This chapter evaluates the impact of self-motivated training on the employment, earnings and occupational mobility of its participants. The impact of SMT participation on changes in occupational quality is also explored. To account for the selection of participants into the programme, the counterfactual impact evaluation deploys a propensity score matching methodology. The estimated effects are examined across sub-groups of unemployed based on their age, gender, education level and urban or rural location. A large lock-in effect is observed, as participants delay job search for education, however, employment levels recover over the longer term. Self-motivated training does not lead, on average, to moves up the occupational ladder. Women and older individuals benefit more on average from self-motivated training relative to their counterparts.

Evaluation of Active Labour Market Policies in Finland

5. Evaluation of self-motivated training

Abstract

5.1. Introduction

Introduced in Finland in 2010, self-motivated training (SMT) allows jobseekers to enroll in formal education while keeping their unemployment benefits for up to two years. This chapter presents the results of the impact evaluation of the programme, that is, its impact on the outcomes of jobseekers that participate in this programme relative to similar jobseekers who did not participate in SMT but could have benefited from other PES services and programmes.1 The sample studied consists of jobseekers with an ongoing unemployment spell at the end of years 2012‑14. Labour market outcomes (as defined in Chapter 4) are measured from one to four years after this point. After describing the characteristics of participants in SMT, the discussion focuses on the impact of the programme on the employment probability and on earned income. It then explores the impact of SMT on occupational mobility. In both cases, it uses the methodology described in Chapter 4 of this report. This chapter also shows the effects of the programme across different subgroups of the population based on their age, gender, education level and urban or rural location. It then links the results found to previous literature on SMT. The chapter ends with a conclusion section.

5.2. Participants in self-motivated training are compared to a control group obtained through propensity score matching

Individuals who enrol in SMT have different profiles from unemployed individuals who do not participate in it (Table 1.1, columns 1 and 2). Among participants in SMT there is a higher proportion of women (+16 percentage points) and unmarried individuals (+6 percentage points). SMT participants are on average seven years younger than other jobseekers and have more children. SMT participants are also less likely to live in rural areas (‑4 percentage points) and alone (‑4 percentage points). The level of education is not significantly higher for participants. However, the fields of study differ considerably. General programmes (+4 percentage points) and arts and humanities degrees (+4 percentage points), which are fields where studies are often interrupted, are overrepresented, while engineering diplomas (‑13 percentage points) are underrepresented. Similarly, regarding professions prior to SMT participation (for those who had a job), SMT participants are more likely to work in the service and sales industry (+7 percentage points) and less likely to work in craft and related trades (‑10 percentage points) or as operators and assemblers (‑3 percentage points). Finally, the number of spells and days spent in unemployment over the past (two) year(s) is lower for participants.

This descriptive analysis implies that there is a high degree of self-selection in the programme. This justifies not trying to evaluate SMT by simply comparing its participants and non-participants, because they are not comparable (columns 1 and 2 of Table 1.1). As discussed in Chapter 4, propensity score matching is used to overcome this selection issue. It generates a control group of jobseekers (column 3 of Table 1.1) who are more comparable to SMT participants across observable characteristics than all other jobseekers.

Table 5.1. Participants and non-participants in self-motivated training differ considerably

Comparison of observable characteristics by treatment status

|

Jobseeker’s characteristics |

Participants in SMT (treated) |

Non-participants in SMT (unmatched) |

Control individuals (matched) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

History in unemployment |

|

|

|

|

Unemployment duration until 31 December (in the current spell) |

180.66 |

275.10 (***) |

175.99(*) |

|

Number of unemployment spells in previous year |

1.13 |

1.20 (***) |

1.18 |

|

Number of days in unemployment in previous year |

84.44 |

89.52 (***) |

86.96 |

|

Number of unemployment spells in previous 2 years |

1.87 |

2.02 (***) |

1.92 |

|

Number of days in unemployment in previous 2 years |

161.45 |

179.45 (***) |

164.90 |

|

Demographic characteristics |

|||

|

Finnish national |

0.97 |

0.97 (***) |

0.97 |

|

Woman |

0.58 |

0.42 (***) |

0.57 |

|

Age |

36.36 |

43.17 (***) |

35.87 (***) |

|

Number of children |

1.01 |

0.68 (***) |

0.99 |

|

Car ownership |

0.49 |

0.58 (***) |

0.49 |

|

Marital status |

|||

|

Unmarried |

0.51 |

0.45 (***) |

0.52 (**) |

|

Married |

0.37 |

0.38 (***) |

0.36 |

|

Divorced |

0.13 |

0.16 (***) |

0.12 (**) |

|

Widowed |

0.01 |

0.01 (***) |

0.00 |

|

Status in the family |

|||

|

Not belonging to a family |

0.27 |

0.31 (***) |

0.27 |

|

Head of the family |

0.23 |

0.25 (***) |

0.23 |

|

Spouse |

0.22 |

0.16 (***) |

0.22 |

|

Child |

0.04 |

0.06 (***) |

0.04 |

|

Head of cohabiting family |

0.10 |

0.11 (***) |

0.10 |

|

Spouse of cohabiting family |

0.13 |

0.09 (***) |

0.13 |

|

Unknown |

0.01 |

0.02 (***) |

0.02 |

|

Type of housing |

|||

|

Detached house |

0.36 |

0.42 (***) |

0.35 |

|

Terraced house |

0.15 |

0.13 (***) |

0.15 |

|

Block of flats |

0.46 |

0.41 (***) |

0.47 |

|

Other building |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

|

Living alone |

0.23 |

0.27 (***) |

0.23 |

|

Municipality type |

|||

|

Urban |

0.75 |

0.70 (***) |

0.75 |

|

Semi urban |

0.14 |

0.16 (***) |

0.13 |

|

Rural |

0.11 |

0.15 (***) |

0.11 |

|

Language |

|||

|

Finnish |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

|

Swedish |

0.02 |

0.03 (***) |

0.02 |

|

Other |

0.08 |

0.07 (***) |

0.08 |

|

Level of education |

|||

|

Upper secondary or less |

0.54 |

0.55 |

0.54 |

|

Post-secondary non tertiary education |

0.01 |

0.01(***) |

0.01 |

|

Short cycle tertiary education |

0.08 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

|

Bachelors or equivalent |

0.12 |

0.10 (***) |

0.12 |

|

Masters or equivalent |

0.07 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

|

Doctoral or equivalent |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

|

Unknown |

0.17 |

0.19 (***) |

0.17 |

|

Field of education |

|||

|

General programmes |

0.09 |

0.05 (***) |

0.09 |

|

Education (Teacher training and education science) |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

|

Arts and humanities |

0.09 |

0.05 (***) |

0.09 |

|

Social sciences |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

|

Business |

0.14 |

0.12 (***) |

0.14 |

|

Natural sciences |

0.02 |

0.01 (***) |

0.02 (*) |

|

ICT |

0.05 |

0.03 (***) |

0.05 |

|

Engineering |

0.18 |

0.31 (***) |

0.18 |

|

Agriculture |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

|

Health and welfare |

0.08 |

0.07 (***) |

0.08 (*) |

|

Services |

0.13 |

0.11 (***) |

0.13 |

|

Unknown |

0.18 |

0.20 (***) |

0.18 |

|

Profession of previous occupation |

|||

|

Armed forces |

0.00 |

0.00 (***) |

0.00 |

|

Managers |

0.01 |

0.02 (***) |

0.01 |

|

Professionals |

0.13 |

0.11 (***) |

0.13 |

|

Clerical support |

0.08 |

0.06 (***) |

0.08 |

|

Service and sales |

0.29 |

0.22 (***) |

0.29 |

|

Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

|

Craft and related trades |

0.12 |

0.22 (***) |

0.13 |

|

Operators and assemblers |

0.09 |

0.12 (***) |

0.09 |

|

Elementary occupations |

0.12 |

0.13 |

0.13 |

|

Number of observations |

13 766 |

356 947 |

13 121 |

SMT: Self-Motivated Training.

Note: *, ** and *** represent a p-value bellow 01; 0.05; and 0.01, respectively. They are displayed for the T-test on the differences between columns 2 and 1 and between columns 3 and 1. Unmatched refers to all unemployed individuals in the sample that do not participate in SMT while matched refers to the individuals identified as comparable to the participants in SMT through nearest-neighbour propensity score matching. This table includes individuals unemployed 31 December 2012, 2013 and 2014 for whom we observe the outcomes of interest (employment status, earnings and occupation) the year before and the four following years.

Within fields of education, general programmes include: basic general programmes (pre‑primary, elementary, primary, secondary, etc.); simple and functional literacy and numeracy; and personal development.

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Finland’s repository: FOLK and TEM datasets.

5.3. Self-motivated training has positive employment effects in the long term

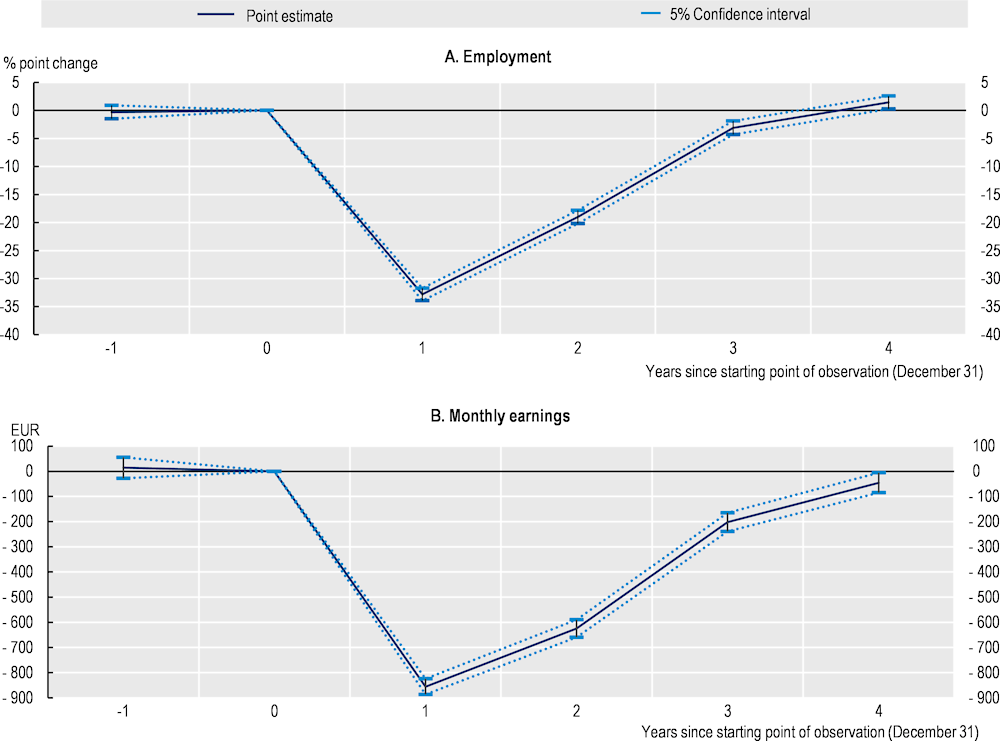

The estimation results show that SMT has a strong negative effect on the probability of being employed in the first years that follow the beginning of the programme by its participants (Figure 1.1, Panel A). This negative effect reaches a peak the year of the start of the programme (recall that this corresponds more precisely to 31 December of the year the programme takes place2). At this point, unemployed individuals who participated in the programme (the treated group) are around 33 percentage points less likely to be employed than those who did not participate (control group). Afterwards, this effect diminishes but remains negative during more than two years. Nevertheless, three years after the start of SMT (four years from the starting point of observation) the effect on employment becomes positive (1.4 percentage points) and is statistically significant.

The initially negative effect reflects the so-called “lock-in” effects, which means that participants in SMT do not engage in job search and may not be willing to accept a job until they have completed their training and obtained their qualification.

The estimated effects on monthly earnings also reflect this lock-in effect (Figure 1.1, Panel B). One year after the start of SMT, participants earn on average EUR 855 less than similar individuals in the control group. However, unlike results for employment these results do not become positive during the observation period in this report. Even if considerably smaller in magnitude (EUR ‑45) the effect on monthly earnings remains negative even at four years from the starting observation point.

Figure 5.1. Self-motivated training has strong lock-in effects in the short term and positive employment effects in the long term

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on several characteristics: duration in unemployment until the point of observation, history in unemployment over the past two years (spells and days), age, gender, marital status, education level and field, Finnish national, type of municipality, type of building, quarter of registration into unemployment (time trend), as well as previous year employment status, earnings and occupational quality (rank). The confidence intervals are shown at the 5% level of significance and represented by the whiskers delimiting the dotted lines on the charts. Outcomes are observed at the end of each calendar year (31 December). Year zero is the first year in the sample and identifies the pool of people that are unemployed at the end of that year. All training takes place in year one (therefore between points zero and one in the graph). Other years are relative to this.

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Finland’s repository: FOLK and TEM datasets.

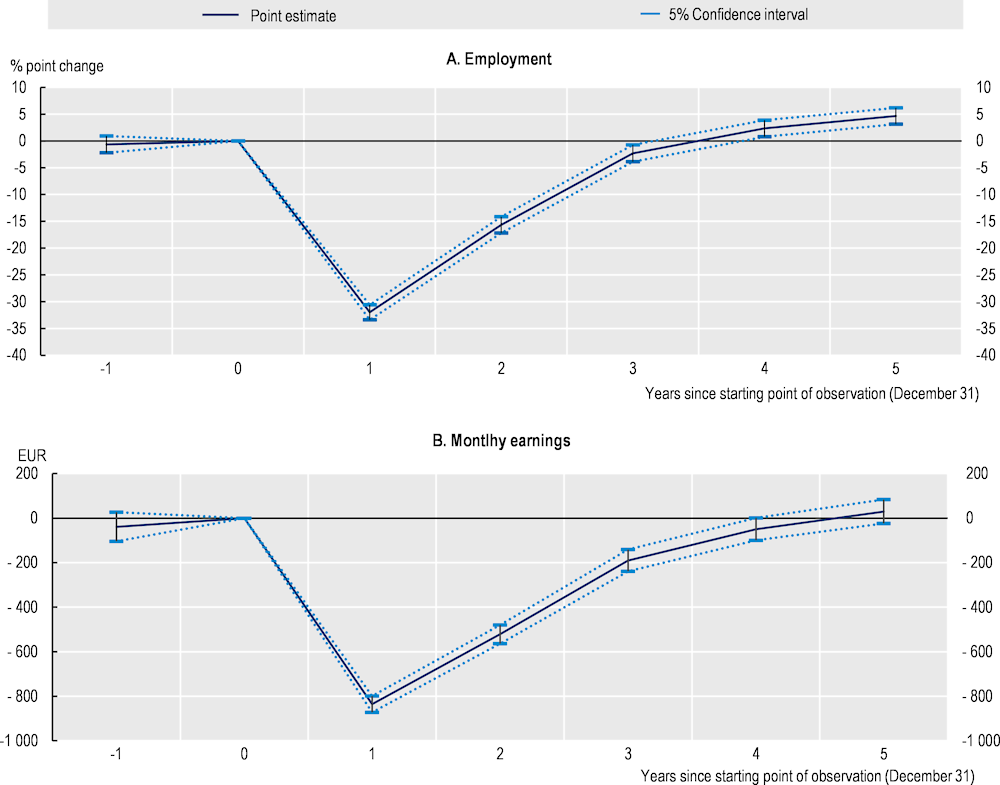

The median of the estimates on the probability of being employed, found by other studies in the international literature at a similar time horizon, is 5 percentage points (ranging from ‑2 to 25 percentage points) (Card, Kluve and Weber, 2018[1]). The effect found for SMT is thus more modest but consistent with the fact that the programme can last up to 24 months (see Chapter 4), while classical LMTs are usually shorter. Furthermore, this smaller effect could also relate to the fact that classical LMT are by design more oriented towards labour market integration while SMT concerns formal education. To test whether the smaller effects found on employment and earnings after three years from the start of SMT are due to the larger lock-in imposed by formal studies, the same estimation was run on a smaller sample of unemployed for whom we can observe these outcomes over one more year (Annex Figure 1.A.1). Indeed, participants in SMT belonging to the 2012‑13 cohort of jobseekers experience larger effects in terms of both employment and earnings after four years than after three years from the start of the programme. Four years after the start of the programme, the effects on the employment probability are twice as high as the previous year and the effect on earnings is no longer negative.

5.4. Self-motivated training has slightly negative average effects on upward occupational mobility but stimulates a change in the distribution

SMT allows jobseekers to pursue a full-time degree at an education institution. Obtaining a new degree might encourage jobseekers to explore different career paths and creates opportunities to access new occupations with better employment opportunities. This section first measures if SMT participants (that is treated jobseekers) are more likely to change occupations and if they end up in better quality occupations than the one of their previous employments as compared to their control counterparts (that is those who did not participate in SMT). It then explores if this average effect is linked to important changes in the distribution of occupations.

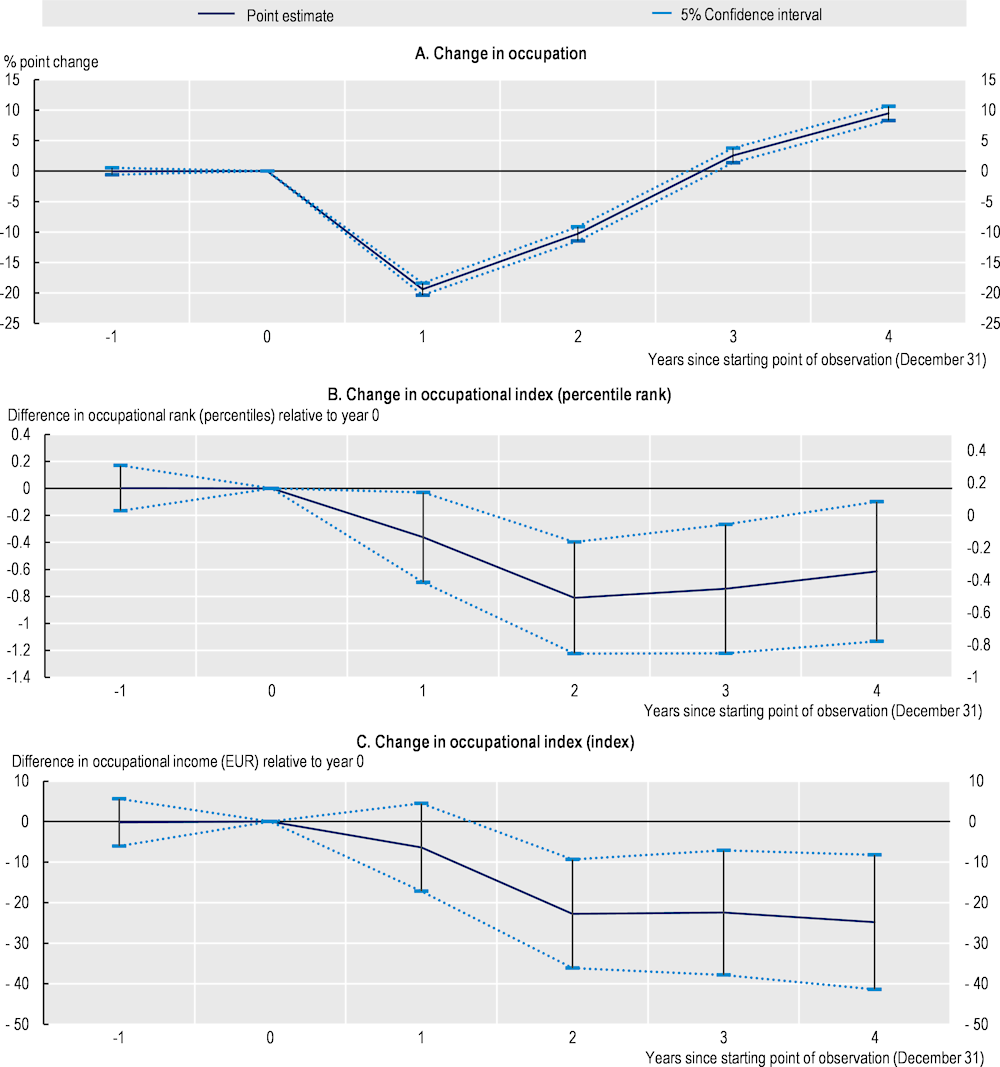

The estimation shows positive and sizeable effects of SMT on the probability of changing occupations (Figure 1.2, Panel A). Two years after the start of SMT (three years from the starting point of observation), SMT participants are around 2.6 percentage points more likely to have changed occupations relative to the one of their previous employments as compared to non-participants. This estimate goes up to 10 percentage points at four years from the starting observation point.

Participants in SMT are more likely to change occupations, but on average they move to lower quality occupations than non-participants (Figure 1.2, Panels B and C). Here, the outcome of interest is the difference between the quality of the last occupation known in a given year (years one to four) and the quality of the occupation of jobseekers’ previous employment at the starting observation point (year zero). As explained in Chapter 4, the quality of occupations is measured by an occupational index that builds on Finnish data on earnings at the occupation level from 2010 to 2018. It measures quality both as a percentile rank and in monetary units (occupational earnings in euros). The estimation shows slightly negative effects on upward occupational mobility for SMT participants that are persistent over time. The difference in the occupational index between year four and the staring observation point is around 0.6 percentage points lower for individuals benefiting from SMT than for similar individuals in the control group (Figure 1.2, Panel B). SMT participants end up in occupations that pay on average EUR 25 less per month than their previous occupation as compared to non-SMT participants (Figure 1.2, Panel C).

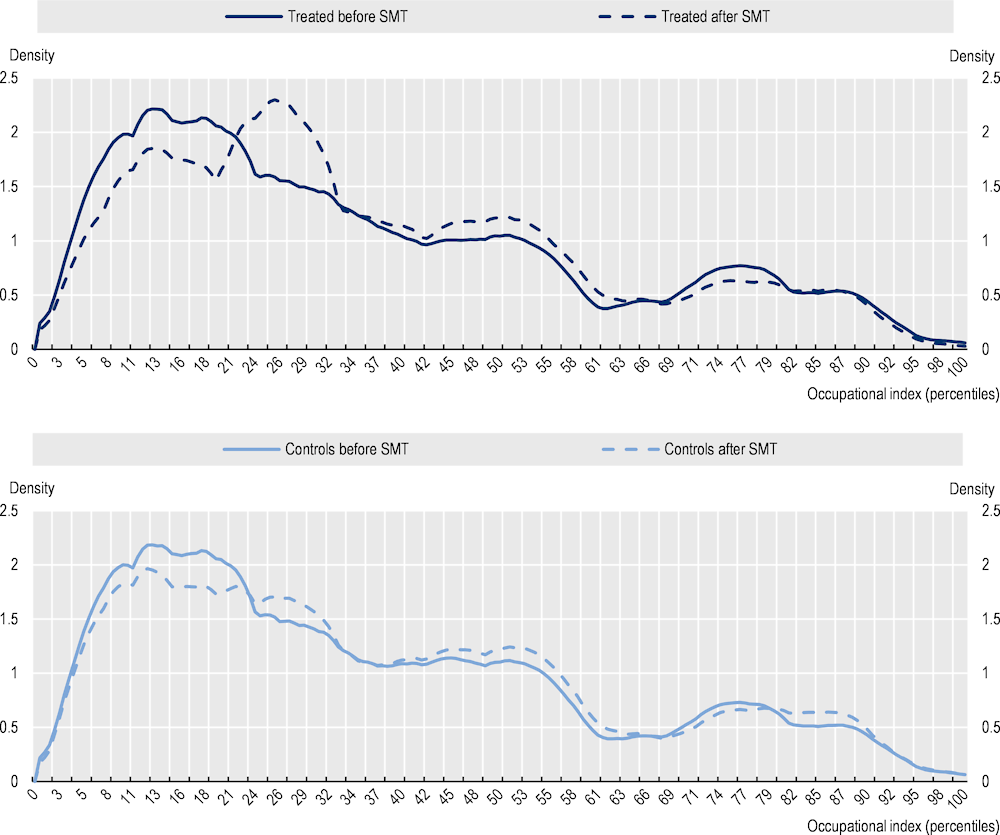

This slight negative effect on upward occupational mobility is an average effect that does not tell much about how SMT changed the shape of the distribution of occupations. This effect could come from a homogenous shift along the distribution, but different tails of the distribution could also be disproportionately affected. To explore the distributional effect of SMT, Annex 5.A plots the distribution of the occupational index (in percentiles) of SMT participants and non-participants respectively, at the starting point of observation (before SMT participation) and four years after this point (three years after SMT starts).

Between the starting point of observation and four years after this date, lower-ranked occupations (between the 6th and the 24th percentile) are slightly less represented among non-participants while some middle‑low, middle and middle‑top occupations become marginally more frequent. The distribution of occupations for SMT participants experienced stronger changes. As compared to non-participants, lower-ranked occupations end up even more underrepresented, there is a higher boost in middle‑low (from around the 24th to the 34th percentile) and middle occupations, and a slight decrease in middle‑top occupations (70th to 80th percentile). All in all, these results suggest that the null average effect of SMT participation on the occupational ladder is aggregating a decrease in the frequency of bottom and top occupations in favour of occupations in the middle of the distribution.

Figure 5.2. Self-motivated training increases the chances of changing occupation but with slightly negative effects on upward occupational mobility

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on several characteristics: duration in unemployment until the point of observation, history in unemployment over the past two years (spells and days), age, gender, marital status, education level and field, Finnish national, type of municipality, type of building, quarter of registration into unemployment (time trend), as well as previous year employment status, earnings and occupational quality (rank). The confidence intervals are shown at the 5% level of significance and represented by the whiskers delimiting the dotted lines on the charts.

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Finland’s repository: FOLK and TEM datasets.

5.5. Women and older individuals benefit more from self-motivated training and high educated individuals lose in terms of job quality

While the results presented in the previous section have focussed on the aggregate effects of SMT, this section provides separate estimates across subgroups of unemployed. Studying whether the effect of SMT differs between subgroups of the population gives insight on how the programme acts on individuals and allows to better understand the mechanisms behind its impact. Furthermore, by identifying for whom the policy works and for whom it does not, such analysis could inform the targeting, but also it could lead to redesigning the programme to increase its effectiveness. The sample is divided along several jobseeker characteristics: (i) gender, (ii) age, (iii) level of education and (vi) urban vs. rural municipality of residence.

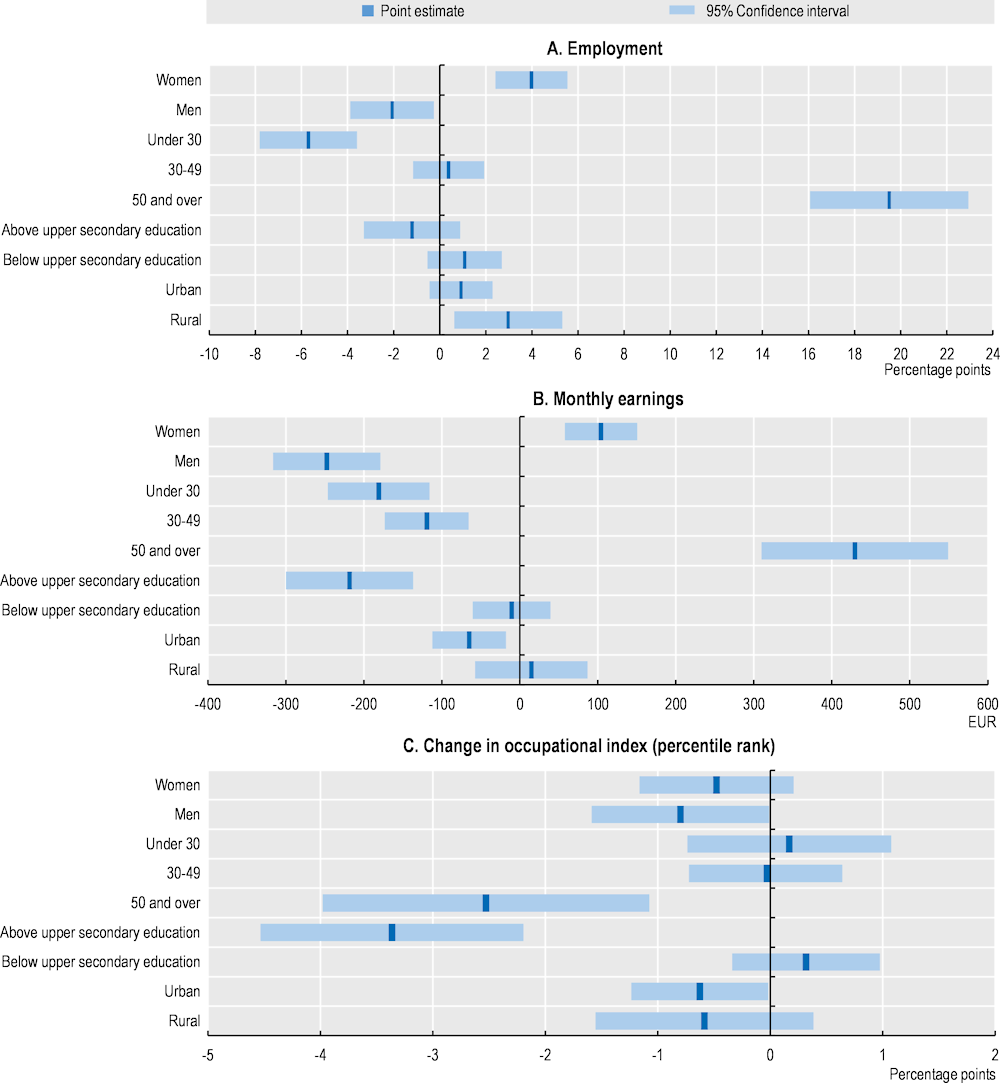

Women seem to benefit more from SMT than men. Three years after the start of the programme (four years from the starting point of observation), the effect on employment and earnings is positive and significant for women (4 percentage points and EUR 104 respectively) and negative for men (‑2 percentage points and EUR ‑248) (Figure 1.3, Panels A and B). In terms of upward occupational mobility, both men and women experience an almost null effect (Figure 1.3, Panel C). Thus, regarding gender, SMT is already attracting individuals more likely to benefit from it since women are more likely to participate (Section 5.2). This result echoes the meta‑analysis conducted by Card, Kluve and Weber (Card, Kluve and Weber, 2018[1]) in which the authors find that programmes targeted at women are more effective than the average programme or programmes targeted towards men.

The results also vary by age. Individuals aged 50 and over are the subgroup of the population for whom the effects of SMT on employment and earnings are the largest (19.5 percentage points and EUR 429). On the other hand, for individuals under 50 and above 30 the effects on employment are not statistically significant and the effects on earnings are negative (EUR ‑119), and, for individuals below 30 the effects are strongly negative for both employment and earnings (‑3 percentage points and EUR 181). Therefore, even if younger jobseekers are more likely to enrol in the programme, older jobseekers benefit the most from it. Furthermore, in terms of upward occupational mobility individuals 50 and over exhibit a negative effect (‑2.5 percentage points). Thus, older jobseekers improve their probability of having a job through SMT participation but while doing so, they move on average into lower quality occupations than those they held prior to participation.

The effects of SMT on the probability of employment do not differ substantially by the education level of jobseekers. However, the effects on the quality of the jobs found both in terms of earnings and upward occupational mobility is negative for individuals with a level of education above upper-secondary (EUR ‑218 and ‑3.4 percentage points). SMT allows jobseekers to enrol in formal education and to obtain a degree above upper secondary education. These results suggest that the upskilling generated by SMT has better results in terms of the quality of the job obtained when it allows jobseekers to get their first above upper secondary diploma. Jobseekers who already possess such a diploma seem to be moving down the job ladder following SMT participation.

Finally, regarding the type of municipality of residence, individuals living in rural municipalities seem to enjoy more positive results than those in urban locations in terms of employment, earnings and occupational mobility although the differences are not statistically significant.

Figure 5.3. Estimated effects of self-motivated training, four years after the starting observation point, by jobseeker characteristics

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on several characteristics: duration in unemployment until the point of observation, history in unemployment over the past two years (spells and days), age, gender, marital status, education level and field, Finnish national, type of municipality, type of building, quarter of registration into unemployment (time trend), as well as previous year employment status, earnings and occupational quality (rank).

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Finland’s repository: FOLK and TEM datasets.

5.6. The results of this evaluation complete previous literature on self-motivated training in Finland

The relatively recent introduction of SMT means that studies on its impact on labour market outcomes are scant. This evaluation completes previous literature that was until now mostly descriptive or inconclusive.

Larja and Räisänen (2020[2]) perform a descriptive analysis that details the evolution of the programme and the types of individuals it attracts. They find that SMT are typically long, with an average of 413 days. This is to be expected given the type of training that individuals participate in and its maximum duration of 24 months. This duration does not vary by age. The most common occupational type was unknown (suggesting either recent graduates or immigrants without a Finnish work history), followed by health and care workers. The authors looked at training uptake by labour supply of occupations and found some consistency, with those workers in industries with lower labour shortages more likely to participate in retraining (consistent with searching for better job prospects). However, some industries did not conform to this dynamic. For example, those in restaurants and construction looking to retrain even as there are labour shortages in such industries. This may be explained by the relatively low pay and poor working conditions in those industries, relative to others. (Aho et al., 2018[3]) perform an exercise to match SMT participants to non-participants and are inconclusive in their findings. They find employment outcomes that are higher for individuals starting SMT after one or six months of unemployment, but not for those that start after 12 months of employment. They attribute the larger impact seen for the cohort starting after six months of unemployment to unobserved selection bias.

5.7. Conclusion

SMT presents positive long-term effects on employment. The fact that these effects are smaller than other programmes in the literature can be partly explained by the larger lock-in effects induced by the return to education for a period longer than classical LMT. Expanding the window of observation of this study would plausibly lead to observe higher magnitude effects over the following years. These smaller effects could also come from the smaller labour market policy component of SMT as compared to LMT. Moreover, individuals in the control group could have benefited from other PES services and programmes. However, testing whether the stronger lock-in effects come from differences the design of the programmes goes beyond the scope of this study. More data should be gathered on the length and content of SMT to unveil the mechanisms behind the effects found.

On average, SMT does not positively impact upward mobility. Nevertheless, it does affect the shape of the distribution of occupational quality: from bottom and top occupations towards occupations in the middle of the distribution. This raises the question of what the objective of policy makers should be: designing programmes that improve the quality of jobs on average or programmes that reduce inequalities in job quality leading to a more concentrated distribution of occupations?

SMT effects vary across subgroups of the populations and benefits more women and older individuals while decreasing the quality of jobs for individuals with an above secondary level of education. While women are more likely to participate in SMT than men, SMT participants are on average younger and more educated than the rest of the unemployed. Efforts could be made to encourage the groups of the population that are more likely to benefit from it to increase their participation in SMT.

References

[3] Aho, S. et al. (2018), Työvoimapalvelujen kohdistuminen ja niihin osallistuvien työllistyminen.

[1] Card, D., J. Kluve and A. Weber (2018), “What Works? A Meta Analysis of Recent Active Labor Market Program Evaluations”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 16/3, pp. 894‑931, https://doi.org/10.1093/JEEA/JVX028.

[2] Larja, L. and H. Räisänen (2020), Omaehtoinen opiskelöu työttömyysetuudella., TEM-analyyseja 99/2020.

Annex 5.A. Additional figures

Annex Figure 5.A.1. SMT effects increase after an initial lock-in period

Note: The sample is restricted to individuals having an ongoing unemployment spell at the end of years 2012‑13.The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on several characteristics: duration in unemployment until the point of observation, history in unemployment over the past two years (spells and days), age, gender, marital status, education level and field, Finnish national, the type of municipality, the type of building, the quarter of registration into unemployment (time trend), as well as previous year employment status, earnings and occupational quality (rank). The confidence intervals are shown at the 5% level of significance and represented by the whiskers delimiting the dotted lines on the charts. Outcomes are observed at the end of each calendar year (31 December). Year zero is the first year in the sample and identifies the pool of people that are unemployed at the end of that year. All training takes place in year one (therefore between points zero and one in the graph). Other years are relative to this.

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Finland’s repository: FOLK and TEM datasets.

Annex Figure 5.A.2. Effect of self-motivated training along the distribution of the occupational index by treatment status

Note: The heights of the lines indicate the relative share of individuals in occupations whose index in percentiles are on the horizontal axis. This figure compares treatment and control distributions in years 0 (before) and 4 (after).

The two sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for equality of the distribution of the occupational index between treated and control groups leads to a p-value of 0.015 before SMT, and of 0.000 after SMT.

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Finland’s repository: FOLK and TEM datasets.

Notes

← 1. Note that the control group is identified from the universe of jobseekers in the final sample. The sample was not restricted to jobseekers that did not benefit from any other service as these individuals are likely to have very specific characteristics and not be representative of the population of interest, leading to potential selection issues.

← 2. Outcomes are observed at the end of each calendar year (31 December). Year zero is the first year in the sample and identifies the pool of people that are unemployed at the end of that year. All training takes place in year one. Other years are relative to this. For example, year four identifies outcomes four years after first observing an individual as unemployed, but three years after having participated in training.