This chapter starts by discussing the synergies between information and communication technology (ICT) procurement and digital government policies and how they can be leveraged for the digital transformation of the public sector. It then analyses the digital government policies of Chile, Colombia and Mexico, their regulatory frameworks and institutional setup, as well as good practices relative to pre-screening the procurement of ICT, including computers, and other digital investments.

Good Practices for Procuring Computers and Laptops in Latin America

1. Supporting public service delivery and digital transformation through ICT procurement

Abstract

The synergies between ICT procurement and digital policies

In OECD countries, public procurement has become critical for delivering quality public services. On average, it represents about 13% of gross domestic product (GDP) and close to 30% of general government expenditures in OECD countries. Table 1.1 illustrates the importance of public procurement in Chile, Colombia and Mexico.

Table 1.1. Public procurement as a percentage of GDP and general government expenditures in Chile, Colombia and Mexico, 2021

|

Chile |

Colombia |

Mexico |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Public procurement as a percentage of GDP |

4.7 |

10.5 |

4.5 |

|

Public procurement as a percentage of general government expenditures |

14.9 |

21.6 |

15.5 |

Source: OECD (2023[1]), Government at a Glance 2023 Database, https://www.oecd.org/publication/government-at-a-glance/2023/ (accessed on 10 November 2023); information provided by ChileCompra.

The volume of resources spent in public procurement leads to risks related to inefficiencies, such as those stemming from insufficient competition and failure to advance vendor neutrality, but also to opportunities to advance complementary policy objectives such as promoting small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and facilitating the digital transformation of the public sector. Indeed, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (2014[2]) highlights the role of an information and communication technology (ICT) procurement environment and strategy in supporting digitalisation and modernisation of the public sector. According to this Recommendation, such a framework should include: i) ICT procurement rules that are compatible with current trends in technology; ii) fostering the development of shared ICT services and resources; and iii) strengthened capacities to improve ICT procurement (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies

The Council

IV. Recommends that, in implementing the digital government strategies, governments should:

11. Procure digital technologies based on assessment of existing assets, including digital skills, job profiles, technologies, contracts, inter-agency agreements to increase efficiency, support innovation, and best sustain objectives stated in the overall public sector modernisation agenda. Procurement and contracting rules should be updated, as appropriate, to make them compatible with modern ways of developing and deploying digital technology.

Source: OECD (2014[2]), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, https://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/recommendation-on-digital-government-strategies.htm (accessed on 10 November 2023).

At the same time, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement (2015[3]) calls adherents to advance access and efficiency (Box 1.2). This Recommendation builds on good practices from OECD countries and provides a comprehensive framework for designing a public procurement system that supports digital transformation.

Box 1.2. OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement

Access

IV. RECOMMENDS that Adherents facilitate access to procurement opportunities for potential competitors of all sizes. To this end, Adherents should:

i) Have in place coherent and stable institutional, legal and regulatory frameworks, which are essential to increase participation in doing business with the public sector and are key starting points to assure sustainable and efficient public procurement systems. These frameworks should:

1) be as clear and simple as possible;

2) avoid including requirements which duplicate or conflict with other legislation or regulation; and

3) treat bidders, including foreign suppliers, in a fair, transparent and equitable manner, taking into account Adherents’ international commitments.

Efficiency

VII. RECOMMENDS that Adherents develop processes to drive efficiency throughout the public procurement cycle in satisfying the needs of the government and its citizens. To this end, Adherents should:

i) Streamline the public procurement system and its institutional frameworks. Adherents should evaluate existing processes and institutions to identify functional overlap, inefficient silos and other causes of waste. Where possible, a more service-oriented public procurement system should then be built around efficient and effective procurement processes and workflows to reduce administrative red tape and costs, for example through shared services.

Source: OECD (2015[3]), Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/ (accessed on 10 November 2023).

In line with the OECD recommendations, countries can leverage public procurement to advance the digital transformation of their governments. In doing so, they need to be aware of specific challenges discussed in this report, such as considering market capacities, planning and carrying out the pre‑tendering stage, avoiding vendor lock-in, diversifying procurement mechanisms and tools to maximise competition and value for money and responding to user needs.

In responding to these challenges, OECD countries have advanced recent initiatives. In Australia, for example, an ICT Procurement Taskforce was set up in 2016 to identify obstacles and opportunities to streamline ICT procurement, as well as make it easier for SMEs to compete for ICT public contracts. The resulting outcome was the introduction of a new ICT procurement framework. Likewise, The OECD Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (also known as E-Leaders), through one of its thematic groups and in partnership with the United Kingdom (UK) Government Digital Service put together a manual of good practices for ICT procurement reform. In consequence, the working group developed the ICT Commissioning Playbook, advancing the following principles:

Opening up data throughout the procurement and contracting lifecycle.

Encouraging more modular and agile approaches to contracting.

Procurement transparency to help tackle corruption and improve value for money.

Stimulating and accessing a more diverse digital and technology supply base.

Encouraging more flexible, digital, agile and transparent interactions focused on joint delivery.

Sharing and reusing platforms and components, and better practices for delivering successful programmes.

The ICT Commissioning Playbook addresses the full procurement lifecycle and provides practical advice and good practices for the pre-tendering, tendering and contract management stages. The playbook was presented in 2018 and has been continuously revised based on its use in OECD countries and others (OECD, 2022[4]).

Box 1.3. The ICT Commissioning Playbook

The ICT Commissioning Playbook discusses ICT procurement reform and its role in the digital transformation of the public sector. It illustrates how traditional procurement can evolve towards agile procurement. The playbook addresses the main issues faced by governments and explores what works and what does not, sharing real-life cases.

The playbook provides a set of actionable guidelines (plays) that countries can adopt to implement agile approaches for ICT procurement. The 11 plays include the following:

Setting the context.

Starting by understanding user needs.

Embracing openness and transparency.

Working as a multidisciplinary team.

Building collaborative relationships.

Sharing and reusing solutions that were developed for other parts of the government.

Public procurement for public good.

The plays describe how to overcome common issues, supported by case studies to illustrate real challenges and achievements. The playbook is aimed at public procurement professionals and relies on the experiences of the United Kingdom, with contributions from Australia, Canada, Chile, Finland, Mexico, New Zealand, Portugal, the United States and Uruguay.

Source: OECD (2022[4]), Towards Agile ICT Procurement in the Slovak Republic: Good Practices and Recommendations, https://doi.org/10.1787/b0a5d50f-en (accessed on 6 September 2023).

Despite the evident synergies between public procurement and digital government policies, Latin American countries are not alone in facing the challenge of developing ICT procurement policies. The 2019 OECD Digital Government Index shows that 67% of OECD countries had developed formal guidelines on ICT procurement, while only 12% reported having a dedicated ICT procurement strategy for the public sector at the central level (OECD, 2020[5]). Moreover, 64% of OECD countries had integrated strategic planning of ICT procurement into a whole-of-government procurement strategy, 67% had adopted a standardised model for ICT project procurement but only half made it mandatory (OECD, 2020[5]). This is illustrative of the opportunities to fully leverage the synergies in favour of seamless public service delivery.

This chapter will review the digital government policies of Chile, Colombia and Mexico and how they interact with public procurement policies and strategies. Even though the report focuses on the procurement of computers (i.e. desktop computers [PCs], laptops, tablets), its findings could also provide useful lessons for the Latin American countries’ wider ICT procurement strategies.

Chile

Chile’s modernisation and digital government policy is based on a set of institutions and regulations. The Permanent Advisory Council for the Modernisation of the State is responsible for “advising the President of the Republic on the analysis and evaluation of the policies, plans and programmes that make up the State modernisation agenda; formulating recommendations on such matters; submitting for his consideration proposals for structural or institutional reform to be carried out as legislative initiatives or within the powers conferred on him by the legal system in matters of internal organisation; and responding to the consultations formulated by this authority”.

The Executive Committee for the Modernisation of the State is composed of the Ministry of Finance, through the Secretariat for Modernisation, the Budget Directorate (Dirección de Presupuestos, DIPRES), the National Directorate of the Civil Service and the Government Laboratory of Chile as well as the Ministry of the Presidency (Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia, SEGPRES), through the Digital Government Division (División de Gobierno Digital, DGD) and the Inter-ministerial Coordination Division, responsible for co-ordinating actions around the implementation of the modernisation and digital government policy.1

On the other hand, Law No. 18.993, which creates SEGPRES, includes the DGD within the organisation of the aforementioned Secretariat of State, which is responsible for proposing the digital government strategy to the minister and co-ordinating its implementation, ensuring that a whole-of-government approach is maintained.

The DGD is responsible for co-ordinating, advising and supporting the strategic use of digital technologies, data and public information to improve the management of public agencies and the delivery of services and acting as the co-ordinating entity for the implementation of Law No. 21.180, as amended by Law No. 21.464, which establishes the digital transformation of the state. The aim is for the complete cycle of administrative procedures of all public agencies, subject to Law No. 19.880 – which establishes the bases of administrative procedures governing the acts of state public agencies – to be carried out in electronic format.

In accordance with the provisions of Law No. 18.993, specifically relative to advice and support for the strategic use of digital technologies, data and public information to improve the management of public agencies and the delivery of services, the Digital Government Division, within the framework of the modernisation agenda, is in the process of designing a technology procurement policy, which is in the diagnostic stage and in respect of which the following route has been drawn up:

Setup of an inter-institutional roundtable on technology procurement (March 2023).

Diagnosis and analysis of new technology procurement mechanisms (August 2023).

Proposal for new technology procurement mechanisms (December 2023).

Law on Digital Transformation

Law No. 21.180, enacted on 11 November 2019, introduces changes to the fundamentals of administrative processes with the purpose of promoting their transition to digital in order to facilitate the provision of more accessible, simple and agile services for citizens.

In line with this regulation, every administrative process must be carried out through the electronic channels established by law, except in the cases specifically recognised as exceptions. The advantages of implementing this law include improving accessibility for people, fostering effective co-operation between government bodies, saving time and making the most of the various technological tools currently available, with the aim of facilitating a more agile, efficient and timely administration, where people’s needs are the main priority.

The Law on Digital Transformation of the State applies to a variety of institutions, including ministries, armed and security forces, public services, presidential delegations, regional governments and municipalities, among others. In order to facilitate implementation, these institutions have been segmented into three categories: A, B and C. Depending on the category to which the entity belongs, specific deadlines and procedures are established for implementation.

It is relevant to note that in June 2022, considering the internal processes necessary in the institutions to prepare for the implementation of their digital transformation process, the original implementation sequence related to this regulation was modified. A preparation phase was introduced and the stages and deadlines for each group of institutions were restructured. In this way, the management bodies, both at the central and local levels, aim to have the right conditions in place to fully implement the law by 31 December 2027.

This new gradual approach started in 2022 with a preparatory phase, in which administration bodies, including ministries, public services, the Comptroller General of the Republic, the armed forces, order and security forces, regional and provincial presidential delegations, regional governments, municipalities and universities subject to the law, must identify and map their administrative procedures. This will allow for the collection of the basic information necessary to facilitate the implementation of the subsequent phases of the law.

Following this readiness phase, the path towards full implementation of the standard in 2027 will include the following six stages:

1. Official communications: Official communications between bodies will be recorded on a designated platform.

2. Initiation of administrative procedures in digital form: Each body shall establish electronic platforms or forms for individuals to submit requests or documents to the state digitally.

3. Document management, workflow systems and electronic files: Each administrative procedure shall include electronic files available to interested parties through electronic platforms to improve the transparency of the processes.

4. Digitisation of paper documents: If a person is unable to use electronic means, the corresponding body shall digitise and add their requests to the electronic file.

5. Principle of interoperability: Bodies shall comply with the principle of interoperability, ensuring that electronic media can interact and operate with each other within the state administration through open standards for secure and efficient interconnection.

6. Electronic notifications: Notifications to natural or legal persons will be made electronically, according to the information contained in a single register managed by the Civil Registry Service.

In this context, the digital transformation co-ordinators have played a key role in advancing this process in each public entity. Their function is to facilitate communication and co-ordination with the different areas involved in the organisation, as well as enable a comprehensive approach to formulating and monitoring the institutional digital transformation plans.

These co-ordinators also act as the official liaisons with the DGD on matters related to digital transformation. Their objective is to maintain a continuous connection and monitor progress in the fulfilment of all implementation stages of the Act. They are also responsible for reporting on their institutions’ progress and communicating internally on achievements, timelines and training opportunities related to the Act.

It is important to note that because the digital transformation co-ordinator is not always the same official as the chief information officer (CIO) or the chief technology officer (CTO) of the organisation, the evaluation and supervision of technology projects are not always under their responsibility.

EvalTIC

General elements

EvalTIC is a system designed and implemented by DIPRES in response to the lack of standardisation detected in the requests received from public sector agencies. It is a joint effort between DIPRES, the DGD and the Ministry of Finance’s Secretariat for Modernisation. EvalTIC allows institutional CIOs, procurement officials and other strategic decision makers to register and justify their technology needs and projects through an online platform.

This tool has improved the evaluation and planning capabilities of agencies and moved them to adopt practices to ensure that their needs meet EvalTIC standards and are fit for initial approval, which eventually allows for a more optimal route to get the required budget.

Since 2002, EvalTIC is backed by the yearly Budget Law and allows for the analysis of technology procurement projects with the objective of providing information to DIPRES to define budgets for each agency. The system is also considering providing feedback to each agency and evaluator.

EvalTIC has been in operation since 2018 and has evolved through joint work between DIPRES, the Ministry of Finance and the DGD, which elaborated a complementary process to the usual budget formulation for the design and evaluation of technology projects, ending with a technical recommendation, to those responsible for budget clearance, regarding approval or rejection.

Based on an initial inventory of its technological assets through EvalTIC, each public agency must register its projects annually, considering a set of general principles that make it possible to standardise project elements and facilitate analysis.

Submission of projects to EvalTIC

In order to submit projects through EvalTIC, each purchasing agency establishes a team responsible for the formulation and submission of ICT projects, preferably composed of the Head of Administration and Finance, the Head of Information and Communication Technologies and the agency’s digital transformation co-ordinator. The purpose of this structure is to integrate the institution’s strategic guidelines, the digital government guidelines and the budgetary criteria provided by DIPRES.

This team co-ordinates the work to ensure that the project design and architecture are aligned with current international ICT standards and protocols, have well-defined components and deliverables and respect a maximum implementation period of one budget year, with some exceptions.

Furthermore, in addition to defining a set of general technical criteria for each project, the formulation must also comply with criteria specifically aimed at optimising projects, compliance with DGD and ChileCompra guidelines, and implementation of the Presidential Instruction on Digital Transformation and the Digital Transformation Law, which requires institutions to interoperate, all with the aim of ensuring that projects are geared towards achieving efficiency in the state and massifying the use of standards and best practices in information technology (IT).

In the case of computer equipment purchases, DIPRES has indicated that the 36- or 48-month lease versus purchase modality should always be evaluated, so this comparison has to be included. In addition, it has established that the function/task to which the equipment or licence will be assigned must be clearly defined and all the software that will be installed must be considered in order to evaluate the final price and compare it with the leasing alternative (each operating system licence, antivirus, office automation, etc., if included in the price, must be specified).

A platform for project submission

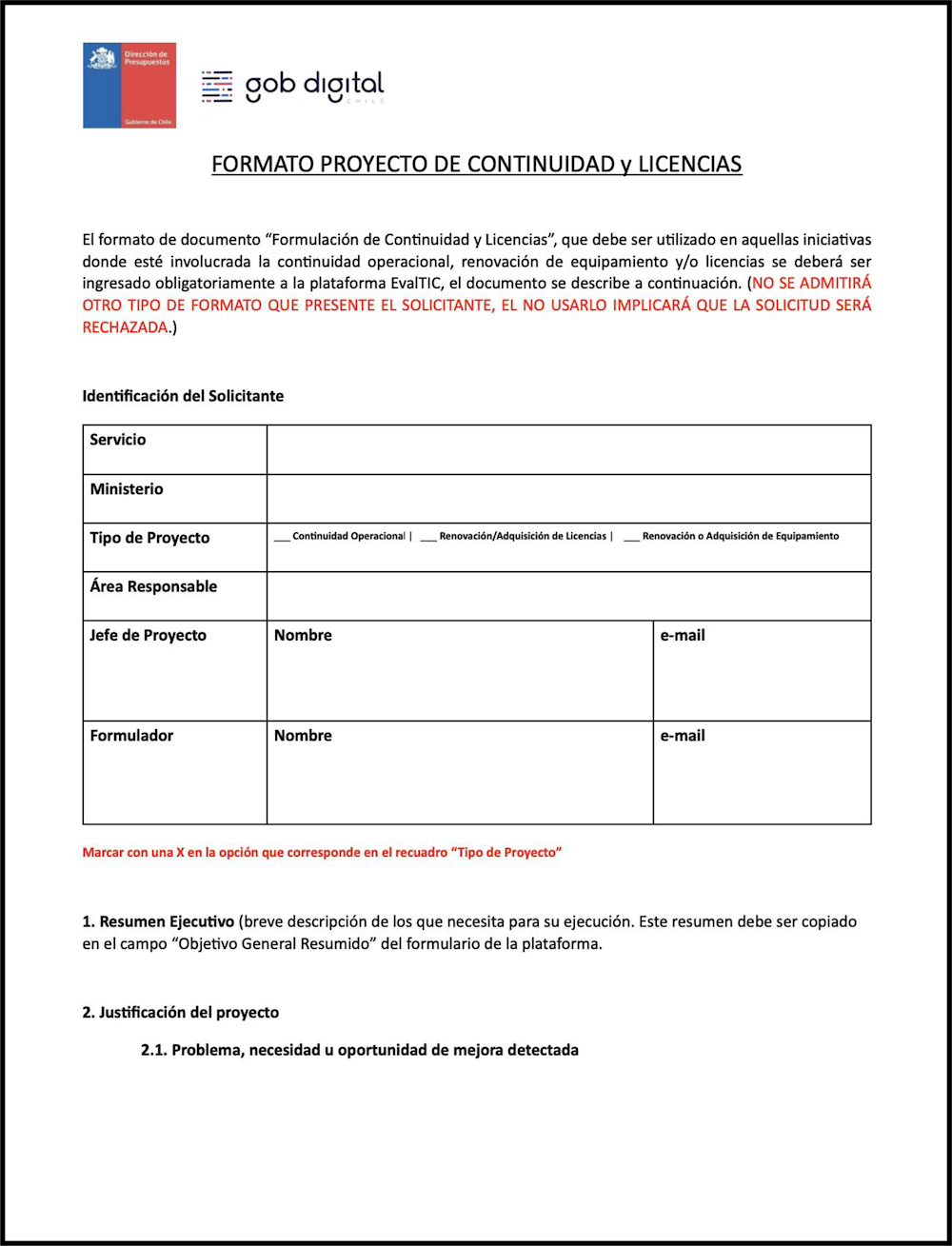

Three different forms are used for the formulation of ICT projects, prepared according to whether they are: i) new projects, which are not related to the operational continuity of each agency; ii) operational continuity and licence renewal projects, which should include all of those involving the renewal of equipment and licences; or iii) carry-over projects from previous years, which correspond to those related to the continuity of projects already submitted and approved.

The basic steps that users must follow to start uploading ICT projects to the EvalTIC platform are the following:

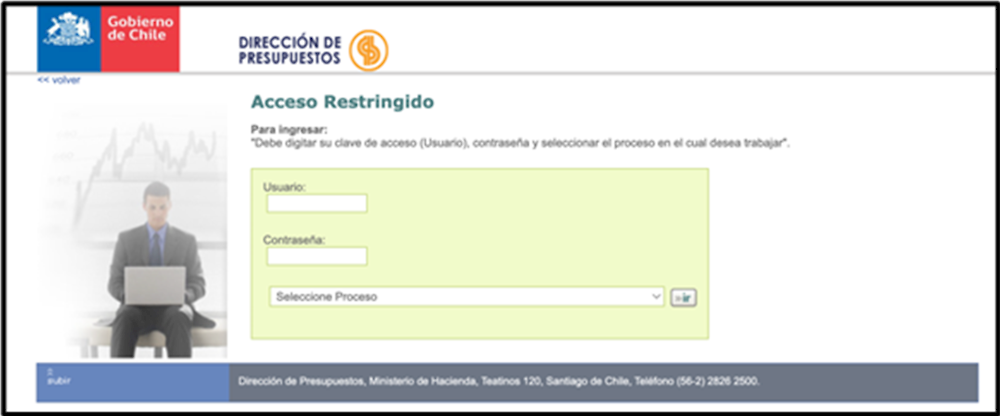

Going to the DIPRES website (https://dipres.gob.cl) and selecting the restricted access link presented in the padlock in the upper right corner of the screen (Figure 1.1).

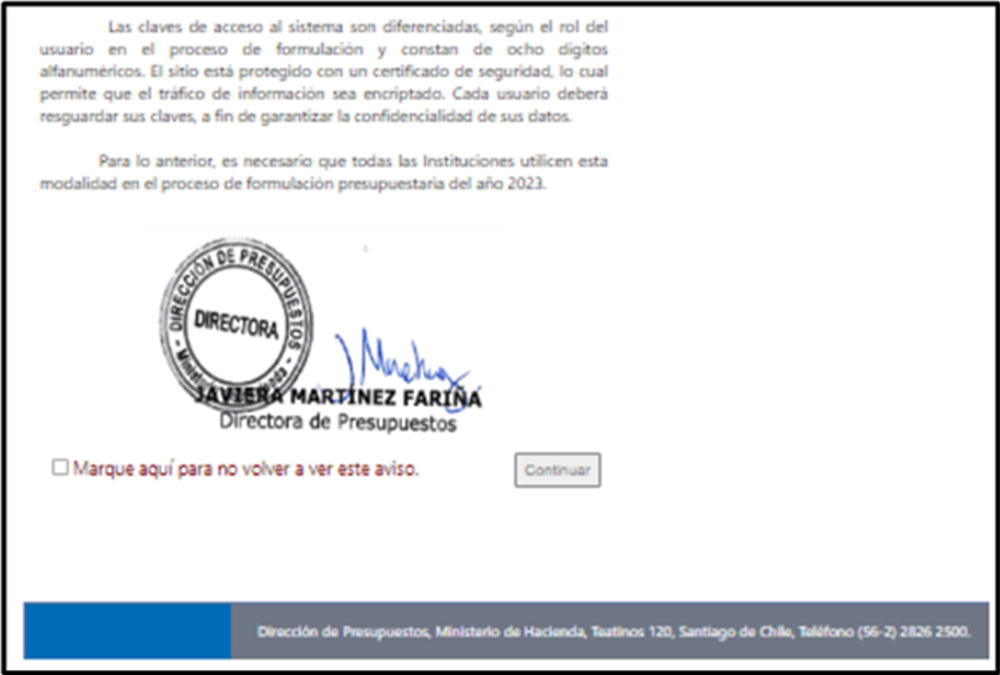

Entering username and password on the page, selecting the process in the dropdown menu, then clicking on the Go button (Figure 1.2).

Reviewing the information about the process displayed on the screen, then clicking on the Continue button (Figure 1.3).

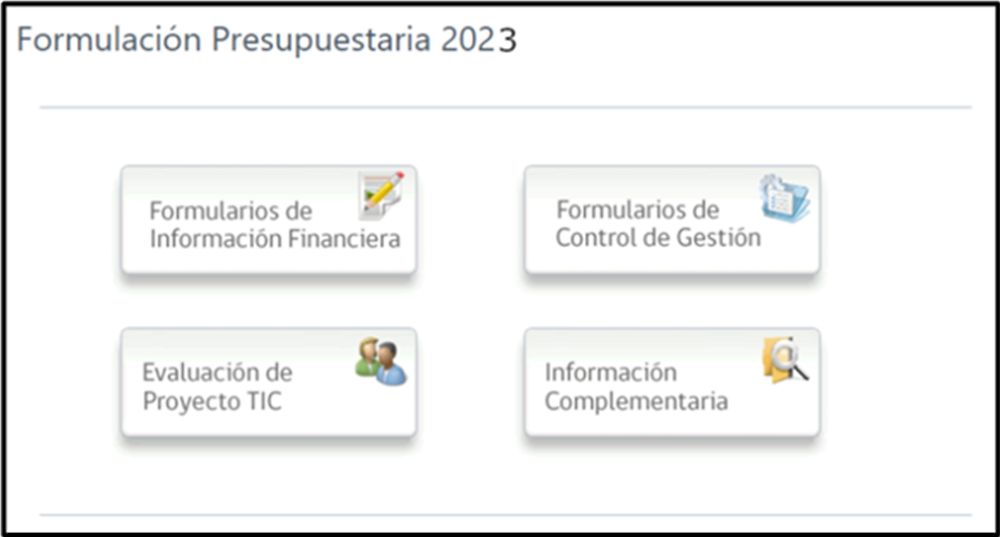

Clicking on the ICT Project Evaluation button (Figure 1.4).

Creating a new application, entering the requested data and uploading the form called “Project form” with all of the required details, as well as any other document/annex considered relevant for a better understanding of the submitted project.

Figure 1.1. DIPRES website

Figure 1.2. Identification page

Figure 1.3. Page to review information about the EvalTIC process

Figure 1.4. Budget elaboration page

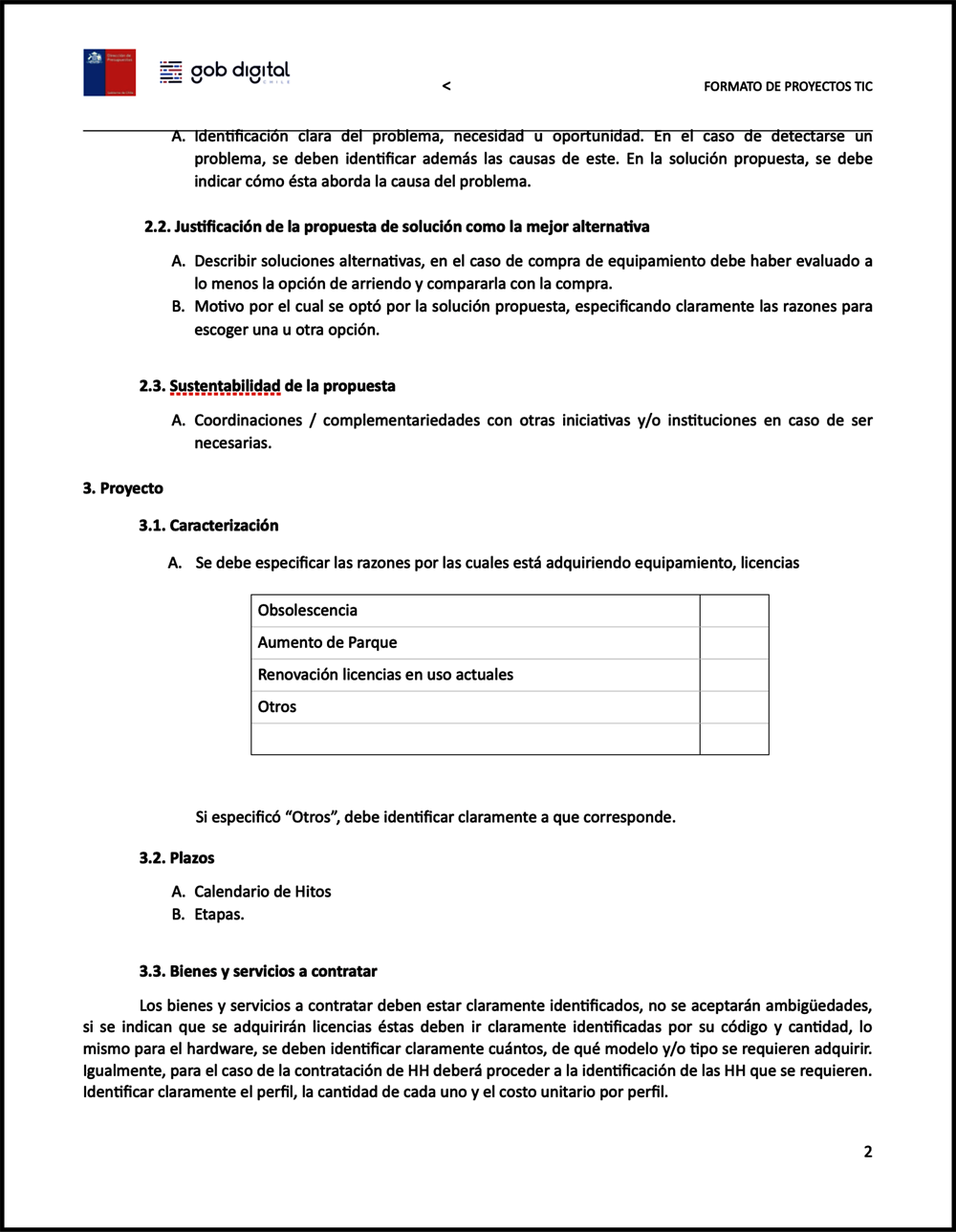

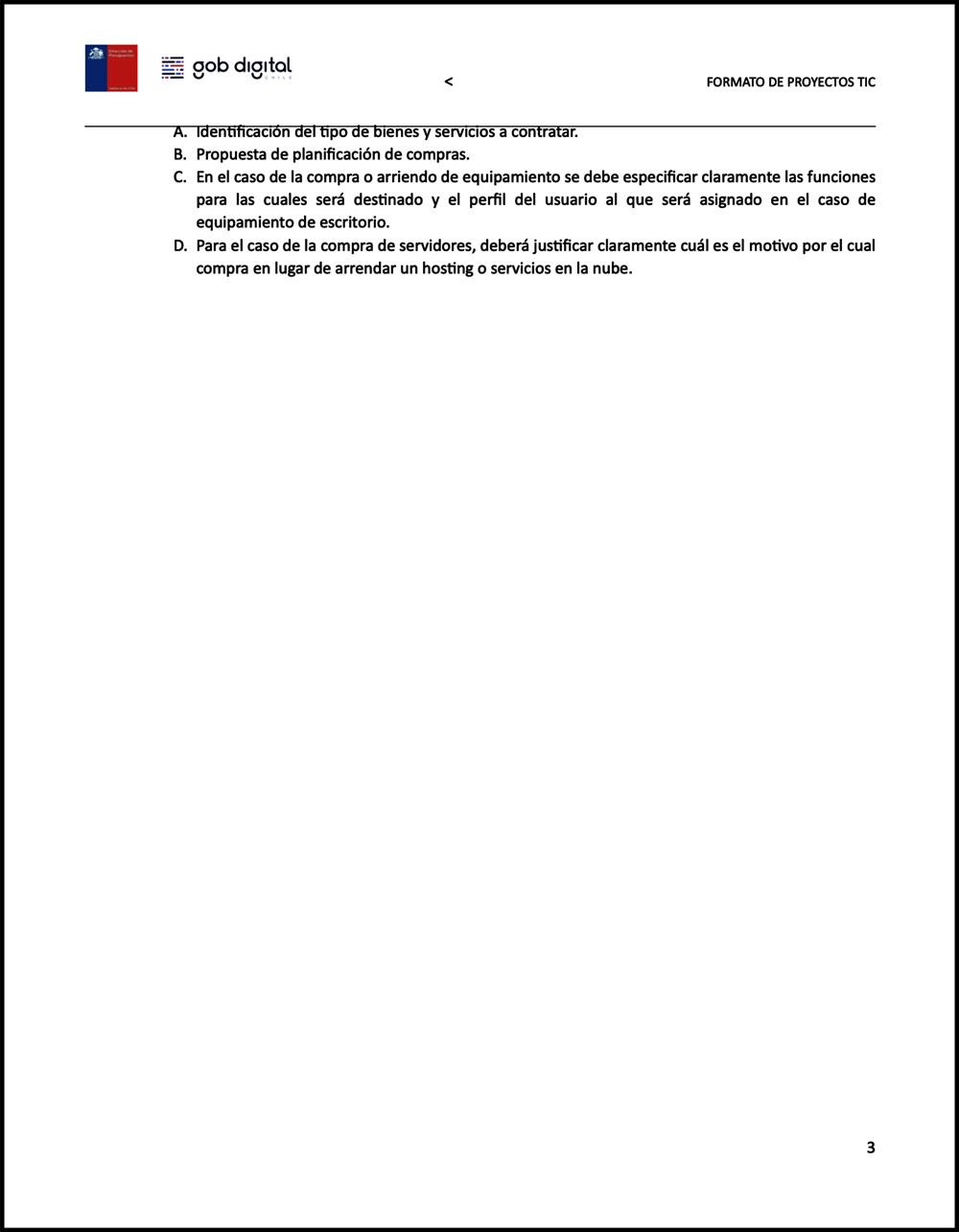

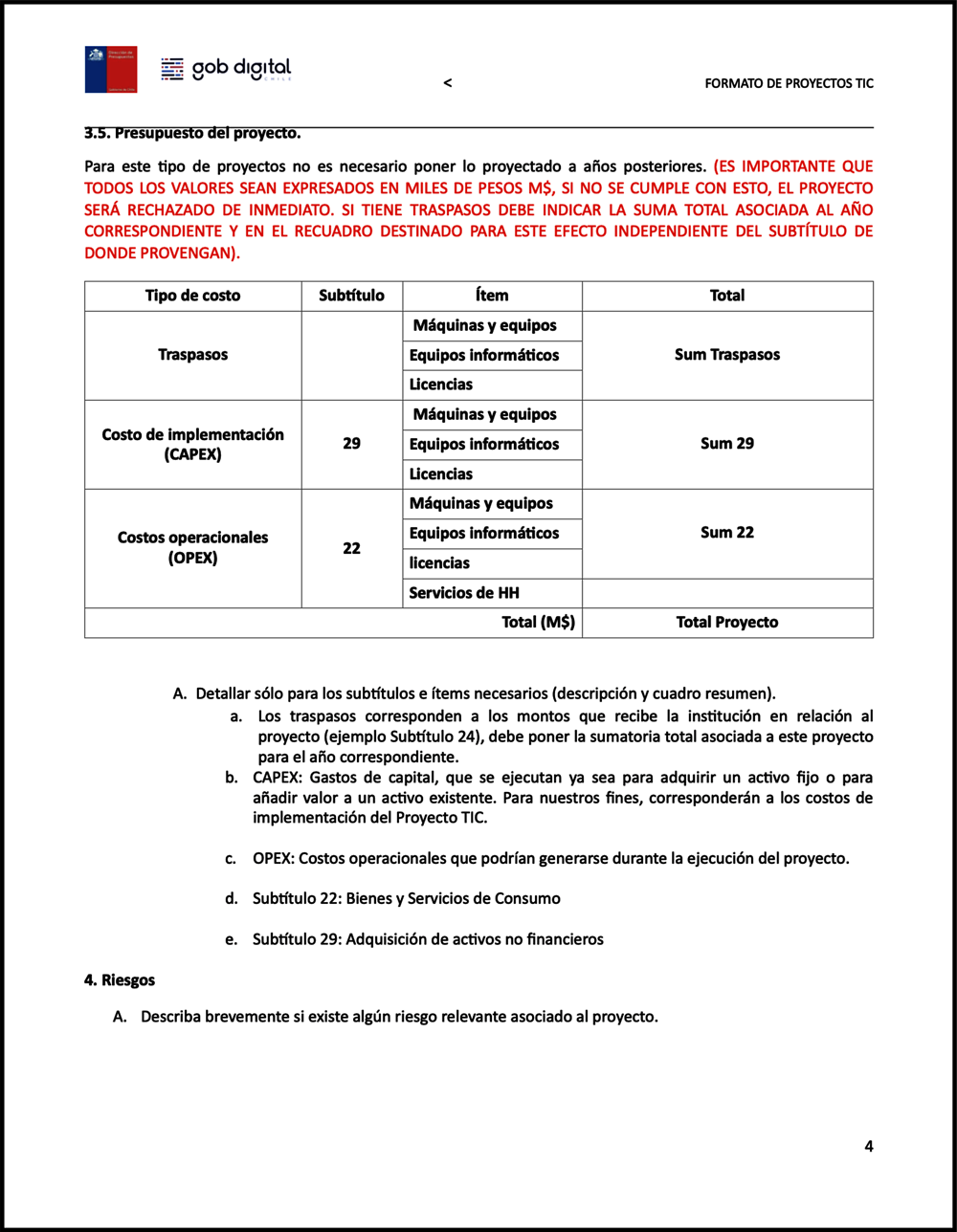

Project formulation templates

There are three official project forms, one for each type of project, which are: i) new projects; ii) business continuity and equipment or licence renewal projects; and iii) continuation or carry-over projects. The form for business continuity and licence renewal projects, including all projects on the renewal of equipment and licences, is illustrated in Figure 1.5 -Figure 1.8. It requests information about the official submitting the project, its justification (i.e. problem to be addressed and suggested solution), characteristics, timeline, goods and services to procure, budget and risks.

Figure 1.5. Template for business continuity and equipment or licence renewal projects, Part I

Source: Information provided by DIPRES.

Figure 1.6. Template for business continuity and equipment or licence renewal projects, Part II

Source: Information provided by DIPRES.

Figure 1.7. Template for business continuity and equipment or licence renewal projects, Part III

Source: Information provided by DIPRES.

Figure 1.8. Template for business continuity and equipment or licence renewal projects, Part IV

Source: Information provided by DIPRES.

Colombia

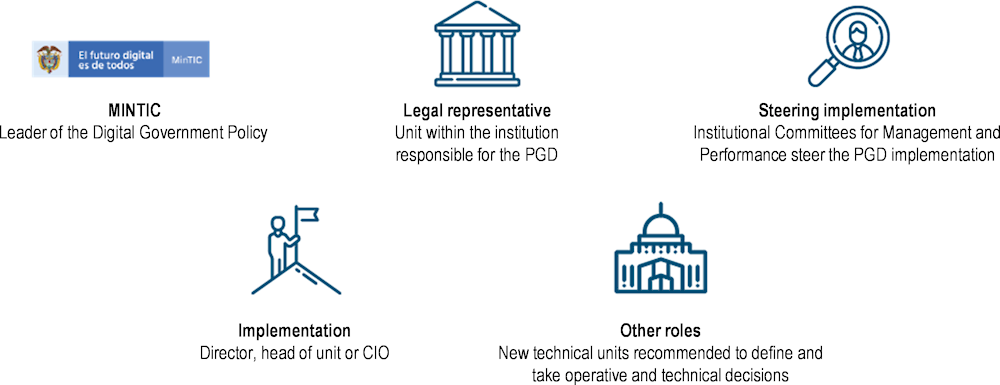

The Digital Government Policy (Política de Gobierno Digital, PGD) is the national government policy aiming at the digital transformation of the public sector and the strengthening of the citizen-state relationship by improving service delivery and building trust in public institutions. The Office of the Senior Counsellor for Digital Transformation (Alta Consejería para la Transformación Digital) and the Ministry for ICT (MinTIC) produce the strategic guidelines for the PGD.

The Digital Government Policy

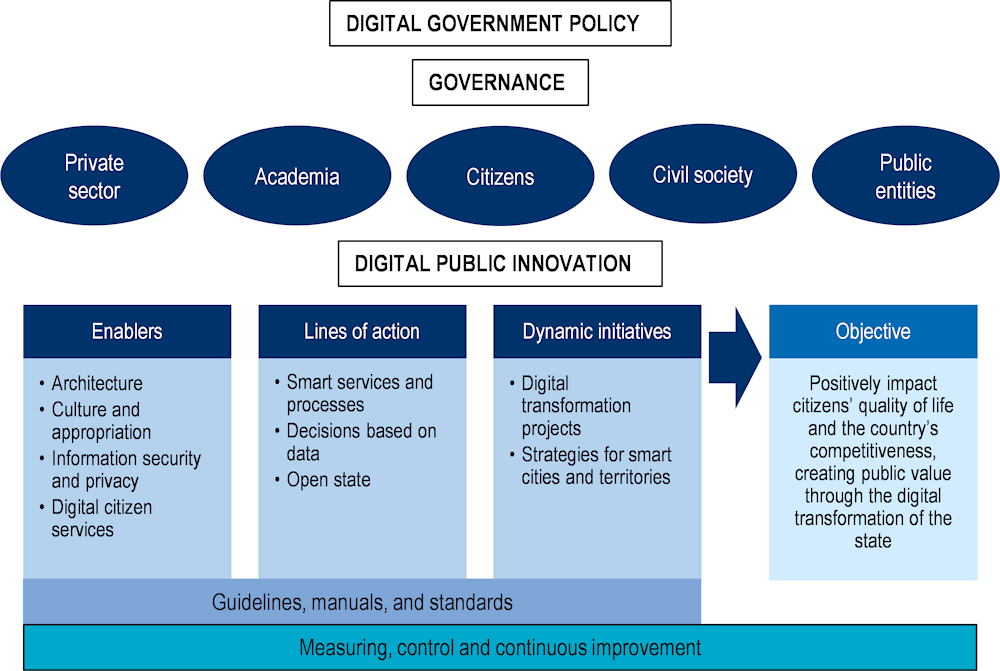

The objective of the PGD is to positively impact citizens’ quality of life and the country’s competitiveness, creating public value through the public transformation of the state in an inclusive, proactive and articulated manner, allowing the exercise of cyberspace user rights. PGD implementation relies on a network of institutions, illustrated in Figure 1.9.

Figure 1.9. Institutions supporting the PGD

Source: MinTIC (n.d.[7]), Digital Government (website), https://gobiernodigital.mintic.gov.co/ (accessed on 14 November 2023).

The PGD structure considers the following elements (Figure 1.10)

Governance: Relations between the national and subnational levels and between the central and decentralised levels. It also considers stakeholders in decision making, the definition of strategic actions and the allocation of available resources.

Digital public innovation: Creating public value by introducing creative solutions leveraging ICT and innovation methodologies to address public problems through a citizen-centred approach. In order to facilitate digital public transformation, public entities will leverage procurement processes that facilitate the acquisition of technologies that tackle public challenges but are not available in the market or, if available, require upgrades and improvements.

Enablers: Architecture, security and privacy of information. The framework agreement to procure computers is part of the architecture.

Lines of action: Actions to develop smart services and processes, take data-based decisions and consolidate an open state to articulate dynamic initiatives as part of the PGD.

Dynamic initiatives: Projects for digital transformation and strategies for smart cities and territories. These initiatives include the implementation of public procurement mechanisms that advance digital public innovation.

Figure 1.10. Structure of the PGD

Source: MinTIC (n.d.[7]), Digital Government (website), https://gobiernodigital.mintic.gov.co/ (accessed on 14 November 2023).

There is a set of rules governing the digital government policies and strategies in Colombia, dating back to 1985 and including primary laws, CONPES,2 directives, decrees, resolutions, agreements and other types of secondary regulations. The most recent element of this regulatory framework is Decree 767/2022, which establishes general guidelines for the PGD and was subject to public consultation on 12‑27 April 2022. Some of the principles established in this decree are directly related to technological neutrality:

Technological legality: The obligated subjects will ensure that the use of ICT is aligned with the Constitution and the regulatory framework.

Technological foresight: The obligated subjects will identify emerging technologies for implementation to fulfil their strategic objectives.

Technological resilience: The obligated subjects will take measures to mitigate risks that may affect digital security and, in this way, will ensure the availability of equipment, recovery and continuity of public services.

The decree mandates MinTIC to produce a Manual of Digital Government, which is available on line (https://gobiernodigital.mintic.gov.co/) and consolidates a series of guidelines and standards for PGD implementation. The manual establishes that public entities should submit technology initiatives to MinTIC’s Digital Government Directorate to receive methodological feedback. However, in clear contrast to the practices of Chile and Mexico, MinTIC only issues a technical concept on the application of the PGD guidelines but does not have the power to approve or block such initiatives.

Mexico

In Mexico, at the federal level, digital government policies and strategies run from the centre of government. In November 2018, the Organic Law of the Federal Public Administration (Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública Federal, LOAPF) was amended to establish a technical support unit at the executive level to define policies relative to ICT and digital government. Indeed, Mexico’s digital government policy is consolidated in the National Digital Strategy (Estrategia Digital Nacional, EDN) and led by the National Digital Strategy Coordination (Coordinación de Estrategia Digital Nacional, CEDN), a technical support unit of the Office of the President.

The National Digital Strategy

The EDN 2021-2024 entered into force on the day of its publication in the Official Gazette, 6 September 2021 and describes the actions to be undertaken by Mexico’s government aiming to enable the efficient, democratic and inclusive use and development of ICT. This roadmap for the institutions of the federal public administration steers technology and information security initiatives in a consistent direction, addressing their own needs and those of citizens while aligning with the policies established in the National Development Plan 2019-2024.

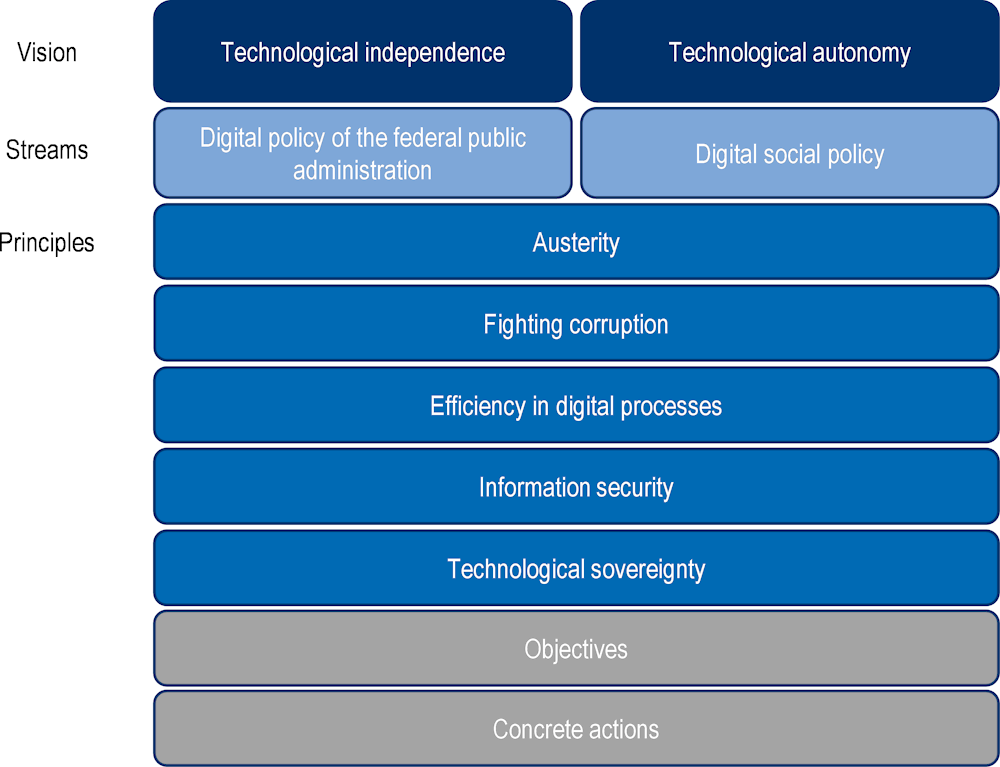

The EDN is organised in two axes of action: i) digital policy of the federal public administration; and ii) social digital policy to ensure citizens’ right to access ICT. Quite importantly, in terms of avoiding vendor lock-in, the EDN establishes the principle of technological independence, understood as avoiding being subject to commitments and conditions dictated arbitrarily by technology suppliers or producers, so as to also avoid monopolies and technical dependence. The other five principles guiding the EDN are:

Austerity: Achieving high-quality services with the best use of public resources and optimising spending.

Fighting corruption: Avoiding unfair, perverse, and damaging practices that benefit private interests to the detriment of the state.

Efficiency in digital processes: Streamlining the operations and focusing the attention of government procedures.

Information security: Ensuring the stability, protection and security of the information produced and stored in digital systems and platforms.

Technological sovereignty: Advancing the power to make decisions without external interference on digital and technology policies and strategies.

The EDN vision aims for a digitised country and an austere, honest and transparent government, with technological autonomy and independence, focused on citizen needs, particularly those of the most vulnerable. The EDN is then divided into nine specific objectives and 42 lines of action (Figure 1.11).

Objective 2 of the EDN – standardising ICT procurement through transparent, austere and effective actions leading to savings and the responsible use of public resources – is particularly relevant for the procurement of computers and ICT. This objective is disaggregated into three concrete actions:

Developing actions so that ICT procurement principles are standardised and promote competition. This entailed a policy to carry out ICT procurement through framework agreements.3

Making ICT procurement transparent.

Defining technical standards for ICT projects procured or developed and implemented leveraging institutional capacities.

Figure 1.11. EDN framework

Source: Government of Mexico (n.d.[8]), Mexico’s Official Gazette (6 September 2021), Agreement that Issues the National Digital Strategy 2021‑2024.

Other key actions envisioned by the EDN include the following:

Unifying ICT policies: Defining ICT projects following general policies from a single institution.

Verifying and analysing technical and economic feasibility of the projects: Focus on the need addressed.

Digitising administrative procedures previously simplified.

An opportunity for the EDN is to advance the idea that technology can be an enabler for service delivery and government efficiency beyond curtailing corruption.

The National Digital Strategy Coordination

The CEDN is a technical support unit attached to the Office of the President. Its mission is promoting and advancing access to ICT, broadband services and the Internet and their transformative potential for economic, social and cultural development. This mission is disaggregated into six objectives:

Regaining the stewardship of the state over governmental ICT and leveraging their potential for social development.

Contributing to an upgraded execution of ICT spending.

Leveraging the technical talent of the government to develop its own technologies.

Fighting corruption.

Participating in the improvement of governmental digital services.

Co-ordinating Internet connectivity and broadband strategies throughout the country.

CEDN powers also include designing and issuing specifications and standards for procuring and leasing ICT goods and services.

The CEDN carried out a review of the situation of governmental ICT starting in December 2018, which concluded that systems procurement, leasing, development, hosting and operations were being contracted without an analysis of horizontal impacts, leading to spending volumes that did not correspond to the benefits realised. It also criticised the lack of infrastructure owned by the state, as it was mostly being procured with private suppliers. Likewise, it indicated that the officials in charge of ICT in public institutions did not fulfil a technical profile or, when they had it, they were basically managing and monitoring contracts without significant participation in technical and operative decisions. In a nutshell, the conclusion was that the technical capacities of the government were weak.

Specifically referring to ICT procurement, the review found procured systems overlapping and addressing the same needs at different prices, lack of data compatibility, expensive development of systems and costly maintenance to obsolete systems.

The Agreement issuing policies and guidelines to advance the use and leverage of ICT, digital government and cybersecurity in the federal public administration

In order to address the weaknesses identified during the process to elaborate the EDN, the CEDN published the Agreement issuing policies and guidelines to advance the use and leverage of ICT, digital government, and cybersecurity in the federal public administration (the Agreement, hereinafter). It came into force the day of its publication, 6 September 2021. It replaced the Agreement that issued the administrative manual for general application relative to ICT and information security, published in the Official Gazette on 8 May 2014.

The Agreement’s objective is to dictate the policies and guidelines for using and leveraging ICT, digital government and information security. In line with the EDN, it aims to promote the use of free software and open standards, advancing technological independence and autonomy, and reducing costs and time in ICT procurement procedures.

Some of the general technology policies established in the Agreement include the following:

Favouring specific contracts stemming from framework agreements in force or the undertaking of consolidated procurement to ensure the best conditions for the state.

Meeting the technical standards set by the CEDN, certifying the standards and models recognised by the industry as best practices and meeting technical regulations (normas oficiales).

The Agreement also establishes the Portfolio of ICT Projects (Portafolio de proyectos de tecnologías de la información y comunicación, POTIC), which is the set of strategic and operative ICT and information security projects that public institutions plan to carry out during the next fiscal year.

The POTIC and the CEDN technical resolution

The integration of POTIC is a mechanism to formalise the planning of ICT projects and should include those projects developed with public institution's own resources and those outsourced to private suppliers. On the one hand, a strategic ICT project is defined as a project that implies a temporary effort to create an ICT product, service or outcome and whose implementation contributes significantly to the achievement of the institution’s strategic objectives. On the other, an operative ICT project is defined as a non-strategic project that implies a temporary effort to create an ICT product, service or outcome that supports daily operations. Both cases may or may not require the procurement of ICT goods or services.

In order to put together its POTIC, each institution may define its own methodology but should at least consider the following elements:

Size and requirements of the institution.

Co-ordination mechanisms between administrative units.

Institutional impact from ICT.

Technological architecture required.

Information assets and the Information Security Management Framework

Technical and operative capacities.

CEDN technical standards.

Each project included in the POTIC should be based on analysis that considers the following elements at least:

Background: Context prevailing before the project.

Problem statement: Clear and brief description of the issue to be addressed, including a general diagnosis of the problem.

Justification: Concrete description of the project’s motivation, explaining how the scope was determined.

Objective: Description of the expected outcomes stemming from the activities included in the project.

Impact: Concrete description of the contribution or significant effect stemming from the implementation of the project relative to the objectives of the National Development Plan, the EDN, the National Programme to Fight Corruption and Impunity and Improve the Public Administration (Programa Nacional de Combate a la Corrupción y a la Impunidad y de Mejora de la Gestión Pública, PNCCIMGP) and other institutional objectives.

Evaluation criteria: Perceptible and measurable characteristics defined by the institutional ICT Unit (Unidad de Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicaciones, UTIC) to monitor and assess the achievement of the project’s objectives.

Scope: General definition of the product, service or outcome to be achieved at the end of the project.

Start and closing date: Timeline for the execution of the project.

Date for project evaluation: Date on which the outcomes of the project will be evaluated.

Estimated budget: Plan for the allocation of financial resources for the execution of the project.

Timeline for project milestones: Brief description of the project’s phases.

Each public institution’s UTIC is the unit in charge of putting together the corresponding POTIC. Once reviewed by the senior management, it is uploaded to a platform in the July of every year. The CEDN then reviews each POTIC and makes recommendations to the different institutions to address and resubmit. Once the CEDN is satisfied, it approves the POTIC (visto bueno), by 31 October of the year prior to its implementation at the latest.

The POTIC, as authorised by the CEDN, is the basis and obligated reference for the analysis of technological resolution requests (dictamen técnico) for ICT procurement. In other words, all ICT procurement to be carried out should have been anticipated in the POTIC. A technical resolution is a document issued by the CEDN to approve an ICT procurement project: it is, in fact, an essential step for its execution,4 as explained in Chapter 2.

References

[6] DIPRES (n.d.), Homepage, Budget Office of Chile, https://dipres.gob.cl (accessed on 10 October 2023).

[8] Government of Mexico (n.d.), Mexico’s Official Gazette (15 August 2021), Agreement that Issues the National Digital Strategy 2021-2024.

[7] MinTIC (n.d.), Digital Government (website), https://gobiernodigital.mintic.gov.co/ (accessed on 14 November 2023).

[1] OECD (2023), Government at a Glance 2023 Database, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/publication/government-at-a-glance/2023/.

[4] OECD (2022), Towards Agile ICT Procurement in the Slovak Republic: Good Practices and Recommendations, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b0a5d50f-en.

[5] OECD (2020), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 03, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

[3] OECD (2015), Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/.

[2] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/recommendation-on-digital-government-strategies.htm.

Notes

← 1. As of March 2024, the DGD became the Secretariat of Digital Government, under the Ministry of Finance.

← 2. Public policy documents issued by the National Council for Economic and Social Policy (Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social, CONPES).

← 3. Consolidated ICT procurement is also envisioned but it has not been implemented.

← 4. Exceptions include the procurement of peripheric and minor supplies and the procurement, leasing and services below the value of 300 times the unit of measurement (Unidad de Medida y Actualización, UMA) in force. The value of the UMA in 2023 was MXN 103.74.