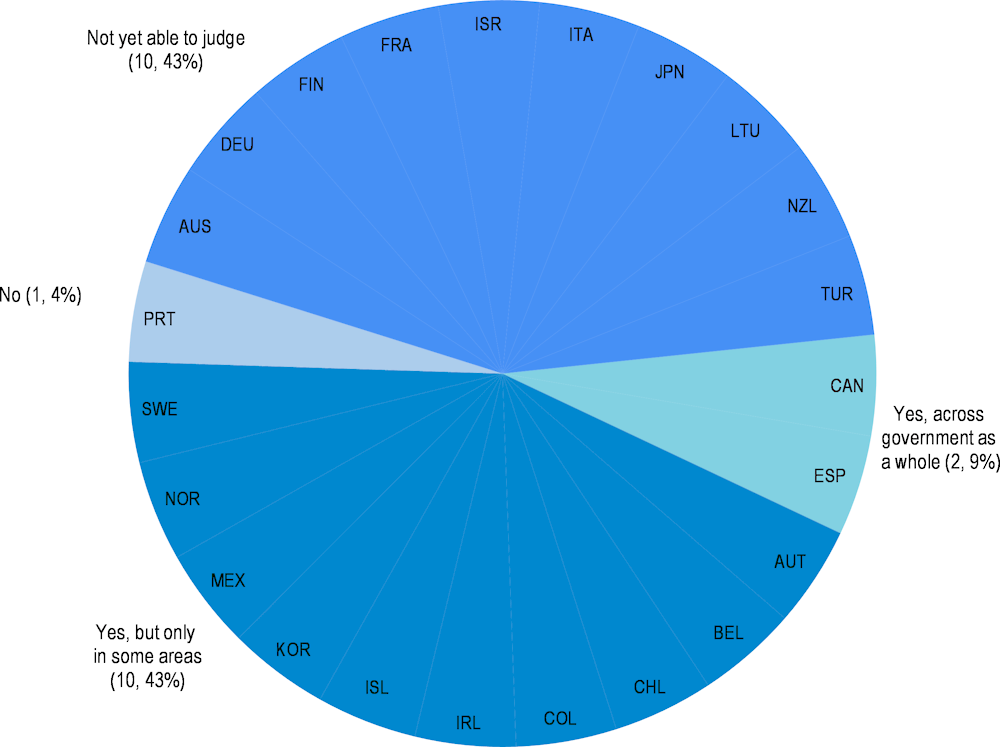

Results from the 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting (referred to as the “2022 survey” hereinafter) show an increase in the number of OECD countries practicing gender budgeting. In 2022, 23 out of 38 OECD countries had introduced gender budgeting measures (61%), compared to 17 out 34 in 2018 (50%) and 12 out of 34 in 2016 (35%) (Figure 2.1).

Gender Budgeting in OECD Countries 2023

2. Gender budgeting across the OECD

Overview of gender budgeting across the OECD

Figure 2.1. Growing use of gender budgeting in OECD countries, 2016-22

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 1; 2018 OECD Budget Practices and Procedures Survey; 2016 OECD Survey of Gender Budgeting.

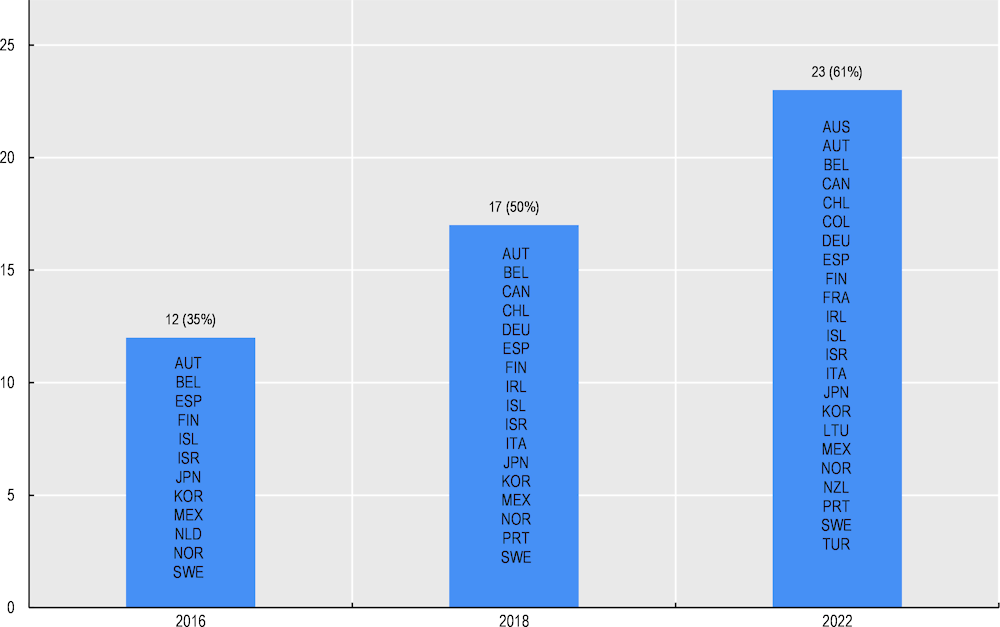

Some OECD countries have a relatively longstanding gender budgeting practice, such as Norway (2005), Finland (2006), Mexico (2006), Korea (2006), Iceland (2009), Spain (2009) and Austria (2009) (Sharp and Broomhill, 2013[2]; Downes, von Trapp and Nicol, 2017[3]; OECD, 2014, p. 192[4]). Countries that introduced/reintroduced gender budgeting since 2018 include Australia, Colombia, France, Lithuania, New Zealand and Türkiye (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2. Status of gender budgeting across OECD countries, 2022

Notes: “Planned” refers to the situation where the introduction of gender budgeting is foreseen whereas “Actively considering” refers to the situation where the introduction of gender budgeting is being deliberated.

At the time of the 2022 survey New Zealand introduced gender budgeting on a pilot basis. New Zealand is now progressing gender budgeting on a year-by-year basis.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Questions 1 and 2.

Both OECD countries that have recently implemented gender budgeting and those with an established practice are considering further developing their approach in the future. Australia and New Zealand had initiated pilots at the time of the survey and are now continuing the introduction of ex ante gender impact assessment in policy development, decision making, and across the budget as a whole (Australian Government, 2023, p. 13[5]). Lithuania and Türkiye have recently introduced gender budgeting as part of their performance budgeting frameworks and are working to further develop effective measures to track progress.

Of the countries that do not implement gender budgeting, one OECD country, Costa Rica, has concrete plans to implement it in the future (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Future plans to implement gender budgeting in Costa Rica

Costa Rica has indicated plans to introduce a budget with a gender lens in partnership with the International Monetary Fund and the Council of Ministers of Finance of Central America, Panama and the Dominican Republic, but a defined work schedule for implementation has not yet been set. Since 2019, Costa Rica has used a methodology developed by the National Institute for Women to estimate the country’s investment in gender equality for the fulfillment of Sustainable Development Goal 5, tracked against institutional targets inscribed in the National Plan for Development and Public Investment. Guidelines, instruments and criteria on the application of the methodology across planning and public budgeting are being developed by the Ministry of Finance, as well as instruments to gather gender-disaggregated data.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting.

In addition, Luxembourg, Latvia and Slovenia are actively considering the implementation of gender budgeting. Detail concerning gender budgeting pre-planning undertaken in Latvia is provided in Box 2.2.

Box 2.2. Gender budgeting pre-planning in Latvia

Latvia conducted a gender budgeting pilot project in 2017, including a review of gender impact analysis measures implemented to date, finding insufficient data disaggregated by gender and public service knowledge and interest to analyse the impact of the budget through a gender perspective. Review recommendations included amendments to ministerial instructions on the analysis of the state budget requiring information on gender equality performance indicators in the annual report on the results of the state budget. With a view to conduct analysis of the gender-disaggregated budget outputs and performance indicators of three ministries and central public institutions, as per the National Plan on the Promotion of Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men 2021-2023, Latvia intends to raise awareness across the public service of the benefits of gender budgeting through the dissemination of information and provision of training and broader capacity building initiatives across state and local government institutions. The aim is to integrate equal opportunities and non-discrimination principles into policy planning, implementation and evaluation processes by 2028.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting.

Also among the countries that do not practice gender budgeting, five reported the existence of gender mainstreaming processes to ensure gender equality is considered in the development of policies (Luxembourg) and decision making (United Kingdom),1 the drafting of legislation (Denmark and the Netherlands) and performance setting (Greece). Although these processes have not been identified as gender budgeting measures, they may still impact public spending decisions in terms of gender equality.

Institutional and strategic arrangements

Gender budgeting requires a strong institutional and strategic framework (Gatt Rapa and Nicol, 2023, forthcoming[1]).This section outlines institutional and strategic arrangements in place across OECD countries practicing gender budgeting. In particular, the discussion illustrates the growing efforts being made across the OECD to ensure gender budgeting practices are sustainable and being effectively applied and co-ordinated to achieve high priority gender equality objectives.

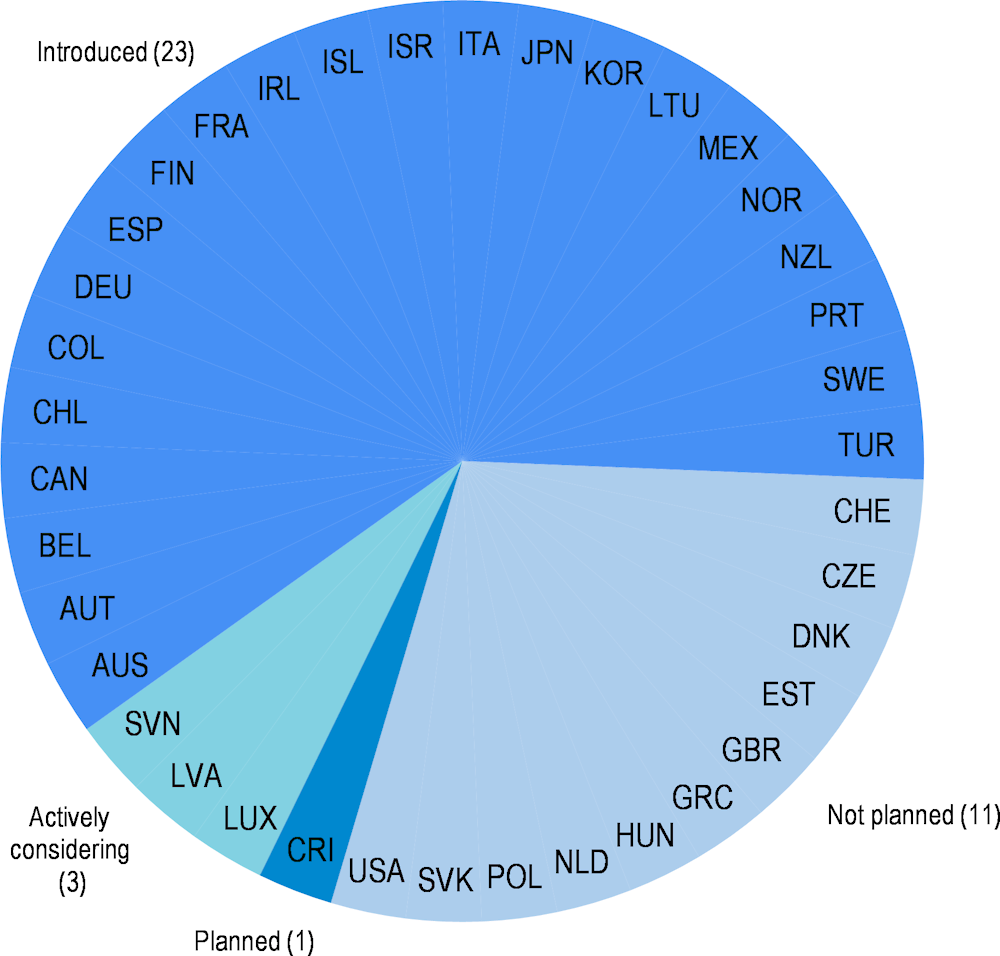

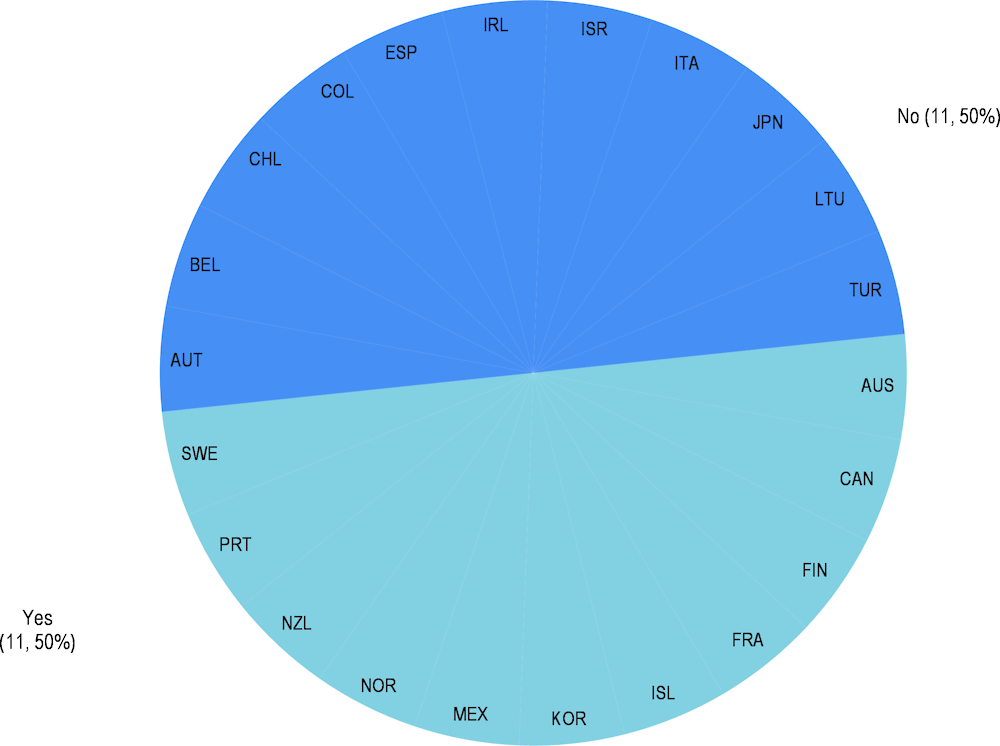

Legal basis for gender budgeting

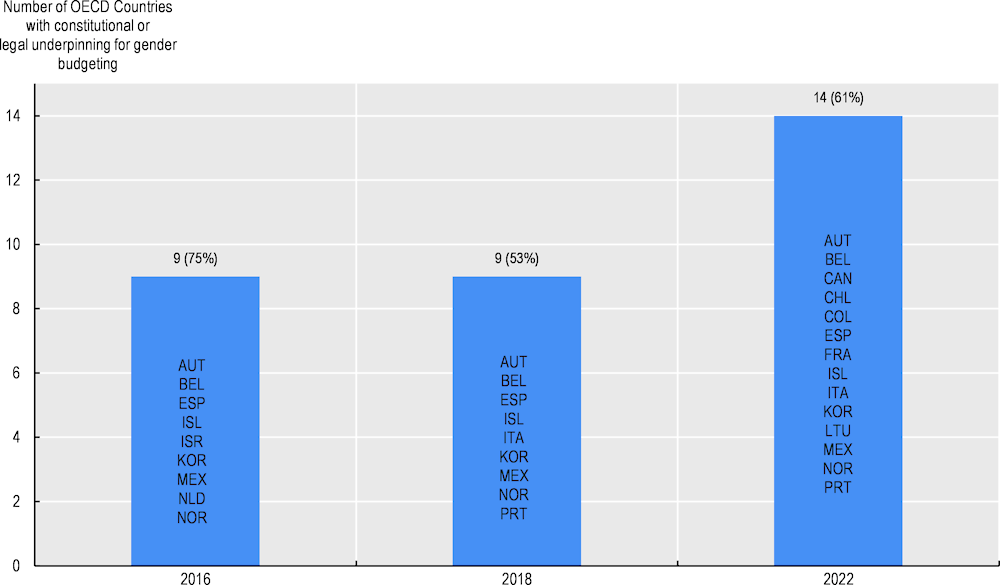

A legal basis for gender budgeting can safeguard its implementation through insulating the practice from economic and political fluctuations (OECD, 2023[6]). A legal underpinning can also encourage engagement with governments, parliaments and Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) through the establishment of effective leadership arrangements, strong governance structures and co-ordination mechanisms, and scrutiny and oversight functions for gender budgeting practices. In 2022, gender budgeting had legal underpinning in 14 out of 23 OECD countries, compared to 9 out of 17 in 2018 and 9 out of 12 in 2016 (Figure 2.3). The percentage of OECD countries which have legal underpinning for gender budgeting has fluctuated in recent years, mainly reflecting the increase in gender budgeting adoption with countries having recently introduced gender budgeting not yet having obtained legal authority for the practice.

Figure 2.3. OECD countries with legal underpinning for gender budgeting, 2016-22

Note: Although the number of countries is the same in 2016 and 2018, the composition is not identical. This is likely to be due to a lack of continuity in survey responses over time.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 6; 2018 OECD Budget Practices and Procedures Survey; 2016 OECD Survey of Gender Budgeting.

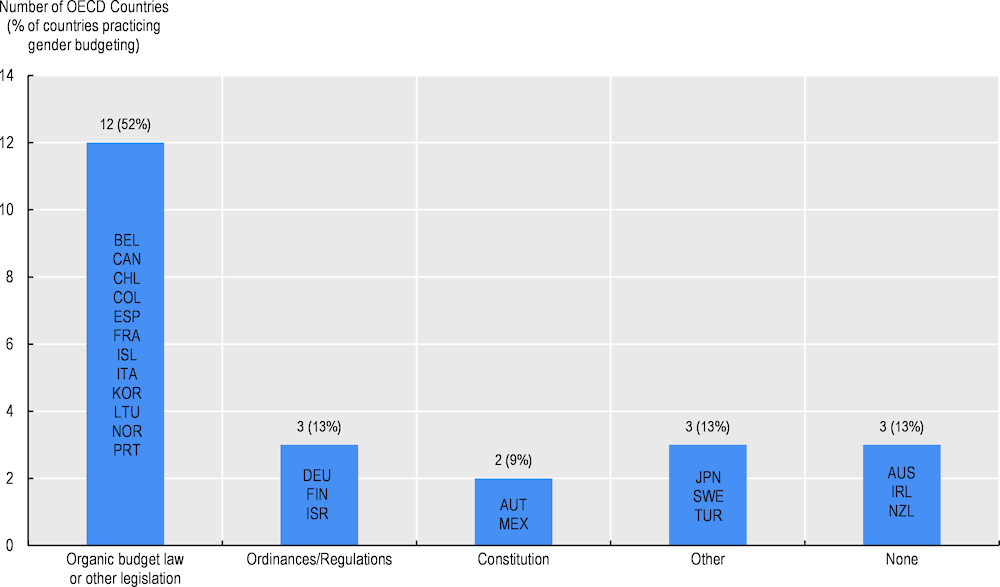

The highest authority for conducting gender budgeting in 2022 varies across OECD countries (Figure 2.4). Constitutional authority provides the strongest underpinning for gender budgeting; however, it is uncommon with constitutional provisions in just two OECD countries (Austria and Mexico). Around a quarter of countries practising gender budgeting have provisions set out in the Organic Budget Law (26%), while 13% of OECD countries practicing gender budgeting do so without a legal basis. For example, two OECD countries with relatively longstanding gender budgeting practices – Japan and Sweden – reported still obtaining authority for gender budgeting through high level political commitment/convention in 2022. The gender budgeting practices of Germany, Finland and Israel are solely authorised by Ordinances/Regulations in 2022.

In some countries, the authority for conducting gender budgeting has strengthened over time. For example, in Spain gender budgeting was initially underpinned by provisions requiring a Gender Budgeting Report in the Organic Law for Effective Equality between Women and Men (2007) but this requirement has since been incorporated into the General Budget Law in 2020. Finland’s approach to gender budgeting was initially underpinned by administrative practice (Budget Circular), while in 2022 Ordinances/Regulations for gender budgeting had been implemented.

In about a third of OECD countries that practice gender budgeting, the highest authority is provided by other legislation (26%), including legislation relating to gender equality, gender mainstreaming, or specifically gender budgeting. For example, Belgium obtains its authority for gender budgeting through its 2017 gender mainstreaming legislation aimed at monitoring the application of the resolutions from the world conference on women held in Beijing in September 1995 and at integrating the gender perspective into the whole of the federal policies. Of the OECD countries that have introduced a legal basis for gender budgeting since 2018, Canada and Colombia provide examples of the varying nature of enacted obligations (Box 2.3).

Figure 2.4. The highest authority for practising gender budgeting across OECD countries, 2022

Box 2.3. Examples of legal obligations for gender budgeting in Canada, Colombia and Spain

Canada

The Canadian Gender Budgeting Act 2018 commits the Government of Canada to strengthen its financial administration by ensuring gender and diversity is considered in budgetary decisions. Under the Act, the Minister of Finance and the President of the Treasury Board must publicly report on the outcomes of gender impact assessments of all budget measures, tax exemptions and expenditure programmes to enhance transparency and accountability.

Colombia

Legislation implemented in 2019 establishing the 2018-2022 National Development Plan (Pact for Colombia, Pact for Equity), requires budgetary authorities to annually submit a report of the budget allocations aimed at guaranteeing the equity of women identified by the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit through budget tracing/tagging to the Congress of the Republic.

Spain

The Spanish Constitution, established in 1978, explicitly declares the equality of all individuals and prohibits any form of discrimination. In 2007, the Organic Law for effective equality between women and men was enacted, imposing an obligation on public administrations to prepare gender impact reports for any proposed law, plan, or project requiring government approval. This commitment includes the preparation of a Gender Budgeting Report alongside the annual State Budget. To further strengthen the implementation of gender budgeting, this obligation was incorporated into the General Budget Law in 2020 through the amendment of its Article 37.2.

Source: Canadian Gender Budgeting Act S.C. 2018, c. 27, s. 314; Government of Colombia (2019, pp. 5-6[7]), “Budget Tracer for Women’s Equity: A guide to the inclusion of the gender approach for women in the public policy cycle”; Spain – direct communication.

Policy direction for gender budgeting

A strong approach to gender budgeting benefits from clearly stated gender equality objectives identifying key areas of focus for government action (OECD, 2023[6]). These may be incorporated into broader performance or outcomes frameworks that establish overarching and holistic accountability and transparency methodologies to track progress relating to the high-level government strategic priorities. Clear gender equality strategies and objectives help direct gender budgeting efforts as well as better-target budget choices.

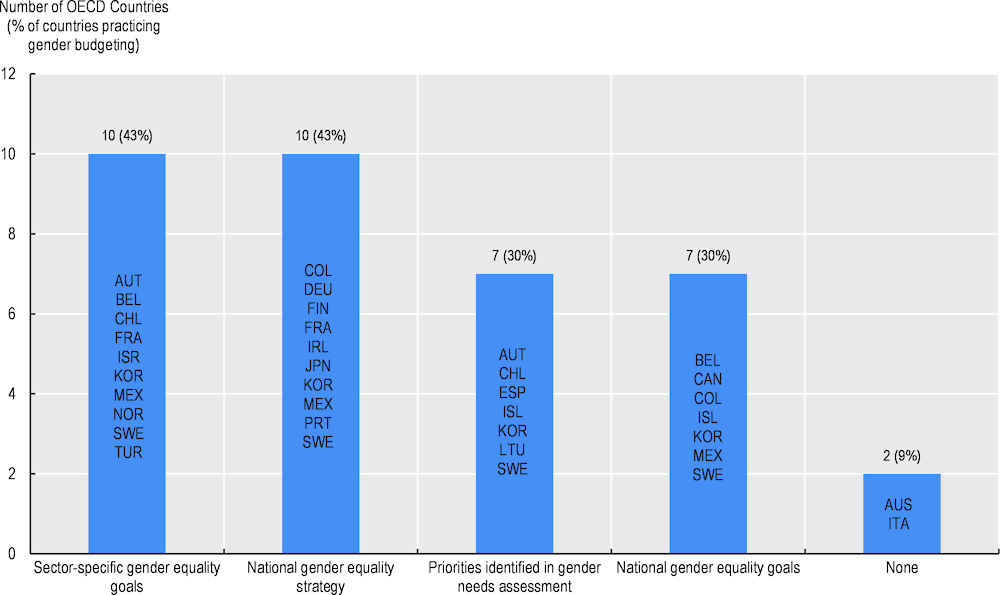

In 2022, 91% of OECD countries undertaking gender budgeting had implemented a variety of strategic arrangements to guide initiatives (Figure 2.5). The most common policy methods directing gender budgeting efforts are sector specific (e.g. education, housing) and national gender equality goals, established in 43% of countries respectively. Strategic priorities identified in gender needs assessment and national gender equality goals are used to guide gender budgeting in 30% of countries respectively (see Box 2.4 for the example of Iceland). Only two countries practice gender budgeting with no policies guiding gender budgeting (Australia and Italy). When describing challenges relating to implementation, Austria highlights not having a gender equality strategy in place impacting co-operation across government in relation to gender budgeting.

Box 2.4. Strategic policy direction for gender budgeting in Iceland

Gender budgeting in Iceland is guided through national gender equality goals outlined in Equality Legislation and fiscal and gender equality action plans, as well regularly performed and published gender equality needs assessments. The Government of Iceland maps the status of gender equality across policy domains and identifies targeted objectives and actions to address challenges. Government departments are required to set gender priorities through medium term planning and provide evidence on how these objectives will be addressed through the budget. Gender impact assessments of new budget measures have been conducted since 2020, with the results included in information provided to decision makers within the administration, the cabinet and in Parliament and published in the Budget Bill.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting.

Figure 2.5. Policy direction for gender budgeting comes in a variety of forms, 2022

Institutional arrangements for gender budgeting

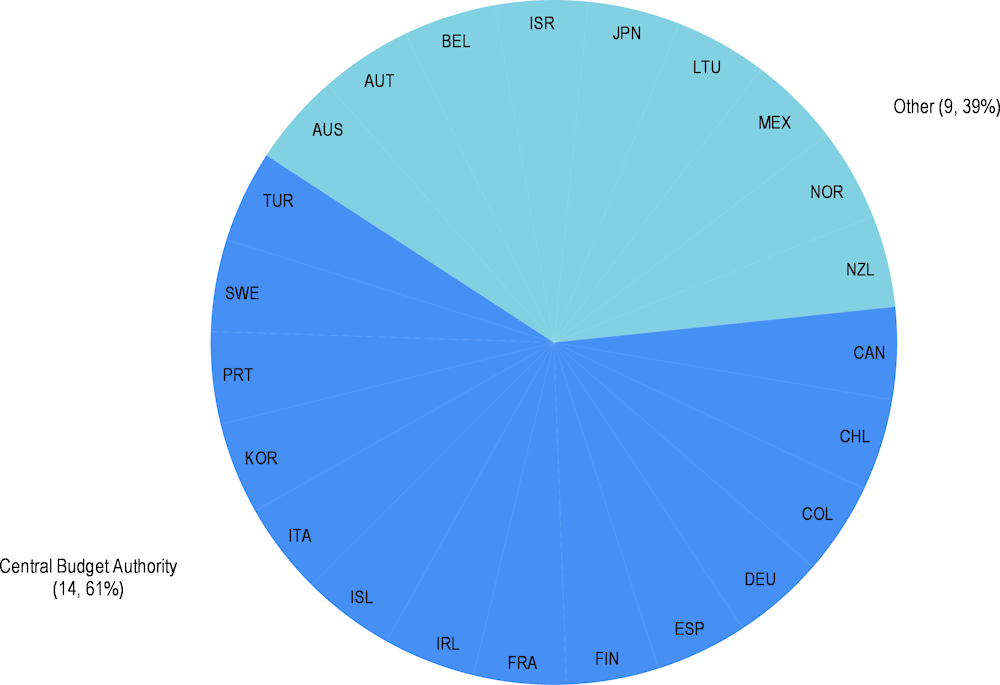

Clear institutional arrangements support a strong strategic framework for gender budgeting. This includes the identification of the most appropriate government authority to lead practices. In 2022, 61% of OECD countries reported that their gender budgeting practice was led by the Central Budget Authority (CBA) (Figure 2.6), up from 35% in 2018. An approach to gender budgeting led by the CBA can have positive impacts on the quality of evidence gathered from methods and tools, due to the considerable influence that the CBA has over resource allocation, government-wide policymaking and the achievement of policy goals.

Figure 2.6. Institution with lead responsibility for gender budgeting, 2022

Note: The “Other” category includes countries where leadership for gender budgeting is shared between the CBA and another part of government.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 5.

Where responsibility for gender budgeting is shared with the CBA and one or more government institutions in 2022, this often includes the Central Gender (Equality) Institution (CGI) mandated to advance gender equality policy (Austria, Israel, Lithuania, Norway, New Zealand). In 2022, Belgium indicated that main responsibility for gender budgeting resided with line ministries. Mexico also indicated that line ministries lead gender budgeting, with other institutions including the Ministry of Finance and the CGI (Inmujeres - National Institute for Women) playing a supporting role. In Japan, although the budget is formulated by the CBA, gender equality initiatives are under the authority of the Gender Equality Bureau of the Cabinet Office.

The establishment of an inter-agency working group led by the CBA and including stakeholders from across government can also strengthen the implementation of gender budgeting through providing a vehicle for communication and co-ordination. In 2018, 23% of countries had an inter-agency group on gender budgeting (Belgium, Spain, Iceland, Sweden), increasing to 30% of countries in 2022. Since 2018, Canada, Korea and Ireland have established inter-agency groups, with Ireland’s group being established simultaneously with the introduction of equality budgeting (Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. Inter-agency working group to support equality budgeting in Ireland

A pilot initiative for equality budgeting was announced in Ireland as part of the 2018 Budget. Since then, all 18 government departments in Ireland are participating in equality budgeting through setting targets relating to equality objectives. To support the implementation of equality budgeting, an Interdepartmental Network has been established, represented by senior members of staff from each government department with broad knowledge of the policy work undertaken by their department and its relevance to advancing the goals of equality and inclusion. The Network is responsible for:

ensuring that policymakers in their departments are fully aware of and implementing equality budgeting policy

bringing all relevant work within their department to the attention of the Equality Budgeting Unit to ensure the informed strategic direction of equality budgeting

ensuring the suitable representation of their department at meetings.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting; Government of Ireland (2019[8]), “Equality Budgeting”, https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/aec432-equality-budgeting/#expert-advisory-group (accessed 21 December 2022).

Methods and tools

This section outlines the methods and tools used by OECD countries to perform analyses and gather evidence on the gender impact of budget measure, highlighting the various approaches to the development of a comprehensive gender budgeting practice.

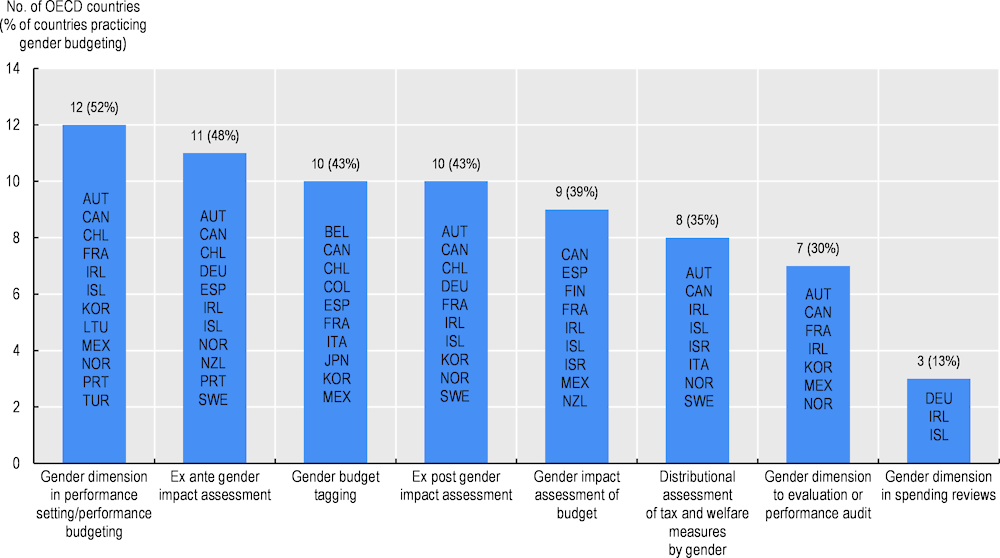

Selection of gender budgeting methods and tools

The appropriate selection of methods and tools for implementation across the budget cycle is essential to an effective and sustainable gender budgeting practice. In 2022, there is no common gender budgeting approach or suite of measures implemented across OECD countries. Rather, countries aim to select methods and tools that build on the foundation of their enabling environment and that fit within existing budgeting frameworks and ongoing reforms, while taking advantage of cross-government strengths. For example, a country with a strong focus on performance budgeting may integrate a gender perspective through their performance framework, while a country with a strong culture of gender impact assessment may choose to require assessments alongside all new budget proposals.

The implementation of gender budgeting methods and tools in 2022 is illustrated in Figure 2.7, showing that the application of a gender perspective in performance setting is used by the majority of OECD countries practicing gender budgeting (52%). On average, in 2022 three different methods or tools are used to implement gender budgeting by each OECD country. In 2022, Canada and Ireland use the greatest number of tools (seven). Other countries with a comprehensive range of gender budgeting methods include Iceland (six), and Austria, France, Mexico and Norway (five). In contrast, Belgium, Colombia, Japan, Lithuania and Türkiye use one tool each (Figure 2.7).

Of the countries that have been practicing gender budgeting since 2016 or 2018, those which have strengthened their approach through increasing the number of gender budgeting tools in use by 2022 include Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Ireland and Portugal.

Figure 2.7. Methods and tools used for gender budgeting, 2022

Note: Four countries also specified that they use “Other” tools not listed (Colombia, Finland, Germany and Mexico).

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 10.

The number of OECD countries using select gender budgeting methods and tools in each of the years 2016, 2018 and 2022 is presented in Table 2.1. A new tool which countries are experimenting with is the inclusion of a gender dimension in spending reviews. Spending reviews help governments prioritise and reallocate spending and are growing in use. Integrating a gender perspective can help ensure that budget reprioritisation does not increase gender gaps, but instead supports the achievement of gender goals (Nicol, 2022[9]).

Table 2.1. Use of gender budgeting methods and tools, 2016-22

|

2016 |

2018 |

2022 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

No. of OECD countries practicing gender budgeting |

12 |

17 |

23 |

|

Gender dimension in performance setting |

8 |

10 |

12 |

|

Gender impact assessment (ex ante or ex post) |

10 |

14 |

13 |

|

Distributional assessment of tax and welfare measures by gender |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Gender dimension in spending reviews |

2 |

4 |

3 |

Note: The information presented in the table relates only to data for tools that were available across the 2016, 2018 and 2022 OECD surveys on Gender Budgeting. Data relating to tools only available in 2016 or 2018 or 2022 have not been captured in the table.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 10; 2018 OECD Survey on Budget Practices and Procedures; 2016 OECD Survey of Gender Budgeting.

Gender budgeting evidence use across the budget cycle

Gender budgeting methods and tools are used to gather evidence that informs decision making across the different stages of the budget cycle: 1) planning and formulation, 2) approval, 3) implementation and reprioritisation. The implementation of methods and tools across OECD countries in 2022 is presented in Table 2.2. Analysis of this data suggests the tendency for countries to apply gender budgeting measures to direct budget prioritisation and foster greater transparency and accountability in the earlier stages of the budgetary process, rather than to obtain insights following implementation to improve scrutiny and budget reprioritisation or incorporate learnings into future budget decision making.

Examples of gender budgeting methods and tools implemented in 2022 to inform budget decision making across different stages of the budget cycle can be seen in:

Norway where the CBA collects ex ante information on the gender impact of budget proposals put forward by each ministry.

Korea where selected budget policies and activities are assessed following implementation against gender equality goals and performance indicators to assess programme performance and strengthen the impact of national policies.

An advanced approach to gender budgeting will incorporate a gender perspective across each stage of the budget cycle to improve the effectiveness of budget policy in meeting gender equality goals (OECD, 2023[6]). In 2022, 30% of OECD countries practicing gender budgeting have applied measures to inform decision making at each key stage of the budget cycle (Austria, Canada, France, Iceland, Ireland, Norway and Sweden) (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Use of gender budgeting tools and methods across the budget cycle, 2022

|

Planning and approval |

Approval |

Implementation and reprioritisation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender dimension in performance setting/performance budgeting |

Ex ante gender impact assessment of budget measures |

Gender budget tagging |

Gender impact assessment of budget |

Distributional assessment of tax and welfare measures by gender/gender-related budget incidence analysis |

Ex post gender impact assessment of budget measures |

Gender dimension in spending reviews |

|

|

Australia |

|||||||

|

Austria |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|||

|

Belgium |

■ |

||||||

|

Canada |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Chile |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|||

|

Colombia |

■ |

||||||

|

Finland |

|||||||

|

France |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|||

|

Germany |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||||

|

Ireland |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Iceland |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Israel |

■ |

■ |

|||||

|

Italy |

■ |

■ |

|||||

|

Japan |

■ |

||||||

|

Korea |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||||

|

Lithuania |

■ |

||||||

|

Mexico |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||||

|

Norway |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|||

|

New Zealand |

■ |

■ |

|||||

|

Portugal |

■ |

■ |

|||||

|

Spain |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||||

|

Sweden |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||||

|

Türkiye |

■ |

||||||

|

Total |

12 |

11 |

9 |

9 |

8 |

10 |

3 |

Note: While Italy undertakes gender budget tagging, this is done ex post and so is not included in the total for the planning and approval phase of the budget. Australia did not yet systematically use any tools and methods as it had just recently reintroduced gender budgeting.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 10.

Scope of gender impact assessment

Both ex ante and ex post gender impact assessment (GIA) remain two of the most common methods of gender budgeting evidence gathering used in OECD countries. Most countries apply these impact assessments to selected policies included in the budget, rather than all policies (Table 2.3 ). Box 2.6 provides an example of the criteria used by Austria in selecting which policies should be subject to a gender impact assessment.

Table 2.3. Scope of gender impact assessment, 2022

|

Ex ante gender impact assessment |

Ex post gender impact assessment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Selected policies included in the budget |

All major policies included in the budget |

Selected policies included in the budget |

All major policies included in the budget |

|

|

Australia |

||||

|

Austria |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Belgium |

||||

|

Canada |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Chile |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Colombia |

||||

|

Germany |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Finland |

||||

|

France |

■ |

|||

|

Ireland |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Iceland |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Israel |

||||

|

Italy |

||||

|

Japan |

||||

|

Korea |

■ |

|||

|

Lithuania |

||||

|

Mexico |

||||

|

Norway |

■ |

■ |

||

|

New Zealand |

■ |

|||

|

Portugal |

■ |

|||

|

Spain |

■ |

|||

|

Sweden |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Türkiye |

||||

|

Total 2022 |

6 |

5 |

7 |

3 |

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 10.

Box 2.6. Criteria for gender impact assessment in Austria

Gender impact assessments in Austria are embedded within the system of regulatory impact assessments (RIAs). Like other OECD countries, Austria has realised that not every new regulation or proposal needs the same level of scrutiny and has accordingly introduced RIA threshold tests.

RIA in Austria has to be conducted for all laws and regulations initiated by the executive and for government projects with major financial impacts. A threshold test (Wesentlichkeitsprüfung) introduced in 2015 determines whether a simplified or full RIA has to be conducted for draft regulations. The current threshold is EUR 20 million. While there are no exceptions granted, there is the possibility to conduct a simplified RIA (WFA light). Specifically, laws and regulations with no impact on the state budget, no significant impacts in other WFA areas, no financial impacts greater than EUR 20 million and no long-term financial impacts are eligible for WFA light.

These threshold tests help to ensure that regulations with significant societal impacts are adequately assessed before being introduced. Secondly, they ensure that government resources are not unduly wasted in assessing regulatory proposals with only minor impacts, where the costs of conducting RIA would outweigh its benefits. Therefore, it is important the resources used to develop a policy scale with the size of the problem and its solution.

Source: OECD (2020[10]) Austria: Regulatory Impact Assessment and Regulatory Oversight, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/RIA-in-Austria-web.pdf.

Future development of gender budgeting practices and approaches

Several OECD countries outlined their plans to further develop their gender budgeting practises. For example, Chile reported that they were focused on improving budget tagging processes across gender and other areas including climate change and the elderly and Colombia was working to integrate a gender approach across indicators for investment projects and the planning and budgeting process. Spain was preparing a Methodological Guide to enable better interpretation of the questions answered by ministerial departments categorising each budgetary expenditure programme, while also improving the graphic presentation of key results from their Gender Impact Report for increased accessibility (Ministerio De Hacienda y Funcion Publica, 2022[11]).

The future intentions of OECD countries to broaden the number of methods and tools that encompass their gender budgeting approach factored significantly in the 2022 survey:

Finland noted plans to undertake a gender impact assessment of the government's economic policy over the parliamentary term, building on an exercise done in 2018

Iceland is exploring the implementation of budget tagging and widening the scope of gender budgeting for greater inclusion of intersectional analysis

Ireland advised of the development of a tagging system to link budget allocation line items to dimensions of equality, green, well-being and Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) budgeting

Israel aims to develop guidelines for ministerial analysis of the budget from a gender perspective

Italy foresees the 2024 Budget Law providing the Parliament with a Sustainable Development Budget that includes classification of budgetary expenditure that promotes gender equality

Japan plans to incorporate gender equality perspectives into policy formulation and implementation processes using insights from gender budgeting and also plans to use the Gender Equality Council to enhance the effectiveness of gender budgeting through monitoring and impact studies

Türkiye intends to establish a reporting system that will monitor and evaluate gender equality indicators linked to budget measures and help better inform decision-making processes.

Enabling environment

This section highlights the increased uptake and the broadening of supports for gender budgeting measures across the OECD. The discussion to follow also illustrates how elements of a supportive enabling environment help with the effective implementation of gender budgeting methods and tools and can ensure the practice of gender budgeting is sustainable and continually improved over time.

Support for gender budgeting measures

Since 2016, there has been an increase in the number of OECD countries introducing guidelines, data collection and training initiatives to support the implementation of their gender budgeting practice. In 2022, the majority of countries that practice gender budgeting have the following elements in place:

CBA standard guidelines or annual budget circular detailing how to apply gender budgeting (70%)

Sector-specific (70%) or generally available disaggregated data (61%)

Training and capacity-building in the application of gender budgeting (70%).

Approximately half of OECD countries (47%) use five or more enabling environment elements to reinforce the implementation of their practice in 2022, similar to the situation in 2018 (47%) and 2016 (50%). Countries with the most elements in place are Korea (seven) and Canada (six), whereas those with the fewest elements in place are Germany and Japan (both one) (Table 2.4 shows some of the common elements).

Table 2.4. Common elements of an enabling environment to support gender budgeting, 2022

|

Support for Gender Budgeting |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Guidelines on how to apply gender budgeting |

Sector specific gender or sex disaggregated data |

Training and capacity building |

General availability of gender or sex disaggregated data |

Expert consultative group advises on gender budgeting |

|

|

Australia |

■ |

■ |

|||

|

Austria |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Belgium |

■ |

■ |

|||

|

Canada |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Chile |

■ |

||||

|

Colombia |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Germany |

■ |

||||

|

Spain |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Finland |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||

|

France |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Ireland |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Iceland |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Israel |

■ |

■ |

|||

|

Italy |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Japan |

■ |

||||

|

Korea |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Lithuania |

■ |

||||

|

Mexico |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Norway |

■ |

■ |

|||

|

New Zealand |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Portugal |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Sweden |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

|

Türkiye |

■ |

■ |

■ |

||

|

Total |

16 |

16 |

16 |

14 |

5 |

Note: This table shows the common elements of an enabling environment in place for gender budgeting, but not all possible elements, which include an inter-agency group to ensure co-ordination and exchange of good practices and programme budgeting.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 18.

Guidelines on the application of gender budgeting

Reflecting the technical nature of gender budgeting tools and processes, guidelines on the application of gender budgeting are central to creating a strong enabling environment. Examples of how guidelines are used to direct the application of gender budgeting are provided in Box 2.7.

Box 2.7. Guidelines on the application of gender budgeting in Korea and Norway

Korea

Legislation enacted in 2006 made it mandatory for the government of Korea to submit a Gender Budget Statement (GBS) and Gender Budget Execution Report analysing the impact of public spending on women and men from the 2010 fiscal year. In 2022, the GBS included 38 sectoral statements for each Ministry.

The annual budget circular issued to ministries to guide the development of the following year's budget proposals provides detailed instructions on how every aspect of the sectoral GBS and balance sheet is to be drafted by each ministry, through completion of a GBS form. The GBS form asks for line ministries to provide information on:

projects and policies directly aimed at enhancing gender equality (PDAs) or indirectly influencing gender equality (PIIs) and their allocated budgets

gender impact analysis findings

expected gender equality outcomes and targets

performance indicators and their rationale

reporting against overarching gender equality goals outlined in Korea’s Gender Equality Framework, such as the elimination of gender-based violence and the promotion of women’s health.

Norway

In 2020, Section 24 of the Equality and Anti-Discrimination Act (the Act) of Norway was clarified and strengthened to require that all public authorities actively work to systematically promote intersectional gender equality in all their activities, including budgeting. A reference to the duty to actively promote equality and report on it is included in Norway’s annual budget circular issued to ministries, which is used to prepare the state budget. The budget circular for 2023 includes two reporting requirements for ministries regarding budget proposals:

1. Public authorities must report on their action to integrate consideration of equality and non-discrimination in their work, including assessment of achieved results and a statement of the expected future outcomes of actions.

2. Public employers must report on the current state of gender equality in their organisation and their intended actions to fulfil their obligations according to Section 26a of the Act, including carrying out a salary survey from a gender perspective and documenting the survey biannually.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting.

Disaggregated data

Targeted policy development that draws on the insights attained through gender budgeting practices is contingent on good availability of quality disaggregated data. Disaggregated data across all or most key areas of the public service has increased from being available in 16% of OECD countries practicing gender budgeting in 2016 to 61% of countries in 2022.

Poor availability of disaggregated data was reported as a challenge to the implementation of gender budgeting by 17% of countries, including Ireland, Lithuania and New Zealand which have all more recently introduced gender budgeting, as well as Austria (Figure 2.8). Ireland recently completed a review of its data requirements in relation to equality budgeting and hopes to address these in coming years (Box 2.8).

Box 2.8. Audit of disaggregated data to support equality budgeting in Ireland

In 2020, the Central Statistics Office (CSO) of Ireland conducted a data audit of 107 data sources from 31 public bodies in co-operation with the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform. The audit aimed to ascertain the availability of public service data disaggregated by equality. In 2021, a focused equality data audit was conducted, covering all national data sources held by Tusla (the Child and Family Agency). This work was guided by the Equality Budgeting Expert Advisory Group representing key internal and external stakeholders and the audit findings were published alongside Ireland’s 2021 Budget. The information is also published on the CSO webpage and will continue to be updated as new data is identified.

In response to the data audit, the CSO and the Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth are developing a data strategy to identify what actions are needed to improve the disaggregation of data and identify actions needed to address data gaps.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting; Ireland Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (2022[12]), Budget 2022 - Equality Budgeting: Equality Audit of Tusla Data, https://assets.gov.ie/201255/04e174ba-a01c-4182-9a82-e2fa7df06442.pdf (accessed 13 March 2022).

Austria recognises insufficient political will and a lack of resources as the main limitations impacting the availability of data. Finland’s response to the survey also acknowledged that despite the country’s longstanding tradition of gender equality impact assessment of legislative proposals, assessment of the impact of budgetary measures on gender equality is affected by the insufficient availability of disaggregated data. Belgium, Israel, Japan and Lithuania reported that their gender budgeting practices were not yet supported by either sector specific or generally available disaggregated data in 2022 (Table 2.4).

Continual action is required to fill data gaps and improve data collections. For example, Sweden’s survey response indicated aims to require that all government agency annual reporting data and all official statistics pertaining to individuals be disaggregated by gender. Best practice gender budgeting is increasingly considering insights into the intersecting impacts of inequality, through analysis of data that accounts for the multiple aspects of an individual’s identity that can compound experiences of inequality (OECD, 2023[6]).

Training and capacity-building

The elements of a supportive enabling environment also include awareness raising initiatives and development of the necessary skills to perform gender budgeting practices through capacity development for relevant government stakeholders.

For example, in 2022, Türkiye carried out training programmes to increase the awareness of gender budgeting among members of parliament and government executives, as well as provide technical assistance to the public officials. Additionally, the CGI of France (Direction générale de la cohésion sociale - service des droits des femmes et de l’égalité femmes-hommes) and the CBA (direction du budget) undertake annual workshops with each ministry to improve identification of the impact of expenditure on gender equality as part of the drafting of the Appendix to the Annual Finance Bill. Canada also provides an example of how the implementation of gender budgeting can be supported through regular awareness raising activities and mandatory training and capacity building initiatives on the application of gender impact assessment (Box 2.9).

Box 2.9. Gender budgeting awareness raising, training and capacity development in Canada

Since 2012, the Government of Canada has held Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus) Awareness Week to promote understanding of the development of inclusive and responsive policies, programmes, services, and decision making that affects the well-being of all Canadians. In 2022, the events were hosted by Women and Gender Equality Canada (WAGE) in partnership with the Canada School of Public Service and included contributions from experts and champions sharing their vision for the application of the rigorous GBA Plus analytical process.

To further support the application of GBA Plus, since 2017 some departments in the Government of Canada have implemented mandatory training and development requirements for responsible government officials. Since 2018, GBA Plus guidance and templates are provided in preparation for the annual budget, as well as training and capacity building through in-person, online and digital platforms. Efforts have also been made to improve the quality of GBA Plus provided by departments for Cabinet proposals and Treasury Board Submissions through guidance documents.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting; Government of Canada (2022[13]), Gender-based Analysis Plus Awareness Week 2022: GBA Plus in Action - Opening Event, 11 April 2022, https://www.csps-efpc.gc.ca/events/gba-plus-awareness-week-2022/opening-event-eng.aspx (accessed 21 December 2022); Government of Canada (2022[14]), GBA Plus Awareness Week: May 9 to 13, 2022, https://women-gender-equality.canada.ca/en/gender-based-analysis-plus/gba-plus-awareness-week.html (accessed 21 December 2022); Government of Canada (2022[15]), Invitation to present in a live virtual event to celebrate Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus) Awareness Week, 19 April 2022, https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/maple-leaf/defence/2022/04/invitation-present-virtual-event-gba-plus.html (accessed 21 December 2022); Regan, E., and Wilson, M. (2019), ‘Demystifying Gender Budgeting: Case Studies from the OECD’, Paper presented to the Working Party of Senior Budget Officials – 3rd Experts Meeting on Gender Budgeting, OECD Conference Centre, Paris 19-20 September 2019.

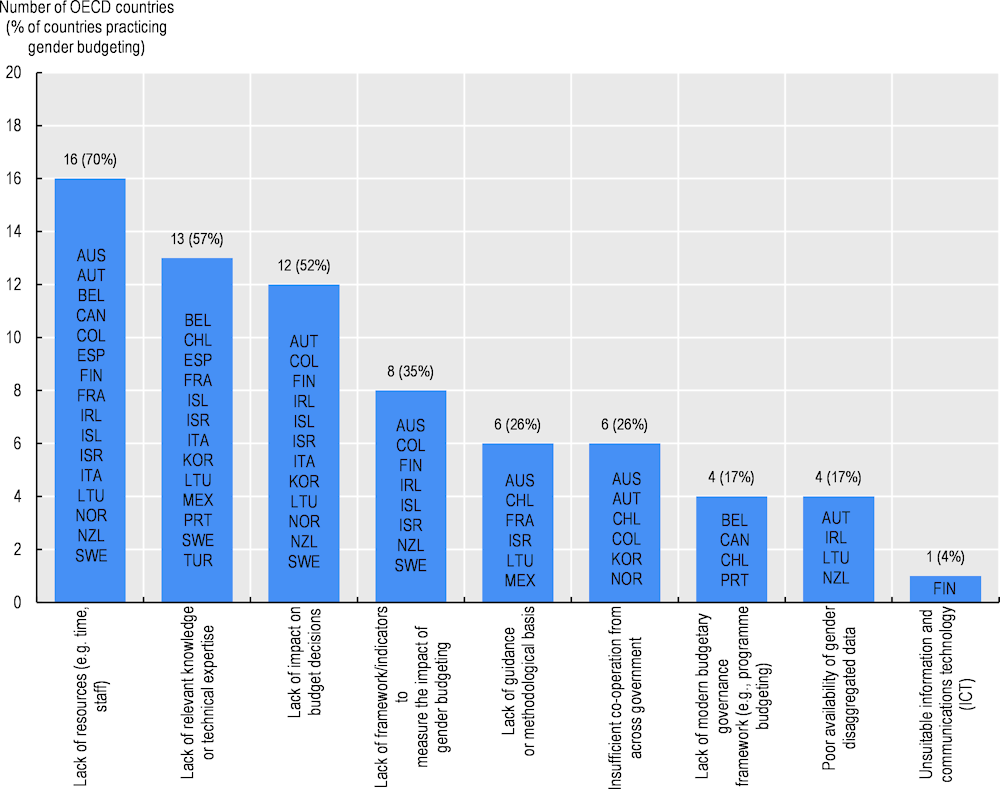

Although the roll out of training and capacity development initiatives has increased significantly since 2016 across OECD countries practising gender budgeting, a lack of relevant knowledge or technical expertise continues to be a challenge impacting its implementation in the majority of countries (57%) (Figure 2.8).

Main challenges impacting gender budgeting practices

Limitations to the implementation and effective practice of gender budgeting will affect its capacity to generate lasting impacts for society and the economy. Several challenges were identified by OECD countries practicing gender budgeting in 2022, with the most significant being a lack of resources to effectively implement gender budgeting measures; acknowledged by 70% of countries (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8. Key challenges in implementing gender budgeting, 2022

As New Zealand introduced gender budgeting on a pilot basis at the time of the 2022 survey, useful insights can be gained in assessing the challenges and successes experienced at this stage in the implementation process (Box 2.10).

Box 2.10. Challenges and successes in piloting gender budgeting in New Zealand

New Zealand identified several challenges encountered during the gender budgeting pilot, including:

A lack of legislative requirement for gender budgeting.

Some challenges with gaining insight into how gender budgeting may impact on budget decision making.

Time, capacity and resourcing constraints across government agencies to undertake an in-depth assessment of their Budget initiatives, and make any necessary amendments to proposed initiatives, during the Budget process. There is an assumption that agencies should complete a thorough policy development process in advance of preparing Budget initiatives, including considering gender impacts and using the Bringing Gender In tool where relevant, as there is limited time to do so during the Budget stage.

Accessing, utilising and collecting sufficient gender disaggregated data to inform gender impact assessments and analysis during the Budget process.

To address some of these challenges, the Ministry for Women is currently taking action to strengthen gender impact analysis through capacity building initiatives and updating of training materials across all Government agencies ahead of Budget 2023, including a refresh of the ‘Bringing Gender In’ online tool, and the Gender Budgeting guide. It is envisioned that these tools will further strengthen gender analysis across the New Zealand Government. The inclusion of gender budgeting in future budget processes remains the prerogative of Ministers.

Despite these challenges, the Ministry for Women and the Treasury (CBA) New Zealand received positive feedback from government agencies involved in the pilot. A review of the pilot in May 2022 found that:

All of the participating Budget initiatives would have an impact on women and girls, and nearly half of the initiatives would have a disproportionately positive impact for women and girls.

Nearly all of the participating initiatives (94%) identified an impact on Maori women and girls, of which over half would have a disproportionately positive impact.

The findings from the review of the gender budgeting pilot in Budget 2022 will be used as a baseline to track the impact on women and girls identified in budget initiatives and how well government agencies can identify and explain this impact. Statistical research is also being undertaken to understand the current wellbeing deficits in different population cohorts in preparation for the 2022 Wellbeing Report which has been identified as an opportunity to inform future spending priorities and to understand the demographic impacts of Budget allocations.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting and direct communication.

Accountability and transparency

By systematically integrating a gender perspective into the design, development, implementation and evaluation of relevant public policies and budgets, gender mainstreaming and gender budgeting reinforce government accountability and transparency notably through increasing visibility on how the budget is being used to ensure gender equality goals are prioritised and achieved. The 2022 survey asked a range of new questions, aimed at gaining insights into the establishment of internal and external scrutiny and oversight mechanisms for gender budgeting across OECD countries (see Table A.4). This section highlights the measures countries have put in place to foster transparency and accountability in relation to the impact of the budget on gender equality.

Inclusion of gender budgeting evidence in annual budget documentation

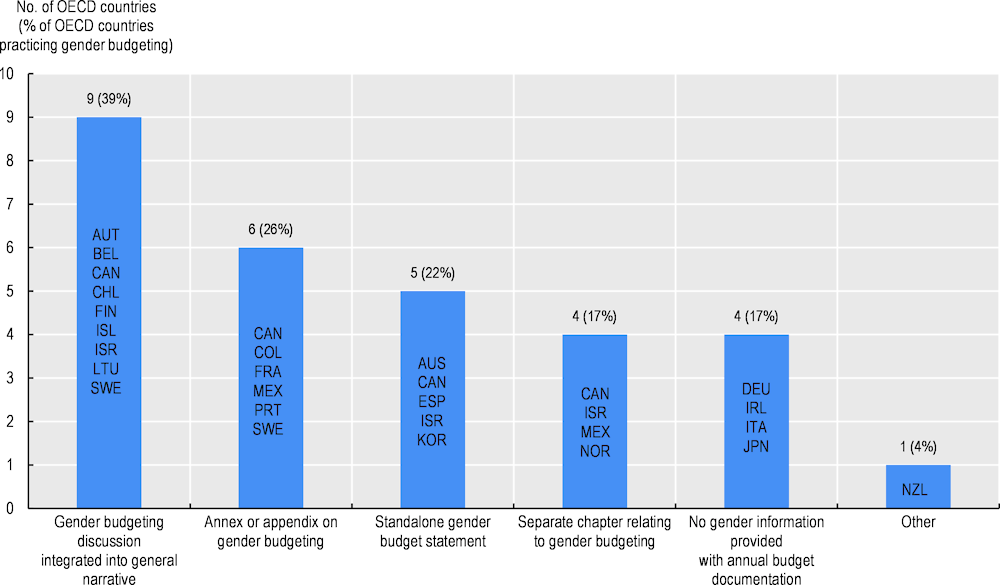

Across the OECD, various forms of gender budgeting evidence are included or accompany annual budget documentation to increase transparency and accountability on government action and public spending to achieve gender equality objectives. In 2022, the majority of OECD countries practicing gender budgeting included associated evidence in annual budget documentation (78%) (Figure 2.9). This represents an increase in countries including gender budgeting information in budget documentation, with 52% of countries reporting publishing a gender budget statement of varying content in 2018, and only two countries recording this practice in 2016 (Sweden and Korea) (Downes and Nicol, 2020[16]).

In 2022, gender budgeting discussion integrated into the general narrative of the budget was the most common medium used to present gender budgeting information in draft budget documentation, practiced by 39% of countries (Figure 2.9). For example, in Sweden gender equality analysis and gender-disaggregated data is provided throughout the Budget Bill, consisting of many volumes whereby in each policy area a discussion outlines the situation for women and men, girls and boys in relationship to the budget proposal and the possible impacts on gender equality if the policy was to be implemented.

Figure 2.9. Format of gender budgeting information provided with draft budget documentation, 2022

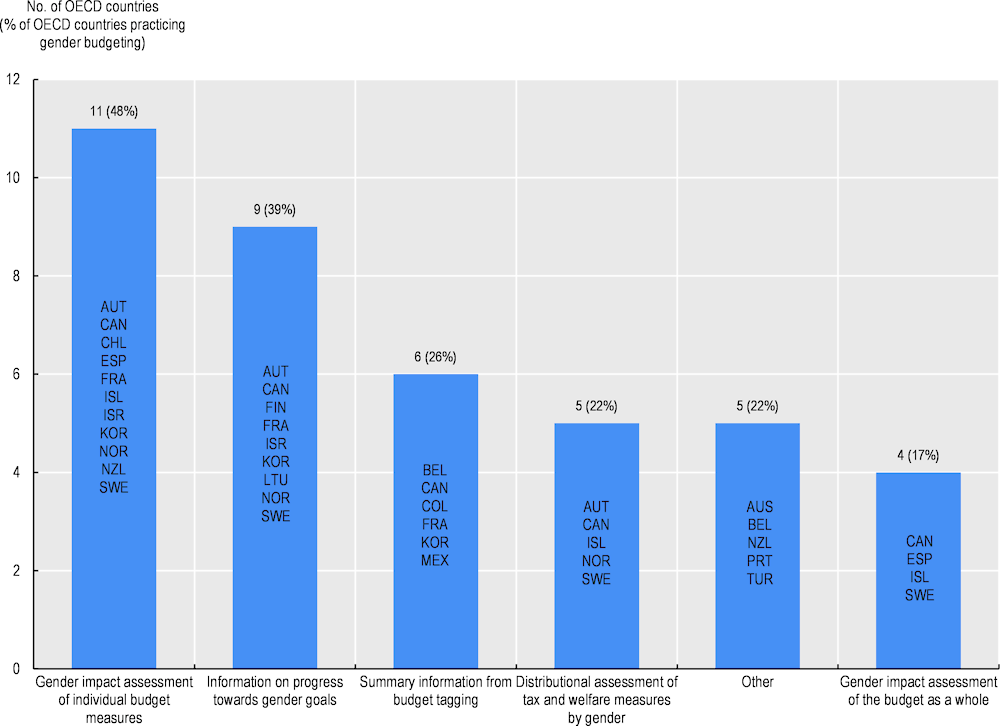

In 2022, the contents of gender budgeting information included or accompanying budget documentation most commonly took the form of gender impact assessments of individual budget measures in 48% of practicing countries, information on progress towards gender goals in 39% of countries and summary information from budget tagging in 26% of countries (Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10. Content of gender budgeting information provided with draft budget documentation, 2022

Examples of the various forms and contents of gender budgeting information included within or alongside budget documentation across the OECD in 2022 include:

Belgium – a gender comment explains how the gender perspective will be considered during the elaboration and execution of projects

Chile – an annual budget brochure is published presenting a gender orientated discussion within a summary of the planned expenditure for the following year

France – an Appendix to the Annual Finance Bill contains a gender impact assessment of individual budget measures and information on progress towards gender equality goals in the form of Key Performance Indicator annual strategy descriptions, analysis, forecasts, targets and results

Iceland – information on the gender impact of new budget measures is included as a part of the Budget chapters on revenue and expenditures.

Portugal – a set of gender equality indicators covering key policy areas are published – from digital to transport, social protection and infrastructures, wages and domestic violence – to promote an annual analysis of the gender impact of budget policies

Sweden – a gender impact assessment of the budget as a whole is published in an Annex to the Budget Bill, reporting on economic gender equality indicators across labour income, capital income, income tax, pensions and underemployment and unemployment

Türkiye – a budget justification from a gender perspective is included in budget documentation.

A further example of other types of information accompanying budget documentation is provided by New Zealand (Box 2.11).

Box 2.11. Information accompanying budget documentation in New Zealand

In New Zealand, following Budget Day, the materials provided to Ministers concerning the Budget are made publicly available on the Treasury website through a process where the Government proactively releases the information used to inform its Budget decision making. This would also include the results of the gender impact assessments and information relating to individual budget initiatives included in the gender budgeting pilot.

The information is distinct from the Budget documentation published on Budget Day to communicate the impact of Budget decisions to Parliament, media, analysts and the general public.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting.

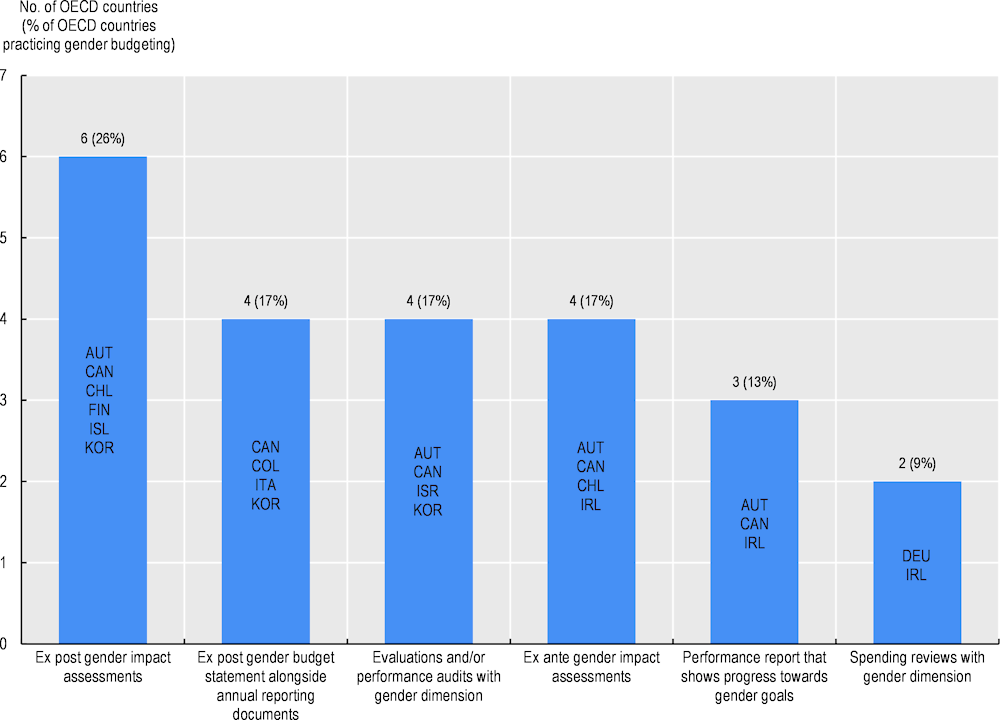

Gender budgeting information published by government

The 2022 survey gathered data on further methods used by OECD countries to encourage accountability and transparency of gender budgeting. The most commonly published information is ex post gender impact assessments, made public by approximately a quarter of countries practicing gender budgeting (26%) (Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11. Gender budgeting information published by the government, 2022

Examples of the various forms of gender budgeting information published by governments across the OECD in 2022 include:

Austria – an annual report that tracks gender equality outcomes across defined indicators, as well as an annual report aggregating the results of ex post regulatory impact assessments of laws and public investments conducted that year (including an evaluation of the gender dimension)

Belgium – the biannual evaluation of the application of budget tagging and justifications of budget allocations from a gender perspective undertaken by the Institute for the Equality of Women and Men is published on its website and outlined in the intermediary report and the end of term report to Parliament, the latter of which is legally required under the Law on Gender Mainstreaming.

Canada – Gender Based Analysis Plus undertaken in relation to evaluations are publicly available on departmental websites and annual Departmental Results Reports report on the gender and diversity impacts of programmes in supplementary information tables.

Colombia – a gender perspective of budgets and public policies is included in published information related to the budget tracker for Women’s Equity. These cover details relating to international commitments and the national regulatory framework, gender budgeting tools, summary analysis of investment and operating expenses for women's equality, projects and initiatives to close gender gaps and outcomes achieved, as well as challenges related to the budget tracker.

Iceland – Ministerial Annual reporting of the progress towards gender goals is published

Italy – information on the Gender Budget is published in the Government’s Annual Report to Parliament

Japan - the budget for each item listed in the Fifth Basic Plan for Gender Equality is published by the Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office

Korea – the number of beneficiaries of selected budget measures by gender, is published, where applicable

Mexico – government actions to promote gender equality and eradicate gender violence and forms of gender discrimination is published, as well as the analysis methodology concerning expenditures for equality

Portugal – external accountability for gender budgeting encompasses the publishing of progress reports against gender goals.

Spain – the Ministry of Finance and Civil Service has dedicated web pages where the Cross-Cutting Budget Reports can be accessed. The Gender Impact Report also has its own web page where users can access to the report itself and also consult the main results of the exercise. The main results are presented in a graphical format, allowing users to analyse them based on programmes, sections, and amounts.

External accountability for gender budgeting

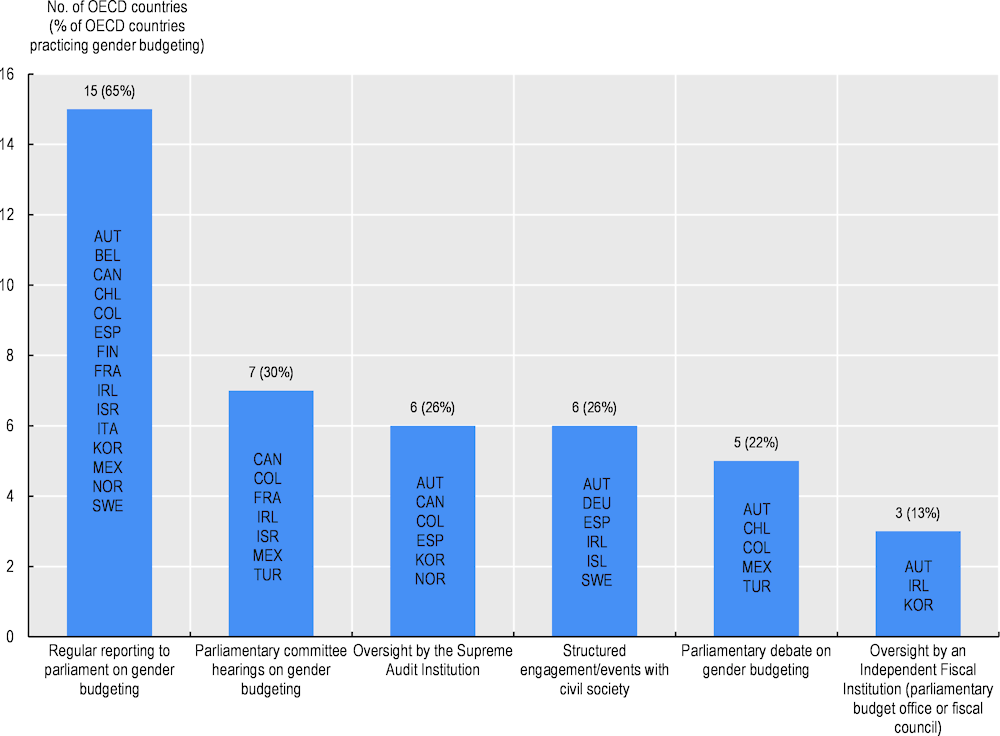

The implementation of external accountability processes for gender budgeting takes many forms across OECD countries. Accountability processes focused on parliamentary engagement in the gender budgeting process provide for an inclusive and participative method for scrutiny of budgetary decision making. It also helps ensure the government is held to account for how budget policy progresses gender equality objectives. In 2022, external accountability for gender budgeting was focused on the establishment of parliamentary processes, with regular reporting to parliament on gender budgeting being the most prevalent oversight method, practiced by 65% of countries (Figure 2.12). This is a significant increase from the number of countries practicing gender budgeting in 2016 reporting to parliament on the impact of gender responsive policies (50%). Other accountability methods focused on the work of specialised parliamentary committees dealing with budgeting that conduct hearings or take part in parliamentary debates on gender budgeting were practiced to a much lesser extent across OECD countries in 2022 (Figure 2.12).

Oversight by Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) or Independent Fiscal Institutions (IFIs), such as parliamentary budget offices, can also play an important role in gender budgeting systems through undertaking impartial assessments of government performance reports and outcomes measures, reviewing and validating gender impact assessments of budget measures and examining progress towards gender equality goals. In 2022, SAIs in a quarter of OECD countries practising gender budgeting (26%) undertook analysis relating to it, while IFIs exercised oversight in 13% of countries (Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12. External accountability for gender budgeting, 2022

Details of some of the mechanisms employed by OECD countries in 2022 to ensure external accountability for gender budgeting included:

Australia – Government expenditure proposals, as well as those contained in the annual Women’s Budget Statement, are scrutinised by the legislative and general-purpose committees of the Senate

Canada – since 2021, the Task Force on Women in the Economy has advised the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance on policy actions to address the unique and disproportionate impacts on women caused by the COVID-19 recession (Government of Canada, 2021[17])

Italy – external accountability is ensured through the publication of the Annual Report on the website of the Ministry of Economy and Finance and a selection of items made available on the App Bilancio Aperto (Open Budget)

New Zealand – regular periodic reporting on the implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, which recommended the introduction of gender budgeting in 2022, requiring progress reporting against this recommendation when the next periodic report is due back in 2023 (New Zealand Ministry for Women, 2023[18]).

Engagement with civil society on gender budgeting

Government engagement with civil society in respect of gender budgeting helps increase transparency and accountability. Civil society can also help inform gender equality needs assessments and the development of gender equality strategies that ensure inclusivity, good governance and strengthen the democratic process.

In 2022 a quarter of OECD countries practising gender budgeting undertook structured dialogue with civil society (Austria, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Spain, and Sweden) (Figure 2.12).

Expert consultative group

Governments may establish an expert consultative group with skills in economics, policy and gender equality to support gender budgeting through providing insights into community needs and policy impacts. Engagement with an expert group can also increase transparency and accountability of government action and ensure that the application of gender budgeting methods and tools are inclusive and thorough.

In comparison to other enabling environment elements, only a minority of OECD countries practising gender budgeting engage with an expert consultative group (Table 2.4). In 2022, just 22% of countries were obtaining guidance and advice from an expert consultative group on gender budgeting. Since 2018, Ireland, Israel, Korea and Portugal have established expert consultative groups, while Japan’s group has been active since 2016. Like other OECD countries, the establishment of Ireland’s expert consultative group reflects the timing of the introduction of their equality budgeting practice (Box 2.12).

Box 2.12. Expert consultative group on equality budgeting in Ireland

In Ireland, the equality budgeting Expert Advisory Group representing key civil society stakeholders and chaired by the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform was established in 2018 to provide ongoing strategic guidance on the development and implementation of equality budgeting policy. The role and objectives of the Group includes:

offering constructive, critical feedback on the Equality Budgeting initiative

providing expert guidance and informed insights on the future direction and areas of focus for equality budgeting, drawing on international experience and lessons from other policy areas and academia

promoting a coherent, cross-government approach to equality budgeting to maximise equality impacts and avoid duplication of effort across various policy areas

identifying existing strengths of the Irish policymaking system which can be leveraged in support of equality budgeting, along with potential shortcomings that need to be addressed in this regard.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting: Government of Ireland (2019[8]), “Equality Budgeting”, https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/aec432-equality-budgeting/#expert-advisory-group (accessed 21 December 2022).

External scrutiny processes for gender budgeting

The 2022 survey collected data on external assessments of the gender impact of the budget, either commissioned by the government or undertaken at their own initiative (Figure 2.13).

Non-government stakeholders such as think tanks or women’s organisations can provide observations and evidence that can have positive impacts on the quality of gender-responsive policymaking. For example, women’s advocacy groups often have direct experience and insights into the potential impacts of budget decisions on individuals and vulnerable cohorts. In 2022, half of OECD countries practising gender budgeting reported external assessments of the gender impact of their budgets being undertaken by non-government stakeholders (50%) (Figure 2.13). The categories of external stakeholders undertaking these assessments include:

Figure 2.13. Non-government stakeholders assessing the gender impact of the budget, 2022

Note: No data is available for Germany. The percentage is hence calculated on the basis of 22 survey responses for Question 16.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 16.

Impact

For the practice of gender budgeting to be effective and enduring, it is important that it demonstrates impact. The 2022 survey asked a range of new questions to understand the measures put in place by OECD countries to ensure the practice of gender budgeting generates impact, as well as the methodologies implemented to determine the impact of country’s approach to gender budgeting (see Table A.5 for further discussion).

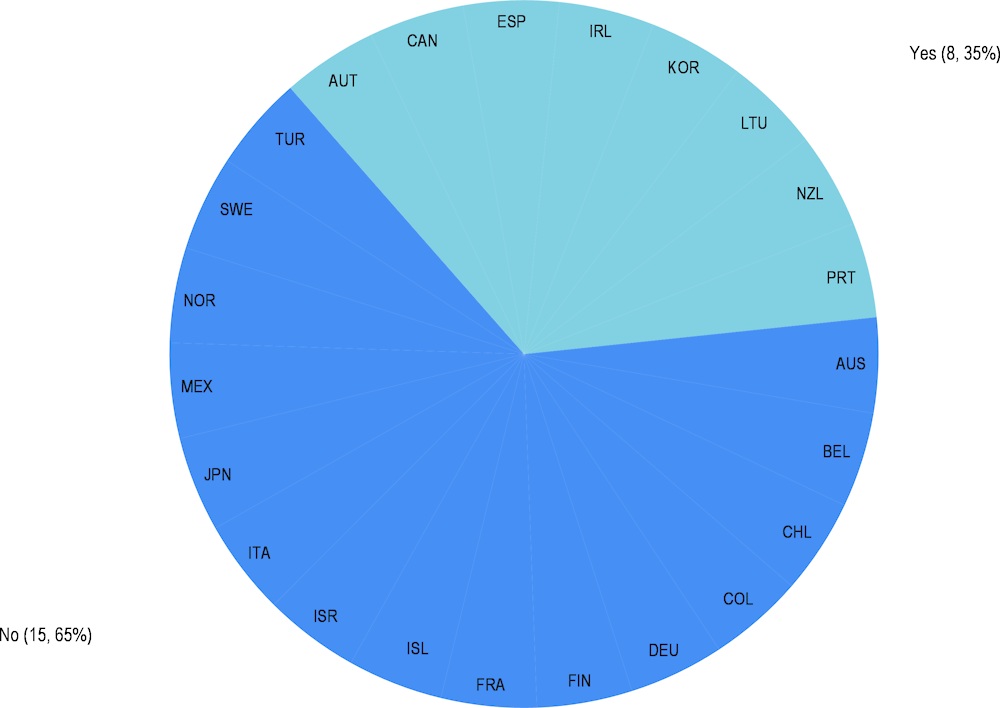

Methodologies for the measurement of gender budgeting impact

In 2022, eight OECD countries practicing gender budgeting reported having a methodology in place to measure the impact of their practice (35%) (Figure 2.14).

Example methodologies include indicators or frameworks set out in the budget or associated documents (Austria and Canada) and Budget Law (Portugal). Lithuania uses an external Gender Equality Index to track impacts, however, it was acknowledged that progress measures are currently being prepared and will provide information in the future. To assess the gender analysis provided in the gender budgeting pilot, New Zealand established a framework to review the expected gender equality outcomes on women and girls, and the level and quality of gender analysis capability of agencies involved in the pilot. The aim is to use the findings from the pilot to track progress in these two areas across government. The framework used to assess the analysis is subject to change as the shape and form of gender budgeting and the tools and resources to do this are reviewed and developed further.

Notwithstanding these examples, a number of OECD countries identified a lack of methods to measure the impact of their gender budgeting practice as a specific challenge to its effective implementation (Figure 2.8). This limitation was identified by 35% of countries practicing gender budgeting, including Colombia which recognised the need to collect further information and establish processes to effectively track progress in closing gender equality gaps.

Figure 2.14. Methodologies to measure the impact of gender budgeting, 2022

Use of gender budgeting evidence in policy and budget decision making

Gender budgeting provides a method for key gender equality objectives to be systematically considered in budget decisions to ensure resource allocation is directed where it will be most effective in achieving gender equality goals. The use of evidence gathered through gender budgeting methods and tools will improve the outcome of budget interventions and increase the real-world impact of gender budgeting practices. In this sense, although it is important to assess the macro impacts of gender budgeting as they may relate to gender equality objectives, the 2022 survey also recognised the importance of capturing the micro impacts of gender budgeting practices, asking new questions concerning how the implementation of gender budgeting is affecting policy redesign and/or budget decision making, through for example, the reprioritisation of public funding (see Table A.5 for further discussion). The OECD will continue to explore avenues to collect data on the detailed impacts of gender budgeting practices.

In 2016, half of the countries practicing gender budgeting determined measures were having a sector specific impact on policy development and resource allocation decisions (Belgium, Israel, Japan, Korea, Norway and Spain). Mexico was the only country in 2016 to report gender budgeting having a significant impact, while Sweden identified insufficient information to make an informed assessment as to the impacts of its gender budgeting practice. In 2022, an increase can be seen in the number of OECD countries practicing gender budgeting that observe an impact on policy development and resource allocation either across the government as a whole (Canada and Spain) or specific areas (Austria, Belgium, Chile, Colombia, Ireland, Iceland, Korea, Mexico, Norway, Sweden) (Figure 2.15).

Notwithstanding these reported tangible gender budgeting outcomes, 52% of countries practicing gender budgeting identified a lack of impact on budget decisions as the main challenge impacting the effective implementation of gender budgeting measures (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.15. Effectiveness of gender budgeting, 2022

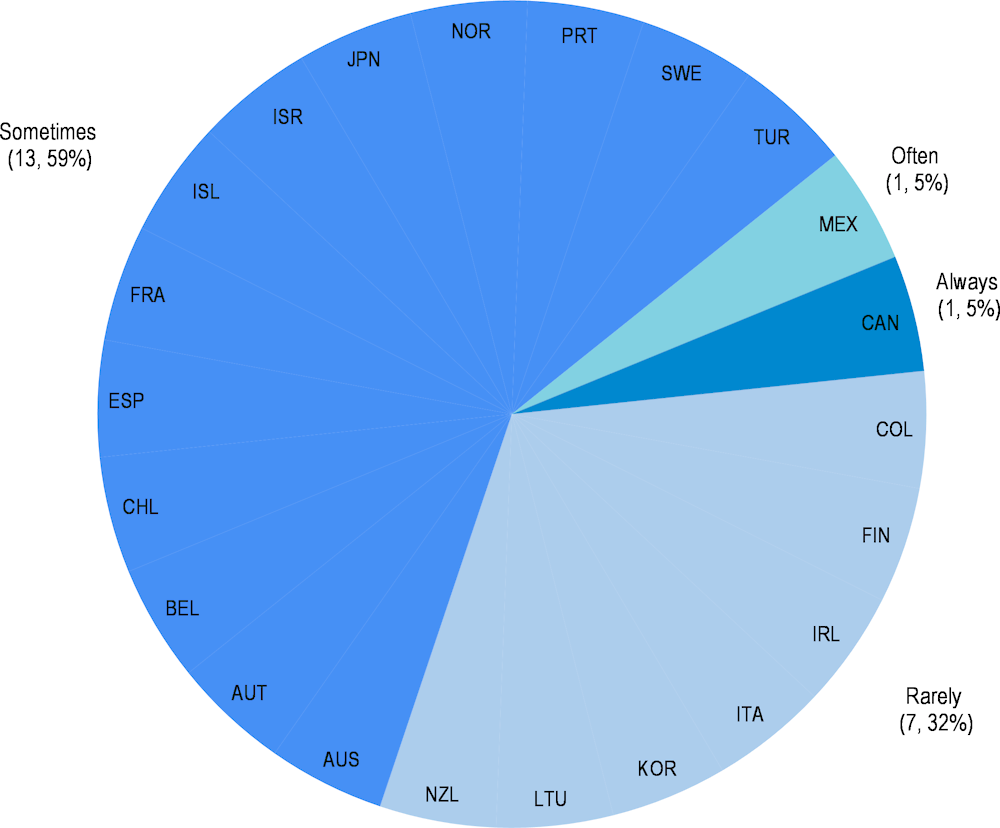

Another method to measure the impact of gender budgeting is through assessment of the frequency with which gender budgeting evidence is used in budget decision making. Gender budgeting information is required to accompany budget proposals in the majority of OECD countries (52%) practicing gender budgeting in 2022 (Austria, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Ireland, Iceland, Mexico, New Zealand5, Portugal, Sweden, Türkiye).

Data on the information provided alongside draft budget allocations was collected for the first time in the 2022 survey, however data on a similar gender budgeting measure, ‘gender perspective in resource allocation’, was captured in previous surveys. Analysis of this data shows that 8 countries implemented this measure in 2016 and 9 countries implemented the measure in 2018, representing an increase in the number of countries presenting gender budgeting information alongside draft budget proposals across surveys.

Despite countries practicing gender budgeting requiring information accompany budget proposals in 2022, only two countries reported that gender budgeting information was always or often used (Canada and Mexico), 59% of countries (13 countries) reported that gender budgeting insights were used sometimes, and 32% of countries (seven countries) advised that evidence gathered through gender budgeting was rarely used (Figure 2.16). These survey results demonstrate a significant opportunity for improved use of gender-sensitive data and insights in budget decisions.

An example of the information accompanying budget proposals is provided by Belgium, where a justification containing an explanation of how the gender perspective will be considered during the execution of budget projects must accompany the budget allocations published in the Budget Law adopted by the Parliament. A different method is applied in France where the annual Budget Bill is accompanied by annual performance reports which include gender-based indicators and analytical commentaries.

Figure 2.16. Use of gender budgeting evidence in budget decision making, 2022

Note: No data available for Germany. The percentage is hence calculated on the basis of 22 survey responses for Question 21.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting, Question 21.

Impacts of gender budgeting on policy formulation and resource allocation

OECD country responses to the 2022 survey provided several examples of the specific impacts of gender budgeting on policy formulation and resource allocation. This includes the establishment of tax reform through a gender lens in Austria and the strengthening of planning processes to address gender gaps in the mining, energy, transport, sports and health sectors in Colombia. Japan reported adjustments to resource allocation redirected to support women’s health and economic inclusion and similarly Korea reported increased resources in the 2022 Budget for the lease of automated agricultural machineries in the small-scale farming sector, which is overrepresented by women and heavily dependent on traditional farming methods due to lack of access to machinery. Box 2.13 presents further in-depth examples of the impacts of gender budgeting on policy formulation and resource allocation reported by OECD countries in 2022.

Box 2.13. Impacts of gender budgeting on resource allocation and policy formulation

Canada

Gender Based Analysis Plus and the Gender Results Framework (GRF) have been used to inform budget decisions to ensure they directly address gender equality goals. The 2022 Budget’s Statement and Impacts Report on Gender, Diversity, and Quality of Life outlines some of the GRF pillars that have been advanced through targeted budgetary investments, across education and skills development, leadership and democratic participation, gender-based violence and access to justice. These include apprenticeship incentive grants to encourage the pursuit of careers in traditionally male dominated industries, awareness programmes to promote trades as a career choice, support for women and girls in leadership and decision-making roles resulting in better opportunities and positions in various spheres, and funding allocated as part of the government’s COVID-19 response to ensure front line services and shelters continued to provide essential supports for women and families fleeing violence.

Iceland

A gender analysis of the government’s initiative to create jobs and boost the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that most jobs would be created in male dominated sectors, resulting in adjustments to resource allocation to focus on investments in the innovation and creative sectors with a more equal gender ratio. Additionally, a gender analysis of the recipients of farming subsidies showed that even in farms run by heterosexual couples, males were the majority recipients due to farming subsidy legislation restricting the recipient of subsidies to only one person. This was found to have a direct impact on women's income and pension savings and as a result the legislation was amended to allow each person in a couple to be registered as recipients.

Sweden

In Sweden, gender budgeting is applied throughout the budget process, steered at the operation level via the budget circular instructions. There is a government decision stipulating that gender mainstreaming of the state budget process, i.e. gender budgeting, is mandatory. In addition to gender mainstreaming the budget process, there are specific government appropriations for gender equality measures to fund targeted policy measures to advance gender equality. In line with the principle of gender mainstreaming, specific gender equality challenges that are identified in various policy fields, such as the higher rate of long-term sick leave for women, the gender care gap, or women’s lower participation in paid work are addressed with special measures in respective policy areas. However, it was acknowledged that there is an opportunity for gender budgeting principles to be further operationalised and more frequently and widely influence policy design to address inequalities and reallocate resources to increase impact.

Source: 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting.

Review of gender budgeting practices

The implementation of measures to review gender budgeting practices is important to ensure continuous improvement of a country’s overall approach. This can be achieved through conducting gender budgeting systems audits that examine opportunities to enhance or optimise evidence gathering methods and tools. In 2018, four countries reported that audits of gender budgeting systems and processes were being undertaken by various actors. In Austria, audits were performed by the Court of Auditors, in Iceland an NGO was auditing processes, while in Mexico the CBA was performing systems audits and in Sweden both the CBA and ministries were undertaking this function.

In 2022, Canada outlined the performance of gender budgeting systems audits through the systematic review and refinement of existing gender budgeting tools at the conclusion of each budget cycle, taking in account the lessons learned during the budget process and feedback and consultations from branches within Finance Canada and other federal departments. Additionally, the Office of the Auditor General in Canada has undertaken several audits on the implementation of GBA Plus, with the most recent follow up audit to the Fall 2015 Report, performed in 2022, highlighting that responsible institutions had taken action to identify and address barriers to the implementation, yet more could be done to assist departments and agencies to fully integrate GBA Plus, as well as close capacity and disaggregated data gaps, and improve weaknesses in monitoring and reporting. An example can also be seen in Portugal’s plans to undertake a comprehensive review of their gender budgeting measures. The review will cover ex ante, ongoing and ex post gender impact assessment of public policies, legislation and budgeting, as well as obstacles to the use of the Gender Budgeting Annex, the establishment of gender equality budget performance indicators, the development of online data collection tools and a diagnostic report of the level of data disaggregation that currently exists across policy areas.

External evaluations can also be used to conduct a wholescale review of a country’s approach to gender budgeting. In 2022, 30% of countries practising gender budgeting indicated that they had undertaken evaluations of gender budgeting in the past (Austria, Finland, Korea, Norway, New Zealand6, Portugal, Sweden), and 13% of countries foreshadowed plans to undertake evaluations in the future (Finland, New Zealand, Türkiye). An example can be seen in Austria’s evaluation of budgeting in 2017, which included a review of gender budgeting practices (Box 2.14).

Box 2.14. OECD review of budgeting and gender budgeting in Austria

At the request of the Austrian Government, the OECD conducted a review of budgeting in Austria in 2017, including a review of gender budgeting practices. The Review found that the overall systemic approach to gender budgeting, designed to require all ministries to consider gender equality in high-level goal-setting and in more detailed specification of outputs and objectives, is a leading international practice.

When considering the effectiveness and impact of gender budgeting, the Review found that gender budgeting in Austria is a special case of outcome-oriented policymaking and performance budgeting and is thus subject to a similar range of strengths and potential weaknesses.

To begin with, the requirement to specify gender equality objectives has in some cases catalysed a serious discussion about how public policies affect the equality agenda. For example, in the area of tax policy, specifying an objective relating to the fairer treatment of paid and unpaid work (encompassing also, therefore, unpaid work done in the home, disproportionately by women) generated a productive debate that influenced the development of tax reform.

Equally however, some perceived shortcomings of the general system of performance oriented budgeting - especially in the area of inter-ministerial co-ordination and strategic alignment - also arise in the case of gender equality. Stakeholders involved in gender budgeting observe that the design of gender-related outcome objectives is left up to the line ministries, without any strong sense of an over-arching strategic agenda for how to measure progress towards, and achieve, gender equality in Austria.

The Review put forward a series of recommendations to help strengthen gender budgeting going forward.

Source: Downes, von Trapp and Jansen (2018[19]), “Budgeting in Austria”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol. 18/1, https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-18-5j8l804wg0kf.