This chapter examines the effects of Lithuania’s vocational training programmes for unemployed people on a rich set of labour market outcomes. In addition to outcomes typically examined in impact evaluations, such as employment probability and job duration, the analysis examines the effects of vocational training on wages, occupational mobility and earnings, including earnings net of the direct training costs. It also compares the results obtained by the counterfactual impact evaluation with those of similar studies, both for Lithuania and for other countries. The estimated effects are examined across sub-groups of people based on their age, gender, skill level and urban or rural location. The extent to which effects vary across different attributes of the vocational training programmes is also examined. The chapter concludes with an international comparison of the heterogeneous effects across sub-groups of individuals.

Impact Evaluation of Vocational Training and Employment Subsidies for the Unemployed in Lithuania

4. Evaluation of vocational training provided by the Lithuanian Public Employment Service

Abstract

4.1. Introduction

As the previous chapters have discussed, vocational training is one of the key active labour market policies (ALMPs) used to connect unemployed people with jobs in Lithuania. Furthermore, vocational training has scope to scale up considering that Lithuania’s expenditures on training for jobseekers is still low relative to the OECD average and that many jobseekers have low qualifications. By providing jobseekers with skills that are demanded in the labour market, they can help integrate individuals into the labour market and address shifts in the labour demand across occupations and sectors. Training jobseekers and people in risk of job loss is particularly important in the context of changing labour market needs that were accelerated during the COVID‑19 pandemic and continue to be significant in the post-pandemic labour market (OECD, 2021[1]; 2021[2]). To support labour reallocation effectively, training needs to reach the people who need it and equip them with the skills necessary to gain access to good quality jobs. This chapter examines how effective Lithuania’s vocational training has been in placing individuals into sustained employment, how it has affected their career prospects, and how the effects vary across individuals and the attributes of the vocational training programmes.

The estimation results show that vocational training generates positive and statistically significant effects on individuals’ probability of becoming employed, with effects that moderate over time. The estimated effects compare favourably to other studies evaluating of ALMPs, including previous studies of vocational training in Lithuania. Furthermore, certain sub-groups of jobseeker especially benefit from occupational training – for example, individuals above the age of 50, particularly women.

The organisation of the chapter is as follows. The first section presents the overall results of vocational training on the key outcomes examined: employment probability and duration, wages, occupational mobility and earnings, including earnings net of the direct training costs. It also compares the results obtained by the counterfactual impact evaluation (CIE) with those of similar studies, both for Lithuania and for other countries. The second section compares the outcomes observed for vocational training across sub-groups of workers based on their age, gender, skill level and urban or rural location. This is followed by an examination of the extent to which effects vary across different attributes of the vocational training programmes. The chapter concludes with an international comparison of the heterogeneous effects across sub-groups of individuals.

4.2. The vocational training programme has a positive effect on most outcomes examined

The next sections describe the aggregate results for vocational training on selected labour market outcomes. The first section describes the results for Lithuania on the six labour market outcomes examined, while the following section compares the results on employment probability with results from other studies.

4.2.1. Vocational training has positive effects particularly in the short term, but also in the long term

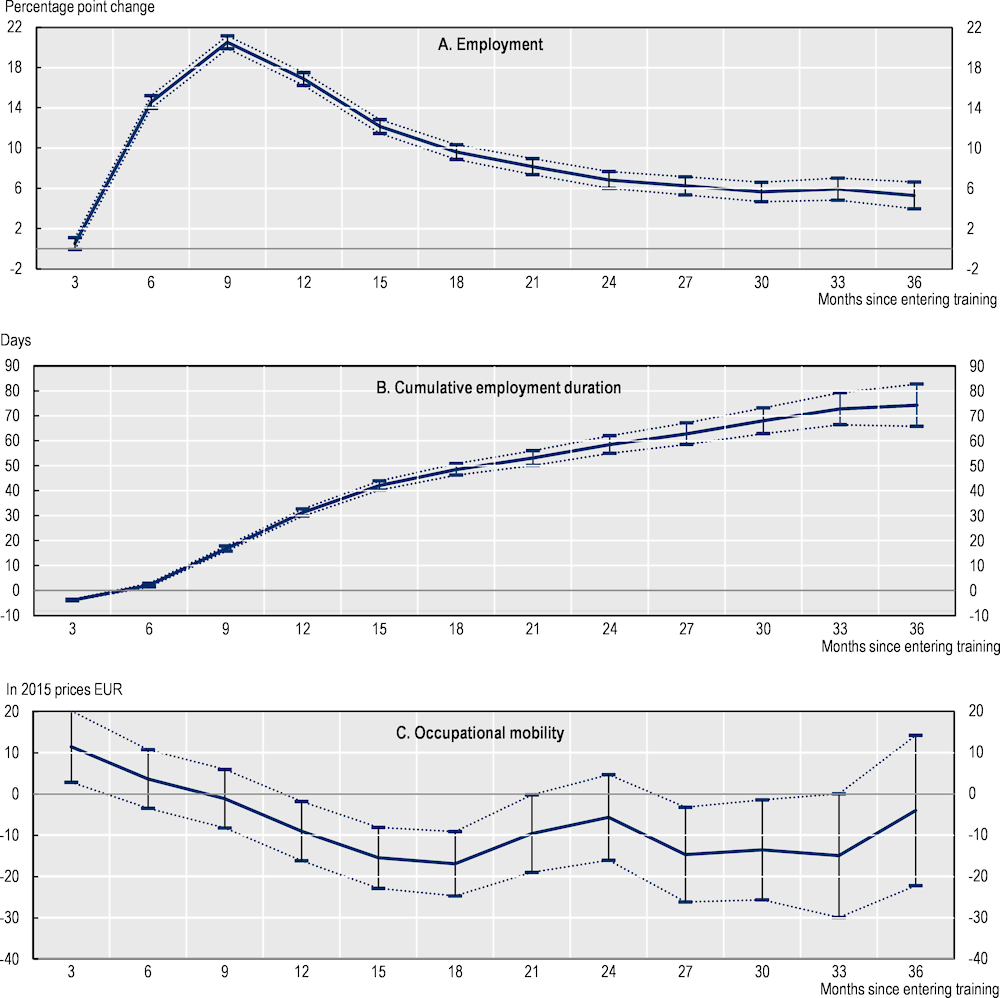

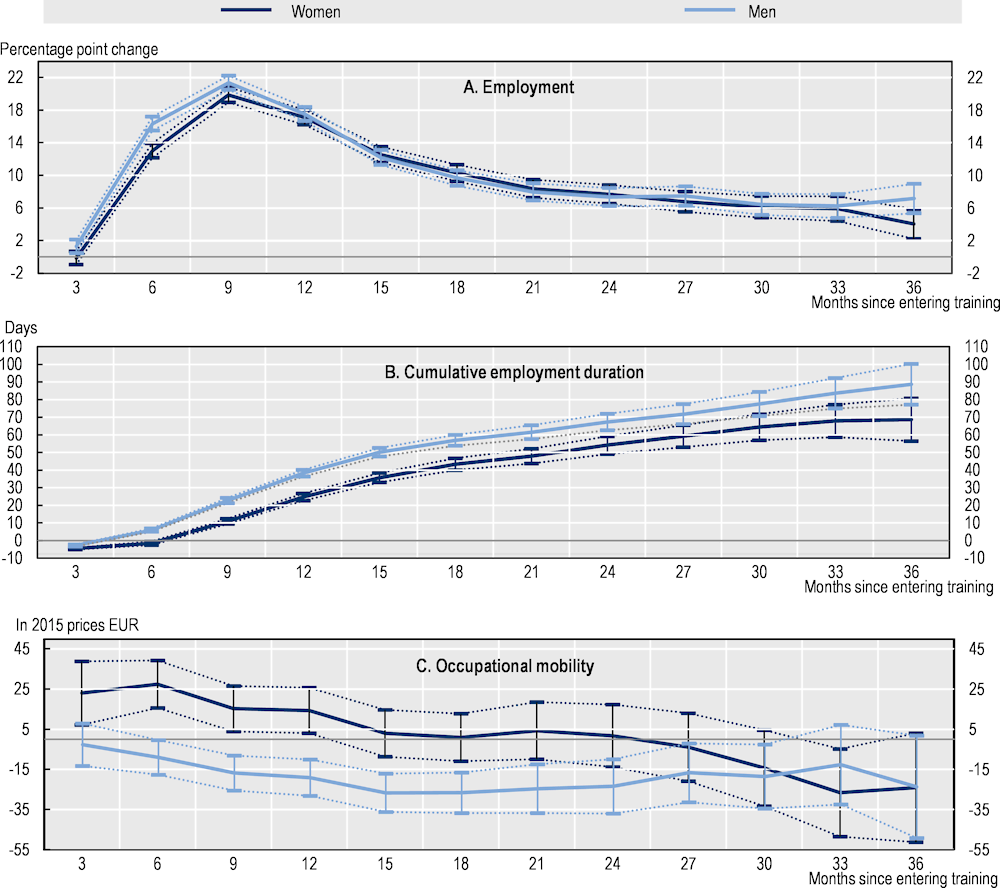

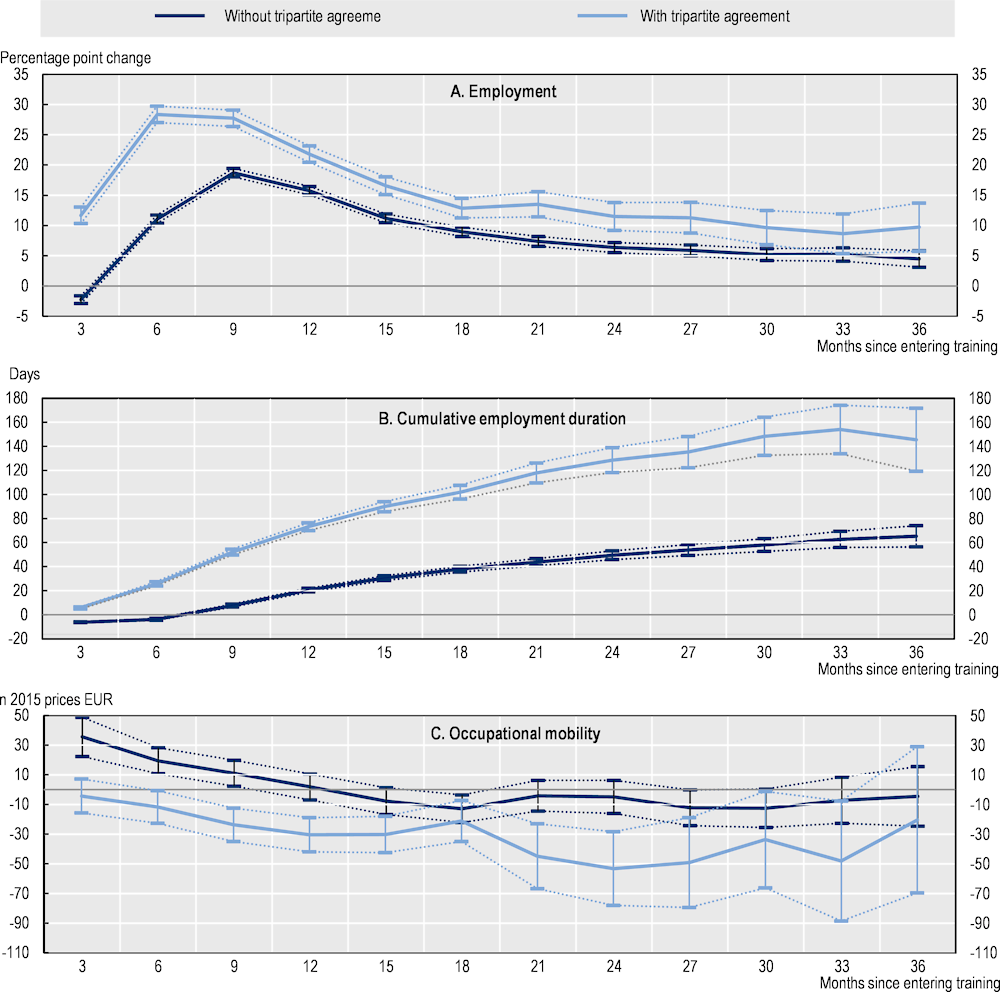

The estimation results show that vocational training generates positive and statistically significant effects on individuals’ probability of becoming employed, with effects that provide less of a boost over time (Figure 4.1, Panel A). The effects of training are initially modest but reach a peak effect at around nine months after beginning the training programme. At this point, individuals who participated in training (the treated group) were 20 percentage points more likely to be in employment than those who had not entered an ALMP in the first month of the observation period (the comparison group).1 The initially lower effect magnitude reflects the so-called “lock-in” effects, which mean that individuals in training are generally not engaging in intensive job search (they have less time for job search during training, as well as expect better job opportunities once the training is completed) and may not be willing to accept a job until they have concluded their training. After nine months, the effects of training diminish but remain positive through the three‑year evaluation period, amounting to 4 percentage points at the end of the period.

Initially, training also has a slightly negative effect on number of days in employment, but the effect becomes positive already at six months (Figure 4.1, Panel B). The duration of the initial lock-in effect at the beginning corresponds to the roughly 4‑month average duration of training. Over the longer term, the effect of vocational training amounts to approximately 75 days of additional employment.

The estimated effects of training on occupational mobility are found to be generally insignificant, with some estimates pointing to negative effects at longer time horizons (Figure 4.1, Panel C). The initially positive effect becomes negative from month 12 onward, with the average decrease in the point estimate of the index amounting to EUR 12 – meaning that those who became employed after training on average entered occupations that paid slightly less than those who had not engaged in training. The magnitudes of the effects in the index are not particularly large, amounting to roughly 1.1% of the index average. Taken with the previous results, however, they do indicate that even though participants are indeed more likely to be employed than non-participants they tend to enter into lower wage occupations.

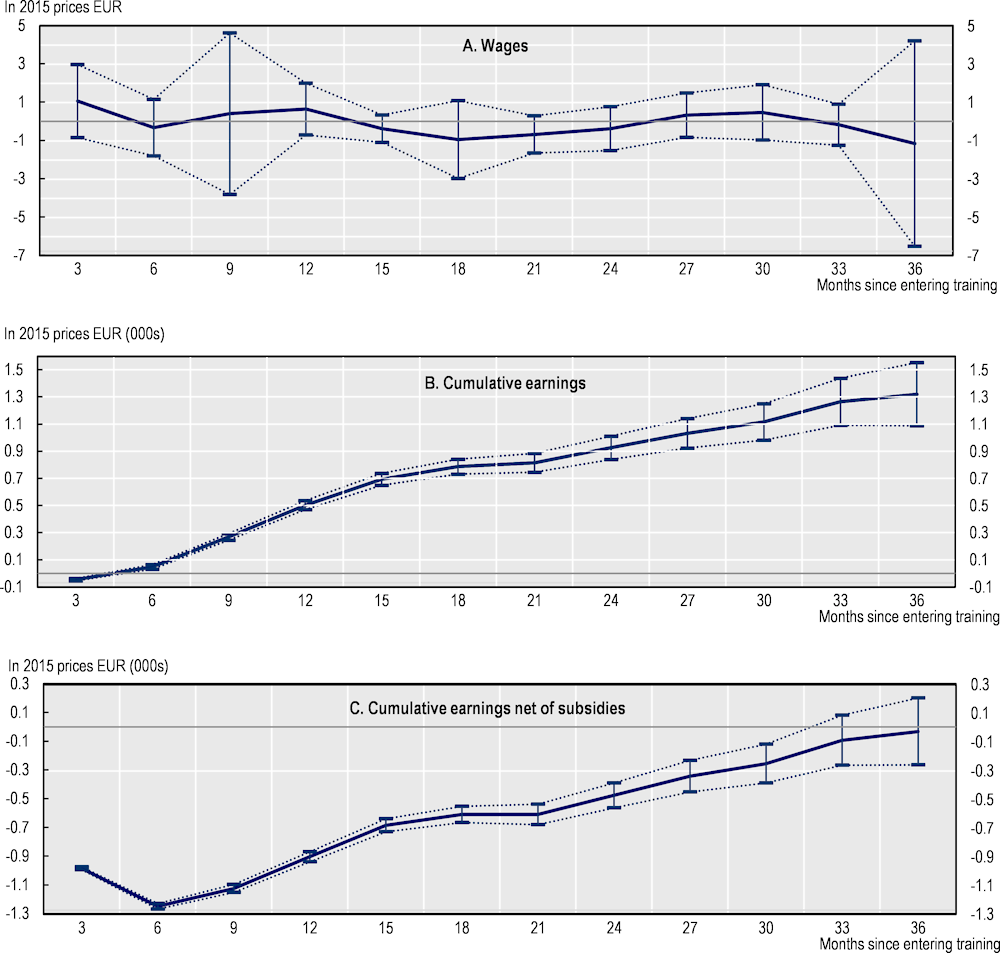

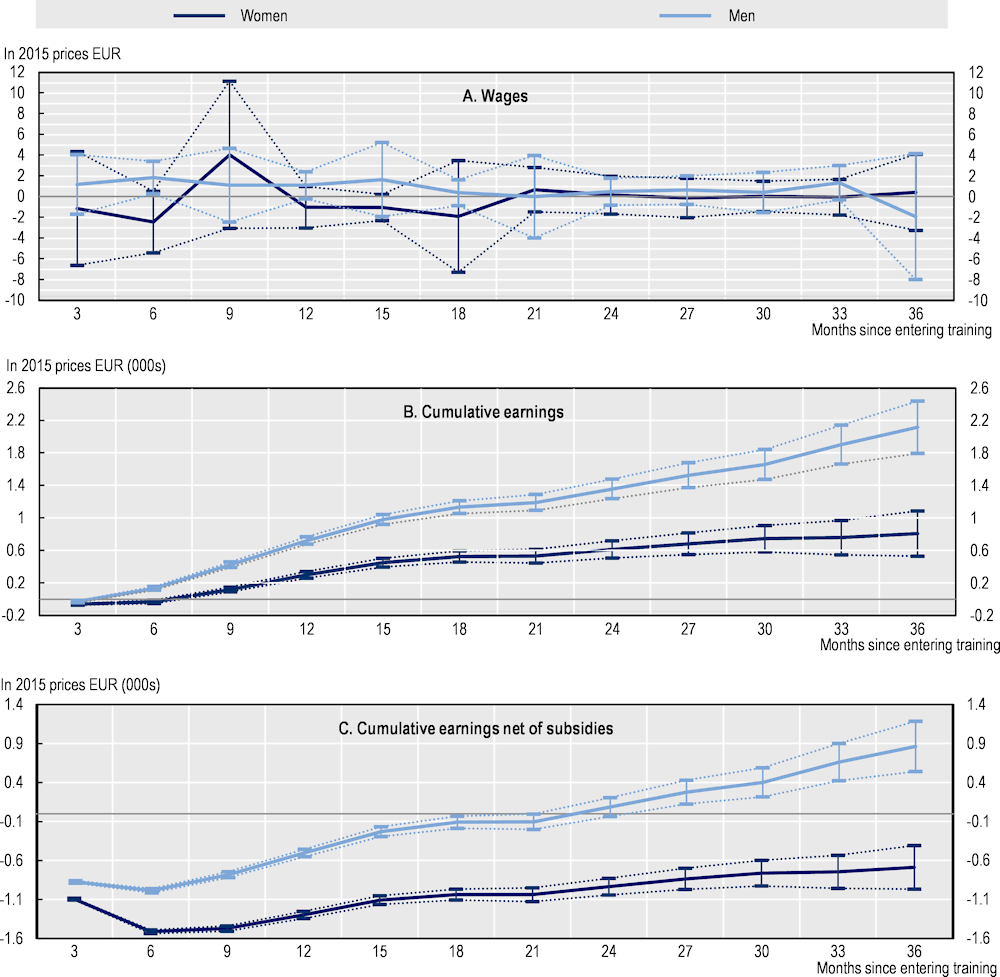

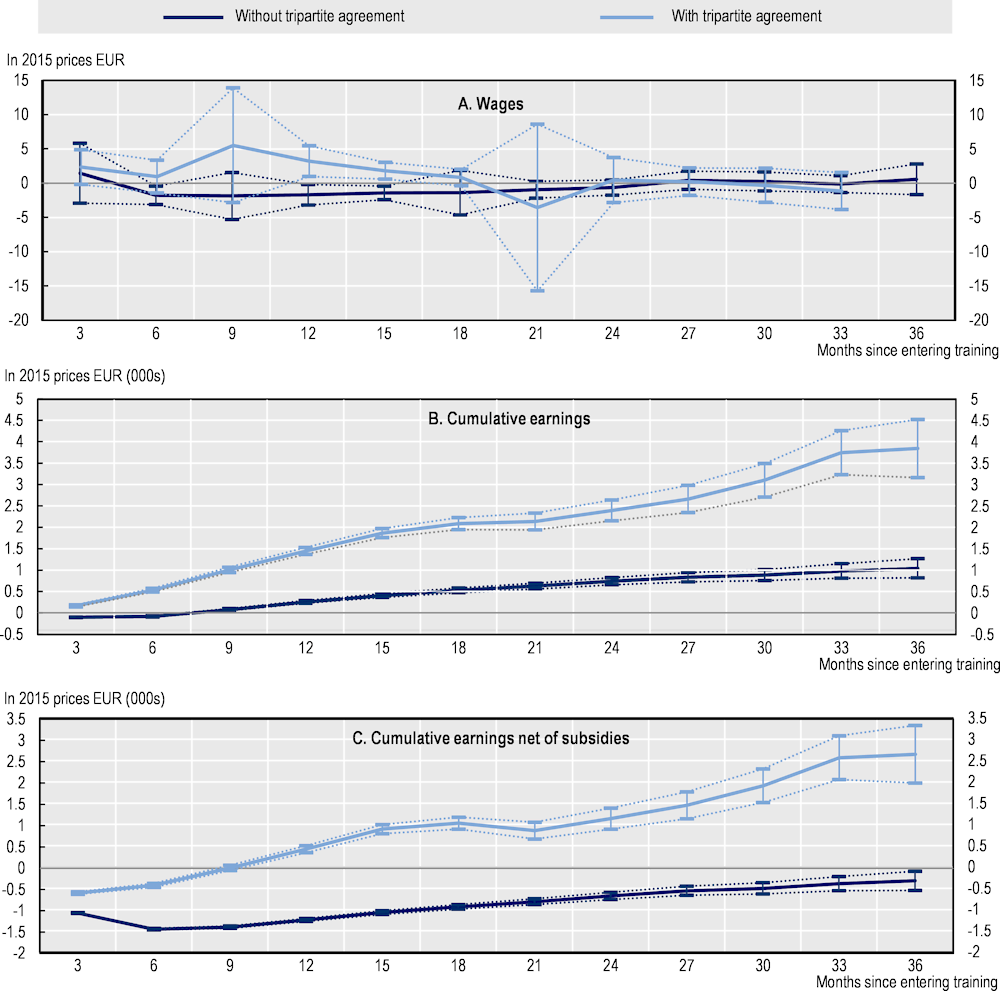

In line with the insignificant effect on occupational mobility, vocational training also does not have a discernible effect on wages (Figure 4.2, Panel A). This result does not mean that individuals are experiencing stagnant wages after becoming re‑employed, but rather that there are not systematic differences between the treatment and control groups. In fact, results not reported here show that individuals becoming employed early on in the observation period2 experience a small wage cut relative to their pre‑unemployment wages. However, both groups recoup the wage gap one year into the observation period, when they earn a slightly higher wage than they had before becoming unemployed.

The effects of the examined ALMPs on additional earnings attributable to programme participation are positive (Figure 4.2, Panel B). The estimated cumulative earnings associated with participation in training is initially slightly negative, but becomes positive already at six months, by which time many participants have completed their training. This finding is consistent with the positive observed effects on employment and the relatively insignificant effects on wages. The fact that cumulative earnings increase over time also indicates that any negative effects on occupational mobility are relatively small in aggregate.

A comparison of the cumulative additional earnings attributable to training participation with the direct per-participant expenditures on the programmes shows that the programmes reach a breakeven point 33 months after beginning training (Figure 4.2, Panel C). The effects are estimated by subtracting average programme expenditures per participant from the estimated additional cumulative amount of earnings attributable to the programme participation. Note that these calculations take into account only a narrow set of costs and benefits – they do not, for example, account for the likely reduction in social transfers arising result from the increased employment rate, as well as the corresponding increase in income tax revenues. They also represent only direct, partial equilibrium effects – training may result in spill-over effects with positive externalities, with the benefits of having a more skilled workforce resulting in more opportunities for other workers.

Figure 4.1. Vocational training in Lithuania has positive effects on employment probability and duration, but insignificant or slightly negative effects on occupational mobility

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]). The confidence intervals are shown at the 5% level of significance and represented by the whiskers delimiting the dotted lines on the charts.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Figure 4.2. Vocational training has positive effects on cumulative earnings but insignificant effects on wages and cumulative earnings net of subsidies in the long term in Lithuania

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]). The confidence intervals are shown at the 5% level of significance and represented by the whiskers delimiting the dotted lines on the charts.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

4.2.2. Lithuania’s training programmes’ effects on employment probability compare favourably with estimates from other studies, particularly in the short term

This section compares the results obtained by the CIE of the Lithuanian measures with those of similar studies, drawing on the meta‑analysis conducted by Card, Kluve and Weber (2018[4]) and previous results for Lithuania, particularly from the most recent study conducted by ESTEP (2019[5]). The meta‑analysis of international evaluations summarises estimates from over 200 recent impact evaluations of ALMPs. Of these, 51 impact evaluations contain point estimates for the employment effects of training programmes. Unfortunately, the meta‑analysis does not provide estimates of the effects of other outcomes analysed for Lithuania in this chapter, such as earnings or days worked.

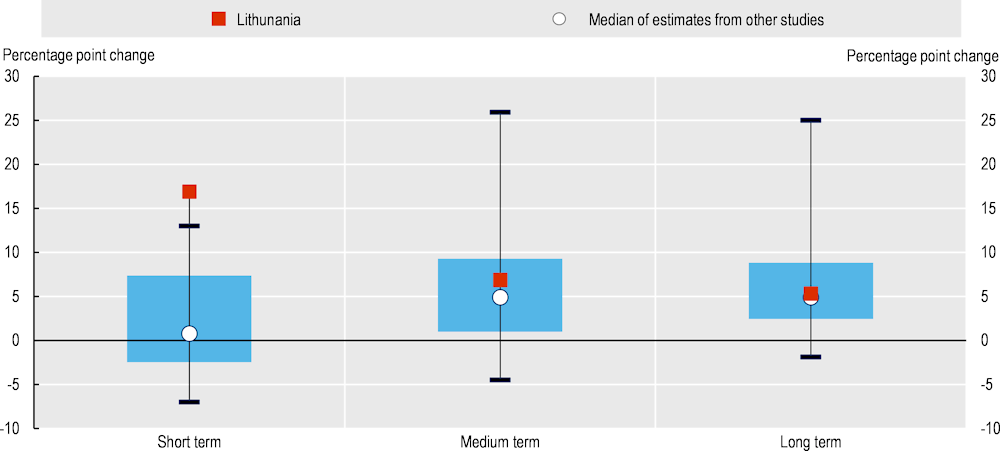

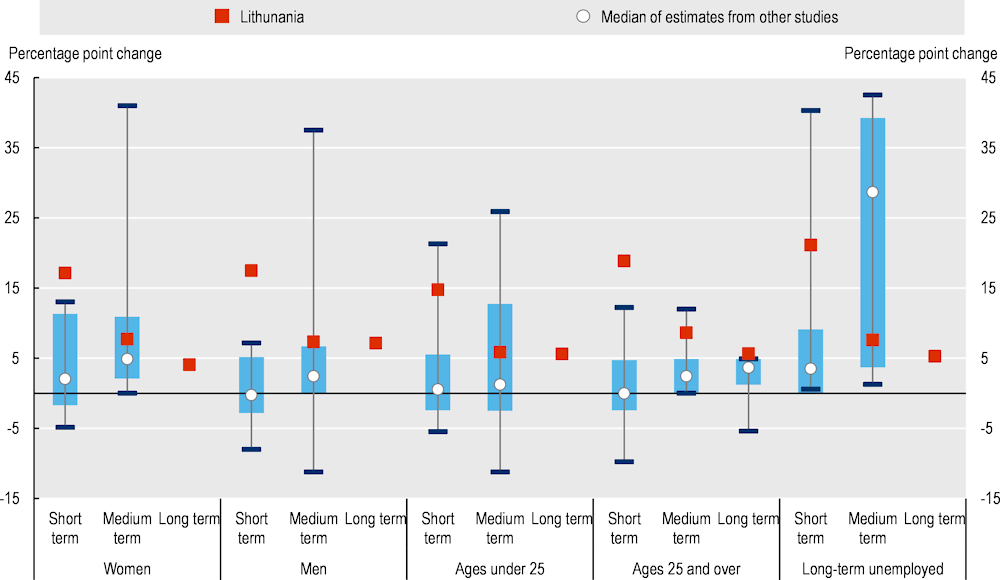

Compared with the results of the meta‑analysis by Card, Kluve and Weber (2018[4]), the estimated effects of training for Lithuania are generally much larger in the short term, and in the lower range of estimates over longer time horizons (Figure 4.3). The estimated short-term effect for training in Lithuania, 16.9 percentage points, is considerably higher than the average of 2 percentage points found in the comparison studies. On the other hand, the long-term effect, of 5.3 percentage points, is slightly lower than the 6.7 percentage point average of comparison studies.

Figure 4.3. Compared to other studies, the estimated effects of vocational training on employment probability are particularly positive in the short term in Lithuania

Note: Short, medium and long-term effects respectively refer to effects up to one year, 1‑2 years, and more than two years after programme completion. For Lithuania, results refer to 12, 24 and 36 months after beginning the programme. Point estimates are included in the chart even if they are statistically insignificant. The studies presented adopt various research designs and econometric techniques – the results for Lithuania use nearest-neighbour propensity score matching (for details, see Chapter 3).

Source: Card, D., Kluve, J. and Weber, A. (2018), “What Works? A Meta Analysis of Recent Active Labor Market Program Evaluations”, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx028 and OECD calculations based on data from the Lithuanian Employment Service.

In comparing the above results, it is helpful to keep in mind that there is wide variation in the estimates underlying the studies included in the meta‑analysis. For example, despite the meta‑analysis finding that training has a positive effect on average, around 65% of the studies relating to training did not find statistically significant positive effects in the short term (within a year) in the Card, Kluve and Weber (2018[4]) analysis. Also, 46% of studies did not find that training had statistically significant positive effects in the medium term (one to two years), and 33% did not find statistically significant positive effects in the long term (two or more years). The point estimate of the short-term effect for Lithuania in the current analysis is higher than most estimates in comparison studies, while the estimated long-term effect is close the median of estimates. The wide variability in the estimates may be attributable to a number of factors including the programme‑specific parameters (eligibility criteria, content and implementation of the programmes), the activation requirements of the control group that form the basis for the counterfactual outcomes, and other institutional or time specific factors. While making precise assessments is impeded by these numerous potentially confounding factors, the positive results in Lithuania may indicate that the design and implementation of training is generally superior to that of other similar programmes in other countries.

The estimated effects in this chapter also compare favourably to previous impact evaluations of vocational training in Lithuania, which themselves found contrasting results. In particular, the estimated effects are considerably more positive than the results reported by PPMI (2015[6]) who examined vocational training in Lithuania for an older time period (around 2010) and found no positive impacts on employment, as well as negative effects on earnings. On the other hand, they are more comparable to the results found by ESTEP (2019[5]), who analysed the effects of individual entering vocational training in 2016. The latter found that the effect of participating in vocational training after (roughly) two years amounted to 13 additional days worked and EUR 276 additional earnings.

4.3. The impacts vary across sub-groups of unemployed people and depend on characteristics of training provided

Through a better understanding of what works for whom, examining how vocational training helps different sub-groups of individuals can help inform the targeting of the measures, but also potentially redesign the measure to increase its effectiveness for some of the groups or even think of alternative measures that could benefit these groups more. While the results presented in the previous section have focussed on the aggregate effects of the programmes, a crucial additional set of questions concerns their effects across different characteristics of the training programmes offered, as well as across subgroups of unemployed. The subsequent analysis provides separate estimates for the results along several dimensions relating to jobseeker characteristics: (i) gender, (ii) level of education, (iii) urban vs. non-urban residence and (vi) long-term unemployment status. The analysis also provides separate estimates based on the specific characteristics of the training. Specifically, the analysis focuses on differences related to (i) the presence of tripartite agreement with a prospective employer, (ii) whether the training involves acquiring qualifications, and (iii) formal vs. informal training (results reported in the Annex).

Among these, one dimension that stands out is the role of a tripartite training agreement, entered into between the PES, the jobseeker and an employer who commits to employing an individual upon completion of the training. As will be discussed in continuation, such agreements, which accounted for roughly a quarter of all training undertaken during the 2014‑20 period, lead to highly superior outcomes compared to training undertaken without a prior agreement with an employer.

4.3.1. Certain sub-groups of jobseekers especially benefit from vocational training

Men tend to benefit slightly more from training than women according to a number of outcomes examined, particularly in terms of cumulative days in employment and cumulative earnings, but they experience a slightly worse medium-term effect on occupational mobility. Nevertheless, in terms of employment probabilities, the longer-term effects are relatively similar: 24 months after the start of training, the point estimates for the effects on women’s and men’s employment probabilities are 7.7 percentage points and 7.3 percentage points respectively (Annex Figure 4.A.1, Panel A). Earlier in the observation window, men experience slightly better effects on employment: six months after the start of training, men who began training experienced a 16.3 percentage point increase in the likelihood of employment, compared with a 13.1 percentage point increase for women. The increased employment probability translates into a greater number of cumulative days in employment: three years after beginning training, men undergoing training were employed for 89 days more in total, compared to 69 days for women (Annex Figure 4.A.1, Panel B). Interestingly, the qualitative effects of vocational training on occupational mobility by are the opposite of the effects on employment (Annex Figure 4.A.1, Panel C). Women experience a positive effect on occupational mobility in the short term (during the first 12 months after completing training), while men experience a negative effect for most of the periods observed after entering training.

At the same time, there are not any statistically significant effects of training on the daily wages of individuals who become employed (Annex Figure 4.A.2, Panel A), although most of the point estimates for men are positive. For men, the positive effects on days worked appear to offset any negative effects of occupational mobility: men experience a large, positive effect on cumulative earnings – including after accounting for the direct costs of the training. For women, on the other hand, the positive effect on earnings is not large enough to offset the direct costs of the training (Annex Figure 4.A.2, Panels B and C). Part of the reason might lie in the gender wage gap in Lithuania, which makes it more difficult for women to achieve a higher wage even after up-skilling. Decreasing the gender wage gap should be continuously addressed by wider employment and social policy responses in Lithuania.

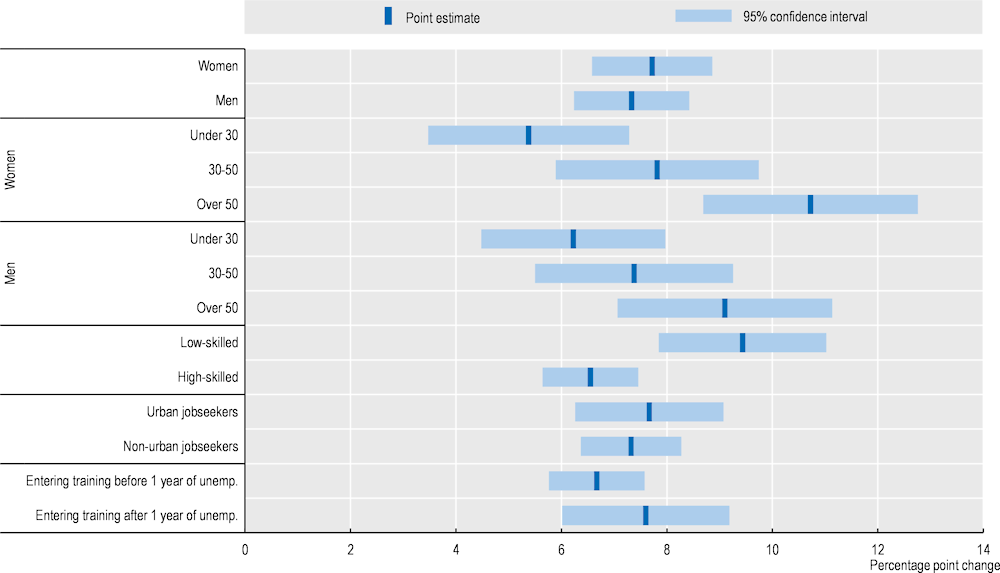

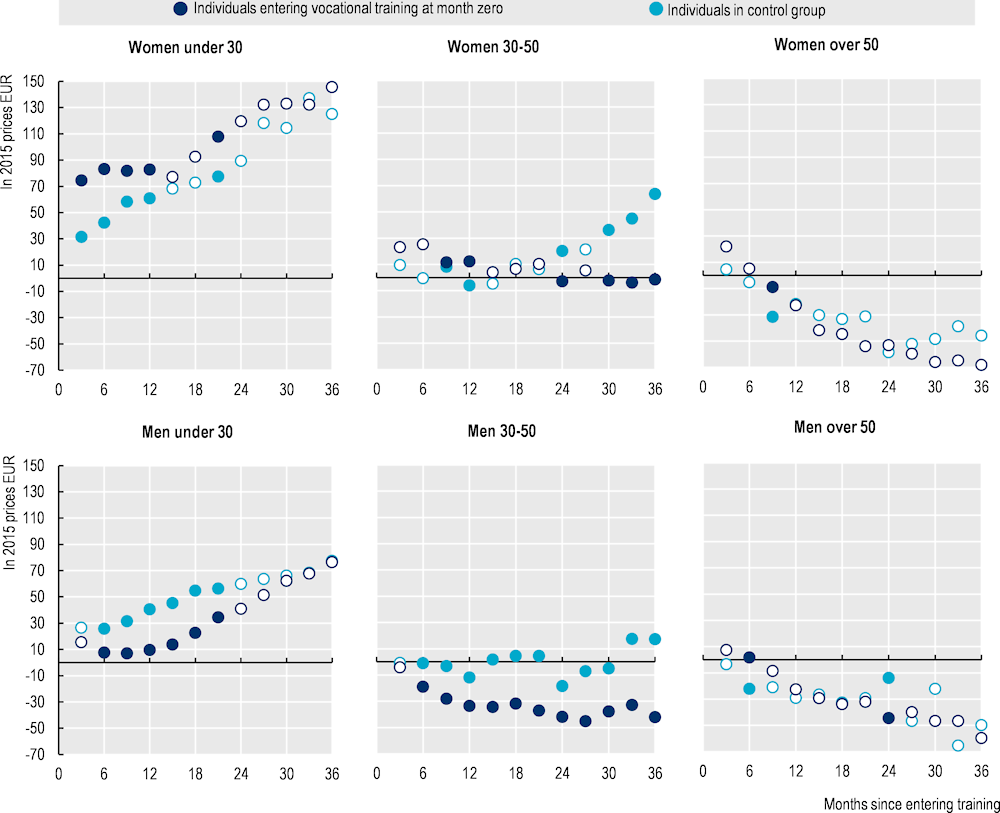

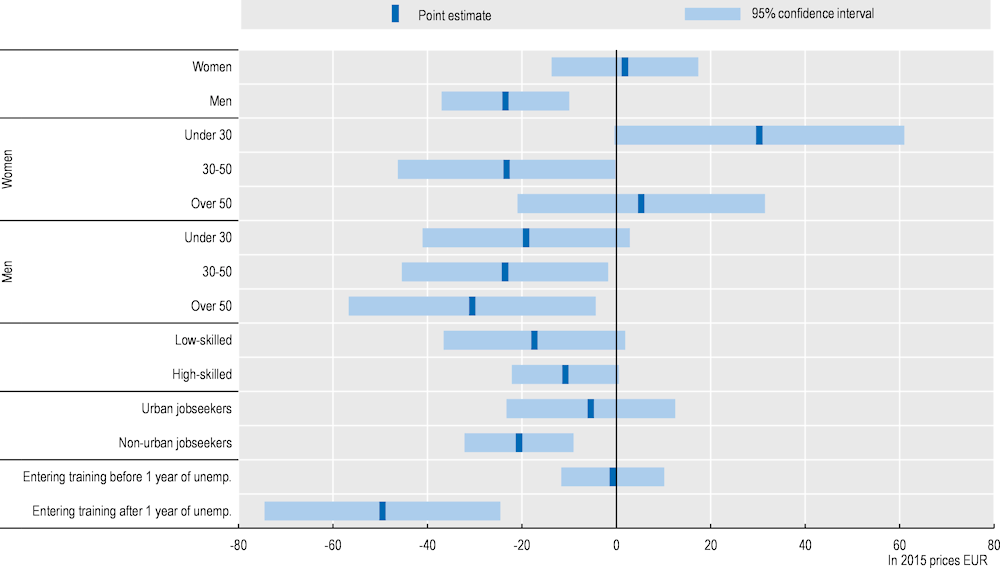

In terms of age, the results of the current analysis show that while the employment effects are positive for all age groups, they are progressively stronger for older groups of jobseekers (Figure 4.4). This is particularly the case for women. For women under 30, 24 months after entering training, estimates of the employment effect amount to 5.4 percentage points; for women over 50, the estimated effect is almost twice as high (10.7 percentage points). Low-skilled jobseekers appear to benefit slightly more than high-skilled jobseekers, while there do not appear to be systematic differences between large urban areas and other areas. Long-term unemployed benefit slightly more from being included in training than short-term unemployed, consistent with some findings of the literature (Card, Kluve and Weber (2018[4]), see Section 4.3.2 for details).

Figure 4.4. The positive employment effects of vocational training in Lithuania are particularly strong for certain sub-groups such as individuals over 50 years of age

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]).

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

The effects of vocational training on occupational mobility vary considerably across sub-groups of jobseekers (Annex Figure 4.A.3). As noted above, at 24 months after beginning vocational training, the effects are statistically significantly negative for men, with slightly larger negative effects for older cohorts of workers. In contrast to the results for men, there is weak evidence that young women experience a boost to their occupational mobility (although the effect is marginally statistically insignificant at the 5% level). One jobseeker characteristic that appears to have an important effect relates to unemployment duration, with those who become employed after entering training at least one year following the onset of their unemployment entering occupations that on average pay EUR 49.5 less on a monthly basis. Note that this comparison does not reflect downward occupational mobility of long-term unemployed, as the evaluation approach explicitly accounts for duration of unemployment.3 This represents a sizable negative effect on occupational mobility, amounting to 4.6% of the real average wage during this period. Jobseekers from non-urban areas also experience a negative effect on their occupational mobility, with those employed 24 months after beginning training entering occupations that pay EUR 20.6 less on a monthly basis.

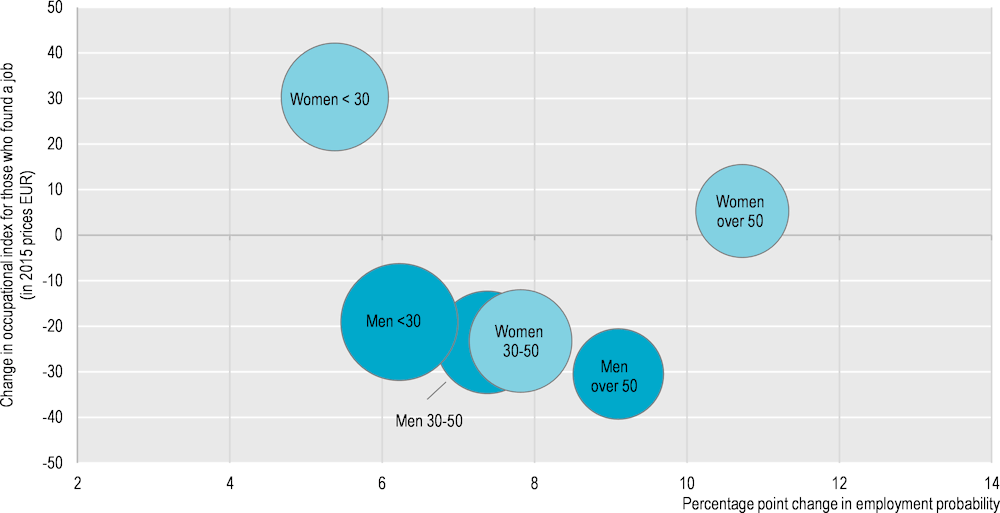

Comparing the above results on employment probability with those related to occupational mobility provides suggestive evidence that there exists a trade‑off between the two. Annex Figure 4.A.4 plots estimates of the two effects across gender and age group, estimated 24 months after individuals have entered training. The group experiencing the largest effect on occupational mobility – women under the age of 30 – also experience the smallest boost to employment probability. While the converse is not true – women over 50 experienced the greatest boost to employment probability and a moderate, albeit insignificant, boost to occupational mobility – the general trend holds for the other groups plotted. The relationship depicted in this figure, together with the fact that similar relationships exist between other sub‑groups of individuals in results not presented here, provide suggestive evidence that moving a greater share of individuals into employment via vocational training may partly come at the expense of occupational mobility. It could also be that the differences in the labour market outcomes and seeming trade‑offs between employment probability and occupational mobility across the groups are caused by differences in the specific training needs. For example, older jobseekers might need upskilling to catch up with changing labour market needs and continue working in their previous occupation. Younger age groups might more often undergo training to change their occupation altogether.

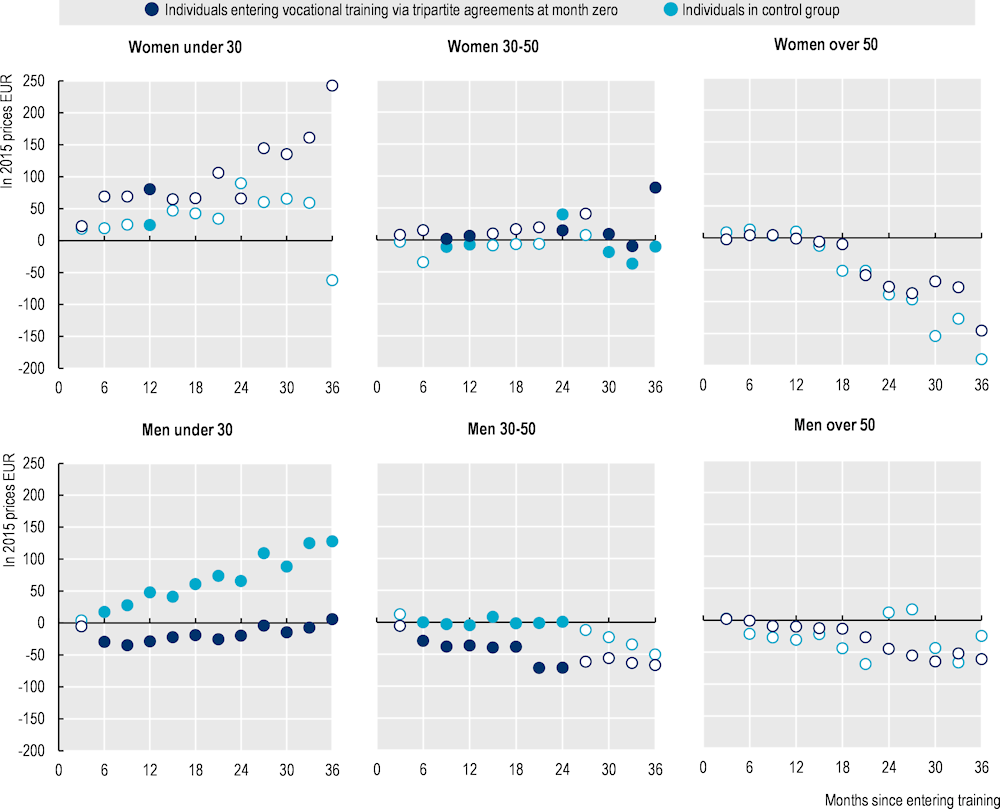

Examining the evolution of the estimated occupational index by age and gender shows stark differences in the profiles by age groups and also helps explain the above effects. Figure 4.6 plots changes to the occupational index over time, taking the month when individuals enter vocational training as the reference point. In contrast to results presented elsewhere in the chapter, the results here depict gross outcomes and not net outcomes (also known as treatment effects), which can be calculated by subtracting the values for the control group from the values for the treatment group. To examine the effects of tripartite agreements, Annex Figure 4.A.6 plots a figure analogous to Figure 4.6 but including only individuals entering training through tripartite agreements. Several interesting findings emerge from these figures:

For individuals under 30, both men and women generally experience increases in their occupational index over time – but young men entering vocational training have much lower occupational mobility than their peers, due largely to those entering training through tripartite agreements. While, women under 30 entering vocational training experience a positive boost to their occupational index in the first couple of months after entering training, men under 30 do not. Although men under 30 entering vocational training do experience growth in their occupational index, the magnitude of this increase is smaller than the increase in the occupational index experienced by their control group peers. However, men under 30 entering vocational training through tripartite agreements do not experience growth in their occupational index – the average values remains essentially unchanged during the entire period of observation. Over the longer time horizons, the negative effect associated with entering vocational training for individuals under 30 tends to disappear in general – but not for men under 30 who enter training through tripartite agreements. This may be attributable to the mix of the type of training taken up by individuals entering via tripartite agreements, with a large share focused on obtaining commercial drivers licenses.

For individuals aged 30‑50, individuals who entered vocational training and became employed experience either no change in their occupational index (in the case of women) or become employed in lower-ranked occupations (in the case of men). Here the effects of entering vocational training are more uniform regardless of whether or not the training is entered via tripartite agreements.

For individuals aged over 50, both men and women who become re‑employed tend to experience downward occupational mobility, regardless of participation in the vocational training programmes. Women, in particular, experience significant downward occupational mobility over time horizons longer than two years.

Figure 4.5. The effects of vocational training on occupational mobility varies across age groups in Lithuania

Note: The figure plots gross outcomes separately for individuals in the treatment and control groups. The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]). Estimates are plotted relative to their values at month zero. Shaded circles denote point estimates for which differences between individuals in the treatment and control groups are statistically significant at the 5% level of significance.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

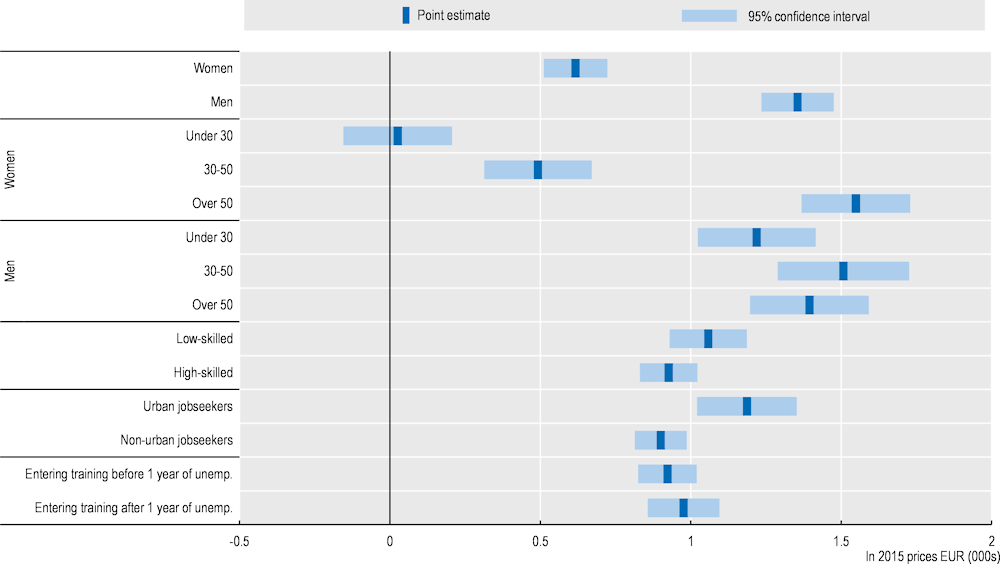

The effects of vocational training on cumulative earnings additionally highlight how the effects vary across jobseeker characteristics (Annex Figure 4.A.5). The finding that men experience a considerably greater boost to earnings – outlined in the discussion above – is attributable to the small magnitude of the effect for women aged 50 or older. Women under 30 in fact experience a statistically insignificant effect on earnings, while the magnitude of the effect for women aged 30 to 50 is also relatively small, amounting to EUR 492 in the first 24 months after entering vocational training. Finally, jobseekers in urban locations experience a larger boost in earnings compared to those in non-urban locations. This finding is in line with the previously discussed point that jobseekers in urban locations also experience more positive effects on occupational mobility and, to a lesser extent, employment probability.

The above results may also be partly explained by the types of training undergone by different sub-groups of individuals. Men disproportionally enter vocational training via tripartite agreements and enter into formal training programmes, which appear to confer certain advantages in terms of cumulative earnings and (short-term) employment prospects. At the same time, a large share of these training programmes for men involve programmes such as training to obtain a commercial drivers license, programmes which promise steady employment but offer poorer prospects for future occupational mobility.

4.3.2. Heterogeneous effects from other studies show that outcomes can vary considerably across studies and sub-groups

While comparing aggregate effects across studies is relatively straightforward, relating the sub-group analysis with estimates found in the existing literature faces two main challenges. The first challenge relates to the design of the programmes analysed: most existing meta‑analyses and systematic reviews consider how programme‑level treatment effects differ, rather than considering whether treatment effects differ for certain sub-groups within in a given programme. For example, rather than comparing women and men treated by mixed-gender programmes, such meta‑analyses and systematic reviews compare mixed-gender programmes, with all-women and all-men programmes. The second challenge relates to the definitions of the sub-groups, which do not necessarily match those used in this analysis. For example, the age threshold for younger individuals in most studies is 25 years of age, while the analysis for Lithuania uses a threshold at 29 years of age (with the latter having been chosen to reflect the age groups targeted by the measures in Lithuania).

Regardless of these challenges, some comparisons between the sub-group results in this chapter and the existing literature are possible: gender has been a special focus of many previous studies. There is some evidence suggesting that training may be more effective for women than men. Card, Kluve and Weber (2018[4]) find that female‑only training programmes outperform male‑only – with the differential effects present over both the short and medium term. Figure 4.6 juxtaposes the distribution of the point estimates in the Card, Kluve and Weber (2018[4]) study with those for Lithuania. Given that the point estimates for men and women are relatively similar in Lithuania at each of the time periods examined, in the context of the international comparison, training appears to give a relatively bigger relative boost to men in Lithuania. This may be partly attributable to higher rates of vocational training via tripartite agreements for men than women. However, it is worth noting that the finding relating to the effectiveness of training by gender is not replicated in another meta‑analysis conducted by Vooren et al. (2018[7]). Similarly, looking at differential effects by gender within a collection of mixed-gender training programmes in developing countries, McKenzie (2017[8]) finds no clear evidence that women benefit more than men.

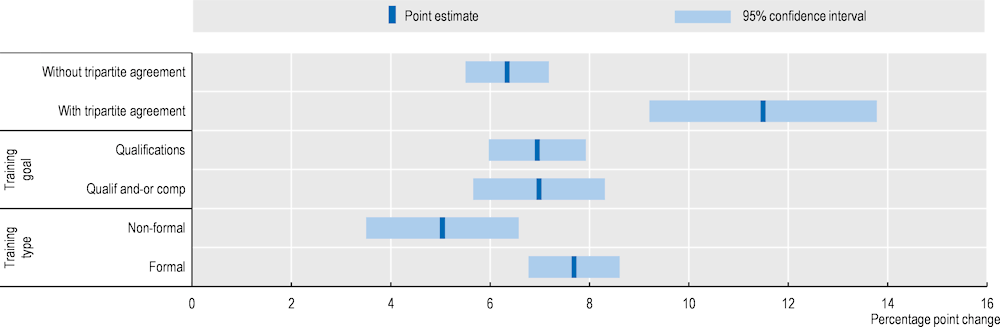

Figure 4.6. Training has heterogeneous effects on employment probability across sub-groups in both Lithuania and other countries

Note: Short, medium and long-term effects respectively refer to effects up to one year, 1‑2 years, and more than two years after programme completion. For Lithuania, results refer to 12, 24 and 36 months after beginning the programme. Point estimates are included in the chart even if they are statistically insignificant. Age groups for Lithuania refer to “under 30” and “30 and over”. Categories with less than five point estimates in the meta‑analysis are omitted from the above figures. The studies presented adopt various research designs and econometric techniques – the results for Lithuania use nearest-neighbour propensity score matching (for details, see Chapter 3).

Source: Card, D., Kluve, J. and Weber, A. (2018), “What Works? A Meta Analysis of Recent Active Labor Market Program Evaluations”, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx028 and OECD calculations based on data from the Lithuanian Employment Service.

In terms of international results on the effects of training by age, the evidence on whether younger or older workers benefit more is somewhat mixed. Card, Kluve and Weber (2018[4]) find that younger jobseekers receive a slightly greater boost from training in the short term than older workers, while both groups fare similarly in the medium term. Comparing the point estimates of these results with the ones obtained in this analysis for Lithuania (Figure 4.6), the Lithuanian programmes show a bigger boost in employment probability particularly for older and to some degree young workers than most comparable studies. In another meta‑analysis examining studies from numerous countries but with a strong focus on Germany, Vooren et al. (2018[7]) find that the maximum age of programme participants has no impact on ALMP measures’ effectiveness.

A final aspect that can be compared with other studies relates to how long individuals have been unemployed when they enter a training programme. The meta‑analysis conducted by Card, Kluve and Weber (2018[4]) finds that the impacts are larger for those programmes that explicitly target individuals in long-term unemployment – those who have been unemployed for over a year. Although the estimates from the international comparison are based on programme designed exclusively for either younger or older workers (whereas the findings for Lithuania are based on individual-specific effects), tentatively, their findings suggest that targeting the content of the training for long-term unemployed individuals (even after assignment to a training programme) may boost impact. In Lithuania, the vocational training programme is not explicitly targeted towards individuals who have been unemployed for over a year – instead, the estimates focus simply on those who entered a vocational training programme after having been unemployed for over a year. Comparing the two sets of results (Figure 4.6), the short-term effects of training in Lithuania are estimated to be higher than six out of seven comparable estimates in other studies, while the medium term estimates are higher than three out of eight comparable estimates. Estimates for the long-term effects are not plotted given the paucity of studies producing such estimates in the literature.

4.3.3. Examining the effects of training across vocational training programme parameters shows that tripartite agreements play an especially important role

One of the unique features of vocational training programmes in Lithuania is the possibility of having the employer commit to hiring a specific worker who successfully completes a vocational training programme for at least six months. The counterfactual impact analysis shows that signing such a tripartite agreement with an employer in advance of receiving the training boosts the observed employment effects of the training considerably. The presence of such a tripartite agreement – entered into force between the jobseeker, the LES and the employer – results in an 11.5 percentage point increase in employment probability 24 months after entering training, compared to a 6.3 percentage point effect among those who did not have such an agreement as part of their training (Annex Figure 4.A.7, Panel A). In the short term, the differences in the effects are even more pronounced: six months after entering training, individuals with tripartite agreements experienced a 28.3 percentage point increase in employment probability, compared to 11 percentage points for those entering training without a tripartite agreement. This finding is not surprising given that both the employer and the worker are contractually obliged to maintain the employment contract for at least six months after the training has concluded. Nevertheless, the point estimates associated with having a tripartite agreement remain consistently higher throughout the period observed, although the differences are not as large after the first 12 months, averaging 5 percentage points in the ensuing period. Given that training programmes are not longer than 12 months (with less than 5% between 9 and 12 months in duration), any effects after 18 months reflect employment which is not bound by contractual obligations arising from the tripartite agreements.

The positive effects of vocational training with tripartite agreements may have several explanations. Such agreements may have a positive effect both on jobseekers – who may be more engaged in their training and better motivated to complete it given the promise of employment – as well as having a positive effect on their subsequent employment prospects, with training better reflecting the (short-term) needs of employers. In fact, although the vast majority of vocational training participants complete their training, jobseekers with tripartite training agreements are less than half as likely to drop out of their training programmes before completing them compared to individuals without such agreements (the non-completion rates during 2014‑20 averaged 3.9% and 1.7%, respectively).

Tripartite agreements also have a positive effect on cumulative employment duration. Three years after beginning training, individuals with tripartite agreement are employed for 145 days more than people not receiving training, compared to 66 extra days of employment for those undergoing training without the tripartite agreement (Annex Figure 4.A.7, Panel B). As mentioned above, any effects later than 18 months after entering training reflect employment which is not bound by contractual obligations arising from the tripartite agreements – these can be considered successful job matches.

In contrast to the positive results on employment, having a tripartite agreement has a slightly negative effect on occupational mobility – for almost the entire time horizon examined after entering training, the effect is statistically significant (Annex Figure 4.A.7, Panel C). Averaged over all the time periods, it amounts to EUR 31 – meaning that individuals who undergo training via a tripartite agreement subsequently enter occupations which had an average gross monthly wage of EUR 31 less, or 2.9% of the observed real average gross monthly wage.4

On the other hand, the effect of vocational training on wages is unclear (Annex Figure 4.A.8, Panel A): although the point estimates for individuals with tripartite agreements are generally positive, with few exceptions, they are not statistically significant. Conversely, for individuals who enter training without tripartite agreements, the point estimates are generally negative but also generally statistically insignificant. These results suggest that any effects of vocational training on daily wages are too small to be precisely measured in the data.

Despite their slightly negative effects on occupational mobility and insignificant effects on wages, tripartite agreements are associated with strongly positive effects on cumulative earnings, including after accounting for the direct costs of the training (Annex Figure 4.A.8, Panels B and C). After three years, individuals with tripartite agreements had cumulative earnings that amounted to EUR 3 841 more than their comparable peers who did not enter training; the respective amount for those entering training without tripartite agreements amounts to EUR 1 051. After subtracting the direct costs associated with training, the net earnings for individuals with tripartite agreements amounted to EUR 2 676, while the comparable amount for individuals without tripartite agreements is almost statistically insignificant after three years.

The strong finding on the role of tripartite agreements is in line with other findings in the literature. In a recent meta‑analysis, Ghisletta, Kemper and Stöterau (2021[9]) find positive effects of involving non-public actors – which they include to mean those from the private sector (e.g. employer associations), NGOs or other organisations – in the design or implementation of vocational training programmes on youth labour market outcomes. Interestingly, they find slightly stronger results for having such actors involved in the design of such programmes, with slightly smaller (but still positive) effects of involving them in the programme’s implementation. The results for Lithuania can be loosely interpreted as being in line with these findings as well: the employers are involved in the choice of which training individuals engage in, as the future employer agrees on which training is to be undertaken based on what they deem to be relevant from the roughly 2000 vocational training courses offered in principle. This can help employers address local skill shortages, with employers willing to commit to hiring a worker and wait for them to complete the training.

In addition to the presence of a tripartite agreement, additional programme aspects examined include (i) whether the training has a focus only on obtaining qualifications and (ii) whether it involves formal or non-formal training. The focus of the programme does not have a significant effect on employment probability, while formal vocational training programmes outperform non-formal ones by 2.6 percentage points (Annex Figure 4.A.9).

References

[3] Abadie, A. and G. Imbens (2016), “Matching on the Estimated Propensity Score”, Econometrica, Vol. 84/2, pp. 781-807, https://doi.org/10.3982/ecta11293.

[4] Card, D., J. Kluve and A. Weber (2018), “What Works? A Meta Analysis of Recent Active Labor Market Program Evaluations”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 16/3, pp. 894–931, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx028.

[5] ESTEP (2019), Aktyvios darbo rinkos politikos priemonių bei tarpininkavimo įdarbinant ir įdarbinimo tvarumo stebėsenos ir vertinimo sistemos sukūrimo paslaugos.

[9] Ghisletta, A., J. Kemper and J. Stöterau (2021), The impact of vocational training interventions on youth labor market outcomes: A meta-analysis, https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/dual/r4d-tvet4income-dam/documents/LELAM_WorkingPaper_No.20_Meta_Analysis_Training.pdf.

[8] McKenzie, D. (2017), “How Effective Are Active Labor Market Policies in Developing Countries? A Critical Review of Recent Evidence”, The World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 32/2, pp. 127-154, https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkx001.

[1] OECD (2021), “Designing active labour market policies for the recovery”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/79c833cf-en.

[2] OECD (2021), OECD Employment Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5a700c4b-en.

[6] PPMI (2015), Final Report on Counterfactual Impact Evaluation of ESF Funded Active Labour Market Measures in Lithuania, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12469.83689.

[7] Vooren, M. et al. (2018), “The Effectiveness of Active Labour Market Policies: A Meta-Analysis”, Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 33/1, pp. 125-149, https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12269.

Annex 4.A. Additional figures

Annex Figure 4.A.1. The effects of vocational training on employment probability, duration and occupational mobility varies by gender in Lithuania

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]). The confidence intervals are shown at the 5% level of significance and represented by the whiskers delimiting the dotted lines on the charts.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Annex Figure 4.A.2. Men in Lithuania experience a greater boost to cumulative earnings and cumulative earnings net of subsidies

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]). The confidence intervals are shown at the 5% level of significance and represented by the whiskers delimiting the dotted lines on the charts.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Annex Figure 4.A.3. Vocational training in Lithuania has a negative effect on the occupational mobility of certain sub-groups such as the long-term unemployed

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]).

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Annex Figure 4.A.4. Groups experiencing boosts to employment probability from vocational training in Lithuania may also experience lower occupational mobility

Note: The size of the circles is proportional to the number of vocational training programme participants in the respective sub-group. All estimates refer to effects 24 months after entering training. The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]).

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Annex Figure 4.A.5. Vocational training in Lithuania has a positive effect on cumulative earnings for most sub-groups of unemployed individuals

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]).

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Annex Figure 4.A.6. Young Lithuanian men entering vocational training through tripartite agreements have much lower occupational mobility than their peers

Note: The figure plots gross outcomes separately for individuals in the treatment and control groups. The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]). Estimates are plotted relative to their values at month zero. Shaded circles denote point estimates for which differences between individuals in the treatment and control groups are statistically significant at the 5% level of significance.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Annex Figure 4.A.7. Tripartite agreements in Lithuania are associated with particularly positive employment effects but have a negative effect on occupational mobility over some time horizons

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]). The confidence intervals are shown at the 5% level of significance and represented by the whiskers delimiting the dotted lines on the charts.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Annex Figure 4.A.8. Tripartite agreements have particularly positive effects on cumulative earnings in Lithuania, but the effects on wages are unclear

Note: The analysis presents nearest-neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit receipt and level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment, as well as prior employment history and earnings. For every individual in the treatment group, the matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when the individual enters the programme. The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics not entering ALMPs in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]). The confidence intervals are shown at the 5% level of significance and represented by the whiskers delimiting the dotted lines on the charts.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Annex Figure 4.A.9. The presence of a tripartite agreement and having formal vocational training are both associated with more positive employment outcomes in Lithuania

Note: The analysis presents nearest neighbour propensity score matching results which matches individuals based on a number characteristics: duration of unemployment, age, gender, education, unemployment benefit level, language and other skills, municipality, employability and barriers to employment (as assessed by LES counsellors), as well as prior employment history and earnings. The matching is conducted based on the values of these characteristics in the calendar month when an individual enters the programme (for individuals in the treatment group). The control group is comprised of individuals with similar characteristics who do not enter any ALMP in that same calendar month. For paired individuals in the treatment and control groups, this calendar month is then the reference point after which outcomes are measured in 3‑month intervals, up to 36 months. The analysis is restricted to the region of common support. The standard errors are calculated based on the adjustment proposed by Abadie and Imbens (2016[3]).

Source: OECD calculations based on the Lithuanian Employment Service and Lithuanian State Social Insurance Fund Board.

Notes

← 1. The control is comprised of comparable individuals who, in the month when another individual entered into vocational training, did not enter any of the following ALMPs (for which individual-level data were available): Subsidised employment, Vocational training, Supporting the acquisition of work skills, Internship, Recognition of competencies and Apprenticeships. Such individuals could have conceivably entered one of the following ALMPs during that same month: Employment incentives, Supported employment and rehabilitation, Direct job creation, Support for mobility, Support of social enterprises, Local Employment Initiative projects, Job rotation, Subsidised employment of the disabled, Vocational (occupational) rehabilitation and Subsidy for individual activities under a business license.

← 2. For individuals in the treatment group, the beginning of the observation period corresponds to when they entered an ALMP. For those in the control group, the beginning of the observation period corresponds to when they were matched to someone in the treatment group, i.e. after being unemployed for a similarly long period of time as the individual entering treatment with similar observable characteristics.

← 3. This is done via so-called coarsened exact matching – individuals in the treatment group are matched exclusively to individuals with similar unemployment durations, based on six categories of unemployment duration.

← 4. To give a sense of the relative size of the effect on occupational mobility, note that the average cumulative duration of employment for individuals entering training via tripartite agreements was 751 days. Having monthly earnings reduced by EUR 31 thus corresponds to having cumulative counterfactual earnings decrease by EUR 765.