This chapter explores how taking an integrated approach can help create more climate-resilient regions and cities. It highlights the unequal vulnerability of different places to climate change, their varying capacities to build climate resilience, the critical role of regional and local governments, and the interdependency of infrastructure systems across sectors and places. Addressing these challenges will require working together with regions and cities to build climate-resilient infrastructure by i) adopting a place-based approach; ii) harnessing multi-level governance; and iii) supporting subnational government finances. The chapter provides insights and case studies to help national, regional and local governments build climate-resilient infrastructure and communities.

Infrastructure for a Climate-Resilient Future

6. Building climate-resilient infrastructure with regions and cities

Abstract

Key policy insights

Climate change presents asymmetric challenges and opportunities across places. Vulnerability against climate change results not just from climate hazards but also from communities’ evolving social-economic characteristics. These features are unevenly distributed across space and can interact to create cascading and compounding effects. Investing in climate-resilient infrastructure can help communities build resilience against climate change and support long-term regional and urban development objectives.

Regional and local governments will play an essential role in building climate-resilient infrastructure. Subnational governments were responsible for 69% of climate-significant public investment in OECD countries in 2019. Subnational governments have the mandate to plan, deliver, fund and maintain climate-resilient infrastructure services and the local framework conditions for climate resilience investment.

This chapter presents three approaches that national, regional and local governments can take to support the delivery of climate-resilient infrastructure with regions and cities:

Adopt a place-based approach to help embed local characteristics in policies for building climate resilience. This involves targeting resilience actions towards the places most at risk, supporting systemic and integrated policy actions at a local level and engaging deeply with communities. For example, regions and cities can set up climate risk decision-making frameworks, develop climate-aware spatial plans and better communicate trade-offs around climate resilience.

Harness multi-level governance to help align climate resilience actions across levels of government. This can support climate resilience at the relevant scale by co‑ordinating actions across and among levels of government, and by reinforcing subnational government capacity. For example, regions and cities can set up contracts with each other and with national governments to co‑ordinate resilience across jurisdictions or to pool technical and fiscal resources to harness economies of scale.

Support subnational government finances to help regions and cities mobilise sustainable funding and financing resources for local climate resilience actions. This can involve ensuring access to appropriate revenue streams for resilience, mobilising finance to where it is most needed and unlocking climate finance at a local level. For example, governments can reform subnational fiscal frameworks to support self-funding, integrate climate resilience into intergovernmental transfer schemes and facilitate use of green, social and sustainable bonds.

6.1. Introduction

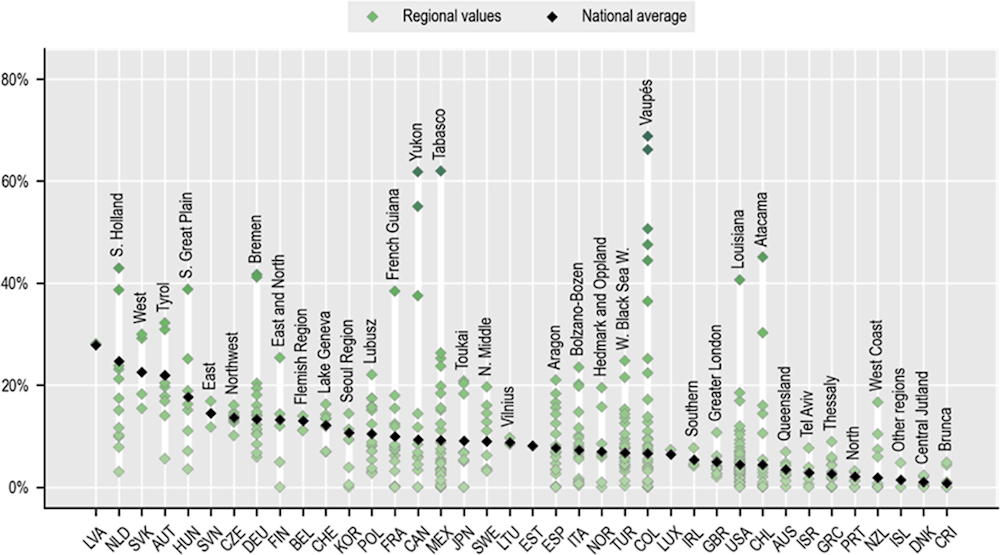

While climate change is a global phenomenon, its impacts are felt at a local level. Moreover those impacts are asymmetric, affecting different regions and cities differently. For example, across OECD countries, there are large gaps across regions within countries in the percentage of the population exposed to river flooding (Figure 6.1) due to differing geography but also human settlement patterns. Climate change can compound upon regions and cities’ differing physical, economic and social characteristics, capacities and vulnerabilities to create cascading effects (OECD, 2023[1]). In addition, climate change impacts are also influenced by, and depend upon, other factors. These include the complex interplay with other megatrends, such as demographic change, digitalisation and globalisation (OECD, 2022[2]).

Figure 6.1. Regions vary in their exposure to the impacts of climate change

Population exposure to 100-year river flooding in OECD large regions (TL2), 2015

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), A Territorial Approach to Climate Action and Resilience, https://doi.org/10.1787/1ec42b0a-en.

Regional and local governments are on the frontline of building climate resilience (Box 6.1). In many OECD countries, subnational governments have competencies for key areas related to climate resilience – from infrastructure provision and building permitting to land-use planning (OECD/UCLG, 2022[3]). Indeed, subnational governments are responsible for 63% of climate‑significant1 public expenditure and 69% of climate-significant public investment in OECD countries (OECD, 2022[4]). They have key responsibilities for building infrastructure resilience against both extreme weather events (such as cyclones) (UNDRR, 2015[5]) and slow onset events (such as rising temperatures) (UNFCCC, 2012[6]). The scale of the challenge for regional and local governments is large. Cities in emerging economies are estimated to need private investment of USD 29.4 trillion by 2030 to make their infrastructure and services more climate resilient (IFC, 2018[7]). Even though the costs are significant, the returns on investing in climate-resilient infrastructure can be high – every dollar invested in resilience could generate four dollars in benefits (World Bank, 2019[8]).

Resilience building and adaptation are not just about reacting to negative impacts but also about taking advantage of potential opportunities (OECD, 2022[2]; OECD, 2021[9]). The need for greater investment in both climate adaptation and mitigation infrastructure could provide opportunities for regions and cities to transform economically (OECD, 2023[10]). At the same time, climate change creates asymmetries across regions with respect to opportunities. For example, in the average OECD country, the gap between the regions with the highest and lowest share of green jobs is seven percentage points (OECD, 2023[11]). Whether dealing with challenges or opportunities, place-based solutions are needed to address the impacts of, and increase the resilience of, regions and cities to climate change.

Box 6.1. Actions for regional and local governments to build climate-resilient places

Regional and local governments can be “laboratories for innovation”, driving advancements in climate adaptation. These governments are responsible for many physical and operational actions needed to help build regional and urban climate resilience and meet broader development aspirations.

To build long-term climate resilience, regional and local governments should adopt a place-based approach by deploying a range of physical and operational actions tailored to their jurisdictions. While physical infrastructure investment will be essential, operational actions can sometimes be more effective and efficient to build resilience against climate hazards. Getting operational actions right also contributes to the resilience of infrastructure systems. To that end, it reduces asset exposure to climate hazards, which can in turn reduce the volume of physical infrastructure needed (and the associated embodied emissions).

Table 6.1. Key actions that regional and local governments can take to build climate resilience

|

Physical |

Operational |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Adaptation |

||

|

Reduce exposure to climate hazards |

|

|

|

Reduce vulnerability against climate hazards |

|

|

|

Mitigation |

||

|

Reduce incidence and severity of climate hazards (not focus of this report) |

|

|

Finance can have an important role to support investment in regions and cities (OECD, 2023[12]; OECD, 2022[13]). Most climate finance at a subnational level flows towards investments in mitigation rather than adaptation, although both are needed. In 2021, adaptation finance accounted for only 27% of total climate finance for developing countries (OECD, 2023[14]). At the subnational level, only 9% of climate finance flows for cities are being mobilised for adaptation and resilience projects; the remainder are directed towards mitigation or dual-use projects (Negreiros et al., 2021[15]).

Given the complex and decentralised nature of climate risks, building climate resilience and addressing challenges related to climate change will require adopting a place-based approach, harnessing multi-level governance and supporting subnational government finances. These are elaborated below and in Table 6.2:

Adopting a place-based approach can help target action to place-specific needs, build linkages across policy domains and develop community-appropriate solutions. This approach acknowledges the uneven spatial distribution of climate change risks and opportunities, and the need for co‑ordination across policy domains and community engagement. It calls for governments to consider the differing risks, capacities and aspirations of different places when designing interventions.

Harnessing multi-level governance can help co‑ordinate policy actions, support action at the right scale and harness competencies across all levels of government. This approach acknowledges that competencies are shared across levels of government. As climate change risks and opportunities cross jurisdictional boundaries, co‑ordinated approaches and local capacity are needed. It calls for governments to co‑ordinate vertically and horizontally to align priorities and responsibilities.

Supporting subnational government finances can help ensure that subnational governments have the fiscal capacity to invest in resilience, to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change and to leverage opportunities. This approach acknowledges the limited revenue potential of many local adaptation investments, limited local financial capacity and the insufficient flow of climate finance towards local adaptation projects. It calls for governments to recognise subnational governments’ constraints when designing funding and financing schemes to build resilience.

Table 6.2. Policy challenges and actions for building climate-resilient regions and cities together

|

Element |

Related policy challenges |

Related policy actions |

|

|

Place-based approach |

Uneven spatial distribution of climate risks, actions and costs Complex interactions across policy domains linked to climate resilience Strong community attachment to place |

>> |

Target responses towards places most at need to tackle the risks or leverage opportunities from climate change Support systemic, integrated and cross-sectoral policy action Develop solutions adapted for community needs |

|

Multi-level governance |

Competencies shared across levels of government Climate risks that cross jurisdictional boundaries Different characteristics and scales of infrastructure networks and solutions Insufficient capacity where it is needed |

>> |

Vertically co‑ordinate across levels of government to harness shared competencies Horizontally co-ordinate among levels of government to act at the relevant scale Build regional and local government capacity for resilience |

|

Subnational finance |

Limited revenue potential of subnational resilience investments Limited subnational financial capacity Limited climate finance adaptation flows towards subnational governments |

>> |

Identify alternative subnational revenue streams to fund resilience investments Target fiscal transfers to places where they are most needed to build long-term resilience Mobilise private finance for subnational governments, including climate finance |

The OECD Recommendation on Regional Development Policy and the OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment Across Levels of Government provide guidance on supporting the development of more resilient regions and cities (Box 6.2). These two recommendations take a holistic view of the factors that support long-term regional development and improved well-being, focusing on both physical and operational policy actions. The two recommendations highlight the importance of a place-based, multi-level governance and subnational finance approach for resilience.

Box 6.2. Place-based, multi-level governance and subnational approaches for resilience

The OECD Recommendation on Regional Development Policy provides countries with a comprehensive policy framework to support the design and implementation of effective regional development policies for inclusive economic growth, well-being, environmental sustainability and resilience. It outlines that regional development policy is long-term, cross-sectoral, place-based and multi-level, and helps improve the contribution of all regions to national performance and reduce inequalities between places and between people.

The OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment Across Levels of Government helps governments assess the strengths and weaknesses of their public investment capacity and set priorities for improvement. At the core of the Recommendation is a focus on a place-based and multi-level governance approach to investment, which can support countries to maximise investment returns. The Recommendation contains 12 principles that support better management and implementation of public investment across all levels of government.

Source: OECD (2023[16]), OECD Recommendation on Regional Development Policy, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0492; OECD (2014[17]) Recommendation of the Council on Effective Public Investment Across Levels of Government, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0402.

6.2. Integrated place-based approach for climate resilience

Adopt a place-based approach to target responses towards places most in need, address local risks and leverage local opportunities and support cross‑sectoral policy action that builds climate resilience jointly with local communities

A place-based approach acknowledges the role of place in shaping economic, social and environmental outcomes, including for climate resilience. Place-based policy solutions are tailored to the specific circumstances of different places. They consider the uneven and evolving distribution of factors such as natural resources, environmental hazards, human capital, social capital, connective infrastructure and governance institutions. As a result of their contexts, places not only experience different outcomes but also have different potentials, and different development pathways to reach them (OECD, forthcoming[18]).

6.2.1. Target responses to places most vulnerable to climate impacts

The increasing impacts of climate change are unevenly distributed across space. Climate change is increasing the risk of both natural and technological hazards. Natural hazards include flooding, rising sea levels, extreme heat, tropical cyclones, droughts and others (IPCC, 2021[19]). Technological hazards include grid blackouts, dam failures and others, which often result from the failure of critical infrastructure due to climate hazards (UNDRR, 2023[20]). While climate change is increasing risk across OECD countries (see Chapter 1), the magnitude of change differs greatly across places within countries. Potential hazards are spread unevenly across space. Moreover, the exposure of cities to climate change and their resilience against it also differ based on their physical, social and economic characteristics.

The impacts of climate change can compound existing vulnerabilities. Often, lower socio-economic communities are not just more vulnerable to, but also more exposed to, climate change. Among the global urban population, the poorest 20% have greater adaptation gaps than the richest 20% (IPCC, 2021[21]). The compounding and cascading impacts of climate change can hit disadvantaged communities the hardest. The systems they rely upon – economic (e.g., jobs), social (e.g., health care) and infrastructure (e.g., sanitation) – can already be less resilient to climate change (OECD, 2023[1]). For example, places with a shrinking population could have greater per capita costs to provide climate‑resilient infrastructure services (OECD, 2022[22]). Indeed, by 2040, 14 OECD countries are expected to experience a shrinking population, which will be especially concentrated in small- and mid-sized cities and remote regions. This could make building climate resilience even more challenging.

On the flip side, regions and cities can also harness opportunities presented by climate change. While climate mitigation is not the focus of this report, it is closely linked with resilience and can present economic opportunities (OECD, 2021[23]). For example, Nature-based Solutions, such as mangrove restoration, can offer both mitigation and adaptation benefits, on top of potential recreation, food and tourism value (see Chapter 4). Some regions are vulnerable to climate-related industrial transitions (OECD, 2023[10]). However, they can also leverage their existing assets, capacities and skills to reap green and digital dividends (OECD, 2023[11]). Regions with less frequent or severe climate hazards could see their relative attractiveness grow. Regions important to the green transition (such as those containing critical mineral deposits, advanced manufacturing capabilities or renewable energy resources) might have an advantage in attracting the investment and talent needed to build climate resilience (OECD, 2023[24]).

By understanding the spatial distribution of climate risk, place-based approaches can help ensure that policies are optimised to local characteristics and needs. They can proactively articulate resilient development pathways that enhance regions and cities’ competitiveness and help them specialise smartly, based on local strengths, challenges and aspirations (OECD, forthcoming[18]). This is especially relevant for developing countries given their vulnerabilities against climate change and ambitious development aspirations (see Chapter 5).

Regional and local governments play an important role in identifying and communicating climate risks. However, the exact impacts of climate change remain uncertain at the more granular regional and local levels in some countries due to data and modelling limits (OECD, 2021[25]). Indeed, a quarter of municipalities in the European Union do not assess the climate resilience of potential infrastructure investments (EIB, 2023[26]). Further, vulnerability assessments must consider local asset and population exposure against climate hazards, which requires detailed data (Aligishiev, Massetti and Bellon, 2022[27]). Exposure on its own does not necessarily imply vulnerability since many infrastructure assets are ‘protective’ (that is, they can reduce the exposure and vulnerability of other assets).

Given the scale of the challenge to build climate-resilient infrastructure, many regional and local governments will be unable to act on their own. Certain regional and local governments could face barriers in planning, financing or delivery. National governments will need to support regions and cities, targeting places that are most vulnerable to climate hazards and least able to respond on their own (OECD, 2023[28]; OECD, 2021[9]; OECD, 2019[29]; Matsumoto and Bohorquez, 2023[30]). Box 6.3 shows how cities are increasingly vulnerable to climate hazards, requiring urban-oriented solutions to build their resilience.

Box 6.3. Cities are increasingly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, but they are also drivers of resilience

Since cities contain a high density of people and assets, they are particularly exposed to climate hazards – the costs of inaction are high. Three in five cities globally with more than half a million residents are at high risk of natural disasters (UN, 2018[31]). Cities are affected differentially by climate hazards such as heat stress and rising sea levels. By 2050, over two-thirds of the global population could live in urban areas, with most growth in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Growing cities need to not only climate-proof but also significantly scale up infrastructure (IEA, 2023[32]), putting pressure on supply chains and capacities (Lall et al., 2021[33]).

Urban-oriented solutions can build cities’ resilience and mobilise their capacities for change. Coastal cities, for example, can take a blue urban approach to improve coastal management, protect natural ecosystems and reduce their vulnerabilities to disasters (Donovan, 18 May 2017[34]). A blue urban approach calls for water-sensitive urban development by acknowledging the interactions between terrestrial and aquatic areas of cities. While survey results show that cities expect the blue economy to help them create jobs, boost growth and adapt to climate change, they also demonstrate that climate change is the biggest threat to the blue economy (Lassman, 2022[35]). Developing resilient, inclusive, sustainable and circular blue economies will require a functional city basin approach to water resource management, highlighting the need for inter-municipal and urban-rural co‑ordination (OECD, 2022[36]). In the United States, cities could access over USD 21.7 billion in federal funding to build coastal resilience, climate-proof coastal infrastructure, protect coastal ecosystems and grow the blue economy (Urban Ocean Lab, 2023[37]).

Source: Matsumoto and Ledesema (2023[38]), Building systemic climate resilience in cities, https://doi.org/10.1787/f2f020b9-en.

All levels of government can support a more place-based approach for climate resilience and help deliver more climate-resilient infrastructure. To do so, governments can take the following actions:

Better understand the spatial distributions of climate hazards, exposures and vulnerabilities at a granular level to inform decision making. In the United States, the state of California has developed an online multi-hazard map to help residents identify the risk of climate hazards (California Governor's Office, 2015[39]). Multiple governments can also co-fund scenario‑based, multi-hazard modelling within their region to achieve economies of scale.

Define clear criteria for when resilience interventions should be made to prioritise limited resources. Governments can develop a multi-criteria decision-making framework based on climate risks and impacts to prioritise grant-making, lending and investment projects for the most effective actions. In Australia, the Resilient Homes Program in New South Wales defines grant eligibility criteria based on detailed flood mapping (Box 6.4). Criteria can also be published to strengthen subnational planning capacity and ensure investments are aligned across governments and with the private sector. Criteria can also be used to help define when and how to rebuild in – or when to retreat from – high-risk locations.

Consider strategic managed retreat options to reduce exposure to climate hazards and re‑direct funding towards development-oriented investment. In coastal areas exposed to rising sea levels or in areas at increased risk of flooding, governments and communities may avoid repeatedly rebuilding. This can reduce the potential for rising insurance costs by supporting communities to relocate. After repeated floods in the city of Lismore, for example, the Australian and New South Wales governments developed a programme to support managed retreat (Box 6.4).

Box 6.4. Resilient Homes Program of New South Wales in Australia

In early 2022, the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales (Australia) experienced devastating floods following heavy rainfall. In the city of Lismore previous flood records were surpassed by 2 metres. The heightened recurrence of such events due to climate change poses long-term challenges as communities need to recover from economic and social disruptions from infrastructure damage, property damage and community displacement.

In response, the Australian federal and New South Wales governments initiated the Resilient Homes Program. Overseen by the NSW Reconstruction Authority, the programme aims to reduce the number of homes in severe-risk flooding areas by offering federal and state financial assistance to homeowners. Recently released flood mapping and analysis classified areas with flood risks into four priority groups based on the likelihood and impact of potential floods. Homes in areas with the three highest priority groups are eligible for home buybacks, while those in the lowest priority group are eligible for home raising and retrofits. Home raising involves elevating or relocating homes above flood levels, while retrofits focus on upgrading and repairing liveable areas for increased resilience against future floods.

Through its proactive approach, the programme is reducing the concentration of homes in severe-risk zones, minimising potential damage and increasing flood resilience within the affected region. Around AUD 700 million has been allocated to finance home buybacks, raisings and retrofits. Property buybacks will be based on the market value of the home prior to the floods, while eligible homeowners can access grants of up to AUD 100 000 for home raising and up to AUD 50 000 for retrofits.

Source: New South Wales Government (2023[40]), Flood mapping and analysis released to support NRRC’s buyback priorities, https://www.nsw.gov.au/departments-and-agencies/department-of-regional-nsw/news-updates/flood-mapping-and-analysis-released-to-support-nrrcs-buyback-priorities.

6.2.2. Develop systemic and integrated strategies for regional and urban climate resilience

Climate change is a cross-cutting issue with complex, interlinked and varying place-based impacts. As climate change shifts the competitive advantages, challenges and aspirations of regions and cities, there is a corresponding need to update and future-proof development strategies and make the built environment more resilient. Given the essential role of infrastructure to help regions and cities meet their development goals, it is crucial to embed climate-resilient infrastructure into development strategies (OECD, 2023[16]). The links between climate change and other megatrends, such as demographic change, digitalisation and geopolitical competition, highlight the need to adopt an integrated approach. Climate resilience needs to be mainstreamed within regional and urban development strategies and plans more broadly (OECD, 2022[2]). Within these overarching strategies, infrastructure can be a tool to steer development in a more climate-resilient direction, and in doing so, make infrastructure itself more resilient. Failure to do so can have cascading effects, further hampering development efforts (Matsumoto and Bohorquez, 2023[30]).

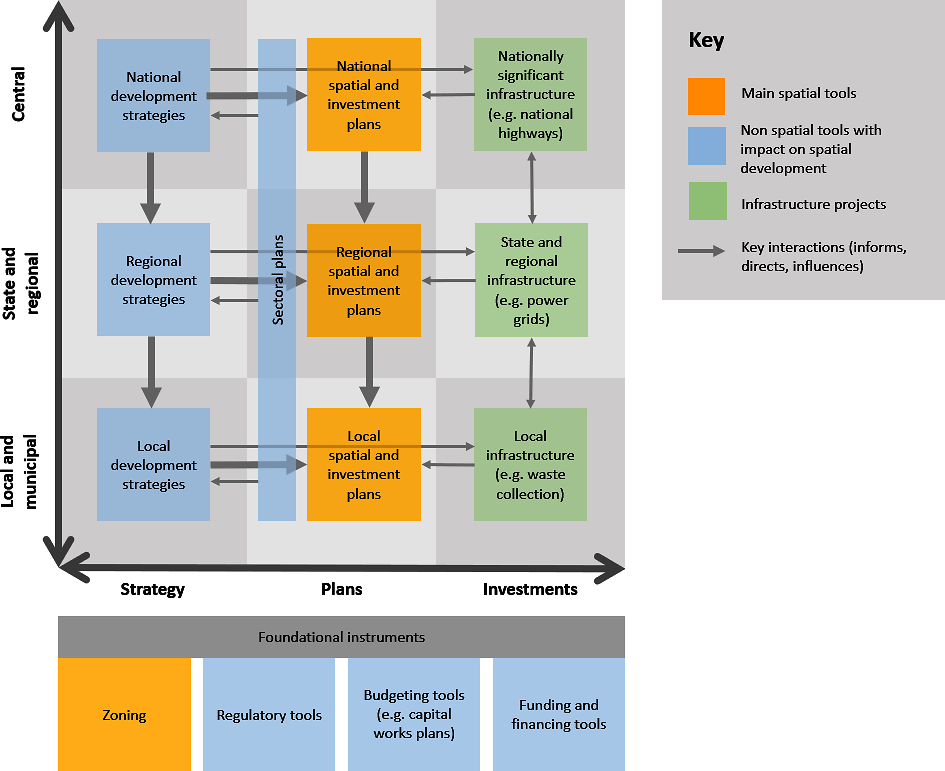

Making regions and cities more climate resilient requires adopting systems thinking and supporting integrated approaches (OECD/The World Bank/UN Environment, 2018[41]; OECD, 2023[1]). This means thinking of regions and cities as open systems, influenced by the interaction of both internal and external systems across various scales (Matsumoto and Bohorquez, 2023[30]). The complex interactions between infrastructure and other policy areas highlight the need to minimise conflicts and harness synergies across sectors and policy areas (WEF, 2022[42]), as well as avoid unintended consequences of resilience-building actions. This is often done most effectively at a local level. There are key links, interactions and feedback loops between development strategies, spatial planning, land-use policy and infrastructure planning (Figure 6.2). Governments need to think beyond individual assets to deliver climate-resilient systems by mobilising high-level strategies such as development strategies, masterplans, zoning, transit-oriented development and building regulations (OECD, 2023[12]). Once these strategies and plans define opportunities for creating resilient infrastructure projects, governance processes for planning individual infrastructure projects can be strengthened (see Chapter 2).

Figure 6.2. Development strategies, spatial planning and infrastructure planning are inextricably linked

Typical typology of development, spatial and infrastructure plans in OECD countries

Note: National-level plans are not always present in federal country (where present, may primarily act as co-ordinating tool for state and regional plans). Regional-level plans are not always present in decentralised unitary countries.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, building on OECD (2017[43]).

Governments at all levels have policy tools to influence regional and urban development. Governments need to co‑ordinate both infrastructure delivery and maintenance, as well as future infrastructure needs, through three key actions:

Develop cross-sectoral regional and urban development strategies to provide a consistent overarching vision for supporting climate-resilient development. Development priorities should be consistent with climate-resilient objectives. In Singapore, for example, the government has mapped areas at risk of inundation during the development of its new Master Plan, which has informed the planning for the proposed “long island” to protect against rising sea levels (Box 6.5).

Develop spatial plans that discourage or prevent development and investment in areas exposed to climate hazards. Limiting development in flood-prone areas can reduce the amount of infrastructure exposed to floods (Box 6.4). Countries such as Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay are mandating environmental analysis of spatial and territorial planning to align land use with sustainability (OECD, 2023[44]).

Tailor regulatory frameworks to allow for the management of local climate impacts and empowerment of local actors. National building standards (such as homes to be built using wind-resistant materials) can be useful to set a common baseline for quality. However, these are not necessarily appropriate everywhere. In some cases, places experiencing higher or lower risk from climate hazards could strengthen or relax local regulations and building codes accordingly. However, there is a risk that less consistent regulatory standards could increase compliance costs.

Box 6.5. Singapore Long Island land reclamation

Singapore is exposed to rising sea levels due to its coastal and low-lying geography. An estimated 70% of land in Singapore sits less than 5 metres above sea level. The East Coast area has experienced multiple flooding events due to high tides, heavy rainfall and storm surges. Flooding could disrupt and damage essential infrastructure (such as the East Coast Pathway and Changi Airport) with potentially broader impact on Singapore and Southeast Asia.

To reduce Singapore’s vulnerability against rising sea levels, the “Long Island” concept proposes land reclamation off the East Coast. This would form a protective island, elevating land to create a continuous coastal defence. Coastal outlet drains would be redirected into a new freshwater reservoir with tidal gates and pumping stations. Stakeholder input and local community feedback are ongoing and helping to shape the development of these plans.

The “Long Island” would serve multiple purposes, offering coastal protection against rising sea levels and floods, and enhancing water resilience with establishment of the new reservoir. The initiative could also potentially add around 20 kilometres of waterfront parks, tripling the length of parks in the area and providing new recreational opportunities.

Source: Singapore Urban Development Authority (2023[45]), 'Long Island', https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Planning/Master-Plan/Draft-Master-Plan-2025/Long-Island.

6.2.3. Build resilience jointly with local communities

Working closely with local communities to deliver resilience-building solutions has many advantages. Local communities can provide insights and relationships that can make planning resilience-building actions more effective. Understanding stakeholders’ needs and preferences is essential for designing appropriate resilience-building actions and becomes particularly important when difficult trade-offs must be made (see Chapter 2). By engaging transparently with local communities from the very start of infrastructure planning, governments can help secure stakeholder buy-in, increase community confidence in the process and minimise risk of local opposition. This is especially important as climate change affects a broad swathe of society and can be political.

Governments need to consider the strong impacts of climate-resilient infrastructure on communities. Such impacts can be concentrated (e.g. decisions on where protective infrastructure needs to be sited can have negative local visual impacts). Actions such as managed retreat can be difficult given people’s attachment to place and communities. Nonetheless, managed retreat will be necessary in some places given the great risks and likely high costs of continuing to inhabit highly exposed locations. Designing managed retreat with affected communities can help ease the disruptive effects of resettlement, preserve shared ties and identities, and facilitate openness to new opportunities (Hino, Field and Mach, 2017[46]).

There are also intergenerational equity considerations. Insufficient climate resilience has a greater impact on future generations because they are likely to experience larger impacts of climate change. Yet current generations are necessarily the ones making decisions around climate resilience. This creates moral hazards for current decision makers to invest in less resilient infrastructure. They could benefit from potential immediate savings but would not pay the full cost of reduced climate resilience. Managing these trade-offs requires effective stakeholder engagement.

Governments need to strengthen engagement with local stakeholders across the infrastructure life cycle in three key ways to co-deliver resilience:

Seek diverse and representative inputs throughout the infrastructure life cycle but particularly when developing local spatial plans. Governments can assemble citizen panels that represent local socio-demographic characteristics. Hachioji City (Japan) is using digital technologies to make stakeholder engagement more inclusive and accessible (Box 6.6), especially for young people. This can be important because young people will likely be more exposed than older people to climate change over their lifetimes yet have historically been under-represented in stakeholder engagement. Consultation is also relevant when shaping overarching policies. Between 2018 and 2019, Peru consulted with Indigenous communities to develop its Climate Change Law, culminating in 152 agreements, of which 147 were successfully implemented (OECD, 2023[44]).

Support transparent engagement processes to help resilience policies be successful. Transparency can build public confidence in engagement processes and outcomes. For example, governments can publish submissions received during consultation as one way to limit the disproportionate impact (or “capture”) of special interest groups. This can prevent resilience-building actions being disproportionally directed towards the groups with the greatest capacity to engage. It can also help build public understanding of the issue at hand and encourage other stakeholders to have their say, especially if they do not feel existing submissions reflect their viewpoints.

Considering and communicating trade-offs during stakeholder engagement can support more productive discussions. There are rarely perfect solutions to building resilience against climate change. Governments need to communicate the inherent trade-offs involved in climate- resilient infrastructure to help communities make informed and practical decisions. For example, governments can develop and model scenarios to help communities understand the impacts of various resilience-building actions. Governments can also ask communities to rank the importance of outcomes (such as lower climate risk versus lower cost of resilience building) to better understand community priorities. Further, they can develop digital platforms for communities to explore alternative models of development (Box 6.6).

Box 6.6. Japan Project PLATEAU

PLATEAU is a 3D city open data platform covering 117 cities across Japan. It is a type of digital twin, or digital representation of physical objects. Led by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT), PLATEAU mapped administrative data held by local governments to spatial data. MLIT has collaborated with local governments, industry and academia to explore use cases, including mapping underground infrastructure, modelling climate policies and automating permit processes.

Digital twins like PLATEAU can help make public engagement more inclusive and interactive, leading to greater community buy-in. These tools enable innovative technologies, such as augmented reality, to support public engagement. Users can visit sites virtually, visualise proposed infrastructure and interact with others without having to travel. The use of innovative technologies can also increase participation of young people, who are often under-represented in community engagement.

Local governments across Japan have used PLATEAU to gather citizen voices during infrastructure planning. For example, the local government of Hachioji City in Tokyo ran a gamified workshop to generate and visualise redevelopment ideas for a brownfield site. Users found it convenient to visualise data and found the online environment conducive to productive discussion. The workshop attracted a diverse audience, with over a third of participants under 30 years of age (a demographic not typically engaged with traditional investment planning).

Beyond stakeholder engagement, cities are using PLATEAU to support a range of resilience-building actions. For example, Tottori City is using PLATEAU to simulate flooding scenarios and improve evacuation routes. Meanwhile, Nagoya is running thermal environment simulations to assess the impact of climate change on extreme heat and the urban heat island effect.

Source: Japane Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (2022[47]), XR技術を活用した市民参加型まちづくり, https://www.mlit.go.jp/plateau/use-case/uc22-015/

6.3. Multi-level governance for climate resilience

Harness multi-level governance to support resilience at the relevant scale, co‑ordinate actions across and among levels of government, and build local capacity

Multi-level governance refers to the complex public governance across and within several layers of government, which are constantly evolving (OECD, 2017[48]). Given climate resilience and infrastructure are shared responsibilities across and within levels of government, it is important to understand and improve multi-level governance systems to support effective climate resilience actions across all regions and cities (OECD, 2013[49]). Managing relationships between and within levels of government is important. Since policy competencies are almost always shared, poor co‑ordination threatens the effective delivery of climate-resilient infrastructure (OECD, 2014[17]). Key shared competencies often include spatial planning, sectoral regulation, pipeline selection, funding, project design, project delivery and maintenance.

Acting at the right scale is critical. The optimal scale of infrastructure depends on the complex interplay between infrastructure systems and local characteristics. All infrastructure systems need to be resilient to climate change. However, the right scale of action varies across infrastructure sectors and across different climate hazards, and they do not always match administrative boundaries. There can also be important interactions between jurisdictions. Actions in one place can affect climate resilience in another, as is the case with developments that impact a river system. Thus, there is a strong need for multi-level co‑ordination across levels of government.

6.3.1. Strengthen vertical co-ordination across levels of government

The cross-cutting nature of climate change calls for all levels of government to deliver climate- resilient infrastructure. The large number of, and complex relationship between, governments across local, regional, national and supranational levels can make aligning these efforts difficult. The encouraging progress of many governments in mainstreaming climate change creates a stronger need for inter-agency co‑ordination to align different sectoral and policy perspectives into a coherent unified vision. Further, governments often have different priorities, face different incentives and have different fiscal and planning capacities. Together, these can result in actions that work at cross purposes and do not harness synergistic opportunities (OECD, 2014[17]).

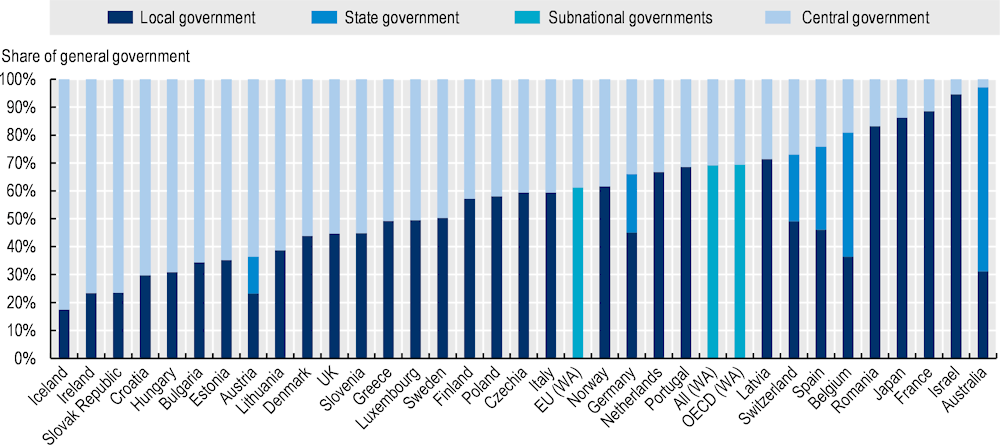

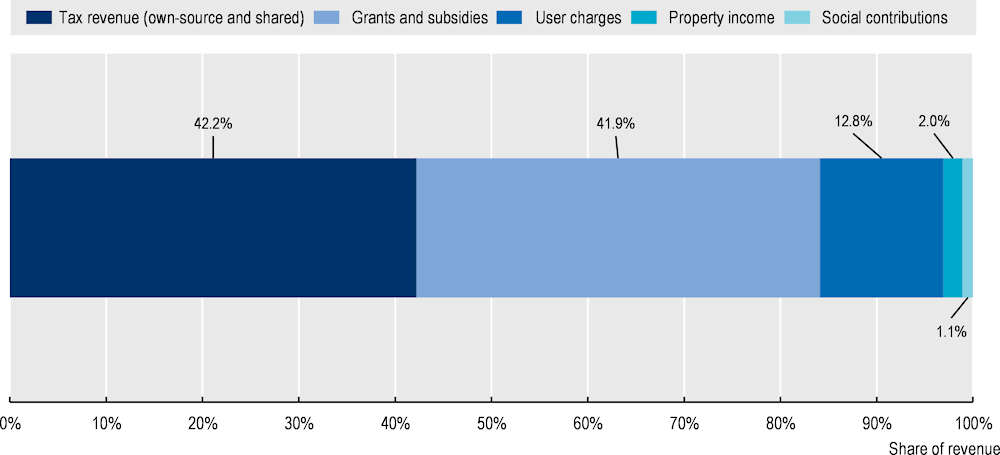

Vertical co‑ordination can help align climate-resilient infrastructure investments by supporting policy and investment coherence, resolving conflicts and mobilising shared competencies across levels of government. Governments in OECD countries share infrastructure policy and planning competencies across levels of government. On average, subnational governments undertook 69% of all climate-significant public investment in 33 OECD and EU countries in 2019 (Figure 6.3). Credible co‑ordination mechanisms with clear incentives can help maximise benefits and limit transaction costs. For example, setting up joint authorities could reduce set-up and overhead costs by sharing resources and capturing economies of scale. It is not always realistic to co‑ordinate on everything, but at the very least different levels of government should work together and not against each other.

Figure 6.3. Infrastructure policy and investment competencies are shared across levels of government

Climate-significant public investment by level of government in OECD and EU countries, 2019

Note: Climate-significant public investment includes both adaptation and mitigation finance. WA = weighted averages.

Source: OECD (2022[4]), Subnational Government Climate Finance Hub, https://www.oecd.org/regional/sngclimatefinancehub.htm.

All governments are responsible for vertical co‑ordination, which needs to be both bottom-up and top-down. Such co‑ordination is not limited to higher-level governments overseeing lower-level governments. It also includes harnessing the full set of mutually dependent competencies that do not exist in any single layer of government (OECD, 2019[50]). To strengthen vertical co‑ordination for climate resilience, governments can take the following actions:

Develop high-level climate policy to set policy priorities, guide policy making and align priorities across all levels of government. National governments can publish national climate resilience policy statements to set clear directions and objectives for the development and infrastructure plans of regional and local governments. For example, Germany adopted its first nationwide climate adaptation law in December 2023. The new law defines the strategic framework for future climate adaptation at federal, state and local levels. This framework aims to co‑ordinate climate adaptation at all levels and to enable progress across all fields of action. With the law, the German government also commits to pursuing a precautionary climate adaptation strategy with measurable goals (BMUV, 2023[51]). The Delta Programme in the Netherlands provides an example of both vertical and horizontal co‑ordination to build resilience against flooding and secure freshwater resources (Box 6.7). In Peru, the Ministry of the Environment is working with the regional governments of Cusco and Ucayali to update instruments, standards and plans for climate adaptation (GIZ, 2023[52]).

Adopt intergovernmental contracts to support co‑ordination across levels of government. Vertical co‑ordination can also take the form of intergovernmental contracts or deal-making between the central and subnational governments. In France, the government has developed a new type of contract with French inter-municipal groups to align policy priorities and advance green transition goals (Box 6.8).

Co-develop projects to harness joint competencies across levels of government to make the most of existing capacities. A regional and a local government might co-fund a feasibility study for a major infrastructure project. The regional government can provide technical expertise that might not be available at the local level. Meanwhile, the local government can provide the local networks and context needed for effective stakeholder engagement.

Consult and engage regularly to identify opportunities and bottlenecks. National governments can launch formal consultation processes with city and regional officials and residents to better understand climate-related urban and regional issues and secure political buy-in. For example, they can establish National Climate Change Councils, comprising representatives from both central and subnational governments, as well as other key stakeholders including civil society. Such Councils can serve as a platform for discussions, policy co‑ordination and collaborative decisions to address climate change challenges and implement effective climate policies. This can take the form of climate resilience task forces or dialogue forums. In Canada, the federal government collaborated with the provinces and territories to develop the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. This co-operation platform, introduced in December 2016, committed the governments to address climate change, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, foster clean economic growth and build resilience to climate impacts across the country (OECD, 2023[1]). In the Dominican Republic, the National Council for Climate Change and Clean Development Mechanism provides regular stakeholder meetings across government, utilities, business associations and civil society organisations as a means of co‑ordinating adaptation policy and action (OECD, 2023[44]).

Box 6.7. Netherlands Delta Programme

Much of the Netherlands sits on deltas, with around 55% of the country susceptible to flooding. Coastal and river floods could affect more than half of the population and two-thirds of economic activity (OECD, 2014[53]). Following the floods of 1953, the Dutch government introduced measures to protect the country more effectively from flooding. However, further action is needed to cope with the future impacts of climate change.

The Delta Act, adopted in 2012, established the Delta Programme, the Delta Commissioner and the Delta Fund. It advanced an adaptive governance approach to respond to the country’s current and future challenges on water safety and freshwater supply. It also aims to improve the system of flood defences with a vast programme of construction and land management – the Delta Works. The 2009 Water Act established four river basins as the basis for integrated water management. The Delta Act on Flood Risk Management and Freshwater Supplies, passed as an amendment to the Water Act, provides the backbone of the Delta Programme.

The Delta Programme is a national planning instrument with three objectives: flood risk management, freshwater availability and spatial adaptation. The Programme is a joint endeavour between the central government, provinces, municipal councils and regional water authorities, in close co‑operation with social organisations and businesses. It sits alongside the National Climate Adaptation Strategy as the core component of Dutch climate adaptation policy. The Delta Programme Commissioner oversees the Programme and updates plans every year.

The Delta Programme has an estimated annual budget of EUR 1.5 billion on average between 2023 and 2036. Around half of the budget is targeted at new investment and the other half for overhead, management and maintenance.

Source: Government of the Netherlands, (n.d.[54]) Delta Programme: flood safety, freshwater and spatial adaptation, https://www.government.nl/topics/delta-programme/delta-programme-flood-safety-freshwater-and-spatial-adaptation; IMF (2023[55]), Assessing Recent Climate Policy Initiatives in the Netherlands, https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400235849.018; OECD (2014[53]), Water Governance in the Netherlands: Fit for the Future?, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264102637-en.

6.3.2. Strengthen horizontal co-ordination across regions and cities

The impacts of, and solutions to, climate change do not always conform to administrative boundaries. Climate-resilient infrastructure cannot exist in isolation as insufficiently resilient infrastructure can have spillover effects across jurisdictions, potentially affecting areas with limited influence over said infrastructure. Local infrastructure failure could have far-reaching effects. This is especially the case in networked infrastructure, such as highways or electricity grids, where damage to a node could deteriorate performance across entire networks. Similar dependencies exist in shared water catchment areas.

The interdependence of infrastructure systems means that building climate-resilient infrastructure in one place and sector often requires actions in other places and sectors. This calls for horizontal co‑ordination across governments to improve the coherence of efforts to make infrastructure more climate resilient. In the United States, for example, the 2021 power crises in the state of Texas highlight both dimensions. A winter storm in Texas caused insufficiently weatherised natural gas power plants to fail. This, in turn, shut down parts of the natural gas network, leading to further power plant failures. Although the plant failures occurred in specific places, the connectivity of the Texas Interconnection caused price spikes and demand imbalances across the power grid. The event led to blackouts with vast economic impacts and loss of lives across the state (University of Texas at Austin Energy Institute, 2021[56]).

Strengthening horizontal co‑ordination across national and subnational boundaries is key to ensuring that infrastructure systems and networks are resilient. Horizontal co‑ordination often occurs between neighbouring jurisdictions but is beneficial between any governments with similar climate challenges and solutions. There is no one-size-fits-all solution since different places and sectors have different contexts that call for different co‑ordination approaches.

Governments can support horizontal co‑ordination and reduce co‑ordination costs through many mechanisms – from the simple (such as ad hoc meetings) to the complex (such as territorial reforms). Four potential actions are to:

Support peer learning through regular dialogue and co‑operation to build local knowledge. Local governments can convene regular forums to share experiences on building more climate-resilient infrastructure and co‑ordinate future investment plans.

Create forums for co‑ordination on specific climate hazards to seek shared solutions. Governments sharing a catchment network can meet regularly to identify the impact of climate risks across the catchment and identify shared solutions. Depending on the hazard, these can range from informal networks to formal and structured inter-governmental agreements. The Hamburg Metropolitan Region in Germany spans four federal states, creating an important need to co‑ordinate spatial planning and infrastructure investment across jurisdictional boundaries. In recognition of the need for collaboration, governments in the metropolitan region are developing an informal spatial plan for the entire region (OECD, 2024[57]).

Harness economies of scale by pooling planning and fiscal resources at the relevant scale. Governments within an urban functional area could establish joint water infrastructure authorities to streamline planning, funding and delivery of stormwater networks that are more resilient to extreme rainfall. Non-neighbouring jurisdictions can also pool fiscal resources, such as for insurance. In the Philippines, the Asian Development Bank supported the Philippine City Disaster Insurance Pool to provide rapid post-disaster access to pay-outs for local tiers of government by pooling disaster risk insurance (See Chapter 3).

Provide horizontal contracts to incentivise delivery and maintenance of critical infrastructure where there are local costs but regional benefits. Maintenance costs of a flood barrier may fall entirely upon one jurisdiction though it provides benefits to multiple jurisdictions. Governments along the watershed may compensate the government maintaining the flood barrier to ensure the asset is properly maintained. In France, contracts for the Success of the Ecological Transition require horizontal co‑ordination mechanisms to ensure policy actions at the relevant scale (Box 6.8).

Box 6.8. France: Contracts for the Success of the Ecological Transition (CRTEs)

The absence of an effective collaboration mechanism between different levels of government frequently undermines the successful implementation of policies and strategies. Overarching policies initiated by the central government may overlook the nuanced needs and priorities of local governments, requiring local authorities to adjust their specific actions to align with broader objectives. Uneven distribution of resources further compounds these challenges. This is because disparities in financial support, personnel and technical assistance can significantly affect the capacity of regional and local governments to design and enforce policies effectively.

In France, the Contracts for the Success of the Ecological Transition (Contrats pour la réussite de la transition écologique – CRTEs) provide a framework for local and municipal bodies to manage the co‑ordination challenges around territorial cohesion and the ecological transition. Initiated in 2020 by the government of France, CRTEs aim to promote collaboration between the central government, subnational governments, and local public and private actors. A steering committee of stakeholder representatives develops the contracts, which outline specific projects, objectives, financing plans and monitoring indicators. These priorities are defined locally but agreed upon with central government. When the contract is in force, inter-municipal co‑operation bodies can access project funding from a range of sources, including the Local Investment Support Grant, EU funds, relevant government ministries, the private sector and regional Conference des Parties.

CRTEs are designed to span six years, during which the steering committee monitors the annual progress of projects against pre-set objectives. An online toolbox provides guiding documents and indicative templates for each stage of the contract, enhancing transparency and awareness. CRTEs facilitate alignment of policies across different levels of governments, addressing the requirements of both national and local priorities. They promote not only vertical co‑ordination between national and subnational governments but also horizontal co‑operation among municipalities. Between 2021 and 2023, 847 inter-municipal or multi inter-municipal contracts were successfully implemented. In addition, CRTEs have led to innovative tools such as an ecological transitions compass (self-assessment tool) and territorial indicators that inform decision making and planning.

Source: OECD (OECD, 2022[58]), Subnational government climate expenditure and revenue tracking in OECD and EU Countries, https://doi.org/10.1787/1e8016d4-en; Agence nationale de la cohésion des territoires (n.d.[59]) Contrats pour la réussite de la transition écologique, https://agence-cohesion-territoires.gouv.fr/le-crte-un-contrat-au-service-des-territoires-et-de-la-mise-en-oeuvre-de-la-planification.

6.3.3. Scale up regional and local capacity to build climate resilience

Building climate-resilient infrastructure requires public and private sector capacity at a regional and local level. Many regions and cities already face capacity constraints (OECD, 2024[60]). Megatrends such as demographic change and globalisation threaten to further strain regions and cities’ capacities, with varying impact across places (OECD, 2022[2]). Climate change, for example, could shape regions and cities’ attractiveness, affecting their ability to attract public and private sector talent (OECD, 2023[24]). Capacity constraints are often most acute locally. This means that regional and local governments will have an essential role to identify, anticipate and tackle capacity gaps across both the public and private sectors.

There is room to further strengthen public sector capacity and expertise for climate-resilient infrastructure, especially in subnational governments. As the authority and responsibility of governments increase so does their need for capacity (OECD, 2014[17]). The significant role of many subnational governments in planning, regulating, consenting, funding, procuring and operating infrastructure highlights the need to reinforce subnational public sector capacity to cope with the increasing demand for climate-resilient infrastructure. Failure to do so could hurt the framework conditions needed to support climate resilience (OECD, 2014[17]) by, for example, delaying approval and consent.

Regional and local governments can face considerable barriers in building institutional capacity. Some governments operate in ageing regions with reduced labour supply and limited specialised skills. These governments might not be able to offer salaries competitive with the private sector. Smaller regions and cities in particular can find it difficult to acquire the diversity of competencies needed (OECD, 2014[17]). Boosting participation of under-represented groups, such as young people, women and minorities, remains a challenge in many places. However, it also offers opportunities to improve equity and expand the workforce needed to build climate resilience (Brookings, 2022[61]; OECD, 2023[62]).

The need for climate resilience is demanding new skills, roles and competencies. Yet these demands are neither uniform nor static. Instead, they depend both on the place-based impacts of climate change over time and the differing baselines of different places. Increasingly, regional and local governments are creating new roles, such as Chief Resilience Officers, to co‑ordinate resilience-building efforts within their jurisdictions (CEB, 2022[63]). Building long-term climate resilience will require investing in skills that go beyond knowing how to build resilient infrastructure (such as environmental engineering). They will also include skills needed for individuals and communities to cope with climate hazards (such as knowledge of which climate hazards are present locally) (OECD, 2023[64]). There is also a need to better understand the impact of emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and modular construction, on the types and volumes of skills needed to build climate-resilient infrastructure. Regions and cities will play a central role in providing the training, education and communication that is tailored to the place-based climate vulnerabilities faced by specific communities.

Implementing the vast pipeline of resilience-building actions will require boosting capacity in the private sector. Local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and innovative green start-ups can have a key role in infrastructure delivery and climate innovation. Therefore, there is a need to harness and strengthen climate competencies and local ecosystems to support green entrepreneurship (OECD, 2023[65]).

To build the capacity of regions and cities for building climate resilience, governments can take the following actions:

Support subnational governments to scale up their capacity to build climate-resilient infrastructure. National governments can provide grants to fund access of subnational governments to capacity building (such as through technical assistance from experts, experience-sharing with peers and creation of capacity-building facilities). In the United States, philanthropic organisations, such as the Local Infrastructure Hub and Accelerator for America, are helping train local government officials to deliver historic levels of investment (OECD, 2024[60]).

Pool and share capacity between governments to make the most of limited capacity. Regional governments can create public sector consultancies to provide on-demand technical assistance to local governments. This is especially useful for competencies that are important to retain but not necessarily used often at the local level. In Germany, the government-owned consultancy PD provides infrastructure advisory services to public sector clients throughout the country, including state and municipal governments. In 2021, Germany also launched the Climate Adaptation Centre to support municipalities and social institutions in designing and implementing climate adaptation measures (Box 6.9).

Co‑ordinate with each other and with the private sector to build market capacity. Governments can identify and share anticipated capacity gaps resulting from the planned infrastructure pipeline. This can help stakeholders identify required skills, as well as where and when they are needed, to meet the workforce demand required for climate resilience (OECD, 2024[66]).

Explore the role of Chief Resilience Officers to help mainstream and co‑ordinate climate resilience in governments. First created in 2013, Chief Resilience Officers (CROs) can help co‑ordinate planning and implementation of resilience building actions across government (CEB, 2022[63]). The Resilient Cities Network connects more than 200 CROs, policy makers and researchers in over 100 cities to advance urban-oriented resilience solutions (Resilient Cities Network, n.d.[67]).

Box 6.9. Germany PD in-house public sector consultancy and Centre for Climate Adaptation

It is important to develop public sector capacity at the right scale. Governments, especially smaller subnational governments, can find it challenging to justify permanent staffing for large but less frequently used competencies, such as digital transformation, large-scale procurement and major project delivery. These competencies are often outsourced to higher levels of government or the private sector. However, this can result in higher costs, reduced local knowledge and long-term attrition of local expertise. These pose significant challenges for building climate resilience given the specific skillsets demanded, especially with the volume of infrastructure investment needed over the coming decades.

PD, the German in-house consultancy of the public sector

PD, a consultancy owned by the public sector, advises public sector clients in Germany on infrastructure and modernisation. PD is jointly owned by 202 stakeholders, including 14 state governments and 132 local governments. The consultancy model helps build experience at scale within PD, which might not be possible for local governments. It also encourages cross-pollination of ideas across places and sectors. Since PD is partly owned by subnational governments, it can be more responsive to their needs and priorities compared with a fully nationally owned alternative. PD has advised on a range of projects contributing to climate resilience, including Brandenburg’s climate change adaptation strategy and Hamburg’s urban economic strategy (including an adaptation component).

Centre for Climate Adaptation

In 2021, the German Federal Environment Ministry launched the Climate Adaptation Centre (Zentrum KlimaAnpassung) to support German municipalities and social institutions in designing and implementing climate adaptation measures. Hosted by the German Institute of Urban Affairs and Adelphi Consult, it provides needs-based support to local actors such as municipal climate adaptation managers (a priority role supported by the new climate adaptation law). It has gathered experts from national government, subnational government, academia and civil society to pool institutional knowledge, including those tailored to the local level.

Source: PD (n.d.[68]), https://www.pd-g.de/en/; Zentrum KlimaAnpassung (n.d.[69]), https://zentrum-klimaanpassung.de/.

6.4. Subnational finance for climate resilience

Subnational governments have key responsibilities linked to climate resilience and are responsible for 69% of climate-significant investment. Thus, it is important to support subnational government finances to ensure these governments can generate funding and mobilise finance for local climate resilience actions.

Regional and local governments are important investors in climate-resilient infrastructure. In 2019, they undertook 69% of all climate-significant public investment in OECD and EU countries,2 equivalent to 0.4% of gross domestic product (Figure 6.3). They are directly responsible for setting policies and providing infrastructure and services in sectors related to climate resilience such as water, waste, housing, transportation and energy (OECD, 2022[70]). Further, regional and local governments carry out regulatory functions (such as land-use planning, project permitting and standard setting) that can influence both public and private sector efforts to build climate resilience.

Climate change could place fiscal stress on regional and local governments regarding both revenue and expenditure. Asset damage, property value loss, business disruption and community displacement from climate change could threaten revenues of subnational governments. Meanwhile, the need to recover from climate-related disasters and build resilience will require greater up-front expenditure, which is often shouldered by subnational governments (Gilmore, Kousky and St. Clair, 2022[71]). Ratings agencies view climate risk as increasingly important, with negative impacts on subnational governments’ access to finance (S&P Global Ratings, 2023[72]). In the United States, officials in the city of Miami noted how climate-resilient infrastructure can strengthen credit ratings (Cox, 2021[73]). Further, there are questions around the long-term sustainability of subnational government-backed insurance schemes supporting homeowners priced out of private insurance from climate risks (Smith, Mooney and Williams, 2024[74]).

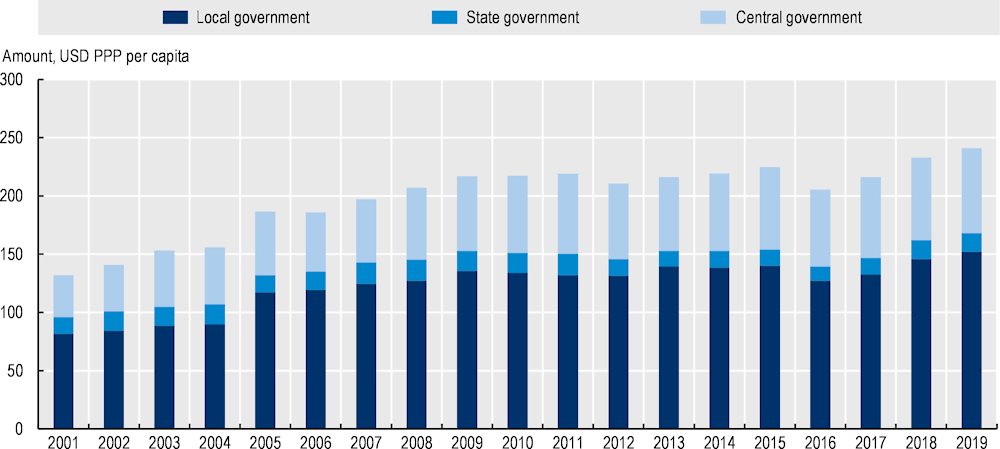

The amount of climate-significant investment has increased over the past decade but must further increase to meet climate resilience goals (Figure 6.4). In 2019, subnational governments accounted for 63% of climate-significant public expenditure and 69% of climate-significant public investment in OECD and EU countries (OECD, 2022[4]). However, subnational climate-significant investment remains relatively low compared to total subnational expenditure. In 2023, six in ten municipalities in the European Union reported their planned investment in climate-resilient infrastructure as insufficient; those in less developed regions faced greater uncertainty to increase investment (EIB, 2023[26]).

Regional and local governments have a key investment role but face more and different barriers to accessing funding and financing than national governments (OECD, 2022[13]). Investing in local climate resilience will require subnational governments to fund investment through a mix of self-funding and capital transfers, as well as by mobilising finance through borrowing (OECD, 2022[13]). Yet fiscal frameworks can sometimes limit the funding and financing capacity of subnational governments.

Subnational government debt sat at 19% of total public debt on average in OECD countries in 2021 (OECD, 2023[75]), with strong variation across countries and subnational governments. Already, many subnational governments are fiscally stretched. Indeed, one survey suggests that one in five councils in England could declare bankruptcy by 2024 due to lack of funding to maintain essential services (Local Government Association, 2023[76]). In many countries, these debt measures do not include potential contingent liabilities linked to climate change. Low fiscal capacity could limit the ability of governments to make needed investments for climate resilience, even where they are likely to have a positive economic impact in the long term. Yet the cost of inaction could be higher.

Figure 6.4. The increase in climate-significant public investment must continue to help regional and local governments improve climate resilience

Climate-significant investment by level of government in OECD countries, USD PPP per capita (real terms)

Source: (OECD, 2022[4]), Subnational Government Climate Hub, https://www.oecd.org/regional/sngclimatefinancehub.htm

Many essential local investments in climate resilience and climate-resilient infrastructure (such as flood protection, coastal protection and stormwater infrastructure) might not generate revenue. Investors are increasingly interested in climate-resilient infrastructure (The Economist, 2024[77]). However, private investment will not be sufficient to fund all resilience-building actions, particularly those that are not financially viable. Even after accounting for the savings in remedial costs of addressing climate impacts that new climate-resilient infrastructure can avoid, building climate resilience often generates net positive economic benefits (World Bank, 2019[8]). The gap between economic and financial viability means that governments can find it challenging to raise revenue to cover funding. This is especially the case because resilience benefits can be difficult to quantify or attribute to specific investments or beneficiaries (see Chapter 3).

The risk of revenue shortfall could have a strong impact on regional and local governments due to their smaller size and more limited revenue-raising powers. Many regional and local governments can increase funding through general taxation. However, this is not always appropriate (if the benefits are not broad-based) or feasible (if raising taxes is politically contentious or if fiscal frameworks do not allow for general taxation). Their smaller size, smaller asset bases, less diversified revenue streams and often more limited financial competencies compared to national governments can also increase financing costs for regional and local governments. The growing challenge of population shrinkage in many urban and rural areas in OECD and non-OECD countries is likely to put further pressure on the public revenues needed to fund climate-resilient infrastructure (OECD, 2023[78]). Meeting the scale of the local resilience tasks will require identifying appropriate funding avenues.

Climate-resilient infrastructure may have lower life-cycle costs (in part due to reduced risk of climate damages). However, it may also require greater up-front costs (in part due to higher initial capital expenditure) (See Chapter 3). The additional investment to make exposed infrastructure more resilient in developing countries is estimated at USD 11-65 billion per year (World Bank, 2019[79]). However, the net benefits could reach USD 4.2 trillion, with every dollar invested returning four dollars in benefits (World Bank, 2019[8]). This means that resilient infrastructure can require both greater up-front costs but also create greater long-term benefits relative to non-resilient infrastructure (see Chapter 1). As a result, subnational governments need greater funding and financing capacity to meet the greater up-front costs.

6.4.1. Seek alternative revenue sources and funding solutions for climate resilience actions

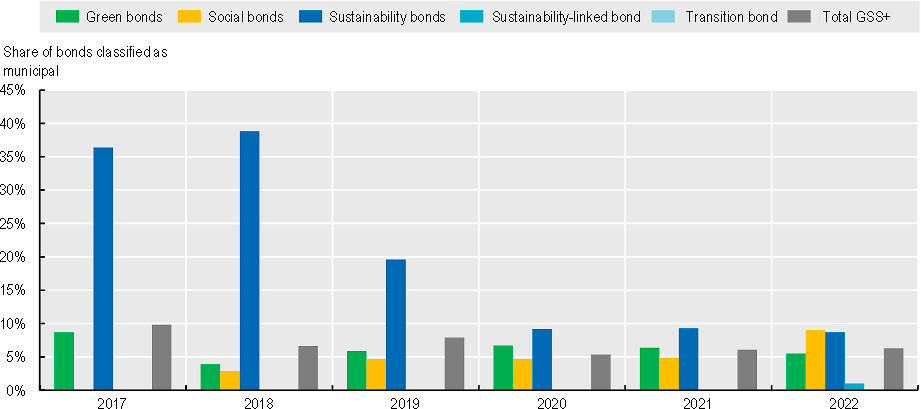

Subnational governments will need to mobilise a diverse set of funding instruments to fund investments in climate resilience. Across the OECD, most subnational government revenue comes from taxes (shared and own source), grants and subsidies from higher levels of government and, to a lesser extent, from user charges, fees and income from assets (Figure 6.5). Some governments also deploy “asset recycling” and “land value capture” to raise funding for new infrastructure (see Chapter 3).

Figure 6.5. Taxes, grants and subsidies account for over 80% of subnational government revenue in the OECD

Subnational government revenue in OECD countries by source, 2021

Source: (OECD, 2023[75]) , Subnational Governments in OECD Countries: Key Data, https://www.oecd.org/regional/multi-level-governance/NUANCIER%202023-3.pdf.

The type of instruments used and volume of revenue gathered vary substantially across and within countries, notably depending on the level of fiscal decentralisation. Regions and cities operate in different fiscal, regulatory and governance contexts, affecting their revenue-raising autonomy, decisions and potential (OECD/UCLG, 2022[3]). Diversifying revenue-raising sources can help regional and local governments build up their fiscal resilience and capacity to deliver climate-resilient infrastructure (OECD, 2022[13]).

Regions and cities will need to deploy innovative instruments to capture local revenue to boost funding and secure political buy-in for climate-resilient infrastructure. They also need to manage the fiscal impacts from demographic change, digitalisation and COVID-19, which can put pressure on the revenue‑raising instruments that regional and local governments rely on. Moreover, not all regions and cities have the same revenue-raising capacity. This means that fiscal transfers may be needed to build climate-resilient infrastructure, especially in disadvantaged regions, those with lower own-sourced revenue or those more in need of climate-resilient infrastructure (see next section).

A key question, therefore, relates to equity, fairness and how governments distribute the costs of climate-resilient infrastructure between people and places. In general, there are three approaches – user pays, polluter pays and progressive redistribution – but the appropriate mix will depend on local contexts (Figure 6.3). Climate-resilient infrastructure services could be more expensive to provide in places more exposed to climate hazards, but some view entirely cost-based charges as unfair (New Zealand Infrastructure Commission, 2024[80]). In turn, these raise the potential for solidarity mechanisms and equalisation systems to mitigate potentially higher costs for vulnerable communities. The costs and benefits of climate-resilient infrastructure do not necessarily align with local administrative boundaries. Therefore, questions also arise concerning shared costs across benefiting governments, regardless of the asset’s physical location.

Table 6.3. Pricing approaches to fund climate-resilient infrastructure

|

Approach |

Main source of funding |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Example instrument |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

User pays |

Those who use or benefit from the asset |

Horizontal equity, market efficiency |

Unequal access, potential under-provision |

Tariffs, congestion charges |

|

Polluter pays |

Those who have caused the need for the asset |

Justice, deterrence |

Might not be feasible, especially at global scale |

Environmental taxes |

|

Progressive redistribution |

Those who can pay |

Vertical equity, equality |

Inefficiencies |

Grants |

National, regional and local governments need to work together to ensure subnational governments have access to instruments to fund essential climate investments in regions and cities. Both traditional and innovative instruments can help mobilise alternative sources of revenue that are fair, equitable and sustainable. To do so, governments can take the following actions:

Ensure that fiscal frameworks provide appropriate sources of self-funding. National governments can ensure subnational governments’ revenue-raising powers are sufficient to meet their investment needs for climate resilience. Among other areas, they can provide flexibility to raise taxes, set localised tariffs and set regulatory guidelines that balance the needs for increased financing (vs. maintaining strong creditworthiness to reduce fiscal risks). This helps avoid these governments from having “unfunded mandates”.

Consider earmarked funding instruments for resilience building. Earmarking the proceeds of new revenue sources can help build public support for new revenue mechanisms and increase government transparency (OECD, 2021[81]). For example, regional governments can apply a levy on water rates that is hypothecated to projects that make the stormwater system more resilient to climate change. There could be specific earmarking of current ongoing expenditure to fund infrastructure operations and maintenance. Different climate-resilient infrastructure needs will likely require different funding solutions that are accepted by the community (Table 6.4).

Design land value capture schemes that help recover the cost of climate-resilient infrastructure in a spatially targeted way (OECD/Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, PKU-Lincoln Institute Center, 2022[82]). Municipal governments can uplift property rates near a transit corridor to help fund the delivery of the transit project, on the grounds that nearby property values are likely to increase as a direct consequence of the project. Local governments in Korea are charging developers for additional development rights, the proceeds of which are earmarked to local infrastructure improvement projects (Box 6.10).

Target current and capital expenditure to adaptation through green budgeting (Box 6.11). Green budgeting can help governments ensure their expenditure and investment projects support adaptation (OECD, 2022[70]). Long-term green budgets better match the long-term nature of climate resilience and can help “price-in” potential contingencies around climate losses and damages.

Table 6.4. Meeting different climate-resilient infrastructure needs will require mobilising different funding instruments

Illustrative examples matching climate-resilient infrastructure needs with appropriate funding solutions

|

Example of climate-resilient infrastructure |

Possible funding instrument(s) |

Rationale |

|---|---|---|

|

Climate-proofed electricity transmission connection to industrial customer |

User pays |