This chapter proposes a systemic monitoring and evaluation framework for city-to-city partnerships to localise the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which combines a self-assessment framework and a set of indicators. The self-assessment framework consists of a checklist to assess the extent to which city-to-city partnerships comply with each of the ten G20 High-level principles on city-to-city partnerships. The second component of the monitoring and evaluation framework measures the progress of cities engaged in partnerships toward achieving the SDGs. By combining self-assessment and the indicator framework, the proposed framework allows for a comprehensive assessment of city-to-city partnerships and their contribution to the SDGs.

City-to-City Partnerships to Localise the Sustainable Development Goals

3. A systemic monitoring and evaluation framework for city-to-city partnerships to localise the SDGs

Abstract

A systemic monitoring and evaluation framework for city-to-city partnerships to localise the SDGs

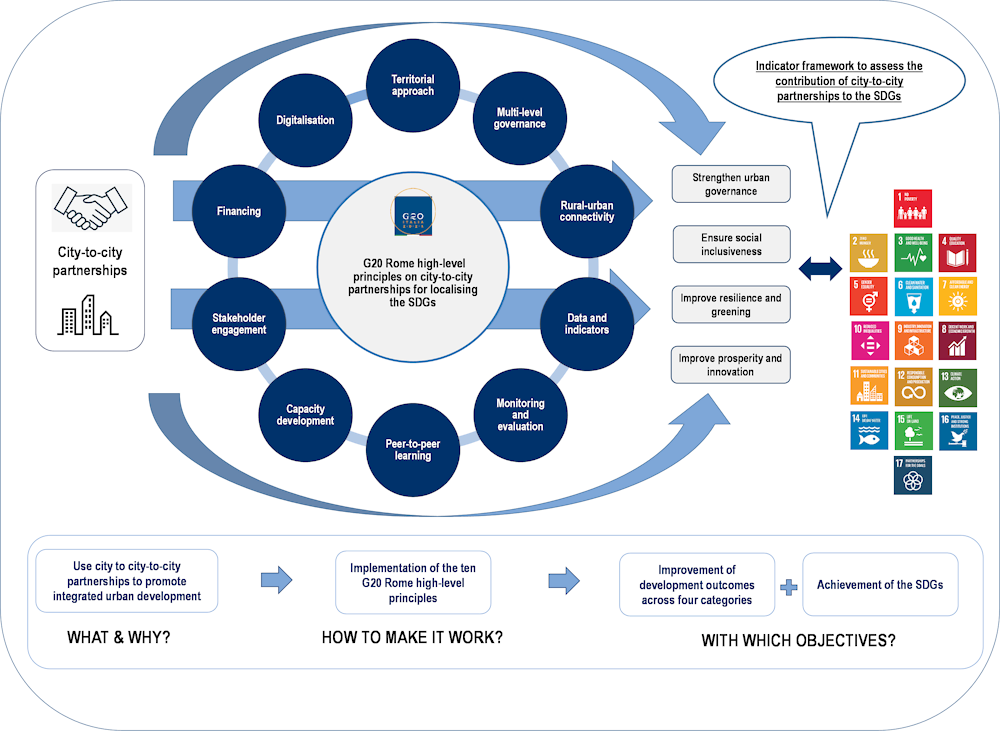

The proposed monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework for city-to-city partnerships to localise the SDGs combines a self-assessment framework and a set of indicators. Taking into consideration the ten G20 Rome High-level principles on city-to-city partnerships for localising the SDGs (G20 principles) and the four main objectives of the European Commission (EC) Partnerships for Sustainable Cities programme (hereinafter the EC Partnerships programme) (strengthen urban governance, ensure social inclusiveness of cities, improve resilience and greening of cities and improve prosperity and innovation in cities), this chapter proposes a two-component approach to evaluate the progress of cities involved in city-to-city partnerships towards achieving the SDGs and the four objectives of the EC programme. The first component, a self-assessment framework for local governments and their territorial stakeholders, aims to enable them to assess to what extent they are aligned with the ten G20 Principles on city-to-city partnerships to localise the SDGs (Box 1.2). The second component of the M&E framework is a set of indicators to assess how cities involved in city-to-city partnerships are progressing towards achieving the SDGs (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Monitoring and evaluation framework of city-to-city partnerships for localising the SDGs

The proposed M&E framework advances the assessment of city-to-city partnerships in several ways. By combining self-assessment and the indicator framework, the framework allows for a more comprehensive assessment compared to most other frameworks that either focus solely on indicators or self-assessment tools and checklists. In addition, the list of indicators considered in the framework proposes a specific focus on SDGs 11 and 17, where most frameworks have gaps in terms of indicators and data coverage.

Self-assessment framework for city-to-city partnerships to localise the SDGs

The self-assessment framework consists of a checklist to assess the extent to which city-to-city partnerships comply with each of the ten G20 Principles. The checklist is inspired by several similar OECD checklists and self-Assessment tools. These include notably the Checklist for the OECD Principles on Water Governance and its traffic light system, the Checklist for Action and scoreboard on circular economy in cities and regions, as well as the Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development Toolkit. A checklist aims to assess existing framework conditions for achieving the SDGs and sustainable city-to-city partnerships and the extent to which they are aligned with the G20 Principles. Furthermore, it should stimulate a transparent, neutral, open, inclusive and forward-looking dialogue across stakeholders on what works, what does not, what should be improved and who can do what to that effect. The proposed checklist encompasses a variety of dimensions that should enable the successful application of the G20 Principles (Box 1.2) and provide the right preconditions to enhance the effectiveness of city-to-city partnerships and their contribution to the four main objectives of the EC Partnerships programme. The checklist contains three different assessment stages: i) a preparation stage; ii) a diagnosis stage; and iii) an action stage (Figure 3.2). The OECD proposes an assessment using a five-scale evaluation (plus a “not applicable” option) corresponding to the level of implementation at the moment in which the workshop is carried out (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Self-assessment scoreboard

|

Category |

Description |

Rating |

|---|---|---|

|

In place, functioning |

The G20 principle under investigation is complete and relevant in all aspects, no major concerns are noted. |

5 |

|

In place, partly implemented |

The G20 principle under investigation is in place but the level of implementation is not complete. It might be the case that parts are explicitly lacking to make the framework complete. There might be several reasons for this, including insufficient funding, regulatory burdens, bureaucratic lengthy processes, etc. |

4 |

|

In place, not implemented |

The G20 principle under investigation is in place but it is not implemented. For example, it can be inactive or activities are of very low relevance to play a real role in possible progress. |

3 |

|

Under development |

The G20 principle under investigation does not exist yet but the framework is under development. |

2 |

|

Not in place |

The G20 principle under investigation does not exist and there are no plans or actions taken for developing it. |

1 |

|

Not applicable |

The G20 principle under investigation does not apply to the context where the self-assessment takes place. |

- |

Source: Based on OECD (2018[1]), OECD Water Governance Indicator Framework, https://www.oecd.org/regional/OECD-Water-Governance-Indicator-Framework.pdf.

This overall assessment should be split into separate sub-assessments for each of the G20 Principles. For each of the questions of the checklist for a specific principle (see below), stakeholders should have the opportunity to rate the level of its implementation/achievement based on the five-scale rating system (from 1 to 5) with one vote per stakeholder engaged in the process. Five should be the highest rating achievable and be assigned if the G20 principle under investigation is complete and relevant in all aspects with no major concerns noted regarding its implementation. Four points should be assigned in the event the G20 principle under investigation is in place but its level of implementation is not complete and some challenges have been identified. If the G20 principle under investigation is in place but is not implemented, stakeholders should assign three points. If the G20 principle under investigation does not exist yet but the framework is under development, stakeholders should assign two points. The rating should be one in the event the G20 principle under investigation does not exist in the city-to-city partnership and there are no plans and actions taken for developing it (Table 3.1). As a next step, the average rating of the stakeholders should be computed, first per stakeholder group (e.g. public administration, private sector, civil society) and then for all stakeholders. Applying such a rating system to the ten G20 Principles could reveal common and conflicting views between different stakeholder groups. It could thus also provide relevant input for the following discussion and elaboration of actions on how to improve the implementation of each G20 principle.

Self-assessment framework

1. Territorial approach. Promote city-to-city partnerships as a means to enhance the implementation of a territorial approach in responding to and recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, reducing vulnerability to climate change.

Do you use city-to-city partnerships to address concrete local challenges such as clean forms of urban mobility, affordable housing, gender equality, access to green spaces, balanced urban development, clean water and sanitation, air quality, solid waste management, territorial inequalities or service delivery?

Are the established city-to-city partnerships creating synergies across sectoral policies and plans at the local level?

Are city-to-city partnerships integrated into the local development strategy?

Do you establish city-to-city partnerships in policy areas that can help exploit the territorial development potential of the city?

Do you use city-to-city partnerships to foster territorial cohesion and recover from COVID-19?

2. Multi-level governance. Strengthen multi-level integrated governance and co‑ordination for greater effectiveness of city-to-city partnerships and for more demand-based initiatives, while considering local and regional contexts and responding to the specific needs of different geographical areas and governance systems, as appropriate.

Do the SDGs provide a framework for a more holistic and bottom-up design of your city-to-city partnerships?

Are you engaged in the process of Voluntary National Reviews?

Do you use city-to-city partnerships to strengthen vertical co-ordination with regional and national levels of government?

Are there governance arrangements and/or working practices that support effective communication on city-to-city partnerships?

Do you evaluate the benefits of your city-to-city partnerships vis-à-vis policymakers and stakeholders (e.g. reduced information asymmetries, optimisation of financial resources use, reduction/elimination of split incentives/conflicts)?

Do you receive guidance or support from other levels of government regarding the implementation and development of city-to-city partnerships?

3. Rural-urban connectivity. Enhance rural-urban connectivity, and co-operation, including between primary and intermediary cities, including through past G20 work on infrastructure.1

Do your city-to-city partnerships consider rural-urban connectivity and/or facilitate territorial co‑operation between urban and rural areas to promote an integrated development approach?

Do you assess possible economic, environmental and social gains from such enhanced rural-urban co-operation?

Do you adopt a functional approach to design policies and strategies to achieve the SDGs beyond administrative boundaries and based on where people work and live?

4. Data and indicators. Encourage local and regional governments to exchange approaches and practices in mainstreaming SDG indicators into planning and policy documents at all levels of government and produce disaggregated data towards strengthened context-specific analysis and assessment of territorial disparities in collaboration with national governments, which could also support countries in developing their Voluntary National Reviews.

Do you produce and disclose data and information on your city-to-city partnerships in a shared responsibility across levels of government, public, private and non-profit stakeholders?

Do you produce or collect disaggregated data on your city-to-city partnerships for the assessment of their contribution to the SDGs?

If you produce them, do you make data on city-to-city partnerships publicly accessible and update them regularly?

Are there mechanisms or incentives to encourage local and regional governments to exchange approaches and practices in implementing city-to-city partnerships and mainstreaming SDG indicators into planning and policy documents?

Have you agreed on key performance indicators related to your city-to-city partnerships in co‑operation with partner cities?

In addition to quantitative data, do you use qualitative information (e.g. storytelling, a community of practices) to showcase the performance and success stories of the city-to-city partnership?

Do you collect data and report on official development assistance (ODA) as part of your city-to-city partnership?

5. Monitoring and evaluation. Taking into account different national and local contexts, develop M&E indicators towards a result framework for evidence-based city-to-city partnerships, documenting their impact and providing recommendations to optimise those partnerships.

Are you subject to formal requirements (e.g. agreements on evaluation components, methodologies, etc.) for the evaluation and monitoring of the city-to-city partnership?

Have you established monitoring and reporting mechanisms for your city-to-city partnerships (e.g. joint reviews, surveys/polls, benchmarking, evaluation reports, ex post financial analysis, regulatory tools, national observatories, parliamentary consultations, etc.)?

Do you have capacity-building events to strengthen the data collection, management, storage and reporting processes?

Have you developed quantitative tools to assess the potential contribution of the city-to-city partnerships to the SDGs?

Do you share the results of the M&E process with the wider public to provide transparency and accountability?

Do you assess the level of dialogue and participation by partner organisations and local authorities in the definition, implementation and M&E of the city-to-city partnership?

6. Peer-to-peer Learning. Focus on mutual benefit, peer-to-peer learning, support and review in city-to-city partnerships, including the exchange of knowledge on sustainable urban planning and capital investment planning.

Do your city-to-city partnerships generally include a component of peer-to-peer learning?

Have you put in place knowledge-sharing opportunities across your city-to-city partnership stakeholders (city representatives, schools, civil society, private sector and academia) to exchange and learn from each other’s experiences?

Do you engage in international networks and fora to exchange best practices and learn from peer cities on city-to-city partnerships?

Do you actively reach out to peer cities via email or social media to search for new practices and innovative approaches to policy making in the framework of city-to-city partnerships?

Do you attend events (e.g. webinars) relevant to the thematic area of your city-to-city partnerships to get inspiration?

Do you consider how practices showcased by peer cities or stakeholders could be transferred to your city?

7. Capacity development. Support capacity development and build local managerial capital and skills for effective, efficient and inclusive city-to-city partnerships implementation.

Do you review and analyse the local managerial capabilities and required skills for carrying out all of the activities associated with designing, setting, implementing and monitoring the city-to-city partnership?

Based on such a diagnosis, do you offer capacity-building modules and workshops that can help address imbalances and create bridges among actors and territories with different levels of expertise and knowledge?

Are there capacity-building activities in the public service to collect and analyse evidence about the impacts of different policies implemented in the framework of the city-to-city partnership?

Do you mobilise sufficient funding to train territorial stakeholders that are involved in the partnership in the monitoring of city-to-city partnerships?

Do you collaborate with regional, national or global associations of local governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or research centres to consolidate and expand skills and competencies needed for city-to-city partnerships to deliver intended outcomes?

8. Stakeholder engagement. Engage all relevant stakeholders to implement territorial network modalities of city-to-city partnerships towards the achievement of the SDGs, including by establishing partnerships with the private sector.

Do you use the SDGs as a vehicle to enhance accountability and transparency of your city-to-city partnerships through engaging all territorial stakeholders, including civil society, citizens, youth, academia and private companies, in the policy making process?

Have you carried out stakeholder mapping to make sure that all of those that have a stake in the outcome or that are likely to be affected are clearly identified, and their responsibilities, core motivations and interactions understood?

Have you defined the objectives of stakeholder engagement and the expected use of their inputs in the city-to-city partnership?

Do you facilitate a dialogue between stakeholders on policy incoherencies or areas of disagreement regarding the city-to-city partnership?

Have you identified place-based priorities for the city-to-city partnerships through a participatory and multi-stakeholder process?

Have you put in place regular assessments of stakeholder engagement costs or obstacles at large?

Have you put in place tailored communication strategies for relevant stakeholders?

9. Financing. Call on local and regional governments to develop effective financing and efficient resource mobilisation strategies and instruments in collaboration with national governments as appropriate, through existing mechanisms to support the implementation of the 2030 Agenda through city-to-city partnerships, including by integrating the SDGs in budgeting processes.

Is there sufficient funding available to shape the city-to-city partnerships according to the needs of the local stakeholders and project partners?

Do you incentivise public-private partnerships as well as the engagement of businesses in city-to-city partnerships?

Do you use the SDGs to allocate budget across the identified priorities in your city-to-city partnerships?

Do you use financial instruments such as taxes or fees to catalyse needed revenues to implement city-to-city partnerships?

Does your local government have sufficient leeway to adjust and manage revenues to respond to the needs of city-to-city partnerships?

Do you have access to (innovative) financing tools such as green bonds, land value capture mechanisms, infrastructure funds or pooled financing instruments that include lending or de‑risking investment, such as guarantees for municipal bonds to secure sufficient funding for city-to-city partnerships?

10. Digitalisation. Develop strategies to build human, technological, and infrastructural capacities of the local and regional governments to make use of and incorporate digitalisation best practices in city-to-city partnerships.

Do you have local government strategies to build human, technological and infrastructural capacities to make use of and incorporate digitalisation best practices in city-to-city partnerships?

Do you use digital technologies, such as interactive online platforms, to encourage stakeholders to exchange information and good practices within the city-to-city partnerships?

Have you integrated specific targets related to digitalisation into your city-to-city partnerships?

Do you use initiatives or approaches that effectively leverage digitalisation to boost citizen well‑being and deliver more efficient, sustainable and inclusive urban services and environments as part of a collaborative, multi-stakeholder process?

Do you collaborate with stakeholders such as entrepreneurs, start-ups and innovative civil society organisations to find smart and digital solutions for urban development problems addressed by city-to-city partnerships?

Indicator framework to monitor the outcome of city-to-city partnerships

The second component of the systemic M&E framework measures the progress of cities engaged in partnerships toward achieving the SDGs. To complement the assessment of the application of the G20 Principles in city-to-city partnerships, the second component of the proposed M&E framework aims to quantify the progress toward the SDGs of cities engaged in partnerships. To that end, the M&E framework for city-to-city partnerships proposes an indicator framework to assess how cities engaged in city-to-city partnerships progress towards achieving the SDGs and the objectives of the EC Partnerships programme (urban governance, social inclusiveness in cities, green resilience and prosperity, innovation in cities). The indicator framework is structured according to the 4 objectives of the EC programme and composed of a range of measurable indicators for all 17 SDGs, with a particular focus on SDGs 11 and 17. The proposed indicator framework draws extensively on the analysis of existing tools, including notably: i) the OECD localised indicator framework for measuring the distance to the SDGs in cities and regions; ii) the EC Joint Research Centre European Handbook for SDG Voluntary Local Reviews; iii) the UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework; and iv) the European Environment Agency (EEA) European Topic Centre on Urban Land and Soil System report Indicators for European Cities to Assess and Monitor the UN SDGs. The proposed indicators were also mapped against the EC Global Europe Results Framework to ensure they are aligned to the largest extent possible. The proposed framework includes 59 indicators overall, composed of 2 indicators for SDG 14, 3 indicators each for SDGs 1-10, 12, 13, 15 and 16 as well as 8 indicators for SDG 11 “Sustainable cities and communities” and SDG 17 “Partnerships for goals”.

Table 3.2 presents the full list of indicators considered in the framework and proposes a simplified list with the 35 most relevant and easy-to-measure core indicators, notably for cities in developing countries. It shall provide an incentive for cities and regions engaged in partnerships to start and expand their monitoring and evaluation schemes.

Table 3.2. Long list of indicators of the systemic monitoring and evaluation framework for city-to-city partnerships to localise the SDGs

|

Indicator |

SDG |

Category of the EC programme |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

People living in households with very low work intensity |

|

Social inclusiveness |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Percentage of population with a disposable income below 60% of the national median disposable income |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of the population with access to public service provision systems that meet human basic needs including drinking water, sanitation, hygiene, energy, mobility, waste collection, healthcare, education and information technologies |

|

Urban governance |

UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework |

|

Productivity (gross value added [GVA] per worker) in agriculture, forestry and fishing (ISIC rev4) (in constant 2010 USD PPP) |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Prevalence of malnutrition |

|

Social inclusiveness |

UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework |

|

Percentage of people with access to at least 1 food shop within 15 minutes of walking |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Life expectancy |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Mortality rates for the 0 to 4 year-old population (deaths per 10 000 people) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Hospital beds rate (hospital beds per 10 000 people) |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of population from 15 to 19 years old enrolled in public or private institutions |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of early leavers from education and training, for the 18 to 24 year-old population |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of population from 25 to 64 years old with at least secondary education |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Gender gap in employment rate (male-female, percentage points) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Time spent on unpaid domestic and care work |

|

Social inclusiveness |

UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework |

|

Seats held by women in municipal governments |

|

Urban governance |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Wastewater safely treated |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Percentage of households with access to in-house water distribution |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

Log frames EC project |

|

Safely managed drinking water services |

|

Urban governance |

UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework |

|

CO2 emissions from buildings |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD metropolitan database |

|

Energy consumption per capita |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Percentage of total electricity production that comes from renewable sources |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Net firm creation rate (%) (firm birth rate minus firm death rate) |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Annual growth rate of real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Unemployment rate (%) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Productivity (GVA per worker) in manufacture (ISIC rev4) (in constant 2010 USD PPP) |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Performance of public transport network, ratio between accessibility and proximity to people |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Research and development personnel as a share of total employment |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Growth in disposable income per capita |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Gini index of disposable income (after taxes and transfers) (from 0 to 1) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Median disposable income per equivalised household (in USD PPP, constant prices of 2010) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of population with access to at least 1 recreational opportunity (theatres, museums, cinemas, stadiums or cultural attractions) within 15 minutes of cycling |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Area size of informal settlements as a percentage of city area |

|

Social inclusiveness |

ETC Mapping |

|

Performance of public transport network, ratio between accessibility and proximity to people |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Emissions from the transport sector |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD metropolitan database |

|

Use of public transport (percentage of total motorised trips) |

|

Urban governance |

UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework |

|

Percentage of pedestrian streets and walkways |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

ETC Mapping |

|

Exposure to PM2.5 in µg/m³, population-weighted (micrograms per cubic metre) |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of household expenses dedicated to housing costs |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Municipal waste rate (kilos per capita) |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Recycling rate (percentage of municipal waste) |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Number of motor road vehicles per 100 people |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

People affected by disasters |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Average proportion of the built-up area of the area of influence corresponding to open spaces for public use and green spaces |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

Log frames EC project |

|

Bathing water quality of coasts (proportion of coasts with bathing water quality) |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

ETC Mapping |

|

Achieve no net loss of wetlands, streams and shoreline buffers |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

ETC Mapping |

|

Protected coastal area as a percentage of total coastal area |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Land abandonment (land that was previously used for crop or pasture/livestock grazing production but no longer has farming functions, i.e. a total cessation of agricultural activities, and has not been converted into forest or artificial areas) |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Terrestrial protected areas as a percentage of total area |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Tree cover as a percentage of total area |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Satisfaction with the administrative services of the city |

|

Urban governance |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Homicides per 100 000 persons |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Number of projects on urban governance developed and initiated with cross-sectoral actors and number of cross-city projects initiated |

|

Urban Governance |

Log frames EC project |

|

Percentage of people with access to public WiFi |

|

Urban governance |

ETC Mapping |

|

Remittances as a proportion of GDP |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Share of Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) co-patent applications that are done with foreign regions (in percentage of co-patent applications) |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of households with broadband Internet access |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Foreign direct investments |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

ETC Mapping |

|

Share of public expenditures allocated for local development co-operation |

|

Urban governance |

ETC Mapping |

|

Number of sectoral public policies formulated with the participation of civil society |

|

Urban governance |

Log frames EC project |

Table 3.3. Simplified list of indicators of the systemic monitoring and evaluation framework for city-to-city partnerships to localise the SDGs

|

Indicator |

SDG |

Category of the EC programme |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Percentage of population with a disposable income below 60% of the national median disposable income |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of population with access to public service provision systems that meet human basic needs including drinking water, sanitation, hygiene, energy, mobility, waste collection, healthcare, education and information technologies |

|

Urban governance |

UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework |

|

Productivity (GVA per worker) in agriculture, forestry and fishing (ISIC rev4) (in constant 2010 USD PPP) |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Prevalence of malnutrition |

|

Social inclusiveness |

UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework |

|

Mortality rates for the 0 to 4 year-old population (deaths per 10 000 people) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Life expectancy |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of early leavers from education and training, for the 18 to 24 year-old population |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of population from 25 to 64 years old with at least secondary education |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Gender gap in employment rate (male-female, percentage points) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Seats held by women in municipal governments |

|

Urban governance |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Percentage of households with access to in-house water distribution |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

Log frames EC project |

|

Safely managed drinking water services |

|

Urban governance |

UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework |

|

Energy consumption per capita |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Percentage of total electricity production that comes from renewable sources |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Annual growth rate of real GDP per capita |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Unemployment rate (%) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Productivity (GVA per worker) in manufacture (ISIC rev4) (in constant 2010 USD PPP) |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Research and development personnel as a share of total employment |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Gini index of disposable income (after taxes and transfers) (from 0 to 1) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Median disposable income per equivalised household (in USD PPP, constant prices of 2010) |

|

Social inclusiveness |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Percentage of population with access to at least 1 recreational opportunity (theatres, museums, cinemas, stadiums or cultural attractions) within 15 minutes of cycling |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Area size of informal settlements as a percentage of city area |

|

Social inclusiveness |

ETC Mapping |

|

Use of public transport (percentage of total motorised trips) |

|

Urban governance |

UN-Habitat Global Urban Monitoring Framework |

|

Exposure to PM2.5 in µg/m³, population-weighted (micrograms per cubic metre) |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Municipal waste rate (kilos per capita) |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Number of motor road vehicles per 100 people |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

People affected by disasters |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Average proportion of the built-up area of the area of influence corresponding to open spaces for public use and green spaces |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

Log frames EC project |

|

Achieve no net loss of wetlands, streams and shoreline buffers |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

ETC Mapping |

|

Terrestrial protected areas as a percentage of total area |

|

Resilience and greening in cities |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Homicides per 100 000 persons |

|

Urban governance |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Number of projects on urban governance developed and initiated with cross-sectoral actors and number of cross-city projects initiated |

|

Urban governance |

Log frames EC project |

|

Percentage of households with broadband Internet access |

|

Prosperity and innovation |

OECD localised indicator framework |

|

Remittances as a proportion of GDP |

|

Social inclusiveness |

JRC VLR Handbook |

|

Share of sectoral public policies formulated with the participation of civil society |

|

Urban governance |

Log frames EC project |

Methodology and process

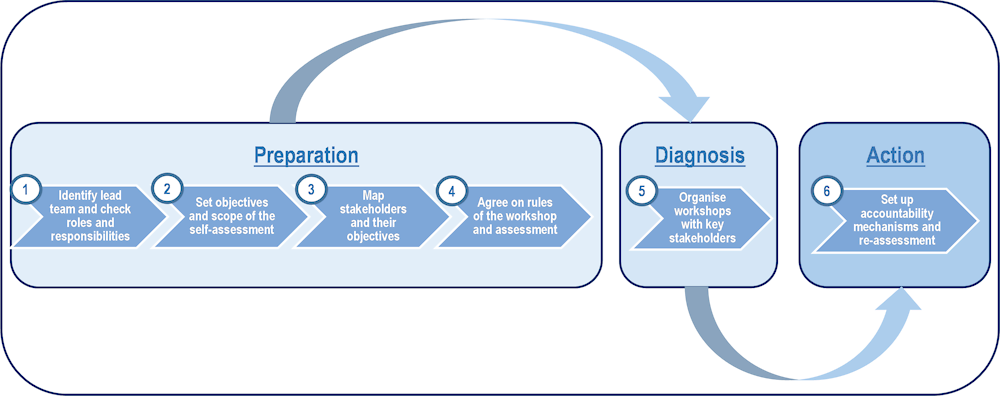

The following section explains the methodology to conduct the self-assessment (Figure 3.2), in particular the three different assessment stages: i) the preparation stage; ii) the diagnosis stage; and iii) the action stage as well as its link to the indicator framework.

Figure 3.2. Methodology for the self-assessment

Source: Author’s elaboration inspired from OECD (2018[1]), OECD Water Governance Indicator Framework, https://www.oecd.org/regional/OECD-Water-Governance-Indicator-Framework.pdf.

Preparation

Identification of team lead and roles and responsibilities

A successful self-assessment process requires an effective lead institution and co-ordination team. In the case of city-to-city partnerships, this could be the municipal department in charge of the collaboration between the two cities or a dedicated office or agency involved in the partnership. The lead institution should have the convening power to gather stakeholders. It should also possess the human and financial resources to carry out the assessment and organise multi-stakeholder workshops to conduct the self-assessment. In addition, the lead institution should have the knowledge and capacity to carry out the assessment and be motivated and able to promote and implement the proposals for change that are derived from the assessment. It would be desirable for the lead institution to have experience in monitoring and evaluating city-to-city partnerships as well as in the use of methodologies to collect inputs from different stakeholders transparently and openly. The lead institution should ideally also have knowledge of data collection and indicators to be able to facilitate discussions about the proposed indicator framework during the workshops to make sure stakeholders can contribute to the measurement component.

Setting assessment objectives and stakeholder mapping

The self-assessment aims to measure the sustainability of city-to-city partnerships. To do so, it assesses different components, for example, multi-level governance structures and co‑ordination for greater effectiveness of city-to-city partnerships, the mainstreaming of data and indicators into the planning and strategies to incorporate digitalisation best practices in city-to-city partnerships. Furthermore, the self-assessment represents a tool for dialogue across stakeholders involved in a city-to-city partnership. As such, it should promote collective thinking among stakeholders, foster peer-to-peer learning across stakeholders involved in the city-to-city partnership, improve transparency and reduce information asymmetries, and enhance the accountability of the lead institution.

For a successful self-assessment of city-to-city partnerships, it is important to have an agreement on its objectives among the stakeholders involved in the process. In particular, stakeholders should be able to see how their contribution can lead to an improvement of the current institutional setting and policies implemented in the framework of the city-to-city partnerships. It is therefore crucial that the lead institution and stakeholders discuss and agree on the objectives and scope of the assessment. To ensure a high level of representation of stakeholders in the assessment, the lead institution should take the initiative to conduct a mapping of stakeholders involved. These should include representatives from the public administration involved in the city-to-city partnership, ideally from different levels of government, civil society organisations, academia, youth and the private sector, donor agencies and financial institutions. Based on the mapping, the lead institution should engage the identified stakeholders in the assessment and take their input into account to define priorities for follow-up actions.

Agreeing on the rules of the workshop and assessment

A multi-stakeholder workshop to conduct the self-assessment can bring value and requires clear rules. Once the objectives have been defined and the stakeholder mapping has been conducted, participants need to find an agreement on the rules of the workshop and the assessment. As a first step, they need to be familiarised with the G20 Principles on city-to-city partnerships to localise the SDGs and understand the concepts and their aspirations. The duration of the workshop should allow the lead institution and stakeholders sufficient time to share information and opinions, and gather data and ways forward on how to better comply with the G20 Principles in the ongoing city-to-city partnership. Necessary information and material, in particular on the G20 Principles, should be shared before the workshop. The moderator of the workshop should aim for balanced participation across stakeholders to ensure a diversity of opinions. Together with the lead institution, the moderator should also present the assessment criteria used in the exercise. Stakeholders should be given the option to provide open feedback and discuss and dispute the gathered opinions and scores.

Diagnosis

Organisation of the workshop

The workshop shall provide a platform where stakeholders can share, compare and confront their views on the city-to-city partnerships they are involved in. To allow for an in-depth assessment of the implementation of the ten G20 Principles, the number of meetings shall be determined according to the needs of the assessment (e.g. five principles per workshop or one workshop to cover all ten principles). Further meetings may be needed depending on the opportunities for stakeholders to provide input in between the workshops and to build consensus on the assessment and actions needed. An important component of the organisation of the workshop is the actual assessment. In addition to the familiarisation with the G20 Principles, stakeholders should be informed about the underlying scoreboard that measures the fulfilment of the different principles.

Open communication and transparent discussions are key success factors for the assessment. During the workshop, the moderator and lead institutions should clarify any misinterpretations and try to understand the reasons behind diverging opinions. This refers to both the level of implementation of the G20 Principles and possible priorities of actions for the future. Doing so could help the lead institution and participating stakeholders, to analyse the variety of perceptions, which can be due to different levels of knowledge, experience and interest. The workshop should provide the opportunity for stakeholders to share ideas and suggestions on how identified gaps and challenges could be addressed. These suggestions should feed into an action plan and an implementation timeline to facilitate the improvement of policy outcomes over the short, medium and long terms.

Action

Setting up accountability mechanisms and reassessment

For the successful implementation of the G20 Principles, self-assessment workshops should not remain a one-off event. Instead, the lead institution should keep the dialogue going among stakeholders and consult them in the development and implementation of follow-up actions after the assessment. Ideally and to the extent possible, the lead institution should aim to generate future opportunities for stakeholders to continue to engage and track progress on the objectives defined in the workshops. An accountability mechanism to facilitate this process and verify that stakeholders’ inputs were considered and addressed could be set up. In addition, the self‑assessment could be repeated over time to identify expected changes resulting from targeted actions, e.g. through elaborating an action plan. Every reassessment should take all three steps of the methodology into account. That means for example potentially redefining the lead institution, key stakeholders, objectives and roles of the workshop if necessary. Such reassessment could be conducted on a regular basis and feature in governance and policy changes. The application of the five-level scoreboard could furthermore allow for the comparability of results over time.

Reference

[1] OECD (2018), OECD Water Governance Indicator Framework, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regional/OECD-Water-Governance-Indicator-Framework.pdf.

Note

← 1. Including the Principles on Quality Infrastructure Investment, the G20 Guidelines on Quality Infrastructure for Regional Connectivity and the G20 High Level Principles on Sustainable Habitat through Regional Planning.