This chapter is an introduction to this book and sets out the motivation. It briefly introduces the role of firms in addressing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly through their core business and the expected role of industrial policies to foster the contribution of business activities to the attainment of SDGs.

Industrial Policy for the Sustainable Development Goals

1. Introduction

Abstract

In 2015, the member states of the United Nations (UN) adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Devised as an agenda for global sustainable development, they reflect the commitment of stakeholders to eradicate poverty, respect human rights, empower women and girls, and bring prosperity and peace, while tackling climate change and working to preserve oceans and forests.

However, in its 2020 SDG report, five years after the adoption of the SDGs, the UN warned that the global response has not been sufficiently ambitious, despite progress in some key areas. There is an urgent need to increase the pace of action from all stakeholders if the goal of achieving the SDGs by 2030 is to be met.

This urgency is amplified by the COVID-19 crisis, which highlights not only the need for sustainability and resilience, but also the importance of health. However, its effects may compromise our ability to reach the SDGs by 2030 (Ranjbari et al., 2021[1]). The impact of the crisis is likely to be particularly acute on sustainability investments in the business sector, which has seen its financial capacity significantly affected by liquidity constraints and increasing debt burdens.

This crisis is also triggering a new wave of policies and recovery plans, with the objective to “build back better”. Some of these policy packages are clearly connected to the SDG agenda and acknowledge the need to support firms’ investments in sustainability, especially regarding the environment (e.g. European Recovery Fund, Korean New Deal).

Figure 1.1. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals

Source: United Nations.

This book explores the role of firms in addressing the SDGs, particularly through their core business, and how industrial policies can foster the contribution of business activities to the attainment of SDGs. Through selected business examples and the use of survey data, this book provides evidence that numerous firms consider it to be economically viable to develop sustainable products and services. In addition, it addresses the measurement of firms’ SDG orientation both by offering several methodological contributions and providing new insights. In particular, it proposes a methodology to identify SDG-related economic activities with the help of a machine learning (ML) algorithm trained to detect SDGs, and uses ICIO tables to uncover the cross-border and cross-sectoral impacts of SDG-related activities. Finally, this book examines how industrial policies (including innovation and general business framework policies) can foster the contribution of firms to the SDGs through their core business, thanks to a benchmark analysis of the existing policy landscape in a sample of seven countries plus the European Union, and a detailed analysis of the policy instruments.

Developments in the areas of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and responsible business conduct (RBC) show that firms are increasingly aware of their impact on SDGs. More recently, the rise of environment, social and governance (ESG) investing demonstrates the appetite of consumers, savers and financial intermediaries for more responsible firms and the need for increased transparency on corporate sustainability actions (Box 1.1).

Demand for social and environmental accountability of firms has been increasing over the last 30 years. Many stakeholders consider that the societal role of private companies is not only to maximise value for their shareholders, but also to contribute actively – along with governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), households and international organisations – to global social goods, such as the environment and societal outcomes. This engagement can take several forms; the activities of some firms are inherently and directly linked to SDGs (via the goods produced and/or services provided), while others focus on the mitigation of the negative impact of their daily operations on SDGs, or use the resources of the company to fund philanthropic organisations that contribute to the achievement of SDGs.

In line with this demand of increased accountability, previous works have focused on either promoting principles, standards and guidelines to help businesses manage their social and environmental risks or measuring the distance to the SDG targets at the country level (e.g. Box 1.2). However, the measurement of a firm’s impact remains challenging. Whereas SDGs provide common goals, commonly agreed business indicators of sustainability remain a distant objective. At the firm level, measures are not only required by the firm’s management to objectivise the impact and efficiency of the firm’s actions, but also to provide indicators on which to index public policies (for instance, carbon dioxide emissions for climate change mitigation policies). Moreover, such indicators would also be required at the aggregate level to assess the achievements of the private sector and to build sound SDG policies.

This book contributes to bridging this gap by highlighting how firms can positively contribute to the SDGs, and by paving the way for measurement of the private sector’s involvement in, or contribution to, the SDGs. It takes a transversal approach to the SDGs, although it sometimes focuses on some Goals or targets, as an illustration. Moreover, the analysis identifies the SDGs that firms prioritise or have an impact on. In addition, it distinguishes between core business-related SDGs and those that are pervasive in non-core business activities.

The recent literature emphasises the role of industrial policies (including innovation and general business framework policies), which often take the form of mission-oriented industrial strategies (Criscuolo et al., forthcoming[2]; Larrue, 2021[3]; Mazzucato, 2018[4]), directly target innovation and growth for overcoming societal challenges. This literature has often focused on green industrial strategies (Altenburg and Rodrik, 2017[5]; Tagliapietra and Veugelers, 2020[6]).

This book builds on this literature, which mostly focuses on climate change, and extends it to the SDGs, using evidence gathered on the firms’ contributions to the SDGs and a benchmark analysis of the existing policy landscape in a sample of seven countries plus the European Union. It shows that governments are already using a diverse set of policy instruments to promote firms’ sustainability, and emphasises the need for a comprehensive toolkit, as well as its adequate articulation and governance through mission-oriented industrial strategies.

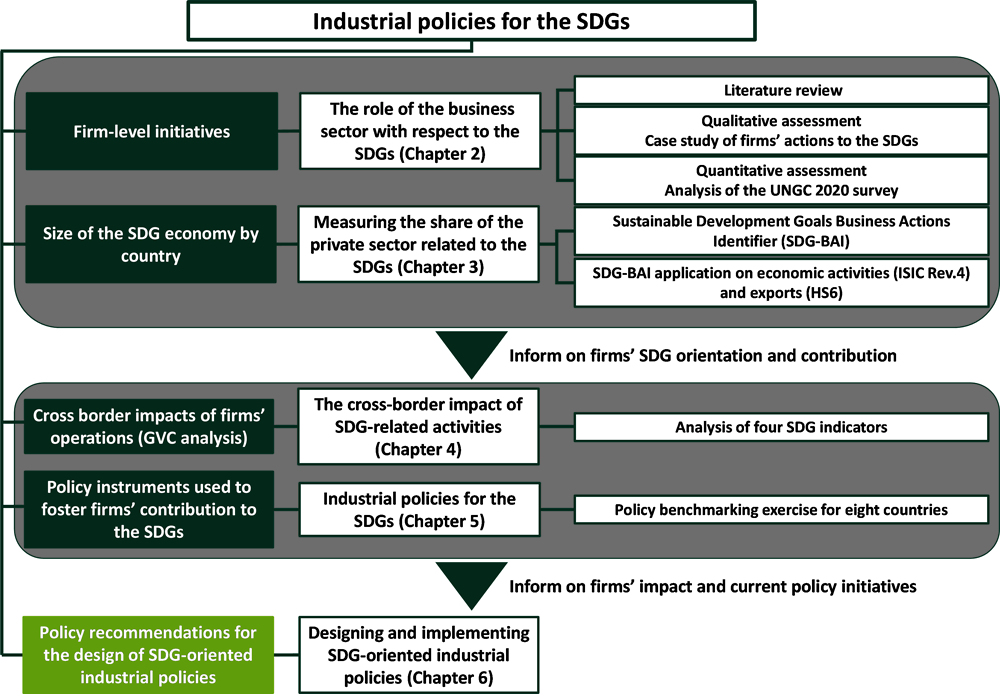

Chapter 2 reviews the available information on the engagement of firms, relying on existing literature, examples of firms’ actions, and survey data from the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC). The difficulty in measuring contributions to the SDGs at the firm level is evident, despite several frameworks in development by international initiatives (which are also summarised). Acknowledging the need for further work and harmonisation from the relevant standard-setting bodies regarding the contribution to SDGs at the firm level, Chapters 3 and 4 propose three methodological contributions regarding the measurement of SDG orientation in a cross-country setting: 1) the construction of an ML algorithm that automatically identifies the SDGs in a short text; 2) an experimentation with the identification of sectors and products inherently linked to SDGs using the aforementioned algorithm; and 3) the use of the OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA)/ICIO infrastructure to measure the cross-border impact of SDG-related activities on selected SDG indicators. Chapter 5 reviews the policies implemented in a sample of seven countries plus the European Union. Finally, building on the previous chapters, Chapter 6 examines how industrial policies can foster the contribution of firms to the SDGs through their core business.

Figure 1.2. Structure of the book

Note: SDG = Sustainable Development Goal; UNGC = United Nations Global Compact; SDG-BAI = Sustainable Development Goals Business Actions Identifier; GVC = global value chain; ISIC Rev.4 = International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities Revision 4; HS6 = Harmonized System 6 Digit.

Box 1.1. CSR, RBC, CSV, ESG and the SDGs

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) (1960s) is a management concept that allows firms to take into account social goods, going beyond the goal of mere profit maximisation of shareholders. It gears firms towards considering social and environmental responsibility and its voluntary integration into their business, beyond charity, sponsorships or philanthropy. The evaluation of CSR activity is often conducted by the firm itself and is publicised through an annual sustainability report and/or a dedicated section on its website.

However, several initiatives help firms enhance and communicate their sustainability performance, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the UNGC. Other initiatives provide standards for reporting, thus reducing the cost for third parties to access the information and compare firms (GRI, Sustainability Accounting Standards Board [SASB], ISO 26000) (Box 2.1).

Responsible business conduct (RBC) (1976)1 are principles and standards that set out an expectation that businesses should avoid and address negative impacts of business activities, while contributing to sustainable development in countries where they operate. RBC means integrating and considering environmental and social issues within core business activities, including throughout the supply chain and business relationships.

Creating shared value (CSV) (2006), the concept introduced by Porter and Kramer (2006[7]) and Porter (2019[8]), distinguishes itself from CSR as a superseding and more narrow concept, emphasising the importance of jointly creating economic and social value, for instance by “reconceiving products and markets”, “redefining productivity in the value chain”, or “enabling local cluster development”. Given the broad definition and usage of the CSR concept by firms across countries, which is not necessarily directly linked to the business strategy, the authors argue that CSV is more directly linked to a firm’s profitability and competitive position in the market than is CSR. Some firms have progressively adopted the CSV concept and have used it to frame their contribution to SDGs (e.g. Nestlé (2021[9]) and section “How firms tackle SDGs in practice” in Chapter 2).

Table 1.1. Evaluation of CSR, RBC, CSV, ESG and the SDGs

|

Perspective |

Evaluator |

Evaluation targets |

Evaluation purpose |

Information availability |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CSR |

Firm |

Consumer, employee, investor or citizen through the information made available by the firm itself |

Firm |

Commitment to the community of stakeholders (consumers, employees, shareholders) |

CSR/sustainability report (Mostly based on informal evaluation and information provided by the firm itself.) Reporting frameworks and platforms (ISO 26000, GRI, UNGC, Sustainability Accounting Standards Board [SASB], Voluntary Principles, SDG Compass…) |

|

RBC |

Multinational enterprise |

Firm’s stakeholders through the information made available by the firm itself |

Multinational enterprise |

To anticipate and prevent or mitigate negative impacts of businesses |

Due-diligence report |

|

CSV |

Firm |

Consumer, employee, investor or citizen through the information made available by the firm itself |

Firm |

To legitimise business by measuring societal value created |

Annual report or sustainability report of individual firms |

|

ESG |

Investor |

Investors, financial institutions, notably through specialised rating agencies |

Firm |

Screening for potential investments, active ownership by institutional investors |

Rating agencies (through ratings or benchmarks) |

|

SDGs |

All kinds of stakeholders including firms |

In general: Anyone For firms: Consumer, employee, investor or citizen through the information made available by the firm itself |

All kinds of stakeholders including firms |

In general: Measurement of progress towards SDGs targets and indicators For firms: Commitment to the community of stakeholders, or measuring firm’s contribution to SDGs |

Measurement of progress: Measuring distance to the SDGs targets (United Nations [UN], OECD) Firm involvement: CSR/sustainability reports, reporting platforms Prize winners: governments and NGOs (e.g. SDGs awards) |

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) (2006), is the concept widely disseminated by the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), defined as “a strategy and practice to incorporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions and active ownership” (PRI). Rating agencies, as a service provider to financial institutions, and investors as well as their target firms, all conduct the evaluation of the firms’ ESG practices. Beyond some degree of reporting standardisation, ESG gave rise to quantitative assessments of firms’ attitude and achievements, allowing the diffusion of sustainability concerns among financial institutions and investors.

Finally, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (2015) encompass key global challenges. It is a universal call to all kinds of stakeholders including firms, governments, households and NGOs to contribute to the achievement of 17 goals by 2030. With a broader coverage than the Millennium Development Goals (2000-15), they should allow firms in any industry to contribute, including non-listed and smaller firms that may consider themselves as outside the scope of ESG. Although the quantitative evaluation of an individual firm’s contribution to SDGs remains especially challenging, initiatives such as the UNGC serve as an international platform to publicise firm’s SDGs participation across countries. Governments and NGOs also promote SDGs by awarding prizes to the firms that have an outstanding contribution to SDGs (Chapter 5).

From the point of view of private companies, CSR, ESG and SDGs are inextricably interwoven (Table 1.1). CSR has integrated social and environmental concerns in firm’s business operations and provided a framework to act in a more socially responsible way. ESG has introduced a somewhat measurable assessment of firms’ contribution to environmental, social and governance factors. It has initiated the involvement of investors and financial institutions to direct more resources into sustainable business activities, although CSR measurement is not necessarily consistent across rating agencies and is rather focused on large ones. SDGs have been conceived as an overarching framework involving all types of stakeholders. While for some firms SDG and CSR are close substitutes, for some others sustainability is at the core of their business strategy and corporate culture (Ashrafi et al., 2018[10]). Beyond corporate responsibility, the contribution to SDGs is inherently linked to firms’ activities (see Chapter 2 for examples).

1. First edition of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD, 2011[11]).

Box 1.2. An overview of OECD work on the SDGs

The OECD is home to a number of initiatives and databases related to the SDGs. As part of its commitment to help implement the SDGs, the OECD endorsed an Action Plan that describes how the organisation can support their achievement (OECD, 2016[12]). It includes actions to “support countries as they identify where they currently stand in relation to the SDGs, where they need to be, and propose sustainable pathways based on evidence”, “reaffirm [the] role [of OECD] as a leading source of expertise, data, good practices and standards” and “encourage a “race to the top” for better and more coherent policies that can help deliver the SDGs”. This box lists the main initiatives under this aegis.

Measuring the distance to the SDGs’ targets

The OECD Well-being Framework (via its How’s Life publications (OECD, 2020[13])) provides a comprehensive view of what matters to people, the planet and societies. This Framework consists of 11 dimensions that are coherent with those in the SDGs, i.e. health, income and wealth, jobs, education, environmental quality etc.

As part of its commitment to help achieving the SDGs, the OECD developed a methodology to measure, for each country, the distance remaining to reach the SDG targets (OECD, 2019[14]), building on the How’s Life work. Measuring distance to the SDG targets allows for better identification of priorities, and where countries should focus their efforts. These measures are based on the UN list of more than 200 indicators. Work in OECD (2020[15]) further measures the distance to the SDGs at the region and city level. In addition, many cities and regions from the OECD have already improved and implemented policy recommendations – developed under the OECD Programme on A Territorial Approach on SDGs – that involved private sector in their 2030 Agenda.

Responsible business conduct

The OECD is home to the main international standard on RBC and has developed guidance to help businesses manage environmental and social risks in their supply chains. RBC principles and standards set out an expectation that all businesses – regardless of their legal status, size, ownership structure or sector – should avoid and address the negative consequences of their operations, while contributing to the sustainable development of the countries where they operate. OECD work on RBC encompasses several work streams and legal instruments. The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD, 2011[11]) are the most comprehensive international instrument on what constitutes responsible business conduct. The Guidelines pertain to businesses operating in or from adhering countries, with the purpose to: ensure that business operations are in line with government policies; strengthen mutual confidence between businesses and the societies in which they operate; improve the investment climate and; to enhance the contribution of the private sector to sustainable development. Each adhering country sets up a national contact point tasked with promoting RBC and the Guidelines, as well as helping resolve issues in case the Guidelines are not observed.

A key element of RBC is risk-based due diligence – a process through which businesses identify, prevent and mitigate their actual and potential negative impacts, and account for how those impacts are addressed. RBC expectations are prevalent throughout GVCs and increasingly in international trade and investment agreements and national development strategies, laws, and regulations. The OECD has set out due-diligence guidance in several sectors to help businesses implement RBC principles and standards in their supply chains.

More recently, the OECD published a report in collaboration with the International Labour Organization, the International Organization for Migration and UNICEF to explore how child labour, forced labour and human trafficking (SDG Target 8.7) are linked with economic activity in global supply chains (ILO, OECD, IOM and UNICEF, 2019[16]).

Foreign direct investment quality indicators

As part of the OECD Action Plan on the SDGs, an FDI Qualities Toolkit was developed to measure the sustainable development impacts of foreign direct investment (FDI) on hosting countries. It highlights areas where FDI may have a positive impact towards achieving the SDGs, focusing on five themes: productivity and innovation, employment and job quality, skills, gender equality, and carbon footprint (OECD, 2019[17]). The Toolkit will allow policymakers to engage in detailed national or regional assessments to identify policies that harness FDI’s potential for progress towards defined priorities.

Business for Inclusive Growth

Business for Inclusive Growth (B4IG)1 is a platform developed by the OECD and business leaders to unite actions by businesses and governments around a common agenda for inclusive growth. B4IG plays an important role in advancing the G7 agenda to strengthen equality of opportunities; reduce income and gender inequalities; promote diversity and inclusion; and commit to advancing human rights in direct operation and supply chains. It focuses its actions around three key pillars: 1) advancing human rights in direct operations and supply chains; 2) building inclusive workplaces; and 3) strengthening inclusion in company value chains and business ecosystems. In addition, the coalition agreed to advance an impact measurement agenda that would seek to identify key metrics capturing the B4IG goals.

The Platform will also serve as an “incubator” for businesses and governments to test new policies and ideas to promote inclusive growth. Through a web portal and regular workshops and conferences, it provides a virtual and physical space to discuss, experiment, and test new ideas and policies on corporate governance models, business impact metrics and accounting standards, programmes and activities, and public-private partnerships.

Note: Parts of this box are taken from Shinwell and Shamir (2018[18]), “Measuring the impact of businesses on people’s well-being and sustainability: Taking stock of existing frameworks and initiatives”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/51837366-en.

References

[5] Altenburg, T. and D. Rodrik (2017), “Green industrial policy: Accelerating structural change towards wealthy green economies”, in Green Industrial Policy: Concept, Policies, Country Experiences, UN Environment, Geneva; German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, https://j.mp/2wULvlo.

[10] Ashrafi, M. et al. (2018), “How corporate social responsibility can be integrated into corporate sustainability: a theoretical review of their relationships”, International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, Vol. 25/8, pp. 672-682, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2018.1471628.

[2] Criscuolo, C. et al. (forthcoming), “An industrial policy framework for OECD countries: Old debates, new perspectives”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers.

[16] ILO, OECD, IOM and UNICEF (2019), Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains, https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/Ending-child-labour-forced-labour-and-human-trafficking-in-global-supply-chains.pdf.

[3] Larrue, P. (2021), “The design and implementation of mission-oriented innovation policies: A new systemic policy approach to address societal challenges”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 100, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/3f6c76a4-en.

[4] Mazzucato, M. (2018), “Mission-oriented innovation policies: challenges and opportunities”, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 27/5, pp. 803-815, https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dty034.

[9] Nestlé (2021), “Contributing to the global goals”, https://www.nestle.com/csv/what-is-csv/contribution-global-goals.

[15] OECD (2020), “A territorial approach to the sustainable development goals: Synthesis report”, OECD Urban Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e86fa715-en.

[13] OECD (2020), How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-Being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9870c393-en.

[17] OECD (2019), FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the Sustainable Development Impacts of Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/fr/investissement/fdi-qualities-indicators.htm.

[14] OECD (2019), Measuring Distance to the SDG Targets 2019: An Assessment of Where OECD Countries Stand, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a8caf3fa-en.

[12] OECD (2016), Better Policies for 2030, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/Better%20Policies%20for%202030.pdf.

[11] OECD (2011), OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, 2011 Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264115415-en.

[8] Porter, M. and M. Kramer (2019), “Creating Shared Value”, in Lenssen, G. and N. Smith (eds.), Managing Sustainable Business, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1144-7_16.

[7] Porter, M. and M. Kramer (2006), “Strategy and society: the link between corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 84/12, pp. 78-92.

[1] Ranjbari, M. et al. (2021), “Three pillars of sustainability in the wake of COVID-19: A systematic review and future research agenda for sustainable development”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 297, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126660.

[18] Shinwell, M. and E. Shamir (2018), “Measuring the impact of businesses on people’s well-being and sustainability: Taking stock of existing frameworks and initiatives”, OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2018/08, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/51837366-en.

[6] Tagliapietra, S. and R. Veugelers (2020), “A green industrial policy for Europe”, Bruegel Blueprint Series, No. 31, Bruegel, Brussels, https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Bruegel_Blueprint_31_Complete_151220.pdf.