This chapter explores the prevalence and costs of gender-based violence (GBV), including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. It introduces a comprehensive approach for tackling GBV through legal and a whole-of-government framework, developing a victim/survivor-centred culture and establishing robust accountability mechanisms.

Breaking the Cycle of Gender-based Violence

1. Why preventing and addressing gender-based violence matters

Abstract

In this report, “gender” and “gender-based violence” are interpretated by countries taking into account international obligations, as well as national legislation.

1.1. Gender-based violence (GBV) is a widespread problem and a high priority for governments

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon that manifests in multiple forms, including intimate partner violence (IPV), domestic violence, sexual abuse, exploitation and harassment, stalking, technology-facilitated violence, “honour”-based violence, female genital mutilation, forced marriages (including child and underage marriages), forced abortion and forced sterilisation (Box 1.1). IPV, a form of violence that happens between current or former intimate partners, is the most common type of GBV, and also manifests in several forms (see also Box 5.1). GBV is a form of violence committed against individuals because of their gender. Yet, while men can also become victims/survivors of gender-based violence, this report focuses on the experiences of women and girls, because they constitute the majority of victims/survivors. Women’s and girls’ experiences with GBV can vary due to the intersections of race, ethnicity, indigeneity, class, age, religion, migrant or refugee status, sexual orientation, disability, location and other identity factors. GBV occurs in all countries in the world and across all socioeconomic groups. Emergency and crisis situations may increase certain forms of GBV, as became evident during the COVID-19 pandemic and recent conflict situations (OECD, 2021[1]).

GBV is rarely an isolated, one-time occurrence. It is often part of an ongoing pattern of abuse that has been sustained by long-standing social norms and harmful gender stereotypes. GBV is a serious form of discrimination that constrains individuals’ ability to enjoy their rights and freedoms equally and to fully participate in society. GBV is not merely an interpersonal issue; it is a broader societal problem that has an impact on the economies, development and overall health of countries. Worldwide, nearly one in three women experience physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime (WHO, 2021[2]) (Sardinha et al., 2022[3]). However, this figure is probably much higher in reality, since many GBV cases go unreported, for a variety of reasons (OECD, 2023[4]).

Box 1.1. Forms of gender-based violence

Women and girls are exposed to GBV in both public and private spheres of their lives and can suffer physical, sexual, psychological, mental, emotional and economic harm. The complexity and pervasiveness of GBV make it difficult to provide a fully comprehensive list of the different forms it takes.

The most common type of GBV is intimate partner violence (IPV), the violence that occurs between current or former intimate partners, which can cause physical, psychological, sexual and/or economic harm. IPV can also manifest in many forms and includes acts of physical violence and/or sexual violence and/or emotional and psychological abuse and/or controlling behaviour.

As a far-reaching, legally binding human rights treaty covering all forms of violence against women, the Istanbul Convention is a valuable source for identifying different forms of GBV:

Psychological violence, which implies seriously impairing a person’s psychological integrity through coercion or threats.

Stalking, which involves repeatedly engaging in threatening conduct directed at another person, causing her or him to fear for her or his safety.

Physical violence, which includes committing acts of physical violence against another person.

Sexual violence (including rape), which implies the intentional conducts of i) engaging in non-consensual vaginal, anal or oral penetration of a sexual nature of the body of another person with any bodily part or object; ii) engaging in other non-consensual acts of a sexual nature with another person; and iii) causing another person to engage in non-consensual acts of a sexual nature with a third person.

Forced marriage, which involves forcing an adult or a child to enter into marriage.

Female genital mutilation, which includes the intentional conducts of i) excising, infibulating or performing any other mutilation to the whole or any part of a woman’s labia majora, labia minora or clitoris; ii) coercing or procuring a woman to undergo any of the acts listed in point i; and iii) inciting, coercing or procuring a girl to undergo any of the acts listed in point i.

Forced abortion, which implies performing an abortion on a woman without her prior and informed consent.

Forced sterilisation, which includes performing a surgery with the purpose or effect or terminating a person’s capacity to naturally reproduce without her prior and informed consent.

Sexual harassment, which includes any acts of unwanted verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person.

Crimes committed in the name of “honour”, which includes acts of violence justified by culture, custom, religion, tradition or so-called “honour”.

While the Istanbul Convention does not directly refer to technology-facilitated violence, it has been added to its Explanatory Report and to the Group of Experts on Action against Violence and Domestic Violence’s (GREVIO) General Recommendation No. 1 on the digital dimension of violence against women. In this context, digital violence includes the use of computer systems to cause, facilitate, or threaten violence against individuals that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, psychological or economic harm or suffering.

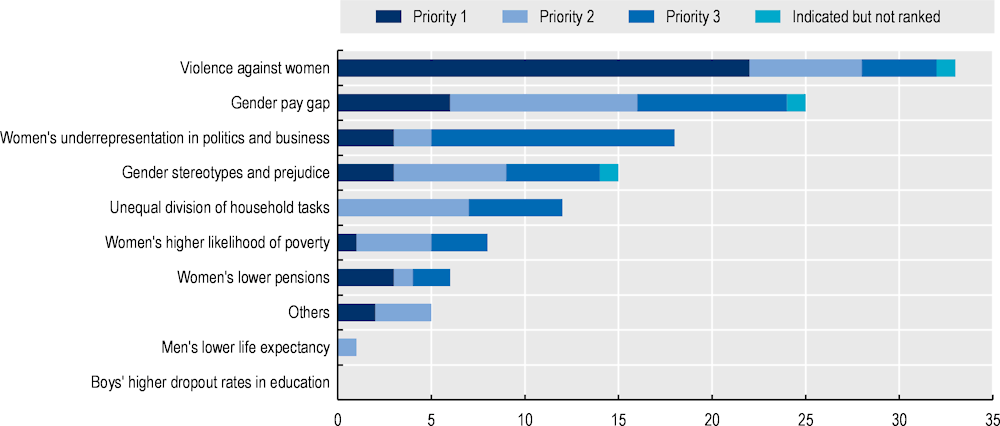

Addressing violence against women1 (VAW) remains the top priority area of action to advance gender equality, according to 33 out of 41 government responses to the OECD 2021 Gender Equality Questionnaire (OECD, 2022[7]) (Figure 1.1). In recent years, many OECD member countries have made international commitments and domestic efforts to combat GBV (Box 1.2).

Figure 1.1. Violence against women is identified as a top priority area in gender equality

Note: The 2021 Gender Equality Questionnaire (2021 GEQ) asked Adherents to select the priority issues in gender equality in their country from a list of topics. This is different from policy priorities that countries may have on work to be undertaken by OECD, OECD committees and their subsidiary bodies (e.g. the Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance). The horizontal axis indicates the number of Respondents that ranked the issues among their top three priorities. Respondents also had the option of suggesting additional priorities. These are reported in the category ‘others’, and include ‘unequal labour force participation’, ‘health difference between genders’, ‘undervaluation of female-dominated jobs’ and ‘women’s safety’. This figure presents 41 responses (of which one indicated only priority 1 and 2, and one indicated 2 items for priority 3) from 42 countries (38 OECD member countries plus four non-member Adherents).

Source: OECD (2022[7]), 2021 OECD Gender Equality Questionnaire, as reported in the Report to the Council at Ministerial Level on the Implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations), C/MIN(2022)7/en.

Box 1.2. OECD member countries’ commitment to addressing GBV

The OECD Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance (GMG), made up of gender equality officials and experts from member and partner governments, has identified addressing GBV as a top priority in multiple surveys (OECD, 2021[1]), (OECD, 2022[7]). Over the past 10 years, many OECD member countries have ratified international treaties and supported agreements to combat VAW (e.g. the Istanbul Convention; the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women; and the DAC Recommendation on Ending Sexual Exploitation, Abuse and Harassment in Development Co-operation and Humanitarian Assistance (SEAH)). Member countries have also increasingly prioritised sexual harassment and violence against women as a domestic policy issue (OECD, 2022[7]).

As documented in this report and elsewhere, OECD member countries have also begun to address GBV in national action plans (strategic planning) over the past few years, and have created more robust legislation to combat GBV (OECD, 2021[1]); (OECD, 2017[8]). Certain countries have also begun centring victims/survivors at the core of their GBV policies and programming; improving institutional arrangements and interinstitutional co-ordination; introducing new support programmes (e.g. leave from work for victims/survivors); and implementing stronger data and information collection methods (OECD, 2022[7]).

The DAC Recommendation on Ending Sexual Exploitation, Abuse, and Harassment in Development Co-operation and Humanitarian Assistance

The 2019 OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) is the first international instrument on sexual exploitation and abuse, and sexual harassment (SEAH) that applies to development co-operation and humanitarian assistance. Its adoption was an important signal of support by the bilateral donor community (and other partners) of their individual and collective responsibility to better respond to and prevent SEAH.

The Recommendation supports more effective policies and practices of OECD DAC governments: both within their own government systems (usually centred in development agencies and ministries of foreign affairs), as well as how they collaborate with implementing partners and other actors, and in the delivery of development co-operation and humanitarian assistance, in countries across the globe. Since the adoption of the DAC Recommendation, OECD DAC governments have adopted policies and strategies to address SEAH; put in place reporting systems and complaint mechanisms (both within their own governments and in co-ordination with implementing partners in development/humanitarian contexts); and increased efforts to provide more comprehensive support to victim/survivors (both within their own institutions, or in development/humanitarian contexts).

The Recommendation was adopted by the 31 Members of the OECD DAC, and has since been adhered to by several UN organisations: UNICEF, UNHCR, UNOPS and UNFPA.

The 2013 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship

The 2013 Recommendation provides a set of measures through legislation, policies, monitoring and public awareness campaigns to promote gender equality in education, employment and entrepreneurship. Under the Recommendation, all OECD countries committed to promoting all appropriate measures to end sexual harassment in the workplace, including awareness and prevention campaigns and actions by employers and unions.

Source: (OECD, 2021[1]; OECD, 2017[8]; OECD, 2019[9]; OECD, 2017[10]; OECD, 2022[7]).

1.2. The high costs of gender-based violence

GBV is a worldwide crisis of discrimination and human rights violations. The costs, both for victims/survivors and for society more broadly, are high. Victims/survivors suffer both short- and long-term repercussions on their physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health, including physical injuries and long-term health conditions. GBV also affects victims’/survivors’ children’s health and well-being and also leads to high economic and social costs for victims/survivors, their families, as well as societies.

In 2021, 45 000 women and girls worldwide were killed by intimate partners or other family members (UNODC/UN Women, 2022[11]). The loss of human life is incalculable and has extreme ramifications on the victims’ children, family, friends and community. Several forms of GBV, including IPV and sexual abuse, also lead to an increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases (STI), such as HIV (Geller et al., 2020[12]). While physical injuries are immediate, both physical and sexual violence are linked to lasting mental health issues, like depression, post-traumatic stress and panic disorders (Garcia-Moreno, Guedes and Knerr, 2012[13]). Victims/survivors of IPV, the most common form of GBV, are at a sevenfold risk of experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (EIGE, 2021[14]), and at a threefold risk of experiencing depression and anxiety (EIGE, 2021[14]). Children of victims/survivors are also directly exposed to the physical, psychological, emotional and financial costs of GBV that can have a lasting effect on their well-being. The community of the victims/survivors, including their family, friends and colleagues, also bear these costs indirectly.

Perpetrators often isolate and control victims/survivors, who risk losing their social and economic independence and are at increased risk of experiences of poverty and inequality (CARE International, 2018[15]). This can result in extensive social and economic impacts for victims/survivors, such as social isolation, loss of wages and/or legal costs (Villagomez, 2021[16]). Furthermore, victims/survivors also face shame and stigma that can affect their participation in education, employment, civic life and politics (CARE International, 2018[15]). These consequences can become even more challenging with children in the home.

GBV also has economic ramifications on society as a whole. Studies show that GBV has significant economic costs in terms of expenditures on service provision (such as shelters, emergency rooms, counselling services and increased healthcare costs), lost income for women and their families, decreased productivity in the workforce, and negative impact on future human capital formation. Studies focused primarily on IPV, for example, estimate that such violence typically costs countries between 1%-2% of their annual gross domestic product (OECD, 2021[1]). The annual costs of GBV across the European Union are estimated to be EUR 366 billion (with IPV making up 48% of this cost), calculated based on lost economic output, costs of public services and an estimation of the physical and emotional impact on the victims’/survivors’ lives (EIGE, 2021[17]). One study in the United States has estimated that the total annual cost of IPV in the United States could be as high as USD 3.6 trillion (Peterson et al., 2018[18]), including costs related to criminal justice, healthcare, lost productivity and so on. Another study in Canada showed that GBV can reduce economic participation and reduce earnings for women over their lifetime, resulting in a total lifetime cost of USD 334 billion due to lost income (Zhang et al., 2012[19]). Further examples are highlighted in Box 1.3. In this sense, the costs of GBV are also negatively linked to economic growth (Duvvury et al., 2013[20]).

GBV must be addressed by all countries, primarily because of its impact on human lives and human rights. However, calculating the overall cost of GBV can serve as an additional justification for governments to prioritise prevention initiatives and responses to GBV (OECD, 2021[1]).

Box 1.3. Examples of cost analyses of gender-based violence

Latin America and Caribbean

In 2013, the Inter-American Development plan conducted a study estimating the costs of violence against women in terms of intangible outcomes, such as impacts on women’s reproductive health, labour supply, and the welfare of their children. The study involved a sample of 83 000 women in seven countries from all income groups and all sub-regions in Latin America and the Caribbean. The study revealed the following findings: i) domestic violence is highly prevalent in Latin American and Caribbean countries; ii) domestic violence is negatively linked to women’s health; and iii) the effect of domestic violence is not limited to the direct recipients of the abuse. For example, children whose mothers suffered from physical violence have worse health outcomes than those whose mothers did not (IDB, 2013[21]).

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) provided an estimate of the total economic costs of sexual violence in New Zealand, disaggregated by costs attributable to the Crown (e.g. the cost of services such as healthcare, income support, criminal justice costs to prosecute and rehabilitate offenders, etc.) and costs for individuals and society. The estimate of the total economic costs of sexual violence in New Zealand in 2020 was NZD 6.9 billion. This included NZD 600 million in costs to the Crown, NZD 5.2 billion in costs to individuals, and NZD 1.1 billion in costs to wider society (Schulze and Hurren, 2021[22]). The costs of sexual violence included both tangible and intangible costs. Tangible costs are those that can be fully tracked, such as medical treatment and prosecutions. Intangible costs are costs that represent something lost that cannot necessarily be fully accounted for, such as the long-term costs associated with pain and trauma. Such costs may include the treatment of symptoms and coping mechanisms used by survivors for unresolved trauma; the unreported toll on family and friends; and the ongoing long-term effects of PTSD and other mental illnesses.

Switzerland

Switzerland conducted a study identifying the direct and indirect costs of IPV. Specifically, the study measured costs relating to police services, social and health services, and costs resulting from unproductivity due to sickness, disability or death. The total tangible costs of intimate partner violence in Switzerland were estimated to be CHF 164 million each year. This corresponds to the expenditure incurred by a medium-sized Swiss city in a year (Government of Switzerland, 2013[23]).

1.3. COVID-19 presented unique challenges and opportunities in the context of GBV

The COVID-19 pandemic likely exacerbated the prevalence of GBV worldwide. During periods of confinement and social distancing, women experienced higher risks of gender-based and domestic violence (OECD, 2022[7]). The social and economic stressors as a result of COVID-19 – e.g. inability to leave the home, loss of social interactions, all-day presence of children after school closures, and job loss and health stress – increased the incidence of violence. Furthermore, the restrictions on individuals’ freedom of movement increased abusers’ control over women and girls during mandatory lockdowns. Women who experienced IPV faced more difficulty attempting to leave their households or to call emergency hotlines with their abusers present. Those already in shelters or temporary housing found it difficult to move, given the risks of infection and lack of options for relocation (OECD, 2020[24]).

Meanwhile, rapidly increasing reliance on digital technology during confinement also had implications for GBV. While some were able to increase their connections to the outside world through technology, others experienced further control and alienation because their live-in partners limited their access to mobile phones and computers (OECD, 2020[24]). Systemically, the COVID-19 pandemic increased physical barriers to key government services, including shelters, medical services, child protection, police and legal aid mechanisms (Pfitzner, Fitz-Gibbon and True, 2020[25]).Despite these challenges, the COVID-19 crisis created an opportunity for governments to better prevent, plan for and respond to GBV in emergency contexts in the future. Many countries reported increased attention to GBV issues as a result of the pandemic. This has translated into the adoption of regulatory and policy instruments to prevent and combat GBV. This report explores innovative responses that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic to address GBV, including: i) designing crisis management plans or contingency plans for addressing GBV at the time of such crises as pandemics, natural disasters and/or economic recessions, and guaranteeing funding to implement them; ii) making changes to GBV approaches in engagement with stakeholders by instituting, implementing and monitoring rapid-response interventions during crises; iii) developing strategies to improve intersectionality, with a special focus on vulnerable populations; iv) establishing multiple channels through which victims/survivors can report their abuse; v) implementing integrated-services responses and strengthening collaboration among service providers; vi) disseminating information more widely on services, justice pathways and rights; and vii) reducing barriers to access justice services (e.g. through the use of technology).

1.4. The OECD GBV Governance Framework

Governments have a responsibility to protect their citizens. An important element of this responsibility involves preventing and responding to GBV. Several elements can ensure a holistic, comprehensive and coherent response to the problem of GBV across various government bodies, sectors and society at large.

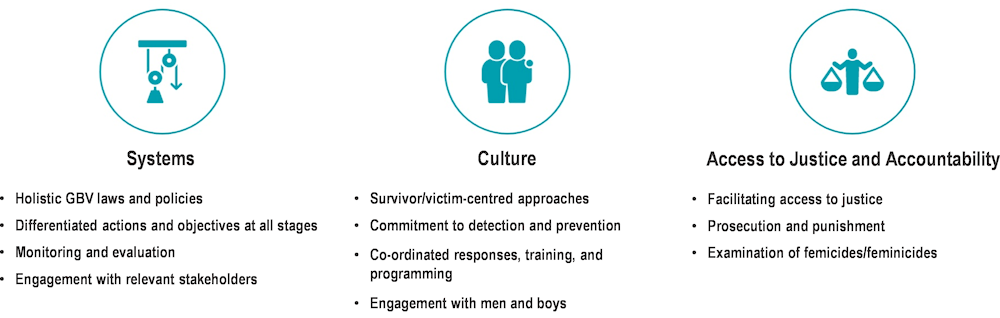

These are completed by the three-pillar approach of the OECD whole-of-government framework for addressing GBV, building on the 2021 OECD Report on Eliminating Gender-based Violence. This framework outlines the creation of holistic legal frameworks, policies and strategies (the Systems Pillar), the development of a victim/survivor-centric service culture (the Culture Pillar) and enforcing victims’/survivors’ access to justice and accountability (Access to Justice and Accountability Pillar). This report enriches the framework with data from across OECD countries to highlight good practices and to analyse existing gaps and challenges.

The Systems Pillar relies on holistic and comprehensive laws, policies and strategies that account for all forms of GBV and the experiences of all victims/survivors. Legal frameworks should offer protection to victims/survivors comprehensively and without legal loopholes. Their implementation should be supported by vertical and horizontal co-ordination mechanisms, sufficient funding, and by clearly identifying roles and responsibilities of state actors and relevant stakeholders, as well as establishing review mechanisms.

The Pillar on Governance and Service Culture emphasises that systems and services must be victim/survivor-centric, so that their intersectional needs and experiences are understood and accounted for in service delivery. This can be achieved by ensuring the integration and victim-centricity of service delivery in health, justice, and social sectors, capacity building of service providers, committing to GBV detection and prevention and engaging men and boys to challenge harmful gender attitudes and behaviour.

Finally, the framework is completed by ensuring the enforcement of legal frameworks through creating pathways for access to justice for victims/survivors of all backgrounds and holding perpetrators accountable for GBV. Key elements include designing justice-related services and proceedings that are responsive to the needs and experiences of victims/survivors; sanctioning and rehabilitating perpetrators; and tracking femicides/feminicides to address preventable failings and inadequate responses by the justice system.

The OECD framework builds upon and is complementary to existing international and regional standards and instruments, which all recognise the importance of state-wide policies to address GBV that are comprehensive, effective and co-ordinated across relevant public institutions. The OECD framework, drawn from country practices and policies around the world, and which emphasises implementation aspects, is complementary to the four-pillared Prevention, Protection, Prosecution and Co-ordinated Policies strategy of the Istanbul Convention.

Figure 1.2. Three-Pillar Approach to the OECD GBV Governance Framework

Source: OECD (2021[1]), Eliminating Gender-based Violence: Governance and Survivor/Victim-centred Approaches, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/42121347-en.

1.5. Methodology and structure of the report

In 2022, the OECD surveyed member countries on their approach to GBV (Box 1.4). This report, grounded in the new evidence that emerged from the three surveys/questionnaires, is completed with data from secondary research, country work and international conferences, including the 2020 OECD High-level Conference on Ending Violence Against Women. Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic are also incorporated.

Box 1.4. OECD Surveys and questionnaires informing this report

In 2022, the OECD conducted several surveys and collected responses to questionnaires from member countries on their practices to tackle GBV, which provide the basis for this report:

2022 OECD Survey on Strengthening Governance and Survivor/Victim1- centric Approaches to End GBV (2022 OECD GBV Survey) - The survey, conducted with OECD member countries, consisted of the Systems & Culture survey, which collected data key elements in a whole-of-government system for GBV, and the Access to Justice & Accountability survey, which examined different approaches countries are taking to enhance access to justice for victims/survivors. The survey was sent to Delegates to the Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance, under the Public Governance Committee. The report includes data from 26 OECD countries that responded to the survey.

2022 OECD Questionnaire on Integrating Service Delivery for Survivors of Gender-Based Violence (OECD-QISD-GBV) and the OECD Consultation with Non-Governmental Service Providers serving GBV Victims/Survivors (the OECD Consultation) - The Questionnaire gathered data about service-delivery arrangements designed to support women experiencing GBV across OECD countries. OECD-QISD-GBV asked countries about service provision and delivery in a range of sectors, as well as how integration is prioritised at the national level. The Questionnaire was sent to delegates to the Working Party on Social Policy (WPSP) under the OECD Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Committee (ELSAC) and 35 out of 38 member countries responded to QISD-GBV.

Additionally, an online, survey-based consultation was made available to non-governmental service providers working in the GBV space, under the guidance of the OECD WPSP, to gain insight from non-governmental service providers at the delivery level. The survey was also distributed informally through the European Family Justice Centre Alliance (https://www.efjca.eu/). In total, 27 responses were received from non-governmental service providers working in 12 OECD countries.

The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) and the SIGI Gender-Based Violence Legal Survey (SIGI GBV Legal Survey) - Since 2009, the OECD Development Centre has measured discrimination in social institutions globally. The SIGI assesses the level of discrimination girls and women face in formal and informal laws, social norms and practices. Its fourth edition was published in 2019, and the fifth edition is to be released in 2023. To assess the current status of legal frameworks on GBV, identify legal loopholes and showcase good practices, the OECD Development Centre conducted a dedicated “SIGI Gender-Based Violence Legal Survey” in 2022. The questionnaire covered laws and national policies or action plans on GBV against girls and women, with specific sections on domestic violence, rape, sexual harassment, female genital mutilation and child marriage. The survey was sent to the Development Centre member countries through its Governing Board. Among the 53 member countries of the Development Centre, 24 responded to the online survey. It comprises 16 OECD and 9 non-OECD countries. In addition, data from the fifth edition of the SIGI (2023) provides information for all OECD countries.

1. This report uses the terminology victim/survivor, aligning itself with other OECD products. The chosen terminology places “victim” first as a way to acknowledge that not all victims of GBV are survivors, making it more inclusive than “survivor”.

Source: OECD (2023[26]), "Social Institutions and Gender Index (Edition 2023)", OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/33beb96e-en (accessed on 31 May 2023).

The report is structured as follows:

Chapter 2 includes insights on the global legal landscape regarding GBV, including from the OECD Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI).

Chapter 3 presents efforts introduced by OECD countries to implement a whole-of-government approach for tackling GBV, as well as remaining challenges limiting its effectiveness.

Chapter 4 explores how victim/survivor-centred governance and service culture can be achieved by incorporating them into policy design and implementation and focusing on prevention efforts.

Chapter 5 discusses how governments are integrating service delivery across social, health, housing, justice and other sectors to support victims/survivors better, with a focus on intimate partner violence (based on (OECD, 2023[4]).

Chapter 6 examines access to justice for victims/survivors and accountability related to efforts to eradicate GBV.

References

[15] CARE International (2018), Counting the Cost: The Price Society Pays for Violence Against Women, https://www.care-international.org/files/files/Counting_the_costofViolence.pdf.

[6] Council of Europe (2011), Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (“Istanbul Convention”), Council of Europe Treaty Series, No. 210, Council of Europe, https://rm.coe.int/168008482e (accessed on 5 October 2022).

[20] Duvvury, N. et al. (2013), Intimate Partner Violence: Economic Costs and Implications for Growth and Development, Gender Equality and Development, No. 2023/3, Women’s Voice, Agency, & Participation Reserch Series, The World Bank, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/16697/825320WP0Intim00Box379862B00PUBLIC0.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[14] EIGE (2021), Gender Equality Index 2021: Health, European Institute for Gender Equality, https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/gender_equality_index_2021_health.pdf.

[17] EIGE (2021), The costs of gender-based violence in the European Union, European Institute for Gender Equality, https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/20213229_mh0921238enn_pdf.pdf.

[13] Garcia-Moreno, C., A. Guedes and W. Knerr (2012), Understanding and addressing violence against women, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77432/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[12] Geller, R. et al. (2020), “A Prospective Study of Exposure to Gender-Based Violence and Risk of Sexually Transmitted Infection Acquisition in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study, 1995–2018”, Journal of Women’s Health, Vol. 29/10, pp. 1256-1267, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.7972.

[23] Government of Switzerland (2013), Coûts de la violence dans les relations de couple, https://www.admin.ch/gov/fr/accueil/documentation/communiques.msg-id-51007.html (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[21] IDB (2013), Causal Estimates of the Intangible Costs of Violence against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean, Inter-American Development Bank, https://publications.iadb.org/en/publication/11285/causal-estimates-intangible-costs-violence-against-women-latin-america-and.

[26] OECD (2023), “Social Institutions and Gender Index (Edition 2023)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/33beb96e-en (accessed on 31 May 2023).

[4] OECD (2023), Supporting Lives Free from Intimate Partner Violence: Towards Better Integration of Services for Victims/Survivors, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d61633e7-en.

[7] OECD (2022), Report on the implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations for the Meeting of the Council at Ministerial Level, 9-10 June 2022, OECD, Paris, https://one.oecd.org/official-document/C/MIN(2022)7/en (accessed on 3 October 2022).

[1] OECD (2021), Eliminating Gender-based Violence: Governance and Survivor/Victim-centred Approaches, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/42121347-en.

[24] OECD (2020), “Women at the core of the fight against COVID-19 crisis”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/553a8269-en.

[9] OECD (2019), “DAC Recommendation on Ending Sexual Exploitation, Abuse, and Harassment in Development Co-operation and Humanitarian Assistance: Key Pillars of Prevention and Response”, OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/5020, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-5020.

[10] OECD (2017), 2013 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279391-en.

[8] OECD (2017), Report on the implementation of the OECD gender recommendations, Meeting of the Council at Ministerial Level, 7-8 June 2017, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/C-MIN-2017-7-EN.pdf.

[18] Peterson, C. et al. (2018), “Lifetime Economic Burden of Intimate Partner Violence Among U.S. Adults”, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 55/4, pp. 433-444, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.049.

[25] Pfitzner, N., K. Fitz-Gibbon and J. True (2020), Responding to the ‘shadow pandemic’: practitioner views on the nature of and responses to violence against women in Victoria, Australia during the COVID-19 restrictions, https://doi.org/10.26180/5ed9d5198497c.

[3] Sardinha, L. et al. (2022), “Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018”, The Lancet, Vol. 399/10327, pp. 803-813, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02664-7.

[22] Schulze, H. and K. Hurren (2021), Estimate of the total economic costs of sexual violence in New Zealand, Business and Economic Research Limited (BERL)/Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC), https://www.acc.co.nz/assets/research/berl-estimate-total-economic-costs-of-sexual-violence-in-new-zealand.pdf.

[11] UNODC/UN Women (2022), Gender-related killings of women and girls (femicide/feminicide), United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime/UN Women, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/Gender-related-killings-of-women-and-girls-improving-data-to-improve-responses-to-femicide-feminicide-en.pdf.

[16] Villagomez, E. (2021), The High Cost of Violence Against Women, https://www.oecd-forum.org/posts/the-high-cost-of-violence-against-women (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[2] WHO (2021), Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256.

[5] WHO (2012), Understanding and addressing violence against women: Intimate partner violence, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77432/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[19] Zhang, T. et al. (2012), An Estimation of the Economic Impact of Spousal Violence in Canada, 2009.

Note

← 1. The term “violence against women” was used in the 2017 and 2022 OECD Reports on the Implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations. This report uses the term “gender-based violence” to expand the scope to all victims/survivors, regardless of age, gender, race, and socioeconomic background. In addition, this term also acknowledges the gendered imbalances of power as a root cause of the phenomenon. However, the report focuses on women and girls, as they constitute the majority of victims/survivors.