This chapter provides an overview of the key findings of an OECD project – funded by the European Commission - that analysed the links between parental disadvantage for immigrants and the outcomes of their children across EU and OECD countries, in comparison with native-born parents and their children.

Catching Up? Intergenerational Mobility and Children of Immigrants

Chapter 1. Intergenerational mobility of natives with immigrant parents

Abstract

Introduction

Ensuring equal opportunities and promoting upward social mobility for all are crucial policy objectives for inclusive societies. A group that deserves specific attention in this context are immigrants and their children, as they face multiple disadvantage and constitute an important and growing part of the EU and OECD population. Understanding the intergenerational transmission of disadvantages of migrants, in absolute and relative terms, and the conditions under which native-born children of immigrants may be resilient, is critical for evidence-based policies aiming at promoting economic growth and social cohesion. In the EU context, it is also crucial for attaining EU targets with respect to reducing school drop-out and enhancing employment rates. The present report is aiming at addressing these questions, building on new empirical, internationally-comparative analyses.

This overview chapter of the report summarises findings from the work presented in greater detail in Chapter 3 (with respect to education) and 4 (regarding the labour market), together with an extensive survey of the existing literature (Chapter 2). It also incorporates findings from background reports on specific countries and groups of children of immigrants, which will be the subject of a forthcoming OECD publication.

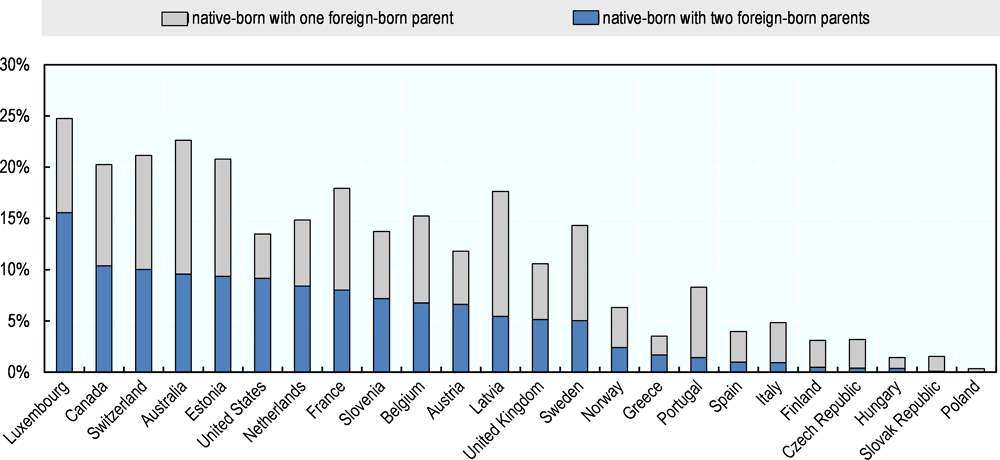

Native-born persons with two foreign-born parents – the focus group of this report - are a growing group. In the European Union, they account for 9% of all youth aged 15-34 (see Figure 1.1), but already for 11% of all children below the age of 15.1

Figure 1.1. Distribution of youth by place of birth and parents’ place of birth in selected OECD countries, 15-34, 2014

Source: OECD Secretariat calculations with data from national labour force surveys. See OECD and EU (forthcoming), Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2018: Settling In.

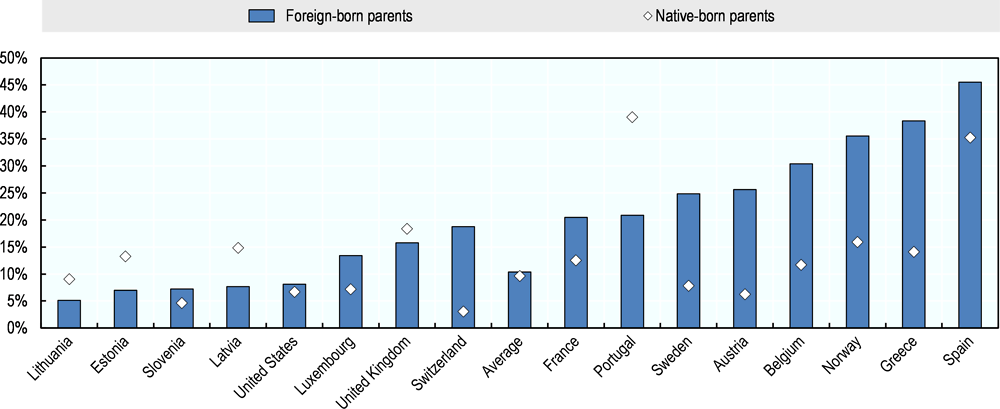

As far as EU countries are concerned, a key distinction is between those whose parents were born in another EU country and those whose parents were born in a country outside the EU, as the two groups differ in their characteristics and integration prospects.2 Indeed, there are the marked differences among the outcomes of the children of the two groups. Moreover, the distribution of these groups among all natives with foreign-born parents varies widely across EU countries, from more than 90% with parents born outside the EU in the United Kingdom and in Portugal to less than 10% in Luxemburg (Figure 1.2). As will be seen in greater detail below, children of immigrants from non-EU countries often face much greater challenges with respect to intergenerational mobility and to socio-economic outcomes than their peers with EU-born parents.

Figure 1.2. Native-born youth with immigrant parents, by parental origin, 15-34, European OECD countries, 2014

Source: OECD Secretariat calculations with data from national labour force surveys. See OECD and EU (forthcoming), Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2018: Settling In.

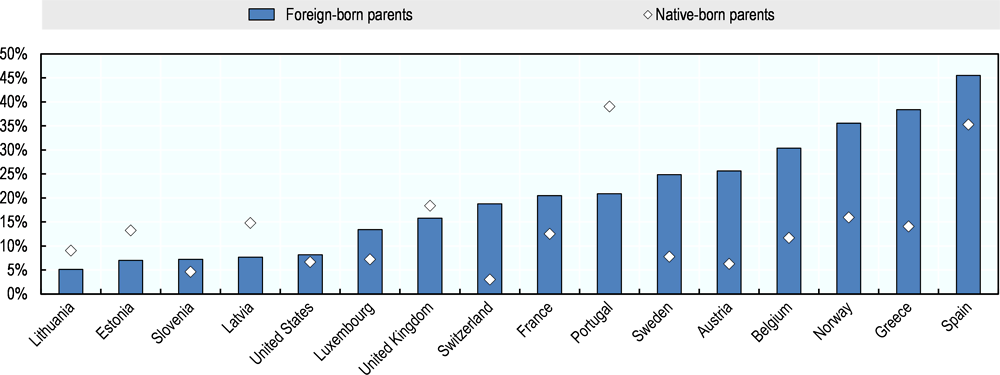

Figure 1.3. Share of low-educated native-born persons aged 25 to 34, by country of birth of parents, percentages, 2014

Source: European countries: EU Labour Force Survey Ad-hoc module 2014. United States: Current Population Survey.

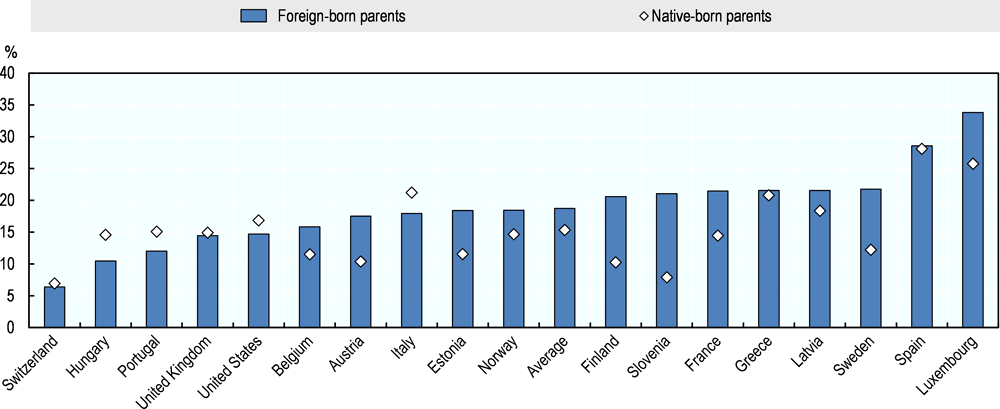

At the same time, previous work has shown that natives with immigrant parents3 remain at a disadvantage (OECD, 2010; OECD and EU, 2015). In particular, they have lower educational attainment and labour market outcomes than their peers with native-born parents in most European OECD countries (Figure 1.3), especially in those countries which experienced large-scale immigration of low-educated immigrants in the past. There are a few exceptions; however, these mainly concern countries with small populations of native-born children of immigrants and where the parents are highly-educated expatriates. A similar picture emerges with respect to the percentages of those youth who are not in employment, education or training (NEET) (Figure 1.4), which is a key indicator for youth.

Figure 1.4. NEET rates of youth aged 15 to 24, by parents’ place of birth, percentages, 2014

Source: European countries: EU Labour Force Survey Ad-hoc module 2014. United States: Current Population Survey.

To what degree are these difficulties linked with the disadvantage faced by the immigrant parents? What can one say about social progress over time for immigrant groups? There has indeed been little research on progresses over time – that is, comparing the outcomes of immigrants’ children to the outcomes of their parents – and even less on analysing the intergenerational social and economic mobility of natives with immigrant parents as compared to their peers with native-born parents. Yet the fact is that better understanding of these linkages is crucial for the design of policy instruments aimed at addressing the poorer outcomes of children of immigrants.

Intergenerational mobility refers to the link between the socio-economic status of parents on the one hand and the status their children will attain as adults on the other. Fair intergenerational mobility can be taken as a marker of equity by mitigating the widening of economic inequality across generations. It also contributes to promoting social justice, and to achieving more social cohesion.

The overview attempts to answer the following three questions:

Are natives with immigrant parents more or less socially mobile than natives with native-born parents?

What drives or hinders the intergenerational mobility of natives with immigrant parents?

Which policy instruments can promote the intergenerational social and economic mobility of natives with immigrant parents?

Key questions on the intergenerational mobility of natives with immigrant parents

Parents influence the success and life chances of their children through many channels. They transmit a multitude of resources to their children, and specificities in these transmission channels are the core reason for varying social mobility between the children of natives and those of immigrants. In particular, parents invest in their children by financing their education, or simply by spending time with them in enriching activities that are important predictors of children’s success (Waldfogel and Washbrook, 2011; Price, 2008). Parents may also transmit wealth (financial and material) through bequests or gifts. Beyond what parents invest and transmit, the future life chances of children depend on their social capital. Wealthier parents provide a different social capital to their children because of the peers that children interact with in school, and the wider network of family acquaintances and friends. Parents with a great deal of social capital can help their children in case they need support in school or need contacts in professional networks to find employment. In addition, the quality of the neighbourhood where one grows up is a key factor influencing later outcomes (see Chapter 2). Finally, parental aspirations, beliefs and attitudes may also affect family and the work outcomes of children when they are adults.

OECD work has shown that overall intergenerational social mobility is considerable: with the global expansion of educational opportunities seen in the past few decades, many individuals have achieved a higher educational level than their parents. Globally, about half of non-student adults (25-64 year-olds) have had a different level of education than their parents, with upward mobility almost four times more common than downward mobility (OECD, forthcoming b).4

1. Are natives with immigrant parents more or less mobile than natives with native-born parents?

The degree to which parents transmit their educational and social capital has been widely argued to be a key factor affecting people's educational achievement later in life. While parental human capital is generally correlated with their children’s success (usually defined as educational attainment, income, or occupational status), immigrant parents are often at disadvantage compared to the native-born because of lack of host-country language skills, social networks, among others.

In most countries, immigrants have lower socio-economic outcomes than natives, and this impacts on the outcomes of their children.

In most EU and OECD countries, immigrants are overrepresented at the lower educational and occupational strata, with the overrepresentation strongest at the lowest levels, especially in European OECD countries. In the EU, a full 15% of natives with non-EU parents have a mother with no completed formal education, which is five times the share in the other groups. That particular overrepresentation indicates that natives with non-EU origins have a more challenging “starting point”, which could partly explain their weaker performance on the labour market.

It would thus not be surprising a priori that natives with immigrant parents have lower educational outcomes on average than natives with native-born parents. To the degree that chances in the labour market are associated with education, one would also expect this to translate into somewhat lower overall labour market outcomes. Indeed, there is ample evidence that natives with immigrant parents, and especially those with parents born outside the EU, have lower education and labour market outcomes than their peers with native-born parents.5 (See for example Ammermüller, 2005; Crul and Schneider, 2009; Heath, Rothon and Kilpi, 2008; Marks, 2005; Schnepf, 2004; van de Werfhorst and van Tubergen, 2007.) Most studies explain the gap in educational outcomes by pointing to differences in socio-economic background, especially parental education. Once similar individuals are compared in terms of socio-economic background, part – but far from all – of the gaps observed disappear. In the Netherlands, Crul (2017, forthcoming) finds for instance that the difference in educational outcomes is reduced by half for the children of Turkish immigrants and three-quarters for the children of Moroccan immigrants when accounting for the educational level of their parents. In Germany, the occupational status of native-born children of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia no longer differs from that of native-born children of German natives in a statistically significant way. However, small differences remain for the children of Turkish immigrants (Diehl and Granato, 2017).

While it is widely accepted that the socio-economic characteristics of immigrant parents play an important role in the under-performance of many of their native children, research suggests that the transmission of socio-economic status does not operate in the same way for immigrants as it does for majority populations (Heath et al., 2008; Nauck, Diefenback and Petri, 1998).6

Global convergence in outcomes across groups over generations

In most countries analysed, there is a convergence of educational attainment across generations. Progress is clearly visible when comparing differences across generations for both groups. On average across European OECD countries, natives with immigrant parents have on average 1.3 years’ more schooling than their parents, while their peers with native-born parents have 0.7 years. Among parents, the difference in educational attainment between native-born and immigrants is roughly 1.2 years of schooling, while among the offspring generation this difference is reduced to roughly 0.7 years of schooling. It emerges from this picture that the educational gap within the child cohort is smaller than the one observed among their parents. On average, the gap has almost halved within one generation. To sum up, there is a clear convergence in educational attainment between natives with immigrant parents and natives with native parents.

A much lower threshold to pass for children of immigrants

Not only are migrant parents overrepresented at the bottom of the educational strata, but also they are more likely to be without a job and when employed, find themselves more often in lesser-skilled occupations (OECD and EU, 2015). At the same time, intergenerational mobility is more likely for those whose parents are at the bottom end with respect to these characteristics.

It is thus not surprising that children of immigrants are on average more mobile at first sight, given that the threshold they have to pass is much lower. To shed more light on the intergenerational mobility patterns of natives with immigrant parents compared to that of their peers with native-born parents, it is crucial to compare individuals with the same starting point, i.e. with the same parental educational level. As data from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment show, the increase in educational outcomes with higher parental education levels is less pronounced for children of immigrants than for children of native-born (Chapter 3).

In sum, while there is convergence between the two groups across generations, this is driven by general educational progress from which immigrants benefit disproportionately, since they have on average a lower starting point and are thus more likely to experience upward mobility.

Intergenerational transmission of disadvantage: stronger for immigrants

What is worrying is that in many European countries, natives with low-educated immigrant parents have a lower probability of completing medium-level or higher education, as compared to natives with equally low-educated native-born parents. It is true, though, that this effect is weaker for younger generations (under age 40), indicating an improvement in upward mobility in the recent past.

Also worrying however is that in Europe, higher parental education translates less into higher labour market chances for the children of immigrants than for the children of natives. The native born with low-educated parents of non-EU origin have roughly the same employment probability as their peers with low-educated native-born parents. However, having parents educated at a medium level increases the employment rate for natives with native-born parents by 10 percentage points, while the rate increases only by 5 percentage points for peers with non-EU parents. The picture is broadly the same for those with highly educated parents.

Natives with immigrant parents less likely to enrol in tertiary education

Generally, for both the offspring of immigrants and offspring of the native born, children whose parents are not highly educated have limited chances of enrolling in tertiary education. While children whose parents did not attain upper secondary education have only a 15% chance of having tertiary education, on average across OECD countries they would have been four times more likely to go to university if at least one parent had attended tertiary education. Differentiating within tertiary educational attainment and looking only at the highest levels yields even more striking results. The likelihood of having at least a master’s degree when parents have lower secondary education or less is as low as 3%. That likelihood is multiplied by four if parents have upper secondary education, and multiplied by seven if parents have already had tertiary education.

At the same time, there little chance of downward mobility for those with more highly educated parents. Children from more educated families are six times less likely to drop out from school at lower secondary level or before than students whose parents have a lower educational background.

An interesting finding is that natives with immigrant parents who do enrol in post-secondary education are less likely to do so in the academic tracks, but rather enrol in vocational education and training (Chapter 3). This holds even after controlling for the parents’ education.

A gap in employment rates that decreases with the level of educational attainment

The findings from the literature and from Chapter 4 clearly show that even when individuals have similar parental educational levels – that is, after controlling for parental educational attainment – still it is the natives with non-EU parents who experience weaker labour market outcomes and more difficulties in obtaining good jobs requiring high levels of skills. However, there are large variations among immigrant groups and between genders. For example, in France (Beauchemin, forthcoming), the unemployment rate of sons of Algerian immigrants is almost twice as high compared to that of the male mainstream population seven years after the end of their initial studies (27% and 14%, respectively). This gap is even larger between the daughters of Turkish immigrants and women with native-born parents, with unemployment rates of 44% and 16%, respectively. Multivariate analyses show that part of these gaps remain after controlling for individual and family characteristics, especially among those of non-European origin. This indicates that there are potentially other factors that natives with non-EU origins in particular need to overcome, and that could in turn partly explain their (weaker) performance on the labour market. Such unexplained differences may be due to institutional differences in a given context, selective screening by employers, or other factor such as fewer networks and knowledge about labour market functioning.

Chapter 4 also shows that natives with non-EU origins who complete higher education have a much lower employment gap in comparison with natives with native-born parents than those with lower educational attainment. Low-educated natives with parents born outside the EU have a 12 percentage points lower probability of being in employment than their peers with native-born parents. This employment gap reduces to 10 percentage points for those with medium-level education and to 6 percentage points for those who completed higher education. While a person’s own education is a big driver for labour market outcomes generally, it has an even stronger impact on the labour market outcomes of children with immigrant parents.

The ongoing greater difficulty in achieving upward mobility towards a high-skilled job

Natives with parents born outside the EU experience less occupational upward mobility than their peers with EU origins or with native-born parents. About a third of natives in the latter two categories manage to move upward on the occupational ladder; for natives with parents born outside the EU, only 1 in 5 manages to find work in an occupation requiring a higher skill level than his/her father needed in his occupation. Moreover, evidence from the country reports (OECD, forthcoming) clearly shows that having a high education level translates less often into high-skilled occupations for children of immigrants. These findings indicate that the top end of the labour market is the most difficult to reach for the children of immigrants.

The stronger negative effect having low-educated parents on the labour market performance of natives with immigrant parents

Comparing individuals with similar parental education levels reveals that having low-educated parents is associated with less upward mobility for natives with immigrant parents than for their peers with native-born parents. Having low-educated parents also has a stronger negative effect on the labour market chances of natives with immigrant parents than for their peers with native-born parents, especially for those with parents born outside the EU. To be more precise, natives with low-educated parents born outside the EU have a lower probability of being in employment than their peers with the same age, education and gender but native-born parents, with some heterogeneity by country. In Austria, Switzerland, Spain, France, Norway and the United Kingdom, their employment gap ranges between 5 and 10 percentage points. In Belgium, natives with low-educated parents born outside the EU have an 18 percentage points lower probability of being in employment compared to natives with native-born parents.

There are several possible explanations for this. First, within the group of low-educated immigrant parents, immigrant parents find themselves disproportionately often among the very low educated. Also, low-educated immigrant parents have lower income than their native peers (OECD and EU, 2015). They may thus be less able to invest in their children's human capital. Poverty risks, joblessness and a lack of basic education are therefore likely to accumulate and result in a larger share of individuals at higher risk of social exclusion. Language obstacles further exacerbate the issue. Finally, as Chapters 2 and 3 show, there is compelling evidence of a detrimental effect of the observed high concentration of children with low-educated immigrant parents in schools on overall education outcomes.

Highly educated immigrant parents less likely to transmit their advantage to their children

At the same time, highly educated immigrants often are not able to transmit their high “status” to their children. This phenomenon, known as perverse social mobility, is prevalent in many countries (see Heath, forthcoming). There are several possible reasons for this. First, there is ample evidence that the qualifications of immigrants themselves are largely discounted on the labour market of host countries, especially if these have been acquired abroad. Thus, highly educated immigrant parents are less likely to be in high-skilled jobs. But, even when foreign-born parents are employed in high-skilled jobs, they are less likely to transmit this advantage to their children than native-born parents. This results in a higher likelihood of downward occupational mobility for individuals with foreign-born parents that were occupied in high-skill jobs.

The children of immigrants’ own education: a strong driver for labour market advancement

While overall there is a weaker link between parental education and labour market outcomes of their children for immigrants from non-EU countries at given education levels of the children, the children’s own education level matters greatly: the higher the education level, the lower the gap in employment rates between those with and without immigrant parents. In other words, education is a stronger driver for the labour market integration of children of immigrants than for the children of the native born.

The strong association of immigrant mothers’ labour market status with the outcomes of their children, especially for the daughters

Immigrant mothers’ labour market participation seems to have an important impact on the outcomes of their children, more than for the latter’s peers with native-born parents. While this is observed for both genders, the association is particularly strong for women whose parents came from non-EU countries. Having had a working mother at age 14 (as opposed to a mother staying at home) increases the employment probability for natives with non-EU parents by 9 percentage points, more than twice the number for their peers with native parents at 4 percentage points.

The strong likelihood of low-educated mothers with immigrant parents staying out of the labour force

Not only do native-born women with immigrant parents have overall lower employment rates, but evidence from several countries (OECD, forthcoming) also shows that these women are more likely to quit a paid job upon the birth of their first child than women with native parents. An important factor in their decision seems to be the cost of child care – the more expensive it is, the more likely that the woman’s (expected) salary amounts to less than the cost.

The strong performance of children of EU mobile citizens

An interesting and robust finding, that holds for both education and labour market outcomes, is that native-born children of mobile citizens (i.e. those with EU-born parents) often perform better than their peers with native-born parents. This is particular noteworthy since the issues faced by their parents are often similar to those faced by immigrants from non-EU parents – including a low education level of many parents. The stark contrast in the intergenerational mobility patterns between the two groups merits further investigation.

Averages hiding significant heterogeneity between genders and across parental origin groups

Country reports prepared in the context of this project (OECD, forthcoming) looked into specific groups, and these revealed interesting group and gender aspects. In particular, daughters of immigrant parents appear to fare well in the education systems and thus show generally high levels of educational mobility. They often attain a higher level of education than their brothers and indeed the highest level of education in their families. In both Sweden and the Netherlands, the daughters of Moroccan immigrants stand out as displaying exceptionally high levels of upward mobility. This shows that low average levels of human capital in the respective parental communities – as has been the case for the Moroccans – have not per se impeded educational advancement. In Canada and the United States, children of immigrants from Asian countries outperform their peers with native-born parents in the education system, while this is not the case for children of immigrants from South America.

Yet, as discussed above, success in school does not always translate into success in the labour market, especially among girls. An even wider gender gap appears among the low educated, where low educational attainment among women frequently leads to inactivity on the labour market. In the Netherlands for example, among those with low educational attainment, men with Turkish and with Moroccan origins have participation rates that are twice those of their peers who are women.

Even among the group of men with relatively low-educated non-EU parents, there are important differences. In particular, native-born men with parents from the former Yugoslavia have performed relatively well in terms of both education and labour market outcomes. On the one hand, this suggests that resilience is possible; at the same time, it shows that the outcomes for other groups are worryingly poor. An important question for further investigation is the degree to which the more favourable results of groups like those with parents from the former Yugoslavia may be linked with parental educational attainment and reason for migration. .

Scant evidence regarding those with immigrant grandparents suggesting the issues are persisting

There is very limited information on those whose grandparents have immigrated. Only two countries have both register data that allow for the identification of this group, and sufficiently large numbers to be able to study them in detail. They are Sweden and Belgium, and in both countries the evidence suggests that while the gap continues to close, some disadvantage is persisting across generations. In Belgium, the 2017 socio-economic monitoring (SPF Emploi, Travail et Concertation sociale and UNIA, 20175), has yielded some basic figures on the integration of native-born youth with two parents with Belgian nationality at birth and at least one grandparent with a foreign nationality at birth, on the basis of linked register data. These show, for example, that the unemployment rate among those native-born who have at least one parent holding a non-EU nationality at birth is about three times higher than for those with two Belgian parents and four grandparents that were born with Belgian nationality. For those with at least one grandparent with a non-EU nationality at birth, the rate is about twice as high. In Sweden, Hammarsted (2009) studied the earnings of immigrants, their native-born children, and their grandchildren relative to their peers without an immigration background. He finds that the earnings of the grandparent immigrants – who came mainly as labour migrants from other European countries – exceeded those of native Swedes. At the same time, he finds this situation reversed in the next generation, and that a gap persisted further among the grandchildren.

2. What drives or hinders the intergenerational mobility of natives with immigrant parents?

Early childhood education, later streaming, and teacher support

Early childhood education – provided that it is widely accessible, of good quality, and not segregated –can increase intergenerational mobility, and children of immigrants often benefit disproportionately. Children of immigrants who do not speak the language of the host-country at home and children with low-educated parents especially benefit from participating in early childhood education and care which provides an early immersion in the language of instruction and support that may be lacking at home (Schnepf, 2004). Immigrant parents themselves can also benefit from ECEC institutions, which often provide additional services such as health monitoring and helping parents access other available social support services. However, children of immigrants are often underrepresented in ECEC, especially at the critical period between two and four years.

Among children of immigrants at age 15, data from the 2015 OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) show that OED-wide, 41% speak a language at home that is different from that of the country in which they live. These students also underperform vis-à-vis their peers in terms of PISA reading scores. Research further indicates that streaming into less prestigious tracks is often linked not only with the students’ skills but also with their socio-economic background, and this disproportionally affects children of immigrants. Lastly, teacher skills and attitudes towards children of immigrants matter.

Parental aspirations, language skills and system knowledge

Parental support is key for children to succeed in school and beyond, and yet many parents are not sufficiently engaged in their children’s schooling. While this may be primarily a socio-economic and not an immigrant issue per se, immigrant parents often face additional challenges such as language barriers and lack of knowledge about the functioning of the education system and the labour market. In addition, again because of language barriers, they may be more hesitant in interacting with teachers and thus less able to intervene on time when their child needs support at school. Especially parents with a low level of educational attainment may be less able to assist their children at home, or may feel uncomfortable when interacting with teaching staff in school settings (see Chapter 2).

Evidence further suggests that the greater number of years that parents have spent in the host country prior to giving birth positively affects educational outcomes of their children, mostly due to parents’ better language skills (Worswick, 2004; Nielsen and Schindler Rangvid, 2012; Smith, Helgertz and Scott, 2016). When parents speak the language of the host country on a good level, this is likely to positively impact their children’s educational attainment, and even more so when their children are still young. Parents’ familiarity with the education system is likely to have an impact on how well they can support and guide their children through an educational career, particularly when parents can choose their children’s schools or have to make decisions regarding school streams early on. Thus, a lack of such knowledge can become a mechanism that reinforces the association between parents’ and children’s attainment.

Educational aspirations among immigrant parents and their children are generally found to be high (see e.g. Beauchemin, forthcoming). Results from the OECD PISA also reveal that most immigrant students and their parents have ambitions for the child’s success that often exceed the aspirations of native families. For example, parents of immigrant students in several countries are more likely to expect that their children will earn a university-level degree than the parents of students without an immigrant background. When comparing students of similar socio-economic status, the difference between those with and without a migration background in terms of their parents’ educational expectations for them grows even larger. This is important, as students who hold ambitious yet realistic expectations about their educational prospects are more likely to put effort into their learning and make better use of the opportunities available to them to achieve their goals. High educational aspirations are an important prerequisite for overcoming initial disadvantage and thus for resilience. However, high aspirations need to be coupled with hands-on knowledge to turn these goals into tangible outcomes.

Concentration of disadvantage in neighbourhoods and schools

There is ample evidence that growing up in a poor neighbourhood has negative effects on labour market outcomes. Less is known about the extent to which a high concentration of immigrants in a given neighbourhood impacts the mobility of natives with immigrant parents. Literature that has aimed at capturing immigration-specific factors of residential segregation shows that its impact strongly depends on the – often group-specific – economic and social resources of immigrant communities.

Likewise, findings from the OECD PISA suggest that children of immigrants are everywhere highly concentrated in a small number of schools. Interestingly, it is not the concentration of children of immigrants per se in schools that seems to matter, but rather the interaction of such concentrations with the low education of parents. In Europe the two often coincide (i.e. there is a high concentration in schools of low-educated immigrant families); this is less the case in OECD countries that were settled by immigration, such as Canada (Lemaître, 2012).

Networks

The transition from school to work has been highlighted in the literature as a critical point for natives with immigrant parents, who are often less successful in finding employment. In most countries, these differences are not explained by differences in educational attainment. Fewer networks may be a factor that limits school-to-work transitions for natives with immigrant parents, particularly if their parents cannot provide them with useful contacts. Indeed, especially for the first foothold in the labour market, parental support and networks are often crucial.

Concentrations of both immigrants and their children in certain occupations and sectors may also hinder social mobility in the labour market. Detailed analysis of how the children of immigrants are distributed across occupations, and the extent to which this links with their parents’ occupations, is still limited.

Discrimination

Discrimination is an often underestimated obstacle for intergenerational mobility. Testing studies using fake CVs show that it is not uncommon for native-born persons with a foreign sounding-name to write three to four times as many applications as otherwise similar persons with a “host-country” name to be invited to a job interview. Native-born youth with immigrant parents are more highly aware of, and less likely to accept, such discrimination than their immigrant parents, at least in European OECD countries (Heath, Liebig and Simon, 2013). This may hamper their identification and engagement with the host country, with negative implications not only for social mobility but also for wider social cohesion. It is also worth noting that children of immigrants seem to react at least in part to discrimination by sending more CVs than their peers with native-born parents.

3. What role for policy?

While policy measures aimed at improving the situation of youth in general will also reach out to and support natives with immigrant parents, targeted policy measures may be necessary to address some of their specific challenges. For example, natives with immigrant parents have often grown up in an environment where parents have less information about labour market functioning in the host country or access to networks that may help in finding a first job. In addition, evidence from a number of OECD countries suggests that active labour market policies often have different effects on immigrants than on the native born (OECD, 2014). The degree to which this extends to their native-born children is, however, unclear. While wage subsidies have proved to be quite effective for immigrants’ access to regular employment in several countries, instruments like apprenticeship subsidies could play a similar role for disfavoured children of immigrants.

That said, few countries have specifically targeted policies for native-born youth with immigrant parents. Indeed, such specifically targeted labour market measures may risk increasing stereotypes. However, some indirect targeting – for example, for disadvantaged youth in general – can disproportionately benefit native-born youth with immigrant parents, because they are often overrepresented among this group. Enhancing transparency and making sure that all children have the relevant information are important prerequisites for such programmes to work.

Policy lessons

Notwithstanding the caveats just mentioned, there emerge a number of policy lessons to address the challenges for upward social mobility for the children of immigrants that have been discussed in the previous section.

Supporting the integration of immigrant parents

A first clear policy implication concerns measures to help integrate immigrant parents, by providing education and training where appropriate and more generally by supporting labour market integration. This will have an important spill over effect on the outcomes of their children, which will be particularly strong in the case of women. Involving and supporting immigrant parents – especially mothers, who are often a blind spot in the integration offers of OECD and EU countries (OECD, 2017) – is thus a necessary and important first step towards achieving upward mobility for their children. At the same time, immigrant parents need to be encouraged and empowered to better follow the educational advancement of their children. In this context, the issue of access to and participation in ECEC for children with low-educated immigrant mothers should receive particular attention.

Upward mobility through early intervention and promoting excellence

Increasing access to early childhood education with a specific focus on disfavoured children with language obstacles not only would allow the mothers to enter the labour market, but also would likely provide high returns for the children themselves – as demonstrated by evidence from a number of OECD countries. Many OECD countries have specific policies in place to help children of immigrants with language obstacles, often based on systematic language screening in pre-school coupled with follow-up remedial training (see the policy overview at www.oecd.org/els/mig/Policies-to-foster-the-integration-of-young-people-with-a-migrant-background.pdf).

Fostering intergenerational mobility for children of immigrants also means promoting excellence. Higher education is a turning point to ensure equal opportunities in working lives. Improving access to top schools remains important because the institutions and courses attended are determinants of success. Elite schools are biased against low-income students, mostly because of costs in some countries but also because they often require specific preparation. With little information and few resources, some youth prefer to attend shorter post-secondary courses or go to less demanding schools because of the quicker path to entry-level jobs, even if they offer lower labour market prospects. Policies aimed at addressing this include so-called “contextual admission” by universities, which avoids situations where high-potential candidates with a disfavoured background do not pass the initial screening (see e.g. Mountford-Zimdars, Moore and Graham, 2014). For example, students who are flagged through contextual admissions are given additional consideration and will not be rejected solely on the basis of their predicted or actual grades, or will be guaranteed an interview or similar additional opportunity depending on the discipline.

Initiatives in OECD countries in this respect include the French programme “Pourquoi Pas Moi”, initiated by ESSEC Business School and now available in several other top universities (Cordées de la Réussite). This is a mentoring programme for high school students and workshops. Some 90% of participating students pursue tertiary education compared with the average of 75%, and members are twice as likely to attend a top school (Accenture, 2012). A similar initiative in the United States, the College Coach Program (CCP) implemented in twelve Chicago public high schools, helped students go through the college application process. Participants were 13% more likely than those without coaches to enrol in college and were 24% more likely to attend a non-selective four-year college than a two-year college (Stephan and Rosenbaum, 2015). While both initiatives do not target children of immigrants specifically, they do target children from disadvantaged backgrounds, among which children of immigrants are often overrepresented.

Overall, for individuals who were born in a given country, the education system has the potential to mitigate socio-economic disadvantages and its intergenerational transmission. Well-functioning schools, quality teachers, and targeted support all contribute to a better school environment (OECD, 2015). Educational attainment is an important outcome to be considered, but the issues that students from disadvantaged backgrounds face, that begin long before education is about to be completed, are likely to have long-term consequences. In other words, countries unable to mitigate the impact of socio-economic background during compulsory education and before may face greater challenges in ensuring equal opportunities for all once students enter the labour market. Since children of immigrants often end up in the lower streams of the education system and have less parental guidance and fewer role models, it is particularly important to have sufficient upward permeability in the educational system that allows students to move into more prestigious streams of secondary education or to access higher education.

Combating discrimination and promoting diversity

Most OECD countries have taken measures to combat discriminatory hiring practices, although the scale and scope of the measures vary widely. The most common measure to combat discrimination is legal remedy. Many OECD countries have, for example, implemented non-discrimination legislation and established agencies responsible for monitoring its application. In the OECD countries that were settled by migration, such as Australia, Canada and the United States, such legislation dates back several decades. In the European Union, an important impetus has come from Racial Equality Directive 2000/43/EC.

Several OECD countries have also tested equal employment and affirmative action policies. Such policies go beyond imposing penalties on discriminatory acts and have attempted to “level the playing field” by removing barriers that hamper access to the labour market and professional upward mobility. Often they are based on targets, although hard quotas are rare. Some countries, such as Finland, France, Germany and Norway, have tested anonymous CVs. Evidence suggests that these tools, if carefully designed and monitored, can be effective in tackling discriminatory hiring practices (Heath, Liebig and Simon, 2013).

A growing number of OECD countries have adopted diversity policy instruments. France, for example, provides companies with the possibility of passing an audit as to whether or not they use fair hiring and promotion practices. If enterprises satisfy six criteria, they can obtain a diversity label (label diversité) from the French Government. The criteria include: a formal commitment by the enterprise to diversity; an active role of the social partners within the enterprise; equitable human resource procedures; communication by the enterprise on the question of diversity; concrete public measures in favour of diversity; and procedures to evaluate actual practices. Along similar lines, Belgium grants specific diversity awards to employers with diversity-friendly company structures, and Canada helps employers meet the challenges of a diversified workforce by providing diversity training and support in developing inclusive hiring practices and retaining newcomers. At the EU level, a growing number of countries have introduced “diversity charters” in which signatories commit themselves to pro-diversity recruitment and career management practices. Likewise, there is the recent EU initiative “Employers together for integration”. However, there tends to be an element of self-selection with already committed enterprises being more likely to sign (Heath, Liebig and Simon, 2013; OECD, 2008; OECD, 2007).

In general, a considerable part of the effect of policy measures stems from raising awareness about the issue rather than through the direct influence of a particular policy on reducing discrimination or promoting equal opportunities. This is particularly relevant where legal constraints are concerned. Evidence shows that discriminatory behaviour does not always stem from individual preferences; it often arises from negative stereotypes about immigrants and their children, suggesting that a balanced public discourse on immigrants and their integration outcomes is conducive to combating discrimination (Heath, Liebig and Simon 2013). Moreover, immigrants can signal to employers their willingness to integrate through voluntary activities or other initiatives highlighting their social commitment to the host country society. Evidence from a fictitious job application study in Belgium, for example, finds that pro-social engagement not only lowers but also eradicates hiring discrimination against immigrant candidates. While non-volunteering native candidates received more than twice as many job interview invitations as non-volunteering immigrants, no unequal treatment was found between natives and immigrants when they revealed volunteering activities (Baert and Vuljic, 2016).

The promotion of diversity also implies tackling the issue of segregation in neighbourhoods and schools. While there does not seem to be a silver bullet here, a mix of policy interventions including both housing and education policy instruments that aim at avoiding concentration of disadvantage is certainly needed.

Counselling and mentorship

As mentioned, individuals with immigrant parents tend to have fewer networks and knowledge about labour market functioning. Policy can help to overcome this, for example through better counselling. Mentorship programmes have been highly effective in a number of countries and increasingly so with respect to recent arrivals, but they could also be used to overcome such obstacles for the children of immigrants who face similar issues, even for those who are native born. Such measures could also have the important side effect of promoting social cohesion at large.

The public sector as a role model

While the public sector, and in particular the public administration – due to the nature of the jobs – is often not an option for adult immigrants, it can play an important role in integration and in supporting intergenerational mobility for their children. This not only extends their career options but also generates a range of additional benefits. First, the presence of public servants with migration background enhances diversity within public institutions and contributes to a better understanding of the needs of immigrants and their children. Second, the ways in which the wider public perceives children of immigrants depend on their ‘visibility’ in public life and the contexts in which they become ‘visible’. Where civil servants with a migrant background act as teachers, police officers, or public administrators they demonstrate that immigrants are an integral part of society, and act as role models to other native-born youth with immigrant parents. Finally, by pro-actively employing children of immigrants, the public sector serves as a role model to private sector employers.

Indeed, this is an area where countries have been particularly and increasingly active, and about a dozen of OECD countries have policies in place to promote the employment of children of immigrants in the public sector (see the policy overview at www.oecd.org/els/mig/Policies-to-foster-the-integration-of-young-people-with-a-migrant-background.pdf). There is a wide range of tools targeted at children of immigrants, ranging from information and advertisement campaigns such as in Germany, to broad-based policies in the Scandinavian policies which oblige public employers to make particular recruitment efforts with respect to this group. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, have long-standing affirmative action policies which target disadvantaged youth in general.

Conclusion

A better future for their children is a key goal of many individuals deciding to migrate to a different country. Immigrants themselves face many obstacles in the labour market that are linked to the fact that they lack certain host country-specific skills, networks and knowledge. They are often willing to accept the resulting disadvantage in the labour market that is manifest in many indicators, with the hope of a brighter future for their children who should not face the same issues since they are raised and educated in the host country. Indeed, the degree to which native-born children of immigrants enjoy upward social mobility and have outcomes similar to their peers with native-born parents is rightly considered to be the litmus test of the long-term success of integration policy.

The good news in this respect is that clearly, native-born children of immigrants face lower gaps vis-à-vis their peers than their parent’s generation, with respect to both the education system and the labour market. What is worrying however is the fact that this is driven by the overall intergenerational social mobility of those with low-educated parents, and this is a group where immigrants are often strongly overrepresented. At similar starting points, children of immigrants from non-EU countries experience lower upward mobility than their peers with native-born parents. A puzzling result is that the reverse is the case for those with EU-born parents. For these, integration is a clear success story from an intergenerational perspective – which is good news for the integrated European labour market and for EU mobility at large.

The fact that there are persisting obstacles that seem to prevent a similar success story for those with non-EU-born parents – in spite of evidence of high motivation – merits particular policy attention, not least because this is a growing group virtually everywhere. At the same time, there is significant heterogeneity. In most EU and OECD countries, female children of immigrants outperform their male peers in the education system, while the reverse is the case in the labour market. And the children of immigrants from certain regions of origin seem to face more difficulties than others – a pattern that holds both across countries in Europe and in North America, in spite of very different contexts and groups concerned. While this points to the fact that the obstacles can be overcome, it also shows that for some groups the situation is even worse than what the average suggests, especially among men for whom intergenerational mobility in the education system is particularly low. Worrying also is the scant evidence that suggests that for those whose grandparents have immigrated, some of the disadvantage seems to persist among the grandchildren (that is, they have lower outcomes than their peers with native-born grandparents) even if the situation clearly improves across generations. However, more research on this question is clearly needed. Part of the answer seems to lie in addressing the issue of discrimination, including that of the institutional kind, which is an underestimated problem in both education and the labour market. Tackling the concentration of disadvantage in neighbourhoods and schools with strong immigrant presence is another line of action, although these issues are often particularly difficult and costly to address.

Ultimately – and this is the perhaps most important finding of the study – investing upfront in the integration of immigrant parents entails intergenerational payoffs. It can thus be a long-term investment, not only with respect to better tapping into the potential of children of immigrants, but also with respect to social cohesion. A key role here is played by immigrant mothers, who are often neglected in integration efforts. Helping both parents to be fully and autonomously functional in the host country society is an important precondition for better outcomes of their children, who are after all a growing part of the future of OECD and EU societies.

References

Accenture (2012), “Une grande école : pourquoi pas moi? Un programme qui fait bouger les lignes”, ESSEC and Accenture Foundation, https://www.accenture.com/fr-fr/company-etude-sroi-mecenat-competences-acn-pqpm.

Ammermüller, A. (2005), “Poor Background or Low Returns? Why Immigrant Students in Germany Perform so Poorly in Pisa”, ZEW - Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper No. 05-018, https://ssrn.com/abstract=686722 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.686722.

Baert, S. and S. Vujic, (2016), “Immigrants Volunteering: A Way Out of Labour Market Discrimination?”, IZA Discussion Paper, no. 9763, http://ftp.iza.org/dp9763.pdf.

Beauchemin, Cris (forthcoming), “Intergenerational mobility outcomes of French natives with immigrant parents”, in OECD Catching Up? Country Studies on Intergenerational mobility and children of immigrants, OECD Publishing, Paris (forthcoming).

Crul, M. (forthcoming), “The intergenerational mobility of the native-born children of immigrants in the Netherlands: The case of Moroccan and Turkish immigrants’ native offspring”, in OECD Catching Up? Country Studies on Intergenerational mobility and children of immigrants, OECD Publishing, Paris (forthcoming).

Crul, M. and J. Schneider (2009), “Children of Turkish Immigrants in Germany and the Netherlands: The Impact of Differences in Vocational and Academic Tracking Systems”, Teachers College Record, volume 111, number 6, pp. 5-6, http://www.tcrecord.org/Home.asp.

d'Addio, A. (2007), “Intergenerational Transmission of Disadvantage: Mobility or Immobility Across Generations?”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 52, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/217730505550.

Diehl, C. and N. Granato (forthcoming), “Ethnic inequalities in the education system and on the labour market: Immigrant families from Turkey and the former Yugoslavia in Germany”, in Catching Up? Country Studies on Intergenerational Mobility and Children of Immigrants, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Driessen, G. and M. Wolbers (1996), “Social class or ethnic background? Determinants of secondary school careers of ethnic minority pupils”, Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 32, Issue 1, pp. 109-126.

Granato, N. and C. Kristen (2007), “The Educational Attainment of the Second Generation in Germany. Social Origins and Ethnic Inequality”, IAB Discussion Paper, No. 4.

Hammarstedt, M. (2009), “Intergenerational Mobility and the Earnings Position of First-, Second-, and Third-Generation Immigrants”, Kyklos International Review for Social Sciences, Vol. 62, Issue 2, pp. 275-292, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2009.00436.x.

Heath, A. and W. Zwysen (forthcoming), “Entrenched disadvantage? Intergenerational mobility of young natives with a migration background”, in Catching Up? Country Studies on Intergenerational mobility and children of immigrants, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Heath, A., T. Liebig, and P. Simon (2013), “Discrimination against immigrants – measurement, incidence and policy instruments”, in International Migration Outlook 2013, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2013-7-en.

Heath, A., C. Rothon and E. Kilpi (2008), “The Second Generation in Western Europe: Education, Unemployment, and Occupational Attainment”, Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 34, pp.211-235, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134728.

Lemaître, G. (2012), “Parental Education, immigrant concentration and PISA Outcomes”, in Untapped Skills: Realising the Potential of Immigrant Students, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264172470-8-en.

Marks, G. N. (2005), “Accounting for immigrant non-immigrant differences in reading and mathematics in twenty countries”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 28, issue 5, https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870500158943.

Mountford-Zimdars, A., J. Moore and J. Graham (2016), “Is contextualised admission the answer to the access challenge?”, Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, Vol. 20, issue 4, pp. 143-150, https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2016.1203369.

Nauck, B., H. Diefenbach and K. Petri (1998), “Intergenerationale Transmission von kulturellem Kapital unter Migrationsbedingungen. Zum Bildungserfolg von Kindern und Jugendlichen aus Migrantenfamilien in Deutschland”, Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, Vol. 44, No. 5, pp. 701-722.

Nielsen, H. S. and B. Schindler Rangvid (2012), “The impact of parents’ years since migration on children’s academic achievement”, IZA Journal of Migration, Vol. 1(6), pp. 1–23.

OECD (forthcoming a), Catching Up? Country Studies on Intergenerational Mobility and Children of Immigrants, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (forthcoming b), All Different, All Equal: Levelling the Playfields and Addressing Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2017), Making Integration Work: Family Migrants, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279520-en.

OECD (2015), Immigrant Students at School: Easing the Journey Towards Integration, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264249509-en.

OECD (2014), International Migration Outlook 2014, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2014-en.

OECD (2010), Equal Opportunities? The Labour Market Integration of the Children of Immigrants, OECD Publishing, Paris http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264086395-en.

OECD (2008), Jobs for Immigrants (Vol. 2): Labour Market Integration in Belgium, France, the Netherlands and Portugal, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264055605-en.

OECD (2007), Jobs for Immigrants (Vol. 1.): Labour Market Integration in Australia, Denmark, Germany and Sweden, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264033603-en.

OECD and EU (forthcoming), Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2018: Settling In, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Price, J. (2008), “Parent-Child Quality Time. Does Birth Order Matter?”, Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 240-265, http://dx.doi.org/10.3368/jhr.43.1.240.

Schnepf, S.V. (2004), “How Different Are Immigrants? A Cross-Country and Cross-Survey Analysis of Educational Achievement”, IZA – Institute for the Study of Labor Discussion Paper, no. 1398, http://ftp.iza.org/dp1398.pdf.

Smith, C. D., J. Helgertz and K. Scott (2016), “Parents’ years in Sweden and children’s educational performance”, IZA Journal of Migration, Vol. 5(6), pp. 1–17.

SPF Emploi, Travail et Concertation sociale and UNIA (2017), Monitoring socio-économique, SPF Emploi, Travail et Concertation sociale and UNIA, Brussels.

Stephan, J.L. and J.E. Rosenbaum (2015), “Can High Schools Reduce College Enrolment Gaps with a New Counselling Model?”, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Vol. 35, Issue 2, pp. 200–219.

Van Tubergen, F. and J. van de Werfhorst (2007), “Postimmigration Investments in Education: A Study of Immigrants in the Netherlands”, Demography, Vol. 44, pp. 883-898.

Waldfogel, J. and E. Washbrook (2011), “Early years policy”, Child Development Research, pp. 1-12, http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2011/343016.

Worswick, C. (2004), “Adaptation and Inequality: Children of Immigrants in Canadian Schools”, The Canadian Journal of Economics, Vol. 37(1), pp. 53–77.

Notes

← 1. Due to lack of data for non-European OECD countries, many empirical findings focus on EU and European OECD countries.

← 2. Children who have one parent born in the EU and one parent born in a non-EU country are classified as having EU-born parents.

← 3. This report avoids the widely used term “second generation migrant” as this term suggests that immigrant status is perpetuated across generations. It is also factually wrong, since the persons concerned are not immigrants but native-born. In OECD settlement countries such as Canada and Australia, this population is generally referred to as “second generation Canadian/Australian”. The report uses the neutral term “natives with immigrant parents”.

← 4. The macroeconomic context is important for intergenerational upward mobility. Economic growth fuels mobility because productivity growth is a fundamental factor that drives wages and living standards. Over time, improvements in overall productivity and in wage levels tend on average to make children better off than their parents.

← 5. See for example: Ammermuller, 2005; Crul and Schneider, 2009; Heath et al., 2008; Marks, 2005; Schnepf, 2004; Van de Wefhorst and Van Tubergen, 2007.

← 6. Many authors, such as Heath et al. (2008), refer to this as “ethnic penalty”.