This chapter provides contextual information to inform the interpretation of the IELS results in the United States. It highlights demographic information about children and their families in the United States; the early learning policies of the federal and state governments; and an overview of the early childhood education and care services available, including discussion of their quality and impact. The chapter concludes with an overview of major issues and debates relating to the early learning sector in the United States and a statement about what IELS can contribute to a growing body of international evidence on early learning.

Early Learning and Child Well-being in the United States

Chapter 2. The context of early learning in the United States

Abstract

In the United States, as in many countries worldwide, there has been an increasing recognition in recent decades of the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping outcomes throughout life. Of the approximately 74 million children currently living in the United States, around 24 million are aged five and under, the time when learning and development happen at a greater rate than at any other time of life. Generally, the cognitive skills that a child displays at the age of five are associated with a range of later outcomes, including educational attainment, socio-economic status and general well-being. Early social and emotional competencies predict later emotional health, physical well-being and life satisfaction. In addition to their associations with later outcomes, children’s cognitive and social-emotional skills are important for their current well-being and the success with which they navigate relationships and their environments.

This chapter provides contextual information to inform the interpretation of the International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study (IELS) results for five-year-olds in the United States. Specifically, it highlights demographic information about children and their families in the United States; the early learning policies of the federal and state governments; and an overview of the early childhood and care services available, including levels of participation in these services and discussion of their quality and impact. The chapter concludes with an overview of major issues and debates relating to the early learning sector in the United States and a statement about what IELS can contribute to a growing body of international evidence on early learning.

Profile of children and families in the United States

Birth rates in the United States are in decline. In 2017, the number of births was the lowest recorded in more than 30 years and the general fertility rate was at a record low of 1 765.5 births per 1 000 women (Martin et al., 2018[1]). Birth rates vary across racial and ethnic groups in the United States, and this, combined with increased inward migration, means that the population has been characterised by increasing racial and ethnic diversity and multiculturalism in recent years (Devine, 2017[2]). In 2017, 51% of children in the United States were White, 25% were Hispanic (of any race), 14% were Black, 5% Asian, 4% were of two or more races, 0.8% were American Indian or Alaska Native and 0.2% were Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2018[3]). The proportion of children who were White (non-Hispanic) fell from 62% in the year 2000 to 51% in 2017 (Musu-Gillette et al., 2017[4]) and it is projected that less than half of the US population will be White (non-Hispanic) by 2044 (Colby and Ortman, 2015[5]).

Currently, one-quarter (25%) of children living in the United States live with at least one parent who was born outside the country (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2018[3]) and close to one-quarter (23%) of children speak a language other than English at home. Although there is no official language in the United States, English is the primary language spoken in the country and is the language of instruction in most schools. In 2016, close to one in ten students in the kindergarten to twelfth grade (K-12) public school system (9.6% or 4.9 million students) were classified as English language learners (ELLs), up from 8.1% (or 3.8 million students) in the year 2000. Students identified as ELLs typically receive specialised or modified instruction at school. Generally, children in the lower grades of the public school system are more likely to be ELL than those in the upper grades. In 2016, for example, 16% of children in kindergarten were ELLs, compared to 9% of students in sixth grade, 7% in eighth grade and 4% in twelfth grade. This is partly explained by students who started school with limited English proficiency going on to develop their English proficiency as they progress through to the later grades (NCES, 2019[6]). The most commonly spoken language among ELL students in 2016 was Spanish (approximately 3.8 million students), followed by Arabic (129 386 students), Chinese (104 147 students) and Vietnamese (78 732 students) (NCES, 2019[6]). ELL children in English-speaking early childhood education and care (ECEC) and kindergarten settings bring unique experiences and learning strengths to these settings, but also have different needs to their non-ELL peers (Baker and Páez, 2018[7]) and may face challenges to their readiness to attend school (Gottfried, 2014[8]). States vary considerably in their share of ELLs, ranging from less than 1% of students in West Virginia in 2016 to 20% of students in California. Traditionally, ELL children were concentrated in a small number of states (such as California and Florida), but changes in immigration patterns have meant that some of the states experiencing the greatest increases in the share of ELL students have been in the South and the Midwest. The learning needs of ELL children can therefore no longer be viewed as a regional issue, but one that is of widespread relevance across the United States (Gottfried, 2014[8]).

In 2015, household net adjusted income1 in the United States was higher than that in any other OECD country, at USD 44 049, and considerably higher than the OECD average of USD 30 563. The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) was USD 20.494 trillion in 2018, making it the world’s leading economy in GDP terms. The distribution of wealth in the United States, however, is highly unequal2 (OECD, 2017[9]). The 20% of the population with the highest incomes earn approximately 8.5 times more than those in the bottom 20% (OECD, 2015[10]). In 2017, 17.5% of children in the United States lived in families experiencing poverty (defined as an annual income below USD 25 283 for a family of four), meaning children are the poorest age group in the United States (Fontenot, Semega and Kollar, 2018[11]). With 20% of children under six living in poverty, the youngest children are the poorest (Children’s Defense Fund, 2018[12]). Child poverty rates vary considerably by race and ethnicity, with White children less likely to live in poverty. In 2017, 12% of White children up to the age of five were from families below the poverty line, compared to 36% of American Indian/Native Alaskan children of that age, 34% of Black children, 26% of Hispanic children, and 16% of Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander children (Children’s Defense Fund, 2018[12]). The child poverty rate in the United States is higher than the OECD average and higher than in most other OECD countries. In 2016, children in the United States were approximately twice as likely to live in relative poverty (21%) as children in Estonia (10%); the corresponding child poverty rate in the United Kingdom was 12% (OECD, 2018[13]).

In 2018, 69% of children in the United States lived with two parents, 27% lived with one parent, and 4% lived with someone other than a parent, whether relatives or non-relatives (United States Census Bureau, 2018[14]). Of those living with one parent, 83.5% lived with their mother and 16.5% with their father (United States Census Bureau, 2018[14]). These percentages have changed little in the last 20 years, although the proportion of children living with two unmarried parents has increased somewhat, from one in five children in 1997 to one in four in 2017 (Pew Research Center, 2018[15]). The share of single parents who are fathers has also increased (United States Census Bureau, 2018[14]). Family structure varies somewhat by racial and ethnic background in the United States, with Black children more likely to live with their mothers only (48% in 2017) than Hispanic children (25%) or White children (18%) (United States Census Bureau, 2018[14]).

Record numbers of children in the United States now live in multigenerational households. In 2016, 20% of the population, or 64 million people, lived in households with more than two generations. Multigenerational family living is growing among nearly all racial groups and Hispanics (Pew Research Center, 2018[16]). Such changes in household structure and living arrangements may have implications for the types of care and supervision children receive in early childhood.

In 2017, the labour-force participation rate of all women with children under the age of 18 in the United States was 71%, up from 47% in 1975 but unchanged since 2004; the equivalent rate for fathers in 2017 was 93% (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019[17]). Women with younger children are less likely to be part of the workforce: just over three-quarters (76%) of mothers with children aged 6-17 years old were in employment, compared to 65% of women with children aged five or younger. Labour-market participation varies by race and ethnic origin. Black mothers of young children have significantly higher participation rates than White, Hispanic, Asian American/Pacific Islander and American Indian mothers of young children (Center for American Progress, 2018[18]). Black mothers’ labour-market participation rates do not increase as quickly as their children age as they do among mothers from other racial and ethnic groups, rather they are high soon after their children are born and remain high as their children age. Black mothers’ consistently high labour-force participation rate is likely a result of necessity rather than choice, resulting from lower incomes and a greater likelihood of being the primary earners in their households (Center for American Progress, 2018[18]).

In 2017, 18% of all parents did not work outside of the home, with mothers more likely to be stay-at-home parents (29%) than fathers (7%) (Pew Research Center, 2018[19]). In a nationally representative survey conducted in 2017, 63% of fathers indicated that they did not believe that they spent enough time with their children, primarily citing work obligations as the reason for this; mothers were much more likely to indicate that they spent the optimal amount of time with their children (Pew Research Center, 2018[20]).

The majority of adults in the United States (60%) have completed high school (OECD, 2019[21]). Approximately one-third (32%) of adults have completed at least a bachelor’s degree. Levels of educational attainment are higher among parents than among adults with no children (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Educational attainment of adults aged 16 to 65 by whether or not they have children, United States

1. Less than high school completion.

2. High school diploma or equivalent.

3. Vocational or technical institute (one-year certificate programme) or associate’s degree

4. Undergraduate degree or higher.

Source: OECD (2015[22]), PIAAC: Public Data and Analysis, www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis/.

In the 2015/16 school year, 13% of all students in public schools received special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). More students received these services for specific learning disabilities than for any other disability type (34% of those receiving support, or 4.5% of the total student population). The IDEA defines a specific learning disability as, “a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations.” [Sec. 300.8 (c) (10)]. One in five students who were receiving support under the IDEA did so as a result of a speech or language impairment, while a further 14% received services for another health impairment (such as having limited strength, alertness or vitality due to a chronic or acute health condition). Other disabilities leading to services for students under IDEA included autism (9%), developmental delay (6%), intellectual disability (6%), emotional disturbance (5%), multiple disabilities (2%), hearing impairment (1%) and orthopaedic impairment (1%) (NCES, 2018[23]). There is some variation in the proportion of students receiving services under IDEA by race or ethnicity. In 2015-16, for example, 17% of American Indian/Alaska Native students, 16% of Black students, 14% of White students, 13% of students of two or more races, 12% of Hispanic students, 12% of Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander students and 7% of Asian students were in receipt of special education services (NCES, 2018[23]).

Strategic intent for early learning

Federal policy

According to the United States Department of Education (n.d.[24]), the federal goals for early learning are to:

…improve the health, social-emotional, and cognitive outcomes for all children from birth through 3rd grade, so that all children, particularly those with high needs, are on track for graduating from high school college- and career-ready. To enhance the quality of programs and services and improve outcomes for children from birth through 3rd grade, including children with disabilities and those who are English Learners, the Department will promote initiatives that increase access to high-quality programs, improve the early learning workforce, build the capacity of states and programs to develop and implement comprehensive early learning assessment systems, and ensure program effectiveness and accountability.

This statement of strategic intent refers to supporting the health, social-emotional and cognitive development of all children from birth. The federal government primarily supports this initiative indirectly, by providing grants to states to support young children and their families.

On average, women in OECD countries are entitled to 18 weeks of paid maternity leave to support families in the lead up to and after the birth of a child, and almost all OECD countries offer at least 3 months of paid maternity leave (OECD, 2017[25]). The United States is unique among OECD countries in having no statutory entitlement to paid maternity, paternity or parental leave (OECD, 2017[25]). In 1993, the US Congress passed the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) with the intention of balancing “the demands of the workplace with the needs of families” and acknowledging that “it is important for the development of children and the family unit that fathers and mothers be able to participate in early childrearing”. Under the FMLA, employees of public agencies, public or private elementary or high schools and private enterprises with more than 50 employees are entitled to 12 weeks job-protected unpaid leave for specified family or medical reasons, including the birth of a child. Approximately 40% of the workforce is not covered by the FMLA (Klerman, Daley and Pozniak, 2012[26]). Seven states have enacted their own family and medical leave acts with lower thresholds for employer coverage (for example, in Vermont, private companies with 10 or more employees must provide job-protected unpaid parental leave). California, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Washington, Massachusetts and the District of Columbia have laws that guarantee paid family and medical leave.3 In 2015, just 12% of workers in the private sector in the United States were entitled to paid maternity leave (United States Department of Labor, 2015[27]). In a survey conducted by the Department of Labor in 2012 of approximately 3 000 employees who had taken leave under the FMLA in the previous year, close to 1 in 4 (23%) women who took this leave for the birth of a child returned to work within two weeks of having the baby, with 12% returning within one week (Klerman, Daley and Pozniak, 2012[26]).

In addition to their implications for women’s physical and psychological well-being, maternity and parental leave policies have important implications for children’s development. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that, where possible, children be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life to achieve optimal growth, health and development (World Health Organization, 2011[28]). Data from 2015 indicated that fewer than half of infants (47%) in the United States were exclusively breastfed for three months, with just one in four (25%) exclusively breastfed for the recommended six months (CDC, 2018[29]). Comparative data from 2005 showed that rates of excusive breastfeeding at six months were higher in countries with longer periods of maternity or parental leave, such as the Nordic countries. The United States had some of the lowest rates of exclusive breastfeeding at three, four and six months of all OECD countries (OECD, 2009[30]).

The US Department of Education’s statement of strategic intent for early learning presented above also contains the goal of improving children’s outcomes through building capacity among the states to provide effective early learning programmes and assessment systems. Indeed, there is no real national ECEC policy in the United States, as individual states have responsibility for and control over their education and care systems, with responsibility often further devolved to local authorities. For kindergarten to twelfth grade (K-12) education in the United States, the main federal law is the Every Student Succeeds Act, which replaced the No Child Left Behind Act when it was introduced in 2015. There is no equivalent law for pre-kindergarten (pre-k) education and care.

State policies

The vast majority of states lack the level of robust infrastructure for early childhood education and care that all states have for K-12 education (Atchison and Diffey, 2018[31]). As Table 2.2 shows, governance, finance, professional certification and regulation are less coherent and formalised in the ECEC sector than in K-12 education. In terms of governance, multiple state agencies administer early childhood education services and programmes. Local authorities can also administer these programmes and services directly, as can private providers. States rarely have formal governance structures that direct who makes high-level decisions about eligibility, regulation and accountability for public early childhood services across different state departments. This fragmentation may be at least partly attributable to how ECEC has developed in the United States over recent decades. Welfare reforms in the 1990s, particularly under the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, dramatically reduced the number of individuals in receipt of welfare assistance, many of whom then moved into employment, which was predominantly low-income and potentially precarious (Child Trends, 2002[32]). Increased labour market participation, disproportionately among single mothers, led to increased demand for childcare (Child Trends, 2002[32]). The main purpose of many of the programmes and services which met this demand was the provision care and supervision for young children while their parents worked, and these day care services fell and continue to fall under the remit of departments of health and human services. In more recent years, educators, policy makers and parents have increasingly recognised the importance of high-quality early learning experiences for child development and later outcomes. The potential education function of early childhood services began to grow in importance relative to care and supervision, and departments of education at both state and federal levels increased their involvement in and support for ECEC services. Consequently, multiple entities are often contributing simultaneously to an early learning vision, “with little attention paid to potential duplication or collaboration”, leading to gaps in provision and uneven quality (Atchison and Diffey, 2018, p. 1[31]). The complexity of the administration, financing and oversight of early childhood programmes creates policy challenges, as “convoluted administrative structures create natural limits to addressing policy issues in an efficient manner” (Atchison and Diffey, 2018, p. 1[31]).

Table 2.2. Comparison of characteristics of the early childhood and K-12 education systems in the United States

|

|

ECEC |

K-12 |

|---|---|---|

|

Governance |

Nothing formalised in most states |

State boards of education and local school boards |

|

Finance |

Multiple, chaotic funding |

Guaranteed tax base |

|

Professional certification |

None universally required |

Required to teach |

|

Regulation |

Minimum health and safety standards are state required; all else is voluntary |

Required accreditation |

Source: Atchison and Diffey (2018[31]), Governance in Early Childhood Education, www.ecs.org/governance-in-early-childhood-education/.

Where states do express goals for early learning, they tend to be in terms of the skills that children should have developed by the time they start school. Thirteen states4 and the District of Columbia (DC) have explicit statutory definitions of school readiness, or have school readiness programmes or assessments that allow such definitions to be easily inferred (Education Commission of the States, 2018[33]). According to these definitions, children will be deemed ready for school if they have demonstrated learning or development as specified in state standards in areas such as literacy/language (11 states and DC), social and emotional competence (11 states and DC), motor/physical development or health (9 states and DC), approaches to learning (5 states and DC), numeracy or mathematical thinking (5 states and DC), and self-regulation (Minnesota only). What constitutes an acceptable level of learning in each of these areas varies across jurisdictions (Education Commission of the States, 2018[33]). State departments of education write learning standards (also referred to as content standards, content area standards or academic standards, depending on the state) that they would like students to meet at different ages. In many states, these learning standards are set for children from pre-kindergarten through to twelfth grade and serve as a guide for parents and teachers with respect to children’s learning and development in a range of domains.

Many kindergarten programmes use assessments to understand what children know and can do upon entry to kindergarten. The number of states requiring kindergarten assessments is growing. As of 2018, 33 states required kindergarten entry assessments (KEAs) and at least 7 other states were piloting or exploring such assessments (Education Commission of the States, 2018[34]). Although there is no single agreed-upon KEA definition, the following definition was used in the Race to the Top, Early Learning Challenge, a federal funding competition that has driven much of the development of KEAs over recent years (Ackerman, 2018[35]):

[A kindergarten entry assessment is]…administered to children during the first few months of their admission into kindergarten; covers all Essential Domains of School Readiness; is used in conformance with the recommendations of the National Research Council reports on early childhood; and is valid and reliable for its intended purposes and for the target populations and aligned to the Early Learning and Development Standards. Results of the assessment should be used to inform efforts to close the school readiness gap at kindergarten entry and to inform instruction in the early elementary school grades. The assessment should not be used to prevent children’s entry into kindergarten (United States Department of Education, 2011[36]).

While this definition provides clarity on the intended purposes of KEAs and when they should be administered, it does not prescribe the type of assessment measure to be used, meaning states which receive federal funding have autonomy to draw on a range of direct and observational approaches to their assessments, although the selected measure should be valid and reliable (Ackerman, 2018[35]). If kindergarten entry assessments are well designed and appropriately implemented they can be useful tools for improving teaching and learning in kindergarten programmes, leading to better child outcomes (Shields, Cook and Greller, 2016[37]). However, collecting KEA data can present challenges to teachers. One such challenge is the amount of time that administering these assessments can take. Generally, KEAs are designed to be implemented 30-60 days after children enter kindergarten and, particularly in cases where assessments are based on the observation of individual children, it can be difficult for teachers to complete the assessments successfully within this period (Ackerman, 2018[35]). Policy makers in Florida removed the requirement for a language and literacy assessment to be carried out as a result of teacher objections to the amount of instructional time lost to the assessment (Ackerman, 2018[35]). Another challenge is the degree to which teachers are prepared or trained to administer the measures, both for the overall population and for subgroups for whom modifications might be needed, such as ELLs or children with special educational needs (Ackerman, 2018[35]). An additional issue is teachers’ capacity to use the collected assessment data to guide their pedagogical decisions. Kindergarten entry assessments are intended to be formative assessments, and the usefulness of the collected data will depend on how well teachers are trained and prepared to use the data to inform their teaching.

State policies also differ with respect to the age at which schooling is compulsory, ranging from five to eight years of age. By the age of six, schooling is compulsory for children in most states (see Table 2.3). Seventeen states5 and DC require children to attend kindergarten (the year before primary school) (Education Commission of the States, 2018[38]).

Table 2.3. Distribution of state compulsory school starting ages

|

Age at which school attendance is compulsory |

Number of states (including Washington DC) |

|---|---|

|

5 |

10 |

|

6 |

26 |

|

7 |

13 |

|

8 |

21 |

1. Pennsylvania and Washington.

Source: Education Commission of the States (2018[38]), Does the State Require Children to Attend Kindergarten?, http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/MBQuest2RTanw?rep=KK3Q1804.

In 42 states and DC, school districts are required to offer kindergarten. Thirteen states and DC require the district to offer full-day kindergarten, a further 26 require districts to offer half-day provision, with the remaining two states requiring either half-day or full-day kindergarten.6 Twenty states7 and DC have policies or programmes aimed at supporting transitions from pre-kindergarten settings to kindergarten. This guidance involves elements such as family engagement, written transition plans, sharing of assessment data, and meetings between providers and teachers (Education Commission of the States, 2018[39]).

Provision of early learning services

Types of early childhood provision

The provision of early years services in the United States is not easily described. The early childhood landscape is highly fragmented. Provision includes 1) centre-based ECEC services (i.e. those administered in non-residential settings in day care centres, nurseries, churches, preschools, pre-kindergartens, etc.); 2) home-based programmes (including in-home preschools as well as regulated or unregulated childminding of multiple children in a residential setting); and 3) relative care (care provided by a non-parental relative, typically in the relative’s home and/or the child’s own home). There are also auxiliary services such as parenting and home-visiting programmes aimed at supporting families with young children. Within each of these categories there is also wide variation. Centre-based ECEC programmes, for example, comprise:

…a wide range of part-day, full-school-day, and full-work day programs, under educational, social welfare, and commercial auspices, funded in a variety of ways in both the public and private sectors, designed sometimes with an emphasis on the “care” component of ECEC and at other times with stress on “education” or with equal attention to both (Kamerman and Gatenio-Gabel, 2007, p. 23[40]).

The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) distinguishes between ECEC programmes catering for the very youngest children (under three years of age) and those for children from the age of three until entry to primary school. ISCED classifies the former as Level 01 programmes (early childhood educational development programmes) while the latter are classified as ISCED Level 02 (pre-primary education programmes). To be classified at all under ISCED, an early childhood programme must contain an educational component. For example, programmes for children under three that provide supervision and care without any explicit educational focus (e.g. some day care or nursery programmes) are not classified as ISCED 01.

Prevalence and spread of services

In 2014, the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, an office of the Administration for Children and Families, administered a representative National Survey of Early Care and Education in the United Sates. The survey indicated that there were approximately 129 000 centre-based ECEC programmes in the United States, serving just under 7 million children aged five or under and not yet in kindergarten (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2014[41]).

Approximately 3.7 million home-based care providers were estimated to be caring for young children other than their own for a minimum of 5 hours a week. Approximately 118 000 of these, catering to more than 750 000 children aged five or under, were listed (i.e. they appear on national or state lists of early care and education services). Close to 1 million unlisted but paid providers were providing regular care to over 2.3 million children, while over 2.7 million unlisted and unpaid providers were providing care to over 4 million children in the 0-5 age bracket (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2016[42]).

According to the Center for American Progress, more than half (51%) of US residents in 2018 lived in neighbourhoods where the availability of licensed childcare for infants and toddlers was low, i.e. with three or more children for every available licensed childcare slot (Malik et al., 2018[43]). The growing number of workers in the United States who work unpredictable or non-standard hours (nights, weekends, holidays) also face barriers to accessing childcare, not limited to the fact that they earn disproportionately low incomes (Enchautegui, 2013[44]). According to the National Survey of Early Care and Education, 8% of the centre-based providers surveyed offered care during non-standard hours, with 2% offering care during evening hours, 6% offering overnight care and 3% offering weekend care (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2015[45]). However, it is estimated that one in five workers in the United States now work non-standard hours, and 45% of children have at least one parent working non-standard hours (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2015[45]).

Funding and costs

The funding of early years programmes in the United States is complex, ranging from privately funded centres to services supported to varying degrees by local, state or federal funds (Hustedt, West and Barnett, 2011[46]). Overall, US public spending per child on pre-primary education is USD 10 830, higher than the OECD average of USD 8 426 (OECD, 2018[47]). On average, OECD countries spend 0.8% of their GDP on ECEC, three-quarters of which is spent on pre-primary (ISCED 02) education. The United States spends 0.4% of GDP on pre-primary education, a share which is unchanged since 2005 and the 26th lowest of 33 OECD and partner countries with available data on ECEC spending (OECD, 2018[47]).

In the United States, 26% of pre-primary education is privately funded, more than the OECD average of 17% and the seventh largest share of 35 OECD and partner countries with available data in 2013. While the share of private expenditure on pre-primary education has fallen on average across OECD countries, from 21% in 2005 to 17% in 2015, the share of private expenditure in the United States increased from 21% to 26% over the same period (OECD, 2018[47]). In several states, public-private partnerships are used as a mechanism to fund ECEC provision.

Childcare is expensive in the United States. Across the OECD, net childcare costs for a family with two earners (earning 100%+67% of average earnings) and two children aged 2 and 3 years old equate to 17.5% of average earnings. In the United States, the corresponding figure is 30%, the fifth highest of all OECD countries (lower only than in Ireland, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United Kingdom). In 15 OECD countries, the net cost is no more than 10% of average earnings – for example, it is 5% in Germany and Iceland. In 2016, the cost of full-time centre-based care for children from birth to four years old in the United States was estimated to be USD 9 589, higher than the cost of in-state college tuition (USD 9 410) and 85% of the median annual cost of rent (Schulte and Durana, 2016[48]). Childcare for infants costs 12% more than for older children and is higher than the cost of in-state college tuition in 33 states (Schulte and Durana, 2016[48]).

One driver of costs is staff salaries. Required staff-child ratios vary by state but tend to be low, meaning very high labour costs for ECEC provision. Although pre-primary teachers in the United States have higher salaries than their counterparts in most other OECD countries (starting salaries were the 7th highest in the OECD in 2017, and salaries after 15 years of experience were the fifth highest) (OECD, 2018[47]), they are relatively poorly paid compared to educators of older children in the United States and many have salaries so low that they are eligible for or receive public financial assistance (United States Department of Health and Human Services and United States Department of Education, 2016[49]). Data from 2011 indicated that almost half of US childcare workers were in families enrolled in at least one public support programme annually, compared to one-quarter of all workers in the United States (Whitebrook, Phillips and Howes, 2014[50]).

Federal funding

Federal funding for early childhood care and education programmes in the United States is generally targeted at specific subgroups of children, primarily children from low-income families and children with disabilities. The US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Department of Education have primary responsibility for administering this federal funding.

Head Start is a federally funded programme that provides services to support the development of three- and four-year-old children from low-income families. Head Start is a programme of the Department of Health and Human Services, first introduced in 1965 as a means of addressing poverty. Head Start centres follow a federally mandated research-based curriculum, the goal of which is to promote school readiness among at-risk children who are eligible for the programme on the basis of low family income, by enhancing their cognitive, social and emotional development. The programme also focuses on health, nutrition and parental involvement. Eligibility for Head Start is determined locally, but families are likely to be eligible if their income falls below federal poverty levels (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012[51]). Programmes may enrol some children from families whose income exceeds the poverty level if they meet other eligibility criteria (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012[51]). Early Head Start was introduced in 1994 as a service for low-income families with children under three. Early Head Start offers a home-based option, involving weekly home visits, as well as centre-based services. Head Start first launched American Indian and Alaska Native Head Start programmes in 1965. Migrant and Seasonal Head Start serves the families of migrant farm workers. It started serving migrant children and families in 1969 and the programme was extended to seasonal children and families in 1999 (Schmit, 2014[52]).

In 2017, over USD 9.2 billion was allocated for Head Start, including Early Head Start (Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center, 2018[53]). Head Start grants are awarded directly to public agencies, private for-profit and non-profit entities, school systems, and tribal governments to operate Head Start in local communities Federal grants cover 80% of the programme’s cost; the remaining 20% is funded by the community organisation administering the programme (by cash or in-kind donations) (National Center on Program Management and Fiscal Operations, 2014[54]). Head Start programmes must meet mandatory performance standards relating to staff qualifications, staff-child ratios, training and professional development. For example, Early Head Start programmes serving a majority of children under 36 months old must have two teachers for no more than eight children or three teachers with no more than nine. Classes with a majority of three-year-olds must have no more than 17 children with 2 teachers or with a teacher and a teaching assistant, while classes serving a majority of four- and five-year-olds must have no more than 20 children with 2 teachers or a teacher and a teaching assistant. Where more stringent requirements have been set locally, programmes must adhere to these (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016[55]). It is required that 50% of Head Start teachers nationally have a bachelor’s degree in early childhood development, early childhood education or equivalent. Programmes must offer opportunities for parents and families to be engaged in the services.

The Department of Health and Human Services provides childcare subsidies for low-income working families with children under the age of 13 under the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) Act, which was first enacted in 1990. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 created the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), which consolidated the funds appropriated for the CCDBG with entitlement funds under the Social Security Act into a single source of federal childcare funding for states and territories. States use the CCDF to provide financial assistance to low-income families to access childcare so that parents can attend work, training and education, and also use funds to improve the quality of childcare. Congress approved a USD 2.37 billion increase in the CCDBG in March 2018, the largest ever increase. For the fiscal year 2019, CCDBG funding was USD 5.3 billion.

The CCDF also draws federal money from Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), a federal funding source aimed at supporting low-income families to become self-sufficient. Block grants are given to states in order to develop and operate programmes focused on supporting parental employment as well as child and family well-being, and some states use these funds to provide childcare assistance (Office of Child Care, 2014[56]). States are permitted to allocate up to 30% of their TANF grant to CCDF subsidies.

The Maternal Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program is a federally funded programme that supports at-risk parents of children from birth to kindergarten entry to develop parenting skills that are supportive of children’s physical, emotional and social health. The programme is allocated approximately USD 400 million per annum.

In addition to these funding sources from the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Education also funds early childhood services. Title 1, Part A of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (also known as Improving the Academic Achievement of the Disadvantaged) provides federal funds to local education authorities (LEAs) or schools with large concentrations of children from low-income families in order to support at-risk children to meet state academic standards. Title 1 funds may be used to operate preschool programs that “improve cognitive, health, and social-emotional outcomes for eligible children below the grade at which an LEA provides a free public elementary education”.

The US Department of Education provides grants to all states, DC and Puerto Rico in order to provide special education and related services for children with disabilities aged between three and five years, under Section 619 of IDEA. Under IDEA Part C, states and territories are awarded grants to support the implementation of integrated, multidisciplinary, interagency early intervention programmes for children with disabilities from birth until the age of two.

The Preschool Development Grants competition is an initiative of the Department of Education that aims to 1) support states to develop or improve preschool infrastructure in order to deliver high-quality preschool education to children; and 2) to expand existing high-quality programmes in targeted communities that could serve as models for expanding provision to all four-year-olds in the state from low- or middle-income families. To date, development grants have been awarded to Alabama, Arizona, Hawaii, Montana and Nevada. Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont and Virginia have all received expansion grants.

There are also several other national initiatives aimed at promoting early learning or reducing gaps in early learning outcomes. Reach Out and Read (ROR) is a non-profit organisation that promotes childhood literacy. Founded by two paediatricians in response to a growing literacy problem in the United States in the late 1980s, ROR has received funding from the US Department of Education since 2001 and is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The organisation’s mission is to encourage parents to read regularly to their children and give them the tools (the books) to do so. Annually, ROR provides over 6 million books through more than 4 500 healthcare settings in the United States, reaching more than 3.8 million children. Another relevant national campaign is Too Small to Fail whose mission is to raise public awareness of the importance of brain and language development in the early years. Too Small to Fail aims to empower parents to support their young children’s development at home by talking, reading and singing to and with their children from birth.

State funding

Publicly funded kindergarten is available to all children in the United States. The degree to which children have access to public pre-kindergarten education (other than those children in targeted federally funded programmes) varies considerably, from none at all in some states to universal provision in others. In the District of Colombia, Florida and Vermont, publicly-funded pre-k is available to all children, with no funding or enrolment caps or enrolment deadlines (Parker, Diffey and Atchison, 2018[57]). West Virginia is aiming for universal pre-k and is expanding its provision. Universal pre-k is in place in most districts in Oklahoma. In the states of Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, New York and Wisconsin, pre-k policies are in place that are commonly considered to be universal, but have limits meaning that, in practice, provision is not available to all children (Parker, Diffey and Atchison, 2018[57]). In New Jersey, universal pre-k is provided to children in 31 high-poverty districts. Alabama is also moving towards universal pre-k provision.

From 2013 to 2018, states collectively increased their spending on pre-kindergarten programmes by 47% (Parker, Diffey and Atchison, 2018[57]). Six states – Idaho, Montana, New Hampshire, South Dakota, North Dakota and Wyoming – did not contribute to pre-kindergarten programmes in 2016-17, meaning 44 states and DC funded preschool to some degree. Spending per child varies considerably by state. Seven states spent at least USD 7 000 per child in 2017, while seven states spent less than USD 3 000 per child (Parker, Diffey and Atchison, 2018[57]).

States use various revenue streams to fund pre-kindergarten programmes. In many states, this funding is neither stable nor guaranteed from year to year. Several states use funds collected through state sin taxes (e.g. taxes levied on alcohol or tobacco). Five states (Georgia, Virginia, Washington, Nebraska and North Carolina) use money from a state lottery to fund pre-k, while Missouri uses funds from non-lottery gambling revenue. Three states (Arizona, Connecticut and Kansas) use money from tobacco settlements to fund pre-k. Social impact bonds, where private funds are used to fund social initiatives, fund pre-k in some states. In Utah, for example, the Pay for Success pre-k programme is a partnership between the state of Utah and Goldman Sachs (Parker, Diffey and Atchison, 2018[57]).

Funds for pre-kindergarten are often administered by states via block grants to localities, with a high level of autonomy at the local level over how the grants are used (Parker, Diffey and Atchison, 2018[57]). Block grants are typically used to direct funding to specific communities or specific subgroups of children with high levels of need. Some local governments also adopt universal pre-k policies at the level of district, city or county (Parker, Diffey and Atchison, 2018[57]). In nine states8 and DC, the funding formula for pre-kindergarten systems is similar to the formula used to fund state K-12 education systems. Typically, these funding formulae involve a per-student rate of funding; in three states (Maine, Oklahoma and West Virginia), the funding allocated to pre-k students is at least as much per child as in the K-12 system.

Other features of provision

Another notable feature of the pre-primary sector is that the number of days in a pre-primary school year is especially low in the United States; in line with the K-12 school year, the pre-primary school year is 180 days, shorter than most OECD countries (OECD, 2018[47]). In the United States, 6% of pre-primary teachers are men. Although still low, this is one of the highest rates of male pre-primary teachers among OECD countries (OECD, 2018[47]).

Participation

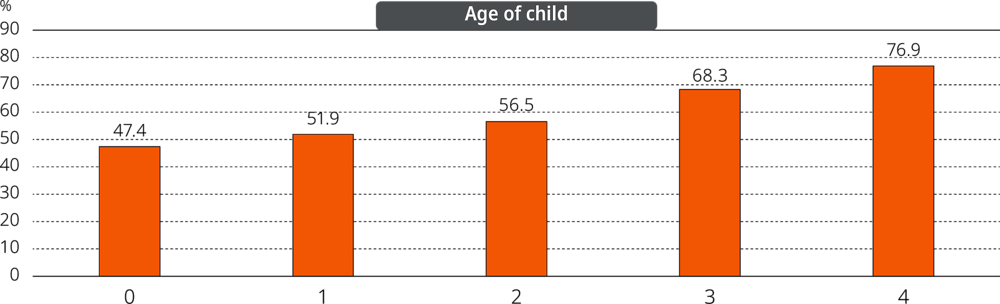

According to findings from the Early Childhood Program Participation Survey conducted as part of the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2016, approximately 60% of children under the age of five in the United States are in a regular non-parental childcare or early education arrangement at least once a week (Corcoran, Steinley and Grady, 2019[58]). The proportion of children in such an arrangement increases with the age of child, from 47% of infants under the age of one to 77% of four-year-olds (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Attendance at any non-parental childcare or programme arrangement at least once a week by age, United States

Source: Early Childhood Program Participation Survey 2016, NCES (2018[59]), National Household Education Survey Programs of 2016: Public-Use Data Files, https://nces.ed.gov/pubSearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2018104.

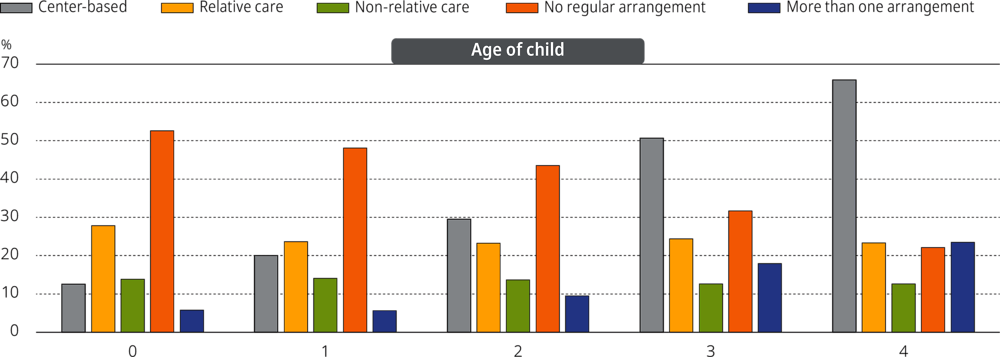

The Early Childhood Program Participation Survey also collected information on the type of care or education settings that children are in at different ages. As Figure 2.2 shows, the proportion of children taken care of in the home of a relative is relatively stable across the different ages, around one in four children from 0 to 4. Similarly, there is little variation in the proportion cared for in the home of a non-relative by age of child, with 13-14% of children in this type of care arrangement at each of the ages from birth to four. The proportion of children in centre-based ECEC increases with age, from just under 13% of infants under the age of one to 66% of four-year-olds. The proportion of children in two or more different non-parental childcare arrangements also increases with the age of the child, from 6% of those under one to 26% of four-year-olds.

Figure 2.2. Attendance rates of different types of non-parental childcare or programme arrangement by age, United States

Source: Early Childhood Program Participation Survey 2016, NCES (2018[59]), National Household Education Survey Programs of 2016: Public-Use Data Files, https://nces.ed.gov/pubSearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2018104.

The survey also provided information on the intensity of children’s participation in centre-based programmes. Only one in eight children under one and one in five children aged one spend any time in centre-based care, but those children who do attend spend a relatively large amount of time in there, on average. As Table 2.4 shows, at all ages from birth to four, children who attend centre-based settings most often spend 40 hours per week (the mode) in these settings as opposed to more or fewer hours. The mean number of hours spent in centre-based settings is highest among the youngest children (at 31 hours per week for those aged one and under one) and lowest among four-year-olds (22 hours per week). On the other hand, two-thirds of four-year-olds spend at least some time in centre-based care and there is greater variation amongst this age group in terms of the number of hours they spend there. Four-year-olds are more likely to be in another care or education arrangement in addition to their centre-based arrangement than children aged one or under (24% of four-year-olds and 6% of those aged one and under), which may also explain the lower mean number of hours spent in centres. Infants and toddlers (i.e. children under the age of three) are likely to be looked after in centres where the primary emphasis is on care, probably while their parents are working. Older children (three- and four-year-olds) are likely to be attending preschool settings that have an educational component and emphasise the development of their cognitive and social skills. As the hours of these preschool programmes tend to vary (with some, for example, only offering half-day provision), older children are more likely to require additional care arrangements to supplement these hours.

Table 2.4. Attendance rates and hours per week spent in centre-based programmes by age, United States

|

Age |

% attending |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0 |

12.5 |

2 |

60 |

30.8 |

36 |

40 |

|

1 |

20.1 |

2 |

60 |

31.1 |

40 |

40 |

|

2 |

29.5 |

1 |

50 |

25.1 |

24 |

40 |

|

3 |

50.7 |

2 |

60 |

21.6 |

16 |

40 |

|

4 |

65.8 |

1 |

70 |

20.9 |

15 |

40 |

Source: Early Childhood Program Participation Survey 2016, NCES (2018[59]), National Household Education Survey Programs of 2016: Public-Use Data Files, https://nces.ed.gov/pubSearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2018104.

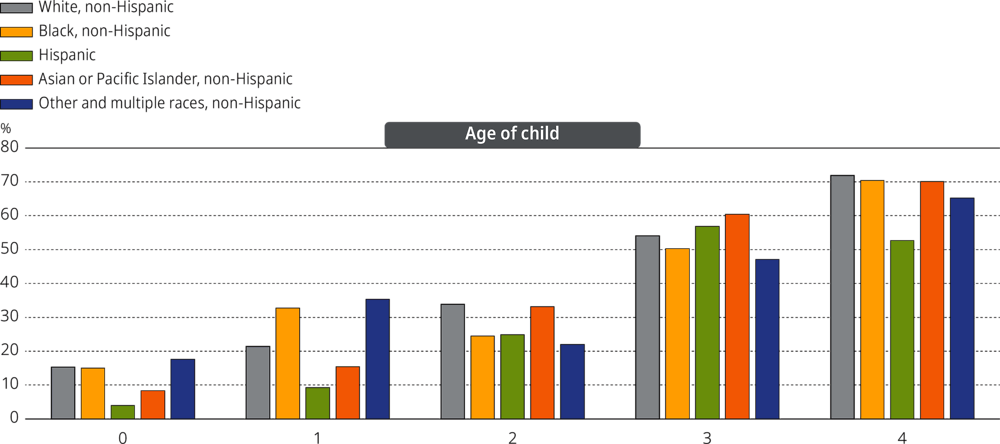

Centre-based programme attendance varies by racial and ethnic background (Figure 2.3). Children of Hispanic origin are less likely to attend centres than their peers. For example, 53% of Hispanic four-year-olds attended centre-based programmes in 2016, compared to 65-72% of children of other races or ethnicities.

Figure 2.3. Centre-based ECEC attendance rates among children under five by racial and ethnic background, United States

Source: Early Childhood Program Participation Survey 2016, NCES (2018[59]), National Household Education Survey Programs of 2016: Public-Use Data Files, https://nces.ed.gov/pubSearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2018104.

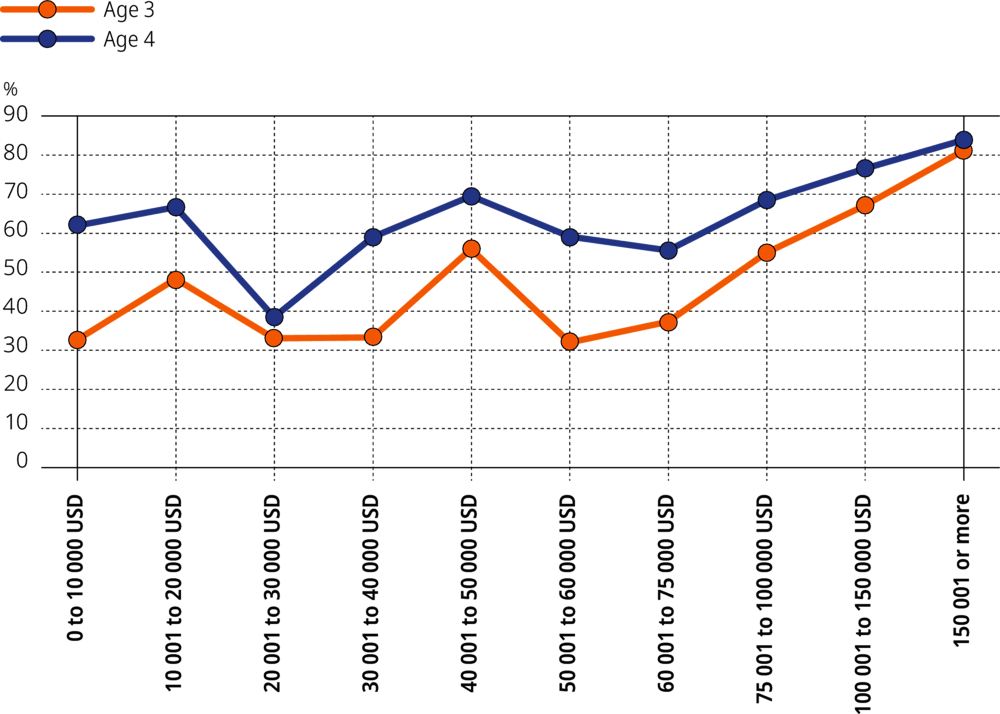

Attendance at centre-based ECEC programmes is highest among children from high-income families. Figure 2.4 shows the percentage of three- and four-year-olds regularly attending ECEC centres by total family income level. Fewer than half of three-year-olds from households where the total income does not exceed USD 40 000 regularly attend ECEC centres, compared with over 80% of three-year-olds in households where the total income exceeds USD 150 000. Similarly, while attendance rates are higher at the age of four than at three for children from families at all income levels, they are highest among children from households with the highest income levels at both ages.

Figure 2.4. Attendance rates of any type of non-parental childcare or programme arrangement among children under five by total household income level, United States

Source: Early Childhood Program Participation Survey 2016, NCES (2018[59]), National Household Education Survey Programs of 2016: Public-Use Data Files, https://nces.ed.gov/pubSearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2018104.

Figure 2.4 shows a dip in participation rates for children from families with a total household income of between USD 20 001 and USD 30 000. This probably reflects that a proportion of families in this income bracket lie just above the poverty line and may therefore miss out on eligibility for state- or federally funded programmes targeted at children in poverty.

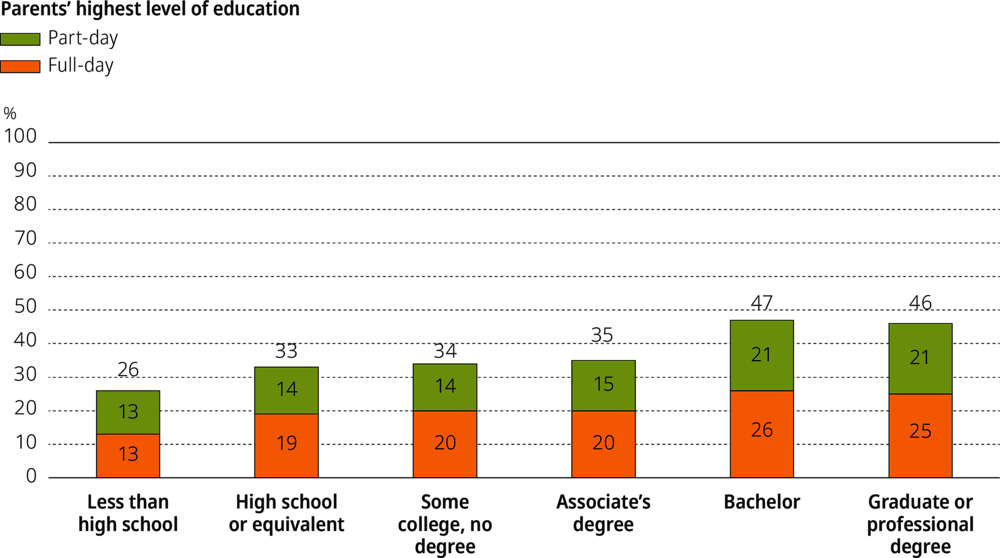

Enrolment in pre-primary education is also related to parents’ educational attainment (NCES, 2019[60]). In 2017, the enrolment of three- to five-year-olds in full-day preschool programmes was higher for children whose parents held a graduate or professional degree (25%) or a bachelor’s degree (26%) than for children whose parents highest level of educational attainment was a high school qualification (19%) or lower (13%) (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Attendance rates for part-day and full-day pre-primary programmes among 3-5 year-olds by parents’ educational attainment, United States

Source: US Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, NCES (2019[60]), Preschool and Kindergarten Enrollment Indicator, February (2019), https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cfa.asp.

In 2016-17, total enrolment in Early Head Start reached 211 000 children, the highest since the programme began, representing 7% of eligible children (children under the age of three living in poverty). In the same year, enrolment for Head Start was 848 000, a record low, representing 31% of three- to five-year-olds of children living in poverty9 (Child Trends, 2018[61]). This drop may be attributable to increased public spending on pre-kindergarten programmes, which rose by 47% in the five years to 2016/17 (Diffey, Parker and Atchison, 2017[62]). Children who would have traditionally have attended Head Start programmes may instead be in other public pre-kindergarten programmes. Head Start enrolment rates vary considerably by race. In the 2016/17 school year, 79% of eligible American Indian and Alaska Native children were enrolled in Head Start, compared with 68% of children of two or more races, 42% of children of Black children, 27% of Asian children and 25% of White children (Child Trends, 2018[61]). In the same year, 17% of children aged five or under who were eligible for Migrant and Seasonal Head Start were enrolled in the programme.

Levels of ECEC participation are lower in the United States than in many other OECD countries. In 2016, 38% of three-year-olds and 67% of four-year-olds in the United States were enrolled in ISCED 02 programmes,10 lower than the averages of 76% of three-year-olds and 88% of four-year-olds across OECD countries. Additionally, while the proportion of 3-5 year-olds attending ECEC has increased on average across OECD countries, from 75% in 2005 to 85% in 2016, participation has remained static in the United States, at 66% (OECD, 2018[47]). The cost of ECEC in the United States is likely to be one factor behind these relatively low participation rates.

Quality and impact of early childhood services

In the United States, all states have licensing laws that establish minimum quality standards for early childhood care and education services. While these vary somewhat by state, they are generally designed to ensure the health and safety of children by establishing minimum requirements for the physical environments in which care and education are delivered, as well as maximum staff-child ratios. Given their limited focus on health and safety, these minimum quality standards may not be sufficient to ensure that adequate care and education of children is delivered in ECEC programmes (Horm, Barbour and Huss-Hage, 2019[63]).

Quality rating and improvement systems

In response to concerns that poor-quality programmes were being subsidised by public funds, quality rating and improvement systems (QRISs) for ECEC programmes began to be developed in the United States towards the end of the 1990s (Cannon et al., 2017[64]). The primary idea behind a QRIS is to offer incentives for programmes to improve the quality of the services that they provide which should, in turn, improve early cognitive and social-emotional outcomes. QRISs were intended to provide a means of directing higher childcare subsidy reimbursement rates towards higher quality providers and to encourage quality improvements. The first state-wide QRIS was introduced by Oklahoma in 1998. As of 2018, 43 states and DC had state-wide QRISs in place, with systems being piloted in a further 3 states. Regional or local QRISs were in operation in an additional three states (National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance, 2019[65]).

While each QRIS is different, they have some common features. In most cases, the systems are voluntary and most provide supports to ECEC programmes in order to improve their quality. QRISs generally involve 3-5 level rating scales (stars, steps, etc.) used to indicate overall programme quality, based on assessments of a number of quality indicators such as curriculum, staff qualifications and training, interpersonal interactions, health and safety, assessment, leadership, and programme administration. Given that indicators of structural quality (material, static features of programmes and staff working in them) are much easier to measure and monitor than indicators of process quality (staff-child and staff-staff interactions, child-child relationships and interactions), QRISs focus much more strongly on the former (Schulte and Durana, 2016[48]). The particular indicators selected and the ways in which these are combined to produce overall summary ratings of quality differ across states. For example, while the vast majority of QRISs include a measure on the classroom environment, it is rare for systems to include a quality standard relating to whether the programme has a written curriculum (Cannon et al., 2017[64]).

Multiple studies have been undertaken with the aim of validating QRISs, generally taking one of two approaches: 1) exploring how QRIS ratings correlate with external measures of quality; or 2) exploring how QRIS ratings correlate with children’s developmental outcomes. On the whole, positive associations have been found between QRIS ratings and external measures of quality; while statistically significant, the associations are generally small (Tout et al., 2018[66]). Studies on the associations between QRIS ratings and children’s development have also tended to show small positive associations, although the evidence is inconsistent; in some states, child development in some domains is significantly positively associated with QRIS ratings, but not in others (Tout et al., 2018[66]).

Accreditation of early childhood services

Another mechanism for promoting higher quality in early childhood education and care is through the accreditation of early childhood programmes. Accreditation can also help families to identify high-quality programmes for their children. An ECEC service is accredited if it is deemed by an external and recognised body to have met certain quality standards. Accreditation is currently voluntary in all states. Several organisations offer accreditation of early childhood programs in the United States, including the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), the National Accreditation Commission for Early Care and Education Programs (NAC), the National Early Childhood Program Accreditation, Accredited Professional Preschool Learning Environment and the National Association for Family Child Care. There are also specialised accreditation bodies that accredited specific types of programmes, such as the American Montessori Society, the Association of Christian Schools International and the National Lutheran Schools Accreditation. The NAEYC is the largest accrediting organisation, deemed by many to represent the gold standard for quality. Approximately 7 000 programmes catering to close to 1 million children are accredited by the NAEYC, representing just 6% of all eligible programmes (Horm, Barbour and Huss-Hage, 2019[63]). In 2016, just 11% of childcare establishments were accredited by either the NAEYC or the NAC. Accreditation rates varied considerably across states, with just 1% of childcare centres and home-based providers in South Dakota accredited in 2016, compared to 46% in Connecticut (Schulte and Durana, 2016[48]).

Quality of state preschool programmes

Since 2002, the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) has produced annual reports tracking preschool access, resources and quality in state preschool programmes. A programme qualifies as a state preschool programme if it is funded, directed and controlled by the state; serves children of preschool age (typically three- and four-year-olds); has early education as a primary focus; and offers a group learning experience to children on at least two days each week. Programmes meeting these criteria are evaluated against minimum quality standards benchmarks. For the year 2017, ten benchmarks were used to evaluate the quality of state preschool programmes (Table 2.5).

Table 2.5. National Institute for Early Education Research quality standards and benchmarks for state preschool programmes, 2017

|

Benchmark |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Early learning and development standards |

These are the goals of a state’s preschool programme and should outline clear and appropriate goals for children’s learning and development in a range of domains to meet this benchmark. |

|

Curriculum support |

States meet this benchmark if they 1) provide guidance or an approval process for curriculum selection; and 2) provide ongoing training or other assistance to facilitate implementation of the curriculum. |

|

Teacher degree |

States must require the lead teacher in every classroom to have at least a bachelor’s degree to meet this benchmark. |

|

Teacher specialised training |

Programmes in which preschool lead teachers are required to have had specialised training in the area of child development or early childhood education meet this benchmark. |

|

Assistant teacher degree |

To meet this benchmark, programmes must require assistant teachers to have a Child Development Associate qualification or equivalent. |

|

Staff professional development |

Programmes meet this benchmark if both teachers and assistant teachers are required to have at least 15 hours of in-service training annually. |

|

Maximum class size |

A maximum class size of 20 is required to meet this benchmark. |

|

Staff-child ratio |

Classes must have no more than 10 children per adult to meet this benchmark. |

|

Screenings and referrals |

Programmes must require that children have hearing, vision and other health screenings and, where appropriate, referrals to meet this benchmark. |

|

Continuous quality improvement system |

In order to meet this benchmark, programmes must require that 1) data on quality is collected in a systematic way at least once per year and 2) the state and local programmes use these data to improve their policies and practices. |

Source: Friedman-Krauss et al. (2018[67]), State Preschool Yearbook: The State of Preschool 2017, http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/State-of-Preschool-2017-Full-2-13-19_reduced.pdf.

According to the NIEER, progress has been made across states since 2002 in adopting policies that are supportive of preschool quality. In 2002, no state programme met all ten of the quality standard benchmarks, just three programmes met nine, and ten state preschool programmes met fewer than half of the benchmarks (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2018[67]). In contrast, 5 programmes met all 10 quality standard benchmarks in 2017,11 and a further 15 programmes met 9 of the 10 benchmarks. However, progress can be characterised as uneven. Ten states have made no gains since 2002. Policy changes meant six state programmes met fewer benchmarks in 2017 than in 2002 (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2018[67]). In 2017, nine state preschool programmes met fewer than five of the NIEER’s ten quality standards benchmarks. Some of the states that meet the fewest benchmarks of quality are those catering for very large numbers of children, (including large numbers of children living in poverty), such as California, Florida and Texas (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2018[67]).

Quality and impact of Head Start

A body of evidence also exists relating to the quality and efficacy of Head Start and Early Head Start. As mentioned earlier, Head Start programmes must adhere to certain quality standards and, as a result, Head Start centres tend to be of higher quality than other centre-based options available to low-income families (Currie and Neidell, 2004[68]). Evidence on the effects of Head Start attendance on child outcomes, however, is mixed. The US Congress mandated an impact study of Head Start in 1998. The study commenced in 2002 and involved the random assignment of close to 5 000 three- and four-year-olds (who had not previously attended Early Head Start) to either Head Start or a comparison group. When assessed at the end of one year of Head Start, four-year-olds in the treatment group displayed language and literacy advantages over those in the control group (OPRE, 2010[69]). In the three-year-old cohort, benefits in language and literacy were also accompanied by superior performance on measures of perceptual motor skill and mathematics. Head Start attendees also displayed less hyperactive behaviour and less withdrawn behaviour than their peers assigned to the control. Other benefits of Head Start for three-year-olds included greater levels of parental reading to children and of family cultural activities (OPRE, 2010[69]). However, when the children were assessed again at the end of first grade, many of these early benefits were no longer discernible.

A randomised controlled trial conducted to evaluate the impact of Early Head Start on child outcomes such as attention, cognition, language, behaviour and health found that the programme did benefit children and families, with significant effects in all developmental domains when children were assessed at the ages of two and three (Love et al., 2013[70]). Effect sizes were modest, ranging from .10 to .20. When followed up at the age of five, children who had attended Early Head Start had better approaches to learning and displayed better attention than children in the control group. Among Black children who attended the programmes, cognitive benefits were also found to have been sustained at the age of five, as were language impacts for Spanish-speaking Hispanic children (Love et al., 2013[70]).

Learning outcomes across the United States education system

Nationally representative information on early childhood outcomes in the United States is available from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS), a research programme of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). The ECLS programme comprises three cohorts: one nationally representative birth cohort (children born in 2001) and two representative kindergarten cohorts (the kindergarten classes of 1998/99 and of 2010/11). Data collected from the first kindergarten cohort (ECLS-K:1998) revealed the presence of group differences in outcomes at kindergarten entry, and so the ECLS Birth Cohort (ECLS-B) study was conducted to investigate children’s early development and learning from birth through to kindergarten in order to identify the sources of these early differences. Data were collected from multiple informants, including care providers, teachers, parents and children themselves at around nine months, two years and at preschool age (around the age of four). Among four-year-olds, gender differences in learning and development were evident: girls had significantly higher levels of receptive and expressive language skills than boys and also scored significantly higher on measures of fine motor skills (Chernoff et al., 2007[71]). Some racial and ethnic disparities were also evident at the age of four. White and Asian children demonstrated significantly better colour knowledge than Black and Hispanic children, for example. Children in two-parent homes displayed better literacy skills than their peers in single-parent households. Mathematics ability varied significantly by family socio-economic status (SES): while 65% of all four-year-olds demonstrated proficiency in the number and shape assessment area, this ranged from 40% of children from lower SES families to 87% of children from higher SES backgrounds (Chernoff et al., 2007[71]). While the ECLS provides reliable and valid data on early childhood outcomes in the United States, it does not readily permit the evaluation of how they compare to those in other countries.

Many of the subgroup differences identified in ECLS are also evidenced in assessments of older students in the United States, where they appear even more pronounced. For example, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) conducted by the NCES consistently shows academic achievement gaps along racial and ethnic lines among students in fourth and eighth grades. White (non-Hispanic) children significantly outperform Hispanic children and Black (non-Hispanic) children on the assessments, although the magnitude of the inequalities appears to be reducing over time. In fact, the racial and ethnic achievement gaps as assessed in NAEP have been narrowing at every grade level and every subject since the 1990s. However, the gaps may still be characterised as large, ranging from 0.6 to 0.8 standard deviations, or approximately one and a half years of typical average academic progress (Hansen et al., 2018[72]). Many more states have large achievement gaps (greater than 0.8 standard deviations) between White and Black students than between White and Hispanic students (Hansen et al., 2018[72]). Considerable research evidence indicates that focusing on children’s earliest years has promise as a means of eradicating these gaps, by addressing their root causes before the gaps emerge. (Schweinhart, 2013[73]; Kautz et al., 2014[74]).

Children from poor backgrounds tend to have poorer educational outcomes in the United States. In 2017, the achievement gaps between children from poor families (based on their eligibility for free or reduced-price lunches in NAEP) and others were in the region of 0.75 standard deviations at both fourth grade and eighth grade (Hansen et al., 2018[72]). While racial and ethnic achievement gaps as measured in NAEP have been narrowing over time, income gaps have remained static (Hansen et al., 2018[72]). In fact, when comparing children in the lowest income decile to those in the highest, achievement gaps have actually widened over recent decades (Reardon, 2013[75]). In the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), US students classified as socio-economically disadvantaged were 2.5 times more likely to be low performers than their advantaged peers (OECD, 2016[76]). However, almost one in three (32%) disadvantaged students in the United States could be classified as “resilient”, in that they performed significantly better than expected on the basis of their socio-economic circumstances. Disadvantaged US students were also in the top quartile of similarly disadvantaged students across the countries and economies that participated in PISA 2015, highlighting that socio-economic disadvantage does not necessarily consign students to poor academic outcomes in the United States (OECD, 2016[76]). Previous research has found attending high quality early childhood programmes to be a determinant of academic resilience among disadvantaged students (Reynolds et al., 2002[77]). IELS enables the nature of socio-economic gaps in early learning in the United States, and how these compare with gaps in other participating countries, to be explored.

In NAEP 2017, 11% of fourth grade and 6% of eighth grade students were categorised as English language learners. Students classified as English language learners in both grades performed significantly less well than their non-ELL peers in both reading (NCES, 2017[78]) and mathematics (NCES, 2017[79]), with larger score-point gaps in reading.12 The size of these gaps between ELL students and others may be partly attributable to differences in their socio-economic backgrounds, but strong associations between students’ linguistic profile and their academic achievement persist after controlling for socio-economic status (Reardon and Galindo, 2009[80]). This suggests that this subgroup of students need additional support. IELS collects information on children’s home languages and whether having a language at home that is different from the language of the school is associated with different early learning outcomes in a range of cognitive and social-emotional domains at the age of five.

Another group of children in the United States who tend to have poorer educational outcomes than their peers are those with disabilities. In the 2017 NAEP, the majority of students with disabilities performed in the “below basic” proficiency levels. The achievement gaps between students with disabilities and those without were substantial. There has been little evidence of improvement in the academic performance of children with disabilities in recent years. In NAEP 2017, average performance scores for students in fourth grade with disabilities were at their lowest level since 2003, while eighth grade students with disabilities had the same average score as a decade previously (Hansen et al., 2018[72]). The gaps in educational achievement between children with disabilities and those without have thus shown no signs of narrowing over recent years. IELS collects information from parents about whether children have experienced a range of early challenges or difficulties, such as low birth weight or premature birth and learning difficulties, and how each of these relates to children’s learning at the age of five.

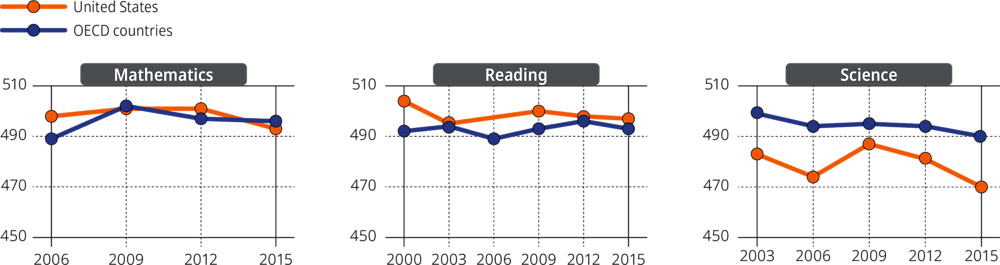

National data such as those collected as part of NAEP and the ECLS cannot tell us about how students’ educational outcomes in the United States compare to students in other education systems. While the United States has up to now not had internationally comparable data on five-year-old’s early learning, it does participate in a number of international large-scale assessments of the achievement of older students that allow the United States’ education outcomes to be compared with those of other countries.

In the 2016 round of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS 2016), the mean reading score of Grade 4 (fourth grade) students in the United States was significantly higher than the PIRLS centrepoint (the average score when the study first took place in 2001), and significantly higher than the mean scores of 26 other countries in 2016 (out of a total of 50 participating countries), including Germany, France and New Zealand. However, New Zealand was the only predominantly English-speaking country significantly outperformed by the United States in PIRLS 2016. The mean score in the United States was significantly lower than that of 11 education systems, including Finland, Hong Kong (China) and Norway, as well as English-speaking countries and economies such as Ireland, Northern Ireland and England. The United States’ mean score did not differ significantly from those of 12 other countries, meaning that there were similar levels of reading achievement in the United States and countries such as Sweden and Slovenia, as well as English-speaking countries such as Canada and Australia (Mullis et al., 2017[81]). The mean score of US students in PIRLS 2016 was significantly lower than that of US students in 2011 and was not significantly different from the mean score in 2001.

In the 2015 round of the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS 2015), the mean mathematics score of Grade 4 (fourth grade) students was significantly higher than the TIMSS centrepoint and significantly higher than the average score of 34 education systems and significantly lower than that of 10 others. Grade 4 students in the United States had similar average scores to those in Denmark, England, Kazakhstan, Portugal and Quebec. The average score of US Grade 8 students was also significantly higher than the TIMSS centrepoint and they significantly outperformed their counterparts in 24 education systems and were significantly outperformed by those in 8. Similarly performing systems included Denmark, Finland and Kazakhstan (Mullis et al., 2016[82]). At both grade levels, average mathematics scores have increased since the first administration of TIMSS in 1995.