This section highlights key messages from the main chapters of the report on progress towards a green economy and remaining challenges in the countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia (EECCA). It also discusses a possible future direction of work under the GREEN Action Task Force hosted by the OECD. This aims to promote further policy reform and scale up financing for a rapid, ambitious and inclusive transition towards a green economy in EECCA countries.

Green Economy Transition in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia

1. Progress on the green economy transition in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, and future directions of the GREEN Action Task Force work

Abstract

Progress towards a green economy in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia (EECCA)1 have been undergoing profound changes, while pursuing their transformation towards market economies and democratic societies. These countries have retained some of their Soviet-period specialisations. However, most EECCA economies underwent important structural changes, trade liberalisation and privatisation. For example, the importance of the service sector has drastically increased in most of the EECCA economies (Gevorkyan, 2018[1]).

Countries of the EECCA region have been on long journeys to pursue economic development that is also environmentally sustainable. The last decade witnessed an accelerated awareness of, and more ambitious response to, local environmental impacts of the traditional path of economic development, and those of global trade. All EECCA countries have adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement on climate change (OECD, 2021[2]). The Eighth Environment for Europe Ministerial Conference – held in Batumi, Georgia, in 2016 – was an important step. It confirmed the EECCA countries’ commitment to improving environmental protection and advancing action towards sustainable development (UNECE, 2016[3]). These national-level commitments suggest that EECCA countries recognise the need for structural and institutional reforms in their economies and governance to support their rapid, ambitious and just transition towards a green economy.

Policy frameworks and governance arrangements towards a green economy

Many countries of EECCA have set and updated national targets to guide their transition towards a green economy, including on environmental protection, climate change and natural resource management. For instance, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic (hereafter “Kyrgyzstan”), the Republic of Moldova (hereafter “Moldova”), Ukraine and Uzbekistan have developed overarching national strategies and programmes on green economy. The adoption of the Concept on Transition to Green Economy of Kazakhstan dates to 2013, followed by the ongoing implementation of three major stages of actions towards 2050 (Kazinform, 2018[4]). Tajikistan is developing its national green economy strategy at the time of writing (Government of Tajikistan, 2021[5]). These high-level strategies and programmes have faced various implementation challenges. However, they have provided the EECCA countries with a foundation for integrating environmental considerations into broader sectoral development policies and targets, as well as mandates of government institutions in each country.

All EECCA countries have also adopted their national targets of climate action through their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) (Table 1.1). Many of the countries have also raised the levels of ambition of the climate mitigation targets through NDC update processes (OECD, 2021[2]). Further, countries such as Armenia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan have developed their targets on net-zero carbon emissions. Kazakhstan, Georgia and Uzbekistan, for example, have also started developing long-term low-emission development strategies (OECD, 2021[2]; Government of Georgia, 2021, p. 6[6]). Most EECCA countries have also started developing National Adaptation Plans (NAPs). Among them, Armenia submitted its NAP to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in May 2021 (Government of Armenia, 2021[7]). In addition to national-level strategies, the five Central Asian countries established a process of developing a regional climate change adaptation strategy. This aims to promote transboundary co-operation to strengthen climate resilience in the region (Green Central Asia, 2021[8]).

EECCA countries have also significantly advanced their efforts to modernise broader environmental policies and legislation at both strategic and technical levels. For example, Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine have been reviewing their legislative and institutional arrangements on environmental regulations, monitoring of implementation, and tools for enforcement and compliance promotion for further improvement (EU4Environment, 2021[9]; EU4Environment, 2021[10]).

There is clear evidence of progress on development of national-level environmental policy frameworks in the region. Uzbekistan adopted a series of environment-related laws such as the Concept on the Environmental Protection until 2030, Strategy on Municipal Waste Management for the period 2019-2028 and Strategy for the Conservation of Biological Diversity for the period 2019-2028 (UNECE, 2020[11]). The revised Environmental Code of Kazakhstan, adopted in 2019, has enhanced application of the “polluter pays” principle through environmental permits. The amendment aimed to ensure that polluters will take more appropriate measures to prevent negative impacts on the environment in cost-efficient ways (OECD, 2019[12]). Georgia has adopted a new law on environmental liability, and continues legislative reforms, including on industrial emissions and risk-based methodologies. The country has also adopted a Law on Environmental Liability that aims to define the legal regulation on issues related to environmental damage, based on the polluter pays principle (Government of Georgia, 2021[13]). To assess progress and effectiveness of environmental policies, several EECCA countries in partnership with the UN Economic Commission for Europe conducted Environmental Performance Reviews over the past decade: Uzbekistan in 2020, Kazakhstan in 2019, Tajikistan in 2017 and 2012, Belarus in 2016, Georgia in 2016 and Moldova in 2014 (UNECE, 2022[14]).

Table 1.1. Climate action: Status of NDC updates and net-zero targets in EECCA countries

|

Country |

Has mitigation ambition been increased in updated NDC? |

Has a net zero target been set? (type of policy document, covered sectors, target year) |

LT-LEDS communicated to UNFCCC? |

|

Armenia |

Yes |

Yes (in NDC, economy-wide, 2050) |

No |

|

Azerbaijan |

Unclear |

No |

No |

|

Belarus |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Georgia |

Yes |

No |

Under development |

|

Kazakhstan |

No |

Yes (in declaration, economy-wide, 2060) |

Under development |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Moldova |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Tajikistan |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Turkmenistan |

Unclear |

No |

No |

|

Ukraine |

Yes |

Yes (in policy document, economy-wide, 2060) |

Yes (2018) |

|

Uzbekistan |

Yes |

Yes (in declaration, energy sector, 2050) |

Under discussion |

Note 1: UNFCCC=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. LT-LEDS = Long-term low emission development strategy, NDC=Nationally Determined Contribution

Note 2: For further details, see Chapter 3

Source: Based on (OECD, 2021[2]) and updated

The development of those national strategies and policies has in many cases also been accompanied by the creation of several inter-ministerial co-ordination mechanisms. They aim to facilitate cross-ministerial dialogue on the integration of green and environmental considerations into development policy processes. Georgia has added “Sustainable Development” to the official name of its Ministry of Economy. Moldova and Kyrgyzstan created inter-ministerial committees that co‑ordinate policy processes on greening economic development in their respective countries. These are also examples of initiatives that have attempted to place the green agenda closer to economic and financial decision-making bodies.

There has been a positive development in strengthening environmental ministries and agencies in some EECCA countries, although the governments were undergoing frequent changes. For example, within the new governmental structure, adopted by the Parliament of Moldova in 2021, the Ministry of Environment was restored as a separate institution. It has become the central body for development and promotion of national environmental protection policies and rational use of natural resources. The ministry has approved 62 posts, doubling its staff. Conversely, 29 experts work on the environment within the Ministry of Agriculture, Regional Development and Environment. Ukraine undertook prolonged institutional reform of environment administration. During that time, the Ministry of Environment was first merged with the Ministry of Energy, and a separate Ministry of the Ecology and Natural Resources was re-established. Kazakhstan also re-established the Ministry of Ecology, Geology and Natural Resources in 2021.

Emerging trends that drive the green economy agenda in EECCA countries

Several countries of Eastern Europe and the Caucasus2 have been aligning their environmental policies with EU laws and standards in the context of the EU Association Agreements, and for Armenia, a Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (Andrusevych et al., 2020[15]). These Agreements have also provided countries such as Armenia3, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine with a framework for enhanced political and economic links with the European Union and approximation towards far-reaching legislation, including the EU’s Water Framework Directive (OECD, 2021[16]). The EU Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) and the Environmental Liability Directive (ELD) have driven efforts to improve environmental legislative set-ups for compliance assurance in many Eastern Europe and Caucasus countries (EU4Environment, 2021[17]). The Eastern Europe and Caucasus countries have been reforming environmental permits for large emission sources in compliance with the EU IED. This has meant greening small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and translating recommendations into actual changes to environmental regulations (EU4Environment, 2021[17]). In this context, Azerbaijan and Moldova launched their online self-assessment tools for greening SMEs to help them evaluate their environmental performance, increasing competitiveness by reducing their costs (EU4Environment, 2021[17]). Armenia launched a project to assess how implementation of the EU Best Available Techniques reference documents (EU BREFs) on extractive waste can improve the environmental management in the mining sector (EU4Environment, 2021[17]).

EECCA countries have integrated green stimulus measures into their response to the COVID-19 pandemic and their broader recovery packages (Neuweg and Michalak, forthcoming[18]). Analysis under the Green Action Task Force identified approximately USD 360 million allocated to green recovery measures in the EECCA region between 2020 and February 2022 (Neuweg and Michalak, forthcoming[18]). Selected examples are highlighted below:

Uzbekistan invested in infrastructure for improved water supply and sanitation, as well as irrigation, through its Anti-Crisis Fund (OECD, 2021[19]). The country has also provided financial support for energy efficiency improvements in industry.

Azerbaijan supported activities to restore degraded lands for sustainable dryland agriculture (Neuweg and Michalak, forthcoming[18]).

Armenia created a short-term employment programme in the agricultural sector. It provided work for vulnerable communities, while improving resilience and water quality through reforestation of riparian zones (OECD, 2021[19]).

Moldova supported development of villages in the Coșnița area as sustainable tourism destinations, improving service delivery to the local community (OECD, 2021[19]).

The Rural Development Agency of Georgia incentivised its beneficiaries to adopt resource and energy efficiency practices (OECD, 2021[19]).

Georgia and Moldova also provided finance support to micro, small and medium enterprises that qualified as innovative and green (Neuweg and Michalak, forthcoming[18]).

Efforts to scale up financing for green economy transition in EECCA

In recent years, EECCA countries such as Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine have embarked on efforts to align the policy objectives of financial-sector development with their national climate and environmental targets. EECCA countries have increasingly recognised the importance of mobilising private-sector finance for sustainable investment. They have also been developing policy frameworks and capacity to use funding from governments and development finance institutions (DFIs) more wisely to catalyse private-sector investment.

A functioning, stable and deeper banking sector is a precondition for economic growth and investment promotion in general, and provides an important basis for green finance mobilisation. In Kyrgyzstan, a sustainable finance roadmap forms an integral part of the country’s Green Economy Development Programme adopted in 2019, and sets out plans for the country’s transition towards a green economy (SBN, 2020[20]). The National Bank of Georgia (NBG) adopted a Roadmap for Sustainable Finance in Georgia; the NBG Principles on Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) Reporting and Disclosure; and a Sustainable Finance Taxonomy (NBG, n.d.[21]). Kazakhstan established the Green Finance Centre under the Astana International Financial Centre. The centre issued a Statement of Commitment to Sustainable Finance Principles. It has developed various standards such as AIX Green Bond Rules and led the issuance of green bonds in the country (AIFC Green Finance Centre, n.d.[22]).

Kazakhstan was the first country in the EECCA region to issue a green bond but other countries soon followed suit, such as Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine. Uzbekistan also issued the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Bonds to finance projects supporting the country’s efforts to achieve the SDGs. The SDG bonds have been used to finance, among others, some water supply and sanitation projects. Between the second half of 2020 and early 2022, eight green bonds issued in the region – two in each of the four countries – amounted to about USD 2 billion (OECD, forthcoming[23]). The OECD study on the use of green bonds in the EECCA regions shows that in total about USD 2.2 billion was raised through these bonds, with the bulk coming from issues by two Georgian and two Ukrainian entities on international markets. This underlined the strong interest at the time by investors in sustainability-related exposures in the region. The green bond issued on the local markets in Armenia and Kazakhstan raised relatively limited amounts, though demonstrated the local green finance framework and, in the case of an Armenian bank, the capacity to generate and refinance a portfolio of green assets. (OECD, forthcoming[23]).

While capital markets in EECCA countries are not yet contributing significantly to financing green investments, green bonds are becoming an asset class in their own right. Green bonds have begun to gain traction in the region as a complement to bank financing (OECD, forthcoming[23]). The regulations and the market infrastructure supporting the expansion of local capital markets are being developed and improved to support issuers and investors. However, this issuance is still limited, only nascent and takes part in the corporate sector, with little engagement by governments to date. Based on the experience of other countries, issuance of sovereign green bonds can send the right signals to market participants and help transform bond markets to finance the green transition.

Improving environmental footprint of economic activities in EECCA

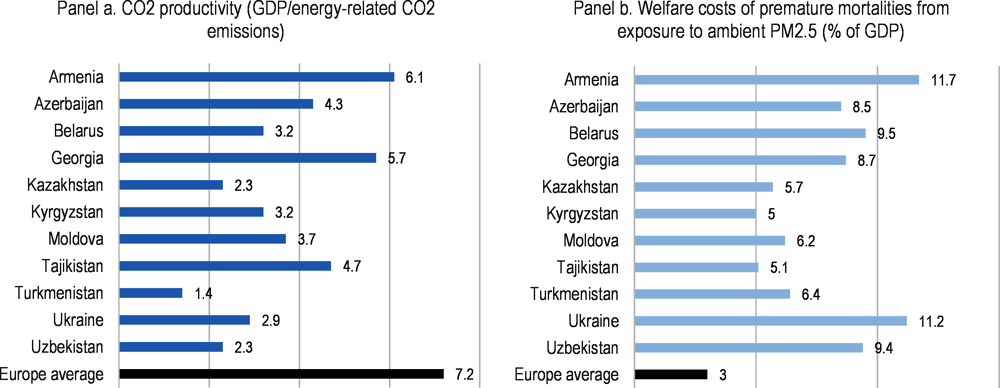

In line with those policy reforms, several indicators have shown signs of progress in resource productivity and environmental quality in the EECCA region. However, a significant improvement remains necessary. EECCA countries have collected data based on the Green Growth Indicators in partnership with the OECD. The Indicators chart some of the environmental footprint of economic activities in the region. For instance, carbon and energy productivity has continued to increase. This means that EECCA countries’ economic growth partially decoupled from carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and use of energy. Although progress is encouraging, there remains much room for improvement. EECCA countries’ CO2 and energy productivity is much lower than the EU countries’ average (Figure 1.1). Exposure of the population in the region to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) remains high. Associated welfare costs of premature deaths due to PM2.5 pollution represent up to 12% of gross domestic product (GDP) equivalent in some of the EECCA countries, which is considerably higher than the European average of 3.0% (OECD, 2022[24]).

Figure 1.1. CO2 productivity (Panel a) and welfare costs of premature deaths due to PM2.5 pollution (Panel b) in the EECCA region and European average

Remaining challenges and further opportunities for green and inclusive growth in the region

Despite steady progress since 2016, the achievement of EECCA countries’ national targets towards a green economy transition is still facing a range of political and technical challenges. Many of them go far beyond the remit of environmental administration. For example, political tensions continued between Armenia and Azerbaijan, with episodes of military clashes. Meanwhile, Georgia and Moldova each experienced high levels of instability in domestic politics following anti-government protests in 2020 and elections in 2021. Similar social protests occurred in Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. These prolonged conflicts and tensions create an unstable base for policy, institutional and legal developments. This can stifle any progress on making and implementing policy. In 2022, Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine resulted in a humanitarian and economic crisis.

Access to affordable financing, and effective use of it, has consistently been among the greatest challenges to planning and implementing action on the countries’ efforts for a green economy transition (OECD, 2018[25]). This challenge is further constrained by the slowed economic growth rates and protracted geopolitical uncertainty in the EECCA region. There have been signs of a slowdown in the COVID-19 recovery in the region since 2021 (World Bank, 2022[26]). Reduced economic activities and trade, inflationary pressures, debt sustainability concerns and rising interest rates have all made it even more challenging for countries to access affordable financial resources, including those for green investment. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has amplified the challenge through the sharp declines in remittances, commodity trades, migration, and investor confidence and foreign direct investment across the whole region (World Bank, 2022[26]; EBRD, 2022[27]).

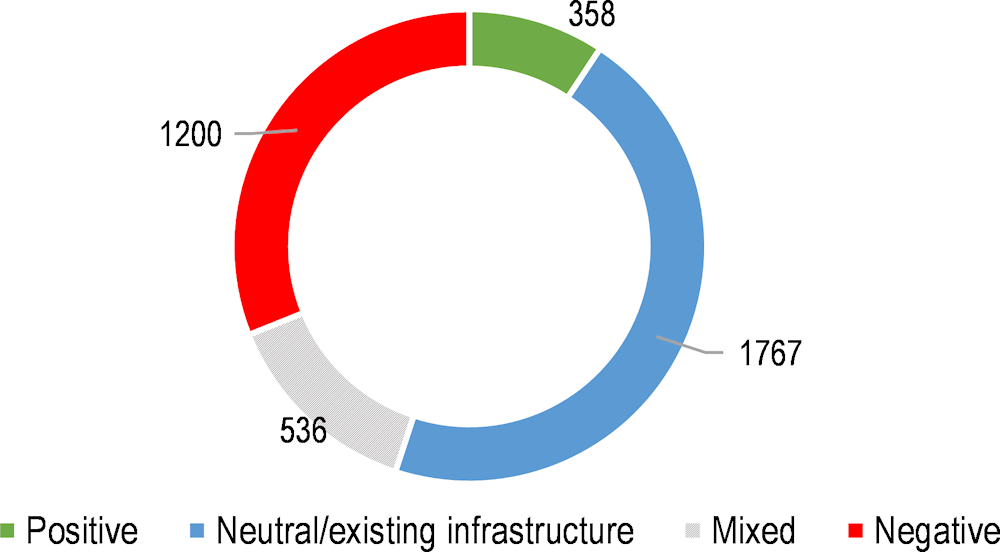

According to assessments of COVID-19 recovery packages, funding is more likely to have a mixed or negative impact on the environment than a positive one. These assessments, conducted under the GREEN Action Task Force, show total COVID-19 recovery funding volume allocated to measures with a mixed or negative impact on the environment is almost five times larger than for those with a positive impact. As shown in Figure 1.2, only approximately USD 360 million went to recovery measures with a positive environmental impact from the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis in 2020 to February 2022. The data also show that more than USD 1.7 billion was allocated to measures with a mixed or negative environmental impact (Neuweg and Michalak, forthcoming[18]). Almost USD 1.8 billion was allocated to existing infrastructure or to measures that are unlikely to have a sizeable environmental impact. However, they perpetuate business-as-usual economic activities and do not contribute to the transformative changes needed to shift towards a green economy.

Figure 1.2. Total COVID-19 recovery funding allocated by environmental category (from 2020 to February 2022)

Source: OECD EECCA Green Recovery Database.

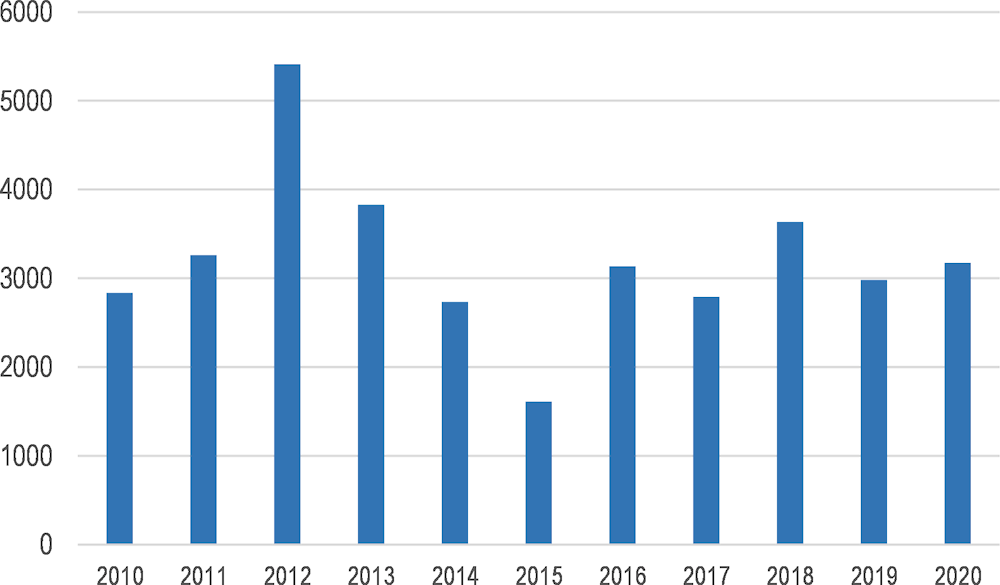

Reforming fossil-fuel subsidies and support is a key policy measure to tackle climate change, reduce pollution and contribute to long-term energy security in the EECCA region. However, progress on subsidy reforms remains slow. The COVID-19 crisis made the countries painfully aware of the need to mobilise significant additional funds to support their health systems and economies. Both economic activity and energy prices dropped in 2019 and 2020. However, total government support to producers and consumers of fossil fuels in the Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region increased by more than 6% over the same period (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Trends on fossil-fuel subsidies in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus countries

Note: Inventory records tax expenditures as estimates of revenue that is forgone due to a feature of the tax system that reduces or postpones tax relative to a jurisdiction’s benchmark tax system (and to the benefit of fossil fuels). Hence, tax expenditure estimates could increase either because of greater concessions, relative to the benchmark tax treatment, or because of an increase in the benchmark itself. In addition, international comparison of tax expenditures could be misleading due to country-specific benchmark tax treatments.

Source: OECD Fossil-Fuel Subsidies database, www.oecd.org/fossil-fuels/data/

Ambitious long-term strategic plans for fulfilment of requirements under the EU Association Agreements and international environmental commitments have also revealed significant legislative and institutional challenges (OECD, 2021[16]). On water management, for example, it is unlikely that Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine will fully meet their stated policy targets by 2030, if the countries follow a business-as-usual application of policy frameworks (OECD, 2021[16]). Challenges are numerous, including legal and regulatory gaps; insufficient implementation of adopted actions; and insufficient capacity and head count of national experts on subject areas. Other barriers include inconsistent development and application of economic policy instruments and co-ordination challenges due to fragmented institutional frameworks. These areas have all been leading to inefficiencies in water management, and broader environmental management, in the countries (OECD, 2021[16]).

There is also considerable scope for promoting infrastructure projects that will boost investment and employment in EECCA countries, while addressing energy security concerns and contributing to decarbonisation. The governments of EECCA and their development partners have been increasing their efforts to develop sustainable infrastructure projects to improve energy efficiency and integrate renewables into the energy supply. In most cases, however, the current projects do not reach the scale needed for transformation and perpetuate regional dependency on fossil fuels (OECD, 2019[28]; OECD, 2021[29]). In the transport sector, most EECCA countries are investing more intensively in road projects than in other modes of transport. At the same time, they are underspending on maintenance and modernisation of rail assets. This means that railway systems in these countries continue to be inefficient (OECD, 2019[28]; OECD, 2021[29]).

Water infrastructure in EECCA countries is also generally under-developed, and suffers from constrained access to funding for promoting environmentally and economically sustainable water management. Any infrastructure is often in poor condition due to chronically under-funded maintenance and repair, and lack of systematic rehabilitation. Poor water policy frameworks in the region often increase future financial liabilities and further demand for finance for operational and capital expenditure. In this way, they also contribute to lack of funding. In addition, outdated design and construction standards have led to building significantly over-sized water supply and sanitation systems in rural areas. Meanwhile, counter-productive incentives remain in place to build assets in areas prone to water-related natural hazards.

Environmental and climate policies need to be adaptive to the increasingly diverse country contexts and evolving socio-economic, geopolitical and climatic conditions in the region

The transition to green and net-zero economy requires significant acceleration and the context of the war in Ukraine provides additional reasons for this fundamental transformation. Priority should be given to moving away from the reliance on fossil fuels, building more efficient and less polluting industries, and energy and transport systems. The housing stock, schools and hospitals should also improve their energy efficiency and use low-carbon material. EECCA countries should also strengthen their capacity to reform policies, develop infrastructure, provide social safety net and conserve biodiversity so their economies, populations and ecosystems better address negative impacts of climate change.

Efforts to support the transition to a green economy should be context-specific. This requires consideration of economic, environmental and geopolitical risks to individual EECCA countries, as well as their experience of known and tested approaches to manage the risks. The economies of EECCA, once under the common system of the Soviet Union, are becoming increasingly diverse in their own socio-economic contexts and development pathways. For instance, the Eastern Europe and Caucasus sub-region is increasingly aligning environmental policies with those of the European Union. Central Asia’s economic, trade and political ties with Russia have remained strong, while the countries have been deepening relations with the People’s Republic of China through the Belt and Road Initiative. In addition to the differences between the two sub-regions, each EECCA country has a specific economic structure, political priorities, development needs and institutional arrangements. For example, EECCA countries have pursued various pathways to respond to the COVID-19 crisis and advance recovery efforts [See, for example, Annex 1 of OECD (2021[30])].

Uncertainties stemming from various sources make it challenging for EECCA countries to assess and select policy and investment options that can support their green economy transition. For example, the socio-economic and geopolitical impacts of the war in Ukraine create many uncertainties. EECCA countries, like others across the world, also face a great degree of uncertainty as to how climate change may translate into impacts on the ground. Uncertainty in broader socio-economic and technological contexts in the region compounds political and climate uncertainties, greatly affecting decisions in support of a green economy transition.

Climate change is already affecting socio-economic systems in the EECCA region to varying extents, presenting a dynamic and uncertain future (Botta, Griffiths and Kato, 2022[31]). In Central Asia, one of the most vulnerable regions to climate risks, climate change scenarios suggest that surface temperature in the region could rise from 3°C to 7°C on average for 2071-2100 compared to 1950-2001 (Liu, Liu and Gao, 2020[32]). Choices of policy measures and infrastructure developments for an increase of 3°C could differ significantly from those for a 7°C increase. The negative impacts of a changing climate are occurring, and likely to increase, on top of socio-economic challenges to managing water, energy and land in the region. Similarly, Eastern Europe and the Caucasus countries are also becoming increasingly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, such as damages from frequent extreme weather events (Kampel and Gassan-Zade, 2021[33]).

Future direction of the GREEN Action Task Force work

The long-standing collaboration between the countries of EECCA and the OECD through the GREEN Action Task Force has produced the country- and region-specific evidence to inform the environmental and climate-related policy reforms over the past decades. Collaboration relates to, for instance, pragmatic policy options, investment needs for their implementation and effectiveness of the policies in light of the EECCA countries’ green economy programmes, environmental legislation, NDCs and other strategic documents on sustainable development. The Task Force has also developed, and provided EECCA countries with, a range of practical tools to support policy processes and financial decision making. These tools include Green Public Investment Programmes, a web platform on Green Growth Indicators and the Water-Hydropower-Agriculture Tool for Investments and Financing (WHAT-IF).

Country ownership of policy reforms is crucial and future work of the Task Force should build on the progress in EECCA countries over the past decades. Work should continue to help countries address remaining gaps in institutional capacity, governance arrangements and access to finance. The Task Force shall continue to act as a provider of robust evidence tailored to the region. This includes evidence on practical examples of policy measures in support of green economy transition, policy-relevant Green Growth Indicators and financial flows that support or undermine green economy activities.

The Task Force should continue, and reinforce, the effort to make its knowledge products even more relevant to policy processes in the individual countries, and readily accessible to stakeholders in the governments and their development co-operation partners across the EECCA region. Various approaches should continue to be enhanced, such as policy dialogues and policy reviews. The Task Force could also envisage activities such as pilot testing of policy recommendations and facilitation of cross-regional exchange for scalability and replicability of good practice throughout the region.

The work programme of the Task Force for 2023-24 envisages supporting national-level policy dialogues on greening the economies of EECCA, and enhancing administrative capacity for environmental management and cross-ministerial co‑ordination for green growth. The Task Force will continue to facilitate knowledge sharing and in-country development of “smarter” regulation of environmental performance, especially on climate change mitigation and air pollution abatement. Another focus is on strengthening the economic and financial dimensions of water management through analytical work and the multi-sector National Policy Dialogues on water.

Work on sustainable finance and investment will also continue. The Task Force will continue supporting the development of green domestic public expenditure programmes and financial instruments. Further, while capital markets in EECCA countries are not yet significantly financing green investments, the Task Force has started exploring use of green bonds as an asset class to promote sustainable finance in some countries. Further upstream in the infrastructure investment cycle, the Task Force will also promote sound decision making in strategic planning and analyses of investment projects to prioritise sustainable infrastructure for low-carbon development in the region.

Beyond 2023-24, EECCA countries and their partners, including the GREEN Action Task Force, can do more to make the countries’ action on green economy transition more ambitious, equitable and efficient, while also keeping the action practical and doable. Several opportunities exist for the Task Force to enhance its support for the EECCA region for the several years leading up to the tenth Environment for Europe Ministerial. Possible future directions for the Task Force to further strengthen its support for EECCA countries and their development co-operation partners are highlighted below.

Support EECCA countries in enhancing action for the next several years to exploit the opportunities for green recovery from recent external shocks

The Task Force work should adapt to emerging and future changes in political, socio-economic, technological and climatic conditions. Among the most notable examples is addressing the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. These impacts have triggered the most severe recession in the economies of EECCA in recent years. The pandemic has caused enormous damage to people’s health, jobs and well-being, which will continue to be felt in the months and possibly years to come. The Task Force should continue to provide countries in the region with the necessary support for a green and inclusive recovery from the impacts of current and future external shocks. Its support could aim at, for instance, improving enabling policy frameworks and hands-on capacity development for scaling up investment in renewable energy, low-emission transport, energy efficiency and Nature-based solutions (NbS) for climate action and biodiversity conservation.

The Task Force should therefore continue to help countries enhance their COVID-19 recovery packages and broader policy frameworks to close investment gaps for high quality, reliable and sustainable infrastructure services. They may focus on, for instance, electricity generation and distribution, mobility, drinking water and sanitation, and waste management, to name a few issues. The Task Force work could help countries apply some of the important principles to facilitate access to finance for infrastructure investment that is environmentally and socially sustainable, knowledge-based and resilient to unforeseen future shocks. Such principles include:

better alignment of planning with national priorities and international long-term goals

better prioritisation of projects that maximise economic, environmental and social benefits

better governance of infrastructure projects to achieve green outcomes

better mobilisation of finance (OECD, 2019[28]; OECD, 2021[29]).

Future work of the Task Force could also consider the medium- and long-term repercussions of the war in Ukraine. In co-ordination with various national, regional and international actors, the Task Force could help assess the impacts of the war on national economies, regional relations and countries’ environmental sustainability agendas. The Task Force could also provide policy support for the post-war reconstruction and its environmental integrity, where relevant. The Memorandum of Understanding on Strengthening Co-operation between the OECD and Ukraine, which defined the co‑operation framework, has been extended until 2025 (OECD, 2022[34]). The Task Force could further elaborate its support in line with the OECD-Ukraine Action Plan (in support of Ukraine’s own Recovery Plan) for the next several years (OECD, 2022[34]).

Contribute to energy, environmental and natural resource security

The Task Force should also put more emphasis on energy, food and natural resource security in a changing climate in the EECCA region. As in many other regions, energy, food and natural resource security has always been among the top political priorities in the EECCA region. Russia’s war against Ukraine has generated another shock to confidence and growth in the countries, putting the post-pandemic recovery at risk. Climate change is also likely to pose even greater challenges to food availability, access and affordability in many EECCA countries. This is especially true for the most vulnerable and excluded segments of society who often face discrimination. The Task Force should work with policy makers and development partners in the EECCA region to understand interlinkages among issues related to energy, food, and natural resource management and climate risks. To achieve this, the Task Force should aim to provide practical solutions to those compounded challenges, while building the resilience of socio-economic systems to enhance energy, and food and natural resource security.

The Task Force should further support the countries in promoting climate and environmental policy reforms in a socially inclusive manner. The pandemic and Russia’s war against Ukraine have led to severe trade disruptions, decline in remittances, high food prices and insecurity of energy supplies in the region. In many cases, these impacts have made life more difficult for the most vulnerable of society. Green recovery policy packages could simultaneously aim to boost employment rates and wider social benefits, while phasing out ageing production methods that are polluting. The Task Force has already started analytical work to support the EECCA governments in understanding their populations’ current and future well-being. One study looked at the fiscal, environmental and social impacts of energy subsidy reform in Moldova with a particular focus on energy affordability (OECD, 2018[35]). The Task Force can build on this analysis. Ultimately, EECCA countries can integrate it into decision-making processes to increase the political and social support for more ambitious climate action and environmental policies, and to overcome barriers for change.

Put more emphasis on support for the EECCA countries’ efforts towards the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework

The draft post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework calls for urgent, transformative action to address biodiversity loss across the world, including in EECCA. This framework is expected to be adopted at the 15th Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. The new Global Biodiversity Framework is likely to affect national and regional policy processes on biodiversity conservation and natural resource management within all Parties, including EECCA countries. The past collaboration between EECCA countries and the GREEN Action Task Force has already included certain aspects of ecological conservation, including work related to water quality and environmental compliance, as well as a recently launched Sustainable Infrastructure Programme in Asia.

The Task Force could put greater emphasis on ecological sustainability in its future work. The Task Force should work more closely with EECCA countries and development partners to ensure that protection, restoration and sustainable use of ecosystem services is an integral part of its support for a green economy transition in the region. Environmental degradation, population growth and lifestyle choices in the EECCA region increase demand for natural resources. The Task Force should align its support for a green economy transition with regulations to protect the environment and restore, manage and conserve ecosystems.

A range of past and ongoing work at the OECD on biodiversity and Nature-based solutions (NbS)4 could inform development of activities under the Task Force. The role of the natural environment in strengthening climate resilience and transitioning to net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is increasingly recognised. The GREEN Action Task Force can build on various OECD analyses and good practice insights for biodiversity policy generated over the past decades. One priority area for the OECD is to support its member and partner countries in reforming government support, including subsidies, that is harmful to biodiversity. This priority could also be applied to the GREEN Action Task Force [See OECD (n.d.[36])].

NbS activities emerging with the Task Force should be enhanced across overall work areas. The Task Force plans to explore possible application of NbS to improve water management in the Eastern Europe and the Caucasus countries, as well as financing opportunities for NbS. The Sustainable Infrastructure Programme in Asia also plans to support EECCA countries for infrastructure planning that considers protection of natural capital, ecosystem services and biodiversity. Similarly, the Energy, Water and Land-use Nexus project will develop a handbook with a focus on finance for NbS in Central Asia over the next five years. It will aim to foster understanding among policy makers of potential NbS opportunities and how they could be financed.

Make financial systems in the EECCA countries environmentally, socially and economically sustainable

The Task Force should strengthen its engagement with finance, economy and planning ministries in the EECCA countries in addition to environmental and sectoral ministries and agencies. Over the past several years, the Task Force has continuously deepened its co-operation with the economy and planning ministries. The economy and finance ministries in the region are increasingly involved in developing national green economy strategies or more specific policies or regulations. This includes sustainable public procurement, sustainable finance and subsidies reforms. The Task Force work could also help finance and economy ministries improve regulatory frameworks and institutional capacity to attract investments in infrastructure and businesses with appropriate environmental and social safeguards.

The Task Force work on sustainable finance could inform further efforts by economy and finance ministries to integrate green economy considerations into their budget planning and help rationalise fiscal policies and strategies. A range of relevant Task Force work has already taken place. This includes work on green public investment programmes (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Moldova), fossil-fuel subsidies, environmental funds (especially in Ukraine and Moldova) and green financial systems (especially Georgia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan), among others. One priority is to monitor and assess current and planned spending towards overall investment needs. This could build on, for example, the investment needs assessments in Armenia and Georgia conducted under the Task Force (OECD, 2018[37]; EU4Environment, 2021[38]).

The Task Force could support other areas to promote sustainable finance in the EECCA region. Other potential areas of support include greening public financial management; linking environmental and climate considerations to development of domestic financial systems; and encouraging national DFIs to promote investment in green economy transition through de-risking instruments. The Task Force can continue to help the EECCA countries co-ordinate and plan for improved financing strategies across line ministries and levels of government.

The Task Force could also support interested EECCA countries, especially their financial regulators and central banks, in strengthening their domestic financial systems so that they are greener and more socially inclusive. The Task Force could support development of national roadmaps, taxonomies that define sustainable economic activities, voluntary or mandatory disclosure principles on reporting on environmental, social and governance related financial and non-financial information. Past collaborations between central banks (Georgia and Kyrgyzstan) and the Task Force could be a good practice to replicate.

The Task Force can further help the EECCA countries develop financial-sector regulations and market infrastructure to support expansion of local capital markets. The Task Force can assess country-specific opportunities to access capital markets to support green investments. As mentioned earlier, there have been encouraging signs of the effectiveness and feasibility of green bonds and an increasing interest within the region (e.g. Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan) (OECD, forthcoming[23]). The Task Force could help interested EECCA countries explore approaches to seize the momentum and address challenges to further scaling up green bonds in the region.

Strengthen engagement with DFIs and other development partners active in the EECCA region, and potentially with those outside the region

The Task Force should deepen and broaden its engagement with DFIs to help EECCA countries further mobilise sustainable financing from various sources – international, domestic, public and private. The Task Force has been working with domestic and international DFIs on various projects focused on green finance over the years. This engagement can be further deepened to help governments and businesses in the region identify project concepts for domestic and cross-border investments in sustainable development infrastructure and business activities, environmental data and information and associated capacity development activities. By working with DFIs and relevant market participants, the Task Force’s analytical work should also help project developers and owners better understand and access suitable financial instruments, such as grants, loans, bonds, de-risking instruments.

The Task Force should further explore approaches to strengthen exchange among the private sector, financial institutions, government bodies, civil society organisations and development partners. The OECD has been working with a number of development partners under several programmes, such as EU4Environment projects, the EU Water Initiative Plus for Eastern Partnership Countries, and the Sustainable Infrastructure Programme in Asia. This collaboration has enabled the Task Force to harness different expertise of the participating partners for addressing multi-faceted, inter-linked issues faced by EECCA countries to promote their green economy transition. The Task Force should build on and broaden engagement with international development partners and regional institutions within EECCA.

Multi-stakeholder engagement across different actors and sectors, including the private sector, would help the EECCA countries integrate environmental and climate considerations into policies in support of enhancing competitiveness and economic. The Task Force has launched a new programme in Central Asia to support the private sector, financial institutions and government agencies in identifying financing opportunities. One area, for example, is agribusinesses in support of the energy, water and land-use nexus (OECD, 2021[39]). The Task Force is also developing sustainable trade-related agricultural and industrial value chains in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region. Such private-sector engagement would also inform the development of pragmatic and “smarter” environmental regulation that is both effective for environmental protection and realistic for businesses.

Opportunities exist for the Task Force to engage with a broader range of OECD member countries and non-OECD countries outside the EECCA region. Such engagement can promote exchange of lessons learnt and good practices outside the region that can be applied to EECCA countries. Experience in cross-sectoral co-operation in integrated resource management in Latin America or West Africa, for example, could bring practical insights into government officials in Central Asia.

Continue and reinforce Task Force work to address persistent gaps in ensuring compliance with adopted strategies and policy frameworks to ensure a green economy transition of the region

The Task Force has been working with EECCA countries on environmental compliance assurance systems for more than two decades to strengthen their capacity. To achieve a range of environmental and climate targets set by EECCA countries, countries need to take practical action, and monitor compliance with relevant regulatory frameworks. While past Task Force work has led to significant improvements in these areas, capacity and policy gaps persist. The Task Force should ramp up its effort to support the countries in getting the basics right to ensure compliance with adopted environmental regulations.

Further work by the Task Force with the countries should help them ensure that legislative frameworks for compliance assurance are up-to-date and fit-for-purpose, and provide sufficient incentives for voluntary compliance and sanction for non-compliance. Such support could help countries introduce legislation on integrated environmental control and environmental liability, as well as fulfilment of Association Agreement provisions on compliance assurance. The Task Force can help improve the institutional set-up for compliance assurance. This could focus especially on newly established environmental inspectorates and their co-ordination with other governmental authorities, skills development, information systems and equipment, and anti-corruption measures. The Task Force could continue to help countries improve their environmental inspections and other tools for monitoring compliance, including self-monitoring mechanisms. It could also help strengthen enforcement of compliance, including design and application of penalties for non-compliance, environmental liability provisions and environmental insurance mechanisms. Finally, the Task Force work could support EECCA countries with more promotion of voluntary compliance through, for instance, better information, training and incentives for adopting green practices.

References

[22] AIFC Green Finance Centre (n.d.), “AIFC Documents on Green Finance”, webpage, https://gfc.aifc.kz/aifc-documents-on-green-finance/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

[15] Andrusevych, A. et al. (2020), “European Green Deal: Shaping the Eastern Partnership Future”, Policy Paper, Resource and Analysis Center “Society and Environment”, https://www.rac.org.ua/uploads/content/593/files/webeneuropean-green-dealandeapen.pdf.

[31] Botta, E., M. Griffiths and T. Kato (2022), “Benefits of regional co-operation on the energy-water-land use nexus transformation in Central Asia”, OECD Green Growth Papers, No. 2022/01, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7fcec36c-en.

[27] EBRD (2022), “Regional Economic Prospects”, webpage, https://www.ebrd.com/what-we-do/economic-research-and-data/rep.html (accessed on 13 September 2022).

[38] EU4Environment (2021), An Assessment of Investment Needs for Climate Action in Armenia, OECD, Paris, https://www.eu4environment.org/app/uploads/2021/04/Report-Assessment-of-Investment-Needs-for-Climate-Action-in-Armenia-up-to-2030.pdf.

[10] EU4Environment (2021), “The environmental compliance assurance system in Armenia: Current situation and recommendations”, (brochure), EU4E Environment, https://www.eu4environment.org/the-environmental-compliance-assurance-system-in-armenia/.

[9] EU4Environment (2021), “The environmental compliance assurance system in the Republic of Moldova: Current situation and recommendations”, (brochure), EU4Environment, https://www.eu4environment.org/the-environmental-compliance-assurance-system-in-the-republic-of-moldova/.

[17] EU4Environment (2021), Towards a green economy in the Eastern Partner countries: Progress at mid-term (2021), (brochure), EU4Environment, https://www.eu4environment.org/app/uploads/2021/09/EU4Environment-mid-term-brochure-pre-printed-version-web.pdf.

[1] Gevorkyan, A. (2018), Transition Economies, Routledge, London, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315736747.

[7] Government of Armenia (2021), National Action Program of Adaptation to Climate Change and The List of Measures for 2021-2025, Government of Armenia, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/NAP_Armenia.pdf.

[6] Government of Georgia (2021), Georgia’s 2030 Climate Change Strategy (Mitigation), Government of Georgia, https://mepa.gov.ge/En/Files/ViewFile/50123.

[13] Government of Georgia (2021), Law of Georgia on Environmental Liability, Government of Georgia, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/download/5109151/0/en/pdf.

[5] Government of Tajikistan (2021), “President of the Republic of Tajikistan, Emomali Rahmon, proposed to declare 2022-2026 ’Years of industrial development’ and to adopt a “green economy development strategy”, Embassy of the Republic of Tajikistan in the Federal Republic of Germany, https://mfa.tj/en/berlin.

[8] Green Central Asia (2021), Regional Action Plan, Green Central Asia, http://greencentralasia.org/en/doc/1649309482/1636624593.

[33] Kampel, E. and O. Gassan-Zade (2021), NDC Preparation and Implementation in EaP Countries: Comparative Analysis of the First and the Updated NDCs in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, EU/UNDP EU4Climate Project, United Nations Development Programme, New York, https://www.undp.org/eurasia/publications/ndc-preparation-and-implementation-eap-countries.

[4] Kazinform (2018), Conception of Kazakhstan on Transition to Green Economy, Strategy 2050 Review and Analytical Portal, Kazinform, https://strategy2050.kz/en/news/1211/.

[32] Liu, W., L. Liu and J. Gao (2020), “Adapting to climate change: Gaps and strategies for Central Asia”, Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, Vol. 25/8, pp. 1439-1459, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-020-09929-y.

[21] NBG (n.d.), “Sustainable Finance”, webpage, https://nbg.gov.ge/en/page/sustainable-finance (accessed on 2 April 2022).

[18] Neuweg, I. and K. Michalak (forthcoming), The environmental effects of COVID-19 related recovery measures in the EECCA region, OECD, Paris.

[24] OECD (2022), “Green Growth Indicators”, OECD.stats, (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=GREEN_GROWTH (accessed on 13 September 2022).

[34] OECD (2022), “OECD-Ukraine Memorandum of Understanding”, webpage, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/countries/ukraine/oecd-ukrainememorandumofunderstanding.htm (accessed on 3 September 2022).

[30] OECD (2021), “Aligning short-term recovery measures with longer-term climate and environmental objectives in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia”, Discussion Paper, GREEN Action Task Force, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/ENVEPOCEAP(2021)4-GreenRecoveryEECCA.pdf.

[2] OECD (2021), Charting the path towards implementing the Paris Agreement: Progress in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, GREEN Task Force, OECD, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1114_1114345-c5pt3a5pu6&title=Charting-the-path-towards-implementing-the-Paris-Agreement.

[19] OECD (2021), “COVID-19 and greening the economies of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/40f4d34f-en.

[16] OECD (2021), Developing a Water Policy Outlook for Georgia, the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/512a52aa-en.

[39] OECD (2021), Energy-water-land use nexus in Central Asia: Pfull description of the project for experts, https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/nexus_project_summaryfull-final (accessed on 20 August 2022).

[29] OECD (2021), Sustainable Infrastructure for Low-carbon Development in the EU Eastern Partnership: Hotspot Analysis and Needs Assessment, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c1b2b68d-en.

[40] OECD (2020), “Nature-based solutions for adapting to water-related climate risks”, OECD Environment Policy Papers, No. 21, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2257873d-en.

[12] OECD (2019), Extended Producer Responsibility in Kazakhstan: Review and recommendations, https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/EPR_KAZ_report_Web.pdf.

[28] OECD (2019), Sustainable Infrastructure for Low-Carbon Development in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Hotspot Analysis and Needs Assessment, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d1aa6ae9-en.

[35] OECD (2018), Energy Subsidy Reform in the Republic of Moldova: Energy Affordability, Fiscal and Environmental Impacts, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292833-en.

[37] OECD (2018), Mobilising Finance for Climate Action in Georgia, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264289727-en.

[25] OECD (2018), Mobilising private finance for green growth: Role of governments, financial institutions and development partners, GREEN Action Task Force, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=env/epoc/eap/(2018)2&doclanguage=en.

[36] OECD (n.d.), “Economics and Policies for Biodiversity: OECD’s Response”, webpage, https://www.oecd.org/env/resources/biodiversity/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

[23] OECD (forthcoming), Greening debt capital markets in the EU’s EaP countries and Kazakhstan: The role for Green Bonds, OECD, Paris.

[20] SBN (2020), Country Profile Kyrgyz Republic: Addendum to the SBN Report Necessary Ambition: How Low-Income Countries Are Adopting Sustainable Finance to Address Poverty, Climate Change, and Other Urgent Challenges, Sustainable Banking Network, International Finance Corporation, Washington, DC, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/c4ed68a8-ff90-411a-9195-b1e761ee861a/SBN_Necessary_Ambition_Country_Profile_Kyrgyz_Republic_2020.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=nXqmuty.

[14] UNECE (2022), Environmental Performance Reviews Publications, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Geneva, https://unece.org/publications/environmental-performance-reviews.

[11] UNECE (2020), 3rd Environmental Performance Review of Uzbekistan, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Geneva, https://unece.org/info/Environment-Policy/Environmental-Performance-Reviews/pub/2183.

[3] UNECE (2016), Report of the Eighth Environment for Europe Ministerial Conference “Declaration: ’Greener, cleaner, smarter!’”, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Geneva, https://unece.org/DAM/env/documents/2016/ece/ece.batumi.conf.2016.2.add.1.e.pdf.

[26] World Bank (2022), Europe and Central Asia Economic Update: War in the Region, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eca/publication/europe-and-central-asia-economic-update.

Notes

← 1. EECCA countries include Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Republic of Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

← 2. The Eastern Europe countries include Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine and the Caucasus countries include Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia.

← 3. Armenia and the European Union signed in 2017 the EU-Armenia Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement.

← 4. Nature-based solutions (NbS) are “measures that protect, sustainably manage or restore natural capital, with the goal of maintaining or enhancing ecosystem services to address a variety of social, environmental and economic challenges” (OECD, 2020[40]).