This chapter highlights the opportunities to embed stakeholder participation at the local level in Jordan. It analyses current efforts from sub-national authorities to better inform, consult and engage stakeholders across the needs assessment process. It also identifies a number of implications that need to be tackled to successfully grasp the potential benefits of stakeholder participation in Jordan.

Engaging Citizens in Jordan’s Local Government Needs Assessment Process

Chapter 4. Stakeholder Participation in the Needs Assessment Process

Abstract

With the adoption of the 2015 Municipalities and Decentralization laws in Jordan, the Government has set a priority to empower local communities in the definition of policy and budgetary priorities across the 12 Governorates. Notably, the creation of Elected Councils has advanced efforts to bring public institutions closer to the public. More importantly, the reform has furthered the opening of the government by placing citizens at the heart of policies and services through a bottom-up approach to develop local plans.

Indeed, stakeholder participation allows governments to bridge the divide with citizens, and is at the core of responsive policy-making and service delivery. The OECD defines stakeholder participation as “all the ways in which stakeholders can be involved in the policy cycle and in service design and delivery (OECD, 2017a).” The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (2017), furthermore, argues that granting all stakeholders equal and fair opportunities to be engaged are key elements of effective open government reforms.

As part of its framework of analysis, the OECD ladder of participation model distinguishes between three levels of stakeholder participation, namely information, consultation and engagement (OECD, 2017):

Information: refers to the one-way relationship in which public organisations produce and share information for the general public, which cover both “reactive” measures responding to citizens’ information demands and “proactive” measures to disclose information and publish open data sets.

Consultation: refers to the two-way relationship in which citizens provide feedback to the government, where public institutions still define the issues for consultation, set the questions and manage the consultative process.

Engagement: refers to the provision of opportunities for stakeholders, as well as adequate resources (e.g. information, data and digital tools), to collaborate with public institutions throughout the policy-making cycle (OECD, 2016). It may include elements of co-decision or co-production.

Embedding stakeholder participation in the way local policies and services are designed in Jordan is all the more important against a backdrop of declining trust in public institutions. In fact, levels of trust in government are at their lowest, having suffered a steep decline from 73% in 2011 to 38% in 2018 (Arab Barometer, 2019). As noted in Chapter 3, a perception survey identified that only 10% of the population feel informed about the decentralization process, while 57% remain unaware of the new roles of Governorate and Municipal Councils and available opportunities to participate in the needs assessment process (International Republic Institute, 2018). OECD interviews with representatives from local government and civil society organizations (CSOs) also highlight room for improvement to increase opportunities for engagement and awareness raising.

The following chapter therefore provides an assessment of and recommendations for Jordan to embed stakeholder participation in the needs assessment process effectively. It examines the impact of current practices of Local, Municipal and Governorate authorities to consult and engage stakeholders in the needs assessment process.

Embedding stakeholder participation at the local level in Jordan

As the requirements on local governments to implement the decentralization reforms increase, so does the imperative to bridge the divide with citizens. In this respect, embedding participation at the local level acts as a virtuous circle by involving the public more deeply in policy choices and thereby reinforcing trust (OECD, 2016). Broadly, the aim of the decentralization reform in Jordan is to expand engagement efforts with citizens through the needs cycle, showcase impact, help ensure development plans reflect community needs more accurately and ultimately build trust.

Similar to most OECD countries, there is a stark difference between trust at the national and local level in Jordan, where citizens have greater confidence in Municipal Governments (52%) and Governorate Councils (44%) than in the Parliament (13%)1 (International Republican Institute, 2018). Indeed, the relatively higher levels of trust at the sub-national level in Jordan present an opportunity to engage actively with communities, and in turn contribute to better public services.

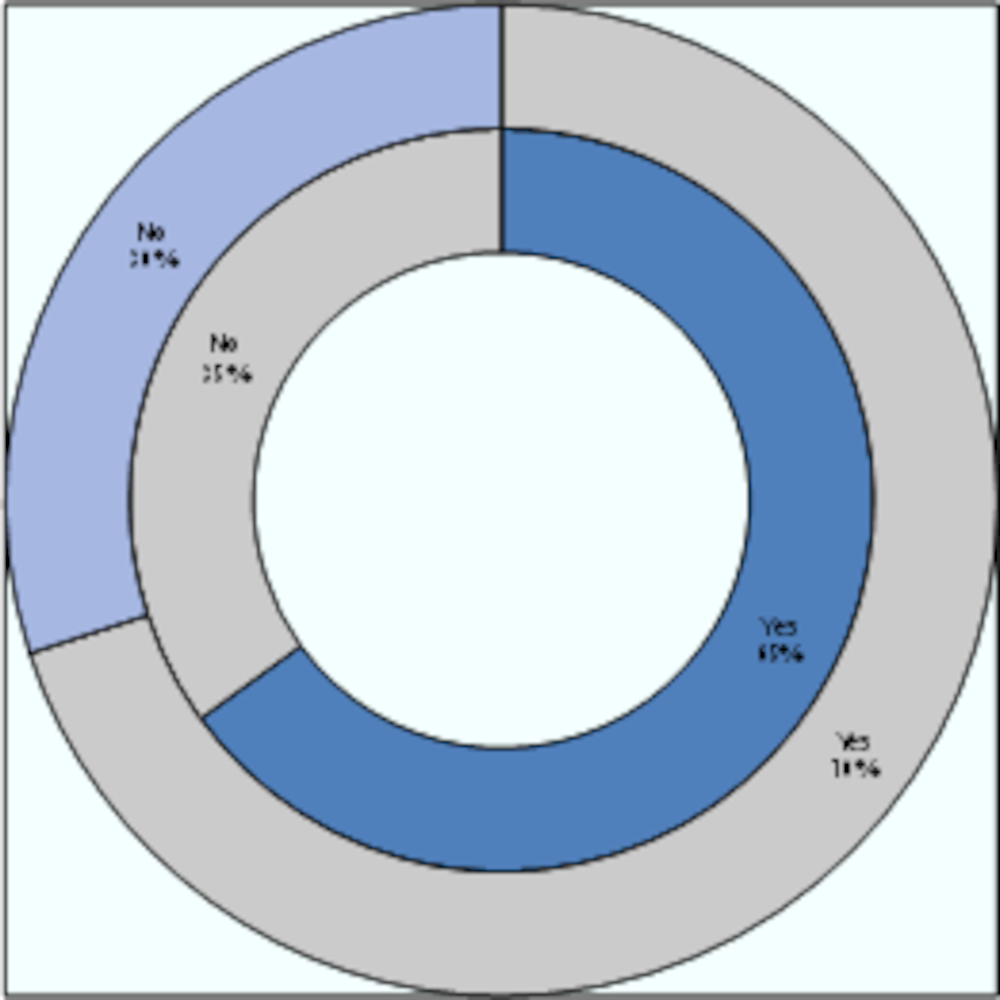

While trust levels at the local level remain higher than those at the national level, there remains, however, room for improvement. According to OECD data, the majority of public officials (65%) identified the lack of trust between the government and citizens as a challenge to increasing their involvement in the needs assessment process. Interestingly, the “lack of trust between government, citizens and CSOs” was also the top challenge selected by civil society (70%) (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Percentage of sub-national authorities and CSOs selecting “lack of trust” as a key challenge in the needs assessment process

Note: The inner circle reflects the responses from sub-national authorities and the outer circle those from CSOs.

Source: OECD (2019) Questionnaire for Civil Society Organizations & sub-national authorities: Stakeholder participation in Jordan’s needs assessment process.

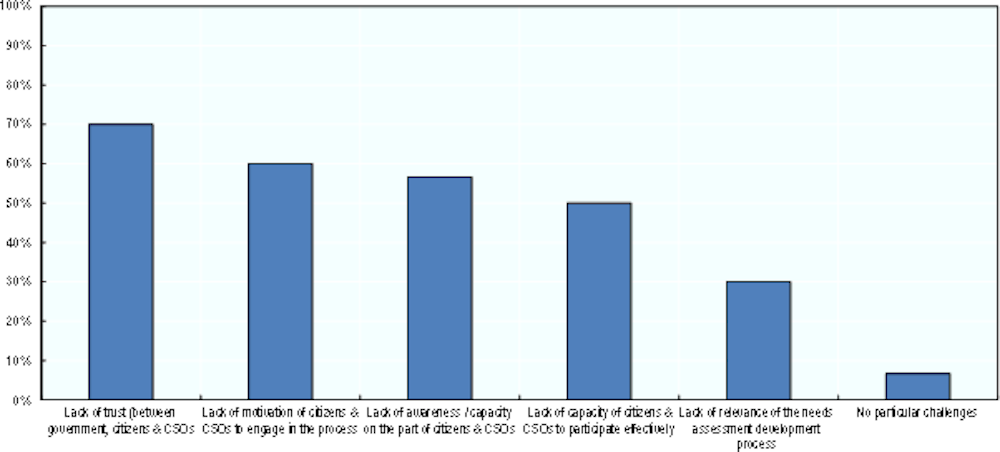

In addition, scepticism remains among some CSOs as to whether local development plans will meet citizens’ needs and expectations. A majority of civil society responding to the OECD survey emphasized the lack of trust (70%) and motivation (60%) as the main drivers of low participation in the collection of needs (See Figure 4.2). In particular, concerns remain in regards to the highly bureaucratic nature of this bottom-up process and the need to still rely on informal relationships to advocate for specific initiatives (Mahadin et al., 2018). Indeed, implementation efforts around the decentralization reform have brought to light the need for local authorities to establish a meaningful partnership with citizens, civil society and the private sector.

Figure 4.2. Main challenges to engage stakeholders in the needs assessment process

Source: OECD (2019), Questionnaire for Civil Society: Stakeholder participation in Jordan’s needs assessment process.

Recognizing these challenges, the Jordanian Government is also prioritizing stakeholder participation at the local level, acknowledging it as an important pillar of its national vision. One of the objectives of the Government Renaissance Plan (2019 – 2020), for example, is to promote the participation of local communities to identify development priorities and ensure their positive reflection on the quality of public services. The Renaissance Plan also recognizes the need to systematically integrate youth in this process. In addition to the 2015 Decentralization laws, commitments toward promoting the engagement of stakeholders as part of this reform were also undertaken through Jordan’s 3rd and 4th OGP NAPs.

In efforts to take stock and discuss the country’s progress, the Government also conducted a series of consultations – as part of the National Dialogue – on the political reform of decentralization with stakeholders from civil society, academia and unions. This platform contributed to the drafting of a new local administration law, which seeks to revamp decentralization efforts by granting new powers and procedural requirements for Local, Executive and Governorate Councils.

While local authorities are progressively opening up, there is yet room to strengthen their relationship with the public and embed participation in the machinery of sub-national administrations. The following sections will review critical determinants for current practices by the three levels of government in Jordan to consult and engage stakeholders throughout the needs assessment process effectively.

Promoting stakeholder participation throughout the needs assessment process

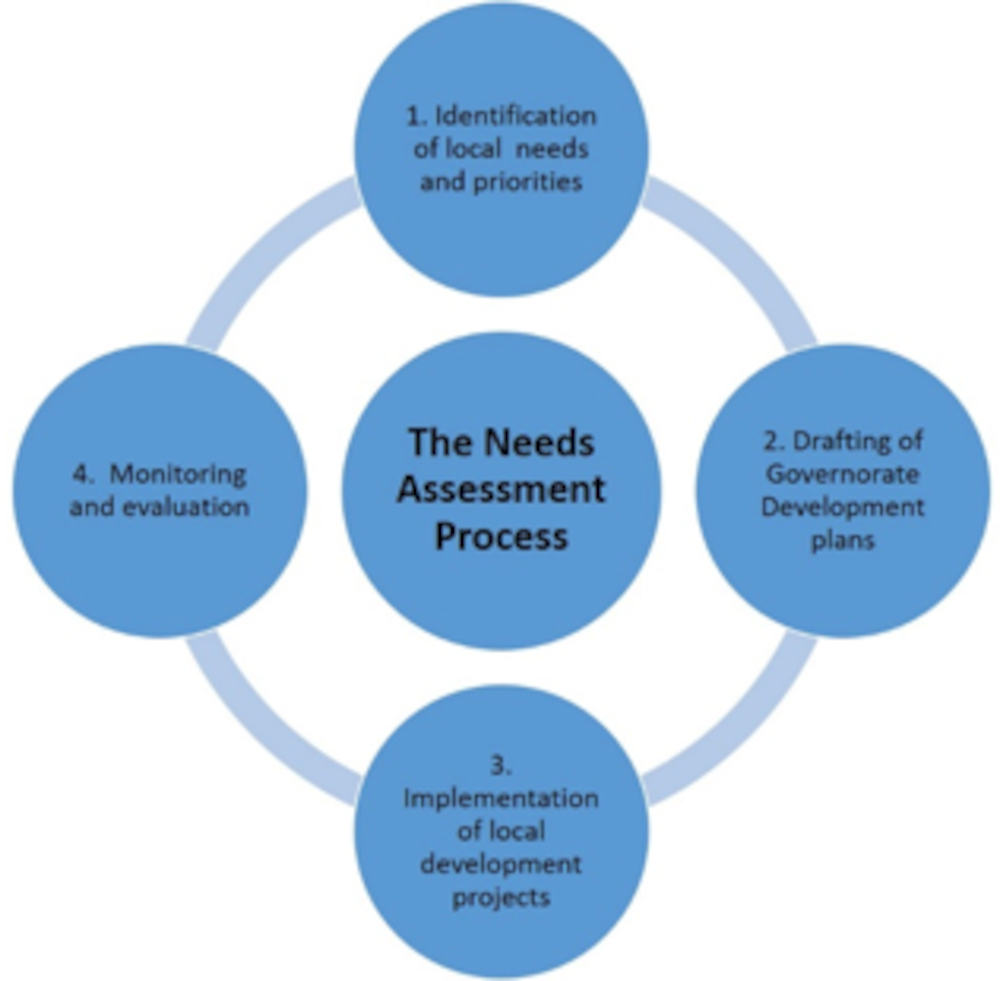

Mainstreaming participation at all levels of the policymaking process helps ensure that outcomes respond to citizens’ needs and expectations. Indeed, from the definition of policy priorities to their actual implementation and evaluation, stakeholder participation is a core element for the success of local policies (OECD, 2016) (See Figure 4.3). Paraguay, for example, has established a systematic process to engage with local communities in the creation of local development plans (See Box 4.1).

Figure 4.3. Stages of the Policy Making Cycle

Source: OECD (2016), Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD

Box 4.1. Creating Local Development Plans with local communities in Paraguay

In 2014, the Ministry of Planning for Economic and Social Development (STP) in Paraguay, as one of the commitments made in their OGP National Action Plan, introduced a requirement for all municipalities to draft and present participatory Local Development Plans (LDPs) as a condition for receiving funds. The commitment mandated that municipalities adopted an open and participatory process to develop the LDPs: i.e. one that is transparent regarding the resources the municipality has and responsive to how the community believes they should be used.

This led to the development of 232 Municipal Development Councils (MDCs) across the country, designed to bring together local elected representatives, neighbourhood groups, businesses, representative civil society organisations, and municipal civil servants to develop LDPs that will improve public services, reduce corruption, ensure efficient management of public resources, and increase corporate responsibility. (Prior to the creation of the MDCs, the main actors taking the decisions at the local level were Mayors and Governors and decisions were likely to be made unilaterally.)

To support the implementation of this new way of working, the STP held regional meetings to inform the public about the establishment of MDCs. Municipality leaders, governors and staff were also trained on how to use a participatory process to draft LDPs and align them with the objectives of the National Development Plan–2030.

The city of Itauguá, home to more than 89,000 inhabitants and in one of Paraguay’s most populated provinces with a mix of rural and urban areas, is one example of where the local authority, elected officials and civil society embraced the opportunities offered by this program.

For both the creation of the MDC, and for the subsequent development of the LDP for the city, a large scale participatory process was undertaken, which included substantial involvement from the general public.

The local authority started with an institutional diagnosis, which identified the strengths and weaknesses of the municipality. Sub-committees were then organised to develop proposals by issue area: Production; Health; Education; Childhood and Adolescence; Environment; Security; Infrastructure; Culture, Manufacturing and Sport; and Youth.

In an effort to consolidate the proposals in a way that both recognised the city’s challenges and prioritised solutions, the MDC developed a participatory budgeting process, carried out through a citizens’ assembly. At this event, the municipality shared information about the resources at the municipality’s disposal, the proposals developed by the MDC sub-groups, its budget constraints, and the capacity of various departments and civil servants. Based on this information, residents of the city defined and prioritised which problems needed attention most urgently. Although the recommendations of the MDCs are not binding, the recommendation of the citizens’ assembly in Itauguá were approved as part of the municipality budget for 2018.

Levels of engagement in the LDP process varied across the country, though officials note that their main challenge is keeping the MDCs running now that LDPs are in place. To help achieve this they have prepared support materials for developing monitoring plans for the process of implementation. These resources have been provided to all MDCs and include a “Matrix for Monitoring the Municipal Development Plan” to serve as a reporting tool to measure progress on commitments.

Source: Open Government Partnership (2018), Early Results of Open Government Partnership Initiatives, available online at: https://www.opengovpartnership.org/sites/default/files/OGP_Early-Results_Oct2018.pdf#

The iterative nature of the needs assessment process in Jordan represents an opportunity to include a variety of voices in the design of local policies and services. To maximize the value of stakeholder participation, initiatives ought to be embedded throughout all phases of defining local development projects and budgetary allocations (See Figure 4.4). As stated in Chapter 2, the current bottom-up approach consists of local and municipal authorities consulting citizens to develop a list of needs and priorities. This resulting needs manuals are shared with the Executive Council to develop the Governorate Needs and Priorities Manual with the help of GDUs. Once priorities are approved by the Governorate Council, the last stages of the process focus on the implementation of selected projects.

Figure 4.4. Stages of the Needs Assessment Process at the local level in Jordan

Source: Author’s own work

Nevertheless, OECD interviews noted the existence of different degrees of engagement throughout the stages of the needs assessment process. In its initial phase, local and municipal authorities consult more actively with citizens. However, findings highlight that potential remains to make use of the benefits of stakeholder participation across the subsequent phases of consulting, drafting, implementing and evaluating local development plans. While progress has been achieved since 2018, it appears that participation remains understood as a one-off exercise to collect feedback rather than a partnership for co-creation with all interested parties.

Notably, the first stage of the identification of priorities is where citizens are most actively engaged at both local and municipal levels. Participation takes the form of open hearings, public consultations and an open-door policy from the mayor, such as the case of the Municipality of Salt. However, once the municipal document of needs is transferred to the Executive Council, findings from OECD interviews suggest that public validation processes and consultations by GDUs diminish significantly.

Local authorities in Jordan could therefore build on the existing participation activities to include Governorate stakeholders in a more systematic way. In particular, LDUs and GDUs could coordinate joint consultations at the Governorate level with citizens and municipalities on the transferred document of needs, for example, to increase ownership and buy-in. This would also help strengthen the relationship between citizens and Governorate Councils, and ensure that the needs lists continue to reflect local priorities as they are transferred from the Municipal to the Governorate levels.

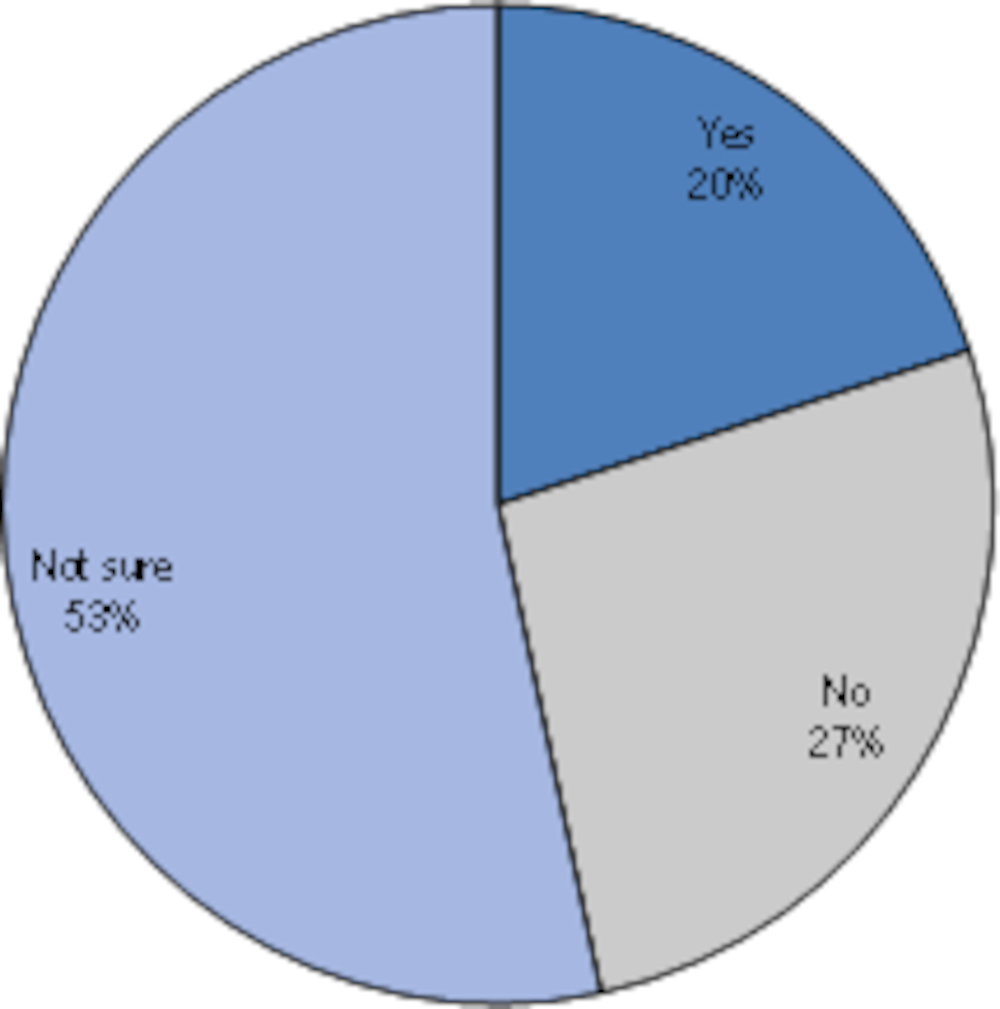

Moreover, subnational authorities should seek to leverage the benefits of participation throughout the remaining stages of the needs assessment process. Opportunities for stakeholders to participate in the drafting and approval of Local Development Plans and budget allocations are generally low. As a manner of illustration, OECD survey data shows that only 20% of responding CSOs consider that stakeholders’ contributions are reflected in the final plans, and 53% noted that this is unclear (see Figure 4.5). A second issue emphasizes the low level of ex post feedback, where 37% of CSO respondents, for example, were not able to submit public comments. Therefore, the establishment of validation and review processes could be considered for the final list of priorities before the approval of local plans through required quarterly hearings or evaluation reports. Creating meaningful opportunities for citizens to participate in the co-creation of plans could help address growing scepticism around the needs assessment process.

Figure 4.5. Share of CSOs noting whether they feel the contributions made by stakeholders are considered in the needs assessment process

Source: OECD (2019), Questionnaire for Civil Society Organizations: Stakeholder participation in Jordan’s needs assessment process.

In parallel, the engagement with contractors in charge of implementing local development projects is central to their effectiveness and sustainability. During OECD workshops, government officials emphasized that interactions with local partners are conducted on an ad-hoc basis. This in turn affects the ability of partners to implement local projects, primarily due to the low levels of information sharing and involvement in the feasibility assessment of projects. Therefore, there is an opportunity to strengthen the involvement of business contractors from the earlier stages of the needs assessment process.

Enhancing opportunities for consultation and engagement at the local level

The creation of new participation opportunities alone, however, does not necessarily lead to an equivalent increase in the quality and legitimacy of policy decisions. Meaningful opportunities to participate call for citizens to have a greater role in the co-design of local policies and services. Indeed, new spaces for local participation need to be accompanied by the systematic inclusion of a diverse group of stakeholders, going beyond the usual suspects (OECD, 2016; OECD, 2017a).

At the national level, Jordan has achieved progress in promoting the participation of stakeholders in the framework of the country’s open government agenda. The development process of Jordan’s fourth OGP National Action Plan (2018 - 2020), led by the Open Government Unit in the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, was the most inclusive and consultative to date, with over 2,034 Facebook engagements (likes and comments); 269 participants in meetings and consultation sessions; and 145 responses to the opinion poll and call for public comments. Relevant for the decentralization reform, the third and fourth OGP National Action Plans include commitments focused on enhancing partnerships and dialogue with civil society and fostering national dialogues for political reform, further highlighting the relevance of this topic in Jordan. As these efforts have mainly focused at the national level, however, there is an opportunity to leverage the opportunities presented by decentralization to further embed the principles of stakeholder participation at the local level. As in the case of Tunisia (see Box 4.2), OGP commitments could target a selection of governorates to implement participation initiatives around the decentralization process. More broadly, the country could consider expanding its current collaboration to join the OGP Local Programme.

Box 4.2. Implementing local OGP commitments in Tunisia

Since 2011, over 332 local level commitments have been made within the OGP National Action Plans of 60 countries around the world. For example, Tunisia recently developed its first commitment to embed the principles of open government at the local level.

Specifically, commitment 11 of Tunisia’s Third OGP National Action Plan calls for the implementation of initiatives to promote transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation at the local level. The aim of expanding the scope to the sub-national level is for municipalities to develop initiatives that are in line with the region’s characteristics and requirements, as well as rendering the administration more accessible to citizens.

To ensure its relevance, the Tunisian Government, in close collaboration with civil society, opened a call to select 12 Municipalities that will be included in local level OGP activities. Out of 73 applications received, the twelve selected municipalities were announced on October 2019. Activities will be coordinated through regular meetings of a joint committee comprising of representatives of the administration at the municipality level and representatives of the region’s residents.

Source: Open Government Partnership, Tunisia (2019) Call for applications for the selection of municipalities to implement initiatives devoting the OGP at the local level, available online at: http://www.ogptunisie.gov.tn/en/?p=1762

With the election of Governorate and Local Councils in 2017, sub-national authorities have also began a process to engage citizens in the design of local development plans. A range of participation practices to collect needs are carried out mostly by LDUs, including the organization of hearings, consultations and online surveys. These practices, however, focus primarily on consulting citizens on needs rather than involving them in the broader co-design and co-production of local policies and services. Moreover, the scale and representativeness of these initiatives tend to vary across large and small governorates and are still conducted on an ad-hoc basis.

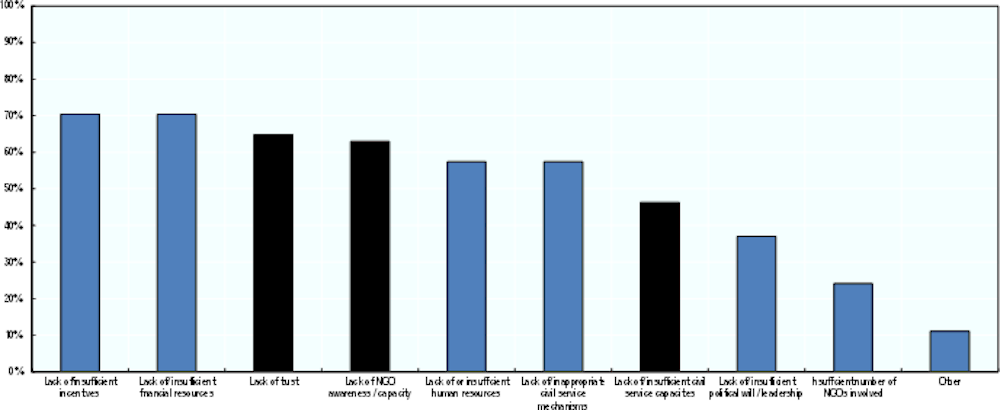

As a result, participation levels since the first needs assessment in 2018 remain generally low. A perception survey conducted in 2018 identified that 46% of Jordanians noted no change in the number of opportunities to participate in the definition of priorities for their municipality, followed by 28% that perceived even fewer instances (International Republic Institute, 2018). These findings align with OECD survey data, where less than half of responding CSOs (12 out of 30) have participated in the needs assessment process. Public servants in their majority attribute the “lack of trust”, “lack of awareness of CSOs on their role within the decentralization process” and “lack of communication” as the main reasons for the low involvement of stakeholders in this process (see Figure 4.6). OECD interviews also found a general lack of data collected on the degree and level of participation of citizens, civil society and businesses in the needs assessment process. In line with the section above, the Government could benefit from instilling a mechanism that documents levels of participation to inform the design of future activities and better showcase results.

Figure 4.6. Main Challenges in Engaging Stakeholders in the Needs Assessment Process

Source: OECD (2019) Questionnaire for Sub-national Authorities: Stakeholder participation in Jordan’s needs assessment process

An exception where participation has indeed been documented to inform policy reform in the framework of decentralization is through Jordan’s National Dialogue. Its 2019 edition consisted of 43 sessions with a total of 1,568 participants from civil society, academia and government across the 12 Governorates. While the National Dialogue has been an effective platform to bring about changes to the decentralization process, the Government of Jordan could institutionalize this mechanism and increase its reach through the formation of sub-committees with civil society, academia and public authorities from large and small governorates equally.

More broadly, the Government of Jordan should focus on increasing the representativeness and procedural effectiveness of participation initiatives, with a focus on transitioning from consultation toward engagement. In line with practices from OECD member and partner countries (see Table 4.1), Jordan could make use of a range of participation mechanisms according to the needs of local communities. Making use of novel forms of stakeholder participation, such as citizen panels and deliberative processes, could promote new mechanisms to engage the public in a more meaningful way (see Box 4.3 on the experience of Citizen Panels in Melbourne). To maximize these benefits, however, institutionalizing participation initiatives would help expand the engagement and increase the representativeness of stakeholders. In this respect, the current reform of the Local Administration Law presents a valuable opportunity to consider the inclusion of provisions regarding the institutionalisation of these practices across subnational entities.

Table 4.1. Overview of stakeholder participation practices in OECD countries

|

Name of the initiative |

Goal |

Nature of topics discussed |

Organiser |

Duration/number of participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

21st Century Townhall Meeting |

Advise decision makers through the use of modern technology |

Mainly local issues (e.g. communal development) |

Municipalities, agencies |

1 day/ 500-5 000 people |

|

Citizen Forum |

Strengthen democratic competencies, initiate debate in society |

Discussions on regional, national and transnational issues |

Private foundations (to date) |

Various weeks/300-10 000 people |

|

Participatory budgeting |

Citizens participate in budget decisions |

Setting of priorities for expenditures and consolidation of local and communal budgets |

Local politicians, local government |

Various months (up to 10 000 people) |

|

Citizen Panel |

Advise decision makers |

Feedback for politicians and service providers, long-term change in public perception |

Local politicians, local government, other stakeholders |

3-4 years (up to 4 surveys each year)/ 500-2 500 people |

|

Citizens’ Council |

Influence debates in society, advise decision makers |

Communal development and local topics |

Local politicians, local government, clubs, enterprises |

2-day meetings in various months/ small groups of 8-12 people |

|

Deliberative Polling |

Information transfer, deliberation |

Wide range of topics, ranging from local to transnational issues |

Political decision makers |

Various weeks/300-500 people |

|

Consensus Conference |

Exchange among experts and laypersons |

Controversial topics of public interest, local to transnational questions |

Agencies |

3 days (+2 preparation weekends) /10-30 people |

|

National Issues Forum |

Information transfer, acquisition of competencies |

Different topics linked to public organisation of local to national relevance |

Municipalities, schools, universities and other educational institutions |

1-2 days/10-20 people |

|

Open Space Conference |

Brainstorm and develop new ideas |

Potentially any topic which requires a new or creative idea |

Enterprises, clubs, agencies, communal agencies, educational institutions, church,. |

1-3 days/ flexible (10-2 000 people) |

|

Planning for Reality |

Reorganise common spaces |

Projects in urban planning |

Local politicians, local government, similar institutions |

Various months/ flexible |

|

Planning Cell |

Integrate citizens’ knowledge into planning decisions |

Problems of local and regional planning (urban planning, infrastructure) |

Local politicians, local government, similar institutions |

2-4 days (flexible, max. 25 people per planning cell) |

|

Scenario technique |

Balance different future scenarios |

Anticipation of future developments and issuing recommendations on different topics (local to transnational) |

Enterprises, clubs, institutions, local government, educational institutions, church ,etc. |

1-3 days/flexible (25-250 people, max. 30 people per group) |

|

World Café |

Use of collective intelligence |

Potentially any topic which requires a new or creative idea |

Enterprises, clubs, institutions, local government, educational institutions, church etc. |

Flexible (3 hours to 2 days)/flexible (12-1 200 people) |

|

Future workshop |

Develop creative approaches to solving complex challenges, and common perspectives on the future |

Long-term changes and ways to influence processes and projects |

Municipalities, institutions, organisations, clubs, etc. |

2-3 days/ flexible (max. 25 people per group) |

Source: OECD (2019), Open Government in Argentina, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1988ccef-en.

Box 4.3. The City of Melbourne’s Citizen Panel

In 2014, the City of Melbourne Council faced the challenge of balancing its budget, within a context of a growing need for infrastructure investment, a changing population, and an $800-900m (AUD) budget gap between what council had promised to deliver and its capacity to fund it on current budget settings.

In preparing for its 10 Year Financial Plan, the Council took an open policy making approach and sought advice from the public to help determine how projects should be funded and which ones should be prioritised, while retaining an overall goal to “remain one of the world’s most liveable cities, [and maintain a] strong financial position.”

After a wide-ranging process of open consultation with the public, the government established the People’s Panel (45 residents randomly selected to be representative of the city’ population). Meeting for daylong sessions on alternate Saturdays over 2-3 months, the panel engaged in a process of learning about the issues (including the open and transparent assessment of the Council’s budget, revenue streams and investment plans), weighting up priorities and options and developing recommendations.

These recommendations, which were assessed as being realistic and “highly implementable”, included:

Supporting the sales of non-core assets to reduce the council's property portfolio;

Increasing funding to address climate change;

A 5 year plan for introducing more bicycle lanes in the city;

Decreasing expenditure on new capital works by 10% over the next 10 years;

Raising local taxes paid to the council by up to 2.5% per annum for 10 years.

The final 10 Year Financial Plan produced by the City of Melbourne Council was heavily influenced by the People’s Panel, with 10 of the 11 recommendations made broadly accepted. This plan not only solved the budget deficit but also increased panel members’ sense of satisfaction with the city’s direction: evaluations showed that 96% of them highly rated their experience as part of the People’s Panel and had “higher levels of confidence in the City of Melbourne”.

Source: City of Melbourne (2019), Participate Melbourne, accessed on 5 May 2019, https://participate.melbourne.vic.gov.au/10yearplan

Building mechanisms to support stakeholder participation at the local level

The successful implementation of stakeholder participation initiatives depends largely on the existence of adequate institutional structures. To that end, the lack of standards and mechanisms (i.e. guides, manuals, protocols) is one of the main bottlenecks to institutionalizing stakeholder participation in Jordan. According to OECD survey data, the majority of government respondents noted insufficient incentives (70%) and the lack of public service tools and mechanisms (57%) as two key barriers in involving stakeholders in the needs assessment process. As previously mentioned, tools and guidance needed at the local level should be backed up by a comprehensive legal framework for decentralization that acknowledges the important role of stakeholder participation. This lack of institutional mechanisms, however, has implications for both government authorities and CSOs alike.

For public authorities, establishing and clarifying mechanisms at the three levels of government will be key for public servants to integrate stakeholders in local activities. Findings from OECD workshops highlighted a lack of standards on how to go about engaging with stakeholders. This challenge was particularly emphasized by LDUs, were capacity and resources to carry out consultations is often lacking.

A first step to mitigating these challenges could therefore include the assignment of clear institutional responsibilities for local, municipal and governorate actors on stakeholder participation initiatives. This could be followed by a series of capacity building activities to support these functions, and the development of a set of consultation guidelines on, for example:

1. How to engage stakeholders at each stage of the Needs Assessment Process and mapping the process and opportunities for participation;

2. How to ensure representativeness and diversity of stakeholders; inclusivity throughout all stages of the process; ensure gender sensitivity; the development of criteria to map stakeholders;

3. How to validate inputs by citizens; and

4. How to communicate throughout the process and about results to maximize impact in a way that is easily accessible in a clear, complete, timely, reliable and re-usable format.

For CSOs and citizens, furthermore, mechanisms are also needed to ensure that they have not just the opportunity, but the capacity to participate in the development of local development plans. OECD data shows that while 60% of responding CSOs received capacity building related to the needs assessment process, these trainings were carried out by other national or local CSOs (89%) or donor organizations (39%). To this end, the MoLA could adopt a larger role in providing these trainings to increase CSO capacity and engagement, as well as ensure that trainings are provided across the country. Capacity building modules could also be designed to raise the awareness on any future legal reforms, as well as to provide civil society with the appropriate tools, guidelines and skills to leverage their role throughout the decentralization process. Topics could include identifying policy priorities, evaluating performance indicators, using and re-using open government data, submitting information requests and social media engagement, amongst others.

Solely establishing mechanisms, however, will not ensure their uptake. More broadly, the country should seek to promote a culture of openness and continuous learning at the sub-national level. To that end, a multi-stakeholder platform could be designed to promote an open dialogue between government representatives, civil society, private sector and citizens from different local communities. This platform could build on efforts from the National Dialogue to share best practices, reflect on lessons learned, identify common challenges and promote participation throughout the decentralization process. Such a platform could take the form of a local innovation laboratory to build a community of practice, as in the case of Santalab in the Santa Fe Province in Argentina (see Box 4.4); it could also take the form of an informal network of mayors focused on increasing coordination and cross-fertilizing best practices within governorates.

Box 4.4. Promoting citizen-driven innovation at the local level: The case of Santalab

Santalab is an open citizen innovation laboratory in the province of Santa Fe, Argentina. Santalab serves as both a virtual and physical space where citizens, public authorities and businesses can meet and work together. Santalab carries out three different types of activities – namely outreach, training and prototyping activities – targeting specific audiences. Through its outreach activities, the lab aims to raise awareness of key local level issues and promote a space for community engagement. Santalab also provides training and co-creation activities through free workshops aimed at building the capacity of key players to contribute to the development of local policies and the design of services. It also promotes a space for experimentation and prototyping aimed at embedding citizen innovation at the core of the machinery of the local administration.

Source: OECD (2019), Open Government in Argentina, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1988ccef-en.

Recommendations

With the rapid transformations brought by the decentralization reform, sub-national authorities are adopting initiatives to inform, consult and engage stakeholders in the needs assessment process. Acting on the lessons learned from two needs cycles will be essential to establish new partnerships with citizens. Broadly, a meaningful and open relationship calls for sub-national authorities in Jordan to scale up efforts toward changing the role of citizens from passive receivers to that of partners in the co-creation of local policies and services.

Bridging the divide between sub-national governments and citizens is a primary objective of the decentralization reform. Despite the progress achieved in terms of opening the decision making process for local development plans, there is room to leverage participation opportunities throughout all the stages of the needs assessment process. Ensuring effective stakeholder participation will also require the promotion of stakeholder diversity, in particular of under-represented groups. In parallel, efforts will entail building necessary structures to support stakeholder participation at the local level, through skills and best practice sharing.

To this end, the Government of Jordan could consider the below recommendations:

Leverage current OGP activities to promote the principles of stakeholder participation at the local level through the development of commitments in selected governorates. The administration could also consider including a commitment in the next OGP action plan aimed at supporting participation at the local level. More broadly, the country could consider expanding its current collaboration to engage several municipalities in the OGP Local Programme.

Increase the scope of activities for citizens to participate throughout all the stages of the needs assessment process, in particular at the drafting and validating phases of local development plans. Participation mechanisms could also be used to share updates and outcomes of the needs assessment plans and how these supported the approved local development plan.

LDUs and GDUs could coordinate joint consultations with citizens and municipalities on the transferred document of needs, for example, to increase ownership and buy-in.

Assign clear institutional responsibilities for stakeholder participation for local, municipal and governorate actors, including LDUs and GDUs.

Develop and adopt a mechanism for governorate and municipal entities to document the levels of participation in local activities. Measuring the impact of stakeholder participation initiatives will not only help inform the design of future activities but also showcase results to the highest political levels.

Establish participation initiatives that move beyond sole consultation to assign a more direct and meaningful role for citizens in the co-creation of local policies. The Government of Jordan could thus consider adopting engagement practices such as citizen panels, planning cells and other deliberative processes.

Consider the inclusion of provisions to institutionalise consultations and other participation related initiatives as part of the ongoing reform of the Local Administration Law. This would not only clarify the mandate for municipal and governorate actors, but also help consolidate implementation mechanisms, promote their adoption and reiterate the values of stakeholder participation beyond solely the Renaissance Plan.

Develop a set of consultation guidelines aimed at all government stakeholders focused on:

1. How to engage stakeholders at each stage of the needs assessment process and map processes and opportunities for participation.

2. How to ensure representativeness and diversity of stakeholders and establish criteria to identify stakeholders.

3. How to validate inputs by citizens.

4. How to communicate throughout the process and about results to maximize impact.

Develop a set of criteria or standards on how citizens can develop their list of needs. These standards could be included in the manual shared to municipal stakeholders by national authorities and be widely disseminated.

Leverage the role of MoLA to design and carry out more capacity building modules aimed at providing civil society organizations with the appropriate tools, guidelines and skills to leverage their important role throughout the decentralization process. These workshops could raise awareness around key issues by focusing on current gaps, such as identifying policy priorities, evaluating performance indicators, engaging and communicating with public officials, among others.

Expand on the National Dialogue to develop a formal multi-stakeholder platform to promote an open dialogue between government representatives, civil society, private sector and citizens from different local communities. The platform could take the form of an innovation lab or an informal network of mayors to share best practices, reflect on lessons learned, identify common challenges and solutions to promote stakeholder participation throughout the needs assessment process.

References

Arab Barometer (2019), Jordan Country Report, https://www.arabbarometer.org/countries/jordan/

International Republican Institute (2018), Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Jordan, Center for Insights in Survey Research, available online at: https://www.iri.org/resource/jordan-poll-reveals-low-trust-government-increasing-economic-hardship

Mahadin E., Binda C. & Khasawneh M. (2018), Legal Review of the Jordanian Decentralization Law, issued by Karak Castle Center for Consultations and Training.

OECD (2017a), The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, OECD Legal Instruments, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/public/doc/359/d5392da9-6aa6-4647-b266-2e37694c497f.htm

OECD (2017b), Contextualising decentralisation reform and open government in Jordan, in Towards a New Partnership with Citizens: Jordan's Decentralisation Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264275461-5-en.

OECD (2017c), Organisation and functions at the centre of government: Centre Stage II, survey response report, internal document.

OECD (2016), Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268104-en.

Note

← 1. Municipal: to a moderate degree (37%) + large degree (15%); Governorate councils: to a moderate degree (33%) + large degree (11%); Parliament: to a moderate degree (11%) + large degree (2%)