This chapter introduces the main climate‑related provisions in the OECD Guidelines and Due Diligence Guidance. It defines the concepts of climate risks and impacts through the perspective of RBC principles and standards and how the concepts interact with other approaches (i.e. financial materiality and climate science). The chapter further outlines investor’s relationship to climate risks and impacts.

Managing Climate Risks and Impacts Through Due Diligence for Responsible Business Conduct

Overview of climate‑related provisions in the OECD Guidelines and Due Diligence Guidance

Abstract

Climate‑related provisions under the OECD Guidelines and OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct

The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (“the OECD Guidelines”) are the most comprehensive government-backed instrument on Responsible Business Conduct (RBC) – covering all areas of business responsibility, including a dedicated chapter on the Environment, amongst others. The OECD Guidelines call on companies (including investors) to avoid causing or contributing to adverse impacts and seek to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts associated with their activities and business relationships. The OECD Guidelines also recognise that investors should contribute positively to environmental, economic, and social progress worldwide, with a view to achieving sustainable development (OECD, 2023[8]).

The Environment chapter of the OECD Guidelines provides a set of recommendations for enterprises, including investors, to ensure strong environmental performance and help minimise their contribution to negative environmental impacts.1 It provides that enterprises should, inter alia (OECD, 2023[8]):

1. Establish and maintain a system of environmental management appropriate to the enterprise associated with the operations, products and services of the enterprise over their full life cycle, including by carrying out risk-based due diligence […] for adverse environmental impacts [including climate change], including through:

a) identifying and assessing adverse environmental impacts associated with an enterprise’s operations, products or services […]

b) establishing and implementing measurable objectives, targets and strategies for addressing adverse environmental impacts associated with their operations, products and services and for improving environmental performance. Targets should be science‑based, consistent with relevant national policies and international commitments, goals, and informed by best practice;

c) regularly verifying the effectiveness of strategies and monitoring progress toward environmental objectives and targets, and periodically reviewing the continued relevance of objectives, targets and strategies;

d) providing the public, workers, and other relevant stakeholders with adequate, measurable, verifiable (where applicable) and timely information on environmental impacts associated with their operations, products and services based on best available information, and progress against targets and objectives as described in paragraph 1.b;

e) providing for or co‑operating in remediation as necessary to address adverse environmental impacts the enterprise has caused or contributed to and using leverage to influence other entities causing or contributing to adverse environmental impacts to remediate them. […]

5. Continually seek to improve environmental performance, at the level of the enterprise and, where appropriate, entities with which they have a business relationship.”

The commentary to Environment chapter of the OECD Guidelines further provides that:

76. Enterprises have an important role in contributing towards net- zero greenhouse gas emissions and a climate resilient economy, necessary for achieving internationally agreed goals on climate change mitigation and adaptation. During the process of transitioning to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, many business activities will involve some level of emissions of greenhouse gases or reduction of carbon sinks. Enterprises should ensure that their greenhouse gas emissions and impact on carbon sinks are consistent with internationally agreed global temperature goals based on best available science, including as assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

77. This includes the introduction and implementation of science‑based policies, strategies and transition plans on climate change mitigation and adaptation as well as adopting, implementing, monitoring and reporting on short, medium and long-term mitigation targets. These targets should be science‑based, include absolute and also, where relevant, intensity-based GHG reduction targets and take into account scope 1, 2, and, to the extent possible based on best available information, scope 3 GHG emissions. It will be important to report against, review and update targets regularly in relation to their adequacy and relevance, based on the latest available scientific evidence and as different national or industry specific transition pathways are developed and updated. Enterprises should prioritise eliminating or reducing sources of emissions over offsetting, compensation, or neutralisation measures. Carbon credits, or offsets may be considered as a means to address unabated emissions as a last resort. Carbon credits or offsets should be of high environmental integrity and should not draw attention away from the need to reduce emissions and should not contribute to locking-in greenhouse gas intensive processes and infrastructures. Enterprises should report publicly on their reliance on, and relevant characteristics of, any carbon credits or offsets. Such reporting should be distinct from and complementary to reporting on emissions reduction. […]

79. Achieving climate resilience and adaptation is a critical component of the long-term global response to climate change to protect people and ecosystems and will require the engagement and support of all segments of society. Enterprises should avoid activities, which undermine climate adaptation for, and resilience of, communities, workers and ecosystems.”

The OECD Guidelines call on enterprises to carry out risk-based due diligence to avoid and address adverse impacts on people, planet and society. RBC due diligence is understood as the process through which enterprises can “identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address their actual and potential adverse impacts as an integral part of business decision-making and risk management systems” (OECD, 2023[8]). Section II provides an overview of the key measures under the due diligence framework and how they can be adapted by institutional investors in the context of climate impacts.

Understanding climate impacts and risks under the OECD Guidelines and associated due diligence approach for investors

The OECD Guidelines and associated RBC due diligence guidances are concerned primarily with actual and potential adverse impacts on people and the planet associated with business activity:

Under the OECD Guidelines, climate change is recognised as an adverse environmental impact, which itself is defined as “significant changes in the environment or biota which have harmful effects on the composition, resilience, productivity or carrying capacity of natural and managed ecosystems, or on the operation of socio‑economic systems or on people.” (OECD, 2023[8]).

Building on the OECD Guidelines definition, in the present tool, climate risks refer to the potentiality of such impacts arising. Unless otherwise specified, this is the meaning attributed to this term throughout this tool.

Climate impacts and risks may be understood differently by different communities, e.g. climate scientists and investors, based on different perspectives.

For many investors, climate risks refer to the financial risks posed to portfolios as a result of climate‑related physical, transition and other liability risks (see Box 1).

From the perspective of climate science, climate impacts refer to the effects on natural and human systems of extreme weather and climate events related to climate change. And climate risks refer to the risks of such climate impacts occurring (IPCC, 2023[10]) (Box 2). There are two approaches needed for policy makers, private actors and other stakeholders to respond to climate change and manage climate risks and impacts: mitigation and adaptation.

Given the difference in focus of the RBC due diligence approach, which is focused on preventing and mitigating adverse impacts on people and planet associated with business activity, it may differ from existing investor practices related to climate risk management as well as from existing disclosure or reporting frameworks that focus on climate‑related financial risks i.e. the Task Force on Climate‑related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) (see Annex Table 3) or the International Sustainability Standard Board (ISSB).

Box 1. Climate related risks from the perspective of financial materiality

In addition to climate risks and impacts on society and the environment, investors and other financial actors consider different types of climate risks that can affect portfolio performance and financial stability. These include:

Physical risks, i.e. the impacts on insurance liabilities and the value of financial assets, including damage to assets and operations arising from climate‑ and weather-related events, including indirect impacts across supply chains.

Transition risks, i.e. the financial risks and reassessment of the value of assets that could result from the process of adjustment towards a lower-carbon or climate‑resilient economy, due to changes e.g. in policy, regulation, law, technology or markets. Key drivers of transition risks include technological shocks (e.g. rapid decrease of renewable power costs); policy and regulatory shocks (e.g. introduction of a carbon price or resilience requirements); sudden changes in “climate sentiments” of financial actors; market shifts due to innovation, disruption and changes in consumer preferences; reputational risks; and risks related to legal liability.

Source: Carney (2015[11]), Breaking the tragedy of the horizon – climate change and financial stability – speech by Mark Carney, www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2015/breaking-the-tragedy-of-the-horizon-climate-change-and-financial-stability; Monasterolo (2019[12]), Climate Change and the Financial System, ssrn.com/abstract=3479380

Moreover, there are often interdependencies and linkages between climate‑related financial risks and those associated with adverse impacts to society and the environment. The OECD Guidelines recognise that environmental impacts can be considered financially material if they can reasonably be expected to influence an investor’s assessment of an enterprise’s value; timing and certainty of an enterprise’s future cash flows or an investor’s investment or voting decisions. The determination of which information is material may vary over time, and according to the local context, enterprise specific circumstances and jurisdictional requirements. Impacts that may not seem to be financially material but that are relevant to people, and the planet may be financially material for an enterprise at some point. Due diligence processes, as outlined in this tool, can be a useful means by which investors can ensure they are effectively identifying impacts and risks in a consistent and credible manner, including impacts and risks which may be, or which may become financially material. (OECD, 2023[8])

Box 2. Understanding climate risks and impacts from the perspective of climate science

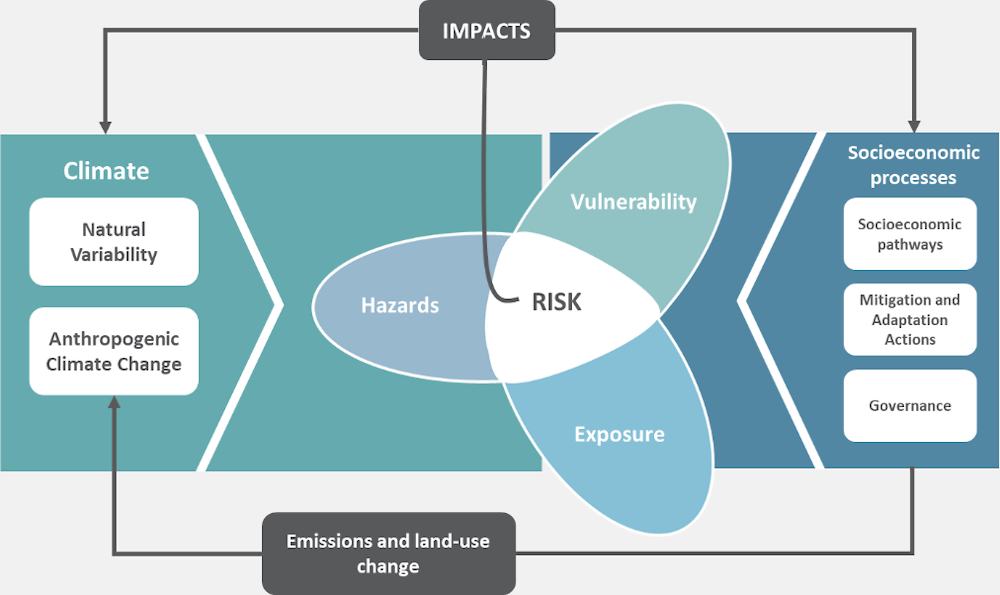

From the perspective of climate science, climate impacts refer to the effects on natural and human systems of extreme weather and climate events and of climate change. Climate risks, i.e. the potential of climate impacts arising, refer to the potential for consequences where something of value is at stake and where the outcome is uncertain, and recognising the diversity of values. Climate change involves complex interactions and changing likelihoods of diverse impacts. The risk of climate impacts results from the interaction of climate hazards (including hazardous events and trends) with the vulnerability and exposure of human and natural systems (Figure 1). Changes in both the climate system and socio‑economic processes including adaptation and mitigation are drivers of hazards, exposure, and vulnerability.

Figure 1. Assessing and managing the risks of climate change

Source: Based on IPCC (2014[13]), Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/ar5_wgII_spm_en-1.pdf.

The severity and frequency of climate hazards materialise through both slow onset changes (e.g. in temperatures, precipitation patterns, sea level rise and biodiversity loss) and acute changes arising from particular events (e.g. weather-related events like floods, wildfires, drought, heatwaves, and the increasing frequency and severity of tropical storms). There is also the potential that critical thresholds in the climate system will be passed, triggering so-called tipping points that could have severe and irreversible impacts (e.g. collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet, shut down of the North Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation).

Climate risks can cause significant socio‑economic impacts (e.g. in terms of livelihoods, economic prosperity, development gains, ecosystem and human health, cultural losses, and possibly political stability and social coherence). Socio‑economic impacts are further determined by a combination of exposure to the hazards, vulnerability and socio‑economic resilience determining the ability to cope with and recover from disasters. Climate change can also have significant environmental impacts on itself, e.g. through threatening biodiversity, which underpins all life on land and below water, as well as ecosystem services delivered by biodiversity.

Source: IPCC, (2023[10]), AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023, www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle; IIGCC, (2020[14]), Understanding physical climate risks and opportunities, www.iigcc.org; Lenton et al., (2008[15]), Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system, www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0705414105; Lenton et al., (2019[16]), Climate tipping points – too risky to bet against, www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-03595-0; Hallegate et al., (2020[17]), From Poverty to Disaster and Back: a Review of the Literature, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41885-020-00060-5; OECD, (2022[18]), Climate Tipping Points: Insights for Effective Policy Action, doi.org/10.1787/abc5a69e-en.

Understanding investor’s relationship to climate risks and impacts directly linked to their investments and activities

Under the OECD Guidelines and RBC due diligence framework, an investor’s operations, products and services can be directly linked to climate risks and impacts through a business relationship, including through their ownership in, or management of, shares in an investee company or asset. This tool focuses on this type of relationship and therefore provides recommendations on carrying out RBC due diligence with respect to climate risks and impacts that an investor may be directly linked to through its assets and investee companies. It does not explore situations in which an investor may be contributing to adverse climate impacts through their own activities.2

In the context of this tool, investors may be directly linked to climate impacts and risks where they invest in assets or businesses with activities that:

Contribute directly or indirectly to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or impacts on carbon sinks in a way that is not consistent with internationally agreed global temperature goals based on best available science, including as assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); or

Undermine climate adaptation for, or resilience of, communities, workers and ecosystems (OECD, 2023[8]).

During the process of transitioning to net-zero GHG emissions, many business activities will involve some level of emissions of GHG or reduction of carbon sinks. It will be important that investees introduce and implement strategies and transition plans on climate change mitigation and adaptation as well as adopt, implement, monitor and report on short-, medium- and long-term mitigation targets. These targets should be science‑based, include absolute and also, where relevant, intensity-based GHG reduction targets and take into account scope 1, 2, and, to the extent possible based on best available information, scope 3 GHG emissions. (OECD, 2023[8])

For investors, it will be important that investment decisions at a transaction-level align with their own scope 3 targets and objectives.3 (See Measure 4: Track implementation and results of due diligence for climate impacts for discussion on target and objective setting). Appropriate targets and objectives will vary across investors as well as with respect to assets and investee companies but should be consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre‑industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre‑industrial levels. It is important to recall that the expectation that investors seek to prevent or mitigate adverse climate impacts from their investments is not intended to shift responsibility from the investee company to prevent or mitigate its adverse climate impact itself. Investors are not generally responsible for the actions of the investee entity with which they have a business relationship, but rather for their own conduct, including their efforts to influence that entity.

In addition, this tool acknowledges that how investors seek to prevent and mitigate an adverse climate impact will depend on the type of asset class and investment strategy considered, the position in an investment portfolio, the mandate of the investor, their interpretation of investors duties, the type of investor (asset owner versus asset manager) as well as the regulatory context, as national circumstances differ (OECD, 2017[7]; 2017[3]). Institutional investors following the “Universal Owner” approach4 for instance are more likely to take into account climate and other sustainability concerns compared to those engaged in traditional portfolio management (OECD, 2017[3]).

Box 3. Activities associated with adverse climate risks and impacts

Activities associated with adverse climate risks and impacts include:

a. Activities which are associated with GHG emissions or impacts on carbon sinks that are not consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goal and based on best available science, including as assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Certain sectors, products, services or activities are associated with relatively higher levels of GHG emissions or reduction of carbon sinks and thus merit attention in the context of risk-based climate strategies and plans to finance and implement their transition. As recommended in the OECD Guidance on Transition Finance, to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, institutional investors can also play a key role in supporting high-carbon, energy-intensive, and hard-to‑abate companies and economic activities transition to net-zero emission trajectories, and engagement with investee companies involved in such activities is encouraged to ensure real-economy decarbonisation. (OECD, 2022[19]) Such activities include but are not limited to:

Activities in end-use sectors associated with significant GHG emissions, including industry, transportation and building. For example, industrial production of materials (e.g. paper, cement or aluminium) or processing of commodities (e.g. use of cotton in garment and footwear sector) that result directly or indirectly in GHG emissions upstream in their supply chain, as well as land-use change.

Activities associated with the generation, use and consumption of renewable or non-renewable energy (e.g. extraction of resources, production, and transportation of fuel, and generation of electricity, steam, heating and cooling).

Activities associated with the production of waste and pollutants that affect climate change (OECD/CDSB, 2015[20]). For example, waste management generates methane, a GHG part of Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) generated by anaerobic waste decomposition in landfills (OECD, 2012[21]).

Land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) and agriculture, and related GHG emissions (CDSB, 2019[22]), including activities that negatively impact carbon sinks in terrestrial and marine environments, or activities that contribute to disturbance or destruction of wetlands, estuarine or tidal areas and coastal ecosystems such as mangroves.

b. Activities that may undermine climate adaptation for or resilience of communities, workers and ecosystems: These are activities that fail to take into account climate resilience needs or lead to increased risks of negative impacts of climate change on people, the environment or other assets, or activities that hamper adaptation efforts. Examples include real estate or infrastructure in zones that are likely to be more exposed to flooding risk and other climate impacts and as such could eventually endanger human lives and livelihoods. In the case of infrastructure for instance, decisions on the location, design, operation and maintenance of infrastructure, as well as on their governance and financing, need to be assessed in relation to the exposure and vulnerability of infrastructure to a whole range of current and future climate risks, including flood protection, water supply, rainfall, extreme weather events and sea level rise.

Sources: European Commission, (2019[23]), Guidelines on reporting climate‑related information, ec.europa.eu/info/files/190618-climate-related-information-reporting-guidelines_en; OECD and CDSB, (2015[20]), Climate change disclosure in G20 countries: Stocktaking of corporate reporting schemes, www.oecd.org/investment/corporate-climate-change-disclosure-report.htm; OECD, (2012[21]), Greenhouse gas emissions and the potential for mitigation from materials management within OECD countries, www.oecd.org/env/waste/50034735.pdf; CDSB, (2019[22]), CDSB Framework for reporting environmental and climate change information, www.cdsb.net/sites/default/files/climateguidancedoublepage.pdf.

Notes

← 1. Within the framework of laws, regulations and administrative practices in the countries in which they operate, and in consideration of relevant international agreements, principles, objectives, and standards. (OECD, 2023[8]).

← 2. Investors can contribute to adverse climate impacts through their own activities when greenhouse gas emissions or impacts on carbon sinks associated with these activities are inconsistent with internationally agreed global temperature goals based on best available science, including as assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Whether an investor has introduced and implemented science‑based policies, strategies and transition plans on climate change mitigation and adaptation in line with the recommendations of the OECD Guidelines is relevant in this regard (OECD, 2023[8]).

← 3. The portfolio emissions of global financial institutions are on average over 700 times larger than direct emissions and represents over 99% of total scope 1, 2 and 3 reported emissions by the financial service sector (CDP, 2023[65]).

← 4. “According to this approach, universal owners hold a ‘slice’ of the whole global economy and market through their portfolios. They can therefore improve their long-term financial performance by acting in such a way as to encourage healthy and stable economies and markets. This will ensure that they can pay benefits to their beneficiaries but also provides collateral benefits to the wider community (OECD, 2017[3]).