Effective design and implementation of corporate governance policies requires a good empirical understanding of the ownership and business landscape to which they will be applied. Chapter 1 therefore provides a global overview of developments related to stock markets, including their size, activities and ownership characteristics. The chapter also analyses corporate sustainability-related policies and practices, based upon new information collected for this edition in line with the new chapter of the revised G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. This includes regulatory frameworks on sustainability disclosure, policies and practices for assurance of sustainability-related information and use of an international disclosure standard. It also refers to provisions on board responsibilities for sustainability-related policies as well as practices on board committees responsible for sustainability-related issues and executive compensation linked to sustainability matters. The chapter also includes newly collected information on regulatory frameworks on ESG rating and data providers.

OECD Corporate Governance Factbook 2023

1. Global markets, corporate ownership and sustainability

Abstract

1.1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of developments in equity and corporate bond markets worldwide including in the global landscape of listed companies and in the use of public equity via initial and secondary public offerings. It also offers an overview of the ownership structure of listed companies and of the use of corporate bonds in global capital markets. Finally, the chapter presents recent developments in corporate governance frameworks and corporate practices in relation to sustainability issues. The information presented in this chapter has a global coverage beyond the 49 jurisdictions covered in the Factbook and provides context for the information presented in the following chapters.

1.2. Global trends in equity markets and the listed company landscape

Equity markets offer companies access to the risk-willing, long-term capital needed in order to invest and ultimately contribute to economic growth. They also offer a secondary market that allows companies to continue accessing perpetual capital after their initial listing. In addition, equity markets contribute to the broader resilience of our economies. In times of crisis, when bank lending tends to contract, equity markets continue offering capital. Equity markets also remain the largest asset class available to households, offering the opportunity to manage their savings and share in the growth of the corporate sector.

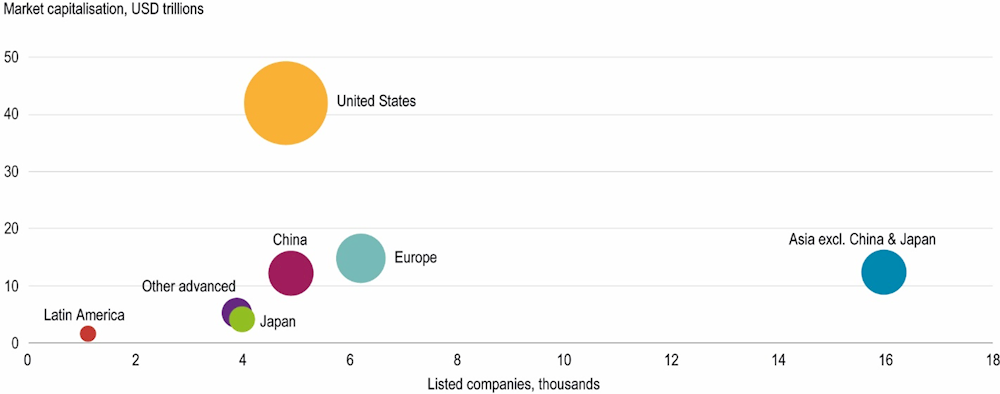

At the end of 2022, there were almost 44 000 listed companies in the world with a total market capitalisation of USD 98 trillion. Company ownership data are available for 30 871 of these companies. Figure 1.1 provides a picture of the size of the key markets and regions according to the number of listed companies and market capitalisation for all listed companies. The United States remains the largest market by market capitalisation, while Asia has the highest number of listed companies.

Figure 1.1. Universe of listed companies, end 2022

Note: The figure shows the market capitalisation and number of listed companies for the 43 970 listed companies from 100 economies, and the bubble size represents their share in global market capitalisation. In this and subsequent figures in this chapter and in the text when specified, the category “Asia excl. China and Japan” includes all jurisdictions in the continent excluding the People’s Republic of China (hereafter ‘China’ and Japan (e.g. Hong Kong (China); India; Korea; Singapore; and Chinese Taipei). “Latin America” includes jurisdictions both in Latin America and in the Caribbean. “Europe” includes all jurisdictions that are fully located in the region, including the United Kingdom and Switzerland but excluding the Russian Federation and Türkiye. “Other Advanced” includes all jurisdictions that are classified as advanced economies in IMF’s World Economic Outlook Database but that are not represented in the other categories in the figure (e.g. Australia, Canada, and Israel). “Others” includes mostly jurisdictions that are classified as emerging market and developing economies in IMF’s World Economic Outlook Database but that are not represented in the other categories in the figure (e.g. Saudi Arabia and South Africa). See the Methodology for Ownership data in Annex 1.A for more detailed information.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

Global market capitalisation increased from USD 84 trillion in 2017 to USD 98 trillion in 2022, while the number of listed companies increased from approximately 41 000 in 2017 to almost 44 000 in 2022. This increase was mainly driven by emerging economies, where the number of listed companies increased from around 16 000 in 2017 to over 20 000 in 2022. On the contrary, many advanced economies have seen a continuous decrease in the number of listed companies, mainly driven by a substantial and structural decline in listings of smaller growth companies, distancing a larger portion of these companies from ready access to public equity financing.

Table 1.1 provides an overview of the total market capitalisation and number of listed companies across the 49 Factbook jurisdictions, including OECD, G20 and Financial Stability Board members. It is important to note that the Factbook and data of Table 1.1 by jurisdiction focus on companies that issue equity on the regulated or main markets. Recognising that some jurisdictions have a significant number of companies in alternative market segments which may provide relevant opportunities for SME and growth company financing, Box 1.1 provides an overview of these alternative market segments for selected jurisdictions. However, more comprehensive data on these alternative segments have not been included in Table 1.1, recognising that they present methodological challenges that would require further study to ensure data comparability across jurisdictions, as well as to develop a clear understanding regarding the corporate governance frameworks applied to such markets.

Table 1.2 provides a breakdown of the largest stock exchanges in each jurisdiction and their characteristics.

Box 1.1. The rise of alternative market segments

The Factbook in its figures and tables focuses on companies that issue equity on the regulated or main markets and the legal, regulatory and institutional framework that applies to listed companies. Alternative market segments, however, have been established across jurisdictions and are becoming an increasingly common listing alternative as they have widened available options for issuers and investors and allow SME and growth company financing.1. At the same time, comparability of alternative market segments around the world is challenging, as their listing requirements, reporting obligations, as well as the frameworks that apply to companies on these markets are fragmented. Without aiming to provide an exhaustive overview, the selected examples listed below wish to acknowledge the growing relevance of alternative market segments and their differences.2.

Multilateral Trading Facilities (MTFs) in Europe and growth segments in other regions generally impose simplified requirements for listing. SME Growth Markets (GMs) have been established in the European Union, further to MiFID I and MiFID II, to cater to the needs of small and medium-sized issuers. These markets are not considered as a regulated market per EU legislation. Companies listing in these markets are subject to different regulatory frameworks, depending on each of these market segments and trading venues.

Euronext Growth is a market segment within the Euronext network tailored for SMEs that aim to raise funds to finance their growth. With simplified eligibility for listing and reporting requirements compared to those of the regulated market, Euronext Growth counts several companies in its different venues (Brussels, Dublin, Lisbon, Milan, Oslo and Paris).3. Such segments represent an important share of listings as there are more than 290 and 260 issuers on Euronext Growth Paris and Euronext Growth Milan, respectively.4. Another important reality is Nasdaq First North Growth Market which is an MTF. Nasdaq First North Growth Market counts over 550 traded growth companies, which are subject to the rules of different segments of First North MTF but not the requirements for admission to trading on a regulated market.5.

The Alternative Investment Market (AIM) is a UK MTF operated by the London Stock Exchange group within the meaning set out in the Handbook of the FCA and is recognised as an SME GM.6. AIM opened in 1995 and is operated and regulated by the Exchange in its capacity as a Recognised Investment Exchange. It provides a platform for smaller and growing companies to raise capital. Overall, AIM has more relaxed entry and listing requirements than the Standard Main market: for example, there is no need to file a prospectus to the FCA and no minimum free float requirement.7.

Beyond Europe, notable examples of alternative market segments can be found in China with the SSE Star Market of the Shanghai Stock Exchange launched in 2019, which counted more than 500 companies as of the end of 2022.8. This market supports companies in the science and technology field. Another market in China is the ChiNext market of Shenzhen Stock Exchange which represents a platform to support innovation among growing companies in emerging and strategic industries.9.

In Korea, the Korea Exchange (KRX) offers two segments for SMEs. One is the KOSDAQ market launched in 1996 to provide funds for startup companies and SMEs in the technology sector and now extending its scope to other growth industries, and the other one is the KONEX (Korea New Exchange), a new segment established in 2013 targeted to SMEs.10.

Overall, alternative market segments, including MTFs and SME GMs, support market dynamism and capital markets growth, but given their different characteristics, they would require further study to provide more comprehensive and comparable data across jurisdictions, as there is significant variation in how these market segments are defined and which rules apply to them across the Factbook jurisdictions.

Notes:

1. The Federation of European Securities Exchanges (FESE) estimated that at the end of 2022, for its 16 full members from 30 jurisdictions, there were 1 502 companies listed on specialised market segments in equity (FESE, 2022[1]).

2. For an analysis of which variables may contribute to differences among different trading venues for SMEs limited to EU jurisdictions, see (Annunziata, 2021[2]).

3. An overview of eligibility criteria and ongoing obligations on the different venues of Euronext Growth is available. Euronext Growth Oslo is not registered as an SME Growth Market under EU regulation.

4. The list of stocks for Euronext Growth Paris can be accessed here and the list for Euronext Growth Milan is available here.

5. Nasdaq First North Growth Market is a market operated by Nasdaq Stockholm (Nasdaq First North Growth Market Sweden), Nasdaq Copenhagen (Nasdaq First North Growth Market Denmark), Nasdaq Helsinki (Nasdaq First North Growth Market Finland) and Nasdaq Iceland (Nasdaq First North Growth Market Iceland). See general information and the Rulebook for issuers of shares on Nasdaq First North GM.

6. See AIM Rules for Companies.

7. An overview of entry, listing, trading and other obligations of AIM is provided on the London Stock Exchange’s website.

8. See an overview of the STAR Market, its listings and the Rules Governing the Listing of Stocks on the Science and Technology Innovation Board of Shanghai Stock Exchange.

9. See an overview of the ChiNext market.

10. See an overview of the criteria and listing requirements for KOSDAQ market and for the KONEX market. Up to date figures on the different market segments of the Korea Exchange (KRX) are provided here.

1.3. Initial public offerings trends

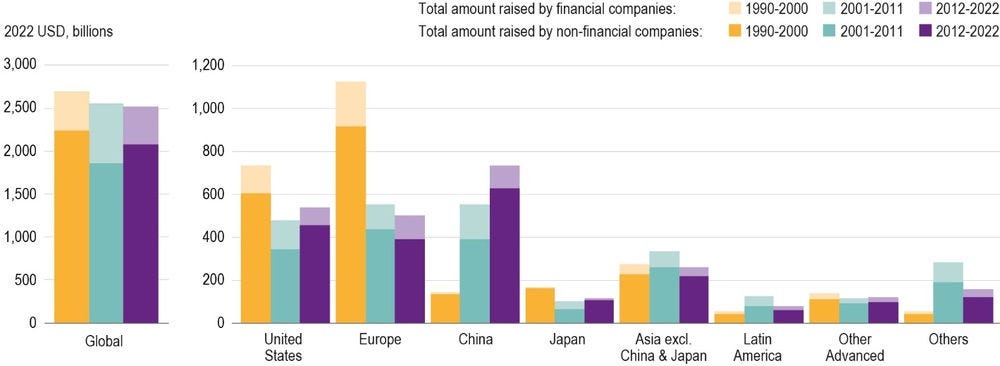

Since the mid‑1990s, the public equity market landscape has undergone important changes. One important development has been an increasing use of public equity markets by Asian companies. In the 1990s, European non-financial companies – mainly from the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Italy – played a leading role in the global scene in terms of initial public offerings (IPOs), accounting for 41% of all capital raised, with over 3 500 listings during that period. Since then, European IPOs have declined both in absolute and relative terms. European non‑financial companies raised only 24% of the total equity capital raised via IPOs during the 2001‑11 period, dropping to 19% between 2012 and 2022 (Figure 1.2).

Asian companies have significantly increased their participation in global equity markets, from raising 22% of global IPO proceeds during the 1990s to 44% during the 2012‑22 period. Importantly, the capital raised by non‑financial companies in Asia has surpassed that of financial companies. The growth of Asian markets is mainly the result of a surge in Chinese IPOs. The number of Chinese IPOs more than tripled between the 1990‑2000 period and the 2012‑22 period, and they now represent almost one‑third of the global proceeds. The Japanese market, which in 2001‑11 experienced a decline in total IPO proceeds compared to the 1990s, saw a 15% increase during 2012‑22, which also contributed to the increased importance of Asian equity markets during the past decade. The participation of Latin American companies in global capital markets has declined, with their amount of capital raised via IPOs contracting by 38% between 2001‑11 and 2012‑22.

The surge in IPOs of Asian companies has led to an increase in the share of Asian listed companies in all listed companies. At the beginning of 2023, 56% of the world’s listed companies were listed on Asian stock exchanges, together representing 30% of the market capitalisation of the world’s listed companies.

Figure 1.2. Initial public offerings (IPOs), total amount raised

Note: Initial public offerings in this report are defined as those listing on the main market where the capital raised is greater than zero. Therefore, direct listings are not recorded as an IPO in this database. The figure shows data for companies doing an initial public offering domiciled in 205 economies. More detailed information is provided in the Methodology for Public equity data in Annex 1.A of this Chapter.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

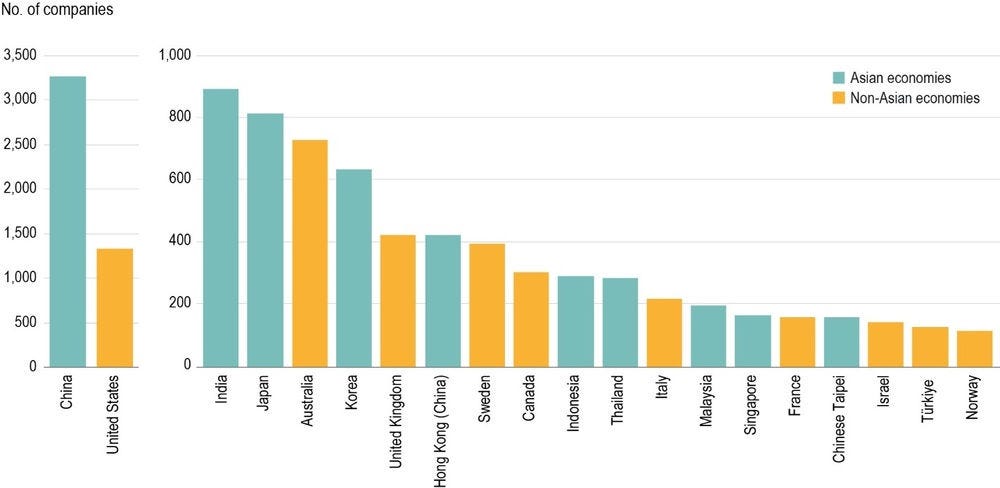

The shift towards Asia has been even more pronounced with respect to the number of IPOs by non‑financial companies. Chinese non‑financial companies have been the world’s most frequent users of IPOs during the past decade, with about two and a half times as many IPOs as US companies (Figure 1.3). Moreover, other Asian markets – India, Japan, Korea and Hong Kong (China) – also rank among the top ten IPO markets globally. Importantly, several emerging Asian markets (shown in blue in Figure 1.3), such as Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia, rank higher in terms of IPOs than most advanced non-Asian economies (shown in orange). Only one EU member state – Sweden – is in the top ten.

Figure 1.3. Top 20 jurisdictions by number of non-financial company IPOs between 2013 and 2022

Note: The figure shows data for the top 20 economies by total number of initial public offerings. Companies are recorded by their domicile, not where they list. More detailed information is provided in the Methodology for Public equity data in Annex 1.A of this Chapter.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

1.4. Secondary public offerings trends

Secondary public offerings (SPOs or follow-on offerings) allow companies that are already listed to continue raising equity capital on primary markets after their IPO. The proceeds from the SPO may be used for a variety of purposes and can also help fundamentally sound companies to bridge a temporary downturn in economic activity. In this regard, SPOs played an important role in providing the corporate sector with equity in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis as well as during the COVID‑19 crisis.

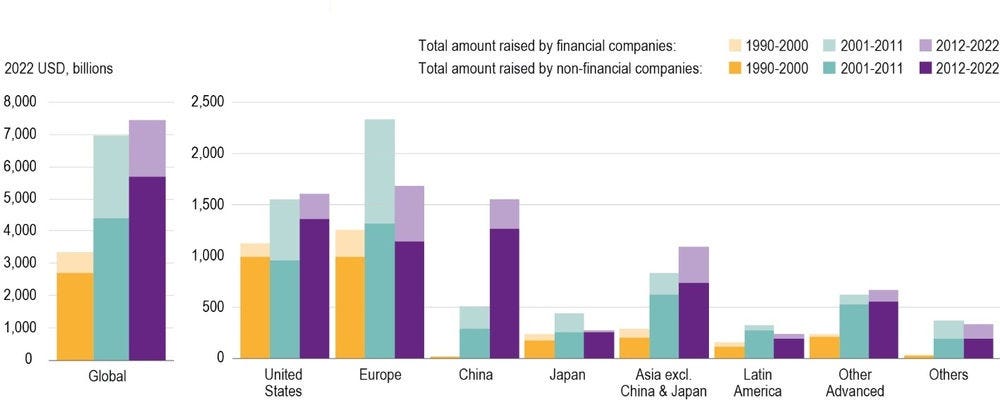

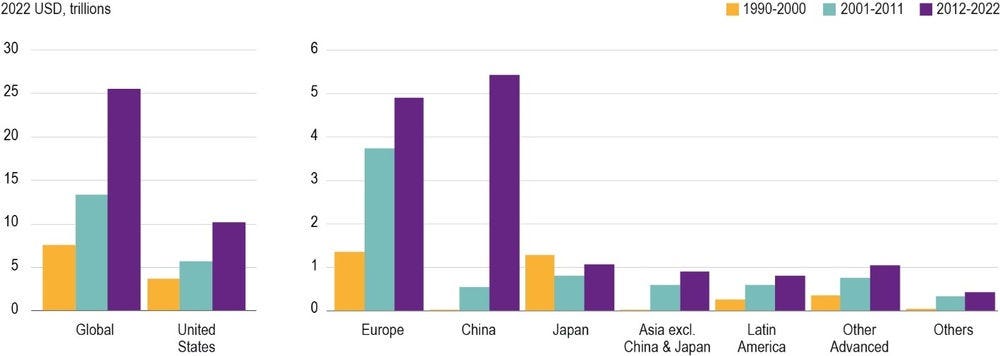

The use of SPOs as a source of financing has gained momentum over the last two decades. In 2020, non‑financial companies raised a record USD 708 billion via SPOs. The proceeds raised between 2012 and 2022 worldwide totalled USD 7.4 trillion, which is more than twice the amount raised during the 1990s. All regions experienced an increase in the use of SPOs (Figure 1.4). In Europe and the United States – the dominant regions in terms of SPO volume – the proceeds increased by over one‑third between 1990‑2000 and 2012‑22. While the use of SPOs was marginal in China during the 1990s, Chinese companies raised USD 1.55 trillion in equity through SPOs between 2012 and 2022, which represents 21% of the total equity raised in the world through SPOs during that period.

Figure 1.4. Secondary public offerings (SPOs), total amount raised

Note: All public equity listings following an IPO, including the first-time listings on an exchange other than the primary exchange, are classified as a SPO. The figure shows data for 206 economies. More detailed information is provided in the Methodology for Public equity data in Annex 1.A.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

The steady growth in SPOs worldwide has also shifted the importance of public equity financing from IPOs to SPOs with respect to the total funds raised. While in the 1990s, SPOs accounted for half of the proceeds raised in public equity markets (IPOs and SPOs combined), since the early 2000s this share has been increasing, reaching a record 89% of the total proceeds in 2009. The United States and Europe experienced both a decrease in IPOs and an increase in SPOs. The increasing needs of already listed companies for capital to continue expanding partly explain this increase in SPOs. In addition, listed companies in these markets regularly acquire smaller non-listed companies, and these acquisitions may be financed through SPOs.

1.5. Changes in the corporate ownership and investor landscape

Today’s equity markets are characterised by the prevalence of concentrated ownership in listed companies and a wide variety of ownership structures across countries. Historically, however, most of the corporate governance debate has focused on situations with dispersed ownership, where the challenge of aligning the interests of shareholders and managers dominates. Recent developments have shifted ownership structures of listed companies towards concentrated ownership models. The first factor contributing to this is the increasing importance of Asian companies in stock markets. Since Asian companies often have a controlling shareholder – either a corporation, family or the state – their growing presence in capital markets has increased the prevalence of controlled companies. The second factor impacting concentration at the company level is the rise of institutional investors. While assets under management by institutional investors have increased during the last two decades, many companies in advanced economies have left public equity markets. Therefore, a growing amount of funds flowing into a decreasing number of companies has increased ownership concentration at the company level. The third factor has been the partial privatisation of many state‑owned companies through stock market listings since the 1990s. In many cases, privatisation through stock market listings has not led to any change in control and today states have controlling stakes in a large number of listed companies, particularly in emerging Asian markets.

This section provides a global overview of the ownership of listed companies, both in terms of the different categories of investors and the degree of ownership concentration at the company level. Table 1.1 provides characteristics related to these categories of shareholders and the extent of ownership concentration across companies that issue equity on the regulated or main markets in the 49 jurisdictions covered by the Factbook.

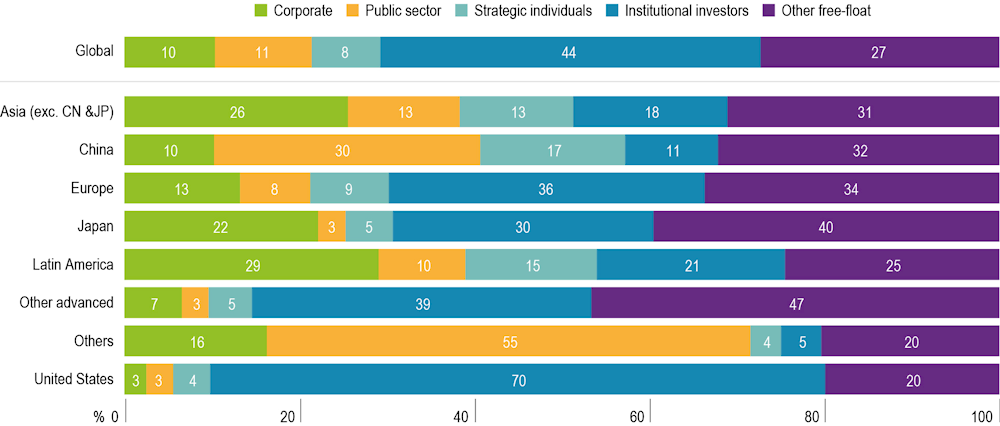

The findings presented in Figure 1.5 build on firm-level ownership information from almost 31 000 listed companies from 100 different markets. Together, these companies represent 98% of global stock market capitalisation. Using ownership information for each company, investors were classified into five categories following (De La Cruz, Medina and Tang, 2019[3]): private corporations, public sector, strategic individuals, institutional investors and other free‑float. Figure 1.5 shows the distribution of shareholdings among these five different investor categories at the global and regional levels. At the global level, institutional investors are the largest investors and own 44% of global market capitalisation, followed by the public sector with 11%, private corporations with 10%, and strategic individuals with 8%. The remaining 27% free‑float is owned by shareholders who do not reach the threshold for mandatory disclosure of their shareholdings and by retail investors who are not required to disclose their shareholdings.

Figure 1.5. Investors’ public equity holdings, end 2022

Note: The figure shows the overall ownership share by market capitalisation of the categories of owners for 31 000 listed companies from 100 different economies for which there is firm-level ownership information. See the Methodology for Ownership data in Annex 1.A for more detailed information.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

Figure 1.5 also shows how the importance of the different investor categories varies across markets. Institutional investors are by far the most dominant shareholders in the United States, where they own at least 70% of equity, with some of the unreported free‑float also likely to be owned by them. Institutional investors are also the largest investors in Europe, Japan and other advanced markets. In China, institutional investors are the smallest investors, owning around 11% of market capitalisation, and the public sector is the largest investor, owning almost 30% of all equity. The public sector is also a significant owner in Asia (excluding China and Japan) with a 13% ownership. Corporations are important owners in some regions. This is the case in Latin America and Asia (excluding China and Japan) where corporations own 29% and 26% of market capitalisation respectively, and in Japan where they own 22%. These figures suggest that private corporations and holding companies are important owners in listed companies, and in many cases also the presence of group structures.

1.6. The prevalence of concentrated ownership

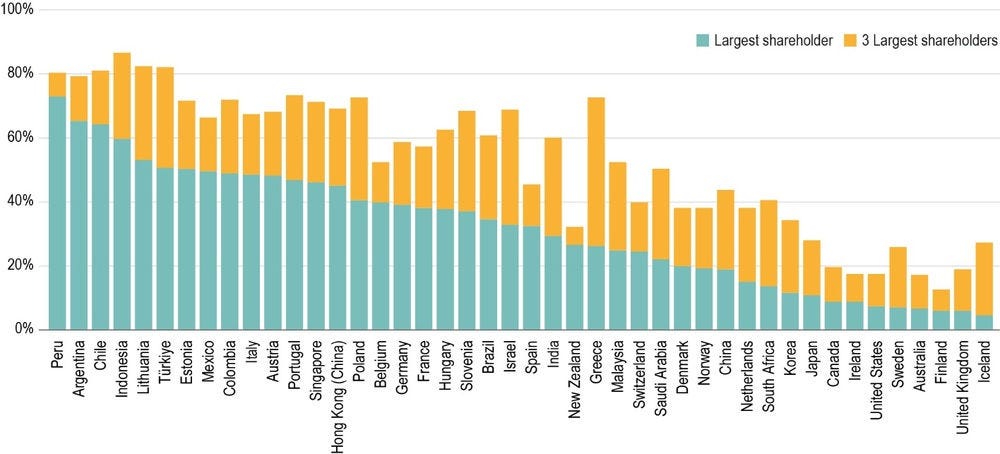

The degree of ownership concentration in an individual company is not only important for the relationship between owners and managers, it may also require additional focus on the relationship between controlling owners and non-controlling owners. The ownership structure in most markets today is characterised by a high degree of concentration at the company level. Figure 1.6 shows the share of companies in each jurisdiction where the single largest shareholder and the three largest shareholders own more than 50% of the company’s equity capital. In half of the markets, at least one‑third of all listed companies have a single owner holding more than 50% of the equity capital. In Peru, Argentina, Chile and Indonesia, more than 60% of companies have a single shareholder holding more than half of the equity capital.

Figure 1.6. Ownership concentration by market, end 2022

Note: The figure presents the share of companies where the largest and three largest shareholder(s) hold more than 50% of the equity as share of the total number of listed companies in each market across 44 out of the 49 Factbook jurisdictions. Factbook jurisdictions with less than ten companies with ownership information are excluded from the figure: Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Latvia, Luxembourg and the Slovak Republic. See the Methodology for Ownership data in Annex 1.A for more detailed information.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

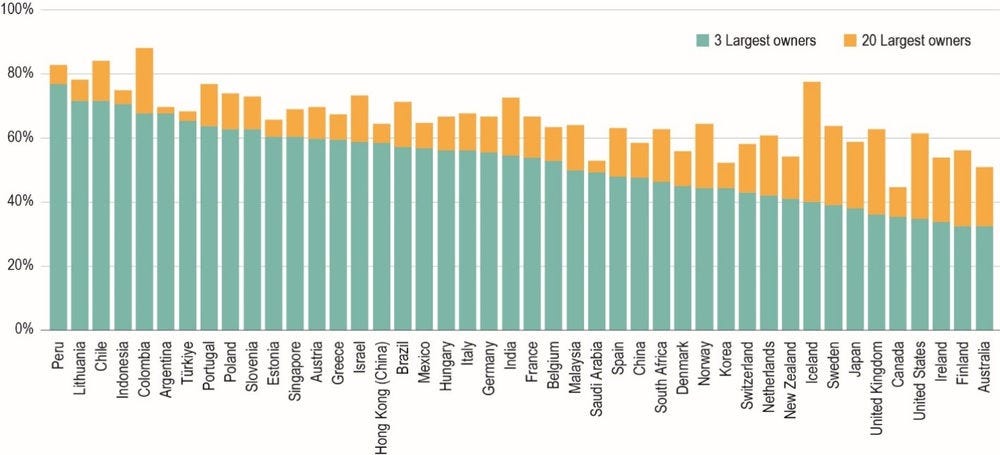

Figure 1.7 provides a closer look at ownership concentration at the company level in each market by showing the average combined holdings of the three largest and 20 largest shareholders. In 25 of 44 jurisdictions, the three largest shareholders own on average more than 50% of the company’s equity capital. The markets with the lowest ownership concentration, measured as the combined holdings of the three largest shareholders, are Australia, Finland, Ireland, the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, where the three largest shareholders still own a significant average combined holding, ranging between 33% and 36% of the company’s equity capital. Moreover, in all these jurisdictions, the 20 largest shareholders own on average between 45% and 63% of the company’s capital.

Figure 1.7. Ownership concentration at the company level, end 2022

Note: The figure shows ownership concentration at the company level for each market. It shows the average combined holdings of the three and 20 largest owners respectively across 44 out of the 49 jurisdictions covered by the Factbook. Factbook jurisdictions with less than ten companies with ownership information are excluded from the figure: Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Latvia, Luxembourg and the Slovak Republic. See the Methodology for Ownership data in Annex 1.A for more detailed information.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

Table 1.1 provides a comparison of ownership concentration across the Factbook’s 49 jurisdictions based on the percentage of companies where the three largest shareholders own at least 50% of the shares. In 39 of the jurisdictions, the three largest owners hold more than 50% of the equity capital in at least one‑third of all listed companies.

1.7. Trends in corporate bond financing

While the means and processes differ from those of shareholders, bondholders play an important role in defining the boundaries of corporate actions and in monitoring corporate performance. This is particularly salient in times of financial distress. Like equity, bonds typically provide longer-term financing than traditional bank loans and serve as a useful source of capital for companies seeking to diversify their capital base.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, corporate bonds have become both an important source of financing for non-financial corporations and an important asset class for investors. The low cost of debt resulting from sustained periods of expansive monetary policy has incentivised more, and riskier, issuers to borrow, using both corporate bonds and other instruments. In 2020, at the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, non‑financial companies rushed to tap corporate bond markets, issuing a record USD 3.3 trillion. In 2021, total issuance declined to USD 2.7 trillion, and in 2022, a tighter monetary policy environment increased the cost of debt, causing issuance to fall by more than a third to a total of USD 1.7 trillion.

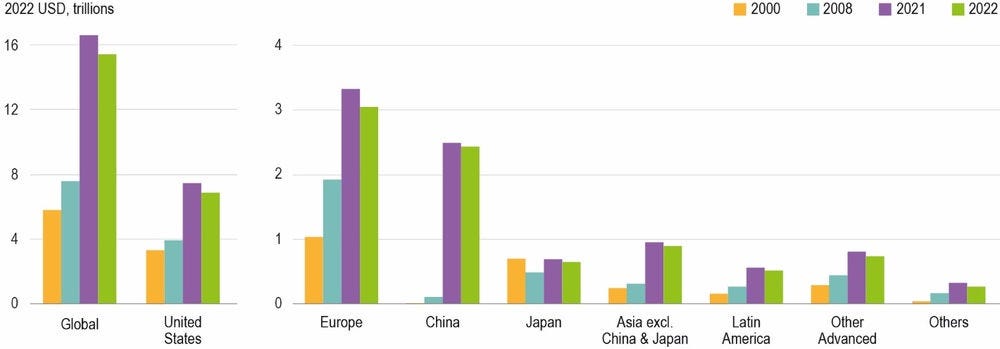

Annual corporate bond issuance almost doubled from an average of USD 1.2 trillion during the 2001‑11 period to USD 2.3 trillion during the 2012‑22 period (Figure 1.8). In many countries, the increasing use of corporate bonds has been supported by regulatory initiatives aimed at stimulating their use as a viable source of long-term funding for non‑financial companies. Except in the case of Japan, the figure shows that amounts issued have consistently increased since 1990. Importantly, while corporate bond issuances in China were negligible in the 1990s, since 2012 they have grown significantly. A similar trend has been observed in Asia (excluding China and Japan) where non-financial corporate bond issuances were 40 times higher during the 2012‑22 period compared to the 1990‑2000 period. In Europe, issuances since 2012 have almost quadrupled from the amount issued between 1990 and 2000. In the United States, corporate bond issuances by non-financial corporations almost tripled during the 2012‑22 period compared to the 1990s.

An important characteristic of global bond markets is the dominance of US corporate bond issuers. US companies are the largest users of corporate bonds, accounting for 40% of total issuances between 2012 and 2022. Over the same period, Chinese and European corporate bond issuances accounted for 21% and 19% of global issuances respectively.

This surge in the use of corporate bond financing has further highlighted the role of corporate bonds in corporate governance. For example, covenants, which are clauses in a bond contract that are designed to protect bondholders against actions that issuers can take at their expense, may have a strong influence on the governance of issuer companies. Covenants may range from specifying the conditions for dividend payments to clauses that require issuers to meet certain disclosure requirements.

One important feature of global corporate bond markets has been the decline in credit quality since 1990. Each year since 2010, with the exception of 2018 and 2022, more than 20% of the total amount of all bond issues was non-investment grade. In 2021, 35% of all non-financial corporate bond issuances was non‑investment grade. As a result of the tightening financing conditions in 2022, the share of non‑investment grade bonds dropped to 14% of all bond issuances. Importantly, over the last four years, the share of BBB rated bonds – the lowest investment grade rating – on average accounted for 54% of all investment grade issuance, higher than in previous years.

Figure 1.8. New issuance of non-financial corporate bonds

Note: See the Methodology for Corporate bond data in Annex 1.A for more detailed information.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, Refinitiv.

The global outstanding amount of non-financial corporate bonds reached a record level in 2021, amounting to USD 16.6 trillion in real terms, more than twice the 2008 amount. A similar pattern was observed in all regions. The outstanding amount of non-financial corporate bonds dropped to USD 15.4 trillion in 2022 as a result of the contraction in new issuances that year. Almost 45% of the outstanding amount of non-financial corporate bonds corresponds to US bonds, followed by European and Chinese bonds representing 20% and 16% of the total outstanding amount respectively. The outstanding amount of bonds issued by non-financial companies in Asia (excluding China and Japan) represented 6% of the total outstanding amount. Other regions’ outstanding amounts represented less than 5% of the total in 2022 (Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9. Outstanding amount of non-financial corporate bonds

Note: See the Methodology for Corporate bond data in Annex 1.A for more detailed information.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, Refinitiv.

1.8. Corporate sustainability

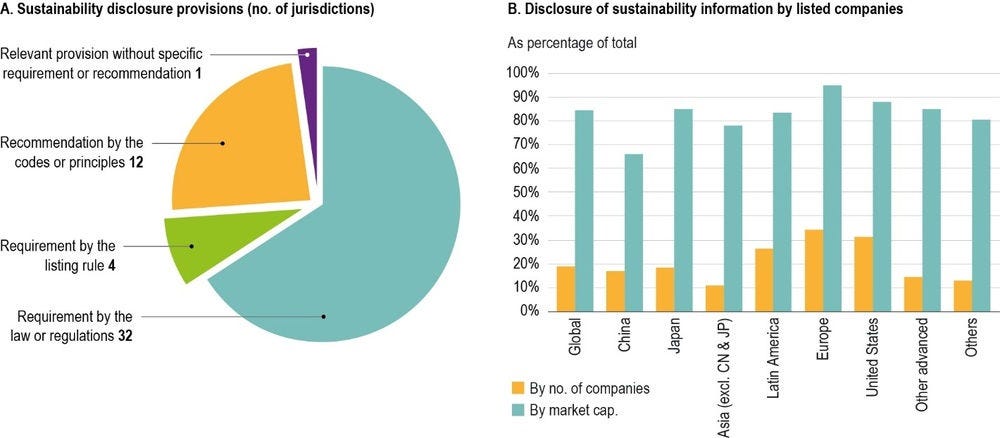

All Factbook jurisdictions have established relevant provisions, specific requirements or recommendations with respect to sustainability‑related disclosure that apply to at least large listed companies.

The corporate sector plays a central role in advancing the transition to a sustainable, low-carbon economy. In fact, climate change is a financially material risk for listed companies representing two‑thirds of global market capitalisation. Human capital, human rights and community relations, water and wastewater management and supply chain management, among other sustainability matters, are also critical risks for many listed companies (OECD, 2022[4]). This is why the revised G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance issued in 2023 include a new chapter on corporate sustainability and resilience, and why the Factbook also includes a new section on corporate sustainability issues (OECD, 2023[5]). The new chapter in the Principles presents a range of recommendations on corporate disclosure, the dialogue between a company and its shareholders and stakeholders on sustainability-related matters, and the role of the board in addressing these matters.

The Principles recognise sustainability‑related disclosure as essential to ensure the efficiency of capital markets and to allow shareholders to exercise their rights on an informed basis. All the jurisdictions surveyed have established relevant provisions, specific requirements or recommendations with respect to sustainability‑related disclosure. A requirement in the law or regulations has been established in nearly two‑thirds of the jurisdictions, while a requirement in listing rules has been established in 8% of the jurisdictions (Figure 1.10). In 24% of the jurisdictions, sustainability‑related disclosure is a recommendation provided by codes or principles, including frameworks set by the regulator or stock exchange following a “comply or explain” approach. In terms of the applicability of such relevant provisions, specific requirements or recommendations, sustainability information must or is recommended to be disclosed only by listed companies in 25 jurisdictions, while in the other 24 jurisdictions such disclosure framework covers both listed and non‑listed companies.

In the European Union, the 2014 Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) has been the main source for member countries’ sustainability‑related disclosure requirements. The NFRD requires listed companies, as well as non-listed companies that are public interest entities above certain thresholds, to disclose sustainability information. However, companies may choose the disclosure standard they prefer to use. The 2022 Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will generate some important changes in EU member countries’ regulatory frameworks. One of the most relevant changes introduced by the CSRD is that companies subject to the new Directive will have to disclose sustainability‑related information according to the EU Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which are being developed by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG).

As a result of existing sustainability‑related disclosure provisions, along with the growing consideration investors are devoting to sustainability‑related information, almost 8 000 companies listed in 73 markets globally disclosed sustainability information in 2021. These companies represent 84% of global market capitalisation, ranging from 66% in China where sustainability‑related disclosure is only recommended to 95% in Europe (Figure 1.10, Panel B). Notwithstanding, these companies represent only 19% of all listed companies globally, ranging from 17% in China to 34% in Europe (Figure 1.10, Panel B). This difference between the market capitalisation and number of companies ratios may be partially explained by the fact that 30 of the jurisdictions allow smaller listed companies not to disclose sustainability‑related information (Table 1.3). Moreover, in the 12 jurisdictions that only recommend the disclosure of sustainability‑related information, large listed companies may be more responsive to institutional investor demand for such information.

Figure 1.10. Sustainability‑related disclosure with 2021 information

Note: Panel A is based on 49 jurisdictions. The “as percentage of total by no. of companies and by market cap” in Panel B includes all listed companies in each region. For instance, out of 42 019 listed companies worldwide with a total market capitalisation of USD 122 trillion in December 2021, 7 926 listed companies totalling USD 103 trillion of market capitalisation disclosed sustainability-related information. See the Methodology for Corporate sustainability data in Annex 1.A for more detailed information.

Source: Table 1.3; OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

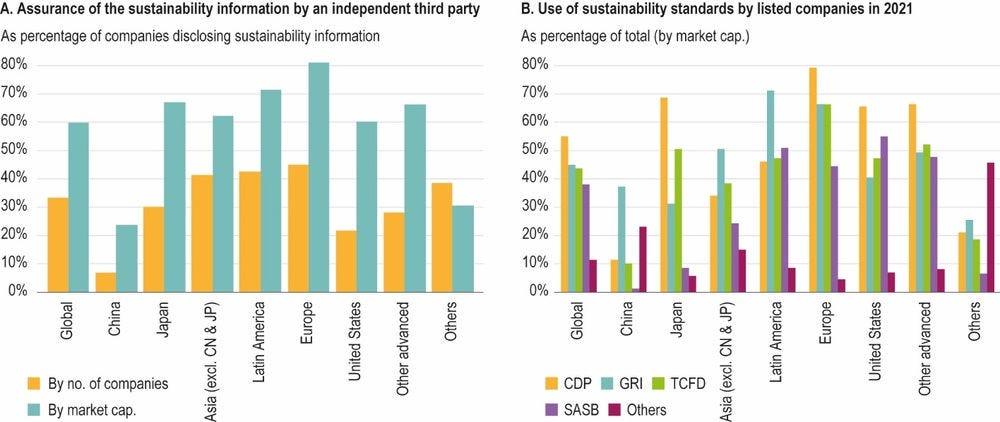

Investors’ confidence in sustainability-related information may be strengthened when the information is reviewed by an independent third party. This is why the Principles recommend that the “phasing in of requirements should be considered for annual assurance attestations by an independent, competent and qualified attestation service provider.” In 2022, almost 2 700 companies that account for 60% of those that disclosed sustainability‑related information by market capitalisation globally, hired an independent third party for the assurance of 2021 sustainability‑related information (Figure 1.11, Panel A). Europe has the highest share of companies providing assurance of sustainability‑related information, where 81% of the companies that disclosed sustainability‑related information by market capitalisation, hired an independent third party.

The consistency, comparability, and reliability of sustainability‑related information can also be reinforced if it follows “high quality, understandable, enforceable and internationally recognised standards”, as recommended by the Principles. Of the 49 jurisdictions surveyed, six (Australia, Canada, Colombia, Japan, Singapore, and the United Kingdom) require or recommend the use of an international disclosure standard, while another 11 require or recommend a local one (Table 1.3). The remaining 32 jurisdictions allow companies to disclose their sustainability‑related information according to the reporting framework of their choice.

Currently, listed companies often disclose a full (or partial) alignment with one or more international reporting standards. Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards, Task Force on Climate‑Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) recommendations or SASB standards were used in their 2021 sustainability‑related disclosure by companies representing an average of 42% of global market capitalisation (Figure 1.11, Panel B). The CDP questionnaires, formerly known as Climate Disclosure Project, were used by listed companies representing 55% of market capitalisation globally. Regional variations in the use of standards are noteworthy. For instance, TCFD recommendations were prominent in most regions except in China and Others, and SASB standards were used less in China, Japan, and Others.

Figure 1.11. Assurance of the sustainability information and use of sustainability standards

Note: In Panel A, the “as percentage of companies disclosing sustainability information by no. of companies and by market cap.” includes all companies that disclosed sustainability information in each region. In Panel B, the “as percentage of total by market cap.” includes all listed companies in each region. The sustainability disclosure can be either partially or fully compliant with a reporting standard (“Yes” refers both to full and partial compliance). The category “Others” for sustainability standards contains all companies that disclosed sustainability information (see Figure 1.10, Panel A) but that did not report compliance with any specific reporting standard among the four highlighted in the figure. While the CDP questionnaires would not typically be considered a sustainability-related disclosure standard, they are included in the analysis in Panel B because the questionnaires are an important framework for a majority of listed companies by market capitalisation globally.

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

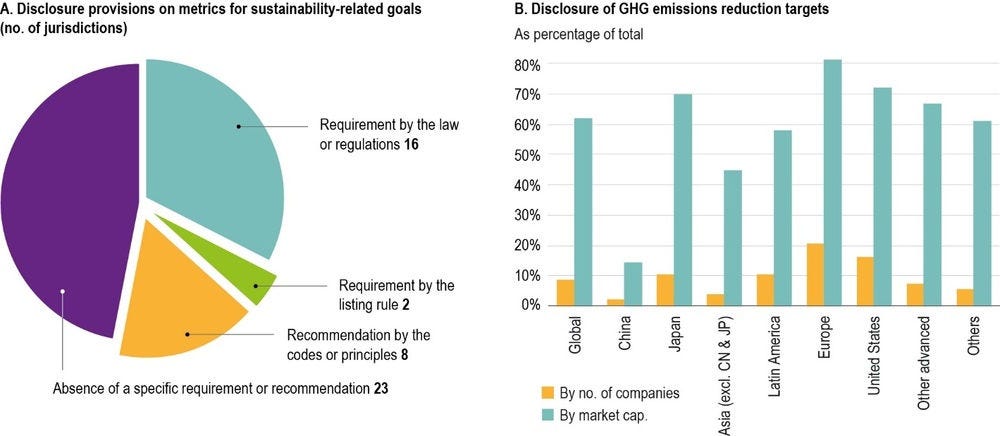

In addition to recommending the disclosure of all sustainability-related material information, the Principles add the specific recommendation that, “if a company publicly sets a sustainability‑related goal or target, the disclosure framework should provide that reliable metrics are regularly disclosed in an easily accessible form.” This is important to allow investors to assess the credibility of, and progress towards meeting an announced goal or target. Fifty-three percent of the jurisdictions surveyed already require or recommend the disclosure of metrics for sustainability‑related goals. In 16 jurisdictions, a requirement has been established in the law or regulation, while in two of them the requirement has been established in the listing rules. In eight jurisdictions, the disclosure of such metrics is recommended in codes or principles (Figure 1.12, Panel A).

One of the most relevant sustainability‑related metrics for many companies is greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions. More than 5 000 listed companies representing 72% of global market capitalisation publicly disclosed their 2021 GHG emissions resulting directly from their activities and indirect emissions related to their energy consumption (known as scope 1 and scope 2 GHG emissions respectively), and 3 300 companies (56% of market capitalisation) disclosed the emissions generated in their supply chains, (known as scope 3 GHG emissions) (OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, Refinitiv, Bloomberg). Companies are complementing these performance measurements with the disclosure of GHG emissions reduction targets. With the exception of companies listed in China, companies representing at least 40% of market capitalisation in the other selected regions disclose GHG emissions reduction targets, with higher shares in Europe, the United States and Japan (Figure 1.12, Panel B).

Figure 1.12. Metrics for sustainability‑related goals and GHG emissions reduction targets

Note: Panel A is based on 49 jurisdictions. The “as percentage of total by no. of companies and by market cap.” in Panel B includes all listed companies in each region. Information in Panel B includes companies that set targets or objectives to be achieved on emissions reduction – in scope are the short-term or long-term reduction targets to be achieved on emissions to land, air or water from businesses operations.

Source: Table 1.3; OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

The Principles recommend that “the corporate governance framework should ensure that boards adequately consider material sustainability risks and opportunities when fulfilling their key functions”. In half of the jurisdictions surveyed, boards are explicitly required or recommended to approve policies on sustainability‑related matters such as sustainability plans and targets, as well as internal control policies and management of sustainability risks. This is a legal or regulatory requirement in eight countries (Belgium, France, Greece, Hungary, Indonesia, Poland, Portugal, and Switzerland); a listing rules requirement in three jurisdictions (Hong Kong (China); Singapore; and South Africa); and a recommendation in 14 jurisdictions (Table 1.4). In the other half of the jurisdictions, there are no explicit requirements on board responsibilities for sustainability‑related policies but, depending on the materiality of the sustainability matter for the company, broad directors’ duties may apply. This is the case in Australia and Norway, for example.

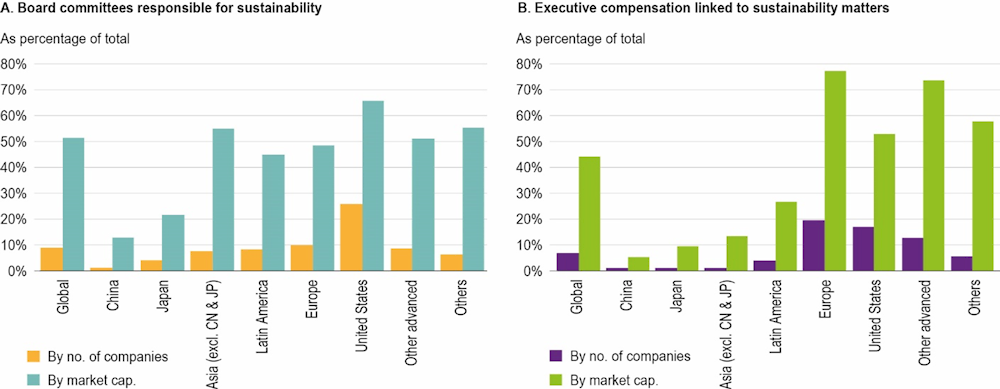

Boards may establish a new committee or expand the role of an existing one to support the board’s role in monitoring and guiding sustainability‑related governance practices, disclosure, strategy, risk management and internal control systems. Globally, companies representing half of total market capitalisation have a board committee responsible for sustainability, regardless of the specific name attributed to such committee (Figure 1.13, Panel A). The share of companies that have such a committee is above the global average in the United States (65% of market capitalisation), Others (55%) and Asia excl. China and Japan (54%), while it is less common in Japan (21%) and China (13%).

Boards may also use sustainability‑related metrics when determining executive remuneration or nomination policies. In Europe and Other advanced, over 70% of companies by market capitalisation link their executive compensation to sustainability matters, and in the United States and Others, between 50% and 60% do so. In the other regions, these shares range from 5% in China to 27% in Latin America (Figure 1.13, Panel B).

Figure 1.13. Board committees and executive compensation

Note: The “as percentage of total by no. of companies and by market cap.” includes all listed companies in each region. In Panel A, a company is considered to have such a committee if its responsibilities explicitly include oversight of CSR, sustainability, health and safety, and energy efficiency activities, regardless of the name of the committee. For example, a company with a “risk management committee” would be included in the category “Yes” if mentioned committee is responsible for managing sustainability risks. In Panel B, the compensation policy includes remuneration for the CEO, executive directors, non-board executives, and other management bodies based on “ESG or sustainability factors”.

Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, Refinitiv, Bloomberg.

The Principles recommend that corporate governance frameworks require ESG rating and data providers, as well as index providers, where regulated, to disclose and minimise conflicts of interest that might compromise the integrity of their analysis and advice. The Principles also state that the methodologies used by ESG rating and index providers should be transparent and publicly available. In Europe, the administration of indices used as benchmarks is subject to EU Regulation 2016/1011 (EU Benchmarks Regulation), which includes rules on governance, conflicts of interest, and benchmark transparency to users. Index providers must be authorised or registered by their competent national authority to ensure that the indexes they provide can be used in the European Union, but requirements vary depending on the importance of the benchmark concerned. The EU Benchmarks Regulation applies to different types of indices (i.e. not only to ESG index providers), but an amendment implemented by EU Regulation 2019/2089 introduced new rules applicable specifically to “EU Climate Transition Benchmarks” and “EU Paris-aligned Benchmarks index providers”.

Outside the European Union, index providers – including ESG index providers – are only regulated in China and in the United Kingdom among the Factbook jurisdictions (Table 1.4). Policies for the management of conflicts of interest and their disclosure for ESG rating providers are not widespread across the legal frameworks of the Factbook jurisdictions and are still a developing practice.

Table 1.1. Regulated markets and their ownership characteristics, 2022

|

Jurisdiction |

Regulated market size |

Ownership coverage |

Ownership by investor category (%)* |

Ownership concentration |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total market capitalisation [USD-Million] |

No. of listed companies |

Total market capitalisation (%) |

No. of listed companies |

IIs |

PS |

SI |

PC |

OFF |

(% of companies where 3 largest shareholders own >50%) |

|

|

Argentina |

46 079 |

82 |

94 |

43 |

6 |

22 |

18 |

23 |

30 |

79 |

|

Australia |

1 671 163 |

1976 |

98 |

1223 |

29 |

2 |

5 |

4 |

59 |

17 |

|

Austria |

117 118 |

53 |

100 |

50 |

24 |

23 |

6 |

19 |

28 |

68 |

|

Belgium |

318 084 |

103 |

99 |

88 |

38 |

3 |

7 |

24 |

29 |

52 |

|

Brazil |

786 762 |

355 |

100 |

326 |

29 |

14 |

8 |

24 |

25 |

61 |

|

Canada |

2 199 632 |

1419 |

99 |

982 |

47 |

4 |

4 |

7 |

39 |

20 |

|

Chile |

164 093 |

177 |

99 |

125 |

12 |

1 |

14 |

54 |

18 |

81 |

|

China |

12 157 764 |

4911 |

97 |

4421 |

11 |

30 |

17 |

10 |

32 |

43 |

|

Colombia |

68 636 |

59 |

99 |

39 |

13 |

36 |

9 |

32 |

10 |

72 |

|

Costa Rica |

1 984 |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Czech Republic |

28 344 |

11 |

100 |

10 |

9 |

46 |

4 |

16 |

25 |

100 |

|

Denmark |

608 540 |

121 |

100 |

111 |

34 |

6 |

2 |

22 |

36 |

38 |

|

Estonia |

4 731 |

20 |

99 |

14 |

7 |

30 |

13 |

19 |

31 |

71 |

|

Finland |

298 742 |

129 |

100 |

119 |

35 |

15 |

7 |

5 |

38 |

13 |

|

France |

2 833 497 |

355 |

100 |

325 |

28 |

7 |

17 |

15 |

33 |

57 |

|

Germany |

1 993 321 |

804 |

100 |

514 |

27 |

9 |

9 |

19 |

36 |

59 |

|

Greece |

57 096 |

137 |

96 |

65 |

17 |

11 |

14 |

24 |

35 |

72 |

|

Hong Kong (China) |

3 364 087 |

2411 |

98 |

1632 |

18 |

12 |

18 |

20 |

32 |

69 |

|

Hungary |

20 908 |

40 |

99 |

24 |

32 |

3 |

4 |

21 |

40 |

63 |

|

Iceland |

14 306 |

22 |

100 |

22 |

45 |

7 |

6 |

16 |

25 |

27 |

|

India |

3 407 859 |

4960 |

99 |

1539 |

21 |

15 |

12 |

32 |

20 |

60 |

|

Indonesia |

607 597 |

823 |

97 |

551 |

8 |

16 |

13 |

39 |

23 |

87 |

|

Ireland |

81 332 |

24 |

100 |

23 |

49 |

11 |

3 |

4 |

33 |

17 |

|

Israel |

230 155 |

493 |

100 |

464 |

33 |

1 |

20 |

20 |

26 |

69 |

|

Italy |

653 102 |

214 |

100 |

207 |

31 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

36 |

67 |

|

Japan |

5 366 978 |

3904 |

100 |

3877 |

30 |

3 |

5 |

22 |

40 |

28 |

|

Korea |

1 639 621 |

2331 |

99 |

2102 |

15 |

9 |

10 |

29 |

37 |

34 |

|

Latvia |

490 |

11 |

77 |

4 |

18 |

32 |

6 |

36 |

8 |

75 |

|

Lithuania |

5 069 |

25 |

97 |

17 |

3 |

38 |

12 |

29 |

18 |

82 |

|

Luxembourg |

16 381 |

9 |

100 |

8 |

22 |

4 |

6 |

41 |

28 |

75 |

|

Malaysia |

378 383 |

967 |

98 |

597 |

9 |

34 |

9 |

26 |

23 |

52 |

|

Mexico |

465 048 |

143 |

98 |

115 |

18 |

1 |

29 |

22 |

30 |

66 |

|

Netherlands |

899 804 |

98 |

100 |

87 |

38 |

3 |

7 |

22 |

31 |

38 |

|

New Zealand |

96 421 |

121 |

96 |

87 |

18 |

17 |

5 |

8 |

52 |

32 |

|

Norway |

390 707 |

208 |

100 |

205 |

28 |

34 |

7 |

12 |

19 |

38 |

|

Peru |

70 911 |

112 |

97 |

55 |

4 |

9 |

5 |

72 |

10 |

80 |

|

Poland |

145 676 |

390 |

99 |

255 |

28 |

16 |

13 |

20 |

23 |

73 |

|

Portugal |

83 347 |

37 |

100 |

30 |

22 |

11 |

14 |

32 |

21 |

73 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

2 626 679 |

250 |

93 |

168 |

1 |

84 |

2 |

3 |

10 |

50 |

|

Singapore |

434 049 |

570 |

99 |

290 |

15 |

15 |

11 |

20 |

39 |

71 |

|

Slovak Republic |

3 203 |

36 |

68 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

83 |

13 |

100 |

|

Slovenia |

8 708 |

34 |

95 |

19 |

8 |

33 |

1 |

13 |

45 |

68 |

|

South Africa |

392 542 |

216 |

100 |

176 |

24 |

14 |

3 |

23 |

36 |

40 |

|

Spain |

606 921 |

125 |

100 |

108 |

25 |

7 |

15 |

14 |

40 |

45 |

|

Sweden |

809 922 |

351 |

100 |

346 |

37 |

5 |

13 |

12 |

32 |

26 |

|

Switzerland |

1 834 619 |

240 |

100 |

224 |

31 |

6 |

7 |

7 |

49 |

40 |

|

Türkiye |

321 079 |

438 |

97 |

291 |

8 |

13 |

13 |

40 |

26 |

82 |

|

United Kingdom |

2 920 760 |

1334 |

100 |

1247 |

60 |

6 |

3 |

6 |

25 |

19 |

|

United States |

41 961 931 |

4812 |

100 |

4648 |

70 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

20 |

15 |

Key: Ownership by investor category: IIs: Institutional investors; PS: Public Sector; SI: Strategic Individual; PC: Private Corporation; OFF: Other free float.

Note: The number of listed companies on regulated markets is based on comparable figures excluding investment funds and real estate investment trusts (REITs) prepared as part of the OECD’s work on “Owners of the World’s Listed Companies” and updated with 2022 data. Companies that list more than one class of shares are considered as one company and only its primary listing is considered. Only companies listed on the regulated or main segments of the stock exchange are included here. See Methodology included in Annex 1.A for more information, as well as Box 1.1 for additional data related to alternative market segments.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, Refinitiv, Bloomberg; see De La Cruz, Medina and Tang (2019[3]) “Owners of the World’s Listed Companies”.

Table 1.2. The largest stock exchanges

|

Jurisdiction |

Largest stock exchange |

Group |

Legal status |

Self-listing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Argentina |

MerVal |

Bolsa y Mercados Argentinos (ByMA) |

- |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

Australia |

ASX |

Domestic (ASX Ltd) |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Austria |

|

CEESEG |

Private corporation or association |

No |

|

|

Belgium |

|

Euronext |

Joint stock company |

(Holding) |

|

|

Brazil |

B3 |

- |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Canada |

TMX |

TMX |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Chile |

|

- |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

China |

SSE |

- |

State‑controlled1 |

No |

|

|

SZSE |

- |

State‑controlled |

No |

||

|

BSE |

- |

State‑controlled |

No |

||

|

Colombia |

BVC |

BVC |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Costa Rica |

BNV |

- |

Private corporation or association |

No |

|

|

Czech Republic |

PSE |

Wiener Börse |

Joint stock company |

No |

|

|

Denmark |

|

NASDAQ Nordic LTD2 |

Private corporation or association |

(NASDAQ) |

|

|

Estonia |

TSE |

NASDAQ Nordic LTD2 |

Joint stock company |

(NASDAQ) |

|

|

Finland |

OMXH |

NASDAQ Nordic LTD2 |

Private corporation or association |

(NASDAQ) |

|

|

France |

- |

Euronext |

Joint stock company |

(Holding) |

|

|

Germany |

|

- |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Greece |

ATHEX |

- |

Joint stock company |

(HELEX) |

|

|

Hong Kong (China) |

SEHK |

- |

Private corporation or association |

Yes |

|

|

Hungary |

BSE |

- |

Joint stock company |

No |

|

|

Iceland |

|

NASDAQ Nordic LTD2 |

Private corporation or association |

(NASDAQ) |

|

|

India3 |

NSE |

- |

Joint stock company |

No |

|

|

BSE |

- |

Joint stock company |

No |

||

|

Indonesia |

IDX |

- |

Private corporation or association |

No |

|

|

Ireland |

ISE |

Euronext |

Joint stock company |

(Holding) |

|

|

Israel |

TASE |

- |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Italy |

|

Euronext |

Joint stock company |

(Holding) |

|

|

Japan |

TSE |

JPX |

Joint stock company |

(JPX) |

|

|

Korea |

KRX |

- |

Joint stock company |

No |

|

|

Latvia |

XRIS |

NASDAQ Nordic LTD2 |

Joint stock company |

(NASDAQ) |

|

|

Lithuania |

NASDAQ Nordic LTD2 |

Private corporation or association |

(NASDAQ) |

||

|

Luxembourg |

LSE |

- |

Private corporation or association |

No |

|

|

Malaysia |

KLSE |

- |

Private corporation |

Yes |

|

|

Mexico4 |

BMV |

Domestic |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Netherlands |

AMS |

Euronext |

Joint stock company |

(Holding) |

|

|

New Zealand |

NZX |

- |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Norway |

OSE |

Euronext |

Joint stock company |

No |

|

|

Peru |

BVL |

Domestic (Grupo BVL) |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Poland |

GPW |

GPW Group |

State‑controlled joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Portugal |

ELI |

Euronext |

Joint stock company |

(Holding) |

|

|

Saudi Arabia |

TASI |

Tadawul Group |

State‑controlled joint stock company |

No |

|

|

Singapore |

SGX |

- |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Slovak Republic |

BSSE |

- |

Joint stock company |

No |

|

|

Slovenia |

LJSE |

- |

Joint stock company |

No |

|

|

South Africa |

JSE |

JSE Limited |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Spain |

BME |

BME (Six Group Ltd) |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Sweden |

|

NASDAQ Nordic LTD2 |

Private corporation or association |

(NASDAQ) |

|

|

Switzerland |

SIX |

SIX Group Ltd |

Joint stock company |

No |

|

|

Türkiye |

BIST |

- |

State‑controlled joint stock company 5 |

No |

|

|

United Kingdom |

LSE |

LSEG |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

United States |

NYSE |

Intercontinental Exchange, Inc. |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

|

|

Nasdaq |

NASDAQ |

Joint stock company |

Yes |

||

Key: SOE = state‑owned enterprise, “-” = information not applicable or not available. ( ) = holding company listing.

1. In China, the law (Law of the People’s Republic of China on Securities, Art. 96) provides that a stock exchange is a legal person performing self-regulatory governance which provides the premises and facilities for centralised trading of securities, organises and supervises such securities trading and that the establishment and dissolution of a stock exchange shall be subject to decision by the State Council.

2. In seven jurisdictions (Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania and Sweden), the largest stock exchange is owned by NASDAQ Nordic Ltd (which is 100% owned by the NASDAQ Inc.).

3. In India, there are three nation-wide stock exchanges: NSE, BSE and Metropolitan Stock Exchange of India. Both NSE and BSE have been included in this table since NSE is largest in terms of volume of trading and BSE is largest in terms of number of entities listed on the stock exchange.

4. In Mexico, a second exchange, Bolsa Institucional de Valores (BIVA) started trading in July 2018.

5. In Türkiye, in line with the Council of Ministers Resolution No. 2017/9756 published in the Official Gazette dated 5 February 2017, the shares owned by the Treasury in Borsa Istanbul were transferred to the Turkish Wealth Fund Management, which is ultimately owned by the state.

Table 1.3. Sustainability‑related disclosure

|

Jurisdiction |

Key source(s) |

Sustainability disclosure |

Coverage of companies |

Disclosure standard2 |

Disclosure of metrics for sustainability-related goals |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Listed companies only/Listed and non‑listed companies |

Flexibility for listed smaller companies1 |

|||||

|

Argentina |

C |

Listed companies only |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

|

Australia |

ASIC Regulatory Guide 247: Effective Disclosure in an operating and financial review and ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations: 4th Edition |

C |

Listed companies only |

No |

TCFD |

C |

|

Austria |

L |

Listed and non‑listed companies |

Yes |

- |

C |

|

|

Belgium |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

L |

|

|

Brazil |

C4 |

Listed companies only |

No |

- |

- |

|

|

Canada5 |

Unofficial Consolidated Instruments 51-102 and 58-101 Canadian Securities Administrators Staff Notice 51-133, 51-358, CSA Staff Notice 51-354 |

L |

Listed companies |

Yes |

TCFD, SASB, CDP, GRI |

- |

|

Chile |

L |

Listed companies and other entities supervised by CMF |

No |

Local (based on GRI, TCFD, Integrated Reporting plus SASB metrics) |

L |

|

|

China |

C |

Listed and non‑listed companies7 |

Yes |

Local |

- |

|

|

Colombia |

L |

Listed companies only |

Yes |

TCFD+ SASB |

L |

|

|

Costa Rica |

Guidelines to disclose ESG information for issuing companies |

C |

Listed companies only |

No |

- |

C |

|

Czech Republic |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

|

Denmark |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

No |

- |

L8 |

|

|

Estonia |

L |

Listed companies, credit institutions and insurers that have over 500 employees |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

|

Finland |

Accounting Act (1336/1997), Chapter 3a on Statement of non-financial information |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

L |

|

France |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

Local |

L |

|

|

Germany |

German Commercial Code (Section 289b to 289e) |

L C |

Listed companies only |

Yes |

- |

L |

|

Greece |

Law 3556/2007, Law 4548/2018, |

L L C C |

Listed companies only |

Yes |

- |

L |

|

Hong Kong (China)9 |

Main Board: Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting Guide GEM Board: Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting Guide |

R |

Listed companies only |

No |

Local |

C |

|

Hungary |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

L |

|

|

Iceland |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

No |

- |

- |

|

|

India |

Circular on Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting (BRSR) by listed entities |

L |

Listed companies only10 |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

Indonesia |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

No |

- |

- |

|

|

Ireland |

Irish Stock Exchange Listing Rules applying UK Corporate Governance Code |

C |

Listed companies only |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

Israel |

C |

Listed companies only |

No |

- |

||

|

Italy |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

L |

|

|

Japan |

C |

Listed companies only |

No |

TCFD or equivalent |

- |

|

|

Korea |

C |

Listed companies only |

Yes |

Local |

- |

|

|

Latvia |

Financial instruments market law and Law on Governance of Capital Shares of a Public Person and Capital Companies |

L |

Listed companies and non-listed SOEs |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

Lithuania |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

|

Luxembourg |

The X Principles of Corporate Governance (X Principles) of the Luxembourg Stock. Exchange |

C |

Listed companies only |

No |

- |

- |

|

Malaysia |

Practice Note 9 of the Main Market Listing Requirements and Guidance Note 11 of the ACE Market Listing Requirements14 |

R |

Listed companies only |

No |

Local + TCFD |

R |

|

Mexico |

Circular of Issuers15 – Annex H and N |

L |

Listed companies only |

No |

- |

L |

|

Netherlands |

L C |

Listed companies only |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

|

New Zealand |

L R |

Listed and non-listed companies16 |

Yes |

Local (based on TCFD) |

L |

|

|

Norway |

L |

Listed companies, non-listed banks and non-listed companies defined as public companies according to national law |

No |

- |

- |

|

|

Peru |

Resolution 18/2020-SMV/02 on Corporate Sustainability Report |

L |

Listed companies only |

Yes |

Local |

L |

|

Poland |

EU sustainability-related reporting directives |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

Local (based on GRI, TCFD) |

L |

|

Portugal |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

L |

|

|

Saudi Arabia |

C |

Listed companies only |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

|

Singapore |

R |

Listed companies only |

No |

TCFD |

R |

|

|

Slovak Republic |

C |

Listed companies only |

- |

Local |

C |

|

|

Slovenia |

L C |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

|

South Africa |

R C |

Listed companies only |

No |

- |

C |

|

|

Spain |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

|

Sweden |

Public: The Annual Accounts Act |

L C |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

Switzerland |

L |

Listed and non-listed companies |

Yes |

- |

L |

|

|

Türkiye |

L |

Listed companies18 |

No |

Local |

C |

|

|

United Kingdom |

FCA’s Climate related Disclosure Regime: Listing rules LR 9.8.6R and LR 14.3.27 R |

R L |

Listed and non-listed companies19 |

No |

TCFD |

C |

|

United States |

- |

SEC-registered public companies |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

Key: L = requirement by the law or regulations; R = requirement by the listing rule; C and ( ) = recommendation by the codes or principles, including frameworks set by the regulator or stock exchange following a “comply or explain” approach; “-” = absence of a specific requirement or recommendation.

Note: The European Union’s 2022 Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will generate some important changes in EU member countries’ regulatory frameworks, and member countries need to adapt their sustainability‑related disclosure frameworks in compliance with the Directive by 6 July 2024. Some major member countries, including France and Germany, have not yet adapted their frameworks in line with the new Directive. One of the most relevant innovations brought by the CSRD is that companies subject to the new Directive will have to disclose sustainability‑related information according to the EU Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which are being developed by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG). The first set of ESRS were scheduled to be adopted by the European Commission by 30 June 2023. The application of the new Directive will take place in four stages: (i) reporting in 2025 for companies already subject to the NFRD; (ii) reporting in 2026 for large companies that are not currently subject to the NFRD; (iii) reporting in 2027 for listed small and medium enterprises; (iv) reporting in 2029 for third-country undertakings with net turnover above EUR 150 million in the European Union if they have at least one subsidiary or branch in the EU exceeding certain thresholds.

1. “Flexibility for listed smaller companies” refers to the existence of different requirements for listed companies according to their size, which may be assessed in different forms such as total assets or number of employees. Jurisdictions that have a phase‑in period for sustainability‑related disclosure requirements based on the companies’ size are not considered to have “flexibility” in this table if, at the end of the phase‑in period, all requirements apply equally to all listed companies. While the adoption of a “comply or explain” system does allow flexibility for smaller companies not to comply with a recommendation, the adoption of such a system is not considered to allow “flexibility” in this table if all listed companies – without exceptions to smaller companies – need to report on their compliance. Finally, while it is acknowledged that some regulatory frameworks adopt flexible requirements for smaller non-listed companies, only flexibility for listed companies is considered in the column “Flexibility for listed smaller companies”.

2. In “Disclosure standard”, jurisdictions that require or recommend companies to follow any disclosure standard, therefore providing flexibility for companies to choose the specific standard to be used, are indicated as “-” in the column.

3. In Argentina, the national corporate governance code briefly mentions the need for the company to disclose sustainability information on its website, as well as to provide relevant corporate social responsibility information to its shareholders. Further, companies must include in their annual reports information about their environmental or sustainability policies. Finally, public offering rules establish that prospectuses must include a description of the company’s environmental or sustainability policies and, if the company does not have such policies, it must provide an explanation why.

4. In Brazil, there is a recommendation for companies to disclose climate‑related risks according to TCFD’s recommendations, and companies need to explain in case they prefer to use another standard. In addition, disclosure on some particular sustainability issues, such as the workforce composition according to gender and race, is binding.

5. In Canada, Budget 2022 announced that the federal government is committed to moving towards mandatory reporting of climate‑related financial risks across a broad spectrum of the Canadian economy, based on the TCFD’s recommendations. In addition, Canada’s Securities Administrators (CSA) has issued three publications on climate‑related disclosures –CSA Staff Notice 51-333 in 2010, CSA Staff Notice 51‑354 in 2018, and CSA Staff Notice 51-358 in 2019. Said staff notices provide guidance to issuers on existing continuous disclosure requirements related to environmental climate‑related risks. Proposed National Instrument 51‑107, when in force, will require issuers to disclose certain climate‑related information in compliance with the recommendations of the TCFD. Finally, Part XIV.1 of the Canada Business Corporations Act includes disclosure requirements related to diversity.

6. In Chile, the Financial Market Commission (CMF) General Rule No. 30 was modified in 2021 to require corporate governance and sustainability disclosure in the annual report of the issuers of publicly offered securities and other entities supervised by the CMF such as banks, insurance companies, financial markets infrastructures and fund managers administrators, among others. Article 10 of the Securities Market Law was modified in 2022 to establish that entities registered in the Securities Registry carried by the CMF should provide information to the general public regarding their environmental and climate change impact, including the identification, evaluation and management of the related risks, as well as corresponding metrics. This provision is in addition to the establishment in Article 9 of an obligation of the issuers of publicly offered securities to disclose truthfully, sufficiently, and promptly all material information about their businesses.

7. In China, companies listed in the STAR Market on the Shanghai Stock Exchange and sample companies in the Shenzhen 100 Index, as well as some other companies, are required to disclose sustainability‑related information. In addition, all listed companies and Chinese state‑owned enterprises are encouraged to disclose sustainability‑related information. See also: Self-regulatory Guidelines for Listed Companies on the SSE (No. 1 - Regulation of Operations) and Beijing Stock Exchange listing rules.

8. In Denmark large companies are not required to have specific metrics with regard to sustainability goals, but the metrics used within the company have to be disclosed.

9. In Hong Kong (China), the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited published a consultation paper seeking market feedback on proposals to enhance climate‑related disclosures under the environmental, social and governance (ESG) framework in April 2023. It proposed that all issuers be mandated to make climate‑related disclosures in their ESG reports based on the provisions of the International Sustainability Standards Board Climate Standard in respect of financial years commencing on or after 1 January 2024. The consultation period ended in mid-July 2023 and the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited plans to publish its conclusions and final rules before the end of 2023.

10. In India, the sustainability‑related disclosure requirement applies to the top 1 000 listed entities by market capitalisation.

11. In Israel, listed companies are recommended to publish an annual Corporate Social Responsibility report to public investors and other stakeholders. The ISA recommends reporting corporations that elect to publish an annual CSR report to draft the report on the basis of generally accepted international standards such as GRI or SASB. Nonetheless, reporting corporations that elect to publish an annual CSR report may draft the report on the basis of other acceptable standards.

12. In Japan, all listed companies are recommended to develop a basic policy and disclose initiatives on the company’s sustainability. However, companies listed in the Prime Market should also enhance the quality and quantity of climate‑related disclosure based on TCFD recommendations or equivalent international frameworks. The relevant ordinances were revised in January 2023 to make specific disclosure of sustainability information in the Annual Securities Report mandatory, including the company’s responses to climate change and human capital, effective from the financial year ending in March 2023.

13. In Korea, KOSPI listed companies with total assets of more than KRW 1 trillion are required to disclose a corporate governance report no later than the last day of May. Coverage of companies will be gradually expanded as follows: KOSPI listed companies with total assets of 500 billion won (from 2024) and all KOSPI listed companies (from 2026). In the corporate governance report, companies should disclose whether they comply with key principles of the Korea Institute of Corporate Governance and Sustainability’s Code of Best Practices for Corporate Governance, which includes several sustainability‑related recommendations, and explain why if they do not comply. The KOSPI index includes the companies with the largest capitalisation in Korea.