Denmark’s Doing Development Differently approach led to a new strategic planning process in partner countries. Embassies now rely on country task teams – including other business units and ministries – to prepare and revise new comprehensive country strategic frameworks. Increased flexibility allows Denmark to adapt the portfolio to changing contexts. However, public documents now have less information on the programmes that Denmark is supporting.

Holistic and adaptive country strategies

Abstract

Challenge

The Development Assistance Committee (DAC) 2016 peer review of Denmark and several subsequent evaluations noted that Denmark was supporting its priority countries through a range of channels and instruments without managing to achieve synergy and coherence between all the parts.

In particular, Denmark’s published country policies and programme documents did not communicate the full picture of Denmark’s engagement in any country and were not able to adjust to rapidly changing contexts. Senior management felt that it was important to address these shortcomings while protecting their strengths. Strengths included being based on consultation and analysis and providing concrete information on Denmark’s strategic objectives, resources and bilateral engagements over a five-year period.

Approach

Denmark launched its Doing Development Differently (DDD) approach in 2019 and chose two of its priority countries – Kenya and Burkina Faso – to test a new planning process that was more holistic and adaptive. Key features of Denmark’s approach are:

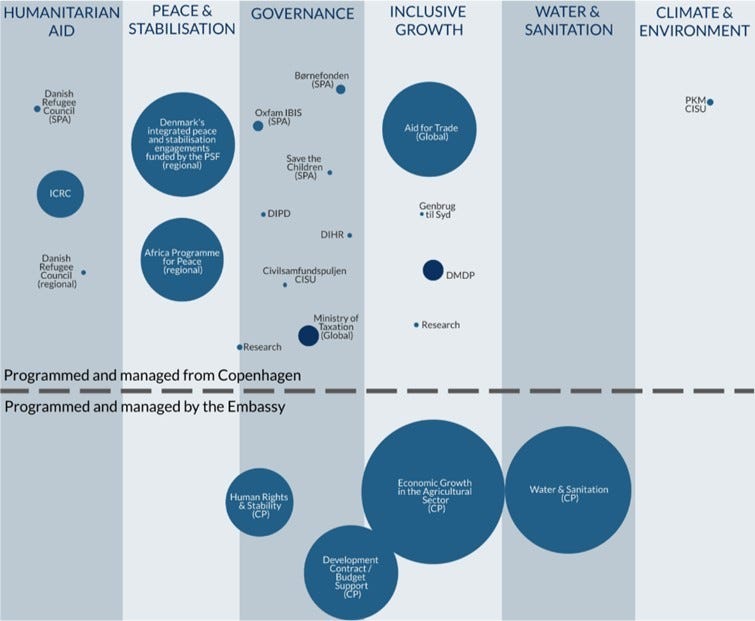

Mapping: Denmark’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) started by mapping all of its development co-operation partnerships for each country using a simple graphic, regardless of which ministry, office or business unit was managing the relationship (see Figure 1 for Burkina Faso).

Figure 1. Denmark’s range of bilateral and multilateral engagements in Burkina Faso

Note: 2018 commitments unless otherwise stated; bubble sizes are roughly proportional to programme budgets.

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark

Integrated country teams: Country task teams were formed comprising all business units, ministries and missions having interventions in the relevant country, to support the Embassy in strategic planning. The teams meet throughout the implementation period to ensure any subsequent decisions reflect Denmark’s full engagement.

Joint strategic planning: Embassies, together with the country task teams, jointly identify shared strategic objectives, building on a process of internal and external consultation with organisations in Denmark and stakeholders in relevant partner countries. Indicative budgets for each objective are committed by the Danish parliament for a five-year period. The new country strategic frameworks as well as the MFA guidelines for adaptive management are made publicly available.

High flexibility: To allow the portfolio to adapt as circumstances change, specific programmes or partnerships are no longer outlined in the country strategic framework. A double flexibility applies to each programme or partnership budget. Programmes above DKK 39 million (USD 5.86 million) are encouraged to have an adaptability reserve, which can reach 25% of the total budget, while 15% can be reallocated between projects by the head of unit. The recent revision of the Aid Management Guidelines has also made it less cumbersome to revise the expected results of a project if the strategic objectives remain unchanged. Results frameworks can now be revised by the head of unit after a consultation with partners.

Results

The new planning process is still at an early stage with pilots now completed in four countries. A monitoring framework has been established which will help Denmark to track and communicate results achieved through both the DDD approach and through individual programmes and engagements. However, two results are already apparent:

For the first time, Denmark’s strategies in Kenya and Burkina Faso now reflect the full extent of Denmark’s involvement, capturing funding and engagement through all channels, including military, diplomatic, political, trade, development and humanitarian.

An internal pre-appraisal report for Kenya noted that the DDD approach had resulted in a more focused and leaner programme of interventions.

Lessons learnt

The strategic frameworks were approved in 2020 and 2021 and so are still in the early stages of implementation. Reflections from Kenya have highlighted several ways to streamline the process and to further clarify processes for agreeing on the strategic direction and for high-level decision making.

Pre-appraisal team reports from Kenya and Burkina Faso both highlight the need to invest in monitoring, evaluation and learning, to make best use of contingency budgets and cross learning.

As some of Denmark’s partners currently lack the incentives, skills or tools to adapt, it may take some time before they are able to take full advantage of the new guidance. Denmark supports many joint programmes and in some cases other contributors have more stringent procedures.

The flexibility that comes with defining Denmark’s strategic objectives but not its specific engagements has resulted in less transparency for partner governments and for the public. This drawback is partially offset by active consultation and opportunities for public participation at the planning stage and can be further mitigated through good public information and continued dialogue with relevant authorities during the implementation phase.

Further information

Denmark – Kenya: Partnership policy 2021-2025: https://um.dk/en/danida-en/strategies%20and%20priorities/country-policies/kenya.

Denmark – Burkina Faso: Partnership policy 2021-2025: 9 (forthcoming online)

Denmark’s MFA Guidance Note on Adaptive Management https://amg.um.dk/en/tools/guidance-note-for-adaptive-management.

OECD resources

OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Denmark 2021: forthcoming on Peer reviews of DAC members - OECD.

To learn more about Denmark’s development co-operation:

OECD (2021), "Denmark", in Development Co-operation Profiles, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9b77239a-en.

Related content

-

30 September 2024

30 September 2024 -

Case study27 September 2024

Case study27 September 2024 -

27 September 2024

27 September 2024 -

16 September 2024

16 September 2024 -

11 September 2024

11 September 2024 -

10 September 2024

10 September 2024