Social welfare expenditure represents 20 to 30 per cent of overall government spending in many OECD countries (OECD, 2019[1]). Fraud in social benefit programmes (SBP) diverts funds away from beneficiaries and negatively affects vital services. Calculating the cost of SBP fraud is a difficult task, but country-level data suggest the amounts can be significant. In 2014, the French government detected SBP-related fraud worth an estimated EUR 425 million (French Government, 2015[2]), and in 2015, the United States Medicare Fraud Control Units recovered EUR 647 million in defrauded amounts from private providers (HHS Office of Inspector General, 2016[3]).

For the purpose of this paper, the term “social benefit programmes” refers to all government programmes that make available some kind of entitlement, whether it be a service, product or financial allowance to a beneficiary. Such programmes include tax credits and subsidies for children, unemployment benefits, subsidised or free housing, food cards (stamps), pensions, and subsidies or rebates for medical goods and services. Some SBPs involve direct transfers of money to recipients, such as pensions, unemployment benefits or disability pensions, or transfers of goods, such as housing and medical equipment. In other cases, SBPs subsidise companies and organisations that provide goods and services to beneficiaries at lower costs.

Fraud in SBPs causes more than financial losses. Fraudulent schemes can deprive people of adequate care, services and products. This can have particularly grave consequences in different sectors, such as health and social security. For instance, in Sweden, a so-called “personal assistance” scam against the Social Insurance Agency left people living with disabilities without care, while a company employed fictitious caretakers and defrauded the Swedish government by billing for work that was never performed (Radio Sweden, 2014[4]) (Allum and Gilmour, 2019[5])1. Furthermore, fraud in SBPs can compromise citizens’ trust in government. Government integrity, defined as perceptions of the extent of both high-level corruption and low-level corruption, are the first and second most important determinants of trust in government and the civil service, respectively. Integrity is a more important determinant than many other factors, such as government reliability, responsiveness, and openness (Murtin et al., 2018[6]). While corruption is not the focus of this report, these findings are instructive. Combating fraud in SBPs is likely to help governments preserve trust while providing more effective service delivery and minimising financial losses. A lack of public integrity, even if only perceived, undermines a government’s legitimacy and citizens’ trust and at worst, their trust in the system overall.

The economic downturn in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis brings this obligation to the fore, as governments bolster SBPs as part of economic stimulus packages. For example, the European Commission has proposed a EUR 750 billion recovery instrument, Next Generation EU, which will prioritise the actions needed to ensure Member States’ recovery in the aftermath of the crisis, and help workers keep their incomes and businesses to stay afloat. In Australia, the government announced a AUD 130 billion JobKeeper Payment scheme to help keep people in jobs in anticipation of the significant economic impact of the crisis. This is not the case everywhere. Many SBPs have experienced a drastic rise in caseloads because of the COVID-19 crisis, yet many are without an adequate increase in dedicated resources. The circumstances related to COVID-19 exacerbate existing risks, and create new challenges with implications for accountability and integrity measures.

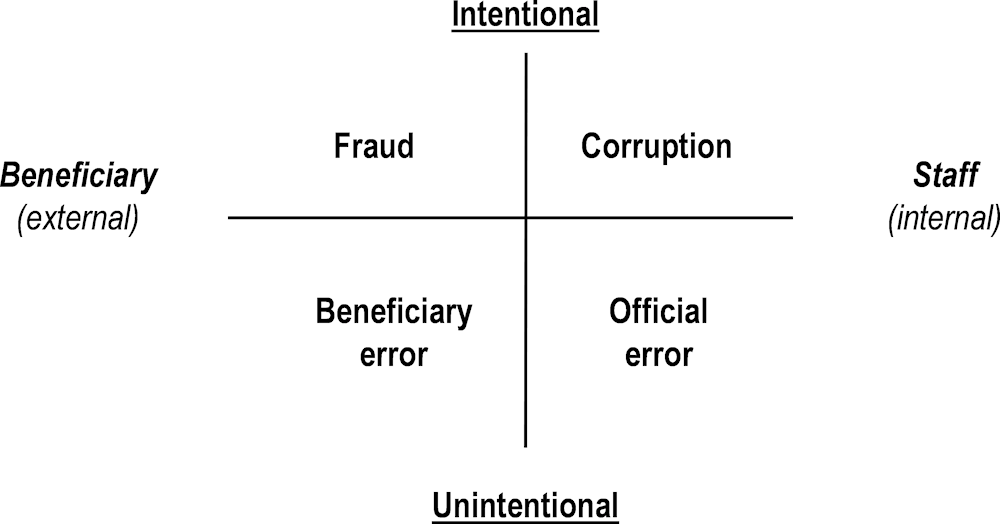

Ensuring the integrity and accountability of SBPs is critical, in times of crisis or not. The remaining sections in this chapter provide an overview of external fraud in SBPs. The first section recognises the synergies between measures to prevent fraud and those to detect, while emphasising the additional value of the former. The chapter then addresses fundamental issues of definition, including that of “external fraud” for the purpose of this report. Finally, the chapter ends with a section that notes several critical “conditions” for fraud prevention that deserve a brief mention. This chapter sets the stage for the rest of the report, which explores governments’ initiatives and tools to prevent and detect external fraud in SBPs. The report draws inspiration from the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity and related international standards, as well as insights from OECD member and partner countries. The target audience of the report is policy makers and practitioners, e.g. programme managers, auditors, risk managers and anti-fraud professionals.