The recovery from the COVID‑19 pandemic is likely to trigger job reallocation between sectors and occupations and, with it, a need to provide career guidance and advice to adults in need of upskilling and reskilling. But the crisis has also resulted in a sudden shift in much of the delivery of career guidance from in-person to remote. This policy brief describes the impact of the pandemic on the demand for and the delivery of career guidance, documents countries’ efforts to maintain provision of career guidance services during lockdowns, and explores the need to scale up career guidance going forward. Given the importance of career guidance in keeping workers’ skills relevant and improving the match between the demand and supply of skills, this brief also offers policy directions to improve its coverage, use and quality.

Leveraging career guidance for adults to build back better

Abstract

Introduction and key messages

Career guidance is defined as services that help workers of any age make meaningful educational, training and occupational choices and manage their careers (Cedefop et al., 2021[1]). Career guidance can be delivered by public bodies, such as Public Employment Services, education and training institutions or dedicated career guidance services, and it can also be delivered by private providers, such as employers or employer organisations and private career development professionals. Public services are generally free of charge while users may need to pay out of pocket for privately provided career guidance. Services aimed at adults are fundamental to respond to rapidly changing skill needs in the labour market and to promote learning throughout the working life (OECD, 2021[2]). With the COVID‑19 pandemic, career guidance has become much more prominent in policy agendas. Many adults will need to transition to different occupations and sectors as a result of increased job reallocation, increasing the need for assistance in identifying viable job transitions and relevant training (OECD, 2021[3]).

Based on two surveys, this policy brief looks at the effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic on the provision of career guidance for adults. Since the start of the pandemic, there has been an increase in the demand for career guidance services. At the same time, given the need for social distancing, the delivery of career guidance services has shifted towards fully remote delivery and most services have adapted. This switch towards remote career guidance is somewhat aligned with user preferences for more online chat, videoconferencing and instant messaging options for obtaining career guidance (OECD, 2021[3]).

Consequently, countries’ efforts have focused on improving online career guidance portals, setting up or strengthening remote career guidance services, or supporting career guidance practitioners to transition to telework. It is expected that changes along these lines will remain pertinent, as the use of online career guidance services is expected to increase significantly post-pandemic compared to the frequency observed prior to the pandemic.

Career guidance for adults will remain highly important in the near future while the labour market recovers. Practitioners and government officials believe it will be key to support re‑skilling and upskilling and to advise workers so their skills remain relevant. The COVID‑19 pandemic has shifted labour demand across sectors and regions and this may lead to a more permanent re‑allocation of jobs (OECD, 2022 forthcoming[4]; Buba et al., 2021[5]; Cueffe, 2021[6])). The scaling up of career guidance will be key to helping adults navigate these changes in the labour market and to make them aware of available upskilling and reskilling opportunities.

Key messages

The importance of career guidance to help identify training and sustainable employment opportunities has increased during the pandemic and is likely to remain high as the recovery brings about increased job reallocation.

During the pandemic, the demand for career guidance services increased and the delivery of career guidance shifted towards fully remote channels, which is somewhat aligned with user preferences. Some of these changes will be permanent.

Career guidance for adults can contribute to the labour market recovery by advising workers on means to reskill and upskill, so that their skills remain relevant and well utilised. This can be done by:

Providing both remote delivery and in-person delivery of career guidance services. Offering both channels maximises coverage, delivery through technology tools is more aligned with user preferences and remote delivery can reduce costs and improve service.

Keeping online portals up to date after the pandemic, as they can be effective career guidance tools and offer useful information.

Raising awareness of the usefulness of career guidance services, especially among low-educated and older adults, the unemployed and those living in rural areas, who are least likely to use formal career guidance.

Set up mechanisms that ensure that career guidance services are of high quality, such as by checking against quality standards, monitoring of outcomes of providers, using high-quality skills assessment and labour market information on skill needs or by professionalising career guidance advisors.

Ensure public funding to cover, at least partly, the cost of accessing career guidance, particularly in countries where free public provision is limited.

The use of career guidance during the pandemic

The COVID‑19 pandemic led to job loss for many adults, and was more severe for workers in some sectors than others. Not all of the jobs that were lost will be recovered as a result of the accelerated adoption of new technologies during the pandemic and changes in consumption habits and work preferences.

These dramatic developments to the labour market led to significant changes in the use and delivery of career guidance services. Two surveys quantify these changes: the OECD 2020 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA)1 and the 2020 Inter- Agency Working Group on Work-Based Learning (IAG-WBL) Career Guidance Survey2 (hereinafter referred to as IAG CG Survey).

During the pandemic and lockdown, most career guidance providers and policy officials reported a decrease in operations, likely due to the closing of face‑to-face operations. Only 15% of respondents reported an increase in career guidance operations, compared to over 70% of respondents who reported a decrease (IAG CG Survey).

In contrast, more adults used career guidance, either to navigate ongoing changes or because they had more time (SCGA).The changes in the use of career guidance imply an overall increase in the share of adults who use career guidance on an annual basis from 31% prior to the pandemic to 39% during the pandemic. The additional career guidance demand was most likely satisfied by adults searching for information through online platforms on their own, instead of virtual or face‑to-face one‑on-one career guidance services.

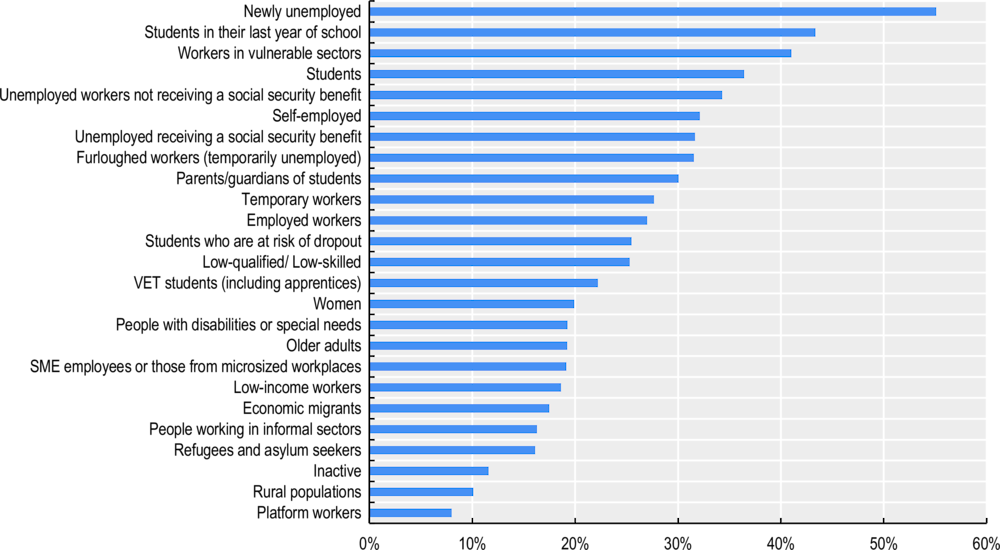

Newly unemployed workers were one of the groups for whom career guidance services demand increased the most (over 50% of respondents to the IAG CG Survey agree) (Figure 1). Other user groups who increased demand were students in their last year of school (43% agree) and workers in sectors, most affected by the pandemic (41% agree).

Figure 1. Likelihood that the demand for career guidance services increased during the pandemic, by group

Percentage of respondents who report that demand for career guidance services for a given user group has increased

Note: Average for OECD countries and for respondents who refer to guidance activities that predominantly involve adults or both adults and young people in educational institutions.

Source: Inter-Agency 2020 Career Guidance Survey.

Not all career guidance services experienced the same increase in demand. Career guidance users were interested mostly in labour market information (81% of respondents to the IAG CG Survey agree), short talks or chats to obtain information (80% agree), psychosocial support (78% agree) and job search assistance (78% agree). At the other end of the spectrum, the demand for cross-national services related to finding work in other countries and for group support sessions is less likely to have increased (less than 35% of respondents report an increase in demand for these services).

These changes in demand for specific career guidance services are consistent with the types of workers who increased the use of career guidance the most during the pandemic, as well as with the circumstances at the time. The newly unemployed, students in their last year of school and workers in vulnerable sectors may have been especially interested in labour market information and job search assistance. The stress of being exposed to a pandemic may have increased the demand for psychosocial support while the difficulties to travel across countries and the need for social distancing may have decreased the demand for cross-national services related to finding work in other countries and for group support sessions.

How career guidance services were adapted and delivered

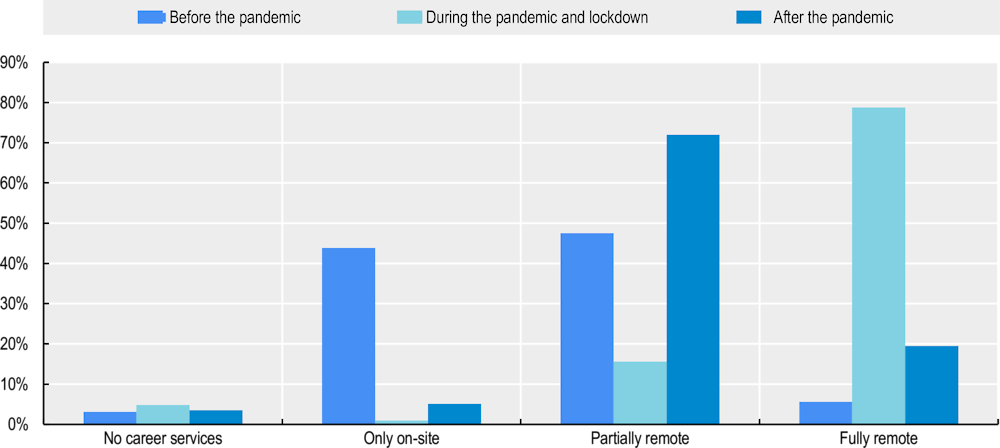

Before the pandemic, career guidance services were generally either offered on-site combined with some remote services or only on-site, with almost no career guidance services being fully remote (Figure 2). During the pandemic, the need for social distancing made it impossible to carry out on-site services and providers had to shift delivery towards fully remote alternatives. The percentage of respondents who report that career guidance was delivered fully remotely jumped from 6% in the pre‑pandemic period to almost 80% during the pandemic. After the pandemic it is expected that some of the fully remote alternatives that have been developed or used will remain. Almost three‑quarters of respondents expect that career guidance services delivery will remain partially remote after the pandemic, up from 47% before the pandemic.

Figure 2. Change in career guidance services delivery channel before, during and after the pandemic

Percentage of respondents who report each career guidance services delivery method by pandemic period

Note: Average for OECD countries and for respondents who refer to guidance activities that predominantly involve adults or both adults and young people in educational institutions.

Source: Inter-Agency 2020 Career Guidance Survey.

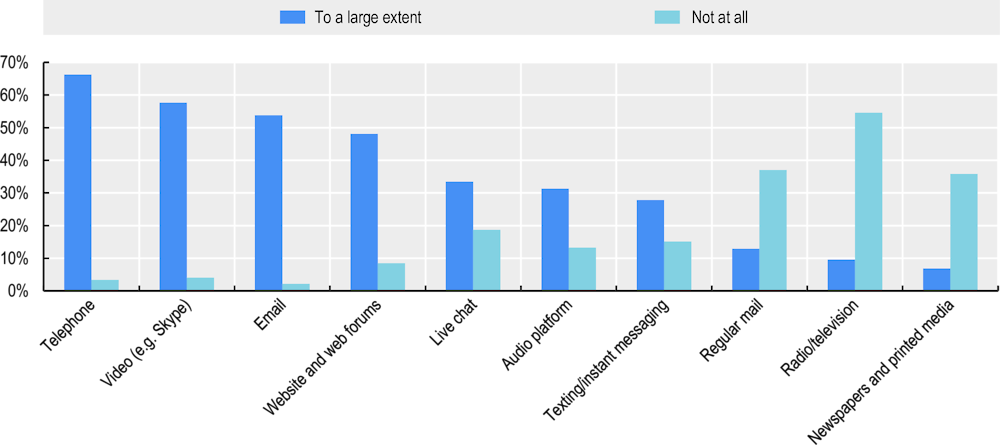

Technology was essential for the transition to fully remote career guidance services during the pandemic (Figure 3). The five most used career guidance delivery tools were: telephone (66%), videoconference tools (58%), email (54%), website and web forums (48%) and live chat (33%). Besides allowing access when social distancing was required, technology also has the potential to improve career guidance services through increasing access to new users, providing innovative services and adapting career guidance services to the needs of users (Cedefop et al., 2021[1]). In contrast, regular mail, radio, television, newspapers and printed media were barely used. Given the massive use of technology during the pandemic, most OECD countries made or planned changes to online career guidance portals during the COVID‑19 pandemic, as shown in Table 1.3

This increased use of remote career guidance delivery is somewhat aligned with the preferences of career guidance users. In the SCGA, adults showed an interest in having more online chat, videoconferencing, and instant messaging career guidance interactions and less face‑to-face interactions (OECD, 2021[3]), even though face‑to-face delivery was still the preferred option by most respondents. Technology tools allow for more flexibility in when and how career guidance is delivered, which helps to overcome an often‑cited barrier to accessing career guidance: lack of time. Unfortunately, despite being aligned with users’ preferences, there is not much information about how the quality of remote career guidance services compares to the quality of face‑to-face services.

Figure 3. Most and least used communication methods by career guidance services

Percentage of respondents who report that career guidance services used each communication method to a large extent or not at all

Note: Average for OECD countries and for respondents who refer to guidance activities that predominantly involve adults or both adults and young people in educational institutions.

Source: Inter-Agency 2020 Career Guidance Survey.

Some countries, in their online career guidance portals, included a section specifically related to the COVID‑19 pandemic. Such portals promoted essential services sectors with a shortage of workers, and provided labour market information, information on government support during the pandemic, short training options to ease re‑entry into the workforce and, in some cases, remote counselling services (OECD, 2021[3]).

For example, in Canada, a COVID‑19 resource page was launched on the Job Bank website in mid-April 2020. In the United States, information on how to file for unemployment and on other benefits available for recently unemployed workers was available through the CareerOneStop portal.

To reinforce remote counselling services during the pandemic, adults in Greece could have a real time conversation with a career guidance advisor through the EOPPEP Internet Portal for Adults, while the Czech Republic’s MoLSA portal had a chatbox answer visitors’ key questions. In Estonia, a new subsection that described online career guidance services available to users was added to the career guidance portal www.minukarjäär.ee (OECD, 2021[3]).

Table 1. Changes to online career guidance portals during the COVID‑19 pandemic

|

Country |

Changes made or planned |

Description of change |

|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

Yes |

|

|

Austria |

No |

/ |

|

Belgium |

Yes |

|

|

Canada |

Yes |

|

|

Czech Republic |

Yes |

|

|

Denmark |

Yes |

|

|

Estonia |

Yes |

Special subsection describing online career services was added to the online portal www.minukarjäär.ee |

|

France |

Yes |

|

|

Greece |

Yes |

|

|

Ireland |

Yes |

|

|

Lithuania |

No |

/ |

|

Poland |

Yes |

|

|

Portugal |

No |

/ |

|

Spain |

Yes |

The portal www.sepe.es/ reinforced its virtual tools for career guidance. |

|

Sweden |

Yes |

|

Source: OECD (2021[3]), Career Guidance for Adults in a Changing World of Work, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9a94bfad-en.

Social media also became a popular tool to provide career guidance information. Most career guidance practitioners and policy officials (73%) reported that career guidance services in their countries were using this delivery channel during the pandemic.

While the delivery of most career guidance activities was adapted to the COVID‑19 context, some were less amenable to adaptation. The most adapted career guidance service was psychosocial support (68%), as there was a high need for this service given the stress originating from the pandemic and lockdown. In contrast, over 30% of respondents to the IAG CG Survey report that group information sessions and co-constructing career activities were discontinued in their countries, which could be related to the need for social distancing.

Despite these general trends, individual country responses differed considerably, depending on their pre‑existing career guidance services and ability to transition to remote options, as shown in Table 2. For example, Hungary was unable to provide remote career guidance services and services closed during the pandemic, as these had been designed for in-person, face‑to-face meetings (Cedefop, 2020[7]). In contrast, Belgium, Estonia, France, Greece, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, and Spain put in place or strengthened pre‑existing remote services, such as services online, through telephone, text messages, and/or other innovative tools.

In Estonia, career guidance services were made available through telephone, email, Skype and Microsoft Teams, offering career counselling and workshops. In Sweden, a digital self-service package for career guidance was relaunched. It includes digital career guidance services that can be used by individuals unsure about what job to pursue, those who want to study or change job and those who wish to obtain current labour market information (OECD, 2021[3]).

Table 2. Changes to career guidance services during the COVID‑19 pandemic

|

Country |

Changes made or planned |

Description of change |

|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

Yes |

|

|

Belgium |

Yes |

|

|

Czech Republic |

Yes |

|

|

Denmark |

No |

/ |

|

Estonia |

Yes |

|

|

France |

Yes |

|

|

Greece |

Planned |

Included a special application for distance career guidance in its adults career guidance platform of EOPPEP http://e-stadiodromia.eoppep.gr/ |

|

Ireland |

Yes |

|

|

Italy |

Yes |

|

|

Lithuania |

Yes |

|

|

Mexico |

Not yet |

/ |

|

Portugal |

Yes |

|

|

Spain |

Yes |

|

|

Sweden |

Yes |

|

|

Turkey |

Yes |

|

Source: OECD (2021[3]), Career Guidance for Adults in a Changing World of Work, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9a94bfad-en.

Many countries focused on ensuring the continuity of career guidance services through supporting their practitioners in adapting services to remote delivery. For example, in France, the focus was to ensure that all career guidance advisors could telework (OECD, 2021[3]). Thus, they were provided with work computers and mobile phones. Despite the crisis, almost 90% of individuals who were already in touch with a career guidance advisor continued to receive support (Cedefop, 2020[8]).

In Ireland and Portugal, career guidance advisors were provided with guidelines to deliver their services remotely during the pandemic (Department of Education and Skills, 2020[9]). In Ireland, additionally, the National Centre for Guidance in Education (NCGE) organised a series of webinars to help advisors continue providing guidance services at a distance (OECD, 2021[3]). Similarly, in some countries, career guidance providers shared good practices, like in Finland, where career guidance providers shared materials and experiences using their own social media channels (Cedefop, 2020[10]).

As a result of these measures, career guidance practitioners generally felt supported during the transition to fully remote operations, despite the sudden switch. Over 60% of practitioners and policy officials who participated in the IAG CG Survey agreed that practitioners received guidelines to provide distance career guidance (66%), that issues concerning the impact of the pandemic on practitioners’ working conditions had been addressed by their employers (65%), that reliable, real-time career information was publicly available (62%) and that new tools to deliver services had or were being provided at the time (61%).

One concern about shifting to fully remote operations, especially through virtual means, was that individuals with low levels of education, older individuals, as well as those living in rural or remote areas would be excluded from career guidance services, due to lack of access to the Internet, computers or other electronic devices. Most respondents (78%) to the IAG CG Survey believed that the most effective communication method to reach these vulnerable users was the telephone.

Even when face‑to-face support was available before the pandemic, the use of formal career support was low among low-educated and older adults, the unemployed and those living in rural areas, (OECD, 2021[3]). However, given that the pandemic had a stronger negative impact on employment of workers in this group (OECD, 2021[2]), it is possible that their use of career guidance services would have increased if face‑to-face services had been available. Thus, career guidance providers may have missed an important segment of potential career guidance users during the pandemic, despite the extensive use of telephone, inadvertently broadening the gap in the use of career guidance services for these groups. Efforts to close this gap will need to continue in the post-pandemic phase.

Additionally, early evidence suggests that remote delivery of career guidance could be less effective than in-person delivery (OECD, 2021[3]). Since remote career guidance services are likely to remain post-pandemic, they must be of high quality to ensure their effectiveness.

Key take‑aways on career guidance for adults during the pandemic

During the pandemic, demand for adult career guidance services increased, especially for newly unemployed workers, students in their last year of school and workers in vulnerable sectors.

Most countries shifted to fully remote career guidance services, adapting most of their activities to new delivery channels. Career guidance services for adults were offered via telephone, video conferencing tools, email and career guidance services’ online portals. This shift is somewhat aligned with users’ preferences on career guidance delivery tools, who, pre‑pandemic, seemed to want more remote delivery.

Countries’ efforts focused on making changes to online career guidance portals, putting in place or improving remote career guidance sessions or supporting career guidance practitioners’ transition to telework.

Career guidance advisors consider the telephone to be the most effective channel to reach low-educated and older adults, the unemployed and those living in rural areas. However, considering these groups were particularly hard hit by the pandemic, it is possible that career guidance use gaps widened despite the extensive use of the telephone.

What is the role for career guidance going forward

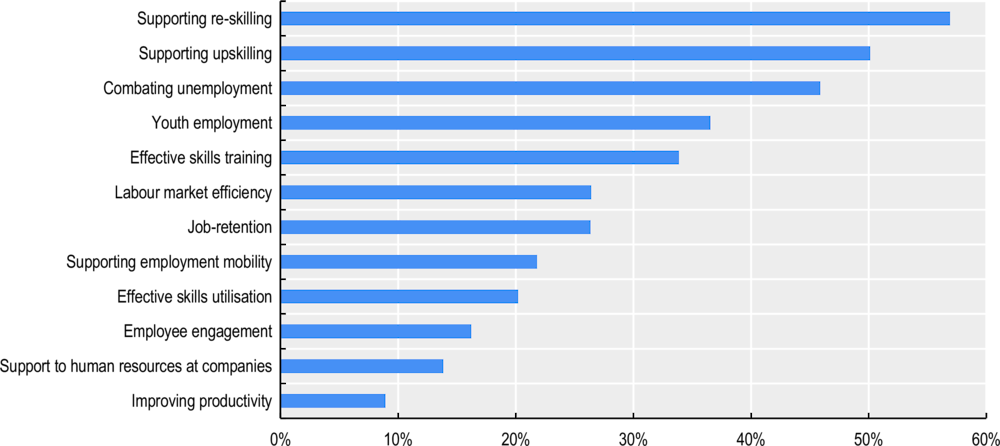

Career guidance will be key in the post-pandemic period as it can contribute to the labour market recovery through motivating workers to get re‑skilled and guiding workers towards sustainable jobs that best match their skills. In fact, career guidance practitioners and policy officials who answered the IAG CG Survey believe that career guidance can promote social and economic recovery through supporting re‑skilling (57%), upskilling (50%) and through combating unemployment (46%) by facilitating better matches between workers and jobs (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Policy aims to which career guidance can best contribute to

Percentage of respondents who indicate each policy aim as one of the three that career guidance can best contribute to

Note: Average for OECD countries and for respondents who refer to guidance activities that predominantly involve adults or both adults and young people in educational institutions.

Source: Inter-Agency 2020 Career Guidance Survey.

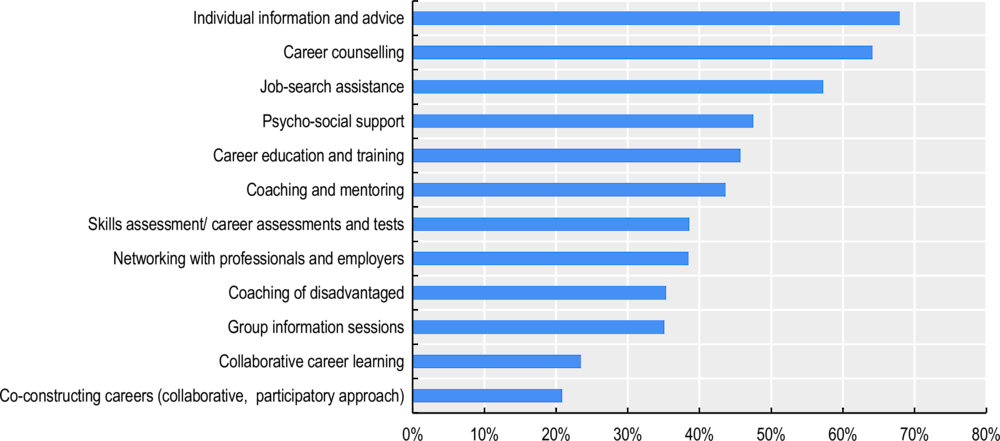

Among all the different career guidance activities, more than half of respondents to the IAG CG Survey believe that in the near future the most relevant activities will be to provide individualised information and advice (68%), career counselling (64%) and job-search assistance (57%) (Figure 5). These activities are consistent with the fact that most adults use career guidance services to receive advice when looking for work or wishing to change jobs and to learn about education and training options (OECD, 2021[3]).

Figure 5. Most relevant career guidance activities in the near future

Percentage of respondents who choose each activity as one of the three most important in the following 12‑18 months

Note: Average for OECD countries and for respondents who refer to guidance activities that predominantly involve adults or both adults and young people in educational institutions.

Source: Inter-Agency 2020 Career Guidance Survey.

Finally, the pandemic has triggered a change in the delivery methods of career guidance services, transitioning to digital means. It is expected that after the pandemic some activities will return to being carried out in-person, and some will remain virtual. About 70% of practitioners and policy officials respondents to the IAG CG Survey believe that in the post-pandemic period career guidance services delivery will be partially remote, with almost 20% believing that they will be fully remote (Figure 2). In contrast, only 5% of respondents believe that career guidance services delivery will be only in-person, compared to 44% of respondents who reported that career guidance services were only in-person pre‑pandemic.

Conclusion and policy insights

The COVID‑19 pandemic raised major challenges for the delivery of career guidance services. In particular, it excluded from these services individuals with no access to the Internet or electronic devices or who lacked digital skills, although this was partly mitigated where telephone delivery was widely used.

However, it also created opportunities to use less conventional communication channels, more aligned to users’ preferences, to expand distance career guidance services and to set up or further develop career guidance online portals.

This created new access opportunities for individuals who are physically far from career guidance practitioners to benefit from these services. Going forward, this could potentially reduce delivery costs and improve service by matching career guidance users in areas with excess demand to practitioners in areas with excess supply.

The advantages of remote career guidance services should remain even after the pandemic ends, combined with the reopening of in-person services. The combination of both delivery channels ensures that career guidance services reach the maximum amount of users while improving service and reducing costs.4

Online portals should also remain up to date after the pandemic. They can be effective career guidance tools and useful sources of information for skill needs, education and training programmes, the quality of training providers, training costs or financial incentives available (e.g. subsidies, tax exemptions).

Given the impact of the pandemic on labour markets, career guidance is particularly relevant to ensure that workers’ skills remain up to date and to help them match with the most suitable jobs. Thus, countries should raise awareness of the usefulness of career guidance services through, for example, media campaigns.

Similarly, vulnerable adults, including older jobseekers and low-skilled workers, should be made fully aware of career guidance services. These groups use these services less than high-skilled adults, which may hinder their ability to find good quality jobs.

Career guidance must be of good quality to be effective. Thus, countries should define and accredit quality standards on career guidance delivery, monitor outcomes of providers, professionalise career guidance advisors, and allow practitioners to offer more tailored and relevant advice through the use of high quality skills assessments and anticipation information (OECD, 2021[3]).

Finally, given the potential for career guidance to contribute to labour market recovery after the COVID‑19 pandemic, governments should ensure that, when not provided by Public Employment Services, career guidance services are, at least partially, publicly funded, so all adults can afford to access them, particularly in countries where free public provision is limited.

Working with OECD

The OECD is currently engaged in a number of projects focused on various aspects of adult learning, including inclusiveness, responsiveness, quality assurance, certification and career guidance. It is also working with countries to support the development of national skill strategies through a whole‑of-government approach. To accompany this work, the OECD has developed: the Priorities for Adult Learning dashboard, an interactive tool which allows countries to benchmark their adult learning systems against each other and the OECD average; the Skills for Jobs Database, to measure skills imbalances in over 40 countries and regions in the OECD and beyond; and the OECD Skills Profiling Tool, a tool that assesses and provides information on an individual’s skill set and potential occupations to career guidance counsellors. As the brief discusses, career guidance is expected to play a crucial role in the recovery to ensure that jobseekers relocate to sustainable jobs for which they have the required skills or access relevant training to up- or re‑skill. A good system of career guidance for adults is a crucial part of a responsive and future‑ready adult learning system. The OECD is currently supporting several countries to improve access, inclusiveness, provision and quality of their system of career guidance for adults. The work is based on data collected through the OECD Survey of Career Guidance for Adults – conducted in 11 countries so far – as well as through analysis of existing policies and programmes and peer learning from relevant international good practices.

References

[5] Buba, J. et al. (2021), What did job reallocation look like in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic?, World Bank Jobs and Development Blog, https://blogs.worldbank.org/jobs/what-did-job-reallocation-look-early-months-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 22 February 2022).

[10] Cedefop (2020), “Inventory of lifelong guidance systems and practices - Finland”, CareersNet national records, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/country-reports/inventory-lifelong-guidance-systems-and-practices-finland-1 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

[8] Cedefop (2020), “Inventory of lifelong guidance systems and practices - France”, CareersNet national records, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/country-reports/inventory-lifelong-guidance-systems-and-practices-france#guidance-for-the-employed (accessed on 20 August 2021).

[7] Cedefop (2020), “Inventory of lifelong guidance systems and practices - Hungary”, CareersNet national records, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/country-reports/inventory-lifelong-guidance-systems-and-practices-hungary (accessed on 26 July 2021).

[1] Cedefop et al. (2021), Investing in career guidance. Revised edition 2021., https://www.etf.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/investing-career-guidance (accessed on 22 July 2021).

[6] Cueffe, M. (2021), Skills and Intersectoral Labour Reallocation in the aftermath of the COVID-19 Crisis, https://www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr/Articles/2b634c62-0062-468c-af88-fca1948a944c/files/b07b8a60-d919-42d3-a9c1-ebec62474b54.

[9] Department of Education and Skills (2020), “Continuity of Guidance Counselling Guidelines for schools providing online support for students”, https://www.ncge.ie/sites/default/files/schoolguideance/docs/continuity-of-guidance-counselling-guidelines-for-schools-providing-online-support-for-students.pdf.

[3] OECD (2021), Career Guidance for Adults in a Changing World of Work, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9a94bfad-en.

[2] OECD (2021), OECD Employment Outlook 2021: Navigating the COVID-19 Crisis and Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5a700c4b-en.

[4] OECD (2022 forthcoming), Employment Outlook, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Contact

Stefano SCARPETTA (✉ stefano.scarpetta@oecd.org)

Glenda QUINTINI (✉ glenda.quintini@oecd.org)

Patricia NAVARRO-PALAU (✉ patricia.navarro-palau@oecd.org)

Notes

← 1. The SCGA was an online OECD survey carried out in 2020 in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States. It targeted users and potential users of career guidance and includes responses from 15 430 adults aged 25‑64.

← 2. This survey was a flash joint international survey co‑ordinated by Cedefop and designed and implemented by members of the Inter- Agency Working Group on Work-Based Learning (IAG-WBL) together with the International Centre for Career Development and Public Policy (ICCDPP) and Cedefop’s CareersNet. The members of the IAG-WBL are: the European Centre for Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop), the European Commission, the European Training Foundation (ETF), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations Educational, scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The survey took place between 8 June and 3 August 2020 and its respondents were career guidance practitioners and policy officials. This analysis includes responses from 479 respondents from OECD member countries. About 60% of respondents worked in public organisations and about 15% of them in private organisations. The remaining respondents worked in other types of organisations such as NGOs or civil society organisations.

← 3. Information from replies to the career guidance policy questionnaire that accompanied the SCGA.

← 4. For more guidance on policies to promote and support quality adult career guidance systems, please, refer to the OECD report “Career Guidance for Adults in a Changing World of Work” (OECD, 2021[3]).