Claudia Diehl

Nadia Granato

Claudia Diehl

Nadia Granato

The chapter begins with a brief demographic sketch of Turkish and Yugoslav immigrants and their offspring in Germany based on data from 2012. It then describes their situation in the education system and in the labour market in 2000 and in 2012. In doing so it assesses how immigrant-native gaps vary across generations and over time, with separate analyses for men and women. The discussion explores the factors triggering intergenerational progress and change, exploring the extent to which a lack of educational attainment results in later disadvantage in the labour market. The most prevalent approaches to explaining group-specific trajectories are presented, with the focus on the ongoing disadvantage for those of Turkish descent. Factors other than educational attainment are also explored, namely by addressing the most important results from existing studies on the role of language skills, social ties and ethnic discrimination.

Generational progress in educational attainment can be found for the native-born children of both Turkish and former Yugoslav immigrants. Although 50% of female and about 30% of male Turkish immigrants born abroad did not possess any educational degree, less than 10% of their native-born children had left school without any diploma in 2012. The educational levels of Yugoslav immigrants and their children are relatively higher than those of Turkish immigrants and their offspring.

Over time, the share of Turkish immigrant women holding no educational degree whatsoever has increased and indeed was higher in 2012 (49% among women) than it was in 2000 (33% among women). This finding most likely reflects ongoing marriage migration of Turks with low levels of education and is likely to influence the intergenerational mobility patterns observed among the offspring of Turkish immigrants.

Almost every fourth child of Yugoslav immigrants and every fifth of Turkish immigrants left school with the Abitur in 2012 and was thus formally allowed to take up university studies.

Substantial gender differences can be found among those not active in the labour market. Among all groups, including native Germans, the share of women who are not in employment or training and not looking for a job is two times (native Germans) to four times (German-born children of immigrants) higher than for males of the same group. Every fifth woman born in Germany of Turkish parents is not active in the labour market at all.

Occupational status is still lower for immigrants and immigrants’ offspring than for native Germans, especially among those with Turkish roots. Status scores were slightly higher among German-born females than among German-born males for both Turkish and Yugoslav parental origin groups, while the same gender difference does not apply to Germans of native descent.

Over time, there was little change in occupational status for the children of immigrants. Males with Turkish roots and females with Yugoslavian roots overall show stagnating status scores, while the occupational status of females with Turkish roots and males with Yugoslav roots is slightly increasing.

After controlling for education – that is, when comparing individuals holding similar educational degrees – male and female children of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia no longer differ from native Germans in a statistically significant way. However, Turkish males and females still do, even though these differences are rather small.

Analyses of immigrant-native gaps in occupational status over time reveal that German-born males with parents born in Turkey did not differ significantly from native Germans with similar educational degrees back in 2000, i.e. gaps have increased rather than decreased over time. For German-born females with parents born in Turkey, the change between both years was less pronounced. For both male and female children of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia, no substantive changes can be observed.

The chapter accords with previous research demonstrating the importance of educational degrees for the labour market situation of immigrants’ offspring. As the labour market disadvantage of the children of parents born in Turkey is not fully explained by their lower educational endowments, recent studies show that two factors are important in explaining this puzzle: inter-ethnic ties and lower German language skills. While German language proficiency seems to be of particular importance in the labour market integration of children of parents born in Turkey, intra-group ties and fluency in the language of the country of parental origin do not seem to have any effect.

In the past few years, Germany has taken in large numbers of refugees from the Middle East and Africa. Even though these groups are currently the focus of public and academic debate, the current migrant population still mainly reflects the German guest worker (Gastarbeiter) legacy. Most individuals with a non-German background come from recruitment countries that include Turkey, the former Yugoslavia, Italy, Spain and Greece. Their social status also reflects the fact that most of them were recruited expressly as low-skilled labourers. While some former guest worker groups have made great strides in terms of their integration, others still struggle on their way upwards in the education system and the labour market.

The largest single group with a labour migrant background in Germany is the Turks. This group includes individuals who immigrated as so-called “guest workers”; their family members who entered Germany as spouses before or soon after the recruitment stop in 1973; and Kurds, who mostly arrived as asylum seekers. Afterwards, many individuals entered the country as “marriage migrants”, joining their spouses who were often born in Germany. In 2015, 28 000 individuals emigrated from Turkey to live in Germany (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2015); during the past years immigration figures have been rather low for this group.

The second largest group that immigrated as guest workers is the migrants from the former Yugoslavia. After the recruitment period, many individuals entered the country in the 1990s as refugees from the Balkan wars. In 2015, immigration from the successor states of Yugoslavia to Germany was much higher than from Turkey to Germany: about 57 000 individuals emigrated from Croatia, 42 000 from Serbia and 41 000 from Kosovo, to name just the largest sending successor states (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2015).

Many children of these immigrants from Turkey and the former Yugoslavia that were born in Germany have entered the education system or the labour market. The two groups show distinct patterns of integration in both fields: Turks lag behind in both systems according to numerous studies (Kalter, Granato and Kristen, 2007; Kalter and Granato, 2017; Hartmann, 2016; Diehl, Hunkler and Kristen, 2016). In turn, migrants from the former Yugoslavia have become more similar to natives. This chapter provides an overview of the integration patterns of German-born children of immigrants with Turkish and Yugoslav roots, both in the education system and in the labour market. The overview will be broader than existing studies that focus mostly on the status quo in only one of the two systems. Moreover, it will also describe patterns separately for men and women and assess change across generations and over time. After presenting results based on the German Microcensus, the discussion will focus on the most prevalent approaches explaining these group-specific trajectories.

To analyse the intergenerational mobility of migrants, the chapter will draw on data of the German Microcensus (GMC), an annual household survey of 1% of the population in Germany (Lüttinger and Riede 1997). The study combines data for the years 2000 and 2012. Analyses only include respondents living in the western part of Germany, because the classic labour migrants and their descendants still mostly live in this area. GMC information on parents’ country of birth is available only for certain years since 2005, and is restricted to whether the parents were born in Germany or born abroad. Therefore, citizenship is used – and in 2012 former citizenship as well – to identify the different ethnic groups. Based on (former) citizenship and whether respondents were born in Germany, four groups are classified: Turks born in Germany, Turks born abroad, (former) Yugoslavs born in Germany and (former) Yugoslavs born abroad. These groups are compared to Germans of native descent.

The analyses include naturalised and non-naturalised citizens who emigrated from Turkey and Yugoslavia or one of its successor states, and the children of these immigrants. However, the migration background of individuals with German citizenship can only be identified in the GMC from 2012, and so the two data waves used are not perfectly comparable. To exclude naturalised individuals from the 2012 GMC would lead to a distorted and overly negative picture of integration processes over time, because naturalisation has accelerated since the late 1990s and integration is positively related to naturalisation (Diehl and Blohm 2008). To include them skews the analyses in the opposite direction, because naturalised individuals are part of the German comparison group in 2000. The chapter therefore presents results including German citizens with former Turkish or Yugoslav citizenship in the respective groups of immigrants and their offspring in 2012, denoted by “2012n”. When analysing change over time, respondents with a former foreign citizenship are included in the German comparison group (denoted by “2012”) for the sake of comparability with the 2000 data.

Educational attainment is measured with regard to the level of general secondary schooling and four levels are distinguished: the highest level (Fachhochschulreife/Abitur, i.e. maturity certificate), the intermediate level of general secondary education (Realschulabschluss), the basic level (Hauptschulabschluss), and no general secondary education accomplished. An additional category indicates whether information on the level of general secondary schooling is missing. Four groups capture the degree of labour market participation: participation in education or training, being employed, being unemployed, and no labour market participation. To compare occupational attainment between the four ethnic groups described above and the German reference category, the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI) is used, with scores varying between 18 and 90.

The chapter begins with a brief demographic sketch based on data from 2012 and then describes the situation of immigrants from Turkey and Yugoslavia and their children in the education system and in the labour market in 2000 and in 2012. In doing so it will assess how immigrant-native gaps change across generations and over time. The discussion then explores the factors triggering intergenerational progress and change, based on results from linear regression models. The estimated regression coefficients are presented as average marginal effects (AME). While the large number of cases covered by GMC data makes it possible to assess the extent to which labour market disadvantages for both immigrants and their offspring reflect educational degrees and thus their human capital, other factors known to play a role can only be analysed using specific survey data. The chapter thus sums up the most important findings from existing studies on the role of language skills, social ties and ethnic discrimination.

A substantial share of individuals with Turkish or “Yugoslav” roots in Germany were born in the country – according to the GMC sample, about 40% and 25%, respectively. Both immigrants and their offspring1 include naturalised and non-naturalised individuals. As can be seen in Table 3.1, 26% of the children of Turkish immigrants and 24% of Turks who immigrated themselves acquired German citizenship. The share is somewhat lower among immigrants and their offspring from the former Yugoslavia (17% and 22%, respectively – see Diehl and Blohm, 2008).

The gender ratio is almost balanced in all groups. At 21 and 22 years on average respectively, the children of Turkish and former Yugoslav immigrants are considerably younger than those immigrating, that is in their late 40s. Germans of native descent are older, at 44 on average, than the offspring of immigrants – a fact that needs to be taken into account when analysing majority-minority gaps especially in terms of educational attainment and labour market participation.

Only one in four individuals with Turkish roots and about one in three with Yugoslav roots immigrated during the recruitment period that ended with the halt in 1973. Some 32% of immigrants from Turkey and 42% of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia arrived in Germany after 1990. In both groups, the majority arrived between the ages of 7 and 25.

By migration background, 2012

|

|

Persons of German descent |

Children of Turkish immigrants |

Turkish immigrants |

Children of (former) Yugoslav immigrants |

Immigrants from the former Yugoslavia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Naturalised (%) |

- |

26.3 |

23.7 |

16.9 |

21.9 |

|

Gender (%) |

|||||

|

Male |

48.6 |

52.5 |

50.6 |

52.0 |

46.7 |

|

Female |

51.4 |

47.5 |

49.4 |

48.0 |

53.3 |

|

Age (mean) |

44.3 |

21.2 |

46.3 |

22.1 |

49.4 |

|

Number of cases |

330 378 |

4 841 |

7 356 |

1 178 |

3 572 |

|

Period of immigration (%) |

|||||

|

Up to 1973 |

24.2 |

36.5 |

|||

|

1974-1990 |

42.3 |

19.7 |

|||

|

Since 1991 |

31.9 |

42.2 |

|||

|

Missing |

1.6 |

1.6 |

|||

|

Age at immigration (%) |

|||||

|

Up to 6 years old |

12.9 |

12.0 |

|||

|

7-18 |

33.2 |

30.2 |

|||

|

19-25 |

28.8 |

30.3 |

|||

|

26-30 |

12.9 |

13.4 |

|||

|

31-40 |

8.3 |

9.4 |

|||

|

41 and older |

2.2 |

3.0 |

|||

|

Missing |

1.6 |

1.6 |

Note: Naturalised respondents are included in the respective ethnic group according to their former citizenship. There is no restriction on age. For more information on how the different groups are constructed, see the section “Data” above.

Source: German Microcensus (GMC) (2012).

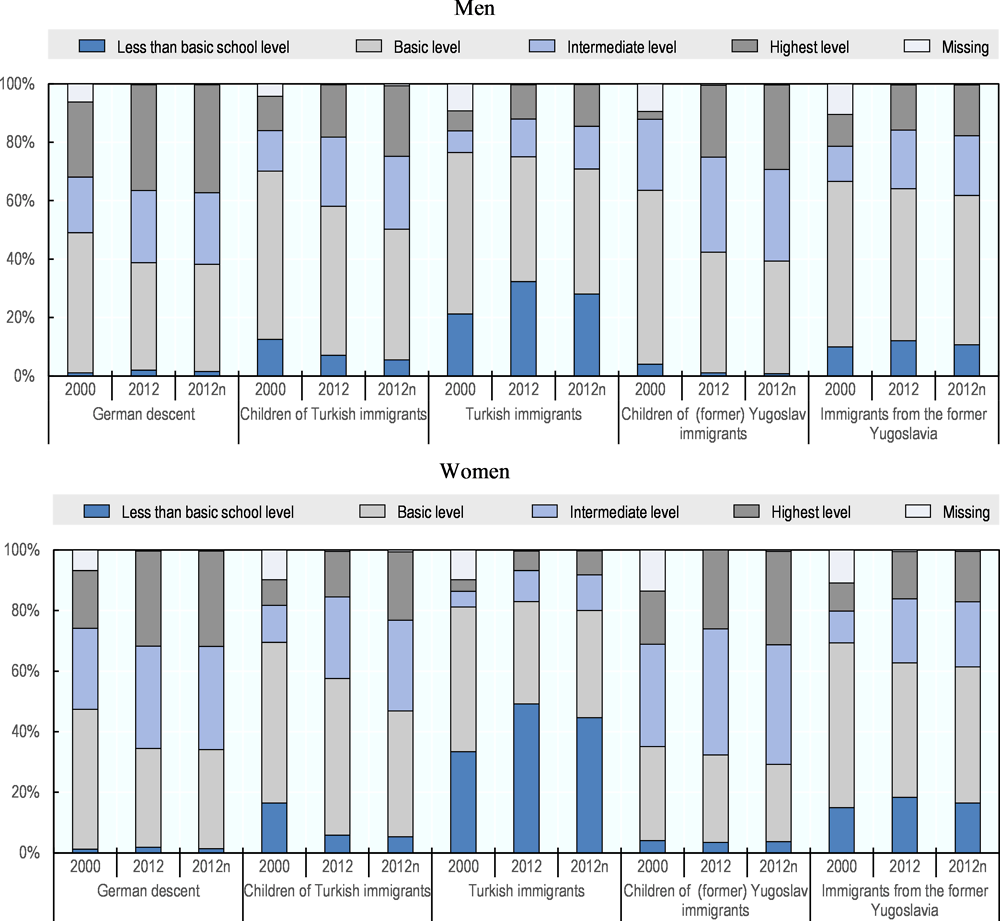

Figure 3.1 shows that the native-born children of immigrants still hold lower educational degrees than Germans with native-born parents in 20122. This applies to individuals with both Turkish and Yugoslav parents and to men and women, independent of whether naturalised individuals are included in one of the groups or in the comparison group with German parentage (see Figure 3.1).

Notes: “2012n” – naturalised respondents are included in the respective ethnic group according to their former citizenship; “2000” and “2012” – naturalised respondents are included in the German comparison group. The categories correspond to the following German qualifications: Basic level education corresponds to the German “Hauptschulabschluss”, intermediate-level to a “Realschulabschluss”, and the highest level to the “Abitur” or “Fachabitur”. For more information on how the different groups are constructed, see the section “Data” above.

Source: GMC (2000 and 2012).

Less than 10% of the children of Turkish immigrants – no matter whether they are naturalised or not – have left school without any diploma in 2012 (less than basic secondary school level). This share is lower for the children of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia. The most common educational attainment in both groups is still the basic level (Hauptschulabschluss), particularly among those with Turkish roots. Many children of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia have obtained an intermediate-level diploma (Realschulabschluss), and the share of those who have completed the highest diploma and are thus ready to enrol at a university or a university of applied sciences (Fachhochschule) is also substantial, and approaches the share of those of German descent. Note, however, that this last group includes older individuals who finished school prior to the educational expansion in the 1970s. In 2012, almost every fourth child of Yugoslav immigrants and every fifth of Turkish immigrants left school with the Abitur. For both offspring groups, this share is distinctly higher when naturalised individuals are included. This ambivalent picture becomes somewhat clearer when changes across generations and over time are examined.

Generational progress is substantial for both origin groups, especially among females. This shows once more how important it is to study generational change rather than absolute levels of integration. Compared to the children of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia, those of Turkish descent started out from very low educational levels in their parents’ generation, as a look at those immigrating shows. In 2012, about 50% of female and about 30% of male Turkish immigrants born abroad did not possess any educational degree. Given this rather difficult starting position, the children of Turkish immigrants have caught up substantially.

A look at development over time also reveals a dynamic picture for the children of immigrants. The share of individuals with a Turkish background who hold at least an intermediate school diploma was substantially higher in 2012 than in 2000, and the same applies to the share of those ready to enrol in tertiary education, even though it is still rather low in 2012. Among the offspring of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia the picture is similar with a higher share of Abitur in 2012 than back in 20003.

However, change over time was much less dynamic for those who immigrated themselves (see Figure 3.2). In fact, the share of Turkish immigrants holding no educational degree whatsoever is even higher in 2012 than it was in 2000. Among females, the share of individuals who have left school without a diploma has increased from about 33% to 49% or 44% (respectively excluding and including naturalised citizens) during this time period.4 This puzzling finding most likely reflects an ongoing marriage migration of Turks with low levels of education. For this group, there are few other options to enter Germany legally. This would also explain why the increase in immigrants without any educational diploma is higher among females. Though gender differences are only moderate, more Turkish wives joined husbands living in Germany than vice versa (Aybek et al., 2013). In any case, this “replenishment” obviously did little to increase the educational levels of Turkish immigrants living in Germany, even though educational levels rose in Turkey between 2000 and 2011 (OECD, 2013).

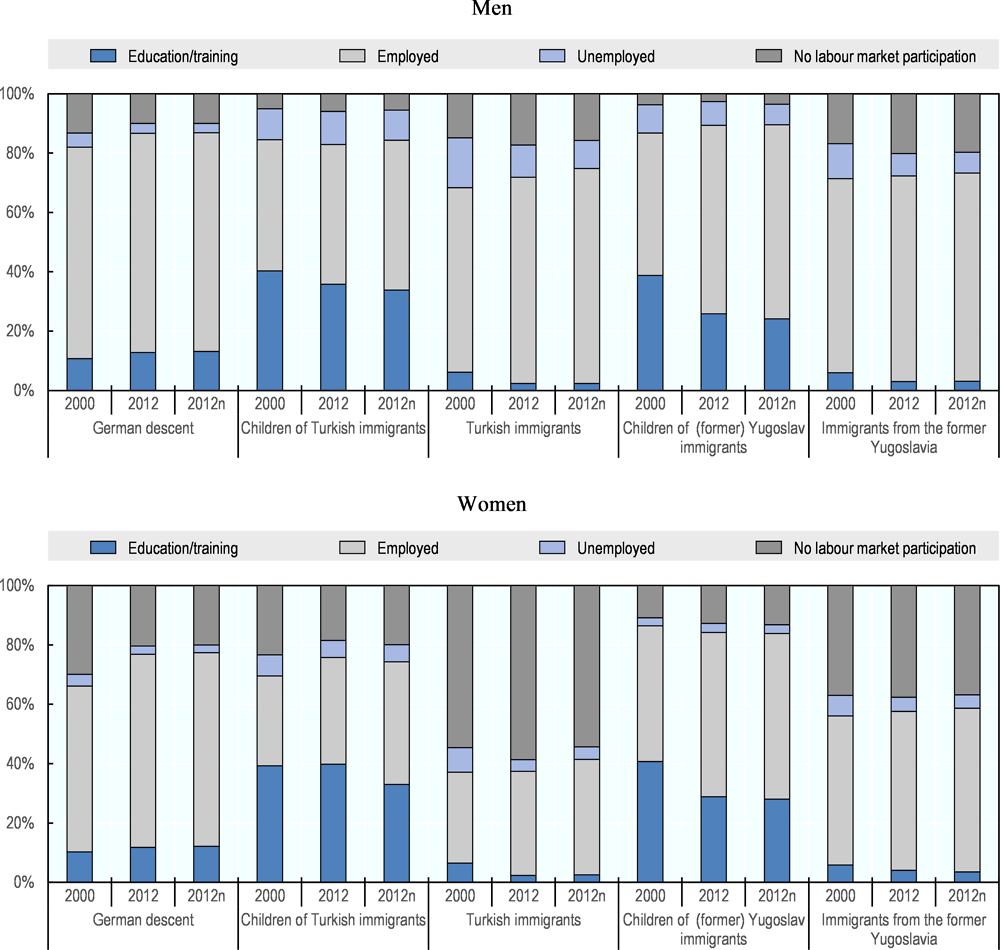

Trends in educational endowments across generations and over time have far-reaching implications for the integration of immigrants’ offspring into the labour market. In general, gender differences are more pronounced in the labour market than they are in the education system (see Figure 3.2).

Notes: “2012n” – naturalised respondents are included in the respective ethnic group according to their former citizenship; “2000” and “2012” – naturalised respondents are included in the German comparison group. For more information on how the different groups are constructed, see the section “Data” above.

Source: GMC (2000 and 2012).

In 2012, a large share of immigrants’ offspring was enrolled in some sort of education or training: about 35-40% of males and females with Turkish roots, and about 25-30% of males and females with Yugoslav roots (Figure 3.2). The larger share among Turks might at least partly reflect the fact that they are slightly younger (Table 3.1). While gender differences are not large in this respect, they become more substantial when it comes to labour market inactivity. Among all groups, including those of native German descent, the share of women who are neither in employment or training nor looking for a job is two times (native German descent) to four times (German-born individuals with a migration background) higher among females than among males. Every fifth woman of Turkish parentage born in Germany is not at all active in the labour market. In both immigrant origin groups, the share of those working is higher among men than among women. The offspring of Turkish immigrants not only have lower employment rates than Yugoslavs, but the gender gap is also larger for this group: the shares of employed Turkish males and females are 45% and 35%, respectively; those of Yugoslavs are 60% and 55%, respectively. The share of those seeking a job, i.e. the unemployed, is higher among men than among women for German-born individuals with Turkish or Yugoslav parents. Note that this is not the case among those of German native descent.

A comparison with those immigrating again reveals substantial generational change. Among those who themselves immigrated, the share of individuals who are neither in training nor otherwise active in the labour market is very high, especially among females and especially among Turkish females. Among females who immigrated from Turkey, between 54% and 59% were not active in the labour market in 2012.

There was little change in employment status over time for immigrants and their children. Between 2000 and 2012, an “ageing” of the immigrants offspring can be observed that is evident in the decreasing share of those individuals in training.

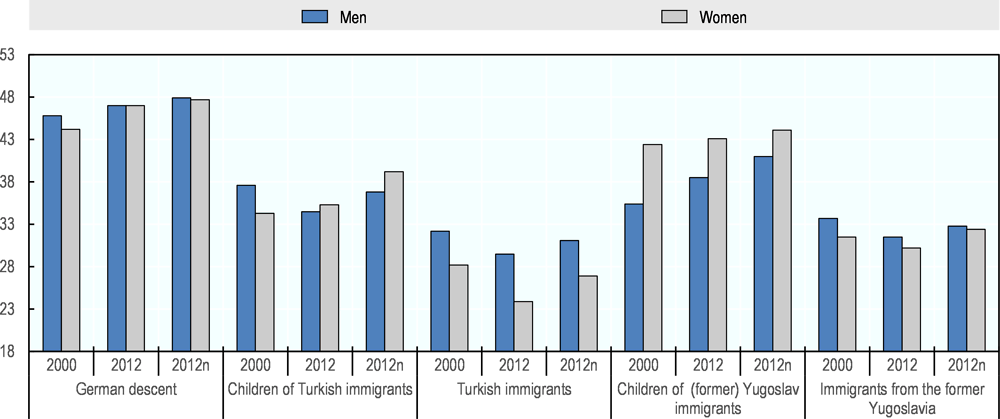

Turning to the occupational status of those who have a job in 2012, the ISEI scores reveal first of all that the children of immigrants, especially those with Turkish roots, still differ from Germans of native descent (see Figure 3.3). No matter which origin group is examined, scores were slightly higher among German-born females compared to German-born males in 2012, while this was not the case among Germans of native descent. This gender difference is more pronounced among children of Yugoslav immigrants. In fact, the ISEI scores of German-born females with Yugoslav parents are more similar to those for Germans of native descent than they are for any other group.

Notes: “2012n” – naturalised respondents are included in the respective ethnic group according to their former citizenship; “2000” and “2012” – naturalised respondents are included in the German comparison group. Scores of the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI) vary from 18 to 90. The higher the ISEI score, the higher the occupational prestige. For more information on how the different groups are constructed, see the section “Data” above.

Source: GMC (2000 and 2012).

When compared with those who themselves immigrated, it can be seen that generational change is more pronounced among females than among males. In both groups, male immigrants tend to have jobs with slightly higher ISEI levels than female immigrants, while the opposite is true for immigrants' offspring born in Germany.

Over time, there was less change among the offspring of immigrants, as one would expect based on the dynamic changes in their educational attainment. Results also depend on whether naturalised citizens are included in the German comparison group or in the immigrant or offspring group in 2012. For children of Turkish immigrants, a moderate increase in ISEI scores can only be found among females and only when naturalised individuals are included in the Turkish offspring group (“2012”). Male children of Turkish descent show stagnating (2000-12) or even slightly declining (2000-12) ISEI scores. Naturalisation does not make much difference for native-born individuals with Yugoslav roots. In this origin group, females are consistently better off than males in terms of their absolute ISEI scores, though males show more increase over time.

Turning to the occupational status of those who immigrated, we see that it has slightly declined for some groups, especially among women with Turkish citizenship. As hypothesised above, this could reflect a changing composition of migrating individuals over time. In 2012 this group seems to include more recently arrived marriage migrants from Turkey. Such changes in the composition of this group – more volatile than that of the children of immigrants – could (over)compensate increasing levels of education among those immigrating who have been in the country longer.

Overall, the integration of those born in Germany of Turkish and Yugoslav descent – both in the education system and in the labour market – is a matter of generational change rather than change over time. While Turks born in Germany in particular have caught up considerably, lower educational attainment still predominates for this group. Yugoslavs born in Germany, on the other hand, have started to catch up even with respect to the share of Germans of native descent who are ready to enter the system of tertiary education. Both immigrant groups arrived for the most part as low-skilled labourers; some, lower in numbers, came as asylum seekers and refugees (see BMI/BAMF, 2013, p. 204). The analyses here, however, demonstrate that immigrating Turks had a much more difficult start in Germany in terms of their substantially lower educational endowments than those migrating from the former Yugoslavia. Individuals born in Germany with Turkish parents still struggle with this legacy.

The share of those who are active in the labour market or enrolled in some sort of training is much higher among German-born females with immigrant parents than among those who themselves immigrated. ISEI levels are also higher for the children of immigrants than for the immigrants themselves, especially among females. However, their ISEI levels are still lower than for those of native German descent. While generational change was substantial in terms of both groups’ occupational and employment status, change over time was at best moderate. Fewer offspring are in training, a process that reflects the ageing of that group. ISEI scores have increased moderately among the children of immigrants (at least for males and females with Yugoslav parents and females with Turkish parents) or stagnated between 2000 and 2012 (for native-born males with Turkish parentage). Astoundingly, they even declined slightly among those who immigrated from Turkey during this period.

So far the discussion has covered the children of immigrants’ educational attainment and their employment and occupational status on the aggregate level, and analysed change across generations and over time. It now turns to the question of which factors trigger their labour market integration.

According to human capital theory, the labour market performance of immigrants and their offspring mainly reflects their educational attainment, along with other aspects of their human capital such as job experience and training (for a detailed discussion see Kalter and Granato, 2017). Immigration of "guest workers" was selective with respect to human capital, since they were deliberately hired to perform jobs on the lower end of the occupational ladder. Furthermore, international migration – especially between countries that differ in terms of the quality of their education systems – often leads to a devaluation of immigrants’ human capital. In other words, even those immigrants who had acquired educational qualifications back home, or who had already gathered some work experience, could only partly “transfer” these qualifications and experiences to the German labour market. Immigrants’ motivation to acquire degrees and training in Germany was limited further because the recruitment programme was considered to be temporary in nature, with immigrants expected to eventually return to their countries of origin.

While these arguments cannot explain the labour market disadvantage of the children of immigrants who were born and raised in the receiving country, educational transmission is an important mechanism when it comes to the later generation’s inheritance of low educational qualifications (Kalter and Granato, 2017). It is well known that children of parents who have no higher educational qualifications are less prepared for a successful educational career. They possess fewer skills and competencies, which are often gained from the family, partly even before children enroll in school (Diehl, Hunkler and Kristen, 2016).

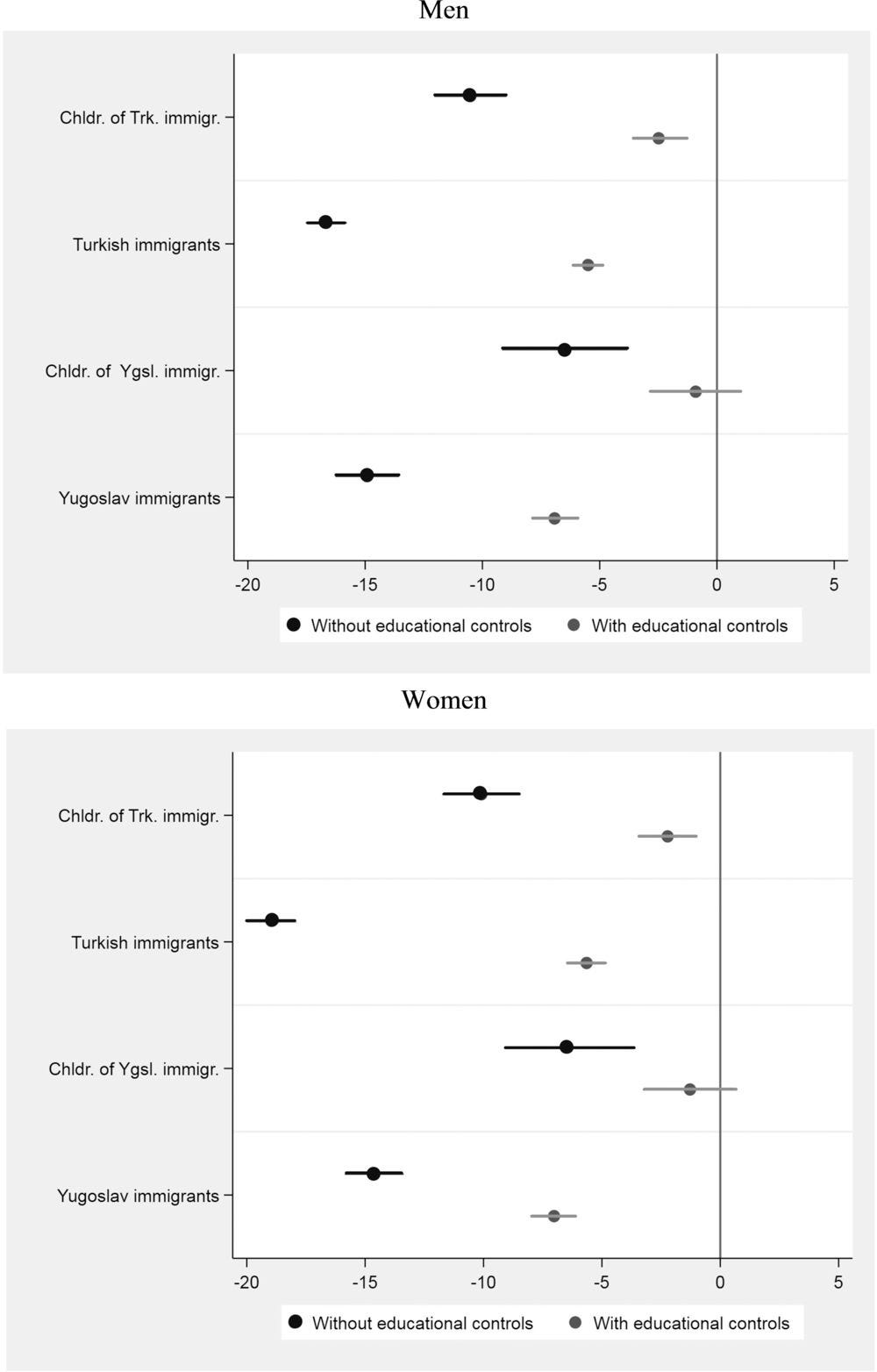

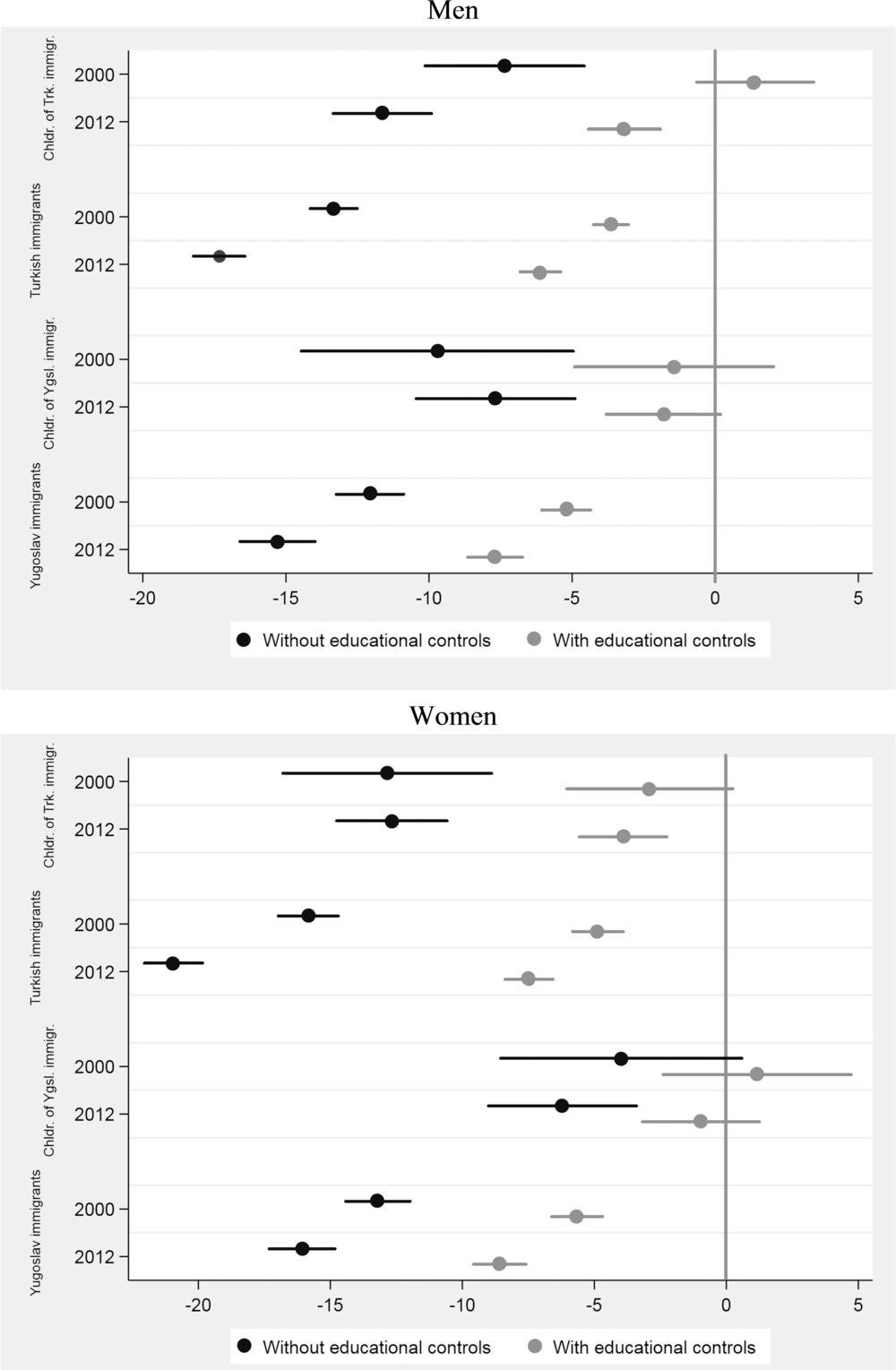

On the basis of these well-known theoretical arguments, one would expect that the labour market disadvantage of immigrants’ offspring above all reflects their educational attainment, which overall is lower than the attainment of Germans of native descent due to the mechanisms described above. Accordingly, the chapter will now look into how much of the labour market disadvantage is explained by the lower educational degrees of immigrants and their offspring. The focus will be on differences in occupational status (ISEI) between Germans of native descent on the one hand and native-born children of immigrants on the other, and the question whether or not these disparities persist after comparing immigrants and their children with German natives with similar educational degrees (see Figure 3.4). Since this discussion begins with describing the situation in 2012, naturalised individuals are included in the respective immigrant or offspring groups. All models include age and work hours. The position of Germans with no migration background is indicated by the vertical line.

Figure 3.4 shows that in 2012, German-born employees with Turkish or Yugoslav parents (see blue points) held jobs with lower ISEI scores than Germans of native descent (represented by the vertical red line). These differences are more pronounced for the offspring of Turkish immigrants, while gender differences are negligible. After education is controlled for (see red points), the male and female children of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia no longer differ from Germans of native descent in a statistically significant way, but the male and female offspring of Turkish immigrants still does. Note, however, that these differences are rather small, as the following example shows: when German-born males with Turkish parents are compared to Germans of native descent with similar educational endowments, the absolute difference in ISEI scores is 2.5 points (on an ISEI scale between 18 and 90).

Note: The points in the figure represent the estimated regression coefficients (Average Marginal Effects - AME), reflecting the estimated difference in ISEI scores between the comparison group (Germans of native descent, represented by the vertical red line) and immigrants and their children. The horizontal lines around the points show the coefficients' 95% confidence intervals. The estimation model without educational controls includes only information on age, weekly working hours and survey year. The model with educational controls adds two indicators of educational attainment, the levels of general schooling and vocational training. Naturalised individuals are included among Turkish and Yugoslav immigrants and their offspring. For more information on how the different groups are constructed, see the section “Data” above.

Source: GMC (2012).

Immigrants themselves, in turn, have jobs with a lower occupational status than Germans of native descent – even if individuals with similar educational degrees are compared (see red points). Most likely, educational degrees from Turkey and the former Yugoslavia were not valued in the German labour market and/or the immigrants lacked the language skills to find an adequate job in Germany.

Turning to changes over time of the occupational status of children of immigrants (i.e. between 2000 and 2012), the results are presented in Figure 3.5. Naturalised individuals had to be included in the group of native German descent in both years in order to ensure comparability. For most children of immigrants in Germany, there was not much change over time – that is to say, no statistically significant difference can be found between 2000 and 2012. There is one exception, however: German-born males with Turkish parents did not differ significantly from Germans of native descent in 2000 but – as already seen in Figure 3.4 – they do differ in 2012. For German-born females with Turkish parents we see a statistically significant migrant-native gap as well, but this group’s situation is more similar to the year 2000. For the offspring of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia, both males and females, no substantive changes over time can be observed.

A look at the immigrants themselves suggests as well that the differences between them and Germans of native descent were more pronounced in 2012 than they were back in 2000, especially among immigrants from Turkey. The most likely explanation for the widening gap between 2000 and 2012 is that immigrants who arrived or entered the labour market after 2000 had lower educational attainment. In fact, we have seen in Figure 3.4 that the share of immigrants who had no educational qualifications whatsoever was higher in 2012 than in 2000, especially among Turkish women.

In sum, three results of this analysis of immigrant families’ occupational status are noteworthy. First of all and most importantly, the children of Turkish immigrants of both genders continue to have jobs with a slightly lower occupational status than children of natives with comparable educational degrees, while this is not the case for the children of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia who are more or less on a par with children of natives. Secondly, the size of the gap between the male children of Turkish immigrants and Germans of native descent has widened over time. Thirdly, an increase in the native-immigrant gap over time can be found between immigrants from both countries of origin and the German comparison group.

The next section discusses possible explanations put forward in previous studies for the gap that remains after controlling for educational qualification between the occupational status of Turkish immigrants’ offspring and that of Germans of native descent. GMC data does not enable testing or even looking into these explanations, because important indicators for the potential mechanisms are not available.

Note: The points in the figure represent the estimated regression coefficients (AME), reflecting the estimated difference in ISEI scores between the comparison group (Germans of native descent, represented by the vertical red line) and immigrants and their children. The horizontal lines around the points show the coefficients' 95% confidence intervals. The estimation model without educational controls includes only information on age, weekly working hours and survey year. The model with educational controls adds two indicators of educational attainment, the levels of general schooling and vocational training. Naturalised individuals are included in the German comparison group. For more information on how the different groups are constructed, see the section “Data” above.

Source: GMC (2000 and 2012)

Previous studies in the labour market disadvantage of children of Turkish immigrants that remains even after controlling for their lower educational endowments have focused on two possible explanations. One emphasises ethnic discrimination, the other a lack of resources such as language skills and social ties that would help individuals make best use of human capital endowments. At first glance, much of the literature seems to favour the explanation centred on discrimination in the labour market. Survey data show that this group is less accepted generally than other labour migrants in Germany (Blohm and Wasmer, 2013). Audit studies have furnished some evidence of unequal treatment of individuals with Turkish sounding names. In many of these studies, applications are sent to employers that differ only with respect to the names of the alleged candidate. Several studies from Germany (but also from other European countries) show that Turkish names lead to lower callback rates. (For the German housing market see Auspurg, Hinz and Schmid, 2017; for the labour market see Kaas and Manger, 2011.)

However, minority members may (over)compensate actual or perceived discrimination by applying more often. On the other hand, they could be discouraged from applying for jobs and thus aggravate the impact of perceived or actual discrimination. In any case, it seems unlikely that the persistent labour market disadvantage of individuals with a Turkish background is fully explained by the rather moderate levels of unequal treatment identified in audit studies.

Recent empirical studies have therefore looked into immigrants’ and their offsprings’ endowments with resources that could help to make best use of a person’s human capital. For example, social ties have been shown to increase access to job-relevant information (Lancee, 2012; for a classic study see Granovetter, 1973). In this respect, there is a key difference between bridging and bonding social capital. Bridging social capital, in the case of immigrants and their offspring transcends the limits of closely knit immigrant communities. It thus provides access to information about, e.g. job vacancies outside of these dense networks. Bonding social capital is restricted to these networks, and consists of close relationships with other trusted members in the same community. Immigrant families’ bonding social capital may thus provide access to jobs mostly within these networks (Lancee, 2012).

The impact of bridging versus bonding social capital on the integration of immigrants and their children seems to depend on the resource endowments of the immigrant group as a whole. With respect to educational success, Kroneberg (2008) has shown that being in touch with persons from the same parental origin group has positive effects on children’s educational outcomes only in those ethnic groups that have on average high levels of education. Kroneberg’s study is based on US data, and no comparable study is available for Germany. This is partly due to the fact that given the country’s migration history, there is not much variation in the average skill level of large migrant groups. However, it is safe to assume that for low-skilled groups migrating to western countries, jobs outside the ethnic enclave offer a higher occupational status, are more secure, and lead to higher earnings than jobs within dense ethnic networks. Jobs inside the “ethnic economy”, in turn, may have the advantage of being accessible to minority members who may experience discrimination outside the ethnic enclave.

Studies on the role of networks and language skills in immigrants’ labour market integration lead to some robust findings: networks with native-born Germans and German language skills have a positive effect on labour market integration, while networks within the same parental migrant group and fluency in the language of the country of origin do not have any effect at all. Lancee, for example, runs panel regression predicting ISEI scores and finds that for men in particular, “bridging social capital improves both access to and performance on the labor market: it increases the likelihood of being employed, occupational status and income. Bonding social capital was not found to be effective” (2012, p. 133). Looking into employment chances, Kalter (2006) shows that the gap between immigrants and their offspring with a Turkish background and Germans of native descent that remains after controlling for educational degrees narrows substantially – and is no longer statistically significant – when social ties with Germans of native descent and German language skills are taken into account.

The studies by Lancee and Kalter are both based on data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), but evidence has also been provided using other data sources. Koopmans came to similar conclusions in a recently published study based on data from the EURISLAM project, a survey that was conducted among Muslims in six European countries. According to this study, the disadvantage for children of immigrants in terms of higher unemployment disappears after taking into account socio-cultural variables. Most importantly, friendship and family ties to people of native descendant – for women – language skills improve the chances of being integrated into the labour market (Koopmans, 2016, p. 207ff)

As mentioned above, there is no information in the GMC about friendship ties and language skills but there are at least some hints in the findings presented in this chapter that the mechanisms described in the studies by Lancee, Koopmans and Kalter do in fact play a role. As already seen, the share of immigrating Turkish women without any educational attainment has increased – rather than decreased – over time, most likely due to selective immigration of rather low-skilled women from Turkey. This may be one reason why the children growing up in those households may still have a struggle succeeding in the labour market. Even though the share of those German-born individuals with a foreign background leaving school without any diploma declined between 2000 and 2012, many can be expected to come from households that offer only limited access to majority networks and limited opportunities for acquiring fluent language skills. According to a study by and Kristen, the share of Turkish families that speak German at home is still small (18%), and the share of those speaking only or mostly Turkish at home is large (39%) (Dollmann and Kristen, 2010, p. 133). As a consequence of selective immigration of individuals with low or no educational attainment, combined with a high share of households not speaking German at home, the children of Turkish immigrants may not have the necessary language skills to compete with Germans of native descent – not even with those who have low educational degrees themselves. Recent studies confirm that Turkish offspring who were born in Germany lag behind in terms of their German language skills (Olczyk et al., 2016, p. 58).

Integration of the children of immigrants still reflects the “guest worker” legacy that was characterised by low-skilled labour migration and followed by family reunification. Nevertheless, the offspring of Turkish and Yugoslav immigrants have caught up substantially in the education system and in the labour market. Fewer German-born children of immigrants have left general secondary school without any diploma, and more are ready to enroll in different kinds of tertiary education than in their parents’ generation. In terms of entering the labour market, the biggest challenge falls to the large share of children of Turkish immigrants leaving school with the lowest possible diploma, the Hauptschulabschluss. Through processes of intergenerational transmission, the educational attainment of the children of Turkish immigrants overall still lags behind that of Germans of native descent.

A closer look at both groups’ employment and occupational status shows a similarly ambivalent picture. More children of immigrants are active in the labour market or involved in some sort of vocational training than their parents’ generation, and generational change was particularly strong among females. In a similar vein, the occupational status of those born in Germany is on average higher, though still lower than for Germans of native descent. The gap in labour market integration between those two groups is to a large extent explained by group-specific educational endowments. However, and in line with previous findings, the analyses here revealed that the children of Turkish immigrants still have a slightly lower occupational status than Germans of native descent with comparable educational degrees. Furthermore, a data comparison from 2000 showed that this gap has increased rather than decreased over time, especially for males of Turkish parents.

Ethnic discrimination may offer a seemingly obvious explanation for this persistent disadvantage. Persons with Turkish parents are less accepted than other groups according to survey data, and audit studies have found unequal treatment on housing and labour markets. The impact of prejudice and discrimination on labour market outcomes is, however, difficult to assess. For example, several studies find that Turkish immigrants and their children no longer differ from Germans of native descent once they have achieved German language skills and social ties to Germans without a migration background (Kalter, 2006; Koopmans, 2016; Lancee, 2012). An explanation that not only accords with much recent literature but also finds some support here focuses on “under-equipment” in terms of social and cultural resources – most importantly, social ties to Germans of native descent and good German language skills. The chapter’s finding that the share of Turkish immigrant women without any educational diploma increased between 2000 and 2012 suggests that ongoing marriage migration did little to improve the overall integration of these immigrants. Children growing up in these families can be expected to face disadvantages similar to those of children of German descent growing up in families with low levels of education. But on top of that, they also have to deal with specific disadvantages stemming from the migration background, such as growing up in a non-German-speaking household and having fewer opportunities to make friends with Germans of native descent. In other words, the family environment in which these children’s integration processes evolve may be characterised by few opportunities to speak German and socialise with Germans of native descent. Further research needs to look into this potential downside of ethnic replenishment triggered by low-skilled marriage migration from Turkey. Even though this did not hamper the children’s educational progress (their attainment increased between 2000 and 2012 – see Figure 3.1), it may have slowed down their social integration and thus also hampered their labour market integration.

The processes leading to persons with a Turkish migration background – even the offspring – having fewer language skills and social ties to Germans with native-born parents are linked to dynamics that are difficult to change because they take place within families and are also related to ethnic segregation in schools and neighbourhoods. On top of these dynamics specific to them, children with immigrant parents also face the more generic challenges of children from non-academic backgrounds, most importantly the difficulties of achieving the skills and competencies necessary for a successful educational career. Avoiding segregation and levelling out the starting conditions for children from different social backgrounds is, however, a big challenge.

There does seem to be room for cautious optimism. This chapter showed that across generations, integration is progressing for all groups. Education levels and occupational status do rise though change is at best moderate over time, and native-immigrant gaps close only slowly over time. It has been argued here that this partly reflects ongoing ethnic replenishment, i.e. immigration of low-skilled individuals form Turkey. While this trend may have slowed down Turkish immigrant families’ progress towards greater parity with natives, the trend may become less pronounced in the future. Immigration from Turkey has been very low during the past years, with on average only about 25 000 individuals immigrating to Germany annually (Statistisches Bundesamt 2015 and previous years, and own calculations). On that basis, integration processes in the education system and in the labour market could well accelerate in the near future.

Aybek, C., C. Babka, V. Gostomski, S. Rühl and G. Straßburger (2013), “Heiratsmigration in die EU und nach Deutschland: Ein Überblick”, Bevölkerungsforschung Aktuell Vol. 34/2, pp. 12-22.

Auspurg, K., T. Hinz and L. Schmid (2017), “Contexts and conditions of ethnic discrimination: Evidence from a field experiment in a German housing market”, Journal of Housing Economics, Volume 35, March, pp. 26-36, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2017.01.003 (accessed 1 October 2017).

Blohm, M. and M. Wasmer (2013), “Einstellungen und Kontakte zu Ausländern”, in Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung and GESIS-ZUMA (eds.), Datenreport 2013: Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Bonn, pp. 205-11.

BMI/BAMF (2013), Migrationsbericht des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge im Auftrag der Bundesregierung, Federal Ministry of the Interior/Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, Berlin/Nuremberg.

Diehl, C. and M. Blohm (2008), “Die Entscheidung zur Einbürgerung: Optionen, Anreize und identifikative Aspekte”, in F. Kalter (ed.), Migration und Integration: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, Special Issue 48, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, pp. 437 64.

Diehl, C., C. Hunkler and C. Kristen (2016), Ethnische Ungleichheiten im Bildungsverlauf: Mechanismen, Befunde, Debatten, VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden.

Dollmann, J. and C. Kristen (2010), “Herkunftssprache als Ressource für den Schulerfolg? – Das Beispiel türkischer Grundschulkinder”, in C. Allemann-Ghionda, P. Stanat, K. Göbel and C. Röhner (eds.), Migration, Identität, Sprache und Bildungserfolg, Beltz, Weinheim u.a., pp. 123-46.

Granovetter, M. (1973), “The strength of weak ties”, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 78/6, pp. 1360-1380.

Hartmann, J. (2016), “Do second-generation Turkish migrants in Germany assimilate into the middle class?” Ethnicities, Vol. 16/3, pp. 368-92.

Heckman, J.J. (1998), “Detecting discrimination”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 12/2, pp. 101-16.

Kaas, L. and C. Manger (2011), “Ethnic discrimination in Germany's labour market: A field experiment”, German Economic Review, Vol. 13/1, pp. 1-20.

Kalter, F. (2006), “Auf der Suche nach einer Erklärung für die spezifischen Arbeitsmarktnachteile von Jugendlichen türkischer Herkunft”, Zeitschrift für Soziologie, Vol. 35, pp. 144-60.

Kalter, F., N. Granato and C. Kristen (2007), “Disentangling recent trends of the second generation’s structural assimilation in Germany”, in S. Scherer, R. Pollack and G. Otte (eds.), From Origin to Destination: Trends and Mechanisms in Social Stratification Research, Campus Verlag, Frankfurt, pp. 214-45.

Kalter, F. and N. Granato (2017), “Ethnische Ungleichheit auf dem Arbeitsmarkt”, in M. Abraham and T. Hinz (eds.), Arbeitsmarktsoziologie: Probleme, Theorien, empirische Befunde, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Opladen.

Koopmans, R. (2016), “Does assimilation work? Sociocultural determinants of labour market participation of European Muslims”, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol. 42/2, pp. 197-216.

Kroneberg, C. (2008), “Ethnic communities and school performance among the new second generation in the United States: Testing the theory of segmented assimilation”, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 620/1, pp. 138-60.

Lancee, B. (2012), Immigrant Performance in the Labour Market: Bonding and Bridging Social Capital, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

Lüttinger, P. and T. Riede (1997), “Der Mikrozensus: Amtliche Daten für die Sozialforschung” (“The German Microcensus: Offical statistics in social sciences”), ZUMA-Nachrichten, Vol. 41/21, pp 19-43.

OECD (2013), "Turkey", in Education at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2013-75-en.

Olczyk, M., J. Seuring, G. Will and S. Zinn (2016), “Migranten und ihre Nachkommen im deutschen Bildungssystem: Ein aktueller Überblick”, in C. Diehl, C. Hunkler and C. Kristen (eds.), Ethnische Ungleichheit im Bildungsverlauf: Mechanismen, Befunde, Debatten, Springer VS, Wiesbaden.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2015): “Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit”, Wanderungen, Reihe 1, Fachserie 1.2, Destatis, Wiesbaden.

← 1. The “children of immigrants” here refer to those who were born in Germany but hold (or held) foreign citizenship.

← 2. This group may include individuals with German ancestry who were born abroad.

← 3. Calculation of the share of immigrants’ offspring who have achieved the Abitur in 2000 is based on small case numbers though, and so needs to be interpreted with care.

← 4. Note, however, that the question about educational diplomas was voluntary for those above the age of 51 in 2000. Many individuals among those not answering this question may not have any diploma. Nevertheless, among non-naturalised Turkish females in particular, the share of those without any diploma has increased even if no diploma and no answer are collapsed into one category.