This chapter outlines key trends and market practices of listed companies concerning corporate sustainability. It covers the regional and sectoral distribution of sustainability-related disclosures, common reporting standards and GHG emissions disclosure. Additionally, it explores how listed companies establish emission reduction targets and decide on third‑party assurance for sustainability-related information. The chapter examines financially material sustainability risks, the investor landscape, ownership patterns of top-emitting and environmentally innovative companies, and board responsibilities in managing sustainability issues. It also highlights the integration of stakeholder interests in corporate decision‑making and recent trends in sustainable bonds and climate investment funds.

Global Corporate Sustainability Report 2024

2. Market practices

Abstract

2.1. Sustainability-related disclosure

Information on a company’s sustainability-related risks and opportunities and how it manages them can be material for investors’ decisions to buy or sell securities, as well as to exercise their rights as shareholders and bondholders. Therefore, access to material sustainability information is crucial for market efficiency and for the protection of investors. Most regulators mandate or recommend the disclosure of sustainability matters (OECD, 2023, p. 23[2]). However, even in jurisdictions where sustainability disclosure is not mandatory, a significant number of companies have been reporting on sustainability risks and opportunities, driven by the interest from investors in the impact of environmental and social matters on companies’ financial performance.

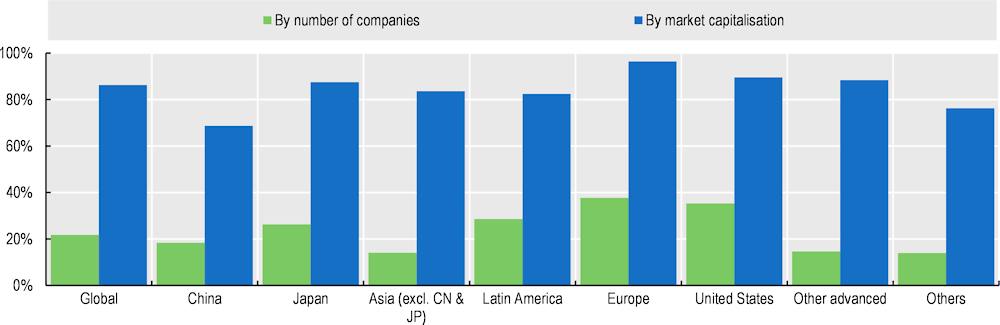

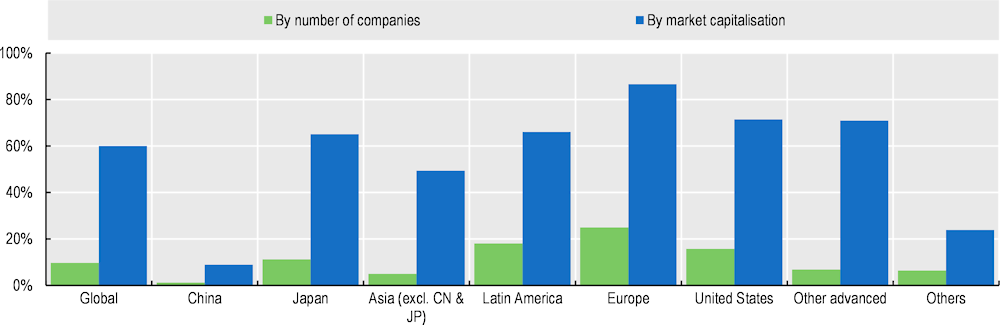

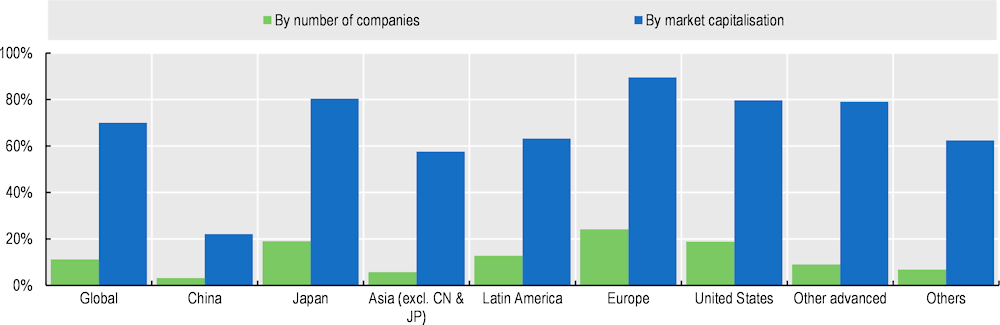

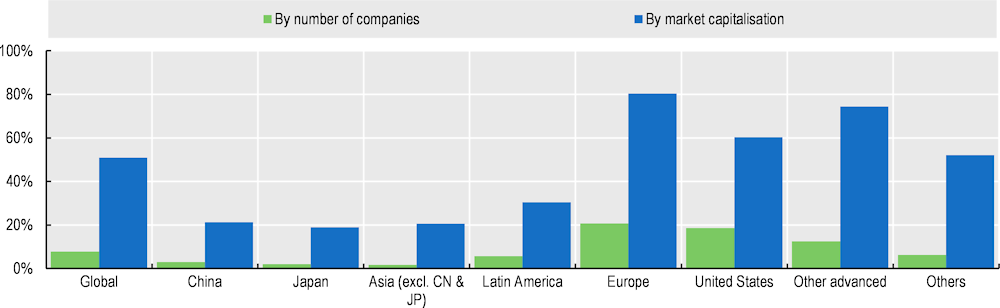

Out of the 43 970 listed companies globally with a total market capitalisation of USD 98 trillion, almost 9 600 disclosed sustainability‑related information in 2022 or 2023 (Figure 2.1). The companies that disclosed sustainability-related information represent 86% of the global market capitalisation. Among the 479 listed state‑owned enterprises globally, 441 disclosed sustainability‑related information in 2022 (the enterprises that disclosed such information represented 98% of the market capitalisation of all state‑owned enterprises).

Figure 2.1. Disclosure of sustainability‑related information by listed companies in 2022

86% of companies by market capitalisation disclose sustainable-related information globally

Considered by industry, the share of companies as a percentage of market capitalisation disclosing sustainability information in 2022 ranged from 78% to 91% globally. This share is the largest among extractives and minerals processing companies, and food and beverage companies, in which 91% and 90% by market capitalisation disclosed sustainability information, respectively (Figure 2.2, Panel B). The share of sustainability‑related disclosure by industry also varies by region. For instance, in the People’s Republic of China (China) companies representing 98% of the financial sector’s market capitalisation disclose sustainability information, compared to 75% in the United States and 76 in Latin America.

Figure 2.2. Share of companies disclosing sustainability information by industry

The disclosure of sustainability-related information varies across industries, especially in China

Public awareness and regulatory actions around climate change have accelerated in recent years. This has generated a greater interest by investors in companies’ GHG emissions. A reporting system is an important first step in any effort to reduce GHG emissions. It requires an accurate measuring, reporting and tracking system of the emissions resulting directly from the activities carried out by the company (scope 1), indirect emissions related to energy consumption (scope 2) and emissions generated in the supply chain or by companies financed by financial institutions (scope 3).

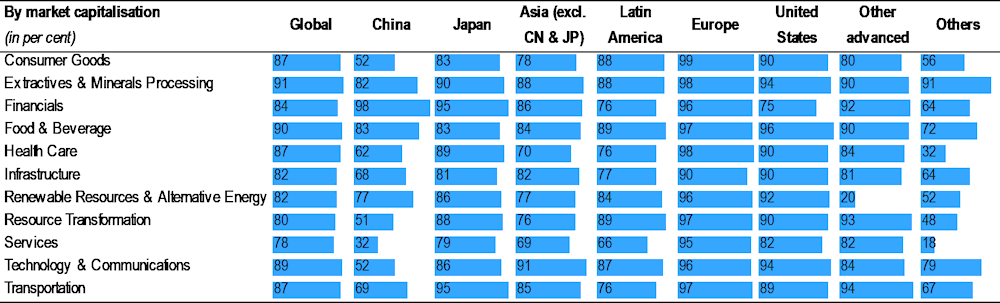

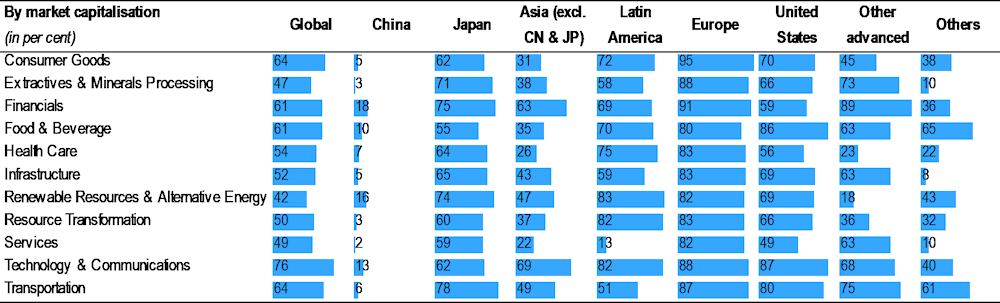

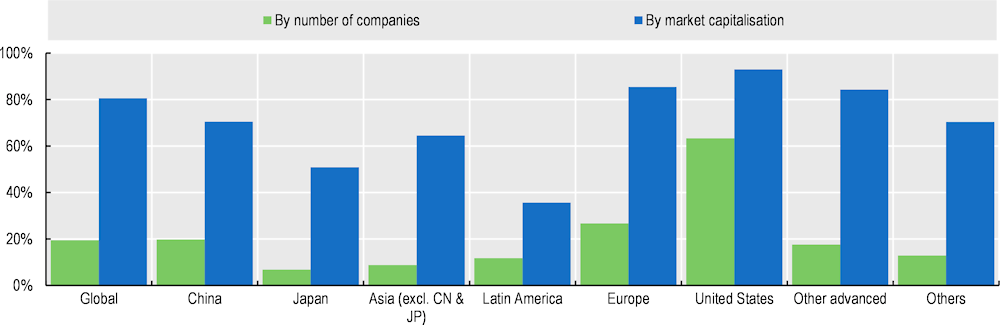

Globally, 6 308 companies representing 77% of market capitalisation disclosed scope 1 and scope 2 GHG emissions in 2022, ranging from 43% of companies by market capitalisation in China to 92% in Europe (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3. Disclosure of scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions by listed companies in 2022

Europe leads in scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions disclosure, but some other regions are close behind

Globally, extractives and minerals processing is the industry with the highest share of companies disclosing scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions by market capitalisation (85%), with an even higher share in Europe (97%) and a lower share in China (55%). In the United States, the industry with the largest share of companies disclosing scopes 1 and 2 by market capitalisation is food and beverage, with companies representing 94% of the industry’s capitalisation, while in the infrastructure industry less than 80% of the industry’s capitalisation reports this information (Figure 2.4, Panel B).

Figure 2.4. Share of companies disclosing scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions by industry

Extractives and Minerals lead in emissions disclosure by market capitalisation, while Infrastructure lags below 70% by market capitalisation

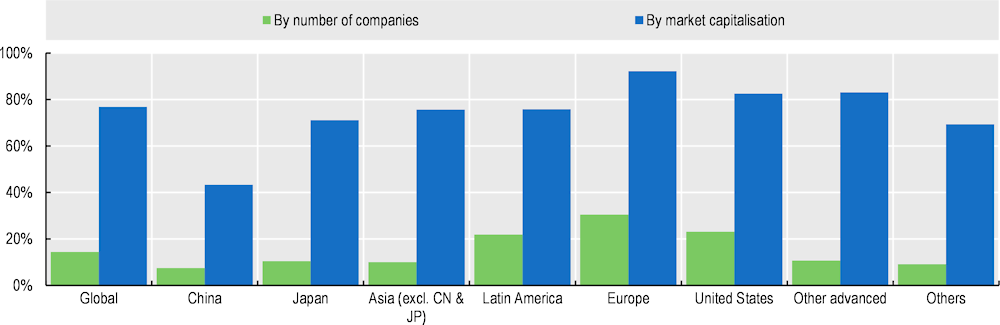

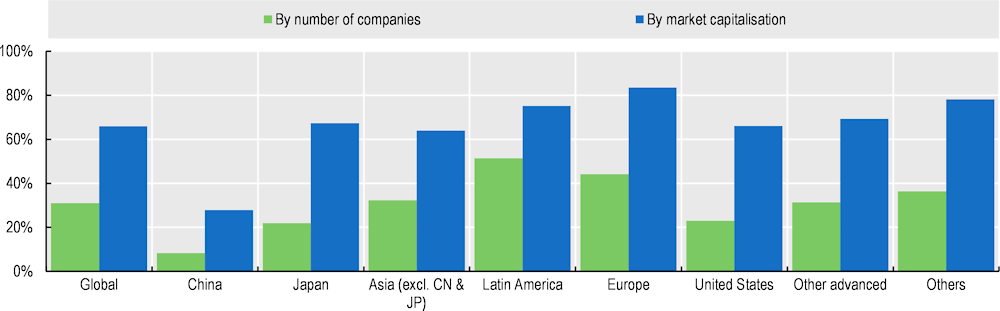

The disclosure of scope 3 emissions is 17 percentage points lower than the disclosure of scope 1 and scope 2 emissions (by market capitalisation) globally. In 2022, 4 246 companies (60% by market capitalisation) reported scope 3 emissions, ranging from 1 548 companies (around 87% by market capitalisation) in Europe to 60 companies (9% of market capitalisation) in China (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Disclosure of scope 3 GHG emissions by listed companies in 2022

Less than two-thirds of companies by market capitalisation disclose scope 3 GHG emissions globally

Globally, the technology and communications industry has the largest share of companies by market capitalisation that publish scope 3 emissions data. In Europe, 23% of the companies in the consumer goods industry, accounting for 95% of the industry’s market capitalisation, report such information, while in Japan the transportation industry has the biggest share of companies by market capitalisation disclosing scope 3 GHG emissions (78%). In China, the financial industry has the largest share of companies by market capitalisation reporting scope 3 GHG emissions (18%) (Figure 2.6, Panel B).

Figure 2.6. Share of companies disclosing scope 3 GHG emissions by industry

Scope 3 GHG disclosures vary across industries: Technology and Communications lead; Renewables lag

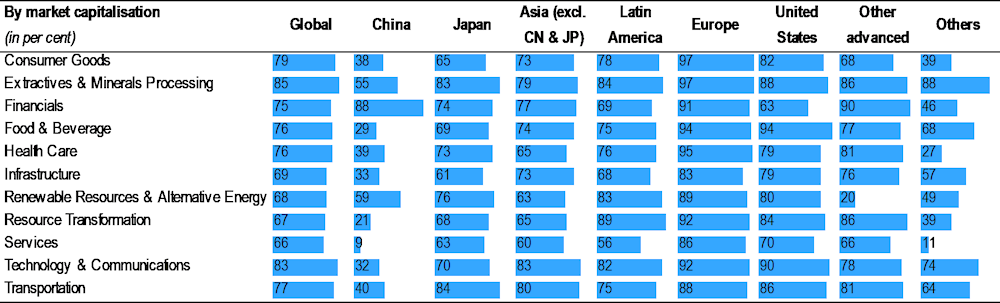

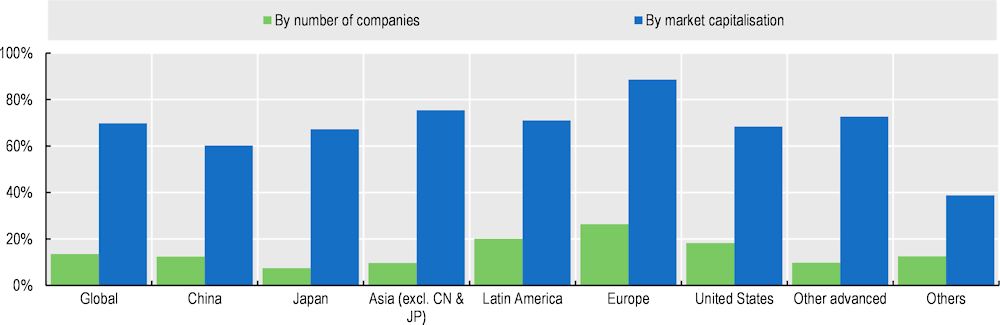

Although companies representing 86% of the world’s market capitalisation disclose sustainability reports, an external service provider assures the sustainability disclosure of only 66% of these companies by market capitalisation. This may reduce investors’ confidence in the information disclosed and the possibility of comparing reports between companies.

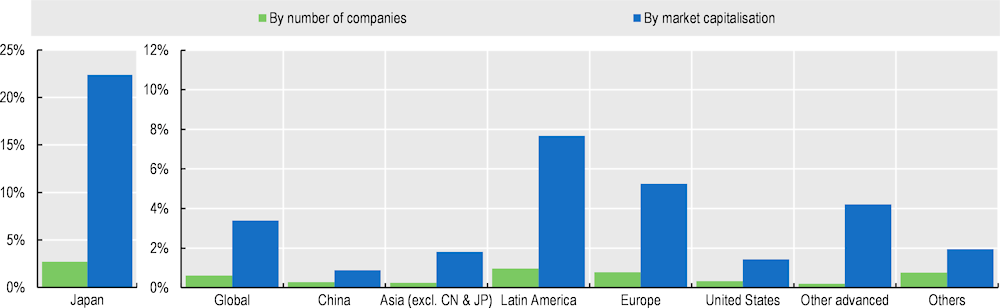

As shown in Figure 2.7, there is a significant difference between the shares of sustainability reports with assurance over all disclosed reports by the number of companies and by their market capitalisation. For instance, this is the case in China, with 8% of companies making up 28% of the market capitalisation, but also in Japan, where 22% of sustainability reports published by companies representing 67% of market capitalisation are verified by an independent assurance provider. However, in terms of market capitalisation, the share of companies requesting independent assurance is quite similar among regions, apart from China, regardless of whether the verification is mandatory. For instance, external assurance is mandatory for some companies in the European Union, India and Chinese Taipei, but neither in the United States nor most Latin American markets (TWSE, 2022[3]; SEBI, 2023[4]; OECD, 2023, p. 58[5]).

Figure 2.7. Sustainability reports with assurance over all disclosed reports in 2022

Global consistency: companies seek assurance, regardless of the existence of regulatory requirements

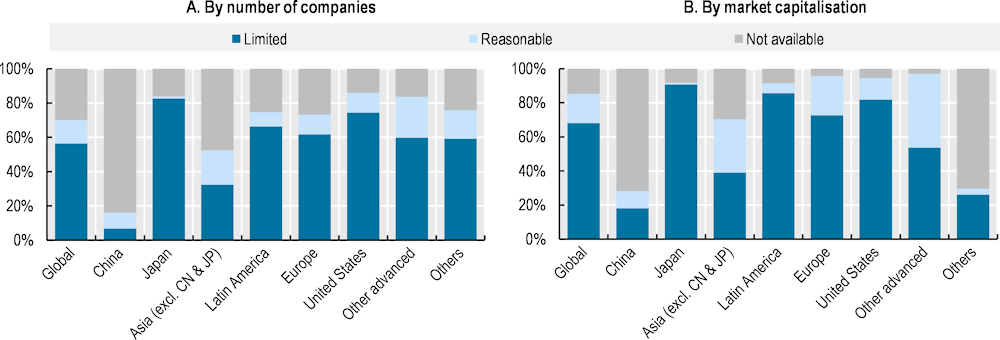

Based on the depth and the scope of the verification, the level of an assurance engagement can be defined as “limited” or “reasonable” according to the International Standard on Assurance Engagements (ISAE) 3000. Globally, in 2022, of 2 957 sustainability reports subject to an independent assurance, 1 668 were partially or fully verified under limited assurance, while 405 were partially or fully verified under reasonable assurance. In Japan, limited assurance was provided for 83% of the reports (from companies representing 91% of market capitalisation), followed by 74% in the United States (82% by market capitalisation) and 66% in Latin America (86% by market capitalisation). In China and Asia excl. China and Japan, limited assurance was provided for 7% and 32% of the sustainability reports, respectively. In contrast, reasonable assurance engagement of the sustainability report is rare (“reasonable” is the level required, as a rule, from the external auditing of financial reports). In Asia excl. China and Japan, 20% of sustainability reports were verified under a reasonable assurance, and in Europe and the United States around 12% (Figure 2.8, Panel A).

Figure 2.8. Levels of assurance over all assured sustainability reports in 2022

Reasonable assurance of sustainability reports remains uncommon

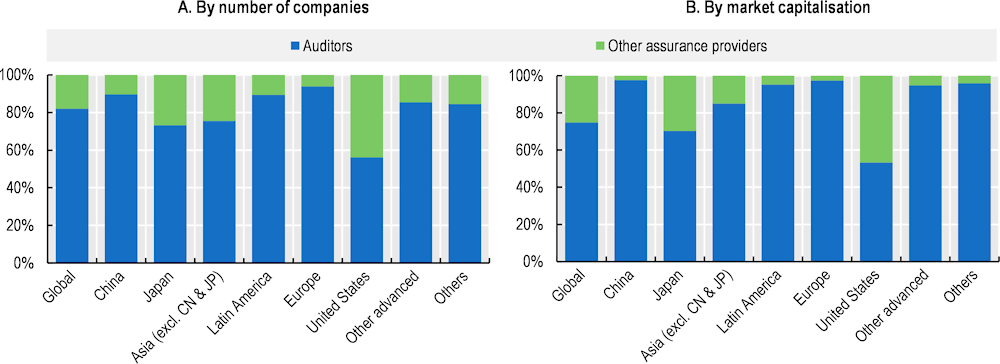

Among the companies that disclose the name of the independent assurance provider, 82% of sustainability reports with assurance were assured by an auditor (Figure 2.9, Panel A). Auditors assure an important share of sustainability reports in most regions. In Europe, 94% of assurance attestations are provided by auditors, and China (90%) and Latin America (89%) have similar shares. Only the United States significantly diverges from the global average, with 56% of assurance attestations developed by an auditor and the remaining 44% by other assurance providers.

Figure 2.9. Assurance of a sustainability report by auditors or other assurance providers

Auditors dominate the assurance market, except in the United States

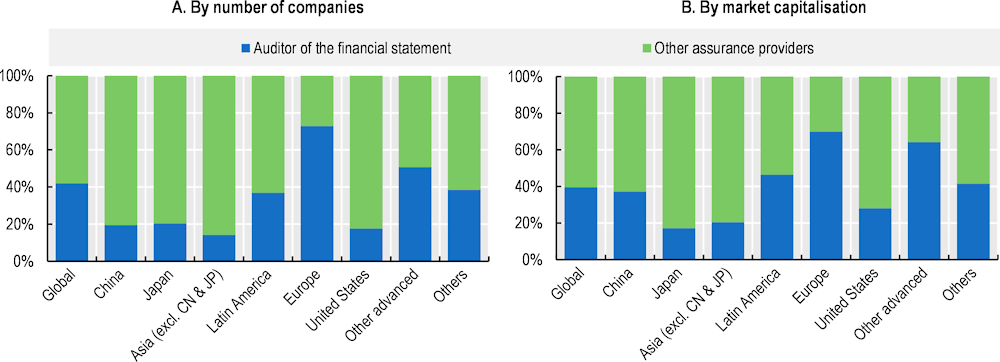

When looking at companies that disclose the name of the independent assurance provider, the share of companies that decide to engage the same auditor of the financial statement to verify their sustainability disclosures varies widely across regions. In Europe, 587 companies (70% of companies by market capitalisation) selected their financial auditor, while in Japan, the United States and Asia excl. China and Japan, companies tend to rely on other assurance providers, accounting for 80%, 82% and 86% of the market capitalisation, respectively (Figure 2.10, Panel B). The shares of companies hiring their financial auditor vary significantly between the European Union (83% of companies by market capitalisation), and the rest of Europe (44%).

Figure 2.10. Assurance of the sustainability report by the auditor of the financial statement in 2022

Hiring the auditor of the financial statement to assure the sustainability report is a common practice in Europe

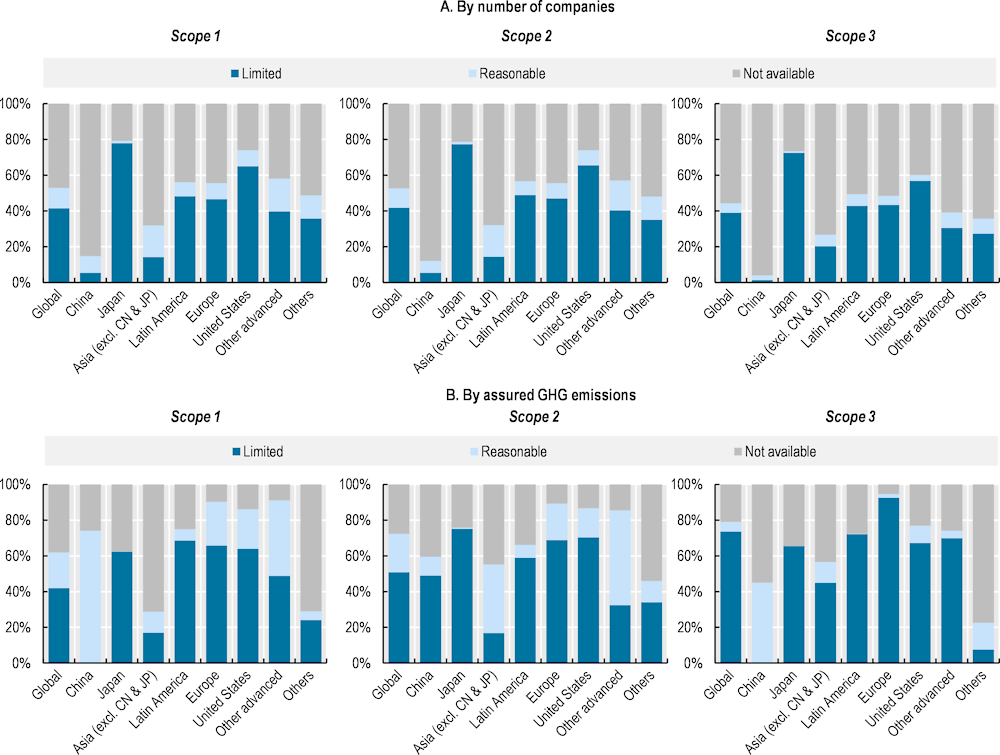

GHG emissions may be subject to a different level of assurance than the rest of the sustainability information. In all regions, GHG emissions are mainly verified with a limited level of assurance. Globally, out of the total GHG emissions verified by an independent assurance provider, limited assurance was performed on 42% of scope 1 emissions, 51% of scope 2 and 74% of scope 3 emissions. Only 11% of companies had a reasonable level of assurance for scope 1 and 2, and 5% for scope 3 (Figure 2.11, Panel A). Significant exceptions are China, where 74% of verified scope 1 GHG emissions were assured with reasonable assurance, and Asia (excluding China and Japan), where 39% of scope 2 GHG emissions were assured at a reasonable level, and 17% with a limited assurance. The assurance level for the verification of scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions is very similar across regions, with similar percentages for both limited and reasonable assurance, and slight differences for scope 3 GHG emissions verification.

Figure 2.11. Levels of assurance over all assured reports on GHG emissions in 2022

Only 11% of companies have a reasonable level of assurance for scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions globally

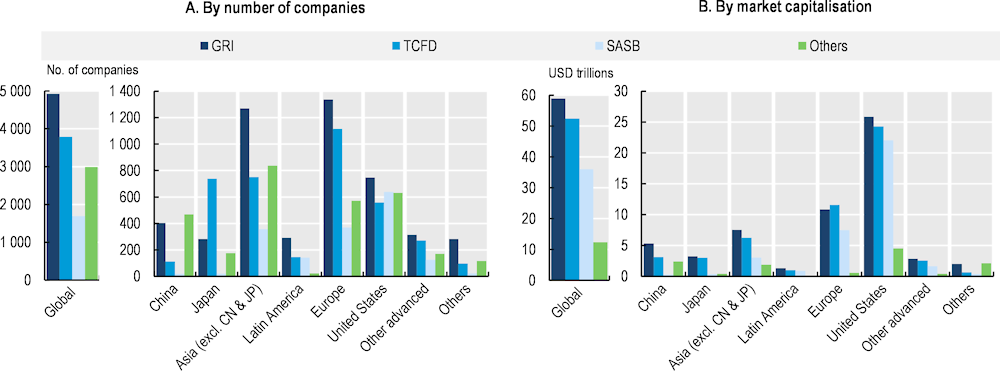

The comparability of sustainability-related information disclosed by companies in different jurisdictions enhances the efficiency of the capital market. In this regard, companies have been using different accounting standards and frameworks to disclose sustainability information. Globally, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards are used by 4 925 companies, accounting for 60% of global market capitalisation. Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations are used by 3 786 companies representing 54% of market capitalisation, and SASB Standards are used by 1 694 companies representing 37% of market capitalisation. Some of these companies use more than one standard or framework when reporting sustainability information (Figure 2.12).

In Europe and Japan, 1 114 companies (78% of market capitalisation) and 737 companies (56% of market capitalisation), respectively, fully or partially followed TCFD recommendations. SASB Standards are mainly used in the United States, where 639 companies use them to disclose sustainability information. However, almost all regions show a predominant use of GRI Standards in their sustainability reporting compared to other standards: 1 336 companies in Europe (73% of market capitalisation), 292 companies in Latin America (79% of market capitalisation), 403 companies in China (44% of market capitalisation) and 1 270 companies in the Asia excl. China and Japan (61% of market capitalisation).

Figure 2.12. Use of sustainability standards by listed companies in 2022

Larger companies tend to use global reporting standards, while smaller companies often use other frameworks

Globally, more than two‑thirds of the companies by market capitalisation disclose a GHG emission reduction target. In Europe, Japan and the United States, the share of companies is larger, representing 90%, 80% and 80%, respectively. Latin America (63%), Asia excl. China and Japan (57%) and China (22%) stand below the average (Figure 2.13).

Figure 2.13. Disclosure of GHG emission reduction targets by listed companies

More than two‑thirds of companies by market capitalisation disclose a GHG emission reduction target

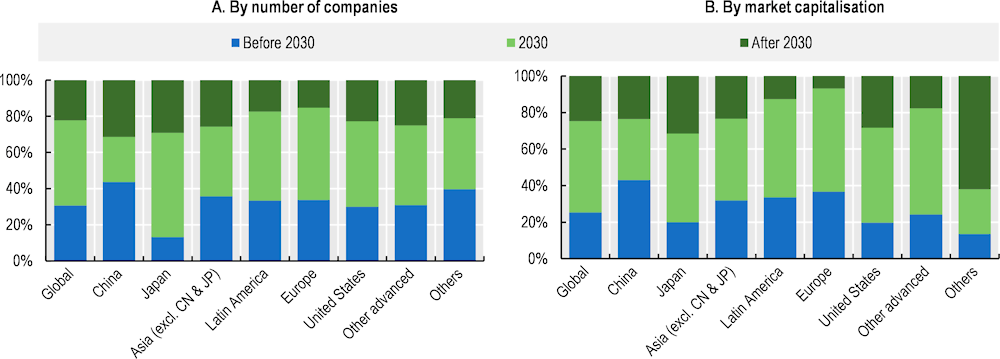

Nearly half of the GHG emission reduction targets reported by companies set 2030 as the target year (Figure 2.14). In Japan, 58% of companies (49% by market capitalisation), 51% in Europe (57% by market capitalisation), and 49% in Latin America (54% by market capitalisation) have committed to reducing their GHG emissions by 2030, while in China 44% of companies (43% by market capitalisation) have set their targets before 2030. Globally, only a small portion of the market by the number of companies discloses targets with a longer perspective, except the “Others” category where 62% of companies by market capitalisation set the target year after 2030.

Figure 2.14. Length of the existing GHG emission reduction targets by listed companies

Globally, 22% of companies set GHG emission reduction targets beyond 2030

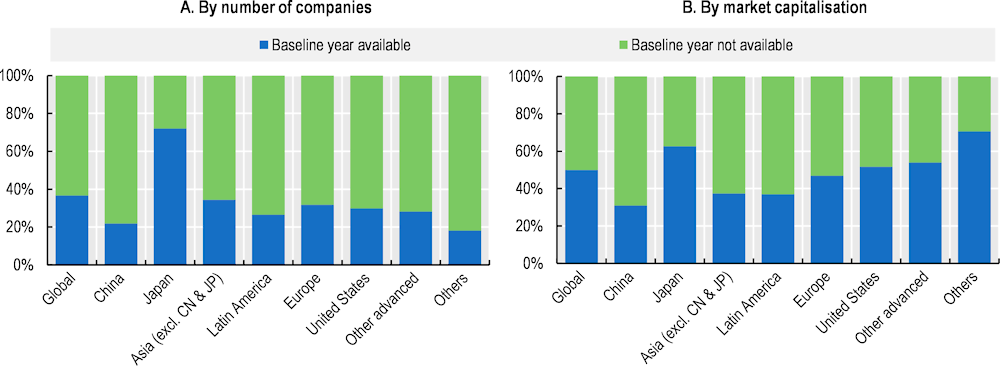

Globally, among the companies that set a specific year for their GHG emission reduction targets, the baseline year is available for only 37% of the companies in a widely‑used commercial database (Bloomberg). Remarkably, the main exception is Japan, where, out of 741 companies, 533 define a baseline year, representing 63% of market capitalisation (Figure 2.15). The base year is necessary for shareholders and stakeholders to assess what the GHG emission reduction targets (both in relative and absolute terms) effectively mean for an individual company.

Figure 2.15. Disclosure of a baseline year by listed companies with GHG emission targets

Investors often lack baseline data for assessing GHG emission targets

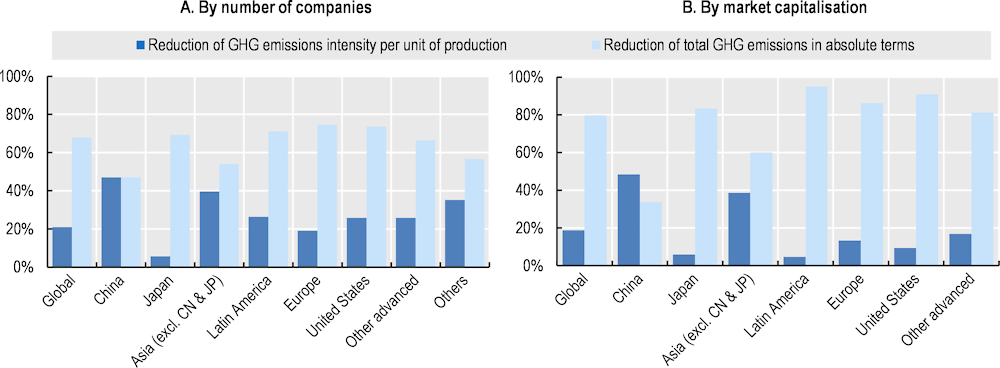

When setting GHG emission reduction targets, companies can select different metrics to measure the progress of their reduction path. Notably, most companies calculate the reduction of their GHG emissions over the baseline year either as the reduction of GHG emissions intensity for each unit of production or the GHG emission reduction in absolute terms. Globally, 21% of companies that have a target commit to reducing their GHG emissions intensity and 68% set a reduction target in absolute terms (Figure 2.16, Panel A). In Japan, reductions in absolute terms are used more often than in other regions, with 83% of companies by market capitalisation choosing them, against 6% choosing GHG emission intensity metrics. In Latin America, almost all companies that disclose a target with a baseline year (99% by market capitalisation) provide metrics with a strong predominance for reduction metrics in absolute terms (94%).

Figure 2.16. Metrics of the GHG emission targets by listed companies

Most companies with GHG emission targets set them in absolute terms

2.2. Investor landscape

Equity markets play a pivotal role in fostering innovation and facilitating long‑term investments, both of which are essential for sustainable economic growth. For the ordinary household, participation in these equity markets offers a dual benefit: it allows for a stake in value‑creating corporate activities and provides alternative avenues for financial planning and retirement savings. Therefore, understanding the interplay between corporations and sustainability within the framework of equity markets is crucial for a well‑rounded view of global sustainable development. The G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance aim to provide a framework that incentivises companies and their investors to make decisions and manage their risks in a way that contributes to the sustainability and resilience of the corporation.

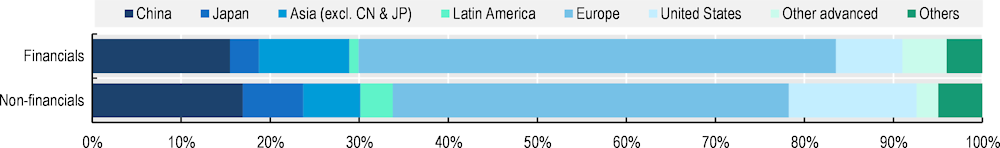

An analysis of the sustainability risks that companies are considered to be facing according to the SASB Sustainable Industry Classification System® Taxonomy (“SASB mapping”) shows that climate change is considered to be a financially material risk for listed companies that account for 64% of global market capitalisation (Figure 2.17). In particular, this risk is considered to be financially material for companies representing 70% of market capitalisation in Latin America, 66% in the United States, 59% in Japan and 55% in Europe. Human capital risks are currently the second most important sustainability risk with companies representing nearly 64% facing such risks as financially material. In the United States, this share is even higher, where companies representing 69% of market capitalisation are considered to face human capital risks as financially material.

Figure 2.17. The share of market capitalisation by selected sustainability risks in 2022

Climate Change and Human Capital pose financially material risks for most companies by market capitalisation

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg, SASB mapping. See Annex A for details.

Concerning sustainability risks, there are differences globally in the sensitivity to both ecological impacts and data security and customer privacy. Globally, companies representing only 13% of total market capitalisation are considered to face ecological impacts as a financially material factor. This share is even smaller in Japan (5%) but higher in Latin America with 20% (Figure 2.17). Globally, companies representing 36% of total market capitalisation are considered to face data security and customer privacy as financially material factors. In the United States, companies representing 45% of market capitalisation are considered to face data security and customer privacy as a financially material risk.

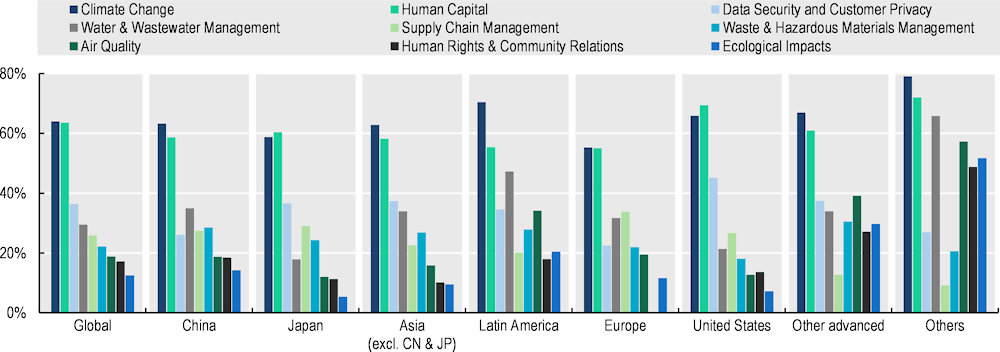

The analysis of the share of market capitalisation by all sustainability issues (Figure 2.18) reveals that product design and lifecycle management, with 54% market capitalisation share across 37 (out of 77) industries, emerges as a pivotal factor. Meanwhile, business ethics within the leadership and governance dimension is a risk considered to be faced by companies representing 31% of market capitalisation across 18 industries.

Figure 2.18. Indicators for sustainability issues where risks are likely to be financially material

Social risks are considered to be financially material for many industries

Note: The industry classification is according to SASB mapping.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg, SASB mapping. See Annex A for details.

Notwithstanding, mapping of the sustainability risks cannot be equated as the market value at risk, which would depend on an individual assessment of each company’s financial exposure to these risks. However, the share of market capitalisation can serve as a reference for policy makers to assess the differences in economic sectors’ distribution among locally listed companies that may justify priorities when supervising and regulating their capital markets (OECD, 2023[5]).

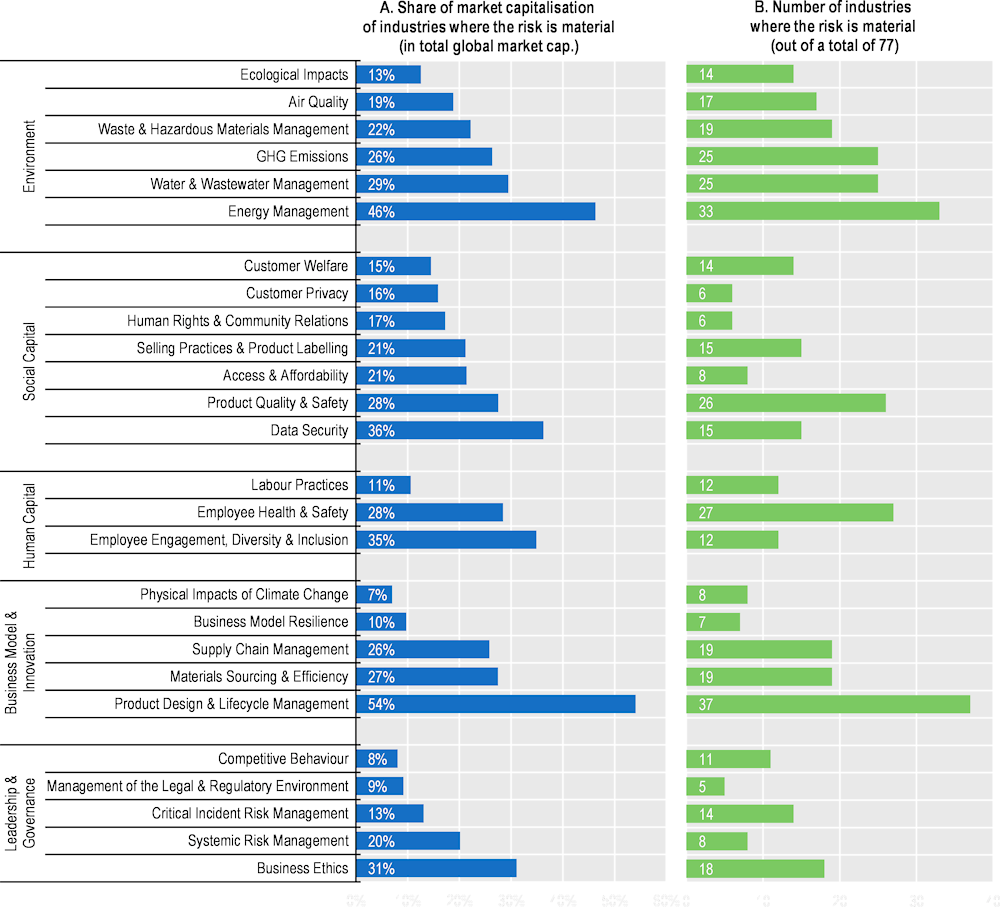

These findings acquire a critical dimension when considering the 100 listed companies with the highest disclosed GHG emissions, which collectively amount to a market capitalisation of approximately USD 5.8 trillion and emit a total of 28 Gt of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions considering all scopes. While there is double counting in this calculation since, for instance, scope 2 GHG emissions of one company may be the scope 3 GHG emissions of another, the 28 Gt emissions of these 100 companies are against the backdrop of global 36.8 Gt emissions from energy combustion and industrial processes in 2022 (IEA, 2023[6]). Both the regional and sectoral distributions, however, are affected by the higher or lower disclosure rates in different markets and industries. For instance, while 92% of European companies by market capitalisation disclose scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions, only 43% of Chinese companies do so as shown in Figure 2.3.

Companies from Europe (33%) and the United States (29%) represent the largest portion of companies with the highest disclosed GHG emissions (Figure 2.19, Panel B). Extractives and minerals processing sector account for 40% of the companies with the highest disclosed GHG emissions.

Figure 2.19. 100 listed companies with the highest disclosed GHG emissions

Extractives and Minerals: 40% of top 100 GHG emitters

Note: The highest disclosed GHG emissions include scope 1, scope 2, and scope 3 GHG emissions. The shares in this figure are calculated using the number of companies, and not their market capitalisation.

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg. See Annex A for details.

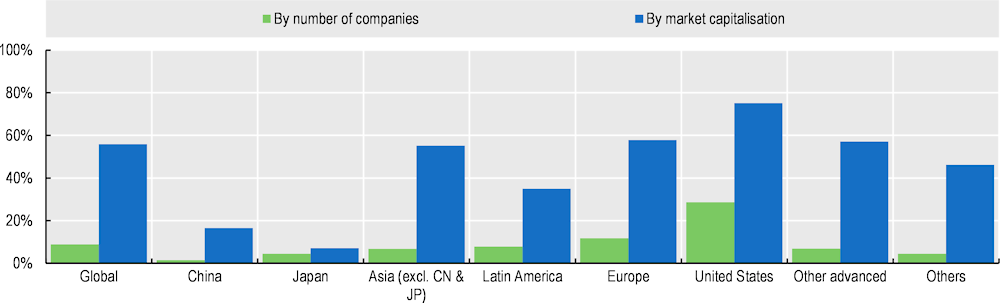

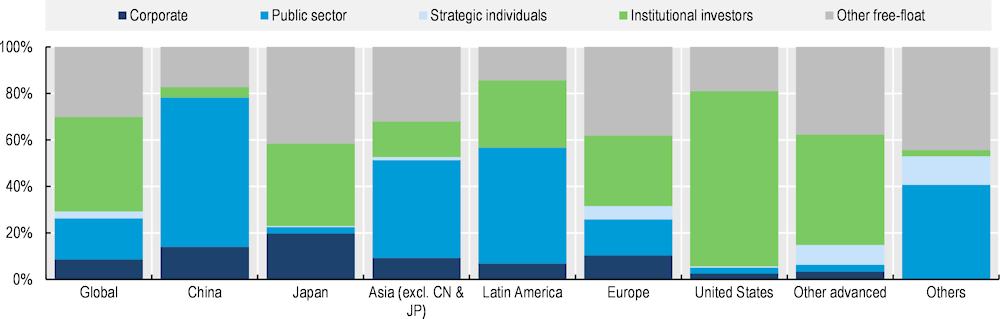

Figure 2.20 shows the ownership distribution for the top 100 high-emitting companies among different categories of owners for the selected regions, using the categories in the report Owners of the World’s Listed Companies (De La Cruz, Medina and Tang, 2019[7]). Globally, institutional investors hold the largest share at 41%. In the United States, institutional investors hold a 75% share, in line with broader trends of institutional ownership in the US equity market. In China, the public sector plays a major role, holding 64% of equity in these high‑emitting companies. Japan demonstrates a more balanced ownership structure with corporate holdings at 20% and institutional investors at 35%. In Latin America, the public sector is important with a 50% share, while Europe shows a more diversified investor base, including corporate and institutional investors with 10% and 30%, respectively.

Figure 2.20. Investor holdings of the 100 high‑emitting companies

Institutional investors hold the highest share of equity in top-emitting listed companies, followed by the public sector

Note: “Other free-float” refers to the holdings by shareholders that do not reach the threshold for mandatory disclosure of their ownership records or retail investors that are not required to do so.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg. See Annex A for details.

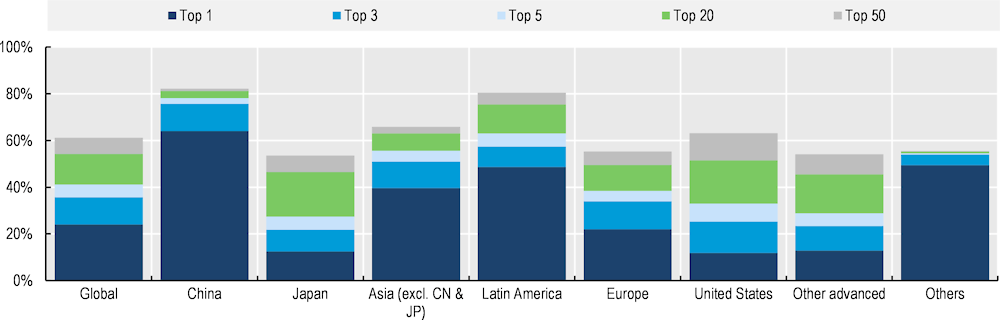

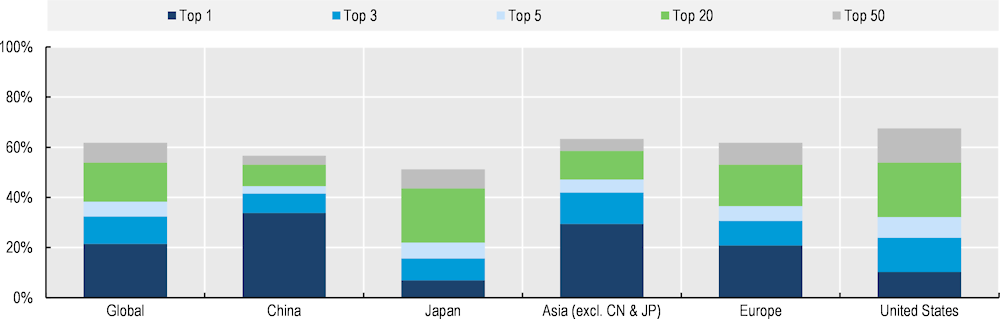

The degree of concentration and control by shareholders at the company level is important when considering investors’ engagement activities and effective change in the strategy of a company (e.g. about its climate‑related goals). Figure 2.21 shows the distribution of ownership concentration among the 100 companies with the highest disclosed GHG emissions. Globally, the largest shareholder in each of these 100 companies owns on average 24% of the shares and the largest 20 shareholders own on average 54% of the shares. This means that in markets such as China and Latin America most (if not all) high‑emitting companies have a well‑defined controlling shareholder and, therefore, any changes in their strategy will most likely depend on the decision of this controlling shareholder. In other markets such as the United States and Japan, while several high‑emitting companies do not seem to have a controlling shareholder (the top 3 shareholders own 25% or less of the shares), the 20 largest shareholders own around 50% of the shares on average, which suggests that these investors may be able to alter the sustainability‑related goals of some high‑emitting companies’ strategies.

Figure 2.21. Ownership concentration at the company level in the 100 high‑emitting companies

The 20 largest shareholders of the 100 high-emitting listed companies would often be able to change their strategy

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg. See Annex A for details.

While the adoption of existing green technologies by high‑emitting companies is essential for the transition to a low‑carbon economy, the development of new technologies will also be necessary to guarantee the transition while maintaining high standards of living. To provide an overview of sustainability and innovation in the corporate landscape, Figure 2.23 shows the 100 listed companies with the lowest disclosed GHG emissions relative to revenues and the highest R&D expenditure or stock of patents per industry. Moreover, to avoid a possible selection bias (i.e. industries that structurally have low emissions and are therefore not as susceptible to transition risks) only industries with emissions above one Gt of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions have been selected. However, the renewable resources and alternative energy industry has been included since its R&D and stock patents aim to reduce, as a rule, mitigation risks (see the Annex A for the complete methodology).

The ranking of companies by their relative GHG emissions in each industry is used as a proxy of whether the companies’ patents and R&D investments may be considered green. It is an imperfect proxy, because a company may currently be a high emitter but plan to become greener in the future, but adopting such a proxy is the best solution in the absence of information on green R&D investment and patents. In the LSEG commercial database, for example, there is information on “environmental R&D costs” for only 267 listed companies globally, representing 3.4% of global market capitalisation, of which 106 are Japanese and account for more than 20% of the country’s market capitalisation (Figure 2.22).

Figure 2.22. Disclosure of environmental R&D costs by listed companies in 2022

Investors lack data on environmental R&D costs, hindering innovation assessment, with Japan as an outlier

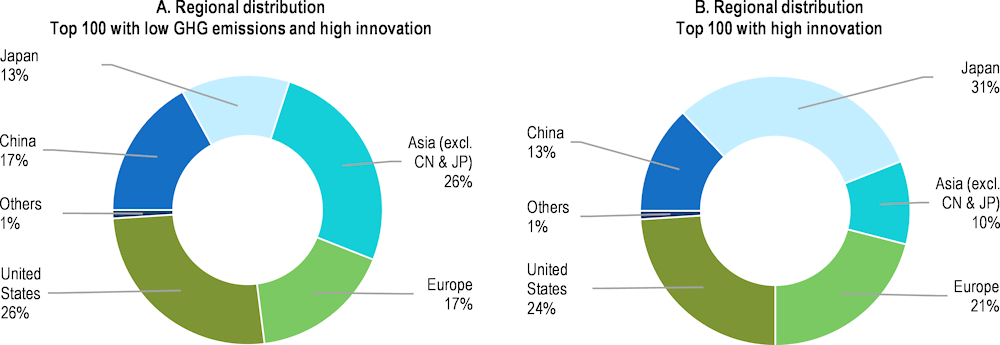

Looking at the regional distribution of the 100 listed companies with low GHG emissions and high innovation, the United States and Asia excl. China and Japan represent the highest portion of companies (26% each), while Japan, China and Europe represent respectively 13%, 17% and 17% (Figure 2.23, Panel A). When comparing this distribution with the top 100 companies with the highest R&D expenditure or stock of patents, China, Europe and the United States show similar shares as for the top 100 companies with low GHG emissions and high innovation. In contrast, companies from Japan have a larger share (31%) of highly‑innovative companies than companies with low relative GHG emissions and high innovation (Figure 2.23, Panel B).

Figure 2.23. The 100 listed companies with low relative GHG emissions and high innovation

Asia leads with over half of top 100 low GHG emission, high innovation listed companies

Note: The shares in this figure are calculated using the number of companies, and not their market capitalisation.

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg. See Annex A for details.

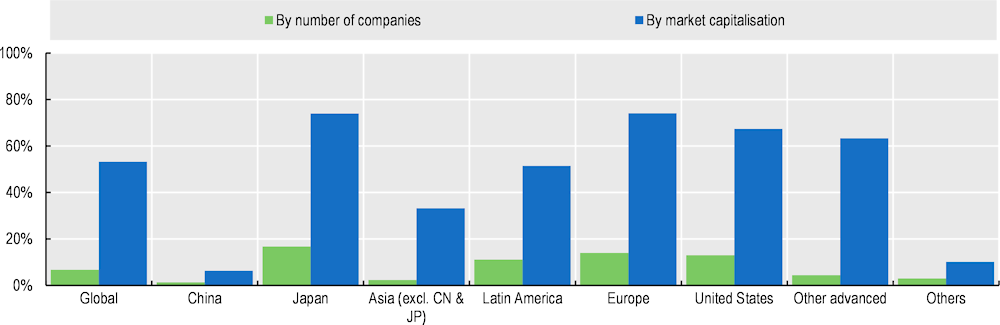

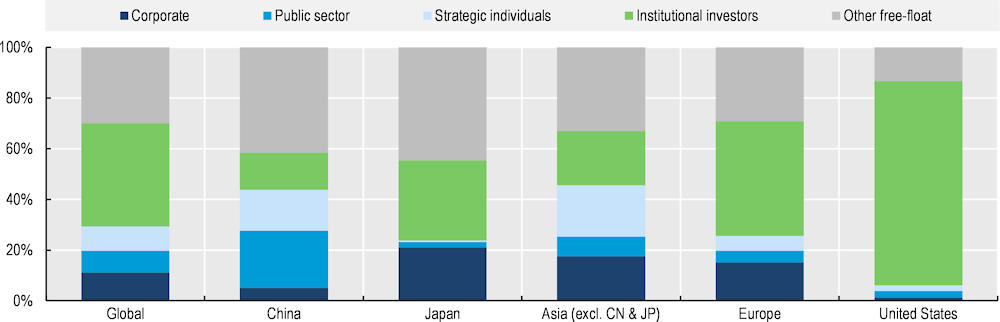

At a global level, institutional investors own 41% of the 100 highly‑innovative and low-emitting companies’ total market capitalisation, which is exactly the same ownership by institutional investors of the 100 high‑emitting companies (Figure 2.24). The United States is characterised by a high concentration of institutional investors, who own 80% of the equity in the 100 highly‑innovative and low-emitting companies. This is in line with the pattern of institutional ownership in US high‑emitting companies of 75% (as seen in Figure 2.20). In contrast, China’s ownership landscape for highly‑innovative and low-emitting companies is quite different than for high-emitting companies, with the public sector making up a smaller portion at 23% and a higher presence of institutional investors and other free‑float investors (15% and 42%, respectively). Japan has a diversified structure with 21% of corporate holdings and 32% from institutional investors among highly‑innovative and low-emitting companies. Europe mirrors this diversification, albeit with institutional investors holding 45% and corporate holdings 15%. Notably, institutional investors have a significantly higher share of ownership of highly‑innovative companies than high‑emitting companies in Europe.

Figure 2.24. Investor holdings of the 100 companies with low emissions and high innovation

Institutional investors hold the largest share of the top 100 low GHG emission, high innovation listed companies

Note: “Other free-float” refers to the holdings by shareholders that do not reach the threshold for mandatory disclosure of their ownership records.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg. See Annex A for details.

Figure 2.25 shows the ownership concentration among the 100 companies with low relative emissions and the highest R&D expenditures or filed patents. In China, the largest single shareholder owns an average of 34%, contrasting with the much lower figure of 7% in Japan and 10% in the United States. Examining the top 20 shareholders, however, concentration rises to more than 50% of the shares on average in all regions except in Japan (44%). The ownership concentration of the highly‑innovative companies is moderately – but not significantly – smaller than the ownership concentration of high‑emitting companies, which suggests greater potential for non‑controlling shareholders to effectively engage with highly‑innovative companies.

Figure 2.25. Ownership concentration at the 100 companies with low emissions and high innovation

Highly innovative listed companies show moderately lower ownership concentration than high emitters

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg. See Annex A for details.

2.2.1. Companies with public benefit objectives

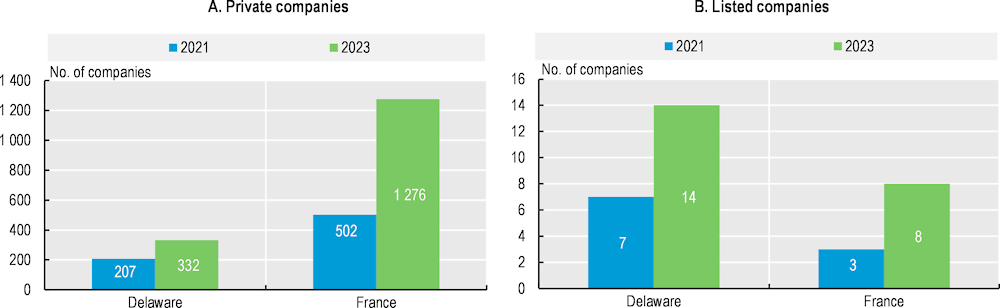

Since 2013, Delaware in the United States has allowed for-profit corporations to register as Public Benefit Corporations (PBCs), which represents a legal obligation for them to balance shareholder interests with the public benefits identified in their certificates of incorporation. PBCs must disclose their status in stock certificates and report biennially on their public benefit objectives, potentially with third‑party verification.

In France, companies can register as a société à mission since 2019 if they meet five key conditions: defining the company’s raison d'être, which are the principles that the company has adopted and for which it intends to allocate resources; specifying social and environmental objectives in their articles of association; forming a monitoring committee; undergoing third-party verification of whether the company fulfilled its non‑financial goals; and registering the société à mission in the Trade and Companies Register.

Between 2021 and 2023, there was a notable increase in the number of both private and listed companies with public benefit objectives in Delaware and France (Figure 2.26). In Delaware, the number of private PBCs grew from 207 in 2021 to 332 in 2023, while the number of listed PBCs doubled from 7 to 14. Similarly, France saw a rise in sociétés à mission with private entities increasing from 502 in 2021 to 1 276 in 2023. The number of publicly listed sociétés à mission also rose from 3 in 2021 (OECD, 2022[8]) to 8 in 2023 (Observatoire des sociétés à mission, 2022[9]).

Figure 2.26. Private and listed companies with public benefit objectives

Delaware and France saw a rise in companies with public benefit objectives, yet market relevance remains limited

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, Observatoire des sociétés à mission, LSEG. See Annex A for details.

2.3. The board of directors

Establishing a board committee responsible for sustainability is not the only way for a company to manage its sustainability risks and a committee, if not well structured, may even be ineffective in doing so. However, the existence of a sustainability board committee may be a proxy for the importance given by boards to sustainability risks. Companies representing more than half of the world’s market capitalisation have established a committee responsible for overseeing the management of sustainability risks and opportunities reporting directly to the board (Figure 2.27). In the United States, 75% of the companies by market capitalisation have a committee responsible for sustainability and in Asia excl. China and Japan, Europe and Other advanced economies, more than 50% have such a committee.

Figure 2.27. Board committees responsible for sustainability in 2022

Over half of companies by market capitalisation have board committees overseeing sustainability risks

The board of directors may consider specifically climate‑related issues when overseeing management, although not necessarily via the establishment of a dedicated board committee. Globally, almost 3 000 companies representing 53% of global market capitalisation indicated their boards of directors oversee climate‑related issues (Figure 2.28). In Japan and Europe, more than 70% of companies by market capitalisation reported a board‑level oversight of climate‑related issues.

Figure 2.28. Self‑reported board-level oversight of climate-related issues in 2022

3 000 listed companies globally have boards overseeing climate issues, but developing economies lag

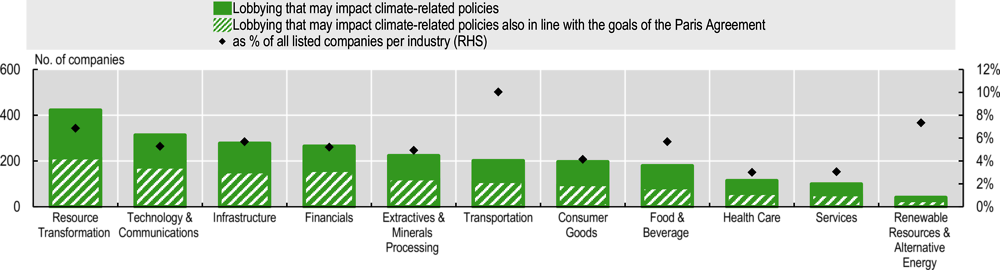

The board of directors might also play a pivotal role in overseeing the lobbying activities conducted and financed by the company that could either directly or indirectly influence climate‑related policies, laws or regulations. Figure 2.29 shows the information on self-declared lobbying activities, and whether these are self‑reported to be aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Among 2 329 companies involved in lobbying specifically on climate‑related policies, 645 companies belong to the two industries with the highest emissions, respectively extractives and mineral processing and resource transformation. On the contrary, only 41 companies belong to the renewable resources and alternative energy industry, but they represent a greater share of the total number of companies per industry.

Figure 2.29. Self‑declared lobbying activities related to climate in 2022

Of 2 329 companies lobbying on climate, 645 are from the two highest emitting industries

To fulfil their key functions in assessing the company’s risk profile and guiding its governance practices, boards can also take into consideration sustainability matters when establishing key executives’ compensation. While companies representing 85% of global market capitalisation have executive compensation policies linked to performance measures, three‑fifths of these include a variable executive remuneration based on sustainability factors (Figure 2.30). Executive compensation is linked to sustainability matters in 80% of the companies by market capitalisation in Europe, followed by Other advanced economies (74%) and the United States (60%). In Asia, executive compensation is linked to sustainability matters, on average, in 20% of the companies by market capitalisation.

Figure 2.30. Executive compensation linked to sustainability matters in 2022

Sustainability-linked executive compensation has become common in large European and US listed companies

2.4. The interests of stakeholders and engagement

To build trust in a long‑term business strategy, companies may establish policies to facilitate shareholder engagement. Globally, 81% of companies by market capitalisation disclose policies on shareholder engagement, including, for instance, how shareholders can question the board or the management or table proposals at shareholder meetings (Figure 2.31). The share of companies that establish policies on shareholder engagement is the highest in the United States (93% of market capitalisation) and in Europe (85%), while relatively lower in Japan (51%) and Latin America (36%).

Figure 2.31. Policies on shareholder engagement in 2022

81% of companies by market capitalisation disclose policies on shareholder engagement

To promote a co‑operation with employees, companies may establish mechanisms for employee participation, such as workers’ councils that consider employee viewpoints in certain key decisions, or employee representation on the board. Companies representing 14% of global market capitalisation have employee representatives on the board of directors (Table 2.1). There are notable differences across regions, ranging from 62% in China, 38% in Europe and 11% in Latin America, to negligible amounts in other regions.

Table 2.1. Employee representation on boards in 2022

|

By number of companies |

By market capitalisation |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Global |

4.53% |

14.05% |

|

China |

26.17% |

62.24% |

|

Latin America |

0.80% |

10.92% |

|

Europe |

10.58% |

37.90% |

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, Bloomberg. See Annex A for details.

Globally, almost 6 000 companies representing 70% of market capitalisation disclose information on whether they engage with their stakeholders and how they involve them in decision‑making (Figure 2.32). In every region, apart from the “Others” category, at least 60% of companies by market capitalisation disclose such information, and in Europe almost 90% do so.

Figure 2.32. Disclosure on stakeholder engagement in 2022

Nearly 6 000 companies disclose stakeholder engagement globally, with small differences across regions

2.5. Sustainable bonds

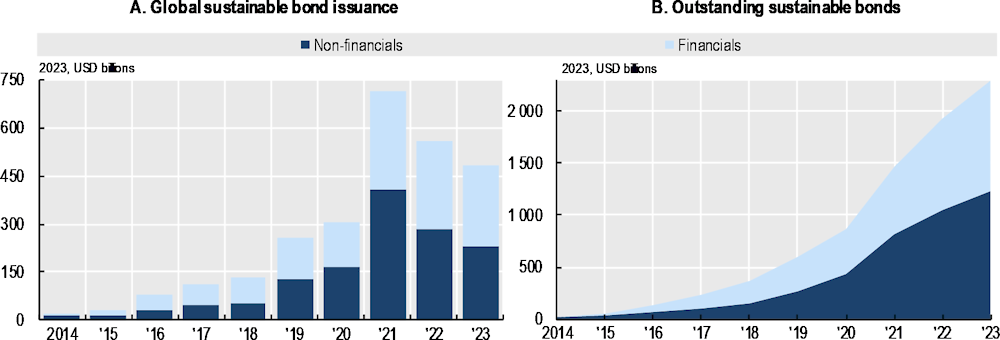

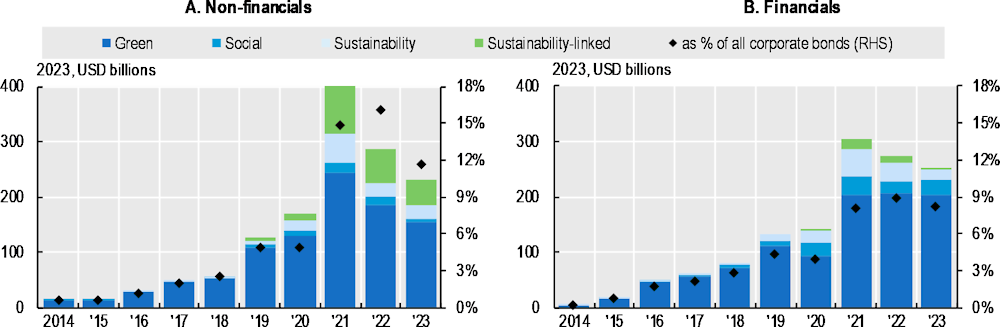

Sustainable bonds fall into two main categories: “Use of Proceeds Bonds” and “Sustainability‑Linked Bonds” (SLBs). The former are bonds where the proceeds are earmarked for financing or refinancing eligible green, social, or sustainable projects. SLBs have variable financing costs based on the issuer meeting specific sustainability targets, but the proceeds do not have to be allocated to sustainable projects. “Use of Proceeds Bonds” specifically include green, social and sustainability bonds (GSS bonds). Green bonds fund environmentally beneficial projects, including specific categories like “blue bonds” and “climate bonds”. Social bonds target projects addressing social issues, while Sustainability Bonds finance a mix of both green and social projects (OECD, 2024[10]).

Over the past five years, corporate sustainable bonds have experienced notable growth as a source of capital market financing. The total amount issued through corporate sustainable bonds was six times larger in 2019‑23 than in 2014‑18. Moreover, in 2021, a record amount of USD 713 billion was issued by corporates, of which 57% was issued by non‑financial companies (Figure 2.33, Panel A). In 2023, corporate sustainable bond issuance decreased by 32% compared to 2021.

In 2023, the outstanding amount of sustainable bonds issued by the corporate sector totalled USD 2.3 trillion. The outstanding amount of sustainable bonds issued by the non‑financial corporate sector accounted for USD 1 230 billion, representing 8% of the outstanding amount of the bonds issued in this sector. Similarly, financial companies’ outstanding amount of corporate bonds totalled USD 1 068 billion, which is 6% of the outstanding amount of all corporate bonds issued by financial companies (Figure 2.33, Panel B).

Figure 2.33. Global sustainable bonds issuance and outstanding amount

Corporate sustainable bond issuances surged 6-fold from 2014-18 to 2019-2023

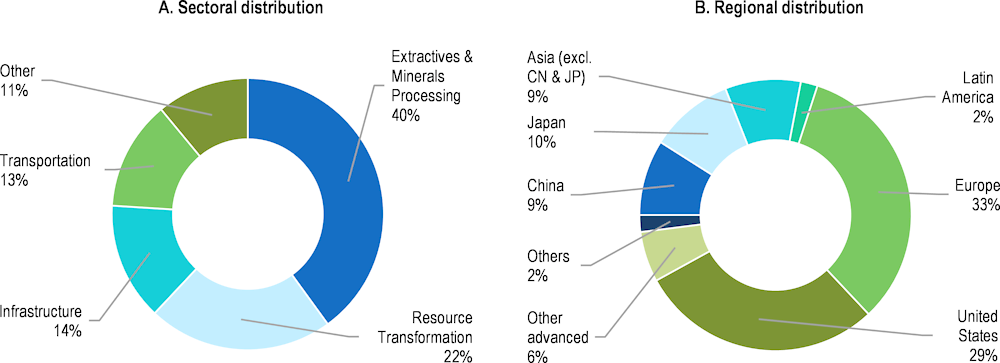

Europe has been the most active region in the sustainable bonds market in the corporate sector. From 2014 to 2023, 45% of the global amount issued through corporate non-financial sustainable bonds was raised by European companies. China and the United States follow with 17% and 14%, respectively (Figure 2.34). Similarly, the issuance of sustainable bonds by financial corporates has been more important in Europe (54%), followed by China (15%), Asia excl. China and Japan (10%) and the United States (7%).

Figure 2.34. Global sustainable bond issuance by region, 2014-23

Europe dominates the issuance of corporate sustainable bonds, followed by China

In 2014, sustainable bonds accounted for only 0.6% of the total amount issued by all non‑financial companies. In 2023 this ratio reached 11.7%, after reaching 16% in 2022 (Figure 2.35, Panel A). This rising trend has also been visible for corporate bonds issued by financial companies, whose equivalent ratio surged from 0.2% in 2014 to 8.1% in 2023. In 2023, every category experienced a drop in issuance except for social bonds issued by financial companies, which presented a 23% increase from the year before (Figure 2.35, Panel B). Moreover, despite a decrease of 27% in SLBs issued by non‑financial companies in 2023 in comparison to the previous year, the share of this type of bond still accounted for 20% of the amount issued by non‑financials in 2023.

Figure 2.35. GSS bonds and SLBs issuance by corporates

Sustainability-linked bonds accounted for 20% of the amount issued by non-financial companies in 2023

Note: The black dots correspond to the share of sustainable corporate bonds over all corporate bonds.

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG. See Annex A for details.

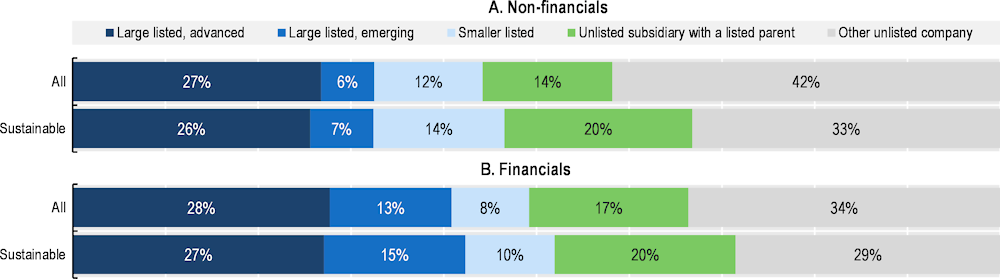

In 2022‑23, unlisted companies (i.e. companies that do not list their equity) issued more than half of the sustainable bonds in both the non‑financial and financial corporate sectors, following the same pattern in the issuance of conventional bonds. In the non-financial corporate sector, unlisted companies issued 53% of all sustainable corporate bonds, followed by large, listed companies that issued 26% of the amount and smaller listed companies with 14% (Figure 2.36, Panel A). Similarly, unlisted financial companies issued 48% of the sustainable corporate bonds, and 27% was issued by large companies (Figure 2.36, Panel B). Interestingly, sustainable bonds have been issued to a larger extent by unlisted subsidiaries with a listed parent than other unlisted companies when compared to the issuance of all corporate bonds. For instance, while 14% of the amount of non‑financial corporate bonds was issued by an unlisted subsidiary with a listed parent, 20% of the amount issued through non‑financial sustainable corporate bonds was issued by the same type of issuer.

Figure 2.36. Corporate issuance by listed and unlisted issuers in 2022-23

Unlisted companies issued half of the sustainable bonds in the corporate sector in recent years

Note: The inclusion of a company in the MSCI World Index or the MSCI Emerging Markets Index is considered a proxy for a listed company being large. Unlisted companies were classified as either a subsidiary with a listed parent company or “other unlisted companies”.

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, MSCI. See Annex A for details.

2.5.1. Sustainable and climate investment funds

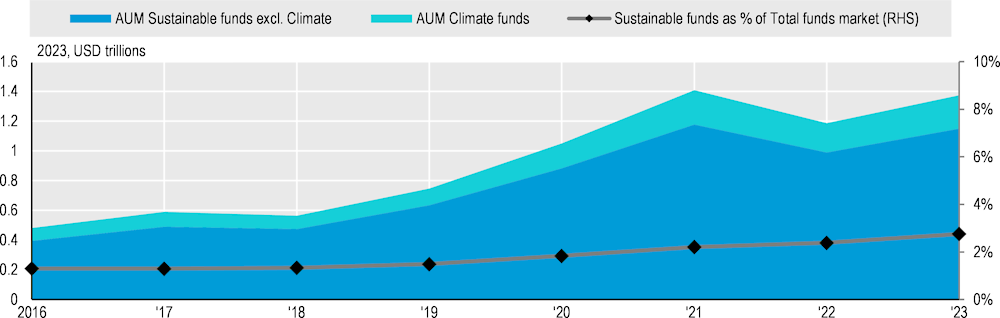

Since 2016, investment funds that label themselves as sustainable or climate funds – by including “ESG”, “sustainable”, “Paris alignment”, “climate transition” or similar terms in their labelling – have received increasing net inflows. In 2016, assets under management (AUM) of these funds totalled USD 481 billion against USD 1 373 billion in 2023 (Figure 2.37). After a slight decline in 2022, assets under the management of all sustainable funds represented 2.76% of the AUM of the entire funds market, while climate funds averaged USD 151 million over the 2016‑23 period. With respect specifically to climate funds, their AUM were almost three times larger in 2023 with USD 224 billion when compared to 2016 (USD 85 billion).

Figure 2.37. Assets under management for climate and sustainable funds vs traditional funds

Sustainable funds, despite a long-term rise, make up only 2.76% of global AUM

Note: Funds retrieved from Morningstar Direct classified as ETF and open-ended funds. Sustainable and climate funds have been selected based on the labelling, which included some keywords like “Climate”, “ESG”, “Sustainable”, “Paris alignment” and “Climate transition”, including the translations in other languages. Climate funds include all the funds that specifically refer to “climate change”, “Paris alignment” and “climate transition”. Funds without any asset value are excluded.

Source: Morningstar Direct, OECD calculations. See Annex A for details.