[13] Baum, S., J. Ma and K. Payea (2013), Education Pays 2013: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society, The College Board, NewYork, https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/education-pays-2013-full-report.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2017).

[44] Berlinski, S., S. Galiani and P. Mc Ewan (2011), “Preschool and Maternal Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 59/2, pp. 313-344, http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/657124.

[52] Blanden, J. et al. (2012), “Measuring the earnings returns to lifelong learning in the UK”, Economics of Education Review, Vol. 31/4, pp. 501-514, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.12.009.

[20] Cabinet Office (2012), Heisei 24-nendo Kodomo, Kosodate Vision ni Kakaru Tenken, Hyouka no Tameno Shihyou Chousa Houkokusho [FY 2012 Report Indicator Assessment on Evaluation of Children and a Vision of Childcare], www8.cao.go.jp/shoushi/shoushika/research/cyousa24/shihyo/index_pdf.html.

[58] Cedefop (2014), “Policy handbook: Access to and participation in continuous vocational education and training (CVET) in Europe”, Cedefop working paper, No. 25, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/6125_en.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[46] Chapman, B. and C. Ryan (2005), “The access implications of income-contingent charges for higher education: lessons from Australia”, Economics of Education Review, Vol. 24/5, pp. 491-512, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.08.009.

[45] Chapman, B. (2016), “Income contingent loans in higher education financing”, IZA World of Labor, http://dx.doi.org/10.15185/izawol.227.

[53] Coelli, M. and D. Tabasso (2015), “Where Are the Returns to Lifelong Learning?”, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 9509, IZA (Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor [Institute of Labor Economics]), http://ftp.iza.org/dp9509.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2017).

[11] Council of the European Union (2011), “Council Resolution on a renewed European agenda for adult learning”, Official Journal of the European Union.

[54] Crichton, S. and S. Dixon (2011), Labour market returns to further education for working adults, New Zealand Department of Labour, Wellington, www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/80898/labour-market-returns-to-further-education-for-working-adults (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[42] Del Boca, D. (2015), “Child Care Arrangements and Labor Supply”, Working Papers, No. 88074, https://ideas.repec.org/p/idb/brikps/88074.html (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[47] Del Rey, E. and I. Schiopu (2015), Student debt in selected countries, European Expert Network on Economics of Education (EENEE), Munich, www.esadeknowledge.com/view/student-debt-in-selected-countries-168540 (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[36] European Commission (2016), Structural higher education reform: design and evaluation: Synthesis report, European Commission, Brussels, http://dx.doi.org/10.2766/79662.

[41] European Commission (2014), Proposal for key principles of a Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care: : Report of the Working Group on Early Childhood Education and Care under the auspices of the European Commission, European Commision, Brussels, http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/repository/education/policy/strategic-framework/archive/documents/ecec-quality-framework_en.pdf.

[25] Gary-Bobo, R. and A. Trannoy (2015), “Optimal student loans and graduate tax under moral hazard and adverse selection”, The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 46/3, pp. 546-576, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1756-2171.12097.

[43] Gathmann, C. and B. Sass (2012), “Taxing Childcare: Effects on Family Labor Supply and Children”, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 6440, https://ideas.repec.org/p/iza/izadps/dp6440.html (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[28] Genda, Y. (2005), Hataraku Kajyo (The Over-Meanings of Work), NTT Publishing.

[24] Hartlaub, V. and T. Schneider (2012), “Educational Choice and Risk Aversion: How Important Is Structural vs. Individual Risk Aversion?”, SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research, No. 433, https://ideas.repec.org/p/diw/diwsop/diw_sp433.html (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[17] Heckman, J. (2011), “The Value of Early Childhood Education”, American Educator, Vol. 351, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ920516.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[38] Horwood, J. and G. McLeod (2017), Outcome of the Early Childhood Education in the Christchurch Health and Development Study (CHDS) cohort, New Zealand Ministry of Education, Wellington, www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/181425/Outcome-of-Early-Childhood-Education-in-the-CHDS-Cohort.pdf.

[59] Hyde, M. and C. Phillipson (2014), How can lifelong learning, including continuous training within the labour market, be enabled and who will pay for this? Looking forward to 2025 and 2040 how might this evolve?, Government Office for Science, London, http://catalogue.iugm.qc.ca/GEIDEFile/33775.pdf?Archive=108392492657&File=33775_pdf (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[56] International Labour Office (ILO) (2010), A Skilled Workforce for Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth: A G20 Training Strategy, ILO, Geneva, www.ilo.org/skills/pubs/WCMS_151966/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[23] Jacobs, B. and S. van Wijnbergen (2007), “Capital-Market Failure, Adverse Selection, and Equity Financing of Higher Education”, FinanzArchiv / Public Finance Analysis, Vol. 63, pp. 1-32, https://doi.org/10.1628/001522107X186683.

[51] Jenkins, A. et al. (2003), “The determinants and labour market effects of lifelong learning”, Applied Economics, Vol. 35/16, pp. 1711-1721, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0003684032000155445.

[55] Jenkins, A. (2004), “Women, Lifelong Learning and Employment”, CEE Discussion Papers, No. 0039, Centre for the Economics of Education, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, https://ideas.repec.org/p/cep/ceedps/0039.html (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[27] Kuroda, S. (2010), “Do Japanese Work Shorter Hours than before? Measuring trends in market work and leisure using 1976–2006 Japanese time-use survey”, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, Vol. 24/4, pp. 481-502, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2010.05.001.

[5] ManpowerGroup (2015), 2015 Talent Shortage Survey, www.manpowergroup.com/wps/wcm/connect/db23c560-08b6-485f-9bf6-f5f38a43c76a/2015_Talent_Shortage_Survey_US-lo_res.pdf?MOD=AJPERES (accessed on 25 July 2017).

[57] McNair, S. (2012), “National adult learner survey 2010”, Research Paper, No. 63, BIS, London, www.bis.gov.uk (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[40] Melhuish, E. et al. (2015), A review of research on the effects of early childhood education and care (ECEC) on child development, The Care Project, Raleigh, NC, http://ecec-care.org/fileadmin/careproject/Publications/reports/CARE_WP4_D4__1_review_of_effects_of_ecec.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2017).

[1] MEXT (2016), OECD-Japan Education Policy Review: Country Background Report, MEXT, Tokyo.

[39] Mitchell, L. et al. (2008), Outcomes of early childhood education : literature review, New Zealand Council for Educational Research, www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/outcomes-early-childhood-education-literature-review (accessed on 25 July 2017).

[49] Murphy, R., J. Scott-Clayton and G. Wyness (2017), “The End of Free College in England: Implications for Quality, Enrolments, and Equity”, NBER Working Paper, No. 23888, NBER, www.nber.org/papers/w23888.pdf (accessed on 09 October 2017).

[26] Nagamachi, R. and K. Yugami (2015), “The Consistency of Japan fs Statistics on Working Hours, and an Analysis of Household Working Hours”, Public Policy Review, Vol. 11/4, https://ideas.repec.org/a/mof/journl/ppr030f.html (accessed on 25 July 2017), pp. 623-658.

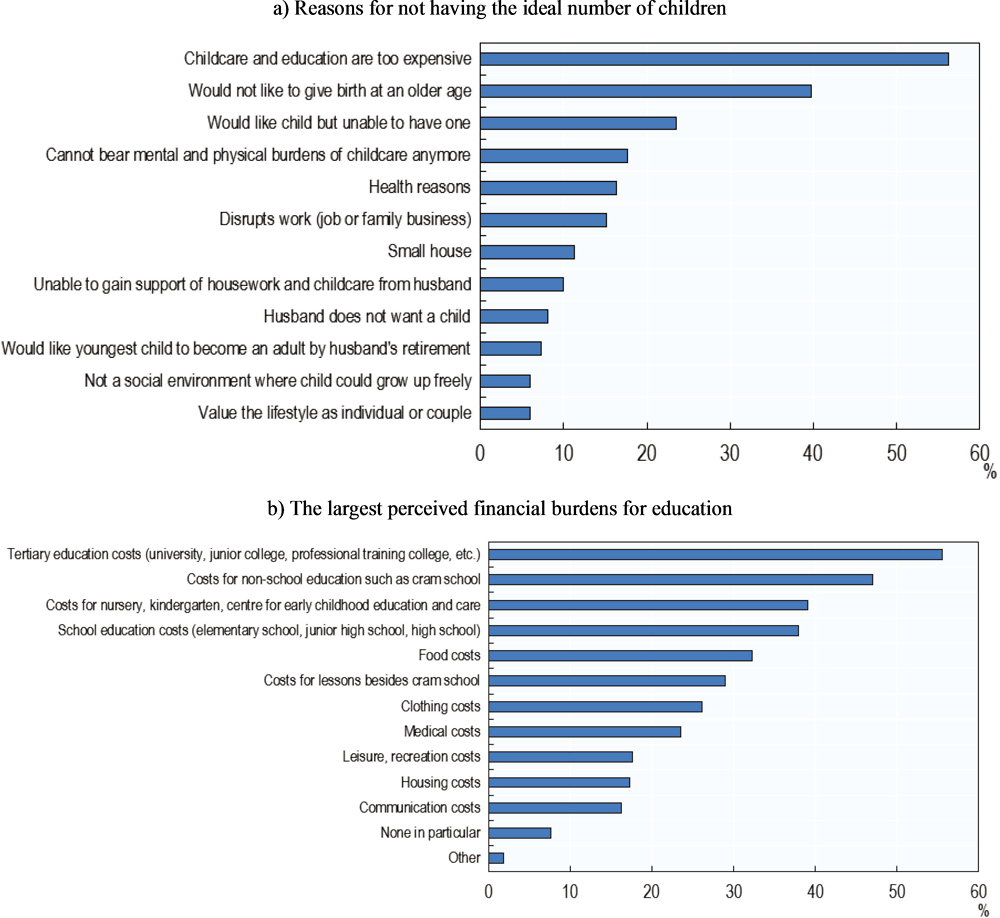

[19] National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (2016), The 15th Japanese National Fertility Survey: National Survey on Marriage and Childbirth, National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, www.ipss.go.jp/ps-doukou/j/doukou15/doukou15_gaiyo.asp.

[48] New Zealand Ministry of Education (2016), Student Loan Scheme: Annual Report 2015/16, New Zealand Ministry of Education, Wellington, www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/180709/Student-Loan-Scheme-2016-131216.pdf.

[2] OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Japan 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-jpn-2017-en.

[3] OECD (2017), Labour Force Statistics: Population projections, OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00538-en.

[8] OECD (2017), Employment rate (indicator), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1de68a9b-en.

[10] OECD (2017), OECD Skills Outlook 2017: Skills and Global Value Chains, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273351-en.

[18] OECD (2017), PF3.2 Enrolment in childcare and pre-school, OECD Family Database, www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 20 July 2017).

[30] OECD (2017), OECD Survey of Adult Skills (2012, 2015), OECD Survey of Adult Skills (database), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/ (accessed on 13 September 2017).

[32] OECD (2017), Poverty rate (indicator), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/0fe1315d-en.

[4] OECD (2016), OECD Employment Outlook 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2016-en.

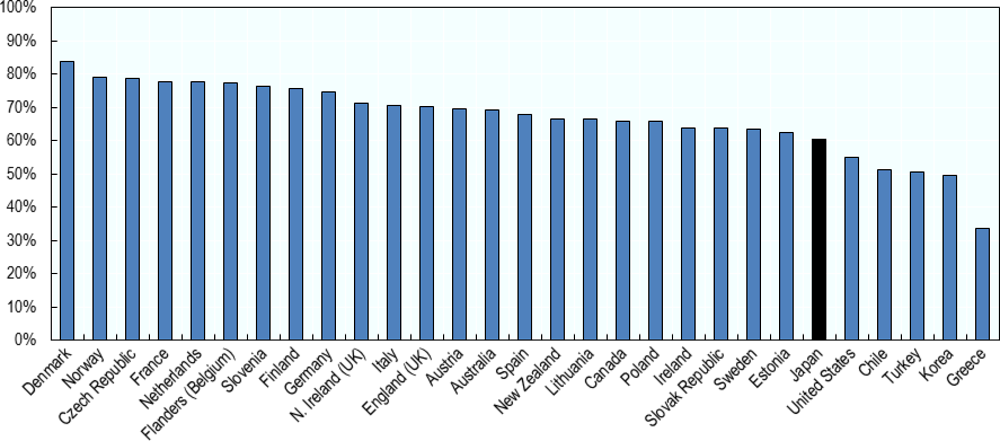

[7] OECD (2016), Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.

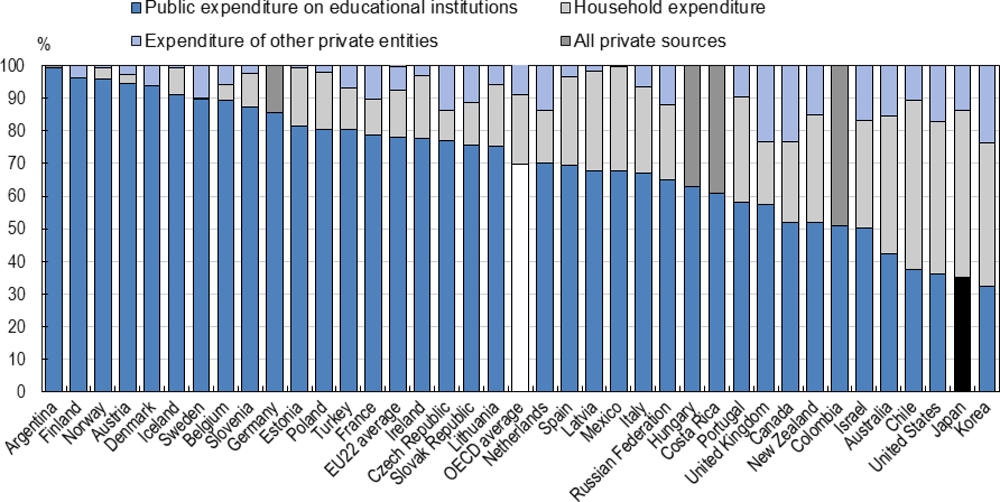

[12] OECD (2016), Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2016-en.

[14] OECD (2016), Society at a Glance 2016: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264261488-en.

[6] OECD (2013), OECD Skills Outlook 2013: First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204256-en.

[9] OECD (2012), Survey of Adult Skills Database, http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis/#d.en.408927.

[16] OECD (2011), “Does Participation in Pre-Primary Education Translate into Better Learning Outcomes at School?”, PISA in Focus, Vol. 1, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k9h362tpvxp-en (accessed on 18 October 2017).

[37] OECD (2011), Starting Strong III: A Quality Toolbox for Early Childhood Education and Care, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264123564-en.

[33] OECD (2006), Education at a Glance 2006: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2006-en.

[21] Research Institute for Higher Education (2014), Statistics of Japanese Higher Education, Research Institute for Higher Education, Hiroshima, http://rihe.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/en/statistics/synthesis/.

[29] Rubenson, K. (2006), “The Nordic model of Lifelong Learning”, Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, Vol. 36/3, pp. 327-341, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057920600872472.

[22] Santiago, P. et al. (2008), Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264046535-en.

[34] Tight, M. (2013), “Institutional churn: institutional change in United Kingdom higher education”, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, Vol. 35/1, pp. 11-20, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2012.727700.

[50] UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2016), 3rd Global Report On Adult Learning And Education: The Impact of Adult Learning and Education on Health and Well-Being; Employment and the Labour Market; and Social, Civic and Community Life, UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, Hamburg, http://uil.unesco.org/system/files/grale-3.pdf.

[31] UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2009), Global Report On Adult Learning And Education, UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, Hamburg, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001864/186431e.pdf.

[15] Usher, A. (2006), Grants for students: what they do, why they work, Educational Policy Institute, Toronto, ON.

[35] Välimaa, J., H. Aittola and J. Ursin (2014), “University Mergers in Finland: Mediating Global Competition”, New Directions for Higher Education, Vol. 2014/168, pp. 41-53, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/he.20112.