In April 2023, the OECD visited three schools in Greece to speak to students, English language teachers and school leaders about how 15-year-olds learn English. This chapter presents the key findings from these visits and broader evidence. First, it gives an overview of the educational and linguistic context of Greece. It then explores the ways in which students in Greece are exposed to English outside school, including their extensive participation in private, non-formal language education. Next, the chapter provides insights from students and their educators into how English is taught and learnt in schools and the resources available to them, including digital technologies and textbooks. The findings include their perspectives on the strengths and challenges of teaching or learning English in schools in Greece, and ideas for improvements.

How 15-Year-Olds Learn English

4. How 15-year-olds learn English in Greece

Abstract

A snapshot of learning English as a 15-year-old in Greece

Students in Greece have a very clear idea of why they learn English and how it will be useful to them in the future, including for employment, education, and cultural or social reasons. Teachers believe that this strong sense of relevance helps motivate students to do well in English.

English has a prominent role in the Greek national curriculum and students must study it throughout compulsory and upper secondary education. At the same time, many students typically study English in private, non-formal education from a young age. Language certification examinations, which are seen as crucial for life beyond school in Greece, are a significant driver of this.

English teachers in Greece are attracted to the profession by the wide variety of job opportunities. Those working in public school education recognise several favourable working conditions relative to teaching English in other contexts.

English lessons in Greek upper secondary schools typically follow the official textbook but different teachers appear to prioritise different skills and content. Teachers try to supplement the textbook material where possible, particularly through digital technologies and to better meet students’ different needs. However, teachers feel that large mixed-ability classes, a lack of curricular time and (digital) resource challenges create ongoing difficulties.

Learning languages in Greece

People in Greece are increasingly exposed to languages other than Greek

Greek is the official language of Greece and is used across the entire territory and at all levels of education. The Muslim minority, which is of Turkish, Pomak and Roma origin, resides in the north-east of the country and accounts for approximately 1% of the total population of around 10.5 million. Minority schools operate for these students, with Turkish and Greek as the languages of instruction.

In 2021, 13% of Greece’s population was foreign-born. By far the largest share of foreign nationals come from neighbouring Albania although there are also large shares from Georgia and the Russian Federation (OECD, 2022[1]). Since 2015, Greece has experienced a considerable increase in the number of incoming refugees, some applying for asylum and others travelling further north into Europe. In 2022, over 86 600 refugees and asylum-seekers arrived in Greece, double the number in 2021 and mostly from Afghanistan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Ukraine (UNHCR, 2023[2]). In the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2022, 8% of 15-year-olds reported mainly speaking a language other than Greek at home, compared to the OECD average of 11% (OECD, 2023[3]).

People in Greece are also exposed to speakers of other languages through tourism and tertiary education. Tourism is a key driver of the Greek economy: in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, Greece received 34 million international arrivals, compared to a total population of around 10.5 million. The largest shares came from France, Germany and the United Kingdom. In terms of outbound tourism, inhabitants made 7.8 million international departures from Greece (OECD, 2022[4]). In 2021, 23 000 international or foreign students were studying in tertiary education in Greece, around 3% of the total student cohort. The largest shares came from neighbouring countries or Asia. Meanwhile, around 5% of domestic students chose to study abroad; the most popular destinations were France, Germany and the United States (OECD, 2023[5]).

English language competence is a highly desired skill on the Greek job market. A recent study of online job vacancies in Europe in 2021 revealed that around half (51%) of positions advertised in Greece had either an explicit or implicit demand for English language skills, compared to one-third on average across OECD countries. In some regions, the share exceeded 90% (Marconi, Vergolini and Borgonovi, 2023[6]).

English also enters lives through culture. Dubbing is not commonplace in Greece and films or television programmes are typically shown in the original language with Greek subtitles. Meanwhile, estimates indicate that 53% of websites produce content in English, compared to just 0.5% for Greek, meaning that Internet users are likely to regularly encounter English content (Web Technology Surveys, 2023[7]).

All students in Greece study English from an early age and throughout their schooling

Compulsory education in Greece begins in pre-primary school at age 4 and ends at age 14-15, at which point students complete lower secondary school and, if they choose to continue their education, are tracked into general or vocational pathways. Typically, 15-year-olds in Greece do transition to upper secondary education: in 2021, 87% were enrolled in upper secondary education, 8% in lower secondary and only 5% in neither (OECD, 2023[5]).

At upper secondary level, 95% of schools are public and 5% are private. Around 3% of all upper secondary schools are Experimental or Model schools. These schools aim to serve as centres of excellence and innovation to contribute to spreading higher quality approaches to education across the school network. They can offer either general or vocational education programmes and have been increasing in number in recent years. Model schools are academically selective, typically based on students’ performance in Greek language and mathematics.

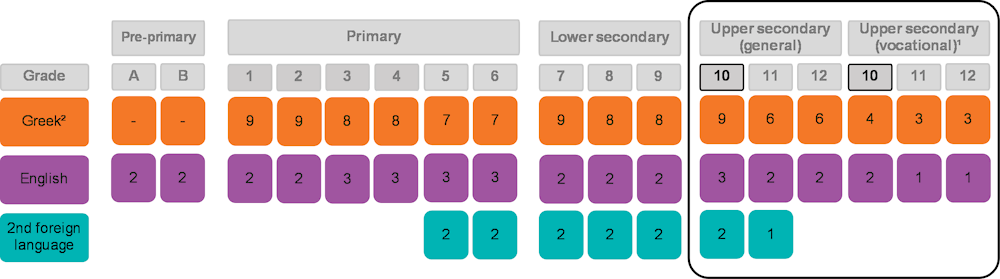

English is a mandatory subject in Greece. As of 2021, students begin learning English in pre-primary education (age 4) through creative, oral activities, and this continues at the first two grades of primary education. Formal instruction begins in Grade 3 (age 8) with the introduction of the Integrated Foreign Languages Curriculum for Primary and Lower Secondary Schools (2016) and continues up to the end of upper secondary education (age 18) (Figure 4.1). This means that, among European countries, Greece now has one of the longest durations for learning a foreign language at 14 years (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2023[8]).

Figure 4.1. Typical distribution of lesson hours for languages in Greece in 2023

1. In upper secondary vocational education, the hours shown are those for compulsory (general) English courses; in Grades 11 and 12, students can choose to study programmes that may include additional hours for (vocational) English and for a second foreign language.

2. The hours for Greek include those for Modern Greek language and literature and Ancient Greek language and literature.

Note: The modal grade and education level for 15-year-olds are outlined in black.

Source: European Commission (2023[9]); national information reported to the OECD.

The curriculum is aligned with the competence levels of the Common European Framework Reference (CEFR), with students expected to reach B1/B2 by the end of lower secondary education. A new Common Curriculum for Foreign Languages for general upper secondary schools has recently been introduced (2023), also aligned with the CEFR, and students are expected to reach C1 by the end of general upper secondary education; this will be implemented in 2024/25. Greece, along with Iceland, is thus one of only two countries in Europe that has set expected attainment at advanced or proficient user level (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2023[8]). There is no official proficiency level set for vocational upper secondary education, although it is generally expected that students reach a lower level than those in general upper secondary education.

In upper secondary general education in Greece students’ achievement in English is typically1 assessed partly through school-level written examinations at the end of the academic year and partly according to their overall progress during the school year. Half of the items in the examinations are drawn from the National Test Item Bank with Graded Difficulty for Secondary Education (hereinafter the “Item Bank”) and assess reading skills and vocabulary; the other half are developed by the teacher and assess writing skills and grammar.

At the end of upper secondary education, those students wishing to transition to tertiary education must complete the Panhellenic examination. Depending on their chosen field of study and the requirements of their selected tertiary programme, students take the English language examination, which assesses reading skills, language awareness (lexical, grammatical and discourse competence) and writing skills (OECD, 2023[10]). Greece has also developed a state certificate of language proficiency; however, this is not offered via the formal education system. There are, therefore, no national data on students’ English language proficiency.

The case study visit to Greece

In April 2023, the OECD Secretariat and two Greek national experts visited three schools in Greece. These schools were selected for their diverse characteristics which include different school types (general, vocational and Model), locations (urban and semi-urban) and sizes (Table 4.1). Nevertheless, all three schools are in Athens and the surrounding area and are not representative of schools across the country. The case study findings should, therefore, be interpreted as illustrating the experiences of some students and teachers in Greece as opposed to being generalised nationally.

The findings presented in the remainder of this chapter are based on interviews with school leaders, English teachers and 15-year-old students in the three case study schools; lesson observations; student activity logs; and short surveys administered to interviewees. In addition, the analysis is informed by a country background report prepared by a national expert from Greece and a background interview with representatives from the Panhellenic Association of State School Teachers of English. For further information on the methodology, see Chapter 1.

Table 4.1. Key characteristics of the case study schools in Greece

|

School A |

School B |

School C |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Location |

Semi-urban |

Urban |

Urban |

|

|

Education level |

Upper secondary |

Upper secondary |

Upper secondary |

|

|

School type |

Public, general high school (morning) |

Public, general Model1 school (morning) |

Public, vocational high school (morning) |

|

|

Student cohort |

In whole school |

163 |

480 |

287 |

|

In modal grade for 15-year-olds |

52 |

162 |

57 |

|

|

% of socio-economically disadvantaged |

5% |

|||

|

% whose first language is not Greek |

13.5% |

4% |

||

|

Teacher cohort |

In whole school |

21 |

46 |

51 |

|

Teaching English |

1 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Interviewees |

Vice principal One English teacher Five 15-year-olds |

Vice principal Three English teachers Five 15-year-olds |

School principal Two English teachers Six 15-year-olds |

|

1. Model schools aim to serve as centres of excellence and innovation to contribute to spreading higher quality approaches to education across the school network. They are academically selective and have somewhat greater autonomy than other schools.

Source: Based on information reported to the case study team by schools.

How do 15-year-olds in Greece experience English outside school?

Students in Greece often use English outside school and teachers believe this increases language proficiency

The students interviewed in Greece reported frequently using English in various activities outside school. All study or have studied English in non-school settings (see below). They also watch films, series and videos in English, both with and without subtitles. They read books in English; listen to English language podcasts or music; and use English when browsing the Internet, gaming or using social media.

While all the students described being surrounded by English outside school, some explained that they actively choose English language options, either for perceived quality or cultural interest. For example, when browsing the Internet, several students use English because of the greater quantity of information available. One student felt that books, podcasts and videos in English are of better quality and more interesting than those in Greek. Another described being a fan of English football and watching matches with English language commentary. Another student chooses to read English language books in their original form as opposed to the Greek translations, finding this more “realistic”. In contrast, one teacher felt that fewer students listen to English language music because Greek music remains very popular.

When I look for something on the Internet, I look for it in English because it’s easier for me and because I find more information in English. [Student, School A]

I prefer podcasts and videos in English because I find they are better quality. Greek videos are rubbish. I can learn a lot of things watching English or American videos. [Student, School B]

The case study students’ interactions with English outside school are not limited to receptive skills (reading and listening) but also include using productive skills (speaking and writing). Several students reported writing messages and emails in English or speaking English with family members or friends who live abroad and do not speak Greek. Those who play video games communicate with other players in English. Students also mentioned using English when interacting with tourists. A school leader explained that there are many opportunities for young people to speak English with foreigners because tourism is so important in Greece. Finally, two students described having attended summer camps in Greece where some activities were in English or where the common language between students was English.

Several of the students reported using English with their Greek friends or family members in text messages, on social media and between lessons at school. For one teacher, this translanguaging was linked to the fact that many English words or phrases have entered the Greek language in recent years; another felt that the students just enjoy this playful use of language.

Also, when I text some Greek friends or talk to them on the phone, I often use English. [Student, School A]

The interesting thing is that they speak in English with each other or with their English teachers during the breaks…It’s more enjoyable for them. They have even started making jokes sometimes. [Teacher, School C]

Nearly all the teachers interviewed felt that students’ exposure to English outside school helps them improve their language skills. For many, the impact is direct: anything students do outside school in English is helpful because it habituates them to the language. However, one teacher and one school leader felt that the relationship is indirect: exposure to English beyond school helps students understand the relevance of English to their lives, therefore motivating them to improve.

Whatever helps students come into direct contact with English helps them to learn it better and faster and generally improve their level. [Teacher, School A]

Learn English here and then you’ll be able to talk online when you play with your friends. So, they have a reason to actually learn because this helps them when, for example, they watch TikTok videos or Instagram stories; they’re all in English and they want to participate. [Teacher, School B]

Nevertheless, one teacher highlighted that there is also a negative impact: in some cases, frequent use of English outside formal education settings can give students a misplaced sense of their own competence.

They often claim that they already know something but when I actually teach it or ask them about it, they don’t really know it. [Teacher, School A]

Students have a clear understanding of how English will benefit them in their futures

The students interviewed in Greece consider English language proficiency to be highly important for future success. Many were able to give concrete examples of how they would use English later in life. This included needing English when studying abroad or to access academic material for university studies in Greece. Others explained that they would need English to communicate and interact with the many foreigners travelling to Greece or when travelling abroad. Finally, some had a clear idea of their future career and felt English would be useful. This included working in tourism and other service sectors, or in digital technology and aviation.

In the beginning [learning English] was kind of boring, it was like school, but now I find it very important and I want to learn. Now I find it very interesting…and so it’s part of my life. [Student, School C]

One school leader explained that this high regard for English extends to all students so that even those who do not typically perform well in other subjects or enjoy school, are often motivated to do well in English. This sentiment was echoed by a teacher in another school. For the school leader in the vocational school, high regard for English is due to the fact that it is considered essential for finding a job in Greece.

Generally, students view English as very important not only for higher education but for other purposes too. There are students who are not good at any other subjects but they are really good at English, they speak it very well. [School leader, School A]

If you don’t know English you are considered as if you were illiterate. In practice, there is no way anyone can get a job [or] be employed if they don’t know English. It’s like a basic qualification. [School leader, School C]

The importance with which students view English is shared more widely across Greek society. According to all interviewees, Greek parents highly value proficiency in English, principally with a view towards higher education and employment. Several students said their parents encourage them to learn English because they consider it to be indispensable, regardless of whether they speak it themselves or not.

[Parents] strongly believe that English is an important asset and qualification for the rest of [students’] lives. [School leader, School A]

In my case, my father does not speak English but he believes it is absolutely necessary. It’s like schooling, it’s mandatory, like you have to go to school and you also have to learn English. [Student, School C]

Private language education is widespread in Greece and is considered essential

It is common for students of all ages in Greece to attend private, non-formal education, particularly for English (Box 4.1.). All the students interviewed for the case study had studied English outside school, mostly in private language centres. Many started attending these schools in primary education and continued doing so. A school leader explained that students from almost all backgrounds participate in private language education in Greece, not just those with a socio-economically advantaged background.

Box 4.1. The role of private, non-formal education in English language learning in Greece

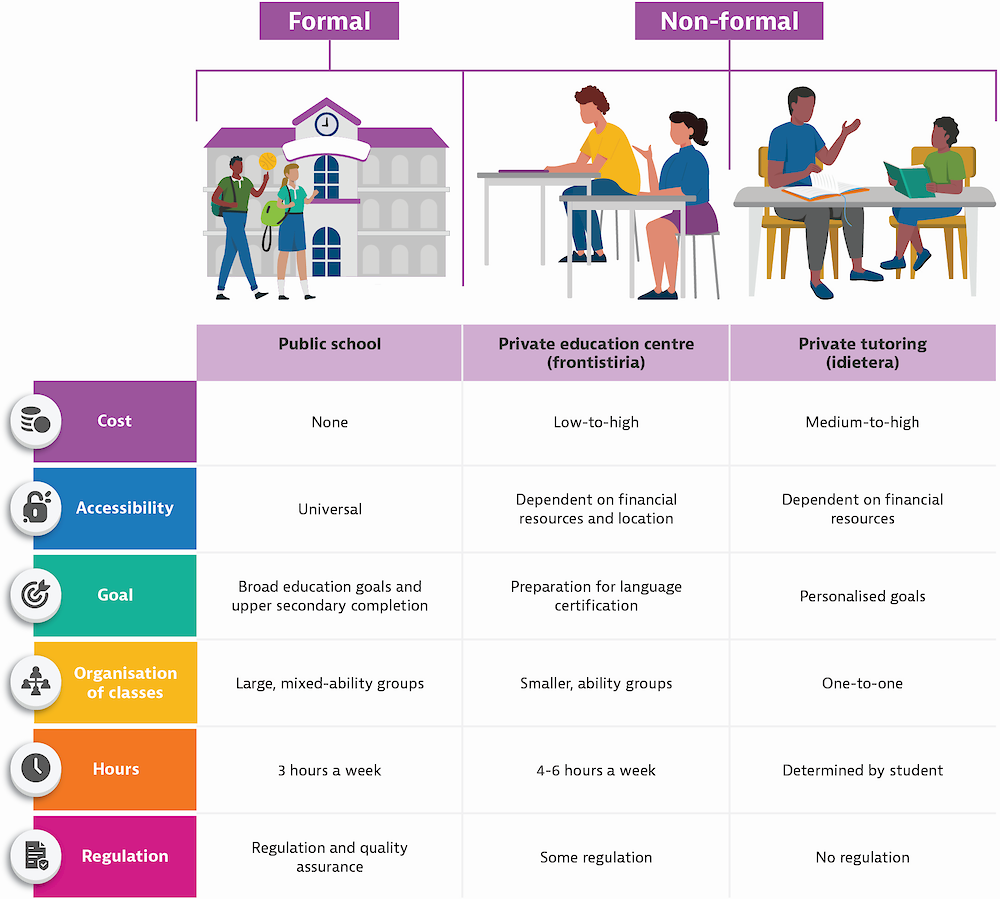

Students in Greece commonly attend afternoon and evening private education centres (frontistiria) or receive one-on-one tutoring (idietera) for foreign languages, particularly English. This is typically from early primary education onwards and mainly focuses on preparing students for language certification.

The frontistiria range from small, neighbourhood-based centres to large regional, national or even international franchised networks. They offer classroom-based education in small groups although low-cost providers may have larger groups. Frontistiria are licensed by the Ministry of Education, Religious Affairs and Sports and inspected on opening. In contrast, the idietera are unregulated and, in some cases, operate in the shadow economy. There is no quality control process for either.

Attendance is widespread. In 2016, data from the Hellenic Statistical Authority revealed that around 1 million students in primary and secondary education attended lessons in frontistiria or received private tutoring for foreign languages. It was estimated that Greek families spend EUR 600 million every year on related tuition fees and books and another EUR 15 million on examination fees.

Although this type of non-formal education exists less “in the shadows” in Greece than in other countries, there are important implications for quality and equity. Research has found that the widespread existence of private language centres creates a demoralising effect on the public education system. In addition, despite being widespread, participation is not universal: students from the most socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds, immigrant and refugee backgrounds and those living in very rural areas are unable to participate at the same rate as many of their peers.

Sources: OECD (2018[11]); Liakos (2016[12]).

There are two types of private, non-formal English language education in Greece: attending lessons in private language centres or receiving private tutoring. Each has specific characteristics which differentiates it from the other and from typical English lessons in formal school education (Figure 4.2). Most of the students interviewed attend or had attended private language centres but a small number receive private tutoring at home either as their level has become more advanced (i.e. preparing for C1 or C2 certification) or because they prefer the personalisation or flexibility of one-on-one tutoring.

I realised that [the foreign language centre] was a bit like school, that even this private school was not adapted to my individual needs. So then I decided to get private tutoring and I am preparing my proficiency exam with a private tutor and I find this a much better option because all the time is for me. The teacher is dedicated to me and I can practice my oral skills for a longer time because the lesson is only for me. The lesson is adapted to my needs. [Student, School B]

Figure 4.2. Formal and non-formal learning contexts for studying English in Greece

Note: The information presented in the figure refers to typical characteristics of studying English in different learning contexts in Greece; certain schools, frontistiria and idietera will have different characteristics.

The biggest driver of private English language education in Greece is certification. While the public school system does not offer language certification, private language centres or tutors specifically prepare students to take internationally recognised examinations, or the state certificate of language proficiency. Among the interviewees, certification is seen almost as a rite of passage. A school leader explained that parents aim to help their children learn English at the highest level possible and obtain a certificate before they enter upper secondary school, at which point the focus turns to preparing for entry to university.

Families think that it’s important that when their children get here, they will have “finished” learning English, they will have completed this “obligation”. This is what I did with my own kids. [School leader, School B]

However, such attitudes also come from the students themselves. Most of the interviewed students see the B2-level certificate as an essential entry ticket to tertiary education and employment. For others, a certificate at C1 or even C2 level is seen as necessary.

If you are looking for a job and you tell them that you know English, that doesn’t mean anything for them, you need to show them your certificate. Otherwise, they might think that you just claim that you know it, that you are lying. Anyone can claim that, so it’s like proof. I couldn’t claim that I know English if I wasn’t able to get the certificate. [Student, School B]

Among participants, attitudes towards the prevalence of private language education and its impact on schooling were mixed. One teacher explained that the content, aims and approaches of teaching in each context are very distinct; where there is crossover, for example in grammar and vocabulary teaching, school lessons help students revise material learnt outside school. Some students agreed with the latter point, reporting learning most of their English in private education with school helping to consolidate it.

For me, the school supplemented the foreign language centre and made me implement what I had learnt there. [Student, School B]

Everyone takes for granted that students’ learning happens outside of school. Teachers do their best. But the rule is that students learn English outside of school. [Student, School A]

However, other interviewees found the prominence of private education problematic. First, some teachers identified it as the key driver behind the wide gaps in student abilities in classes, particularly in the case of children whose families lack the financial means to put them in private education. One of the school leaders felt the system is indicative of mistrust between parents and the education system; one teacher questioned the integrity of the certification process.

[Parents] do not think that the school can offer their children the best possible education…This situation hurts us. It’s really sad. [School leader, School A]

We have [many] different B2 certificates [that are taken] in Greece today and some are rubbish… the kids who have them do not know English. Simple as that. They don’t! They have a B2 certificate and they cannot communicate. [Teacher, School B]

Some students wished that the school system was able to offer them everything they need so that they did not have to attend private language education. For example, some want the school to prepare them for language certification. Others want teaching and learning in school to be more like that in private language education whether that be in terms of the variety and quality of learning materials, the higher number of teaching hours, or the greater perceived effort to tailor the teaching to students’ needs.

Public schools should offer certificates at the end of upper secondary education so that students wouldn’t need to follow private education and pay to get their certificates. Schools should prepare students to obtain the certificate. [Student, School A]

How do 15-year-olds in Greece experience English in schools and classrooms?

English has an increasingly important place in the curriculum but students want more

Greece has implemented several reforms in recent years which signal the importance of English in the school curriculum, such as lowering the starting age, increasing the number of hours in primary school and becoming compulsory across upper secondary education. Some of the 15-year-olds interviewed for this case study, who started learning English in Grade 3 (age 8), expressed that they wished they had also started in pre-primary school – or even earlier.

If I had started at age 4 it would be much easier to learn later. If we learnt English like we learn Greek, it would be as easy to learn English as it is to learn Greek. [Student, School C]

If our parents could teach us English from a very young age, if they could speak to me [in English] when I was a baby, I would become bilingual and it would be extremely easy for me to speak English fluently. [Student, School C]

Nevertheless, participants’ views about the extent to which English is valued in school education in Greece were mixed. School leaders felt the subject is valued by the school community but gave different reasons. One cited the fact that English is now mandatory in upper secondary education and that there is continuity from the earliest age whereas, for other foreign languages, students may be forced to change language when transitioning from one school to another. Another felt that their school’s engagement in international exchange programmes meant teachers of all subjects are encouraged to speak English and interact with international visitors. The school leader of the vocational school explained that students in all pathways have dedicated hours for practical English related to their specialisation. This gives English a unique position as it has a direct and explicit connection to other subjects and because the school then offers something that the private language centres do not.

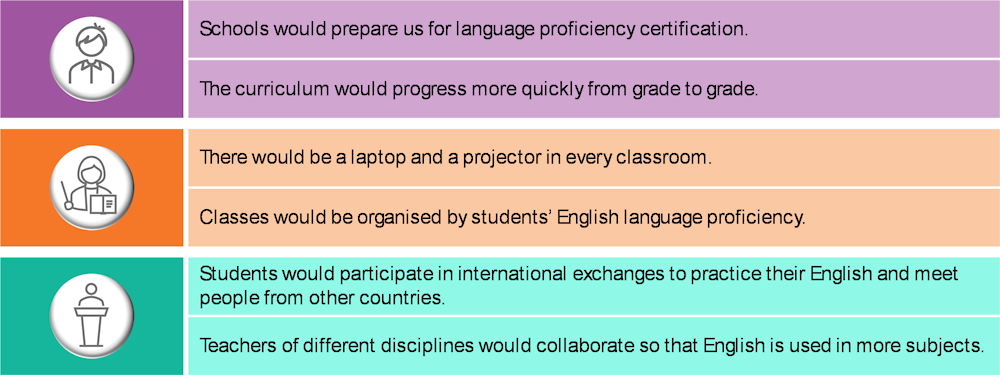

Nevertheless, students and some teachers felt even more could be done to recognise the importance of English. These ideas were part of broader suggestions about how English learning could be improved in Greece (Figure 4.3). Some students felt teachers do not value English as much as other subjects, particularly because they know students get their certificates through private language education. Others saw the fact that so many students study English outside school as symptomatic of it not having a prominent enough place in the curriculum. For several, increasing the curriculum hours for English would help improve the quality of English learning at school and enable schools to “compete” with the frontistiria.

It is not considered as an important subject, like physics or mathematics, so there is little motivation to achieve more. The teachers know that some students have their certificates, so there is no further motivation. [Student, School A]

We have three hours of English in the curriculum, which is not enough to make students like the language and learn the language. [Student, School C]

Figure 4.3. Teaching and learning English in Greek schools in a dream world

Note: The figure presents a selection of combined statements in response to the question: “In a dream world where everything is possible, what would you change about the way you teach/learn English at school?”.

Source: Based on case study research conducted in three schools in Greece.

In comparison to other countries in Europe, the number of hours dedicated to foreign language instruction in primary education in Greece is high. However, in secondary education, Greece has among the lowest number of hours. This is reflective of the fact that Greek instruction hours for foreign languages follow an inverse pattern to that in other countries where more hours are typically allocated in lower and upper secondary education than in primary education (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2023[8]).

The desire for more hours of English lessons is likely driven by the high value placed on English in Greek society but also because students seem to enjoy their English lessons in comparison to other subjects. Reasons given include finding it easy, important or more relevant; enjoying the opportunities it offers to learn about the world; and seeing English lessons as more fun, interactive or engaging than in other subjects.

I love learning English because it’s a different way of dealing with new things in my life. When learning a new language, it’s easier for me to learn new things, travel the world and communicate with [other people]. I love the language because it’s easy. [Student, School A]

We learn good things. It’s not like the rubbish we learn in other subjects. I know this sounds too harsh, but I mean it. For example, the unit on social media we had the other day which was extremely interesting and the things we learnt might prove very useful in our lives... We can also speak freely during the lesson without any restrictions. [Student, School B]

Teachers and students have mixed opinions regarding the four communicative skills

Participating teachers had different views about which of the four communicative skills (reading, listening, speaking and writing) they spend the most time on in lessons. One teacher said reading dominates, as reading and understanding texts is the basis of vocabulary work. The teacher added that although before reading a text there typically are some oral questions or conversation activities, only a few students participate in these. On the other hand, another teacher felt that speaking is the most practiced skill because the upper secondary curriculum focuses on the communicative approach and so texts are intended as a stimulus for conversation and debate. Across schools, students’ impressions also differed: a few agreed that listening and speaking dominate to the detriment, in their opinion, of vocabulary and grammar teaching while others felt that lessons would benefit from more interaction.

I agree that we don’t get a lot of new knowledge, for example new grammar, because there is this widespread idea in Greece that we learn outside school. [In school], we do more listening and speaking practice and the teachers speak English so that we get used to them. So, we have conversations and practice rather than get new knowledge. [Student, School B]

It could be more interactive. The teachers could teach us only in English. Not just copy the vocabulary in the textbook. As adults we will need to talk English in our work life. So it should focus more on learning how to speak English, not just learning words. We need to speak in English. Speaking is real. [Student, School A]

Responses also varied regarding which of the skills they find the most challenging to teach or learn. Two teachers felt that writing was the hardest skill, explaining that students adopt a translation approach (i.e. first thinking in Greek then translating into English), which makes the finished text unnatural, and that they lack motivation to write. A few students also identified writing because, along with speaking, it requires more effort than the receptive skills. One student disagreed, identifying writing as the easiest because it gives you time to think about accuracy and make corrections.

Several students and one of the teachers selected speaking as the most challenging skill. For the students, the effort required for speaking, the immediacy of it and the need to practice a lot to “master” it makes it difficult. A teacher explained that, because of the ways in which they engage with English outside school, students are less used to speaking English than reading or listening. However, this is not the same for everyone. Teachers in one school felt that their students are at ease with speaking and enjoy it. Some students from another school felt the same way.

Students are not used to speaking a lot in English. They don’t practice it a lot. Perhaps they feel shy to speak, they are afraid they will make mistakes. Maybe they don’t feel at ease to speak, maybe they lack confidence. [Teacher, School A]

English teachers and students feel that large, mixed-ability classes pose challenges

Students cannot be grouped by ability in upper secondary education in Greece. In the case study schools, teachers reported that mixed-ability English language classes can include proficiencies ranging from A1 to C2, although in the Model school, which has a selective admissions process, the range is more like B2 to C2. All participants acknowledged that the prevalence of private non-formal education intensifies this heterogeneity. The challenge may also be particularly intense in upper secondary education, as ability grouping exists in some lower secondary schools in Greece.

Participants identified a range of strategies used to address students’ different needs. Two school leaders explained that students who are underperforming in English and other subjects, and whose parents agree, can receive an official diagnosis to determine whether they can receive extra support at school from a specialist teacher or other specific measures. Beyond this, support is the teacher’s responsibility.

It is up to the English teacher in the classroom to divide the students by ability…and get them working in groups, so he differentiates the tasks according to their abilities, so that the stronger students are not bored and help the others. [School leader, School C]

In School B, teachers explained that they use the school’s virtual learning environment or emails to answer questions and provide more individualised support. Another teacher said that, if the student is motivated, they provide extra work. Teachers across schools described using differentiation approaches in class. This includes giving low-achieving students specific roles in group work, activities pitched at a lower level or more scaffolding for tasks (e.g. word banks or Greek translation). The teachers in one school emphasised the importance of creating a safe environment for these students and building their confidence.

We try to differentiate the tasks in a way that they can achieve something or if there’s group work, for example, maybe they are the ones who write the cards, since they cannot form questions or something like that. So you give them something to do to make them feel part of the group and you try to motivate them in a way to try and do the best they can and we always try to praise them. [Teacher, School B]

Personally, I differentiate my explanations, vary my rhythm of speech and my use of language so that everybody can understand. I use the Greek language although it’s something I don’t like doing in class but I have to. Otherwise, the child who doesn’t know English is going to feel left out and become unmotivated. [Teacher, School C]

While some students felt that their teachers are very supportive, patient and encouraging, others believe there is not enough time for teachers to respond adequately to all students’ needs in a lesson. These students compared school lessons to lessons in private language centres or private tutoring where they feel they get more support and are less stressed.

I find grammar very, very difficult so there are a lot of things I don’t understand, like “if” sentences. I ask questions but I almost never, most of the time, get the answers. [Student, School B]

In a private lesson, the teacher is there just for you and she or he can explain everything you ask for. [Student, School B]

Teachers also described efforts to support high-performing students in lessons by asking them to take on more responsibility by supporting other students, providing explanations or acting as the leader or spokesperson in group work. However, some teachers explained that they avoid giving them extra work as this can be perceived as being unfair.

We find ways to allow them to show that extra thing … but at the same time to learn that they have an obligation, in a way, towards the others. So, yes, you will be the person who speaks but, at the same time, you will help the others during the discussion. [Teacher, School B]

School leaders and teachers also mentioned extra-curricular opportunities as a way of supporting high-performing students. Activities offered by the case study schools include writing articles in English for the school newspaper, Erasmus programmes, international exchanges and school trips, or opportunities to act as guides for tourists or visiting students. Although these are not exclusively for high-performing students, interviewees recognised that it is generally the most proficient who participate. These activities typically take place on the personal initiative of the teachers who can, in return, receive points for appraisal or career progression (up to a maximum of three) but are rarely remunerated.

Despite these efforts, the teachers interviewed unanimously felt that they would like to do more to support students with different needs but felt powerless to do so. This was either because they perceived the gaps between students to be too wide or because structural factors out of their control prevent them from taking more impactful measures. For example, one teacher felt that lesson time is too short and classes are too big. Some students also identified these as obstacles to receiving more individualised support.

I would definitely like to do more, but the available time is very limited. The teaching period is 40 to 45 minutes which is not always enough for me to do all the things I want. Especially in a public school. There is always someone who arrives late and it takes time for students to get out the books and be ready to start the lesson. (Teacher, School A)

Many of the participants – school leaders, teachers and students – described wanting to be able to organise students by ability for English lessons. They saw this as a competitive advantage the private system has over public formal education. One of the students believed that ability grouping is the reason students learn more in private language centres. Two teachers explained that teaching in ability levels would also allow schools to prepare students for certification, eradicating the need for private institutions.

I want to get into a classroom and know that I am teaching “x” proficiency here. And then, next hour, I’m going somewhere where they don’t know the alphabet so I’m bringing pictures… But now we need to cater to everyone. In my dream world I would be teaching levels, not classes. [Teacher, School C]

What resources support English teaching and learning in schools in Greece?

Good job opportunities and working conditions motivate people to teach English

All the teachers interviewed in Greece have worked in various teaching contexts during their careers. This includes teaching English in formal (public and private) and non-formal education settings, as well as giving private tutoring. They have also taught students of different ages from kindergarten to adult education. Although the teachers recognised the differences between these contexts, they identified certain consistent elements, such as relationships with students, classroom management, and approaches to teaching vocabulary and grammar. They described the different experiences as enriching.

Participating teachers viewed the wealth of working contexts available to English teachers in Greece as a motivating factor for joining the profession. Nevertheless, all the teachers felt that working in the public education system is preferable, for a variety of reasons. First, working conditions are viewed more positively than in the private non-formal sector, where teachers mentioned not being paid on time, having to work many hours or being under a lot of pressure. In addition, some teachers described the teaching in private language centres as limiting due to the focus on preparing for certification.

In private institutions we were not always being paid on time or we didn’t get all the benefits. Sometimes you get paid under the table. But you may have advantages like smaller classes. [Teacher, School B]

Here I don’t have this pressure. I don’t have someone telling me, “You have to do this so that the kid gets the certificate”. Here I have more freedom to actually work on the language and actually use it for communication purposes, to know why they use it, why they learn English. [Teacher, School C]

As required in Greece, all the teachers had completed an English degree and a teaching qualification. Only two have permanent teacher status; the rest are contracted teachers working towards becoming permanent. They and their school leaders agreed that the restricted number of permanent teacher positions creates some instability, as it is common in many schools for positions to remain open at the beginning of the school year. There has been a considerable effort in recent years to appoint new permanent teachers, but the challenge remains (OECD, 2020[13]). In PISA 2022, 54% of principals in Greece reported that their school’s capacity to provide instruction is hindered at least to some extent by a lack of teaching staff compared to the OECD average of 47% (OECD, 2023[14]).

The use of digital technologies is inhibited by a lack of or inadequate resources

Digital technologies are used in English language teaching in each of the case study schools to varying degrees. In the Model school, teachers reported frequently using them and sometimes requiring students to use them, either with their mobile phones at school or as part of their homework. In contrast, teachers use digital technologies less frequently in the other two schools, largely because of gaps or poor quality in the schools’ digital resources. In these schools, students are not allowed to use their mobile phones during lessons. In Greece, mobile phones are officially prohibited in schools; the teachers in the Model school described seeking exceptional permission to enable students to use their phones in the classroom.

All the teachers gave examples of using English language films, videos or music in their lessons to supplement material from the textbooks or the Item Bank. Teachers at two schools referred to using the online exercises and digital resources provided with the textbook. In the Model school, teachers described using online platforms such as Kahoot and Quizlet to introduce games to support learning or Escape Classrooms and digital comics to stimulate creativity.

Each school has a dedicated information and communications technology (ICT) laboratory which can be used by teachers of any subject although ICT lessons have priority. In addition, School C has a room dedicated to film or video projections which teachers can reserve as required. Similarly, School B has a dedicated space for hosting or participating in webinars, shared across all subjects, and used by English teachers for virtual exchanges. In this school, the English teachers had also pushed to have a dedicated classroom for teaching languages. This room is set up with the necessary technologies (e.g. teacher computer, speakers, projector, interactive whiteboard). Although other classrooms may have this equipment too, the teachers felt that having their own space gives them more ownership over the technology and means it is more reliable.

Several of the teachers also talked about using digital technologies to facilitate work-related tasks. For example, they referred to eClass, the digital learning platform, principally for secondary schools, provided by the ministry and which can be used for uploading content, setting up tasks or activities, and communicating with students. They also described using the Internet to support lesson planning.

All participants generally viewed the use of digital technologies in English language teaching and learning positively. One teacher explained that students seem to respond well to it and find it more engaging, partly because technology already plays such a big role in their lives. The students were also positive. Several said that digital technologies help make English lessons more interesting, dynamic and entertaining; one described it as breaking down the monotony of traditional teaching methods. Others felt that technologies help them better understand texts or learn new vocabulary.

When you read a text, it might be complicated or confusing but when you watch a video it is clearer and helps you understand better […] We were raised with this technology, our generation is used to [it], it’s more interesting for us to watch a video than read a text, so it’s easier for us to understand. [Student, School B]

However, two teachers and one of the students emphasised the importance of finding a balance between digital and traditional approaches, and passive and active uses. Another student questioned the value of using digital technologies in English lessons.

Sometimes it is not very useful. For example, when we use Kahoot, some of the activities are not interesting and I feel we are wasting time. It’s rather an opportunity for playing around and noise in the classroom and I don’t think we learn anything useful by using it. [Student, School B]

I think it is best if it’s a combination of more traditional things and more modern things and there is something for everyone […] Students appreciate a teacher who wants to work whether they make extensive use of new technologies or not. [Teacher, School C]

Greece has made numerous efforts in recent years to expand the use of digital technologies in school education. This includes initiatives related to enhancing the digital infrastructure and resources available in schools, programmes to increase teachers’ digital competencies, and curriculum reform to better integrate digital skills transversally. Although progress has been made, efforts are ongoing and at least two of the schools participating in the case study continue to experience important digital resource challenges that constrain teachers’ capacity to integrate them into their teaching. This includes an unreliable Internet connection, a lack of devices for students and equipment for teachers (e.g. laptops or tablets, interactive whiteboards, projectors), a lack of related training and, in one school, a lack of classroom space generally, which results in the ICT laboratory being used for regular lessons.

I have taken an ICT course for my Master’s degree so I know that there are many things you can do. But it's not always easy in a public school to use technology. Often the Internet connection may be down, the computer may not be available and so on…there are practical problems every day. [Teacher, School A]

Here I don’t have problems in using technology, but I know that in other schools I would struggle to find a laptop because there might be only one which I would share, or there would be no video projectors, no whiteboards in the room. It would be difficult to use technologies. [Teacher, School B]

Textbooks are seen as very important but some students want updates

Textbooks are a crucial resource for all subjects in schools in Greece, including English. Teachers explained that they follow the set textbook, which in turn follows the national curriculum, and that all students have their own copy to work in. Generally, teachers perceive the textbooks positively, as a foundation to guide their teaching and students’ learning and as having interesting material which is connected to students’ lives.

Several teachers described the textbooks as providing a sense of security to the students both because they offer something physical for them to follow and because they help them see the longer term picture of their learning. One teacher also described it as a security mechanism for her.

Learning has also got to do with security. A student, having a text in front of them, gives them a reference point, it’s security for them… It’s something, I believe, that [the teachers] have all got used to and there is a reason we have got used to it. [Teacher, School C]

However, some of the students were more critical and felt that the textbooks are not challenging enough. They drew comparisons with the materials available to them in private language centres and criticised the textbooks in school for not pushing them to reach a higher level or not preparing them for certification. Another small group of students felt that the curriculum or teaching content was repetitive, dull or that it did not advance quickly enough. Only one of the students interviewed reported having above-average English language proficiency in comparison to their classmates, so this is not necessarily a perspective held only by high-performing students.

At school they treat us as if we are younger. For example, at age 8 we might learn the alphabet, the colours and the numbers, but we could have learned something more advanced like tenses or other grammar and vocabulary […] They should raise the level of English we do. It goes very slowly at school. [Student, School B]

Greece is currently working on updating the textbooks for English in upper secondary education to align with the introduction of the new Common Curriculum for Foreign Languages in upper secondary general schools (2023). These will aim to be more clearly based on the CEFR can-do statements and will include more up-to-date topics and materials, both printed and digital; the digital materials will be available on a dedicated digital platform or will be drawn from existing digital repositories of educational material. Greece will also introduce some choice for schools giving formal approval to two or three textbooks to allow teachers to choose a main textbook while also drawing material from the others via a digital platform.

References

[9] European Commission (2023), National Education System - Greece, https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/greece/overview (accessed on 8 September 2023).

[8] European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2023), Key data on teaching languages at school in Europe – 2023 edition, Publications office of the European Union, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/529032 (accessed on 20 September 2023).

[12] Liakos, A. (2016), The report of the National and Social Dialogue on Education [Η Έκθεση του Εθνικού και Κοινωνικού Διαλόγου], Asini publications, https://www.academia.edu/41465639 (accessed on 20 September 2023).

[6] Marconi, G., L. Vergolini and F. Borgonovi (2023), “The demand for language skills in the European labour market: Evidence from online job vacancies”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 294, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e1a5abe0-en.

[10] OECD (2023), Education at a Glance 2023 Sources, Methodologies and Technical Notes, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d7f76adc-en.

[5] OECD (2023), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en.

[3] OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/53f23881-en.

[14] OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Results (Volume II): Learning During – and From – Disruption, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a97db61c-en.

[1] OECD (2022), International Migration Outlook 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/30fe16d2-en.

[4] OECD (2022), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a8dd3019-en.

[13] OECD (2020), “Education Policy Outlook in Greece”, OECD Education Policy Perspectives, No. 17, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f10b95cf-en.

[11] OECD (2018), Education for a Bright Future in Greece, Reviews of National Policies for Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264298750-en.

[2] UNHCR (2023), Greece fact sheet, https://reporting.unhcr.org/greece-factsheet (accessed on 7 August 2023).

[7] Web Technology Surveys (2023), Usage statistics of content languages for websites, https://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language (accessed on 20 September 2023).

Note

← 1. In upper secondary general education, students in Grades 10 and 11 have their English assessed in this way; there are no end-of-year examinations for English in Grade 12. In upper secondary vocational education, only students in Grade 10 have their English assessed in this way. There are no end-of-year examinations for English in Grades 11 and 12.