 2.15). This concerns mainly jobseekers with an unemployment duration between 27 and 49 weeks (accounting for 3.8 percentage points), and jobseekers whose entitlements were shorter than 26 weeks before the extension (+1.9 percentage points, “benefits expired sooner than 26 weeks”). A PUA-type extension would also increase coverage for some with a short work history or low earnings (+1.6 percentage points, “insufficient past employment/earnings for UI”) and for those with past self-employment (+1.2 percentage points). The sizeable group (about a quarter) of unemployed who quit their jobs voluntarily would remain unaffected by the extensions.

With a 79‑week PUA extension, statutory coverage increases by a further 6 percentage points (Figure 2.15). Yet, since nearly half of all jobseekers have been out of work for 80 weeks or longer in 2016 (Figure 2.9), more than half of the jobseekers who are not entitled under the current system would also remain uncovered.

Coverage gains from a PUA-type extension are higher for Asians, African Americans and other racial and ethnic groups (+16‑18 percentage points), compared to Latinos (+11 percentage points) and non-Latino whites (+15 percentage points, Figure 2.16). Unemployed Asian Americans have the highest incidence of past self-employment, while long-term unemployment is more prevalent among African Americans (Figure 2.11). Latinos and non-Latino whites are less likely to be long-term unemployed, and therefore benefit less from extended receipt durations. Small sample sizes hinder further cross-tabulations and more granular assessments of the specific drivers behind the patterns across racial and ethnic groups. Older jobseekers benefit significantly more from the PUA extensions (+23 percentage points) than young (+9 percentage points) and prime aged individuals (+15 percentage points). The higher incidence of voluntary quits among younger workers is one factor behind this result.

A 79‑week PUA-type extension would place maximum benefit durations in the United States among the longest in the OECD; only nine OECD countries provide unemployment insurance for longer than 18 months (Figure 2.6). Yet, even with such substantial extensions, fewer than one in three jobseekers would receive unemployment benefits according to the simulations. This is because a large share of jobseekers have either been unemployed for longer than 79 weeks, or their unemployment follows other out-of-work periods, i.e. their job search was preceded by education, caring for a household member, recovering from illness, or other labour-market inactivity, rather than coming directly after job loss (Figure 2.10).

Jobseekers who have returned to the labour force after a period of inactivity are difficult to reach for contribution-based unemployment benefits, which are primarily designed to provide consumption smoothing after a job loss. Countries where more than half of all unemployed workers receive unemployment benefits often combine contribution-based unemployment insurance with needs-based and means-tested unemployment assistance programmes. These programmes are support measures that, like unemployment insurance, are geared towards re‑employment, through activation measures and employment support. They can nevertheless be open to jobseekers without a (recent) employment history, e.g. in Finland, Germany, the United Kingdom, Ireland (Figure 2.1), providing a degree of income security regardless of people’s pathways into unemployment (see Box 3.3 and Box 3.4 on unemployment assistance benefits in the United Kingdom and Germany).

Figure 2.15. PUA-type extensions would not be sufficient to cover the long-term unemployed

Breakdown of unemployed workers by UI/PUA entitlement and reasons for (non)entitlement, 2016

Reading note: 50% of jobseekers are not eligible for either UI or Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA)because of their long unemployment duration under the 50‑week PUA extension (“Long-term jobless”). This share decreases to 44% under a PUA duration of 79 weeks as more individuals become entitled to PUA.

Among the individuals entitled under extensions:

Jobless 27+ weeks refers to individuals who were out of work for more than 2 weeks and therefore not eligible for UI payments but became eligible under the PUA duration extensions.

Past self-employment are jobless individuals who were previously self-employed and therefore did not qualify for UI payments. As self-employment earnings were counted for eligibility under PUA rules they became eligible.

Benefits expired sooner than 26 weeks refers to individuals who were eligible for UI but have since exhausted their payments (fewer than 26 weeks, either because of the maximum duration in their state or because of their contribution history).

Insufficient past employment/ earnings for UI refers to jobseekers whose reported earnings were not sufficient to qualify them for UI but qualified them for PUA.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

Figure 2.16. Asian and African Americans would benefit most from PUA-type extensions

Share of jobseekers entitled to unemployment compensation, by race, age, education, gender, and region, 2016, in percent

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). For details on the definition of racial and ethnic categories see the Reader’s Guide.

2.5.3. Impact of UI extensions on household incomes and poverty

This section looks at the effect of PUA extensions on household incomes, focusing on the final PUA provisions, with an extension of benefit durations to 79 weeks.

The extensions can affect jobseekers’ incomes directly through three channels:17 (i) by making UI more accessible and thus raising initial coverage, (ii) by making benefits available for longer, and (iii) by increasing benefit amounts, here through the higher benefit floors that PUA provides for.18

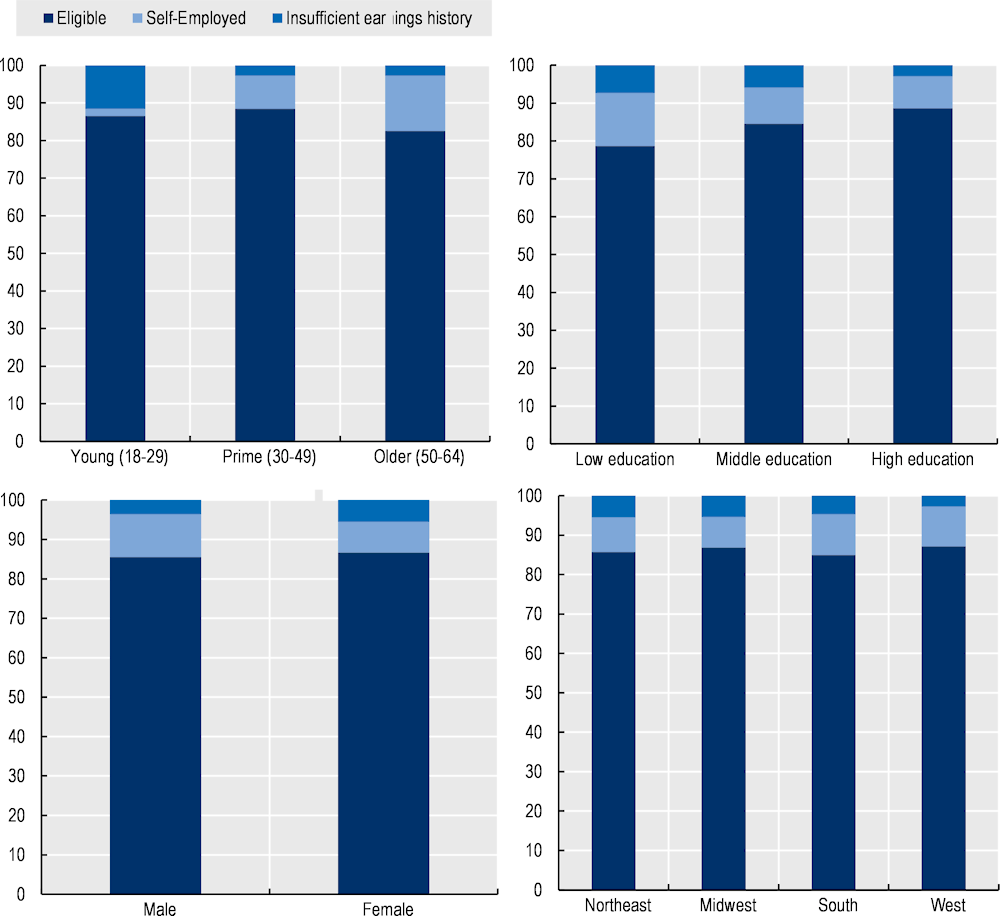

In the non-crisis labour market of 2016 – that is, even without the unprecedented levels of unemployment during the COVID‑19 pandemic – PUA-type extensions would increase aggregate expenditure on unemployment compensation by 89%. The majority of this increase is due to longer receipt durations (89%). Greater accessibility – the inclusion of self-employed workers and all workers who worked for at least one week at the state’s minimum wage during the calendar year preceding unemployment – would increase total expenditure by 11%. Although PUA also increased minimum weekly benefits in almost all states (see Annex 2.D), these minima remained too low to make a substantial difference for a significant number of jobseekers: only 1% of working individuals would receive their state’s minimum benefit before the PUA extensions, and 9% after the extension.19

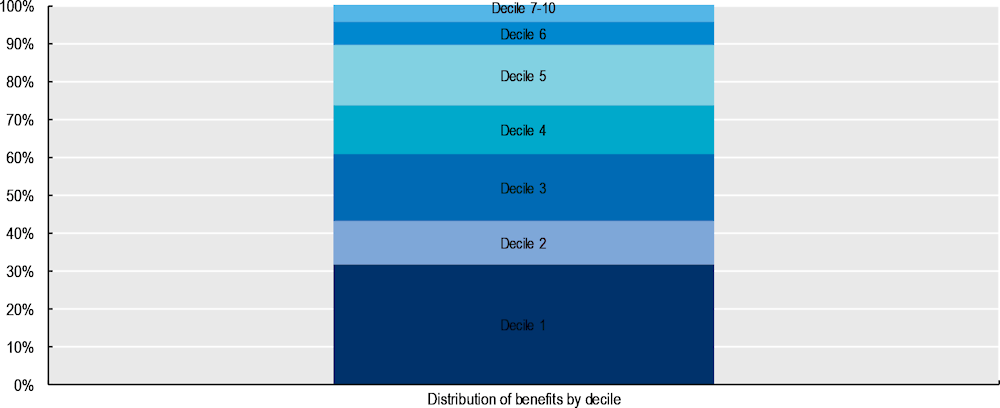

Over the entire year 2016, the extensions increase benefits received by around USD 4 400, which equates to a plus of 11% of the median household income. The incidence of additional benefit payments is fairly progressive: about a third is received by jobseekers living in households in the bottom 10% of the income distribution, and 60% by those in the bottom 30% (Figure 2.17).

Figure 2.17. PUA-type extensions would mostly benefit households at the bottom of the income distribution

Breakdown of additional PUA benefit payments* by deciles of equivalised household income, 2016, in percent

Note: *Benefit increase for jobseekers over an entire year, with a 79‑week extension scenario. Decile groups refer to equivalised household income (before transfers) in the entire population.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

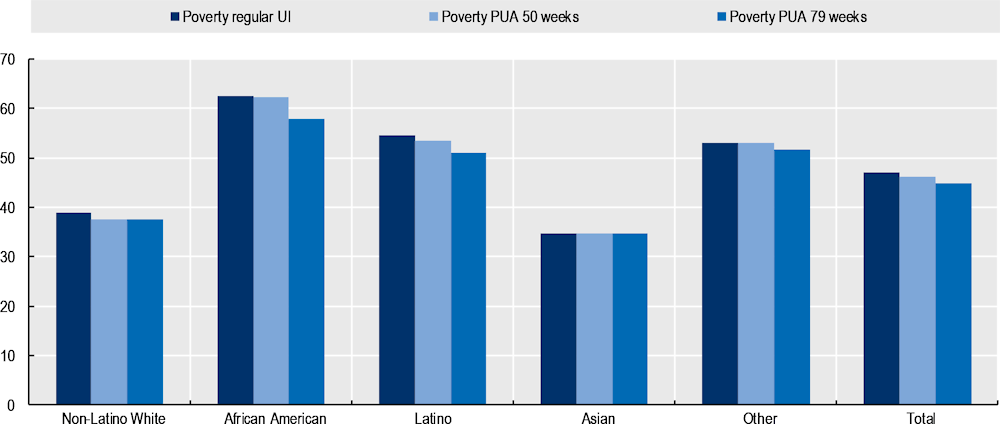

Prior to any UI extensions, roughly half (47%) of all jobseekers live in relative poverty (incomes below 50% of the median household income, following the standard OECD definition).20 Poverty risks are highest among African American jobseekers (62%) and lowest among Asian and non-Latino white jobseekers (between 35% and 39%). A 50 weeks PUA extension lowers poverty rate among jobseekers by 1 percentage point; and the full 79 week extension by a further 2 percentage points. The reduction is largest for African Americans and other racial and ethnic minority groups (-5 percentage points for the full 79 week extension) but almost zero for Asians (Figure 2.18). Poverty among children living in households with jobseekers also falls by 1 percentage point, to 48% but remains much higher than overall child poverty (27%, not shown).

Figure 2.18. Poverty reductions due to PUA-type extensions are modest overall, but significant for African Americans

Share of jobseekers living below a relative poverty threshold (50% of median equivalised disposable household income), 2016

Note: Median equivalised household incomes, excluding receipt of unemployment benefits as reported in the SIPP, plus simulated UI payments.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

Although effects on poverty headcounts are limited overall, PUA-type extensions do significantly reduce the depth of poverty. In comparative perspective across the OECD in 2021, the poverty gap, which is a measure of the depth of poverty, was 0.40 on average for income‑poor working-age households.21 It was lowest in Ireland (0.19) and highest in Italy (0.42); the gap in the United States was above the country average at 0.36. The poverty gap among income‑poor jobseekers is 0.44 before any extensions. It falls to 0.37 after the full 72‑weeks extension, indicating that the poorest households gain most from a PUA-type extension. The reduction is sizeable, roughly equivalent to the difference in the poverty gap between the United States and Germany (OECD, 2023[21]).

References

[12] Anderson, P. and B. Meyer (1997), “Unemployment Insurance Takeup Rates and the After-Tax Value of Benefits”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 112/3, pp. 913-937, https://doi.org/10.1162/003355397555389.

[7] Blasco, S. and F. Fontaine (2021), “Unemployment Duration and the Take-Up of Unemployment Insurance”, SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3767275.

[3] Congdon, W. and W. Vroman (2021), Covering More Workers with Unemployment Insurance: Lessons from the Great Recession, Urban Institute, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/ETA_GreatRecession_Covering-More-Workers_IssueBrief_March2021.pdf.

[17] Ganong, P. et al. (2022), Spending and Job-Finding Impacts of Expanded Unemployment Benefits: Evidence from Administrative Micro Data, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, https://doi.org/10.3386/w30315.

[4] Ganong, P., P. Noel and J. Vavra (2020), “US Unemployment Insurance Replacement Rates During the Pandemic”, NBER Working Paper, No. 27216, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, https://doi.org/10.3386/W27216.

[6] Hernanz, V., F. Malherbet and M. Pellizzari (2004), “Take-Up of Welfare Benefits in OECD Countries: A Review of the Evidence”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 17, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/525815265414.

[11] Hyee, R., R. Fernández and H. Immervoll (2020), “How reliable are social safety nets?: Value and accessibility in situations of acute economic need”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No 252, https://doi.org/10.1787/65a269a3-en.

[13] Kuka, E. (2020), “Quantifying the Benefits of Social Insurance: Unemployment Insurance and Health”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 102/3, pp. 490-505, https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_A_00865.

[5] Kuka, E. and B. Stuart (2021), “Racial Inequality in Unemployment Insurance Receipt and Take-Up”, NBER Working Paper Nr. 29595, https://doi.org/10.3386/W29595.

[16] Marinescu, I., D. Skandalis and D. Zhao (2021), “The impact of the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation on job search and vacancy creation”, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 200, p. 104471, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104471.

[22] OECD (2023), Long-term unemployment rate (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/76471ad5-en (accessed on 24 April 2023).

[21] OECD (2023), Poverty gap (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/349eb41b-en (accessed on 24 April 2023).

[14] Skandalis, D., I. Marinescu and M. Massenkoff (2022), “Racial Inequality in the U.S. Unemployment Insurance System”, NBER Working Paper Number 30252, http://www.nber.org/papers/w30252.

[15] US Department of Labor (2022), Unemployment Insurance Data, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/DataDashboard.asp (accessed on 1 August 2022).

[10] US Department of Labor (2021), Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws 2020, U.S. Department of Labor Office of Unemployment Insurance Division of Legislation, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2020/complete.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

[20] US Department of Labor (2021), Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers (Continued Assistance) Act of 2020 — Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) Program Reauthorization and Modification and Mixed Earners Unemployment Compensation (MEUC) Program Operating, Reporting, and Financial Instructions, Department of Labor, https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_15-20_Change_3.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2022).

[19] US Department of Labor (2020), Attachment II to UIPL No. 16-20 Change 1 : Calculating the Weekly Benefit Amount (WBA) - Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), Department of Labor, https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_16-20_Change_1_Attachment_2.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2022).

[9] US Department of Labor (2019), Unemployment compensation: Federal-State partnership, U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Unemployment Insurance, Division of Legislation.

[8] US Department of Labor (2016), Comparison of State Unemployment Laws 2016, Employment and Training Administration - US Department of Labor, http://www.oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/statelaws.asp#Statelaw.Other (accessed on 8 February 2022).

[2] Vroman, W. (2018), Unemployment Insurance Benefits Performance since the Great Recession, Urban Institute, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/96806/unemployment_insurance_benefits_performance_since_the_great_recession_2.pdf.

[1] Wentworth, G. (2017), Closing Doors on the Unemployed: Why most jobless workers are not receiving unemployment insurance and what states can do about it, NELP, https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/Closing-Doors-on-the-Unemployed12_19_17-1.pdf.

[18] Whittaker, J. and K. Isaacs (2022), How Did COVID-19 Unemployment Insurance Benefits Impact Consumer Spending and Employment?, Congressional Research Service, https://crsreports.congress.gov.

Annex 2.A. SIPP sample statistics

The 2014 SIPP panel contains 194 764 observations pertaining to 16 232 working-age (18 to 64) individuals for the year 2016 with complete labour market information, see Annex Table 2.A.1 for sample descriptive statistics and average earnings by key socio‑economic characteristics.22 The share of full-time workers was highest among non-Latino whites (54%) compared to other racial/ethnic groups having a lower share (49%). Self-employment was more common among whites and Asians than among Latinos and African Americans.

Annex Figure 2.A.1. Work status and race/ethnicity

|

Share of sample (%) |

Annual employment earnings (USD) |

Annual self-employment earnings (USD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Work status |

|||

|

Full-time worker |

52.13 |

62 985 |

336 |

|

Part-time |

13.58 |

20 383 |

105 |

|

Self-employed |

7.81 |

1916 |

50 515 |

|

Unemployed |

2.78 |

7 943 |

205 |

|

Out of labour force |

23.70 |

1692 |

127 |

|

Educational attainment |

|||

|

Less than high school |

10.82 |

12 570 |

1 786 |

|

High school |

47.54 |

24 160 |

2 751 |

|

Post-secondary |

41.64 |

56 505 |

6 407 |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Male |

48.73 |

44 788 |

6 211 |

|

Female |

51.27 |

28 377 |

2 228 |

|

Race/Ethnicity |

|||

|

Non-Latino white |

60.98 |

40 479 |

5 209 |

|

African American |

13.27 |

27 339 |

1 556 |

|

Latino |

15.81 |

26 001 |

2 195 |

|

Asian |

6.11 |

47 952 |

5 382 |

|

Other |

3.83 |

26 654 |

2 879 |

|

Age |

|||

|

Young (18 to 29) |

25.05 |

19 064 |

498 |

|

Prime‑aged (30‑49) |

42.09 |

45 372 |

4 608 |

|

Older (50‑64) |

32.86 |

38 045 |

6 404 |

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), observation year 2016.

Annex 2.B. Voluntary separations

In 2016, approximately 51% of all separations observed in the SIPP were voluntary. African American and Latino workers were slightly more likely to experience a job separation in 2016 (1.46% of all workers) than non-Latino white workers (1.37%). While differences in the rate of voluntary separations across racial and ethnic groups are minor, and there are no differences between men and women, workers with a college degree are significantly more likely to voluntarily separate from a job than those without a high-school degree, and younger workers are more likely to voluntarily separate than older workers (Annex Figure 2.B.1).

Low educated workers are more likely to lose their jobs due to slack work or the ending of a temporary or seasonal job, whereas older workers are more likely to lose their jobs when a company closed down, because of their position being abolished, or due to slack work conditions. In contrast, younger workers are more likely to separate from a job to pursue further education or training (not shown).

Annex Figure 2.B.1. Young and highly educated workers are more likely to involuntarily separate from their job

Involuntary separations as a share of all separations (%), the United States, 2016

Note: Young workers are aged 18 to 29, prime‑aged workers are aged 30 to 49, and older workers are aged 50 to 64. Low education is below high school, middle education includes high-school and some college, and high education is at least a two‑year college degree.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

Annex 2.C. UI eligibility by demographic group

Annex Figure 2.C.1. UI eligibility varies somewhat by education and age

Share of working individuals eligible for unemployment compensation by (a) age group, (b) education, (c) gender, and (d) region (2016), in percent

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

Annex 2.D. Minimum PUA benefits

Annex Figure 2.D.1. PUA increased minimum weekly UI benefits

Minimum weekly UI and PUA benefits, in USD, 2016

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

Annex 2.E. PUA eligibility by demographic group

Annex Figure 2.E.1. PUA extended eligibility across demographic groups and regions

Share of working individuals eligible for UI and PUA by (a) age, (b) education, (c) gender, and (d) region (2016), in percent

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

Notes

← 1. This report uses the terms unemployment compensation and unemployment insurance (UI) interchangeably in the context of the United States.

← 2. As in other parts of the OECD, some states provide exceptions to this rule, with UI entitlements for quits that are due to factors such as illness, workplace harassment, or childcare obligations. See (US Department of Labor, 2021[10]) for the United States, and the OECD database on the strictness of eligibility conditions for other countries (https://oe.cd/ActivationStrictness).

← 3. Exceptions include workers employed by their spouses or parents, hospital patients working for the hospital, real-estate agents (in most states), and some student workers.

← 4. E.g. Washington State operated a flat minimum threshold of USD 9 180 over the entire base period in 2016.

← 5. State‑level breakdowns of UI entitlements for unemployed workers cannot be shown because of small sample sizes.

← 6. Gross replacement rates in the United States and other OECD countries are not fully comparable: for the United States, the average is calculated as the average gross replacement rate for full-time workers (working individuals), thus, bigger states contribute more to the average figure. For OECD countries, this is the gross replacement rate of a full-time worker at the average wage.

← 7. An unemployment rate above 6.5%. Some states also have an additional programme in place that provides an extra seven weeks of benefit eligibility during extremely high unemployment.

← 9. See comparative policy summary tables at https://taxben.oecd.org/policy-tables/TaxBEN-Policy-tables-2020.xlsx. Australia and New Zealand operate unemployment assistance as the only form of unemployment support, i.e. they do not have a UI programme in place.

← 10. In their analysis of administrative data from audits on UI claims in the United States, (Skandalis, Marinescu and Massenkoff, 2022[14]) do not find evidence of discrimination against African American claimants in the implementation of UI rules.