This chapter provides an analysis of millions of online job postings the describe the demand for cyber security professionals in Chile, Colombia and Mexico in 2021 and 2022. The chapter discusses the demand for different cyber security roles, and the geographical location of the demand. To provide a broader context, it also investigates the demand for digital, engineering, and math-related occupations and explores their correlation with the need for cyber security personnel. Moreover, the research highlights specific skills and certifications that are in high demand within the cyber security professions.

Building a Skilled Cyber Security Workforce in Latin America

2. The demand for cyber security professionals in Latin America

Abstract

Introduction: Characterising the demand for cyber security skills

In line with global trends, organisations in Latin America are becoming increasingly dependent on digital technologies for their activities. Along with the benefits derived from a digital and interconnected economy, organisations also face increasing challenges to protect their networks and data, as they are now more susceptible to cyber attacks than ever. Successfully anticipating and dealing with cyber security threats requires a skilled cyber security workforce that is able to identify and analyse potential threats and design cyber security responses adapted to businesses’ needs.

Within this context, there is increasing evidence of a shortage of trained workers in the cyber security sector across the world. In Latin America, (ISC)2 estimates a cyber security workforce gap in Mexico and Brazil of nearly 516 000 people in 2022, with 260 000 of those vacancies being located in Mexico ((ISC)2, 2022[1]). This means that the shortage of cyber security personnel in Mexico is second only to the shortage in the United States ((ISC)2, 2022[1]). Fortinet (2023[2]) indicates that 41% of organisations surveyed in LATAM struggle to fill cloud security roles in 2022. These shortages, as well as reliance on foreign expertise, can potentially contribute to organisations’ cyber security weaknesses.

Developing cyber security capacity in Latin America is, therefore, a cornerstone of cyber-resilient organisations. However, to accomplish this objective, timely and detailed information is required to shed light on the evolving skill demands in the rapidly changing cyber security landscape. Different data sources can provide valuable insights into the skills required in the cyber security sector. For instance, experts have signalled the opportunities of using the information on cyber attacks collected by national Cyber Security Incident Response Teams (CSIRT) to promote research and skills development in relevant areas for each country (Ruiz Tagle-Vial and Álvarez-Valenzuela, 2020[3]). However, progress on how to best use this data has been limited.

An additional rich source of information that is available to analyse the evolution of labour and skill demands in cyber security is that reliant on the collection of online job postings (henceforth, OJPs). This type of data offers many advantages over traditional data sources such as labour force surveys or national accounts data and they can provide a detailed characterisation of the demand in the Latin American cyber security labour markets. On the one hand, OJPs provide timely data on emerging skill demands, as they are collected daily from available jobs posted online in quasi real-time. Furthermore, OJPs provide very granular information on skill demands, allowing for a more detailed analysis of the specific technologies and skills in high demand across the cyber security landscape. Despite the advantages, OJPs have limitations, as they may not provide comprehensive coverage of some occupations and sectors where vacancies are not typically advertised through online platforms (see Cammeraat and Squicciarini (2021[4]) and OECD (2021[5])).

This chapter investigates the demand for cyber security professionals in Chile, Colombia, and Mexico in 2021 and 2022 using data collected by Lightcast1 from nearly 14 million OJPs over a two‑year period. The remainder of this chapter is organised in two sections. The first section overviews the recent demand for cyber security professionals in the three Latin American countries. The second section explores in detail the skills required by employers seeking cyber security workers, according to the texts available in the OJPs. Box 2.1 includes some methodological notes useful for interpreting the results.

Box 2.1. Methodological note: Interpreting the results from online job postings

The wealth of information contained in job postings can offer a very detailed overview of the demand of enterprises for cyber security profiles. This box summarises the main methodological approaches used to leverage these data and improve the readability of the results and insights shown below. Annex 2.A and the footnotes of each figure provide additional details.

Using OJPs to identify the recent evolution of demand

Cyber security OJPs: Data from Lightcast for Latin American countries do not explicitly include a “cyber security occupation title”. Instead, job postings are mapped to occupations using the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO‑08). This occupational taxonomy is, however, too aggregated to identify cyber security professionals specifically. To identify cyber security job postings in 2021 and 2022, this report instead uses a text mining approach applied directly to the underlying detailed job titles extracted from each online job posting. Annex 2.A provides more details on the keywords used to identify a job posting as cyber security-related.

Cyber security roles: Using the job titles available in OJPs, this chapter disaggregates data into roles and tracks the demand for each. Four specific roles were chosen (Analysts, Architects and engineers, Auditors and advisors, and Managers) by extracting the most frequently used keywords from cyber security job advertisements. Annex Table 2.A.2 contains the comprehensive list of keywords associated with each role.

Groups of digital, engineering and math-related occupations: The analysis provides insights on 25 occupations used as benchmarks to compare the trends in their demand with the demand for cyber security professionals. The 25 occupations were classified into 5 occupational groups: 1) Computer and data analysts/administrators; 2) Software developers and programmers; 3) ICT technicians; 4) Math-related professions; and 5) Engineers and technicians.

Using information from OJPs to infer skill demands in the cyber security profession

Skill bundles: Using Natural Language Processing (NLP) methods, the analysis in this chapter identifies the most relevant technical and professional/transversal skills in employer demands cyber security positions collected through OJPs in Chile, Colombia and Mexico (more details can be found in Annex 2.A). Technical skills refer to “specialised skills, knowledge or know-how needed to perform specific duties or tasks” (UNESCO - UNEVOC, 2023[6]), while professional/transversal skills are those “not specifically related to a particular job, task, academic discipline or area of knowledge and that can be used in a wide variety of situations and work settings”.

Skills relevance: As detailed in Annex 2.A, the “skill relevance” index should be interpreted as a measure of the relevance of a given skill for the cyber security profession. The closer the value assigned to a certain skill is to one, the higher the relevance of the skill for the occupation.

It is also important to note that some of the keywords collected do not represent skills strictu sensu. Some of them, for instance, are technologies or tools (i.e. Python or Microsoft Azure), while others identify knowledge areas (i.e. Network or Information Security). For the sake of simplicity, this study pools all keywords together under the term “skills” and only differentiates between them if necessary.

The demand for cyber security professionals in recent years

Most cyber security professionals are in charge of securing data, systems, infrastructure and other cyber resources from failures, hazards and cyber threats that affect an organisation’s mission and operation (World Economic Forum, 2022[7]). This section focuses on tracking the demand for these professionals in Chile, Colombia and Mexico over 2021 and 2022, using online job postings (OJPs). As mentioned, this report uses text mining techniques, by investigating the text contained in job titles, to determine which OJPs are looking for cyber security personnel (more details can be found in Annex 2.A).

How has the demand across countries evolved?

In recent years, Latin America has experienced a notable surge in the demand for cyber security professionals, as evidenced by the rise in online job postings in the countries analysed in this report (see Table 2.1). This trend highlights the growing recognition of the crucial role cyber security plays in the region’s digital landscape, something that is echoed across in other regions as well. For instance, (OECD, 2023[8]) shows that especially after 2020, the demand for cyber security professionals in five anglophone countries increased significantly. As technology advances and cyberspace becomes increasingly intertwined with everyday life, Latin American countries are grappling with the urgent need to address cyber threats.

The data in Table 2.1 reveal a common trend of growing demand for cyber security professionals across all three Latin American countries examined in this report. In particular, the data reveal that the growth for cyber security professionals in between 2021 and 2022 was faster than for all occupations combined in both Chile and Mexico.

Table 2.1. Growth rates of cyber security professionals in LATAM countries

|

Country |

Growth rate for cyber security professionals |

Growth rate for other professions |

|---|---|---|

|

Chile |

28.7% |

2.9% |

|

Colombia |

20.9% |

19.0% |

|

Mexico |

64.6% |

27.3% |

Note: Growth rates have been calculated by comparing the total number of OJPs between January and December 2022 to those between January and December of 2021.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Zooming in at the country level, results in Table 2.1 show that the demand for cyber security professionals in Chile grew by 28.7%, a figure that is substantially higher than the growth rate for other professions, which stands at 2.9%. Behind this tenfold larger increase in the demand for cyber security professionals in Chile there is the increasing emphasis that the country has put in developing its cyber ecosystem in recent years. In 2017, the government instituted the National Cyber Security Policy 2017‑22, which identified concrete goals with the purpose of promoting and ensuring a free, open, safe and resilient cyberspace (UNODC, 2017[9]), see Box 2.2. Furthermore, Chile suffered from a large cyber security attack in 2018, when hackers stole USD 10 million from the Banco de Chile (Kirk, 2018[10]). This again renewed the attention on cyber security. Focus continued into 2020, as the Computer and Security Incident Response Centre (CSIRT-CL) reported over 2.3 billion cyberattack attempts in that year (CSIRT, 2021[11]). Lastly, 2022 was the year that the government issued a modernised cyber security law, which updated the previous regulatory and institutional framework that was established from 1993 (See Box 2.2). (Council of Europe, 2022[12]).

The steep growth in cyber security jobs in Chile is contrasted with relatively low growth in online job postings (OJPs) for all professions. While the Chilean economy experienced a strong recovery in 2021 after the peak of the COVID‑19 crisis as GDP grew by 11.9% (OECD, 2022[13]), GDP growth slowed down in 2022 to 2.4% (Banco Mundial, 2023[14]). Production in Chile decreased during the first quarter of 2022 and has remained lower compared to the previous year. Additionally, the government has withdrawn support measures that were initially implemented to mitigate the economic consequences of the pandemic. Consequently, these factors have resulted in slowed consumption, further impacting the overall demand for professionals across all sectors. (OECD, 2022[13]).

Box 2.2. Chile’s national cyber security policy and legal framework

Cyber security policy

In 2016 the Chilean Government created a national cyber security policy, which would span from 2017 until 2022. The intent of this policy was to help protect people’s security and manage threats in cyberspace, as well as to protect the country’s security and to promote co‑operation and co‑ordination between institutions. The policy objectives that were determined to achieve these goals are” (UNODC, 2017[9]):

1. “The country will have in place a robust and resilient information infrastructure, prepared to face and recover from cybersecurity incidents, under a risk management approach”

2. “The State will protect people’s rights in cyberspace.”

3. “Chile will develop a cybersecurity culture based on education, good practices and accountability in the management of digital technologies.”

4. “The country will carry out co‑operation actions with other stakeholders in the field of cybersecurity and will actively participate in international forums and discussions.”

5. “The country will promote the development of a cybersecurity industry serving its strategic objectives.”

To be able to better achieve the goals in the national cyber security policy, Chile created a Computer and Security Incident Response Centre known as CSIRT-CL in March of 2018. This CSIRT is responsible for providing information and assistance to the government cyberspace; administering a system of co‑operation on cyber security; promoting good practices in cyber security within the government administration; promoting the protection of critical information infrastructures and key resources of the country; promoting the strengthening of the legal framework as it relates to computer and cybercrime; and promoting awareness on cyber security. (Council of Europe, 2022[12])

Legal framework

The Chilean Government instituted a new cyber security law in 2022 to modernise the existing legal framework, which stemmed from 1993, and bring it into accordance with the Budapest Convention (Council of Europe, 2001[15]). The new law criminalises offences such as unlawful access and interception of information and computer systems, attacks on the integrity of computer data or computer systems, abuse of devices, computer forgery and computer fraud. It also exempts criminal liability for ‘ethical hacking’ practices”. (Council of Europe, 2022[12])

Results in Table 2.1 show that in Colombia the growth rate for cyber security professionals was significant and above 20%. However, the growth in demand for these professionals remains aligned with the average growth experienced in the online labour market for non-cyber security occupations.

The high growth rate for cyber security professions in Colombia can be linked to the country’s context of improvements to the cyber security regulatory framework for more than a decade, see Box 2.3. The Colombian Government adopted a national cyber security policy for the first time in 2011, followed by a second policy in 2016 (IADB & OAS, 2020[16]). In 2020 they proposed the new “national trust and digital security policy (2020‑22)” (OAS & CISCO, 2023[17]). Laws that govern cybercrime have been in place since 2009, while laws surrounding data protection and privacy were instituted in 2012 (IADB & OAS, 2020[16]).

The overall high growth of OJPs in Colombia between 2021 and 2022 is accompanied by a GDP growth of 8.1% in 2022 and a strong employment recovery in the first half of 2022 (OECD, 2022[13]). Furthermore, the Colombian central bank reported that the labour market in 2022 was tight, meaning that there was a relatively large number of vacancies compared to the number of unemployed workers (La República, 2023[18]).

Box 2.3. Colombia’s cyber security framework

Cyber security policies

Whereas the first version of Colombia’s cyber security and cyber defence policy from 2011 focused on counteracting the increase in cyber threats in order to protect the country; and to fight against cybercrime, the second version which was instituted in 2016 increased its focus on risk management in the digital environment. This second policy “sets a roadmap with the purpose of identifying, managing, processing, and mitigating digital security risks in the socio-economic environment.” (MinTIC, 2016[19])

The third policy, the national trust and digital security policy instituted in 2020, instead focuses on establishing digital trust in Colombian society, with the following specific goals (MinTIC, 2020[20]):

1. “Strengthen the digital security capabilities of citizens, the public sector and the private sector to increase the digital confidence in the country”.

2. “Update the digital security governance framework to increase its degree of development and improve the progress in digital security in the country.”

3. “Analyse the adoption of digital security models, standards, and frameworks, with an emphasis on new technologies to prepare the country for the challenges of the fourth industrial revolution.”

Legal framework

In 2009, the Colombian Government enacted a few laws on cybercrimes, which protected information, data and ICT systems, as well as defined the concepts necessary for this digital environment. In 2011 the laws were updated with amongst others a regime for the protection of the rights of users of communication services and an obligation for internet providers to use technical and logistical resources to guarantee the security of the network and the integrity of the service, to avoid the interception, interruption and interference. (MinTIC, 2016[19])

In Mexico, the growth of cyber security OJPs was 2.4 times that of the growth rate for all OJPs. The total number of cyber security OJPs went from 3 328 in 2021 to 5 314 in 2022, an increase of nearly 65%, whereas the overall number of OJPS grew by 27% (Table 2.1).

The pronounced increase in cyber security OJPs is driven by the continually increasing need for cyber security professionals, as Mexico is one of the countries in Latin America that is most often targeted in cyber attacks, which can have far-reaching economic consequences. For instance, just like in Chile, Mexican banks were the target of cyber attacks in 2018, and 5 banks experienced losses as high as USD 20 million (Kirk, 2018[21]). Furthermore, Mexico is still one of the top victims of attacks in Latin America, as “85 billion cyberattacks were attempted in Mexico in the first half of 2022, according to the Mexican Cyber security Association (AMECI), an increase of 40% over the same period in 2021.” (INAI, 2022[22]). Moreover, FortiGuard Labs, a cyber intelligence laboratory, reported that Mexico received more than half of the attacks reported in Latin America during 2022 (187 billion), followed by Brazil (103 billion) and Colombia (20 billion) (FortiGuard Labs, 2023[23]).

Mexico is aware of the need for more cyber security, as evidenced by the national cyber security strategy which the government created in 2017 (Government of Mexico, 2017[24]), see Box 2.4. And while the country does not currently have a dedicated law on cybercrime (IADB & OAS, 2020[16]), a new federal law on cyber security has been proposed to the chamber of deputies in April of 2023 (Cámara de Diputados, 2023[25]), see Box 2.4.

Although the growth in the number of cyber security OJPs is much stronger than that for the overall number of OJPs, which is also highly significant at 27%. Mexico’s labour market improved in 2022, as a gradual recovery in tourism and in internal consumption led to slightly higher employment in the summer of 2022, than at the end of 2019, before the COVID‑19 pandemic (OECD, 2022[26]). This helped propel the number of OJPs posted in Mexico.

Box 2.4. Mexico’s national cyber security strategy and legal framework

National cyber security strategy

Mexico’s cyber security strategy from 2017 has the “main objective of identifying and establishing the cyber security actions applicable to social, economic, and political areas, to enable citizens and private and public organisations to use ICTs responsibly for the sustainable development of the Mexican state”. (Government of Mexico, 2017[24]). There is a strong focus on improving people’s ability to operate in a safe digital environment. In order to achieve these goals, the following strategic objectives were formulated (Government of Mexico, 2017[24]):

1. “Create the conditions for the population to carry out activities responsibly, freely, and in a safe manner in cyberspace. Improve the quality of life through digital development [...]”

2. “Strengthen cyber security to protect the economy of different sectors of the country and promote technological development and innovation. Boost the national cybersecurity industry, in order to contribute to economic development [...].”

3. “Protect information and computer systems of public institutions to ensure their optimal functioning and the continuity in the provision of services. “

4. “Improve capacities for the prevention and investigation of criminal behaviour in cyberspace that affect people and their assets, with the aim of maintaining order and public peace.”

5. “Develop capacities to prevent risks and threats in cyberspace that may alter national sovereignty, integrity, independence, and impact development and national interests.”

Legal framework

The provisions in regard to cybercrime in the currently existing laws are limited, leading to difficulties in combatting these crimes (IADB & OAS, 2020[16]). Part of the national cyber security strategy was to aim at adapting the national legal framework. As a result, the newly proposed cyber security law stemming from April 2023 proposes changes to the framework. The law -if adopted- will define cybercrimes and “establish the attributions, powers and responsibilities between authorities”. It also proposes a new national cyber security agency and makes registering with this agency mandatory for any digital platform operating in the country (Paez Jiminez, 2023[27]).

While the demand for cyber security professionals has been on the rise across the countries examined, the total number of OJPs for cyber security jobs remains a relatively small share of the total number of OJPs in each Latin American country analysed in this report. On average in 2021 and 2022, 0.08% of all OJPs in Chile were looking for cyber security professionals, compared to 0.13% in Colombia and 0.11% in Mexico. One reason why the share of cyber security jobs might seem smaller in Chile than in the other two countries analysed, could be attributable to the fact that Chile’s informal sector is relatively smaller (30% of labour is informal in Chile compared to 55%‑60% in Colombia and Mexico) and that many more jobs across other sectors are captured by OJPs in this country. It is worth noticing that most of the cyber security jobs are indeed in the formal sector, and OJPs are likely to be a good representation of the demand for these types of professionals. However, other jobs that are part of the informal sector might not be captured by OJPs. This means that the total share of cyber security vacancies, if informal jobs are taken into account, might be lower for Colombia and Mexico as well.

As Latin America’s digital landscape evolves and the region becomes more integrated into the global digital economy, the demand for cyber security professionals is likely to increase. Countries have stated that cyber resilience is a priority to also be able to benefit from the digital transition.

Zoom in: What are the job roles in high demand within the cyber security landscape?

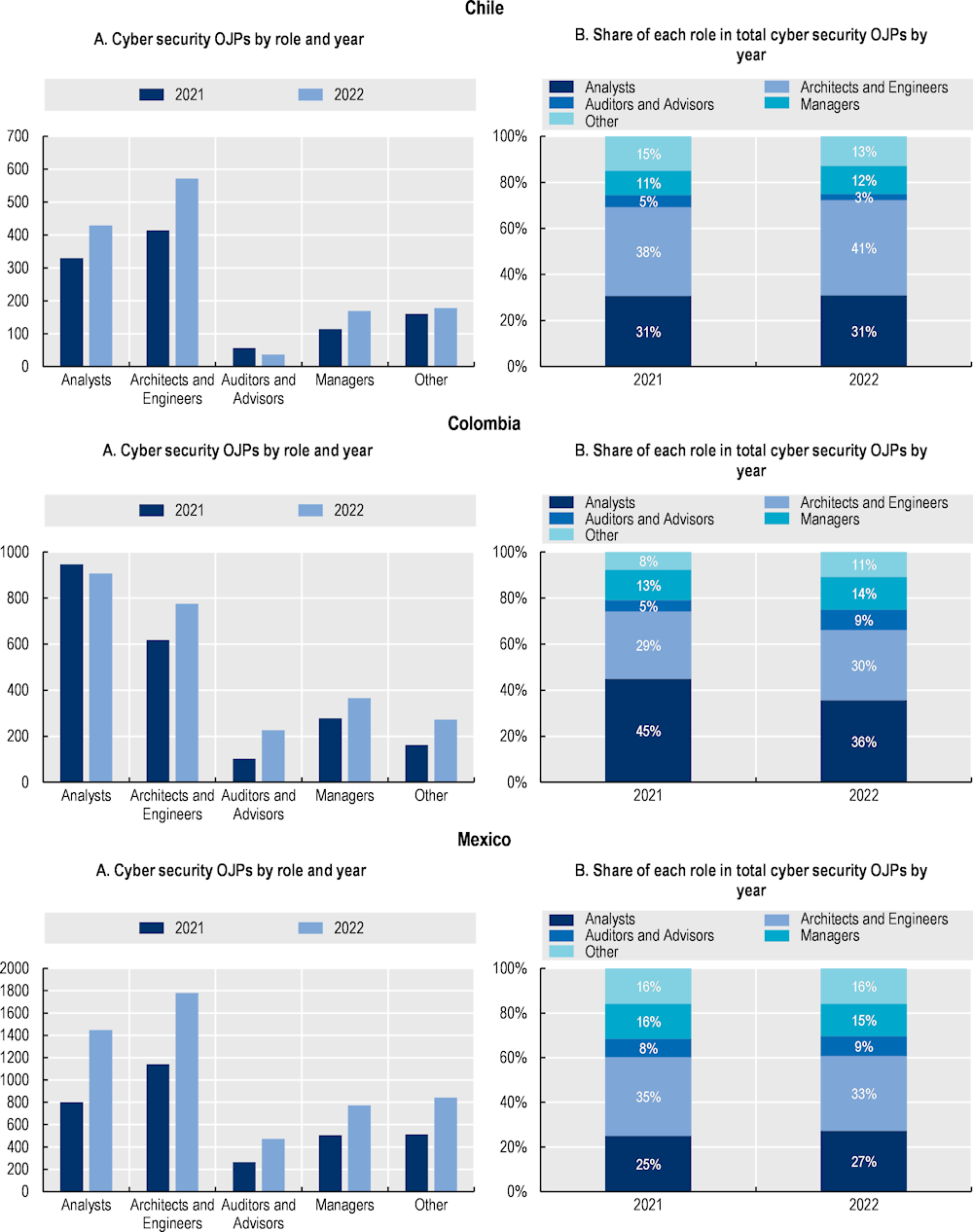

Online job postings can provide a detailed overview of the demand for specific cyber security professionals/roles within the cyber security landscape. This section leverages the job titles used in advertisements to categorise them into different roles, following the approach applied in recent OECD work (OECD, 2023[8]).2 The roles analysed are cyber security analysts, architects and engineers, auditors and advisors, and managers. The distribution of the demand across different cyber security roles in Chile, Colombia and Mexico follows a pattern similar to the one observed in the Anglophone countries analysed in OECD (OECD, 2023[8]) (i.e. Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States), with analysts and architects/engineers representing 60%‑65% of the total OJPs for cyber security professionals.

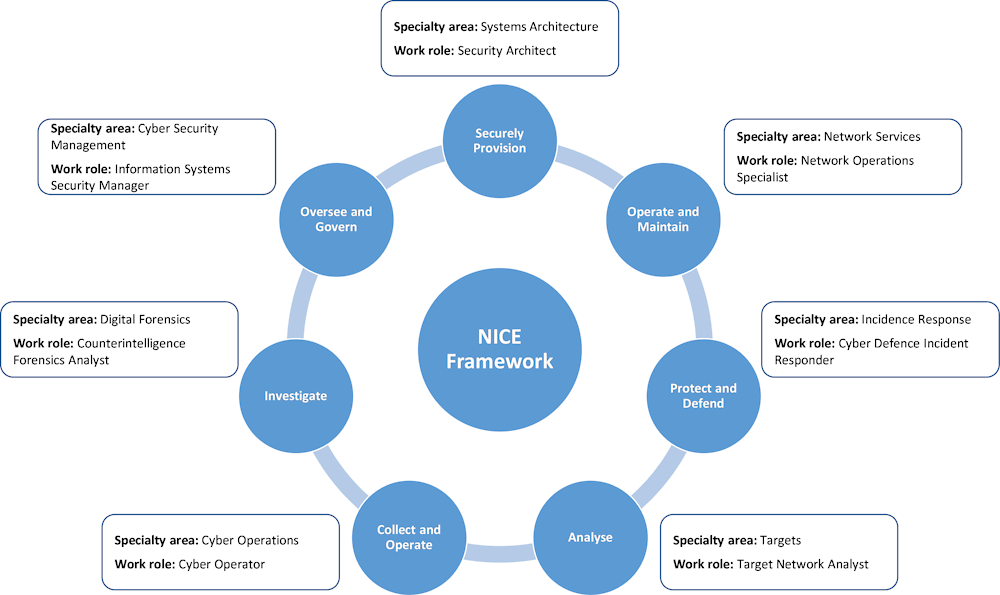

According to the NICE Cybersecurity Framework of the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), cyber security architects are responsible for securely provisioning IT systems. This involves designing and modelling security solutions that address business security needs adequately (NICCS, 2023[28]). Engineers, on the other hand, work closely with architects and focus on the processes required for implementing security solutions and integrating them with other IT products (Joint Task Force Transformation Initiative, 2018[29]). Cyber security architects/engineers develop comprehensive security solutions, design infrastructure configurations, and integrate various security technologies. Their expertise is vital in ensuring that organisations’ digital infrastructure is resilient against cyber attacks and that security measures are integrated into the core design of systems and applications. Cyber security analysts are responsible for performing highly specialised reviews and evaluations of cyber security information to gain insights that support the planning, operations, and maintenance of IT systems security (NICCS, 2023[30]). They are responsible for analysing and interpreting security data, identifying vulnerabilities, and implementing appropriate measures to mitigate digital security risk. The NICE Cybersecurity Framework defines a special category for this role, including specialty areas such as exploitation/vulnerability, language, and threat analysis. With the evolving nature of cyber threats, organisations require skilled analysts who possess a deep understanding of cyber-attack techniques, threat intelligence, and incident response protocols. The high demand for cyber security analysts suggests that firms and governments are actively seeking to enhance their threat detection and response capabilities to safeguard their digital assets and sensitive information.

The demand for cyber security architects/engineers is particularly strong in Chile where they represent 40% of the total number of OJPs advertised during 2021 and 2022. In Mexico, 34% of the cyber security OJPs seek architects/engineers, being also the role with the highest share of cyber-related OJPs, while in Colombia, this role accounts for 30% of cyber security OJPs. The high demand for cyber security architects/engineers across Chile, Colombia, and Mexico underscores the critical need for skilled professionals in the field, reflecting the increasing recognition among organisations of the importance of robust cyber security measures and the rising prevalence of cyber threats.

Mexico is the only country among those analysed in this report that experienced positive growth across all cyber security roles between 2021 and 2022. This result confirms the country’ thriving cyber security labour market. However, the observed positive growth in the number of new cyber security job postings may also reflect the increasing risk that Mexican organisations face in the cyber space. As pointed out in the previous subsection, reports indicate that Mexico is receiving the highest number of cyber attacks in the region.

In Mexico, the role with the strongest growth, measured by the increase in the number of new OJPs, is analysts, for which demand has expanded by 80% between 2021 and 2022. On average, analysts represent 26% of the cyber security OJPs advertised in Mexico. Managers experienced a growth of 53% in the same period, representing an additional 15% of the cyber security OJPs (Figure 2.1, Panel B). According to the NICE Cybersecurity Framework, managers fall into the category of “oversee and govern,” which includes all positions in charge of providing leadership, management, and direction to cyber security teams in an organisation. Specifically, this classification defines cyber security managers as these professionals overseeing the cyber security programme of an information system or network and managing information security implications within different areas of responsibility (NICCS, 2023[30]).

In Chile, managers and architects/engineers stand out as the roles with the strongest growth between 2021 and 2022, 48% and 38% respectively. Analyst, the second most in-demand role, also experienced a significant growth of 30%. In contrast, auditors and advisors decreased nearly 35%, which implied that less than 3% of cyber security OJPs advertised in Chile during 2022 were seeking for this type of professionals. This role includes professionals who provide external or internal advice about the efficiency and compliance of security solutions.

In Colombia, the analysis of the demand for cyber security roles shows different results. While analysts, the most in-demand role, experienced a decrease of 4% between 2021 and 2022, architects/engineers and managers presented positive growth of 26% and 32%, respectively. Despite being the least demanded role, the demand for cyber security auditors and advisors increased by 120%. A closer look at the job titles used in cyber security OJPs in Colombia shows that the most in-demand positions for this role are information security consultants and cyber security auditors.

The significant increase in demand for cyber security auditors and advisors in Colombia indicates a growing recognition among organisations of the importance of assessing the efficiency and compliance of their security solutions.3 This trend reflects an evolving understanding of the critical role that auditing and advisory services play in ensuring the effectiveness of cyber security measures. In particular, organisations increasingly realise that cyber security is not solely about implementing preventive measures but also about regularly evaluating and verifying the efficacy of those measures. Cyber security auditors and advisors provide valuable expertise in assessing the overall security posture of an organisation, identifying vulnerabilities, and recommending improvements. In that, they play a crucial role in ensuring that security solutions are not only implemented but also continuously evaluated and optimised to align with changing threat landscapes and industry best practices.

Figure 2.1. Cyber security roles: Recent evolution and shares

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Where is the demand for cyber security professionals located?

Chile, Colombia and Mexico all have stark economic and demographic divides between urban and rural areas. All three countries have highly geographically concentrated populations, ranking 4th, 5th and 6th of all OECD countries in terms of the geographic concentration index of the population in 2019.4 This goes hand in hand with high rates of urbanisation, especially in Colombia, where 57% of the population lives in a metropolitan region compared to an OECD average of 41.4%. The shares of the populations living in a metropolitan region are, instead, much lower for Chile and Mexico, at 30 and 34.7%, respectively, although certain cities in Mexico, like Mexico City, have millions of inhabitants. So, while Chile and Mexico are highly demographically concentrated, most of their urban areas are smaller than those in Colombia. (OECD, 2022[31])

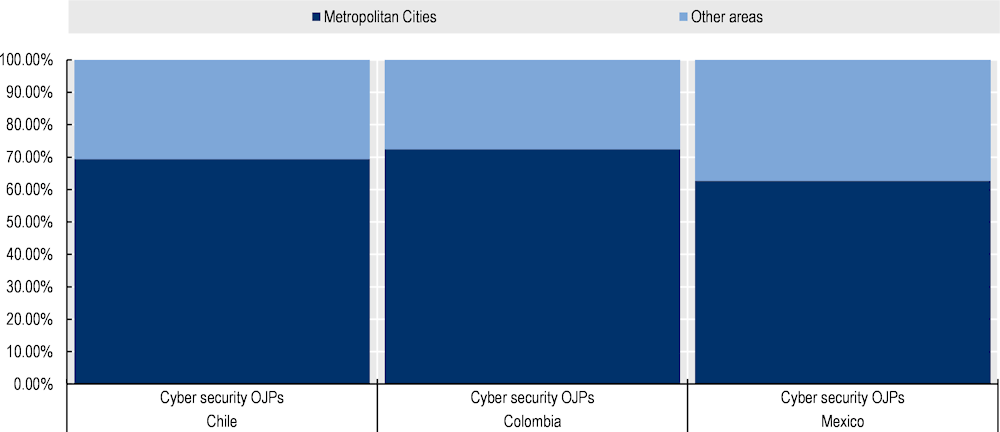

It is, therefore, interesting to examine where the job opportunities for cyber security professionals are located by comparing the share of cyber security OJPs in metropolitan cities5 to the shares in other areas. The distribution for all OJPs is instead described in Box 2.5. For the analysis, metropolitan cities are classified as cities with 250 000 inhabitants or more. According to the latest censuses, there are 71 metropolitan cities in Mexico, 28 in Colombia and 11 in Chile (INEGI, 2020[32]; DANE, 2018[33]; INE, 2017[34]).

In all three countries, the share of cyber security OJPs posted in metropolitan cities is substantial (Figure 2.2). More than 60% of cyber security OJPs6 are concentrated in these larger urban areas. For instance, in Mexico, 62.7% of cyber security OJPs target personnel in metropolitan cities, which exceeds the proportion of the Mexican population residing in metropolitan areas (34.7%) (OECD, 2022[31]).

Figure 2.2. Share of (cyber security) OJPs that are posted in metropolitan cities

Note: The share of cyber security OJPs without information on the city is 77% in Chile, 23.2% in Colombia and 38.5% in Mexico.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Box 2.5. OJPs in metropolitan cities

Figure 2.2 shows the distribution of cyber security OJPs that are posted in metropolitan cities. The purpose is to analyse the geographic concentration of cyber job postings. The figure does not show the same distribution for non-cyber security OJPs, as there may be issues with the representativeness of the data for all labour demand.

As explained in Box 1.3 informality is unlikely to introduce a bias on the number of cyber job postings that are observed. Furthermore, cyber security roles are more likely to be advertised online than other low-skill and medium-skill positions, as these roles are often high-skill positions. The sample for cyber security is therefore most likely representative for the actual labour demand.

However, the same reasoning does not apply to OJPs for other occupations. The shares of all OJPs that are posted in metropolitan cities are: 40.1% in Chile, 72.7% in Colombia, and 58.9% in Mexico. In this case, the large informal sectors and the underrepresentation of low- and medium-skill jobs can result in a lower number of OJPS in rural areas compared to the actual labour demand in these regions. Crucially, these problems are likely to be more pronounced in rural areas than in urban areas (European Parliament, 2021[35]) which means that the shares on the geographic distribution of OJPs for all occupations are not as informative as for the cyber security roles.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

One reason why more cyber-related job opportunities are found in metropolitan cities could be that certain industries, such as finance, technology, and professional services, tend to have a higher presence in metropolitan areas due to the availability of skilled labour, infrastructure, and market demand. Cities, for instance, have higher levels of tertiary attainment and more institutes for higher education (OECD, 2022[36]). Labour markets also provide strong incentives for tertiary-educated workers to move to urban areas, as wages are often higher there (OECD, 2022[36]). The previously mentioned industries benefit from highly educated personnel, making cities attractive spaces to locate. Advanced types of industries are also more likely to hire cyber security professionals. At the same time, however, high-skilled jobs are more likely to be posted online (Cammeraat and Squicciarini, 2021[4]), which can lead to overrepresentation of the share of OJPs that are posted in metropolitan cities, while informality can lead to underrepresentation of low-skilled jobs in non-urban areas.

The results for Chile demonstrate the largest disparity between the share of people residing in metropolitan cities and the share of cyber security OJPs. Just 30% of the Chilean population lives in a metropolitan area (OECD, 2022[31]), while nearly 70% of cyber security OJPs can be found there. However, previous research also showed that “the majority of the OJPs in the cyber security job market are for jobs located in main urban areas where major enterprises and government headquarters are found” (OECD, 2023[8]). The same holds for Chile, where the majority of job opportunities in cyber security are posted in Santiago, for example within companies such as (IT) consultancy firms, accounting firms, and research companies.

In Mexico, a noteworthy cyber-related industry is that of production of (consumer) electronics. As of 2022, there are 487 different manufacturers of electronics in Mexico, mostly in the states Baja California and in Jalisco, which are home to 7 different metropolitan cities: Tijuana, Mexicali, Ensenada, Guadalajara, Zapopan, Tlaquepaque, and Tonalá (Government of Mexico, 2022[37]). The country is known for its role in global supply chains, particularly within the electronics sector, thanks to its strategic location, abundant labour supply, and numerous trade agreements. The electronics manufacturing industry in Mexico includes production of telecommunication equipment, electronic appliances, computers and computer peripherals, and other consumer electronics, and the production of electronics in Mexico has experienced a rapid growth following the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020. Exports of electrical machinery and equipment from Mexico reached USD 87 billion in 2021, positioning the country as the world’s 9th largest exporter in this field (United Nations Statistics Division, 2023[38]). 28%7 of Mexican cyber security OJPs in 2021 and 2022 are posted in the manufacturing industry, and most of these advertisements are within the electronics industry, within the earlier mentioned metropolitan cities.

In Colombia, although a larger percentage of the population (57%) resides in metropolitan areas compared to Mexico and Chile (OECD, 2022[31]), an even larger share of cyber security OJPs are posted in metropolitan cities (around 73%). Opportunities for cyber security professionals are found across a wide variety of industries in cities, signalling how the awareness of the need for cyber security has permeated companies in all different branches. Some notable industries for cyber security professionals in Colombia are the information industry, as well as professional, scientific, and technical services, with most of the OJPs being located in Bogotá and Medellín. Companies that operate within the information sector are often large telecom providers, as well as technology firms. These types of companies can face significant cyber threats and will need to make sure they have secure networks and are in charge of safekeeping a lot of data (like cloud storage). Companies that work on research and development and are part of the professional, scientific, and technical services benefit from having a highly educated workforce, which is why they are often located in the metropolitan cities, close to institutes for tertiary education. Companies that work on development also have large incentives to safeguard their data, leading to an increased need for cyber security.

What is the demand for digital, engineering and math-related occupations?

Global trends such the digital transition and the creation of new technologies do not only propel the demand for cyber security professionals, but also affect the demand of related (digital) occupations. Employers increasingly adopt cloud computing, artificial intelligence and make more use of data. While these developments lead to opportunities for economic growth on the one hand, on the other hand they also lead to more potential cyber security threats, which necessitates a skilled cyber security workforce (IADB & OAS, 2020[16]).

Demand for digital, engineering and math-related occupations has been growing for a long time, while the need for cyber security is also becoming increasingly more pressing as digital technologies are adopted in LATAM. For instance, in Colombia technology and digitisation have already led to innovation in commercial, productive, and scientific research, with Colombia’s tech sector growing significantly over the last few years. The aspirations are that this will turn the country into “the Silicon Valley of Latin America”. Software and IT services’ exports amounted to USD 218.8 million in 2021, a 33% increase from 2020, which shows that this focus on science, innovation and technology is leading to concrete benefits for the Colombian economy (Moncayo and Guzmán, 2022[39]). However, technological systems are often still vulnerable to cyber security threats, espionage and breaches of information (Moncayo and Guzmán, 2022[39]).

This section aims to explore the relationship between the demand for cyber security professionals and other digital, engineering and math-related occupations, contributing to a nuanced understanding of the evolving digital landscape and how data usage and digitalisation has permeated the labour market. By examining the demand for cyber security professionals alongside other related roles, this analysis seeks to discern patterns, identify potential skill gaps, and derive comprehensive insights into the broader dynamics shaping the contemporary job market.8

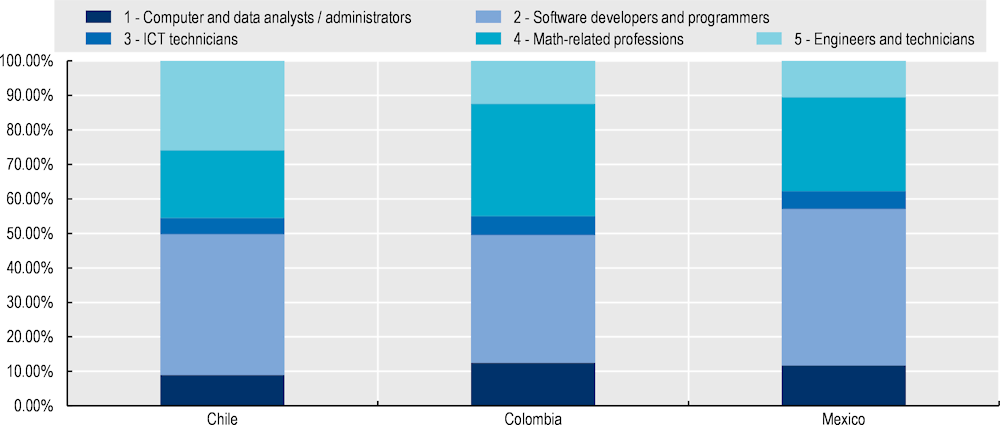

This section analyses 25 occupations that are classified into five occupational groups to assess the relationship between their demand (approximated by the growth in OJPs) and that for cyber security professionals. The choice of these occupational groups is based on the methodology used in two recent OECD reports (OECD, 2022[40]; 2023[8]) but it has been refined for this report into five occupational groups: 1) Computer and data analysts / administrators; 2) Software developers and programmers; 3) ICT technicians 4) Math-related professions; and 5) Engineers and technicians.9

The average share of OJPs for digital, engineering and math-related jobs over the period 2021 – 2022 is below 10% in all three countries, at 6.4% in Chile, 7.3% in Colombia and 5.6% in Mexico. However, it should be noted that all of these jobs are more likely to be advertised online than jobs in other occupations as they are high-skill occupations (Cammeraat and Squicciarini, 2021[4]), which means that these shares might be an overrepresentation of the share over the total labour market demand.

In all three countries, the group of digital, engineering and math-related occupations with the highest demand, as indicated by the number of OJPs, is software developers and programmers (comprising the ISCO occupations: web and multimedia developers; applications programmers; software developers; and software and applications developers and analysts not elsewhere classified), see (Figure 2.3). In Chile, software developer and programmers represent 40.8% of the OJPs for digital, engineering and math-related jobs, compared to 37% in Colombia and 45.4% in Mexico respectively.

Figure 2.3. Distribution of the digital, engineering and math-related jobs in 2021 and 2022

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Other indicators also show that software development is becoming an increasingly important industry in Latin America. For instance, in Mexico the number of people trained to be software developers nears 700 000, with Mexican software developers ranking highly in terms of their skills on several different evaluations (Tecla, 2023[41]). Due to its location, companies from the United States also often outsource/nearshore their software development to Mexico, which is another driver for the demand for these professionals (Taplin, 2022[42]).10

Within the broader group of software developers and programmers, software developers by themselves (ISCO 2 512) represent the most highly demanded occupation, as 26%, 23%, and 29% of all digital, engineering and math-related OJPs are for software developer jobs in Chile, Colombia and Mexico respectively. Other sources also report a high need for software developers, for instance the Ministry of ICT in Colombia estimates that in 2022 there was a shortage of 80 000 software developers in Colombia, which is expected to increase to 112 000 in 2025 (González, 2022[43]).

Notably, the tasks that software developers are expected to perform are often very closely aligned with those of many cyber security employees. For instance, the responsibilities of software developers involve designing, developing, testing, and maintaining software solutions (ISCO‑08), tasks that are often shared with cyber security professionals, such as cyber security architects/engineers. These cyber security professionals develop comprehensive security solutions, design infrastructure configurations, and integrate various security technologies. The relatively large share of software developer OJPs suggests that more and more, digital roles are permeating Latin American labour markets and that the demand for those professionals is poised to lead to an increase in digitalisation and, as a consequence, of cyber threats and the need to develop a cyber-skilled workforce.

In Chile a significant volume of digital, engineering and math-related OJPs is allocated to engineers and technicians, accounting for 25.9% of these OJPs compared to 12.5% in Colombia and 10.5% in Mexico. The most highly demanded type of engineers in Chile are civil engineers, with a total number of OJPs of 30 427. Civil engineers nowadays “deal with the management of urban and rural systems, dealing with aspects such as disaster prevention, traffic control, water resource management, garbage treatment and all those activities necessary for well-being of the society.” (Universidad De Chile, 2023[44]).

These new responsibilities for civil engineers require an increased reliance on data and on a good cyber infrastructure. Heightened importance of data brings with it a rise in cyber security threats, such as data breaches, data manipulation vulnerabilities, and being the target of ransomware. Cybercriminals can seek to gain access to sensitive information, which can lead to for instance the theft of personal data, financial information, or trade secrets, or alter data to deceive companies and governments or encrypt data and demand ransom in exchange for decryption. To be able to counter these threats, a skilled cyber security work force is necessary, as well as improved cyber skills for other professionals more generally.

Overall, math-related professions have a larger presence in terms of volumes of new online job postings in Colombia (32.5% of digital, engineering and math-related OJPs) and Mexico (27.3%), compared to Chile (19.6%) (Figure 2.3).11 Financial and investment advisers are the most highly sought-after role within the group for both Colombia and Mexico. For instance, in total there are around 58 900 OJPs specifically looking to hire people for this role in Colombia in between 2021 and 2022. The financial sector is one that bears important ties with cyber security. Financial and investment advisers “develop financial plans for individuals and organisations and invest and manage funds on their behalf” (ISCO‑08). This is a role in which mathematical abilities, analytical thinking and a grasp of information technology are highly valued (Indeed, 2023[45]). Furthermore, (big) data is increasingly more important in finance, which means that finance companies are also more likely to need to hire cyber security specialists to make sure that data is protected.

To put it in other words, the financial sector is becoming increasingly digitalised, fuelling the need for robust cyber security measures. Cyber security professionals have thus become invaluable assets within this sphere, given the industry’s significant dependency on data and networked systems. Financial institutions manage vast amounts of sensitive information, including customer financial data and confidential business intelligence. Breaches can result in considerable financial losses, damaged reputations, and regulatory penalties. Additionally, the financial sector is an attractive target for cyber criminals due to the potential profitability of such data. Therefore, cyber security professionals are crucial for implementing protective measures, such as encryption, firewall configuration, and intrusion detection systems, to safeguard this information. They also play a pivotal role in mitigating attacks, responding to breaches, and ensuring business continuity. As technology continues to evolve, threats become more sophisticated, increasing the demand for these professionals. Consequently, the relationship between the financial sector and cyber security is symbiotic, underpinned by the need to protect valuable data in an increasingly interconnected and risky digital landscape.

The professional profile required in cyber security online job postings

The skills bundle of cyber security professionals

The widespread adoption of digital technologies, coupled with the emergence of new cyber threats, is constantly reshaping the skill requirements for cyber security professionals. This dynamic and highly technical environment presents challenges for both the demand and supply sides of the labour market. On the supply side, workers often struggle to develop the essential skills needed to enter and progress in the cyber security job market. While, on the demand side, organisations also face difficulties in accurately identifying the necessary skill requirements to effectively fill vacancies and retain top talent in the field (OAS & CISCO, 2023[17]).

To foster the development of a skilled cyber security workforce in the region, it is crucial to establish a common framework that reduces mismatches and foster alignment between the demand and supply sides. The efforts made by Chile, Colombia, and Mexico to develop cyber security policies that recognise the importance of workforce capacity building are commendable. However, the effectiveness of these policies will also depend, to some extent, on the data available to characterise skills demand and supply in the sector. Traditional labour market data lack the necessary detail and timeliness to accurately capture them. Analysing online job postings can bridge this gap effectively, providing policy makers with valuable insights into the specific skills in demand and emerging trends. This approach enables policy makers to tailor their capacity-building efforts, respond to evolving labour market needs, and foster a skilled workforce that can thrive in the dynamic cyber security landscape.

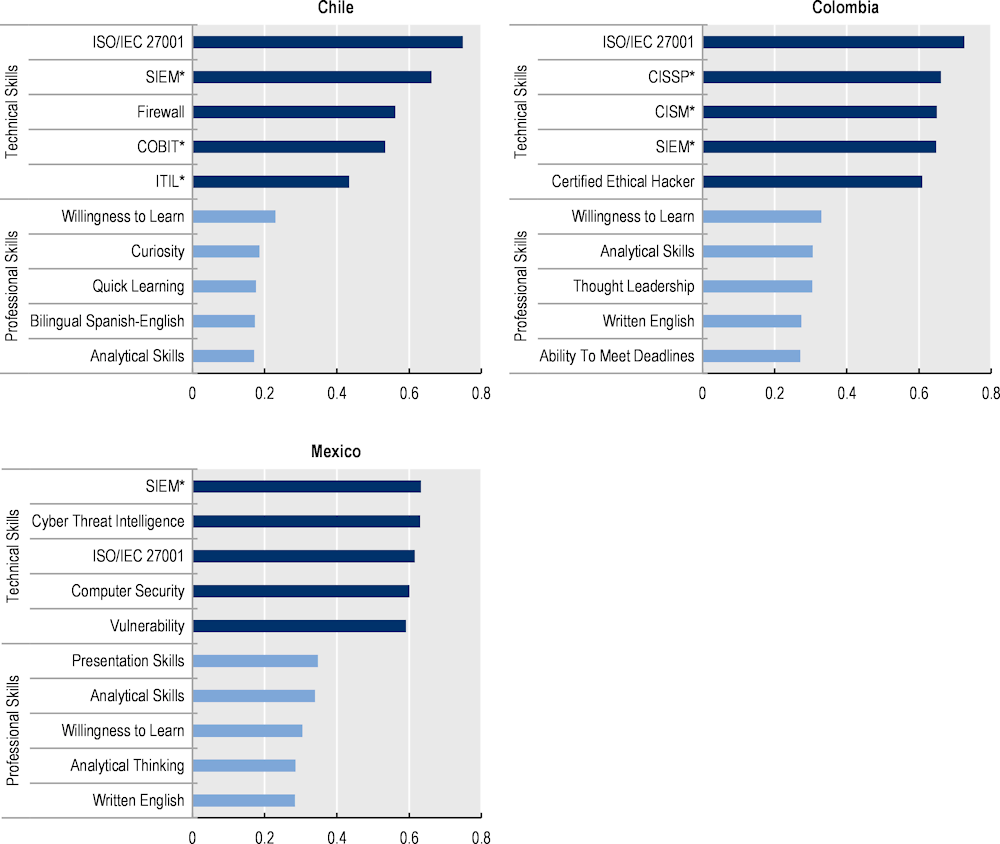

This section examines the specific skill requirements mentioned by employers in cyber security online job postings. The objective is to shed light, from the demand side, on the skill set that typically characterises the demand of employers seeking cyber security professionals. In particular, the analysis presented in Figure 2.4 employs Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques (see Box 2.6) to identify the most relevant technical and professional skills required by employers in each country analysed. As outlined in Box 2.1, technical skills refer to specialised knowledge or expertise required to perform specific tasks within the profession, while professional/transversal skills encompass broader skills not limited to a particular job or discipline but applicable in various situations or work environments.

The data presented in Figure 2.4 indicate that there are two skills that are commonly required across all three countries: familiarity with principles related to ISO/IEC 27001 standard and knowledge of Security Information and Event Management (SIEM).

The ISO/IEC 27001 refers to a collection of requirements, guidelines, and best practices developed by the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) that formally specifies an Information Security Management System (Microsoft, 2023[46]). It provides a structured approach to identifying threats, implementing security controls, and ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information assets. This standard facilitates communication and collaboration among professionals working in the field of cyber security. In addition, many regulatory frameworks and industry-specific standards reference ISO/IEC 27001 as a benchmark for information security. Familiarity with the ISO/IEC 27001 principles is, therefore, crucial for cyber security professionals as this serves as a recognised standard for managing and protecting sensitive information.

On the other hand, SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) is a technology solution that combines information security information management (SIM) and security event management (SEM) tools to provide real-time monitoring, threat detection, and incident response capabilities. SIM helps collecting and aggregating logs and event data from various sources within an organisation’s IT infrastructure. This centralised log management enables efficient monitoring and analysis of security events, making it easier to identify potential threats and security incidents. SEM analyses the collected data in real-time, using correlation rules, statistical analysis, and machine learning algorithms to detect patterns indicative of security breaches, attacks, or policy violations. In recent years, the incorporation of machine learning and AI in SIEM systems has contributed to a more automated and intelligent response to threats (Microsoft Security, 2023[47]). As SIEM solutions store and retain logs, they allow cyber professionals to investigate security incidents, perform forensic analysis, and trace the root causes of breaches or unauthorised activities. This information is vital for understanding the nature of the incident, implementing necessary remediation measures, and preventing future occurrences. Finally, SIEM helps organisations comply with regulatory requirements by providing log collection, retention, and reporting capabilities. It enables cyber professionals to generate compliance reports and demonstrate adherence to industry-specific regulations and standards.

While some cyber security skills requirements are common across countries, others are more specific to the demands of employers in each one of them. The analysis of OJPs in Chile reveals, for instance, that employers put significant emphasis on standards or frameworks for IT service management and IT governance, such as the Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology (COBIT) framework and the Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL). For instance, COBIT is a set of procedures, a roadmap, that helps organisations ensure that their IT processes are running smoothly and aligned with the organisation’s needs. These frameworks, although broader in scope, include strategies for risk management and information security relevant for cyber security professionals. This finding is, to some extent, similar to what is observed in the five Anglophone countries analysed in a previous report: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States (OECD, 2023[8]); where specialised cyber security frameworks such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF), TOGAF, or OWASP were among the most relevant skills required in job postings (Table 2.2 provides more detail on these frameworks).

Results for Colombia indicate that employers in this country explicitly mention cyber-related certifications as a key requirement in prospective candidates, which target mainly highly experience individuals. Three out of the five most relevant keywords extracted from cyber-related OJPs in Colombia are, in fact, certifications: Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP), Certified Information Security Manager (CISM), and Certified Ethical Hacker (CEH). Apart from the specific abilities and competencies certified by each of these certificates, it is worth noting that acquiring CISM or a CISSP certification requires a minimum of five years of relevant experience, while CEH requires two years. This finding suggests that employers in Colombia use certifications as a tool to signal their requirements for very specialised skills and experienced profiles in cyber security. The use of certification may be more relevant and useful in Latin American countries than in other countries (see OECD (2023[8])) as most of these countries have not implemented skills frameworks or guidelines that help employers to map workers profiles to their business needs.

Mexico shows a relatively more varied demand for skills across job postings for cyber security professionals. Apart from ISO/IEC 27000 and SIEM, Mexican employers are also likely to demand knowledge of cyber threat intelligence and computer security. The latter is a broad field gathering all those different systems and policies designed to protect the confidentiality and privacy of information processed and stored on a computer. There are four main types of computer security depending on the physical or digital infrastructure, namely, application, information, network and endpoint security (Berkeley Extension, 2023[48]). Cyber threat intelligence is a key component of security systems referring to a set of techniques, tactics and procedures aimed to prevent and mitigate cyber attacks in an organisation’s network (Fortinet, 2023[49]).

Figure 2.4. Skill bundle demands in the cyber security profession

Note: The relevance scores are derived from the semantic analysis of online job postings for each country in 2022. The closer the score to 1, the more relevant the skill for the cyber security occupation in the country at hand. For more details on the methodology see Annex 2.A * SIEM: Security Information and Event Management, CISSP: Certified Information Systems Security Professional, CISM: Certified Information Security Manager, COBIT: Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies and ITIL: Information Technology Infrastructure Library.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

As in other occupations, along with technical skills, cyber security professionals also need professional/transversal skills, for example to communicate procedures and strategies and to convey technical messages and concepts. Results in Figure 2.4 indicate that transversal skills are typically less relevant than technical skills in cyber security job postings.12 Among the most relevant transversal skills, Chile, Colombia and Mexico share three: analytical skills, willingness to learn, and English (more precisely, the skills keywords “written English” in Colombia and Mexico, and “bilingual Spanish-English” in Chile).

The enhancement of English language proficiency stands as a crucial factor in mitigating the workforce cyber security gap in Latin America. This region is predominantly marked by low levels of English competency, both in oral and written forms. Particularly, countries like Mexico and Colombia exhibit some of the most substantial deficiencies in English proficiency within the region13 (see Education First (2022[50])). This proficiency gap creates significant obstacles in the cultivation of cyber security skills, given that relevant training materials, industry standards, and certifications are primarily in English. As a result, organisations often struggle when attempting to implement cutting-edge cyber security tools and technologies.

As explored in Chapter 3, potential short-term solutions could include offering cyber security training in local languages or providing translation services (for instance, those powered by AI translation tools). This approach could help to lower the barriers to accessing cyber security education and resources. Nonetheless, for a more sustainable solution, long-term strategies should focus on fostering English language learning, thereby increasing English proficiency levels in Latin America. By increasing English proficiency, not only can Latin America close its cyber security gap, but it can also unlock wider economic, cultural, and educational opportunities. This, in turn, will strengthen Latin American countries’ global competitiveness and enhance its ability to tackle modern digital challenges.

Often, employers in LATAM put also high emphasis on candidates that are “willing to learn” within the cyber security profession. Candidates of this type usually tend to look for new learning opportunities and developing skills to improve their work performance by searching for training, among other strategies (Indeed, 2023[51]). In the case of cyber security, results highlight that a rapidly evolving cyber security landscape requires workers to be open and ready to keep learning new concepts and technologies throughout their professional career.

Results in Figure 2.4 also show that employers seek candidates with strong analytical skills. Critical thinking, problem solving, logical reasoning and creativity help individuals to analyse topics or problems, enabling them to propose complex ideas and effective solutions (Indeed, 2023[52]). As cyber threats continue to advance in complexity, it becomes imperative for professionals to possess abilities to analyse and interpret vast amounts of data efficiently. This expertise enables them to identify patterns and detect anomalies that may indicate potential security breaches or vulnerabilities. With the ever-increasing frequency and sophistication of cyber attacks, cultivating strong analytical skills within the cyber security workforce in Latin America is vital to safeguarding the region’s technological infrastructure and improving its cyber resilience.

When comparing these results to those obtained for the five Anglophone countries examined in a previous report (OECD, 2023[8]), the analysis show that employers in all countries prioritise candidates with analytical skills, such as problem solving, critical thinking and strategic thinking, among professional/transversal skills. In the case of Anglophone countries, results showed that employers in those countries were also placing high importance on communication and persuasion skills, while these traits are less prominent in OJPs in LATAM countries. Communication and persuasion skills play an important role facilitating interaction between cyber security teams, other organisational departments, and external clients, especially when explaining technical concepts to non-technical stakeholders. These skills are particularly important in cyber security managerial roles, but data show that fewer of these job postings are currently published in Latin American countries compared to more technologically advanced countries (see also (OECD, 2023[8])).

Box 2.6. Using machine learning to assess the relevance of skills in cyber security occupations

Recent advances in machine learning techniques led to the development of language models which have the objective of understanding the complex relationships between words (their semantics) by deriving and interpreting the context those words appear in. Language models (in particular Natural Language Processing- NLP- models) interpret text information by feeding it to machine learning algorithms that derive the logical rules to interpret the semantic context in which words appear.

NLP models are therefore better suited for the analysis of text information. As such, they are used for the analysis of OJPs in this section of this report. These algorithms allow the calculation of semantic similarity measures between skills and occupations. Skills that are more semantically similar to a certain occupation are interpreted as being more ‘relevant’ to the occupation (see Annex 2.A for methodological details).

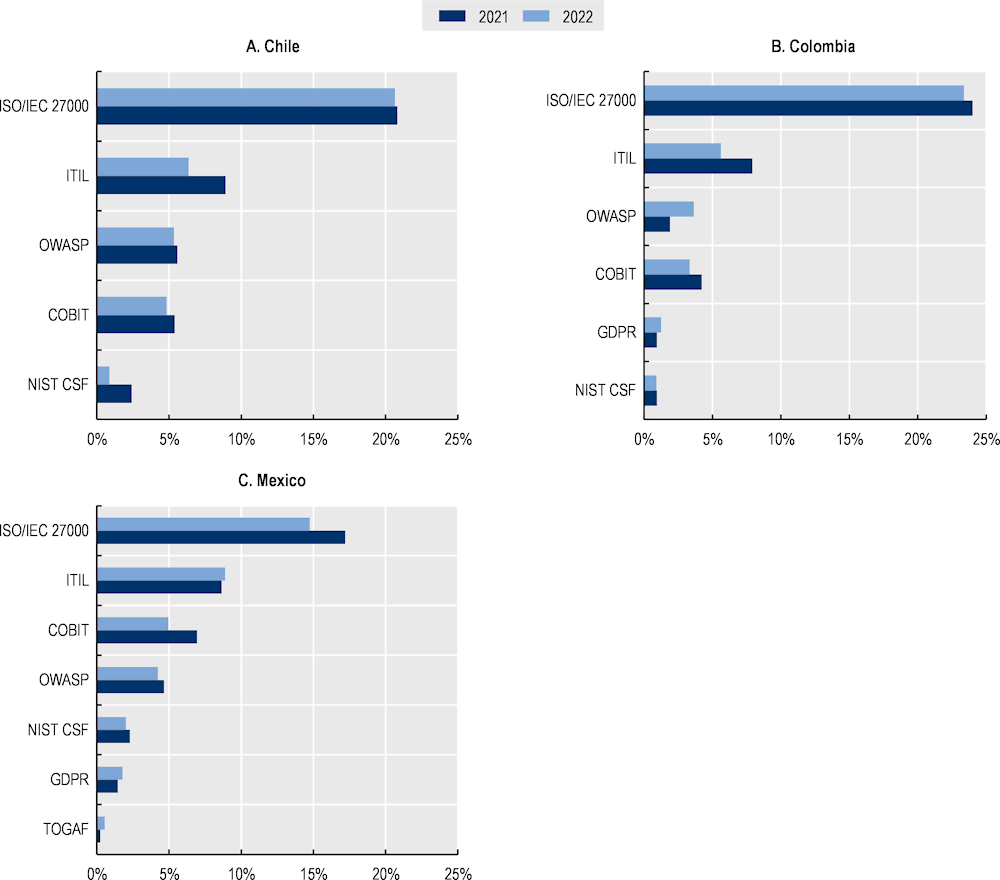

The demand for cyber security frameworks/standards in online job postings

In the rapidly evolving landscape of cyber security, the implementation of well-established frameworks, as well as the adherence to industry standards, play a significant role in ensuring effective cyber security practices. This section explores in more detail the demand in Chile, Colombia and Mexico for cyber security frameworks such as NIST CSF, ITIL and COBIT, and standards such as the ISO/IEC 27000. These frameworks and standards provide essential guidance, best practices, and a common language for organisations and professionals, enabling them to establish comprehensive cyber security strategies, mitigate digital security risk, and enhance overall cyber security resilience.

Adherence to cyber security standards, such as ISO/IEC 27000, is crucial for the cyber security strategy of Latin American organisations. Figure 2.5 shows that this is the most mentioned standard in cyber security OJPs in 2022, ranging from 15% of the total number of OJPs advertised in Mexico during that year to 25% in Colombia. A description of this standard is provided in the previous subsection. It is worth noting that the ISO/IEC 27000 standard enables Latin American organisations to adopt internationally recognised best practices, enhance their credibility in the global market, and demonstrate their commitment to protecting sensitive information.

In addition to the ISO/IEC 27000 standard, cyber security frameworks are vital in the Latin American cyber security sector due to their ability to provide structured approaches and methodologies for addressing cyber security threats. These frameworks offer organisations a systematic and well-defined set of processes, practices, and controls that can be tailored to their specific needs and industry. Compliance with most of the frameworks listed in Figure 2.5 is voluntary. An exception is the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for which compliance is compulsory for companies selling products/services in the European Union (GDPR EU, 2022[53]). Table 2.2 provides a brief description of each framework/standard listed in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5. Demand for cyber security standards/frameworks

Note: See Table 2.2 to explore a basic description on cyber security standards/frameworks.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

The Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) is a widely adopted framework for IT service management (Axelos, 2023[54]). In Mexico nearly 10% of the OJPs advertised in 2022 mention ITIL, and this proportion is slightly above 5% in Chile and Colombia. Although ITIL does not specifically focus on cyber security, it provides valuable guidance for organisations in managing their IT services. By incorporating ITIL into their cyber security practices, organisations can establish robust incident/event management processes, ensure proper access management and align IT security management efforts with overall IT service management objectives (Coursera, 2023[55]).

The NIST CSF is less common in cyber security OJPs in 2022, less than 3% of OJPs mentioning it. A surprising result given the international relevance of this framework as a tool for cyber security risk management. The NIST CSF provides a flexible framework consisting of five core functions: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover, that help organisations assess and improve their cyber security posture. Even though this framework was specifically designed for the United States, it has been adopted as part of the national cyber security strategies of different countries, such as the United Kingdom, Italy, Switzerland and Uruguay (OAS & AWS, 2019[56]). In this line, a previous report (OECD, 2023[8]) shows the high relevance of the NIST CSF among technical skills in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States.

While frameworks as the NIST CSF could serve as valuable resources for organisations in Latin America aiming to enhance their cyber resilience, their widespread adoption in the region encounters certain challenges. These challenges include the need for commitment from senior management to adopt a cyber security strategy, the establishment of an organisational risk culture and tackling the scarcity of skilled professionals to lead the implementation process (OAS & AWS, 2019[56]). Overcoming these obstacles is essential to effectively leverage frameworks/standards’ guidance, promote best practices, and foster collaboration, ultimately bolstering cyber security efforts in Latin America.

Table 2.2. Standards/frameworks mentioned in OJPs from Chile, Colombia and Mexico

|

Name |

Acronym |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

International Organization for Standardization and International Electrotechnical Commission 27 000 standards |

ISO/IEC |

The ISO/IEC 27000 standards comprise requirements, guidelines and best practices for information security management. Specifically, OJPs collected refer to the standards ISO/IEC 27001 (Information Security Management System) and ISO/IEC 27002 (information security control objectives). |

|

Information Technology Infrastructure Library |

ITIL |

Framework including best practices for IT service management and customer experience. ITIL includes provisions for security management, including incident management and access management guidance. |

|

Open Web Application Security Project |

OWASP |

Open-community contributions to improve web security with guidance, standards, open-source tools and technologies to help security professionals create trusted applications. |

|

Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology |

COBIT |

This framework helps organisations to manage information technology (IT) governance based on guidelines and best practices. It aims to align IT with business goals, manage digital security risk as well as improve efficiency |

|

National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework |

NIST CSF |

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework is a set of guidelines for managing and reducing cyber security risk. It helps organisations identify, protect, detect, respond to, and recover from cyber attacks. |

|

General Data Protection Regulation |

GDPR |

The GDPR is a regulation that sets guidelines for the collection, processing, and storage of personal data for citizens of the EU. It also applies to companies outside the EU that collect, process or store personal data of individuals located in the EU. |

|

The Open Group Architecture Framework |

TOGAF |

TOGAF is a framework used by enterprises as a standard for designing and implementing enterprise IT architecture. It aligns IT systems with business goals and objectives. |

Source: OECD elaboration based on International Electrotechnical Commission (2023[57]), ISO/IEC 27000 series, https://syc-se.iec.ch/deliveries/cybersecurity-guidelines/security-standards-and-best-practices/iso-27000-series/; The Open Group (2022[58]), The TOGAF® Standard, https://www.opengroup.org/togaf; OWASP (2022[59]), https://owasp.org/about/; NIST (2022[60]), NIST Cybersecurity Framework, https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework/getting-started; ISACA (2019[61]), COBIT: An ISACA Framework, https://www.isaca.org/resources/cobit; Coursera (2023[55]), What Is ITIL?, https://www.coursera.org/articles/what-is-itil; and General Data Protection Regulation (2022[53]), Does the GDPR apply to companies outside of the EU?, https://gdpr.eu/companies-outside-of-europe/.

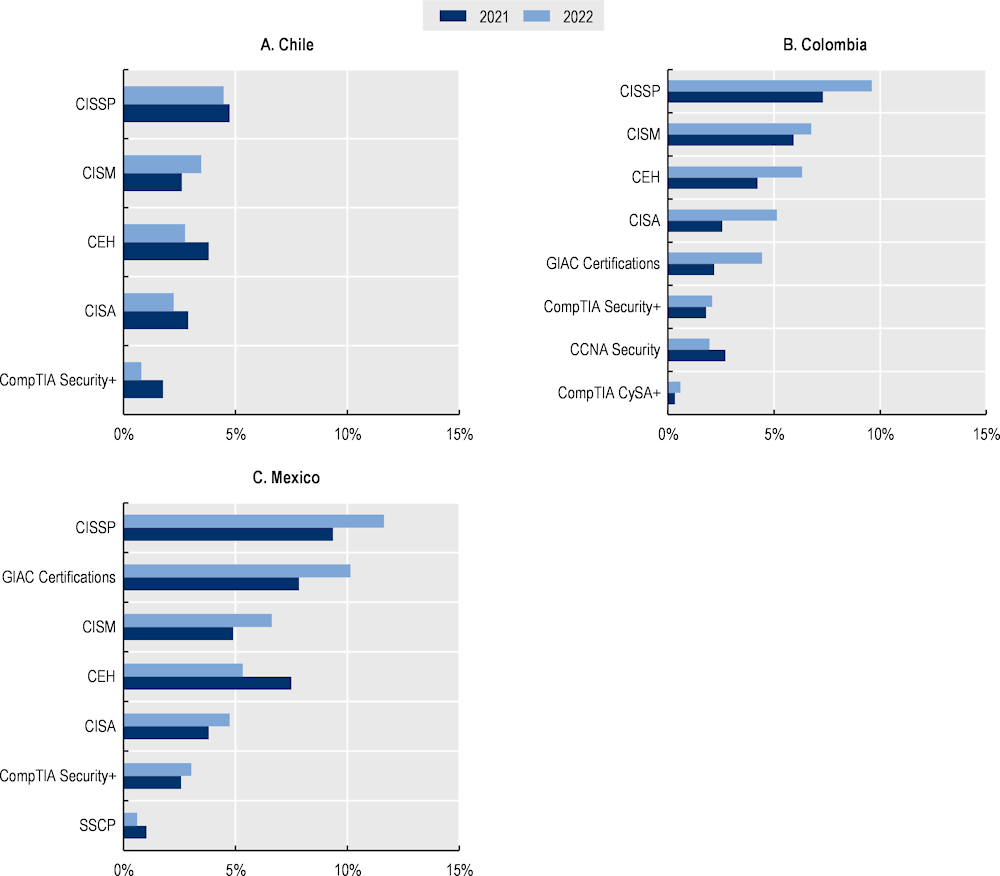

The demand for cyber security certifications

The results depicted in Figure 2.4 indicate a significant emphasis on certifications in cyber security OJPs. This is particularly evident in Colombia, where the relevance of certifications for the cyber security profession is very high compared to other skill requirements. In Mexico, certifications such as CISSP and CISM are also very relevant for cyber security professionals (relevance scores above 0.5), suggesting that they are usually key requirements used by employers wanting to hire. In Chile, however, relevance scores are low (slightly above 0.3). These values imply that Chilean employers may not prioritise certifications to the same extent as their counterparts in the other two countries when hiring cyber security professionals.

This result also highlights how certifications can represent a useful tool to provide a standardised measure of candidates’ knowledge and skills in highly specialised areas such as cyber security. In Latin America, in particular, where the cyber security industry is still developing and evolving, certifications can serve as a common language to assess qualifications and enhance professional credibility of cyber security workers.

Taking a closer look at the frequency with which cyber-related certifications are mentioned in job advertisements across each of the three Latin American countries, Figure 2.6 reveals a varied pattern. Certifications are mentioned in less than 5% of the cyber security OJPs in Chile. This proportion is comparatively lower than that observed in Mexico and Colombia, where the most commonly mentioned certifications appear in approximately 10% of cyber security OJPs. Furthermore, the certifications most frequently mentioned in Mexico and Colombia typically target experienced professionals, as they often require more than five years of relevant work experience, as detailed in Table 2.3.

CISSP, for instance, is one of the certifications most typically mentioned in OJPs for cyber security professionals across the three countries analysed in this report. Approximately 10% of OJPs in Colombia and Mexico mentioned this certification. CISSP is widely recognised as a standard for information security professionals and demonstrates expertise in various domains, including security and risk management, asset security, and communication and network security. This certification requires at least five years of experience and a four‑year college degree. It is granted to professionals with a strong foundational and comprehensive knowledge of cyber security principles, making it crucial in managerial or leadership roles.

The Certified Information Security Manager (CISM) is another certification which shows a large number of mentions. CISM validates a professional’s expertise in managing and overseeing information security programmes, governance and risk management. With the increasing complexity and frequency of cyber threats, organisations recognise the need for professionals who can develop and implement effective security strategies. The CISM is aimed at experienced workers with a minimum of five years of experience in information security management. This certification indicates a candidate’s ability to align security initiatives with organisational objectives, making them valuable assets in protecting sensitive information.

Finally, the demand of the Certified Ethical Hacker (CEH) certification in OJPs experienced growth in Colombia, from 4.2% in 2021 to 6.3% in 2022. Conversely, the mentions of this certification decreased in Chile and Mexico. The CEH is given by the EC-Council and aimed at mid-level professionals with at least two years of experience interested on demonstrating experience as an ethical hacker. Ethical hacking involves assessing systems and networks for vulnerabilities, enabling organisations to proactively identify and address security weaknesses. With the rise of cyber attacks and the importance of proactive security measures, professionals with CEH certifications are sought to strengthen an organisation’s defence mechanisms. Ethical hackers play a crucial role in conducting penetration testing, vulnerability assessments, and security audits, thereby helping organisations enhance their cyber security posture.

While the results highlight the importance placed by employers on using some certifications, the analysis also suggests that employers in the region could benefit from using a much wider (and more nuanced) range of cyber security certifications to select candidates, especially when looking to hire workers mid- and entry-level positions. The most requested certifications discussed above, in fact, are typically obtained only by very experienced workers, while employers use them also in job postings for entry-level positions.

In the Latin American context, in particular, this misalignment becomes apparent in the disparity between the positions that organisations aim to fill and the certification prerequisites they impose. According to the Organization of American States and CISCO, many Latin American organisations seek entry-level cyber security professionals, yet simultaneously demand certifications such as CISSP, which typically mandate a minimum of five years of relevant work experience (OAS & CISCO, 2023[17]). This discrepancy between the desired job level and certification requirements further complicates the efficient matching of talent to available positions in the region’s cyber security workforce.

This mismatch creates obstacles for both job seekers and employers. Job seekers who possess the necessary technical skills and knowledge for entry-level positions may be deterred from applying due to the certification requirements. Conversely, employers may face difficulties in finding candidates who meet the certification prerequisites, leading to prolonged vacancies and talent shortages.

This result also suggests the need for reinforcing the awareness amongst employers about a more varied and nuanced ecosystem of available certifications in the market, as many employers may remain unaware of their existence or value.

Figure 2.6. Demand for cyber security certifications

Note: See Table 2.3 to explore basic information about the certifications required in OJPs.

Source: OECD calculations based on Lightcast data.

Table 2.3. Certifications mentioned in OJPs from Chile, Colombia and Mexico

|

Name |

Acronym |

Provider |

Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Certified Information System Auditor |

CISA |

ISACA |

+ 5 years |

|

Certified Information Security Manager |

CISM |

ISACA |

+ 5 years |

|

Certified Information Systems Security Professional |

CISSP |

(ICS)2 |

+ 5 years |

|

GIAC Certified Forensics Analyst |

GCFA |

GIAC |

+ 5 years* |

|

CompTIA CySA+ |

- |

CompTIA |

+ 4 years |

|

Certified Ethical Hacker |

CEH |

EC-Council |

+ 2 years |

|

Cisco Certified Network Associate Security |

CCNA Security |

CISCO |

+ 1 year |

|

Systems Security Certified Practitioner |

SSCP |

(ICS)2 |

+ 1 year |

|

CompTIA Security+ |

- |

CompTIA |

0 years |

|

GIAC Certified Incident Handler |

GCIH |

GIAC |

0 years |

|

GIAC Certified Intrusion Analyst |

GCIA |

GIAC |

0 years |

|