This chapter lays out the legal framework of the European Union (EU) for regulating state aid. It explains the rationale for the prohibition of state subsidies for programmes that have the potential to distort free trade in the single European market. It defines the terms used in the regulatory instruments and identifies what lawyers look for in analysing a particular activity to check its compliance with the law. It also describes the penalties that can be applied if an activity has received a state subsidy contrary to the terms of the European law on state aid. Given the variety of the forms of economic activity in the EU and the complexity of the law, exceptions to and exemptions from the rules have arisen; this has added to the complexity of the law.

Continuing Education and Training and the EU Framework on State Aid

2. Legal analysis of the regulation of state aid in the EU

Abstract

The purpose and defining conditions of the prohibition on state aid

The legal provisions on state aid in the European Union (EU) are part of the competition rules in the third part of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). They are set out in Articles 107 to 109 TFEU. Their aim is to prevent distortion of competition within the European market that may arise as a result of preferential treatment given by Member States to undertakings (i.e. businesses) located on their territory (Wallenberg/Schütte, 2016[1])1. On this basis, Art. 107(1) TFEU prohibits state aid as a matter of principle. There are, however, exceptions. The rationale for making exceptions is that EU legislators are aware that it is impossible to enforce the ban strictly. While state subsidy for undertakings will, in principle, always distort a free market, there are occasions when market failure or market conditions justify paying a subsidy.

The fundamental prohibition of EU state aid is set out in Article 107(1) TFEU which states that:

"any aid granted by a Member State or through State resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods shall, in so far as it affects trade between Member States, be incompatible with the internal market." (EC, 2009[2])

State aid is therefore deemed to have been granted if the following four defining characteristics are present:

it is a measure undertaken by a Member State;

the measure constitutes advantage/favourable treatment;

of a specific undertaking (that is, it is selective);

it thereby leads to the occurrence of (or, at least, the potential for) distortion of competition and impairment of inter-Community trade (Callies/Ruffert, 2016[3]) (Bartosch, 2016[4])2.

This chapter elaborates on the defining conditions of the prohibition on state aid.

Defining conditions of the prohibition on state aid

Funding from state resources

The prohibition in Art. 107(1) TFEU distinguishes between aid granted by the state on the one hand and aid granted through state resources on the other. According to the established case law of the European Court of Justice (ECJ), this distinction serves to:

"include in the concept of aid not only aid granted directly by the State but also aid granted by public or private bodies designated or established by the State" (ECJ, 1978[5]) (ECJ, 1982[6]) (ECJ, 1993[7])3.

According to ECJ case law, there are two prerequisites for the existence of this condition: the state origin of the means used for the aid on the one hand, and the imputability to the state of these means on the other. These conditions must be fulfilled cumulatively (ECJ, 2002[8]).4

According to the ECJ's definition, state resources are therefore "all the financial means by which the public authorities may actually support undertakings, irrespective of whether or not those means are permanent assets of the public sector” (ECJ, 2002[8]).5 Therefore, state resources according to Art. 107 (1) TFEU can include, in addition to resources of the Länder and the regional authorities, also resources of state‑owned undertakings (for instance, public HEIs).

The legal status of the institution responsible for granting the funds is therefore irrelevant. However, a prerequisite for qualification as a state measure is that the measure is imputable to the State. This does not derive solely from the fact that the institution is state-owned. It is also not sufficient that the State controls the institution or can exercise a dominant influence. Rather, state influence or state control over the granting of funds must be concretely demonstrated (Wallenberg/Schütte, 2016[1])6. Indicators are sufficient for this purpose (EC, 2016[9]).7 According to the ECJ judgment in the Stardust Marine case (ECJ, 2002[10]), for example, the factors to be examined are, in particular, the integration of the undertaking into the structures of the public administration; the nature of its activities and the exercise of them in normal competition with private operators; the legal status of the undertaking (i.e. whether it is governed by public law or general company law); the intensity of the supervision exercised by the public authorities over the management of the undertaking; and any other indicators showing, in the particular case, an involvement by the public authorities (or the unlikelihood of its non-involvement) in the adoption of a measure, having regard also to its scope, content or conditions. Case law sets high standards for the exclusion of imputability and tends towards a de facto presumption of imputability (Koenig/Förtsch, 2018[11]).8

This means, in principle, that funds for Brandenburg's HEIs may also be state funds.

Favour

The term "favour" under EU state aid law is much broader than the term "subsidy" (subvention) common in German law. A "favour" is understood to be not only positive benefits (such as subsidies), but any economic advantage, without adequate payment, which an undertaking would not have received under normal market conditions (i.e. without the intervention of the State) (ECJ, 1961[12]) (EuGH, 1994[13])9. These can be positive benefits or relief from burdens and charges that the undertaking would normally have to bear. The defining character is, therefore, to be understood as any granting of an economic advantage without appropriate (or fair market) consideration. Typical examples are: non-recoverable subsidies, low-interest or interest-free loans, the assumption of guarantees and the transfer of land or buildings.

In order to assess the central criterion of the appropriateness (Marktüblichkeit) of the favour, both ECJ and the European Commission (EC) have consistently applied the "private investor test", which compares the investment behaviour of the public sector with that of a hypothetical private market participant (ECJ, 1996[14]) (ECJ, 1999[15]) (EGC, 1991[16])10. Whether an economic favour is to be regarded as appropriate or inappropriate for the market is assessed according to whether a private investor acting economically in the role of the public authority would have carried out or would carry out a comparable measure in favour of the respective undertaking.

Selectivity

The defining character of state aid also presupposes that the measures confer an advantage on one particular undertaking or production sector over others, i.e. that they have a selective effect. The selectivity requirement is intended, in particular, to exclude from the scope of EU state aid rules such as the general economic policy measures of a Member State which benefit everyone and therefore do not favour one undertaking over another in competition (Bartosch, 2016[4])11.

Distortion of competition and impairment of inter-State trade

However, a favour in the sense of EU state aid rules is only deemed to have come into existence if it leads (or, at least, has the potential to lead) to a distortion of competition. Aid (in the sense of a selective grant through state resources) distorts competition only if that aid improves the position of the beneficiary or a third party in the applicable market to the detriment of their (potential) competitors. In order to determine whether this applies, it is necessary to compare the competitive situation before and after an (intended) subsidy is compared (ECJ, 1974[17]) (ECJ, 1980[18])12.

Ultimately, a measure must also affect trade between Member States in order to be covered by the prohibition rule of Article 107(1) TFEU. Trade in the sense of this requirement is to be understood as the entire trade in goods and services between Member States. An effect on trade exists if the state measure in question has an impact of some kind on trade between Member States or throughout the Union (ECJ, 1999[19]) (ECJ, 1994[20]) (ECJ, 1991[21]) (ECJ, 1988[22]).13

The meaning of the term “undertaking”

The EU ban on state aid set out in Art. 107(1) TFEU presupposes that certain undertakings or branches of production are favoured. The term "undertaking" is particularly important in the assessment of CET at HEIs under EU state aid law. The term "undertaking" is a functional concept; it applies to any entity engaged in an economic activity, regardless of its legal form or financing. Thus, it is possible that a unit – in this case a HEI – is not an "undertaking" with regard to one activity, (such as delivery of undergraduate degree programmes, which is not seen as an economic activity) but can be an "undertaking" with regard to another activity, such as contract research (which is an economic activity). Consequently, it is not the HEI that is to be regarded as a unit, but its individual activities.

Case law considers an economic activity to be "any activity consisting in offering goods and services in a given market" (ECJ, 2006[23]).14 A market connection is generally to be affirmed if the activity in question is not a purely sovereign activity and can, in principle, also be performed by a private undertaking. The intention to make a profit is not required for the activity to be deemed economic (ECJ, 2004[24]) (EGC, 2004[25]).15

The levels of EU rules on state aid

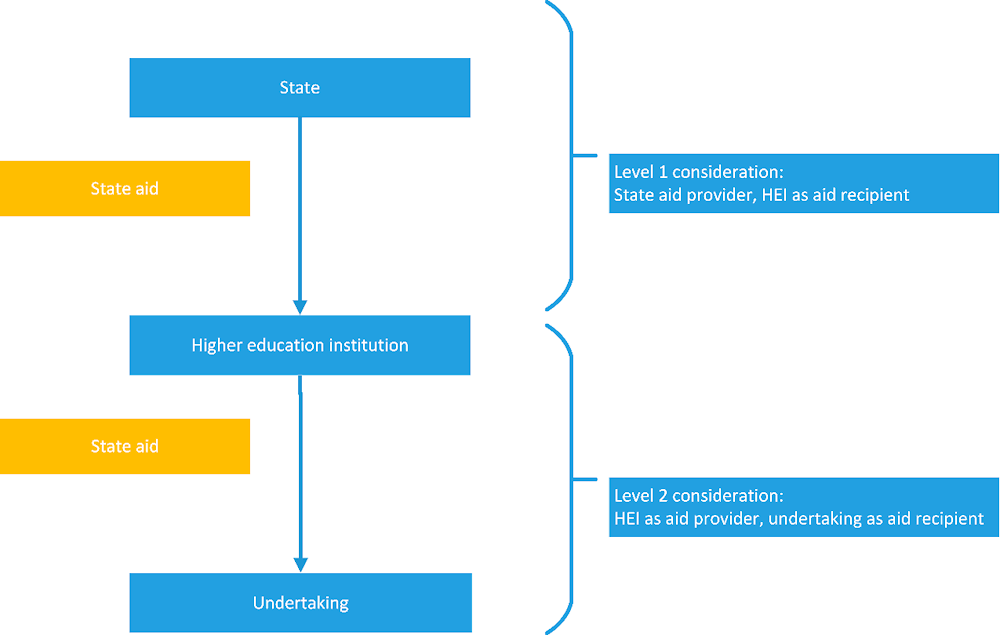

The notion of an undertaking therefore assumes economic activity. Every state-supported activity in the area of higher education must be considered on two levels of EU state aid law, as detailed in Figure 2.1, when deciding whether it is classified as economic or non-economic. It should be noted that a functional approach is decisive as even within an undertaking one area of activity can be economic while another is non-economic.

Figure 2.1. Levels of state aid under EU law – the example of HEI activities

Level 1 concerns the funding of the HEI by the government (either federal or a Land). HEIs can also carry out economic activities within the meaning of EU state aid law. That means that they then compete with other, private undertakings and, as a consequence, they are then treated as undertakings within the meaning of EU state aid law. As an example: assuming that any CET programme was assessed as being an economic activity, the HEI would then be acting as an undertaking and, therefore, any funding for the programme in question granted through public resources would be incompatible with the EU state aid law and thus, subject to the EU prohibition on state aid. This is because the HEI would be receiving funds from the state which it could then use to offer its courses more cheaply than its competitors and would therefore have an economic advantage. This would apply mutatis mutandi to other economic activities such as funding equipment or laboratories that are rented to third parties, or funding infrastructure or personnel which or who are used to conduct contract research or to provide services to other undertakings (EC, 2016[9]).16

Level 2 concerns indirect state aid. If a publicly financed HEI allows a private party to participate indirectly in its state funding, then that private party is seen to have been granted state aid. An example of indirect state aid of this kind arises if a HEI provides services funded by the state to a company without appropriate consideration. The regulation of indirect aid is intended to ensure that state funding of HEIs does not influence the market in a circuitous way and ultimately lead to a distortion of competition. With regard to CET at HEIs, this could be the case, for example, if a HEI as an “aid provider” passed on state funding to another undertaking as an “aid recipient” to provide services for CET programmes within a co-operation framework.

However, whether a state measure can be deemed to be at hand must be examined precisely in each individual case. It does not automatically follow from the fact that services are provided by the public HEI for the benefit of a private third party. Rather, the "Stardust Marine" criteria set by the ECJ must always be taken into account when attributing benefits to the state.

Exclusions and exceptions

The fulfilment of the defining conditions for EU state aid in Art. 107(1) TFEU generally results in the incompatibility (and therefore, the prohibition) of state aid. There are two types of exceptions to this prohibition. One is that an exclusion in the form of a general exemption can apply to the specific measure. The other is that the measure can be justified on the basis of a justifying exception to this prohibition granted by the EC. The consequences are the same: In both cases, the obligation to notify the measure to and obtain approval from the EC pursuant to the first sentence of Article 108(3) TFEU does not apply (notification and approval together constitute the “notification procedure”). Therefore, the state funds may be applied to the activity without a notification procedure.

Exemptions under EU state aid rules can be found in particular in the De Minimis Regulation (EU) No 1407/2013 (EC, 2013[26])17 and the General Block Exemption Regulation (EU) No 651/201418 (GBER) (EC, 2014[27]). The General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER) contains special exemptions for research and development (Art. 25 et ff. GBER). In addition, measures in favour of undertakings providing "services of general economic interest" may be exempted from the EU ban on state aid. This exemption is based on the Altmark Trans Judgment of the ECJ and the Almunia exemption decision by the EC (EC, 2012[28]).19 This decision is part of the Almunia package. It requires that the undertakings in question, as beneficiaries of the aid, must have been "entrusted" by the aid provider with the provision of these services. The application of these (and other possible) exemptions to the provision of CET in higher education is elaborated in Chapter 3 below.

If a state measure fulfils the defining criteria for EU state aid and no possibilities for exemption apply, the measure must be notified to the EC following a notification procedure. The EC then examines whether the measure constitutes state aid and whether it can be approved on the basis of the exceptions under Article 107(2) and (3) TFEU or on the basis of special regulations.

Consequences of incompatibility of aid

The consequences of receiving state benefits that are found to be incompatible with EU state aid rules can be severe. This is particularly true for publically funded HEIs. The granting and receipt of illegal subsidies can – if discovered – have negative consequences for the beneficiary at both EU and national levels.

If a state measure meets the criteria for EU state aid and there is no exemption or approval by the EC, there is a risk – at the EU level – that the EC will conduct a formal state aid investigation. The EC could become aware of the facts either on its own initiative – through reports in the press or through a publicly conducted discussion in political decision-making bodies –or as a result of a complaint by competitors of the aid recipient. If the EC concludes that incompatible aid has been granted, it orders the recovery of the aid by the granting Member State. The recovery order is retroactive; it covers the ten years preceding the decision of the EC. In the recovery order, the EC usually includes interest on the aid amount for the entire period for which it was received.

At the national level, the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof, BGH) has clarified in established case law that all legal acts underlying the incompatible granting of aid are void from the outset. This has the consequence that the acts underlying the aid – such as, for example, grant notices to HEIs, or guarantee declarations – are invalid and must be reversed. This legal consequence ensues automatically. Competitors of the aid recipient can bring an action for a declaratory judgment before a regional court (Landgericht) or an administrative court (Verwaltungsgericht) to have the contractual or grant relationship declared null and void.20

The prohibition of cross subsidies and requirement for separate accounting under EU state aid rules

As noted above, one area of HEI activity may be economic while another is non-economic (ECJ, 2006[29]).21 Therefore, it is necessary to prevent public funds that were intended for the non-economic activity of educational institutions from being used to subsidise economic activities. This is because cross-subsidisation can also constitute aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU and can therefore trigger legal consequences of incompatible aid.

According to Section 2.1.1. Point 18 of the R&D Framework of the EC, public funding of the non-economic activities of a research institution that carries out both economic and non-economic activities does not fall under the prohibition of state aid in Article 107 (1) TFEU:

"if… the two kinds of activities and their costs, funding and revenues can be clearly separated so that cross-subsidisation of the economic activity is effectively avoided." (EC, 2014[30])22

Aid is deemed to be granted if the economic activity is financed with public funds from the non-economic activity. The prohibition of cross-subsidisation then applies. Therefore, to avoid incompatibility with state aid rules, it is necessary to be able to prove the absence of cross subsidy by maintaining separate accounts for the economic and non-economic activities, so that, in the words of the R&D Framework of the EC

This requirement for the separation of accounts means that all revenues and expenses must be clearly attributable. It must be possible to clearly separate non-economic and economic activities and their costs, financing and revenues. Only then is there no danger of cross-subsidisation of economic activities by non-economic activities.

However, the HEI must contend with the prohibition of cross-subsidisation only if it engages in economic activities at all and is considered an enterprise in relation to these activities. With regard to the compatibility of HEIs' CET offerings with EU state aid rules, it is therefore first necessary to classify them as economic or non-economic. This classification is discussed in the following chapter.

References

[4] Bartosch (2016), EU-Beihilfenrecht, 2. Auflage.

[3] Callies/Ruffert (ed.) (2016), TEU/TFEU, 5. Auflage 2016.

[9] EC (2016), Commission Notice on the notion of State aid as referred to in Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, OJ C 262 of 19.07.2016.

[27] EC (2014), Commission Regulation (EU) Nr. 651/2014 of 17.06.2014 declaring certain categories of aid compatible with the internal market in application of Articles 107 and 108 of the Treaty.

[30] EC (2014), Communication from the Commission – Framework for State aid for research and development and innovation, OJ C 198 of 27.06.2014.

[26] EC (2013), Commission Regulation (EU) No 1407/2013 of 18.12.2013 on the application of Articles 107 and 108 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to de minimis aid.

[28] EC (2012), Commission Decision of 20.12.2011 on the application of Article 106(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to State aid in the form of public service compensation granted to certain undertakings entrusted with the operation, 2012/21/EU.

[2] EC (2009), Core provisions of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/legislation/compilation/a_01_03_11_en.pdf.

[29] ECJ (2006), Judgment of 01.07.2006 – C-49/07, BeckRS.

[23] ECJ (2006), Judgment of 23.03.2006, C-237/04, BeckRS.

[24] ECJ (2004), Judgment of 16.03.2004 – C-264/01, BeckRS.

[10] ECJ (2002), Judgment of 16.05.2002 – C-482/99, EuZW 2002, 468.

[8] ECJ (2002), Judgment of 16.05.2002 – C-482/99, EuZW 2002, 468, 470.

[19] ECJ (1999), Judgment of 17.06.1999 – C-75/97, BeckRS.

[15] ECJ (1999), Judgment of 29.04.1999 – C-342/96, BeckRS.

[14] ECJ (1996), Judgment of 11.07.1996 – C-39/94, BeckRS.

[20] ECJ (1994), Judgment of 14.09.1994 – C-278/92, BeckRS.

[7] ECJ (1993), Judgment of 17.03.1993 – C-72/91.

[21] ECJ (1991), Judgment of 21.03.1991 – C-303/88, BeckRS.

[22] ECJ (1988), Judgment of 13.07.1988 –102/87, BeckRS.

[6] ECJ (1982), Judgment of 13.10.1982 – C-213/81.

[18] ECJ (1980), Judgment of 17.09.1980 – 730/79, NJW.

[5] ECJ (1978), Judgment of 24.01.1978 – 82/77.

[17] ECJ (1974), Judgment of 02.07.1974 – 173/73, BeckRS.

[12] ECJ (1961), Judgment of 23.02.1961 – 30/59, 72052, BeckRS 2004.

[25] EGC (2004), Judgment of 14.10.2004 – T-137/02, BeckRS.

[16] EGC (1991), Judgment of 21.01.1991 – T-129/95, BeckRS.

[13] EuGH (1994), Judgment of 15.03.1994 – C-387/92, BeckRS 2004.

[1] Grabitz/Hilf/Nettesheim (ed.) (2016), Das Recht der Europäischen Union, Werkstand: 59. Ergänzungslieferung Juli 2016.

[11] Streinz (ed.) (2018), EUV/AEUV, 3. Auflage 2018.

Notes

← 1. See Art. 107 AEUV Rn. 10.

← 2. See Bartosch, EU-Beihilfenrecht, 2. Auflage 2016, Art. 107 AEUV Rn. 1 ff.; Cremer in: Callies/Ruffert, EUV/AEUV, 5. Auflage 2016, Art. 107 Rn. 10 ff.

← 3. ECJ, Judgment of 24.01.1978 – 82/77, marginal 23-25 in juris; ECJ, Judgment of 13.10.1982 – C-213/81, marginal 22 in juris; ECJ, Judgment of 17.03.1993 – C-72/91, marginal 19 in juris.

← 4. ECJ, Judgment of 16.05.2002 – C-482/99, EuZW 2002, 468, 470, marginal 24.

← 5. See marginal 37.

← 6. See Art. 107 AEUV marginal 33.

← 7. See p.10. marginal 41ff.

← 8. See: Koenig/Förtsch in: Streinz, EUV/AEUV, 3. Auflage 2018, Art. 107 Rn. 62.

← 9. ECJ, Judgment of 23.02.1961 – 30/59, BeckRS 2004, 72052; EuGH, Judgment of 15.03.1994 – C-387/92, BeckRS 2004, 76937, marginal 13.

← 10. ECJ, Judgment of 11.07.1996 – C-39/94, BeckRS 2004, 76964, Rn. 60; Judgment of 29.04.1999 – C-342/96, BeckRS 2004, 76583, marginal 41; EGC, Judgment of 21.01.1991 – T-129/95 et al, BeckRS 1999, 55045, marginal 104 ff.

← 11. Bartosch, EU-Beihilferecht, 3. Auflage 2020, Art. 107 AEUV, marginal 135.

← 12. ECJ, Judgment of 02.07.1974 – 173/73, BeckRS 2004, 71968, marginal 36/40; Judgment of 17.09.1980 – 730/79, NJW 1981, 1152, 1152 f.

← 13. See ECJ, Judgment of 17.06.1999 – C-75/97, EuZW 1999, 534, 537, marginal 47; Judgment of 14.09.1994 – C-278/92, BeckRS 2004, 75925, marginal 40; Judgment of 21.03.1991 – C-303/88, BeckRS 2012, 80903, marginal 27; Judgment of 13.07.1988 –102/87, BeckRS 2004, 70634, marginal 19.

← 14. ECJ, Judgment of 23.03.2006, C-237/04, BeckRS 2006, 70228, marginal 28 f. with reference to Judgments of 23.04.1991 – C-41/90, NJW 1991, 2891, 2891f., maginal 21; Judgment of 21.09.1999 – C-67/96, marginal 7 – Albany; of 12.09.2000, adjunct marginals. C-180/98 to C-184/98, marginal 74 – Pavlov et al., and of 01.07.2006 – C-49/07, WuW 2008, 1129, 1130, marginal 22.

← 15. ECJ, Judgment of 16.03.2004 – C-264/01, EuZW 2004, 241, 243, marginal 46; EGC, Judgment of 14.10.2004 – T-137/02, BeckRS 2004, 78076, marginal 50ff.

← 16. See Commision Notice on the notion of State aid, OJ C 262 of 19.07.2016, p. 1 ff., marginal 218.

← 17. Commission Regulation (EU) No 1407/2013 of 18.12.2013 on the application of Articles 107 and 108 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to de minimis aid, OJ L 352 of 24.12.2013, So 1.

← 18. Commission Regulation (EU) Nr. 651/2014 of 17.06.2014 declaring certain categories of aid compatible with the internal market in application of Articles 107 and 108 of the Treaty, OJ. L 187 of 26.06.2014, p. 1.

← 19. 2012/21/EU: Commission Decision of 20.12.2011 on the application of Article 106(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to State aid in the form of public service compensation granted to certain undertakings entrusted with the operation of services of general economic interest, OJ L 7 of 11.01.2012, p. 3.

← 20. For examples of civil action for declaratory ruling on incompatible aid: BGH, Judgment of 12.10.2006 – III ZR 299/05, NVwZ 2007, 973; BGH, Judgment of 24.10.2003 – V ZR 48/03, EuZW 2004, 254; BGH, Rulling of 20.01.2004 – XI ZR 53/03, EuZW 2004, 252.

← 21. See e.g ECJ, Judgment of 01.07.2006 – C-49/07, BeckRS 2008, 70730, marginal 25.

← 22. Communication from the Commission – Framework for State aid for research and development and innovation, OJ C 198 of 27.06.2014, p. 1.