The reader’s guide provides information on the OECD’s in-depth analysis of the labour market relevance and outcomes of higher education. It presents the methodology used in the Mexico review and concludes with a brief overview of the chapters in this report.

Higher Education in Mexico

Reader’s guide

Abstract

Across the OECD, one of the main objectives of higher education systems is to provide graduates with the skills needed to succeed in the labour market. The skills developed in higher education, both discipline-specific and transversal (Figure 1), can improve the economic well-being of individuals and support the productivity, innovation and economic growth of nations.

The credentials that graduates receive from higher education institutions upon the successful completion of their studies are crucial in signalling to employers that they have the capacity, interest, relevant technical and professional skills, and knowledge to do a job successfully within a specific domain. In fact, a higher education qualification is no longer simply an advantage to gaining access to the field, but an essential requirement for many occupations.

As a result, when higher education functions well, it serves to promote strong labour market outcomes for graduates in the form of higher earnings, greater labour market security, and better working conditions. These labour market outcomes are also key factors that shape an individual’s overall well-being, as shown by the OECD’s Better Life Initiative, the OECD Job Quality Framework, and research in the fields of psychology, economics and sociology. People with higher levels of education are more likely to be civically engaged, more likely to have better health outcomes, and less likely to be involved in criminal activity. Overall, they are more likely to be satisfied with their lives.

However, not all higher education graduates are doing well in the labour market. The distribution of graduate earnings premiums across OECD countries indicates that a significant minority of graduates are not achieving the labour market success that might be expected of them. In particular, some higher education graduates have trouble transitioning to the labour market, while others are unable to find jobs that correspond to their academic training and qualifications. Higher education graduates are also discovering changing skills demands brought about by broad-based trends like globalisation, technological change and rapid population ageing. This brings into question both the relevance and the quality of the skills developed in higher education.

Weaker-than-expected outcomes across the OECD raise multiple concerns. They are a disappointment for individual graduates and their families, who have invested in higher education and expect a good return on their investment in the form of well-paying jobs. Weak returns are also a concern for governments, which play a major role in funding higher education systems. Policy makers expect higher education to produce skills that will foster productivity and innovation, meet the needs of employers and raise the overall quality of life of citizens.

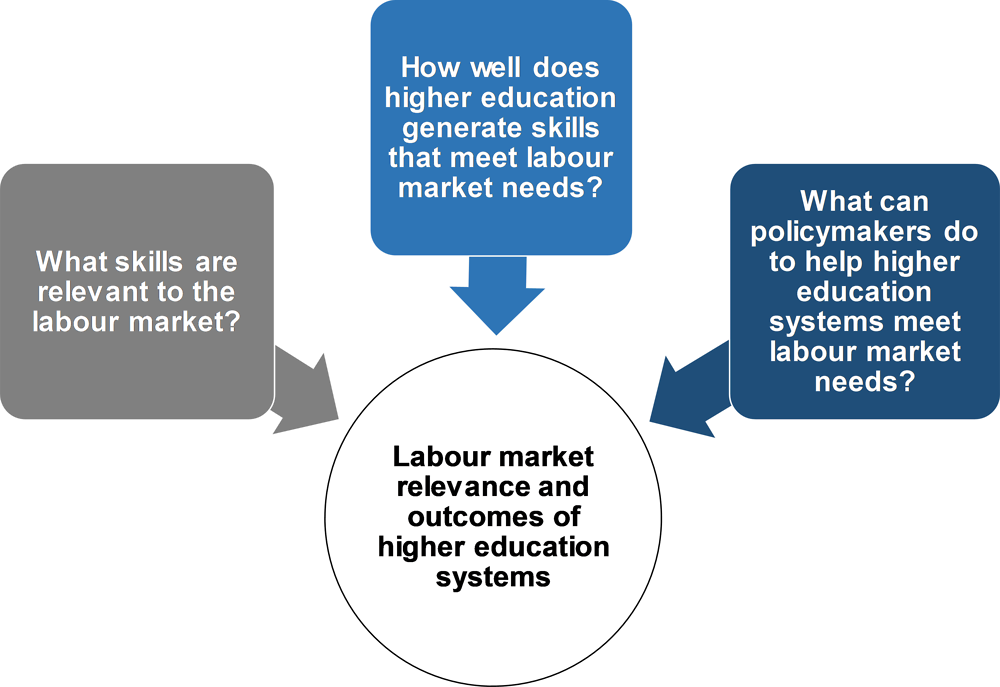

It is with these concerns in mind that the OECD launched the in-depth analysis of the labour market relevance and outcomes of higher education. This project aims to help countries improve the labour market relevance and outcomes of their higher education systems through a better understanding of the links between the knowledge and skills developed in higher education and graduate outcomes; and how policies and practices can stimulate and enhance the development of more labour market relevant knowledge and skills. Three key questions guide the analysis to help countries identify what they can do to ensure that higher education graduates develop the skills needed for good labour market outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. In-depth analysis of the labour market relevance and outcomes of higher education: key questions

This report presents the analysis of the current level of alignment of higher education in Mexico with the labour market, and provides recommendations for improvement. In January-February 2018, an OECD review team visited Mexico City, Monterrey and Tuxtla Gutiérrez. The review team conducted workshops and interviews with a wide range of stakeholders to identify and discuss current practices and policies in the higher education system to support labour market relevance and outcomes. During the visit, the OECD review team held workshops in four higher education institutions with the participation of students, graduates, academic staff, non-academic staff and employers. In addition, the review team undertook face-to-face interviews with employers, trade union representatives, rectors, and representatives from private, public and direct-provision higher education institutions and associations. Telephone interviews were also conducted throughout 2018 to gather further opinions, experiences and good practices from key stakeholders. In March and April 2018, an online survey on practices collected the views of over 6 500 higher education students, academic staff, non-academic staff and rectors in Mexico.

The analysis of the labour market relevance and outcomes of Mexico’s higher education system:

Identifies the knowledge and skills needed in the Mexican labour market, taking into account other factors that are beyond the realm of the higher education sector (Chapter 2), and the structure and governance of the higher education sector (Chapter 3).

Assesses how well the Mexican higher education system is developing these labour market relevant skills by looking at graduate skills and labour market outcomes (Chapter 4).

Identifies approaches in higher education in Mexico that facilitate or hinder the development of labour market relevant skills (Chapter 5).

Explores and assesses the effectiveness of the policy levers that Mexico’s policy makers are using to influence the development of labour market relevant skills in higher education and good labour market outcomes for graduates (Chapter 6).

Box 1. What skills matter?

To succeed in the labour market, individuals need a mix of knowledge and skills. The OECD Skills Strategy defines skills as “the bundle of knowledge, attributes, and capacities that enable individuals to successfully and consistently perform an activity or task, and that can be built up and extended through learning” (OECD, 2012[3]). This project focuses on the following broad sets of skills that are important for good labour market outcomes.

Discipline-specific knowledge and skills

Good technical, professional and discipline-specific knowledge and skills reflect a solid theoretical and practical understanding of subject matter. At the higher education level, this is typically codified by academic disciplines. Skills are not developed solely to meet labour market needs, and some disciplines develop technical skills that do not have an obvious labour market match. However, many technical and professional qualifications send a signal to employers that a graduate may have the skills, interest and capacity required to engage in specific types of work; and a concrete set of technical and professional skills is an essential requirement for many jobs (OECD, 2014[4]). Employers often use these qualifications as a first lens to screen individuals for jobs (Montt, 2015[5]). At the level of the overall labour market, an adequate supply and mix of these skills is an important precondition for good economic growth.

Transversal skills

Graduates need to apply their knowledge in uncertain and evolving circumstances. For this, they will need a broad range of skills, including cognitive and metacognitive skills (e.g. critical thinking, creative thinking, learning to learn and self-regulation); social and emotional skills (e.g. empathy, self-efficacy and collaboration); and practical and physical skills (e.g. processing new information and using communication technology devices). These are transversal skills, which graduates can readily take from one employment context to another.

Good generic cognitive and information processing skills involve the understanding, interpretation, analysis and communication of complex information, and the ability to apply this information to situations in everyday life (OECD, 2015[6]). These are the skills that people use in all kinds of work and support effective participation in social and economic life. They also help individuals adapt to a changing economy. Cognitive skills such as critical thinking support positive outcomes in the workplace by allowing individuals to proactively and effectively deal with non-routine challenges (OECD, 2015[6]). The ability to undertake analysis and synthesis is increasingly important for labour market success.

The social and emotional skills involved in achieving goals (perseverance, self-control and passion for goals), working with others (sociability, respect and caring) and managing emotions (self-esteem, optimism and confidence) are also very important in the world of work (OECD, 2015[6]); (OECD, 2015[7]). These skills are often hard to measure, but they allow individuals and companies to thrive, help build synergies within and across teams, and enable individuals to deal effectively with clients and others. There is evidence to suggest that employers are prioritising social and emotional skills more and more (AACU, 2013[8]).

These three primary skillsets are supported by metacognitive skills, or the ability of individuals to recognise their own knowledge and skills, attitudes and values, and unique way of learning. Metacognitive skills help individuals step back from what is simply presumed, apparent or accepted, and bring other perspectives to a situation.

The use of this broader range of knowledge and skills is mediated by attitudes and values such as adaptability; openness to others, new ideas and new experiences; curiosity; a global mind-set; proactivity; respect for others; trust; responsibility; integrity and equity.

References

[8] AACU (2013), It Takes More than a Major: Employer Priorities for College Learning and Student Success, Association of American Colleges and Universities, Hart Research Associates.

[5] Montt, G. (2015), “The causes and consequences of field-of-study mismatch: An analysis using PIAAC”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 167, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jrxm4dhv9r2-en.

[1] OECD (2019), The Future of Mexican Higher Education: Promoting Quality and Equity, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264309371-en.

[2] OECD (2017), Enhancing Higher Education System Performance. In-depth Analysis of the Labour Market Relevance and Outcomes of Higher Education Systems: Guidelines, http://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/LMRO%20Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2018).

[7] OECD (2015), OECD Skills Outlook 2015: Youth, Skills and Employability, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264234178-en.

[6] OECD (2015), Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en.

[4] OECD (2014), Skills beyond School: Synthesis Report, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264214682-en.

[3] OECD (2012), OECD Skills Strategy Towards an OECD Skills Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/education/47769000.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2018).