Tajikistan has one main body involved in investment promotion, and several other government bodies that also have roles to play in this field. Investment promotion is primarily in the hands of the SCISPM, which is responsible for the design and implementation of investment policy, and Tajinvest, a state unitary enterprise supervised by the SCISPM. At the same time, it is the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade that designs policies related to free economic zones (FEZ), which are part of the investment promotion system. It is also the same Ministry that conducts FEZ-specific investment promotion activities, such as organising events and roundtables with investors to which it invites the SCISPM and Tajinvest. Similarly, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Industry and Innovative Technologies, alongside business associations, organise investment promotion events that seek to attract investment in their sectors. Like FEZs, regional investment promotion bodies occasionally help organise promotion events and assist investors in their dedicated regions. To conduct policy advocacy and support public-private dialogue on investment, the government has also put in place the Consultative Council on Improvement of Investment Climate, which the SCISPM chairs.

The SCISPM currently has 12 mandates, which is more than the average number of mandates of agencies in charge of investment promotion in Eurasia (6.5) and the OECD (5.7) (OECD, 2020[27]). Besides foreign investment promotion, the SCISPM is responsible for managing state enterprises, privatisation, supporting SMEs and entrepreneurship, and, since 2018, hosting a business incubator. Tajinvest is charged more narrowly with investment promotion, but in practice currently primarily provides business development services (BDS) to domestic companies (Tajinvest, 2021; OECD interviews, 2021).

The SCISPM is the parent agency, and it has significantly greater statutory powers. According to its government-approved charter, it plays a leading role in designing investment policy, independently negotiates agreements with investors, provides all necessary documents and permissions for investors through a single-window system, defends the legal interests of investors, proactively attracts investments, and co-ordinates investments with other government agencies (Government of the Republic of Tajikistan, 2006[55]).Tajinvest is only able to advise investors (on legal aspects, tax legislation, operational and business issues) and implement policies adopted by the SCISPM. Investors are under the impression that the SCISPM is responsible for public investment, whereas Tajinvest handles private investment, but this distinction is not enshrined in law and indeed contradicts the SCISPM’s mandate to attract and assist all investors (OECD interviews, 2021).

Organisational reforms may have contributed to this confusion about mandates and tasks. While the allocation of roles and responsibilities may be clear to officials in the relevant bodies, investors report being unsure about, for example, whom to contact in legislative matters related to their investments. The SCISPM, established in 2006, has gone through five reorganisations in the past ten years. These have involved additional mandates, particularly the mandate to be a single-window as of 2017. While it is critical that investment promotion institutions adapt to a changing policy environment, a measure of institutional stability is essential to reducing confusion among investors and effective long-term planning. Responses to the OECD IPA survey show that organisational reforms are rather common in Eurasia, reflecting changes in government and the need to adapt to new economic realities. It is thus no surprise that IPAs in Eurasia see “the instability or inadequacy of their mandates” as their number one challenge (OECD, 2020[27]).

While the SCISPM’s many mandates, from privatisation to SME development, may bear synergies with investment promotion, it is important to ensure that the resources allocated to the SCISPM match its diverse and broad responsibilities. Tajinvest has increasingly shifted its focus towards supporting domestic business development (trainings, advisory services), activities that are financially more promising but still generate insufficient income to ensure the capacity to reach out to investors and promote the country effectively (UNCTAD, 2016[26]).

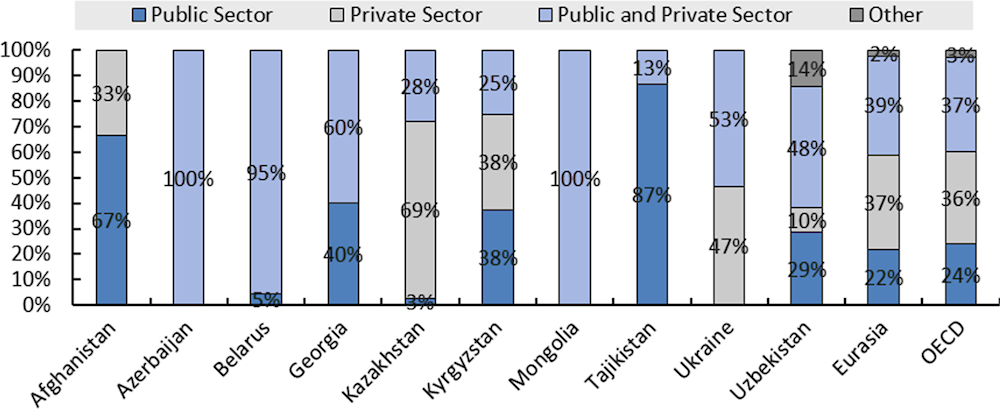

In addition, Tajikistan could benefit greatly from improvements in the skills and experience of IPA employees, especially private-sector experience. Staff with a public sector background comprise 87% of SCISPM and Tajinvest (Figure 6), which may affect the Committee’s capabilities in areas where private-sector experience is an advantage (UNCTAD, 2016[26]; OECD, 2020[27]). Level of experience and length of tenure also matter. Interviews indicated that staff turnover is high, affecting the ease with which staff can build relationships with investors and ensure continuity of the activities. The interviews also suggest that salary levels may contribute to high turnover and make recruitment from the private sector harder. Tajik government stakeholders rank inadequate staff as a major challenge (OECD, 2020[27]). Recruitment mechanisms may also need to be considered; it may be useful to advertise opportunities in non-governmental job forums.