The expectation that ocean’s economy could double in size by 2030 could pose both pressures for ocean health and human well-being as well as significant contributions to achieving the SDGs, depending on how critical trade-offs will be managed. This chapter intends to inform policy-makers on how Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (PCSD) offers a set of governance mechanisms, processes and tools that help governments in integrating sustainability in the management and use of the ocean, seas and marine resources. It provides an inventory of concrete policy instruments and tools that countries applied to strengthen coherence and integration of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development in decision making for ocean-related sectors across levels of government.

Driving Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development

3. Developing policy coherence frameworks for a sustainable use of ocean resources

Abstract

3.1. Introduction

The ocean is an essential global resource for sustainable development and human well-being. For instance, it is an important source of protein and food security, and holds an abatement potential of more than 20% of the emission reduction that is required to achieve a 1.5°C trajectory by 2050 (Ocean Panel, 2020[1]). The ocean economy is defined by the OECD as the sum of the economic activities of ocean-based industries, together with the assets, goods and services provided by marine ecosystems (OECD, 2016[2]). This definition recognises that the ocean economy encompasses ocean-based industries – such as shipping, fishing, offshore wind energy and marine biotechnology – but also the natural assets and ecosystem services that the ocean provides – fish, CO2 absorption and the like. The two pillars of the ocean economy are interdependent in that much activity associated with ocean-based industry is derived from marine ecosystems, while industrial activity often impacts marine ecosystems. Ocean-based industries are now rapidly growing. The global ocean economy represented by only ten industries is already valued at around USD1.5 trillion per year, and could double in size by 2030 (OECD, 2016[2]). According to the High-Level Ocean Panel, this could lead to dramatic increases in services from the ocean, including 12 million new jobs by 2030, the equivalent of jobs in renewable energy worldwide in 2020, 40 times more renewable energy by 2050. With these projections, a sustainable ocean economy is a means for progressing on many of the 17 SDGs of the 2030 Agenda (Griggs et al., 2017[3]).

However, increasing unsustainable economic activity in the ocean is deteriorating its health and constraining the potential of the ocean economy. The combining pressures of rising sea levels and temperatures, acidification, pollution, overfishing, and habitat loss threaten the health of the ocean, and impacts on human well-being, livelihoods, societies and the wider economy and security follow as resources are being altered.

Governments need to strengthen their capacity to balance competing interests and address fundamental trade-offs between conservation and use of ocean resources. For instance, the expected acceleration of off-shore wind farms activities could spur SDG 7’s achievement (renewable energy production) while potentially generating a negative impact on other sustainable development goals, related to ocean conservation (SDG14) and income generation (SDG 8) by limiting access to fishing areas or reducing the attractiveness of tourism and recreational facilities. In order to avoid the situation that a growing ocean economy further compromises ocean health and to avoid social tensions that could arise from mismatching ocean-related social, economic and environmental considerations, governments need support of data, management tools and governance instruments to weight groups’ interests that account for the multiple objectives of the ocean economy. As a growing number of countries select sustainable ocean economy as their priority, the PCSD principles can inspire governments in formulating ocean economy strategies and related governance arrangements that reconcile competing impacts on SDGs and socio-economic interests as well as those on neighbouring and developing countries, while reducing overlaps and fragmentation across policies and stakeholders.

Following this Introduction, Section 2 in this chapter describes the potential and expected growth of the ocean economy, pressures related to its expansion, and how balancing the two requires coherent and integrated approaches to policy-making. Section 3 showcases critical interlinkages related to the ocean economy and draws an inventory of existing tools, policy instruments and governance settings to strengthen coherence and account for those interlinkages. It closes by assessing the impact of some of those instruments and proposes some promising research and policy innovation areas as next step towards policy coherence for sustainable ocean economies.

This chapter draws on the OECD’s expertise and seeks to complement OECD work on governance issues related to the sustainable ocean economy, by exploring ways in which PCSD can be applied to the ocean economy, strengthen a whole-of government and whole-of-society approach and foster integrated approaches in support of a sustainable ocean economy, ocean health and sustainable development at large.

3.2. Navigating a sustainable balance between conservation and use of ocean resources

3.2.1. The potential of the ocean economy

The ocean economy provides indispensable resources and services for addressing the economic, social and environmental challenges outlined in global agendas such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Paris Agreement (OECD, 2021[4]) and the Convention on Biological Diversity. This includes climate change mitigation, cleaner energy, employment creation, and food security.

The size of the global ocean economy is still undervalued. A conservative OECD estimate for 2010 estimates a total Gross Value Added (GVA) of USD1.5 trillion for ten sectors as a proxy for the ocean economy, equating to 2.5% of global GVA (OECD, 2016[2]). Beyond refining estimates on ocean industries, marine ecosystem services will increasingly need to be taken into account (Jolliffe, Jolly and Stevens, 2021[5]). For instance, coral ecosystems alone contribute an estimated USD 172 billion annually to the world economy through ecosystem services such as food and raw materials, recreation and tourism (European Commission, 2022[6])) ((OECD, 2021[7])). Covering a wide range of industries, including industrial marine aquaculture, offshore oil and gas, port activities and shipbuilding and repair, the European Commission estimated the ocean economy to represent 1.5% of the EU’s GVA in 2019 and employing 4.5 million people (European Commission, 2022[8]). Attempts to assess the contribution of ocean-based industries to national economy as a share of GDP vary considerably, ranging from less than 1% to 26% (OECD, 2016[2]). In some parts of the world, the ocean economy, as a share of national GDP, is presumably considerably higher than in high-income countries. Asia alone is home to nearly 80% of the 37.9 million people around the world working with fisheries, followed by Africa with 13% and the Americas with just over 5% (FAO, 2022[9]).

The ocean economy is projected to grow. The compound annual global value added (GVA) growth rate in ocean industries are projected at 3.5% between 2010 and 2030, reaching a GVA of USD3 trillion in 2030 (OECD, 2016[2]). At the European Union level, the latest estimates showed a compound annual growth rate in GVA of 1.64% between 2009 and 2019 (European Commission, 2022[6]).

Table 3.1. Projections of selected ocean industries’ growth rates 2010-30 (before COVID-19 crisis)

|

Sector |

Compound annual growth rate in global value added |

|

Maritime and coastal tourism |

3.5% |

|

Ports |

4.6% |

|

Marine aquaculture |

5.7% |

|

Fish processing |

6.3% |

|

Offshore wind |

24.5% |

|

Average ocean economy |

3.5% |

Source adapted from (OECD, 2016[2]), The Ocean Economy in 2030, https://10.1787/9789264251724-en

A growing ocean economy with potential for job creation, clean energy, and provision of services and resources for economic growth and human health, brings hopes for a “blue acceleration”. It also brings growing and competing interests for ocean food, material, and space and with it the risk of further compromising ocean health (Jouffray et al., 2020[10]) .

3.2.2. Pressures on Ocean Health

A healthy ocean is a prerequisite for both nature and people to see benefits from growth in ocean-based sectors and industries. For a sustainable ocean economy, it is also a boundary condition. Multiple pressures already put strain on many ocean species and habitats and illustrate the impacts that must be taken into consideration to sustainably leverage the ocean economy’s potential around the world.

The critical support functions of the ocean upon which human health and well-being and our climate system depend, are being affected by the combining pressure of acidification, rising sea levels and temperatures due to climate change; pollution; and overfishing, among others (IPBES Secretariat, 2019[11])).

Climate change-induced sea-level rise is a major risk for coastal areas, directly impacting the natural and built environment with critical repercussions on coastal ecosystems. Key risks related to sea level rise include erosion, flooding and salinisation which are expected to increase in intensity and frequency. The latest IPCC estimates suggest that the global mean sea level (GMSL) will rise between 0.43 m and 0.84m by 2100, relative to 1986-2005, with important regional variations. Sea level rise, in combination with anthropogenic ocean warming and acidification, brings a major strain on ecosystems resulting in habitat contraction, loss of functionality and biodiversity, and lateral and inland migration. However, ocean warming and acidification are thought to have a greater impact on fisheries and aquaculture than sea-level rise. The current rate of ocean acidification is unprecedented within the last 65 million years.

Pollution from agricultural run-off and fertilisers, plastic, shipping, sewage, offshore oil and gas, chemical pollution and other sources is threatening species and marine habitats and makes its way into the food chain. In coastal areas, eutrophication caused by nutrient pollution has increased since 2016 and resulted in 700“dead zones” worldwide in 2019. In 2021, a study estimated that more than 17 million metric tons of plastic entered the world’s ocean, making up 85 per cent of marine litter. With an annual inflow of 4 million metric tons of mismanaged waste plastics from rivers and coastlines leaking into the ocean, projections estimate that this figure could reach 145 million metric tons by 2060. Because of large leakage during monsoon season, emerging economies in Asia are expected to be the primary source.

While fish consumption has increased between 1990 and 2018 wild catch fisheries production has been stable in this period and the increase in consumption of fish met entirely by aquaculture (FAO, 2022[9])Illegal fishing and harmful fishing practices add pressure to biodiversity and marine ecosystems (OECD, 2022[12]) (IPBES Secretariat, 2019[11]). In 2019, the fraction of fish stocks sustainably fished decreased to 64.6%, that is 1.2 percent lower than in 2017 (FAO, 2022[9]), largely because of ineffective fisheries management and illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. Rapid urbanisation of coastal zones further aggravates pollution, habitat loss and resource pressure.

3.2.3. A Sustainable Ocean economy as a Policy and Governance Challenge

Facing interconnected and cascading pressures, ocean governance and the growth of the ocean economy, is an obvious case of the urgency to develop more integrated governance approaches. Policy coherence can help developing policies that respond to the web of interlinkages among multiple ocean-related sustainable goals, and that simultaneously use ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and job creation, while allowing for preservation of the health of ocean ecosystems.

Policy coherence and whole-of-government approaches at global, national and subnational levels will be critical to address numerous risks and uncertainties related to oceans. As the ocean is large and far-reaching, three-dimensional and fluid, these characteristics makes the ocean economy – and its positive and negative, spatial or temporal, interlinkages - often difficult and expensive to monitor and overview, and therefore less known than land-based ecosystems (OECD, 2016[2]). For instance, as species moving between coastal and offshore areas, can pose challenges for data collection and fisheries management. While legal frameworks such as UNCLOS are clear with regards to legal responsibilities, enforcement is not sufficient and some areas lack collective management of ocean resources, with negative impacts on economic activities beyond national jurisdiction. These ocean’s specificities could entail increased competition between states for access to resources in the seas (OECD, 2016[2]).

Global frameworks, conventions and partnerships1 become important for ensuring that economic activities in the oceans respect environmental integrity (OECD, 2021[4]). An important step in this direction is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as well as the High Seas treaty under UNCLOS signed in March 2023 (see Box 3.1)

Despite these progresses, fragmentation in international law risks creating conflicting and incompatible rules, principles, institutional practices and policies that work at across purposes, resulting into weak compliance, and lack of enforcement. Gaps in the ocean governance framework also translate in a plethora of different agencies looking after different activities and policy frameworks thus undermining holistic visions.

The SDG 14 as well as the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) emphasises the importance of further strengthening integrated programming and synergies vis-à-vis other multilateral agreements. For instance, the GBF recalls the importance of considering these commitments in the wider context of sustainable development rather than the achievement of the targets per se, in particular linking SDG 14 on life below water and 15 on life on land. Yet, most initiatives for achieving SDG14 have focused on the sustainability of ocean ecosystem and management, rather than the economic relevance of various ocean-based sectors and their interactions with land-based sectors.

Box 3.1. Tools to foster greater international co-operation in maritime governance, agreements, conventions, science and technology

Some experiences in international regulations and governance of the sea aim at encouraging a holistic vision across the different international agencies, policy frameworks and standards that apply to the ocean.

Many international initiatives are ongoing to address ocean governance challenges and support countries in their governance efforts. For example, the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean economy (the Ocean Panel) was established in 2018, assembling Heads of States of sixteen countries which share the aim to manage sustainably 100% of their ocean area under national jurisdiction by 2025. Among its activities to help in ocean and coastal states to sustainably manage national waters by 2030, an initial guide was developed and launched in December 2021 (Ocean Panel Secretariat, 2021).

An example of regional ocean governance is the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) that aimed at supporting the establishment of Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) in the region by developing the framework for integrated marine planning and management for the islands in the Eastern Caribbean from 2020 to 2035. Another example of an inter-governmental policy platform for sustainable management of the sea is Helsinki Commission’s (HELCOM) operating in the Baltic Sea region. The member states of HELCOM have developed a Baltic Sea Action Plan (BSAP) (first edition in 2007, updated in 2021) with measures to address environmental issues. This was sent out in a consultation process to regional stakeholders such as NGOs, local and regional authorities, research institutes, before adopted.

International statistical and methodological database help countries advancing in their integrated ocean management as well as undertaking international comparative analysis and sharing practices on the role of government policies and planning tools. For instance, advanced international platforms exist for the exchange of knowledge in the area of MSP. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) at UNESCO published an updated extensive guide with practical examples to develop maritime spatial plans (UNESCO, 2021[13]). UNESCO-IOC also hosts a database (UNESCO-IOC, N/A[14])) with literature and practical examples and country progress reports and forum for connecting MSP initiatives. EU also provides a database available on “the EU MSP Platform” (Commission, N/A[15])) where MSP literature and country practice examples can be found. Sharing approaches on Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), can also enhance transnational cooperation when MPAs out limit Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and enter Marine Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ) as illustrated in the case of Western Indian Ocean Marine Protected Areas Management Network (WIOMPAN) (see Annex A).

The recently agreed High Seas Treaty within UNCLOS, (Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction, BBNJ) also aims to fill gaps in ocean governance. 193 countries agreed that establishing MPAs to reach the “30x30 target” is key to safeguard and protect ocean biodiversity, which the Ocean Economy in turn relies on. While these measures are needed, particularly in small island nations and small island developing states (SIDS), as ocean pressures and competition for resources increase, this approach to safeguarding ocean health holds potential trade-offs with social and economic goals at the local level. The High Seas Treaty is expected to be the main mechanism for reaching the new target under the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD’s) COP15, setting aside 30% of the world’s marine areas by 2030, the 30x30 target. This target was developed in response to failing to reach both the quantitative and qualitative target of 10% effective and representative protection outlined in SDG 14.5 and Aichi Target 11 ( (IUCN, 2022[16]). The new recently agreed global treaty for the high seas under UNCLOS, (United Nations, 2023[17]) addresses; 1) marine genetic resources, including questions on benefit-sharing, 2) area-based management tools, including marine protected areas, 3) environmental impact assessments (EIA) and 4) capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology (Tiller et al., 2023[18]). Reaching the new target will require effective, representative and inclusive measures for marine conservation in the global common ocean (CBD, 2022[19]). The international legally binding agreement will not be undermining already existing relevant bodies, legal instruments and frameworks in the ocean sphere, however it could highlight the importance of safeguarding biodiversity within them.

Despite increasing local progress in lowering the multiple pressures on ocean health, concerted efforts to protect and adopt solutions for sustainable ocean management must be intensified. For example, no parts of the world are close to, almost or entirely meeting SDG 14, as indicated by progress to increase the coverage of protected areas in relation to marine key biodiversity areas. (United Nations, 2022[20]). Globally, countries are very far from, and progress is deteriorating in, meeting the target to increase the proportion of fish stock within biologically sustainable levels (United Nations, 2022[20]). This lack of progress has implications for the health of the ocean, but also affects other SDGs as ocean sectors interlink with other policy areas (e.g. fisheries contribution to food and nutrition security). Given the nature of marine ecosystems, species and processes not being confined to nations' boundaries, progress cannot be achieved within one jurisdiction, thus creating a need for co-operation and for a global governance framework for the sustainable use of ocean resources.

Despite the evidence about critical interlinkages between ocean economy and the SDGs (see Box 3.2. Critical interlinkages between the ocean economy and sustainable development goals) and recognition to the need to balance competing interests and needs related to the use of ocean resources, governments continuously struggle with adopting more integrated and coherent approaches to decision- and policymaking. There are multiple reasons for this, including:

Fragmentation of policy frameworks, given that ocean economy covers several sectors, including maritime transport, tourism, fisheries, aquaculture, offshore oil and gas and renewable energy. In many cases, these sectors are managed by different agencies and have different policy frameworks, with limited coordination. For example, agencies responsible for fisheries may have different objectives than those responsible for developing offshore energy projects, which could result in difficulties to develop integrated policies, capable of balancing different interests and promoting sustainable use of ocean resources.

Conflicting interests of different stakeholders, such as fisheries and tourism which may compete for the same coastal area. PCSD would call for balancing these competing interests while preserving the sustainability of ocean resources. For example, tourism and fishing may use the same coastal areas, and as such would need approaches that balance these interests while minimising negative spillovers among them and negative impacts on sustainable development.

Limited data and difficulties to monitor and measure the ocean, given its size, which can hinder decision-makers’ capacities to make informed decisions. For example, gaps in data on fish populations could prevent developing effective fisheries management policies. Data are crucial also for stakeholders consultation and to clearly inform how different groups are impacted by transition measures and ways of mitigating the costs. Relevant constituencies need to be informed about the trade-offs and be involved in the decisions.

Gaps in governance and enforcement as well as the lack of international cooperation and coordination, which can lead to unsustainable practices, overexploitation of ocean resources and challenges for managing transboundary issues, such as migratory fish stocks or marine pollution.

Unstable and overlapping international frameworks might overburden administrations in charge of implementing them and leave little space for assessing the trade-offs related to new measures and coordinate with other services on the better ways to integrate them into national legislations

To help address these policy challenges, countries make efforts to develop policy instruments, tools and mechanisms that allow balancing competing uses of the sea. Section 3.3 presents a number of these country practices and links them to PCSD principles.

3.3. Applying PCSD principles for addressing critical interlinkages across a sustainable ocean economy

This section aims to illustrate how policy-making processes aligned to PCSD principles can promote a sustainable ocean economy by better balancing competing interests in the use of ocean resources. The section uses the SDG framework to place the ocean economy in the context of sustainable development. It starts by describing critical linkages across ocean-related targets with other SDGs, both in terms of synergies and trade-offs and existing efforts and database to measure them. Next, it provides an inventory of relevant institutional mechanisms, governance tools and policy instruments that support coherence efforts to address competing interests related to ocean economy, as well as concrete country examples where they have been applied. Finally, it concludes by compiling existing evidence of the effectiveness of the tools and further instruments to be explored, including in innovation and technology for sustainable fishing, aquaculture, and renewable energy.

As recalled in Chapter 1 (see section 1.3) and in previous OECD recommendations to foster a sustainable ocean economy (OECD, 2017[21]) PCSD can better prepare governments to deal with potential policy conflicts, cross-border policy impact and long-term implications of ocean economy. The tools and mechanisms inventoried below contribute to these PCSD objectives by:

Improving co-ordination and decreasing fragmentation in government’s operations at all levels, including the international level, with a view to foster whole-of-government and stakeholder engagement and collaboration in order to identify shared objectives, concerns, and priorities. Fostering cooperation around these objectives, by identifying and implementing efficiency/sustainability gains can reduce fragmentation and overlaps in ocean-related activities.

Increasing the capacity of governments to identify and address trade-offs and synergies in view of accelerating progress on the SDGs. Several of the identified practices aim at building the capacity of government agencies to collect and use data and monitoring systems on ocean resources, ecosystems, and human activities. In particular capacity for ocean industry foresight, including the assessment of future changes in ocean-based industries are being developed. This is in view of identifying and addressing interlinkages across ocean-related goals and targets, as well as long-term priorities to be maintained over short-termism. This data is used for integrated ocean management which is often done involving a plethora of non-state and local actors.

Promoting international cooperation and coordination and supporting the development of effective ocean legal frameworks. This is crucial because global and transboundary ocean policies cannot be implemented without the appropriate governance and adequate capacities and resources. Some of the practices inventoried involve for example: establishing international platforms for the exchange of knowledge, experience and best practice, undertaking international data collection of marine and maritime activities as well as regional efforts to develop marine spatial plans. More comparative analyses of ocean policies and reviews of the role of government or on technological innovations could be beneficial.

Pairing institution-building with trust-building. Some of the highlighted mechanisms applied high standards of consultation, transparency and oversight by the public or parliaments to increase the support to transition towards more sustainable use of ocean resources.

The ocean-specific governance arrangements identified below illustrate how PCSD objectives can be achieved in the ocean sector in order to ensure better sustainability results across the SDGs.

3.3.1. Critical interlinkages in governing a sustainable Ocean economy

The SDG framework is useful for placing the ocean economy with its sectors (tourism, transport, aquaculture, fishery, renewable energy) in the wider context of sustainable development; and for identifying key synergies and trade-offs across social, environmental and economic goals with policy objectives for ocean sectors (Le Blanc D., 2017[22]). Meanwhile, the ocean economy is part of a shift towards a more planned economy, using an ecosystem-based approach, across ocean-based sectors to balance competing uses (as well as balance growth, development and protection of ecosystems), ownership and stronger governance mechanisms and systems (Baker, Constant and Nicol, 2023[23]).

Growth in sectors of the ocean economy interlink (see Figure 3.1) with multiple SDGs, including poverty eradication (SDG1), food security (SDG2), livelihoods, jobs and economic growth (SDG8), equity (SDG10) and climate change (SDG13) ( (International Council for Science (ICSU), 2017[24]).

Figure 3.1. Key interactions SDG14 (life below water) with other sustainable development goals

Notes: Target-level interactions between SDGs are evaluated, based on ICSU expert judgement and the scientific literature, on a 7-point scale. Positive interactions score from +1 to +3 (enabling, reinforcing, indivisible), 0 score signifies that there is no significant interaction, negative interactions score from -1 to -3 (constraining, counteracting, cancelling)

Source: (International Council for Science, n.d.[25]) International Council for Science, A guide to SDG interactions, https://council.science/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/SDGs-interactions-14-life-below-water.pdf

Ocean economy strategies and SDG action vary with each context, and therefore the implications of their interlinkages; effective governance responses are context-specific. Analysis for guiding policy will have to consider interlinkages in light of geography, direction and timing of impacts, uncertainties with regards to future stocks, pressures and impacts, tipping points, irreversibility and more. Such analysis must take place on a case-by-case basis, but can draw on common analytical tools and frameworks as discussed in this section.

Some interlinkages yet emerge as more generic, or globally applicable, and can effectively illustrate the need for considering the synergies and trade-offs posed by a growing ocean economy with the approaches and tools at hand. Such critical interlinkages are illustrated in Box 3.2, as they emerge considering sectors and activities that are expected to grow as part of an expanding ocean economy, the objectives set out in SDG 14 and other global frameworks for protecting ocean health (in particular the Global Biodiversity Framework, GBF2) and their known interlinkages with other social and economic SDGs.

Box 3.2. Critical interlinkages between the ocean economy and sustainable development goals

With more economic activity in the ocean for projected growth across ocean economy sectors, (see Table 3.1), the competition for marine resources and space is increasing and pressures on ocean health are accumulating. Economic growth (SDG8) can follow from development of coastal tourism, affordable housing (11.1) and fishing industries, but also negative environmental impact such as marine pollution (SDG 14.1) and CO2 emissions (SDG 13), and if poverty alleviation (SDG1) does not follow and benefits are fairly distributed (SDG 10), social impacts will also be negative.

A healthy ocean contributes to resilience and adaptive capacity of both the natural and human systems to climate change (SDG 13). With increasing CO2 concentrations (SDG 13.2.2 total greenhouse gas emission per year) in the atmosphere acidification increases and this limits the capacity for the ocean to take up CO2 and mitigate climate change. It also negatively affects marine organisms and ocean services, and higher temperatures cause sea level rises that affect communities in SIDS the hardest. The Ocean economy relies on a healthy ocean, and is both adding pressures and holds potential to mitigate them.

Offshore wind energy is the ocean economy sector projected to grow the most. Increasing the share of renewable energy (SDG 7) helps to reduce CO2 emissions and ocean acidification (SDG 14.3) and creates job opportunities (SDG8), at the same time infrastructure for renewable energy in coastal and marine areas adds to the spatial competition with protected areas, fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism. Wind energy platforms can have immediate negative impacts both locally on seabed ecology and regionally for shipping and navigation, for example. However, in a longer time perspective, positive effects have also been seen at specific locations, in terms of providing e.g. artificial reefs, spawning grounds and act as hinder for destructive trawling fisheries. Both negative and potential positive impacts are site specific, and ocean management instruments like Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) provide tools for addressing conflicting stakeholder needs and policy fragmentation (energy, coastal tourism etc), including the need for right spatial scale and details.

Area-based measures like ocean zoning and expansion of marine protected areas (MPAs) is promoted by the GBF, SDG14 and as key measure of Marine Spatial Planning (MSP). They are being introduced to protect natural capital such as coral reefs or marine biodiversity. Area-based measures have direct impact on the ability to utilise ocean resources, and can constrain access to resources needed in the short-term for poverty alleviation (SDG 1) and economic growth (SDG 8). For example, while restricting artisanal fishers from high biodiversity zones can contribute to biodiversity conservation and relevant SDG targets (14.2, 14.4, and 14.5), and in the longer-term enhance economic benefits through the recovery of fish stocks (SDG 14.7), stricter protection and regulation of marine resources will affect their current livelihoods (1.1, 1.2, 8.1).

The risk that negative externalities from measures introduced to protect the ocean will fall upon most vulnerable actors, must be counteracted by robust governance structures that support transparent, participatory, and equitable decision-making processes (can be enabled by e.g. Marine Spatial Planning -MSP, and Source 2 Sea -S2S). Using a holistic and ecosystem-based governance and management approach has shown that by integrating ecotourism, conservation and education in alignment with SDG targets (8.9, 14.7, 14.5, 14.4, 14.2 and 4.7) with e.g. establishing MPAs together with stakeholders, can improve income diversification opportunities. The recovery of fish stocks within MPAs can also result in spillover to nearby fishing grounds, to the benefit of local fishers.

Fish processing is expected to see the second largest growth across Ocean economy sectors, and with most fish stocks under pressure, regulation to achieve sustainable fisheries is key, not least for local economies in small island developing states in Oceania and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) where sustainable fisheries play an important role, accounting for about 1.5% and 0.9% percent of GDP respectively (OECD, 2016[2]). Healthy fish stocks are key to the long-term prosperity of fishers’ communities (SDG 1, SDG 8) and seafood also makes a vital source of protein and provides food security for billions of people (SDG 2).

Third largest growth in Ocean economy sectors is aquaculture. Subsistence and small-scale aquaculture contribute directly to the alleviation of poverty (SDG1) and achievement of food security (SDG2). In addition, small-scale and large-scale commercial aquaculture can enhance the production for domestic and export markets and generate employment opportunities in the production, processing and marketing sectors (SDG8). Large-scale aquaculture facilities need to be managed in a sustainable way otherwise there is risk of increasing nutrient pollution (SDG 14.1).

These critical interlinkages across the Ocean economy and SDGs exemplify the need for balancing multiple social, economic and environmental objectives and keeping in mind the impact they can have, both spatially (local and regional) and temporally (short- and long-term). A sustainable Ocean economy hinges on managing these synergies and trade-offs, and ocean health hinges on a sustainable Ocean economy and mitigation of other pressures like climate change. This requires breaking out of sectoral silos.

Source: Authors’ elaboration

3.3.2. Towards an inventory of mechanisms, tools and policy instruments that support coherence for ensuring a sustainable and healthy ocean economy

This section aims to inventory governance practices, policy frameworks, instruments and tools that support the core principles of the OECD Recommendation on PCSD as they help addressing challenges related to achieving coherence in using ocean resources sustainably and delivering on SDGs. It begins by highlighting strategic policy frameworks and integrated management plans, then follows a section on multi-level and national institutional mechanisms that leverage policy coherence for the ocean sector. From this enabling environment, the inventory then focuses on mechanisms that help linking sustainability data to policy impacts in order to design more integrated policies and to identify compensatory schemes. It follows by an overview of ocean-related policy instruments (i.e. compensation policies, tax instruments) and spatial planning tools that can support policy coherence in the use of ocean resources. Finally, tools to foster collaboration with stakeholders and for measuring policy impacts are equally analysed.

Strategic policy frameworks and integrated management plans

Recent years have seen a significant increase in the number of countries and regions, including developing countries (OECD, 2020[26]) putting in place overreaching policy frameworks for sustainable ocean management (or Sustainable Ocean Plans). These documents provide an essential framework for policy coherence as they map-out long-term ocean sustainability objectives and translate them in short and mid-terms targets and actions. Such strategic frameworks are in line with PCSD principles as they allow reducing administrative overlaps and fragmentation and deal with potential policy conflicts. In addition, such strategic frameworks are needed as reference points for evaluating how other relevant sectoral initiatives and regulations align with plans for the Ocean and indicate procedures to harmonise existing uses and laws (such as UNCLOS) (OECD, 2016[2]). These strategies often point to the importance of MSP for the development of a sustainable Ocean economy.

One example of a strategic policy framework prioritising ocean objectives is the recently adopted National Ocean Strategy (NOS) 2021-2030 in Portugal. This public policy instrument sets the framework for sustainable development of the economic sectors related to the ocean. The Strategy points to the importance of MSP in the development of a sustainable blue economy and the need to ensure compatibility between different existing and potential future activities and for creating the necessary conditions for sustainable growth within the maritime economy, alongside environmental and social development. The strategy encompasses roles and mandates of existing entities, but its co-ordination mechanism might benefit from involving more operational levels from the administrations implementing ocean-related activities to ensure that they are aware of the objectives foreseen in the NOS and they actively contribute to it.

Institutional and multi-level mechanisms

Although data is still lacking in terms of coherent whole-of-government approaches and results in establishing coordination mechanisms for designing and implementing ocean strategies, responsibility for the ocean economy is often scattered across a country’s administration (Table 3.2) resulting in a variety of sectoral policies in place to manage different uses of the ocean (such as shipping, shipbuilding, fishing, oil and gas development). This might create obstacles to cost-effective and sustainable management of ocean resources due to potential weak co-ordination and limited use of data and methodologies across ministries and different levels of government (i.e. central, provincial, municipal). Countries are often at different stages of ocean governance construction and effectiveness levels, and sometimes this varies within a country when sub-national governments have built their own governance and policy approaches.

Table 3.2. Ocean-related competencies across Indonesia’s ministries

|

Ministry/Agency |

Competence |

|---|---|

|

Indonesia Statistics |

|

|

Ministry of Defense |

|

|

Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources |

|

|

Ministry of Environment and Forestry |

|

|

Ministry of Finance |

|

|

Ministry of Foreign Affairs |

|

|

Ministry of Home Affairs |

|

Source: (OECD, 2021[27]), Sustainable Ocean Economy Country Diagnostic of Indonesia, [DCD(2021)5]

There are promising advances (see Annex A for more examples). Cabo Verde for instance established a Ministry for the Maritime Economy and the ministry’s portfolio was also closely tied to tourism and transport because the Ministry for the Maritime Economy being headed by the Ministry for Tourism and Transportation at the same time (OECD, 2022[28]). This centralised institutional arrangement translated into grand strategies for the development of the ocean economy including a recent initiative to realise marine spatial planning in Cabo Verde. Similarly, in Antigua and Barbuda, the Ministry of Social Transformation and the Blue Economy was officially established in 2020 in recognition of the increased importance of the marine space to the nation’s future prosperity.

In Portugal, under the Ministry of the sea (created in 1980), then merged with the Ministry of Economy, the Directorate General of Natural Resources, Safety and Maritime Services (DGRM) assumed since 2012 the responsibilities of different entities (port and maritime transports institute, directorate general of fisheries and aquaculture) as well as for a third area relating to the environment and sustainability of the sea. These mandates gave the DGRM a wide range of competences from fisheries policy, the maritime-port sector including vessels’ certification, maritime safety and security, managing maritime spatial planning that previously scattered various directorates and public institutes. Currently the Directorate is investigating, with OECD support, how its capacities and internal processes, can be improved in order to better align its services to long-term objectives related to decarbonisation, digitalisation and sustainable ocean economy. The Directorate-General for Maritime Policy (DGMP) was established the same year in order to, amongst other things, develop, evaluate, update and coordinate the implementation of the National Ocean Strategy and the marine spatial planning strategy (European Commission, 2023[29]) and ensuring effective implementation of the overall national strategies through everyday administrative processes.

Furthermore, coherent ocean governance can be challenged also by fragmentation across levels of government. For instance, within their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ), countries sometimes have different authorities for different sub-areas of the EEZ. This creates a need for co-operation, shared objectives and information among different levels of government authorities. For example, in Viet Nam, coastal waters are under the responsibility of regional and district authorities. The Offshore waters, in the EEZ, are under the responsibility of the ministry of the sea. The problem is that regional and district authorities do not necessarily have the capacity to manage the EEZ sustainably and often statistics are not shared between the Ministry and territorial authorities.

Tools for identifying ocean economy interlinkages

The first step for enhancing policy coherence is to gather data for mapping out critical interlinkages among sustainability objectives, highlighting their potential synergies and trade-offs. Data availability on SDGs targets/indicators and data from different disciplines, such as environmental and climate change data, data on the scale and performance of ocean-based industries and their distributional impact, is key to explore for example, how climate change will affect coastal activities, or how policies in different sectors influence each other (cross-impact analysis). Foresight and mission-oriented use of data has grown since the introduction of the indivisible and integrated 2030 Agenda and is being applied to specific sectors or policy objectives, such as the ocean.

Data on policy interlinkages related to the ocean are gathered in international platforms. Such platforms also include inventories of country practices and methodologies to use such data. One example is SDG Synergies (www.sdgsynergies.org), a tool which uses cross-impact analysis with network analysis to analyse how progress on each of the SDGs, in a specific context, impacts progress in all the other goals. Other tools help to navigate SDG interlinkages by providing science-based assessments, including for example the iSDG model and SDG Interlinkages Analysis & Visualisation Tool. Another tool to map the interlinkages among the impact of land-based and ocean activities on the ecosystem thus identifying the actions needed is Source-to-Sea (S2S) (see also Annex 1). This approach creates baselines that can be monitored and actions (in e.g. governance, operations, practices and finance) that can be evaluated (Mathews, 2019).

Data on interlinkages could contribute to more evidence-based and sustainable decisions by the executive and legislative authorities. This data should be taken into account by line ministries at the moment of ex-ante policy or legislation impact assessment and then during ex-post evaluation.

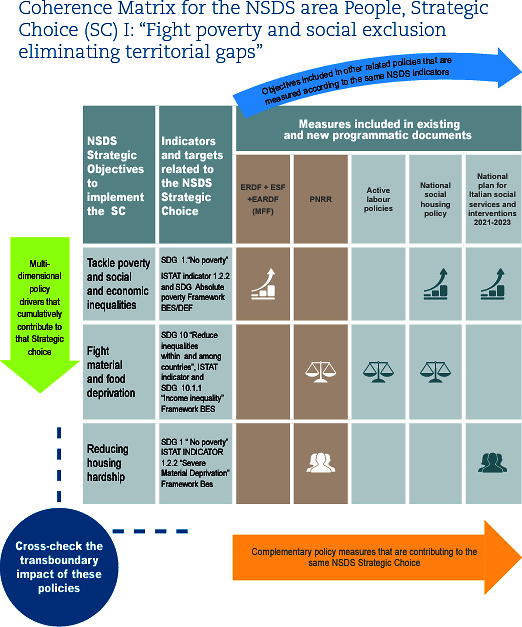

Tools for linking sustainability targets to policy objectives

Coherence matrixes, as a policy coherence tool, can prove effective in early identifying potential policy trade-offs, reducing fragmentation and dealing with long-term sustainability issues. This hands-on tool can help connecting silos between and within government departments and agencies. Italian Government adopted such tools, inspired by sub-national governments who have been forerunners in designing and implementing such practices. A coherence matrix, see Figure 3.2 as example, extracted from the Italy’s National Action Plan for Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (OECD, 2022[30]), allows linking a draft policy with SDGs indicators as well as with policy objectives, targets and indicators relevant for other sectoral policies contributing to a same long-term sustainable priority. For instance, a coherence matrix pinpoints to which extend a policy contributing to goal 14 – e.g. sustainable aquaculture and innovative solutions on mariculture- overlaps or creates trade-offs with policies already contributing to that same goal, creates synergies trade-offs with other policies contributing to other interlinked goals (i.e. energy, marine conservation, etc). Once identified how policies in different sectors influence each-others and which significant contributions or competitive effects could provoke in achieving SDGs in developing countries (transboundary effects), policymakers (drafters in line ministries or oversight bodies of draft policies and legislation) should ensure alignment. Such tool not only helps more join-up approaches with other strategies contributing on the same SDGs, but also in considering compensation measures to strengthen enabling factors and compensating disenabling consequence of the new policy towards meeting the sustainability objectives.

Figure 3.2. Coherence Matrix for the Strategic Choice 1 “Fight Poverty and social exclusion eliminating territorial gaps” of the Sustainable Development Strategy of the Italian Government

Source: (OECD, 2022[30]), Italy’s national action plan for Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development, https://doi.org/10.1787/54226722-en.

South Africa used data from the online mapping system, which identifies biodiversity priority areas and actions at various spatial scales. These priorities framed the formulation of the 2005 National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) laying-out a mission-oriented approach with six strategic objectives, clear targets and indicators as well as a list of lead and implementing agencies for every action. This is an example of how a Coherence Matrix could have helped applying available biodiversity data, during the formulation of a strategic document across policy sectors and to integrate biodiversity concerns into decision making across sectors such as agriculture, forestry and fisheries (OECD, 2018[31]).

Strategic policy frameworks and integrated management plans

Recent years have seen a significant increase in the number of countries and regions, including developing countries (OECD, 2020[26]) putting in place overreaching policy frameworks for sustainable ocean management (or Sustainable Ocean Plans). These documents provide an essential framework for policy coherence as they map-out long-term ocean sustainability objectives and translate them in short and mid-terms targets and actions. Such strategic frameworks are in line with PCSD principles as they allow reducing administrative overlaps and fragmentation and deal with potential policy conflicts. In addition, such strategic frameworks are needed as reference points for evaluating how other relevant sectoral initiatives and regulations align with plans for the Ocean and indicate procedures to harmonise existing uses and laws (such as UNCLOS) (OECD, 2016[2]). These strategies often point to the importance of MSP for the development of a sustainable Ocean economy.

One example of a strategic policy framework prioritising ocean objectives is the recently adopted National Ocean Strategy (NOS) 2021-2030 in Portugal. This public policy instrument sets the framework for sustainable development of the economic sectors related to the ocean. The Strategy points to the importance of MSP in the development of a sustainable blue economy and the need to ensure compatibility between different existing and potential future activities and for creating the necessary conditions for sustainable growth within the maritime economy, alongside environmental and social development. The strategy encompasses roles and mandates of existing entities, but its co-ordination mechanism might benefit from involving more operational levels from the administrations implementing ocean-related activities to ensure that they are aware of the objectives foreseen in the NOS and they actively contribute to it.

Spatial planning and policy instruments that can support policy coherence in the use of ocean resources

Policy coherence in the use of ocean resources can be enhanced by measuring the interlinkages listed in paragraph 3.3.1, linking them to policies’ impacts, identified through coherence matrixes, and including priorities in strategic policy frameworks. These frameworks then need to be translated into actions through plans, regulations and policy instruments that are integrating PCSD principles. Most coastal nations of the world already use policy instruments and planning tools for balancing competing uses of the sea. These tools can contribute to PCSD objectives when they represent steps towards solving the problem of fragmented policy-making related to the ocean, avoiding conflicts of interests, dealing with ocean-related cross-border issues and with long-term tipping points. In order to increase their effective contribution to the PCSD objectives, these tools should systematically help in taking into account data that measures SDGs impact and interlinkages; using data for mapping sectoral policies that are contributing to the same SDGs commitment and suggesting compensations or synergies across policies that have negative or positive impacts. For this systemic contribution to PCSD principles some changes might be needed in the way these instruments are applied (i.e. institutional mechanisms, processes, revisions, etc), at different steps of the policy cycle.

For instance, Marine Spatial Planning (MSP), can contribute to several PCSD principles in particular long-term vision, policy integration and multi-stakeholder participation, as well as policy impact measurement, addressing the issue of fragmentation of several sectoral policies involved in the ocean economy. Government and agencies at different levels can use this process in decision-making to better allocate temporal and spatial space to economic activities and environmental protection. It allows countries to move away from isolated, short-term sectoral management to plan for integrated policies in the ocean and provides a base for regulation in several marine sectors (i.e. licenses, private spatial permits, bans, etc). The development of the marine spatial plans has accelerated (OECD, 2017[32]; OECD, 2019[33]). Between 2005 and late 2021 more than seventy-five countries (Ehler, 2021[34]) are either implementing or approving marine spatial plans. MSPs look at the co-use, coexistence, or co-location of activities and resources of both ecosystem and human activities (Barquet and Green, 2022[35]). MSP is a process rather than end-product, balancing different stakeholders conflicting interests, such as coastal tourism and fisheries, through stakeholder involvement throughout the planning process. MSP is often used in connection to countries developing their ocean economy strategies. There are different tools developed to practically support the MSP process, often GIS based, these tools help showcase the data for different human activities and ecosystem in an area, which enables monitoring and evaluation. One of the obstacles is the lack of MSP legislation and long-term funding constraints that the MSPs’ planning processes require, as well as the funding and regulation required for the enforcement of the resulting plans .

The Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are often part of MSPs and constitute a regulatory instrument setting area-based conservation measures, which have shown to significantly increase carbon sequestration thus contributing to climate change mitigation. Data on sustainability interlinkages and coherence matrixes can ensure this conservation measures are established in the most balanced way. For instance, data can help establishing flexible MPAs that can be opened up for sustainable fisheries without undermining migrating species’ safeguard. These tools also allow a better understanding of MPAs’ impacts across different interest groups and the possible transitional measures needed to address any most adversely impacted, through effective multi-stakeholders dialogue, as exemplified in the examples of Tanzania and New Zealand (see Annex A) and in the next paragraph.

Another opportunity to support policy coherence for a balanced use of ocean resources is to incorporate data on sustainability interlinkages when designing compensation or synergies measures across policies that have been identified as having negative or positive impacts on a same long term objective. For instance, compensation schemes funded through taxes, fees, or other means, are designed as mechanisms to ensure no one is left behind. They may offer financial support to negatively impacted stakeholders. One example is fisheries buyback programmes that compensate fishing communities for the loss of fishing rights or marine conservation trust funds, such as the Tanzania’s marine legacy (see Annex 1) which provide financial assistance for alternative livelihoods, or social safety nets including programs like food assistance, healthcare, and social security. Alternatives to financial support or safety nets for assisting fishers in transitioning to new livelihoods schemes could be capacity building to develop in-demand skills in the ocean economy and access new opportunities. Measures to encourage environmentally friendly behaviours, such as taxes on plastic materials implemented by Indonesia (see Annex 1), should use data on sustainability interlinkages to always consider the impact of less polluting alternatives on all groups. Another policy instrument that could benefit from incorporating data on interlinkages is investing in environmental restoration. In this case sustainability data and policy coherence tools can be used to measure upfront the potential outcomes of restoring degraded ecosystems in terms of new economic opportunities for affected stakeholders, such as to boost tourism, recreation, and fisheries

Collaboration, Stakeholder engagement and Participation

In the process of transiting towards a sustainable ocean economy some stakeholders may experience negative impacts or losses due to policy decisions. Tools and instruments that seek to design ocean priorities and reconcile trade-offs, should ensure the interests of various stakeholders are considered, through a transparent and inclusive process, allowing them to provide input and feedback on policy options. Participatory approaches to ocean management presented below and in Annex 1 contribute to several PCSD objectives by:

Integrating policy options into a consistent SDGs framework for discussing their economic, social, and environmental impacts;

Identifying trade-offs, including by assessing the potential impacts of policy options on different priorities and interests of stakeholders;

Integrating mitigation schemes to minimise negative policy impacts; and

Including stakeholders in development and reporting of Monitoring and Evaluating policies’ frameworks over time.

Governments face a range of challenges related to effective stakeholder engagement in ocean governance, including the diversity of stakeholder groups, such as industry (e.g., fishing, aquaculture, maritime transportation, oil and gas, biotechnology and tourism) civil society organisations, academia, and local communities, with varied resources and capacities to engage that can create a power imbalance. Knowledge gaps on the state of ocean and ecosystems, can further limit opportunities to have meaningful dialogue and reach shared objectives, and there is sometimes limited trust between stakeholders, particularly between industry and civil society organisations. New inclusive and participatory approaches to stakeholder engagement that advance in a green and just transition in the ocean sector are needed. Such approaches for building trust across the diversity of stakeholder groups and their perspectives, could be strengthened by incorporating IT, artificial intelligence technology and interactive social media platforms.

The New Zealand’s Fiordland’s Management Act 2005 was pushed forward by local stakeholders and exemplifies how MPAs can be an effective tool to effectively manage varying interests, when a bottom-up approach is adopted. In 1995, the area was facing escalating pressures on the ocean health which led local communities to take action and drive conservation efforts that resulted in the establishment of Fiordland Marine Area. The area is now managed by the Fiordland Marine Guardians, a statutory advisory body comprising commercial and recreational fishers, environmentalists, charter boat and tourism operators, scientists, and tangata whenua (Ngāi Tahu). At the heart of their conservation strategy is the consultation of the public as well as local and central government management agencies. By formulating a common vision to protect the area, the Marine Guardians paved the way for successful management of the MPA. This approach to manage the pressures on ocean health from human activities is in line with the PCSD recommendation around co-creating through stakeholder engagement can lead to sustainable management of ocean resources.

Chumbe Island Coral Park (CHICOP) in Zanzibar provides an example of involvement of stakeholders in environmental regulations’ enforcement, in this case the management of a marine protected area. In 1994, CHICOP focused their efforts on awareness campaigns and local stakeholder involvement to protect the area from overfishing and coral reef deterioration. Local fishermen were hired by the park to patrol the reefs and enforce the newly established fishing ban. Their unconventional approach has gained global recognition, where the development of ecotourism to support conservation, research and environmental education is seen as a model of financially and ecologically sustainable park management (OECD, 2020[36]).

Assessing policy impacts across multiple sectors

According to PCSD recommendation assessing the contribution and importance of different economic sectors and potential trade-offs encourages an integrated approach to the policy cycle by sharing data and knowledge across sectors. Analysis of the cross-sectoral impacts of proposed policy is necessary to guide decision-makers prior to designing and adopting tools and instruments, for instance during regulative impact assessments. The various SDG interlinkages tools, including coherence matrices help to map interlinkages, but impact assessments need to follow in order to identifying losers and winners and possible compensation measures.

Sustainability ex ante assessments could, for instance, screen economic instruments (taxes on plastic materials, conservation fee on visitors, pay coastal communities for conservation activities, etc) which provide incentives for sustainable production and consumption, and they are also able to generate government revenue to support the conservation and sustainable use of the ocean (OECD, 2017[32]). The beneficiary pays’ approach introduced by Belize and Tanzania (see Annex A) as well as the Indonesia’s plastic tax (see Annex A), constitute examples of new economic instruments for which the sustainability ex ante assessment could have helped in gathering information on the cost and benefits of introducing them across all relevant SDGs. While ex ante assessments are not always available, The World Bank developed a Plastic Policy Simulator which could have been used in Indonesia.

Ocean Accounting (OA) is a statistical framework which was included in the MSP and MPA process as a tool to monitor ecosystem and biodiversity conservation. Five countries (Gacutan, 2022[37]) are aiming to implement both MSP and OA in conjunction (Australia, Thailand, South Africa, Portugal and Canada). The aim is to create indicators such as economic production (ocean GDP), flows of benefits (ecosystem services) and how human activities affects these and ocean natural assets. It can be used to perform cost benefit analysis for both the environment and society, analysing impacts from activities and policies (to increase positive impact and anticipate potential harmful impacts) thus inform decision-making. Thailand used the OA in its MSP for evaluating the trade-offs between tourism (which is a big part of the country’s GDP) and resource use and impacts e.g. water, energy, waste in relation to local population to better allocate areas for tourism development. (Gacutan, 2022[37]) .

The Swedish Agency for water and marine management (SwAM) has developed the tool Symphony, for MSP, which quantifies and assesses different environmental pressures on the ecosystems by human activities. It also offers scenario projection and data visualisation and can therefore support in decision making showing projected environmental impacts (also cumulative impacts from different sectors or activities in certain geographical areas) depending on the planned alternatives. For example, it is used in Sweden in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea when planning for a transition towards a fossil-free society with the allocation of offshore wind and wave energy taking into account environmental factors and other sectors and activities (Barquet et al., Forthcoming[38]). This planning tool was developed and introduced in Sweden but are now being applied in ten East African countries in collaboration with the Nairobi convention and SwAM (Hammar, 2020[39]).

Data limitations is another major constraint for strengthening the evidence-base, and several countries are expanding their capacity to collect data including through an ocean satellite accounting approach linked to their national accounts (Jolliffe, Jolly and Stevens, 2021[5]).

However, improved statistical data related to the ocean economy could spur more integrated and long-term policy formulation only if they integrate ocean sectors and link to other sectoral monitoring frameworks. The coherence matrices introduced at the beginning of this Chapter could constitute a stepping-stone to identify key indicators that are more relevant to long-term sustainable priorities identified in national, or international, ocean-related strategies. The second step would be to ensure interoperability of a set of key indicators across sectoral monitoring frameworks that can support decision-making and to monitoring of ocean-related policies.

3.3.3. Towards greater effectiveness of the use of PCSD mechanisms for sustainable ocean economy

At this point in time, with the SDGs reaching midpoint this year and with the recent High Seas Treaty providing an encouraging example of international cooperation, there is opportunity for countries to revisit strategies and plans for the ocean and leveraging on existing knowledge and experience of effective governance practice. PCSD provides a framework for leveraging public governance mechanisms, institutional settings, capabilities and tools to ensure that different policies and levels of government strive towards the same sustainable development, biodiversity, climate and ocean economy objectives.. This subsection showcases some of the results achieved by governance and innovation mechanisms and policies at different levels of government (global, national and local), and offers concrete ideas on where further research and policy innovation is needed. Further research should focus on implementation; ways of promoting uptake and build capacity to turn principles to practice.

The capacity of the PCSD instruments to balance multiple interests and bring about a sustainable ocean economy, depends on how they are designed, their enforceability and the evidence-base they rest on. For example, the effectiveness of strategic policy frameworks (i.e. National Ocean Strategies, legislative frameworks etc.) and tools such as MSP in terms of sustainability results and integrated policy making depend on whether enforcement of plans are grounded in legislation and the document’s status (National legislation, Government Decision, Political statement), the entity in charge of the implementation of the strategy (e.g. central unit, ministry, inter-ministerial committee, etc.), its time horizon (2030, 2050), whether other sectoral ministries are bound to implement the strategy or plans, and whether there is budget, action plan and time-bound milestones connected to its implementation. Other questions to consider include how progress on the strategy are measured; whether SDGs are included among the progress/performance indicators monitored; whether some of the progress/performance indicators of the strategy are linked to key performance indicators (KPIs) of the relevant ministries; and how the strategy makes references to broader national sustainability strategies and link with other sectoral strategies.

One example of analysis of the effectiveness of a MSP legislation, the 2009 UK Marine and Coastal Act highlights that implementation proved challenging due to the: 1) lack of specificity in policies; 2) organisational disconnection between policymakers and licensing officers; 3) lack of political input 4) mismatch between the decision-making culture of licensing officers and marine policies. Moreover, independent examination of the plans has not been undertaken, something which would have been required for terrestrial plans of similar scope. As a result, this analysis calls for stronger policies in marine plans and a strengthening of the administrative structure surrounding plan policy implementation. This act offered a starting point to adopt an integrated approach to plan-making and licensing across the four UK administrations, while allowing for differentiated approaches to implementation (Slater and Claydon, 2020[40]).

Science-informed governance and technological innovation are important for aligning with principles and practices enshrined in the 2019 OECD Council Recommendation on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (OECD, 2019[41])) and enable a smarter governance. Smart governance is enabled with new technologies like Artificial Intelligence (AI), digital twin of the ocean and real time in-situ sensors which creates opportunities for more monitoring and increased knowledge on human impacts on ecosystems. For instance, in the European Green Deal (European Commission, n.d.[42]), the Destination Earth Initiative is the next step to develop a Digital Twin of the Ocean. The Digital Twin Ocean's ambition is to make ocean knowledge readily available to citizens, entrepreneurs, scientists and policymakers to support transition towards sustainable oceans. The use of open data also creates transparency and legitimacy to the data.

Another clear entry point to more sustainable planning for ocean is multifunctional planning. Through co-use, coexistence, or co-location of activities and resources, multifunctional platforms have an important role to play in terms of reducing inefficiencies in the maritime industry. Underutilised marine equipment and infrastructure is a source of significant costs and emissions which can be avoided by increasing multifunctionality through sharing, repurposing and re-designing. Multifunctional offshore platforms could also be used to integrate tourism activities with climate adaptation and resilience measure, contributing to job creation, industry integration, education and acceptance. Currently, technology readiness levels for multifunctional platforms are low which calls for more pilot demonstrations. For example, a multi-use wind and wave offshore platform designed for hosting an automated aquaculture system was tested in the Mediterranean for a period of six-months in 2022.

The effectiveness of new participatory governance mechanisms for the ocean also deserves further analysis. For instance, LivingLabs, whether virtual or in person, provide a space for co-creation which could prove instrumental in supporting multifunctional planning approaches. The C2B2 programme for sustainable blue economy in Sweden, which brings together 38 maritime actors from industry, academia, public sector, and civil society, uses the LivingLabs co-creation methodology. Operationalised through three demonstration cases, this approach aims to trigger transformative changes towards participatory ocean governance.

Disruptions brought by the COVID pandemic to the tourism sector have given rise to new and more sustainably oriented tourism models that can play a critical role in overall ocean management. For instance, in response to international travel restrictions, “staycations” have directed tourists towards less crowded areas and natural experiences. This new interest in local natural hotspots has brought municipalities to develop tourism activities at the intersection between leisure, climate adaptation and resilience interventions. In this regard, nature-based coastal solutions can be used to optimise co-benefits by increasing ecological value while providing recreational activities such as hiking and photography. The pandemic also accelerated the digital transformation of the sector, changing the way people travel and experience places. In Sweden, sea-based applications are used to provide sustainability recommendations to travellers. Finally, virtual reality tourism is on the rise providing yet another alternative to discovering the world more sustainably. In response to these new trends, the European Parliament adopted in 2021 a resolution establishing an EU strategy for sustainable tourism adapted to the Digital Agenda, the European Green Deal and the UN Sustainable Development Goals with emphasis on ecosystem conservation and multi-stakeholder dialogue to ensure the sustainable development of coastal and marine tourism.

3.4. Policy insights

This chapter has aimed to show that governance tools and instruments aligned with PCSD principles can help to reconcile competing impacts of the ocean economy on SDGs and on neighbouring and developing countries and to reduce overlaps and fragmentation across policies and stakeholders' interests. The following insights emerge in order to use more proactively existent instruments and governance mechanisms and to increase their effective contribution to the PCSD objectives for sustainable ocean governance across the policy cycle:

Reduce fragmentation across global ocean governance and regulative frameworks. PCSD approach can enable a holistic vision across the different international ocean agreements, agencies and policy frameworks that pushes for achieving ocean conservation targets in a wider sustainable development context. Such global vision could foster national and sub-national practices that identify and face interlinkages among the ocean-related sustainable development goals

Gather data at international, national and sub-national level for mapping critical interlinkages among ocean-related sustainability objectives. Increase data availability on SDGs targets/indicators and data from different disciplines, such as environmental and climate change data, data on the scale and performance of ocean-based industries and their distributional impact, etc. PCSD practices and tools, such as coherence matrix, can help using this data for mapping interlinkages and how policies' impacts, in different ocean-related sectors, influence each other. Equally they can help in considering compensation measures when designing new policies that compensate for the disenabling impacts of the new policy towards meeting the sustainability objectives. This information should inform the formulation of ocean strategic frameworks and spatial planning tools (i.e. MPA, MSP, etc).

Reduce fragmentation of ocean economy across countries' administrations. Countries established ocean coordination practices for aligning the variety of sectoral policies in place (such as shipping, shipbuilding, fishing, oil and gas development, aquaculture, tourism) into a strategic ocean framework. PCSD tools can help effective political and coordination mechanisms in operationalising such frameworks by translating them into mid-term plans and budgets, identifying entities responsible for time-bounded milestones and developing monitoring and evaluation mechanisms.

Streamline sustainable development concerns in ocean policies by ensuring that the way ocean-related policy instruments (table 3.2) are designed and applied (i.e. institutional mechanisms, processes, revisions, etc) enables: taking into account data that measures impacts on the SDGs and their interlinkages; using data for mapping sectoral policies that are contributing to the same SDGs commitment and suggesting compensations or synergies across policies that have negative or positive impacts on this commitment.

Develop new approaches to stakeholder engagement that advance in a green and just transition in the ocean economy and can be enhanced by knowledge on SDGs interlinkages and how policies influence different sectors and their effects on different stakeholder groups. Such approaches for building trust across the diversity of stakeholder groups could benefit from incorporating information technology, including artificial intelligence technology and interactive social media platforms.

Enhance skills, expertise and knowledge of policymakers, regulators and stakeholders involved in ocean governance toward better measuring and integrating new economic opportunities and balancing their impact on boosting tourism, recreation, energy and fisheries against their impacts on the ecosystem.

Develop robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to assess the effectiveness of policies and initiatives related to sustainable ocean economy, including by agreeing on a set of indicators that are more relevant to long-term sustainable priorities identified in sectoral national, or international, ocean-related strategies, beyond indicators related to SDG 14.

References

[23] Baker, S., N. Constant and P. Nicol (2023), “Oceans justice: Trade-offs between Sustainable Development Goals in the Seychelles”, Marine Policy, Vol. 147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105357.

[35] Barquet, K. and J. Green (2022), Towards Multifunctionality: adaptation beyond the nature-society dichotomy, Stockholm Environment Institute.

[38] Barquet, K. et al. (Forthcoming), Towards a sustainable blue economy in Sweden, Stockholm Environment Institute.

[19] CBD (2022), COP15: Nations Adopt Four Goals, 23 Targets for 2030 In Landmark UN Biodiversity Agreement [WWW Document]. Conv. Biol. Divers., https://www.cbd.int/article/cop15-cbd-press-release-final-19dec2022 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

[15] Commission, E. (N/A), The EU MSP Platform, https://maritime-spatial-planning.ec.europa.eu/msp-practice/database?field_term_country_tid%5B0%5D=39&keys=&sort_bef_combine=title%20ASC&page=2.

[34] Ehler, C. (2021), “Two decades of progress in Marine Spatial Planning”, Marine Policy, Vol. 132/104134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104134.

[29] European Commission (2023), DGPM - Portuguese Directorate-General for Maritime Policy, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/maritimeforum/en/node/4892.

[8] European Commission (2022), The EU Blue Economy Report 2022, Publications Office of the European Union, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2771/793264.

[42] European Commission (n.d.), A European Green Deal, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.

[6] European Commission, D. (2022), The EU blue economy report 2022, Publications Office of the European Union, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2771/793264.

[9] FAO (2022), The state of fisheries and aquaculture: towards blue transformation, https://www.fao.org/state-of-fisheries-aquaculture.

[37] Gacutan, J. (2022), “The emerging intersection between marine spatial planning and ocean accounting: A global review and case studies”, Marine Policy, Vol. 140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105055.

[3] Griggs, D. et al. (2017), A Guide to SDG Interactions: from Science to Implementation, ICSU.

[39] Hammar, L. (2020), “Cumulative impact assessment for ecosystem-based marine spatial planning”, Science of The Total Environment, Vol. 734/139024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139024.

[25] International Council for Science (n.d.), A guide to SDG interactions, https://council.science/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/SDGs-interactions-14-life-below-water.pdf.

[24] International Council for Science (ICSU) (2017), A Guide to SDG Interactions: From Science to Implementation, ICSU, Paris, https://doi.org/10.24948/2017.01.