Consumption taxes1 account for approximately one third of total tax revenue collected in OECD countries. They have two common forms: taxes on general consumption (mainly value added taxes and retail sales taxes) and taxes on specific goods and services (mainly excise duties).

Consumption Tax Trends 2022

1. Consumption tax revenue: Main figures and trends

1.1. Introduction

1.1.1. Classification of consumption taxes

In the OECD classification, “taxes” are confined to compulsory, unrequited payments to general government. According to the OECD nomenclature, taxes are divided into five broad categories: taxes on income, profits and capital gains (1000); social security contributions (2000); taxes on payroll and workforce (3000); taxes on property (4000); and taxes on goods and services (5000) whose detailed composition is provided in the OECD Revenue Statistics Interpretative Guide (OECD, 2021[1])

Consumption taxes (Category 5100 “Taxes on production, sale, transfer, leasing and delivery of goods and rendering of services”) fall mainly into two sub-categories:

General taxes on goods and services (5110), which includes value added taxes (5111), Sales taxes (5112) and Turnover and other general taxes on goods and services (5113).

Taxes on specific goods and services (5120), consisting primarily of Excises (5121), Customs and import duties (5123) and Taxes on specific services (5126 which includes for example the taxes on insurance premiums and financial services).

Consumption taxes such as VAT, sales taxes and excise duties are often categorised as indirect taxes. They are generally levied on transactions, products or events (OECD Glossary of Tax Terms (OECD, 2022[2])) and collected from businesses in the production and distribution chain, before being passed on to final consumers as part of the purchase price of a good or service. They are not directly imposed on income or wealth but rather on the expenditure that income and wealth finance.

1.1.2. Structure of this chapter

This chapter first presents internationally comparable data on consumption tax revenues of OECD countries in 1965-2020 (Section 1.2), focusing in particular on the two main consumption tax categories in OECD countries, i.e. value added taxes (Section 1.2.3) and excise duties (Section 1.2.4). This is complemented with a brief overview of the evolution of VAT and excise revenues during the Covid-19 pandemic, outlining the analysis of preliminary data for 2021 presented in the Special Feature of the 2022 edition of Revenue Statistics on The Impact of COVID-19 on OECD Tax Revenues (Section 1.2.6). This chapter finally presents an overview of the main design features of value added taxes (Section 1.3), retail sales taxes (Section 1.4) and excise duties (Section 1.5).

1.2. Evolution of consumption tax revenues

1.2.1. Consumption taxes account for 30% of total tax revenue in OECD countries, on average

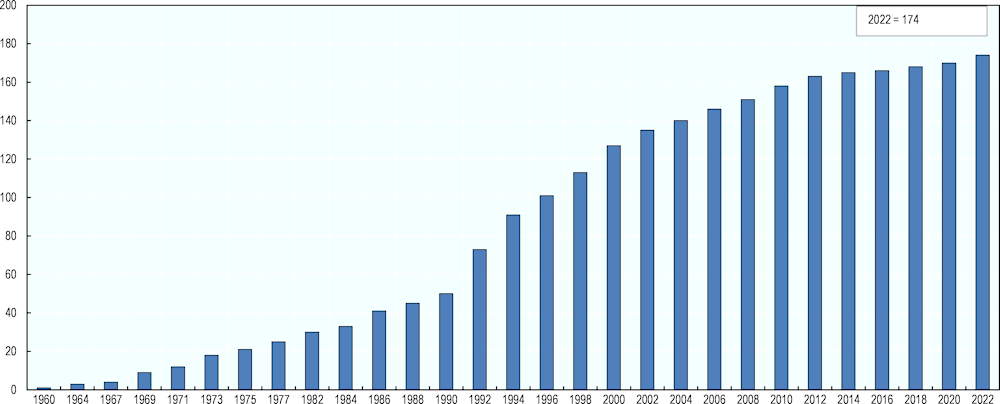

In 2020, consumption taxes accounted for 30% of the total tax revenue in OECD countries on average, representing 9.9%% of these countries’ GDP (see Annex Table 1.A.1). Approximately two thirds of revenue from consumption taxes is attributable to taxes on general consumption (mainly VAT and sales taxes) and one-third to taxes on specific goods and services (mainly excise duties - see Annex Table 1.A.2 and Annex Table 1.A.3).

Figure 1.1. Average tax revenue as a percentage of aggregate taxation, by category of tax, 2020

Note: Percentage of total taxation 2020

Source: OECD Adapted from Revenue Statistics 2022, OECD publishing Paris (OECD, 2022[3]).

Between 2018 and 2020, the average consumption tax-to-GDP ratio in OECD countries decreased by 0.3 percentage point, from 10.2% to 9.9%. 28 out of 38 OECD countries reported a decrease in their consumption tax-to-GDP ratios during this period, while 9 countries recorded an increase (Australia, Japan, Lithuania, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Slovak Republic and Türkiye) and 1 country (the United States) saw no change. Slovenia, Ireland and Iceland reported the largest decrease (of 1.4, 1.2 and 1.0 percentage points respectively) whereas Japan, Mexico and Norway recorded the largest increase (all three increased by 0.7 percentage points).

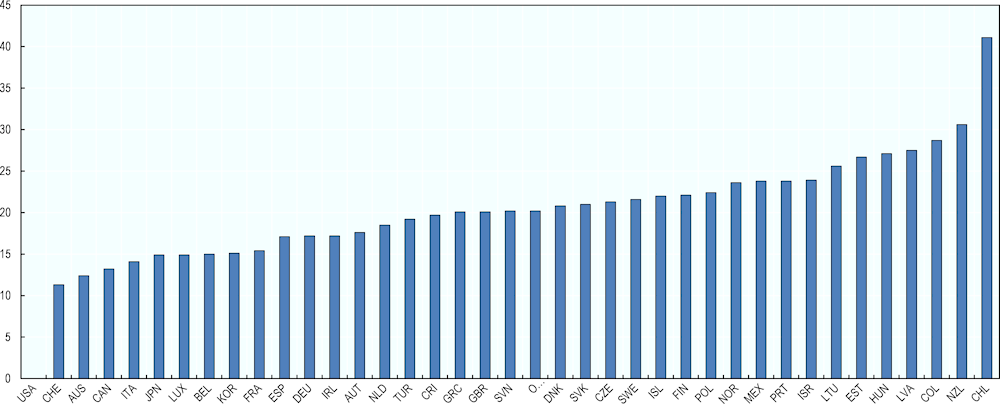

The overall share of consumption taxes in total tax revenue decreased to 30.0% in 2020 from 30.8% in 2018 and from 32.1% in 2010 on average. This decline is mainly attributable to the further decreasing importance of taxes on specific goods and services as a share of total taxation in OECD countries, on average (as discussed in 1.2.2. and 1.2.4 below). The share of consumption taxes in total tax revenue decreased in 26 countries between 2018 and 2020, while it increased in 11 countries (Australia, Chile, France, Hungary, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and Türkiye) and no change was recorded in one country (Finland). Consumption taxes produce more than 40% of total taxes in 5 OECD countries (Chile, Colombia, Hungary, Latvia, Türkiye) and more than 50% of total tax revenue in one country (Chile). By contrast, they account for less than 20% of total taxes in 3 OECD countries (Japan, Switzerland and the United States).

1.2.2. General consumption taxes generate twice as much tax revenue as specific consumption taxes

Taxes on general consumption include VAT, sales taxes and other general taxes on goods and services. Revenues from these taxes have remained stable between 2018 and 2020, both as a share of GDP and as a share of total taxation. They decreased slightly as a share of GDP (- 0.1 p.p.) from 7.0% in 2018 to 6.9% on average in 2020, representing 20.9% of total tax revenues in OECD countries on average in 2020, slightly down from 21.1% in 2018.

Their importance varies considerably across OECD countries both as a share of GDP and as a share of total taxation (see Annex Table 1.A.2). In Australia, Ireland, Switzerland and the United States, taxes on general consumption represent less than 4% of GDP while they represent more than 9% of GDP in Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden. Taxes on general consumption produce more than 20% of total taxes in 21 of the 38 OECD countries. They represent more than 29% of total taxation in Chile, Colombia, Hungary, Latvia and New Zealand. By contrast, they account for less than 15% of total tax revenues in Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and the United States.

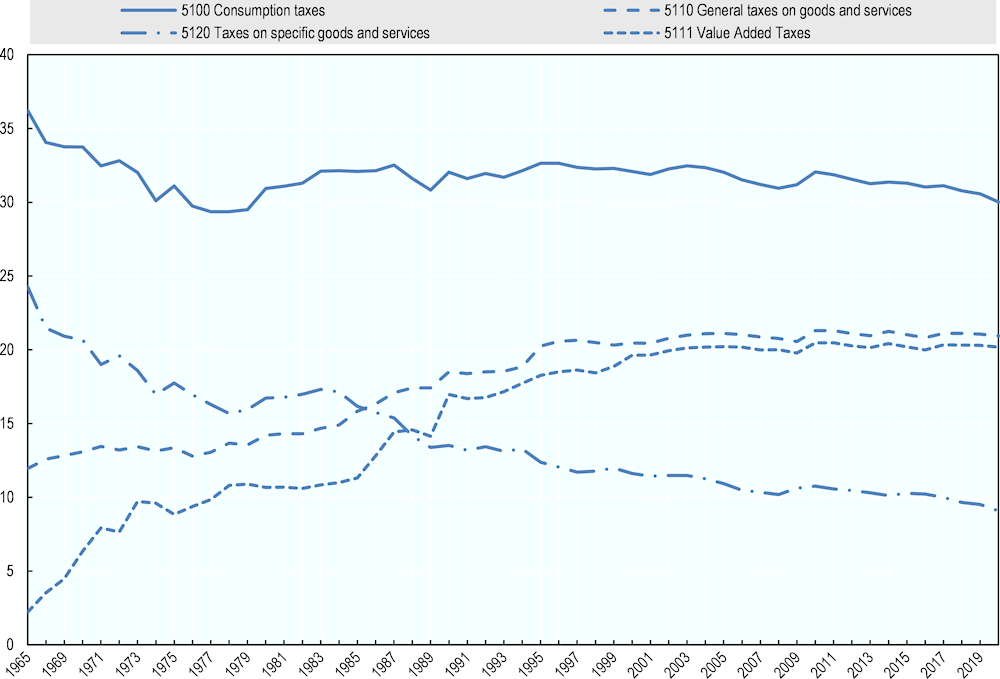

Over the longer term, OECD countries have relied increasingly on taxes on general consumption. Since 1975, the share of these taxes as a percentage of GDP in OECD countries increased considerably from 4.1% to 6.9% in 2020. They produced only 13.4% of total tax revenues in OECD countries in 1975 compared to 20.9% in 2020.

1.2.3. VAT remains the largest source of consumption tax revenues, by far

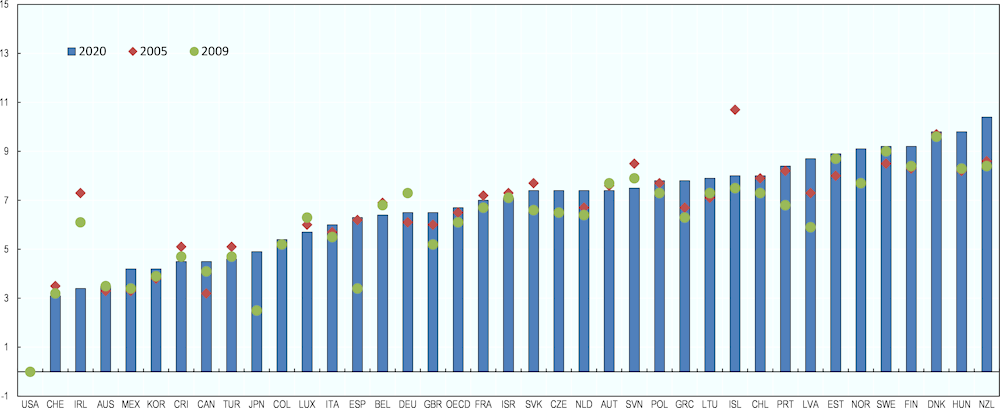

VAT revenues have remained stable in OECD countries between 2018 and 2020 on average, at 6.7% as a share of GDP in 2020 (the same level as in 2018 and 2019) and at 20.2% as a share of total taxation, slightly down from 20.3% in 2018 and 2019 (see Annex Table 1.A.4). 21 OECD countries recorded a drop in VAT revenues as a share of GDP between 2018 and 2020, while 13 reported an increase (Australia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Hungary, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway and Slovak Republic) and 4 saw no change (Canada, Finland, Sweden and Switzerland). Decreases of 0.5 percentage points (p.p.) or more were recorded in Germany (-0.5 p.p.), Chile and Iceland (-0.6 p.p.), in Greece and Slovenia (-0.7 p.p.), and in Ireland (-0.9 p.p.). The largest increases were seen in Netherlands (+0.6 p.p.), Norway (+0.7 p.p.) and in Japan and New Zealand (+0.9 p.p.).

Revenues from VAT decreased in 21 countries as a share of total taxes between 2018 and 2020, while an increase of VAT as a share of total taxation was seen in 13 OECD countries (Australia, Chile, Costa Rica, Finland, Hungary, Japan, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Slovak Republic, Sweden) and no change was recorded in 3 countries (France, Israel, Lithuania). Decreases of 1.0 percentage point (p.p.) or more were observed in in Germany (-1.0 p.p.), the United Kingdom (-1.1 p.p.), Greece (-1.2 p.p.), Portugal (-1.3 p.p.), Iceland (-1.6 p.p.), Slovenia and Spain (-1.9 p.p.) and Ireland (-2.2 p.p.). The largest increases were seen in New Zealand (+1.0 p.p.), Hungary (+1.2 p.p.), Costa Rica (+1.9 p.p.), Japan (+2.1 p.p.) and Norway (+2.4 p.p.).

Value added taxes have been implemented in 37 of the 38 OECD countries, the United States being the only OECD country that does not impose a VAT. In 1975, thirteen of the current OECD member countries had a VAT (see Annex Table 2.A.1 in Chapter 2). Colombia, Greece, Iceland, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain and Türkiye introduced a VAT in the 1980s while Switzerland followed shortly after. Central European economies introduced value added taxes in the late 1980s and early 1990s, often based on the European Union (EU) model in anticipation of their future EU membership. Costa Rica implemented VAT in 2019 and Australia implemented a VAT (“Goods and Services Tax – GST) in 2000.

Over the longer term, revenues from VAT as a percentage of GDP slightly increased from 6.5% in 2005 to 6.7% in 2020 on average and remained stable as a share of total taxation at 20.2% over the same period. An increase of VAT revenues as a share of GDP was observed in 24 OECD countries between 2005 and 2020, while a decrease was recorded in 13 countries and Annex Table 1.A.4. The largest increases were observed during that period in Japan (+2.4 p.p.), New Zealand (+1.8 p.p.), Hungary (+1.6 p.p.), Norway and Latvia (+1.4 p.p.) and Canada (+1.3 p.p.) whereas the largest decreases were seen in Ireland (-3.9 p.p.), Iceland (-2.7p.p.) and Slovenia (-1.0 p.p.). VAT revenues decreased as a percentage of GDP on average in OECD countries as a consequence of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) between 2007 and 2009, as illustrated by the decline of the average VAT-to-GDP ratio from 6.5% in 2005 to 6.1% in 2009. VAT revenues as a share of GDP broadly returned to their pre-crisis level in 2012 on average in OECD countries and have remained relatively stable since then.

Figure 1.2. Value added taxes (5111) as a percentage of GDP 2005-2020

The share of VAT in total tax revenues in OECD countries shows a considerable spread in 2020, ranging from 15% or less in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg and Switzerland to more than 25% in Chile, Colombia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and New Zealand. VAT (GST) produces 30.6% in New Zealand and 41.1% in Chile (see Figure 1.3 and Annex Table 1.A.4). VAT produces 15% or more of total tax revenues in 31 of the 38 OECD countries and it accounts for more than 20% of total taxes in 21 of these countries.

Many factors influence VAT revenue and its importance in countries’ tax mix. Tax policy decisions regarding the balance between the various sources of government revenue obviously play a key role but the efficiency of the tax system to collect VAT revenue effectively is also crucial. The most powerful of the drivers of (changes in) VAT revenues is countries’ capacity to collect the tax on its natural base, i.e. final consumption, as influenced by the application of reduced rates and exemptions and the capacity to combat fraud, evasion and tax planning. The capacity of collecting the VAT on inbound digital supplies also plays a growing role. These efficiency factors, the impact of which is estimated in countries’ VAT Revenue Ratio (see Chapter 2), often play a greater role in countries’ VAT revenues than the level of the standard VAT rate (Michael Keen, 2013[4]).

Figure 1.3. Value added taxes (5111) as percentage of total taxation 2020

1.2.4. Taxes on specific goods and services now account for less than 10% of total taxes

Annex Table 1.A.3 shows that revenues from taxes on specific goods and services have decreased steadily as a percentage of GDP between 1975 (4.6%) and 2020 (3.0%). The evolution of the share of taxes on specific goods and services in total taxation has followed the same pattern – it has almost halved from 17.7% in 1975 to 9.1% on average in 2020. The share of taxes on specific goods and services in total tax revenues has fallen in all OECD countries since 1975. They now account for less than 13% of total taxes in all OECD countries, except in Mexico and Türkiye where taxes on specific goods and services represent 13,0% and 22.4% of total taxation respectively.

Excise duties currently form the bulk of taxes on specific goods and services, representing 2.3% of GDP on average in 2020, down from 2.4% in 2018. They produced 6.9% of total tax revenues in 2020 on average, down from 7.3% in 2018. Between 2018 and 2020, 31 OECD countries recorded a drop in revenues from excise duties as a share of GDP, with only 3 countries reporting an increase (Canada, Mexico and Türkiye) and 4 countries recording no change (Latvia, Norway, Sweden and the United States). Rather than as a significant revenue raiser, excise duties taxes are increasingly used to influence customer behaviour. This is discussed in further detail in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4.

1.2.5. The composition of consumption taxes has fundamentally changed over time

The substantially increased importance of VAT in OECD countries over time has served to counteract the diminishing share of taxes on specific goods and services, such as excise and custom duties, in consumption tax revenues. The share of general consumption taxes (5110), especially VAT (5111), in total tax revenue in OECD countries almost doubled between 1965 and 2020 from 11.9% to 20.9% on average (see Figure 1.4 and Annex Table 1.A.6). By contrast, the share of specific taxes on consumption (5120; mostly on tobacco, alcoholic drinks and fuels, as well as some environment-related taxes) more than halved during that period from 24.3% to 9.1% of total revenues in OECD countries on average. The overall share of taxes on consumption (5100) in total taxation fell from 36.2 % to 30.0% between 1965 and 2020, while it increased as a percentage of GDP during that period from 8.7% in 1965 to 9.9% in 2020 on average.

Figure 1.4. Share of consumption taxes as percentage of total taxation 1965-2020

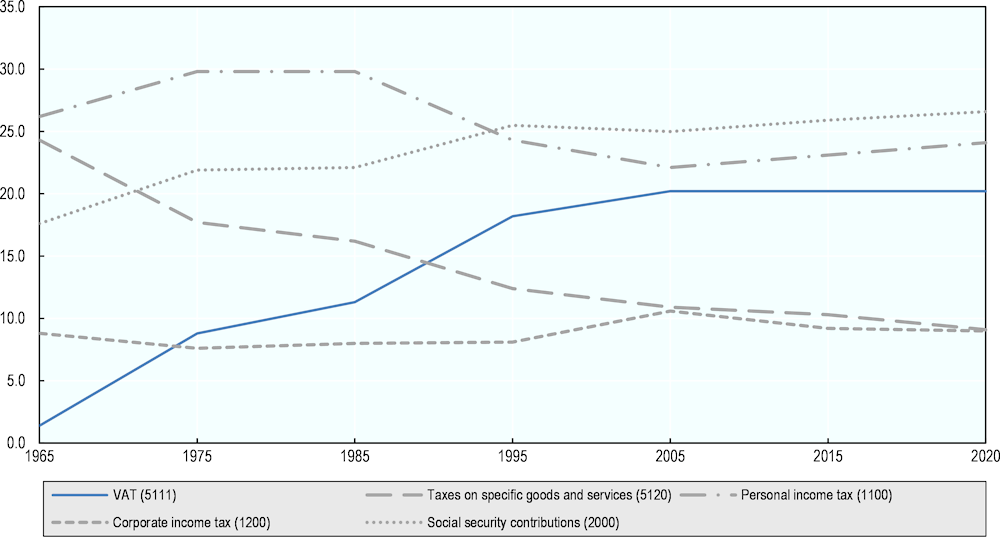

Figure 1.5 below and Annex Table 1.A.6 show the evolution of the tax structure (as a share of major taxes in total tax revenue) in OECD countries between 1965 and 2020. Personal income tax and social security contributions account for more than 50% of total tax revenue in OECD countries in 2020, respectively producing approximately 24.1% and 26.6% of total taxes on average. With a share of approximately 20%, VAT is the third largest source of tax revenue for OECD countries on average. Corporate income taxes represent approximately 10% of total tax revenue in 2020.

Figure 1.5. Evolution of the tax mix as a percentage of total tax revenue 1965-2020

1.2.6. The impact of COVID-19 on VAT and excises

The 2022 edition of Revenue Statistics presents a Special Feature on The Impact of COVID-19 on OECD Tax Revenues (OECD, 2022[3]). It notably uses preliminary data for 2021 to analyse changes in tax revenues across OECD countries during the second year of the pandemic. Readers are referred to this Special Feature for a detailed analysis of tax revenue performance in OECD countries in 2021, including changes of the main tax types both in nominal terms and as a share of GDP. This section hereafter briefly recalls the main VAT measures included in governments’ fiscal and tax policy responses to the COVID-19 outbreak and outlines the main trends in revenues from VAT and from excise duties during the second year of the pandemic in particular.

Tax policy has been a critical tool in governments’ response to COVID-19 across the OECD. Over the course of the pandemic, the objectives of tax policy evolved in line with the evolution of the pandemic itself and governments’ broader policy goals. In general, tax policy in 2020 was characterised by measures to protect workers and businesses from the disruptions caused by the pandemic, while there has been greater focus on policies to promote investment and accelerate the post-pandemic recovery in 2021. Some tax policy measures have evolved over the course of the pandemic to become more targeted, while others were eliminated altogether. While a majority of the measures were temporary, most of these temporary measures were extended beyond their initial duration. Other measures became permanent.

VAT policy and administration measures were an important component of governments’ early fiscal and tax policy responses to the COVID-19 outbreak. These measures were mainly aimed at supporting business cash flow, in particular through VAT payment deferrals and the acceleration of excess input VAT refunds, and at reducing compliance burdens notably by extending filing and reporting deadlines. Most OECD countries have also taken VAT measures to facilitate emergency medical responses and to support the healthcare sector. These included in particular the introduction of zero (or reduced) VAT rates for supplies and imports of medical equipment and sanitary products (gloves, masks, hand sanitiser…) and for healthcare services where these were not yet VAT exempt or subject to reduced rates under normal rules (OECD, 2020[5]).

Some countries also introduced temporary VAT rate reductions to stimulate consumption and/or to support specific economic sectors that had been hardest hit by the pandemic (e.g. tourism, hospitality) (see Section 2.2.3). A few OECD countries introduced more general temporary rate reductions. Germany reduced its standard VAT rate from 19% to 16% and its reduced VAT rate from 7% to 5% from 1 July to end 2020. Ireland reduced its standard VAT rate from 23% to 21% from 1 September 2020 until 28 February 2021. Norway decreased its 12% reduced VAT rate to 6% from 1 April until the end of 2020. Most temporary changes to VAT rates that were introduced in 2020 to address the pandemic were withdrawn in 2021, except those related to medical supplies used to respond to the pandemic.

As highlighted above (Section 1.2.3), VAT revenues remained stable in OECD countries in 2020 at 6.7% as a share of GDP on average and accounting for 20.2% of total taxes compared to 20.3% in 2018 and 2019. Nominal VAT revenue decreased in 2020 compared to 2019 in 19 OECD countries while it increased slightly in 12 countries and remained almost stable in 6 others. Overall VAT revenues declined in OECD countries by 2.4% in nominal terms in 2020.

The preliminary figures for 2021 analysed in the Special Feature in Revenue Statistics 2022 show that VAT revenues increased by 17.3% in nominal terms between 2020 and 2021. These revenues rose in all OECD countries, with the increase exceeding 20% in nine. As a share of GDP, VAT revenue grew in 30 countries in 2021, remained unchanged in three and declined in three. The increase in VAT revenues exceeded 0.5 percentage points (p.p.) as a share of GDP in 13 countries with the largest increase observed in Chile (+1.5 p.p.). The largest decline occurred in Norway where VAT revenues as a share of GDP declined by 1.0 p.p. although they increased by 8.5% in nominal terms (OECD, 2022[3]).

Excise revenue showed a relatively weak growth in nominal terms of 5.5% in 2021 (versus a 5.4% decline in 2020). Excise revenues rose in nominal terms in 29 countries and declined in eight. The increase exceeded 10% in six countries while the decline exceeded this threshold in two countries (OECD, 2022[3]).

1.3. Main features of VAT design

1.3.1. VAT is the main consumption tax for countries around the world

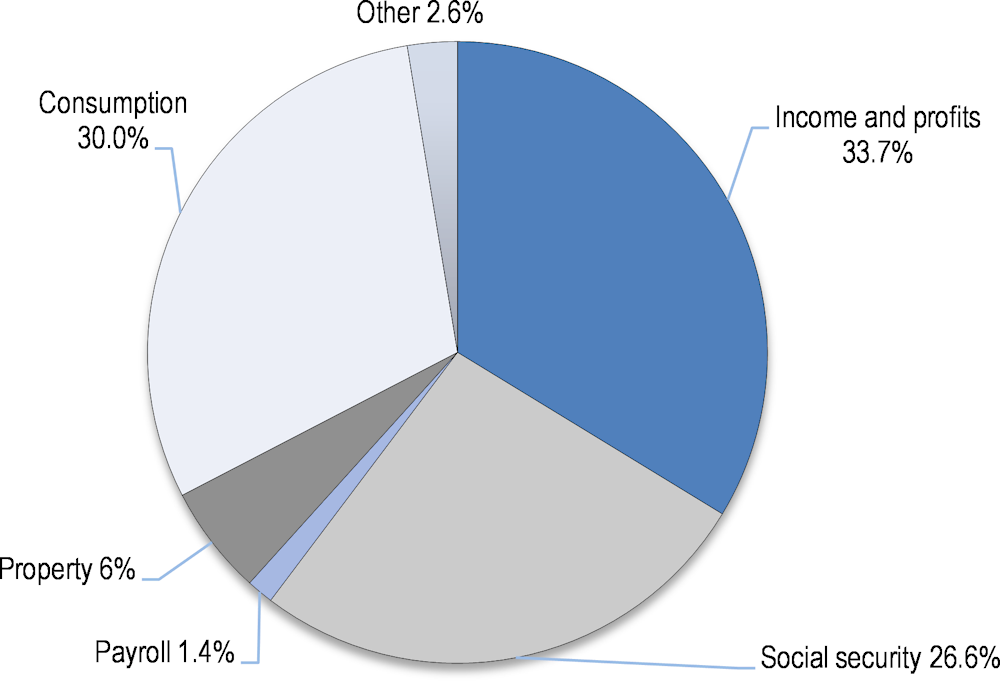

Since the mid-1980s, VAT (also called Goods and Services Tax – GST) has become the main consumption tax in terms of both revenue and geographical coverage. VAT is designed to be a tax on final consumption that is broadly neutral towards the production process and international trade. It is widely seen as a relatively growth-friendly tax. Many developing countries have introduced a VAT during the last two decades to replace lost revenues from trade taxes following trade liberalisation. Over 170 countries operate a VAT today (see Annex A), including 37 of the 38 OECD member countries, the only exception being the United States although most states within the US employ some form of retail sales tax. This is more than twice as many as 25 years ago. VAT raises approximately a fifth of total tax revenues in the OECD and worldwide.

Although there is a wide diversity in the way VAT systems are implemented, this tax can be defined by its purpose and its specific tax collection mechanism. The OECD International VAT/GST Guidelines (OECD, 2017[6]) provide an overview of the core features of VAT, which are briefly summarised below.

VAT is a tax on final consumption

The overarching purpose of a VAT is to impose a broad-based tax on final consumption, which is understood to mean final consumption by households. In principle, only private individuals, as distinguished from businesses, engage in the consumption at which a VAT is targeted. “Businesses buy and use capital goods, office supplies and the like - but they do not consume them in this sense” (Hellerstein, 2010[7]) In practice, however, many VAT systems impose VAT burden not only on consumption by private individuals, but also on various entities that are involved in non-business activities.

From a legal and practical standpoint, VAT is essentially a transaction tax, where all supplies are subject to taxation along the supply chain in a staged collection process, up to the final consumer.

It can be argued, however, that the economic burden of the VAT may effectively lie in a variable proportion on business and consumers. Indeed, the effective incidence of VAT, like that of any other tax, is determined not only by its formal nature but also by market circumstances, including the elasticity of demand and the nature of competition between suppliers (Ebrill, Keen and Perry, 2001[8]).

VAT is collected under a staged collection process

The staged collection process means that VAT is in principle collected on sales to businesses (B2B) as well as on sales to private consumers (B2C). However, since its purpose is to impose a tax on final consumption by households, the burden of the VAT should in principle not rest on businesses, except where explicitly provided for in legislation (e.g. where purchases are made for the private consumption of the business owners or their employees). This is achieved by giving businesses the right to deduct the VAT they incur on their inputs from the VAT they collect on their outputs and to remit only the balance to the tax authorities. Each business in the supply chain takes part in the process of controlling and collecting the tax, remitting the proportion of tax corresponding to its margin, i.e. on the difference between the VAT imposed on its taxed inputs and the VAT imposed on its taxed outputs. In this respect, the VAT differs from a retail sales tax (“RST”), which taxes consumption through a single-stage levy imposed in theory only at the point of final sale.

This requires a mechanism for relieving businesses of the burden of the VAT they pay when they acquire goods, services or intangibles. There are two main approaches for operating the staged collection process:

Under the invoice credit method (which is a “transaction based method”), each trader charges VAT at the rate specified for each supply and passes to the purchaser an invoice showing the amount of tax charged. The purchaser is in turn able to credit that input tax against the output tax it charges on its sales, remitting the balance to the tax authorities and receiving refunds when there are excess credits. This method is based on invoices that could, in principle, be crosschecked to pick up any overstatement of credit entitlement. By linking the tax credit on the purchaser’s inputs to the tax paid by the purchaser, the invoice credit method is designed to discourage fraud.

Under the subtraction method (which is an “entity based method”), the tax is levied directly on an accounts-based measure of value added, which is determined for each business by subtracting the VAT calculated on allowable purchases from the VAT calculated on taxable supplies.

Almost all jurisdictions that operate a VAT use the invoice-credit method. In the OECD, only Japan uses "credit subtraction VAT", where the VAT on taxable sales (output tax) is calculated by multiplying the total taxable sales by the VAT rate while the amount of deductible input VAT is calculated by extracting the VAT from the total VAT inclusive amount of purchases as recorded in the business's purchase records. This includes the purchases from exempt suppliers such as unregistered small businesses so that there is no incentive to purchase from taxable businesses, but excludes exempt supplies such as financial services. The VAT-liability is calculated on an annual basis, except for certain businesses that can elect for quarterly accounting periods (e.g. exporters that are eligible for VAT refunds). There is no requirement to issue VAT invoices; businesses are required to document their VAT liability and this documentation can include invoices.

The core principle of VAT neutrality

The staged collection process, whereby tax is in principle collected from businesses only on the value added at each stage of production and distribution, gives to the VAT its essential character in domestic trade as an economically neutral tax. The full right to deduct input tax through the supply chain, except by the final consumer, ensures the neutrality of the tax, whatever the nature of the product, the structure of the distribution chain, and the means used for its delivery (e.g. retail stores, physical delivery, Internet downloads). As a result of the staged payment system, VAT “flows through the businesses” to tax supplies made to final consumers (Chapter 2 of the OECD’s International VAT/GST Guidelines (OECD, 2017[9]) presents the key principles of VAT-neutrality and a set of internationally agreed standards to support neutrality of VAT in international trade).

Where the deductible input VAT for any period exceeds the output VAT collected, there is an excess of VAT credit, which should in principle be refunded. This is generally the case in particular for exporters, since their output is in principle free of VAT (i.e. exempt with right to deduct the related input tax) under the destination principle, and for businesses whose purchases are larger than their sales in the same period (such as new or developing businesses or seasonal businesses). These are especially important groups in terms of wider economic development, so it is important that VAT systems provide for an effective treatment of excess credits to avoid the risk that VAT introduces significant and costly distortions for these groups of business. At the same time, however, the payment of refunds evidently can create significant opportunities for fraud and corruption. It is important therefore that an effective refund system is administered properly, supported by a well-designed and operated risk-based compliance strategy and by a comprehensive audit strategy (Liam Ebrill, 2001[10]).

When the right to deduct input VAT covers all business inputs, the final burden of the tax does not lie on businesses but on consumers. This is not always the case in practice, as the right to deduct input tax may be restricted in a number of ways. Some are deliberate and some result from imperfect administration (see Chapter 2).

The application of the destination principle in VAT achieves neutrality in international trade. Under the destination principle, exports are not subject to tax with refund of input taxes (that is, “free of VAT” or “zero-rated”) and imports are taxed on the same basis and at the same rates as domestic supplies. Accordingly, the total tax paid in relation to a supply is determined by the rules applicable in the jurisdiction of its consumption and all revenue accrues to the jurisdiction where the supply to the final consumer occurs.

Sales tax systems, although they work differently in practice, also set out to tax consumption of goods, and to some extent services, within the jurisdiction of consumption. Exported goods are usually relieved from sales tax to provide a degree of neutrality for cross-border trade. However, in most sales tax systems, businesses do incur some irrecoverable sales tax on their inputs and, if they subsequently export goods, there will be an element of sales tax embedded in the price.

1.3.2. VAT has now been implemented in 174 countries worldwide

The spread of VAT has been among the most important developments in taxation over the last half century. Limited to less than 10 countries in the late 1960s, it is today an important source of revenue in 174 countries worldwide (see Figure 1.1 and Annex 1.A).

The domestic and international neutrality properties of the VAT have encouraged its global spread. Many developing countries have introduced a VAT during the last decades to replace lost revenues from trade taxes following trade liberalisation. In the European Union, VAT is directly associated with the development of its internal market. The adoption of a common VAT framework in the European Union was intended to remove the trade distortions associated with cascading indirect taxes that it replaced and to facilitate the creation of a common market in which member states cannot use taxes on production and consumption to protect their domestic market or to gain a competitive advantage compared to other member states. A VAT is operated in 37 of the 38 OECD countries, the only exception being the United States.

Figure 1.6. Countries with VAT 1960 - 2022

1.4. Retail sales taxes and their application in the United States

Although VAT is today the most widespread general consumption tax in the world (and within the OECD where 37 out of 38 member countries have implemented it), there is another form of general consumption tax: the retail sales tax (RST). RST is a tax on general consumption charged only once on products at the last point of sale to the end user. In principle, only consumers are charged the tax; resellers are exempt if they are not final end users of the products. To implement this principle, business purchasers are normally required to provide the seller with a "resale certificate," which states that they are purchasing an item to resell it, or with equivalent evidence that the business will fulfil whatever tax obligations it may have (e.g. a so-called “direct pay” permit, which is analogous to the “reverse charge” concept). The tax is charged on each item sold to purchasers who do not provide such a certificate or equivalent evidence. The retail sales tax covers not only retailers, but all businesses dealing with purchasers who do not provide a resale or other evidence signifying that no tax is due (e.g. a public body or a charity, unless specific exemption applies).

The basis for taxation is the sales price. Like the VAT and unlike multi-stage cumulative taxes, this system allows the tax burden to be calculated precisely and it does not in principle discriminate between different forms of production or distribution channels. In practice, however, at least in the United States, the failure of the retail sales tax to reach many services and the limitation of the resale exemption to products that are resold in the same form that they are purchased, or are physically incorporated into products that are resold, leads to substantial taxation of business inputs.

In theory, the outcomes of VAT and retail sales tax should be identical: they both ultimately aim to tax final consumption of a wide range of products where such consumption takes place. They also both tax the consumption expenditure i.e. the transaction between the seller and the buyer rather than the actual consumption. In practice, however, the end result may be somewhat different given the fundamental difference in the way the tax is collected. Unlike VAT where the tax is collected at each stage of the value chain under a staged payment system (see Section 1.5 above), sales taxes are collected only at the very last stage i.e. on the sale by the retailer to the final consumer. The latter method has significant disadvantages: the higher the rate the more pressure is placed on the weakest link in the chain i.e. on the retailer and in particular on numerous small retailers. All the revenue is at risk if the retailer fails to remit the tax to the authorities and the audit and invoice trail is poorer than under a VAT, especially for services. In addition, revenue is not secured at the time of importation and this can be crucial for many developing countries. As a result, a single point resale sales tax is efficient at relatively low rates, but is increasingly difficult to administer as rates rise (Smith and Tait, 1990[11]).

The United States is the only OECD country that employs a retail sales tax as the principal consumption tax. However, the retail sales tax in the United States is not a national tax. Rather, it is a subnational tax imposed at the state and local government levels. Currently, 45 of the 50 States as well as thousands of local tax jurisdictions impose broad-based retail sales taxes. In general, the local taxes are identical in coverage to the state-level tax, are administered at the state level and amount in substance simply to an increase in the state rate, with the additional revenues distributed to the localities. Retail sales taxes are complemented in every state by functionally identical “use” taxes imposed on goods purchased from out-of-state vendors, because the state has no power to tax out-of-state “sales” and therefore imposes a complementary tax on the in-state “use” (Jerome R. Hellerstein, 2022[12]).

Combined state and local sales tax rates vary widely in the United States, from 1.76% (Alaska), 4.44% (Hawaii) and 5.22% (Wyoming) to 9.55% (Louisiana and Tennessee),9.47% (Arkansas) and 9.29% (Washington). Five states do not have a state-wide sales tax (Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon and, of these, only Alaska generally allows localities to charge local sales taxes and Montana permits special taxes in local resort areas (Janelle Fritts, 2022[13]). These rates are (much) lower than the applicable VAT rates in OECD countries. This is due to two main factors: the compliance risks associated with the sales tax collection method (see above) and the competition between jurisdictions (see below).

Retail sales and use taxes in force in the United States are subject to significant competitive pressure, especially in the context of interstate and international trade. Prior to the US Supreme Court’s decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc. (June 2018), Supreme Court rulings interpreting constitutional restraints on state taxation prohibited states from requiring vendors to collect tax with respect to cross-border sales when they were not physically present in the purchaser’s state. States were therefore unable effectively to collect use taxes with respect to cross-border sales from remote sellers, a problem that became increasingly significant with the advent of the Internet and online sales. In Wayfair, the Court overruled the physical-presence requirement for enforcing tax collection obligations on remote vendors as “unsound and incorrect,” and it sustained a South Dakota statute imposing such obligations on remote vendors whose annual sales into the state exceeded USD 100 000 or who annual engaged in 200 or more separate transactions in the state. In place of the physical-presence nexus rule for requiring remote vendors to collect tax on sales to in-state customers, the Court adopted a nexus rule that looks to whether the vendor “avails itself of the substantial privilege of carrying on business” in the state based on its “economic and virtual contacts” with the state.

Although the general standards the Court articulated in Wayfair provide little concrete guidance to state tax administrators and state tax advisors as to the nature and level of “economic and virtual” contacts that will satisfy constitutional nexus norms for remote sellers, the Court did identify several features of the South Dakota statute that, in its view, were designed to prevent undue burdens upon interstate commerce and thus implicitly provided guidance to the states in designing their tax enforcement regimes. First, the nexus statute provided a safe harbour for those who transact only limited business in the state. Second, the statute did not apply retroactively. Third, South Dakota was one of more than 20 states that have adopted the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement (SSUTA - available at www.streamlinedsalestax.org), which “standardizes taxes to reduce administrative and compliance costs.” As the Court elaborated: “It requires a single, state level tax administration, uniform definitions of products and services, simplified tax rate structures, and other uniform rules. It also provides sellers access to sales tax administration software paid for by the State. Sellers who choose to use such software are immune from audit liability.” Indeed, as of June 2022, every one of the 45 states with sales taxes has adopted legislation or administrative guidance imposing tax collection obligations on remote vendors, as well as on digital platforms, based on thresholds analogous to those sustained by the Court in Wayfair, and more than half of these states are members of SSUTA, a number that is likely to increase in the future. It is also worth noting that the US Congress possesses the ultimate power (regardless of pre-existing judicially created nexus rules) to prescribe the terms under which remote vendors must collect tax on cross-border sales and could approve proposed legislation authorising states to require such collection if they have adopted SSUTA or similar measures to ease compliance burdens for vendors.

1.5. Excise as an instrument to influence consumer behaviour

In the OECD nomenclature, taxes on specific goods and services (5120) include a range of taxes such as excises, customs and import duties, taxes on exports and taxes on specific services. Consumption Tax Trends 2022 focuses on excises only.

A number of general characteristics differentiate excise duties from value added taxes:

They are levied on a limited range of products.

They are not normally due until the goods enter free circulation, which may be at a late stage in the supply chain.

Excise charges are generally assessed by reference to the weight, volume, strength or quantity of the product, combined in some cases, with ad valorem taxes.

Consequently, and unlike VAT, the excise system is characterised by a small number of taxpayers at the manufacturing or wholesale stage (although, in some cases they can also be levied at the resale stage).

Whilst VAT was first introduced about 60 years ago, excise duties have existed since the dawn of civilisation. They are levied on a specific range of products and are assessed by reference to various characteristics such as weight, volume, strength or quantity of the product, combined in some cases with ad valorem taxes. Although they generally apply to alcoholic beverages, tobacco products and fuels in all OECD countries and beyond, their tax base, calculation method and rates vary widely between countries, reflecting local cultures and historical practice. Excise duties are increasingly being used to influence consumer behaviour to achieve health and, increasingly, environmental objectives.

As with VAT, excise taxes aim to be neutral internationally. As the tax is normally collected when the goods are released into free circulation, neutrality is often ensured by exempting the targeted goods from excise duties under controlled regimes (such as bonded warehouses) and certification of final export (again under controlled conditions) by customs authorities. Similarly, imported excise goods are levied at importation although frequently the goods enter into controlled tax-free regimes until released into free circulation.

Excise taxes may cover a very wide range of products like salt, sugar, matches, fruit juice or chocolates. However, the range of products subject to excise has declined with the expansion of taxes on general consumption. On the other hand, excise taxes on alcohol, tobacco and hydrocarbon oils are increasingly used by governments to influence consumers’ behaviour and continue to raise significant revenues for governments (see Chapter 3 and Chapter 4).

There has indeed been a discernible trend in recent decades to ascribe to these taxes characteristics other than simply revenue raising. A number of excise duties have been adjusted with a view to discouraging certain behaviours considered harmful, especially for health and environmental reasons. This is particularly the case for excise duties on tobacco and alcohol whose rates have increased over time with the aim of reducing consumption of these products. The structure of certain excise duties, for example on road fuels and vehicles, has also gradually changed to encourage more responsible behaviour towards the collective welfare, especially the environment (see Chapter 3).

References

[8] Ebrill, L., M. Keen and V. Perry (2001), The Modern VAT, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C., https://doi.org/10.5089/9781589060265.071.

[7] Hellerstein, W. (2010), Interjurisdictional Issues in the Design of a VAT, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228153719.

[13] Janelle Fritts (2022), State and Local Sales Tax Rates, Midyear 2022, Tax Foundation.

[10] Liam Ebrill, M. (2001), The Modern VAT, IMF, Washington.

[4] Michael Keen (2013), “The Anatomy of the VAT”, IMF Working Paper WP13/111.

[2] OECD (2022), OECD Glossary of tax terms, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/ctp/glossaryoftaxterms.htm.

[3] OECD (2022), Revenue Statistics 2022: The Impact of COVID-19 on OECD Tax Revenues, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8a691b03-en.

[1] OECD (2021), OECD Revenue Statistics Interpretative Guide, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/oecd-classification-taxes-interpretative-guide.pdf.

[5] OECD (2020), Consumption Tax Trends 2020: VAT/GST and Excise Rates, Trends and Policy Issues, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/152def2d-en.

[9] OECD (2017), International VAT/GST Guidelines, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264271401-en.

[6] OECD (2017), International VAT/GST Guidelines, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264271401-en.

[11] Smith, S. and A. Tait (1990), “Value Added Tax: International Practice and Problems.”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 100/399, p. 269, https://doi.org/10.2307/2233622.

[12] Thomson Reuters (ed.) (2022), State Taxation.

Annex 1.A. Consumption taxes revenue

Annex Table 1.A.1. Consumption taxes (5100) as a percentage of GDP and total taxation

|

|

Tax revenue as % of GDP |

Tax revenue as % of total taxation |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1975 |

2005 |

2009 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

1975 |

2005 |

2009 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Australia |

6.5 |

7.5 |

6.7 |

6.4 |

6.6 |

6.3 |

6.2 |

6.5 |

25.8 |

25.3 |

26.5 |

25.5 |

23.7 |

21.9 |

22.5 |

22.9 |

|

Austria |

12.3 |

11.1 |

10.9 |

10.9 |

10.9 |

10.7 |

10.7 |

10.4 |

33.9 |

27.1 |

26.6 |

26.5 |

25.3 |

25.4 |

25.1 |

24.6 |

|

Belgium |

10.1 |

10.5 |

10.3 |

10.5 |

10.2 |

10.4 |

10.2 |

9.8 |

26.0 |

24.2 |

24.1 |

24.6 |

23.2 |

23.7 |

24.0 |

23.0 |

|

Canada |

8.1 |

7.7 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

7.1 |

7.3 |

7.2 |

6.9 |

26.0 |

23.7 |

21.5 |

22.5 |

21.5 |

21.7 |

21.7 |

20.2 |

|

Chile |

.. |

10.2 |

9.1 |

9.5 |

10.4 |

10.5 |

10.3 |

9.8 |

.. |

48.7 |

52.2 |

48.2 |

50.8 |

49.5 |

49.2 |

50.5 |

|

Colombia |

.. |

8.1 |

8.0 |

8.1 |

8.0 |

8.1 |

8.3 |

7.6 |

.. |

44.4 |

42.3 |

44.7 |

40.4 |

42.0 |

42.1 |

40.5 |

|

Costa Rica |

.. |

9.2 |

8.3 |

8.1 |

7.9 |

7.2 |

7.3 |

6.9 |

|

42.4 |

37.5 |

36.5 |

34.5 |

31.3 |

31.1 |

30.4 |

|

Czech Republic |

.. |

10.1 |

10.2 |

10.2 |

10.7 |

10.8 |

10.6 |

10.3 |

.. |

29.5 |

31.6 |

31.8 |

32.3 |

30.8 |

30.4 |

29.7 |

|

Denmark |

12.1 |

15.3 |

14.1 |

13.9 |

13.4 |

13.5 |

13.1 |

13.4 |

32.7 |

31.8 |

31.4 |

31.1 |

29.1 |

30.5 |

27.9 |

28.4 |

|

Estonia |

.. |

12.1 |

13.9 |

13.1 |

13.7 |

13.3 |

13.4 |

12.5 |

.. |

40.7 |

39.8 |

39.6 |

41.2 |

40.3 |

40.1 |

37.6 |

|

Finland |

11.4 |

13.0 |

12.6 |

12.6 |

13.6 |

13.7 |

13.6 |

13.5 |

31.6 |

30.8 |

30.8 |

31.0 |

31.3 |

32.4 |

32.2 |

32.4 |

|

France |

11.3 |

10.7 |

10.2 |

10.8 |

11.4 |

11.9 |

11.9 |

11.8 |

32.4 |

25.0 |

24.5 |

25.5 |

25.1 |

25.8 |

26.5 |

26.0 |

|

Germany |

8.7 |

9.7 |

10.6 |

10.2 |

9.9 |

9.7 |

9.7 |

9.1 |

25.4 |

28.1 |

28.9 |

28.7 |

26.7 |

25.3 |

25.1 |

24.1 |

|

Greece |

7.9 |

10.1 |

9.8 |

11.4 |

12.2 |

13.7 |

13.6 |

12.8 |

42.2 |

31.7 |

31.8 |

35.2 |

33.3 |

34.3 |

34.4 |

32.9 |

|

Hungary |

.. |

14.3 |

15.0 |

15.5 |

16.6 |

16.1 |

15.8 |

15.8 |

.. |

39.2 |

38.8 |

42.2 |

42.9 |

43.8 |

43.5 |

43.9 |

|

Iceland |

18.3 |

15.7 |

10.6 |

10.9 |

11.0 |

11.6 |

10.7 |

10.6 |

62.2 |

40.0 |

34.0 |

33.8 |

31.3 |

31.8 |

30.7 |

29.5 |

|

Ireland |

12.4 |

10.8 |

9.2 |

9.2 |

6.9 |

6.3 |

6.2 |

5.1 |

44.4 |

35.8 |

32.7 |

33.0 |

29.6 |

28.3 |

28.6 |

25.9 |

|

Israel |

.. |

10.7 |

10.5 |

11.0 |

10.9 |

10.3 |

10.0 |

9.8 |

.. |

32.7 |

35.9 |

36.4 |

35.0 |

33.4 |

33.2 |

33.0 |

|

Italy |

6.9 |

9.4 |

9.4 |

10.0 |

10.5 |

10.4 |

10.4 |

9.9 |

28.3 |

24.1 |

22.5 |

23.9 |

24.5 |

25.0 |

24.7 |

23.3 |

|

Japan |

3.0 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

5.9 |

5.7 |

5.8 |

6.4 |

15.1 |

17.2 |

16.9 |

16.7 |

19.5 |

18.1 |

18.3 |

19.4 |

|

Korea |

8.9 |

7.2 |

7.0 |

7.3 |

6.2 |

6.6 |

6.6 |

6.3 |

60.0 |

33.3 |

30.7 |

32.6 |

26.2 |

24.7 |

24.3 |

22.9 |

|

Latvia |

.. |

11.3 |

10.4 |

11.2 |

12.4 |

13.3 |

13.0 |

13.2 |

.. |

40.6 |

36.9 |

39.3 |

41.7 |

42.8 |

41.9 |

41.6 |

|

Lithuania |

.. |

10.9 |

11.2 |

11.4 |

11.4 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

11.4 |

.. |

37.2 |

37.0 |

40.4 |

39.5 |

37.4 |

37.5 |

37.0 |

|

Luxembourg |

6.7 |

10.7 |

10.0 |

9.7 |

8.2 |

8.9 |

9.0 |

8.5 |

20.6 |

28.5 |

27.5 |

27.2 |

23.6 |

22.7 |

22.7 |

22.4 |

|

Mexico |

.. |

4.2 |

4.5 |

4.7 |

6.0 |

5.8 |

6.1 |

6.5 |

.. |

37.1 |

36.0 |

36.7 |

37.9 |

35.9 |

37.2 |

36.8 |

|

Netherlands |

8.5 |

10.2 |

9.8 |

10.1 |

10.0 |

10.5 |

10.9 |

11.0 |

22.5 |

29.3 |

28.0 |

28.2 |

27.1 |

27.1 |

27.7 |

27.5 |

|

New Zealand |

6.8 |

10.8 |

10.3 |

11.2 |

11.4 |

11.4 |

11.3 |

12.0 |

22.8 |

30.0 |

34.1 |

37.1 |

36.3 |

35.3 |

36.1 |

35.6 |

|

Norway |

14.2 |

11.1 |

10.9 |

11.0 |

11.0 |

11.1 |

11.2 |

11.8 |

36.6 |

26.1 |

26.5 |

26.3 |

28.6 |

28.1 |

27.9 |

30.5 |

|

Poland |

.. |

12.2 |

11.4 |

12.2 |

11.4 |

12.6 |

12.3 |

12.1 |

.. |

37.1 |

36.5 |

38.8 |

35.3 |

36.0 |

35.0 |

34.1 |

|

Portugal |

7.6 |

13.3 |

11.2 |

11.9 |

12.9 |

13.2 |

13.1 |

12.6 |

40.1 |

42.9 |

37.6 |

39.3 |

37.4 |

38.0 |

38.0 |

35.7 |

|

Slovak Republic |

.. |

11.6 |

9.8 |

9.6 |

10.7 |

11.1 |

11.2 |

11.3 |

.. |

37.1 |

33.8 |

34.3 |

32.9 |

32.4 |

32.4 |

32.0 |

|

Slovenia |

.. |

12.7 |

12.8 |

13.3 |

13.7 |

13.0 |

12.6 |

11.6 |

.. |

32.5 |

34.6 |

35.2 |

36.8 |

34.9 |

34.0 |

31.1 |

|

Spain |

4.3 |

9.3 |

6.1 |

7.9 |

9.6 |

9.5 |

9.3 |

9.0 |

24.0 |

26.3 |

20.6 |

25.3 |

28.2 |

27.3 |

26.7 |

24.5 |

|

Sweden |

8.7 |

11.9 |

12.3 |

12.3 |

11.6 |

11.9 |

11.7 |

11.6 |

22.7 |

25.1 |

28.1 |

28.7 |

27.3 |

27.3 |

27.3 |

27.5 |

|

Switzerland |

4.5 |

5.3 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

5.0 |

4.8 |

4.7 |

4.7 |

20.6 |

20.4 |

19.5 |

19.9 |

18.7 |

17.8 |

17.2 |

17.2 |

|

Türkiye |

4.7 |

11.0 |

10.2 |

11.3 |

10.6 |

9.4 |

8.7 |

9.9 |

40.9 |

47.4 |

43.6 |

45.8 |

42.7 |

39.0 |

37.5 |

41.5 |

|

United Kingdom |

8.1 |

9.5 |

8.8 |

9.6 |

10.3 |

10.2 |

10.2 |

9.6 |

23.7 |

29.4 |

28.3 |

30.2 |

32.7 |

31.5 |

31.6 |

29.8 |

|

United States |

4.2 |

3.8 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

17.1 |

14.7 |

15.5 |

15.5 |

14.6 |

15.6 |

15.3 |

15.0 |

|

OECD average |

8.7 |

10.2 |

9.6 |

9.9 |

10.1 |

10.2 |

10.0 |

9.9 |

31.1 |

32.0 |

31.2 |

32.1 |

31.3 |

30.8 |

30.6 |

30.0 |

Notes: For the purposes of this publication, “consumption Taxes” are considered as these under Item 5100 of the OECD classification of taxes.

The OECD average is the unweighted average.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]).

Annex Table 1.A.2. General taxes on goods and services (5110) as a percentage of GDP and total taxation

|

|

Tax revenue as % of GDP |

Tax revenue as % of total taxation |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

1975 |

2005 |

2009 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

1975 |

2005 |

2009 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Australia |

1.7 |

3.9 |

3.6 |

3.4 |

3.7 |

3.4 |

3.3 |

3.6 |

6.7 |

13.2 |

14.1 |

13.5 |

13.2 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

12.7 |

|

Austria |

7.2 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

7.6 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

7.4 |

19.8 |

18.6 |

18.8 |

18.7 |

17.7 |

18.0 |

18.0 |

17.6 |

|

Belgium |

6.3 |

7.0 |

6.9 |

7.0 |

6.7 |

6.8 |

6.7 |

6.4 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

16.1 |

16.4 |

15.1 |

15.5 |

15.8 |

15.1 |

|

Canada |

3.9 |

4.8 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.7 |

4.7 |

4.7 |

12.5 |

14.8 |

13.2 |

14.0 |

13.9 |

14.1 |

14.2 |

13.6 |

|

Chile |

.. |

7.9 |

7.3 |

7.6 |

8.4 |

8.6 |

8.3 |

8.0 |

.. |

37.8 |

42.1 |

38.5 |

40.8 |

40.2 |

39.9 |

41.1 |

|

Colombia |

.. |

5.9 |

6.0 |

6.1 |

6.1 |

6.5 |

6.7 |

6.3 |

.. |

32.3 |

32.0 |

33.9 |

30.4 |

33.8 |

34.1 |

33.5 |

|

Costa Rica |

.. |

5.1 |

4.7 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

|

23.3 |

21.3 |

21.0 |

19.8 |

18.1 |

18.8 |

20.0 |

|

Czech Republic |

.. |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.6 |

7.2 |

7.6 |

7.5 |

7.4 |

.. |

19.1 |

20.4 |

20.5 |

21.7 |

21.6 |

21.6 |

21.3 |

|

Denmark |

6.5 |

9.7 |

9.6 |

9.4 |

9.0 |

9.5 |

9.4 |

9.8 |

17.5 |

20.2 |

21.4 |

20.9 |

19.6 |

21.5 |

20.0 |

20.8 |

|

Estonia |

.. |

8.0 |

8.7 |

8.5 |

9.1 |

9.0 |

8.9 |

8.9 |

.. |

26.9 |

24.8 |

25.8 |

27.2 |

27.3 |

26.7 |

26.7 |

|

Finland |

5.7 |

8.3 |

8.4 |

8.3 |

9.0 |

9.2 |

9.2 |

9.2 |

15.6 |

19.9 |

20.5 |

20.4 |

20.6 |

21.6 |

21.7 |

22.1 |

|

France |

8.2 |

7.4 |

7.0 |

7.5 |

7.7 |

7.8 |

7.9 |

7.8 |

23.4 |

17.3 |

16.8 |

17.9 |

16.9 |

17.1 |

17.7 |

17.3 |

|

Germany |

5.0 |

6.1 |

7.3 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

6.5 |

14.6 |

17.8 |

19.8 |

19.8 |

18.8 |

18.2 |

18.2 |

17.2 |

|

Greece |

3.4 |

6.9 |

6.5 |

7.4 |

7.4 |

8.6 |

8.4 |

7.9 |

18.3 |

21.6 |

21.0 |

22.8 |

20.3 |

21.4 |

21.4 |

20.2 |

|

Hungary |

.. |

10.2 |

10.8 |

10.9 |

11.7 |

11.6 |

11.6 |

11.7 |

.. |

28.1 |

27.8 |

29.7 |

30.3 |

31.6 |

31.9 |

32.3 |

|

Iceland |

8.4 |

11.6 |

7.6 |

7.5 |

8.1 |

8.8 |

8.2 |

8.2 |

28.6 |

29.5 |

24.4 |

23.3 |

23.2 |

24.1 |

23.4 |

22.6 |

|

Ireland |

4.1 |

7.3 |

6.1 |

6.0 |

4.5 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

3.4 |

14.7 |

24.2 |

21.7 |

21.7 |

19.4 |

19.4 |

19.6 |

17.2 |

|

Israel |

.. |

9.0 |

8.6 |

9.0 |

9.1 |

8.7 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

.. |

27.5 |

29.4 |

29.6 |

29.4 |

28.2 |

28.0 |

28.3 |

|

Italy |

3.5 |

5.7 |

5.5 |

6.1 |

6.1 |

6.2 |

6.2 |

6.0 |

14.3 |

14.6 |

13.1 |

14.5 |

14.2 |

14.8 |

14.7 |

14.1 |

|

Japan |

0.0 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

4.1 |

4.0 |

4.2 |

4.9 |

0.0 |

9.5 |

9.6 |

9.6 |

13.7 |

12.8 |

13.2 |

14.9 |

|

Korea |

1.9 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

3.6 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

4.2 |

12.7 |

17.4 |

17.2 |

17.5 |

15.3 |

15.3 |

15.7 |

15.1 |

|

Latvia |

.. |

7.3 |

6.2 |

7.2 |

8.7 |

9.3 |

9.1 |

9.2 |

.. |

26.4 |

22.1 |

25.2 |

29.1 |

29.8 |

29.3 |

29.1 |

|

Lithuania |

.. |

7.5 |

7.3 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

7.9 |

7.9 |

.. |

25.8 |

24.3 |

27.5 |

26.9 |

25.8 |

26.2 |

25.8 |

|

Luxembourg |

3.9 |

6.0 |

6.3 |

6.2 |

5.4 |

5.8 |

5.8 |

5.7 |

12.1 |

16.0 |

17.2 |

17.3 |

15.6 |

14.7 |

14.7 |

14.9 |

|

Mexico |

.. |

3.3 |

3.4 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

3.8 |

4.2 |

.. |

29.3 |

26.9 |

29.4 |

23.9 |

24.3 |

23.4 |

23.8 |

|

Netherlands |

5.4 |

6.7 |

6.4 |

6.7 |

6.5 |

6.8 |

7.2 |

7.4 |

14.4 |

19.2 |

18.4 |

18.7 |

17.6 |

17.6 |

18.2 |

18.5 |

|

New Zealand |

2.7 |

8.6 |

8.4 |

9.3 |

9.5 |

9.5 |

9.5 |

10.4 |

9.0 |

23.8 |

27.6 |

30.7 |

30.2 |

29.6 |

30.4 |

30.6 |

|

Norway |

8.0 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

7.8 |

8.2 |

8.4 |

8.7 |

9.2 |

20.5 |

18.2 |

18.7 |

18.6 |

21.4 |

21.3 |

21.6 |

23.7 |

|

Poland |

.. |

7.7 |

7.3 |

7.6 |

7.0 |

8.1 |

7.9 |

8.0 |

.. |

23.2 |

23.1 |

24.2 |

21.6 |

23.1 |

22.6 |

22.4 |

|

Portugal |

2.1 |

8.2 |

6.8 |

7.5 |

8.6 |

8.7 |

8.8 |

8.4 |

11.2 |

26.5 |

22.9 |

24.8 |

24.9 |

25.1 |

25.4 |

23.8 |

|

Slovak Republic |

.. |

7.7 |

6.6 |

6.1 |

6.8 |

7.1 |

7.3 |

7.4 |

.. |

24.6 |

22.8 |

21.8 |

20.8 |

20.7 |

21.0 |

21.0 |

|

Slovenia |

.. |

8.5 |

7.9 |

8.1 |

8.3 |

8.2 |

8.0 |

7.5 |

.. |

21.6 |

21.3 |

21.3 |

22.2 |

22.1 |

21.6 |

20.2 |

|

Spain |

2.7 |

6.2 |

3.4 |

5.2 |

6.4 |

6.6 |

6.5 |

6.3 |

15.3 |

17.7 |

11.6 |

16.6 |

19.1 |

19.0 |

18.8 |

17.2 |

|

Sweden |

4.6 |

8.5 |

9.1 |

9.1 |

9.0 |

9.2 |

9.1 |

9.2 |

12.0 |

18.1 |

20.8 |

21.3 |

21.1 |

21.1 |

21.3 |

21.6 |

|

Switzerland |

1.9 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

3.2 |

8.7 |

13.6 |

12.6 |

12.9 |

12.6 |

11.9 |

11.5 |

11.5 |

|

Türkiye |

0.0 |

5.1 |

4.7 |

5.4 |

5.1 |

4.8 |

4.2 |

4.6 |

0.0 |

21.8 |

20.0 |

21.7 |

20.6 |

19.8 |

18.1 |

19.2 |

|

United Kingdom |

3.0 |

6.0 |

5.2 |

6.1 |

6.9 |

6.9 |

6.9 |

6.5 |

8.9 |

18.6 |

16.9 |

19.0 |

21.7 |

21.2 |

21.3 |

20.2 |

|

United States |

1.7 |

2.1 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

7.0 |

8.0 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

7.8 |

8.3 |

8.2 |

8.3 |

|

OECD average |

4.1 |

6.7 |

6.3 |

6.6 |

6.8 |

7.0 |

6.9 |

6.9 |

13.4 |

21.0 |

20.6 |

21.3 |

21.0 |

21.1 |

21.1 |

20.9 |

Note: The OECD average is the unweighted average.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]).

Annex Table 1.A.3. Taxes on specific goods and services (5120) as a percentage of GDP and total taxation

|

|

Tax revenue as % of GDP |

Tax revenue as % of total taxation |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

1975 |

2005 |

2009 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

1975 |

2005 |

2009 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Australia |

4.9 |

3.6 |

3.1 |

3.0 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

19.1 |

12.1 |

12.3 |

12.0 |

10.5 |

9.9 |

10.6 |

10.1 |

|

Austria |

5.1 |

3.5 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.1 |

3.0 |

2.9 |

14.0 |

8.4 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

7.6 |

7.4 |

7.1 |

7.0 |

|

Belgium |

3.8 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

9.8 |

8.1 |

8.0 |

8.2 |

8.1 |

8.2 |

8.2 |

7.9 |

|

Canada |

4.2 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.2 |

13.6 |

8.9 |

8.3 |

8.5 |

7.7 |

7.6 |

7.4 |

6.6 |

|

Chile |

.. |

2.3 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

.. |

10.9 |

10.1 |

9.8 |

10.0 |

9.3 |

9.3 |

9.4 |

|

Colombia |

.. |

2.2 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

.. |

12.1 |

10.3 |

10.9 |

10.0 |

8.2 |

8.0 |

7.0 |

|

Costa Rica |

.. |

4.2 |

3.6 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.0 |

2.9 |

2.3 |

|

19.2 |

16.1 |

15.5 |

14.7 |

13.1 |

12.4 |

10.3 |

|

Czech Republic |

.. |

3.5 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

.. |

10.3 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

10.6 |

9.2 |

8.8 |

8.4 |

|

Denmark |

5.6 |

5.5 |

4.5 |

4.6 |

4.4 |

4.0 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

15.2 |

11.6 |

10.0 |

10.2 |

9.6 |

9.0 |

7.9 |

7.6 |

|

Estonia |

.. |

4.1 |

5.2 |

4.6 |

4.6 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

3.6 |

.. |

13.8 |

15.0 |

13.8 |

13.9 |

13.0 |

13.4 |

10.9 |

|

Finland |

5.8 |

4.6 |

4.2 |

4.3 |

4.7 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

4.3 |

16.0 |

11.0 |

10.4 |

10.6 |

10.7 |

10.8 |

10.5 |

10.3 |

|

France |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.7 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

9.0 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

7.6 |

8.2 |

8.7 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

|

Germany |

3.7 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

2.6 |

10.8 |

10.2 |

9.0 |

8.8 |

7.9 |

7.1 |

6.9 |

6.9 |

|

Greece |

4.5 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

4.0 |

4.7 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

4.9 |

23.9 |

9.9 |

10.6 |

12.3 |

12.9 |

12.7 |

12.9 |

12.6 |

|

Hungary |

.. |

4.0 |

4.2 |

4.6 |

4.9 |

4.5 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

.. |

11.1 |

10.9 |

12.5 |

12.6 |

12.2 |

11.5 |

11.5 |

|

Iceland |

9.9 |

4.1 |

3.0 |

3.4 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

33.6 |

10.6 |

9.6 |

10.5 |

8.2 |

7.7 |

7.3 |

6.9 |

|

Ireland |

8.3 |

3.5 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

2.4 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

1.7 |

29.7 |

11.6 |

11.0 |

11.3 |

10.2 |

8.9 |

9.0 |

8.7 |

|

Israel |

.. |

1.7 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

.. |

5.3 |

6.5 |

6.7 |

5.6 |

5.2 |

5.2 |

4.7 |

|

Italy |

3.4 |

3.7 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

4.5 |

4.3 |

4.2 |

3.9 |

14.0 |

9.5 |

9.4 |

9.4 |

10.4 |

10.2 |

10.0 |

9.2 |

|

Japan |

3.0 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

15.1 |

7.7 |

7.3 |

7.2 |

5.8 |

5.3 |

5.1 |

4.5 |

|

Korea |

7.0 |

3.4 |

3.1 |

3.4 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

2.4 |

2.2 |

47.3 |

15.9 |

13.6 |

15.1 |

10.9 |

9.4 |

8.7 |

7.8 |

|

Latvia |

.. |

4.0 |

4.2 |

4.0 |

3.8 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

.. |

14.2 |

14.8 |

14.1 |

12.6 |

13.0 |

12.6 |

12.6 |

|

Lithuania |

.. |

3.3 |

3.8 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

.. |

11.4 |

12.7 |

12.8 |

12.6 |

11.6 |

11.3 |

11.2 |

|

Luxembourg |

2.7 |

4.7 |

3.7 |

3.5 |

2.8 |

3.1 |

3.2 |

2.9 |

8.4 |

12.5 |

10.3 |

9.8 |

7.9 |

8.0 |

8.0 |

7.5 |

|

Mexico |

.. |

0.9 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

.. |

7.8 |

9.1 |

7.3 |

14.0 |

11.6 |

13.9 |

13.0 |

|

Netherlands |

3.1 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

8.1 |

10.1 |

9.6 |

9.5 |

9.6 |

9.6 |

9.5 |

8.9 |

|

New Zealand |

4.1 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

13.8 |

6.2 |

6.4 |

6.4 |

6.1 |

5.7 |

5.8 |

5.0 |

|

Norway |

6.3 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

2.8 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

2.7 |

16.1 |

7.9 |

7.8 |

7.6 |

7.2 |

6.8 |

6.3 |

6.9 |

|

Poland |

.. |

4.6 |

4.2 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

4.3 |

4.2 |

.. |

13.9 |

13.3 |

14.6 |

13.7 |

12.9 |

12.4 |

11.8 |

|

Portugal |

5.5 |

5.1 |

4.4 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

4.3 |

4.2 |

28.9 |

16.4 |

14.7 |

14.5 |

12.5 |

12.9 |

12.6 |

11.9 |

|

Slovak Republic |

.. |

3.9 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

.. |

12.5 |

11.0 |

12.5 |

12.1 |

11.8 |

11.4 |

11.0 |

|

Slovenia |

.. |

4.2 |

4.9 |

5.3 |

5.4 |

4.8 |

4.6 |

4.1 |

.. |

10.8 |

13.3 |

13.9 |

14.5 |

12.9 |

12.4 |

10.9 |

|

Spain |

1.6 |

3.0 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

8.7 |

8.6 |

9.0 |

8.7 |

9.2 |

8.2 |

7.9 |

7.3 |

|

Sweden |

4.1 |

3.3 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

10.7 |

7.1 |

7.4 |

7.3 |

6.2 |

6.2 |

6.0 |

5.9 |

|

Switzerland |

2.6 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

11.9 |

6.7 |

6.8 |

6.9 |

6.1 |

5.9 |

5.7 |

5.7 |

|

Türkiye |

4.7 |

5.9 |

5.5 |

5.9 |

5.5 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

5.3 |

40.9 |

25.5 |

23.6 |

24.1 |

22.0 |

19.2 |

19.3 |

22.4 |

|

United Kingdom |

5.1 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

3.3 |

3.1 |

14.8 |

10.8 |

11.5 |

11.2 |

11.0 |

10.4 |

10.3 |

9.6 |

|

United States |

2.5 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

10.0 |

6.7 |

7.1 |

7.2 |

6.7 |

7.3 |

7.1 |

6.7 |

|

OECD average |

4.6 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

3.0 |

17.7 |

10.9 |

10.6 |

10.8 |

10.3 |

9.7 |

9.5 |

9.1 |

Note: The OECD average is the unweighted average.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]).

Annex Table 1.A.4. Value added taxes (5111) as a percentage of GDP and total taxation

|

|

Tax revenue as % of GDP |

Tax revenue as % of total taxation |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

1975 |

2005 |

2009 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

1975 |

2005 |

2009 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Australia |

0.0 |

3.9 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.6 |

3.3 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

0.0 |

12.9 |

13.8 |

13.1 |

12.8 |

11.7 |

11.7 |

12.4 |

|

Austria |

7.2 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

7.6 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

7.4 |

19.8 |

18.6 |

18.8 |

18.7 |

17.7 |

18.0 |

18.0 |

17.6 |

|

Belgium |

6.3 |

6.9 |

6.8 |

7.0 |

6.6 |

6.7 |

6.6 |

6.4 |

16.2 |

15.9 |

15.9 |

16.2 |

15.0 |

15.4 |

15.6 |

15.0 |

|

Canada |

0.0 |

3.2 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

0.0 |

9.9 |

12.7 |

13.7 |

13.3 |

13.6 |

13.5 |

13.2 |

|

Chile |

.. |

7.9 |

7.3 |

7.6 |

8.4 |

8.6 |

8.3 |

8.0 |

.. |

37.8 |

42.1 |

38.5 |

40.8 |

40.2 |

39.9 |

41.1 |

|

Colombia |

.. |

5.2 |

5.2 |

5.3 |

5.2 |

5.7 |

5.8 |

5.4 |

.. |

28.2 |

27.5 |

29.3 |

26.0 |

29.4 |

29.6 |

28.7 |

|

Costa Rica |

.. |

5.1 |

4.7 |

4.6 |

4.4 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

|

23.3 |

21.3 |

21.0 |

19.3 |

17.8 |

18.5 |

19.7 |

|

Czech Republic |

.. |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.6 |

7.2 |

7.6 |

7.5 |

7.4 |

.. |

19.1 |

20.4 |

20.5 |

21.7 |

21.6 |

21.6 |

21.3 |

|

Denmark |

6.5 |

9.7 |

9.6 |

9.4 |

9.0 |

9.5 |

9.4 |

9.8 |

17.5 |

20.2 |

21.4 |

20.9 |

19.6 |

21.5 |

20.0 |

20.8 |

|

Estonia |

.. |

8.0 |

8.7 |

8.5 |

9.1 |

9.0 |

8.9 |

8.9 |

.. |

26.9 |

24.8 |

25.7 |

27.2 |

27.3 |

26.7 |

26.7 |

|

Finland |

5.7 |

8.3 |

8.4 |

8.3 |

9.0 |

9.2 |

9.2 |

9.2 |

15.6 |

19.9 |

20.5 |

20.4 |

20.6 |

21.6 |

21.7 |

22.1 |

|

France |

8.1 |

7.2 |

6.7 |

6.8 |

6.9 |

7.1 |

7.1 |

7.0 |

23.1 |

16.7 |

16.2 |

16.1 |

15.2 |

15.4 |

15.9 |

15.4 |

|

Germany |

5.0 |

6.1 |

7.3 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

6.5 |

14.6 |

17.8 |

19.8 |

19.8 |

18.8 |

18.2 |

18.2 |

17.2 |

|

Greece |

0.0 |

6.7 |

6.3 |

7.1 |

7.3 |

8.5 |

8.4 |

7.8 |

0.0 |

21.1 |

20.4 |

22.0 |

20.0 |

21.3 |

21.3 |

20.1 |

|

Hungary |

.. |

8.2 |

8.3 |

8.5 |

9.5 |

9.5 |

9.5 |

9.8 |

.. |

22.6 |

21.3 |

23.0 |

24.5 |

25.9 |

26.2 |

27.1 |

|

Iceland |

0.0 |

10.7 |

7.5 |

7.4 |

7.9 |

8.6 |

8.0 |

8.0 |

0.0 |

27.3 |

23.9 |

22.8 |

22.6 |

23.6 |

22.9 |

22.0 |

|

Ireland |

4.1 |

7.3 |

6.1 |

6.0 |

4.5 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

3.4 |

14.7 |

24.2 |

21.7 |

21.7 |

19.4 |

19.4 |

19.6 |

17.2 |

|

Israel |

.. |

7.3 |

7.1 |

7.4 |

7.7 |

7.4 |

7.1 |

7.1 |

.. |

22.3 |

24.2 |

24.3 |

24.8 |

23.9 |

23.8 |

23.9 |

|

Italy |

3.3 |

5.7 |

5.5 |

6.1 |

6.1 |

6.2 |

6.2 |

6.0 |

13.7 |

14.6 |

13.1 |

14.5 |

14.2 |

14.8 |

14.7 |

14.1 |

|

Japan |

.. |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

4.1 |

4.0 |

4.2 |

4.9 |

.. |

9.5 |

9.6 |

9.6 |

13.7 |

12.8 |

13.2 |

14.9 |

|

Korea |

0.0 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

3.6 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

4.2 |

0.0 |

17.4 |

17.2 |

17.5 |

15.3 |

15.3 |

15.7 |

15.1 |

|

Latvia |

.. |

7.3 |

5.9 |

6.6 |

7.6 |

8.4 |

8.6 |

8.7 |

.. |

26.4 |

20.9 |

23.3 |

25.6 |

27.1 |

27.8 |

27.5 |

|

Lithuania |

.. |

7.1 |

7.3 |

7.8 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

7.9 |

7.9 |

.. |

24.3 |

24.1 |

27.5 |

26.7 |

25.6 |

26.0 |

25.6 |

|

Luxembourg |

3.9 |

6.0 |

6.3 |

6.2 |

5.4 |

5.8 |

5.8 |

5.7 |

12.1 |

16.0 |

17.2 |

17.3 |

15.6 |

14.7 |

14.7 |

14.9 |

|

Mexico |

.. |

3.3 |

3.4 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

3.8 |

4.2 |

.. |

29.3 |

26.9 |

29.4 |

23.9 |

24.3 |

23.4 |

23.8 |

|

Netherlands |

5.4 |

6.7 |

6.4 |

6.7 |

6.5 |

6.8 |

7.1 |

7.4 |

14.4 |

19.2 |

18.4 |

18.7 |

17.6 |

17.6 |

18.2 |

18.5 |

|

New Zealand |

0.0 |

8.6 |

8.4 |

9.3 |

9.5 |