Although in many countries upper secondary Vocational education and training (VET) serves both teenagers and adults, in a few countries initial upper secondary education is predominantly general. In Canada, Ireland and New Zealand, vocational programmes mostly serve those who have completed their initial schooling, and less than 12% of 15-19 year-old upper secondary students are pursuing VET. In contrast, there are 11 OECD countries where the majority of 15-19 year-olds enrolled in upper secondary education are in vocational programmes.

Most upper secondary VET students are in programmes that offer direct access to tertiary education. Countries where around 30% or more vocational students enrolled in programmes that lead to full level completion without direct access to tertiary education tend to be those with multiple vocational tracks (e.g. Hungary, the Netherlands, Slovenia) and bridging options to allow progression to higher levels of education.

In Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia and Switzerland, around nine out of ten upper secondary VET students are in a combined school- and work-based programme, spending at least one-quarter of their time in work-based learning, but in 10 countries, the share is less than one in five.

School-based programmes which include shorter periods of work-based learning, accounting for less than 25% of the programme, are common in vocational upper secondary programmes. In Austria about half of VET students pursue a programme with a short internship, which together with apprenticeships mean that nearly all students benefit from work-based learning. Short internships are also commonly used in Costa Rica, Lithuania, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden.

Education at a Glance 2023

Indicator B1. Who participates in education?

Highlights

Context

Vocational education and training (VET) is seen as a powerful tool to facilitate school-to-work transitions, as well as allowing adults to upskill and reskill in a time of rapidly changing labour market needs. It can also help engage learners less attracted to academic forms of learning, helping them to complete upper secondary education and prepare for entry into the labour market. While the traditional focus of vocational programmes has often been on occupational training, there is increasing awareness that VET graduates need to be able to access and benefit from higher level learning opportunities (see Vanderweyer and Verhagen (2020[2]) for a comparative analysis of changing labour markets for VET graduates). While not all VET graduates will want to pursue higher level studies, having the option should make vocational programmes more attractive, support equity and underpin lifelong learning. It is therefore important to ensure good progression pathways from VET to higher levels of education (OECD, 2022[3]).

Countries vary widely in the role that vocational programmes play in the education and training system: the level at which programmes are provided, how they are delivered and the profile of students served. Some countries traditionally have a substantial VET system at upper secondary level, with a large share of students pursuing a vocational route, with often more than one track available for them to choose from. But there are also countries where occupational training mostly takes place outside the initial schooling system, so that vocational programmes either do not exist at upper secondary level or are very small, or mostly serve young adults rather than teenagers.

Beyond overall VET participation, understanding how well learners in these programmes are being prepared for emerging green jobs and provided with green skills and competencies is central. As economies become greener, labour markets will need new skills, while others become obsolete. VET has a key role to play in this respect. It prepares learners for the labour market and should therefore ensure that the skills it is developing correspond to those needed in a greener economy. VET is also vital for providing opportunities for upskilling and reskilling of adults: it can support workers who are faced with changes in their jobs due to the green transition or who need to move into a new greener job (CEDEFOP, 2022[4]).

Vocational programmes at higher levels (post-secondary non-tertiary and short-cycle tertiary) can also play different roles. They may offer occupational preparation to graduates of upper secondary education in countries with mostly comprehensive schooling. Alternatively, they may allow upper secondary VET graduates to deepen their skills in a specific area through higher vocational programmes (See Box B5.1 in Indicator B5).

Data on enrolment patterns, exploring participation at different levels of education and among students of different ages shed light on the function of vocational programmes in different country contexts.

Other findings

On average, around two-thirds of 20-24 year-olds who are pursuing upper secondary education, are in VET programmes. In those countries that offer them, the average age of students in vocational programmes at post-secondary non-tertiary level is 30 years old, compared to 27 years at short-cycle tertiary level.

On average 75% of upper secondary VET students pursue a programme that yields direct access to tertiary education. In most cases, this means eligibility for all types of tertiary education, but in some countries, access is limited to short-cycle tertiary education (e.g. Austria, Luxembourg, Norway and Spain) or to some applied, professionally oriented bachelor’s programmes (e.g. Germany, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Switzerland). In all cases, there are bridging programmes giving access to a wider range of tertiary options.

Countries that offer vocational upper secondary programmes without direct access to tertiary education also provide bridging options for VET graduates. These may take different forms, including bridging programmes at upper secondary level (e.g. the Czech Republic, Hungary, Iceland, Poland and Slovenia), another vocational programme with access to tertiary education, or bridging programmes at post-secondary non-tertiary level (e.g. the Flemish and French Communities of Belgium, Germany, and the Slovak Republic).

Note

Given the focus on this edition of Education at a Glance, Indicator B1 focuses on vocational programmes, in particular those at upper secondary level, as VET plays an important role in the education and training systems in many OECD countries.

Analysis

Participation in education and training

Data on participation in vocational programmes provide insights on the importance of VET in the education and training systems of different countries, where there is considerable variation, especially at upper secondary level. Participation patterns are also sometimes viewed as an indicator of the attractiveness of VET. This is indeed the case in countries where enrolment in vocational rather than a general programmes is a matter of student choice, subject to few or no constraints. In many countries, however, student choice is subject to various constraints. Half of the countries that participated in the 2022 Survey of Upper Secondary Completion Rates report that students’ choices are limited by their school performance (e.g. grades in lower secondary education). Performance in an external examination is a factor in nine countries and teacher or school recommendations matter in seven countries. Finally, in four countries the type of lower secondary education pursued limits the upper secondary options available to students. Only six countries with available information report that students’ choice of upper secondary programme was entirely unconstrained (see the Dashboard on Upper Secondary Education Systems).

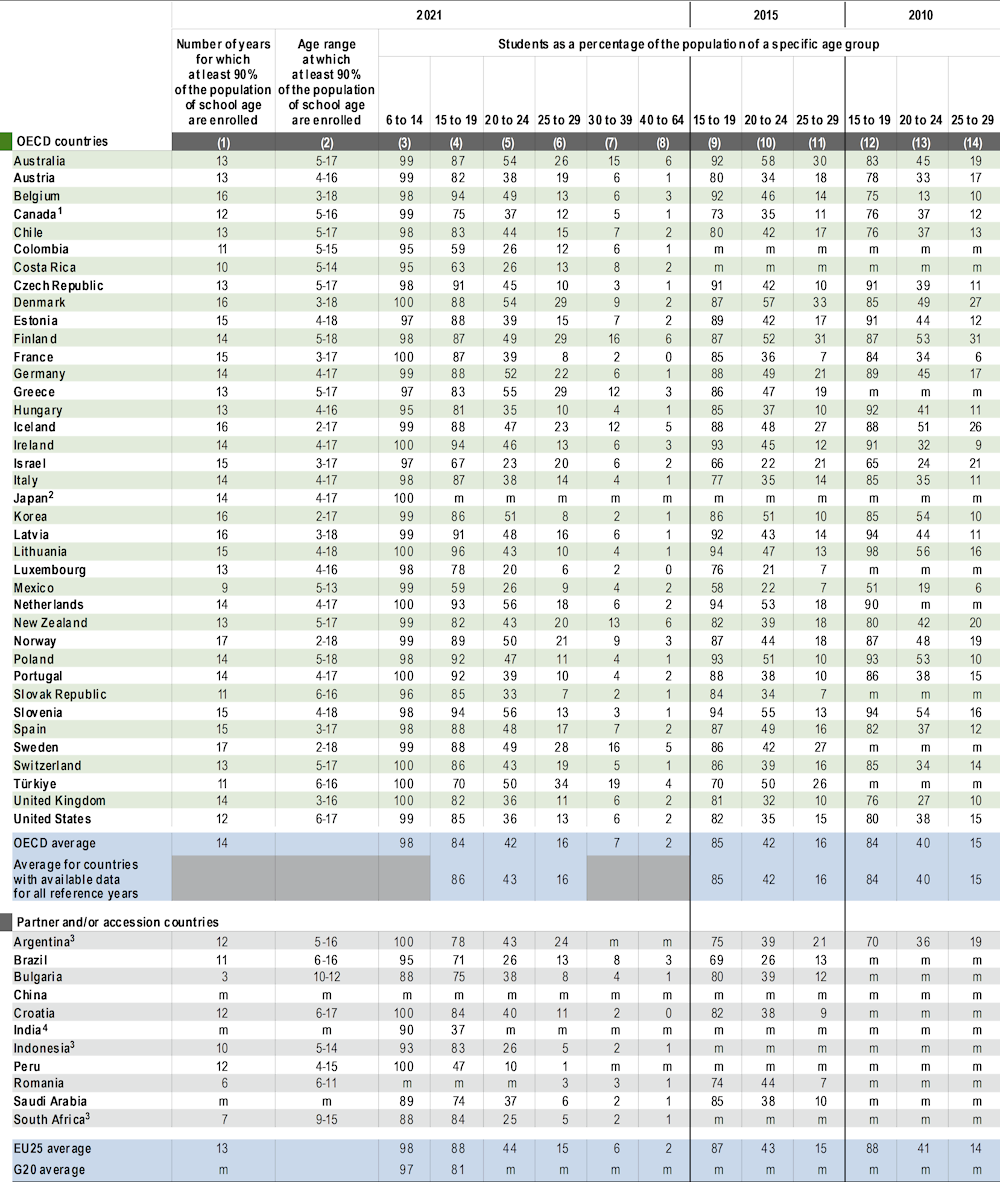

Participation rates of 15-19 year-olds

Enrolment patterns among 15-19 year-olds vary considerably across countries, both in terms of overall enrolment rates and the level at which students study. In many OECD countries nine out of ten teenagers in this age group are enrolled in education, and the average enrolment rate is 84%. However, at the lowest end of the range, there are countries where only about two-thirds of 15-19 year-olds are still in education. Information on the ages covered by compulsory education is complemented by data on the range of ages when at least 90% of the population are enrolled in education. In most OECD countries, enrolment rates exceed 90% up to the age of 17 or 18 but in ten countries the enrolment rate falls below 90% after 16, or even earlier (Table B1.1).

The level at which 15-19 year-olds are enrolled reflects the different structures of national education systems. Students in this age group might be pursuing lower secondary, upper secondary, post-secondary non-tertiary or tertiary education, although the majority are enrolled in upper secondary education. Enrolment in lower secondary education is also relatively common in Australia, Denmark, Estonia and Germany, where over one-quarter of 15-19 year-olds are studying at this level. In countries where upper secondary education is normally completed around age 17-18, participation in post-secondary non-tertiary or tertiary education can be common among this age group. At least one in five 15-19 year-olds are enrolled at those levels in Belgium, France, Greece, Korea, New Zealand and the United States (Table B1.1).

Data on enrolment rates across different age groups shed light on the role of VET in initial upper secondary education. These data complement information on attainment in Indicator A1 (see Box A1.1), which records the highest level of education individuals have completed, and therefore does not capture those who pursue VET but drop out, for example, or who complete it and then obtain a higher level qualification. Upper secondary enrolment among 15-19 year-olds is mostly in vocational programmes in 11 OECD countries. In these countries, VET is the main initial upper secondary education pathway. In contrast, the very small share of vocational upper secondary students in this age group in New Zealand reflect the fact that in these countries vocational education is delivered outside the initial schooling system. Students typically complete general upper secondary education and then might pursue a vocational programme at upper secondary level, as an alternative to post-secondary or tertiary education. Germany has a strong tradition of apprenticeships, and around one-third of 15-19 year-old upper secondary students pursue a vocational programme. At the same time, a considerable share of 20-24 year-olds in Germany are enrolled in vocational upper secondary (9%) or post-secondary non-tertiary (8%) programmes. The latter category includes apprenticeships for general upper secondary graduates. This shows that vocational programmes serve both teenagers and young adults (Table B1.1).

Box B1. explores the transition from lower to upper secondary level, analysing participation patterns in education around the age when students are typically expected to start upper secondary education.

Box B1.A. Above and beyond: Transitions in upper secondary education

While many OECD countries aim to ensure universal completion of upper secondary education, the transition into upper secondary education remains a challenge for some students. Countries achieve a smooth transition between lower and upper secondary by ensuring that a high share of students enter upper secondary at the expected transition age. Grade repetition at earlier stages might delay transitions and strict academic requirements may also be a barrier to entry.

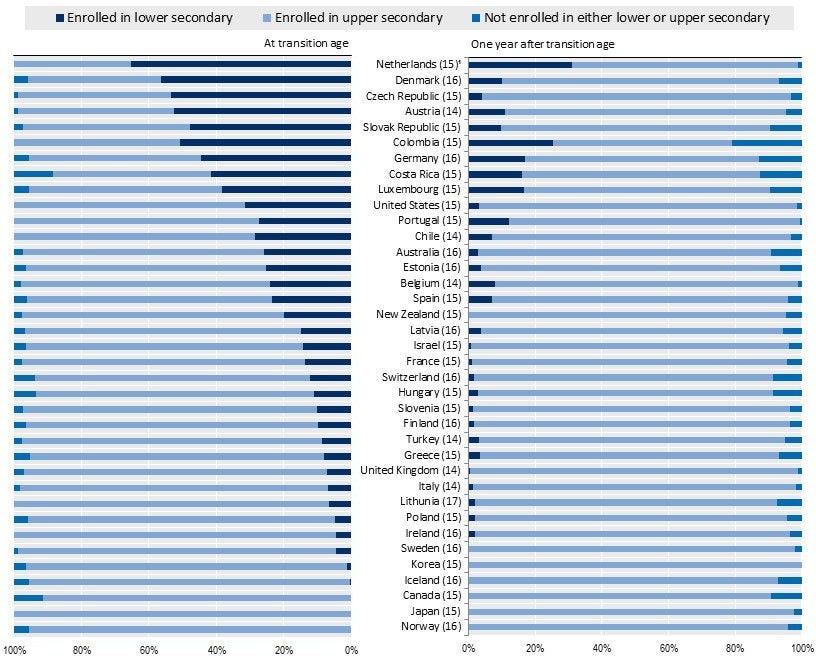

Figure B1.2 shows the enrolment rates in different levels of education at the theoretical age of transition for each OECD country and after one year. The theoretical age of transition refers to the age when students are typically expected to enter upper secondary education in the given country. Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Korea and Norway appear to have particularly smooth transitions, with at least 95% of students at the theoretical transition age enrolled in upper secondary education. The transition appears less smooth in Colombia, Costa Rica, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. In these countries over 15% of the cohort are still in lower education even one year after the expected transition age.

The reasons why students might not be transitioning to upper secondary education at the expected age can vary by country. In some places, this reflects the length of certain educational programmes, in particular programmes which in some countries have variable length that is not reflected in theoretical transition ages (e.g. Denmark, Flemish Community of Belgium, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands and Switzerland). Grade repetition is another potential driver in some countries: Colombia and Luxembourg for example have relatively high rates of repetition (Perico E Santos, 2023[5]).

Figure B1.2. Distribution of students by education level at the theoretical age of transition into upper secondary and after one year (2021)

Note: Enrolment rate by age is the percentage of people of a specific age who are enrolled in each type of education as a share of the total population of that age. The number in parentheses represents the theoretical age of transition into upper secondary education for each country. The left panel shows enrolment rates in lower secondary and upper secondary at the theoretical transition age, so the theoretical age for the first year of upper secondary education. The right panel shows enrolments in the relevant levels of education one year after the theoretical transition age, so the theoretical age for the second year of upper secondary education.

1. The typical age of transition is between 15 and 16.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of students enrolled in lower secondary education at transition age.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2023); Table B1.2 For more information see Source section and Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes, (OECD, 2023[1]).

Participation rates of 20-24 year-olds

Among 20-24 year-olds, tertiary education is the most common level being pursued. On average, 31% of young adults in this age group are enrolled in a programme at bachelor’s level or above, reaching over 40% in Greece, Korea, the Netherlands and Slovenia. Most of the enrolment is in bachelor’s level programmes (one-quarter of all 20-24 year-olds on average), with only 6% enrolled in master’s level programmes (which include long first degrees). Participation in doctoral programmes is negligible (below 1%) for this age group in all countries (Table B1.1).

Short-cycle tertiary programmes also play an important role in some countries in offering learning opportunities to adults, including young adults. In Canada 7% of 20-24 year-olds pursue studies at this level, often in colleges and with an occupational focus. In some countries, programmes at this level offer higher level technical skills, often to graduates of upper secondary education. In Chile 9% of those in this age group pursue two-year studies in technical training centres, in Spain the same share enrol in higher vocational programmes. The Republic of Türkiye has a particularly high short-cycle tertiary enrolment rate (16%), driven by recent reforms that have expanded open access courses at this level.

Young adults who pursue upper secondary education tend to do so in vocational programmes. Around two-thirds of upper secondary students aged 20-24 are in VET programmes (Table B1.1). In some countries nearly all upper secondary students in this age group are in a vocational programme: the share is over 95% in the Czech Republic, France, Ireland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Relatively high enrolment rates in upper secondary vocational programmes among 20-24 year-olds in some countries reflect the role of VET in adult education. This includes participation in second-chance programmes and other forms of adult education, such as those in Denmark, Finland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. In Australia and New Zealand upper secondary enrolment among 20-24 year-olds is also predominantly vocational. This reflects the fact that initial schooling is predominantly general as the main programme in these countries and students will pursue further VET qualifications upon the completion of upper secondary education (see Box A1.1 in Indicator A1).

The age of participants in vocational education and training

The average age of vocational students at different levels also reflects the function of programmes in different countries. For example, in Croatia, Colombia, Israel, Korea and Türkiye the average age of upper secondary VET students is 16 and in nearly half of OECD countries the average age is 18 or lower, reflecting that upper secondary programmes in these countries mostly serve teenagers. In many countries vocational upper secondary programmes serve both teenagers in initial education (Figure B1.) and adults seeking occupational training, and the average age of upper secondary VET students is higher, between 20 and 30. For example, in Finland and Norway, 45% of 15-19 year-olds in upper secondary education are in VET, but the mean age of students is 28 in Finland and 20 in Norway. In the Netherlands around half of 15-19 year-olds in upper secondary education are in VET and the average age of upper secondary VET students is 23. In a small number of countries few teenagers are enrolled in VET, leading to a high average age of upper secondary VET students. In Australia, Ireland and New Zealand, 16% or less of 15-19 year-olds in upper secondary education study VET as their main programme and the average age of students who pursue upper secondary level VET is 30 or above (Figure B1.3).

Post-secondary non-tertiary vocational programmes are part of higher vocational education in some countries, typically serving graduates of upper secondary vocational programmes. Examples include Finland, Norway and Sweden, where programmes at this level offer advanced, specialised vocational skills to upper secondary graduates, typically those from VET. In these countries participants are adults with a mean age of 42 in Finland, 36 in Norway and 35 in Sweden (Figure B1.3). In other countries, programmes at this level serve younger adults, including recent upper secondary graduates. In Germany programmes at this level include apprenticeships in second cycle programmes serving general upper secondary graduates and vocational programmes in the health and social sectors, serving general upper secondary graduates, and the average age of students is 23.

In Ireland and New Zealand upper secondary VET students are older on average than their peers in post-secondary non-tertiary education (Figure B1.3). The reason is that post-secondary programmes do not always build on upper secondary VET, but can be an alternative learning opportunity. In Ireland, post-secondary non-tertiary programmes include apprenticeships and post leaving certificate programmes (which serve graduates of general upper secondary education). Vocational programmes at upper secondary level are occupationally focused, with some concentrating on unemployed and marginalised adults. This is also the case in New Zealand. In addition, both upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary vocational programmes serve adults seeking to upskill, reskill or otherwise further their education and training.

In some countries, short-cycle tertiary programmes mostly serve recent upper secondary graduates, including Canada, France, Luxembourg, Portugal and Spain. In these countries the average age of students is 25 or below. In Austria, for example, this level includes a two-year programme that is the continuation of an upper secondary vocational programme (both offered at higher technical and vocational colleges). In Canada, short-cycle tertiary programmes play a key part in offering occupational training to young people, as upper secondary education is predominantly general. In Spain, programmes at this level offer advanced vocational training to both general and vocational upper secondary graduates. Short-cycle tertiary programmes can also serve a broader adult population, however. The OECD average age for students at this level is 27 and it is 30 or more in nine OECD countries. In these countries, programmes at this level include higher VET, such as higher VET in Sweden or vocational programmes for adults in New Zealand. Note, that in some countries with a high average age, the short-cycle tertiary sector is relatively small. For example, short-cycle tertiary students represent less than 1% of VET students in Germany, Switzerland and Poland (Table B1.3.). While higher vocational and professional programmes exist in several countries at bachelor’s and even master’s level, data are not included here, as internationally agreed definitions has not yet been developed for these levels (see Box B5.2, Indicator B5).

Types of upper secondary vocational education and training

Type of completion and access to tertiary education

It is important to ensure that vocational programmes, particularly those at upper secondary level, allow for progression to higher levels of education. This matters for the attractiveness of VET, as without progression opportunities bright young people will not consider VET as an option. It also matters for equity, as nobody should be locked out of further learning because of a choice made in initial schooling. It is also important for lifelong learning, as access to tertiary education can allow VET graduates to upskill or reskill during their careers. Countries have taken different approaches to structuring upper secondary education and VET, as well as associated progression opportunities.

Most upper secondary vocational students pursue a programme that leads to a qualification that allows for direct access to tertiary education (Figure B1.4). Within this broad category there are some nuances in access arrangements. In many countries VET graduates are eligible for any type of tertiary programme, subject to the same selection processes that apply to general upper secondary graduates. In some countries, however, there are distinct progression routes for VET graduates. For example access may only be possible to short-cycle tertiary programmes, which are typically viewed as part of higher VET. This is the case for example in Austria, where graduates of three year vocational programmes (in higher technical colleges) may progress to short-cycle tertiary programmes within the same institutions. Similarly, in Norway graduates of upper secondary VET have direct access to higher vocational programmes but not to universities. In some countries, VET graduates have access to some but not all bachelor’s level programmes. For example, in the Netherlands and Slovenia they have direct access to professional bachelor’s programmes, but not academic ones. Box B1.A provides further details on progression pathways from VET in different countries.

Most countries have at least one upper secondary vocational programme that leads to full level completion without direct access to tertiary education. This category refers to programmes that meet the requirements for graduates to be considered “upper secondary graduates” but the qualification obtained does not make them eligible for any type of tertiary education. Enrolment in such programmes is relatively high in countries with multiple vocational tracks at upper secondary level, such as Hungary, the Netherlands and Slovenia. In these countries, one vocational track has stronger emphasis on general skills and preparation for higher level studies, and gives direct access to tertiary education. Another track focuses on occupational preparation and its graduates do not have direct access to tertiary education.

Some OECD countries have vocational programmes that lead to partial completion of upper secondary education or are insufficient for level completion. These categories do not mean that students do not complete their studies or only complete some study at the level. Instead, these programmes lead to a recognised qualification but are not the final programme in a sequence of programmes. The category “insufficient for level completion” refers to programmes that are too short to meet the requirements for full or partial level completion (OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2015[6]). Programmes that do no lead to full level completion may play different functions, such as representing a stage within a multi-stage vocational pathway so that students typically progress to full level completion, or serving adults in search of occupational skills with limited general education content. Examples of a stage within a pathway include programmes in Denmark, the Flemish Community of Belgium and Germany. In Denmark, this category refers to the basic course in VET. It typically takes one year to complete, after which students enter the main course. In Germany programmes in this category serve lower secondary graduates who have not found an apprenticeship position with a company and pursue a year of basic vocational training, with a view to starting an apprenticeship later. In the Flemish Community of Belgium partial completion programmes include the second stage of technical or vocational secondary education which is connected to a third stage leading to full level completion. In contrast, programmes within this category in Estonia target adults and, unlike vocational programmes for youth at the same level, include limited general education and are deliberately focused on occupational skills.

When VET graduates seek to enter tertiary education, they may face some restrictions. As described above, some programmes do not yield direct access to tertiary education, while some only yield access to some types of tertiary education. There are some good arguments for limiting access of VET graduates to tertiary education – some programmes put less emphasis on general skills, so that their graduates are not well prepared to successfully pursue a tertiary programme. Some programmes may prepare students for applied tertiary programmes, but not so well for more theoretically oriented types of learning. At the same time, any restrictions need to be complemented by bridging opportunities to ensure students have effective pathways from VET to all types of higher levels of learning.

Countries have established different approaches to provide bridging pathways from restricted VET programmes, which are listed in Box B1.A. For example, although VET graduates in the Netherlands only have direct access to professional bachelor’s programmes, completing the first year of a professional bachelor’s programme yields access to the first year of studies in an academic programme at a university. In Germany and Switzerland, where VET gives access to bachelor’s programmes that are part of the professional sector (including some at master’s level in Germany), but not universities, graduates may pursue bridging programmes, but also have the option to pursue additional general education during their vocational programme to gain eligibility to universities. In Austria, Luxembourg, Norway and Spain, VET graduates have access to short-cycle tertiary education (higher vocational programmes) which would then give them access to bachelor’s level programmes. Sweden had a similar arrangement at the time of the data collection underpinning Box B1.A, until a recent reform gave VET graduates access to all types of tertiary education.

There are also bridging arrangements for programmes that do not yield direct access to tertiary education (Box B1.A). In most countries with such programmes, VET graduates have access to a bridging programme at upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary level. In a few countries this may involve entering another vocational programme which is not specifically designed as a bridging programme but may serve as one. For example, students in Switzerland who complete a two-year apprenticeship may transition into the second year of a three- or four-year apprenticeship, which in turn yields access to the professional sector of tertiary education.

Box B1. 1. Progression pathways from upper secondary VET

The first part of Table B1. A lists cases of VET programmes giving graduates only restricted access to tertiary education – either only to short-cycle tertiary education (ISCED level 5) or to some types of bachelor’s programmes (ISCED level 6). The second part lists countries that have programmes that do not yield direct access to tertiary education, distinguishing between those giving no access to higher levels or giving access to post-secondary non-tertiary programmes (ISCED level 4). For both parts, the table includes information on the kind of bridging opportunities that allow VET graduates to access a broader range of higher-level programmes.

Table B1. A. Access to higher levels of education: Restrictions and bridges for vocational graduates

|

Direct access to tertiary education with restrictions1 |

Access to ISCED 5 |

Access up to ISCED 6 with some restrictions |

Bridging opportunities, comments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

OECD |

|

||

|

Austria |

x |

Completion of ISCED 5 yields access to ISCED 6. |

|

|

Czech Republic |

x |

Small programme focused on performing arts. |

|

|

Germany |

x |

Additional general subjects during VET or bridging programme |

|

|

Iceland |

x |

Small programme focused on performing arts. |

|

|

Luxembourg |

x |

Completion of ISCED 5 yields access to ISCED 6. |

|

|

Netherlands |

x |

Completing the first year at a university of applied sciences gives access to university programmes. |

|

|

Norway |

x |

Bridging programme at ISCED 3; Completion of ISCED 5 yields access to ISCED 6. |

|

|

Slovenia |

x |

|

|

|

Spain |

x |

Completion of ISCED 5 yields access to ISCED 6. |

|

|

Sweden |

x |

Optional general subjects during VET or adult learning programmes. |

|

|

Switzerland |

x |

Additional general subjects during VET, bridging programme or stand-alone examination. |

|

|

No access to tertiary education2 |

No direct access to higher levels |

Access to ISCED 4 |

Bridging opportunities, comments |

|

OECD |

|

|

|

|

Czech Republic |

x |

Bridging programme at ISCED 3 |

|

|

Denmark |

x |

Possibility to complete VET together with a specific course (EUX), which provides general study competences for higher education. |

|

|

Flemish Comm. (Belgium) |

x |

Bridging programme at ISCED 4 (3rd year of the 3rd stage of VET) |

|

|

France |

x |

Possibility to access an ISCED 3 programme with direct access to tertiary education |

|

|

French Comm. (Belgium) |

x |

Bridging programme at ISCED 4 (3rd year of the 3rd stage of VET) |

|

|

Germany |

x |

Bridging programme at ISCED 4 |

|

|

Hungary |

x |

Bridging programme at ISCED 3 |

|

|

Iceland |

x |

Possibility to transition to a general upper secondary programme during VET. |

|

|

Italy |

x |

Possibility to access an ISCED 3 programme with direct access to tertiary education |

|

|

Netherlands |

x |

Possibility to access an ISCED 3 programme with direct access to tertiary education |

|

|

Poland |

x |

Bridging programme at ISCED 3 |

|

|

Slovak Republic |

x |

Bridging programme at ISCED 4 |

|

|

Slovenia |

x |

Bridging programme at ISCED 3 |

|

|

Spain |

x |

Possibility to access an ISCED 3 programme with direct access to tertiary education |

|

|

Switzerland |

x |

Possibility to access an ISCED 3 programme with direct access to tertiary education |

|

1 This table highlights restrictions on access to tertiary education that apply to VET graduates, but not general upper secondary graduates. Access up to ISCED 6 involves access to ISCED 5. The restrictions described apply to all VET students enrolled in programmes that yield access to tertiary education. Additional admission requirements may apply, similarly to those applied for general upper secondary graduates.

2 This table focuses on ISCED 353 programmes only, recognising that countries in this table may also offer ISCED 354 programmes. It excludes countries where such programmes enrol less than 5% of upper secondary VET students in programmes that lead to full level completion. The table distinguishes between "bridging programmes" that are designed to lead to a qualification that gives eligibility to tertiary education, and "Possibility to access an ISCED 3 programmes with direct access to tertiary education", which serve a broader target group than ISCED 353 completers.”

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2023), ISCED mappings. For more information see Source section and Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes, (OECD, 2023[1]).

The use of work-based learning

Including an element of work-based learning in vocational programmes has multiple benefits. Workplaces are powerful environments for the acquisition of both technical and soft skills. Students can learn from experienced colleagues, using the equipment and technology that is currently used in their field. Soft skills like conflict management are easier to develop in real life contexts than in classroom settings. Delivering practical training in work environments can reduce the cost of training in schools, as equipment is often costly and becomes quickly obsolete. Similarly, including a strong element of work-based learning in VET can help tackle teacher shortages if students are learning from experienced skilled workers in companies. Finally, work-based learning creates a link between schools and the world of work, as well as between students and potential employers (OECD, 2018[7]).

Despite these compelling benefits, countries vary widely in the use of work-based learning in vocational programmes (Figure B1.5). In some countries work-based learning is extensively used, with 90% or more of students pursuing combined school- and work-based programmes. These are largely apprenticeship programmes (e.g. Denmark, Germany, Hungary and Switzerland). School-based and combined school- and work-based programmes co-exist in several countries. In some of them this reflects the existence of alternative routes to the same qualification. In France, for example, upper secondary vocational qualifications may be acquired either through apprenticeships or through a school-based route with a smaller work-based learning component (accounting for 17-20% of programme duration, depending on the programme). In some other countries, apprenticeships and school-based programmes lead to different qualifications. In Austria, for example, upper secondary vocational programmes include both apprenticeships and programmes in higher technical and vocational colleges. In many countries only a small share of vocational students are enrolled in combined school- and work-based programmes: in 12 countries, less than one in four students pursue such programmes. However, programmes that are considered school-based may include shorter forms of work-based learning, accounting for less than 25% of the programme’s duration (Box B1.2).

Box B1.2. Types of work-based learning in vocational programmes

The ISCED mappings were updated in 2022 to provide further details on the type of work-based learning used in each vocational programme. This allows for a more fine-grained picture of how work-based learning is being used, in particular separately identifying apprenticeships, as well as short internships which are excluded from the definition of “combined school- and work-based programmes”. The following categories are proposed:

apprenticeship: work-based learning is mandatory, accounts for at least 50% of the curriculum and is paid

long internship: work-based learning is mandatory and accounts for 25% to 49% of the curriculum

short internship: work-based learning is mandatory and accounts for less than 25% of the curriculum

optional work-based learning: work-based learning is an optional part of the curriculum

no work-based learning as part of the curriculum.

Apprenticeships are the dominant form of upper secondary VET in Denmark, Germany and Switzerland, while in Austria, France and Iceland apprenticeships are available alongside school-based programmes, which include a short internship. In Sweden apprenticeships enrol a relatively small share of students. Short internships are common in several countries, including Costa Rica, Lithuania, Spain, Slovenia and Sweden.

Definitions

The data in this indicator cover formal education programmes that represent at least the equivalent of one semester (or half of a school/academic year) of full-time study and take place entirely in educational institutions or are delivered as combined school- and work-based programmes.

General education programmes are designed to develop learners’ general knowledge, skills and competencies, often to prepare them for other general or vocational education programmes at the same or a higher education level. General education does not prepare people for employment in a particular occupation, trade, or class of occupations or trades.

Vocational education and training (VET) programmes prepare participants for direct entry into specific occupations without further training. Successful completion of such programmes leads to a vocational or technical qualification that is relevant to the labour market.

Full completion (of ISCED level 3) without direct access to first tertiary programmes at ISCED level 5, 6 or 7: programmes with duration of at least 2 years at ISCED level 3 and that end after at least 11 years cumulative study since the beginning of ISCED level 1. These programmes may be terminal (i.e. not giving direct access to higher levels of education) or give direct access to ISCED level 4 only.

Full completion (of ISCED level 3) with direct access to first tertiary programmes at ISCED level 5, 6 or 7: any programmes that give direct access to first tertiary programmes at ISCED level

Partial level completion refers to programmes representing at least 2 years at ISCED level 3 and a cumulative duration of at least 11 years since the beginning of ISCED level 1, and which are part of a sequence of programmes at ISCED level 3 but are not the last programme in the sequence.

Insufficient for level completion refers to programmes that do not meet the duration requirements for partial or full level completion and therefore result in an educational attainment at the level below the level of the programme. This category includes short, terminal programmes (or a sequence of programmes) with a duration of less than 2 years at ISCED level 3 or which end after less than 11 years of cumulative duration since the beginning of ISCED level 1.

Methodology

Except where otherwise noted, figures are based on head counts, because it is difficult for some countries to quantify part‑time study. Net enrolment rates are calculated by dividing the number of students of a particular age group enrolled in all levels of education by the size of the population of that age group. While enrolment and population figures refer to the same period in most cases, mismatches may occur due to data availability in some countries, resulting in enrolment rates exceeding 100%.

For more information see the OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics (OECD, 2018[8])and Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes (OECD, 2023[1]).

Source

Data refer to the 2020/21 academic year and are based on the UNESCO-UIS/OECD/Eurostat data collection on education statistics administered by the OECD in 2022. Data for some countries may have a different reference year. For more information see Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes (OECD, 2023[1]).

References

[4] CEDEFOP (2022), Work-Based Learning and the Green Transition, Publications Office of the European Union, http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/69991.

[1] OECD (2023), Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d7f76adc-en.

[3] OECD (2022), Pathways to Professions: Understanding Higher Vocational and Professional Tertiary Education Systems, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a81152f4-en.

[8] OECD (2018), OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018: Concepts, Standards, Definitions and Classifications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264304444-en.

[7] OECD (2018), Seven Questions about Apprenticeships: Answers from International Experience, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264306486-en.

[6] OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2015), ISCED 2011 Operational Manual: Guidelines for Classifying National Education Programmes and Related Qualifications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264228368-en.

[5] Perico E Santos, A. (2023), “Managing student transitions into upper secondary pathways”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 289, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/663d6f7b-en.

[2] Vandeweyer, M. and A. Verhagen (2020), “The changing labour market for graduates from medium-level vocational education and training”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 244, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/503bcecb-en.

Indicator B1 Tables

Tables Indicator B1. Who participates in education?

|

Table B1.1 |

Enrolment rates by age group (2010, 2015 and 2021) |

|

Table B1.2 |

Enrolment rates of 15-19 year-olds and 20-24 year-olds, by level of education (2021) |

|

Table B1.3 |

Profile of students enrolled in vocational programmes (2021) |

Cut-off date for the data: 15 June 2023. Any updates on data can be found on line at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en. More breakdowns can also be found at http://stats.oecd.org/, Education at a Glance Database.

Table B1.1. Enrolment rates by age group (2010, 2015 and 2021)

Students in full-time and part-time programmes in both public and private institutions

Note: See StatLink and Box B1.3 for the notes related to this Table.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2023). For more information see Source section and Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes, (OECD, 2023[1]).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table B1.2. Enrolment rates of 15-19 year-olds and 20-24 year-olds, by level of education (2021)

Students enrolled in full-time and part-time programmes in both public and private institutions

Note: See StatLink and Box B1.3 for the notes related to this Table.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2023). For more information see Source section and Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes, (OECD, 2023[1]).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table B1.3. Profile of students enrolled in vocational programmes (2021)

Note: See StatLink and Box B1.3 for the notes related to this Table.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2023). For more information see Source section and Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes, (OECD, 2023[1]).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Box B1.3. Notes for Indicator B1 tables

Table B1.1. Enrolment rates by age group (2010, 2015 and 2021)

1. Excludes post-secondary non-tertiary education.

2. Breakdown by age not available after 15 years old.

3. Year of reference differs from 2021: 2020 for Argentina and South Africa; 2018 for Indonesia.

4. Excludes students enrolled at tertiary levels.

Table B1.2. Enrolment rates of 15-19 year-olds and 20-24 year-olds, by level of education (2021)

Additional columns showing more detail on enrolment rates for lower secondary and below and master's and doctoral levels are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below).

1. Breakdown by age not available after 15 years old.

2. Year of reference differs from 2021: 2020 for Argentina and South Africa; 2018 for Indonesia.

Table B1.3. Profile of students enrolled in vocational programmes (2021)

Additional columns showing average ages, breakdowns by type of programme and comparative data for 2013 are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below). All vocational students in columns 2, 6, 9, 13 refer to students enrolled in lower secondary, upper secondary, post-secondary non-tertiary and short-cycle tertiary programmes.

1. Short-cycle tertiary includes both general and vocational programmes.

2. Year of reference differs from 2021: 2020 for Argentina and South Africa; 2018 for Indonesia.

For more information see Definitions, Methodology and Source sections and Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes (OECD, 2023[1]).

Data and more breakdowns are available in the Education at a Glance Database (http://stats.oecd.org/).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.