This chapter presents the framework used in the report to analyse the extent to which policies in Korea are supportive of innovation and structural change, and the extent to which they affect access to, and use of, natural resources for productivity growth and sustainability. It also gives an overview of the review’s findings on a wide range of policies and develops specific recommendations for related policy areas.

Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Korea

Chapter 1. Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

1.1. A framework for analysing policies for innovation, productivity and sustainability in the food and agriculture sector

Improvements in agriculture productivity growth are required to meet the growing demand for food, feed, fuel and fibre, and must be achieved sustainably through a more efficient use of natural and human resources and a reduction of pollution. A wide range of economy-wide policies affect the performance of the food and agriculture sector, and thus need to be considered alongside agriculture-specific policies. Recognising that innovation1 is essential to improving productivity growth sustainably along the whole agri-food chain, this report dedicates specific attention to the performance of agricultural innovation systems.

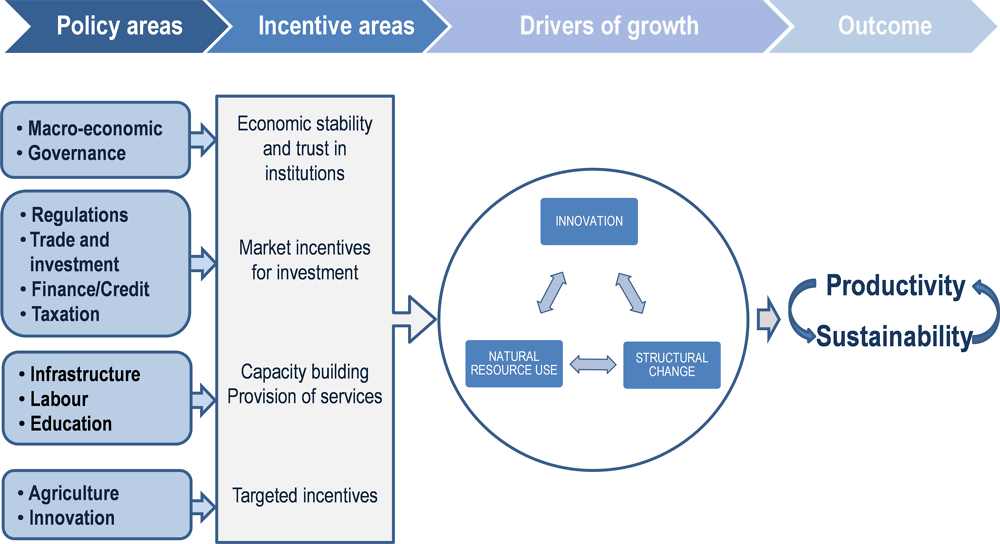

The policy review framework used in this report considers policy incentives and disincentives to the key drivers of sustainable productivity growth: innovation, structural change, and the environmental sustainability of agriculture (Figure 1.1).

This review begins with an overview of the characteristics and performance of the food and agriculture sector and the challenges it will face in the future (Chapter 2). A wide range of policies is then considered according to the main channels or incentive areas through which those policies affect drivers of productivity growth and sustainable use of resources.

The economic and institutional environment, both of which are essential to attract long-term investment (Chapter 3).

Capacity building, including provision of essential public services (Chapter 4).

Agricultural policy, domestic and trade related (Chapter 5).

The agricultural innovation system (Chapter 6).

This review draws on background information provided by the Korea Rural Economic Institute (KREI) and other experts, and on recent OECD agricultural, economic, rural, environmental and innovation policy reviews.

Throughout the report, the likely impacts of each policy area on innovation, productivity growth and sustainability are discussed, and recommendations are drawn on a large range of policy areas.

Figure 1.1. Policy drivers of innovation, productivity and sustainability in the food and agriculture sector

Source: OECD (2015).

1.2. Policy challenges for innovation, agricultural productivity growth and sustainability in Korea

Remarkable economic growth in Korea in the last four decades has been led by export-oriented industrialisation. In this process, the share of agriculture in value-added, employment and trade has diminished rapidly. The sector has been under pressure to meet changing domestic demand and to improve its productivity to offer farm households equivalent income to urban ones in a very limited time. At the same time, the policy environment has changed to increase the exposure of domestic producers to international competition; the GATT Uruguay Round Agreement on agriculture and various bilateral FTA agreements have been amongst the driving forces behind market opening. The societal demand on agriculture has diversified from focussing on stable supply of food to other functions of agriculture such as preservation of natural resource and ecosystem as well as traditional culture and rural landscape.

Korea also achieved higher productivity growth in primary agriculture than the OECD average for the last five decades, driven mainly by a declining labour input through rural to urban migration and farm mechanisation. Resource reallocation to more productive farms and commodity sectors has been the main driver of productivity growth, which has improved at the sector level but has been rather limited at the farm level.

Korea is one of the most land-scarce countries of the OECD. Per capita arable land (0.03 ha) is the smallest among OECD countries, giving the land-intensive crop sector a comparative disadvantage. Moreover, a fragmented land structure makes consolidation of cropland use particularly challenging. The concentration of land to large-scale farms has been slow. While more than 65% of Korean farms are less than 1 ha in size, the share of land cultivated by farms with more than 10 ha of land was only 14% in 2015.

Changes in the structure of the Korean agricultural sector were driven by a rapid change in the pattern of food demand. The “westernisation” of the Korean diet associated with income growth reduced per capita rice consumption and increased the demand for livestock products. While the value share of rice in agricultural production declined from 37% to 17% between 1970 and 2015, the share of livestock products increased from 15% to 43% during the same period. The operational size of livestock production units expanded rapidly to be comparable with EU member states.

Despite the declining share of primary agriculture in the economy, controlling environmental impacts of agriculture on natural resources remains important: the sector occupies 20% of total land area and accounts for almost half of total water withdrawal. Korea has reduced the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides, but the rapid expansion of intensive livestock production has made manure emissions the main agricultural source of water and soil pollution. The growing share of greenhouse farming has increased energy use in food production; the nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) surplus per ha in Korea remains one of the highest among OECD countries. Contamination and pollution of soil and water resources raises uncertainty about future productivity growth, as do climate change (which is expected to raise temperatures), the spread of pests and disease, and more frequent and more severe droughts and floods. Promoting sustainable use of land and water and increasing preparedness to climate change is an important policy agenda to assure long-term growth in agriculture.

Rapid industrialisation in urban areas and the migration of the young population from rural to urban areas have led to rural areas being economically left behind, resulting in higher income gap between farms and urban households. The level of the average farm household income declined to 65% of the average urban household income – one of the largest income gaps observed among OECD countries. Real farm income has been declining since the late 2000s as the growth in farm expenditure exceeds that of farm receipts. Increased off-farm income has been contributing positively to the incomes of farm households, but off-farm employment opportunities are limited in rural areas.

The farm structure in Korea will be further polarised between more productive large-scale commercial producers and less productive small-scale producers. For example, in the rice sector, farm-level productivity measurement shows that productivity growth is led by a small number of large commercial producers. Efforts to facilitate structural change in agriculture should continue, but agricultural policy should focus more on enabling commercially viable producers to improve productivity and sustainability performance at the farm level. Meanwhile, policy makers should recognise that sector-specific agricultural policies have a limited capacity to solve the low-income problem of small-scale producers. Policies covering economy-wide rural development and social security should play a more proactive role in addressing low income issues among rural households.

Future demographic change and slowdown of economic growth will have a significant influence on Korean agriculture from both supply and demand sides. Currently, 59% of farmers are over 65 years old, but the average age of farmers is expected to increase further. The domestic food market is unlikely to expand due to the declining and ageing population. Per capita consumption of rice nearly halved in just 25 years, and is likely to decline even further.

Given the limited demand growth in Korea’s domestic food markets, opportunity for future growth of its agriculture is increasingly dependent on access to export markets for high-value-added agro-food products. Here, Korea has the potential to develop its food and agricultural sector, including by producing high-value niche products for both the matured domestic market and growing markets in Asia. To assure the long-term health of Korea’s food and agriculture system, it is critical to increase its capacity to respond to market demands.

Despite declining domestic demand, Korea’s relatively small food manufacturing industry is growing rapidly. Its share in the overall manufacturing sector is much smaller than in other OECD countries and, dominated by small-scale firms, its labour productivity lags that of its competitors. Promoting the industry will be a particularly important policy area if the opportunities to produce value-added food products are to be exploited. The industry also has the potential to create employment in rural areas.

1.3. Developing an economic and institutional environment for fair and open competition

Korea has one of the most favourable macroeconomic environments among OECD countries, with the fastest growth rate of per capita income over the past 25 years. The Korean economy is highly dependent on exports, which account for more than half of the GDP. Korea also improved the governance of formal institutions and regulatory environment, which is a fundamental pre-condition both to encourage public and private investment in the economy and to enable those investments to achieve the intended benefits. Despite a series of deregulations, some entry barriers to agriculture remain, particularly in terms of ownership of farmland and investment in the corporations that own farmland. Promoting investment partnerships between producers and participants in the food supply chain (retailers, manufactures and others) is a key channel of innovation as it often allows farmers to respond to market demand and to introduce new technology, products or business models.

Korea maintains a relatively open trade and investment environment, although some restrictions remain in some sectors, including agriculture. Korea took a number of steps to liberalise foreign direct investment, reflected in the largest improvement in the OECD’s Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Regulatory Restrictive Index between 1997 and 2010. However, FDI in some of the agricultural sectors is still restricted and the FDI inflow to the food and agricultural sector is lower than most of the OECD countries. Korea has been actively pursuing bilateral and regional trade agreements and has developed both the physical and institutional infrastructure to facilitate trade.

Enforcement of fair competition has been a policy issue in Korea, particularly because the economy is dominated by conglomerate business groups. Ensuring a competitive environment in agricultural input and output markets is an important condition to provide competitive goods and services to meet the sector’s demand. Since its establishment in 1961, the agricultural co-operative (NongHyup, NH) has played a major role in supplying farm inputs and finance and has helped small scale producers to overcome their weak market position through collective activities. The government has been providing preferential tax to NH and uses it as a channel for subsidised credit programmes. However, with an increasingly polarised farm structure, NH is facing challenges to reflect producers’ diverse needs. The dominant position of NH in the supply of certain inputs (e.g. fertilisers) and financial services may hinder the entry of other players who could address the specific needs of large-scale commercial farmers.

Korea has a relatively well-functioning financial market and farmers have access to various financial sources, including emerging direct financing channels such as private investment funds. The government has been providing low-cost loans through NH. Although the government credit programme stimulated small-scale producers to invest in farm equipment, it may have led to over-investment, which subsequently constrained productivity improvement at the farm level and caused a structural farm debt problem after the financial crisis of the late 1990s.

Korea imposes relatively low tax rates on enterprises and provides tax incentives to encourage R&D investment. The tax incentive for R&D in Korea is particularly high and the share of tax expenditure in GDP in Korea is among the top group of OECD countries. The agricultural sector enjoys a number of tax benefits: primary agricultural products are exempted from value-added tax (VAT) and agricultural inputs including fertiliser, plant protection, farm machine and feed face either a zero VAT tax rate or are entitled to a VAT refund. In addition to reduced electricity charges for agricultural use, fuel tax is also exempted for certain farm machines. While those measures lower the production costs for farmers, such special treatment may encourage the overuse of potentially environmentally harmful inputs such inorganic fertilisers, chemicals and fuels. Moreover, it may discourage appropriate financial management of the farms in recording revenue and expenditure.

Recommendations to develop economic and institutional environment for fair and open competition

Remove the remaining restriction on the investment in agricultural corporations in order to promote innovation through vertical co-ordination in the supply chain and attract more private investment in primary agriculture.

Strengthen enforcement of the existing Anti-Monopoly law to ensure fair competition between the NH group and other private agricultural service and input suppliers. Accounting of NH’s banking service should be separated from the rest of its operations, including at the regional level.

Reform the tax system, which reduces the cost of agricultural inputs, to promote more sustainable agriculture and facilitate good financial management at the farm level. In particular, tax exemptions on some inputs such as chemical fertiliser, plant protection and fuel as well as reduced electricity charges may encourage the use of potentially environmentally harmful inputs.

1.4. Ensuring efficient and sustainable use of agricultural resources

Korea has developed a competitive transportation infrastructure and a particularly well-developed information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure. The government promotes the use of ICT through a “Smart Agriculture” project which targets the competitiveness of Korean agriculture. Collaboration between producers, retailers, R&D institutions and ICT industries is a key to developing ICT solutions to meet the demand of stakeholders and induce the adoption of ICT at the farm level.

The widening income gap between urban and rural area in the process of rapid industrialisation is a major policy concern. Structural change in the agricultural sector and diversification of income sources to off-farm employment have been the main pathways to addressing low income issues in rural areas. Despite government efforts to develop rural infrastructure and provide incentives to attract non-farm business activity to rural areas, young and skilled workers tend to leave such areas. Nonetheless, investment in rural infrastructure remains one of the key elements to attract non-agriculture industries to locate in rural areas. Increasing rural competitiveness and productivity requires a bottom-up approach to promoting integrated investments and public services that are geared to local needs (OECD, 2016a, 2018).

While economic diversification is one of the key strategies to increase the economic viability of rural areas, the food manufacturing industry has arguably more potential to create rural employment, add more value to primary agricultural production and open more possibilities to explore export markets and meet domestic demand for value-added products. The government should enhance vertical linkages between producers and downstream industries by removing the restrictions to invest in agricultural corporations. It should also promote the diversification of farm production activities into processing and marketing farm products.

Fragmentation of farmland is a major constraint to improving the productivity of rice farming and other land-intensive agriculture. This fragmentation is accelerating in Korea due to subdivision of farmland ownership through inheritance and land conversion to non-agricultural use. Meanwhile, the high price of farmland reflects its potential non-agricultural use-value in the future. This discourages farm consolidation and encourages land abandonment, as land owners have an incentive to maintain land for future conversion to non-agricultural use.

Despite policy efforts, concentration of land in large farms is slow in the crop sector. The strong protection of farmland ownership is based on the principle that cultivators should own farmland. This restricts farmland lease in all but exceptional circumstances. This strong restriction on leasing farmland discourages land owners from doing so on the basis of formal contracts. The area-based direct payment increases the incentive for the land owners to rent out land informally and receive payments. Meanwhile, informal land lease contracts are often unstable and short-term, which discourage stable farm management and long-term investment.

Farmers usually receive their irrigation water either from Korea Rural Community Corporation (KRC), a public company, or from the local governments. In regions where KRC provides irrigation water, there is currently no irrigation price and the water is free; in others, the price of water does not recover operations and maintenance charges, unlike in other OECD countries. This system encourages farmers to continue using water despite increasing water stress – already very high relative to other OECD countries – and demand from other sectors. It also reduces the incentive to adopt water-saving technologies to reduce unsustainable use of water in the face of climate change, as well as diversification of production away from paddy rice production.

Korea’s well-functioning labour market gives its agri-food sector the flexibility to adjust quickly to changes in labour- and skills needs, but the country will increasingly face labour shortage problems, including in the agricultural sector. The capacity of the agricultural sector to attract skilled labour from both domestic and foreign origins is crucial for its sustainable productivity growth. Promoting corporate organisational forms of agricultural operation will facilitate the entry of young generations from outside agriculture based on formal employment contracts.

A compulsory national pension system for farmers has only recently been introduced in Korea, where social protection of farmers is low and not at the same level as for other parts of society. The commodity-specific support to rice is providing some income security for older farmers – nearly 60% of rice farmers are over 65 years old – but this could be better achieved by a general social security system. The current support policy including market price support and direct payment programmes gives older farmers a strong incentive to continue farming and to delay farm succession. This is reducing the effectiveness of policies to facilitate the early retirement of aged farmers, such as the early retirement payment and farm pension programme. Policy coherence could be improved to provide consistent incentives to encourage the voluntary retirement of aged farmers and guarantee an income source for the retired farmers.

The intensity of expenditure for public education in Korea is one of the highest among the OECD countries. The government is also increasing investment in improving the quality of education in rural areas. While the enrolment rate to higher education reached 69%, the education system in Korea is degree-oriented and professional education for agriculture is attracting relatively less attention.

Recommendations to ensure efficient and sustainable use of agricultural resources

Promote partnerships between ICT industries and stakeholders in the food supply chain to develop demand-driven ICT in agriculture.

Provide more fiscal and regulatory authority to local governments and increase public investment to develop high quality rural infrastructure on education, healthcare and transportation to promote more integrated investments and public services that are geared to local needs, thereby attracting the relocation of non-agriculture industries to rural areas.

Reform the property tax system to provide incentives for the succession of farms to a single successor and to promote land transfer to younger farmers.

Impose higher property tax on unutilised farmland to promote efficient land use.

Facilitate formal land lease contracts by revising the farmland regulations to promote tenant farming and penalise undocumented land rental transactions.

Ensure that charges for water supplied to agriculture at least reflect full supply costs, and ideally cover the opportunity cost of water withdrawals. Consider targeted actions to increase the resilience of agriculture to future water risks associated with climate change, increased water demand and water pollution.

Speed up measures to control water pollution from agriculture, and further reduce point discharges from livestock enterprises, including through greater utilisation of manure.

Consider additional incentives in the National Pension (NP) system to promote early retirement and resource transfer to young commercial farmers, for example, in return for imposing age limitations to income support payments for rice farming.

Develop a policy environment conducive to voluntary retirement of aged farmers. The National Pension and basic old-age pension should also function as an income safety net for elderly farmers, instead of farm support payments.

Transform the agricultural education system to focus on skills required in the sector, and not only on formal qualifications.

1.5. Developing a coherent agricultural policy leading to long-term productivity growth and sustainability

According to OECD estimates, Korea grants one of the highest levels of agricultural support and protection to its farmers among OECD countries. While Korea increased investment in the agricultural knowledge and innovation system and introduced some income support payments which are decoupled from current commodity production, the overall portfolio of agricultural policy in Korea is largely dominated by measures linked to staple production and to supporting farm income. Korea has scope to further reallocate public resources towards investments to increase long-term productivity growth and sustainability in agriculture.

The level of producer support in Korea declined gradually from 70% of gross farm revenue in 1986-88 to 49% in 2014-16. However, policy measures linked to individual commodity production account for more than 90% of support to producers. This structure of support may constrain farmers’ responses to market signals, hinder structural adjustment of the sector toward production of more value-added products and increase environmental pressure from agriculture. Reform in agricultural policy to move away from intervention and towards encouraging flexibility in commodity production would facilitate structural change toward more market-oriented agricultural production.

A more open market environment is likely to increase the demand for tools to manage unexpected and unavoidable income shocks. A programme that offers payments in the event of a fall in commodity prices is currently in place for rice. However, such counter-cyclical support payments lead to an imperfect transmission of market signals to producers. If they are linked to specific crops, such measures tend to work against on-farm risk management strategies, including the diversification of production.

The agricultural insurance scheme has increased its commodity coverage to 74 agricultural products. However, the programme is highly dependent on government subsidies. The high level of insurance subsidies may lead to unsustainable choices of production and farm practices in the short term and to crowding out of better practices to adapt to changing climate in the long term (OECD, 2016b). In general, insurance subsidies risk crowding out market-based solutions and own-farm risk management strategies, and thereby transfer to taxpayers a part of the risks that should be borne by farmers (OECD, 2011). The subsidy rate should be gradually reduced for more commercially viable insurance products. The role of the private sector in providing agricultural insurance services can be enhanced by making the existing insurance database accessible to private insurance providers.

In Korea, income from the production of grains and other human food crops is exempted from income taxation, and income from plant cultivation is not taxed if the revenue is less than KRW 1 billion (USD 0.9 million). In addition to commodity-specific support, this preferential income tax treatment could impede resource reallocation towards more profitable and competitive non-grain agricultural sectors. Moreover, such exemption reduces farmers’ incentive to record and manage their farming business activities through bookkeeping. The lack of income tax records constrains the government to design more targeted policies to address low-income or income variation issues. For example, low-income farmers find it difficult to benefit from the income safety-net programme (National Basic Livelihood Guarantee, NBLG). In the absence of income tax records, the introduction of more targeted income-contingent payments or tax incentives to smooth income fluctuation is difficult to implement in Korea.

The majority of Korea’s farm households depend on income from off-farm activities. The low income of farm households is partly a consequence of limited non-farm employment opportunities in rural areas as well as low social security coverage. The issue of structurally low levels of farm household incomes should be addressed by a broader rural development policy to create more off-farm employment opportunities in rural areas. In addition, the general social security policy should function as an income safety-net for farmers in financial difficulty and increase the linkage to agricultural policy objectives. For example, the National Basic Livelihood Guarantee is a general social welfare programme in Korea, but only a very small number of farmers are covered by it; this is due to their ownership of agricultural production assets such as farmland, and the lack of income declarations that would allow for means-testing.

Korea has strengthened its environmental regulations and the stringency of its environmental policy is above the OECD average. The general environmental regulation system in Korea evolved from direct controls or command-and-controls in the 1980s to the combination of direct control and incentive systems since the early 1990s. Currently there is no environmental regulation imposed specifically on agricultural production, except for the regulations on livestock manure. Most of the regulations in the agricultural sector are regulations on products and processes such as regulations on food safety, labelling of origin, and traceability.

The design of agri-environmental policy requires the definition of reference levels, and environmental targets play a crucial role in choosing policy instruments. The reference level is the minimum level of environmental quality that farmers are required to provide at their own expense, and environmental targets represent a higher desired level of environmental quality. To establish a solid framework of agri-environmental policies, Korea should clarify the reference environmental quality as well as environmental targets which are well adapted to local ecological conditions. The subsidisation of chemical inputs for agriculture is not coherent with achieving agri-environmental policy objectives.

Livestock manure is the main agricultural source of water and soil pollution in Korea. Considering the future growth potential of the sector, improving the policy framework to manage livestock manure is a priority. A more comprehensive policy approach beyond regulation is also necessary: in this regard, the policy experience of the Netherlands in combining regulatory and economic incentives with a partnership of diverse stakeholders is particularly relevant.

Korea can give greater consideration to a wider set of policy instruments to promote environmentally friendly agriculture and preserve the ecosystem. So far, the country’s long-term plans to improve the agricultural environment have been implemented mainly through producer incentives. However, room remains to improve the environmental performance of the sector, especially given the high surplus nitrogen and phosphate levels, and the water-use intensity in agricultural production. Environmental policies should increasingly build on the “polluter pays” principle. Direct payment schemes should be decoupled from production decisions and reoriented toward measures to target explicit societal objectives, such as the provision of environmental services including water management, flood buffering and biodiversity.

Recommendations to develop a coherent agricultural policy conducive to long-term productivity growth and sustainability

Rebalance the portfolio of agricultural support to public investment towards long-term productivity growth and sustainability, such as more targeted support which encourages, or is conditional on, provision of environmental services (e.g. water management, flood buffering, biodiversity protection).

Gradually reduce border protection and commodity-specific support in a predictable way in order to allow markets play their role in allocating production resources to more high value-added niche products in which Korea has a potential export advantage and the domestic demand grows further.

Increase the role of the general social welfare programme (the National Basic Livelihood Guarantee) as an income safety net for farm households by adjusting eligibility criteria (e.g. excluding their agricultural production assets or requiring farm households to sell farmland to KRC and lease back).

Consider taking steps to induce farmers to declare income situation to facilitate the self-evaluation of the financial performance of the farm and to allow the government to design more targeted policies such as social welfare and income-based payments. The reform could begin with introducing an incentive measure such as making certain payments conditional on income declaration.

Evaluate the performance of the agricultural insurance premium subsidy to ensure it does not crowd out farmer’s own risk management strategy, and to monitor if it is hindering the development of agricultural insurance markets. The level of subsidy should be gradually reduced for more commercially viable insurance products, in order to increase the role of the private sector in providing agricultural insurance services.

Review existing agricultural policy instruments to improve their coherence with policy objective in order to reduce the conflicting incentives generated by different programmes. For example, policies to encourage early retirement have limited impacts as long as other policies such as market price support and direct payment create a strong incentive to continue farming.

Establish a framework of agri-environmental policies clarifying the reference environmental quality as well as environmental targets. Regulatory measures as well as a monitoring system should be applied at the farm level, clarifying the minimum (mandatory) levels of environmental quality with which farmers need to comply.

Apply economic instruments such as emissions trading schemes to reduce the intensity of chemical inputs and foster expansion of integrated nutrient management (such as nutrient accounting at the farm level); provide incentives to develop and disseminate technologies that improve fertiliser usage (e.g. nitrification inhibitors, cover fertilisers, etc.).

Take a multi-dimensional approach to manure management, including regulation, incentives to invest in developing new technology, capacity building and building partnerships between stakeholders. Enhance the partnership between livestock and crop farms to recycle and re-use livestock manure through on-farm application, biogas production and composting into organic fertilisers, and transport manure from livestock farms with a nutrient surplus to arable farms.

Formulate a roadmap with emission reduction goals and detailed measures to implement the 2030 GHG emission reduction target for the main emission sectors (rice and livestock). Set intermediate steps to track progress towards the targeted path and adjust measures if necessary.

Integrate climate change adaptation and mitigation as a cross-cutting aspect of agricultural and agri-environmental policies.

1.6. Establishing a more collaborative agricultural innovation system among public and private actors

Korea has increased public investment in agricultural R&D remarkably over time, and the intensity of this investment is one of the highest among OECD countries. This is reflected in its share of scientific publications in agriculture and food, which recently exceeded both OECD and EU15 averages. The country’s agricultural productivity and sustainability can benefit more from this high level of R&D investment.

Korea’s current agricultural innovation system (AIS) is characterised by the dominance of public actors such as public research institutions and public extension services, and the limited role of private research and technical advisory services. In some countries agricultural innovation is increasingly taking place in a network-based setting, in which a more inclusive, interactive, and participatory approach fosters greater innovation in response to emerging and pressing challenges facing food and agriculture systems. However, network analysis among AIS actors in Korea shows a weak connection between the private sector, producers and governments. The AIS in Korea should evolve to a more collaborative and demand-driven system between public and private sectors including higher education institutions.

Despite the establishment of the Science and Technology Commission of Food, Agriculture, and Forestry (STCA) as a co-ordinating institution, the complex public agricultural R&D system in Korea involving the Rural Development Administration (RDA), Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) and Korea Forest Service (KFS) is increasing the difficulty of co-ordination and collaboration between different public institutions involved in agricultural R&D at multiple administrative levels.

While Korea has the highest intensity of private R&D investment among OECD countries, its level of private R&D investment in agriculture is relatively low. Efforts were made to increase the participation of private enterprise in public R&D projects through a matching fund and a voucher system. However, the high level of public R&D investment may reduce the incentives for the private variety. The role of public agricultural R&D should be redefined so that it is concentrated more on the pre-competitive stage or on areas of public interest (such as long-term environmental sustainability), which are complementary to private R&D. Moreover, the tax incentive for private R&D in agriculture is much lower than other sectors as most farmers and agricultural corporations are exempted from income tax.

Another shortcoming of the top-down R&D system is that its outputs are not necessarily adopted at the farm level and do not address the practical needs of producers and food industries. The experience in OECD countries shows that enhancing the partnership between various public and private actors would increase the efficiency of public R&D investment and help secure contributions that are more adapted to both public and private needs.

As the farm population has become more diverse and produces more high-value-added niche products, the standardised services of the public extension system have limited capacity to meet producers’ needs. Although the government uses subsidies to encourage the use of private technical services, the development of those services is still limited. Extension services in some OECD countries have evolved to a more competitive system that mixes both public and private providers and is demand-driven, more pluralistic and decentralised. Korea’s public extension services should be reoriented towards issues of public interest such as animal disease prevention and environmental protection; this would allow more diverse private companies to provide services.

Recommendations to establish more collaborative agricultural innovation system among public and private actors

Strengthen STCA’s function as the R&D control centre of the sector to improve the co-ordination between RDA, MAFRA and APQA, and to evaluate public R&D projects.

Allow the participation of a wide range of stakeholders in public R&D planning and evaluation processes to reflect their technical demands.

Concentrate public R&D activities more on areas of public interest such as environment and resource conservation, and on areas where the private sector would under-invest, such as basic and pre-competitive applied areas of research, and commercially less viable commodities.

Promote collaboration between different actors in the agricultural innovation system. Public agriculture R&D projects can increase their conditionality on collaboration with the private sector, higher education institutions and other public R&D institutions. Joint research projects with non-agricultural research institutes should also be facilitated to combine science and technology in agriculture and other fields.

Enhance the agricultural R&D capacity at the local level by establishing a public-private council for regional agricultural technology innovation and improve the co-ordination between the central and local governments through co-funding schemes.

Reorient the public extension system towards providers of technical services that private organisations have less incentive to provide, such as promoting sustainable production practices, thereby leaving more room for private technical service providers, intermediary organisations such as farmers' co-operatives and industry associations in transferring technologies, capital and information.

Increase the exploitation of interactive learning to expand the innovation capability of farmers. Promote participatory test-farm projects with public R&D institutions and universities to increase linkage and share experiences among farmers.

References

OECD (2018), Rural 3.0. A Framework for Rural Development, Policy Note, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/Rural-3.0-Policy-Note.pdf.

OECD (2016a), OECD Regional Outlook 2016: Productive Regions for Inclusive Societies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260245-en.

OECD (2016b), Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in the United States, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264264120-en.

OECD (2015), “Analysing Policies to improve agricultural productivity growth, sustainably: Revised framework”, www.oecd.org/agriculture/policies/innovation.

OECD (2011), Managing Risk in Agriculture: Policy Assessment and Design, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264116146-en.

OECD and Eurostat (2005), Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, 3rd Edition, The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264013100-en.

Note

← 1. The Oslo Manual defines innovation as the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), or process, a new marketing method, or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations (OECD and Eurostat, 2005).