This chapter presents new data on the use of career guidance among adults in Canada, as compared with adults in other OECD countries. It analyses the use of career guidance among different sub-groups of the population, and highlights Canadian and international initiatives to engage greater use of career guidance among under-represented groups. The chapter also covers the reasons why adults seek career guidance in Canada, how usage changed during the COVID‑19 pandemic, and the main barriers to greater participation.

Career Guidance for Adults in Canada

2. Fostering a greater and more inclusive use of career guidance in Canada

Abstract

Summary

According to the OECD Survey of Career Guidance for Adults, Canadian adults use career guidance much less than their counterparts in other countries. This partly reflects a lower likelihood of using career guidance among the employed population in Canada, relative to other countries in the survey. Adults in Canada are particularly less likely to use career guidance when they want to progress in their current job or when choosing an education or training opportunity. In contrast to other countries, Canadian adults who feel their jobs are at risk of automation are also less likely to consult career services than their peers who do not feel their jobs are at risk.

Use of career guidance among adults increased during the COVID‑19 pandemic, particularly among adults who reported that COVID‑19 had an impact on their employment status. This is consistent with the fact that most public career guidance is provided to adults through government-run employment services.

Some groups of Canadian adults use career guidance less than others, particularly low-educated adults, older adults and those living in rural areas. With better outreach and targeting of services to the needs of these groups, career guidance could be an important lever to motivate them to train and to improve employability.

The most common reason that adults provided for not using career services was not feeling the need to, and this is in common with other countries in the survey. This was followed by not being aware that services existed. Unlike other countries, however, Canadian adults were more likely to report that they did not have enough time, due to either work or family/childcare responsibilities.

The previous chapter showed how the COVID‑19 pandemic had a disproportionate employment impact on vulnerable groups in the labour market, including young people, low-skilled workers, women, temporary employees and Indigenous people. These are some of the same individuals who face higher risk of skills obsolescence and job automation due to technological change. Adult learning can facilitate job transitions during periods of economic instability, but earlier evidence suggests that vulnerable adults who are older, lower-skilled or in low-income jobs tend to participate less in adult learning than their counterparts. To the extent that these gaps are due to a lack of knowledge about adult learning opportunities or their benefits, or to low motivation, career guidance can be an important lever to engage greater participation in adult learning among vulnerable adults. It can also support job transitions and improve employability.

This chapter presents survey evidence on the use of career guidance by adults in Canada, barriers to the use of career guidance, and how inclusive the Canadian system is.

2.1. Use of career guidance services

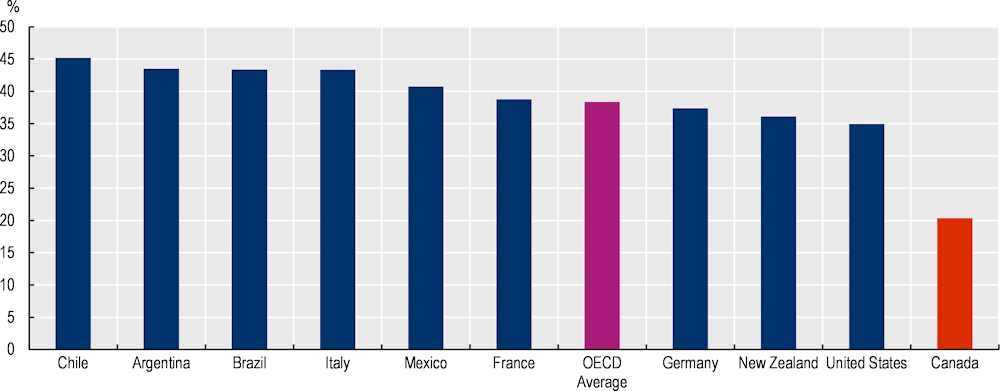

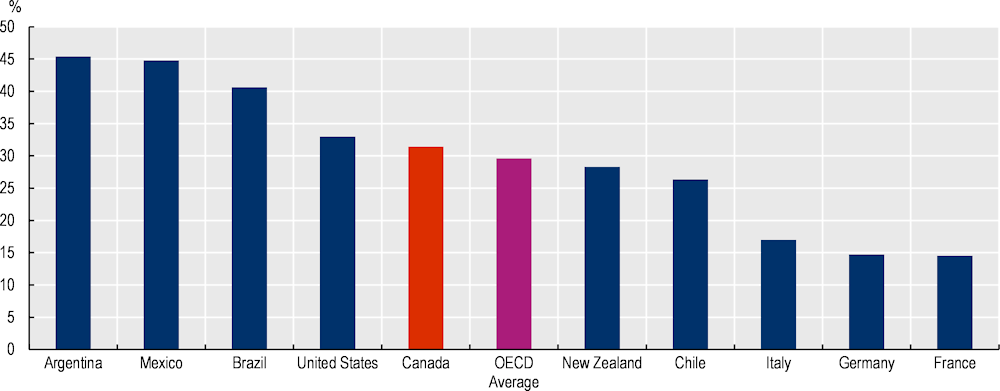

Adults in Canada appear less likely to consult career guidance advisors than adults in other surveyed countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States). According to the SCGA, only 19% of Canadian adults spoke with a career guidance advisor over the past five years. This is nearly half the survey average (39%), and places Canada as the country with the lowest use of adult career guidance services in the survey (Figure 2.1).

While the low use in Canada relative to other countries may be partially due to methodological differences (see Annex B), it is also likely caused by differences in demand and supply factors. On the demand side, adults in Canada are less likely to seek career guidance when they want to progress in their current job or when they are looking for education and training opportunities. This helps to explain why employed adults use career guidance less in Canada (see Figure 2.11 below), which is not the case in other surveyed countries. On the supply side, the survey data does not uncover any glaring issues with the quality of career guidance services in Canada (see Figure 2.8 below). No conclusions could be reached about the adequacy of the supply of career guidance services in Canada based on the survey data.

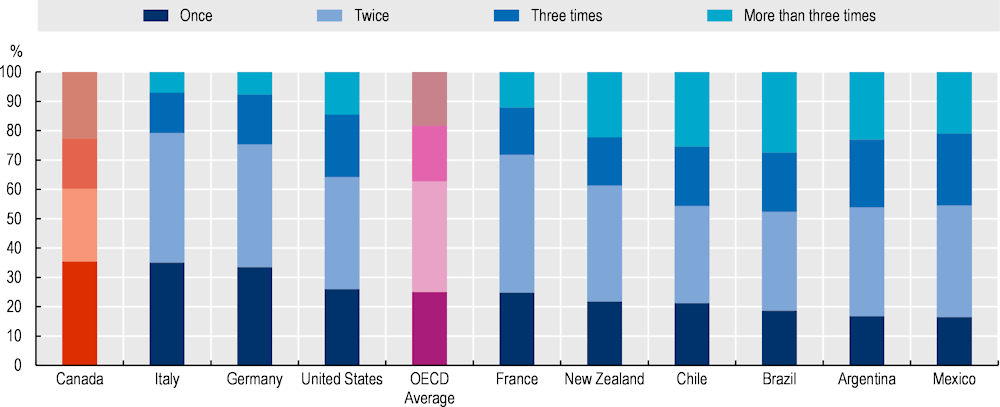

In addition to using career guidance less, Canadian adults are also less likely than those in other countries to have multiple interactions with a career guidance advisor. Thirty-five percent of Canadian adults reported meeting with their career guidance advisor only once, higher than the average of all countries that participated in the SCGA (25%). This represents a relatively high share of adults not having any follow-up after their initial consultation with a career guidance advisor. That said, 65% of Canadian adults do have follow-up, with 25% of adults meeting with a career guidance advisor twice, 17% three times, and 23% more than three times (compared to 38%, 19% and 18% for the survey average, respectively) (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.1. Share of adults who have spoken with a career guidance advisor

Note: The average includes the 10 countries covered by the SCGA: Argentina, Canada, Chile, Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States. In Canada, respondents were asked if they had used a career service in the past five years, while in the other countries respondents were asked if they had spoken with a career guidance advisor over the past five years.

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

Figure 2.2. Intensity of use of career guidance services among adults

Note: The average includes the 10 countries covered by the SCGA: Argentina, Canada, Chile, Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States. In Canada, respondents were asked how many times they used a career service in the last 12 months, while in the other countries respondents were asked how often they interacted with a career guidance advisor over the past 12 months.

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

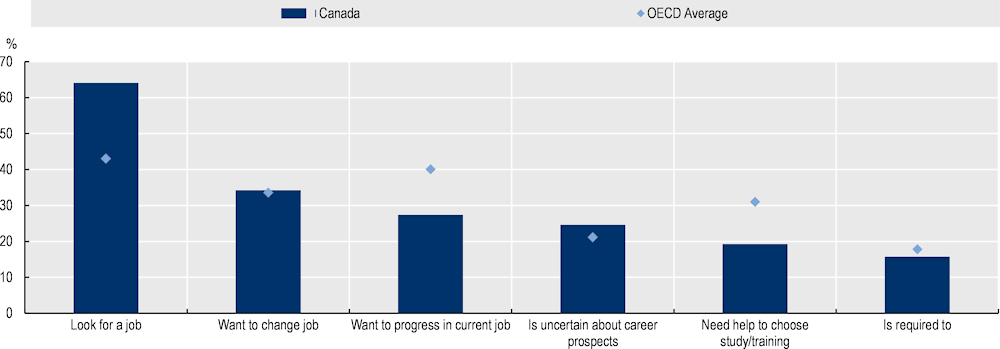

Figure 2.3. Reasons for seeking career services, Canada and OECD average

Note: The average includes the 10 countries covered by the SCGA: Argentina, Canada, Chile, Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States. Respondents could choose more than one answer. Data refers to the last time the respondent spoke to a career guidance advisor / used career services. In Canada, respondents were asked about their reasons for using career services, while in the other countries, respondents were asked about their reasons for speaking to a career guidance advisor.

Source: OECD 2020 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

Canadian adults also have different reasons for using career services compared to adults in other OECD countries (Figure 2.3). The majority of Canadian adult users (64%) consulted career services to find a job, a much higher share than observed on average across countries (43%). Contrary to what one might think, these adults are not all unemployed: in fact, 56% of adults who say they spoke with a career guidance advisor to find a job were employed at the time they received guidance. They were either looking to change jobs or looking for a second or third job. Only 28% were unemployed and 16% were not active in the labour force. Canadian adults are less likely than their international counterparts to seek guidance when they are choosing a study or training programme (19% versus 31%), or when they want to progress in their current job (27% versus 40%).

2.1.1. Adults in Canada use other types of career support less than those in other countries

One possibility for the low rate of career guidance usage in Canada could be that Canadians prefer other types of career support, like consulting career information online, speaking with friends and family, or participating in career development activities like information interviews or work visits. However, a look at the survey data in international comparison suggests that adults in Canada also use these alternative sources of career support less than their international counterparts.

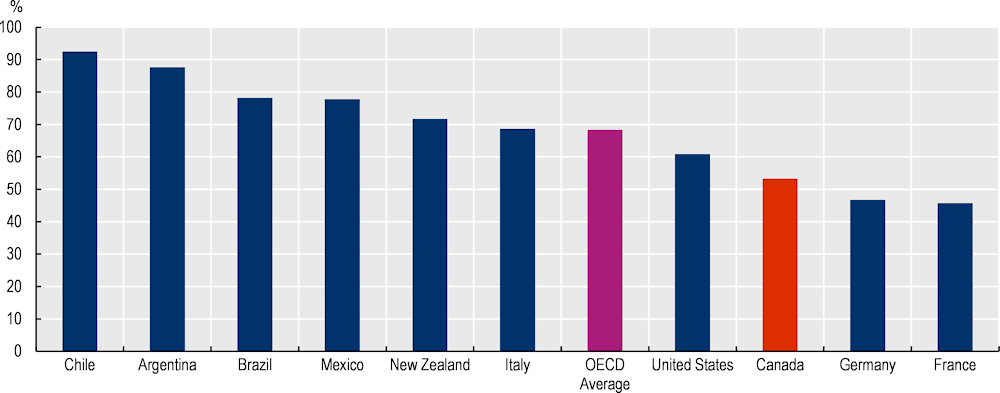

Figure 2.4 shows the use of online information in international comparison. Just over half of Canadian adults (53%) reported that they looked online for employment, education and training opportunities over the past 5 years. This is a lower share than the OECD average (69%). Older adults use online information less than prime‑aged adults (37% versus 58%), which is not surprising given that older adults tend to have lower digital skills and are also less likely to be looking for new jobs. Adults in rural areas also report a lower use of online information compared to adults in urban areas (43% versus 55%); likely related to inferior broadband access in rural versus urban areas in Canada. Finally, there are also gaps in the use of online information by education level: lower-educated adults, too, use online information less than high‑educated adults (48% versus 66%).

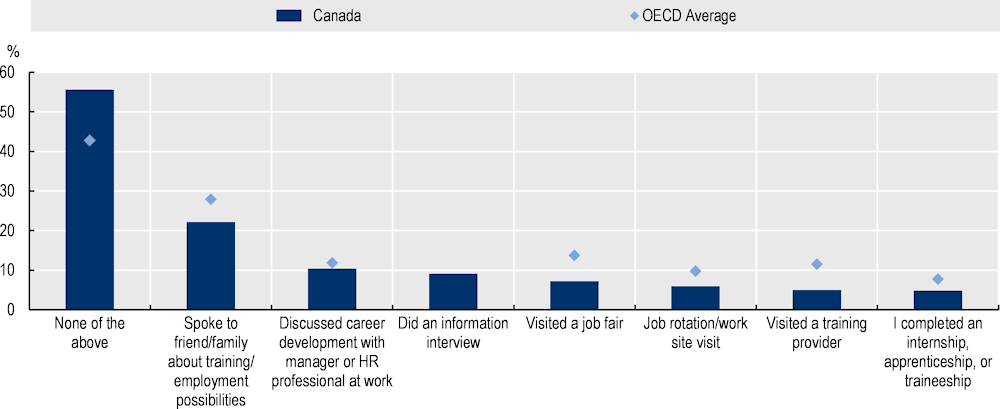

Canadian adults are also less likely than their international counterparts to participate in career development activities (Figure 2.5). Fifty-five (55%) per cent of adults in Canada reported that they had not participated in any type of career development activity in the 12 months preceding the survey. This compares with 42% of adults on average for all countries participating in the SCGA. The most common type of career development activity that Canadian adults did was speak to a family member or friend about training or employment possibilities (22%), followed by discuss career development with a manager or HR professional at work (10%), do an information interview (9%), visit a job fair (7%), and participate in a job rotation/work visit (6%).

Figure 2.4. Use of online information in international comparison

Note: The average includes the 10 countries covered by the SCGA: Argentina, Canada, Chile, Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States.

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

Figure 2.5. Participation in other career development activities, Canada and OECD average

Note: Only the Canadian survey included “did an information interview” as a response option. Average includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States.

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

2.1.2. Adults in Canada increased their use of career guidance during COVID‑19

Evidence from the SCGA suggests that Canadians increased their use of career services during the COVID‑19 crisis, likely in response to the spike in unemployment rates and a reduction in hours worked. Among adults who said they used career guidance over the past five years, the large majority (68%) reported that COVID‑19 had had an impact on their employment. This is a much higher share than reported among non-users of career guidance (39%), and suggests that adults may have sought career guidance during this moment of economic instability to help them to navigate the changing labour market.

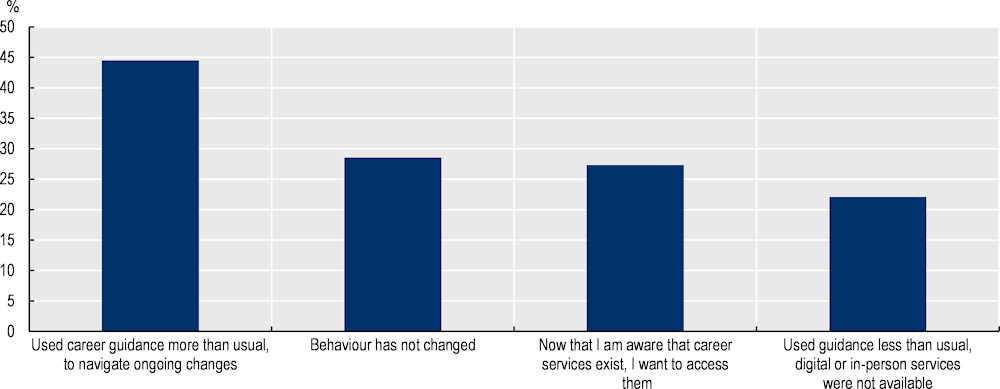

Adults who reported that COVID‑19 had an impact on their employment were also more likely to expect to use career guidance as much or more in the next 12 months. According to survey results, 44% of adults reported using career services more often than before the pandemic to navigate ongoing changes in the labour market (Figure 2.6). Only 22% said that they used career services less because digital or in-person services were less available.

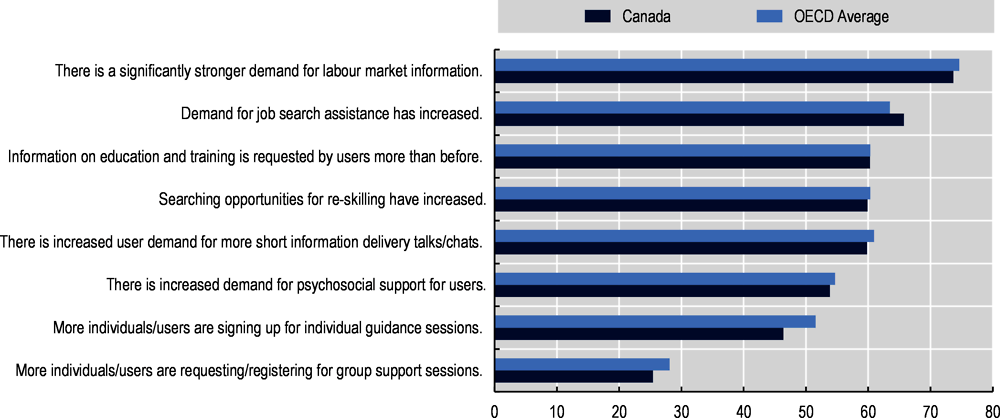

The rise in use of career services during the pandemic is corroborated by an international survey of career development practitioners that included Canada (Figure 2.7). Over half of career development practitioners observed a higher demand for career services during the pandemic, and specifically demand for labour market information, job search assistance, short information delivery chats, requests for information on education and training and psychosocial support.

Figure 2.6. Change in the use of career guidance services during COVID‑19, Canada

Note: Respondents could choose more than one answer.

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

Figure 2.7. Reported increase in demand for career guidance during the pandemic, Canada and OECD average

Note: Respondents are mainly career guidance advisors, but also include managers of guidance services, representatives of professional associations or policy officials across Canada. Due to limited sample size in some countries, the OECD average shown here is not an average of individual country averages, but the average of all survey responses in OECD countries. The number of responses per country varies.

Source: Cedefop, European Commission, ETF, ICCDPP, ILO, OECD and UNESCO (2020[1]), Career Guidance Policy and Practice in the Pandemic. Results of a Joint International Survey, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/318103. Based on author’s own calculations.

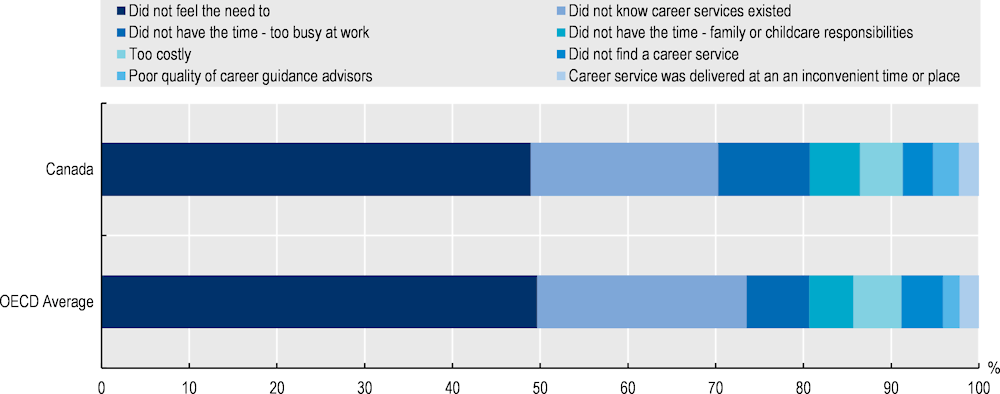

2.1.3. Barriers to accessing career guidance services include not feeling the need to, and not being aware

Understanding the reasons why Canadian adults do not use career services could spark thinking about how coverage and inclusion might be improved. The most common reason reported was simply not feeling the need to use career guidance services (49%) (Figure 2.8), a share that is on par with the average in other surveyed countries (50%). These adults may be well positioned in their careers or perhaps they are unconvinced about the benefits of career development. Unemployed adults were more likely to report not feeling a need to use career services than were employed adults (66% versus 51%). This pattern is similar in other countries in the survey, where 62% of unemployed and 44% of employed adults reported not feeling a need to use career services.

Figure 2.8. Reasons for not using career services, Canada and OECD average

Note: The average includes the 10 countries covered by the SCGA: Argentina, Canada, Chile, Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States. Respondents in Canada were asked why they did not use career services, while respondents in the rest of the countries covered by the survey were asked about why they had not spoken to a career guidance advisor.

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

The next most common reason for not using career guidance was not being aware that services existed (21%), followed by not having enough time due to work responsibilities (10%) or family or childcare responsibilities (6%). The share of adults who reported not having enough time as a key barrier was higher in Canada relative to the survey average (16% versus 12%). Relatively few respondents complained that services were too costly (5%), not available (3%), of poor quality (3%), or delivered at an inconvenient time or place (2%).

Raising awareness about career guidance services in Canada and finding ways to make consulting a career guidance advisor more compatible with work and family responsibilities could help to improve take‑up of services by addressing barriers related to lack of awareness and lack of time. National media campaigns, like the 2020 ‘En alles beweegt’ (‘And everything is moving’) campaign in Flanders (Belgium), could help to raise awareness about the availability and value of career guidance services. Another way to raise awareness is through referrals between public services. If existing employment, social and adult education services are well connected, adults are more likely to learn about career guidance opportunities. In Ontario, there are multiple entry points for adults to enter adult education opportunities – such as through Employment Service and Literacy and Basic Skills service providers, school boards, Co‑ordinated Language Assessment and Referral System Centres – and each provides an opportunity to be referred to career guidance.

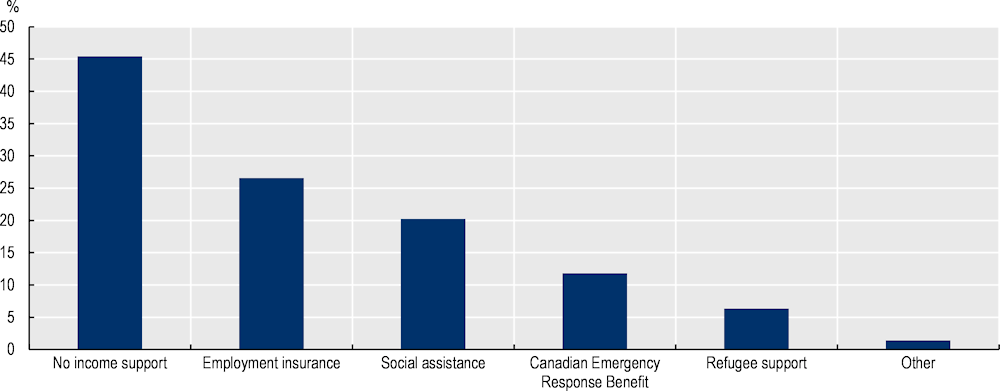

The fact that cost is not a major barrier to accessing career guidance in Canada is positive and substantiated by the high share of adults who receive services for free (Figure 2.9). Less than one‑third (31%) of adults paid out-of-pocket for the career services they received. The remaining 69% reported receiving career services for free. Adults paying out-of-pocket in Canada represent a higher share than in European countries in the survey (France, Germany, Italy), but this share is on par with the overall average across countries in the survey. Subsidised career services are often made available to adults participating in social programs with a labour market integration component. Indeed, some 55% of adults using career services reported receiving additional income from one or more of the following social programs: Employment Insurance (27%), Social Assistance (20%), Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (12%), or Refugee Support (6%) (Figure 2.10). This reflects that participation in social programs is an important channel through which adults are referred to career services in Canada.

Figure 2.9. Adults’ financial contribution to career guidance

Note: The average includes the 10 countries covered by the SCGA: Argentina, Canada, Chile, Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States. Data refer to the last time the respondent used a career service (in the case of Canada) or spoke to a career guidance advisor (for all other countries).

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

Figure 2.10. Beneficiaries of additional income support, Canada

Note: Respondents could choose more than one answer. Data refers to the last time the respondent used career services.

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

2.2. Inclusiveness of career guidance services

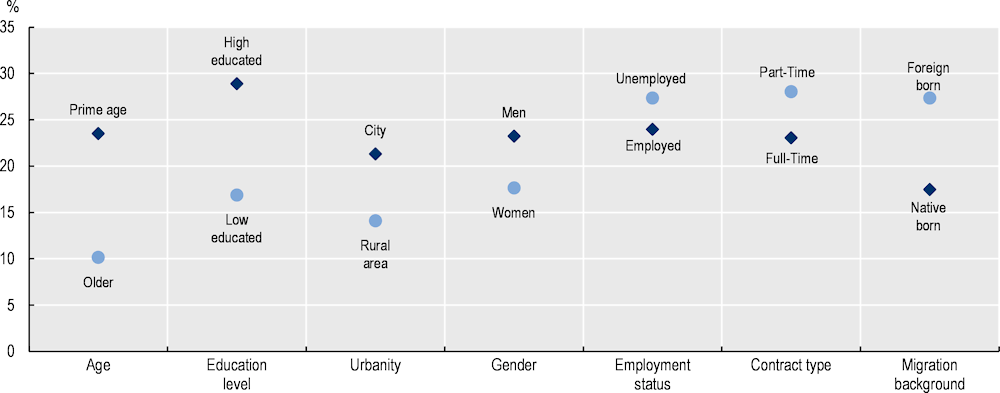

Not all Canadian adults use career guidance services equally (Figure 2.11). Some groups are much less likely to use career services, including low-educated adults (17% versus 29% for highly‑educated adults), older adults (10% versus 24% for prime‑aged adults) and those living in rural areas (14% versus 21% for adults living in cities). Women also use career guidance less than men (18% versus 23%). The use of career guidance among immigrants is higher than among the native‑born population in Canada (27% versus 17%), possibly reflecting Canada’s targeted services to support the labour market integration of immigrants. Part-time employed use career guidance more than full-time employed (28% versus 23%), and unemployed adults in Canada use career guidance more than employed adults (27% versus 23%). This latter result is unique to Canada. On average across the countries in the survey, employed and unemployed use career guidance equally. The lower use of career guidance among employed adults in Canada may reflect that they are less likely to seek career guidance when looking for education or training opportunities or to progress in their job (Figure 2.3). Table 2.1 presents results from a probit regression which isolates the impact of each of the above factors on the use of career guidance. All relationships from the descriptive analysis above continue to hold, though the explanatory power of the model is very low.

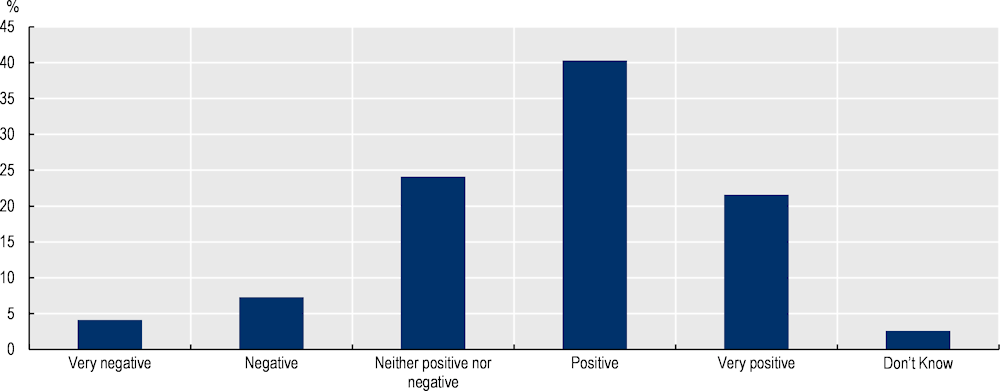

Adults who feel that their jobs are at risk are unfortunately not more likely to consult career guidance services in Canada, in contrast to other countries in the survey (Figure 2.12). Less than 10% of adults who reported feeling “negative” or “very negative” about their future labour market prospects sought career guidance. This contrasts with 40% of adults who reported feeling “positive”, and with 22% of adults who reported feeling “very positive.” This pattern differs markedly from that of other countries in the survey, where adults who were most worried about their career prospects were more proactive in participating in career guidance. Since adults whose jobs are at risk, or could be in the future, could arguably benefit the most from career guidance, this is an area to investigate and address.

There are also regional differences in the use of career guidance among adults. Across Canada, adults in Ontario use career guidance the most (23%), while those in the Atlantic provinces and Quebec use career guidance slightly less than the Canadian average (18% and 17%, respectively). British Colombia and the Prairie provinces all had participation rates close to the Canadian average of 19%. This might reflect that services in Ontario are available to wider groups of people than in other parts of Canada.

Figure 2.11. Use of career guidance services, by socio‑economic and demographic characteristics, Canada

Note: The low educated group includes adults with a low or medium level of education (i.e. less than a bachelor’s degree). Prime age refers to adults aged 25‑54, and older to adults aged 54 or more.

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

Table 2.1. Use of career guidance services, by socio-demographic and demographic characteristics, Canada

Marginal effects from a probit regression

|

All respondents |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Age (ref=25‑54) |

|

|

|

>54 |

‑0.113 |

*** |

|

Place of residence (ref=Urban) |

|

|

|

Rural Area |

‑0.042 |

** |

|

Education (ref=Low-educated) |

|

|

|

Highly-educated |

0.076 |

*** |

|

Gender (ref=Men) |

|

|

|

Women |

‑0.040 |

*** |

|

Employment status (ref=Employed) |

|

|

|

Unemployed |

0.048 |

** |

|

Inactive |

‑0.101 |

*** |

|

Migration (ref=“foreign” born) |

|

|

|

Native born |

‑0.060 |

*** |

|

Pseudo R2 |

0.062 |

|

|

Observations |

3563 |

|

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. The table reports marginal effects, i.e. percentage change in the outcome variable following a change in the relevant explanatory variable. Marginal effects for categorical variables refer to a discrete change from the base level. For some variables, some categories are not shown in the table.

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

Figure 2.12. Use of career guidance services among adults, at different levels of confidence about future labour market prospects, Canada

Source: OECD 2020/2021 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA).

2.2.1. Active outreach can support greater use of career guidance by under-represented groups

Adults who use career guidance less already face challenges in the labour market. Older, low-educated adults and those living in rural areas tend to participate in training less than their counterparts do (Figure 2.11). They also face greater challenges in accessing employment opportunities. Adults who feel negatively about their future labour market prospects are also less likely to use career guidance services, suggesting that they may not be aware that such services exist, or that services do not meet their needs. With better outreach, career guidance could motivate and support these adults to access training and employment opportunities.

While Canada has dedicated funding to support the labour market integration of under-represented groups, there is little in the way of active outreach. All seven provinces that responded to the OECD policy questionnaire reported that they have policies or programmes in place to target disadvantaged groups and support their access to career development services. For the most part, this refers to earmarked funding for employment services for specific groups under the federal-provincial transfer payment agreements. For instance, the WDAs allocate specific funding to employment and training supports for persons with disabilities, as does the federal Opportunities Fund for Persons with Disabilities. Provinces also reported applying a Gender Based Analysis (GBA+) lens to new employment services programmes, which involves considering how diverse groups of people may experience new programmes. However, no province mentioned having programmes in place to actively reach out to vulnerable adults in the community to connect them with career guidance services.

International examples shed light on possible outreach methods. Jobs Victoria Advocates is an Australian programme that has “advocates” reach out to vulnerable groups in the community to connect them with employment services, including career guidance. Advocates connect with adults where they already are: libraries, community centres, public housing foyers, shopping centres and other community services. In some cases, they even make door-to-door visits. As an alternative approach, facilitators of the Guidance and Orientation for Adult Learners (GOAL) project in Europe built partnerships with community organisations that provided them with referrals to potentially vulnerable adults (Box 2.1). In the Netherlands, the trade union CNV offers career guidance services to its members through James Loopbahn (James Career) and trained “Learning Ambassadors” are tasked with reaching out to lower-educated adults or those who might be at risk of losing their job to connect them with guidance and training.

Box 2.1. Outreach to low-educated adults to participate in career guidance

Project GOAL – Guidance and Orientation for Adult Learners

The hypothesis underpinning Project GOAL was that an independent one‑stop guidance service that focuses on the specific needs of low-educated adults could increase the participation of this group in adult learning.

Six European countries piloted new guidance models as part of this project: Belgium (Flanders), the Czech Republic, Iceland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Slovenia. While each programme sought to develop a guidance model suited to the respective country’s potential clients, there were a number of shared practices: guidance services that were one‑to‑one and face‑to-face, unbiased (i.e. not promoting courses offered at only one given educational institution), tailored, empowering, and informative.

Outreach activities to identify and attract low-educated adults to GOAL were an important part of the programme. Most countries achieved their service user recruitment targets through referrals from partner organisations. Building these partnerships required a lot of time and effort, as did building relationships with the adults themselves.

Lack of knowledge about educational opportunities was found to be a key barrier to training, and the GOAL programme filled this knowledge gap. Based on surveys 2‑4 months after the programme ended, 38% of participants reported that they had fully achieved their educational goals and an additional 50% said they had made some progress towards these goals. Among those who had entered the programme to pursue educational (as opposed to employment) objectives, 71% had enrolled in a course.

Some caveats were noted. First, education guidance may not be a sensible investment for governments in the absence of free or subsidised adult education courses that clients can progress into. Second, building partnerships with community organisations was necessary to secure participation of low-educated adults in the programme, and this proved to be more costly and to require more effort the more vulnerable or hard-to-reach the potential client was.

Source: Carpentieri et al. (2018[2]). “Guidance and Orientation for Adult Learners: Final cross-country evaluation report”, https://adultguidance.eu/images/Reports/GOAL_final_cross-country_evaluation_report.pdf.

2.2.2. Targeting services to the specific needs of vulnerable groups can also improve inclusiveness

Another way to improve the inclusiveness of the adult career guidance system is by better targeting services to the specific needs of vulnerable groups. Compared to delivering career guidance to young people, delivering career guidance to adults can be more challenging because adults tend to have more complex needs, including the need to support a family. Policy questionnaire responses indicate that providing career guidance to adults with low literacy, numeracy or digital literacy is a particular challenge.

Many career guidance services in Canada are designed for particular groups, including Indigenous people, people with disabilities, and newcomers to Canada. For instance, British Colombia’s Career Paths for Skilled Immigrants programme offers skilled newcomers career guidance, as well as financial support for language training, assessment of credentials and experience, and support in getting foreign credentials recognised in Canada. In Nova Scotia, the public employment service has agreements with third-party organisations to provide employability and technical skills training, work experience and jobs in IT for under-represented groups in the workforce, including visible minorities.

During interviews, several experts identified Indigenous groups as a vulnerable population that could be better served by career guidance. Experts stressed that services for Indigenous groups require a partnership approach, whereby the services are designed in partnership with community leaders. By marrying the traditional Indigenous advice‑giving approach with insights and experience from the professional career services, the hope is that Indigenous adults could be better served. A qualitative study on Indigenous adult women in Quebec finds, for example, that career guidance was successful in supporting the attainment of educational and career goals when career guidance advisors were sensitive to and aware of the complex barriers to employment faced by this group (Joncas and Pilote, 2021[3]). The People and Communities in Motion programme in Quebec provides an example of a programme aimed at improving the employability of adults facing multiple complex barriers by establishing year-long client-counsellor relationships and targeting services to the unique needs of the client (Box 2.2).

Offering career guidance programmes that are well-tailored to the needs of particular groups requires sufficient and consistent funding. In the policy questionnaire, several provinces noted that additional resources would support career development for under-represented adults. For instance, Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Immigration and Career Training called for funding to support further skill and career enhancement for older workers, and particularly to develop assessment tools to track their skills and to facilitate their access to training. Alberta1 emphasised the need for funding to develop specialised assessment and career planning tools, including pre‑employment assessments for Indigenous groups. Nova Scotia’s Labour and Advanced Education Ministry expressed the need for funding to carry out longer‑term evaluations of career guidance programmes for low-skilled and low-qualified adults, recognising that labour force attachment of these groups is a longer-term investment.

Box 2.2. People and Communities in Motion – Quebec

The Quebec Government commissioned a study to understand the effectiveness of People and Communities in Motion (PCM), a 12‑month career guidance programme which aims to improve employability of long-term unemployed adults who have many and complex barriers to employment. The programme took place in nine communities in Quebec between 2008 and 2010. During the programme, participants received financial support to cover childcare and transport costs.

The PCM approach follows an open framework that allows for flexibility and targeting services to the unique needs of the individual. Common factors include a year-long commitment that generally involves a series of informal group activities or individual career guidance meetings. Innovative aspects of PCM include locating services within local community centres, close to where the adult lives, as well as its strong emphasis on participation in community projects and a mobilisation of key community resources. At the end of the community project, participants engaged in a skills assessment (bilan de compétences), which aimed to validate both the skills they had acquired through the community project and in their previous experience. Following this, they received group guidance towards achieving their educational and employment objectives.

The study found a number of positive impacts from the programme, including higher self-esteem, sense of self-efficacy related to succeeding in work or a training programme, perception of social support, motivation to work and a decrease in negative emotions. Over the course of the programme, the majority of participants entered employment, internships, studies or volunteer work. The relationships created during the community project facilitated the movement of participants towards work or education. The average number of months on social assistance also decreased, and many participants reported less feelings of social isolation as a result of the programme. In some groups, lifestyle improvements were observed in use of drugs and alcohol, diet, and fitness. The study also noted impacts on the counsellors and facilitators; notably, a newfound appreciation for the complexities of the obstacles that participants encounter in their life contexts.

Source: Michaud, G. et al. (2012[4]), Développement d’une approche visant à mobiliser la clientéle dite éloignée du marché du travail, http://bv.cdeacf.ca/EA_PDF/161000.pdf.

Assessment and recommendations

Survey data suggests that Canadian adults use career guidance much less than their counterparts in other countries, particularly when choosing an education or training opportunity or when they want to progress in their current job. The most common reasons reported for not using career guidance were not feeling a need for the services, and not being aware that services existed – but these shares of non‑users were comparable to those in other surveyed countries. Canada had a higher share of adults reporting not having enough time due to work or childcare/family responsibilities as the main reason they did not use career guidance.

To raise awareness about career guidance services, provinces and territories could strengthen referrals between public services and launch a media campaign to draw attention to the availability of career guidance opportunities and their value.

As noted in Chapter 1, governments should strengthen the capacity of the provincial government-run employment services to create proactive career guidance opportunities for adults in employment. Also, better co‑operation between training providers, government-run employment services and employers would support greater participation in career and training guidance for adults.

More could be done to engage under-represented adults in career guidance, in particular vulnerable groups such as low-educated, older adults and those living in rural areas. These adults are both less likely to use traditional career services and to search online for information about employment and training opportunities. In contrast to adults in other countries, adults in Canada who feel that their jobs are at risk are less likely to consult career guidance services than their peers who are less at risk. Lessons from the GOAL project in Europe and Quebec’s People and Communities in Motion pilot suggest that engaging under-represented adults in career guidance and training is possible, but requires considerable time and financial investment, and a mobilisation of key community resources.

Provincial and territorial governments should dedicate funding to actively reach out to vulnerable adults in their communities and workplaces and better target career guidance services to their needs.

References

[2] Carpentieri, J. et al. (2018), GOAL Guidance and Orientation for Adult Learning. Final cross-country evaluation report, UCL Institute of Education, https://adultguidance.eu/images/Reports/GOAL_final_cross-country_evaluation_report.pdf.

[1] Cedefop et al. (2020), Career Guidance Policy and Practice in the Pandemic. Results of a Joint International Survey, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/318103.

[3] Joncas, J. and A. Pilote (2021), “The role of guidance professionals in enhancing the capabilities of marginalized students: the case of indigenous women in Canada”, International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, Vol. 21, pp. 405-427, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09474-3.

[4] Michaud, G. et al. (2012), Développement d’une approche visant à mobiliser la clientèle dite éloignée du marché du travail. Rapport final de la recherche déposé au ministère de l’Emploi et de la Solidarité sociale, Université de Sherbrooke, http://bv.cdeacf.ca/EA_PDF/161000.pdf.

Note

← 1. Labour and Immigration Ministry in collaboration with Community and Social Services, Advanced Education and Indigenous Relations.