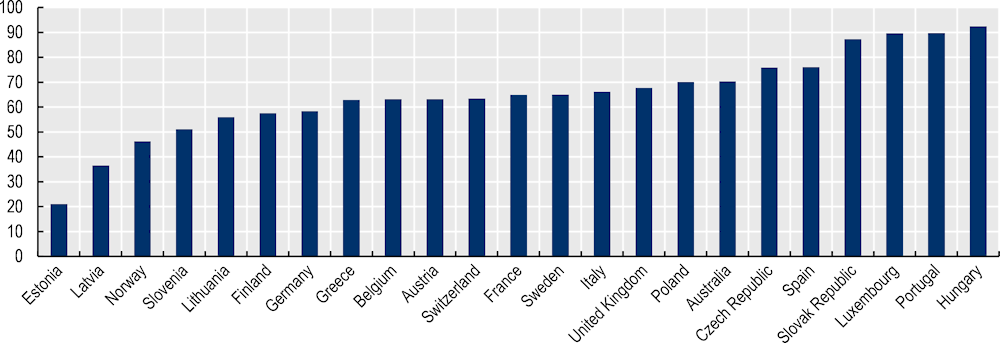

Working knowledge of a host country’s language is the tool that allows migrants to participate fully in host-country society. Without competent levels of language learning, other important masteries will elude migrants; thus, language is arguably the most important host-country related skill for migrants to develop. Speaking the host-country language allows migrants to access services and communicate their needs effectively. To succeed on local labour markets, migrants must be able to communicate with employers, hiring managers, and colleagues. Language also plays an important role in the creation of community and a sense of belonging. Immigrants who speak the host-country language have greater social contacts with native speakers and are more likely to pursue higher education opportunities than immigrants with little or no command of the host-country language.1 While there is little comparative information available on language mastery of immigrants across the OECD, 2014 data for European OECD countries and Australia show that two-thirds of foreign-born in the EU state they have at least advanced proficiency in a host-country language. In Australia, where two in five migrants have English as their mother tongue, the share is even higher, at 70%. However, the shares vary from about 20% in Estonia to about 90% in Hungary, Luxembourg, and Portugal (Figure 1).

Language Training for Adult Migrants

Introduction

Why is language training for adult migrants an important issue?

Figure 1. Advanced host-country language proficiency (percentages of foreign-born 15-64 year-olds, 2014), European OECD countries and Australia

In all countries, longer residence is associated with better knowledge of the host-country language. Across the EU, among recently arrived non-native speakers, attending a language course in the host country has been associated with an 8 percentage point greater likelihood of proficiency in the host language (OECD/EU, 2018). Not surprisingly then, language training is the principal component of introduction programmes for new arrivals and represents the bulk of government expenditures on immigrant integration in almost all OECD countries. Putting in place effective language training for adult migrants should provide a high return on investment, particularly in countries with a high share of humanitarian migrants,2 who often have little‑to-no proficiency in the host-country language. To be effective, however, training must be designed to match individual needs. Across the OECD, countries have become increasingly aware of the need to better integrate working-age migrants and seek to improve the capacity and performance of their language training schemes.

Speaking the host-country language is the single most important determinant for labour market integration

Although difficult to measure, it is generally conceived that mastery of the host-country language is the single most important characteristic that allows an individual immigrant to participate and succeed in the host-country labour market (OECD, 2018). Immigrants who speak the host-country language have significantly higher employment rates than those who report language difficulties – independent of the reason for migration and the level and origin of qualifications (Zorlu and Hartog, 2018). How well immigrants master the host-country language also determines whether and to what extent they can use their qualifications. After controlling for differences in other observable characteristics, immigrants in employment who have difficulties in the host-country language have over-qualification rates that are 17 percentage points higher than similar immigrants who speak the host-country language well (Damas de Matos and Liebig, 2014). Moreover, gaps in unemployment and employment rates between foreign and native‑born populations remain significant in most OECD countries, with some notable exceptions. Host countries have thus enacted a variety of measures to reduce barriers to labour-market insertion, with an increasing focus on language education.

To be effective, language training must be oriented towards labour market integration and reflect the unique challenges of adult language‑learning

Despite the importance of language proficiency for labour market integration, language training has often only limited association with labour market performance (Liebig and Huddleston, 2014). In part, this reflects the challenge of designing language programmes targeted to adults. For decades, research on language learning examined age in the context of “sensitive” or “critical” periods for learning, often concluding that adults could only rarely reach near-native proficiency. However, it has been more recently acknowledged that there is substantial variability among mature learners, and that there may be ways to better support adult language learning that employ a variety of learning techniques and acknowledge the impact of external factors (Kozar and Yates, 2019). Second-language learning is a complex process, especially for adults experiencing concurrent integration challenges. Adults not only are more instrumentally motivated than children, but also must balance competing demands on their time, specifically providing for themselves financially, and can be demotivated when the immediate benefit of learning is not apparent. Indeed, participating in language training might prevent immigrants from actively seeking or gathering work experience, which, in turn, sends negative signals to employers who tend to avoid job applicants with long absences from the labour market (Clausen et al., 2009). The additional months of non-employment are costly both for the migrant and the host country. One way to avoid such “lock-in” effects is to adjust the content and objectives of language training to labour market needs. Flexibility in the schedule and duration of language courses can also encourage more effective participation by adult migrants. Vocation-specific language training, ideally provided on the job, has proven highly effective in this regard (Friedenberg, 2014). However, to date, relatively few courses of this format exist in OECD countries, as such training tends to be costly and difficult to organise.

The purpose of this booklet

Designing effective language training is a challenging task. Whether or not immigrants make progress and can apply these skills to the labour market depends not only on how well language training is geared towards labour market integration. It also relies on the quality of available language learning options and on how well these are targeted to individual abilities and needs. Finally, success reflects immigrants’ motivation to learn and depends on the accessibility and affordability of available language learning options. This policy-oriented booklet guides policy makers and practitioners through the design and implementation of effective language programmes for adult migrants. The term adult migrant is used throughout this volume to describe foreign-born migrants, regardless of their motivation for migration, who arrived in their host country at an age that renders them ineligible for mainstream education, including language training (typically from the age of 18). Where countries have implemented programmes that apply solely to specific groups of migrants – such as humanitarian migrants or labour migrants – they have been so identified.

Drawing on experience from OECD countries3 and a number of empirical studies, this booklet presents 12 lessons and examples of good practice, which policy makers can use to increase the benefits of language training for immigrants, employers, and society at large. Several lessons focus on ensuring migrant participation in language courses, for example by ensuring access, even for settled migrants. Defining eligibility to participate in language programmes as broadly as possible will allow governments to reach a greater number of migrants. The timing of access is also important. New arrivals should have access to language training as early as possible so that they can effectively navigate their life in the host country. To motivate migrant participation, countries should design incentives rather than relying mainly on sanctions. Whereas incentive‑based policies can enhance migrants’ intrinsic motivation to learn, sanctions may have unintended negative effects. Affordability is also a consideration, as cost should not be an obstacle to language learning. Countries have taken a variety of approaches to this challenge, from providing language courses free of charge to using a deposit model in which migrants receive reimbursement upon successful completion of a course. Lastly, language training should be flexible and compatible with other life constraints. Adult migrants must fit language training into their day alongside job and child-care obligations. Policy decisions such as provision of childcare during classes can make this easier.

Later lessons are designed to help policy-makers improve the language courses themselves by developing programmes that meet the needs of the migrant population. Many language courses are not particularly relevant or sufficient for the realities of the labour market and thus do not meet the needs of a large number of migrants. To address this, language courses should be integrated with vocational training or designed in co‑operation with employers where feasible. Before placing migrants in a course, it is important to assess each learner’s level of education and capacity to learn. This will ensure to the greatest extent possible that migrants are placed in a course where they can be successful. Engagement with language specialists and non-traditional partners will broaden learning opportunities. Involvement of stakeholders outside the policy-making sphere, such as educators and private‑sector partners, improves quality and agility in developing new programming. Especially where several stakeholders – within and across levels of government – play a role, it is important to ensure co‑ordination between all relevant stakeholders and defining common standards. A central actor in charge of co‑ordination can ensure that standards are met efficiently and consistently. Governments can also encourage development of new technologies. While questions of equality of access must be considered, it is clear there is untapped potential in the trend toward digitalisation, particularly in how it allows governments to expand their course offerings and increase flexibility. To capitalise on these innovations, governments need to invest in teacher preparation and recruitment. Teacher shortages remain a barrier to ensuring all migrants have access to the language courses they need. To attract and retain more and better teachers, it is important to provide these professionals with the preparation and support they require to succeed in their roles, particularly in an increasingly high-tech environment.

Finally, both for questions of access and course quality, it is vital to evaluate the impact of language training on migrant integration. Given the substantial investment in language programmes for adult migrants in many countries, there is significant interest in knowing which practices achieve the best results. The final lesson of this booklet notes however that language programmes are rarely formally evaluated and provides considerations for conducting thorough, informative assessments of these programmes.

Notes

← 1. A recent study of the impact of Dutch-language learning in the Netherlands indicates that, controlling for endogenous factors, not only does Dutch proficiency increase the likelihood for migrants to enter employment by 30 percentage points, but it also increases their feeling of social integration even more, by 50 percentage points (Zorlu and Hartog, 2018).

← 2. The term “humanitarian migrant” typically refers to persons who have successfully applied for asylum and have been granted some sort of protection or have been resettled through humanitarian programmes outside the asylum procedure. For the sake of simplicity, this booklet considers all recipients of protection – be it refugee status, subsidiary or temporary protection – to be humanitarian migrants, given that the groups benefit from similar (and often identical) language integration measures.

← 3. Countries have taken a variety of strategic actions based on differing philosophies of integration (language and civics training versus work-first incentives, for example). Countries like the United States have historically preferred work-first incentives, leaving language training to local governments or the not-for-profit sector. Others, such as France (in 2007) and Germany (in 2005), have chosen to implement language courses alongside civics instruction. These positions reflect cultural differences, as well as differences in the makeup of each nation’s economy, and there is no one‑size‑fits-all policy response. For many OECD countries, however, there has been a gradual shift to a blended approach, combining language with work-first integration (Arendt et al., 2020).