The Assessment and Recommendations present the main findings of this report and set out recommendations to help Korea make further progress towards aligning water policies, practices and governance arrangements for sustainable management of the Water-Energy-Land-Food Nexus. A draft Action Plan with short-, medium- and long-term steps on how to achieve these recommendations, and suggestions of who may be responsible for them, is presented as Annex 1.A.

Managing the Water-Energy-Land-Food Nexus in Korea

Assessment and Recommendations

Abstract

Pressures on the Water-Energy-Land-Food Nexus in Korea

Water, energy, land and food are essential for economic growth and development, and there are strong linkages between them (the WELF nexus). Considering these linkages is important for government as policies and investment to manage one dimension of the WELF nexus may have detrimental effects or co-benefits on others. Water insecurity at the regional and local scales is often the main bottleneck in the WELF nexus which may limit economic growth across sectors, and impact human wellbeing and ecosystem health (OECD, 2017a).

The Republic of Korea, the eighth-largest OECD economy, has limited natural resources. Korea is among the few OECD countries both with scarce land and under medium-high water stress (OECD, 2017b,c). Urbanisation, industrialisation, population growth (at least until 2030) and climate change are increasing demands on the WELF nexus. The response to date has been to consume more land and augment the supply of water, at the expense of the environment (OECD, 2017b,c), whilst essentially relying on public funding to finance water infrastructure investments.

An ageing population and recent slow-down in economic growth (OECD, 2016a) will limit available public funding for responding to increasing droughts and floods, including investment in climate resilient infrastructure. Furthermore, environmental tax and charge rates on water abstraction and pollution, and land development are too low to cover observed environmental and social externalities, or to encourage pollution reduction and efficient water and land use (OECD, 2017b,c).

The inability to effectively manage the bottlenecks, trade-offs and synergies within the WELF nexus will generate high costs for the Korean economy and will exacerbate inequalities across regions and social groups, now and in the future. This calls for proactive, co‑ordinated and integrated policy and strategic long-term planning to future-proof the WELF nexus and enhance sustainable growth.

Water scarcity

The volume of total water use exceeds the amount of normal water runoff (which is measured during the off-flood season). As such, flood runoff needs to be captured in reservoirs for later use. Korea invests in alternative water resources (e.g. desalination, inter-basin transfers) to supplement dam water supply during periods of drought. These water management options are expensive, energy intensive and have high carbon footprints.

Given the already high water stress and consumption of total available water resources, Korea will need to make substantial efficiency gains in water use and/or water allocation to meet future water demands and maintain economic growth. This is demonstrated by the fact that surface water is already fully allocated in each of the four major river basins – the Han, Geum, Nakdong and Yeongsan/Seomjin River systems – and high rates of leakage by international comparison within some water supply networks (20.6% on average, but up to 41.1% in some areas).

Water supply augmentation can only come at high cost and increasing pressure on public budgets, as the capacity for additional reservoirs in Korea is exhausted (or close to it). Furthermore, recent cases in Brazil (Sao Paulo) and South Africa (Cape Town) confirm that relying on reservoir storage can risk supply failure during severe droughts.

Flooding

Korea’s flood risk index is substantially higher than that of other OECD countries. Over 100 regions of Korea have experienced water inundation more than twice in the 2000s. Korea has worked hard to reduce flood risks through investment in infrastructure as well as in forecasting and warning systems. The government has also put in place a plan to improve rainwater drainage capabilities, such as expansion of water control capabilities by 2025 (OECD, 2017c).

Thirty areas have been identified at high-risk of flooding. The government is responding to water-related risks by means of various techniques such as low impact development (LID), groundwater storage, wetland restoration and green infrastructure policies, as well as separating stormwater from the sewerage network. But rates of progress are slow compared with the human and financial costs incurred with each flood event, and the capacity to scale up and replicate pilot projects remains unclear. Mechanisms to coordinate land and water planning, and management upstream within the river basins, are missing.

Water quality

Improvements in point source pollution control in Korea have been admirable. Over 90% of the population of Korea is currently served by wastewater treatment services, compared with 71% in 2000. In addition, 83% of the population benefits from advanced (tertiary) wastewater treatment (OECD, 2017b). Still, there are pending issues related to permitting, compliance, monitoring and enforcement of point source discharges from industry and municipalities (OECD, 2017b). Regulation of water quality focuses on the four major river basins; tributaries and coastal streams, which account for 30% of Korean rivers, largely remain unregulated and unmonitored.

Diffuse pollution (predominantly from livestock and urban stormwater run-off) increasingly affects scarce water resources and will continue to do so with intensive livestock production projected to increase (ME, 2015). The proportion of total pollution attributed to diffuse pollution is projected to reach over 70% by 2020 (ME, 2014a)

Korea currently has the highest nitrogen balance and the second-highest phosphorus balance in the OECD, even though the use of chemical fertilisers has declined (OECD, 2017b; 2018). Episodes of algal blooms are frequent in Korea, triggered by high nutrient levels, warm temperatures, reduced river flow (due to reservoirs) and sunlight.

Progress has been achieved in water quality with the introduction of the Korean Total Water Pollution Load Control System (Korean TMDL, the equivalent of a total maximum daily load programme) in the four main river basins, particularly in the Nakdong River Basin. Since the introduction of the Korean TMDL in 2004, reduction targets in point source pollution control of biochemical oxygen demand and total phosphorus have been achieved. Tributaries and coastal streams are not regulated as part of the Korean TMDL.

There are an array of fragmentised initiatives and pilot projects to increase eco-farming, best management practices, and buy-back of riparian land to improve water quality, but they typically rely on voluntary approaches and come at a high cost in comparison to other potential policy solutions, particularly those that utilise the Polluter Pays Principle. The role of land use planning and management is critical for water quality and resource management.

Historical water pollution incidents (e.g. Nakdong accidents in 1991 and 1994) have resulted in a low public trust in drinking water quality with the majority of citizens using bottled water and home water filters. There is room for improvement in engagement with citizens, industrialists and farmers to raise awareness, increase trust and reach solutions in partnership.

Land use and food production

Built-up, urbanised areas have expanded by 51% between 2002 and 2014; a rate that has far surpassed the population growth (6% over the same period). This reflects rapid industrialisation and urbanisation; 70% of the population lives in urban areas, well above the OECD average of 49% (OECD, 2017b).

Korea’s farming model is highly intensive, particularly the livestock sector, which reflects a growing consumer demand for meat products. The intensity of commercial fertiliser and pesticide use is among the highest in the OECD, and livestock density is the second highest after the Netherlands. This has negative ramifications for water and energy use, and land and water pollution. Land acidification is worsening with climate change and agricultural production is expected to decline in both quantity and quality due to climate change and subsequent increase in disease and pests (ME, 2014b).

Currently there are no environmental regulations specifically imposed on agricultural production, with the exception of regulations on livestock manure (OECD, 2018) stipulated under the 2006 Act on the Management and Use of Livestock Excreta. Environmental tax and charge rates on land development are too low to cover environmental and social externalities. The agriculture sector does not pay energy taxes and only partially pays minimal water charges (OECD, 2010). In addition, producer support, as percentage of gross farm receipts (%PSE), is almost three times higher than the OECD average and consists mostly in market price support - a category of support with potentially environmentally harmful effects (OECD, 2018).

Energy supply and use

Korea’s economy is among the most energy intensive in the OECD. This is despite the fact that Korea has no oil resources and very limited natural gas reserves. Furthermore, Korea’s share of renewables in the energy mix remains the lowest in the OECD. Thus, Korea is highly dependent on external energy sources.

Water and energy supply are intimately connected. While hydropower remains limited in Korea's energy supply mix, water is required to cool thermal and nuclear plants, which are projected to multiply in Korea, thus increasing water needs and minimal flow requirements for future energy production.

Korea has a high energy-water risk relative to other countries in the Asia-Pacific region. One study mapping the water consumption for energy production around the Pacific Rim determined that watersheds at energy-water risk represent 59% of all basins in Korea where water is used in energy production (Tidwell and Moreland, 2016).

The way forward

Korea recognises these challenges and sees the opportunity of improved coordination of policies and institutions in relation to the WELF nexus to better respond to uncertainties and create options for sustainable growth in the short and long term. The recent merging of government organisations responsible for water management is one indication of this. The purpose of the Korea-OECD Water Policy Dialogue is to explore best practices from the wider international community that can inspire such coordination to better manage water resources within the WELF nexus.

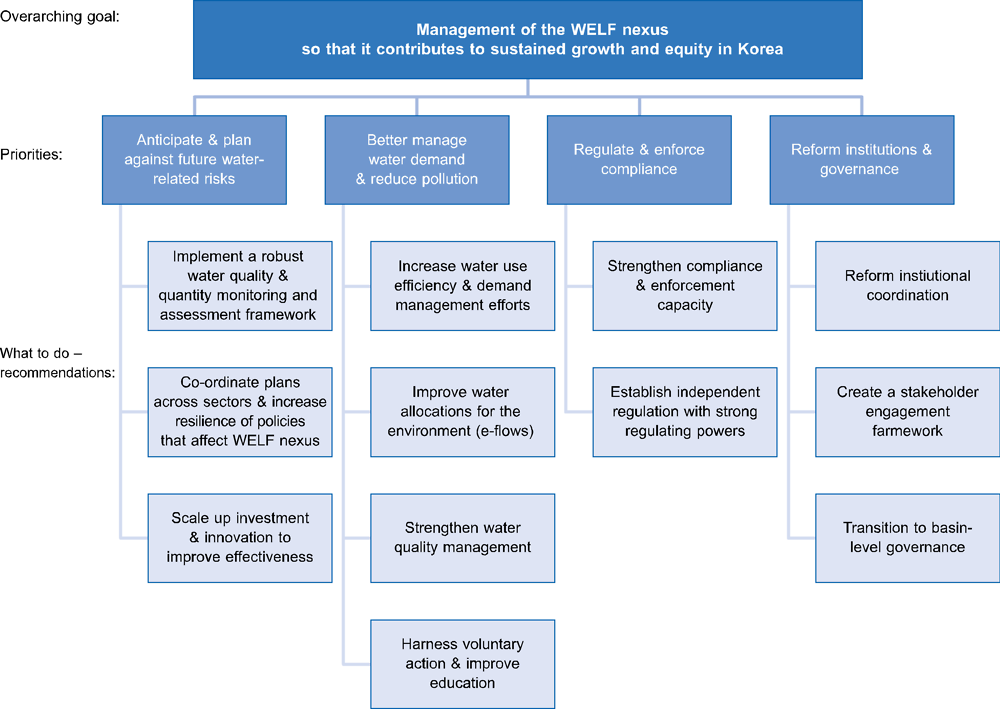

Recommendations rest on four priorities for Korea:

1. Anticipate and plan against future water-related risks

2. Better manage water demand and reduce pollution

3. Regulate and enforce compliance

4. Reform institutions and governance.

The rationale for the selection of these priorities are outlined below, followed by recommendations and a draft action plan on how to achieve them.

Anticipate and plan against future water-related risks

Water quality and quantity monitoring and assessment

Managing water and the WELF nexus starts with a good understanding of the state of the resources (water, land), the environment (the ecosystems which the WELF nexus relies upon) and the pressures and demands on them. Robust data and information are necessary to develop effective and proactive water and land policies, to identify priority actions, set the ambition of policies and to monitor compliance and progress.

There are four areas in particular where the current monitoring and assessment regime could be improved in Korea:

1. Monitoring water quality. The breadth of water quality parameters and sampling locations and frequency is limited. The benefit of increasing water quality monitoring capacity and understanding is that pollution loads and ‘hotspots’ can be identified and targeted, and environmental and health risks can be reduced more cost-effectively (OECD, 2017d,e). To that end: extend the current water quality monitoring programme to tributaries and small streams, and expand monitoring parameters to fully assess human and ecosystem health risks (this should include continuous monitoring of pH, DO, COD, BOD, ammonia, nitrate, phosphate and chlorophyll/blue-green algae (for early warning and control of pollution)); use that data to identify hotspots; target compliance and enforcement of discharge permits in these hotspots; specify land use where it affects water quality most; allocate River Management Funds to improve water quality in hotspots.

2. Groundwater monitoring. While abstraction of water from aquifers is monitored to a limited extent in Korea, information on groundwater quality and surface water-groundwater connections is lacking. This is an issue, as droughts and sea level rise are projected to increase pressure on groundwater resources. More specifically: ensure a sufficient network of groundwater monitoring boreholes that enable robust understanding across each aquifer and their interactions with surface water; use field and satellite data to routinely monitor groundwater levels and depletion; document groundwater quality on at least a quarterly basis, and more frequently where pollution risks are high; use data to tailor compliance monitoring of water abstraction and pollution permits and regulate land use changes; consider groundwater recharge to replenish aquifers and mitigate saline intrusions.

3. Ecological monitoring. In practice: routinely monitor aquatic invertebrates, macrophytes (aquatic plants) and fish to understand ecosystem health. Adjust water and land management and the controls on abstraction and pollution accordingly.

4. River flow monitoring. Develop naturalised flow sequences for each major river, where the effect of artificial influences can be accounted for. Use the natural baseline as the basis for decisions to determine ecological flows and sustainable volumes of abstraction and discharge.

Korea would benefit from more systematically monitoring the costs of action and inaction, the impact on economic and social development, and in particular, how these costs are distributed across regions or social groups. Such economic monitoring or appraisal would support informed discussion on how risks (of water scarcity, floods, or pollution) and opportunities (for economic development) are allocated across regions and groups, and how the distinctive capacities of such groups to respond to these risks or opportunities are taken into account.

For instance, economic monitoring or appraisal could document how senior water rights holders (i.e. water users who benefit from the most secure entitlements to use water) benefit from a privileged situation: they may only use a portion of their water entitlement, while new comers may be denied access to river water. As such, senior water rights holders may be protected against risks of drought while more valuable water uses are at risk. Whilst the customary rights of senior water rights holders are recognised in civil law, they can be socially inequitable and economically inefficient.

Economic analyses should document the privileged position of senior water rights holders and monetise the opportunity costs of preventing other uses of water. Analyses should document the social costs of the current allocation of water-related risks and the potential economic benefits of allocating risks to those best equipped to address them (for instance distinguishing between rice farmers, livestock farmers and farmers who grow perennial crops). Such data is essential to develop cost-effective and equitable responses to nexus-related challenges.

Anticipating and planning

While Korea has robust experience with planning for water, land use and infrastructure developments, planning would benefit from four major developments:

1. Planning should be forward-looking. In Korea, water and infrastructure plans are routinely based on meeting the impact of the worst drought in the historic record, however, the past climate record is not necessarily representative of the future. Planning would be more resilient when a long-term, forward-looking, intergenerational perspective is taken, which considers the potential for extreme, unprecedented events from climate change.

2. Plans should reflect uncertainties. Relying upon a single set of forecasts as the basis for policy decisions and investment – whether for water or energy security, flood risk planning, or land use - is likely to lead to poor decisions. Each plan should explore different socio-economic and climate change scenarios under a range of plausible visions of the future. It should test strategic decisions for their strengths, weaknesses and resilience.

3. Fragmented, single-issue planning should move towards coordinated planning across features of the WELF nexus. Planning should be coordinated across all water uses, including agriculture. Planning should also be coordinated across water, land use, agriculture development and energy supply. Inconsistencies or tensions should be systematically identified. Synergies and opportunities should be explored. Synergies can result in allocation of land and water to its most beneficial use for society, reduced reliance on additional infrastructure, and greater security in terms of water, food or energy at least cost for the community.

4. Coordinated planning is more readily achieved at the scale of river basins, where synergies, trade-offs and options to manage them are more apparent than at the national scale. In particular, options to manage trade-offs benefit from local knowledge, which is difficult to replicate or capture at national level. It benefits from stakeholder engagement, to reflect a range of perspectives and build on diverse expertise. Therefore, plans that relate to water, agriculture and food, land use or energy should preferably be developed at basin scale; national plans should reflect basin specificities.

5. Plans should drive decisions on a range of issues. Plans should clearly establish the overall purpose, objectives and priorities for sustainable management of the WELF nexus. They should define acceptable levels of water security (risk of scarcity, floods or pollution) for the communities involved, and the actions and costs required to achieve such levels. Plans should form the basis of regulations (for instance on land use, water abstraction or discharge permits) and the reference for infrastructure development and public investment. They should be backed by a robust financing strategy. Without such attributes, plans remain an ambition only and a lost opportunity.

Better manage water demand and reduce pollution

Increase water use efficiency and demand management efforts

The 2016 OECD Council Recommendation on Water – endorsed by the Korean Government – claims that demand management is the first best option to manage water scarcity. Supply augmentation is just postponing problems to a future date, as recent drought episodes in Brazil and South Africa suggest.

There are ample opportunities for Korea to increase water use efficiency (including reductions in leakage and non-revenue water) and strengthen demand management, to minimise future investment needs in water infrastructure to augment supply and to reallocate water where it creates most value to society. Well-designed water abstraction charges that reflect the opportunity cost of using water have the potential to help manage demand. The OECD report on Enhancing Water Use Efficiency in Korea: Policy Issues and Recommendations (OECD, 2017c) explores how Korea can transition towards such a system.

Water charges should be set so that they incentivise the adoption of water saving practices and technologies in agriculture, industry and households to reduce unsustainable use of water in the face of climate change. For example, the uptake of more efficient irrigation technologies, such as drip irrigation, could significantly reduce agricultural water consumption - if water saved is returned to the water system - and would also reduce pumping and energy costs and diffuse pollution risks. While improving water use efficiency is necessary to move forward a green growth strategy in agriculture, caution is required to avoid perverse effects such as: a reduction in water availability for other users and the environment, expansion of irrigated land areas with water saved, and an increased dependence on water resources and the risks associated with climate change (OECD, 2016b). Mitigating these unintended consequences of water use efficiency gains requires appropriate water accounting at the basin scale that considers not just withdrawals but also water returning to the system. Accounting for return flows should be studied more systemically to assess their relative importance in Korea’s watersheds. In a second step, return flows should be accounted for in water allocation systems to better reflect overall water supply and demand, and thus improve the efficiency of water allocation (OECD, 2015a). Thirdly, water efficiency gains should be accompanied by regulation to appropriately direct the use of saved water and prevent the perverse effects described above.

Decisions on how to operate dams and how to share water amongst agriculture, energy, industry, municipalities and the environment should be improved in Korea in order to generate more value from water. The use of reclaimed water under the Korean Construction Code and water quality “fit for purpose” should be expanded beyond greenfield projects to reduce reliance on raw water resources and provide a dependable, locally-controlled water supply. Water reuse also has the added advantage of reducing water treatment and energy costs, diverting pollution to sensitive ecosystems, returning nutrients to the land, and can be used to augment groundwater supplies.

Strengthen water quality management

Water quality is a distinctive part of the WELF nexus in Korea. Water pollution contributes to water scarcity, and affects land and energy resources. Pressures from a range of policies and developments can affect water quality, such as water allocation, flood management, urban development, alterations to the natural morphology of water bodies, land and soil management practices, agricultural support and climate change.

There are opportunities to improve the level of compliance and enforcement of effluent and discharge standards; currently, this is limited in Korea and penalties remain rare. Korea should set Environmental Quality Standards at the upper limit of acceptability to protect human health or the ecosystem and extend coverage to all streams (beyond the four major rivers). The permissible pollution load should take into account the river flow regime, the breadth of polluting substances that might adversely affect ecosystem health, and the sensitivity of the ecosystem at different places down the river, from small tributaries down to the estuary. Discharge permits should be adjusted accordingly.

Korea should expand the Korean TMDL to include a broader range of pollutants, including nitrogen and other pollutants that are of concern to human and ecosystem health in each river basin (e.g. heavy metals and pesticides), polluters (including diffuse pollution from agriculture), and tributary streams so that the Korean TMDL reaches its full potential. As a second step, Korea should consider establishing a water quality trading scheme amongst polluters within the Korean TMDL system to cost-effectively meet water quality goals whilst limiting restrictions on future economic development.

Improving the policy framework to manage livestock manure is a priority considering the future growth potential of the livestock sector. In addition to current efforts from ME and MAFRA to subsidise manure treatment and convert manure into reusable compost and fertilisers, a comprehensive policy approach beyond regulation is necessary – combining regulatory and economic incentives with capacity-building of producers and building partnerships between stakeholders. For example, Korea should: set regulations requiring good farming practices nationwide; increase education campaigns and advisory services in the farming community; establish targeted risk-based agri-environmental support payments in exchange for best farming practices (beyond mandatory good farming practices) in ecologically sensitive areas and drinking water sources; and enhance partnerships between livestock and cropping farms and industry to recycle and re-use livestock manure through on-farm application, biogas production and composting into organic fertilisers.

The River Management Fund (RMF) has significant potential to better leverage available funds to support upstream water quality projects and improve overall water quality. For example, requests to sell and retire land are oversubscribed suggesting that water quality objectives could be achieved at a lower cost. Prioritising investment decisions to achieve water quality objectives is necessary in the context of limited funding. For instance, Korea should: carefully select land that can most effectively contribute to improvements in water quality; encourage land use practices that conserve water and preserve water quality; compensate farmers for required investments or revenue losses; create demand for added-value food and fibre produced on that land (e.g. through sustainable product labelling schemes). As a final resort, land may be purchased for retirement or contractual use under strict environmental requirements if the above options have not produced intended results.

Regulate and enforce compliance

While Korea recognises the importance of using regulation to limit the exploitation or pollution of its rivers and lakes, regulation fails to deliver expected outcomes when compliance is not monitored and enforced. In Korea, regulation for agricultural water use is not systematic and with lax enforcement, and monitoring and control of groundwater abstractions is limited. In addition, the level of compliance and enforcement of effluent standards is limited and penalties remain rare; in 2013, only 35% of wastewater discharge infringements required corrective measures (ME, 2014c).

The efficiency of inspection for compliance of permits for the most polluting discharges depends on continuous monitoring of key parameters and at least daily analysis monitoring of all permitted substances. It also depends on how process failures are reported and dealt with. Smaller discharges with less risk of causing serious pollution would be subject to a less rigorous compliance monitoring regime.

To align with best international practices, and to deploy resources most effectively, Korea would be wise to adopt a risk-based approach to environmental regulation and compliance monitoring. More specifically, Korea should target compliance monitoring where the risks of non-compliance are highest, or where their consequences on human and ecosystems' health are most severe. Ideally, such an approach would be underpinned by a process of independent regulation with powers and authority to take action where necessary. This would significantly enhance citizens’ trust in the institutions involved in managing water and the WELF nexus.

Independent regulation in Korea for the protection of the environment, customers’ interests and drinking water quality may be an effective response to some of the challenges to regulating water services, including the fragmentation of roles and responsibilities in the sector, the public distrust in drinking water services, and the limitations of the tariff setting process. International best practices clearly demonstrate the multiple benefits of a clear separation between regulatory, policy making and project implementation functions. When it comes to water supply and sanitation services, regulatory functions include: i) setting and reporting on performance targets for water service providers, and ii) setting tariffs at the appropriate level to cover operational expenditures and capital investment to improve the level and standard of water supply and sanitation services. These functions can be discharged in several ways, within or outside ME, as long as they are shielded from third party interference.

Reform institutions and governance

Korea’s water security challenges are increasingly complex: they do not fit into a single ministerial portfolio; they cut across several policy areas, and spread across administrative boundaries and jurisdictions; and their resolution depends on expertise from both government and non-government actors at multiple levels.

Reform institutional coordination

Korea lacks effective vertical and horizontal coordination mechanisms across scales and stakeholders, leading to inefficiencies of both financial and physical resources and non-optimal water services provisions to citizens and private sector.

Korea should reflect basin issues in national policies as a priority. It should give increased priority to policy alignment and inter-ministerial coordination so that national and sub-national ministries and agencies are capacitated and incentivised to make co-ordination work effectively for sustainable long-term management of the WELF nexus.

The recent water governance reform through the adoption of the revised Government Organisation Act, June 2018, merges responsibilities of water quantity and quality management under one ministry (ME). This merge is a step in the right direction for improved policy alignment and coherency. However, improved coordination does not come automatically; ME will need to develop and implement a water quality and quantity “coordination” strategy for effective merging of responsibilities at national and sub-national levels.

As part of a staged institutional development approach towards strengthened cross sector coordination for the WELF nexus, ME, MoLIT and MAFRA, together with stakeholder organisations at basin level, should develop a national level inter-ministerial coordination platform to coordinate policies that affect water quality, quantity and ecology, land use planning and economic uses of water such as food and energy production. Such a platform should operate routinely without prejudice to future institutional arrangements. The objective of the platform should be to propose long-term institutional set ups for managing the WELF nexus. The platform should also open up to other government and non-government stakeholders, including from the basin level. Steps towards such a platform should include: 1) assessment and analysis of current water related responsibilities and institutional set-up at national level to identify institutional gaps and over-laps; 2) assessment of capacity development needs among both government and non-government stakeholders and financing gaps and; 3) assessment of the available skills for the delivery of policy objectives, and an action plan to address skills and resources gaps; and 4) ME to take initiative and lead national stakeholder workshop for collection of government and non-government stakeholders views and ideas on improving coordination of WELF nexus.

Under the new Framework Act on Water Management, most basin level organisations (with the exception of the five regional Construction Management Offices) have been transferred to ME responsibility. There are several coordination gains to be made by also transferring responsibilities of long-term planning under the ME at national level to organisations at the basin level.

Coordination is essentially about various stakeholders inter-acting, exchanging views and making common decisions. It is therefore important to incentivise and capacitate government officials through staff exchanges between and within ministries and basin-level organisations to encourage peer-to-peer learning for coherent approaches to WELF nexus coordination. It is proposed that ME puts in place staff capacity development programmes that encourage staff exchanges between national and basin level institutions.

Manage water and the nexus at basin level

The river basin scale is considered an appropriate level for long term water quantity and quality planning, data collection, conflict mediation and policy coordination and engagement across sectors and stakeholders. The very essence of managing water at the basin level is that the unique characteristics of each basin (varying hydrological, ecological and socio-economic opportunities and challenges) can be taken into account in the planning and implementation of river basin management plans, water use charges and investment priorities.

Stakeholder organisations at basin level should set and implement objectives, targets and priorities as part of developing river basin management plans for Korea’s four major river basins - Han, Geum, Nakdong and Yeongsan/Seomjin River systems. National water priorities should be taken into account as part of the planning process. Korea should also give special attention to the remaining 30% of medium and smaller rivers that do not fall under the current system of four river major basin areas, and to integrating surface and groundwater management policies and processes.

As part of establishing and implementing viable river basin plans, the setting of water use charges should be done at the basin level to better reflect investment needs for improved water management in the WELF nexus.

The adoption of the revised Government Organisation Act, June 2018, provides a unique opportunity for Korea to move towards managing the WELF nexus at the basin scale. The ME should undertake the following:

The proposed national coordination platform on WELF nexus (see above) should develop options for improved coordination between national and basin levels. Basin management plans need to be based on national water priorities and policies, and hence the coordination between these levels will be key for effective policy implementation.

In support of the increased emphasis on river basin delivery, ME should develop policy and process guidance (with the involvement of the basin organisations) to support consistent and coherent operational delivery, and to help maintain focus on national policy objectives.

ME should assess and analyse the existing water-related basin organisations with regard to their current capacities and future needs to effectively perform a set of proposed management functions at the basin level, such as: long-term river basin management plans, setting and managing water use charges and the River Management Fund, conflict mediation and data collection. In addition, ME should assess and analyse the entire institutional structure at basin level to identify gaps, overlaps and coordination opportunities. To be included in the assessment of the basin-level institutional structure are the River Basin Committees, River Management Committees, River Basin Environmental Offices, Regional Environmental Offices, Flood Control Offices, and River Adjustment Councils.

ME should initiate a dialogue with government and non-government stakeholders as part of developing establishing a coordination platform at basin scale that cuts across sectors and stakeholders for effective planning and implementation. For example, MoLIT retains responsibility for river bank maintenance for flood protection, land use planning and river planning, and MAFRA is responsible for water in agriculture. It is important to include non-government interest such as from water users, environmental NGOs and farmers associations. The stakeholder platforms can be under the jurisdiction of a basin organisation. ME can also look at international experiences, such as in France and/or other countries, in their development and implementation of stakeholder platforms.

Strengthen stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder engagement through inclusive national, basin or local water governance is increasingly recognised as critical to secure support for reforms, draw upon stakeholder water knowledge, raise awareness about water risks and costs, increase users’ willingness to pay, and to manage and mediate conflicts (OECD, 2015b and 2015c). Legal and policy provisions for stakeholder engagement in water management in Korea do exist, but implementation in practice remains limited. Continued development and implementation of policies and laws that assure decentralisation and wider inclusion of society into policy and planning processes is considered important for improved outcomes of water management.

For any stakeholder platform or mechanism, it is important that the design relates to its intended purposes of improving coordination of water quality and quantity management and WELF nexus. To get started, pilot stakeholder engagement initiatives should be considered and scaled up, until stakeholder coordination platforms with government and non-government actors is put in place in each of the four river basins as well as at national level.

The ME, in collaboration with MAFRA, MoLIT and the basin organisations, should undertake the following at national level, as well as in each of the four major river basins:

Promote inclusiveness and equity: Map all stakeholders who have a stake in the outcome or that are likely to be affected, as well as their core interests and capacities;

Make processes transparent and accountable: Define the objectives of stakeholder engagement and the expected use of their inputs;

Level the playing field between stakeholders: Allocate sufficient financial and human resources and share the same information with all stakeholders. Capacity development should target weaker stakeholders;

Be adaptive: Customise the type and level of stakeholder engagement depending on the objectives and characteristics of stakeholders;

Promote efficiency: Assess the outcomes of stakeholder processes on a regular basis to learn, adjust and improve; and

Institutionalise stakeholder processes: Stakeholder engagement processes should be embedded in clear policy and legal frameworks and in organisational structures and modalities with responsible government authorities.

Institutionalise stakeholder processes: Stakeholder engagement processes should be embedded in clear policy and legal frameworks and in organisational structures and modalities with responsible government authorities.

Recommendations

With the ultimate goal of achieving sustainable management of the WELF nexus in Korea, recommendations build on four priorities: 1) Anticipate and plan against future water-related risks; 2) Manage water quantity and quality; 3) Regulate and enforce compliance; and 4) Reform institutions and governance. Recommendations for each of these priorities are outlined below and in Figure 1. An Action Plan detailing how to achieve these recommendations, and suggestions of who may be responsible for them, is presented as Annex 1.A.

1. Anticipate and plan against future water-related risks

Implement a robust water quantity and quality monitoring and assessment framework

Invest in water quantity and quality monitoring and assessment.

Collect data on key issues at basin and sub-basin levels for both surface and groundwater bodies. Extend coverage of monitoring to streams not covered by the four major rivers. Routinely monitor groundwater levels and quality. Monitor water quality on a larger range of substances on a daily basis.

Identify where water scarcity, floods or pollution pose a risk to ecosystem degradation, damage to assets, or systemic risks to the WELF nexus and human well-being. Tailor the following accordingly to reduce risks: i) water abstraction and discharge permits, ii) compliance monitoring and enforcement, and iii) land use regulation.

Assess the economic and social costs and the social distribution impacts of policies, regulations and practices that relate to the WELF nexus.

Coordinate plans across sectors, and increase resilience of policies that affect the WELF nexus

Develop plans based upon plausible socio-economic and climate change scenarios to assess the strengths and weaknesses of different policy options. England and Wales offer valuable experience.

Join up land and water planning and management, preferably at basin scale, with the aim of reducing flood runoff, increasing infiltration and improving water quality.

Ensure plans drive policies and investments that contribute to the WELF nexus. Review existing water, agricultural, energy and land policy instruments to improve their coherence with policy objectives and reduce conflicting incentives.

Use resilience thinking to assess the vulnerability of systems to shocks such as extreme droughts. England and Wales offer valuable experience.

Put in place a long-term strategy to deliver drought and flood resilience with funding for drought and flood risk management matching increasing risk over the coming decades.

Ensure that water supply planning is based upon a ‘portfolio’ approach, with a range of options with different risk profiles and resilience. Lessons from Australia, and England and Wales may be useful to Korea.

Scale-up investment and innovation to improve effectiveness

Scale up the current initiatives on Low Impact Development and green infrastructure to reduce urban flood risk.

2. Better manage water demand and reduce pollution

Increase water use efficiency and demand management efforts

Implement programmes of water efficiency savings and demand management – targeted at agricultural, industrial and household users. Increase water charges to reflect the scarcity of water in basins and to incentivise water conservation. Australia, the United States and other OECD countries provide examples of good practice. Scale up efforts to reduce leakage and non-revenue water within water supply networks.

Develop a water use efficiency strategy for agriculture that explicitly prevents increases in irrigated areas and dependence on water resources where water is scarce, and ensures sufficient groundwater recharge, environmental flows, water availability for downstream users and effluent dilution. This will require: i) establishment of water accounting at the basin scale that considers not just withdrawals but also water returning to the system; ii) accounting for return flows in water allocation systems to better reflect overall water supply and demand, and thus improve the efficiency of water allocation; and iii) regulation to appropriately direct the use of water saved through efficiency gains, in order to prevent perverse outcomes.

Improve water allocation for ecological flows

Provide guidance on how introducing revised environmental flows will be carried out in practice, including reallocation of existing water rights if necessary whilst minimising tensions between users.

Strengthen water quality management

Expand the Korean TMDL to include the whole basin (including small/medium tributary rivers) and other water quality parameters linked to local ecological limits and social values on water quality.

In the longer-term, include all diffuse source polluters (including agriculture) in the Korean TMDL programme. Experience from the United States and New Zealand can guide Korea.

In the longer-term, consider replacing the water use charge with economic instruments that incentivise reductions in water pollution at lowest cost to society. Charges in France and water quality trading schemes in the United States are examples of good practice.

Use targeted, risk-based regulations to reduce diffuse source pollution of rivers, lakes and groundwater, such as mandating livestock units’ manure management and good management practices. Experience from the EU Nitrate pollution prevention regulations is relevant.

Harness voluntary action and improve education

Use agri-environmental support payments or payment for ecosystem services in exchange for the uptake of best farming practices in ecologically-sensitive or drinking water catchment areas. Germany and the United Kingdom offer examples of good practice.

Increase education campaigns and advisory services in the farming community as a precursor to introducing regulations.

3. Regulate and enforce compliance

Strengthen compliance monitoring and enforcement capacity

Adopt a risk-based approach to regulation and compliance monitoring.

Establish independent monitoring, auditing and reporting of drinking water quality.

Introduce permit controls on all abstractions as part of a reformed water allocation regime. Commence groundwater permitting on a risk basis, including an assessment of interference between boreholes and their impact on surface waters, the risk of saline intrusion, and to ensure that total groundwater abstraction is kept within sustainable limits (i.e. doesn’t exceed recharge).

Ensure compliance monitoring assesses and manages the total pollution load, and accounts for the river flow regime and the sensitivity of the ecosystem at different places down the river. The European Union Water Framework Directive is an example of good practice.

Establish independent regulation with strong regulating powers

Consider the benefits of independent regulation for the protection of the environment, customers’ interests and drinking water quality with powers to take action where necessary against breaches of permits and standards, and to set tariffs at the appropriate level to cover operational expenditures and capital investment to improve the level and standard of water supply and sanitation services.

4. Reform institutions and governance

Reform institutional coordination

Reflect basin issues in national policies as a priority. Give increased priority to policy alignment and inter-ministerial coordination so that national and sub-national ministries and agencies are capacitated and incentivised to make co-ordination work effectively along the management of WELF-nexus.

Develop and implement a water quality and quantity “coordination” strategy for effective merging of the issues at national and sub-national levels.

Put in place an inter-ministerial stakeholder platform at national level to coordinate policies within ME, MoLIT and MAFRA that affect river management, including water quality, quantity and ecology, land use planning and economic uses of water such as food and energy production. Other government and non-government stakeholders should be invited to be part of such a platform.

Incentivise and capacitate government officials to interact between and within ministries and government departments, exchange views and make common decisions on the WELF nexus. This could be facilitated through staff exchanges and peer-to-peer learning.

Create a stakeholder engagement framework

ME should engage with stakeholders, government and non-government, to strengthen the basin level management of WELF nexus and to reflect basin issues in national policies and priorities. International experiences (such as France, the Netherlands and Canada) offer examples of good practices.

Establish stakeholder coordination platforms in each of the four river basins as well as at national level with government representatives and non-government actors. This will require: 1) define the objectives of stakeholder engagement and the expected use of inputs; 2) customise the type and level of stakeholder engagement depending on objectives and characteristics of stakeholders and; 3) map stakeholders and their core interests and capacities. Stakeholder platforms should as a minimum fulfil basic criteria of inclusiveness, transparency and that all stakeholders have access to the same information. In the transition to the establishment of formal stakeholder coordination platforms, ME should scale up pilot stakeholder engagement processes.

Invest in stakeholder processes and provide financial and capacity development support, especially to weaker stakeholder groups.

Transition to basin-level governance

Assess and analyse the River Management Committees (RMCs) with regard to their current capacities and future needs to effectively perform a set of proposed management functions at the basin level. In addition, assess and analyse the entire institutional landscape at basin level to identify gaps, overlaps and coordination opportunities. Consider merging RMCs with the River Basin Committees (RBCs) to form a combined basin organisation for water management in each of the four major river basins of Korea.

Devolve water management functions to the basin level. RBCs should set and implement objectives, targets and priorities as part of developing and implementing river basin management plans for Korea’s four major river basins. Transferred responsibilities should include the development and implementation of river basin management plans, financing and investment strategies, setting of water and pollution charges, data collection and mediation of basin water-related conflicts. National water priorities should be taken into account as part of the planning process.

Develop policy and process guidance (with the involvement of the RBCs) to support consistent and coherent operational delivery, and to help maintain focus on national policy objectives. Oversee delivery in order to promote the sharing of good practice.

Establish coordination platforms at basin scale that cuts across sectors and stakeholders for effective planning and implementation.

Figure 1. Achieving sustainable management of the WELF nexus in Korea

References

ME (2015), Ecorea: Environmental Review 2015: Korea, Ministry of Environment, Sejong. http://eng.me.go.kr/eng/web/board/read.do?pagerOffset=0&maxPageItems=10&maxIndexPages=10&searchKey=&searchValue=&menuId=30&orgCd=&boardId=565930&boardMasterId=547&boardCategoryId=&decorator=.

ME (2014a), Introduction to NPS pollution management in Korea. In: Presented at the International Symposium for the 22nd Anniversary of World Water Day. National Institute of Environment Research, Incheon, South Korea.

ME (2014b), “The Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity”, Ministry of Environment, Sejong. www.cbd.int/doc/world/kr/kr-nr-05-en.pdf.

ME (2014c), Environment Statistics Yearbook, Ministry of Environment, Sejong, http://webbook.me.go.kr/DLi-File/091/020/003/5588561.pdf.

OECD (2018, forthcoming), Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2017a), The Land-Water-Energy Nexus: Biophysical and Economic Consequences, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279360-en.

OECD (2017b), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Korea 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268265-en.

OECD (2017c), Enhancing Water Use Efficiency in Korea: Policy Issues and Recommendations, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264281707-en.

OECD (2017d), Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters: Emerging Policy Solutions, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264269064-en.

OECD (2017e), Water Risk Hotspots for Agriculture, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279551-en.

OECD (2016a), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-kor-2016-en.

OECD (2016b), Mitigating Droughts and Floods in Agriculture: Policy Lessons and Approaches, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264246744-en.

OECD (2015a), Water Resources Allocation: Sharing Risks and Opportunities, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264229631-en.

OECD (2015b), Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264231122-en.

OECD (2015c), OECD Water Governance Principles, www.oecd.org/gov/regional-policy/OECD-Principles-on-Water-Governance-brochure.pdf.

OECD (2010), Agricultural Water Pricing: Japan and Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264083578-13-en.

Tidwell, V. and B. Moreland (2016), Mapping water consumption for energy production around the Pacific Rim, Environmental Research Letters (2016) 094008.

Annex 1.A. Recommended Action Plan

This Action Plan identifies key steps for the implementation of the main policy recommendations and ways forward set out in this report. The ultimate goal is to create the conditions for the effective design and efficient implementation of water and WELF-related policies in a shared responsibility across levels of government, but also across public, private and non-profit sectors.

In practice, all of these measures will not materialise at once. The Action Plan suggests champions or institutions that can lead implementation over the short-, medium- and long-terms. The critical issue is whether the momentum created by the policy dialogue can continue, and an iterative and incremental process leads to improved management of the WELF nexus to deliver expected benefits for Korea. The process will facilitate reviews and revisions so that the system improves over time as more information about water resources, their use and the consequences of policies becomes available.

Annex Table 1.A.1. Action Plan for achieving sustainable management of the WELF nexus in Korea

|

Objective |

Action |

Possible champions/partners |

Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Anticipate and plan against future water-related risks |

|||

|

Implement a robust water quantity and quality monitoring and assessment framework |

Review location (e.g. downstream of effluent discharges, tributaries and coastal rivers), frequency (to understand daily and seasonal variability and total load) and parameters (e.g. metals, organics, pharmaceuticals) in water quality monitoring. |

ME |

Short-medium |

|

Review location (e.g. downstream of major effluent discharges, tributaries, and coastal rivers), frequency and comprehensiveness of ecological monitoring. Aim to understand current state of ecology in entire basin and progress towards target ecological status. |

ME |

Short-medium |

|

|

Review river flow monitoring, together with abstraction and discharge volumes, in order to generate a naturalised flow sequence to support development of environmental flow targets. |

ME, with MAFRA, MoTIE, MoLIT |

Short-medium |

|

|

Review groundwater level and quality monitoring network and data collection from pumping to better understand impact of abstraction and surface water-groundwater interaction and adjust regulation and entitlements accordingly. |

ME, with MAFRA |

Short-medium |

|

|

Use monitoring information on the state of the environment, and the pressures on it, to establish an integrated plan with costed measures for its protection and improvement |

ME |

Medium |

|

|

Coordinate plans across sectors, and increase resilience of policies that affect the WELF nexus |

Develop balanced twin-track long-term plans (at least 25 years ahead) for water supply for each river basin, with demand management integral to the strategy, to deliver agreed levels of service across all sectors. Plans should: i) be tested on a range of socio-economic and climate scenarios, incorporating unprecedented events, ii) consider a menu of options with different risk profiles and resilience, and iii) coordinate initiatives across the WELF nexus. |

ME, with MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, MPSS |

Short-medium |

|

Assess the impact on water users from the introduction of e-flows, and appraise options for maintaining supply security without compromising environmental standards. |

ME, with MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE |

Medium |

|

|

For each river basin, develop a drought plan, which would set out an agreed series of actions to be escalated as a drought worsens, supported by EIAs to understand and mitigate impacts, in order to ensure a proactive approach to drought risk management. |

RBCs, with ME, MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, MPSS, MoI, |

Short-medium |

|

|

For each water supply and urban area, use international good practice to assess resilience against shocks (e.g. droughts, floods, cyber-attacks, human error, natural disasters), and take action to minimise the duration and impact from such events. |

RBCs, with ME, MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, MPSS |

Medium |

|

|

Aim to consolidate plans where possible into a single integrated process, in order to exploit synergies and opportunities, and reduce conflicting incentives. Join up land and water planning and management, preferably at basin scale, with the aim of reducing flood runoff, increasing infiltration and improving water quality. |

RBCs, with ME, MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, MoI, Prime Minister's Office |

Medium |

|

|

Carry out ex post assessments of all major water-related developments and ensure that lessons are incorporated into future planning and investment. |

ME |

Short-medium |

|

|

Scale up investment and innovation to improve effectiveness |

Adopt international good practice on green-blue cities in order to accelerate the pace of introduction of Low Impact Development, Working with Natural Processes principles, and more effective controls on land use. |

ME and MoLIT |

Medium-long |

|

Better manage water demand and reduce pollution |

|||

|

Better manage water demand |

Manage groundwater proactively, and introduce abstraction controls on wells and boreholes. |

ME, with MAFRA |

Medium |

|

Introduce abstraction permitting for all surface water abstractions (perhaps above a certain volume threshold) and set permits to ensure compliance with e-flows and to drive water efficient behaviour. |

ME, with MAFRA |

Medium |

|

|

Proactively monitor and enforce compliance with abstraction permits, taking a risk-based approach. |

ME, with MAFRA |

Short-medium |

|

|

Aim to reduce leakage to international good practice. Establish benchmarking and target setting to help drive leakage reduction and provide a focus on asset condition and repair. |

ME |

Medium-long |

|

|

Introduce water charges for abstraction and water pollution, at the basin scale, reflecting environmental externalities and the opportunity cost of using water. |

RBCs, with ME, MoSF, MoI |

Medium-long |

|

|

Develop a water use efficiency strategy for agriculture that explicitly prevents increases in irrigated areas and dependence on water resources where water is scarce, and ensures sufficient groundwater recharge, environmental flows, water availability for downstream users and effluent dilution. This will require: i) establishment of water accounting at the basin scale that considers not just withdrawals but also water returning to the system; ii) accounting for return flows in water allocation systems to better reflect overall water supply and demand, and thus improve the efficiency of water allocation; and iii) regulation to appropriately direct the use of water saved through efficiency gains, in order to prevent perverse outcomes. |

MAFRA, ME, RBCs |

Short-medium |

|

|

Improve water allocations for the environment (e-flows) |

Develop a strategy on how introducing revised environmental flows will be carried out in practice, including reallocation of existing water rights if necessary whilst minimising tensions between users. |

ME, with MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, RBCs |

Short-medium |

|

Strengthen water quality management |

Use improved water quality monitoring data to model current state of catchments, identify hotspots, and to then control all inputs of a pollutant (using permits for point sources, alternative mechanisms for diffuse sources) so that total load does not exceed environmental capacity (dilution and ecological sensitivity) at any location. |

ME, with MAFRA, RBCs |

Medium |

|

Proactively monitor and enforce compliance with discharge permits, taking a risk-based approach. |

ME |

Short-medium |

|

|

Step up efforts with the farming sector to reduce fertiliser and pesticide use, and to improve manure management, specifically on land that affects water quality most (e.g. riparian land, permeable land above shallow aquifers, land in close proximity to drinking water sources and sensitive ecosystems). Consider different policy options to deliver reductions in pollutant load (e.g. expanding Korean TMDL, pollution charges, water quality trading, payments for ecosystem services). |

MAFRA, with ME, RBCs |

Medium |

|

|

Determine an official list of good and best farm management practices to reduce diffuse pollution risks to surface and groundwater, with the aim of making good practices mandatory and best practice voluntary. |

MAFRA, with ME |

Short- medium |

|

|

Phase out the water use charge, which does not reflect the amount of pollution, nor the polluter-pays principle, and exempts agriculture. |

ME |

Medium |

|

|

Harness voluntary action and improve education |

Actively promote more efficient use of water (and the reasons why this is necessary) and reductions in water pollution to householders, industry and farmers, setting targets if necessary. |

RBCs, with ME, MAFRA |

Medium |

|

Set up payments in exchange for the voluntary uptake of best farm management practices to improve water quality. |

ME, with MAFRA and RBCs |

Medium-long |

|

|

Regulate and enforce compliance |

|||

|

Strengthen compliance and enforcement capacity |

Adopt a risk-based approach to regulation and compliance monitoring to focus on where there is greatest risk to the environment, public health, the economy, other water users, or of non-compliance by the operator. |

ME, with MAFRA and RBCs |

Medium |

|

Review the need to commence groundwater permitting on a risk basis, including an assessment of interference between boreholes and their impact on surface waters, the risk of saline intrusion, and the overall sustainability of abstraction in each aquifer unit. Consider the use of test pumping and numerical models as aids to decision making. |

ME, with MAFRA and RBCs |

Short-medium |

|

|

Introduce permit controls on all abstractions as part of a reformed water allocation regime. Establish a mechanism to ensure that permitting policy can adapt as rainfall, river flows, groundwater yields and human demands change over time, so that it becomes flexible and adaptive, and able to maintain sustainable exploitation of natural resources. |

ME, with MAFRA and RBCs |

Medium |

|

|

Ensure compliance monitoring assesses and manages the total pollution load, and accounts for the river flow regime and the sensitivity of the ecosystem at different places down the river. The European Union Water Framework Directive is an example of good practice. |

ME, with MAFRA and RBCs |

Short-medium |

|

|

Ensure inspection and control mechanisms as well as sanctions and penalties in case of non-enforcement and compliance. Depending on the severity of the breach, and the attitude of the permit holder, this could range from a verbal warning, to a written warning, to sanctions or a fine, or criminal prosecution. If necessary, use enforcement mechanisms to set an example of persistent poor compliance, and publicise the action taken as a warning to others. |

ME, with MAFRA and RBCs |

Short-medium |

|

|

Carry out inspections and audits of reported water abstraction when water charges are set on self-reported water abstraction. Ensure that the inspection visit raises awareness of the consequences of non-compliance. |

MAFRA, with ME |

Short-medium |

|

|

Promote regular monitoring and evaluation of the adequacy, implementation and results of water policies to assess to what extent they fulfil the intended outcomes and adapt where needed. |

ME, with MAFRA and RBCs |

Short-medium |

|

|

Establish independent regulation with strong regulating powers |

Ensure that environmental regulation is independent and coordinated across all basins, and that it operates consistently and fairly so that poor performers are targeted and permit standards enforced. |

ME, with RBCs |

Medium |

|

Look after customers’ interests by establishing independent regulation to ensure that all aspects of water supply are operating efficiently, are delivering to agreed levels of service, and are responding to complaints. |

ME, with RBCs |

Medium |

|

|

Establish independent regulation of drinking water quality compliance, and publish information on the performance of each supply, and details of enforcement action taken against any breaches of standards. |

ME, with RBCs |

Medium |

|

|

The establishment of independent and trusted water regulation for the protection of the environment, customers’ interests and drinking water quality can be discharged in several ways, within or outside of ME - as long as they are shielded from third party interference. This includes ensuring a clear separation between regulatory, policy making and project implementation functions. |

ME |

Medium |

|

|

Reform institutions and governance |

|||

|

Reform institutional coordination |

Establish inter-ministerial stakeholder platform at national level for improved coordination of WELF nexus and river management, including water quality and quantity management. Steps towards such a platform should include to: 1) Assess and analyse current water related organisational mandates and responsibilities, policy gaps and overlaps at national level; 2) Review national water policy and organisational frameworks in relation to shifting managerial responsibilities (e.g. planning, conflict mediation, data collection, etc.) to basin level organisations (e.g. RBCs); 3) Assess capacity development and financing needs and opportunities among both government and non-government stakeholders and; 4) Organise a series of national stakeholder workshops and dialogues for trust-building and to collect government and non-government stakeholder views and ideas on the design of a stakeholder platform to improve coordination of WELF nexus. OECD Principles on Water Governance and related indicator framework can be used as a voluntary tool to facilitate stakeholder dialogues. Expected outcomes of activities 1-4 are: Establish national joint vision, objectives and strategies for improved WELF nexus coordination across sectors and stakeholders; proposal developed on the design (roles and responsibilities, composition, and financing) of national stakeholder platform. |

PMO, ME, MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, RBCs, local and regional governments local community representatives, academia, water user groups, NGOs, private sector, etc. |

Short-medium |

|

Initiate and promote government staff exchange programmes between national and basin levels to promote coordination of the WELF nexus. |

ME, RBCs |

Short-medium |

|

|

Assign clear divisions of roles and responsibilities between ME and MoLIT for effective implementation of coordinated management of water quantity and water quality at both national and basin levels. |

PMO, ME, MoLIT, RBCs |

Short-Medium |

|

|

Create a stakeholder engagement framework |

To establish stakeholder coordination platforms (at both national and basin levels), ME should in broad consultations with government and non-government stakeholders: 1) Map and assess stakeholders (ministries, local and regional government, NGOs, private sector, academia, community representatives, etc.) and their core interests and capacities; 2) Define the objectives of stakeholder engagement and the expected use of inputs and; 3) Customise the type and level of stakeholder engagement depending on objectives and characteristics of stakeholders. Stakeholder platforms should as a minimum fulfil basic criteria of inclusiveness, transparency and that all stakeholders have access to the same information. |

ME, with MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, RBCs, local and regional governments local community representatives, academia, water user groups, NGOs, private sector, etc. |

Short-medium |

|

Develop and design capacity-development programmes targeting different constituencies for more effective participation in stakeholder engagement processes. Provide incentives in the form of small grants (travel grants, grants for holding local stakeholder meetings, etc.) for which stakeholders (non-government in particular) can apply to improve their capacities to take part in stakeholder processes. Stakeholders with weaker capacities should be prioritised. |

ME, with MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, RBCs, local and regional governments local community representatives, academia, water user groups, NGOs, private sector, etc. |

Short-medium |

|

|

Formalise stakeholder engagement in law and organisation rules and procedures to shift from an ad-hoc based to a structured process at 1) national level and: 2) river basin level. |

PMO, ME, MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, RBCs |

Long |

|

|

Transition to basin-level governance |

Devolve water management responsibilities at the basin level to RBCs. Steps towards such an ambition should include: 1) Consider merging River Management Committees (RMCs, formerly under the remit of MoLIT) with the River Basin Committees (RBCs, under the remit of ME) to form a combined basin organisation for water management in each of the four major river basins of Korea. 2) Establish a vision, objectives and implementation strategies for managing water at basin scale by: Reviewing the functions, mandate, composition and capacity of RMCs and RBCs, and assessing capabilities for data collection, river basin management planning, conflict mediation, setting and managing water user charges, stakeholder engagement and financial viability. 3) Assess and identify institutional overlaps, and management and economic efficiency opportunities at the basin scale for improved coordination among: the RBCs, River Basin Environmental Offices, Regional Environmental Offices, Flood Control Offices and River Adjustment Councils. 4) Review mandates, stakeholder processes and compositions of river basin organisations in other OECD countries to consider which elements may benefit Korea. Undertake study tours (to France and/or other countries) for peer-learning on establishing responsibilities and functions of river basin organisations. |

ME, with MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, RBCs, local and regional governments local community representatives, academia, water user groups, NGOs, private sector, etc. |

Short-medium |

|

Expected outcomes of activities 1-4 are: Establish mandate for and design of joint vision, objectives and strategies for improved WELF nexus coordination across sectors and stakeholders; and proposal developed on the design (roles and responsibilities, composition, and financing) of basin level stakeholder platform and the role of central government to support RBCs. |

|||

|

Formalise devolvement of water management responsibilities at the basin level to RBCs in law and organisational rules and procedures to shift from an ad-hoc based to a structured process of stakeholder engagement. |

PMO, ME, MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, RBCs |

Long |

|

|

Develop and oversee the implementation of policy and process guidance to ensure a consistent and coherent approach to river basin planning and the delivery of actions in support of policy objectives. |

ME, with RBCs, MAFRA and MOLIT |

Long |

|

|

Assign clear divisions of roles and responsibilities between ME and MoLIT for effective implementation of coordinated management of water quantity and water quality at basin level (See above for similar recommendation. These actions should be combined). |

PMO, ME, MoLIT, MAFRA, MoTIE, RBCs |

Short-medium |

|