OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Australia 2018

Chapter 6. Australia’s results, evaluation and learning

Management for development results

Peer review indicator: A results-based management system is being applied

Australia has a robust performance framework that is used for accountability and to drive coherence with Australia’s new development policy and targets. Going forward, DFAT has an opportunity to ensure that its results framework is fully aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals, reflects an appropriate level of ambition, and creates the right incentives for good programme design and management.

Australia has a comprehensive, well-managed performance and reporting architecture that is closely tied to high-level policy objectives

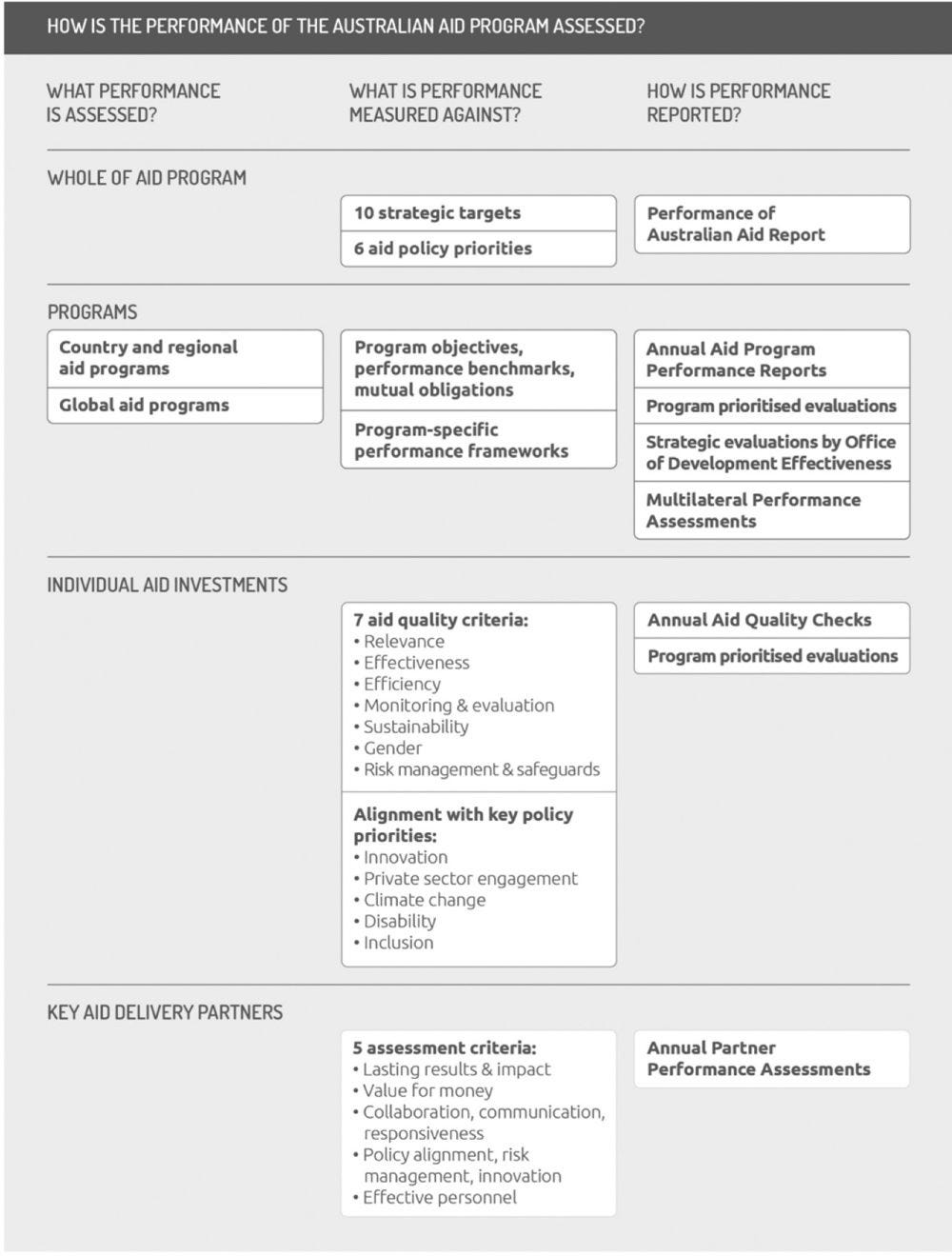

Australia has set out a clear and comprehensive performance framework to accompany its new aid policy and strategic targets. The framework continues the AusAID practice of publishing an annual review of headline-level aid performance. DFAT’s performance framework consists of a four-level reporting architecture to measure performance at the whole of aid, programme, individual investment and partner performance levels, with specific reporting products tied to each level (Figure 6.1).

Australia reports on progress against the ten strategic targets (Chapter 2) in its annual Performance of Australian Aid report using aggregated performance information. The annual report also includes regional programme performance and the performance of key partners and multilaterals. Assessments made in the annual report are meant to inform annual budget allocations.

In implementing the new performance framework, Australia has met the recommendation from the last review to reinforce its performance reporting at the strategic, programme and individual investment levels. The new framework places a heavy emphasis on ensuring that taxpayer dollars are well spent and demonstrate results. Overall, Australia’s aggregated performance reporting system is well oriented to ensure that performance information is used for overall direction, communications and accountability. However, there is less emphasis on the use of results for learning at the strategic level. The aggregate reporting captures progress and achievement against performance targets, but an enhanced focus on challenges and bottlenecks could further help orient strategic decision making.

Australia’s performance framework has a strong focus on using DFAT’s eight value for money principles (Chapter 2).1 The emphasis on accountability, if not properly managed, risks hindering learning from experimentation with riskier or more innovative programmes. Moreover, there is a focus on self-assessed performance information (based on measured outputs and internal metrics) rather than on the development impact of Australian aid in partner countries and how aid relates to achieving the 2030 Agenda. Australia has therefore not fully met the recommendation from the last peer review to “focus on learning from successes and challenges in its overall reporting on results” (OECD, 2013).

Australia uses performance reporting at different levels to manage programmes and inform funding decisions

DFAT has performance benchmarks and a number of reporting tools at the country, regional and programme level. All programmes with an annual total ODA allocation of AUD 50 million or more are required to have a performance assessment framework (PAF), which defines indicators to measure progress. Country and regional programmes are required to have Aid Investment Plans, which contain performance benchmarks selected from the PAF indicators. Assessments against objectives are reported in Aid Program Performance Reports (APPRs), which are peer reviewed and use a green‑amber‑red colour to indicate progress towards objectives. Where progress is below expectations, APPRs outline management actions to remedy the situation. The quality of these reports has been considered to be “largely adequate or good” (ODE 2016c). Annual Aid Quality Checks combine the available information from other reporting and monitoring into an annual report of progress. Collectively, these attest to a strong focus on performance and are examples of good practice.

All investment designs must contain a monitoring and evaluation framework. It is the responsibility of the DFAT staff managing the design process to ensure this occurs. Sector-specific resources are available to help them select indicators. Monitoring information generally consists of primary data, progress reports prepared by delivery partners and field visits. Impressively, DFAT’s monitoring and evaluation standards2 are regularly updated and provide detailed guidance to help staff improve the quality of performance reporting (DFAT, 2017c).

Poorly performing projects are subject to stiffer requirements and possible cancellation. This could incentivise programme managers to avoid riskier projects and avoid critical reporting, potentially introducing elements of bias into self-reported performance information. Overall, DFAT needs to reflect on how to manage these risks and assess the potential trade-offs. In particular, DFAT will need to ensure that it has the right systems and tools in place for overseeing and monitoring the performance of programmes that are managed by external consultants, as these represent a large proportion of DFAT’s portfolio. This is especially true in the case of DFAT’s private sector work and partnerships, which often are implemented by external consultants or managed through multilateral development banks (who also may design the projects). DFAT will need to ensure it creates strong feedback loops to internalise lessons and develops staff capacity to provide appropriate oversight (Chapter 4).

Australia, like many DAC members, could further align its performance and results reporting with the Sustainable Development Goals

Australia could continue to ensure that its results framework is fully aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The 2016 Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC) monitoring data find that only 38.6% of the objectives of Australia’s development interventions are drawn from the national development plan (OECD/UNDP 2016). This suggests there is room for further improvement. DFAT, like other donors, could consider how it can further align its results frameworks with country-level SDG reporting and follow-up processes. It could also consider how to further formalise its support of in-country capacity for SDG monitoring.

Figure 6.1. Australia’s performance framework

Source: DFAT (2017a), Aid Programming Guide, http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/aid-programming-guide.pdf.

Evaluation system

Peer review indicator: The evaluation system is in line with the DAC evaluation principles

Australia has a strong evaluation system and has continued support and funding for high-quality evaluation work. DFAT recently has made efforts to improve linkages between centralised and decentralised evaluations. Ensuring that all evaluations are published on line in a timely manner and are accompanied by required management responses would help further reinforce transparency, accountability and learning. Like many members, DFAT could enhance stakeholders’ involvement in evaluation.

Australia has maintained a strong, independent evaluation system that is well placed to address strategic issues and priorities

Australia’s commitment to conducting high-quality evaluations has been maintained following the integration of AusAID into DFAT, and evaluation policy remained relatively consistent during the transition period (OECD, 2016). In 2017, a new evaluation policy was put in place that outlines departmental roles and specifies the process for approving evaluation plans (ODE, 2017). A positive aspect is that the policy has an increased emphasis on evaluation use. The new evaluation policy also specifies the role of DFAT senior management in setting and approving evaluation plans, helping to ensure that evaluations are linked to strategic issues and decision-making processes at DFAT’s senior management level.

DFAT’s Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE) is the unit charged with conducting and managing centralised evaluations. ODE conducts its own strategic evaluations with a policy, programme, sectoral or thematic focus. It also supports and reviews programme evaluations, occasionally taking the lead in conducting these. The mandate for ODE was expanded following the integration to include a role in assuring the quality of the assessments made in DFAT’s annual Performance of Australian Aid report; the position of head of ODE also was made more senior (OECD, 2016). These shifts have helped ensure the quality and rigour of DFAT results reporting and improved the influence of evaluation findings within DFAT.

Staffing and funding for evaluations have remained consistent despite the overall cuts to the aid budget, showing a continued commitment to evaluation and accountability. ODE has 14 full-time equivalent staff and its own budget allocation. The budget for centralised evaluation in 2015/16 was AUD 1.7 million (USD 1.26 million), which was an estimated 0.04% of the development budget (OECD, 2016). The average cost of decentralised evaluations in 2014 was AUD 80 000 (USD 72 111), representing 0.37% of investment value (ODE, 2014a). This is consistent with funding and staffing for evaluation in other DAC member countries.

ODE is operationally independent and the head of ODE reports to a deputy secretary. The Independent Evaluation Committee provides quality control and acts as an external advisory body.3 Having an external advisory group for evaluation is not common in other Australian government departments, showing that DFAT has maintained the emphasis on independence and quality following the integration. This can serve as a positive model for other government departments. There are early indications that AusAID’s strong evaluation culture has influenced DFAT and the practice of evaluation within the Australian government more generally, which also is positive.

An annual evaluation plan is endorsed by the Independent Evaluation Committee, approved by the Secretary of DFAT and published on the evaluation website. The annual plan outlines both strategic evaluations by ODE and operational evaluations, with a focus on ensuring coherent linkages between the two. According to the 2016 evaluation policy, priority topics for ODE evaluations include areas where significant evidence gaps need to be filled, issues that pose a significant risk and interventions that are high priority for the Australian government (ODE, 2017).

Like many members, the ODE recently has been focused on encouraging fewer, better quality evaluations (OECD, 2016). It remains to be seen how ODE’s efforts to strengthen linkages with decentralised evaluations will impact their quality and use, but the inclusion of decentralised programme evaluations in the annual evaluation plan is a step in the right direction.

The quality of decentralised evaluations is variable and they are not always published in a timely manner

DFAT country, regional and thematic aid programmes are required to complete a number of (decentralised) evaluations that focus on the priority issues facing each programme. ODE provides evaluation tools, guidance documents, standards and examples of evaluation products and offers ad hoc courses and workshops for DFAT staff. To ensure the independence of evaluations, DFAT policy specifies that a person who is not directly involved in management of the programme being evaluated should lead the programme evaluation; however, inclusion of DFAT staff in evaluation teams also is encouraged to help build capacity (DFAT, 2017a).

DFAT has undertaken specific efforts to improve the quality and consistency of decentralised evaluations, and progress has been made. For instance, the most recent ODE meta-evaluation of operational evaluations found the majority of them to be credible, although it found some room for improvement in the area of evaluation design and management (OECD, 2016; ODE, 2016a). According to this review, only half of the operational evaluations had management responses, a finding that shows definite room for improvement in this area (ODE, 2016a). In addition, only 38% of completed operational evaluations were posted on line within one year, consistent with the low rate found in previous reviews (ODE, 2016a). DFAT has been working to improve its publishing of evaluations, including decentralised evaluations on line and has been making progress on this in recent months.

DFAT could do more to encourage country partner participation and to help build country partner evaluation capacity

The 2017 evaluation policy notes that “DFAT will engage with partner governments and implementing partners early in evaluations to ensure these partners have ownership of evaluation design and implementation” (ODE, 2017). However, in 2014, only 34% of operational evaluations were conducted jointly with a partner or led by a partner; this represented an increase from 17% in 2012 (ODE, 2014a). There are clear opportunities for Australia to further reinforce its efforts to support partner countries’ evaluation capacity in line with review and follow-up mechanisms for the 2030 Agenda. To build on existing practices at country level, DFAT could formalise this objective and provide guidance for country managers.

Institutional learning

Peer review indicator: Evaluations and appropriate knowledge management systems are used as management tools

Australia has a formalised management response system for evaluations and strives to use lessons in programming decisions. DFAT recently has made efforts to improve its knowledge management, but it has not yet dedicated sufficient resources. Funding for research has expanded and is closely linked with Australian aid priorities. Despite progress, DFAT has room to make further improvement to its knowledge management system to ensure that decentralised evaluations, research and learning are shared across the department.

DFAT makes efforts to learn from evaluations and has a robust system for follow-up of recommendations

In addition to publishing evaluation reports on line, DFAT often disseminates evaluation findings through newsletters, workshops, seminars, thematic communities of practice and lessons learned reports. ODE also holds recommendation workshops with key staff prior to finalising its reports and develops summaries of evaluations for policy makers with an aim of increasing use. The old Aid Investment Committee used to have the responsibility to ensure that evaluation findings are used to inform the aid strategies and investments it approves.

Since 2014, ODE has conducted an annual review of uptake of ODE recommendations to assess progress in implementing the recommendations in recent ODE evaluations. The review also assesses how evaluations may have influenced the aid programme and development polices, with the aim of learning lessons to improve the impact of future ODE evaluations. Encouragingly, the most recent review found that most recommendations are being implemented and documented a number of specific changes that were made as a result of recent evaluations (ODE, 2016b). DFAT’s follow up on evaluation recommendations and its formalised management response system for centralised evaluations are notable examples of good practice.

DFAT has made efforts to improve its knowledge management system, but has yet to commit sufficient resources to this objective

Following the integration of AusAID into DFAT, a staff Capability Action Plan was put in place that included the objective of improving knowledge management practices across the integrated department (Chapter 4). In March 2016, a knowledge management framework and associated roadmap for change were established. However, a number of the planned initiatives to improve knowledge management have not yet received sufficient resources to be fully implemented (DFAT, 2017g).

The Knowledge Management Unit (KMU), which currently is in the Development Policy Division, is responsible for media, publications and sharing insights. The unit organises outside guest speakers; hosts seminars, workshops and events; and leads pilot projects such as a recent pilot to embed insights from behavioural economics into the design and evaluation of programmes.

Research is generally considered to be of good quality, and is in line with aid priorities

DFAT’s budget for research has increased more than that of its programmable aid, demonstrating a strong commitment to research. The research budget rose to more than AUD 181 million (USD 174.6 million) in 2012/13 from AUD 19 million in 2005/06 (ODE, 2015a). Since 2005/06 about 3% of DFAT’s aid budget has been spent on research, a proportion that is in line with that of other DAC countries (ODE, 2015a). DFAT’s research is highly decentralised: country and thematic programmes directly manage 97% of it and Australian institutions and individuals receive around 60% of DFAT’s research budget (ODE 2015a). A 2015 ODE evaluation found that the budget for research has been appropriate, in line with aid priorities and generally is considered to be of good quality (ODE, 2015a). These views were echoed by various stakeholders in Canberra and Honiara.

Bibliography

Government sources

DFAT (2017a), Aid Programming Guide, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/aid-programming-guide.pdf.

DFAT (2017b), “Draft aid evaluation policy”, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/Documents/dfat-aid-evaluation-policy-nov-2016.pdf.

DFAT (2017c), Draft Monitoring and Evaluation Standards, DFAT, Canberra, https://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/monitoring-evaluation-standards.pdf.

DFAT (2017d), Performance of Australian Aid 2015-16, Canberra, Australia. http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/performance-of-australian-aid-2015-16.pdf

DFAT (2017e), “Research overview”, DFAT website, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/topics/development-issues/research/Pages/research.aspx (accessed 3 August 2017).

DFAT (2017f), “Independent Evaluation Committee”, ODE website, DFAT, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/aboutode/Pages/iec.aspx (accessed 17 September 2017).

DFAT (2017g), “OECD DAC Peer Review of Australia’s Aid Program: Memorandum of Australia”, Canberra (unpublished).

DFAT (2016), “Knowledge management framework”, (internal document).

DFAT (2015), “Australia’s new development policy and performance framework: A summary”, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/aid-policy-summary-doc.pdf.

DFAT (2015), Strategy for Australia’s Aid Investments in Private Sector Development, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Pages/strategy-for-australias-aid-investments-in-private-sector-development.aspx.

DFAT (2014), “Making performance count: Enhancing the accountability and effectiveness of Australian aid”, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Pages/making-performance-count-enhancing-the-accountability-and-effectiveness-of-australian-aid.aspx.

ODE (2017), “2017 annual evaluation plan”, Office of Development Effectiveness, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/Documents/ode-annual-aid-evaluation-plan-2017.pdf.

ODE (2016a), “Lessons from the review of operational evaluations brief”, ODE, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/Documents/ode-brief-lessons-from-op-evals-june-2016.pdf.

ODE (2016b), “2016 review of uptake of ODE recommendations”, ODE, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/other-work/Pages/review-of-uptake-of-ode-recommendations-2016.aspx.

ODE (2016c), 2015 Quality Review of Aid Program Performance Reports, ODE, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/Documents/2015-quality-review-apprs.PDF.

ODE (2016d), “Independent Evaluation Committee: Terms of Reference”, ODE, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/Documents/iec-terms-of-reference.pdf.

ODE (2015a), Research for Better Aid: An Evaluation of DFAT’s Investments, ODE, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/Documents/research-for-better-aid-an-evaluation-of-dfats-investments.pdf.

ODE (2015b), “2015 review of uptake of ODE recommendations”, ODE, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/other-work/Pages/review-of-uptake-of-ode-recommendations.aspx.

ODE (2015c), “2014 Quality Review of aid program performance reports”, ODE, DFAT, Canberra, https://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/Documents/2014-quality-review-apprs.pdf.

ODE (2014a), “Review of operational evaluations completed in 2014”, Part 1, Quality Review, ODE, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/other-work/Pages/review-of-operational-evaluations-completed-in-2014.aspx.

ODE (2014b), “Review of uptake of ODE recommendations”, ODE, DFAT, Canberra, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/how-we-measure-performance/ode/other-work/Pages/review-of-uptake-of-ode-recommendations-2014.aspx.

Other sources

OECD (2016), Evaluation Systems in Development Co-operation: 2016 Review, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264262065-en

OECD/UNDP (2016), Making Development Co-operation More Effective: 2016 Progress Report, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264266261-en.

OECD (2013), OECD Development Co-operation Peer Review: Australia 2013, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/OECD%20Australia%20FinalONLINE.pdf.

Research for Development Impact Network (2017), “Effective and ethical research and evaluation in international development”, website, https://rdinetwork.org.au/ (accessed 7 August 2017).

Zwart, R. (2017), “Strengthening the results chain: Synthesis of case studies of results-based management by providers”, OECD Development Policy Papers, No. 7, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/544032a1-en.

Notes

← 1. Partner Performance Assessments (PPAs) and Multilateral Performance Assessments (MPAs) measure implementing partners using standard criteria. They are meant to be used to inform decisions. Both MPAs and PPAs were introduced in 2015 in response to a call in the 2014 performance framework for strengthened systems to assess partner performance.

← 2. DFAT’s Monitoring and Evaluation Standards reference OECD DAC evaluation standards. While they are extremely comprehensive, they are not meant to be applied rigidly. The DFAT standards cover programme/investment design, planning for programme monitoring and evaluation, standards and processes for performance reporting, and standards and information about what should be contained in evaluation reports and Terms of Reference.

← 3. The Independent Evaluation Committee (IEC), established in 2012, provides quality control for evaluations and acts as an external advisory body. It is composed of three independent members and one department representative, and meets three or four times a year. A representative of the Department of Finance also attends meetings as an observer. The Minister for Foreign Affairs appoints the external members, who serve terms of between one and three years. The IEC also provides independent advice on ODE’s strategic direction and recommendations related to DFAT performance management policies; endorses the annual evaluation work plan; and reviews and endorses all ODE products. Additionally, it provides advice to the DFAT’s Audit and Risk Committee. The IEC reports through its chair to the Secretary of DFAT and publishes online statements about key outcomes of its quarterly meetings.