Establishing sound institutional arrangements for the delivery of gender equality policy, including clear roles and responsibilities and adequate capacity and resourcing, is key to tackling gender inequalities. The Czech Republic has taken some steps to strengthen its institutional architecture for gender equality in recent years, but further efforts could be envisaged to promote a co-ordinated approach across the government. This chapter first presents an overview of the whole-of-government institutional framework for gender equality and mainstreaming in the Czech Republic. It then analyses the roles, responsibilities, capacities and capabilities of the institutional actors tasked with promoting the country’s gender equality agenda at the national level and assesses challenges and scope for improvement. It concludes with a set of targeted policy recommendations to reinforce the existing institutional set-up, with the aim of supporting the Czech Republic in achieving its gender equality goals.

Gender Equality in the Czech Republic

4. Getting institutions right in the Czech Republic

Abstract

4.1. Introduction

Tackling gender inequality is a complex public policy issue. It necessitates a robust institutional set-up within the public administration with adequate capacities and capabilities. Tackling gender inequality is also a cross-cutting public policy challenge that affects many areas throughout a person’s life cycle. For example, domestic violence can also have critical impacts on women’s labour force participation outcomes and housing, among others. If ministries across the public administration work in an isolated manner, these critical linkages might be missed, potentially resulting in additional costs for the public administration due to overlaps in programmes and expenditures and provision of less-efficient public services. In the context of a tightening fiscal situation and its commitment to efficient public spending, the Czech government would benefit from a well-developed and co-ordinated institutional approach to its gender equality policy. The national Gender Equality Strategy 2021-30 (Strategy 2021+) also considers strengthening the institutional set-up as one of the country’s overarching goals. OECD analysis of the current strategic institutional set-up and processes in the Czech Republic, especially for cross-cutting policy issues, suggests that these have not been conducive to the sound co-ordination and implementation of strategies. In particular, the lack of strategic steering capacities and alignment from the centre have led to the multiplication of strategies and an absence of consistency and implementation across policies (OECD, 2023[1]). Such factors might also hamper the needed institutional set-up for gender equality in the country. A whole-of-government approach to gender equality implies that the institutional responsibilities for advancing gender equality goals are, ideally, distributed among the centre of government (e.g. the Cabinet Office and the Ministry of Finance); a central gender equality institution (i.e. a body tasked with promoting, co-ordinating and facilitating the gender equality policy in a country at the central or federal level); line ministries and agencies (across all policy areas); data-collecting and producing bodies; and independent oversight institutions as well as public administrations across various levels of government (OECD, 2019[2]).

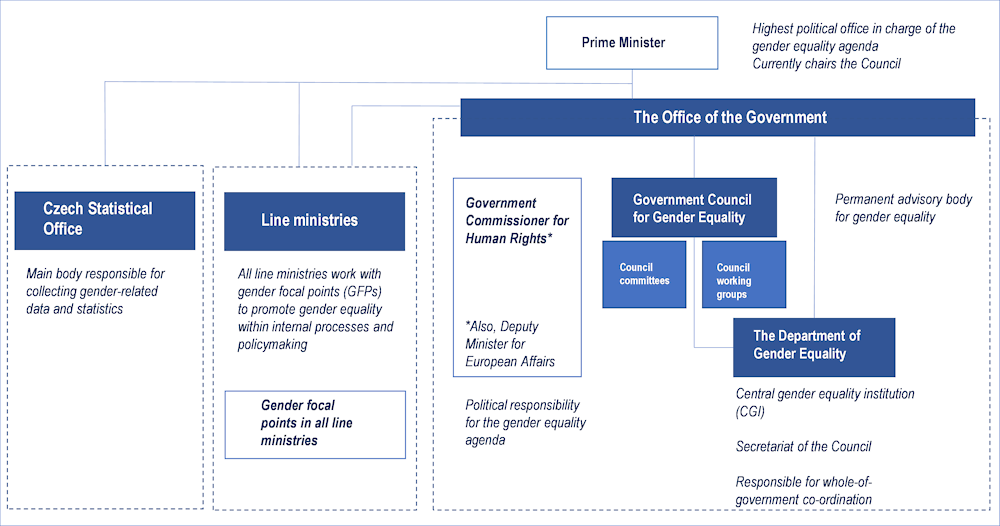

This chapter presents an overview of the institutional set-up for gender equality in the government of the Czech Republic including roles, responsibilities, capacities and capabilities of various public institutions engaged in advancing the country’s gender equality agenda. Figure 4.1 gives a snapshot of this institutional set-up.

Figure 4.1. Institutional set-up for gender equality in the Czech Republic, 2023

Source: OECD elaboration.

4.2. Political responsibility for the gender equality portfolio

4.2.1. There is scope to strengthen the institutional set-up for the promotion of gender equality in the Czech Republic

The highest political authority in charge of the gender equality agenda is the Prime Minister, who chairs the Government Council for Gender Equality (the Council) and submits to the government any legislative and non-legislative materials dealing with gender equality. In addition, the Government Commissioner for Human Rights (the Commissioner) within the Office of the Government fulfils a key political role to promote gender equality. The Commissioner supports the Prime Minister in promoting gender equality at the cabinet level and is responsible for developing long-term frameworks for gender equality at the national level, designing measures to achieve gender equality, assessing materials of a legislative and non-legislative nature concerning gender equality (via the interagency commenting procedure in the eKLEP), and implementing and reporting on international commitments in this area. The Commissioner serves as the Vice-Chair of the Council as well as other relevant government advisory bodies dealing with human rights, the Roma minority, national minorities, non-profit organisations, and people with disabilities and is responsible for the agenda related to these areas (Government of the Czech Republic, 2023[3]). In carrying out the mandate of this position, the Commissioner co-operates closely with the Gender Equality Department (the Department).

The Commissioner, while fulfilling a key function, is not a member of the government and the role does not have the mandate to make direct submissions to the Cabinet. Importantly, political responsibility for the gender equality agenda in the Czech Republic has shifted between different ministries over the past decade and since 2018, there has been no dedicated Cabinet Minister holding political responsibility for gender equality agenda.1 At the time of writing this report, a recent development was the appointment of the Commissioner as the Deputy Minister of the Minister for European Affairs. Such overlaps in institutional responsibilities could, however, risk dividing the attention dedicated to the promotion of gender equality.

Having the gender equality agenda within the Prime Minister’s portfolio can give it strong political momentum. But this also poses a risk that the gender equality agenda could be sidelined amid conflicting priorities on the Prime Minister’s often-overcrowded agenda. This is especially the case in times of crisis such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic or in cases where gender equality has not been explicitly identified as a government priority.

Going forward, the necessary institutional and political impetus for the advancement of the gender equality agenda could be created by systematically institutionalising the Commissioner’s role through strengthened links with the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) and the Cabinet and/or appointing a dedicated minister with access to the Cabinet and the mandate to propose or challenge cabinet submissions in relation to gender equality. Instead of ad hoc arrangements, systematic cabinet representation for the gender equality agenda – consistent with the set-up in a majority (56%) of OECD countries –may encourage its consideration at the epicentre of political decision making and signal its importance to both public and private actors (OECD, 2022[4]). Similarly, a stronger role for the PMO – for instance by appointing a counterpart of the Commissioner in the PMO or ensuring regular meetings with the Prime Minister within the Council or at its preparatory meetings – can help follow and steer the gender agenda. Box 4.1 presents examples from several OECD countries that have established dedicated cabinet ministerial responsibility for the gender equality agenda and, as is the case in the Czech Republic, a central gender institution to lead the policy work in the CoG.

Box 4.1. Dedicated ministerial portfolios with gender equality institutions in the centre of government in OECD countries

As of 2022, the Australian Government has a standalone portfolio for gender equality, led by the Minister for Women. The current minister also leads the portfolios on finance and public service. The Minister is supported by the Office for Women, Australia’s central gender institution, located in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Since 2022, Austria has a Federal Minister for Women, Family, Integration and Media (who previously led the combined portfolios for women, family, youth and integration) in the Federal Chancellery. At the policy and administrative level, the Division for Women and Equality, a part of the Federal Chancellery since 2018, undertakes this work.

As of 2022, political responsibility for the gender equality agenda in the United Kingdom lies with the Minister for Women and Equalities. The work on policy relating to women is led by the Government Equalities Office in the Cabinet Office of the United Kingdom.

4.3. Central Gender Equality Institution in the Czech Republic

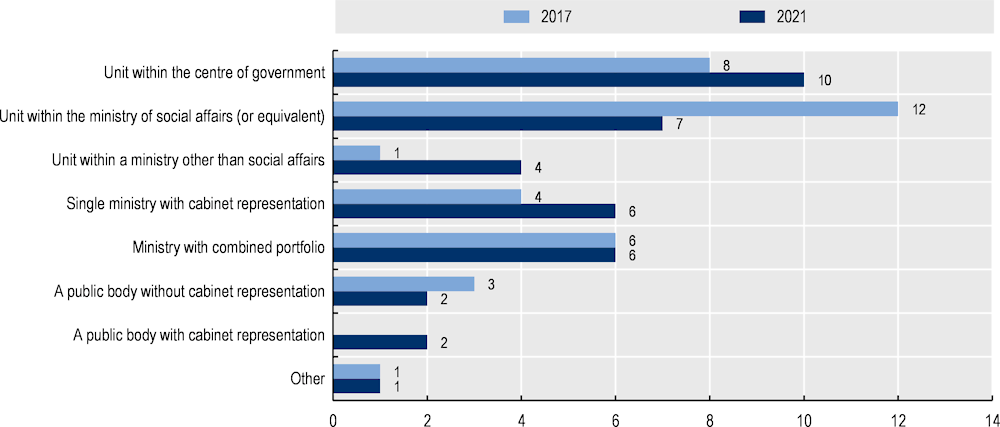

Across the OECD, there is no homogenised set-up for promoting the gender equality agenda due to variations in the wider administrative and institutional structures. However, every OECD member has established a central gender equality institution to advance overarching gender equality goals at the national or central level. Figure 4.2 shows the commonly used institutional arrangements for CGIs in OECD countries as of 2021 (OECD, 2022[4]). Typically, CGIs carry out functions such as delivering specific programmes for women’s empowerment, co-ordinating for the gender equality agenda, developing guidelines or toolkits to support line ministries in gender mainstreaming, implementing gender equality-related programmes and policies, and making policy recommendations (OECD, 2019[2]). COVID-19 and its emergency response were reminders that CGIs play a unique and vital role in ensuring that gender equality is not sidelined in government action. In Switzerland, for example, the Federal Office for Gender Equality collaborated with the national taskforce for COVID-19 to mainstream policies that promote gender-inclusive considerations; while Mexico’s National Institute for Women facilitated a gender-inclusive emergency response by ensuring co-ordination and collaboration among secretariats of the federal government and local governments.

Figure 4.2. Units within the centre of government are the most common arrangements for central gender equality institutions in OECD countries

Source: Information collected by the OECD based on desk research and data from (OECD, 2021[8]), OECD Survey on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance.

4.3.1. The Gender Equality Department is the central gender equality institution in the Czech Republic

The Gender Equality Department (the Department) fulfils the role of the central gender equality institution (CGI). While formally located within the Office of the Government, the Department falls under the authority of the Government Commissioner for Human Rights. It is led by the Director of the Department, who reports to the Government Commissioner for Human Rights and the Head of the Office of the Government. Box 4.2 synthesises the Department’s mandate.

Box 4.2. Mandate of the Gender Equality Department in the Czech Republic

Under the organisational rules of the Office of the Government and an internal directive defining its mandate, the Department is responsible for a range of activities. While this list is not exhaustive, the responsibilities include, among others:

creating and evaluating national framework, strategies and priorities for promoting gender equality

fulfilling and monitoring of the international commitments and commitments ensuing from membership in the EU in the area of gender equality

filling the role of secretariat of the Government Council for Gender Equality

co-ordinating the gender equality agenda throughout the public administration and non-governmental sector

gender mainstreaming in legislative and non-legislative documents as part of the interagency commenting procedure

conducting gender analyses, awareness-raising activities and training in relation to gender equality

monitoring and evaluating the current state of gender equality in the Czech Republic

providing methodological support to line ministries.

As the CGI of the Czech Republic, the Department co-ordinates the development, implementation and monitoring of Strategy 2021+. Additionally, it develops various analytical materials, provides methodological support for the Gender Focal Points and other public officials across the public administration, conducts trainings and awareness-raising activities, and represents the Czech Republic on various international platforms, among other tasks. Department also serves as the Secretariat of the Government Council for Gender Equality.

4.3.2. While the Department has a central location, it could benefit from a stronger mandate and capacities

As discussed in Chapter 3, the Department is well placed within the Office of the Government to carry out a strategic co-ordination role for the cross-cutting gender equality policy. Through the CoG’s convening power, the Department has the authority to engage line ministries and other public entities in mainstreaming gender considerations in their work. The importance of having CGIs placed closer to the CoG is increasingly recognised across the OECD. As shown in Figure 4.2, while the most common configuration in the OECD for the CGIs was to place them within the ministries of social affairs (or equivalents) in 2017, this trend has recently been shifting with the growing number of countries making a shift towards units in the CoG in the past five years (OECD, 2022[4]).

There are several important gaps, however, that could create uncertainty and pose a potential risk to the Department’s fulfilment of its role. First is the absence of a legislative framework that clearly outlines the mandate and location of the Department as the central gender equality institution in the country. The Act No. 2/1969 Coll., on the Establishment of Ministries and other Central Bodies of the State Administration (the Competency Law) states that the Office of the Government is responsible for issues related to ensuring that activities of government bodies are fulfilled. However, the law does not explicitly entrust responsibility for the gender equality goals to any organ of the central administration. The absence of a legislative framework covering responsibility for the gender equality objectives has an impact on their implementation and leads to it being significantly dependent on the willingness of the government in power to deal with this issue.

A related challenge is the limited clarity of the Department’s mandate. Strategy 2021+ names the Department as the main entity responsible for gender budgeting, in co‑operation with the Ministry of Finance. To effectively fulfil this role, it would be important to strengthen the Department’s expertise in matters of budgeting as well as the broader resource base (Chapter 6). Additionally, although it does not have a formal oversight role and therefore lacks corresponding capacities, the Department also has the opportunity to comment on the adequacy of gender impact assessments (GIAs) conducted for legislative and non-legislative proposals before they are submitted to the government via the interagency commenting procedure, eKLEP. Similarly, while its role in this regard has not been defined, the Department closely collaborates with the Czech Statistical Office regarding gender statistics (Chapter 5).

Another gap stems from the uncertainty around the Department’s location within the institutional set-up as well as its nature. In the past, the work on gender equality was undertaken by a unit and not always by a department. Furthermore, the team working on the gender equality policy was relocated several times between the Office of the Government and the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. Stakeholders consulted for this report identified that these changes posed additional barriers to the continuity of the gender equality policy. In line with the objectives of Strategy 2021+ and as part of the Competency Act, strengthening the legal basis for the responsibility for the promotion of gender equality within the government, and thus the mandate and location of the Department as part of the CoG can help the Department future-proof its mandate and underpin the continuity of the gender equality as a cross-cutting and complex public policy.

As noted throughout this report, there is significant scope to strengthen the sustainability of the funding model as currently, only two positions within the Department that are funded by the state budget, with the rest funded by external sources.

Finally, while the Department benefits from its location in the CoG, its size is rather small, which can limit its capacity to support the public administration through research and analysis on gender. OECD countries facing similar issues have tried to overcome this challenge by introducing agencies with complementary mandates or by ensuring adequate staffing (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. Additional analytical capacities can support small centre of government teams

Iceland has established not only a Department of Equality within the Prime Minister’s Office to co-ordinate the equality agenda but also a special institution under the administration of the Prime Minister called the Directorate of Equality to oversee matters related to equality legislation. Similarly, in Sweden, the smaller team of the Division for Gender Equality under the Ministry of Employment works with the Swedish Gender Equality Agency on the gender equality agenda. On the other hand, governments can also take efforts to ensure adequate staff capacities for a CGI that is located in the centre of government. For example, the Australian Office for Women within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet currently has approximately 75 staff members, also supported by seconded officials from other departments.

Source: (Government of Iceland, n.d.[11]); Information provided by the Government of Iceland in 2021; (Government of Sweden, n.d.[12]); (Government of Sweden, n.d.[13]); Information provided by the Australian Government in 2022.

4.4. The role of the centre of government

The centre of government can be defined as the highest-level support structure of the executive branch of government that generally supports the activities of the head of government. Across the OECD membership, CoG performs key co-ordination functions, primarily for cabinet meeting preparations, policy co-ordination and strategic management. In a broader sense, CoG extends beyond the bodies reporting directly to the head of the government to also include bodies or agencies such as ministries of finance or planning that also often perform cross-cutting government functions at the national or central level (OECD, 2017[14]). With regard to gender equality goals, the CoG can play a key role to ensure government-wide implementation by clarifying the roles of the line ministries, holding them accountable through mechanisms such as performance management frameworks, and ensuring adequate integration of a gender lens in their work (OECD, 2019[2]).

4.4.1. There is room to strengthen the decision-making capability of the Government Council, the main advisory body for gender equality in the Czech Republic

Established by a Government Resolution, the Government Council for Gender Equality, attached to the Office of the Government, is the permanent advisory body on gender equality. Box 4.4 explains its mandate and how it operates.

Box 4.4. Mandate and functioning of the Government Council for Gender Equality

The mandate of the Council entails:

monitoring national fulfilment of the Czech Republic’s international commitments on gender equality (including the commitments from the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women)

identifying current problems in the area of gender equality and co-ordinating the main directions of ministerial policies regarding gender equality

discussing and recommending the key conceptual directions of the government’s progress in promoting gender equality to the government, especially through the processing of proposals regarding policies in various areas of gender equality and proposals for measures and initiatives to improve gender equality

monitoring the implementation of strategic documents in relation to gender equality and evaluating the effectiveness of measures taken towards t achievement of gender equality.

The Council usually meets four times a year, and the chair is obligated by statute to be present at least twice. The Council can establish and dissolve committees dealing with specific issues regarding the Council’s area of competence. There are currently four committees dealing with the participation of men and women in decision-making positions, domestic and gender-based violence, gender equality in the job market, and the institutional framework for gender equality.

The Council also establishes working groups as needed to deal with particular issues based on the mandate, focus and agenda as determined by the Council. Currently, three task forces or working groups cover the following themes: obstetrics, the role of men in promoting gender equality, and evaluation of projects in the subsidy programme of the Office of the Government of the Czech Republic that are targeted to the non-governmental sector for the implementation of the (previous and current) national strategies on gender equality. A fourth working group on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality was established with the aim of studying the proposed response measures and their impact on gender equality as well as formulating recommendations to the Commissioner or other line ministries regarding measures under the scope of their policy particular area.

Source: Government of the Czech Republic (2022[10]), Mandate of the Government Council for Gender Equality. https://www.vlada.cz/assets/ppov/rovne-prilezitosti-zen-a-muzu/Statut-Rady-2022.pdf.

The Council has 42 members. Its chair is the member of the government responsible for the gender equality agenda – currently the prime minister – who also appoints (and dismisses) the members of the Council and two vice-chairs (chosen among the members) discussion by the Council. The members include representatives of the line ministries, ideally at the level of the Deputy Ministers, or, in certain cases a State Secretary of a given ministry nominated by the relevant ministers. Other members include representatives of central organs such as the Czech Statistical Office and the Office of the Public Defender of Rights), representatives of the non-governmental sector, and experts. The Department, as the secretariat, co-ordinates the activity of the Council and its committees and working groups. The secretary of the Council (who is the director of the Department) participates in Council meetings in an advisory role and may submit proposals and comment on matters discussed (Government of the Czech Republic, 2022[10]).

In practice, however, the line ministries are most frequently represented by their respective State Secretaries. On one hand, representation at this senior level is positive as it enhances the ability of the Council members to translate its decisions into action within their line ministry. On the other, given that State Secretaries in the Czech Republic often oversee the Departments of Human Resources and those related to the Public Servant Act, this can risk linking or even confusing the broader gender equality agenda with more narrowly defined issues of gender equality within human resources management. In matters related to gender mainstreaming in policymaking, the representation of Deputy Ministers or Directors-General within the Council could be more effective in terms of translating the recommendations of the Council to action in line ministries.

Its mandate also requires the Council to publish an annual report on the government website (Government of the Czech Republic, 2022[10]). As part of the reporting exercise, there is scope to strengthen the Council’s mandate and capacity to monitor and follow up on the implementation of recommendations that it provides to the government with a view to further consolidate the impact of the Council’s work (Chapter 7). For instance, the Council’s role could be expanded to have stronger links with decision-making bodies in the executive, namely the PMO and/or the Cabinet.

4.4.2. There is scope to engage other units within the Office of Government to fulfil key gender equality functions

Beyond the key role played by the Department, different units located within the Office of the Government have the potential to accelerate the achievement of national gender equality objectives. The Office of the Government has two main organisational sections: the economic and technical section in charge of preparing government sessions and the legislative section in charge of the expert and legislative content of government sessions (e.g. preparation of draft legislation, etc.) (OECD, 2023[1]). As noted in Chapters 5 and 7, the legislative section (including the Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) Unit and the RIA Board) can potentially play an important role to strengthen compliance with Gender Impact Assessment (GIA) methodology and GIA oversight. Additionally, the newly established Government Analytical Unit (VAU) could also provide the necessary methodological checkpoint for conducting GIAs. An important first step is to ensure the availability of gender expertise within these structures (Chapter 7).

4.5. Gender focal points across the Czech Republic’s public administration

4.5.1. Gender focal points have been established to support gender mainstreaming in line ministries

Engaging line ministries is essential to ensure effective gender mainstreaming across the government, as they can play a key role in integrating gender considerations within their routine functioning, decision-making processes and management structures. Recognising this need, the OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life stresses the importance of adequate capacities and resources of public institutions to integrate gender equality perspectives in their activities (OECD, 2016[15]). These can be developed through, for example, establishing dedicated institutional mechanisms; training; promoting collaborative approaches with knowledge centres to produce gender-sensitive knowledge, leadership and communication; ensuring the collection of gender-disaggregated statistics in institutions’ areas of responsibility, and providing clear guidelines, tools, communication and expectations across all public institutions.

The Czech Republic has undertaken efforts to establish institutional structures for advancing the gender equality agenda in all ministries. The position of gender focal point (GFPs) was established by government resolution in 2001, and its scope was expanded subsequently in 2017.2 All line ministries are required to institute this position on at least a part-time basis to promote gender equality within their internal processes and policymaking.

4.5.2. Efforts should be taken to ensure that GFPs are fit-for-purpose

In practice, there are inconsistencies in the scope and mandate of the GFPs across ministries and in their ability to integrate the gender perspective into the routine functioning of the line ministries. GFPs face a number of barriers to ensuring that GIAs are systematically and meaningfully conducted, while no role has been envisaged for GFPs in the process of gender budgeting (Chapters 5 and 6).

4.5.3. GFP Standard could be strengthened to support fulfilment of the mandate

Noting an insufficient fulfilment of the government resolution on GFPs, the Office of the Government (i.e. the Department) in co-operation with the Committee for Institutional Framework for Gender Equality and existing GFPs developed a Standard of the Position of Gender Focal Points (Standard) to consolidate the position; the government approved this in 2018. The Standard defines seven factors relevant to the position of GFP (and 22 indicators) and considered crucial to the effective promotion of gender equality: organisational placement, job description in an internal directive, competencies, qualification requirements, deepening of knowledge, and the extent of the working time and key rules for the establishment and functioning of the ministerial working groups and task forces for gender equality. The Standard imposes a duty on the department to monitor and evaluate implementation of the standard every year, propose an update if needed, and report the results of the monitoring in the Annual Report on Gender Equality (Government of the Czech Republic, 2023[16]). However, the standard serves only as a recommendation and is non-binding in nature, leading to inconsistencies in its take-up across line ministries.

The 2021 reporting on the implementation of the Standard indicated that only six of 14 ministries had established a GFP as a full-time position. In the remaining line ministries, it was a part-time (mostly half-time position) and in a few ministries, even less than half time. For instance, the gender focal point in the Ministry of Culture devoted between 0.1 and 0.4 of the full-time equivalent (FTE)3 to work related to gender equality; the Ministry of Justice 0.5 of the FTE (however the person has to deal with all issues related to human rights agenda too). In previous years, a few line ministries received EU funding (Operational Programme Employment) for projects focused on promoting gender equality that enabled increased capacities dedicated to this work. An example is the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, which devoted 2.5 FTE personnel for promotion of gender equality between 2017 and 2020. However, the added capacity was a temporary change as the positions were dismissed once the given projects ended.

In an effort to sustain gender capacities in line ministries, the Department provides methodological support to ministries to apply for funding for work related to gender equality, and thus GFP positions, through the new Operational Programme Employment+. However, this is a temporary solution that is not able to provide a more sustainable response to the challenge of low personnel capacities to support gender mainstreaming. Given the uneven application of the GFP Standard, strengthening its status and scope could be considered so it is consistently applied across line ministries.

4.5.4. An updated standard can better define centre of responsibility and centre of expertise for gender mainstreaming within line ministries

Annual reporting on implementation of the GFP standard, suggests that GFPs face several challenges in supporting the integration of a gender perspective into all policy documents. For instance, the position was located in the human resources (HR) department in 10 of the 14 line ministries. As discussed above in the case of the State Secretaries of the ministries, locating GFPs in HR departments could risk having the position interlinked, or even confused with the HR agenda and sometimes overly focused on gender-based discrimination in employee-related matters. In addition, some GFPs have to deal with various aspects of the human rights agenda. The low personnel capacities for the GFP position, coupled with its location in HR departments without adequate representation or mandate related to departments in charge of policymaking, make it difficult for GFPs to support the integration of the gender perspective into policy documents.

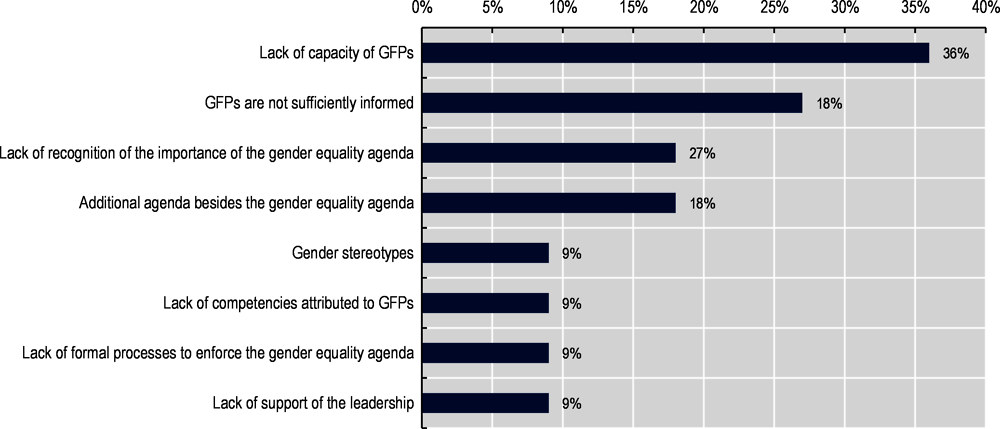

Adding to these challenges is the fact that GFPs are not formally involved in the policymaking cycle.4 For instance, as discussed in Chapter 5, the 2021 annual reporting on the implementation of the GFP Standard revealed that the GFP is formally included in the internal comment procedure for the review of legislative and non-legislative documents under development in only four line ministries. In other line ministries, GFPs sometimes have informal access to this procedure. However, even if a GFP has an opportunity to informally make comments or support gender mainstreaming in documents, they do not have the ability to ensure that their suggestions are taken into account. GFPs often struggle with a lack of information as usually they are only present at the management meetings of their respective unit should the meeting agenda have an item related to gender equality. This is the case for meetings of various advisory bodies or working groups as well. This lack of access and information hinders GFPs from systematically mainstreaming gender in policy documents and participating in gender impact assessments (Government of the Czech Republic, 2021[17]). Furthermore, several GFPs have reported facing resistance, persistent gender stereotypes or absence of leadership support as additional barriers in their work (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. Lack of capacities and information are the most commonly reported barriers by Gender Focal Points

Source: OECD (2022[18]), Questionnaire on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance in the Czech Republic.

Another challenge is the absence of minimum qualification requirements regarding gender expertise or awareness for the position of GFP, which raises concerns about the adequacy of the gender focal points’ knowledge and expertise to perform the role. Relatedly, only four line ministries require a public servant exam in the area of human rights; in these ministries, the exam is required within the first year of employment or public service.

In light of these challenges, the Standard itself could be updated to better define the roles, responsibilities and location of the GFPs in relation to other actors within line ministries in a way that ensures the systematic involvement of GFPs in the policymaking process, as well as to reinforce personnel capacities devoted to the co-ordination of the gender equality goals and gender mainstreaming. Introducing minimum qualification requirements for GFPs can go a long way towards facilitating the fulfilment of the gender mainstreaming agenda in line ministries. Developing trainings and other guidance materials for GFPs also is extremely vital to the execution of their function.

It is important to note that in line with the OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life, GFPs help provide gender mainstreaming expertise and support to the line ministries in which they are located. They should not be expected, however, to act as the main or sole responsible actors to deliver on the ministries’ gender equality objectives. The following sections discuss the resourcing and capacities across the government to support gender mainstreaming efforts. Identifying senior-level civil servants who can champion and steer the gender equality-related goals of the ministries could provide an impetus to this work.

4.6. The state of resources and capacities for gender mainstreaming across the Czech Republic government

4.6.1. Greater investments would be needed to strengthen the implementation of the gender agenda

Greater investments in gender equality agenda have the strong potential to bring social and economic gains, especially during times of slowing growth (Chapter 1). Given that the COVID-19 crisis deepened existing structural gender inequalities in the Czech Republic and the current economic, fiscal and humanitarian context threatens inclusive recovery (Chapters 1 and 2), the country could greatly benefit from ensuring that the existing capacities and resources deliver the best value for the promotion of gender equality objectives.

The United Nations Committee for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women has previously noted the low personnel capacities and lack of finances dedicated to the gender equality agenda at the level of the state administration as a key barrier to the effective pursuit of gender equality policy in the Czech Republic (UN, 2010[19]). As noted, there is limited funding for personnel within the Department, for GFPs in line ministries and for other bodies of public administration such as the Czech Statistical Office or the Office of the Public Defender of Rights. This limits, in turn, the overall personnel capacities devoted to promotion of gender equality throughout public administration.

Some public administration activities in relation to gender equality are funded through the budgets of the individual bodies or ministries – for example, the position of GFP. However, ministries do not allocate specific finances to promote gender equality within their budgets (OECD, 2022[18]). Chapter 6 discusses the opportunities offered by gender budgeting to support advancements in this area. As discussed in Chapter 3, there are important financing opportunities for public administration activities relating to gender equality under programmes from EU funds and EEA/Norwegian funds (e.g. Operational Programme Employment). An evaluation of the Czech Republic’s 2014-20 gender equality strategy by the Gender Equality Department noted that ministries that applied for such funding options showed higher level of the fulfilment of this strategy. However, reliance on EU or EEA/Norwegian funds for financing positions for regular perennial tasks, instead of financing short-term needs, creates a lack of sustainability and continuity.

To close gaps in the implementation of the Strategy 2021+ and speed up progress towards the Czech Republic’s ambitious gender equality goals, sustainable and alternative financing mechanisms can be considered. In times of fiscal consolidation when increasing budget allocation may not be a viable option, alternative solutions can be tested based on lessons from across the OECD. For example, the Czech government could consider options such as pooling and sharing resources across ministries or a refocusing of existing resources. Promoting staff mobility through secondment could also help overcome resource constraints, though the possibility for this option does not exist currently within the country’s public administration. Box 4.5 describes the United Kingdom’s approach to joint financing.

Box 4.5. Joint financing arrangements in the United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, joint financing arrangements have been extensively explored in the health sector and at the local level. For instance, the statutory basis for the operative framework of the National Health Service (NHS) allows NHS bodies (i.e. primary care trusts, mental health trusts and care trusts) and local authorities (i.e. London and metropolitan borough councils, county councils, and unitary authorities) to delegate functions to one another to meet partnership objectives and create joint funding arrangements with ease. An example is the formal agreement between the Swindon Borough Council and Swindon Primary Care Trust for the commissioning of services with a pooled fund for integrated services for children and young people and services for disabled children. The pooled fund covered the commissioning of all local authority services outside the dedicated schools grant as well as community health services, child adolescent mental health services, sexual health and contraceptive services, and maternity and community paediatric services. The agreement was coupled with another partnership agreement for integrated services in 2008 that allowed for the secondment of 200 staff from NHS Swindon to the Council.

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (formerly the Department of Communities and Local Government) in the United Kingdom also published a guide for local governments in England on pooled and aligned resources to further awareness of these options and their technical aspects. This guidance document highlights how aligned or pooled budgets can help overcome constraints in public finances and help deliver efficient and effective services.

Aligned budgets involve two or more partners working together to jointly consider their budgets and align their activities to deliver agreed aims and outcomes, while retaining complete accountability and responsibility for their own resources.

A pooled budget (or fund) is an arrangement whereby two or more partners make financial contributions to a single fund to achieve specified and mutually agreed aims. It is a single budget, managed by a single host with a formal partnership or joint funding agreement that sets out aims, accountabilities and responsibilities.

4.6.2. There are no systematised or routine trainings related to gender equality for civil servants

The Czech Republic has a decentralised training system for public officials as each ministry or agency is responsible for carrying out needs analysis and establishing an annual training plan. In its capacity of implementing the Civil Service Act, the Ministry of Interior co-ordinates trainings administratively, issues recommendations on training and provides the overall framework for service authorities to carry out training. However, at present, there is no strategic framework guiding the development of trainings. Nor is there a centralised body (e.g. a national school of government or dedicated training ministry) conducting these efforts. Managers in the Czech Republic’s public administration are required to identify learning needs of their subordinates. This suggests an overall ad hoc nature of trainings, which risk being ineffective and duplicating efforts in cases of transversal policy issues such as gender equality (OECD, 2023[1]).

Based on OECD findings, public servants receive very brief information about the gender equality objectives and goals during the initial entrance training. Later, more detailed training is not provided systematically and when it is provided, it is usually of a sporadic nature. For example, the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports and the Ministry of Environment reported that they provided training to public servants in policymaking departments and other key public servants. Some public servants, such as officials of the Ministry of Transport, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports underwent training focused on gender impact assessments. At the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Finance, trainings dealing with sexual harassment were held.

Going forward, the government could consider solutions to remedy these gaps, for example by developing systematic training modules for this purpose that can be used across the government. These could be made mandatory in a staggered manner, given resource constraints. There is scope to consider measures to ensure at least one public servant within every relevant unit would receive adequate training in gender mainstreaming tools and/or gender equality topics in the given policy areas. As noted, while these opportunities are currently unavailable to Czech public servants, introducing mobility opportunities within the public administration, for example through secondments or job shadowing to facilitate skills transfer, could also be an option. Box 4.6 presents examples from OECD countries in this regard.

Box 4.6. Examples of country practices to improve staff capacities

Australia’s secondment arrangements

The Australian Public Service Act has introduced the possibility of secondment transfers for public service employees, allowing them to transfer between an Australian Public Service (APS) entity to another APS entity or to a state or territory government entity, private company, or community organisation. The assignments usually range from 3 to 12 months, and short assignments of 6-12 weeks are also available. These mobility opportunities are in place to develop the employee’s skills but can also be offered to support a critical need at the host entity. Secondment provides the opportunity for employees to learn about gender-focused policymaking from a practical perspective and to become more sensitised about the issue once they are back at their home institution by joining institutions focused on gender equality such as the Workplace Gender Equality Agency.

The three types of secondment transfers, including their financial arrangements, that are possible for Australian Public Service employees are as follows:

Temporary transfers: The host entity employs the seconded employee temporarily and pays the employee’s salary and on-costs. The employee may retain an ongoing position at the home entity.

Secondments free of charge: The employee remains employed by the home entity during the transfer. The home entity continues to pay the salary of the employee and covers on-costs that will not be reimbursed by the host entity.

Reimbursed or recovery arrangement covered secondments: The employee remains an employee of the home entity, which continues to pay the employee’s salary and on-costs but the employee seeks reimbursement of said costs from the host entity.

Several tools and programmes have been put in place to facilitate employee transfers. One of these is a mobility jobs board where Commonwealth employees can search for temporary assignments, including secondment arrangements, open in all national institutions and in all states.

Finland’s Gender Glasses in Use project

The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland, responsible for gender mainstreaming in the country, provides training and guidance across the central government on operational gender equality and non-discrimination. In support of gender mainstreaming, the ministry has prepared a handbook to develop methods and orientation training related to gender mainstreaming. This is practical guidance on gender impact assessment, drafting legislations, and planning of ministries’’ operations and finances. It was drawn up in 2009 as part of the national gender mainstreaming project, Gender Glasses in Use. The handbook and project aimed to equip national administration staff with a basic “understanding of gender mainstreaming principles and how to evaluate the gender impact of policymaking”.

The Gender Glasses project consisted of three phases:

Phase one consisted of large-scale seminars to raise awareness of the issue. In addition, a background brochure on gender mainstreaming was prepared that provided tools, a checklist and key questions are useful when integrating the gender perspective into the work of ministries.

Phase two consisted of holding thematic seminars for members of the equality working groups in each ministry.

Phase three consisted of training and consulting services provided to three specific ministries (education, social affairs and health. And interior). The training sessions were designed based on the consultation with the ministries on their needs.

In a self-evaluation exercise, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health highlighted the positive feedback received from participants as well as some key factors that contributed to the success of this programme and lessons learned. Among these were the following:

The training sessions were short.

Training sessions were designed in a progressive manner, with basic concepts covered in the first phase (e.g. gender mainstreaming) followed by advanced training sessions tailored to each ministry’s needs.

Training in gender mainstreaming in national administrations must attract senior officials and those directly drafting budgets, laws and programmes to ensure that gender mainstreaming is integrated into the policy cycle.

Training programmes on gender mainstreaming must take into account the evolving needs of participants.

Gender training benefits from including practical examples, which should be linked as closely as possible to participants’’ work.

Currently, the handbook of the Gender Glasses project is available online to support the work of ministries on gender equality. Moreover, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, jointly with the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare and the government digital learning environment eOppiva, developed an online training session on gender mainstreaming. This is intended for personnel of the central government. Its purpose is to train government staff on the importance of gender equality and equity. It is free and open on the eOppiva website.

4.7. Policy recommendations: A roadmap for the Czech Republic

Further institutionalising the role of the Government Commissioner for Human Rights and/or a dedicated minister on gender equality with access to the Cabinet and with the mandate to propose or challenge cabinet submissions in relation to gender equality can provide the necessary political impetus for the advancement of this agenda. Strengthening the links between the Commissioner and the Prime Minister and Cabinet, through regular meetings, for instance, could also support the steering of this agenda.

While the Gender Equality Department strongly benefits from its location within the centre of government, further legal consolidation of its mandate and positioning can reinforce its effectiveness. In line with the objectives of Strategy 2021+ and as part of the Competency Law, strengthening the legal basis of the responsibility for the promotion of gender equality within the government – and thus the mandate and location of the Department as part of the centre of government – can help the Department future-proof its mandate and underpin the continuity of gender equality as a cross-cutting and complex public policy.

As the Department fulfils a key function, its analytical capacities could be further strengthened to co-ordinate the government-wide gender equality policy and to carry out research to support the whole of government. Further clarification of its mandate should be backed by correspondingly adequate resources. There are various ways to improve the department’s capacities including during times of fiscal consolidation. These could include, for example, pooling and sharing of resources, refocusing available resources, or staff mobility opportunities.

There is room to strengthen the decision-making capability of the Government Council for Gender Equality, the main advisory body for gender equality. To further consolidate the impact of the Council’s work, its mandate to monitor and follow up on the implementation of recommendations that it provides to the government could be strengthened. There is scope to better integrate the Council and its work into decision-making processes by strengthening the link and submitting decision points to the Prime Minister and Cabinet meetings. Enhancing the representation of Deputy Ministers or Directors-General within the Council could also be more effective when it comes to translating the recommendations of the Council into action in line ministries.

Beyond the Department, other units within the Office of Government do not have a formal role in gender equality and yet can potentially fulfil key functions going forward. The Legislative Section (e.g. the RIA Unit) can potentially play an important role to strengthen compliance with GIA methodology and GIA oversight. Likewise, the new Government Analytical Unit could provide the necessary methodological checkpoint for conducting GIAs. An important first step is to ensure the availability of gender expertise within these structures (Chapters 5 and 7).

The GFPs system supports gender mainstreaming but efforts should be made to ensure that it is fit for purpose. Given the uneven application of the Standard for GFPs, strengthening its status and scope could be considered to allow for consistent application of the standard across line ministries. An updated standard can better define centre of responsibility as opposed to centre of expertise for gender mainstreaming within line ministries, with reinforced personnel capacities devoted to the co‑ordination of the gender equality goals and gender mainstreaming.

Sustainable financing mechanisms that can help ensure continuity of the gender equality policy can provide the necessary medium to long-term perspective to advance on removing deeply rooted gender inequalities. Options include the pooling of resources across teams with responsibilities to support the advancement of the gender equality agenda.

Developing systematic training modules on gender mainstreaming can help overcome the limitations related to low capabilities across the government to implement this strategy. There is scope to consider measures to ensure that at least one public servant within every relevant unit receives adequate training in gender mainstreaming tools and in gender equality topics in the given policy areas. Introducing mobility opportunities within the public administration, for example through secondments or job shadowing to facilitate skills transfer, could also be an option.

References

[21] Audit Commission (2008), Clarifying Joint Financing Arrangements, http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/829/Clarifying%20Joint%20Financing%20Audit%20Commission%204Dec08.pdf.

[26] Australian Public Service Commission (2021), Current mobility programmes, https://www.apsc.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/aps-mobility-framework/current-mobility-programs.

[20] Communities and Local Government (2010), Guidance to local areas in England on pooling and aligning budgets, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/8313/1508565.pdf.

[25] Department of Finance (2021), Secondment arrangements and procedures for Commonwealth employees, https://www.finance.gov.au/secondment-arrangements-and-procedures-commonwealth-employees-rmg-121 (accessed on February 2023).

[24] European Institute for Gender Equality (2022), Training ministries in gender mainstreaming (2007-2011), https://eige.europa.eu/lt/gender-mainstreaming/good-practices/finland/training-ministries-gender-mainstreaming (accessed on February 2023).

[6] Federal Chancellery Republic of Austria (n.d.), About Division for Women and Equality, https://www.bundeskanzleramt.gv.at/en/agenda/women-and-equality/about-division-for-women-and-equality.html (accessed on February 2023).

[11] Government of Iceland (n.d.), Equality, https://www.government.is/topics/human-rights-and-equality/equality/ (accessed on February 2023).

[12] Government of Sweden (n.d.), Organisation of the Ministry of Employment, https://www.government.se/government-of-sweden/ministry-of-employment/organisation-of-the-ministry-of-employment/ (accessed on February 2023).

[13] Government of Sweden (n.d.), Swedish Gender Equality Agency, https://www.government.se/government-agencies/swedish-gender-equality-agency/ (accessed on February 2023).

[16] Government of the Czech Republic (2023), Annual Reports on Gender Equality 1998-2022, https://www.vlada.cz/cz/ppov/rovne-prilezitosti-zen-a-muzu/dokumenty/souhrnne-zpravy-o-plneni-priorit-a-postupu-vlady-pri-prosazovani-rovnych-prilezitosti-zen-a-muzu-za-roky-1998---2018-123732/ (accessed on February 2023).

[3] Government of the Czech Republic (2023), Zmocněnkyně vlády pro lidská práva (Government Commissioner for Human Rights), https://www.vlada.cz/cz/ppov/zmocnenec-vlady-pro-lidska-prava/zmocnenecnenkyne-vlady-pro-lidska-prava-15656/ (accessed on April 2023).

[10] Government of the Czech Republic (2022), Statut Rada vlády pro rovnost žen a mužů (Mandate of the Government Council for Gender Equality), https://www.vlada.cz/assets/ppov/rovne-prilezitosti-zen-a-muzu/Statut-Rady-2022.pdf.

[17] Government of the Czech Republic (2021), Reporting on the Implementation of the Standard of GFP position in 2021 (unpublished).

[7] Government of the United Kingdom (n.d.), Government Equalities Office, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/government-equalities-office.

[22] Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland (2022), Gender mainstreaming, https://stm.fi/en/gender-equality/mainstreaming (accessed on February 2023).

[23] Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland (2013), Gender Glasses in Use a handbook to support gender equality work at Finnish ministries, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/74721/rep_memo201312_genderglasses.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on February 2023).

[1] OECD (2023), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Czech Republic: Towards a More Modern and Effective Public Administration, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/41fd9e5c-en.

[18] OECD (2022), OECD Questionnaire on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance in Czech Republic.

[4] OECD (2022), “C/MIN(2022)7”, in Report on the Implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations: Meeting of the Council at Ministerial Level, 9-10 June 2022, https://one.oecd.org/document/C/MIN(2022)7/en/pdf.

[8] OECD (2021), Survey on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance.

[2] OECD (2019), Fast Forward to Gender Equality: Mainstreaming, Implementation and Leadership, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9faa5-en.

[14] OECD (2017), Centre Stage 2: The Organisation and Functions of the Centre of Government in OECD Countries, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/report-centre-stage-2.pdf.

[15] OECD (2016), “Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Public Life”, OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0418, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0418.

[9] Office of the Government of the Czech Republic (2021), Organizational Rules of the Office of the Government.

[5] the Australian Government (n.d.), Office for Women, https://www.pmc.gov.au/office-women (accessed on February 2023).

[19] UN (2010), Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women: Czech Republic, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, United Nations, New York, https://www.vlada.cz/assets/ppov/zmocnenec-vlady-pro-lidska-prava/rovne-prilezitosti-zen-a-muzu/cedaw/concluding_observations_47th_Session_ENG.pdf (accessed on November 2022).

Notes

← 1. Between 2007-10 and then from 2014-17, the position of Minister for Human Rights was vested with the responsibility for gender equality portfolio. During 2017-18, this responsibility was covered under the portfolio of the Minister for Justice.

← 2. The first was Government Resolution No. 4569 in May 2001; the second was Government Resolution No. 414 of May 2017.

← 3. Full-time equivalent or FTE is a unit to measure of the number of hours a full-time employee works for an organisation.

← 4. In the Czech Republic, the internal comment procedure is one of the key moments in the policymaking cycle that offers an opportunity to integrate a gender perspective in the development of a legislative or non-legislative documents by line ministries. This can be done by ensuring adequate gender expertise of the ministry personnel who are involved in the design of the document, or through the involvement of the GFP. However, the GFP also can comment on it through informal processes or with the agreement of the GFP’s superiors once the document is approved.