This chapter discusses the main trends in the demand for cyber security professionals across Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. The analysis is based on millions of online job postings collected throughout January 2012 and June 2022. Results show that the demand for cyber security professionals outpaced the growth in aggregate demand across the rest of occupations. This chapter also points out the heterogeneity within the demand for cyber security workforce, recognising those roles most demanded on each country. Finally, as a consequence of the quick adoption of new technologies across the world, the chapter discusses the rapid change in the skills enterprises in the cyber security sector are looking for.

Building a Skilled Cyber Security Workforce in Five Countries

2. Tracking the demand for cyber security professionals

Abstract

Introduction: Filling the cyber security workforce gap

Technologies, such as Cloud Computing, Artificial Intelligence (AI) or the Internet of Things (IoT), offer great opportunities for societies to enjoy the benefits of an increasingly interconnected world. New digital tools allow businesses to expand their operations worldwide, increasing productivity and economic gains. However, the use of digital technologies pairs this range of new opportunities with a greater exposure to the risks of cyber attacks,1 since digital platforms and the use of digital tools allow – and need – to share data with third parties, increasing business and organisations’ exposure to potential cybercriminal activities (World Economic Forum, 2022[1]).

The COVID‑19 pandemic also brought new challenges for enterprises as they started implementing remote work arrangements on a large scale to mitigate the effects of lockdowns on economic activity. While many jobs were saved during the lockdowns by teleworking arrangements, working from home can potentially increase the risk of cyberattacks since residential networks have less protection from cyber attacks. According to the 2022 Global Risk Perception Survey from the World Economic Forum, cyber security failures are one of the top 10 risks that have worsened the most since the pandemic and the first within the technological risks group (World Economic Forum, 2022[1]). These are just examples of how the accelerated adoption of new digital technologies during the last few years has considerably increased the risks of data security breaches.

In such a rapidly evolving landscape, economic actors need to be prepared to face new cyber-related challenges that require improved physical resources (i.e. hardware resources for running the specialised software) and protocols for data security but also to develop a skilled workforce that can create, analyse and manage cyber security solutions. Despite the increasing importance that cyber security has gained in recent years, enterprises around the world are still facing a significant shortage of skilled professionals in this area, limiting their ability to contain threats. The (ISC)2 organisation, for instance, recently estimated a world’s cyber security workforce gap of 2.7 million people ((ISC)2, 2021[2]).

Against this backdrop, analysing the most recent trends in the demand for cyber security professionals and understanding the profile of cyber security professionals in high demand can support policy makers in planning adequate education and training policies able to fill the emerging shortages and avoid future shortages across labour markets. Tracking the demand for cyber security skill demands is also key to anticipate future bottlenecks and for businesses and individuals to make informed workforce and training decisions going forward.

This chapter monitors the evolution of the demand for cyber security professionals from January 2012 to June 2022 in five countries: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. This chapter leverages the information contained in nearly 400 million job postings collected from the internet (online job postings, OJPs) by Lightcast2 to fill the knowledge gaps of analyses that relied on traditional labour market statistics, these latter are usually patchy and highly aggregated when it comes to the assessment of the demands for cyber security professionals and skills.

Using the information contained in online job postings has many advantages over traditional data sources such as labour force surveys or national accounting data (Box 2.1). First, OJPs data allow to track the emergence of skill demands in a timely manner as OJPs are collected daily from available jobs posted online. Second, information on skill demands in OJPs is far more granular than in other data sources, allowing to be much more detailed on the specific technologies and skills that are in high demand across the cyber security landscape. OJPs, however, also have some limitations as they may provide less comprehensive coverage of some occupations and sectors where vacancies are not typically advertised through online platforms (see (OECD, 2021[3]); and Cammeraat and Squicciarini (2021[4])). These limitations, however, are likely to be small in the current study as it investigates a specific part of the labour market demand that is typically channelled by online job postings.

The remainder of this chapter is organised in two sections. The first section provides an analysis of the demand for cyber security professionals from different perspectives. On the one hand, it compares the evolution and geographical distribution of cyber security OJPs across countries and reviews within each country how this demand compares to the aggregate demand for the rest of occupations. On the other hand, it exploits the granularity of OJPs data to address other relevant questions. Specifically, it explores the relation between the demand for cyber security professionals and that for other digital professions in a context of rapid digital transformation. Moreover, it identifies specific cyber security roles and reviews their demand across time. The second section, instead, provides insights into the main characteristics of jobs for cyber security professionals, leveraging information contained in firms’ requirements to access the job. The section provides insights on the qualifications and education levels typically required to access the profession and the bundles of skills most relevant for cyber security professionals. It also provides information about earnings offered to potential applicants across countries as reported in OJPs.

Box 2.1. Methodological note: Interpreting the results from online job postings

The wealth of information contained in job postings can offer a very detailed overview of the demand of enterprises for cyber security profiles. This box summarises the main methodological approaches used to leverage these data in order to improve readability of the results and insights shown below. More details are also contained in Annex 2.A and in the footnotes to each figure.

Using OJPs to track the evolution of demand

Trends in the volume of OJPs: To show the evolution in the amount of OJPs throughout the period of analysis, this report uses a standardised index of the monthly count of job postings. This index takes the value of 100 in January 2012, except for New Zealand where it starts in January 2013 due to data availability. A polynomial trend is calculated on this index to reduce noise.

Cyber security roles: Using the job titles available in OJPs, this chapter identifies different cyber security roles (Analysts, Architects and engineers, Auditors and advisors, Managers) and tracks the evolution of their demand. Job titles are used in a first stage as an input to get the most frequent keywords used by recruiters to name the positions offered and then, in a second step, these keywords are used to define role groups in which each job posting is classified.

Groups of digital, engineering and math related occupations: The analysis provides insights on more than 40 occupations used to compare the trends in their demand with the demand for cyber security professionals. The 40+ occupations were classified in four occupational groups: Chief Information Officers, Computer-based professions, Math-related professions and Engineers and technicians.

Using OJPs to infer skill demands

Skill bundles: Using Natural Language Processing (NLP) approaches, the analysis in this chapter identifies the most relevant skills in employer’s demands for cyber security positions collected through OJPs. As detailed also in Box 2.3, this “skill relevance” index should be interpreted as a measure of relevance of a given skill in the cyber security profession. In this context is also important to notice that keywords collected from OJPs do not only represent skills strictu sensu. Some of them, for instance, are technologies or tools (i.e. Python or Microsoft Azure), while others identify knowledge areas (i.e. Network or Information Security). For the sake of simplicity, this study pools all keywords together under the term “skills” and only differentiate between them if necessary.

The demand for cyber security professionals

The impact that the digital transition is having on labour markets is a reality that has attracted a lot of attention in recent years. A recent study (OECD, 2022[5]), for instance, shows the significant increase in demand for digital professionals across labour markets as well as the increasing pace by which digital technologies are permeating workplaces, spreading across an increasing number of different sectors and occupations. Cyber security professionals are one amongst the many digital occupations that have shown strong growth recently, reflecting the fast-paced adoption of digital technologies in the workplace and in productive processes.

The cyber security profession3 encompasses a wide variety of different roles and jobs. Most professionals in this area are in charge of securing data, systems, infrastructure and other cyber resources from failures, hazards and cyber threats that affect an organisation mission and operation (World Economic Forum, 2022[6]). This section focus on tracking the demand for professionals in this area in each country using the online job postings classified in this occupation following the Lightcast taxonomy.

What has been the evolution of the demand across countries?

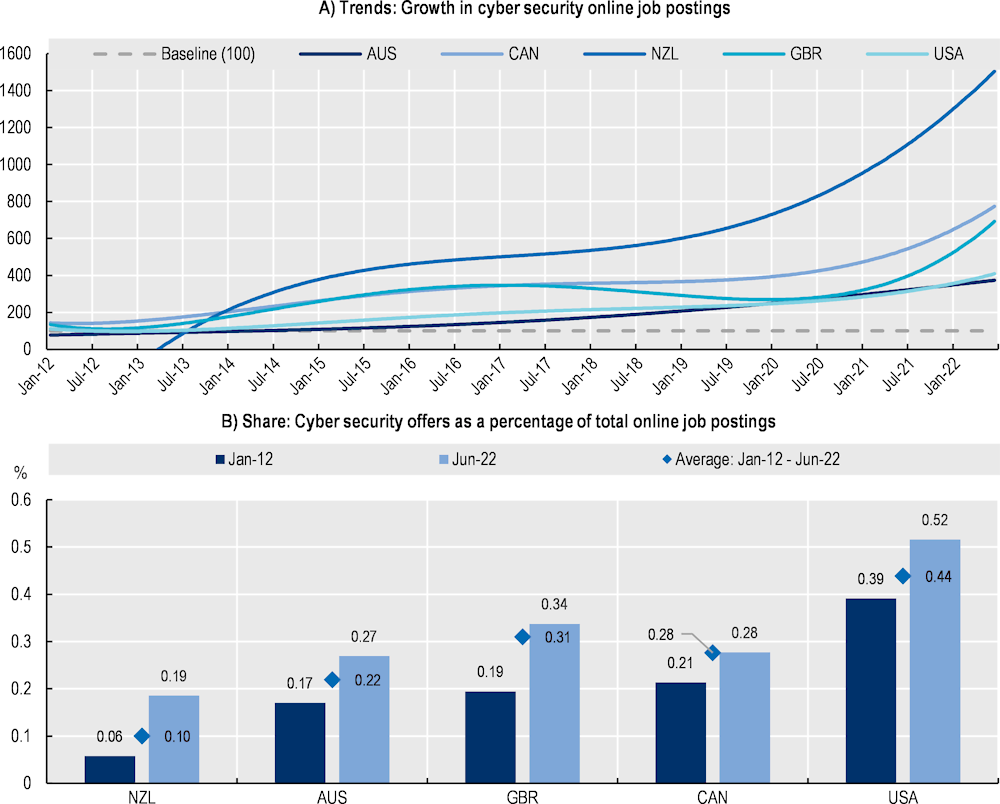

Figure 2.1 (Panel A) shows the trends exhibited by a standardised index calculated on the monthly count of job adverts. This index allows for easier comparison across countries over the time. In line with the fast-paced digital transformation of labour markets (OECD, 2022[5]), the analysis of OJPs in Figure 2.1 (Panel A) shows that the monthly demand for cyber security professionals has been significantly increasing in the last decade in the five countries covered in this report. In June 2022, for instance, the volume of new job adverts in the cyber security domain was between three to 16 times the number of recorded job postings at the beginning of 2012, almost double the speed of expansion recorded for all new job postings in the same period. The pace by which the demand for cyber security professionals has grown, however, differs by country.

While growth in demand has been positive across all geographies, results in (Figure 2.1, Panel A) seem to suggest that the COVID 19 pandemic may have partially affected the demand for cyber security professionals in early 2020. Since 2021, as economies started to open up again after the severe economic shock imposed by the pandemic, the demand for cyber security professionals has started increasing again significantly and at a much faster pace than in the pre pandemic period. This result is likely reflecting the expansion of remote working activities around the world, which imposed new technological challenges for enterprises that faced increased cyber security threats. Results for the United Kingdom, in particular, show a decreasing trend in OJPs for cyber security professionals between January 2017 and July 2020, earlier than in other countries. This is likely to reflect the effects of the political developments happening in the United Kingdom during the Brexit negotiations that led to increased uncertainty in the transition phase as the reduction in OJPs starting in 2017 is widespread and not exclusive to the cyber security jobs (see Figure 2.2, Panel D).

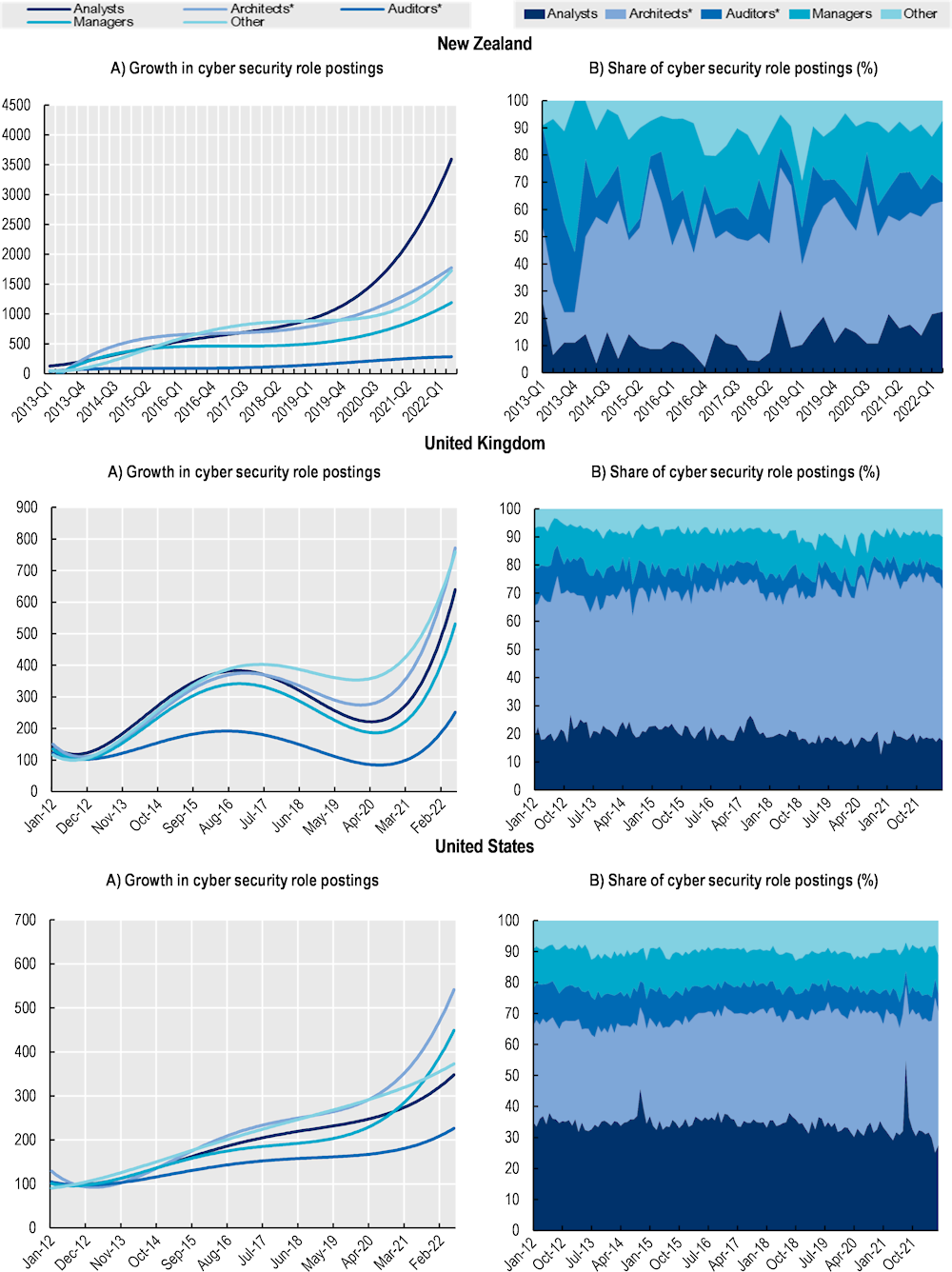

Figure 2.1. Cyber security Online Job Postings: Trends and shares

Polynomial trends calculated on a standardised index (Jan‑12 = 100) of the monthly count of job postings

Note: For Panel A, polynomial trends are calculated on a standardised index (Jan‑12 = 100) for the monthly count of job postings. This index shows the evolution in the demand for a given profession in comparison to this month. Data for NZL starts on January 2013.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Overall, results in Figure 2.1 (Panel A) suggest that the growth in demand for cyber security professionals in New Zealand and Canada has been the strongest in the period between January 2012 and June 2022, followed by the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. While this figure suggests a slower growth in the demand of cyber security professionals in the United States relative to other geographies, this result can be partly explained by the largest size of the United States’ cyber security market in 2012 relative to that in other countries.

In January 2012, the job postings seeking cyber security professionals in the United States accounted already for roughly 0.4% of total job postings in the same month (Figure 2.1, Panel B). This figure is almost twice the share of postings in the United Kingdom market and more than 6 times that in New Zealand. Results indicate, in other words, that the United States was already a much more mature cyber security labour market in 2012 and, while the growth in the following years has still been positive and above the average of other professions, this was slower than in other countries where the market started to develop much more strongly in later years. Differences in the size of the cyber security market at the beginning of the period are likely to explain some of the differences in the rate of growth in more recent years, where countries that were lagging in absolute volume of cyber security vacancies have started to catch up with more mature economies like the United States. Other factors, however, may be playing important roles in the overall evolution of the demand across countries. These are analysed in the following sections.

How does the demand for cyber security professionals compare with other occupations?

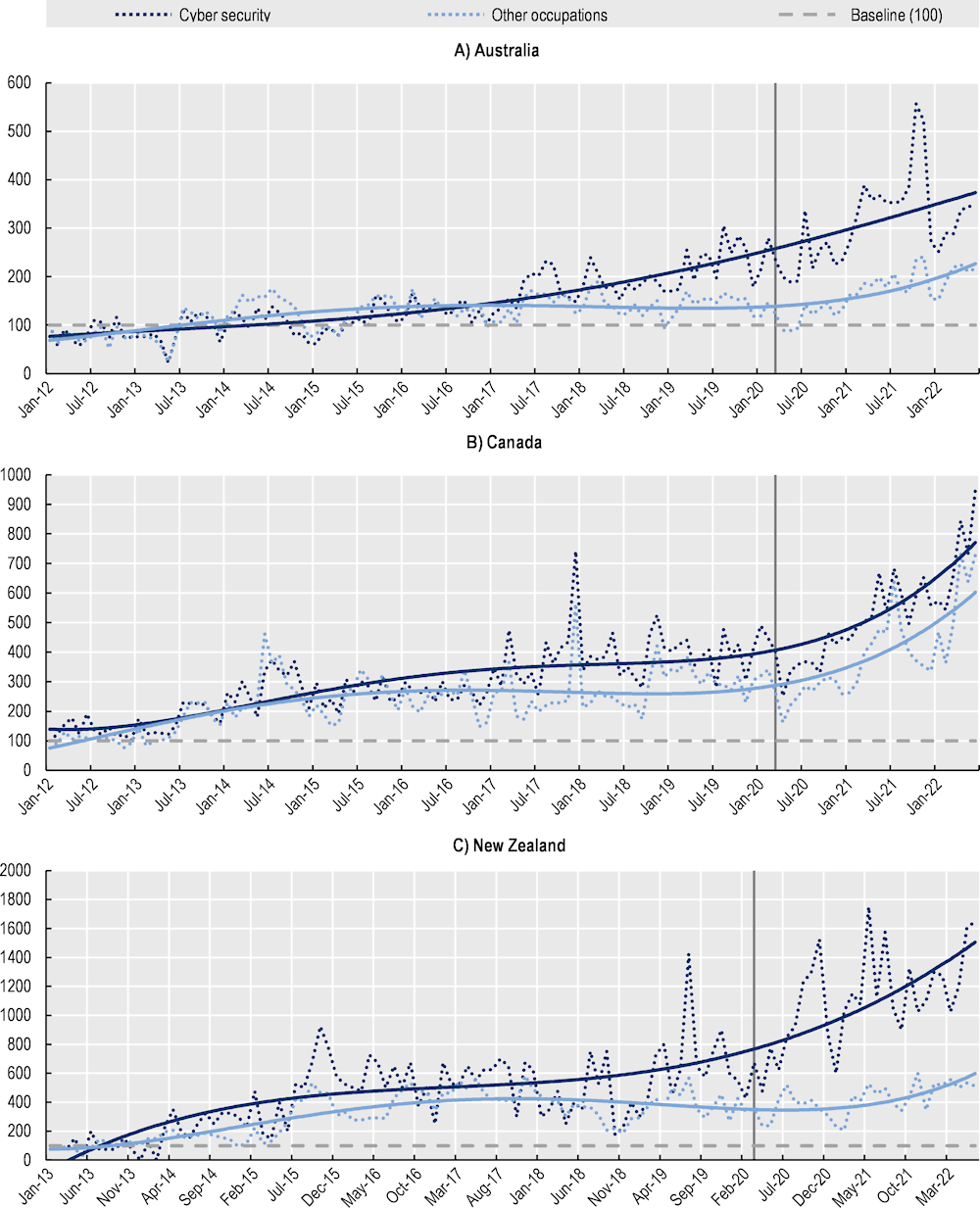

A particularly relevant question relates to how the demand for cyber security professionals compares to the rest of professions and to the overall dynamics of job vacancies. Figure 2.2 shows the standardised indexes capturing the demand for cyber security professionals and compares the trends with that for the rest of occupations. In the countries covered, the growth in demand for cyber security professionals significantly outpaced the aggregate demand across other occupations. Different patterns, however, can be observed across countries.

In the United States (Figure 2.2, Panel E), for instance, the demand for cyber security professionals has closely followed the evolution in other occupations, although it has grown faster in most of the period. The most notable differences, in favour of cyber security demands over the total economy, can be observed in the period 2016‑19 and, particularly, in 2022 where the demand for cyber security professionals has been relatively stronger. Demand for cyber security professionals only slowed in the United States during the pandemic, with a strong dip in May 2020 despite a rapid rebound afterwards.

In Canada and the United Kingdom, the growth in demand for cyber security professionals significantly exceeded that of other occupations. Starting in early 2014 (2015 for Canada), the demand for cyber security roles increased faster than in the rest of the occupations in both countries. Analyses of cyber security sectoral demand carried out in the United Kingdom in 2021 confirm that, during the period 2017 19, the sector experienced double digit growth with an estimated employed workforce growth of nearly 50% (Ipsos MORI, Perspective Economics, CSIT, 2021[7]). Despite this remarkable growth in the United Kingdom, it is also noticeable that the gap between the growth of job postings for cyber security professionals and those for the rest of professions shrunk during the 2017‑20 period. As pointed out before, the declines in the volume of cyber security job postings can reflect the uncertainty related to political developments such as Brexit’s negotiation process as well as the most recent and unprecedented shock related to the COVID 19 pandemic. Figure 2.2 suggests that these events could have had a stronger effect on the demand for cyber security professionals than for the rest of the occupations.

During Brexit, in particular, concerns about the negative impacts on the cyber security sector emerged due to the uncertain consequences on corporation’s investment decisions in the United Kingdom and the potential reduction in the number of cyber security professionals willing -and able to arrive to work in the sector (Stevens and O’Brien, 2019[8]). In fact, according to the EY Financial Services Brexit Tracker, between March 2017 (after the triggering of Article 50) and March 2021 the proportion of firms that announced plans to move some operations or staff from the United Kingdom nearly doubled, from 24% to 43%. Additionally, 24 firms declared they will transfer more than GBP 1.3trn of UK assets to the EU (EY, 2022[9]). This context potentially affected the hiring decisions of companies looking for cyber security professionals.

In Australia and New Zealand, the number of new job postings for cyber security professionals has steadily increased since 2017, continuously widening the growth gap with the rest of professions. Notably in these countries, the pandemic in 2020 does not seem to have affected the demand. On the contrary, in the period following the declaration of the pandemic the differences in the demand for cyber security and other occupations has increased. This trend can be explained, to a certain extent, by the expansion of remote work arrangements during the pandemic which led to an increasing demand for cyber security solutions across a wide range of businesses. The Australian Cyber Security Growth Network indicates, for instance, that during 2020 medium-sized cyber security providers recorded significant increases in their revenues (+21.6%), while small-sized enterprises reported moderate decreases (-5.1%) and large companies revenue remained unaltered (0.1%). In the same survey, only 13% of the enterprises reported a decrease in their workforce, while 18% reported an increase (Australian Cyber Security Growth Network, 2020[10]).

Figure 2.2. Growth in online job postings: Cyber security and all occupations

Polynomial trends (solid lines) calculated on a standardised index (Jan‑12 = 100) of the monthly count of OJPs

Note: The standardised index shows the evolution in the demand for a given profession in comparison to the month of reference. Data for NZL starts on January 2013. Vertical line reflects the declaration of COVID‑19 as pandemic (March 2020).

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

A geographical view of the demand for cyber security professionals

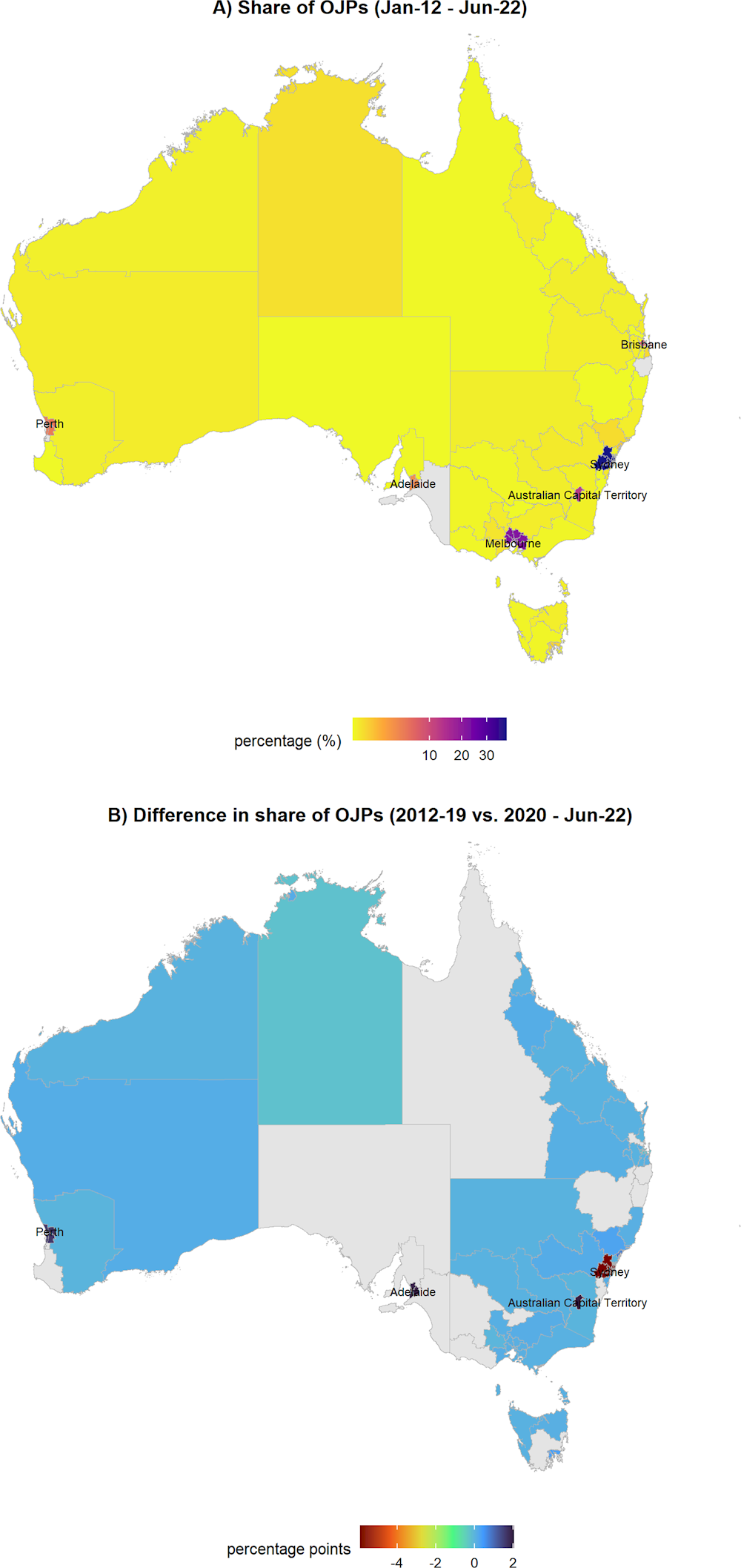

The granularity of job postings data offers a unique opportunity to assess the geographical dimension of the demand for cyber security professionals by investigating the distribution of cyber security-related job postings within a country and assessing the degree of geographical concentration of such demand. In particular, data on job postings allows an assessment of how the geographical distribution of cyber security demand has evolved in recent years and whether the concentration in the demand has increased or, else, spread out even further, with lagging regions catching up in the demand.

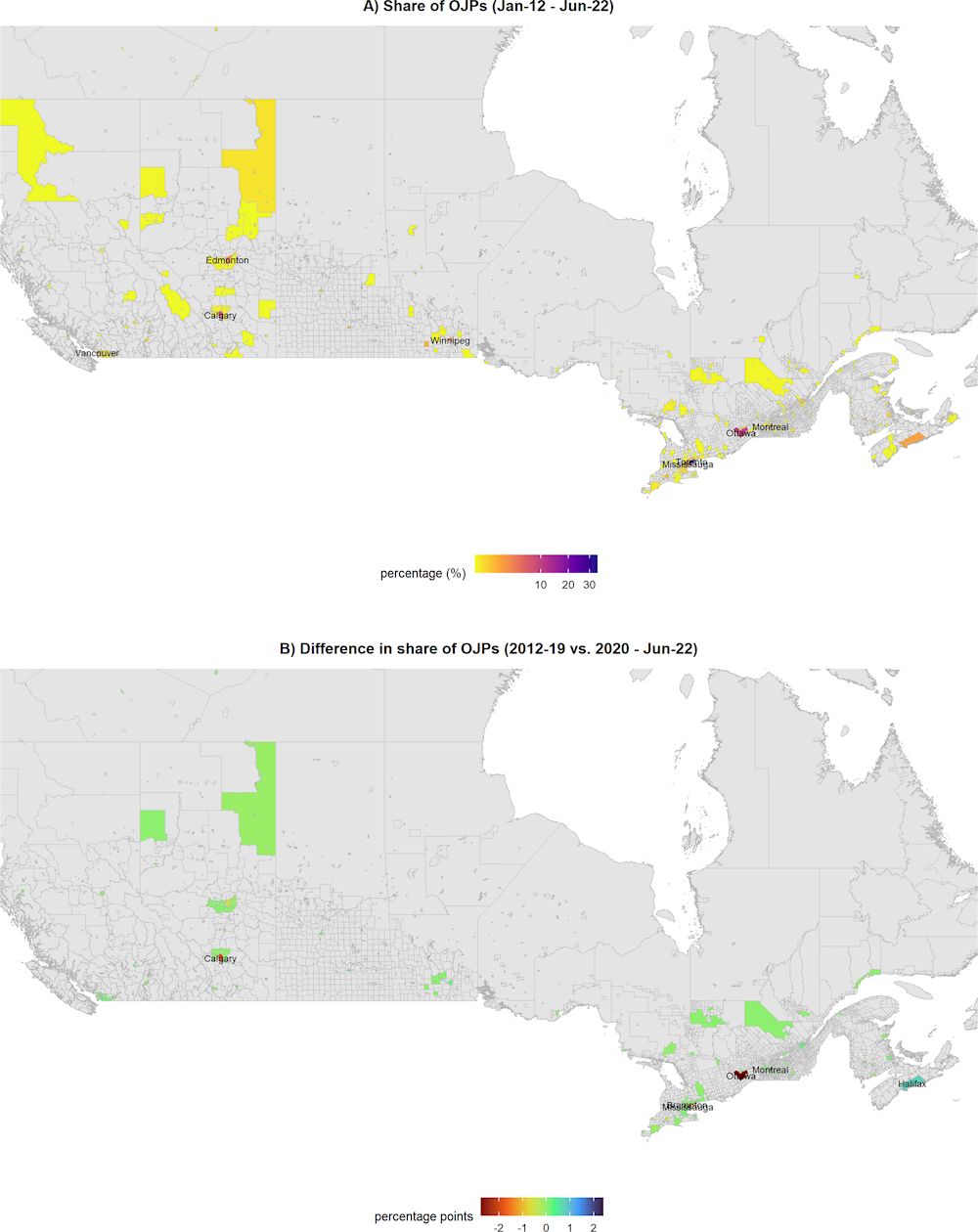

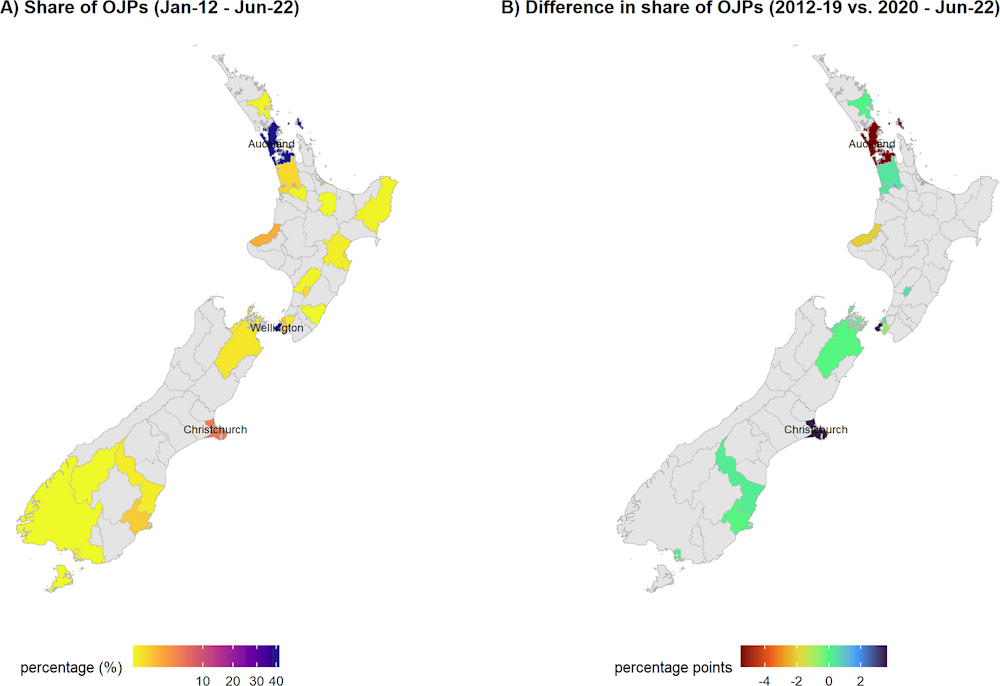

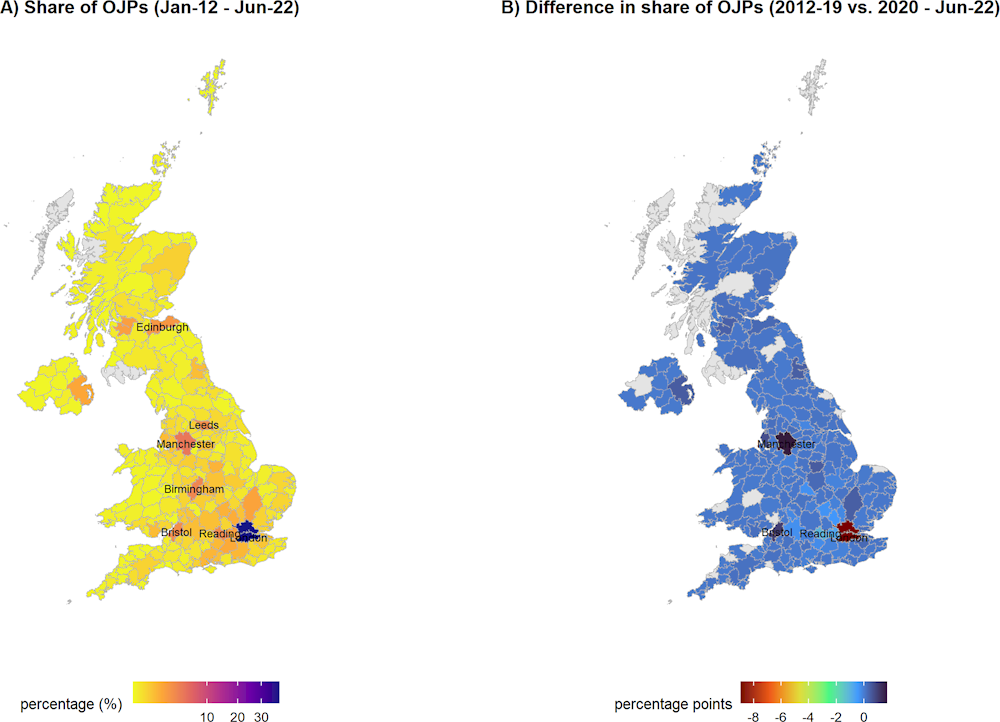

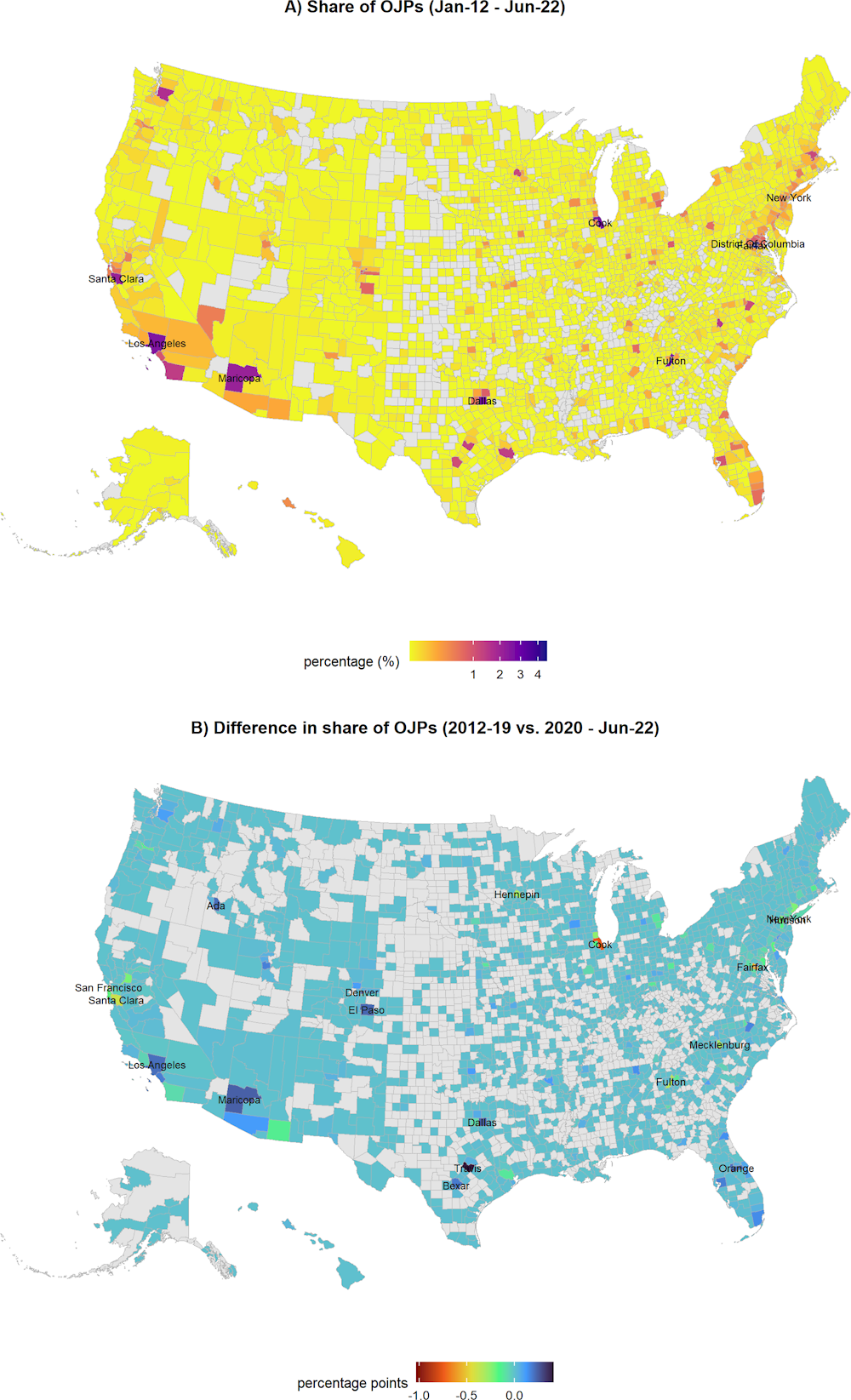

Using the geographical location available in OJPs, Figure 2.3 to Figure 2.7 show two maps for each country examined:

1. Map A shows the average share of job postings for cyber security professionals in each geographical area (see Box 2.2) relative to the country’s total number of cyber security OJPs over the period between January 2012 and June 2022.4

2. Map B captures the evolution over time and geographies by showing the change in percentage points of the share of cyber security OJPs, relative to the total country’s volume of cyber security OJPs, during the periods 2012‑19 and 2020‑June 2022 to distinguish between older and more recent trends in the geographical distribution of the demand for cyber security professionals.

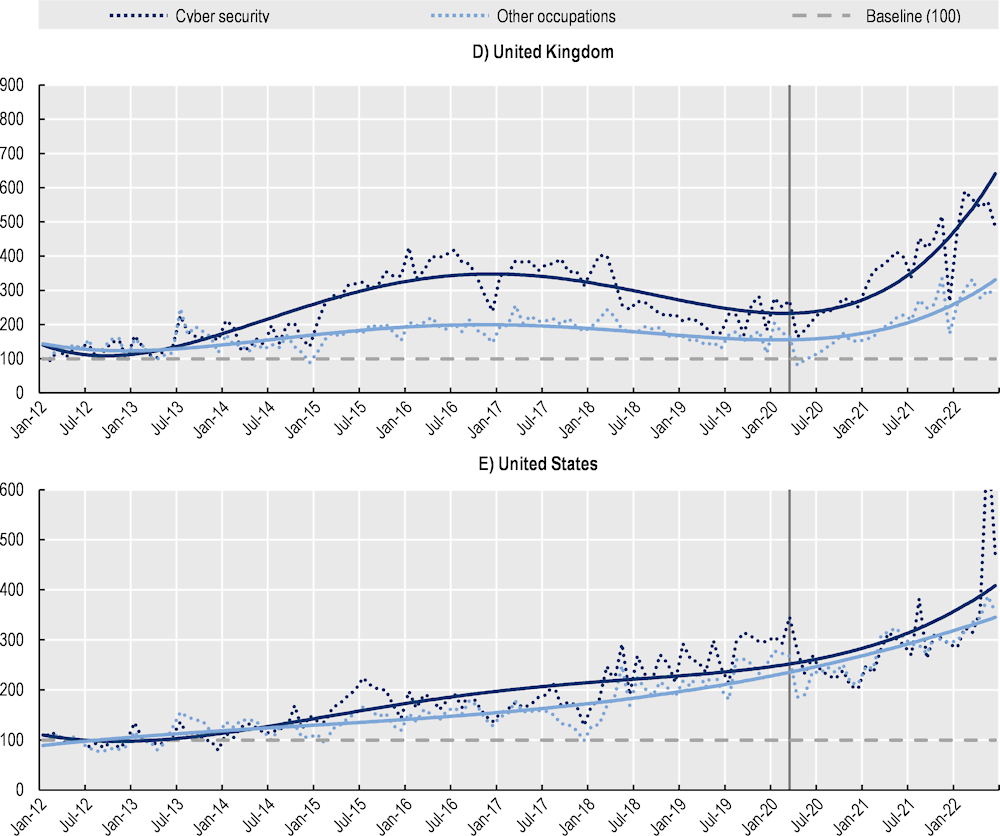

Generally, across countries, results show that most of the jobs postings for cyber security professionals are in large urban areas or economic centres where also major enterprises and governments agencies’ headquarters are located. In these areas, global interconnectivity in financial, industrial, government and other sectors increasingly require the availability of secure IT services and infrastructure, as well as of a talented workforce that can protect their businesses.

Figure 2.3 (map A) shows the share of OJPs for cyber security professionals across the Australian territory divided by statistical areas Level 4 (SA4). Areas located in the southeast of the country gather most of the job postings for cyber security professionals over the period of analysis (January 2012-June 2022). Sydney, as the financial and economic centre of Australia, stands out as the area with the highest share of cyber security job postings with roughly 40% of the total. Melbourne and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), where the headquarters of the Australian Government are located, follow with 22% and 12% of total cyber security job postings respectively. Similarly, Figure 2.5 (map A) shows that a high proportion of cyber security job postings in New Zealand are concentrated in the cities of Auckland and Wellington. Following the same pattern seen in Australia, economic and political centres in New Zealand account for most of the cyber security job adverts, as these two cities represent 83% of the job postings for this profession (41% and 42% respectively). Christchurch, in the South Island completes the top‑3 geographical locations with 7% of the job postings in New Zealand.

Other countries show a distribution that is even more concentrated than in Australia and New Zealand. Figure 2.4 (map A) presents the cyber security job postings shares in the Canadian territory divided by cities. The cluster Toronto-Mississauga-Markham makes roughly 40% of the job postings for cyber security workforce. Ottawa (9%), the political centre, Montreal (9%), Calgary (7%) and Vancouver (6%) follow in the raking with significantly smaller shares and concentration of job postings than Toronto.

In the United Kingdom (Figure 2.6, map A), London accounts for 38% of the cyber security job postings, followed by Manchester (5%) and Birmingham (3%). The importance of the latter relies on its position as second largest city in the United Kingdom (by population) and for its strong demand for workers in IT-related positions. Edinburgh and Glasgow together represent 3% of total OJPs for cyber security, while Belfast and Cardiff respectively account for 0.7% and 0.5% of the cyber security OJPs posted in the United Kingdom during January 2012 – June 2022.

The United States is the only exception to such highly concentrated distribution of the demand for cyber security workforce. Figure 2.7 (map A) shows the United States map divided by counties. The areas of Fairfax and the District of Columbia (DC) are at the top of the ranking by number of OJPs for cyber security professionals with 4.6% and 3.4% of the job postings, respectively. Both areas play an important role as home to the headquarters of federal government institutions. In the case of Fairfax, the strong relative demand for cyber security professionals is likely related to this city being home to key intelligence and national security institutions, such as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Other economic centres across the country closely follow the federal government areas, such as New York (3.3%), Cook County (Chicago) (2.7%), Fulton County (Atlanta) (2.6%), Dallas (2.5%), Los Angeles (2.5%) and Santa Clara (2.1%).

The less geographically concentrated distribution of cyber security job postings in the United States can be traced back to several factors intertwining productive structure, technological leadership and adoption of digital technologies. In particular, the US federal administrative structure may imply the establishment of state level cyber security institutions which can be reflected in a more spread geographical distribution of the demand. Additionally, a relatively a more digitally-mature economic structure and a stronger cyber security capacity (see IMD World Competitiveness Center (2022[11]) and International Telecommunications Unit (2020[12])) have likely contributed to the demand for cyber security professionals being more spread out across a wider set of productive sectors and, hence, across geographies earlier than in other countries.

Figure 2.3. Australia: Geographical distribution of cyber security job postings (2012‑22)

Note: Grey areas indicate non-available information. Names are shown for areas with higher share of job postings (map A) or with higher change (positive or negative) between the two periods (map B).

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data. Digital boundary file downloaded from Australia Bureau of Statistics (Jul2021-Jun2026[13]), https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3/jul2021-jun2026/access-and-downloads/digital-boundary-files licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

Figure 2.4. Canada: Geographical distribution of cyber security job postings (2012‑22)

Note: Grey areas indicate non-available information. Names are shown for areas with higher share of job postings (map A) or with higher change (positive or negative) between the two periods (map B). Given the location of job postings, a zoom into the southern area of Canada is provided to improve readability.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data. Digital boundary file adapted from Statistics Canada (2022[14]), https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/geo/sip-pis/boundary-limites/index2021-eng.cfm?year=21. This does not constitute an endorsement by Statistics Canada of this product.

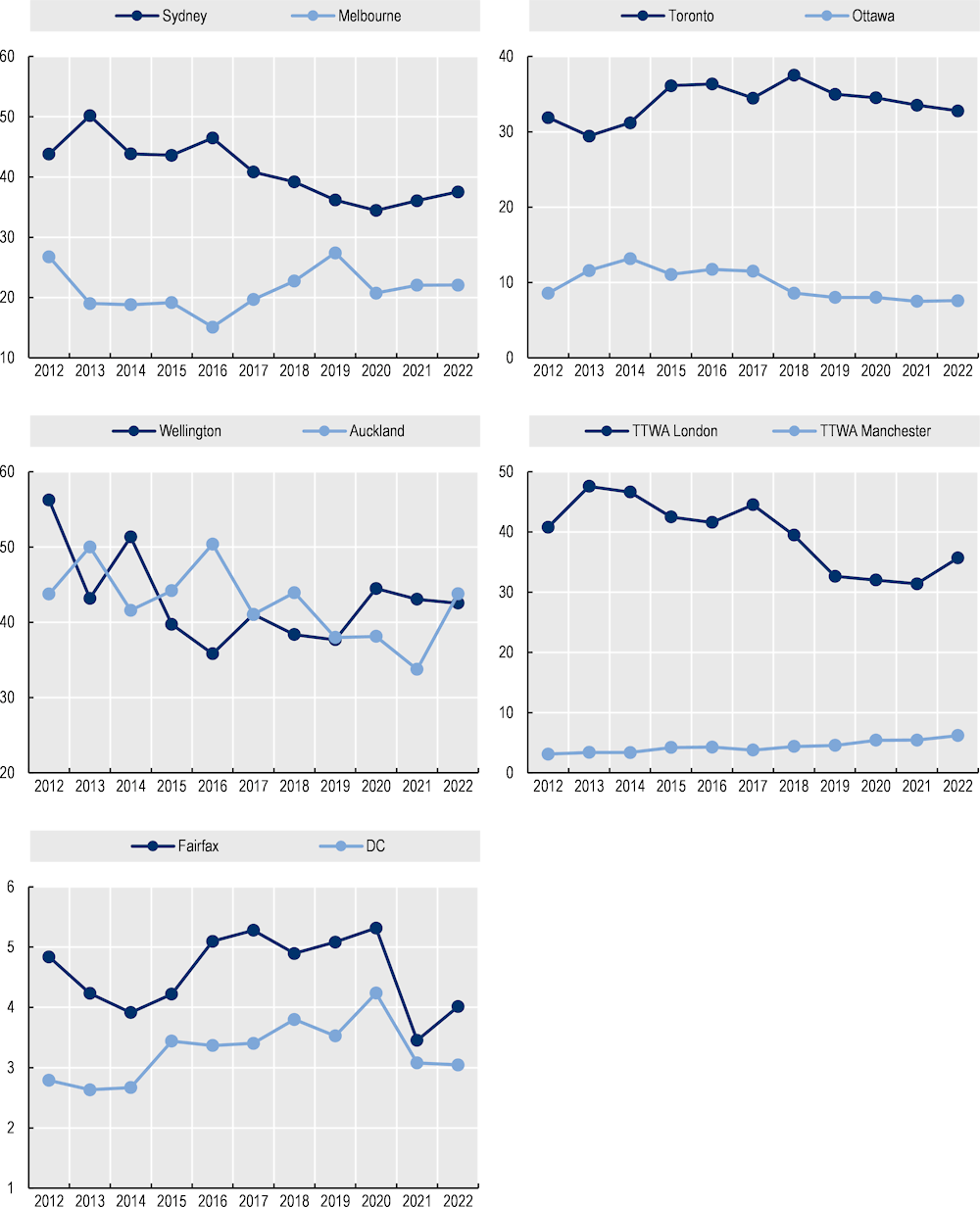

Notably, even though across most countries a large share of OJPs for cyber security professionals still remain in administrative capitals and main cities, in the last two years (January 2020 - June 2022) the geographical concentration of cyber security job postings in those economic poles has decreased significantly compared to the 2012‑19 period. Figure 2.3 (map B) shows, for instance, that the share of cyber security job postings in Sydney shrunk by roughly 6 percentage points from 42% in 2012‑19 to 36% in 2020‑22. Conversely, the ACT, Adelaide and Perth grew approximately 2 percentage points each between the same two periods. In a more detailed view, Figure 2.8 (Panel A) shows that Sydney’s yearly share decreased continuously during 2017 and 2020, while Melbourne’s share increased consistently during the same years, except during the pandemic in 2020. The opposite direction of the two trends for Sydney and other cities in Australia suggests that in the last years, smaller centres have been growing their demand for cyber security professionals, as firms and organisations in those territories are increasingly adopting digital technologies and facing the risks of cyber attacks.

Figure 2.5. New Zealand: Geographical distribution of cyber security job postings (2012‑22)

Note: Grey areas indicate non-available information. Names are shown for areas with higher share of job postings (map A) or with higher change (positive or negative) between the two periods (map B). Given the location of job postings, the map is focused on the mainland (North and South islands) in order to improve readability.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data. Digital boundary file downloaded from Stats New Zealand (2023[15]), https://datafinder.stats.govt.nz/layer/92215-territorial-authority-2018-clipped-generalised/ licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

In the United Kingdom, the share of cyber security job postings in London declined by 9 percentage points from 42% to 33% between the two periods (Figure 2.6, map B). Conversely, the share of job postings published in Manchester increased by 2 percentage points to 6%, the highest increase in the United Kingdom, followed by Bristol with an increase of 1 percentage point to 4%. The increase in the demand in the Bristol area is likely to be related with its proximity to the government Communication Headquarters (GCHQ), the parent organisation of the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). Similarly to the dynamics in Sydney, Figure 2.8 (Panel D) for the United Kingdom shows that the yearly share of cyber security job posting in London has decreased consistently from 2017 onwards, except in 2022. The negative trend in London is paired with the steady increase in Manchester’s share of cyber security job postings between 2017 and 2022, signalling the significant growth in the demand in the latter, possibly linked to the recent local strategies, such as the Manchester Digital Security Hub (DiSH) (Greater Manchester Combined Authority, 2021[16]).

In Canada results are more mixed. The share of cyber-related job postings in the area of Toronto has remained stable between the two periods (a decrease of 1 percentage point in Toronto is offset by a similar increase in Mississauga). Meanwhile, Montreal experienced the highest increase in the country, going from a share of OJPs of 8% to 11% relative to the total. Nevertheless, Ottawa and Calgary reduce their cyber security job postings shares by 3 percentage points and 2 percentage points, respectively. Figure 2.8 (Panel B) shows a decreasing trend in Ottawa’s share since 2014 that contrasts with significant increases in Toronto’s share in 2015 and 2018.

In the case of the United States, changes in the distribution of the demand for cyber security professionals are relatively smaller (Figure 2.7, map B). The economic and financial centres of New York and Cook County (Chicago) experience a decrease in their shares of approximately 1 percentage point to 3% and 2% respectively. DC and Fairfax shares remain stable. However, Figure 2.8 (Panel E) exhibits that both areas suffered a significant decrease in their relative demand during 2021, a result that may respond to measures taken during the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Figure 2.6. United Kingdom: Geographical distribution of cyber security job postings (2012‑22)

Note: Grey areas indicate non-available information. Names are shown for areas with higher share of job postings (map A) or with higher change (positive or negative) between the two periods (map B).

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data. Digital boundary file downloaded from the Office for National Statistics (2019[17]), https://geoportal.statistics.gov.uk/datasets/ons: travel-to-work-areas-dec-2011-bfe-in-united-kingdom/explore?location=55.215431%2C-3.313445%2C6.09 licensed under the Open Government Licence v.3.0.

Figure 2.7. United States: Geographical distribution of cyber security job postings (2012‑22)

Note: Grey areas indicate non-available information. Names are shown for areas with higher share of job postings (map A) or with higher change (positive or negative) between the two periods (Map B). Sizes of Alaska and Hawaii states are adjusted for readability reasons.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data. Digital boundary file used under the R library “urbanmpr” from the Urban Institute (2019[18]), https://github.com/UrbanInstitute/urbnmapr. Code released under the GNU General Public License v3.0.

Figure 2.8. Yearly evolution of cyber security job posting shares: Main areas per country

Areas’ share over the total amount of cyber security OJPs per country and year (as a percentage)

Note: TTWA refers to Travel to work Areas in the United Kingdom (see Box 2.2).

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

The decreasing geographical concentration of cyber security related OJPs in main urban areas of most of the countries analysed suggests that as a country moves towards increasing adoption of digital technologies throughout their subnational geographies, cyber security markets become more mature, leading to an increase in the demand across the territory and a demand for cyber security professionals that is geographically less concentrated.

Box 2.2. Geographical information in Lightcast datasets

Data on job postings include different variables for indicating the geographical location of a job offer, ranging from broad indicators, such as the country name or main regions/provinces, to more detailed ones, such as the longitude and latitude co‑ordinates. In order to show the demand for cyber security professionals in a more detailed view, Figure 2.3 to Figure 2.7 exploits information about the location of job postings in sub-national boundaries. Following, it is explained the geographical level used for each country and the source of the boundaries file used:

Australia

Data is presented for the Statistical Areas Level 4 (SA4). According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022[19]), “SA4s are the largest sub-state regions in the Main Structure of the [Australian Statistical Geography Standard] ASGS and are designed for the output of a variety of regional data, including data from the 2021 Census of Population and Housing”. Lightcast data includes the SA4 code for each job posting without specifying employment centres inside larger cities. Thus, several SA4 areas around cities, such as Sydney or Melbourne, are showed as they were only one. The digital boundaries file was retrieved from the Australia Bureau of Statistics (Jul2021-Jun2026[13])

Canada

Data on OJPs for Canada specifies two levels of geographical disaggregation: Provinces/territories and census subdivisions (municipalities). In order to show more granular results, maps for Canada are presented at the municipalities level, according to the classification provided by Lightcast. The digital boundaries file was retrieved from Statistics Canada (2022[14]).

New Zealand

In this case, the analysis was conducted at the territorial authorities’ level, since Lightcast data only includes information for this level of geographical disaggregation. This is the second level of local government in New Zealand. The digital boundaries file was retrieved from Stats New Zealand (2023[15]) and focuses on the mainland (North and South islands).

United Kingdom

Data is shown at the Travel to Work Areas (TTWA) level. TTWA are the official British definition of local labour market areas. They are defined by the UK Office for National Statistics using workers’ residence and workplace areas. Its latest update was in 2011 and comprehends 228 areas. The boundaries file was retrieved from the Office of National Statistics (2019[17]).

United States

Data is at the county level for the United States. In this case, the boundaries file is directly retrieved from an R package called “urbnmpr” from the Urban Institute (Strochak, Ueyama and Williams, 2022[20]). See also the Urbnmpr web page in GitHub for more detail (Urban Institute, 2019[18]). This package has the advantage of using maps from the US Census Bureau and includes Alaska and Hawaii in a reduced scale to facilitate the map display.

What is the relationship between the demand for cyber security professionals and that of other digital, engineering and math-related occupations?

The expansion of the demand for cyber security professionals in the last years responds to increasing concerns related to the strategic development of companies and the vulnerability of their systems in a landscape of rapid digital transformation. These concerns have emerged due to the expansion of artificial intelligence and remote working across a variety of sectors. In the Global Cybersecurity Outlook 2022, the World Economic Forum (2022[6]) surveyed 120 global leaders in the cyber security sector, finding that the factors with the greatest influence in organisations’ approach to cyber security are the digital transformation, cyber attacks to third-party enterprises (i.e. service providers, suppliers, contractors, etc.) and regulatory requirements. Moreover, in the same survey, experts state that two of the more influential trends in the future for cyber security would be the implementation of automation and machine learning, and the expansion of remote/hybrid work environments (World Economic Forum, 2022[6]).

The digital transition (OECD, 2022[5]) and the expansion in the demand for digital-related occupations across labour markets is, hence, very likely to be a key driver for the increase in the demand for cyber security professionals as firms adopt new digital technologies that are potentially threatened by vulnerability, attacks and malwares.

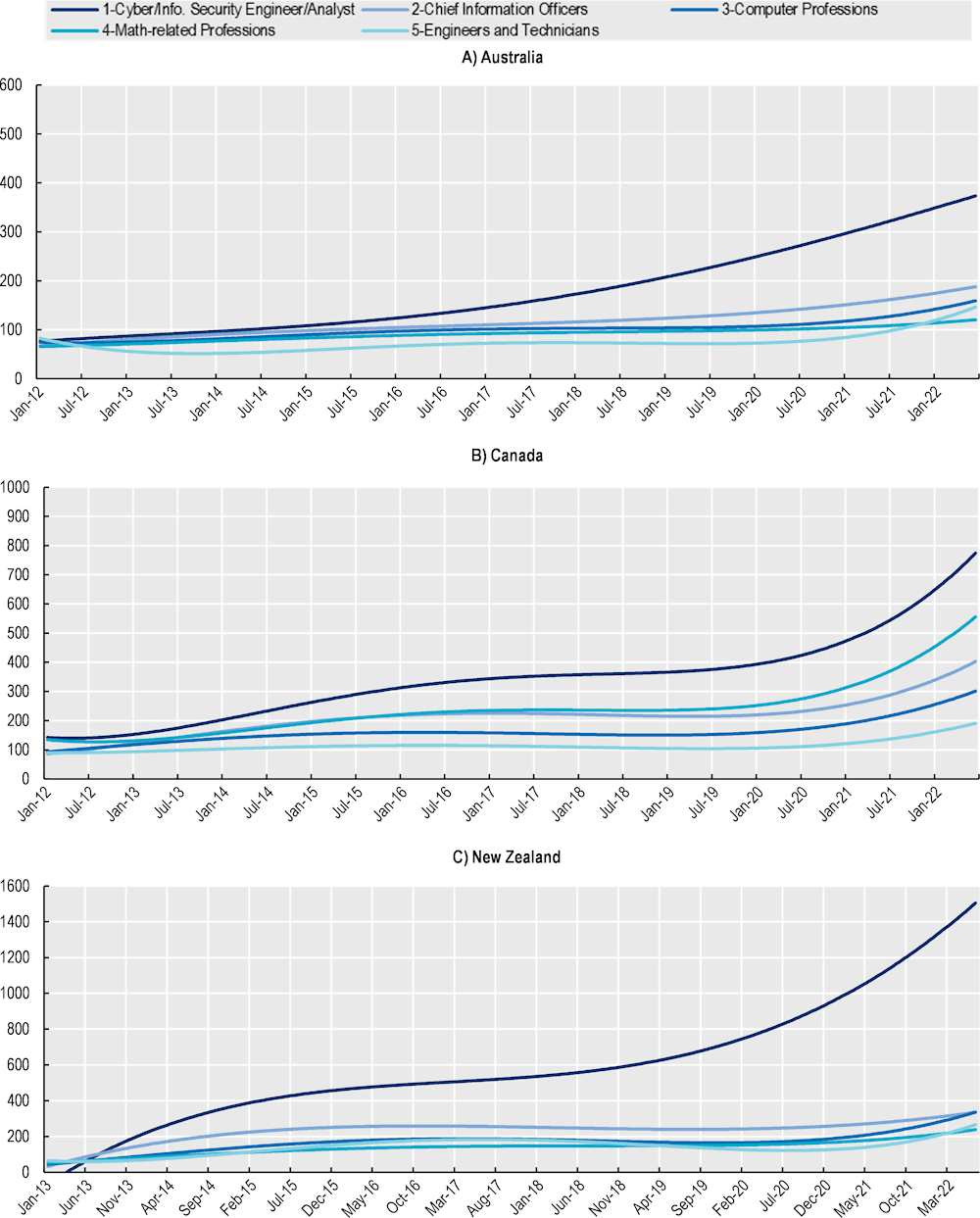

This section analyses more than 40 occupations that are gathered in four occupational groups (Chief Information Officers, Computer-based professions, Math-related professions and Engineers and technicians) to compare the dynamics in their demand with that for cyber security professionals (for more detail on the occupations selected and groups see Box 2.1 and Annex 2.A). For each country, Figure 2.9 shows the bird-eye view of the trends calculated on the standardised monthly growth of OJPs for each group, comparing them with the evolution of job postings for cyber security professionals.

When focusing on the evolution of OJPs trends, results in Figure 2.9 show that the demands for cyber security and that for digital professionals move closely together in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. The average correlation index between the growth in cyber security occupations and digital occupations is strong: +0.63 for the United Kingdom, +0.68 for Canada and +0.8 for the United States. While demand for digital, engineering and math professionals has grown very strongly in all countries (OECD, 2022[5]), results in Figure 2.9 reveal that, in the five countries analysed in this report, the demand for cyber security professionals has been growing at a significantly faster pace than that for other digital-related5 occupations.

The size of the gap between cyber security and other digital, engineering and math- professionals, however, varies significantly among countries. In Australia and New Zealand, for instance, demand for cyber security professionals significantly exceeded that of the rest of occupations considered throughout the period between January 2012 and June 2022. In Australia, the volume of job postings for cyber security professionals over the total of digital/engineering and math occupations has tripled between 2012 and 2021, going from 1.3% to approximately 3%. Among the possible explanations behind this significantly faster growth in the demand for cyber security professionals in Australia and New Zealand is the relative smaller volume of OJPs for this profession in 2012 compared to those from other countries (see Figure 2.1).6 As the demand for cyber security in Australia and New Zealand catches up to the levels of other major OECD economies, it experience faster growth rates when transitioning to become more mature markets for cyber security professionals.

Figure 2.9. Growth in online job postings: Cyber security and other digital, engineering and math-related professions

Polynomial trends calculated on a standardised index (Jan‑12 = 100) for the monthly count of job postings

Note: The standardised index shows the evolution in the demand for a given profession in comparison the month of reference. Data for New Zealand starts in January 2013.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

As mentioned above, the digital transition is pushing firms to adopt new digital technologies and workers to use digital tools and devices in virtually all productive sectors. The increase in the demand for a broad range of digital professionals, stemming from the adoption of a variety of new digital technologies, is behind the contextual growth in the demand for cyber security experts as well, as these latter represent the barrier protecting the work of other digital professionals from vulnerabilities of all sorts. The information contained in online job postings allows to investigate what occupations are more tightly linked to the demand for cyber security professionals across the countries analysed.

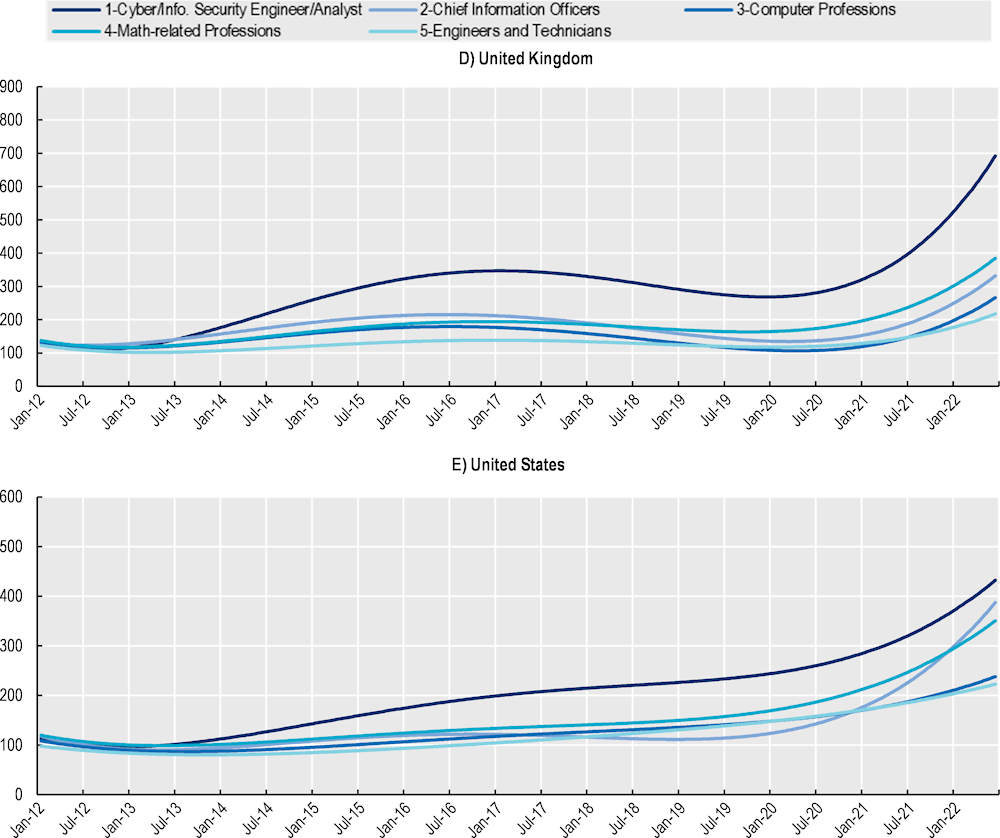

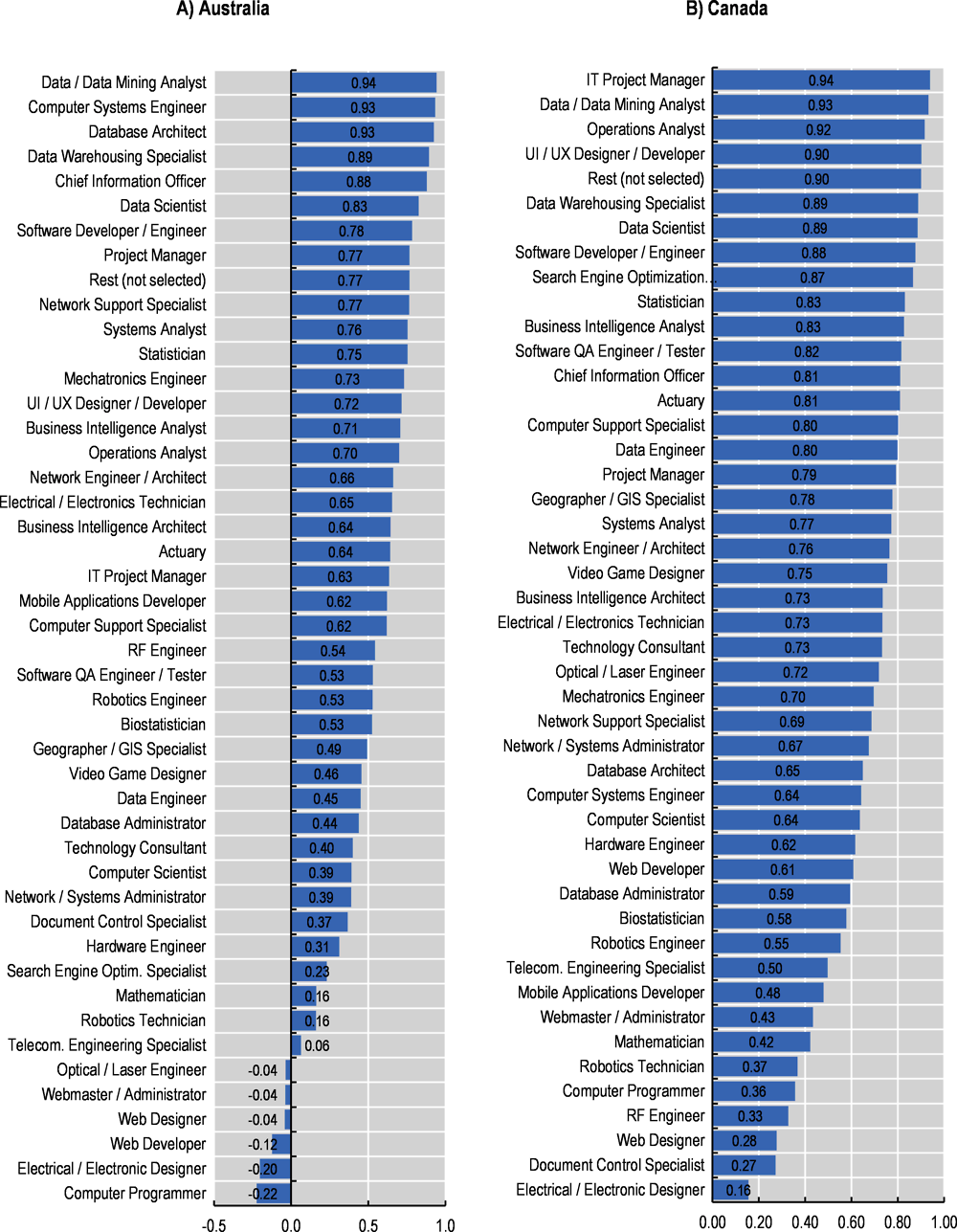

Figure 2.10 presents, for each country, the correlation indices between the growth in the demand for cyber security professionals and the growth in demand for selected professions in the digital, engineering and math related occupations group. Results suggest that the demand for several digital occupations is tightly linked with the demand of cyber security workers (see Figure 2.11 which reports the full ranking of correlations for each country7). Nonetheless, the degree of association between demand for cyber security professionals and demand for other digital professionals can vary across countries. The growth in the demand cyber security professionals, for instance, is strongly linked with that for data/data mining analysts, computer systems engineers/architects and data warehousing specialists (average correlation across countries is 0.92, 0.85 and 0.81 respectively, in the period in January 2012 to June 2022).

Figure 2.10. Correlation between cyber security and selected professions

Correlation indices per country calculated on a monthly standardised index (Jan‑12 = 100).

Note: The professions in this chart have been selected as they typically show the highest correlation indices with the cyber security profession across the countries considered. Wider blue pentagons indicate a tight link between the growth in the demand for cyber security and the growth in the occupation at hand over time and across countries. Data for NZL starts on January 2013.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

The correlation between the demand for cyber security professionals and data analysts, data mining analysts or computer systems engineers/architects does not come as a surprise. Data analysts,8 for instance, are in charge of collecting and analysing data from a variety of sources, rely on computer systems, such as database management or user interface software. As firms increasingly digitise their businesses, relying on a wider number of data analysts, they also face increasing vulnerabilities and potential cyber attacks. Digitisation of services and processes within firms, inevitably lead to increasing pressures to protect sensitive information and cyber security protocols and systems play a key role in protecting confidential information stored in digital systems from existing or potential threats.

Similarly, computer system engineers/architects design and develop integrated computer systems to solve application problems, system administration issues or network concerns (O*NET, 2022[21]). Professionals in this occupation are likely to be frequently interacting with cyber security professionals, such as security architects or penetration testers since these professionals are in charge of assessing networks’ security robustness and implement security policies and technology to protect files and infrastructures.

Results for the United States indicate a strong correlation of cyber security and most of the digital, engineering and math related professions. However, two professions, software developers/engineers and networks engineers/architects, stand out as those with the highest correlation with cyber security in this country. The functions performed by these roles are closely intertwined with that from computer system engineers/architects.

At the other side of the spectrum, Figure 2.11 shows that web designers, webmaster/administrators and electrical/electronic designers are the professionals with the lowest correlation coefficients in the five countries, with an average correlation of ‑0.05, 0.11 and 0.21, respectively. Those occupations are not closely related to the data and systems management and only marginally interacting with cyber security professionals.

Figure 2.11. Correlation: Cyber security and other digital, engineering and math-related professions

Note: Correlation indices calculated on the monthly standardised index Jan‑12=100. Data for NZL starts on January 2013. Larger bars indicate stronger correlations, signalling a tight link between the growth in the demand for cyber security and that for the occupation at hand over time.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Zoom in: What are the job roles in high demand within the cyber security landscape?

The previous section provided a detailed analysis of the evolution of the demand for the occupational category “Cyber / Information Security Engineer / Analyst” (Lightcast code 15 1122.00). Within this category, however, different roles can be identified for workers carrying out a variety of tasks. Cyber security professionals (broadly defined) can be involved in different activities ranging from analysing cyber threats or auditing cyber security infrastructures in firms, to managing the teams in charge of protecting IT systems.9

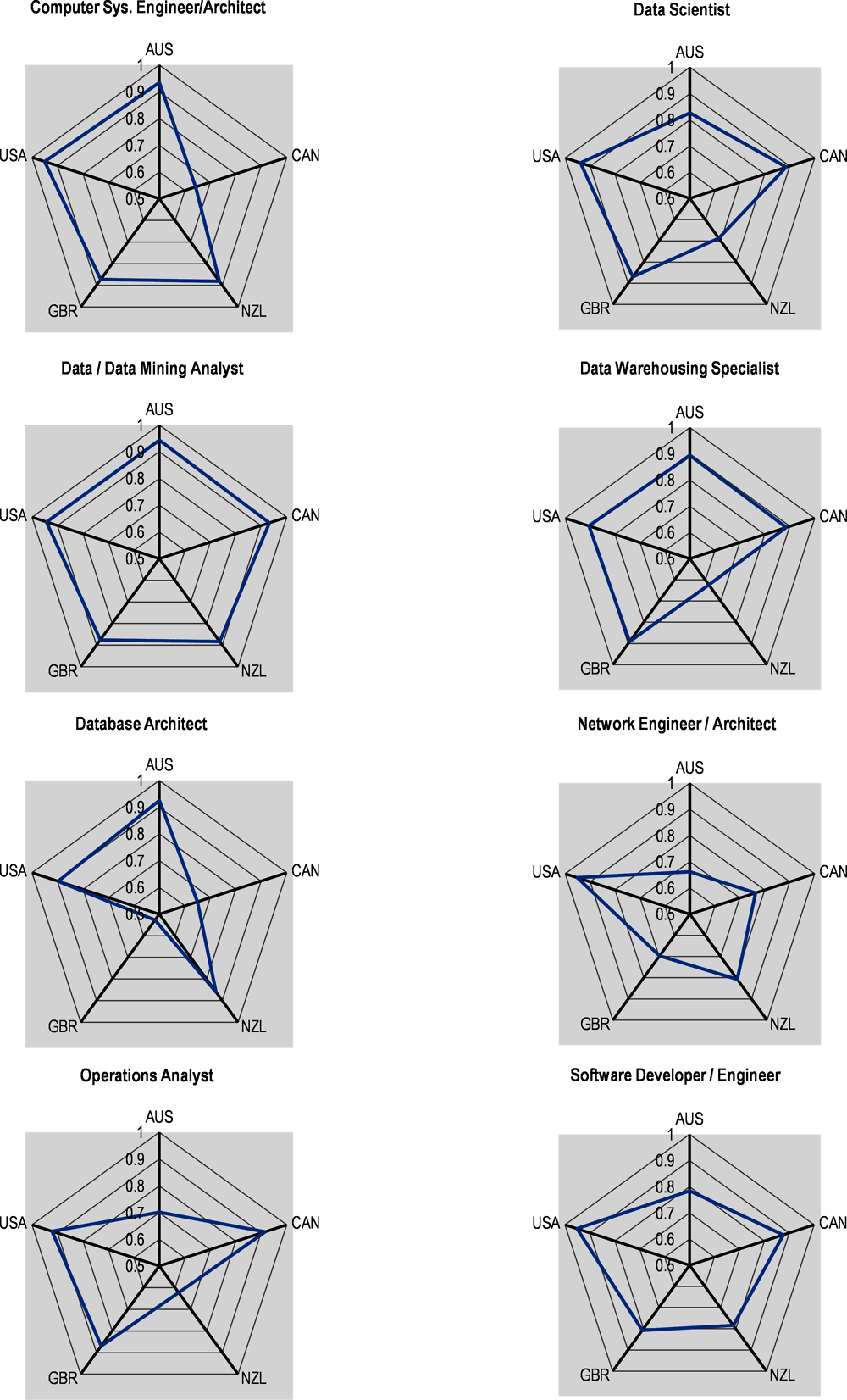

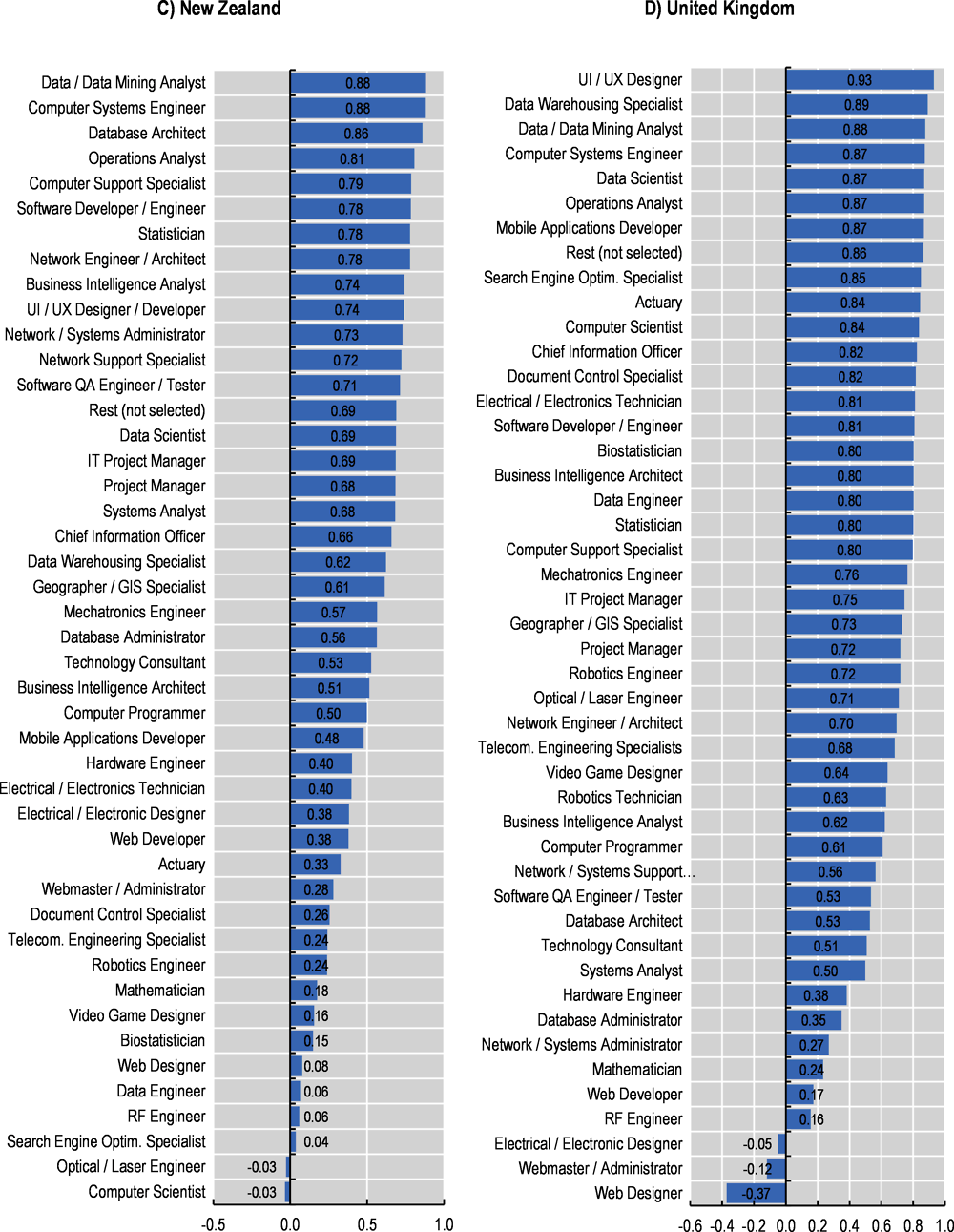

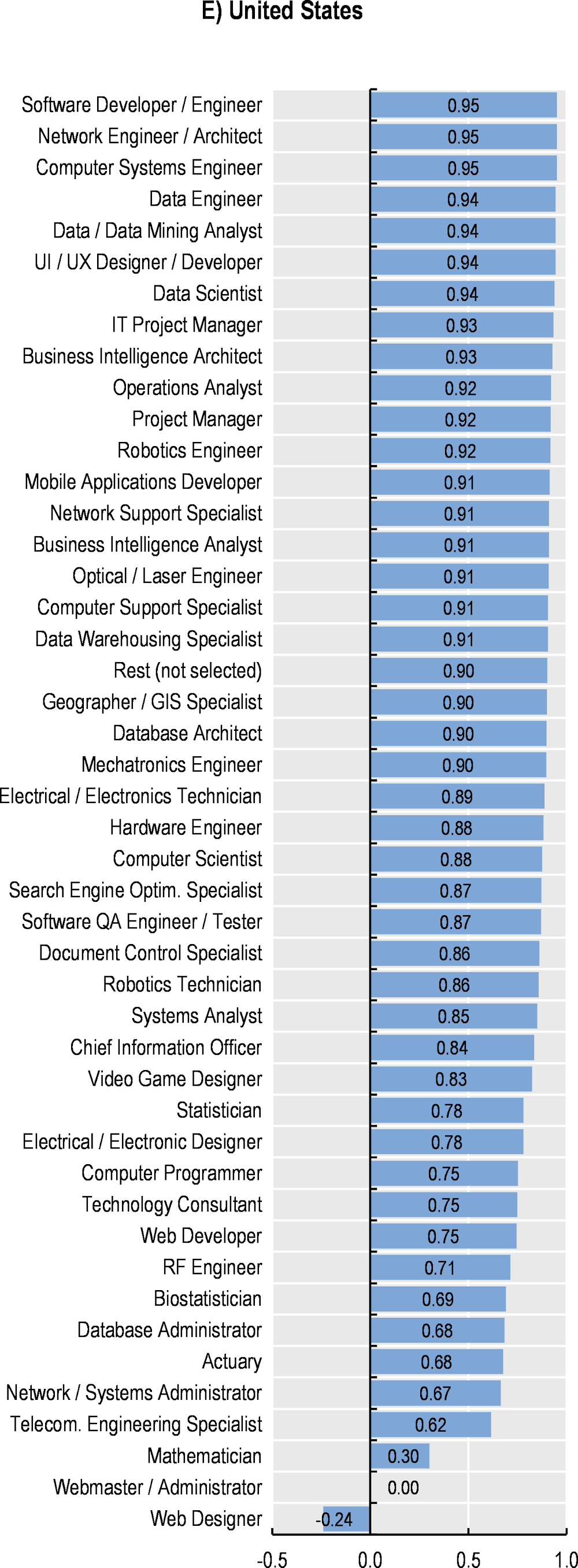

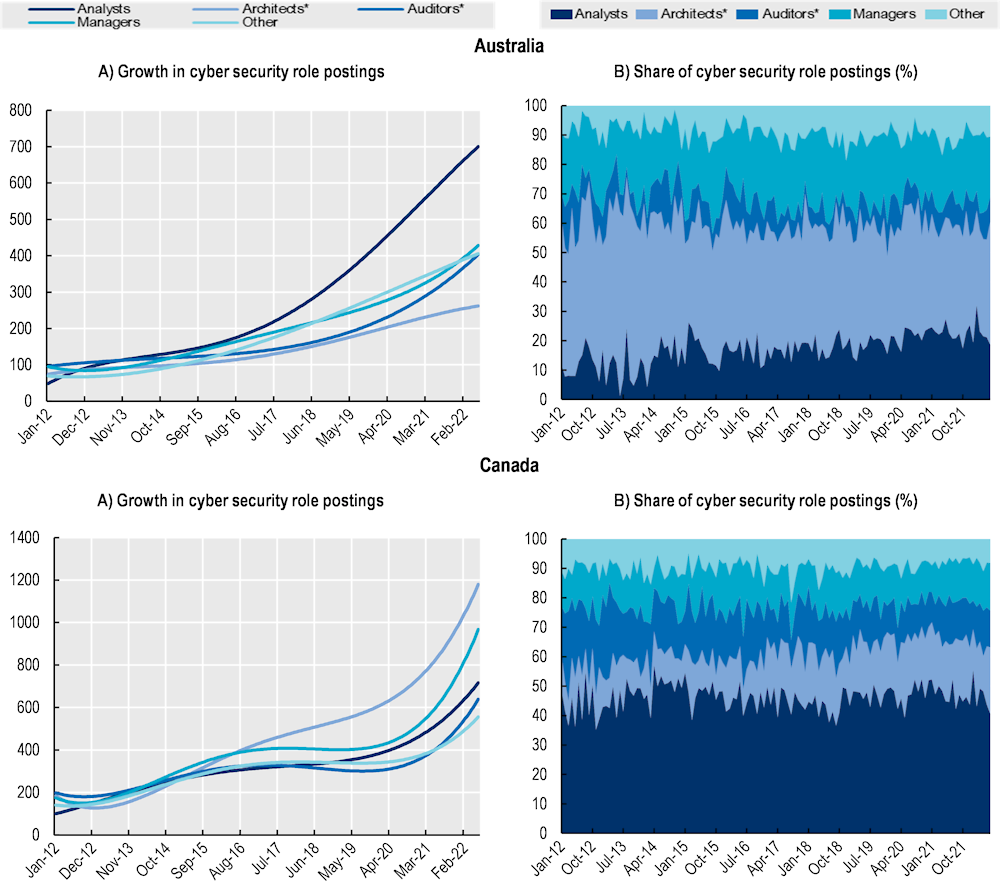

The wealth of information contained in job postings can offer a very detailed overview of the different roles demanded by enterprises in the cyber security space and tracking the evolution of their demand (see Box 2.1 and Annex 2.A). Figure 2.12 presents the trends and shares in the demand of four groups of cyber security roles: analysts, architects and engineers, auditors and advisors, managers.

Detailed analysis of OJPs carried out at the “job-role” disaggregation level shows that architects and engineers are among the roles with the fastest growth in the last decade, driving the growth for cyber security positions in Canada and the United States (see Figure 2.12, Panel A).

Cyber security architects ensure that business security needs are adequately addressed on enterprises’ architecture, which implies the design and modelling of security solutions (NICCS, 2022[22]). Engineers, instead, while working closely with architects, focus more on the processes necessary for the implementation of security solutions and their integration with other IT products (Joint Task Force Transformation Initiative, 2018[23]). Figure 2.12 (Panel B) confirms that cyber security architects and engineers stand at the core of the cyber security demand with, on average, 37% of OJPs looking for this role across the countries analysed in this report. Canada is the only exception to this result, where the demand for Cyber security Architects and Engineers is still relatively more modest compared to that for other cyber security roles.

Cyber security analysts are the second most in-demand cyber security role in many countries, accounting for, on average, 26% of the total job postings for cyber security in the five countries selected. Cyber security analysts are commonly in charge of getting insights from multiple data/information sources, supporting the planning, operations and maintenance of systems security (NICCS, 2022[22]). This group of professionals is particularly important in Canada and the United States where it represents, on average, 40% of the job postings advertised in the last decade in the cyber security space. It is interesting to note that the demand for this group of cyber security workers is growing faster than that of most of the other groups in Australia and New Zealand.

Cyber security managers are the third most important role within the cyber security labour market, with 17% of the total posts in the cyber security landscape of the countries analysed. Cyber security managers include those positions involved in decision-making of the cyber security team structure as cyber security managers are tasked to optimise resource allocation, ensure compliance with internal and public regulations and mitigate risks in the networks (Tulane University, 2022[24]). Although managers, being atypical roles, have usually fewer job postings relative to analysts or technicians, it is interesting to notice that this group is the second most important in Australia and New Zealand, even above Analysts. Besides, data shows that this is one of the top-growing roles in Australia, Canada and the United States. This increasing trend is in line with a recent report on the state of the cyber security profession (ISACA, 2022[25])10 that shows that senior managers and executive or chief information security officers (CISO) are the vacancies with the largest increase between 2018 and 2022.

Finally, cyber security auditors and advisors include professionals devoted to providing external or internal advice about the efficiency and compliance of security solutions. In most of the countries analysed in this report, this group shows a lower share of job postings and the slowest growth relative to other cyber security professionals.

Figure 2.12. Cyber security roles: Trends and shares

Polynomial trends calculated on a standardised index (Jan‑12 = 100) for the monthly count of job postings

Note: For Panel A, the standardised index shows the evolution in the demand for a given profession in comparison the month of reference. Data for NZL uses quarterly instead of monthly information due to few or no observations available for all roles considered. *Architects and engineers, Auditors and advisors.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

The professional profile in cyber security online job postings: What are the characteristics of cyber security demands?

The cyber security sector is facing a significant workforce shortage globally. The (ISC)2 Cyber security Workforce Study (2021[2]) quantifies this gap in nearly 2.7 million professionals around the world. Another recent report indicates that almost two‑thirds of the organisations surveyed have unfilled cyber security vacancies, and for most of them filling those jobs takes on average more than three months (ISACA, 2022[25]). Similarly, a survey interviewing IT decision-makers in more than 30 countries on their perceived cyber security skills gap shows that 60% of the respondents have struggled to fill some positions in the area, mainly in roles related to cloud security and security operations (Fortinet, 2022[26]).

This section explores some of characteristics that define the cyber security professional profile enterprises are looking for in the labour market. The analysis of these requirements in OJPs can shed lights on the mismatches between supply and demand that drive the cyber security workforce gap. Specifically, it reviews the qualifications and the minimum experience required by firms in each country to fill cyber security positions. Using a machine learning approach, it recognises the professional and technical skills that are more relevant for the profession, emphasising on the most recent emerging technologies required by enterprises. Finally, this section provide some insights about how earnings offered in the OJPs for cyber security professionals compare with the earnings for other occupations with similar skills demand.

Qualification and experience requirements in cyber security online job postings

Qualifications and work experience are among some of the key aspects that enterprises use to select qualified candidates in the cyber security job market. It is worth noting that this information is not available for significant share of the OJPs considered in this report (see Annex 2.B), nevertheless, the information available can contribute to characterise the cyber security workers’ profile by retrieving the typical educational degrees and the years of experience demanded by firms across labour markets over thousands of different job postings.

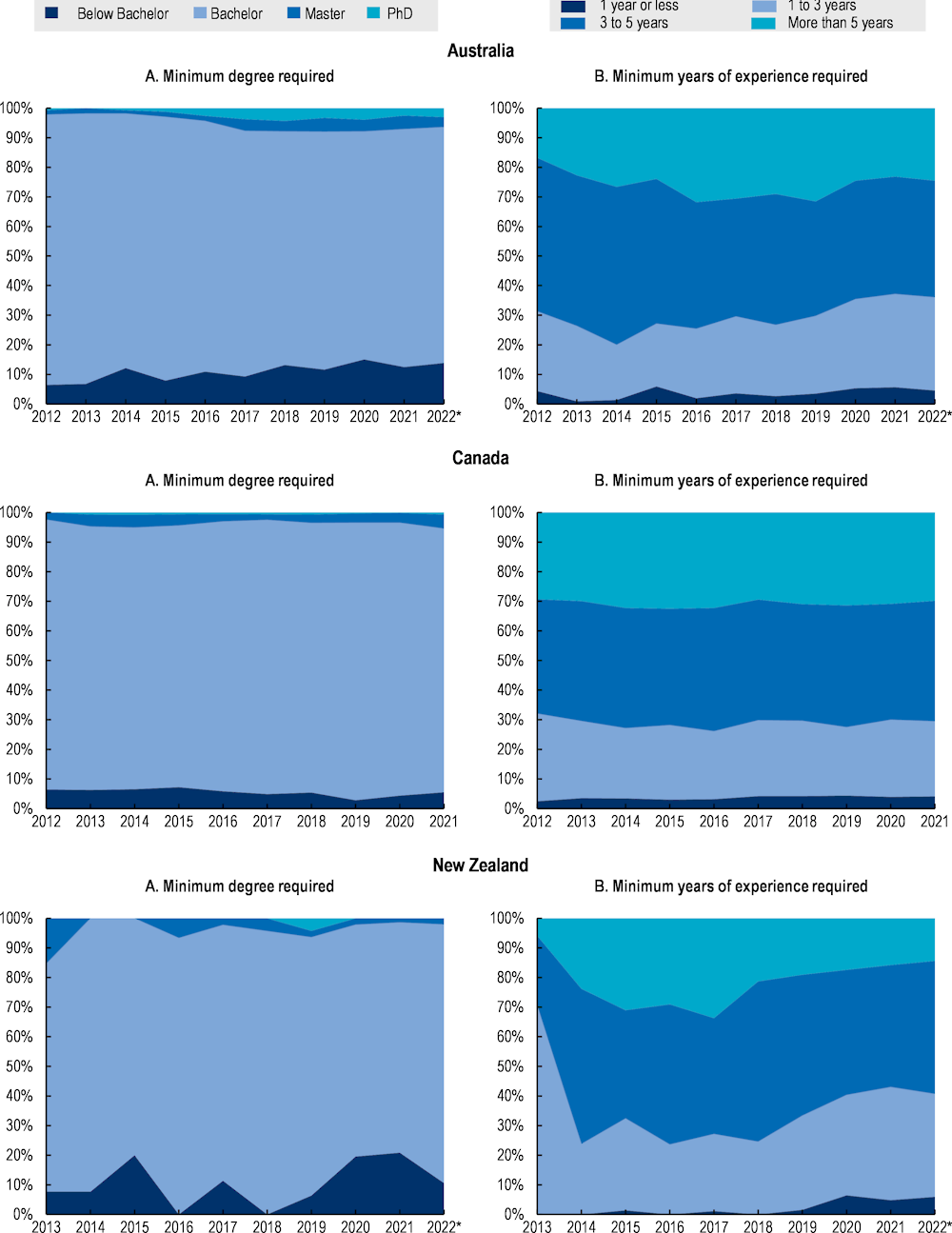

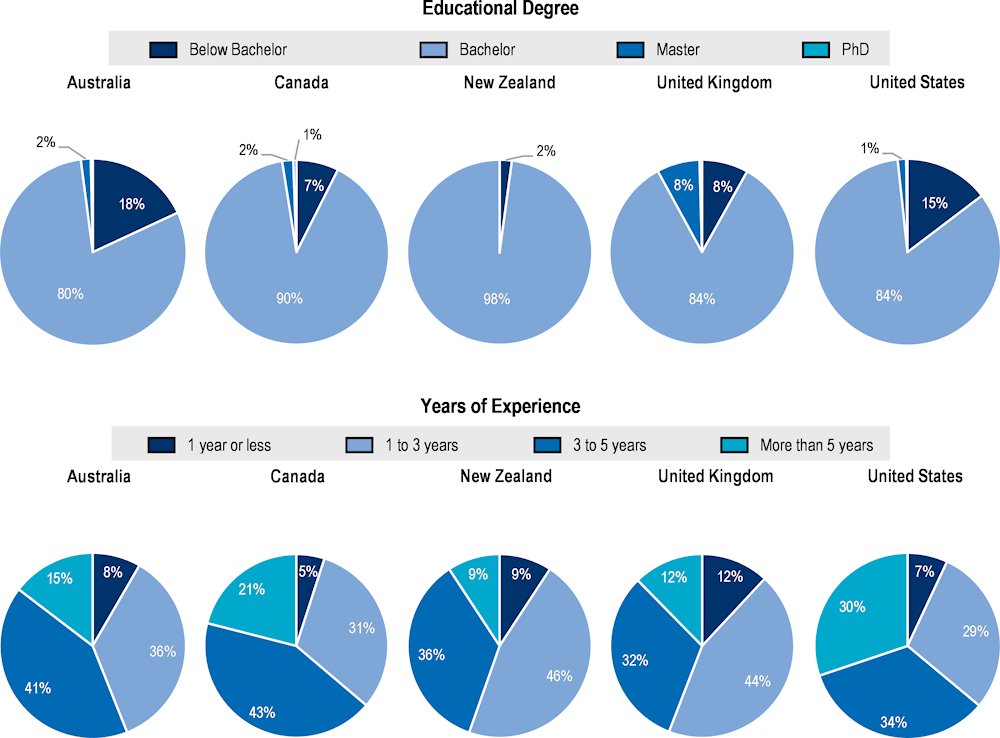

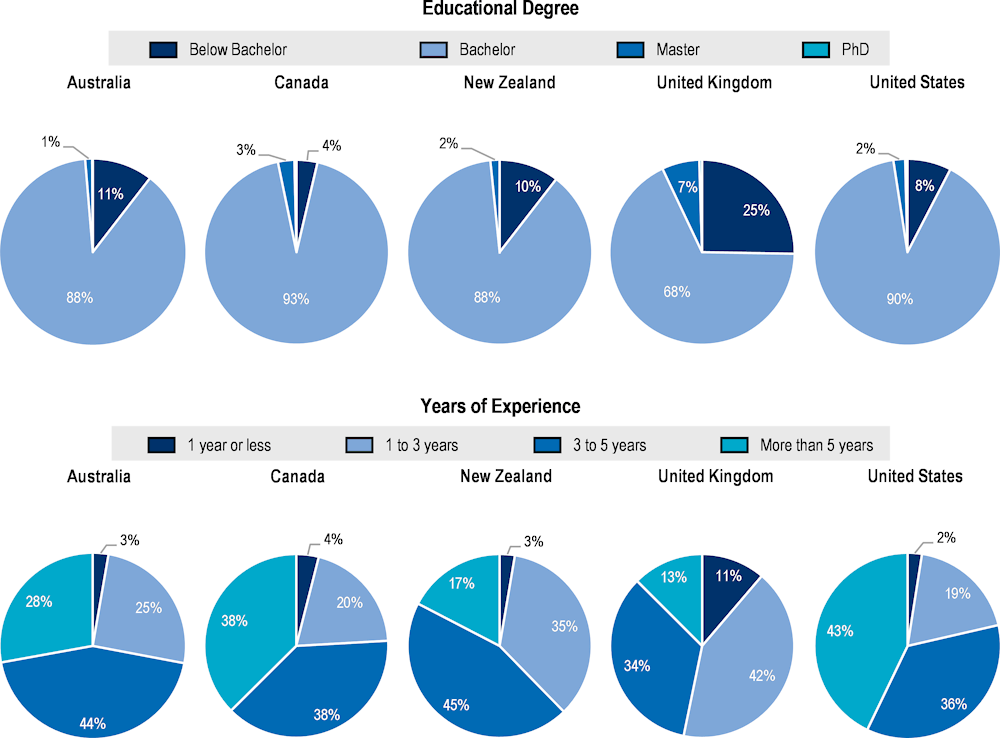

Figure 2.13 shows two panels by country analysing education and experience required in cyber security OJPs:

Panel A exhibits the proportion of job postings requiring, as a minimum, a qualification below bachelor’s level (that require less than 16 years of total education11), bachelor’s, master’s or PhD degrees.12

Panel B shows the proportion of job postings by ranges of minimum years of experience required.

On average, results indicate that enterprises reporting education and experience requirements typically look for cyber security workers with at least a bachelor’s degree (83% of the job postings) and with more than three years of experience (65% of the job postings). In Australia and the United States, for instance, the proportion of job postings requiring at least a bachelor’s degree is nearly 85%, while only 11% require a qualification at a level below a bachelor’s degree.

The education requirements in cyber security follow similar patterns that in other information technology (IT) roles. For the United States, for instance, Indeed (2022[27]) and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2022[28]) show that, in areas such as computer science, computer engineering or IT management a bachelor’s degree is the minimum requirement for an entry-level position in most IT jobs.13

In the case of England, the supply of education and training programmes in cyber security at lower levels of education is still limited, and policies to expand enrolment in this type of programmes have taken off recently. The vast majority of programs focused on cyber security require prior knowledge of ICT or experience in the sector and are often offered at the most advanced levels of education (Level 5‑7, equivalent to ISCED 5 – 8) (see Chapter 3). There have been efforts to expand the supply of non-advanced technical short courses in cyber security (e.g. skills bootcamps) in order to meet specific employer requirements. However, many of these initiatives started recently (2020) and are possibly still unknown (Department for Education, 2021[29]). In the last five years, enrolment in ICT programmes, including cyber security, has grown essentially among the youngest students, especially for Level 3 qualifications (ISCED 3), which is expected to affect trends regarding labour force availability in this field.

Experience, along with education, is another aspect that employers use to select cyber security professionals. Analyses of online job postings in Figure 2.13 indicate that, on average, 65% of the job postings where information on experience is available, seek professionals with more than three years of experience. In contrast, entry-level positions (with one year or less experience) are not widely demanded across labour markets representing, on average, only 5% of the cyber security job postings. This share goes up to 35% when considering job postings requiring a maximum of three years of experience.

This focus on highly educated and experienced workers is in line with the description of cyber security workers in qualitative analyses based on surveys on cyber security and IT professionals. The (ISC)2, for instance, describes a cyber security professional as a well-educated worker (86% of the respondents have a bachelor’s degree or more) with an average of 7 years of experience in a cyber security role14 ((ISC)2, 2021[2]). These results suggest that in the cyber security market there may be a small space for young professionals, with little experience or relatively lower education titles. These results are in line with the analyses by ISACA which indicate that only 44% of their survey respondents manage personnel with less than three years of work experience and highlights the potential challenges that the lack of entry-level positions can exert on an ageing workforce (ISACA, 2022[25]).

Lightcast’s recent research (2022[30]) found that employers not only seek high levels of education and experience, but also that job openings for entry-level cyber security positions requiring a bachelor’s degree exceed the number of bachelor’s degrees conferred in cyber security programs in 2021. Additionally, the number of job openings requiring certifications such as CISSP or CISA is higher than the total number of individuals holding those certifications in the entire country. This mismatch creates barriers for new workers entering the field, contributing to the widening shortage of skilled cyber security professionals.

Notably, the demand in the United Kingdom seems to follow a slightly different pattern than in other countries when it comes to the experience required to access a cyber security job. In the United Kingdom, nearly 10% of the yearly job postings in cyber security with available information request one year or less experience, while half of them require three years or less, a share that is significantly larger than in other countries where experience requirements seem to be more exigent.

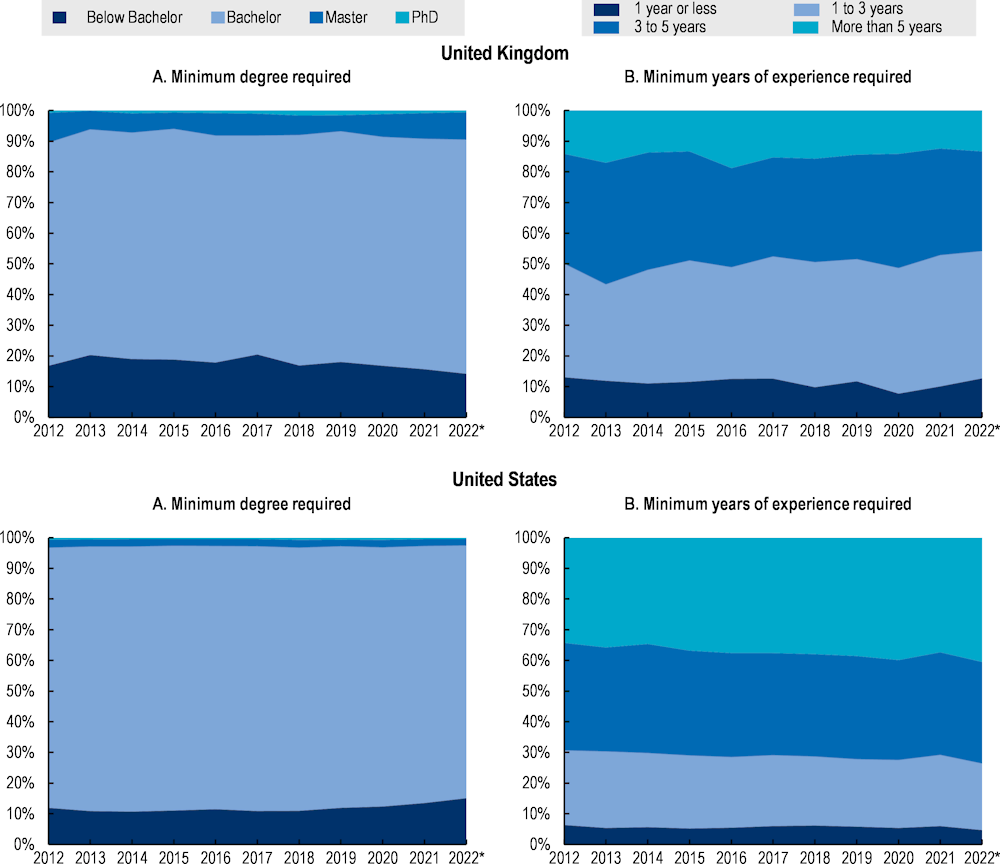

Figure 2.13. Minimum degree of education and years of experience required in cyber security-related online job postings

Note: For AUS, NZL and GBR, approximately 20% of the data specify education or experience. For CAN and USA, non-missing data is 55% and 70%, respectively. Data for NZL starts on January 2013. * Data until June 2022, except for CAN because of consistency issues.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

The fewer opportunities for young workers with little experience to enter the cyber security labour market represent an additional challenge to countries wanting to close the global cyber security workforce gap. Boosting the use of apprenticeships or graduate programmes in cyber security can be a tool to reinforce the linkages between youth and the cyber security professions, ensuring that firms and school absorb untapped talent to work transition is smoother for youth seeking a career in cyber security. Chapter 3 zooms in on this topic.

The education and experience required in cyber security may also vary depending on the specific role workers are involved in. Information contained in OJPs allows looking into these requirements and providing insights about key differences and commonalities in a variety of cyber security roles across the countries analysed. However, given the higher occupational granularity and the low data availability (see Annex 2.B), the following analysis captures the average education and experience level required for the period between Jan‑2012 – Jun‑2022 as a whole to rely on sufficient data points.

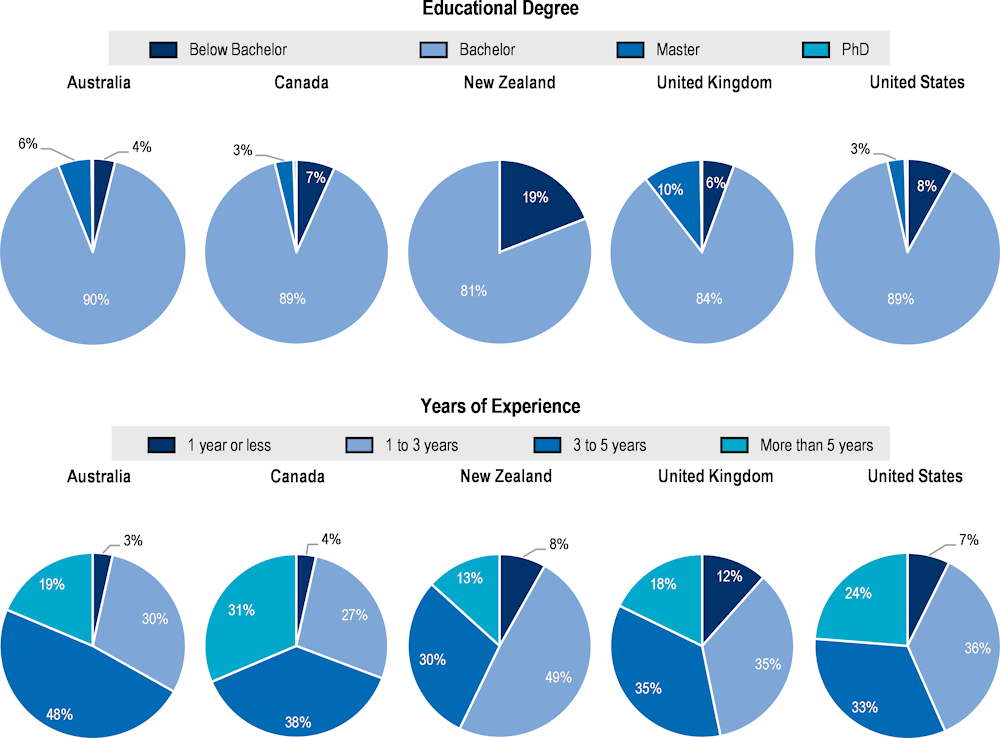

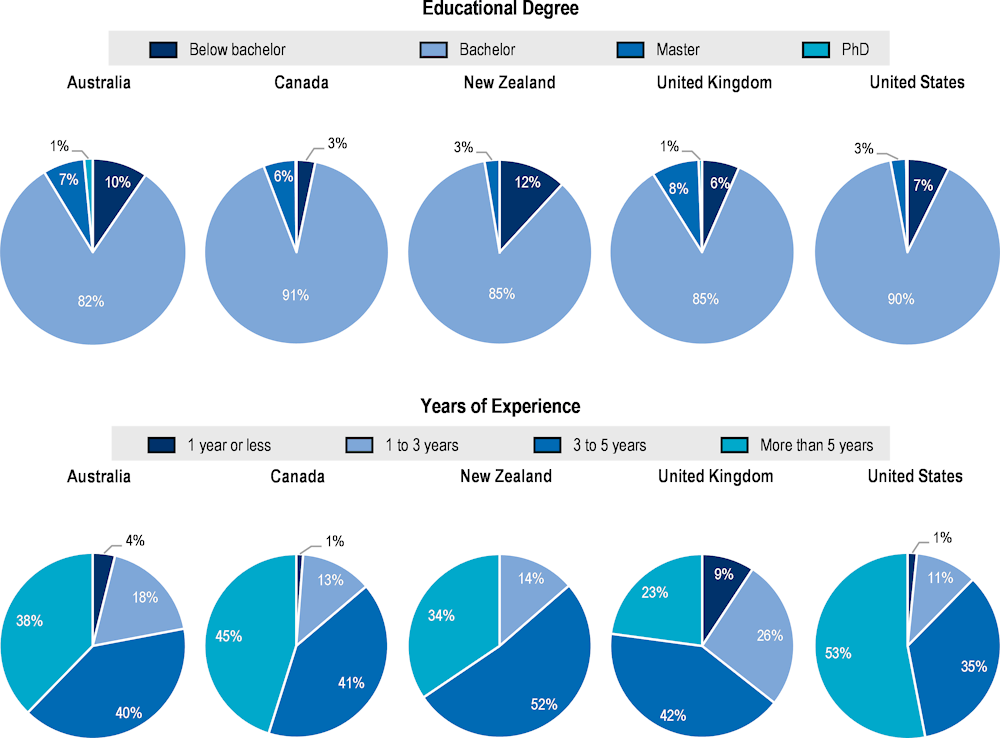

Cyber security analysts

Figure 2.14 shows that a typical applicant for a position as cyber security analyst needs a bachelor’s degree and, with exception of the United Kingdom, a master’s degree or a PhD is hardly required. In contrast, enterprises in countries such as Australia and the United States seek a significant share of workers with qualifications below bachelor’s degree (i.e. vocational or skills-based qualifications) but, at the same time, they demand more than three years as a minimum experience (in more than 50% of the OJPs). This result may suggest some flexibility in recruiters from these countries to find analysts with alternative educational degrees but, in turn, those are required to have significant experience in the sector.

Figure 2.14. Analysts: Share of cyber security OJPs per experience and education required

Note: Below bachelor comprehends those degrees awarded with less than 16 years of education.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Cyber security architects and engineers

Job postings published online for cyber security architects/engineers usually demand candidates to have a bachelor’s degree, while higher education titles such as a master’s degree or a PhD are not typically required (Figure 2.15). The United Kingdom stands out as an exception to this pattern. Enterprises in the United Kingdom that post vacancies online for cyber security architects and engineers usually demand a higher proportion of workers with qualifications below bachelor’s degree for this cyber security role. One of the reasons behind these peculiar results for the United Kingdom may lie in that, in the United Kingdom, there is a relatively broad availability of skill-based certificates in cyber security that require less years than a bachelor’s degree and provide the practical and theoretical knowledge in the area (see for example the HNC/HND in cyber security offered by the Scottish Qualifications Authority (2020[31])). Employers in the United Kingdom may be targeting professionals with that kind of education and experience, more than in other countries.

Regarding the years of experience, job postings for cyber security architects/engineers typically look for candidates with more experience than those for cyber security analysts. In all countries selected but the United Kingdom, more than 60% of the job postings require workers with more than three years of experience. Even, in Canada and the United States, nearly 40% of the job postings require five years or more. The demand for professionals with just one year or less of experience is, hence, almost absent. Again, the United Kingdom represents the only exception, with half of the job postings requiring workers with less than 3 years of experience.

Figure 2.15. Architects/engineers: Share of cyber security OJPs per experience and education required

Note: Below bachelor comprehends those degrees awarded with less than 16 years of education.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Cyber security auditors and advisors

Figure 2.16 shows that the demand for cyber security auditors and advisors commands a relatively larger share of workers with at least a master’s degree when compared with analysts and architects/engineers. Since the tasks of these positions require providing audits or advisory of the enterprises’ security systems, it is reasonable to find a demand for a more specialised workforce. New Zealand stands out as the only case in which a high demand for workers with qualifications below bachelor’s degree remains high. In this case, the demand is mainly for professionals with diplomas, a Level 5 or 6 qualification (among 10 levels) in the New Zealand’s education system that certifies theoretical and technical knowledge in specialised fields (New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2016[32]).

The required years of experience for a cyber security auditor/advisor do not differ significantly from those demanded to cyber security analysts. Most new OJPs for cyber security auditors and advisors look for workers with one to five years of experience while less than 10% look for workers with little or no experience. Notably, in Canada nearly one‑third of the job postings require a person with more than five years of experience, while in the United States almost one out of four postings require such extensive level of experience.

Figure 2.16. Auditors/advisors: Share of cyber security OJPs per experience and education required

Note: Below bachelor comprehends those degrees awarded with less than 16 years of education.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Cyber security managers

Finally, in line with the tasks usually associated to this role, the demand for cyber security managers (i.e. leads, managers, directors, etc.) require both more education and experience (Figure 2.17). The proportion of job postings requiring at least a master’s degree is similar to the case of cyber security auditors/advisors, but in this case, a small share of job postings in Australia and the United Kingdom requires, as a minimum, also a PhD degree. However, In Australia and New Zealand, the demand for cyber security managers with qualifications below bachelor’s degree is larger than in other countries, which suggest a higher emphasis on the experience than on the educational qualifications for some positions. For instance, in Australia, the Certificate IV and the Diploma (Level 4 and 5, respectively, in the Australian Qualifications Framework), are vocational qualifications below a bachelor that are demanded as the minimum required degree in job postings looking for security managers or administrators.

The profile for cyber security managers also requires more experienced applicants. In most of the countries selected, more than 75% of job postings target applicants with more than three years of experience. Even though the United Kingdom follow the same overall trends, the proportion of job postings demanding highly experienced workers is lower (65%). Moreover, a small proportion of job postings in the United Kingdom (9%) require less than one year of experience. This requirement of low experience is present in job adverts for positions as team leads, administrators or managers.

Figure 2.17. Managers: Share of cyber security OJPs per experience and education required

Note: Below bachelor comprehends those degrees awarded with less than 16 years of education.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

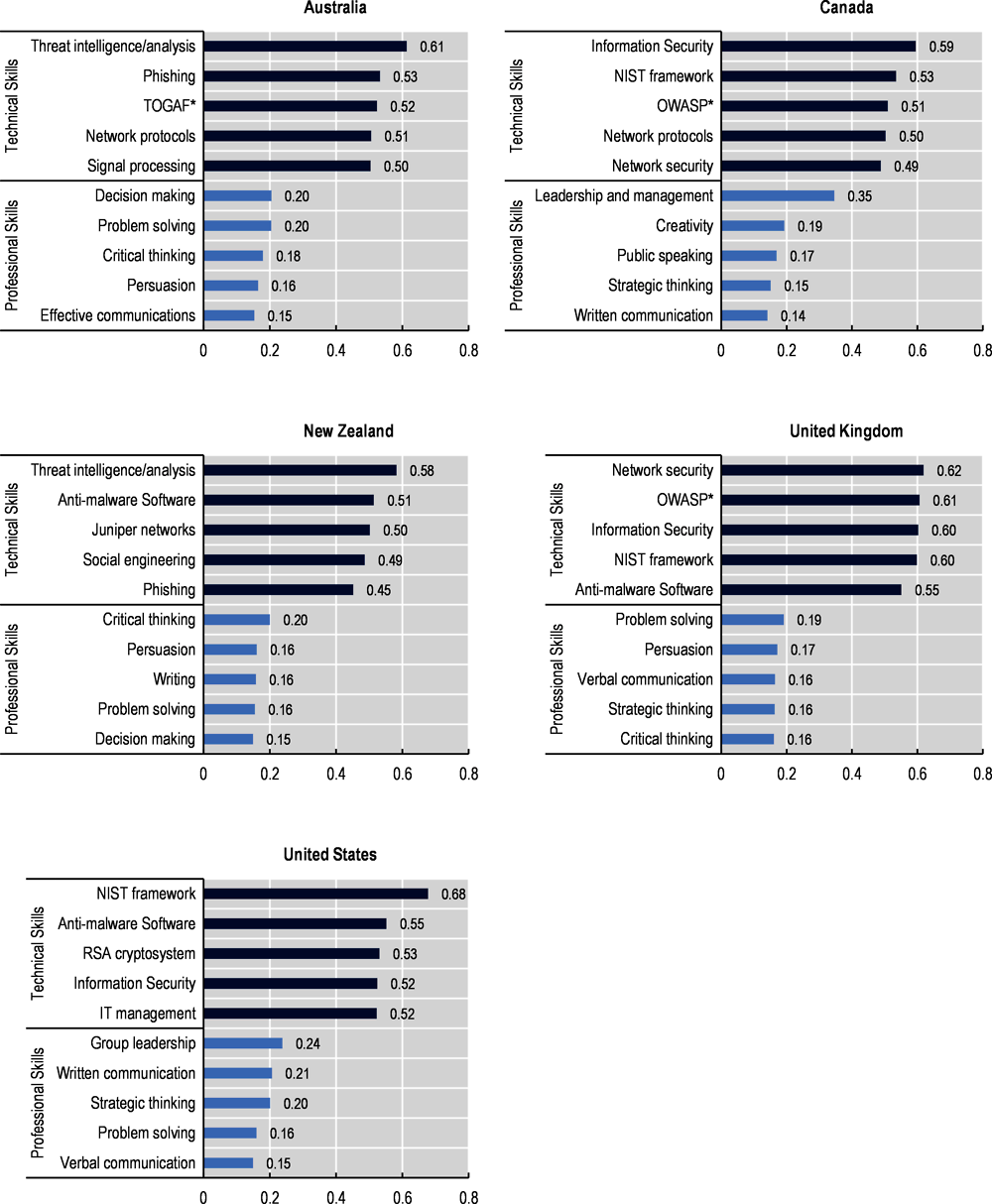

The skills bundle of cyber security professionals

The rapid expansion and adoption of new digital technologies is constantly reshaping the skills that enterprises are demanding when hiring new professionals for cyber security roles. Overall, in the cyber security market, professionals blend technical skills (e.g. programming languages, cloud computing or IT infrastructures) with security-strategy skills (e.g. Governance, Risk and Compliance or threat intelligence/modelling) to create security systems that protect businesses against cyber threats while complying with internal and external regulations.

According to the (ISC)2, the most relevant skills for cyber security professionals include cloud computing security, governance and risk assessment, AI/machine learning and threat intelligence analysis ((ISC)2, 2021[2]). Professional skills, as in other occupations, have reportedly gained importance in the cyber security sector. A report on the state of the cyber security profession indicates that 54% of the managers surveyed report gaps in ‘soft’ skills among cyber-professionals (ISACA, 2022[25]), signalling the importance that the mix of both technical and professional skills plays in creating a dynamic cyber security workforce.

The analysis in Figure 2.18 leverages machine learning approaches (see Box 2.3) to identify the most relevant technical and professional skills in the employer’s demands for cyber security positions collected through OJPs. When focusing on technical skills, the first group of relevant skills encompasses knowledge areas at the profession’s core, such as Information Security and Network Security. These are particularly relevant for cyber security professionals in Canada and the United Kingdom.

Information Security and Network Security, along with “Cyber Security” are terms that can sometimes overlap in day-to-day jargon but that are conceptually different (University of San Diego, 2022[33]). Information Security refers to all those different systems and policies designed to protect the confidentiality and privacy of any kind of information (digital or physical). Cyber security, as a subset of Information Security, aims to protect systems, networks and devices connected to the Internet against cyber threats. Meanwhile, Network Security is a subset of cyber security that comprises different measures to protect network infrastructures and data on them.

Results in Figure 2.18 also indicate the knowledge of specific frameworks that are highly relevant to the cyber security profession. Amongst those, the Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF), the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Framework.

Specifically, TOGAF is a framework used by enterprises as a standard for designing and implementing Enterprise Architecture15 (The Open Group, 2022[34]). TOGAF is used in the implementation of security architectures aiming to align security needs and business goals. OWASP is a foundation based on open-community contributors that works to improve web security by offering guidance, standards and open-source tools and technologies to create applications that can be trusted (OWASP, 2022[35]). Finally, the NIST Cybersecurity Framework has been created by the United States Government and industry to provide standards, guidelines and best practices to manage cyber security risks and foster cyber security management communications among stakeholders (NIST, 2022[36]). Other technical skills appearing in the rankings includes technical knowledge on network protocols, anti-malware software and encryption systems (i.e. RSA cryptosystem), but also threat assessment-oriented skills, such as threat intelligence and knowledge of social engineering practices and phishing.

Cyber security is a profession requiring much technical knowledge with its main domain covering the areas of computing systems and IT networks. Along with technical skills, cyber security professionals also need a variety of professional skills to communicate procedures, strategies and to convey technical messages and concepts in ways that other stakeholders within the firm can understand. However, results in Figure 2.18 shows that similarity indices are in most cases below 0.3, suggesting that professional skills are not as relevant as the technical competencies across demands of employers in cyber security roles.

Figure 2.18. Skill bundle demands of cyber security professionals

Skills with the highest relevance for the cyber security profession in 2021 (closer to 1 = more relevant)

Note: The relevance scores are derived from a semantic analysis of the online job postings for each country in 2021. The closer the score to 1, the more relevant the skill for the cyber security occupation in the country at hand. For more details on the methodology see Box 2.3 and Annex 2.A. * In the Figure OWASP refers to Open Web Application Security Project and TOGAF to The Open Group Architecture Framework.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

When considering only the group of professional skills, OJPs mainly demand problem solving, critical thinking and communication skills. In the five countries considered, verbal communication (or public speaking) and/or written communication (or writing) are amongst the most relevant professional skills for the occupation along with effective communication. Problem-solving and strategic/critical thinking skills are also relevant to the profession in most of the countries. As cyber-threats are evolving constantly, professionals in the area constantly need to develop new techniques and approaches to overcome emerging challenges. Problem-solving and critical thinking are at the core of the implementation of technical solutions to cyber-threats. Interestingly, in the United States and Canada, leadership skills are also relevant for the profession. This result is in line with the increase in the demand for cyber security managerial roles after 2020 in both countries (see Figure 2.12), as well as for a relatively higher interest for more experienced professionals. Figure 2.13 shows that, in either countries, 30% or more of the job postings that specify the minimum years of experience request five or more years of experience.

Box 2.3. Using machine learning to assess the relevance of skills in cyber security occupations

Recent advances in machine learning techniques led to the development of so-called language models which have the objective of understanding the complex relationships between words (their semantics) by deriving and interpreting the context those words appear in. Language models (in particular Natural Language Processing- NLP- models) interpret text information by feeding it to machine learning algorithms that derive the logical rules to interpret the semantic context in which words appear. NLP and language models, used in the remainder of this paper, are therefore better suited for the analysis of text information than traditional statistics and, as such, they are used for the analysis of online job postings in the remainder of this report.

In particular, the approach taken in this report leverages ‘Word2Vec’, an NLP algorithm developed by researchers in Google. This algorithm functions by creating a mapping between the meaning (i.e. the semantics) of words contained in text and mathematical vectors, so-called ‘word vectors’. This representation allows the calculation of mathematical and semantic similarity measures between different skills and occupations (see Annex 2.A for more details on the cosine similarity calculations). Following a recent report from the OECD (2022[5]), skills that are more semantically similar to a certain occupation are interpreted in this report as being more ‘relevant’ to the occupation. Applying this approach is, therefore, possible to assess whether the skill “Excel” is more relevant to the occupation “Economist” or to “Painter”, based on the semantic closeness of these words’ meanings extrapolated from millions of job postings. This is used, in turn, to generate indicators of the relevance of technical and professional skills for cyber security professionals based on the language/semantic analysis of the text contained in the OJPs in each country considered.

Recent OECD work (2022[5]) validated the assumption by which semantic similarity scores derived from word embeddings can be used as a measure of skills relevance for each occupation. In particular, the report compares the results of the similarity scores with expert constructed scores available in the O*NET database. It shows that correlation between similarity scores and the O*NET values is positive, strong (0.62) and statistically significant across all possible combinations of occupations and skills.

New and emerging technology demands in the cyber security world

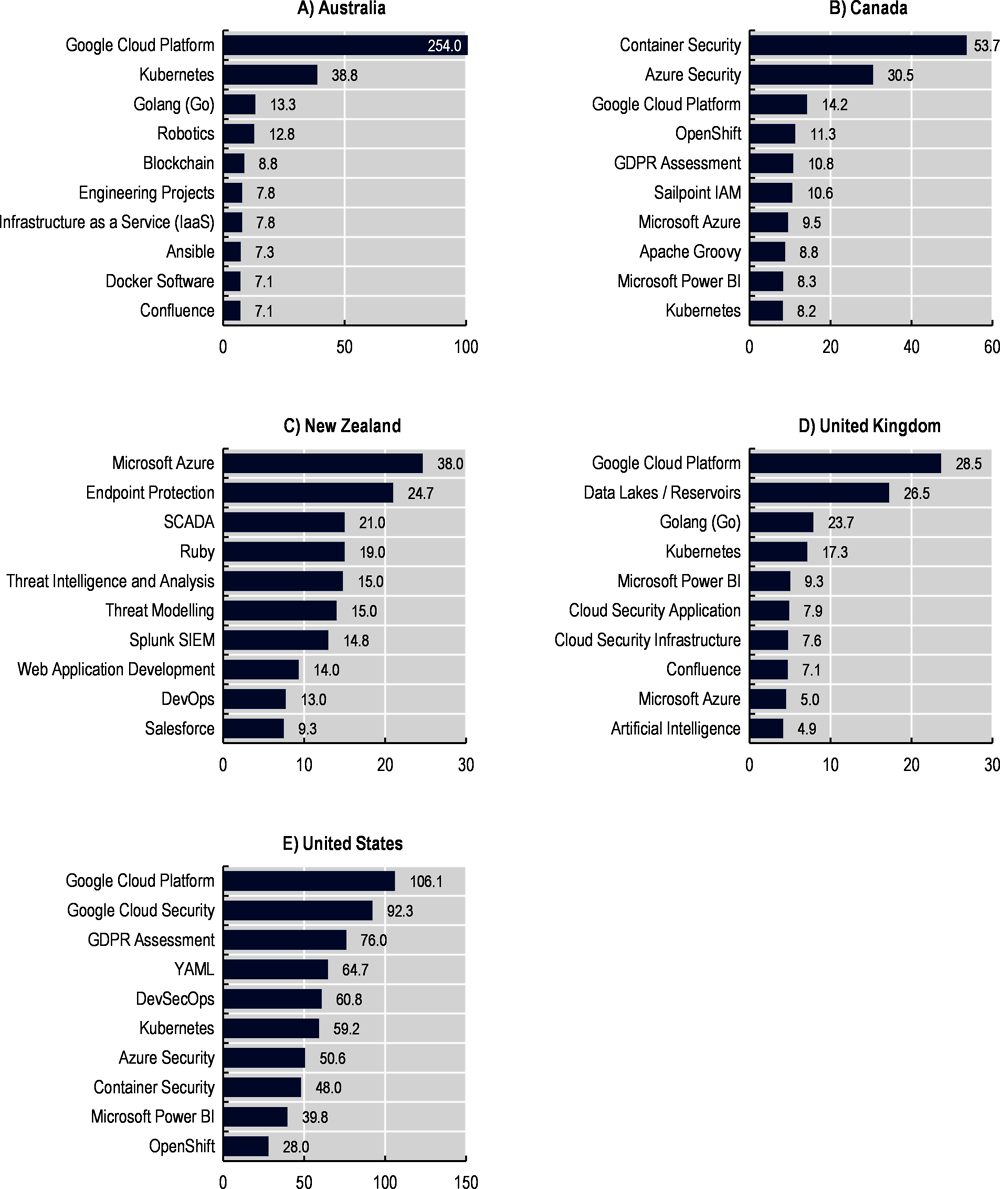

The dynamic nature of the digital world, to which the cyber security profession belongs to, implies that technological demands evolve constantly. New technologies emerge, requiring expertise to operate them. The information in OJPs allows to track the emergence of these new technologies in a timely manner and to identify recent trends. Results in Figure 2.19 present the top‑10 emerging cyber security technologies. New and emerging cyber-related technologies are identified by computing the ratio between the skill mentions in the period 2019‑22 and those in the period 2012‑18 across OJPs for cyber security professionals.16

In line with the findings of the (ISC)2, all countries show new and emerging cyber-related skills in the area of programming languages and cloud computing services. Programming languages such as GO, Ruby and YAML have significantly increased their popularity (number of mentions in OJPs) among the cyber security job postings. Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud Platform are other technologies that have gained relevance in the last years in the cyber-landscape. The ability to operate these platforms is the fastest growing skill in virtually all countries with the exception of Canada, where it is among the top‑3 skills.

Virtualisation solutions, such as Kubernetes or Docker, show an important increase in their demand across different countries. Specifically, container infrastructure and security skills (i.e. Docker, Kubernetes or container security) stand out as some of the newly emerging technologies demanded to cyber security professionals in the countries analysed. These ‘technical solutions’ have increased their popularity in the last years due to their advantages for application development and deployment in terms of reducing system resources and simplifying portability. Nevertheless, since these containers include all the components necessary to run an application (i.e. code, libraries, system tools, etc.) cyber threats can compromise seriously business operations.

In the United States and Canada, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) framework, implemented by the European Union in May 2018, is a framework for which demand has spread out significantly in the cyber-profession. This is not only true in EU countries, but also in those covered in this chapter, as many of the firms operating outside the EU are still subject to comply with the GDPR (GDPR EU, 2022[37]).

Figure 2.19. Growth in cyber security skills demand

Ratio between the skill mentions in the period 2019‑22 compared to the period 2012‑18 in cyber security job postings (code: 15‑1122.00)

Note: This figure considers those skills or technologies with mentions in OJPs that are above the average observed in the 2019‑22 period. Thus, skills/technologies showing a fast growth but a low number of mentions in the most recent period are excluded.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

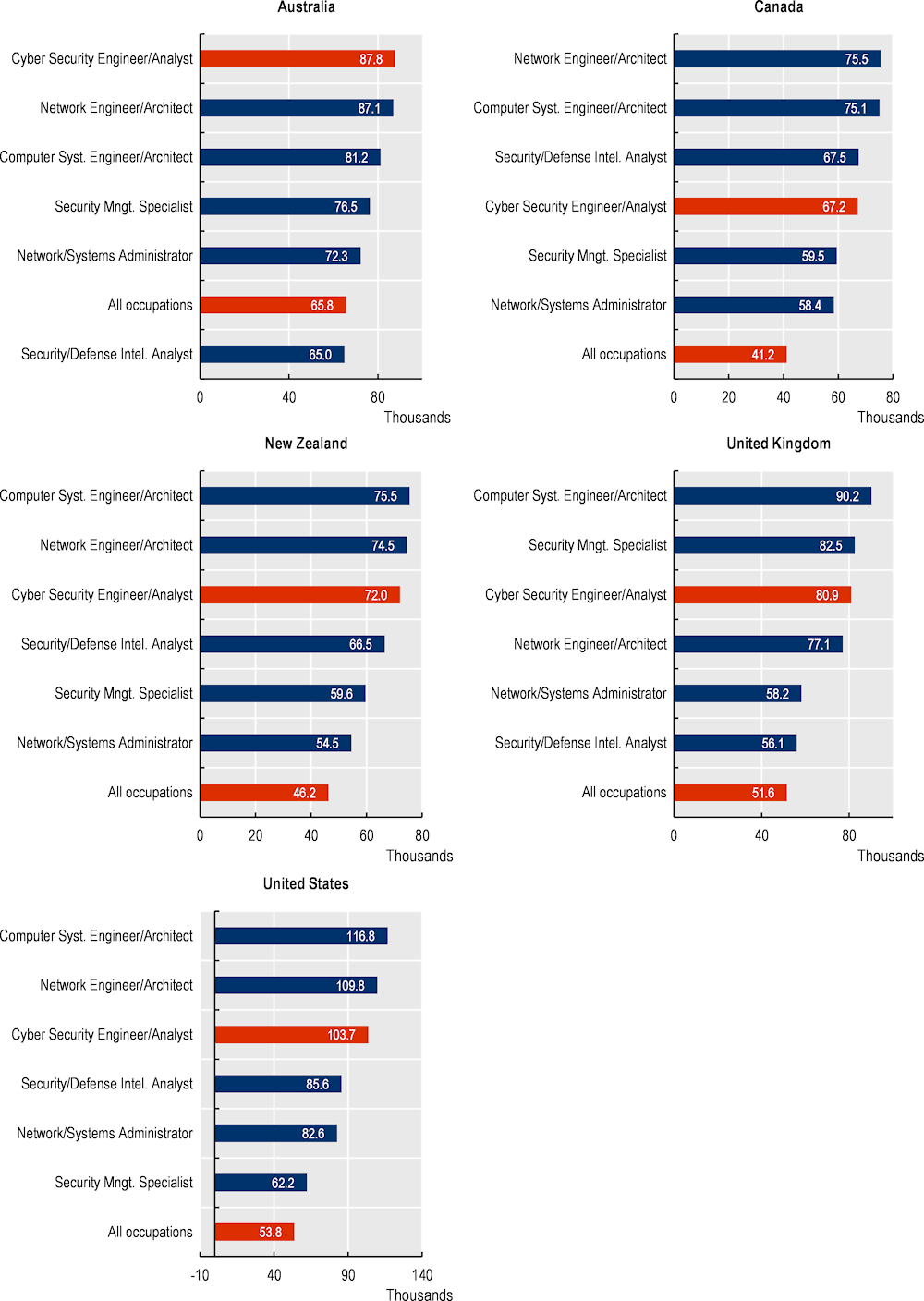

The earnings of cyber security professionals

As pointed out before in this chapter, the global cyber security job market faces an increasing demand for professionals and reported skill shortages. This trend is likely to remain during the next years as the adoption of cyber security technologies is expected to grow strongly. In 2020, the World Economic Forum surveyed enterprises with more than 100 employees about the future of work and, specifically, about the probability of different economic sectors to adopt new technologies by 2025. Among these technologies, encryption and cyber security emerged as one of those with higher probability of adoption with 13 out of 14 economic sectors recording probabilities higher than 70% (World Economic Forum, 2020[38]).

As the demand increases, wages in the sector are expected to remain high, reflecting the shortage of professionals to fill current and, possibly, future vacancies. Notably, in the United Kingdom, nominal wages advertised in cyber security OJPs between in 2021 and 2022 have increased on average 5% while average salaries posted in OJP for the rest of occupations have remained stable, signalling potential shortages in cyber security workforce.