This chapter provides key considerations and steps for a competition authority to apply a gender lens in its day-to-day work. It explains the importance of gathering disaggregated data to understand when and how diverse groups of people are harmed, and how the use of surveys can give better insights into consumer behaviour. It shows how a gender lens can be applied to market definition and competitive effects analysis, cartel investigations, compliance and advocacy, prioritisation of decisions and ex-post evaluation. Finally, this chapter discusses the need for remedies to be tailored to correct or offset harm to a specific disadvantaged group. It emphasises that targeting stakeholder engagement is key to ensuring inclusivity. Diversity and inclusion should be considered at the institutional level to enhance decision-making. It concludes with a checklist for a gender inclusive competition law and policy (Annex A).

Gender Inclusive Competition Toolkit

3. Key insights

Abstract

The research stemming from OECD work on gender inclusive competition can be distilled down to the following key insights that will be subsequently expanded upon.

Gender is an additional relevant feature worth considering in competition analysis.

Gendered analysis1 provides competition authorities with information to make better and more tailored decisions.

Gendered analysis is more relevant in markets where products are offered to end consumers.

Disaggregated data is critical for gendered analysis. Without data disaggregated specifically for gender, there is no way of knowing whether there are, or are not, gendered effects. Data should be disaggregated to the extent that it reveals gender while protecting other identifiers.

Building on the concept of the double dividend,2 remedies that factor in gender considerations may not only improve competition outcomes, but they can also help address gender inequality in markets.

Different gendered effects may not be immediately obvious. Further analysis of markets including market definition, conduct and firms may be necessary.

A gendered analysis of mergers could reveal poorer outcomes for female consumers or women- run businesses.

Gender diversity can be an important variable of collusion, in that cartels are more likely to form in homogenous groups with repeated formal or informal interactions.

Regarding cartels, compliance and outreach efforts should include discussions on why repeated interactions among homogenous groups present an increased risk of cartel behaviour for companies

Diversity can strengthen competition authorities.

Where public interest considerations are available to competition authorities, gender should be among them.

Data

Reliable analysis depends on the quality and extensiveness of the data collected. Disaggregated data by gender allows authorities to determine if indeed gender is a factor to be taken into consideration or if, on the contrary, it can be put aside.

Types of data and data sources

Competition authorities need disaggregated data by gender to understand, if, when and how diverse groups of people could be harmed disproportionately, including women. Gendered data is a good starting point. However, having a broader set of data is even better, as additional demographic data can be used to control for other characteristics.

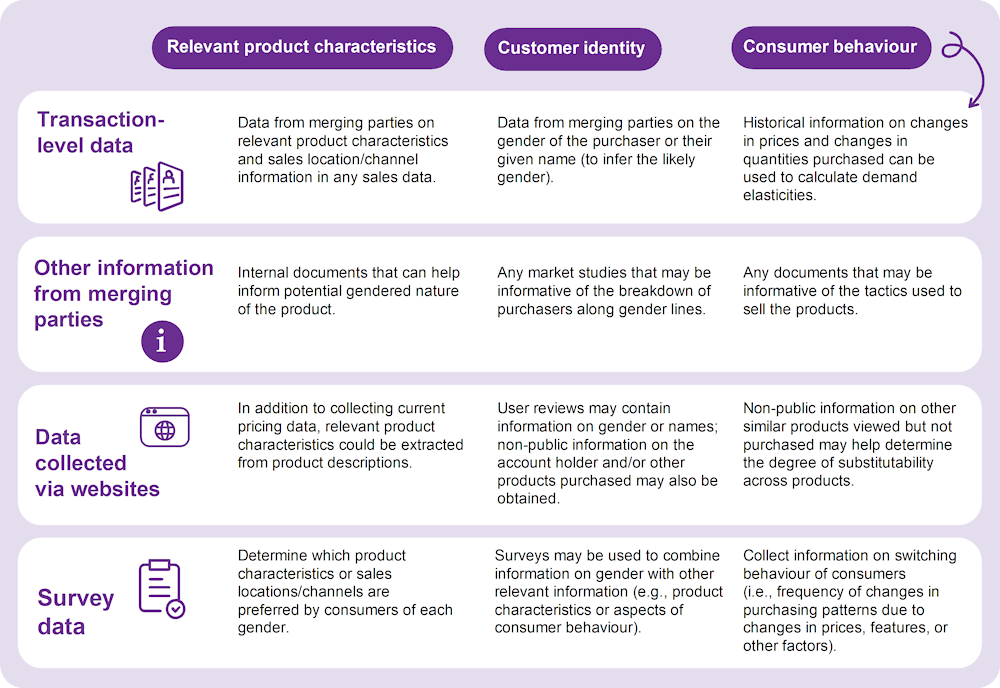

When considering the question of data, for example, in merger review or monopolistic practices, there are four main sources of information: transaction level data, other information from the parties, publicly available data collected via websites and survey data. These would be relevant for competition analysis for any consumer facing markets. These sources, summarised in Figure 1, can be used to understand relevant product characteristics, consumer identity and consumer behaviour.

Useful gendered data may also be available from other law enforcement agencies. Competition authorities may also wish to consult other agencies to see if they are using gender-based data or are implementing gender- based considerations in their work.

Figure 1. Sources to consider for the application of a gender lens in merger reviews

Source: Adapted from Pinheiro et al. (2021, p. 10[4]), Gender considerations in the analysis of market definition and competitive effects: A practical framework and illustrative example, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/gender-inclusive-competition-proj-2-analysis-market-definition-and-competitive-effects.pdf.

In some cases, where gendered data is not available, authorities can infer the gender of consumers. This is not as precise as gathering specific gendered data but may be a good proxy for initial analysis. Competition authorities can request information on product characteristics, product marketing and product sales channels using their compulsory information gathering tools. This information may also be publicly available. Authorities can also examine additional information online, such as the profile of online reviewers to see if they are primarily of one gender. Finally, authorities, who are equipped, can use predictive tools3 to assist with inferring gender from names, where it is not otherwise obvious.

Competition authorities can also help generate data for future research on the intersection between gender and competition. Whenever possible, authorities could include gender in published decisions, as well as explaining the interpersonal relationships (formal and informal) between individuals who participated in cartels.

Surveys

Surveys can be used to better understand consumer behaviour, including factors such as:

what product attributes are most valued

if there are differences in frequency of buying and differences in volume bought

price sensitivity and awareness

overall switching levels.

Surveys can also gather data effectively for gendered analysis by including questions, specifically on gender. Collecting a broader range of data enables an authority to focus on certain characteristics, control for identity factors and thus confirm if an effect in a market is due to gender or some other identity factor. Furthermore, tailoring surveys to the needs of the review or investigation ensures authorities collect the right data. If gender is collected at the beginning of the survey, the results can then be analysed by gender and compared to see if there are differences.

There may be differences between revealed versus stated preferences. This can influence responses, so it is important to include questions that reveal both, such as questions about past practice and hypothetical situations.

Market definition and anticompetitive conduct

Market definition and competitive effects analysis

Thinking about market definition and competitive effects analysis along gendered lines helps competition authorities understand who is affected by anticompetitive conduct and to what extent. It is then possible to evaluate whether one group of consumers is better off than another, and if that needs to be corrected or prevented. Gender can influence:

consumer preferences, for example whether a consumer sees a product as complementary or substitutable

price‑sensitivity

switching behaviour.

Supply- and demand-side factors

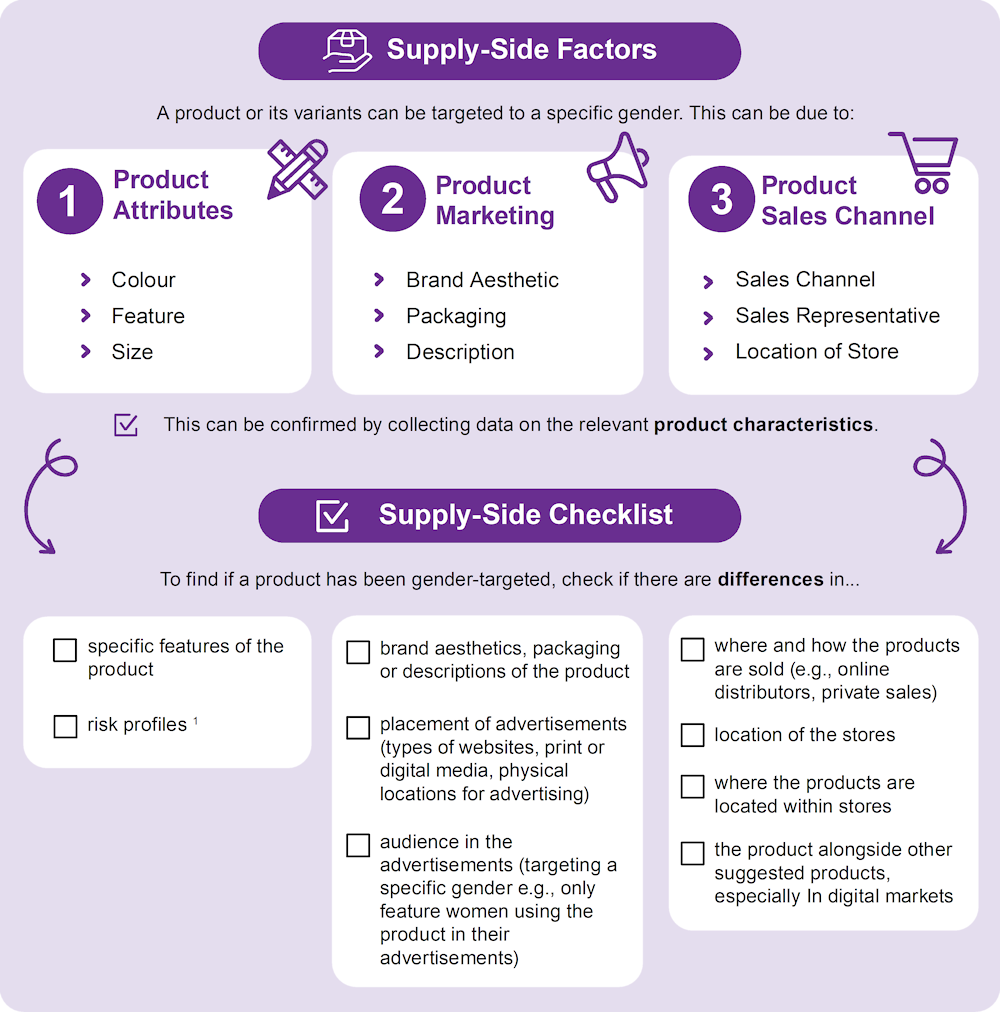

Supply- and demand-side factors can be applicable for gendered analysis of competitive effects. These factors are relevant for market definition and competitive effects analysis. Competition authorities can look at both supply-side factors and demand-side factors when applying a gender lens.

Supply-side factors include product attributes, product marketing and product sales channels to see if firms are targeting a specific gender.

Figure 2. Supply-side factors and checklist

1. Economic research shows that there are gender differences in risk preferences, competitive preferences, and altruism. See Croson, Rachel and Uri Gneezy (2009, pp. 448-474[5]), “Gender Differences in Preferences.” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 47, No. 2, pp. 448‑474.

Source: Adapted from Pinheiro et al. (2021, pp. 8-9[4]), Gender considerations in the analysis of market definition and competitive effects: A practical framework and illustrative example, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/gender-inclusive-competition-proj-2-analysis-market-definition-and-competitive-effects.pdf.

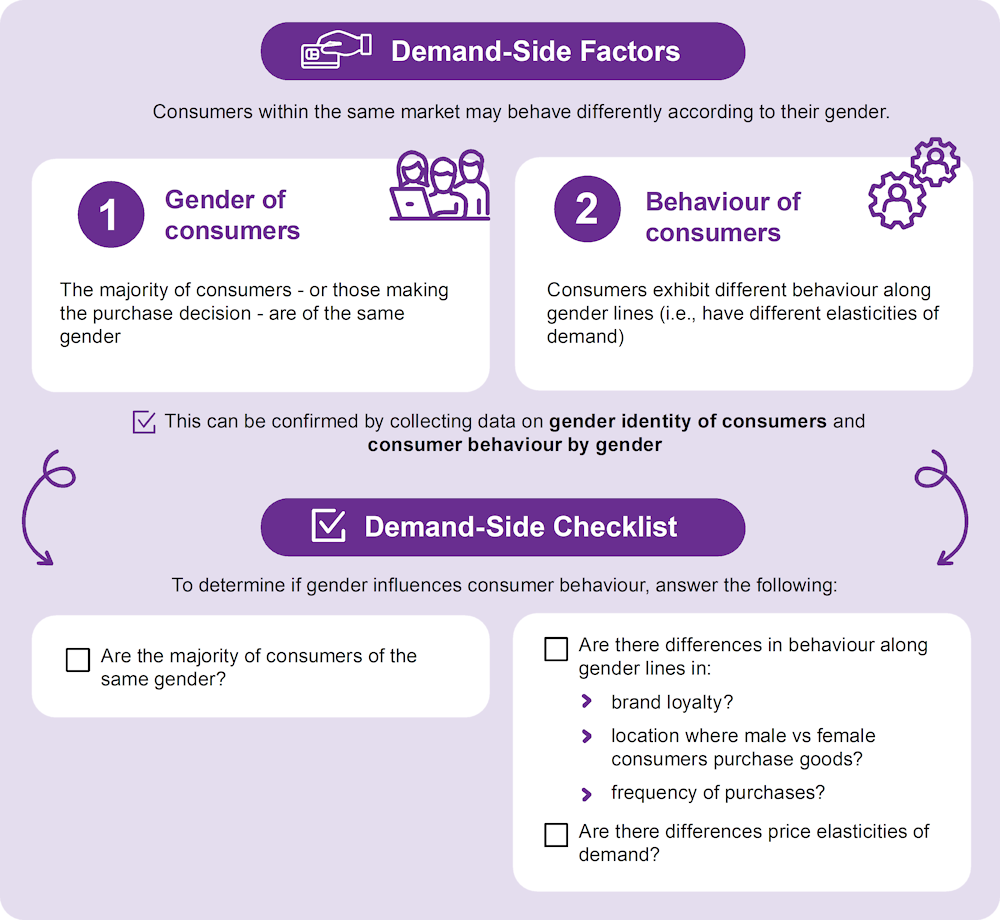

There are also important demand-side factors to consider, such as the identities of consumers, and if consumers exhibit different behaviour.

Figure 3. Demand-side factors and checklist

Source: Pinheiro et al. (2021, pp. 8-9[4]), Gender considerations in the analysis of market definition and competitive effects: A practical framework and illustrative example, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/gender-inclusive-competition-proj-2-analysis-market-definition-and-competitive-effects.pdf.

Framework for assessing firms’ ability to differentiate by gender

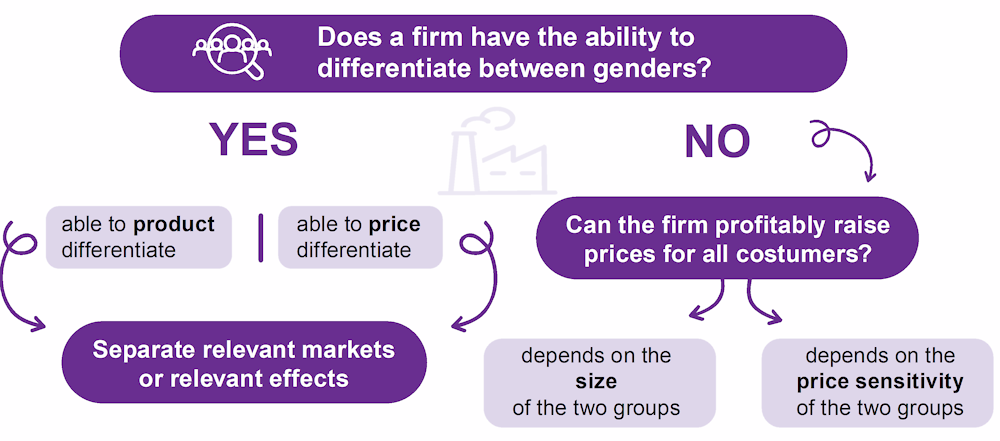

Competition authorities can also assess the ability of firms to differentiate between consumer groups, the relative size of these groups, and the extent of switching after a price increase. The following framework indicates if firms could differentiate between genders.

Figure 4. Framework for assessing firms’ ability to differentiate by gender

Source: Based on Oxera (2021, p. 8[6]), Gender in competition analysis, 7 October 2021, https://www.slideshare.net/OECD-DAF/oecd-gender-inclusive-competition-policy-project-key-findings-from-oxera-on-gender-differences-in-surveys-for-market-definition-and-merger-analysis-october-2021.

The diagram above explains the potential effects if a firm is able to differentiate by gender. If yes, competition authorities need consider if the firm is able to differentiate by product or price. If this is the case, there may be separate relevant markets or separate relevant effects. In this case, gender can be included as one of the variables to consider when assessing competitive effects.

If a firm is not able to differentiate by gender, then competition authorities should consider if the firm is able to profitability raise prices for all consumers. That will depend on the size of the groups (i.e. number of male vs female consumers), and their respective price sensitivities. If the more price sensitive group is large enough, it can protect the others from adverse competitive effects. In practice, authorities must assess factors like substitutability by subgroups of consumers, and then compare that to consumers in aggregate.

For example, conducting the SSNIP test4 and critical loss analysis for each specific group can be used to define the market and determine the effects of a merger on the different groups of consumers. As noted above, gendered analysis can be done whenever data is available. In practice, this means that men and women should be considered separately and then in aggregate to see if firms can increase the price profitability post-merger. These can then be weighted to reflect the size of groups; but the analysis should follow the diversity of the sample, rather than the diversity of the population. The results should determine if a firm is able to increase prices for some or all consumers.

Diversion ratios are another tool to assess willingness to switch by gender. If differing diversion ratios are present, competition authorities could investigate if the firm is able to differentiate their offerings based on gender. If firms can apply different prices for different groups, then merger effects should be considered by gender. If firms cannot apply different prices to different groups, then size of the groups and their respective price sensitivities will determine if one group is able to protect the other. If one group is protecting another, then authorities do not need look into separate competitive effects or remedies.

Competition authorities can analyse disaggregated data to see if gender is the driving factor for different preferences and price elasticities of demand that lead to different switching behaviour. This can vary depending on the product or service being investigated or reviewed, but in some cases will lead to gender-segmented markets. Where gendered data is available, competition authorities can run their usual analysis, but do so for men and women separately, and then all consumers in aggregate.

Gendered markets and case studies

Gendered effects are present in many sectors such as toys, clothing, personal care products, health care products, dry cleaning, hair cutting services, insurance, financial products. These are more likely to have gender-segmented markets and different associated competitive effects. If competition authorities do not have the capacity or resources to systematically consider gender when determining market definition and analysing competitive effects, the markets outlined above are good markets to prioritise for gendered analysis as they have known gendered effects.

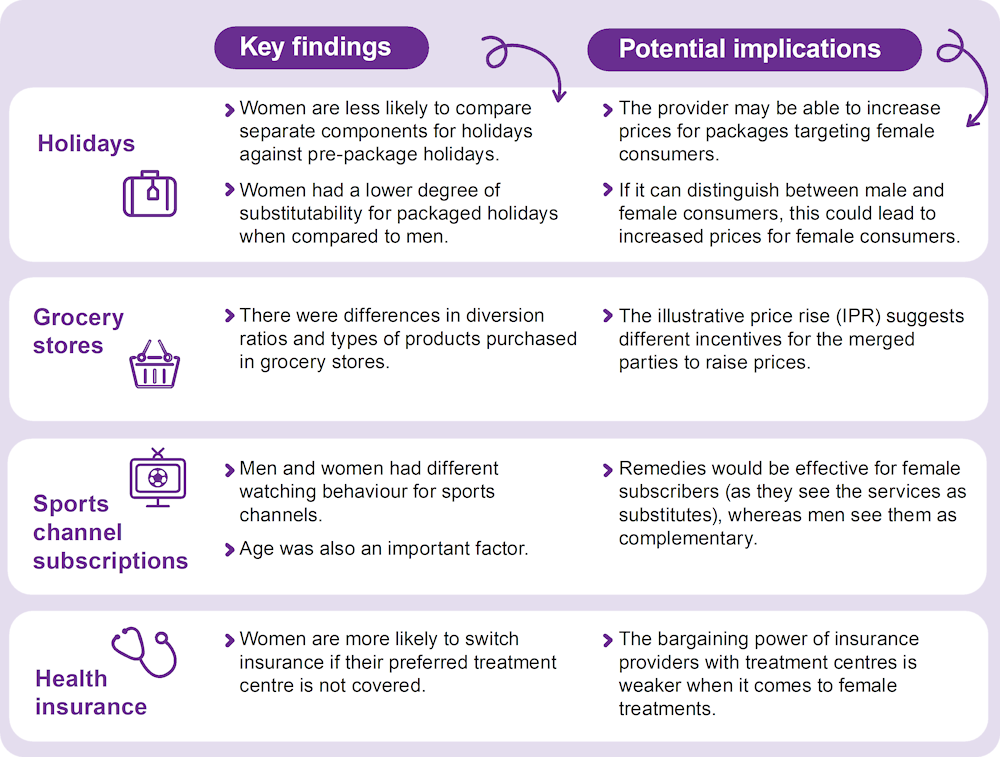

If competition authorities have the necessary capacity and resources, it is best to do gendered analysis whenever relevant and data is available. Analysis of past surveys related to mergers and market studies demonstrate that there can be significant gender differences in terms of substitution, consumer preferences and switching behaviour. The markets concerned in this analysis did not exhibit any obvious gendered differences until consumer behaviour was examined. These past survey case studies looked at three areas of consumer behaviour that are relevant for market analysis. These areas are price sensitivity, preferences for substitutes and willingness to switch.

Figure 5. Key findings from survey review

Source: Adapted from Oxera (2021[7]), Gender differences in surveys for market definition and merger analysis, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/gender-inclusive-competition-proj-1-gender-differences-in-surveys-for-market-definition-and-merger-analysis.pdf

Remedies

In markets where the tools outlined above reveal differences in behaviour, competition authorities can then take that into account to determine the level of harm for specific groups and tailor remedies to correct or offset that harm. Competition authorities can also consider outcomes that target and improve the consumer welfare of the most negatively affected groups. Remedies that factor in gender considerations will not only improve competition outcomes, but they can also help address gender inequality in markets. Stakeholder views, particularly those of affected groups, should be considered in the development of remedies. Authorities could also consider if it would be appropriate to “market test” proposed remedies with interested stakeholder groups.

Cartels and collusion

Cartel formation and investigations

Understanding the social context of cartel formation, and the dynamics of the group can support a more precise assessment of the incentives to enter and remain in a cartel. Homogeneity of characteristics amongst cartel members may facilitate cartel formation. The common identity bias instils a sense of trust and predictability in the group that helps enable cartel formation.5 In such a group, it is easier to believe that someone will act in a consistent way and be loyal to the group. Men and women are similar in terms of factors that predict involvement in white‑collar crime, but differ in terms of motivation and opportunity, due to women’s exclusion from male‑dominant informal networks. To date, however, there is no compelling evidence to believe that women would not do the same if the prevailing networks in professional environments were women’s networks rather than those of men.

When investigating and interviewing alleged cartelists, competition authorities can seek to understand the broader range of interactions and history between suspected individuals. “Boys’ clubs” can sustain cartel behaviour over time, as they reinforce and facilitate relationships between members. These kinds of relationships form at work, and in informal settings.6 Competition authorities should look beyond the formal work context during investigations.

Competition authorities could look at more informal networks such as alumni associations, local business groups, sports and cultural associations, or charities, where “boys’ clubs” can emerge. Social media profiles and other public sources (e.g. alumni associations or charity events) may be able to provide some of this information. Competition authorities should consider gender diversity when investigating groups of individuals suspected of engaging in cartel conduct and can discuss gender diversity of teams within companies as part of compliance efforts (see following section).

Compliance and advocacy

Factors such as social norms, personal relationships and peer pressure help create and maintain cartels. These factors are linked to corporate culture, but also broader industry culture. Industries most at risk for cartel behaviour usually present the same characteristics: significant social events in the margins of business meetings; participants are more homogenous with repeated and regular participation over time.

Competition authorities could direct advocacy efforts to relevant business associations of these at-risk industries explaining the compliance risks associated with informal networks and lack of gender diversity. Firms that opt to change representatives, inject diversity by paying attention to gender balances may be able to reduce the risk of cartel behaviour.

There is research that indicates that men and women may approach leniency and whistleblowing differently (Tilton, 2018[8]). Women may be more likely to whistle blow externally, e.g. to law enforcement agencies compared to men who may be more likely to do so internally. Regular interactions with networks of businesswomen may give insights into sectors with gender-based competition barriers and provide opportunities to promote leniency and immunity programmes.

Institutional considerations

Representation

Diversity can strengthen competition authorities for many of the same reasons it can strengthen boards. Decision making processes benefit from a diversity of perspectives that in turn can lead to better governance. Gender representation at different levels can benefit an authority, for example, authority heads; heads of principle operating units; committees or teams that set priorities and select projects; and case handling teams.

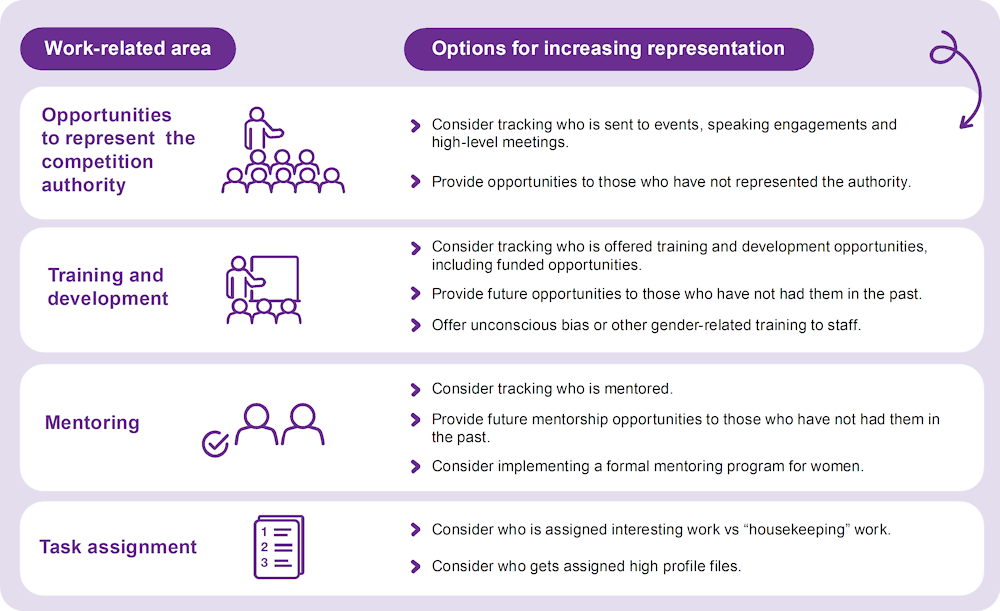

Competition authorities can also consider their outward facing representation, and who is given opportunities for career development. Considering who gets opportunities helps ensure a diverse pipeline of talent. Figure 6 provides some options to help track and increase representation over time.

Figure 6. Options for tracking representation

Stakeholder engagement and communication

Even with gender-balanced teams, it will remain difficult to fully understand how men and women experience the various outcomes of the work of competition authorities. Women face additional barriers in markets and may benefit more from competitive interventions. Targeting stakeholder engagement efforts to ensure inclusion of women, e.g. women’s business groups, will also help create a two‑way flow of information that could lead to complaints or tips for enforcement or compliance activities to address conduct affecting those communities. Authorities can use a range of engagement options from targeting specific groups to broad and inclusive public consultations. For example, competition authorities can:

Target women in relevant markets through surveys or focus groups.

Seek out women’s business groups in the relevant market.

Provide multiple timing options for public events, with in person and virtual attendance options.

Provide online engagement options, such as a dedicated feedback website or hotline.

Provide resources in multiple languages available to women who may be in a minority group.

While not all authorities will have similar formal powers, they can follow similar processes at the information-gathering stage of a review or investigation. International co‑operation can further support this approach.

Prioritisation

Competition authorities can consider the gender of those impacted by anticompetitive activity as an additional factor in the prioritisation process. For example, women-led businesses face difficulties in getting access to financing. Competition authorities can prioritise markets studies in finance‑related markets to review barriers and provide recommendations that would increase competition, but at the same time reduce barriers to entry for women-led businesses.

Enforcement priorities can also consider the gender structure of firms and target industries with lower levels of diversity in management positions. For example, the construction industry7 is known to have several compliance and cartel-related issues (e.g. bid-rigging) and is also known to be male dominated.8 When applying gender considerations, similar industries should be prioritised for enforcement and compliance work.

Competition authorities can also consider gender when prioritising market studies. Authorities can use market studies to determine whether key markets for women are working well.9 Targeting services traditionally supplied by unpaid female labour and other key markets for women could lead to increased competition while also reducing barriers that prevent women from participating in markets. OECD research identified key sectors for women’s participation in markets, including childcare, elder care, infrastructure, and financial markets.

Ex-post evaluation

Ex-post evaluation is an important tool for understanding the effects of earlier decisions and whether they aligned with expected outcomes. Ex-post evaluation allows authorities to understand how factors like prices, quality, variety, innovation, and entry have changed over time. Ex-post evaluation can help improve decision making, assess the effectiveness of tools, verify assumptions, and improve design and implementation of remedies.

Lessons learned from the evaluation process can also be used to provide insights on how gender was incorporated in the past. Ex-post evaluation may reveal approaches and methods of analysis that are useful for gendered analysis and could be used in future matters. This kind of evaluation is not just for cases. It can also be used to analyse complaints.

If there is insufficient information available on past cases, complaints, and resource requests, it would be worthwhile to find ways to integrate information gathering and tracking into existing processes. This could increase the information available for future ex-post evaluation. One option is to include a section on gender considerations in templates (e.g. documents and staff papers) and to add gender and other identity factors into forms so the data is automatically tracked. Another option is to encourage management to ask about gender considerations as part of the decision-making processes (e.g. when deciding to investigate a matter or to pursue a market study).

Co‑operation

Further research, policy discussions and application of this Toolkit are needed to strengthen the understanding of gender-inclusive competition policy. Continued co‑operation among competition authorities and with international organisations can enhance knowledge and the development of best practices, much as it has been done in other areas of competition, such as merger control.

Competition authorities and their governments can seek opportunities to push for the inclusion of gender-related commitments in relevant recommendations, memoranda of understanding and agreements related to competition, as well as trade agreements. This can provide a framework for ongoing information exchanges on best practices for gender considerations.

Notes

← 1. For a definition of “gendered analysis” see: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/methods-tools/gender-analysis.

← 2. OECD (2018, p. 33[15]) explain that “by promoting competition in certain markets, competition authorities may reduce market distortions in a particular market (first dividend) and contribute to reduce gender inequality (second dividend).”

← 3. See, for example, Malmasi, Shervin and Mark Dras (2014, pp. 145-149[23]).

← 4. SSNIP tests are used to determine the smallest market in which a hypothetical monopolist could impose a small but significant non-transitory increase in price (SSNIP).

← 5. Abate and Brunelle (2021, p. 9[20]) explain that “[c]ommon identity bias refers to the fact that people belonging the one specific group usually prefer to work and interact with other people belonging to the same group”.

← 6. Abate and Brunelle (2021, p. 11[20]) explain that “[a]t its core, a “boys’ club” is an organisation recruiting and selecting men who then create a circle of solidarity both horizontally, among peers, and vertically, through mentoring relationships between junior and more senior members. An essential element of this definition is the fact that “boys’ clubs” are based on relationships that are in no way confined to the boundaries of the employing company. Men belonging to one of such networks meet each other in a variety of contexts: university, company workplace, business relationships, sport clubs, charities etc. Consequently, they create links and build personal loyalties they may prove stronger than the obligations due to one’s employer.”

← 8. See for example https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12147-020-09257-0.

← 9. The OECD Competition Assessment Toolkit provides guidance on how to remove barriers to competition in markets. It provides methodology for identifying unnecessary restraints on market activities and on how to develop alternative, less restrictive measures that still achieve government policy objectives. See https://oe.cd/cat.