Many of the policy challenges faced by countries at the domestic level are increasingly global in nature and require democracies to both deepen their models of governance, while protecting them from external foreign undue influence. This chapter first discusses how democracies can ensure that they are better able to address challenges that require global responses and co-operation, such as climate change, the implications of digital transformation, preventing future crises, and other problems with clear transboundary dimensions and knock-on effects. In particular, it looks at building public governance capacities, strengthening national institutions and leveraging governance tools and innovation to enhance capacity for global action. The chapter then explores how governments can build resilience to foreign undue influence by recognising and addressing loopholes in their governance systems that leave democratic societies at risk of undue influence from some autocratic regimes.

Building Trust and Reinforcing Democracy

3. Stronger open democracies in a globalised world: Embracing the global responsibilities of governments and building resilience to foreign influence

Abstract

3.1. Introduction

Many of the policy challenges faced by OECD democracies at the domestic level are increasingly global in nature, and require effective global responses, also grounded in co-operation. These challenges include, among others, climate change, addressing the global implications of the digital transformation, preventing future global crises, such as pandemics and famine, and their implications in terms of migration, and ensuring essential health and industrial supplies.1 At the same time, democracies face the destabilising impacts of some foreign undue influences on democracy also fuelled by globalisation, through mis- and dis-information, the use of regulatory loopholes to influence election processes and other decision making, as well as information eco-systems. In order to reinforce their democracies in a globalised world, governments must both enhance their capacities to more effectively tackle global challenges, while building resilience to foreign influence.

Democracies have, for many years, been at the forefront of global policy efforts and international co-operation. The rules-based international order that took shape after World War II, which includes the founding of the Marshall Plan and the OECD, was built around the need to build healthy and open market economies and protect economic freedoms, the rule of law, and the promotion of human rights. Advanced liberal democracies, in particular, have since played a critical role in driving international co-operation to secure economic and global financial stability and promote economic growth and development over several decades. Nonetheless, while the benefits of trade and economic growth have been substantial, many of the global challenges that are faced by countries today are far more complex and transboundary in nature than ever before, putting a much greater strain on national governments’ capacities.

The COVID-19 crisis has been a case in point. While many governments demonstrated their ability to respond at speed and scale to the challenges of a global pandemic, many countries gave the impression of being caught “off guard” (OECD, 2021[1]). Governments have faced both a global, social, economic and health crisis, together with a difficult geopolitical environment. In many cases democracies have been working in competition with narratives promoted globally by some autocracies about their capacity to address the situation. Over the course of the crisis, democracies have shown great capacity to deploy vaccines with significant levels of trust and have been able to engineer a rebound of their economies and societies to near normal.

In open democracies, citizens’ trust in government matters for governments to be able to, among other things, respond effectively to global challenges. This was very clearly demonstrated during the deployment of the various COVID-19 measures, such as lock-downs and social distancing. Evidence abounds also on the nexus between climate change and trust (see Chapter 4). There are therefore clear incentives for governments to embrace a more global perspective in their leadership, institutions and public governance tools with a view to addressing these challenges in a way that can be better understood and appreciated by citizens and ensure more effective global outcomes.

At the same time, in order to reinforce democracy in a globalised world, it is also necessary to build resilience to foreign undue influence. One of the most significant challenges that democracies must face in a globalised world is the destabilising impacts of foreign undue influences on democracy. This includes, for example: the spread of foreign-born mis- and dis-information (see Chapter 1); influencing elections and democratic governments by opaque means; influencing civic institutions by pressuring academic institutions; undermining the enabling environment for media and civil society; and abusing Residence-by-Investment and Citizenship-by-Investment schemes to hide or facilitate financial and economic crimes, including corruption, tax evasion and money-laundering. In the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it has become clear that OECD governments need to do more on this front. Strong public governance responses to these influences, in particular, could play a significant role in reinforcing democracy.

This chapter considers how governments can seek to reinforce democracy in a globalised world from two main angles:

First, how governments can build their public governance capacities to ensure that they are fit to address global challenges; and

Second, how democracies can use public governance solutions to build resilience to foreign undue influence.

3.2. Building public governance capacities to ensure that governments are fit to address global challenges

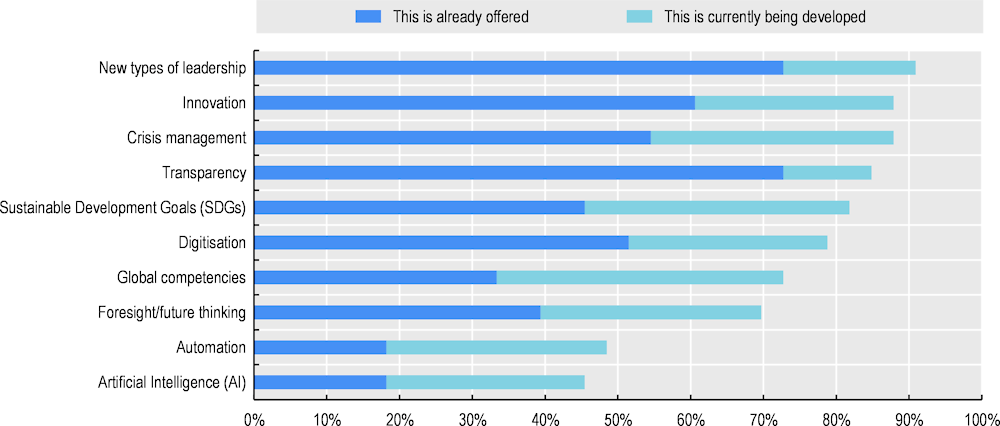

Democracies face difficulties in securing citizen’s trust in government to address global challenges. Results from the OECD Survey on the Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions (OECD Trust Survey) show that, on average across countries, people are most likely to express interest in global co-operation to address issues like climate change, terrorism, and pandemic preparedness (Figure 3.1). Yet, there is still relatively low public support for global co‑operation to target these issues; only around half of respondents call on governments to work together to address climate change. Part of the issue may be that people are unwilling to accept the costs. Another likely factor is a government’s perceived competence. Many people are not confident that public institutions are competent and reliable enough to deliver policies effectively, and for long enough, to generate benefits (OECD, 2022[2]).

Figure 3.1. Respondents most likely to support global co-operation to resolve challenges like climate change, terrorism and pandemic preparation

Note: Figure presents the unweighted OECD average share of responses to the question “Which of the following issues do you think are best addressed by working with other countries than by your country alone? Please choose your top three issues for global co-operation.” Response choices options are indicated in the x-axis. For more detailed information on the survey questionnaire and processes in specific countries, please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

OECD (2022[3]), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en

This disenchantment is also fuelled by the increasingly common perception that global co-operation is a game of national elites and global corporations. This is demonstrated in the way voters’ support for political parties promoting liberal internationalist policies in the West has almost halved since the 1990s (Trubowitz and Burgoon, 2022[4]), while votes for economic nationalist and isolationist parties in Western Europe have increased significantly between 1985 and 2015 (Colantone and Stanig, 2018[5]). Under this context, any new global challenge without an effective policy response risk making matters worse. Bringing citizens on board with addressing global challenges is key.

Addressing global challenges will require a transformation of public governance approaches and institutions to ensure that they are fit to go global. This first section looks at three key areas where democratic governments should focus their efforts to achieve this:

Steering action to tackle global challenges through building trust.

Strengthening national institutions to make them fit to go global.

Leveraging governance tools and innovation to enhance capacity for global action.

3.2.1. Steering action to tackle global challenges through building trust

Addressing any global challenge requires first and foremost setting an agenda and engaging stakeholders and broader society to build consensus and steer action. Ensuring meaningful societal engagement and consensus building is the essence of democracies. It is also important to be accountable for results and to be able to communicate progress which requires effective monitoring. This section focuses on governments’ role to steer action to tackle global challenges and maintain public trust, with an emphasis on leadership and vision, societal engagement and monitoring progress.

Leadership and vision

Outlining a clear, long-term strategic vision to define priorities and set an agenda is critical to address global challenges. Global challenges often span across multiple policy domains and involve a variety of actors and contending interests. Strong leadership is essential to set a whole-of-society approach, steer coherent policy development in line ministries and translate the strategic vision into concrete and measurable actions.

The centre of government (CoG) plays a key role at strategic vision setting, yet many countries they still struggle to set a pathway to address issues that go beyond the electoral cycle. In 2017, more than three-quarters (78%) of survey respondents from OECD centres of government reported the existence of a document outlining a strategic vision document for their country to address global and strategic priorities. However, for more than a third of countries (35%), this document only covered a period of 5 years or less, the likely period of an electoral cycle. Furthermore, in a number of countries the ruling party’s manifesto acts as the strategic vision document making the concept of ‘vision’ a synonym with a political strategy rather than setting long-term orientations crucial in addressing complex and interconnected global issues such as sustainable development and climate action. There does, however, appear to be some improvement in long-term strategic vision setting since 2013. In 2013, almost two-thirds (63%) of countries only issued short-term strategies, in comparison to recent results when this had dropped to a third. Only 3 countries, Japan, Luxembourg and Norway reported having a document with a more than 20-year horizon. Many of the more recent long-term strategies have been dedicated to climate action. Taking this approach to other global challenges may also help deliver results. For example, since 2017, all EU Member States have published their own National Cyber Security Strategies (ENISA, n.d.[6]).

Engaging with citizens on global action

Setting the vision is only the first step. Involving citizens and wider stakeholders in the policy cycle is critical to ensure better policy outcomes, build trust in public institutions and strengthen the democratic mandate for urgent and sometimes difficult reforms that need buy-in from all stakeholders. Awareness-raising and participation in line with the OECD Recommendation on Open Government, can also ensure that policies designed to address global challenges are more effectively implemented, through greater understanding and compliance on the part of citizens.

Governments can use a variety of approaches and opportunities to engage with citizens on global issues. This ranges from consulting with civil society organisations ahead of international summits, to more innovative citizen deliberative mechanisms. Leadership of international fora (G7, G20, EU, APEC, for instance) offers a good opportunity for countries to ramp up engagement efforts with civil society. Governments can also mobilise citizen engagement through wider fora, targeted at specific global challenges, such as the European Citizens' Panels for the Conference on the Future of Europe or The Global Citizens' Assembly for COP26 (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Citizen engagement on international agendas: Europe and COP26

The Conference on the Future of Europe

The Conference on the Future of Europe was a citizen-led series of debates and discussions that ran from April 2021 to May 2022, enabling citizens from across Europe to share their ideas on the common future of the EU.

The European Citizens’ Panels were a key feature of the Conference, bringing together four panels each comprising of 200 citizens reflecting the EU’s demographic and social diversity to debate key topics. At least one third of the participants in each panel were younger than 25, to ensure that the voice of youth and younger generations were represented. Their deliberations were informed by the recommendations of national Citizens’ Panels organised in advance across Member States.

The final session of the four Panels resulted in recommendations discussed in the Conference Plenary by 20 citizens selected from each panel that deliberated jointly with the representatives of the EU institutions and advisory bodies, national Parliaments, social partners, civil society and other stakeholders.

The resulting proposals were put forward to an Executive Board, whose subsequent report was examined for follow-up by the European Parliament, the EU Council, and the European Commission – each within their own sphere of competences in accordance with the EU Treaties.

COP26 Global Citizens’ Assembly

The COP26 Global Citizens’ Assembly was a first initiative aimed to give everyone a seat at the table on the course of global climate action at the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow.

A 100 members Core Assembly was selected by a lottery, using an algorithm that ensured accurate representativeness. The members spent 68 hours deliberating together over 11 weeks, on the question of “how can humanity address the climate and ecological crisis in a fair and effective way?”. Community Assemblies, which anyone could form and organise by registering on the official website were run simultaneously, with their proposals being fed into the final report and public declaration. The long term vision of the initiative is to create a permanent global citizens’ assembly that by 2030 will have over 10 million people participating annually. The goal is to have an assembly being recognised as a powerful driver with the ability to tackle not only climate change but other global crises.

Strategic and inclusive public communication efforts are key to build support and consensus toward effective policy action for global challenges. In a media and information landscape crowded with a large volume of actors and content, Governments need to focus on building trustworthy narratives and engaging with all constituencies. For example, the Canadian government launched an environment and climate change campaign to bring citizens closer to this issue, including opportunities to engage in conversation, public information and activities for children (Government of Canada, 2022[9]).

It is crucial for governments to engage young people in decision making on global challenges as the costs of many of the reforms needed for successful action will fall on future generations. Young people, however, tend to have disproportionately little say in the management of global challenges given their lack of participation and representation in traditional democratic processes. In OECD countries, youth join political parties and participate in elections less than their older peers: 68% of young people go to the polls compared to 85% of people over 54 on average (OECD, 2020[10]). Governments can engage young people through multiple mechanisms including: public consultations and innovative deliberative processes targeting youth, affiliating advisory youth councils to government or specific ministries (as occurs in 53% of OECD countries), or through setting up youth councils at the national (in 78% of OECD countries) and subnational levels (in 88% of OECD countries) (OECD, 2020[11]).

Charting a clear and long term way ahead to address global issues requires comprehensive engagement with all actors – including the private sector. In many key global challenges, private sector actors play a pivotal role. For example, big tech and energy companies are among key actors for the digital transformation and the climate transition respectively. As a result, for each of the relevant global challenges, governments should engage with the entire ecosystem of relevant stakeholders. Private sector coalitions and other non-governmental stakeholders are increasingly active in the global debates and shaping policy responses to global challenges. Close engagement can also help promote certainty and transparency about government’s long-term policy objectives encouraging trust of financial markets and a predictable environment for investment. For example, the OECD’s Centre for Responsible Business Conduct uses RBC standards and recommendations to shape government policies and help businesses minimise the adverse impacts of their operations and supply chains, while providing a venue for the resolution of alleged corporate, social, environmental, labour or human rights abuses (OECD, n.d.[12]).

Monitoring and demonstrating progress on global action

Accountability is critical to sustain public consensus and trust in government action towards tackling complex global issues. Policy monitoring can show whether public decisions and expenditure have achieved their intended objectives and are producing the expected results. Monitoring can be complemented by evaluation mechanisms to provide evidence on what policies work, why and for whom, in addressing these complex issues (OECD, 2020[13]). However, experience in implementing the Recommendation of the Council on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (OECD, 2010[14]) shows there is room for improvement in aligning monitoring and evaluation frameworks on key global issues, enhancing government’s ability to track policy impacts, and adopting a systemic monitoring of whole-of government impact.

Policy monitoring of the implementation of the government’s strategic priorities is mostly undertaken at the level of Centres of Government. Some countries are making progress in engaging the public sector and the machinery of government in delivering on these global efforts. For instance, the French Government created an online platform allowing citizens to track progress made in priority measures on the territory as a whole, by region and by department (Government of France, 2021[15]). This includes a thematic priority on the green transition and sub-priorities on global issues such as drug trafficking.

The effectiveness of monitoring progress critically depends on the capacity to collect homogenous and relevant data. Standardisation can help benchmark the effectiveness of country-level policy responses to global challenges. Major international policy agendas, for example around Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the green transition, are paired with a monitoring and evaluation system with indicators, targets and milestones, that helps governments track and benchmark progress. International organisations have an increasing role in standardising data collection on how countries track their progress in fighting against global challenges. The OECD International Programme for Action on Climate (IPAC) for example, supports country progress towards net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) through regular monitoring, policy evaluation and feedback on results and good practices. These methods of international benchmarking can be a positive enabler for change, by allowing countries to see where they stand on international standards and encouraging them to do better.

Sharing the lessons drawn from policy evaluation between countries can help governments learn from each other and strengthen responses to global challenges. Governments also increasingly relied on existing evaluations of past and similar crises worldwide during the crisis, thus enabling them to provide credible evidence under short time constraints and with limited resources. The OECD provided a synthesis of government evaluations on the COVID-19 pandemic, with useful evidence on how to design and implement ongoing policy responses to crisis – as well as to increase forward-looking capacities to manage other large future shocks (OECD, 2022[16]). Colombia’s Department of National Planning, for instance, conducted an evidence gap map in order to first identify where evidence was needed on the effects of the COVID-19, with special attention to economic and social issues (such as employment, social and human capital, mental health, gender issues, etc.) (OECD, 2022[16]).

Making sure that such evidence is publicly available can also support the transparency of decision making on these complex global challenges. Knowledge-production and information-sharing has increased during the pandemic, where international co-operation has played a key role. In January 2020, 117 organisations – including journals, funding bodies, and centres for disease prevention – committed to providing open access for peer-reviewed publications for the duration of the outbreak and to sharing results immediately with the World Health Organization (WHO) (OECD, 2020[17]). Yet, many challenges regarding the availability and accessibility of monitoring and evaluation evidence to combat global challenges remain. In many cases, data is not sufficiently findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable. International organisations may still have an important role to play to help countries overcome these challenges. Increasing the sharing of monitoring data and evaluation evidence can also help governments account for potential spillover effects of national policies and potential cross boundary trade-offs.

3.3. Strengthening national institutions to make them fit to go global

While international relations often remain the prerogative of ministries of foreign affairs, most national institutions nowadays deal with public policy issues that extend beyond national borders. This calls for a strengthening of government institutional settings and co-ordination capacities to address issues that span borders and to promote policy coherence. There is also a need to invest in the skills of public servants to tackle global challenges.

3.3.1. Setting up government to go global

Major transboundary challenges demand an increased focus on international co-operation and a transformation of government institutions. Government bodies are typically designed and structured to focus on singular policy issues or narrow subject domains. However, setting up government to address global issues requires an overhaul of government structures and institutions. Global policy issues are no longer the exclusive remit of ministries dealing with foreign affairs. Governments have had to strengthen their capacity and mechanisms for horizontal co-ordination so that the necessary expertise can be mobilised in an effective manner across departments, aligning priorities and resolving policy divergences between ministries, reducing scope for fragmentation, duplication and wasteful spending.

CoGs have a key role to play in promoting co-ordination and connecting the domestic and international policy agendas. International portfolios are often placed closer to the Head of Government office to enhance the co-ordination of international policy issues. OECD evidence shows that in 2018 68% of respondents of the centre of government shared responsibility on international policy issues, against 48% in 2014 (OECD, 2018[18]). This development is reflected in institutional settings in Korea, with the Director General for Foreign Affairs and National Security Policy situated in the Prime Minister’s Office. Similarly, Sweden and Estonia have integrated offices at the centre of government to manage EU Affairs. It is also reflected in the role of the G7 and G20 Sherpa positions sitting at the centre of government to support their leader at the top level of international dialogue and negotiations in relevant countries.

Countries have put in place different mechanisms to ensure horizontal co-ordination. At both ends of the spectrum, inter-ministerial co-ordination is nevertheless a key factor to ensure buy-in and alignment towards global commitments. For instance in France, the Secrétariat Général des Affaires Européennes situated in the Prime Minister’s Office leads inter-ministerial co-ordination to guarantee coherence and unity of French positions at the European Union (SGAE, 2022[19]). Countries in which ministries have more autonomy to shape national positions require increased capacity to engage globally at the ministry level. In some other countries, there are clear mechanisms under the leadership of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Co-ordination for multilateral affairs

In Belgium, international position-finding is done through the intra-federal Multilateral Coordination body COORMULTI located within the Federal Public Service for Foreign Affairs. Political and administrative representatives of the federal state, regions and communities – and often also representatives of civil society – are grouped to decide by consensus on the Belgian position abroad. A dedicated co-ordination body grouping the same actors also exists for European Affairs called the Direction-general European Affairs (DGE).

The United States Department of State has set up the “Project Horizon” as a platform for cross-agency collaboration towards tackling a global challenge. Project Horizon brings together senior executives from seventeen agencies and the National Security Council with responsibilities on various aspects of global issues to conduct interagency strategic planning using scenario-based activities.

Vertical co-ordination is key to ensure that a country can successfully tackle transboundary challenges and align international priorities and commitments on global issues across levels of government – regional, sub-regional, local. The implementation of the 2030 Agenda offers a good example, as 65% of the 169 targets underlying the 17 SDGs will not be reached without proper engagement of, and co-ordination with, local and subnational governments. Often, subnational governments also have to enter in agreements with other cross border subnational authorities to handle matters of mutual interest, such as water basins, cross border flows of workers, etc. Still, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for vertical co-ordination and integration as country-specific circumstances must be taken into account. Some federal governments have developed mechanisms to ensure that sub-national authorities have adequate input in international policy making. For example, Germany follows a modular approach to international policy making to ensure vertical co-ordination with Länder to address global challenges. Depending on the issues at hand, Länder representatives may be consulted on a negotiating position on international issues, participate in negotiations if essential interests are involved, or receive full negotiating powers when proposals affect exclusive legislative powers (Germany Federal Foreign Office, 2022[22]).

Further changes to the machineries of governments to better address global challenges may take additional specific forms according to country priorities. For example, several countries have followed Denmark’s example of establishing a Digital/Tech Ambassador to better prepare for digitalisation and to foster relations with Big Tech at a global scale (Box 3.3). Given their transversal, long-term, and cross-border nature, climate change and environmental threats also offer a good example of a global challenge that may push governments to adapt their institutional mechanisms (see Chapter 4].

Box 3.3. Office of Denmark’s Tech Ambassador

In 2017, Denmark became the first country in the world to elevate technology and digitalisation to a crosscutting foreign and security policy priority through its TechPlomacy initiative.

The initiative is spearheaded by the Office of the Danish Tech Ambassador, established under the authority of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The world’s first Tech Ambassador has a global mandate cutting across foreign and security policy, including cyber, development policy, export and investment promotion, and a range of sector policies, as well as Denmark’s bilateral relations with other countries and in the EU and multilateral fora on these issues.

The Office of the Tech Ambassador is in direct dialogue with the tech companies in order to try and influence the direction of technology and improve government preparedness. In whole, it offers a new mechanism for Denmark to bring home knowledge on fast changing technological developments, while also promoting its interest and safeguarding its values abroad.

3.3.2. Promoting policy coherence

Besides horizontal and vertical institutional co-ordination set-ups, policy coherence is key to ensure that institutional and organisational mechanisms align towards common objectives. Policy coherence to address global challenges is typically understood as the alignment of subnational, sectoral and whole of government objectives with the global agenda. The Recommendation of the Council on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (OECD, 2010[14]) offers guidance to support countries in implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognising that there is no one-size-fits-all approach for ensuring efficient co-ordination conducive to improving policy coherence.

Achieving policy coherence to address global challenges may call for reforms in government structures and public service capacities. Most political and economic institutions at all levels of government have been designed to meet sectoral goals and are as a consequence “sticky” by design and resistant to change (Kapstein, 2006[24]). Achieving policy coherence to tackle global challenges may require governments to harness an enabling environment to minimise resistance and facilitate cultural change. Developing the appropriate skill sets and competencies of civil servants is part of this challenge (see following section).

Against this background, decision makers should seize momentum for policy action (OECD, forthcoming[25]). Certain high-level events or crisis may provide a window of opportunity for governments to pass more ambitious legislation on complex global topics, such as climate. For example, in Switzerland “successful” international climate conferences were shown to have an impact on ideological cohesion at the domestic level.

Policy coherence efforts to tackle global challenges should also involve the legislative branch. In certain countries, the legislative can play a key role influencing international commitments through its oversight and control function on foreign policy issues. For example, in the United States - where congress has robust mandate in international affairs - consultation, co-ordination and co-operation between the executive and legislative are key (Bajtay, 2015[26]). Conversely, in countries such as France where the executive has more autonomy in foreign policy matters, co-ordination between the legislature and the executive appears to be less of a factor in the success of foreign policy (Bajtay, 2015[26]).

3.3.3. Strengthening skills in government to think in global terms

Governments need to build capacity in public workforce to address global challenges across a range of line ministries and public institutions. The complex and technical nature of many global challenges require public servants to be able to manage fast-shifting, complex policy priorities while having a global mind-set. They need to be able to leverage their sector-specific expertise and work together with peers on the international stage. Governments need to invest in the talent management and global skills of the national civil service workforce, beyond classic diplomatic skills, to play a meaningful role on these issues.

Developing these global competencies in the public service requires first identifying what they are, deciding how they should be allocated, and developing them through relevant talent management tools and programmes. These include innovative learning and development programmes, as well as recruitment processes.

Global competencies are one of the key skillsets required in a forward-looking, flexible and fulfilling public service (OECD, 2021[27]). Relevant skills might include anticipation and risk management, to prepare for, and address the domestic impacts of global challenges. Furthermore, the complex and technical nature of many global challenges raise questions about whether public servants have access to the necessary trustworthy expertise. Engaging with key stakeholders and having an understanding of how to use expertise and evidence to influence on the international stage is therefore another key skill set. This also includes skills to understand and partner with other governments, international private sector entities, and citizens. The OECD’s skills frameworks on Public Service Leadership (OECD, 2021[27]), Skills for a High Performing Civil Service (Gerson, 2020[28]), Core Innovation Skills (OECD, 2017[29]), as well as the skills for evidence informed policy making (OECD, 2021[27]), can all contribute to global competence in various ways.

Yet, despite the perceived importance of global competencies, to date, few governments have outlined what that skill-set should be. Recent OECD work on cross-border innovation finds limited efforts geared towards instilling skills and capacities for cross-border collaboration and suggests that additional efforts are needed to connect innovation skills with other key cross-border capacities. The United Kingdom’s public service is one of the few that has taken steps to outline the global competencies that all of its policy professionals should aspire to develop (Box 3.4).

Box 3.4. The UK Policy Profession Standards

Published in November 2021, the Policy Profession Standards set out expectations for public sector officials in 12 areas, including “working internationally”. The specific skills and knowledge in this section include:

Understanding the international context and the priorities and interests of all parts of the United Kingdom.

Work within complex contexts to build relationships, influence and negotiate to advance UK interests.

Work effectively with international bodies (multilateral).

Understand the role of international development work.

Understand international trade implications for policy areas.

This list includes a range of technical, social and behavioural skills and competencies required for effectively managing global issues. For example, the first bullet suggests the need for public servants to be highly aware of the interlinkages between their policy area and international dynamics, and to work through global networks to achieve their policy objectives. The second bullet raises issues of cross-cultural communication and the ability to take global and local context and sensitives into international policy development. It requires policy professionals to work with ambiguity, uncertainty and contrasting perspectives and to use international networks to build alliances and influence key actors. The third suggests the need to combine subject matter expertise with a mapping of key actors in multilateral systems and associated decision-making processes. The last two bullets may require specific technical economic and legal competence to understand and use development and trade policy to achieve other local and/or global policy objectives.

Source: (Policy Profession, 2021[30])

Once identified, these competencies need to be developed and managed through appropriate talent and career management mechanisms. Traditionally, in many governments, civil servants who excel in international skills tend to work in the ministry of foreign affairs and are managed in a separate Foreign Service system. However, global agendas also require significant technical sectoral expertise, for example on environmental matters. Conversely, there is also a need for civil servants working in specific policy areas in line ministries to be equipped with at least a minimum level of soft international skills. This raises the question of whether there are other ways of structuring careers in the public service so that international experience and expertise is accessible to a greater number of employees in ways that are relevant to their expertise.

Mobility is one possibility, which can be across ministries at the domestic level, for example between foreign affairs and line ministries, or between national governments and international organisations. Besides this, international mobility, whereby public servants spend time working in the public services of other countries, can be one way of enabling global competencies for all public sector officials. This has been practiced in some European countries, such as France, Germany or the United Kingdom. This could be encouraged through various means, and is apparently an area that few OECD countries use to its full potential.

Some recent initiatives are worth noting. A recent meeting of Ministers of Public Administration under the 2021 Portuguese Presidency supported the idea to encourage civil servants to undertake “exchanges” to develop global competencies, and also to work collectively on cross-border initiatives. The programme would allow for middle managers from EU public services to take part in a leadership development exchange programme in other EU central/federal government administrations. Stated objectives are to promote mutual learning and cross-border co-operation, improve networking, develop a more internationally-competent senior leadership cadre and foster a culture of European-oriented public service. The first phase of this pilot project involves 12 participants from Belgium, France, Portugal and the European Commission.

Promoting international mobility in the public service is not only about creating the opportunities, but also in getting the incentives right for employees to take advantage of them. In many cases, mobility programmes are under-utilised due to their perceived complexity, and the perceived value of them in the context of career development. Often, civil servants complain that the skills they developed while on secondment are not recognised, valued or used when they return. To make this kind of mobility work requires establishing mechanisms that reward investments in these skills. In the Netherlands, for example, mobility experiences are a prerequisite to advance to senior levels of the administration, and international experience is one of the recognised forms of mobility. This is a concrete way of promoting and valuing international experience, as well as ensuring that senior level public servants have international competences to draw on.

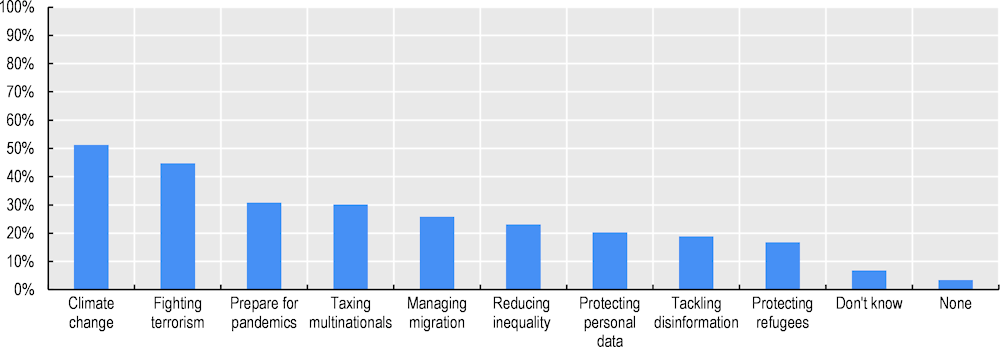

Learning and development, such as training offered by schools of government, can also represent a useful means for promoting international skills. However, according to a recent survey, specific training in global competencies is not currently offered in a majority of schools although it is a topic that many schools are developing (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Curricula offered by Schools of Government, current and planned 2021

Talent attraction and retention is also a key channel to increase the global competencies of public servants. This begins with the way jobs are promoted and marketed to prospective candidates: jobs should include some indication of these skills, so as to attract candidates with relevant experience and/or interest and mind-set. This can also be a way to attract younger generations to public service jobs, particularly those who are motivated by contributing to global issues, and looking for dynamic positions with the potential for a broader range of experience and career paths.

Hiring and retaining a more diverse set of public servants can also improve the global competence of the public service. Many countries may limit access to public service positions to citizens, and there may be other less visible barriers for entry to candidates whose family origins may extend beyond national borders. Promoting diversity as an important public employment policy objective, and ensuring that hiring and management practices are aligned with diversity and inclusion best practices, can contribute to a more globally competent public service. This can be very important for translation and security services, and also to ensure that democracies keep the capacity to fully grasp the actions of the full range of relevant international actors.

3.4. Leveraging governance tools and innovation to enhance capacity for global action

Global challenges also create opportunities for governments to revisit and upgrade public governance tools. This includes unlocking public budgets and public procurement and revamping rulemaking through international regulatory co-operation (IRC) and better regulation tools to address cross-border challenges. Thinking in global terms when investing in digital technologies and data, and promoting innovative thinking in government to go global are other important enablers to better anticipate and prepare for global challenges. This section discusses the scope for adjusting and upgrading governance tools to tackle global challenges more effectively. Grounded in the democratic values of transparency and accountability, the mobilisation of these tools can make a difference in solving global problems.

3.4.1. Spending resources better to deliver on global priorities

Public budgeting is the tool through which governments set out how they will prioritise and achieve annual and multi-annual policy objectives. Together with tax policy, budgeting tools provide a range of opportunities to prioritise expenditure in order to meet national and global well-defined priorities, such as climate change, or resilient and prepared health systems to future emergencies. In the case of some global agendas, such as the SDGs that touch on many aspects of expenditure, the budget provides an integrated governance tool, with specific tagging or targeting of expenditure in a coherent way.

Countries are increasingly mainstreaming long-term global considerations into their budgeting tools:

Green budgeting provides a key example of how governments use budgets as a powerful tool for aligning expenditure with broader national and international commitments and agendas. “Green budgeting” refers to the use of budgetary policy making tools to give policy makers a clearer understanding of the environmental and climate impacts of budgeting choices and help them achieve climate and environmental goals. These practices are becoming increasingly more common across OECD countries and show a path forward for countries to mainstream long-term global considerations into their budgeting tools (see Chapter 4 for a full discussion on green budgeting).

Budgeting can also be used as a tool in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through explicit and measurable presentation of SDG targets in budget allocations and reporting. The OECD works with countries to help integrate processes that ensure the SDGs are considered in the prioritisation and allocation of public resources.

Integrated budgeting approaches can also support health-related investments to reduce global risks for pandemics or other health emergencies to ensure the resilience of health systems in the future, following the gaps highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.4.2. Leveraging strategic public procurement

Strategic public procurement can ensure that procurement not only delivers goods and services to accomplish governments’ missions in a timely, economical and efficient manner, but also serves as a tool to respond to global challenges (OECD, 2020[32]). Public procurement often remains underrated, and yet can represent a very powerful tool, as it accounts for 12% of GDP and 29% of total government expenditure (OECD, 2021[1]).

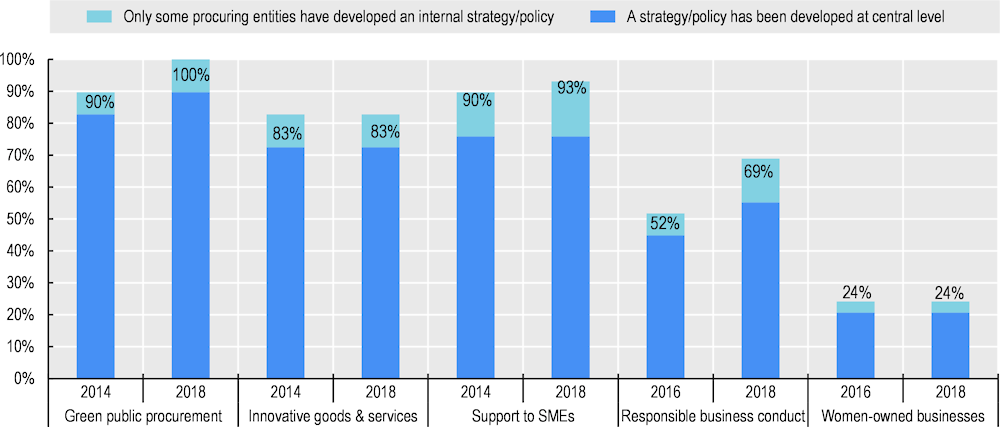

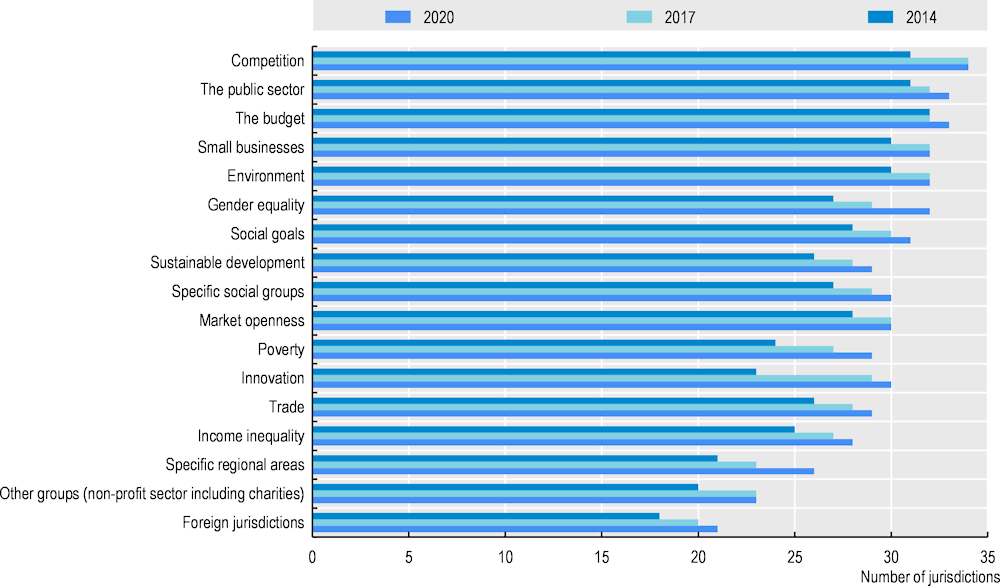

OECD countries are steadily progressing in their use of public procurement to achieve key strategic policy objectives, many of which have a global dimension. This includes, for instance, improving health outcomes, tackling climate change, and promoting socially responsible suppliers into the global value chain (Figure 3.3) (OECD, 2019[33]). (See Chapter 4 for a full discussion on green public procurement).

Figure 3.3. Pursuing strategic policy objectives in public procurement

Note: The chart is based on data from 29 countries that answered both the 2018 and one of the 2016/2014 Surveys on public procurement. Percentages give the sum of both categories. Countries indicating that some procuring entities developed an internal strategy/policy and that a strategy/policy has been developed at central level are included in the second category (i.e. a strategy/policy has been developed at central level).

Sources: (OECD, 2016[34]); (OECD, 2018[35])

The impact of strategic public procurement can be amplified through global value chains, with cross border implications. Through public procurement, governments can influence supplier standards by obliging businesses to incorporate responsible business conduct (RBC) considerations as a requirement to apply for public contracts (OECD, forthcoming[36]). Such standards can relate to respect of human and labour rights, promoting inclusion and diversity, and preventing environmental damage, among other. Countries are gradually developing responsible public procurement frameworks that account for environmental and social considerations and setting up mechanisms to ensure that these requirements extend to subcontractors and other supply chain actors (OECD, 2020[32]; OECD, 2021[37]).

Co-ordinated and collaborative approaches at the national and supranational levels can also promote multiplier effects on the purchasing power of individual governments. Joint procurement efforts can help generate demand for sustainable products and services and create shared incentives to develop innovative solutions to global challenges. For example, as part of the Greening Government Initiative (The United States and Canada, 2021[38]), governments are seeking to use their collective purchasing power to stimulate market innovation by joining forces to issue a common Request for Information on green vehicles. The Circular and Fair ICT Pact (CFIT), led by the Netherlands, illustrates how an international procurement-led partnership can build international bridges and support local outcomes through circular procurement. The CFIT promotes circularity, fairness and sustainability in the ICT sector by applying shared global ambitions in local tenders and by promoting the use of common, easy-to-use procurement criteria. Countries can leverage national procurement initiatives to support such international co-operation in this area. This demonstrates the scale and influence of public procurement when it is driven with strategic objectives.

More agile and co-ordinated public procurement can also help strengthen resilience to global shocks and challenges. The response to COVID-19 showed that collaborative approaches were key to strengthen countries’ responsiveness for purchasing essential goods regional. Mechanisms included bilateral standardisation of procurement procedures, joint procurement agreements and lending agreements for essential goods. Cross-border sharing of information on risk-management intelligence, availability of essential goods, prices, market research and contacts and brokers, can serve to inform procurement strategies and to smooth over global supply chain disruptions (OECD, 2020[39]).

Beyond ensuring economic efficiency, strategic public procurement can support a stakeholder economy which reconciles competing interests from various stakeholders (Ramirez, McGinley and Churchhouse, 2020[40]). For example, in relation to climate adaptation, the Danish strategy to engage in a broad renovation programme of public housing is an example of the combination of short-term impacts that create jobs and economic activity while also ensuring that retrofits include aspects such as insulation and energy efficiency on the construction industry. Looking forward, strategic procurement can help to build trust that all businesses can benefit from an integrated economy by engaging with SMEs to help promote access and further private sector innovation for global goals.

3.4.3. Revamping rulemaking to address global challenges through international regulatory co-operation

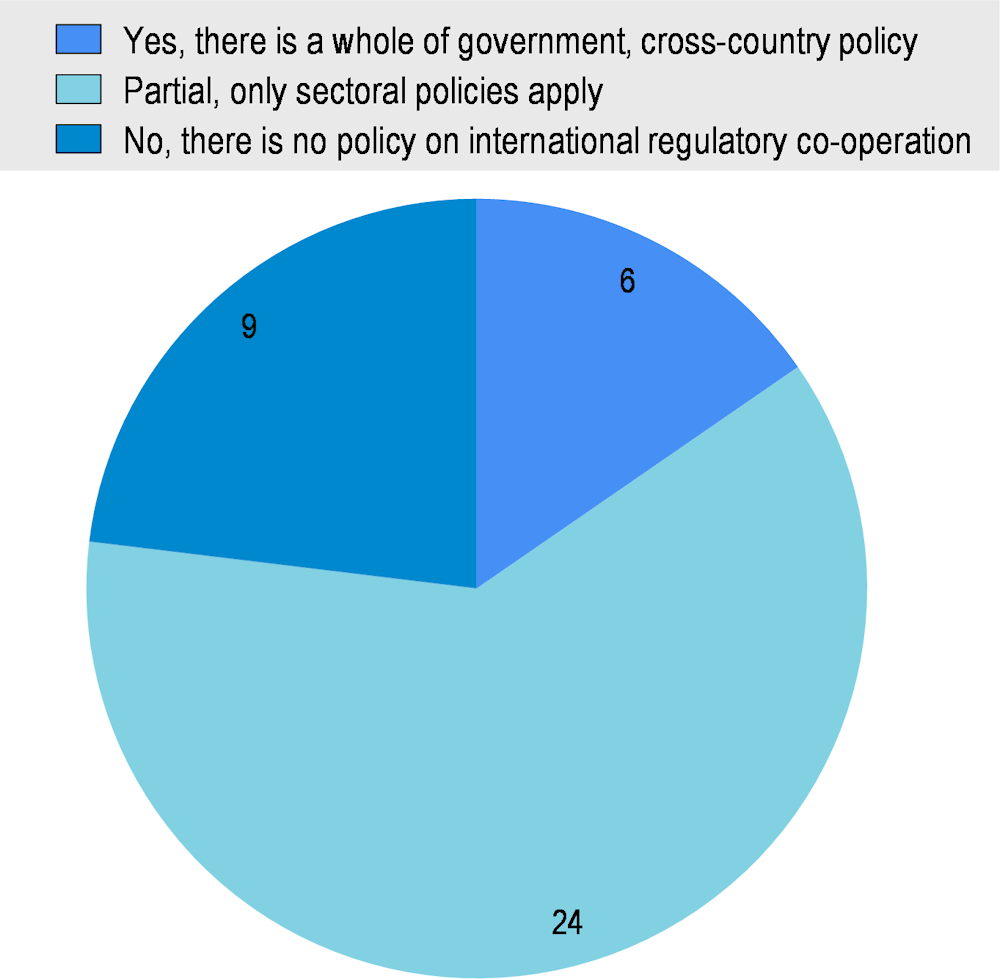

Despite the increasing need to deliver better on public policy objectives that require global action, domestic rulemaking is still constrained by rigid administrative and jurisdictional boundaries. An inward-looking approach to rulemaking can significantly impair the effectiveness of regulations – particularly for rules aimed at addressing transboundary challenges. Currently, only 13% of OECD members have a systematic, whole of governance approach to international regulatory co-operation (IRC) (Figure 3.4) and the institutional arrangement for oversight of IRC remains fragmented across government authorities. Only four countries report their IRC agenda to be attributed to a single authority (OECD, 2021[41]).

Figure 3.4. A large majority of OECD members do not have an explicit, whole of government, legal basis on international regulatory co-operation (IRC)

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

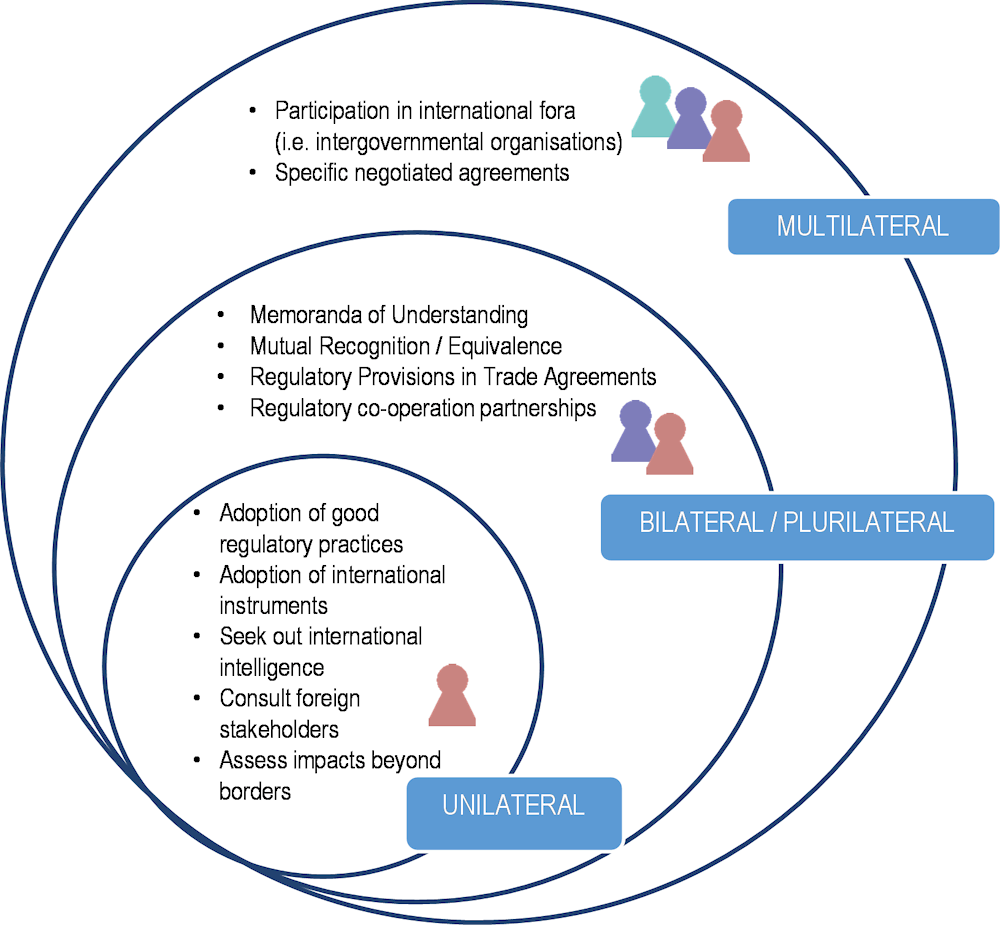

To be effective in the face of global challenges, laws, rules and regulations need to be better connected and co-ordinated across borders – IRC is critical for this. IRC covers any agreement or organisational arrangement, formal or informal, between countries to promote some form of co-operation in the design, monitoring, enforcement, or ex post management of regulation. It offers a variety of approaches that countries can use to promote the interoperability of legal and regulatory frameworks (see Figure 3.5). Rather than telling governments what policies to adopt, IRC empowers governments to decide on their strategic priorities while guiding them on how to best achieve their policy goals. In practice, IRC requires governments to rethink their traditional regulatory policy tools to support the needs of their citizens and business and to better manage global commons.

Figure 3.5. Approaches to international regulatory co-operation

Source: OECD (2021[42]), International Regulatory Co-operation, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5b28b589-en

Regulatory co-operation can increase regulatory effectiveness and result in economic and administrative efficiency. This has been noticeable in the area of tax, where businesses operating globally were able to exploit gaps and mismatches between different countries’ tax systems – or “forum shop” to base their activity in countries with the least costly tax system. This “base erosion and profit shifting” was estimated to cost governments USD 100-240 billion in lost revenues annually – the equivalent to 4-10% of the global corporate income tax revenue (OECD, 2021[43]). These costs are now being addressed by preventing such forum shopping thanks to more than 2 700 bilateral agreements in tax matters and the collaborative work of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting including 141 countries and jurisdictions.

Public services in the digital space in particular require regulatory co-operation if they are to go global. Data governance, for example, needs to be addressed in global terms by agreeing on standards to ensure interoperability, sharing and re-use of data. This implies establishing common mechanisms for cross-sector and cross-border data sharing. The goal is not only to promote accessible and high data quality, but also to promote shared approaches to user experiences. The 2021 OECD Recommendation on Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data (OECD, 2021[44]) offers a set of principles and policy guidance to standardise national approaches to cross-sector and cross-border data sharing. The European Union has also adopted several Directives, Implementing Acts, and recommendations with the aim to promote a consistent approach to data management across countries.2

Trustworthy and portable digital identity is a concrete example of a digital tool that will be decisive for cross-border public service provision. The economic, social and environmental opportunities of achieving genuine portability across platforms and borders are considerable, as seen with the EU Digital COVID Certificate. However, these opportunities introduce challenges for countries to govern digital identity. Whilst countries are rightfully prioritising the development of national digital identity, the implementation of cross-border portability is still at a nascent stage (Table 3.1). As reported in the G20 Collection of Digital Identity Practices, only four G20 countries had implemented cross-border portability in 2021. Greater regulatory co-operation will be required.

Table 3.1. Portability of digital identity

|

|

Cross-platform |

Cross-sectoral |

Cross-border |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Argentina (Sistema de Identidad Digital) |

X |

||

|

Australia (myGOV identity platform) |

X |

||

|

Brazil (GOV.BR identity platform) |

X |

||

|

Germany (German Citizen ID card; Electronic residence permit for non-citizens of EU/EEA area; eID for EU citizens) |

X |

X |

X |

|

Italy (Public Sector Digital Identity System, Electronic ID Card, National Services Card) |

X |

X |

X |

|

Saudi Arabia (Digital ID via Tawakkalna and Absher apps) |

X |

X |

X |

|

Singapore (Singpass and Corppass) |

X |

X |

|

|

Spain (Electronic National Identity Document) |

X |

X |

|

|

Türkiye (e-Government Gateway identity platform |

X |

||

|

United Kingdom (GOV.UK Verify) |

X |

Note: Information was gathered through the G20 Digital Identity Survey and desk research to inform the discussions of the G20 Digital Economy Taskforce in 2021, under the Italian G20 Presidency.

Source: OECD/G20 (2021) “G20 Collection of Digital Identity Practices”.

The new OECD Recommendation on International Regulatory Co-operation to Tackle Global Challenges (OECD, 2022[45]) supports policy makers and regulators in adapting their domestic regulatory frameworks to the international environment and increase their resilience to future crises. It focuses on three pillars: building a whole-of-government approach to international co-operation, considering an international lens in domestic rulemaking, and ensuring bilateral, international, and multilateral regulatory co-operation.

For regulators to more systematically consider international instruments3 in their rulemaking activities, these instruments need to be of high quality, widely and easily accessible, and fit to serve the public interest. OECD evidence highlights the complexity of international rulemaking, which encompasses a landscape of “over 70 000 international instruments” (OECD, 2021[46]). Ensuring the quality and effectiveness of international instruments is key to successfully address global challenges. International Organisations (IOs) provide a permanent framework for IRC as platforms for sharing data and experiences; as well as consensus-building and the adoption of common approaches (OECD, 2021[46]). Governments can leverage on IOs to strengthen action for global challenges, for example, through specific co-ordination to address complex and multi-sectoral issues (e.g. One Health, bringing together FAO, WHO, OIE, and UNEP) or calling for more innovative forms of public-private multi-stakeholder partnership (e.g. Covax). The IO Partnership for effective international rulemaking (OECD, n.d.[47]) can help governments in scanning the existing landscape and identifying the most relevant and effective collaboration opportunities.

Regulators can also revamp traditional regulatory governance tools to promote an international lens in domestic rulemaking. For instance, reflecting green impacts in regulatory impact assessment (RIA) is a useful approach to ensure that due consideration is given to the impact of any new regulation to achieving domestic or international environmental commitments. While all OECD members consider environmental impacts in RIAs (Figure 3.6), much fewer Members systematically require environmental impacts of their regulations on foreign jurisdictions to be considered (OECD, 2021[41]).

Figure 3.6. OECD regulators are assessing regulatory impacts on increasing number of factors, but still rarely consider impacts on foreign jurisdictions

Note: Data are based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG) Surveys 2014, 2017 and 2021.

3.4.4. Promoting innovative thinking in government towards global action

Innovative tools such as international collaboration in policy experimentation, mission-oriented innovation and ground-up intelligence techniques can support governments in tackling cross-border issues. Using innovation to address global challenges requires “opening up bureaucracies” in processes of creating problem solving. The goal is to counter established practices and cognitive and normative underpinnings, triggering transformative learning processes while building joint ownership over new and bold solutions. At the same, continuous iteration and testing new ideas and solutions in agile ways can help promote learning and rapid delivery while keeping risk levels manageable. Still these approaches are often hampered in the public sector by a series of factor including:

Undeveloped or poorly understood cross-border ecosystems.

Culture resistance to open and non-linear activities and processes.

A lack of feedback and learning loops for testing new ideas.

Absence of a cross-border facilitator to build relationships and drive progress.

3.4.5. International collaboration in policy experimentation

Experimentation can help design, test, and evaluate policy outcomes. The capacity for co-ordinated multilateral experimentation is crucial for broadening the understanding of the conditions of success of a given policy to tackle a global challenge. Therefore, there is a need to conduct experimentation across borders and jurisdictions to tackle global issues such as climate change.

The use of cross-border experimentation has benefited from a growing international community on Behavioural Insights (BI), which can mobilise useful approaches to design and scale successful policy solutions. The OECD is supporting such cross border efforts through its Online Behavioural Insights tool, which includes an Interactive BI Unit Map; featuring units across 43 countries, an International Project Repository, including more than 100 BI projects, and a Pre-registration Portal to allow BI practitioners to actively engage in knowledge-sharing and scientific rigour by sharing pre-analysis plans with the behavioural science community at the early stages of BI experimentation and policy testing. Through collaboration and co-production, BI experts working together from different countries are able to generate unique insights to address complex policy issues, including global challenges. A recent example includes work with Canada using BI to help broaden policy makers’ knowledge of citizens’ acceptance and engagement with green policies, equipping decision makers to evaluate and assess the effectiveness of active or proposed green policies, and providing empirical evidence to better anticipate and prepare for future challenges surrounding (see Chapter 4).

3.4.6. Mission-oriented innovation

Mission-oriented innovation is also a promising tool which can help solve the wicked challenges facing governments today, such as achieving ambitious climate goals. Mission-oriented innovation involves a systemic approach including policy and regulatory measures mobilising science, technology and innovation. These measures span different stages of the innovation cycle from research to demonstration and market deployment, mix supply-push and demand-pull instruments, and cut across policy fields and disciplines” (Larrue, 2021[48]). Using mission-oriented innovation implies framing global societal challenges through measurable, ambitious and time-bound targets, such as achieving carbon-neutrality by 2030. Then, the public sector takes an active role in convening and co-ordinating actors and resources around the complex, cross-sectoral, and cross-national issues that cannot be solved by individual actors alone. A survey from the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation conducted in 2022 shows that mission-oriented innovation can help address the lack of consensus between different political parties by focussing efforts towards a shared goal (OECD/Danish Design Centre, 2022[49]).

Mission-oriented innovation has been tried in various fields that touch upon global challenges, such as health, technology, and environment. The European Commission has adopted the mission-oriented innovation framework in five areas: Adaptation to Climate Change including Societal Transformation; Cancer; Healthy Oceans, Seas, Coastal and inland Waters; Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities; Soil health and Food. National governments have also adopted such approaches, for example the mission-driven green research and innovation partnerships launched by the Innovation Fund Denmark. Missions present an opportunity for the public sector to focus attention and resources on the key issues of our time and in doing so to address the challenges that are critical to the well-being of citizens in a frontal manner. However, as an emerging field, there is a need for identifying the capabilities required to deliver mission-oriented innovation, for putting in place appropriate accountability and evaluation mechanisms, and setting-up long-term governance frameworks for missions with targets set for 2030 or 2050. This is currently supported by the OECD Mission Action Lab (Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. Supporting governments to tackle mission-oriented innovation through multidisciplinary approaches through the OECD Mission Action Lab

The OECD Mission Action Lab established in 2021, focuses on supporting governments with the implementation challenges of missions to enable mission oriented innovation. The Lab concentrates specifically around governance of missions, managing a portfolio of innovations related to the mission, and evaluation of missions. In co-ordination with research partners, the Lab supports the following elements:

Development of diagnostic tools and methods for assessing the needs and framework conditions related to the adoption of mission-oriented innovation approach as well as practical tools and methods based on applied learning.

Sharing of good practices regarding mission implementation (e.g. project portfolio approach, blended funding, monitoring, systemic evaluation, bundling of supply and demand side policy instruments, etc.).

Design of governance mechanisms for mission-oriented innovation across a variety of settings, including from national, sub-national and cross-border perspectives.

Analysis and testing of suitable mechanisms to include stakeholders, especially groups that traditionally do not engage with government-led initiatives.

Development of specific tools to steer mission-oriented innovation portfolios and ecosystems as well as monitoring and evaluation of missions.

Source: This reflects a joint effort of the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, the Science, Technology, and Innovation Directorate, and the Development Co-operation Directorate at the OECD.

3.4.7. Protecting global action from undue influence

Global actions led by democracies to promote international co-operation to address major challenges can also be vulnerable to undue influence, whether from major private interest or from foreign actors. A wide range of economic sectors and industries may have stakes in the outcome of global policy debates and negotiations.

At the same time, engaging with public decision makers is also crucial for businesses, trade associations, unions, and other group of interests affected by related regulations or other forms of public decisions to tackle global challenges. In general public decision makers can make use of a wide range of approaches for stakeholder consultations, from parliamentary hearings, to the appointment of ad hoc bodies and expert groups, or scheduled appointments with political leaders, so that interest groups can exercise their influence and raise their points. The specificity of addressing global challenges lies in the fact that a significant share of these stakeholders may be foreign or global entities, or with particularly high stakes at play, for example the tech companies in the case of the digital transformation. Therefore, it is crucial to also address the risk of undue influence in order to effectively address global challenges.

Increasing evidence shows that the abuse of lobbying and other influence practices can block domestic progress on the implementation of global policies. For example, in relation to climate change, an analysis of a major oil and gas company’s internal documents and communications between 1977 and 2014 found that, while its own research had established that climate change was caused by human activity, the company engaged in various practices, notably publishing opinion pieces in newspapers, to raise doubt, influence public opinion and reduce regulatory pressures (Oreskes and Conway, 2010[50]; Supran and Oreskes, 2017[51]). In the past, oil and gas companies have been leading contributors to think tanks and front groups questioning established climate science, or funding misleading climate-related branding campaigns or social media advertisements (InfluenceMap, 2019[52]; Graham, Daub and Carroll, 2017[53]). With limited transparency on who is behind such organisations or campaigns, there is a risk of misleading or confusing public opinion.

To ensure greater transparency of the interests that have the potential to lobby in domestic decision making of global relevance, governments can use tools such as those described in the OECD Lobbying Report (OECD, 2021[54]):

Lobbying registers, scaling up disclosure requirements to include information on the objective of lobbying activities, its beneficiaries, the targeted decisions and the types of practices used, including the use of social media as a lobbying tool. For example, in April 2021, the European Union adopted an inter-institutional agreement between the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union, and the European Commission on a mandatory transparency register, making mandatory for interest representatives to register themselves before carrying out certain lobbying activities relating to any of the three signatory institutions. The agreement also covers so-called “indirect” lobbying activities which have been increasingly important during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Making public the agendas of key public officials involved in relevant decision-making processes (e.g. digital, health and environment Ministers).

Mandating ex post disclosures of how legislative or regulatory decisions were made. The information disclosed can include the identity of stakeholders met, public officials involved, the objective and outcome of their meetings, as well as an assessment of how the inputs received were integrated into the final decision.

Expanding corporate political spending disclosure requirement to enhance public scrutiny of corporate engagement in relevant global policy-making processes. For instance, companies concentrated in the fossil fuel and energy-intensive sectors have faced increasing criticism from investors, shareholders and consumers for using climate commitments or sustainability policies as a smoke screen to display a public image of climate responsibility while lobbying to delay or block binding climate policies, or providing donations to candidates who are against strengthening climate-related regulation. In recent years, pressure from investors and leading asset managers to better take into account corporate lobbying and political financing as a risk to the environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance of companies has been a key factor influencing companies’ business strategies. In the area of climate, the number of shareholder proposals concerning corporate political engagement disclosures has increased significantly over the last decade, to become one of the most popular types of shareholder resolutions submitted to a vote (InfluenceMap, 2021[55]; Glass Lewis, 2021[56]). More disclosure on lobbying spending and political contributions – with better transparency on ESG goals and results – would allow investors and other stakeholders to evaluate how, for example, lobbying and political spending activities and sustainability initiatives might have conflicting goals.

Ensuring that the appointment of ad hoc advisory bodies and expert groups is accompanied by adequate transparency and integrity safeguards to ensure the legitimacy of their advice. To meet global goals, governments may rely on special independent advisory bodies and expert groups, such as – in the field of climate change – the High Council on Climate in France, the Climate Change Advisory Council in Ireland and the Committee on Climate Change in the United Kingdom. Depending on their status and mandate, their missions may include providing objective analysis to the Parliament and/or the Government on climate-related risks and analysis. The composition of these bodies may consist solely of researchers or academics, or rely on broader membership (Weaver, Lotjonen and Ollikainen, 2019[57]; Averchenkova, Fankhauser and Finnegan, 2018[58]). Private sector representatives participating in these advisory groups have direct access to policy making without being considered as lobbyists, and may, whether unconsciously or not, favour the interests of their company or industry, which may also increase the potential for conflict of interest. As of 2019, only 47% of OECD countries provided disclosure on participants in advisory groups, leaving considerable room to transparency. To enable public scrutiny, information on a group’s structure, mandate, composition and criteria for selection should be made available online. It is also necessary to adopt rules of procedures for such groups, including terms of appointment, standards of conduct, and most importantly, procedures for preventing and managing conflict of interest (OECD, 2021[54]).

Some autocratic regimes are also actively investing in international organisations and related global governance structures. It is therefore essential to balance undue influence of select actors and autocratic regimes, and the subsequent development of biased policies. While a number of international organisations4 have initiated action in this area, there is scope for improvement. Countries should therefore promote reforms which can be inspired by good practices and in line with existing standards, including the OECD Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying.

3.5. Building resilience to foreign undue influence

In the globalised world, democracies face a number of challenges. This includes the destabilising impacts of some foreign undue influences on democracy, including from some autocratic regimes.

Some autocratic regimes have the potential to destabilise individual democracies in OECD countries on three main levels. First, they can exploit loopholes to spur dis-information campaigns, distribute malign political financing, and provoke foreign interference in domestic policy making.5 Second, democracies may also be vulnerable to illegal and illicit activities, such as corruption and illicit trade. Third, the global action of democracies to address major challenges can also suffer from undue influence both from foreign actors and powerful private interest through lobbying, as covered in the previous section. Despite the many efforts from the international community, the proceeds of some of these activities tend to creep into democracies’ economies as they often offer safer havens.6 Taken together, these contribute to weakening internal cohesion in democratic societies, inciting perceptions that democracies are dysfunctional, corrupt, and untrustworthy and that they can be easily bought, which can ultimately lead to increased support for non-democratic forms of government (Zelikow et al., 2020[59]).

Maintaining the openness of democracies in a globalised world therefore requires investments in further protecting them from foreign destabilisation of their own model. This means identifying and countering foreign threats and assessing the risks. Strengthening resilience to these risks requires a number of mutually supportive actions, including preventing mis- and dis-information; strengthening integrity and transparency in lobbying and all forms of influence including political financing; strengthening integrity and transparency in the not-for-profit and educational sectors, tackling faulty citizenship-by-investment and residence-by-investment (CBI/RBI) schemes; as well as closing critical gaps in illicit trade, anti-money laundering, beneficial ownership, and tax transparency frameworks through wide ranging multidisciplinary approaches.

3.5.1. Recognising the threats to democracies from autocratic regimes

Evidence concerning the scope and reach of practices used by some autocratic regimes to interfere in the domestic affairs of democracies is mounting. They have used several means to gain influence in democratic countries. Some may be openly and legitimately channelled through their embassies or permanent representatives who engage directly in some of the democratic debates of their host countries. However, many methods and avenues pose a risk to democracies as they operate in the shadow, and are considered “foreign interference” activities, as they concern “covert, deceptive and coercive activities undertaken by (or on behalf of) foreign actors to advance their interests or objectives”.7 In particular, such activities include dis-information campaigns, leveraging loopholes in lobbying and political financing frameworks to interfere in decision- and policy-making processes, efforts to undermine media freedom, and co-opting of civic institutions for various means. These actions can undermine public trust in democracies and can have a transformative impact on domestic and foreign policies, the electoral system, economic interests and national security (OECD, 2021[54]). Some OECD countries are already taking action and their responses can serve as good practice for strengthening democracies resilience to global risks.

Spreading mis- and disinformation

The spread of mis- and disinformation poses a fundamental threat to the free and fact-based exchange of information that forms the bedrock of democratic life (see Chapter 1). While mis- and disinformation is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon, addressed in Pillar 1 of the Reinforcing Democracy Initiative, it can also be affected by the action of some autocratic regimes. Recent events, including the spread of vaccine disinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic, the 6 January 2021 attack on the US Capitol, and Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, underscore how foreign-led false and misleading information can weaken democracies’ ability to set the terms of an evidence-informed and fact-driven democratic debate, to protect their national interests and preserve national security. Such action has the potential to erode confidence in the values of democracy. While the actors spreading mis- and disinformation are numerous, evidence shows that some of the campaigns emerge from autocratic regimes. For example, data published by large online platforms on the origins and targets of campaigns show that the platforms have specifically taken action against campaigns emerging from large autocratic countries (Bradshaw and Howard, 2019[60]). The targets of these campaigns include a growing number of countries, many of whom are democracies: a 2019 report notes an increasing trend in the amount of countries experiencing disinformation campaigns, from 28 in 2017 and 48 in 2018, to 70 in 2019 (Bradshaw and Howard, 2019[60]). In March 2021, the European Union’s EUvsDisinfo project reported that Germany has been the primary target of Russian disinformation campaigns since 2015, with 700 cases of disinformation in reporting targeting Germany, 300 targeting France, 170 for Italy and 40 for Spain (EU Disinfo Lab, 2021[61]).

Some autocratic regimes use a number of tactics to target democracies with false information. For example, they translate false information into French, German and Spanish, thereby enabling them to achieve higher engagement with online articles than with established news sources such as major national news outlets (Oxford Internet Institute Programme on Democracy & Technology, 2020[62]). The targeting of Spanish-speakers particularly in Latin America can be viewed as an attempt to assert geopolitical influence in a region in which it has economic interests, while strengthening polarisation in the process (Philips et al., 2020[63]). Another common tactic is to encourage foreign journalists to pursue discredited theories.