Both income and expenditure-based tax incentives for research and development (R&D) are increasingly used to promote business R&D. Expenditure-based incentives are widely used; with 33 out of the 38 OECD jurisdictions offering tax relief on R&D expenditures in 2023, compared to 19 in 2000. Income-based incentives are slightly less widely offered; with 21 OECD countries providing these incentives, an increase from 4 in 2000.

Most jurisdictions use a combination of direct support and tax relief to support business R&D, but the policy mix varies. Over time, there has been a shift towards a more intensive use of expenditure-based R&D tax incentives to deliver financial support for business R&D. Income-based incentives are often used together with expenditure-based incentives. With the exception of Luxembourg, every country with an income-based incentive also has an expenditure-based incentive.

The effective average tax rate (EATR) for R&D incorporating expenditure-based tax incentives in 2023 was lowest in Ireland, Poland and Lithuania, providing greater tax incentives for firms to locate R&D investment in these jurisdictions. The average across the 48 jurisdictions covered in the baseline scenario was 14.2%, or 7.1 percentage points below the standard tax treatment.

The cost of capital for R&D in 2023 incorporating expenditure-based tax incentives was lowest in Portugal, Poland and France where these jurisdictions provide greater tax incentives for firms to increase their R&D investment. The average across the 48 jurisdictions covered in the baseline scenario was 0.3%, or 2.8 percentage points below the standard tax treatment.

For profitable small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), implied marginal R&D tax subsidy rates were highest in Colombia, Iceland and Portugal in 2022.

The effective average tax rate (EATR) for R&D incorporating income-based tax incentives in 2023 was lowest in Malta. The average across the 48 jurisdictions covered in the baseline scenario was 12.7%, or 6.8 percentage points below the standard tax treatment.

The cost of capital for R&D in 2023 incorporating income-based tax incentives was lowest in Israel. The average across the 48 jurisdictions covered in the baseline scenario was 3.9%, or 0.25 percentage points below the standard tax treatment.

While the income-based and expenditure-based models are not directly comparable, these indicators highlight that expenditure-based incentives provide a relatively greater impact on the cost of capital compared to income-based incentives.

R&D tax incentives have become more generous, on average, over time. This is due to the higher uptake and increased generosity of R&D tax relief provisions. While this trend stabilised between 2013 and 2019, an increase in generosity is again observed from 2020 and maintained through to 2022. The generosity of income-based incentives has increased over time, but has remained more stable since 2019.

Corporate Tax Statistics 2024

5. Tax incentives for research and development

Key insights

Incentivising investment in R&D by businesses ranks high on the innovation policy agenda of many jurisdictions. R&D tax incentives have become a widely used policy tool to promote business R&D over recent decades. Several jurisdictions offer them in addition to direct forms of support such as R&D grants or government purchases of R&D services. R&D tax incentives can provide relief to R&D expenditures, such as the wages of R&D staff and/or to the income derived from R&D activities, such as patent income. This chapter covers both indicators referred to in this section relate to expenditure-based R&D tax incentives and income-based R&D tax incentives to R&D and innovation. Further information on income-based tax incentives is available in the section on Intellectual Property (IP) regimes. In this section, income-based tax incentives cover IP regimes which apply only to IP income as well as regimes that also extend support to other forms of non-IP income (dual category regimes). The significant variation in the design of expenditure-based R&D tax relief provisions across jurisdictions and over time affects the implied generosity of R&D tax incentives.

Indicators of R&D tax incentives

The Corporate Tax Statistics database incorporates two sets of R&D tax incentives indicators that offer a complementary view of the extent of R&D tax support provided through expenditure-based R&D tax incentives. A third set of indicators focus on income-based R&D tax incentives.

The first set of indicators reflects the cost of expenditure-based tax incentives to the government:

Government tax relief for business R&D (GTARD) includes estimates of foregone revenue (and refundable amounts) from national and subnational incentives, where applicable and relevant data are available. This indicator is complemented with figures on direct funding of business R&D to provide a more complete picture of total government support to business R&D investment.

Both indicators, compiled by the OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation, are available for 48 jurisdictions – OECD jurisdictions and 10 partner economies – for the period 2000-2021.

The second set of indicators are synthetic tax policy indicators that capture the effect of expenditure-based R&D tax incentives on firms’ investment costs (see Box 5.1):

The EATR for R&D measures the impact of taxation on R&D investments that earn an economic profit.

The user cost of capital for R&D measures the return that a firm needs to realise on an R&D investment before tax to offset all costs and taxes that arise from the investment, making zero economic profit.

Implied marginal tax subsidy rates for R&D, calculated as 1 minus the B-Index, reflect the design and implied generosity of R&D tax incentives to firms for an extra unit of R&D outlay. The B-Index captures the extent to which different tax systems reduce the effective cost of R&D.

The third set of indicators are also synthetic tax policy indicators, but capturing the effect of income-based R&D tax incentives on firms’ investment costs.

As for expenditure-based tax incentives, EATRs, the user cost of capital, and the B-index are calculated for income-based tax incentives.

The second and third set of indicators are available for 48 countries, including OECD jurisdictions and ten partner economies. Indicators of the user cost of capital and the EATR for expenditure-based incentives are available for 2019-2022, while for income-based they are available from 2000-2022. All indicators refer to large businesses who are able to fully utilise their tax benefits. Indicators of the large companies account for the bulk of the R&D in most OECD countries (OECD, 2022a[1]; Dernis et al., 2019[2]). The EATR and user cost for R&D are produced by the OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration and the OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation. The B-Index for expenditure-based incentives, which is, compiled by the OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation, covers a wider group of firm scenarios (SMEs; large firms; profit and loss-making) over the 2000-2022 time period.

The indicators of ETRs and cost of capital for R&D in this section chapter extend the corporate ETRs shown in the previous chapter section to include internally generated R&D assets, i.e., those that are the result of a firms’ own R&D.1

Expenditure-based tax incentives

Government support for business R&D

Indicators of government tax relief for business R&D combined with data on direct R&D funding provide a more complete picture of governments’ efforts to support business expenditure on R&D (BERD). Together, these indicators facilitate the cross-jurisdiction comparison of the policy mix provided by governments to support R&D and the monitoring of any changes over time.

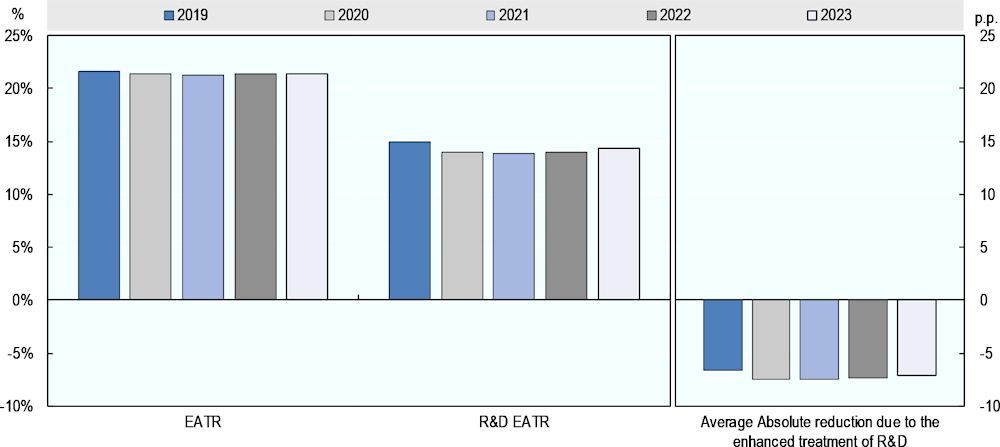

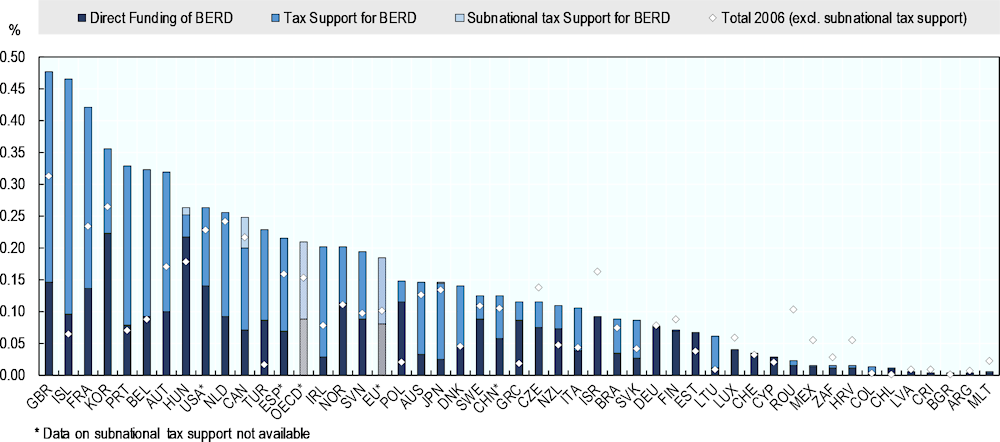

Figure 5.1. Direct government funding and expenditure-based tax support for business R&D (BERD), 2021

As a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP)

Data and notes: https://oe.cd/rdtax. Time series data available for 2000-2021.

Source: OECD (2023), R&D Tax Incentive Database, http://oe.cd/rdtax, April 2024, (accessed in May 2024).

Between 2006 and 2021, total government support (direct and national tax support) for business R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP increased in 33 out of 48 jurisdictions for which relevant data are available. The United Kingdom, Iceland and France provided the largest levels of support in 2021 (Figure 5.1). Subnational R&D tax incentives accounted for 25% of total tax support in Canada in 2021, playing a comparatively smaller role in Hungary and Japan (nearly 5% and 1% of total tax support, respectively).

Most jurisdictions integrate both direct and indirect forms of R&D support in their policy mix, but to different degrees. In 2021, 19 OECD jurisdictions offered more than 50% of government support for business R&D through the tax system, and this percentage reached 75% or more in seven OECD jurisdictions: Australia, Colombia, Ireland, Iceland, Japan, Lithuania and Portugal. Eight OECD jurisdictions relied solely on direct support in 2021. These are Costa Rica, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Israel, Latvia, Luxembourg and Switzerland.

Combining time-series estimates of GTARD and direct funding helps illustrate variations in governments’ policy mix over time. In recent years, many jurisdictions have granted a more prominent role to R&D tax incentives. Compared to 2006, the share of tax support in total government support in 2021 increased in 29 out of 38 OECD jurisdictions for which data are available. This implies a general shift towards less discretionary forms of support for business R&D, with some exceptions, e.g., Canada and Hungary increased their reliance on direct support.

Measuring the preferential tax treatment for R&D

R&D tax incentives exhibit very heterogeneous design features across jurisdictions, which come on top of existing differences in standard corporate income tax systems. Indicators based on forward-looking effective tax rates are therefore useful to capture the effect of taxation on firms’ R&D in a synthetic manner investment incentives. By fixing the composition of the R&D investment, they enable comparisons of the preferential tax treatment provided for R&D investments across jurisdictions.

This database provides a toolbox for policymakers to analyse the incentives that firms face through the tax system to increase their R&D investment in a given country or to (re)locate their R&D functions, taking into account both the impact of underlying corporate taxation as well as specific R&D tax incentives. Indicators calculating the EATR and the cost of capital for R&D are useful to analyse decisions at the extensive margin (e.g., whether or where to invest in R&D) and at the intensive margin (e.g., how much to invest in R&D), respectively. These indicators focus on the incentives faced by large firms among which R&D is heavily concentrated (OECD, 2022a[1]; Dernis et al., 2019[2]) and assume that firms are able to use their tax benefits in full.

Governments often introduce specific provisions to target particular firm types and to promote R&D among firms that may not be able to fully use their tax benefits. The B-Index, tightly related to the cost of capital, is another useful indicator to analyse R&D investment decisions at the intensive margin and to compare differences in the implied R&D tax subsidy rates among different firm types (SMEs and large firms) and profit scenarios (profit and loss). Box 5.1 provides an overview of the three indicators.

Box 5.1. Three complementary indicators of the generosity of R&D tax support

The cost of capital, the B-Index and the EATR are conceptually linked and rely on the same modelling of R&D tax incentives. As indicators of the cost of R&D for a marginal unit of R&D outlay, the B-Index and cost of capital are used in the economic literature to assess firms’ R&D investment decisions at the intensive margin, e.g., how much to invest in R&D.

The B-Index offers a way of comparing the generosity of R&D tax incentives in reducing the upfront investment cost of an R&D investment while abstracting from the financing of the investment. By focussing on the tax component of the cost of capital, the B-index does not require assumptions on the depreciation rate of R&D, which is typically difficult to measure, and directly displays the variation in the tax treatment induced by R&D tax incentives.

The cost of capital complements and extends the B-Index indicator by accounting for additional costs and taxes relevant to the R&D investment. Since the cost of capital can in principle account for a variation in economic depreciation across assets and financing options, it also facilitates the analysis of different types of R&D projects. Finally, the cost of capital is also a stepping-stone in the calculation of the EATR.

The EATR complements previous indicators by capturing the effect of taxation on profitable investments. This makes the EATR the relevant indicator to assess of investment decisions at the extensive margin (where or whether to invest in R&D). Together, the three indicators offer a complementary set of indicators to assess the impact of taxation on firms’ R&D investment decisions.

Source: González Cabral, Appelt and Hanappi. (2021[3])

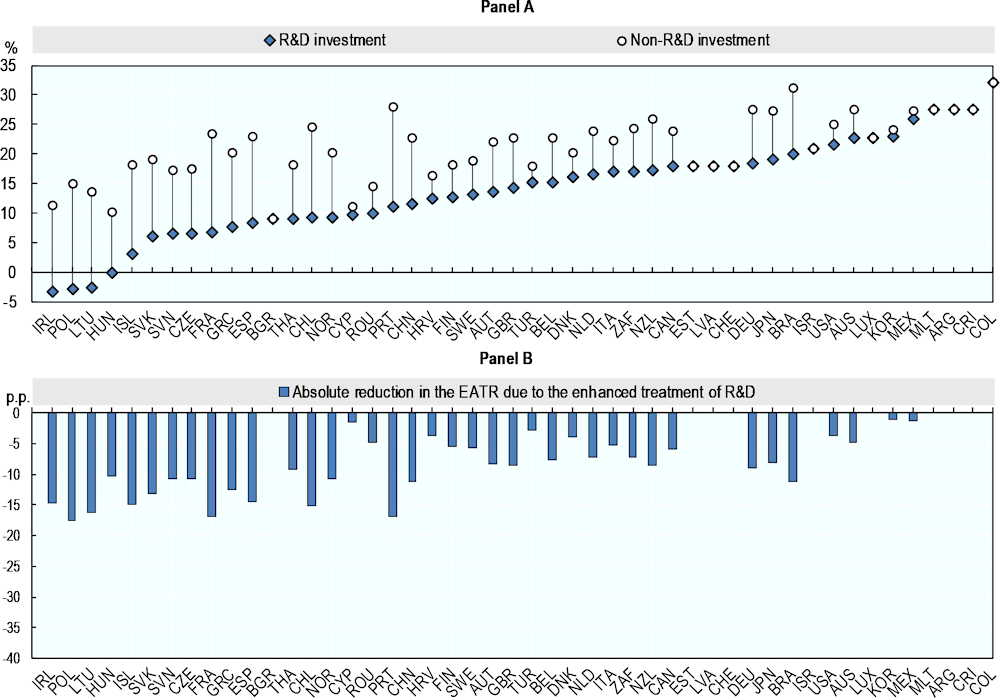

Incentives at the extensive margin

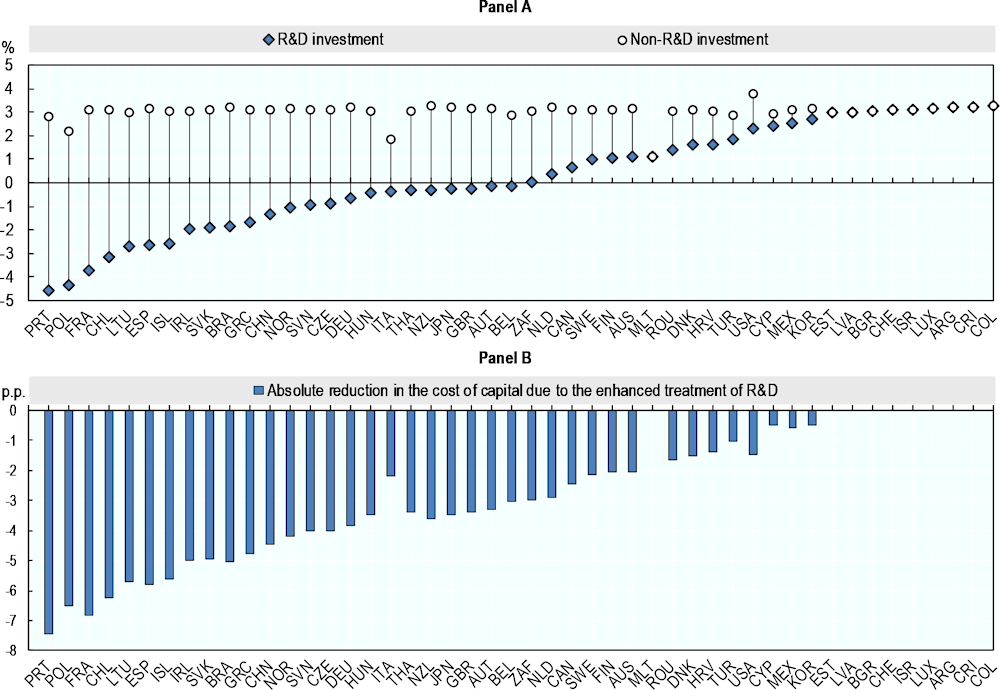

Comparing the EATRs for R&D investments across jurisdictions gives insights into the expenditure-based incentives provided by the tax system for the location of profitable R&D investments (Figure 5.2, Panel A). The lowest EATRs for R&D investments carried out by large firms are observed in Ireland, Poland and Lithuania, while the highest EATRs for R&D are observed in Argentina, Costa Rica and Colombia. Estimates of the EATR are typically lower for jurisdictions with lower STRs or more generous provisions affecting the tax base, including both standard tax provisions and those specific to R&D investments.

To assess the preferential tax treatment for R&D investments in relation to other investments, it is useful to calculate the EATR for a comparable investment to which expenditure-based R&D tax incentives do not apply. Where available, expenditure-based R&D tax incentives decrease the effective cost of R&D and reduce firms’ EATRs, as shown in Panel A by the fact that the diamonds lie lower than the circles. The extent of the reduction, shown in Figure 5.2 Panel B, is explained by the generosity of the expenditure-based R&D tax incentives in each jurisdiction, which is closely linked to the design of these provisions. This figure includes only the impact of tax provisions in supporting R&D: modest reductions, as in Sweden or the United States, may reflect a higher reliance on direct forms of government support for R&D.

By taking the difference between the two EATRs, it is possible to gauge the preferential expenditure-based tax treatment offered to R&D in a given jurisdiction, in isolation from baseline tax provisions available to all types of investments. From a within country perspective, the preferential tax treatment for R&D investments is greatest in France followed, by Poland and Portugal. The absence of bars, as in Costa Rica or Luxembourg, indicates that no preferential expenditure-based tax treatment for R&D is available in the jurisdiction relative to other investment types.

Figure 5.2. The effective average tax rate for R&D including expenditure-based tax incentives, 2023

Note: Results refer to a macroeconomic scenario 3% real interest rate and 1% inflation and refer to an investment financed by retained earnings including the effect of allowances for corporate equity where available. In the non-R&D case, the EATRs lie close to the statutory tax rate (STR) due to the large current component in the R&D investment (see Box 5.1), except when an allowance for corporate equity is available.

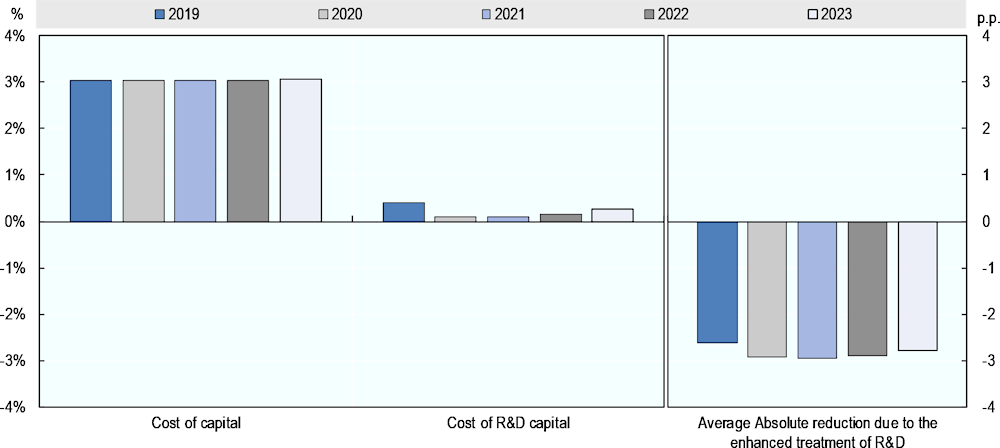

Figure 5.3. Changing distribution of the average EATR for R&D, 2019-2023

The EATR for R&D including expenditure-based tax incentives has modestly declined over time and while preferential tax treatment has increased compared to 2019, recent years show signs of stabilisation and even small declines in recent years. Figure 5.3 displays average changes to the EATR over time. Consistent with the trends outlined in the baseline effective tax rate (ETR) (Chapter 4), the EATR in the absence of R&D tax incentives have tended to modestly decline over the period covered. A similar but more substantial trend is observable for the EATR once expenditure-based R&D tax incentives are included. The EATR for R&D declined from an average of 14.9% in 2019 to 13.9% in 2020 increasing slightly to 14.2% in 2023. Changes over time in the EATR for R&D are due to first time introductions of expenditure-based incentives (Germany and Denmark in 2020, Finland 2021 or Cyprus in 2022) or changes to the generosity of R&D tax incentives (the Slovak Republic in 2020 and 2022, Italy in 2021 or Poland in 2022). In 2023, expenditure-based R&D tax incentives reduce the average EATR by 33.4%, from 21.3% to 14.2%. Over time, preferential tax treatment has increased between 2019 and 2020 and remained relatively stable between 2020 and 2023.

Incentives at the intensive margin

Once established in a given location, firms decide upon the level of investment with reference to tax provisions that affect the intensive margin. The cost of capital for R&D is one relevant indicator of tax incentives at the intensive margin (see Figure 5.4). Across the jurisdictions considered Portugal, Poland and France are the jurisdictions providing greater incentives through the tax system to increase the volume of R&D. Among jurisdictions offering R&D tax support, estimates of the cost of capital for R&D are highest in Argentina, Costa Rica and Colombia. Estimates of the cost of capital for R&D capture both the variability in standard tax provisions and those specific to R&D investments. R&D tax incentives reduce the cost of capital, with the extent of the reduction being affected by the generosity of R&D tax incentives. The absolute difference between the cost of capital for an R&D investment and a comparable non-R&D investment provides a within-country indication of the magnitude of R&D tax relief to marginal R&D investments, net of the standard tax treatment available to all investments. This allows the preferential tax treatment for R&D to be isolated. The largest reductions in the cost of capital for R&D investments are observed in Poland, Portugal and France, which are among the jurisdictions with the lowest cost of capital estimates.

Figure 5.4. The cost of capital for R&D, 2023

Note: Results refer to a macroeconomic scenario incorporating a 3% real interest rate and a 1% inflation rate and refer to an investment financed by retained earnings including the effect of allowances for corporate equity where available. In the non-R&D case, the cost of capital lies close to the real interest rate due to the large current component in the R&D investment (see Box 5.1), except when an allowance for corporate equity is available.

Tax incentives significantly reduce the cost of capital for R&D and while preferential tax treatment has increased since 2019, recent years show a more stable trend. Figure 5.5 compares the evolution of the cost of R&D capital during the period 2019-2023. Similar to the EATR, the cost of capital is affected by changes in the availability of R&D tax incentives and their design. The cost of R&D capital showed a significant decline from an average of 0.4% in 2019 to 0.1% in 2020 and has increased to 0.3% in 2023. Since 2020, the implied tax subsidies have remained relatively stable through 2021, declining slightly in 2022 and 2023. Tax incentives reduced the cost of R&D capital by 94% in 2022 and by 89% in 2023.

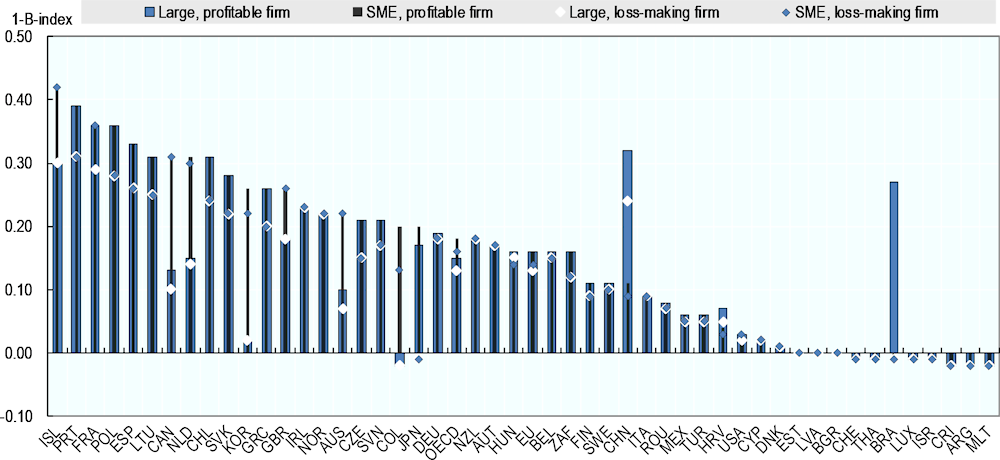

The heterogeneity of implied R&D tax subsidy rates

R&D tax benefits may vary with business characteristics such as firm size and profitability. Implied marginal tax subsidy rates for R&D, based on the B-Index indicator (1-B-Index), provide a synthetic indicator of the expected generosity of the tax system towards an extra unit of a firm’s R&D investment (Figure 5.6). The more generous the R&D tax incentive is, the greater the value of the implied tax subsidy. This indicator shows differences in tax benefits between large and SMEs and firms in profit and loss-making positions. In jurisdictions, such as Australia or Canada, that offer enhanced tax relief provisions for SMEs that are not available to large firms, the indicator shows the difference in the implied subsidies offered to each firm type.

Figure 5.5. Changing distribution of the average cost of R&D capital, 2019-2023

Figure 5.6. Implied marginal tax subsidy rates on business R&D expenditures, 2023

Note: Data and notes: https://oe.cd/ds/rdtax. Modelling assumes a nominal interest rate of 10%.

Source: OECD (2023), R&D Tax Incentive Database, http://oe.cd/rdtax, April 2024, (accessed in May 2024).

Refunds and carry-over provisions are common means of promoting R&D in firms that would not otherwise be able to utilise the support provided by the tax system. This may arise when firms do not have sufficient tax liability to offset earned deductions or do not draw a profit. Implied marginal subsidy rates are calculated under two scenarios: profitable firms (which are able to fully utilise the tax support available to them) and loss-making firms (which may not be able to fully utilise the tax support available to them) to reflect the varying impact of these provisions. Refundability provisions such as those available in Austria and Norway align the subsidy for profitable and loss-making firms. Compared to refunds, carry-over provisions, such as those available in Spain or Portugal, imply a lower subsidy for loss-making firms compared to profitable firms as the benefits may only be used in the future. In jurisdictions where no such provisions exist, such as Brazil or Japan, loss-making firms experience a full loss of tax benefits.

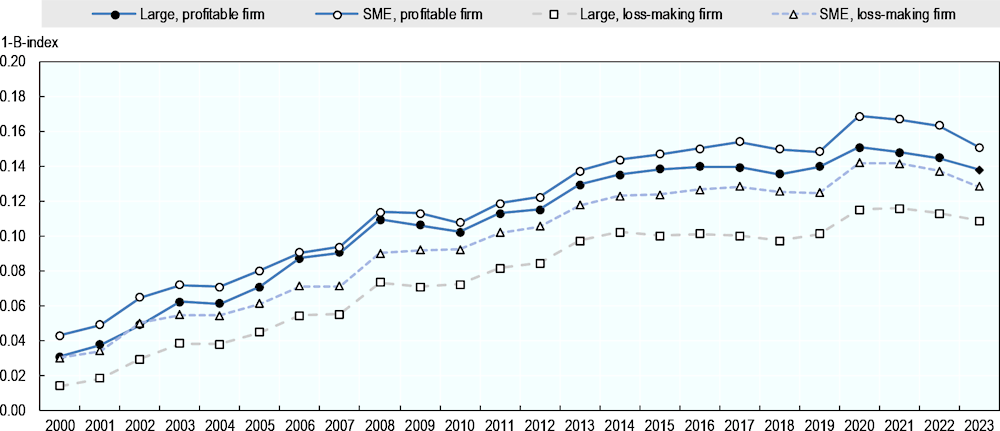

Figure 5.7. Evolution of the implied marginal tax subsidy rates R&D, 2000-2023

Note: Data and notes: https://oe.cd/ds/rdtax. Modelling assumes a nominal interest rate of 10%.

Source: OECD (2023), R&D Tax Incentive Database, http://oe.cd/rdtax, April 2023, (accessed in September 2023).

R&D tax incentives are on average higher for SMEs and profit-making firms. Figure 5.7 offers an overview of the evolution of implied marginal tax subsidy rates across four categories of firms in the period 2000-2023: SMEs and large firms in profit or loss. The generosity of expenditure-based R&D tax incentives rises over time for all firm types. Although between 2013 and 2019 subsidy rates had stabilised, a step increase is observed in 2020. There is some evidence that implied subsidies have declined in recent years. Persistently higher subsidy rates are offered over time to SMEs compared to large firms in both the profit scenarios considered; and to profitable than loss making firms for both firm types. This suggests that jurisdictions tend to provide greater tax benefits to SMEs than large firms.

The evolution of the data depicted in Figure 5.7 also reflects heterogeneity in the magnitude of year-on-year changes. The largest increase in implied marginal tax subsidy rates occurred between 2007-2008, at the time of the financial crisis, (an increase of about 2.0 p.p. throughout all four categories) and 2019-2020 (around 1.6 p.p.), at the time of the COVID pandemic.

Income-based tax incentives

Income-based tax incentives for R&D and innovation feature in the policy mix of many OECD and IF member countries. In 2023, 21 out of 38 OECD countries offer income-based tax incentives to R&D and innovation, representing a substantial increase from 4 countries in 2000. With the exception of Luxembourg, all of these countries offer income-based tax incentives together with expenditure-based tax incentives outlined in the previous section such as R&D tax credits. While expenditure-based tax incentives provide tax relief based on R&D expenditures, income-based tax incentives seek to reduce the taxation of the qualifying income from qualified intangibles resulting from R&D and related activities. They do so by offering a preferential tax rate to the income arising from certain types of R&D intangibles. Income-based tax support can be targeted solely to income from IP assets or extend support to both IP income and other forms of non- IP income (dual category regimes).

The tax treatment of intangible investments varies with firms’ decisions on the acquisition, protection and commercialisation of the R&D intangible. This stems from the fact that these tax incentives differ in the types of assets and income they provide relief to and on the conditions that they impose on the development of the asset (González Cabral et al., 2023[4]). The way in which firms acquire an intangible, by doing R&D internally, by outsourcing R&D or by acquiring pre-existing R&D intangible can often determine eligibility for preferential tax relief. The standard tax treatment of costs associated with internally developed R&D intangibles, which are often expensed, is also different from the tax treatment of costs associated with pre-existing intangibles acquired from other firms, which are typically capitalised akin to tangible assets.

The model on which the results in this section are based develops ETRs for different types of approaches through which a firm can come to own an intangible asset (acquired, outsourced or internally generated). Internally generated assets are the focus of the results presented below. The model assumes that the R&D and commercialisation of the R&D intangible occur in the same country. Four key design features of income-based tax incentives are captured: the preferential tax rate, the treatment of ongoing IP expenses, the treatment of past IP expenses and the presence of development conditions through the nexus ratio introduced by Action 5 of the BEPS Project. The model incorporates a gestation lag between the deployment of the R&D investment and the moment the asset starts generating income. The investment is considered to take the form of current expenditure, e.g., the labour costs of hiring researchers, which is in contrast to the expenditure-based incentives where a capital component is incorporated. Additional details on the calibration of the model are contained in González Cabral et. al. (2023[5]).

The main estimates are derived for the case of an intangible asset that is 1) the result of the firms’ own R&D, 2) that represents a qualifying intangible asset and 3) that the firm decides to commercialise in the same country (e.g. licenses it out to other domestic performers) or keeps the IP intangible for their own use. When preferential treatment is modelled, the premise is that the asset is deemed to qualify for income-based tax relief and is both a successful investment generating a return. The firm is assumed to have other sources of income (i.e., it is not tax exhausted) and applies for income-based tax support for the first time upon receiving income from the qualifying intangible asset. Where different countries have different income-based tax incentives, these incentives are recorded separately and reported separately unless specified (additional details are provided in González Cabral et. al. (2023[5]) and González Cabral et. al. (2023[6])).

Incentives at the extensive margin

This section develops EATRs for an investment in an internally generated R&D intangible asset, which give insights into the extensive margin of investment decisions, such as firms choosing investment locations across jurisdictions. This provides insights into how the impact of income-based tax incentives may affect the location of the intangible profitable R&D investments. EATRs give insights into the extensive margin of investment decisions, such as firms choosing investment locations across jurisdictions.

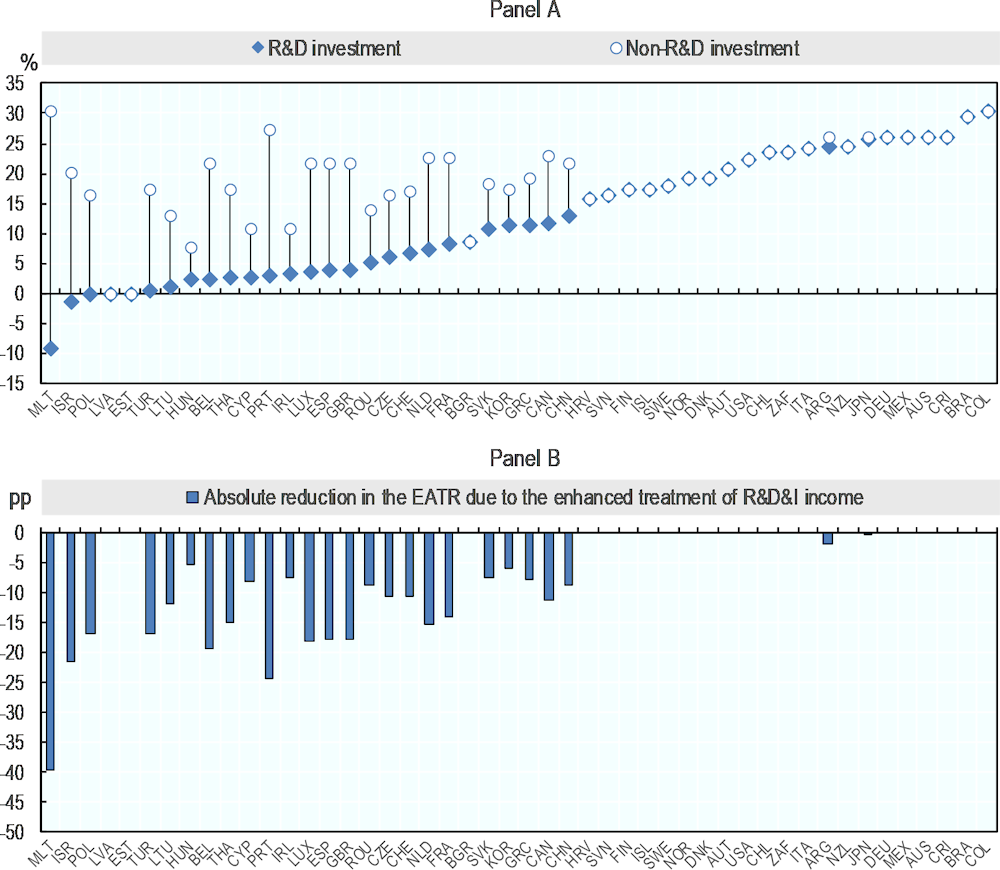

At the sample average, income-based tax incentives reduce the overall tax liability that the firm faces on income from an R&D investment substantially, with significant variation across countries (see Figure 5.8). EATRs fall from an average of EATR of 19.6% without support to an EATR of 12.2% including income-based tax incentives. Income-based tax incentives imply a reduction in the EATR by 7.2 percentage points on average, or a reduction of 37%.

The EATR for an income-tax-incentive-supported internally generated R&D investment intangible asset supported through income-based tax incentives ranges from -9% to 30.6% across the countries considered. In the absence of income-based support the rates would vary from 8% to 31%. Among the countries considered, the lowest EATRs are observed in Malta, Israel (ISR1-S, ISR2-S) and Türkiye (TUR1), while the highest rates are observed in Colombia, Brazil and Costa Rica. Countries with the lowest EATR tend to offer the greatest tax-related incentives to investments in internally generated intangibles.

Figure 5.8. EATR for internally generated R&D intangibles, 2023

Estimates of the implied tax subsidy from Income-based tax incentives, inframarginal investments (EATR)

Note: The estimates consider an R&D investment with a gestation lag of two years after which the intangible asset starts generating profits. Baseline refers to an equivalent investment that does not benefit from income-based tax support. Preferential tax treatment is obtained by the difference between the cost of capital including income-based support and the baseline. The results assume all IP income qualifies for relief. CHE assumes that the firm has sufficient other income (non-qualifying IP or non-IP income) that is taxed at higher rates so that it is not subject to the 70% maximum relief limitation. CHE* assume that the maximum relief limitation is binding.

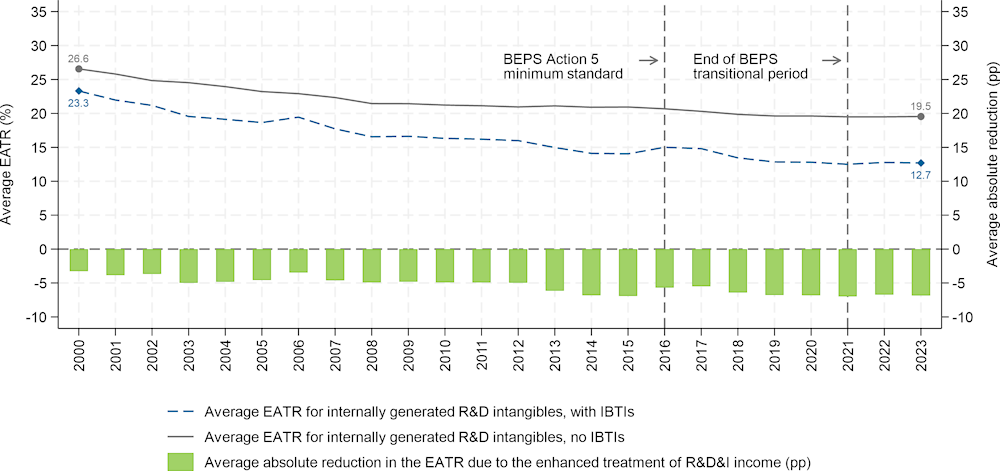

The average taxation of internally generated R&D assets has continuously declined over the past two decades. As shown in Figure 5.9, the average EATR on internally generated R&D intangibles has fallen in the OECD area from 23.3% in 2000 to 12.7% in 2023. The decline stabilises after 2019 and has only been temporarily reversed in two instances; once in 2016 coinciding with the introduction of the BEPS Action 5 minimum standard and in 2022 due to the repeal of an income-based tax incentive in Italy. These trends have to be interpreted in the context of the global fall in STRs, that has led to a reduced taxation of profitable intangible investments even in the absence of income-based tax incentives (Devereux et al., 2002[7]; OECD, 2020[8]). For R&D intangibles that do not benefit from income-based tax incentives, the EATR for OECD countries has fallen from 26.6% in 2000 to 19.5% in 2023, driven by the drop in STRs. Across all 48 countries in the sample, the EATR has fallen from 26.8% in 2000 to 19.5% in 2023. In principle, lower levels of standard taxation could reduce incentives for governments to introduce income-based tax incentives, as the difference between standard and preferential taxation becomes smaller.

Despite falling EATRs under standard taxation, the extent of tax benefits provided to internally generated R&D intangibles has increased on average over time. The green bars in Figure 5.9 display the average implicit tax subsidy granted through Income-based tax incentives as measured by the difference between the average EATR for internally generated R&D intangibles under standard taxation and in the presence of income-based tax incentives. The size of the green bar continues to grow over time even following the introduction of the BEPS Action 5 minimum standard in 2015, but at a slower pace, plateauing after 2019.

Figure 5.9. EATR and implied tax subsidies for internally generated R&D intangibles, OECD countries, 2000-2023

Note: The chart reports the unweighted average EATR across all 38 OECD countries over time, including those that do not offer income-based tax incentives. It accounts for both IP regimes and dual-category regimes. Where income-based tax incentives are available at the central and subnational government level in a given year, only the central level income-based tax incentives enters the OECD average. If several income-based tax incentives are available in the same year, the most generous one is used in the computation of the OECD average. In Canada, income-based tax incentives are only available at the subnational level in the provinces of Québec and Saskatchewan. The regime in the province of Québec is modelled in this average as Québec represents a larger share of Canada’s gross domestic product (about twenty percent) relative to Saskatchewan (approximately four percent). In Switzerland, the canton of Nidwalden had an IP regime since 2011. This regime was amended in compliance with the BEPS Action 5 minimum standard in 2016. From 2020, all cantons in Switzerland have the obligation to introduce an IP regime. Estimates for the regime available in the Canton of Nidwalden are not included in this paper due to insufficient data provided to enable the modelling of the regime. Given the federal scope of the new IP regime available since 2020, the estimate for Switzerland is chosen to be that of an investment that takes place in the city of Zurich. The chart includes both IP regimes and dual-category regimes. The estimates consider an R&D investment with a gestation lag of two years after which the intangible asset starts generating profits. Baseline refers to an equivalent investment that does not benefit from income-based tax support. Preferential tax treatment is obtained by the absolute difference between the EATR including income-based support and the baseline.

Incentives at the intensive margin

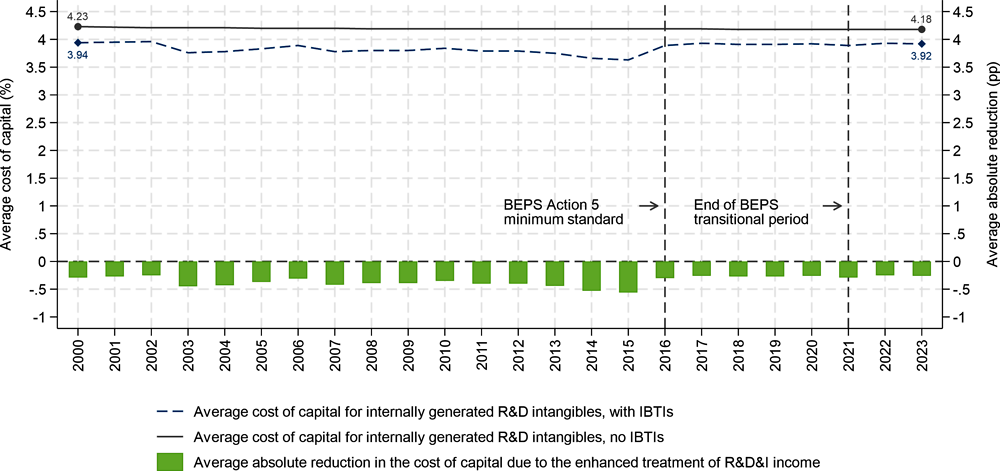

Income-based tax incentives may also contribute to lower the cost of capital, but this effect is more indirect than for other tax instruments expenditure-based tax incentives. Figure 5.10 shows that while income-based tax incentives have substantially reduced EATRs, they have had much more limited impacts on the cost of capital, which has not declined as sharply over recent years, and where qualifying investments do not enjoy a substantially more preferential treatment compared to other investments. Expenditure-based tax incentives contribute to lowering the cost of capital in a more direct fashion by affecting the cost of investment. The effect of income-based tax incentives to lowering the cost of capital is indirect as they do not affect directly the cost of investing but lower the taxation of future profits. In 2023, income-based tax incentives decreased the cost of capital in OECD countries on average by 0.3 percentage points to an average of 3.9%. The trend over time in the cost of capital for R&D intangible assets has remained relatively stable.

Figure 5.10. Cost of capital of R&D intangibles, OECD countries, 2000-2023

Estimates of the implicit tax subsidy from income-based tax incentives, marginal investments

Note: The chart reports the unweighted average cost of capital across all 38 OECD countries over time, including those that do not offer income-based tax incentives. It accounts for both IP regimes and dual-category regimes. Where income-based tax incentives are available at the central and subnational government level in a given year, only the central level income-based tax incentives enters the OECD average. If several income-based tax incentives are available in the same year, the most generous one is used in the computation of the OECD average. In Canada, income-based tax incentives are only available at the subnational level in the provinces of Québec and Saskatchewan. The regime in the province of Québec is modelled in this average as Québec represents a larger share of Canada’s gross domestic product (about twenty percent) relative to Saskatchewan (approximately four percent). In Switzerland, the canton of Nidwalden had an IP regime since 2011. This regime was amended in compliance with the BEPS Action 5 minimum standard in 2016. From 2020, all cantons in Switzerland have the obligation to introduce an IP regime. Estimates for the regime available in the Canton of Nidwalden are not included in this paper due to insufficient data provided to enable the modelling of the regime. Given the federal scope of the new IP regime available since 2020, the estimate for Switzerland is chosen to be that of an investment that takes place in the city of Zurich. The chart includes both IP regimes and dual-category regimes. The estimates consider an R&D investment with a gestation lag of two years after which the intangible asset starts generating profits. Baseline refers to an equivalent investment that does not benefit from income-based tax support. Preferential tax treatment is obtained by the absolute difference between the baseline and the cost of capital including income-based support and the baseline.

References

[2] Dernis, H. et al. (2019), “World Corporate Top R&D investors: Shaping the Future of Technologies and of AI. A joint JRC and OECD report.”, Publications Office of the European Union, https://doi.org/10.2760/16575.

[7] Devereux, M. et al. (2002), “Corporate Income Tax Reforms and International Tax Competition”, Economic Policy, Vol. 17/35, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1344772 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

[3] González Cabral, A., S. Appelt and T. Hanappi (2021), “Corporate effective tax rates for R&D: The case of expenditure-based R&D tax incentives”, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/corporate-effective-tax-rates-for-r-d_ff9a104f-en (accessed on 18 February 2023).

[6] González Cabral, A. et al. (2023), “A time series perspective on income-based tax support for R&D and innovation”, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No. 62, OECD.

[5] González Cabral, A. et al. (2023), Effective tax rates for R&D intangibles.

[4] González Cabral, A. et al. (2023), “Design features of income-based tax incentives for R&D and innovation”, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No. 60, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a5346119-en.

[8] OECD (2020), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Economic Impact Assessment: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0e3cc2d4-en.

[1] OECD (2022a), Main Science, Technology and Indicators database.

[9] OECD (2022b), R&D Tax Incentive Database, http://oe.cd/rdtax.

Note

← 1. The OECD methodology to compute effective average tax rates for R&D is described in detail in González Cabral, Appelt and Hanappi (2021[3]) and to compute the B-Index is described in OECD (2022b[9]). These indicators also feature in the OECD R&D Tax Incentive database compiled by the OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation.