This chapter starts with an overview of the policy landscape for rural innovation and identifies drivers and barriers to innovation in rural Switzerland. Specifically, it investigates if local, regional and national framework conditions are conducive to and account for the specific characteristics of rural innovation using evidence from the case study areas around the regional innovation systems (RIS) in Basel-Jura, Central Switzerland and Western Switzerland. It also makes suggestions to address bottlenecks in the delivery of innovation support, broaden the concept of innovation, create a culture of experimentation, strengthen rural-urban linkages and improve skills shortages for rural innovation.

Enhancing Innovation in Rural Regions of Switzerland

3. National, regional and local policy framework conditions for rural innovation in Switzerland

Abstract

Innovation in rural areas is more incremental, making use of locally available knowledge and taking time to experiment (see Chapter 1). This is a result of both limited accessibility of knowledge, finance and other resources in the countryside and the size of firms and their focus on sectors that do not lose value as quickly, including natural resources. As such, rural innovation is less time-dependent and characterised by high levels of meaningfulness to the community while still competing successfully in the market economy. Rural entrepreneurs often bridge knowledge gaps strategically, building networks with partners such as suppliers and higher education institutions when looking to steadily improve their products. A key element of rural innovation is also passing down knowledge through inter-generational links. In times of demographical change and increasing numbers of younger people leaving for the cities, this can become an increasing challenge, not only in terms of succession but also because young people are more likely to be innovative and use newer products and processes.

This chapter makes recommendations to enhance rural innovation in Switzerland. It starts with an overview of the policy landscape and its stakeholders for rural innovation and identifies drivers and barriers to innovation in rural Switzerland. It draws on evidence provided by the federal administration on the Swiss decentralised innovation policy approach as well as three regional innovation systems, notably, RIS Basel-Jura, RIS Central Switzerland and RIS Western Switzerland (ARI-SO). Considering the vast innovation potential in rural Switzerland, it investigates if local framework conditions are conducive to and account for the specific characteristics of rural innovation. Specifically, it focuses on broadening the concept of innovation, future-proofing innovation agendas, building a culture of experimentation and simplifying access to services, and developing rural-urban linkages to increase the flow of knowledge and people. Overall, the chapter shows that for rural innovation, policy makers should focus on adjusting innovation support to focus on the comparative advantages of rural regions, while enhancing enabling conditions in currently lagging behind rural areas, adjusting for the variety of rural places in their programming.

Switzerland’s decentralised innovation system

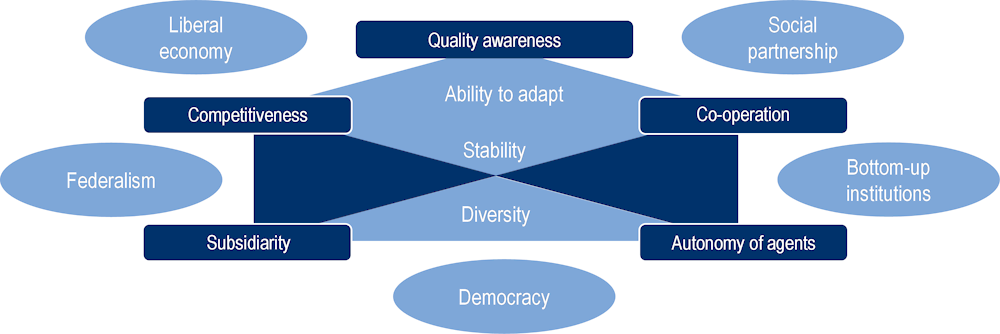

Switzerland has no overall innovation policy but follows a decentralised approach through several independent policy areas that are co-ordinated through mechanisms involving federal, cantonal and regional (cross-cantonal) actors. This organisation grants individual agents a high degree of autonomy and scope for action. It also allows for tailor-made answers to new emerging challenges. The binding element of this decentralised approach are principles shared by the main agents in the system. They include federal actors (e.g. Innosuisse), public education and research organisations, cantonal actors and programmes (e.g. Living Labs, projects), RIS and private programmes for start-ups. They form the basis of the structure of the Swiss innovation system and comprise subsidiarity, the autonomy of agents, co-operation, competitiveness and quality awareness. They are embodied in framework conditions, including democracy, federalism, liberal economy, social partnership and bottom-up institutions. This results in three other characteristics of the Swiss innovation system: diversity, stability and ability to adapt. The most important principles and framework conditions are presented graphically below (Figure 3.1).

Within the structure, both institutionalised and informal processes enable collaboration. Formal processes for instance include internal administrative procedures such as consultations and co-reporting procedures. This ensures that individual actors are informed about the activities of the others, insofar as they are affected by them. More informal or ad hoc processes also exist. They include steering groups, monitoring groups or other ad hoc bodies formed to contribute to individual projects. Co-ordination generally ensures that relationships between individual stakeholders are maintained and activities co-ordinates – especially if several actors are pursuing similar projects at the same time. Such co-ordination processes, which initially take place infrequently, can, if necessary, be institutionalised over time.

Figure 3.1. Swiss Principles, structures and processes of the decentralised Innovation System

Note: Central principles of the Swiss Innovation system are depicted by the darker rectangular shapes, and the lighter oval shapes represent the framework conditions.

Source: Adapted from Swiss Federal Council (2018[1]), Overview of Innovation Policy, https://www.sbfi.admin.ch/sbfi/en/home/services/publications/data-base-publications/innovation-policy.html.

Institutional context

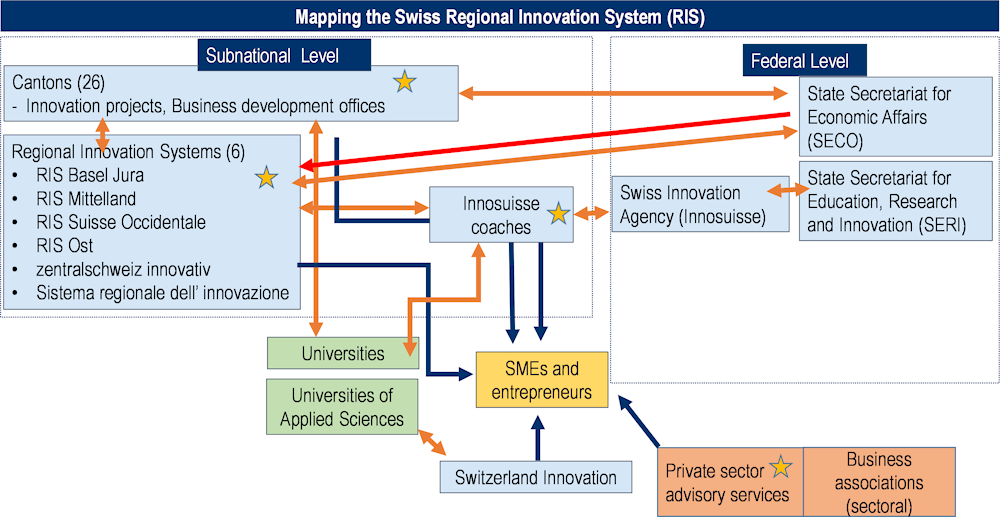

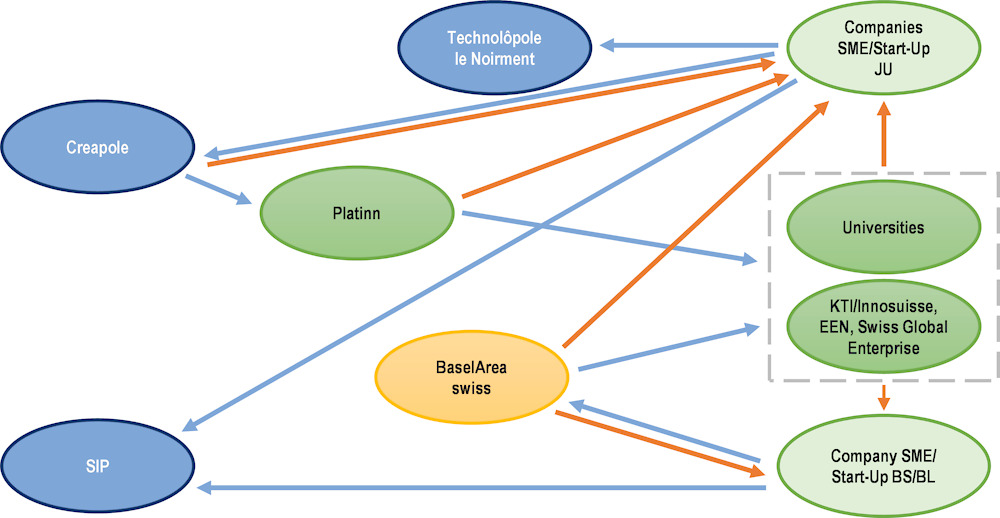

Because of its decentralised nature, the Swiss innovation system functions as a complex ecosystem. Figure 3.2 depicts the main elements of the decentralised regional innovation system in Switzerland, focusing on small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and entrepreneurs as the benefactors. A study by the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) in 2016 recorded 138 innovation promotion offerings at the national, cantonal and regional levels, which can sometimes be perceived as complex (SERI, 2016[2]).

Figure 3.2. Simplified representation of the Swiss decentralised innovation system

Note: Orange arrows show the flow of information, and blue errors show a service provided. Yellow fields describe the target groups (SMEs and entrepreneurs), blue fields show public actors and institutions, green fields depict public education and research organisations, stars signify advisory services or components, and red arrows describe framework settings and regulations.

Federal level

From a legal perspective, public research and innovation funding is the responsibility of the federal government. The promotion of innovation is regulated by Federal Act on the Promotion of Research and Innovation (RIPA). RIPA is a framework law that governs the objectives and funding of research and innovation by the federal government. It includes legally enshrined principles such as freedom of research, the scientific quality of research and innovation, the diversity of scientific opinions and methods as well as scientific integrity, and good scientific practice principles of research that define federal innovation funding (see RIPA, Article 6, Paragraph 1, Fedlex (2012[3])).

RIPA (see Article 6, Paragraph 3) also establishes overarching goals including the sustainable development of society, economy and environment and the (national and international) co-operation of the actors. The instruments of the innovation promotion policy according to RIPA primarily cover knowledge-based innovation. They support processes by which scientific knowledge can be developed into marketable products. As part of the business-oriented approach to innovation, instruments of economic policy are also added, specifically location promotion policy, growth policy, SME policy and intellectual property protection (Swiss Federal Council, 2018[1]).

The responsibilities in research and innovation (R&I) funding at the federal level are primarily shared among the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research (EAER), SERI, the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), the Swiss Innovation Agency Innosuisse, as well as the council of the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology (ETH Board) on behalf of the institutions of the ETH Domain. Other departments such as the Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications (DETEC) are also directly or indirectly involved in R&I funding. The Swiss Science Council (SSC) is the advisory body of the Federal Council for issues related to science, higher education and R&I policy.

Furthermore, there are additional innovation activities within various sectoral policy areas. These activities seek to achieve specific political goals, such as nationally and internationally set goals for environmental protection and reduction of energy consumption. The primary purpose of these programmes is therefore to reach the respective policy objectives, while innovations are the means to achieve these goals.

In terms of funding, the Federal Council submits a request to parliament on the promotion of education, research and innovation (ERI) every four years. As part of this, it formulates the guidelines and measures of its policy for ERI for which the Swiss Confederation has primary responsibility. These include the ETH, vocational education and training, R&I promotion and international co-operation in education and research. The request also formulates the confederation’s commitment to those parts of the system that are primarily the responsibility of the regions (cantons), such as universities, universities of applied sciences, implementation of vocational education and training and the scholarship system. Based on this request, the parliament then decides on the funding framework.

Innovative entrepreneurship is largely executed by cantons, cities, municipalities and private actors, as well as the RIS. These will be discussed in more detail below. The federal level mostly tries to complement activities led by lower government levels and actors, for instance through its innovation agency Innosuisse. The role of the agency is to promote science-based innovation in the interest of the economy and society in Switzerland. To this end, Innosuisse promotes partnerships between academia and businesses and seeks to accelerate the transfer of knowledge from research to industry. It also helps innovators and start‑ups to achieve a breakthrough in the market. The core of Innosuisse funding is the support of innovation projects. In these projects, innovative organisations such as companies, start-ups, administrative bodies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) develop new services and products together with research institutions. Some projects also involve international partners. Further, the agency supports networking, training and coaching, with the goal of providing the foundation for successful Swiss start-ups as well as innovative products and services (Innosuisse, 2022[4]).

Box 3.1. Innosuisse Innovation Booster

The Innovation Booster programme powered by Innosuisse is designed to specifically support radical ideas in a culture of open innovation. Supporting the primary stage of an open innovation process, they provide the impulses for innovative ideas and help them to get off the ground into the market.

The main mission of the programme includes:

Bringing together all interested players from research, business and society on various innovation topics.

Promoting knowledge transfer and encouraging co-operation with partners along the entire value chain of a topic. Each booster has its own organisation and Leading House.

Using design thinking methods and other user-centred methods. The Innovation Boosters support companies, start-ups and other organisations to identify and explore problems in interdisciplinary teams and develop new and radical solutions from scratch.

Providing an apt funding amount to finance and support the testing and verification of promising ideas and assisting teams to get follow-up support to further develop or implement their idea.

Fostering a culture of open innovation, to create sustainable competitive advantages for innovative Swiss organisations and SMEs.

Innosuisse selects Innovation Boosters with regular calls for proposals for a four-year period. The selection is based on a range of criteria which include:

The current and future importance of the innovation topic.

The likelihood that it will give rise to future innovation projects.

The appropriateness of the methods and mechanisms used to promote the transfer of knowledge and technology.

The competency to address the innovation topic and involve the relevant actors on a national scale.

The plausibility of the budget and cost-benefit ratio, the degree of own-funding and the contribution of third-party funds.

The contribution to the sustainable development of society, the economy and the environment.

Measures to ensure appropriate gender representation in the organisation and at activities.

Key performance indicators (KPIs) on gender are supposed to motivate initiatives to proactively increase the percentage of women on their boards as well as among their speakers and participants. This is especially interesting in some fields which are historically unbalanced with respect to the participation of men and women.

Innovation Boosters are selected under a complementarity principle: Innosuisse supports initiatives that would not easily be supported by the private sector only, because of inherent risk, lack of resources or private investments or unclear economic return. They should all have the potential to involve actors from all over the national territory.

The above criteria should allow Innosuisse to select Innovation Boosters that will create an impact in Switzerland. This includes societal impacts such as an increase in quality of life, addressing major societal challenges, better population health or economic impacts such as job creation, increase in revenues, etc.

Source: Innosuisse (2022[5]), “Innovation boosters”, Swiss Innovation Agency.

Subnational level

The vast majority of cantons engage in innovation and economic development activities. The range of services includes support for company start-ups or the promotion of regional networks or clusters in close contact with companies and sometimes specific coaching. Cantons generally have their own business development offices. They inform companies about location advantages, maintain contacts with investors, organise support for investors and handle customer care on site. Various cantons use tax breaks to promote businesses. Cantons also use their universities, universities of applied sciences and pedagogical universities to promote regional development and R&I. Cities and towns likewise are important in establishing technology or innovation parks (Swiss Federal Council, 2018[1]).

The federal government’s New Regional Policy (NRP) (for an in-depth description, see the following section) is important in financially supporting these subnational innovation projects and has allowed regional and cross-cantonal innovation initiatives to be established in most of Switzerland. Overall, the NRP has the objective to “enhance the competitiveness and added-value creation of individual regions and thus contribute to the creation of jobs to preserve decentralized settlement and to reduce disparities between regions”. The federal level is responsible for determining strategic objectives and spatial priorities as well as for ensuring legal conformity, while the cantons are in charge of policy implementation. They have maximum scope to define for their region how objectives are achieved, including project selection. The NRP is funded through the local promotion activities of the federal government (SECO, 2020[6]).

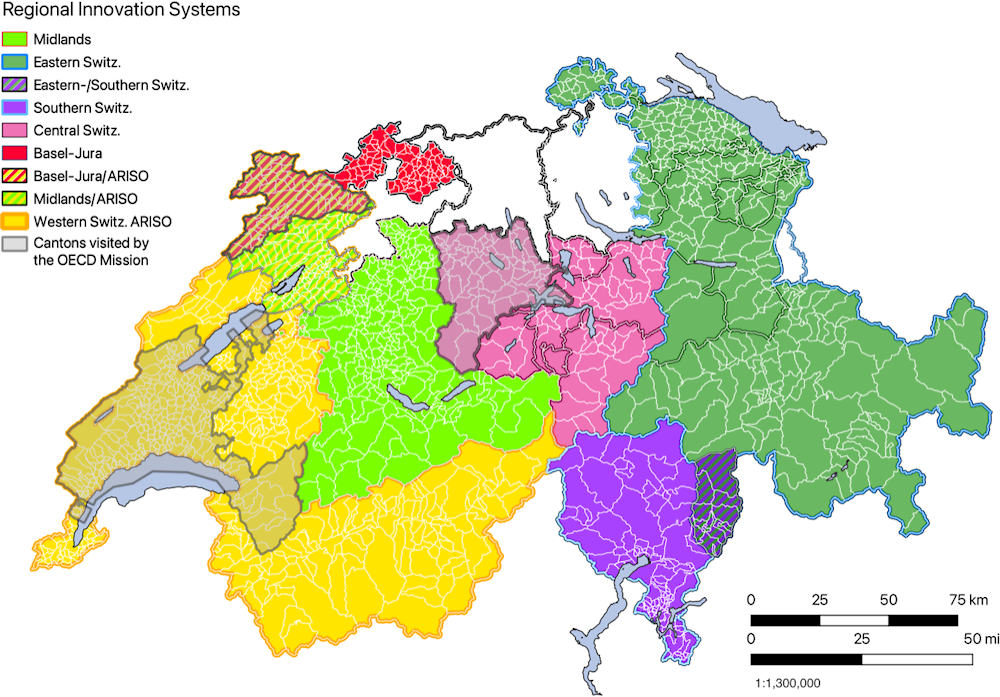

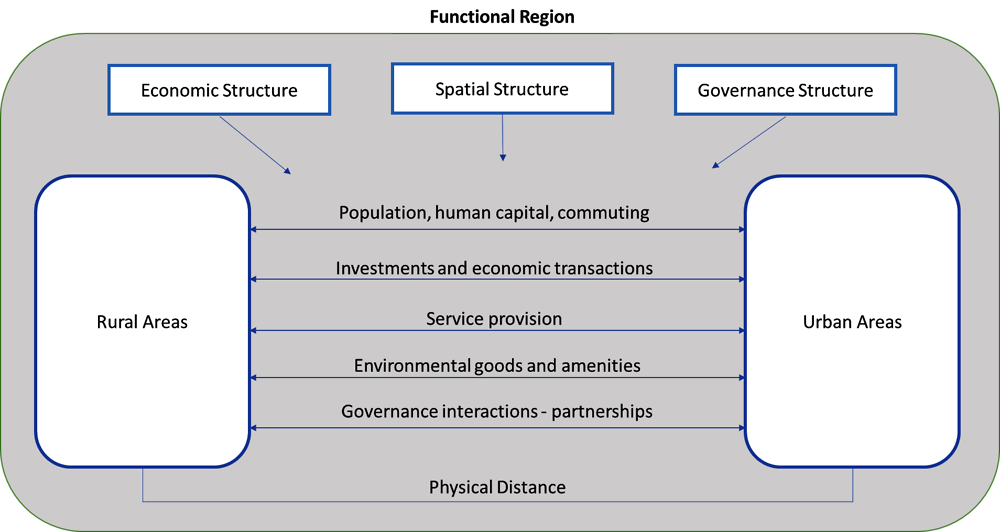

Part of the NRP is the regional innovation system (RIS). There are six RIS covering significant parts of the country (Figure 3.3). The RIS relate to functional (generally inter-cantonal and in some cases cross-border) economic zones. Complementary to the focus of the national research-driven innovation activities, their focus is on demand- and need-driven services, and a broader understanding of innovation that specifically targets SMEs. The RIS promote competitiveness and innovative capacity of SMEs by offering co-ordinated support and services in the areas of information, consulting, networking, infrastructure and financing. Following the principle of “no wrong door”, the RIS are meant to consolidate innovation and support activities from different governance levels and actors and connect SMEs with other sources of funding and assistance if necessary. Overall, the central tasks of the RIS can be summarised as follows:

Co-ordination of innovation promotion activities.

Coaching on the topic of innovation for start-up companies and SMEs.

Organisation of networking events.

Point of entry, referring individual companies to the right innovation funding agency (including universities and federal funding agencies) (SECO, 2017[7]; B,S,S Volkswirtschaftliche Beratung AG, 2018[8]).

This study specifically focuses on the NRP and its RIS structures because they, within the overall innovation ecosystem, have a specific territorial and rural focus. Understanding and analysing how they deliver for rural SMEs is thus crucial to understanding what works and what does not with regard to rural innovation in Switzerland and how policies to foster rural innovation can be improved. At the same time, these geographically focused policies are only small and financially limited mechanisms that need to complement and work in synergy with the more general policy tools and mechanisms described in this section.

Figure 3.3. Map of Regional Innovation System in Switzerland

Source: OECD elaboration in consultation with local partners.

The NRP and its role in supporting rural innovation in Switzerland

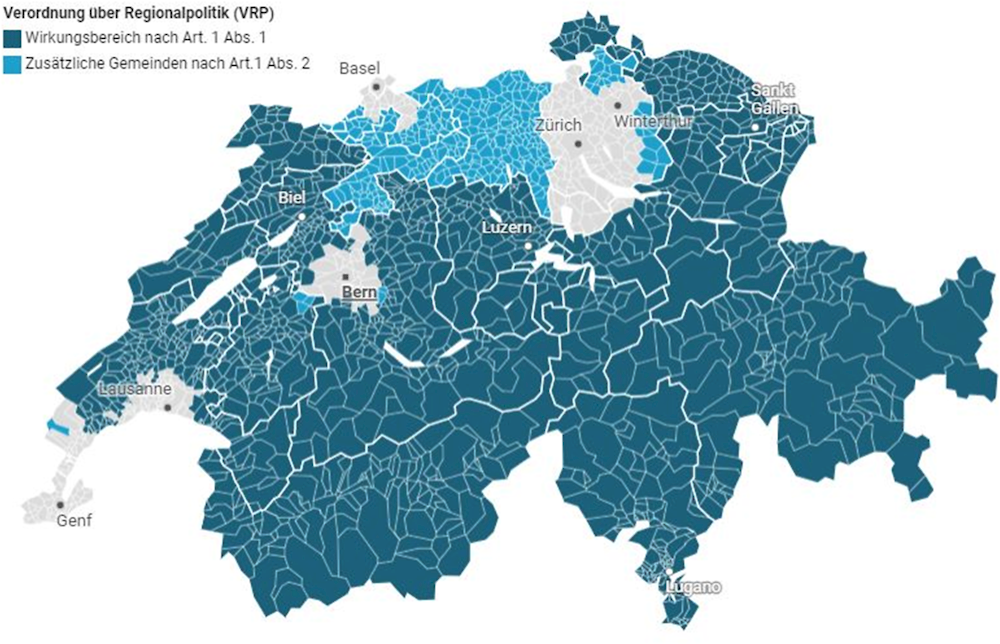

Throughout the mid-1990s, the scope of Swiss regional policy shifted away from redistribution towards a new focus on impact orientation, competitiveness and the creation of value-added in rural areas. This shift was formalised with the introduction of the New Regional Policy (NRP) in 2008, which encourages an endogenous “growth-oriented” approach emphasising open markets, export capacity and competitiveness. The policy specifically targets rural and mountainous areas, which incorporate the vast majority of Swiss territory but excludes the large agglomerations of Basel, Bern, Geneva, Lausanne and Zurich and the urban cantons of Aargau, Basel-Landschaft, Basel City, Geneva, Solothurn, Zug and Zurich. Exceptionally, cantons may request that NRP funds be used for excluded areas (Figure 3.4). The seven urban cantons may also apply for NRP funds if they can demonstrate that the areas to be supported present the same structural challenges as the traditional target areas of NRP.

The NRP is a joint task of the federal government and the cantons. The Swiss Confederation is responsible for strategic management and orientation, while the operational responsibility for implementation and the decision as to whether a project can be supported with NRP funds lies with the cantons (OECD, 2011[9]). At the cantonal level, the NRP provides direct financial assistance (federal and cantonal) in order to enable the implementation of suitable projects and programmes. It also acts at a supra-cantonal level in order to enhance geographic coherence and economic functionality. This includes funding for Switzerland’s participation in cross-border EU programmes, in particular Interreg, and funding for inter-cantonal RIS (OECD, 2019[10]).

Figure 3.4. Geographical range of the NRP, 2020-23

Note: The geographical range of the NRP defines the area in which the majority of specific development problems and development opportunities for mountainous and rural areas are the biggest. Only projects that have a majority impact in this area can be supported by the NRP. The geographical range of the NRP in dark blue (Regional Policy Ordinance, Article 1, Paragraph 1) and additional communities in light blue (Regional Policy Ordinance, Article 1, Paragraph 2).

Source: Regiosuisse (n.d.[11]), Financial Instruments and Measures within the Framework of the NRP, https://regiosuisse.ch/index.php/en/financial-instruments-and-measures-within-framework-nrp.

In 2016, the NRP multiyear programme started for a second eight-year period. The focus continues to be to “enhance the competitiveness and added-value creation of individual regions and thus to contribute to the creation and safeguarding of jobs in the regions, to the safeguarding of a decentralised settlement pattern, and to the reduction of regional disparities”. Its three pillars address: i) an increase in the economic strengths and competitiveness of regions (85% of total funding); ii) co-operation and synergies between the NRP and other sectoral policies (5-10% of total funding); and iii) capacity building in the knowledge system of regional policy (5-10% of total funding). The NRP also offers tax breaks to industrial companies and service providers whose business is closely linked to industrial production. With this, the government hopes to support the creation of new types of jobs in innovative fields in structurally weak regional centres (OECD, 2019[10]).

The latest additions to the NRP 2020 include support for pilot programmes for mountainous regions to provide additional stimulus where it is needed. The pilot measurements offer more flexible eligibility criteria for support for example, small, less profitable infrastructure initiatives can be co-financed with à-fonds-perdu contributions. Another new feature is the support of project preparations and the development of Living Labs for the development and implementation of unconventional ideas (SECO, 2020[12]).

The implementation period 2016-23 has a stronger focus on innovation and tourism. The emphasis is on innovation in SMEs. One part of the promotion is the aforementioned RIS that provide coaching and networking for innovation. The federal government supports these networks provided they have a functional area orientation, i.e. if they extend beyond cantonal or even national borders and are adapted to the needs of the defined target groups. Second, the multiannual programme 2016-23 sets a specific focus on promoting tourism in the regions, a sector that was exposed to strong challenges in recent years due to foreign exchange rates and that is increasingly exposed to the effects of climate change. Digitalisation is considered an overarching goal for economic development activities and needs to be transversally addressed.

The emphasis on competitiveness mirrors the early shift observed in other member countries from a sectoral focus which was codified by the OECD New Rural Paradigm1 in 2006. The OECD’s most recent Rural Well-being Policy Framework published in 2020 (OECD, 2020[13]) builds on the paradigm and calls for an even more robust model for rural development, one that considers the economy, society and the environment (see Table 3.1). It also stresses the importance of innovation for rural places to be able to deal with structural change and identifies important policy measures to enhance innovation capacity (OECD, 2020[13]). Some of these include strengthening rural-urban links, addressing the rural-urban digital divide in connectivity, as well as enhancing education and skills. This comes at a time when recovery from COVID-19 is starting, while the impacts of the megatrends of globalisation, digitalisation, climate change and demographic change continue to shape the economic landscape of rural economies.

Table 3.1. Stages of Rural Well-being: Geography of Opportunities

|

|

Old paradigm |

New Rural Paradigm (2006) |

Rural Well-being: Geography Of Opportunities |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Objectives |

Equalisation |

Competitiveness |

Well-being considering multiple dimensions of: i) the economy; ii) society; and iii) the environment |

|

Policy focus |

Support for a single dominant resource sector |

Support for multiple sectors based on their competitiveness |

Low-density economies differentiated by type of rural area |

|

Tools |

Subsidies for firms |

Investments in qualified firms and communities |

Integrated rural development approach – spectrum of support to the public sector, firms and third sector |

|

Key actors and stakeholders |

Farm organisations and national governments |

All levels of government and all relevant departments plus local stakeholders |

Involvement of: i) public sector – multi-level governance; ii) private sector – for-profit firms and social enterprise; and iii) third sector – non‑governmental organisations and civil society |

|

Policy approach |

Uniformly applied top‑down policy |

Bottom-up policy, local strategies |

Integrated approach with multiple policy domains |

|

Rural definition |

Not urban |

Rural as a variety of distinct types of place |

Three types of rural: i) within a functional urban area; ii) close to a functional urban area; and iii) far from a functional urban area |

Source: OECD (2020[13]), Rural Well-being: Geography of Opportunities, https://doi.org/10.1787/d25cef80-en.

While the NRP is rural and peri-urban focused, the RIS can improve in delivering for all rural areas

In 2011, the OECD’s territorial review (2011[9]) found that there were no explicit regional innovation policies in Switzerland. The report recommended that existing cantonal initiatives needed to be better co-ordinated and more effectively implemented, especially highlighting the potential of inter-cantonal initiatives (OECD, 2011[9]). Generally, RIS refer to functional economic spaces – usually cross-cantonal and sometimes cross-border – where networks of important actors for innovation processes, such as companies, research and education establishments, as well as public authorities work together in a network and contribute to the innovation processes of a region. In Switzerland specifically, the term is also used to describe the organisation that acts on the development and management of RIS. Overall, these RIS promote the competitiveness and innovative capacity of SMEs by offering co-ordinated support and services in the areas of information, consulting, networking, infrastructure and financing. In addition, they bundle other already existing support offers and refer SMEs to other funding bodies if required.

The concept of regional innovation systems (RIS) was introduced in its current form with the adoption of the federal government’s multiyear programme for the implementation of the NRP 2016-23. It thus became the prerequisite for the further support of innovation promotion offers within the framework of the NRP. The cantons, in co-operation with the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), have created RIS structures in six major regions of Switzerland (see also Figure 3.3).

The first RIS structures in the sense of an innovation promotion initiative motivated by regional policy date back to the activities in Central and Western Switzerland in the context of the 6th European Union (EU) Research Framework Programme. Building on already existing regional initiatives, the first RIS structure was created in Central and Western Switzerland until a federal regional innovation strategy was developed in a collaboration between SECO and the cantons in 2016. The introduction of RIS within the framework of the NRP established the RIS organisations as a central link between the federal government and the cantons in the operational implementation of an innovation-based regional policy (B,S,S Volkswirtschaftliche Beratung AG, 2018[8]). The system is also meant to provide complementary support to the national innovation promotion of Innosuisse, the Swiss Innovation Agency, focusing on knowledge absorption and more incremental innovation support.

The aim of the RIS created within the framework of the NRP is to simplify and harmonise innovation promotion for SMEs and start-ups. Thus, the innovation activity of companies in the NRP impact area is to be strengthened and the long-term economic development in these areas is to be supported. A central aspect of the funding activities to support innovation activity is the so-called "no wrong door" policy which is designed to ensure that a company’s request is always forwarded to the right place, depending on its specific needs.

In order to assure that RIS support fits with diverse local needs, it is important to consider that innovation in more rural areas functions differently than in the regional centres or the larger agglomerations. It seems like the support currently provided does not sufficiently take all geographic specificities and the corresponding needs into account. While research is limited, evidence suggests that rural innovators take a different approach (Table 3.2). They are experimental and strategic in that they take the time to steadily improve products and processes without pressure and acquire information to fill knowledge gaps. In this process, the meaningfulness of the work to the community and passing down knowledge through generations is also important as it ensures holistically following projects through from beginning to end (Mayer, 2020[14]).

The current Concept RIS 2020+ recognises the specific challenges of rural SMEs in the innovation process. It also notes that rural SMEs are often smaller and have less access to other innovation actors. It includes a call for stronger efforts to facilitate access to innovation support for rural SMEs (SECO, 2018[15]). To ensure this, funding from the NRP for the RIS programme areas “Point of entry-Function of RIS” and “Coaching” requires that 50% of all supported firms fall within the NRP geographic range (see Figure 3.1). The strategy exempts the programme areas “Control and development of the RIS” and “Intercompany platforms (cluster, networking events)” from this rule.

Still, RIS impact within the NRP perimeter is uneven. Evidence shows that SMEs and entrepreneurs in regional centres benefit more from RIS support than those in more remote regions and mountainous areas (Egli, 2020[16]; SECO, 2020[17]). In view of this, some stakeholders would like to see a redefining and reconsideration of the scale of policy intervention of the NRP. While the success of the NRP is acknowledged in regional centres, more targeted support for very rural regions and a reduction of the NRP perimeter have been part of the political discussion. In opposition, other opinions consider it crucial to include larger agglomerations in the NRP to facilitate knowledge transfer and make use of synergies in spaces that work closer with each other for progressing digitalisation and increased mobility (SECO, 2020[17]).

Table 3.2. Characteristics and bottlenecks of rural innovation

|

Characteristics |

Incremental and slower – less dynamic and short-lived, use of local knowledge for steady improvement |

|

Experimental – utilising space available to test until a solution is found |

|

|

Based on customer or client contacts |

|

|

Smaller firms requiring local leadership and dedication |

|

|

Natural resource focus (tourism, energy, agriculture, forestry) |

|

|

Strong use of social and human capital in innovation |

|

|

Community-driven – meaningfulness as an objective |

|

|

Targeting local markets |

|

|

Use rural-urban links to leverage knowledge outside their location for more radical innovations |

|

|

Bottlenecks |

Dependency on young generations – need for business succession and interest/ability to work on new products and processes |

|

Reduced accessibility of networks, knowledge and support readily available (missing links to universities or research institutions) |

|

|

Lack of digital connectivity and skills |

Source: Mayer, H., A. Habersetzer and R. Meili (2016[18]), “Rural-urban linkages and sustainable regional development: The role of entrepreneurs in linking peripheries and centers”, https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080745; (OECD, 2020[13]; Freshwater et al., 2019[19]; Lee and Rodriguez-Pose, 2012[20]; Jungsberg et al., 2020[21]; Mahroum et al., 2007[22]; Shearmur, Carrincazeaux and Doloreux, 2016[23]; Wojan and Parker, 2017[24])

Box 3.2. Outlook into the RIS 2024+ strategy

In preparation of the new RIS strategic framework for the 2024-31 multiyear programme period, the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) prepared a consultation process to elaborate on this new strategy and identified a couple of key aspects specific to innovation and rural areas. The following points summarise the key elements mentioned by stakeholders taking part in the consultation. Many of them are very much in line with the wider findings of the Rural Well-being Policy Framework and suggest that there is significant potential for the NRP24+ to benefit from the learnings of other OECD countries.

Redefine and reconsider the scale of policy intervention of the NRP. Different geographies have different needs, the biggest differentiations exist between the large agglomerations, regional centres and peripheral regions in Switzerland. Large agglomerations have their own policy and the current NRP policy, and thus its innovation support mechanisms focus on regional centres and peripheral regions. While the success of the NRP is acknowledged in regional centres, it seems to fail to take into consideration that innovation works differently in more rural areas. Some voices demand more targeted support for very rural regions and a reduction of the NRP perimeter. In opposition, other opinions consider it crucial to include larger agglomerations in the NRP to facilitate knowledge transfer and make use of synergies in economic and physical spaces that are growing closer to each other through progressing digitalisation and increased mobility.

Enlarge the concept of innovation present in the NRP. Innovation support has a strong technical focus, while organisational and social innovation is a less prominent part of the NRP. Policies seeking to support innovation at the regional level need to recognise this and adjust their mechanisms accordingly. Suggestions are made to enlarge programmes to include non-technical sectors and work with a broader range of stakeholders on a variety of challenges and solutions, with proposals for a more agile, less risk averse innovation support and increased experimentation potential, for instance through Living Labs testing solutions for the future at the local level.

Complement economic policy objectives in the NRP with social and environmental ones. Economic development can no longer be a single measure of success in times of climate change and demographic challenges. Rural economies are disproportionally affected by demographic decline and ageing and are highly sensitive to climate change effects. Regional policy needs to acknowledge its role in tackling these challenges and opportunities by including new objectives, such as the increased promotion of a circular economy, and better aligning with objectives of other sectoral policies such as climate policy, agricultural policy, social and labour policy.

Further promote digitalisation and digital skills in the NRP. Digitalisation allows firms and entrepreneurs to innovate and bring products to the market no matter where they are. Remote working and flexible work hours further increase the potential for decentralised value creation. Digital ecosystems are suggested as a tool to foster and promote regional transformation processes and already exist in some cantons.

Source: SECO (2020[17]), Weissbuch Regionalpolitik, https://regiosuisse.ch/sites/default/files/2020-07/SECO%20%282020%29%20%C2%ABWeissbuch%20Regionalpolitik%C2%BB.pdf.

Shaping a future-proof vision for innovation that works for Swiss territories, including rural areas

Broadening the concept of innovation

Switzerland’s federal system values cantonal independence, self-determination and local opportunities. In rural regions, there are smaller firms, higher shares of the agricultural, manufacturing and hospitality sectors and a growing services sector (see Chapter 1). While the current agenda for RIS includes a focus on SMEs, the relatively strong institutional focus is on research and development (R&D)-driven innovation. While there is already the possibility of coaching support in the tourism sector and further opportunity to widen the focus, support may be passing by some of the opportunities for innovation in other service sectors.

Despite a focus on bottom-up governance, innovation lacks diversity and is strongly focused on high-technology (high-tech) sectors, even if programmes are open to non-tech firms. The pharmaceutical and precision manufacturing industries are often the targets of innovation policies and programmes.

A large part of the offer of support that the RIS deliver is focused on coaching activities and providing space for SMEs and start-ups to work. RIS Basel-Jura provides different incubator and accelerator programmes that include support in: business plan development, funding, product development, communications, marketing, pricing and intellectual property. It also helps with business’ needs for more than just RIS tasks. It supports and establishes contacts, for example specialists, research institutions or potential co-operation partners, and offer start-ups the opportunity to have their project or business idea reviewed by established industry experts, entrepreneurs and investors. These programmes are accompanied by three co-working spaces in Allschwil, Basel and Delémont (Jura). An overview of the innovation support provided can be found in Table 3.3 below. In addition to these services, digitalisation is seen as a key enabling condition for innovation in businesses (Regio Basiliensis, n.d.[25]).

Similarly, RIS Central Switzerland also offers individual coaching and business support as well as workspaces. Overall, the support is largely technology-focused and seeks to: support the generation of new ideas for products, and sometimes process innovations; provide feedback and insights from experts; help assess technological feasibility, regulatory barriers and market potential; help provide information on access to finance; provide special support and advice on patents and the patent landscape; and implement specific digitalisation programmes in mountainous regions. For example, a programme called Idea Check assesses projects from SMEs that have a maximum of 50 employees and are either based in mountainous regions or have a significant impact in those regions. The projects are assessed by a jury, the winners receive the support of CHF 15 000 (Zentralschweiz innovativ, 2020[26]).

Table 3.3. Basel Area Business & Innovation types of innovation support

|

Focus industries |

Focus area |

Initiatives |

|---|---|---|

|

Biotechnology |

Ecosystem activation and start-up support |

Basel Launch Accelerator and Incubator - Participants have access to funding, expert coaching and infrastructure |

|

Digital health |

Ecosystem activation, start-up support and collaborative projects |

Day One* - Participants have access to funding, expert coaching and infrastructure, fora on topics of value-based healthcare, health data, hospital innovation |

|

Manufacturing and industry |

Ecosystem activation, start-up support and collaborative projects |

i4Challange* - Participants have access to funding, expert coaching and infrastructure, fora and projects on topics including artificial intelligence, robotics, digital transformation |

Note: Further industries can be added in the future. Entrepreneurs, innovators and SMEs are supported in the best way possible according to existing possibilities and competencies. The programmes marked with * are available in Jura.

Source: Regio Basiliensis (n.d.[25]), Interkantonales Umsetzungsprogramm zur Regionalpolitik 2020-2023 der Region Basel-Jura, https://www.regbas.ch/de/assets/File/UP-Basel-Jura_NRP_2020-2023_24_6_2020.pdf.

In Western Switzerland, the RIS also support innovation in a broad sense focusing on business and technological innovation for SMEs and start-ups. The support is carried out by two agencies, Platinn and Alliance. Platinn seeks to develop companies’ business innovation capacity by mobilising them and facilitating their access to innovation and providing coaching in different areas, while Alliance is a knowledge transfer programme whose mission is to develop synergies and set up technological projects between companies and universities or research centres in Western Switzerland, in order to enhance know-how and technology transfer. In addition, they also provide sectoral networking and knowledge exchange platforms in the life sciences (BioAlps), information and digital technologies (Alp ICT), micro‑nanotechnologies (Micronarc) and clean technologies (CleantechAlps).

The support programmes of the RIS largely reflect the economic structure of the cantons as well as their different business fabric. Yet, in particular, rural innovation needs are often only partially reflected, leaving possibilities for improvement. Gaps can be found in catering for established but small businesses that are looking to innovate aside from the technological realm or in opportunities for services that go beyond traditional sectors.

Most RIS seem to conceptualise innovation mainly in technological and product innovation terms. For instance, many programmes are often specific to the high value-added industry within manufacturing industries such as precision watchmaking and pharmaceuticals. Continuously and sustainably growing the manufacturing industry may be a challenge. The Swiss manufacturing industry lost 30 000 jobs and 1 000 firms between 2012 and 2017, equivalent to 2% to 6% of manufacturing jobs in rural, peri-urban and metropolitan areas (see Chapter 1). Furthermore, even though an increasing amount of R&D funding is being spent in the manufacturing sector in metropolitan areas, it did not result in an increase in jobs associated with innovation in 2017, as observed in Chapter 1. In rural and peri-urban areas, there is both a drop in spending and jobs in the manufacturing sector.2

While local ties to precision manufacturing and expertise in the pharmaceutical industry may be an important determinant of current well-being and the logic of choosing high-value sectors is sound for attaining high levels of productivity, it underestimates the rate of change in the economy and overlooks opportunities for the future of industrial arrangements that include new sectors of activities and the importance of adapting traditional economies. For adaptions to pre-existing ways of working, traditional firms can benefit from the “fresh blood” of innovative SMEs through value chain links and strategic partnerships. For the development of diversified sectors, this can include supporting industries with services or encouraging the development of new industries. For example, in rural areas, we observe that increasing expenditures on R&D in the trade and services sector are also coinciding with increasing average jobs in research and expenditure. It is also notable that when R&D firms in rural areas spend funds on innovation, they are more likely to spend them within their own firms. Conversely, a higher share of average R&D spending in firms in metropolitan areas is spent outside the firm, either in other companies in Switzerland or outside Switzerland.

The wish to enlarge the concept of innovation present in the NRP and hence the RIS strategy also comes up in consultations for the new RIS strategy. Stakeholders perceive it as having a strong technical focus while organisational and social innovation are a less prominent part of the NRP. Public consultations have made suggestions to enlarge programmes to further include non-technical sectors and work with a broader range of stakeholders on a variety of challenges and solutions. A more agile, less risk averse innovation support and increased experimentation potential are recommended, for instance through Living Labs testing solutions for the future at the local level (SECO, 2020[17]).

Going forward, the RIS strategy and its implementation need to better recognise that, especially in rural regions, social, process and business model innovations can have positive effects and are needed to secure local well-being and prosperity. Therefore, to better reflect and enhance economic diversity, SECO, in collaboration with other national and regional actors, could lead to developing mechanisms that assure better reflection on needs in different geographies. One option would be to develop a high-level national innovation vision that incorporates experiences in the regional innovation system’s trials, successes and errors, using consultation and agenda-setting with local partners to enlarge the concept of innovation beyond high-tech sectors, to include agriculture and tourism for example.

Future-proofing the innovation agendas

A future-looking approach for rural regions and areas often starts by understanding how current trends are changing society and transforming policy implementation. Future-proofing policy agendas anticipate how economies are changing, often before local entities have the time to react. While governments and individuals cannot anticipate all change, establishing observatories for change and benchmarking institutional performance and financial indicators to carry out projections across regions can help ensure that the government does not inadvertently block change by not reacting fast enough. Subsequently, once trends are identified, innovation support needs to accommodate them and help businesses and societies successfully manage these transformations.

Currently, detecting change and implementing the needs of different geographies happens through a report on territorial megatrends, which is published every four years by the council for spatial planning. The report makes 18 recommendations to the confederation, cantons and municipalities. Findings for 2019 specifically highlight:

Automatising the agricultural industry.

Safeguarding national capital, biodiversity and landscapes.

Digitalisation as a basis for Industry 4.0, autonomous mobility and new modes of work and business.

Service delivery for elderly people especially in rural areas.

Reducing the use of resources and specifically enhancing renewable energy (Council for Spatial Planning, 2019[27]).

However, it is currently unclear how these findings are used to structure the RIS strategy and other innovation support given across territories. It seems that, within the RIS, identified megatrends are largely acted upon under the leadership of individual people or entities but not in a strategic way.

To address this gap, SECO could provide a regional lens for other national innovation outlooks and could, in collaboration with other government departments responsible for innovation at the federal and cantonal levels, reinforce existing monitoring practices, such as the existing regional development monitoring by regiosuisse. It could also contribute to establishing a cross-agency observatory to monitor trends that signal structural change and projected trends within rural regions. An example of a pan-government task force to monitor and anticipate change is available in Box 3.3. This entity should:

Provide guidance for national and regional innovation strategies and agendas.

Be composed of partners from regional and local authorities, academic institutes, the private sector and social partners.

Anticipate change and develop strategies for supporting the transition of current firms in rural areas into new business models.

Encourage adaptability to new market conditions or other global factors such as climate and demographic change, while avoiding over-dependence on traditional industries.

Monitor challenges for women, youth and older workers.

Consider extending and building a rural lens for the current Swiss Perspective 2030 described in Box 3.3.

Promote innovation inside the policy-making process. This can include the adoption of new policy tools (e.g. open government) and re-enforcing the consultation process with non-government actors.

Box 3.3. Strategic foresight and initiatives to anticipate demographic change

Strategic foresight in policy making

Strategic foresight is a thought-driven, planning-oriented process for looking beyond the expected future to inform decision-making. It aims to redirect attention from knowing about the past to exercising prospective judgement about events that have not yet happened. For example, strategic foresight does not claim predictive power but maintains that the future is open to human influence and creativity, with an emphasis – during the thinking and preparation process – on the existence of different alternative possible futures (Wilkinson, 2017[28]). This generates an explicit, contestable and flexible sense of the future, where insight into different possible futures allows the identification of new policy challenges and opportunities and the development of strategies that are robust in the face of change. Some governments have conducted such exercises to define possible future scenarios and adapt public policies.

MetaScan 3, Canada

A possible-scenarios assessment (MetaScan 3: Emerging Technologies) was used by the Canadian government in 2013 to explore how emerging technologies will shape the economy and society, and the challenges and opportunities they will create. The study involved research, consultations and interviews with more than 90 experts. The key findings include some of the following policy challenges:

The next decade could be a period of jobless growth, as new technologies increase productivity with fewer workers.

All economic sectors will be under pressure to adapt or exploit new technologies, in which case having workers with the right skills will be essential.

New technologies are likely to significantly alter infrastructures, forcing governments to decide whether to maintain old infrastructures or switch and invest in new, more efficient ones.

Megatrends analysis and scenario planning, United Kingdom (UK)

In 2013, the UK Government Office for Science launched a plausible scenarios-led foresight assessment (Futures of Cities). The goal of the project was to develop an evidence base for the future of UK cities (challenges and opportunities towards 2065) and to inform national- and city-level policy makers. The office commissioned working papers and essays and conducted interactive workshops, with over 25 UK cities participating. By combining megatrends analysis and scenarios planning, the study imagined a plausible future consisting of considerable climate shocks presenting key urban challenges by 2065 – e.g. drier summers and heatwaves affecting the UK’s southern cities and higher levels of precipitation affecting western cities during the winter.

Perspective 2030, Switzerland

The first step of the Perspective 2030 report by the Federal Chancellery used online questionnaires submitted to experts and think tanks to identify influencing factors, changing trends and megatrends that will impact Switzerland in the next 15 years. During the second step, the surveyed experts assessed the influencing factors and trends by assigning them a value between 1 (low impact/low degree of uncertainty) and 10 (high impact/high degree of uncertainty). Third, the report integrated influencing factors and trends into four different plausible world scenarios that analysed the interaction between the Swiss and international influencing factors as well as the resulting potential “winners” and “losers” for each scenario.

A long-term vision for rural areas, European Commission (EC)

The EC (2021[29]) elaborated its long-term vision for rural areas in the EU up to 2040 following a series of consultations with the public and experts. The long-term vision is accompanied by a Rural Pact and EU Rural Action Plan. The vision identifies: the importance of innovative solutions for service provision and social innovation; the importance of physical and digital infrastructure; resilience to climate change, natural hazards and economic crises; and bringing prosperity through attractivity to companies and digital skills. The EU Rural Action Plan focuses on rural proofing and building a rural observatory for monitoring and supporting the development of the rural action plan.

Science and Technology Foresight Centre, National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP), MEXT, Japan

Looking beyond the next 20 years, the Japanese government is carrying out foresight activities through regional consultations looking into the impact of science and technology on regions in Japan. Involving policy makers across several government ministries, from universities and public research institutes, the business sector, civil society organisations, citizens and international participants, the initiative practices horizon scanning, trend analysis, scenario planning, the Delphi method, visioning and back-casting among other exercises.

The initiative started with a survey to identify trends in science, technology and society by horizon scanning and then created multiple future visions of society (desirable future visions to be realised by 2040) by visioning. Concurrently, 7 disciplinary committees identified 702 medium- to long-term R&D agendas (as “science and technology topics”).

After consulting with more than 5 000 experts to evaluate each topic through the Delphi method, the initiative attempted to extract 8 cross-cutting areas and 8 areas based on 1 or 2 areas (as “close-up science and technology areas”) using mechanical methods and experts’ judgements. Finally, it created 4 conceptual scenarios based on the 50 social visions and 702 science and technology topics. From these, the initiative extracted 16 “close-up” science and technology areas from 702 topics, based on a mechanical process using artificial intelligence-related technology (analysing similarities and clustering topics through natural language processing) and experts’ judgements. Eight areas are considered with high potential for multi/inter-disciplinary and the other eight areas are based on one or two specific fields. These areas are expected to have a possible high impact in solving social issues and/or also serve as common fundamental technologies and systems.

Before the next round, expected in 2024, the initiative plans to conduct several in-depth scenario analyses for several “close-up science and technology areas” defined in the 2019 exercise. It also plans to experiment with new methodologies and outreach by holding several regional workshops.

Anticipating demographic change through a pan-government approach, Population Policy Task Force, Korea

Demographic change has been a major consideration for the Korean government over the past decades, but anticipation and foresight on measures to address how change would impact society started to take a more central role in co-ordination of several related government institutions only towards the end of the 2010s. The initiative to address changes started with a cross-agency commission to measure, plan and take actions to ensure the well-being of individuals across territories.

The Korean Presidential Committee on Ageing Society and Population policy was launched in 2019 to address demographic challenges. As a pan-government initiative, the task force helped provide evidence to promote a co-ordinated approach to strengthen the entire society’s adaptive capacity to the change.

The previous two task forces worked successively, addressing issues related to how projected demographic change would impact policies from April 2019 and July 2020 until January 2021. The first round prepared the government to discuss an extension of the legal retirement age in 2022 from 60 upwards in preparation for the projected 20% of the population that would be 65 and over in the near future. It also resulted in adjusting the supply/demand model for teachers and schools and reforming the military structure and personnel. The second round of consultations targeted initiatives to counteract the hollowing-out of small- and mid-sized regions and included plans for vacant housing and more elderly transport policies.

The issues in the current task force, starting in January 2021, address four major strategies around demographic change and sustainability. They include initiatives on: i) absorbing labour shortage shocks caused by demographic change; ii) responding to the shrinking society; iii) taking pre-emptive action against possible local extinction; and iv) improving the sustainability of the entire society. The strategies target improving opportunities for populations such as women, the elderly, as well as local citizens and the wider public, as defined in Table 3.4.

Table 3.4. Korean Population Task Force goals

How will Korean society change through population policy measures?

|

Women |

Measures to provide more childcare services for families with children in elementary school. |

|

More hours of education for elementary school students; expanded one-stop services for all-day care; better management and supervision for private childcare services. |

|

|

Measures to promote the market for domestic services. |

|

|

Establishment of plans to boost the domestic service market. |

|

|

Measures to reduce the gender gap in the labour market. |

|

|

More aggressive action to improve employment conditions; better disclosure system for indication of gender equality; more incentives for women’s entry to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) areas. |

|

|

Elderly |

Measures to support more opportunities for older individuals to be economically active. |

|

Promotion of discussion on the reform of employment and wage system for the elderly. |

|

|

Measures to increase access to healthcare services to provide the elderly with a healthier life after retirement. |

|

|

Introduction of at-home medical centres; better medical services for patients in vulnerable areas using information and communication technology (ICT); development of non-face-to-face diagnosis/treatment services for the elderly. |

|

|

Measures to extend care services to all individuals for specific needs. |

|

|

Introduction of an integrated assessment system for healthcare, nursing and general care; more supply of care service workers and better service quality. |

|

|

Local citizens |

Measures to incentivise local talent to work in regions for regional development. |

|

Innovation of universities as a regional hub; lifelong vocational education in colleges linked to regional strategic industries; region-specific pilot visa projects to attract skilled foreign nationals. |

|

|

Measures to improve regional hub cities to increase competitiveness up to the level of the capital region. |

|

|

Review of reorganisation of local administrative systems, including the establishment of plans for supra-metropolitan areas and the integration of administrative functions at the regional level. |

|

|

Measures to increase the resilience of regions at risk of depopulation. |

|

|

Joint use of community infrastructure between regions; promotion of specialised regional projects. |

|

|

General public |

Measures to increase opportunities for adult skill upgrading. |

|

Interconnection between lifelong learning services and platforms; operation of various academic programmes and courses for adults at universities. |

|

|

Measures to secure a high degree of protection for platform workers. |

|

|

Promotion of the enactment of the Platform Workers Protection Act and the amendment of the Employment Security Act, the Framework Act on Employment Policy, and Framework Act on Labour Welfare; consideration of a comprehensive protection system. |

|

|

Measures to protect all families without discrimination. |

|

|

Expansion of concept for a family under the Framework Act on Healthy Families; greater support for single-person households; elimination of discrimination in laws and systems. |

|

|

Measures to support the development of skilled workers. |

|

|

Establishment of digital education centres; database setup and transfer of skills and expertise. |

|

|

Measures to support the evidence base for a broad range of other policies. |

|

|

Improvement of demographic statistics infrastructure; composition and operation of a research team for demographic policies. |

Source: Author’s elaboration based on information provided by the Korean Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport and OECD Territorial Review of Korea; Strategic Foresight from OECD (2020[13]), Rural Well-being: Geography of Opportunities, https://doi.org/10.1787/d25cef80-en, adapted from OECD (2019[10]), OECD Regional Outlook 2019: Leveraging Megatrends for Cities and Rural Areas, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264312838-en, using methodology from Wilkinson, A. (2017[28]), Strategic Foresight Primer, European Political Strategy Centre; EC (2021[29]), “Long-term vision for rural areas: For stronger, connected, resilient, prosperous EU rural areas”, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/newsroom/news/2021/06/30-06-2021-long-term-vision-for-rural-areas-for-stronger-connected-resilient-prosperous-eu-rural-areas.

Future-proofing the innovation agendas: Focus on demography

A forward-looking and inclusive innovation policy also needs to address barriers to participation in the labour market and entrepreneurship for under-represented populations, including women, youth and migrants. Increasing diversity, for example by activating female, young and migrant entrepreneurs increases positive outcomes for innovation and has the potential to solve challenges that may impact women and men unequally. For example, one Swiss start-up driven by a young female migrant, studying at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) has built a business based on a circular economy model that breaks down polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic (of which only 9% is recycled every year) at landfills and sells it back to industry. Another example is the start-up Kokoro Lingua, whose female migrant founder provides virtual English language classes for over 100 000 children taught by other children whose native tongue is English. Having started prior to COVID, this start-up was well-positioned to grow when education during lockdowns was transitioned on line.

As observed in Chapter 2, there is a lower rate of females participating in the workforce, where there are two men employed to every woman in low-density peri-urban areas. While the rate is still high in metropolitan regions, it is lower than in most non-metropolitan regions. Rural and peri-urban regions suffer from a loss of opportunities for a competitive and diverse labour market through a lower activation of the female workforce. Thus, there seems to be significant potential for supporting rural women in entrepreneurship by addressing the systemic barriers that many rural women face in growing their businesses. There is a growing understanding that gender-neutral business support measures do not assist women’s enterprise development to the extent that they assist its male equivalent. Yet, no specific objectives for encouraging entrepreneurship and opportunities for women and other harder-to-reach communities are included in the government’s NRP.

Young entrepreneurs have a high potential to innovate. However, given the relatively low share of youth in rural regions, in part due to the pursuit of higher education in denser areas, enjoying the benefits of innovation through young entrepreneurship is limited. According to recent work by the EC and OECD (2020[30]), young people between the ages of 18-30 consider entrepreneurship as a desirable outcome and have a higher potential to be innovative. In European OECD countries, in 23 out of 27 countries for which data is available, young entrepreneurs tend to offer products or services that their customers find to be new and unfamiliar. However, they also tend to report having the knowledge and skills to start a business and have difficulties accessing finance and entering networks, have few role models and low levels of awareness of programmes to support business ventures. The findings are similar to the analysis of characteristics of young start-up entrepreneurs from the upcoming report on Understanding Innovation in Rural Regions (forthcoming[31]).

More inclusive policies might include specific support, for instance through empowering initiatives, knowledge-building activities as well as reforms to correct for market failures in access to government services for all parts of society, including women and youth. Furthermore, there are long argued gains in productivity through more inclusive policies. Improved knowledge of the specifics of women-led or youth-led innovation, more supportive innovation ecosystems and smart solutions coming from women, youth and migrant-led innovations will empower rural people to act for change and get rural communities prepared to achieve positive long-term prospects, including jobs for all, in particular women, youth and migrants. Further guidelines on engaging with youth and women in rural areas are available in Box 3.4.

To achieve this, SECO and the RIS should:

Improve knowledge on women, youth innovation in rural areas and create a better understanding of why the proportion of women in established start-ups is low.

Set objectives for encouraging entrepreneurship and opportunities for women and other harder-to-reach communities in the NRP and develop business support measures targeted to different population groups.

Consider analysing the impact of policies on harder-to-reach populations such as women, older workers and younger workers in the monitoring and evaluation strategy.

Establish a gender strategy within the RIS structure to evaluate how programme policies can better accommodate female entrepreneurs and workers in STEM.

Establish a youth strategy within the RIS structure to evaluate how programme policies can better accommodate young entrepreneurs.

Box 3.4. Support for women and youth in rural regions

Women’s entrepreneurship, South of Scotland Enterprise, Scotland (UK)

Building a new strategy for Scotland’s newest regional development agency, South of Scotland Enterprise (SOSE), presents opportunities for new thinking and approaches to regional, place-based development. With no previous record of delivering programmes, much of the leg work is still in the works. It was particularly disabled by the challenges of starting a new agency during COVID. SOSE are nevertheless looking to the future, beyond recovery efforts, and acting now to deliver transformational change. One of the key components of their regional innovation strategy under the head of the innovation and entrepreneurship unit is establishing new programmes specifically to address the needs of female entrepreneurs and barriers they encounter in accessing business support. The process is currently underway.

Women Entrepreneurship Strategy (WES), Canada

The Canadian Department for Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) estimates that by ensuring the full and equal participation of women in the economy, Canada could add up to CAD 150 billion in gross domestic product (GDP). With only 17% of Canadian small- and medium-sized businesses owned by women, the government of Canada developed a WES with CAD 6 billion in investments and commitments to encourage access to finance, talent, networks and expertise. It includes an Inclusive Women Venture Capital Initiative, a Women Entrepreneurship Loan Fund, an Ecosystem Fund and the Women Entrepreneurship Knowledge Hub. Other similar programmes exist in the form of a Women Entrepreneur programme administered by Farm Credit Canada, a Women in Technology Venture Fund, a Women Entrepreneurs programme administered by the Business Development Bank of Canada and a Women in Trade programme administered by Export Development Canada.

Regional development agencies (RDAs) in Canada, such as ACOA, FedDev Ontario, PrairiesCan, PacifiCan and provinces across Canada provide specific support, consulting and advisory services to women. They deliver two aspects of the WES:

1. The Women Entrepreneur Fund (WEF) provides non-repayable contributions of up to CAD 100 000 to support women-owned and women-led businesses to scale/grow and reach new markets (programme completed).

2. The WES Ecosystem Fund, a National and Regional fund, is a four-year programme that runs until March 2023. Notably, the fund:

Provides non-repayable contributions to non-for-profit partners that deliver business services and support programming to women entrepreneurs.

Included an additional top-up to support women entrepreneurs to navigate the COVID-19 crisis.

Through WES, the RDAs seek to increase the number of women-owned and -led businesses and strengthen capacity within the entrepreneurship ecosystem and close gaps in service for women entrepreneurs.

The Women’s Enterprise Initiative is an example of a distinct Canadian regional programme that addresses the challenges that women entrepreneurs face. The initiative, in partnership with PrairiesCan and PacifiCan, helps women entrepreneurs start, scale up and grow their businesses. There is a Women’s Enterprise Initiative organisation in each of the four Canadian western provinces (Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan). These non-profit organisations provide a variety of unique products for women entrepreneurs, including business advisory services, training, networking opportunities, loans and referrals to complementary services (Government of Canada, 2021[32]; 2021[33]).

Funding diversity, United States (US)

The regional offices of the US Department of Commerce engage and activate programmes specifically to support female-run and minority entrepreneurs, including Indigenous and black entrepreneurs.

In the US, programmes are developed through the Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA) to help provide access to working capital and gap financing for women and minority communities. The MBDA is a federal agency solely dedicated to the growth and global competitiveness of minority businesses. In addition, the Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration provides revolving loan funds (RLFs) to help bring access to capital and gap financing for minority-run firms, in addition to community development financial institutions (CDFIs) that help find and sponsor funding for rural communities.

Guidelines for attracting and retaining skilled young population in rural areas, US

According to the US Rural Policy Research Institute (RUPRI) and the associated programme Energizing Young Entrepreneurs (EYE), rural communities can promote a series of actions to benefit from the full potential of their young population:

Invest time and resources in youth priorities and make communities more attractive for young people to live, work and develop activities.

Improve the school-to-job transition by strengthening interactions between regional higher education institutions and firms.

Map the community’s assets in order to match educational and training programmes with career opportunities.

Promote the development of a good business framework able to offer small business ownership and high-level job opportunities to young people.

Provide entrepreneurial education within the school systems or as an extracurricular training programme, in which students can meet local entrepreneurs and gain hands-on knowledge.

Offer access to technical assistance and business coaching for young entrepreneurs.

Consult and involve young people in every phase of the economic activities in the region, to develop a sense of ownership and vested interest in their communities.

Source: OECD (2012[34]), OECD Territorial Reviews: Småland-Blekinge, Sweden 2012, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264169517-en; OECD (2012[35]), OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation: Central and Southern Denmark 2012, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264178748-en; RUPRI Centre for Rural Entrepreneurship; e2 Entrepreneurial Ecosystems (n.d.[36]), Homepage, www.energizingentrepreneurs.org (accessed on 19 Augest 2022); U.S. Department of Commerce (2022[37]), “Women-Owned and Indigenous Small Businesses Thrive with EDA and MBDA Support”, https://www.commerce.gov/news/blog/2022/03/women-owned-and-indigenous-small-businesses-thrive-eda-and-mbda-support; Government of Canada (2022[38]), Women Entrepreneurship Strategy, https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/women-entrepreneurship-strategy/en.

Future-proofing the innovation agendas: Focus on climate change

Transitioning to a zero-carbon economy and adjusting to climate change implications is the task of this century. Switzerland has set itself the goal to become climate neutral by 2050. Overall, rural regions are pivotal in the transition to a net-zero-emission economy and building resilience to climate change because of their natural endowments. Many rural economies (e.g. agriculture, forestry, tourism, energy, etc.) are already suffering from the increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as storms, floods, torrents and landslides. In many rural regions across the world, increasing heat waves will contribute to water scarcity, with risks to food production. As nature loses its capacity to provide important services, rural economies will suffer significant losses as they rely on the direct extraction of resources from forests, agricultural land or the provision of ecosystem services such as healthy soils, clean water, pollination and a stable climate (OECD, 2021[39]).

Transitioning to net-zero will require a massive deployment of alternative energy technologies as well as new technologies that are not yet on the market or are currently in the demonstration or prototype phase. This means that significant innovation efforts must take place this decade in order to bring these new technologies to market (IEA, 2021[40]). Many of these innovations will need to occur in rural regions where their renewable energy can be generated from sun, wind and water and where there is massive potential to develop the circular economy and bioeconomy. Supporting innovation in these areas not only diversifies ongoing business activities, it can also create new businesses while contributing to environmental and climate protection.

The private sector, and particularly SMEs, are considered a potential driving force for the zero-emission transition – notably through innovation in their products and processes. Product innovations include design that replaces non-renewable materials and resources with renewable, recycled, permanent, biodegradable, non-hazardous and compostable materials and resources; and processes innovation involves the recreating processes, so that products are made to be more easily disassembled, recycled, modular (replacement of parts, recovery and reuse of systems and sub-systems) and repairable (OECD, 2020[41]).

In Switzerland, the circular economy has also gained in importance, especially through various parliamentary initiatives, interpellations and postulates that have been developed in recent years. Furthermore, at the federal level, a first National Research Programme (NRP 73) aims to combine research on all natural resources, all stages of the value chain and the integration of the environment, economy and society. A number of projects include a focus on the circular economy. Legal framework conditions for fostering a circular economy are still under discussion in the Swiss parliament3 and the federal administration for the environment is in charge. More grassroots and private initiatives have also emerged. For example, in 2018, the initiative Circular Economy Switzerland was launched, supported by the MAVA Foundation and the Migros Group. The initiative aims to promote the circular economy in Switzerland with various projects and events such as a circular economy incubator, in which 27 Swiss start-ups are supported in building a more circular Switzerland (regiosuisse, n.d.[42]). At the regional scale, regiosuisse has developed a toolbox aiming to support regions, municipalities or cities in advancing on circular economy. The toolbox offers a methodological framework, inspiration, assistance and practical tips. The toolbox is set up in a modular structure or, depending on interests, consulted selectively (regiosuisse, n.d.[43]).

By providing the right support, RIS have the potential to become enablers of the net-zero transition and attaining climate objectives. Currently, climate change and the way businesses can move to more sustainable, less-emitting ways of doing business only marginally feature in the RIS programming (mostly events) and strategy.

There is great potential for the future NRP and RIS strategies to put greater emphasis on innovation that can advance climate change mitigation and adaptation. This can be done by:

Adapting RIS coaching to feature business support on innovation for climate change: preparing businesses to assess possible climate risks (physical, price, product, regulation), improving energy and waste efficiency in their businesses and across value chains, and helping them to source power from renewable resources or minimising waste, saving energy, water and materials, recycling and reusing materials or waste, while offering green products and services.