This report presents the findings and recommendations of the 2023 development co-operation peer review of the Czech Republic (Czechia). In accordance with the 2023 methodology, it does not cover all components identified in the peer review analytical framework. Instead, the report focuses on four areas of Czech development co-operation selected in consultation with Czechia’s partners and government representatives. It analyses the impact of resources on the implementation of Czechia’s long-term vision for development co-operation. It also assesses the overall development co‑operation architecture and systems to see if they are fit for purpose to implement the country’s development policy. It then explores whether efforts to develop a more programmatic approach led to improved development effectiveness and to what extent engagement with the private sector enables effective leveraging of expertise and resources. For each of these areas, the report identifies Czechia’s strengths and challenges, the elements enabling its achievements, and the opportunities or risks that lie ahead.

OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Czech Republic 2023

Findings and recommendations

Abstract

Context

The political and economic context presents both risks and opportunities for Czech development co-operation

Spillovers from the large-scale war of aggression against Ukraine by the Russian Federation (hereafter “Russia”) have derailed the Czech Republic’s (hereafter Czechia) post-pandemic recovery and intensified public spending pressures. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth is expected to slow from 2.4% in 2022 to -0.1% in 2023 before picking up to 2.4% in 2024. Steep rises in energy and commodity prices and disruptions in Russian gas and oil imports triggered a cost-of-living crisis in Czechia with a risk of broader energy shortages (OECD, 2023[1]). Inflation was at 16.3% in February 2023 and is expected to approach the 2% target only towards the end of 2024. Czechia has welcomed the largest number of Ukrainian refugees per capita. It is estimated that over 500 000 refugees have been registered for Temporary Protection, equivalent to about 4.7% of the total Czech population (OECD, 2023[1]). Providing basic services and income support to these refugees, countering the adverse impact of the energy crisis and increased defence spending have contributed to increased public spending. Domestic policy priorities are expected to focus on fiscal discipline and a co‑ordinated response to Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The government favours greater involvement in the European Union (EU) and solidarity with people impacted by crises. Parliament approved a five-party, centre-right coalition in January 2022 with Petr Fiala, leader of the Civic Democratic Party, as prime minister. Early in 2023, Petr Pavel was elected president on a platform of closer co‑operation with allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, support for Ukraine and greater involvement in the European Union. The 2022 government programme highlights that “the Czech Republic’s foreign policy will be based on anchoring its position in the European Union” (GoCR, 2022[2]). It also highlights the importance of development co‑operation as “morally right”, as well as a tool for foreign policy trade interests (GoCR, 2022[2]).

Czech development co‑operation is set up around the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a whole-of-government strategy

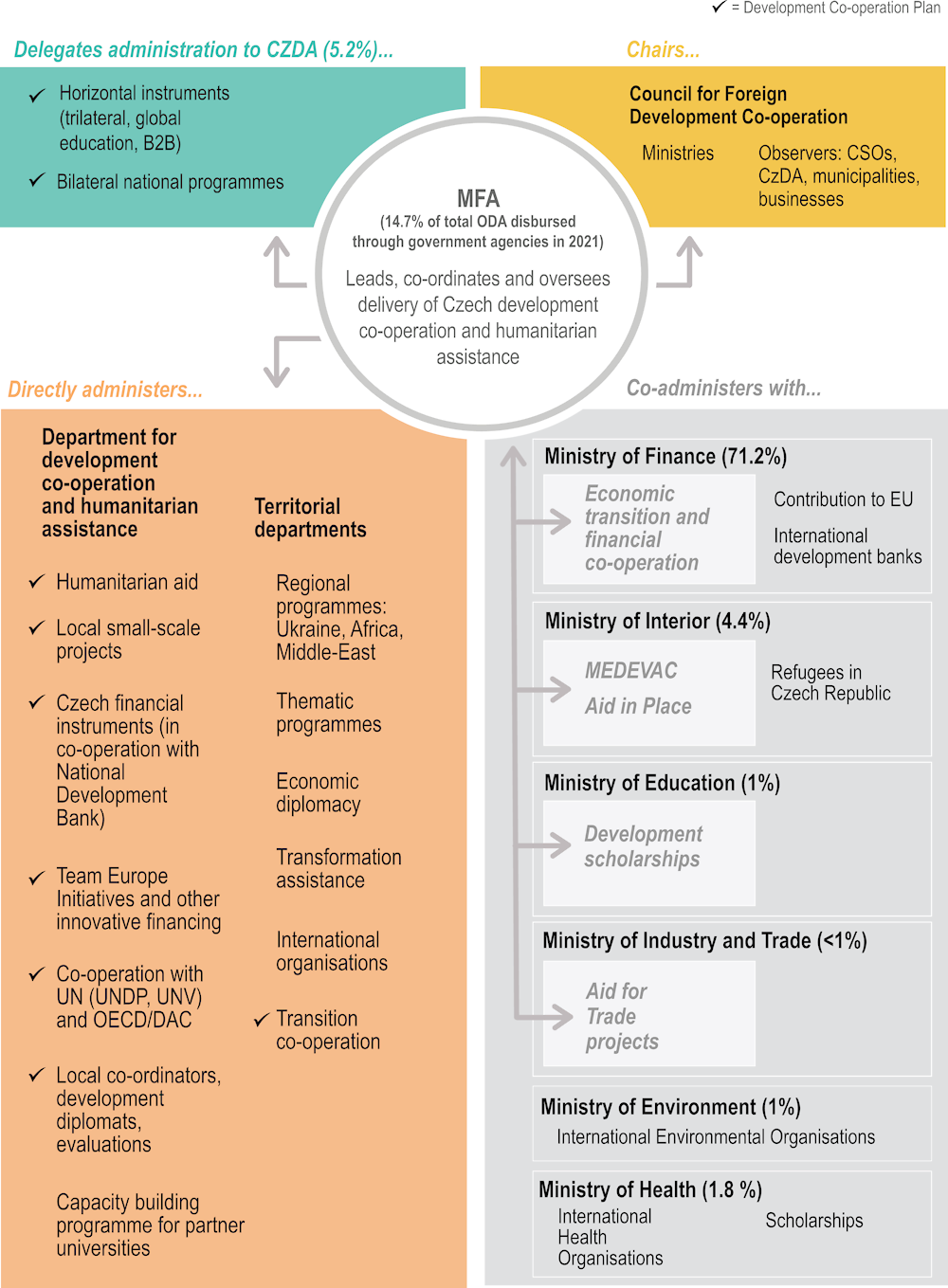

According to the 2010 Act on Development Co‑operation and Humanitarian Aid (GoCR, 2010[3]), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) leads, co‑ordinates and oversees delivery of Czechia’s ODA (Figure 1). The MFA has financial authority over the main budget line for bilateral development co‑operation and approves budgets for activities. In 2021, it disbursed directly USD 53.9 million representing 14.7% of total ODA and 45% of bilateral ODA. Most of the responsibility for development assistance falls under the Department for Development Co‑operation and Humanitarian Aid, while the Territorial Department engages in programmes funded with ODA as well as additional public resources. These programmes balance political and development objectives and respond to their own set of priorities.1 The ministry works closely with the Czech Development Agency (CzDA) a state organisation under its authority that implements bilateral country programmes and bilateral grants. In 2021, CzDA disbursed USD 18.9 million, representing 5.2% of total ODA and 21.3% of bilateral ODA.

The Ministry of Finance is responsible for mandatory payments to the European Union and multilateral development banks, such as the International Development Association (World Bank) and other financial institutions (International Finance Corporation, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development), which can be fully or partly counted as ODA. In 2021, it represented 71.2% of total disbursement of ODA (USD 260.5 million).

The Ministry of Interior provides humanitarian support to EU member states within the EU borders. The ministry is also responsible for three programmes: Aid in Place (assistance to refugees in regions of origin and support of asylum and migration infrastructure); MEDEVAC – Permanent medical humanitarian programme (deployment of Czech medical teams abroad, expert trainings and internships for foreign medical staff); and Security Development Co-operation, a technical assistance programme focused on law enforcement. The ministry is also involved in the so-called CYBERVAC, together with the Ministry of Justice, MFA (CYBERVAC co‑ordinator) and the National Authority for Cyber Security. In 2021, it disbursed 4.4 % of total ODA.

The Ministries of Education, Environment, Health, Industry and Regional Development mainly engage through contributions to multilateral systems and scholarships. In 2021, for example, 44% of bilateral ODA committed by these line ministries were contributions to Gavi, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 17% were core contributions to multilateral organisations and 27% were for scholarships. They also implement activities funded by the MFA (aid for trade, security and development; and global development education).

2022 saw a drastic change in ODA allocations, with a 167% overall increase primarily due to the cost of hosting Ukrainian refugees in Czechia. This increase had implications on the ratio between bilateral and multilateral allocations, as well as on the respective share of different ministries. Disaggregated data by institutions were not available at the time of the review and are not reflected in this report.

The Development Co‑operation Strategy of the Czech Republic 2018-2030 (hereafter “development co‑operation strategy”) (MFA, 2017[4]) provides the framework for Czechia’s development co-operation. According to the strategy, Czech development co‑operation and humanitarian assistance aim to promote stability in partner countries and foster their sustainable economic and social development, as well as prosperity. It sets out five thematic priorities covering seven SDGs, in line with what Czechia had identified as its strengths: 1) building stable and democratic institutions (SDG 16); 2) sustainable management of natural resources (SDGs 6 and 13); 3) agriculture and rural development (SDGs 2 and 15); 4) inclusive social development (SDGs 2 and 15); and 5) economic growth (SDGs 7 and 8).

As recommended in the previous peer review of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) (OECD, 2016[5]), Czechia aimed at geographic concentration. The strategy commits to focus Czech development co-operation on a limited number of countries to be identified by the government, assuring a balance between least developed countries (LDCs) and middle-income countries (MICs). Since 2016, priority countries have been Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Georgia, Moldova and Zambia. For these six countries, Czechia developed five-year bilateral co‑operation programmes. These are ending in 2023 and being reviewed to inform the next round of country programming. Czechia has also identified five countries and territories to engage within the context of post-conflict stabilisation and reconstruction processes: Afghanistan, West Bank and Gaza Strip, Iraq, Syria and Ukraine.

Figure 1. Czechia’s institutional set-up for development co-operation and humanitarian assistance

Sources: Author illustration, OECD (2023[6]) Creditor Reporting System: Aid activities, (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00061-en.

Fit for purpose: A long-term strategy facing resource challenges

The long-term strategy for development co‑operation seeks to align with the 2030 Agenda

The development co‑operation strategy (MFA, 2017[4]) attempts to connect the sustainability and development agendas. The development co‑operation strategy, which identifies seven SDGs for Czech development co-operation (see Context),2 is in line with the overall principles of Agenda 2030 of leaving no one behind. With a timeframe aligned to the 2030 Agenda, the strategy also provides a long-term perspective for engagement with opportunities to re-assess its relevance and validity. While the long timeframe enables long-term investments critical for predictability and support to systemic changes, the strategy has built-in flexibility to adjust to evolving contexts. Within its 12-year timeframe, Czechia committed to review it at least twice to inform the possible revision of objectives, as well as thematic and geographic priorities. The planned mid-term evaluation of the strategy for 2024 represents an opportunity to reflect on the progress to date and guide further improvements.

As recommended in the 2016 peer review (OECD, 2016[5]), Czechia has tried to strengthen links between international and national frameworks for the 2030 Agenda. For instance, the country has defined the competencies of each line ministry within both its national and international frameworks for implementing the 2030 Agenda: the Strategic Framework Czech Republic 2030 (Office of the Government of the Czech Republic, 2017[7]) and the development co-operation strategy (MFA, 2017[4]). Relevant inter-ministerial forums ensure active participation of key ministries in the implementation of the agenda. The Government Council for Sustainable Development3 co-ordinates the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Meanwhile, the Council for Foreign Development Co‑operation co‑ordinates development co‑operation policy.4 The government is also seeking to improve linkages between development and climate diplomacy. For instance, during its presidency of the EU Council in 2022, Czechia actively advocated for, and led, biodiversity discussions in the lead up to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. These included climate-related issues and nature-based solutions.

However, a unified approach to policy coherence for sustainable development would ensure synergies between domestic and international actions and raise development considerations within the 2030 Agenda across government. Czechia is committed to policy coherence as stated in its umbrella strategic frameworks, which is good practice. One of the eight committees of the Government Council for Sustainable Development is dedicated to “Foreign Policy Co‑ordination for Sustainable Development”. As for most other DAC members, translating this commitment into practice is challenging. Analysing the effects of domestic policies on developing countries within the Council for Sustainable Development, as planned in the national and international frameworks for the 2030 Agenda, would support stronger synergies between national and international policies. Indeed, several policy impact assessment tools (regulatory impact assessment, sustainable impact assessment, environmental impact assessment) are already used. However, the transboundary impacts of policies are not yet measured. Nevertheless, the Ministry of Environment is developing a methodology to do so.5 As observed in the 2018 OECD report on policy coherence for sustainable development (OECD, 2018[8]), a monitoring and reporting system focused on priorities, as well as synergies and trade-offs, will be instrumental in enhancing policy coherence.

Czech bilateral co‑operation adopts a whole-of-government approach but could better align allocations to its strategic focus

Czechia has the tools to develop and implement a whole-of-government approach to development co-operation. The MFA leads, co‑ordinates and oversees delivery of the country’s development co-operation and humanitarian assistance (see Context). To that end, it develops the Czech Development Co‑operation Plan and mobilises the Council for Foreign Development Co‑operation. The former provides a whole-of-government expenditure plan with an indicative budget outlook for the following two years.6 Meanwhile, the Council and its attached working groups7 have enabled shared ownership of the development co-operation strategy and stronger co-ordination at project level. Indeed, the Council discusses and approves development strategies and plans across ministries that contribute to broad ownership across government. When several ministries are engaged in development activities, the Council co‑ordinates implementation. The Council’s engagement is strong in technical working groups, especially related to implementation and approval of design of individual projects. However, in the policy and strategy working groups, participation tends to be limited to information sharing. There is an opportunity to refocus the Council’s work on policy-oriented challenges, including to accelerate implementation (see next section and Figure 4).

Built-in flexibility to the development co‑operation strategy and budget planning enables adaptation. The budget allocated to each of the six priority countries in the Development Co‑operation Plan has been stable and protected from year to year, providing long-term predictability to priority partners. Since the plan does not stipulate sectoral allocations within country portfolios, the MFA and CzDA have enough flexibility to adjust sectoral priorities in priority countries as local contexts evolve. Horizontal, thematic, regional and specific programme budgets are additional to the core bilateral development co‑operation programme, with a two-year indicative forward planning. This approach has enabled Czechia to react to evolving and sensitive contexts globally by launching new programmes in different geographic areas, while protecting funding to priority countries.

The strategy provides guidance to set up the Development Co‑operation Plan. The identification of priority and specific partner countries and territories for part of the bilateral programme contributed to slightly increase the geographic focus. For instance, scholarships administered by the Ministry of Education are now only granted to students from priority countries (see Box 3); the share of humanitarian assistance to priority and specific partners has increased and some horizontal programmes and earmarked programmes with multilaterals, such as the Czech-UNDP Partnership, target these partners.

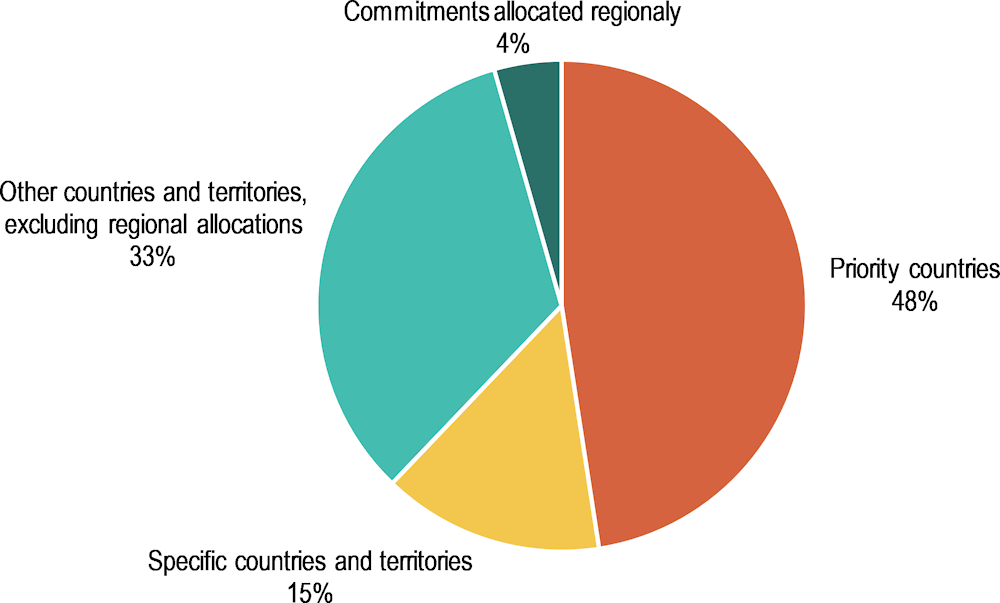

However, ODA allocations partially reflect the focus displayed by the MFA. In 2020-21, priority and specific partners represented 63% of bilateral development ODA allocable by country (58% of total bilateral ODA allocable by country) (See Figure 2) – an improvement from 46% in 2019. Each priority country accounted for 4-11% of allocable bilateral ODA. Development activities outside the plan are only partially guided by the government’s geographic and sectoral priorities; most horizontal, thematic and regional programmes are not bound by these priorities (see Context). Consequently, allocations to non-priority and specific countries apart from humanitarian assistance were fragmented geographically (and average USD 300 000 per country). However, they partially reflected the Czech COVID‑19 response, as well as the Transition and Middle East Programmes.

Figure 2. Priority countries represent 48% of allocable bilateral development ODA

Note: Humanitarian assistance is excluded from these calculations. The share of other countries and territories, excluding regional allocations, increases to 38% when humanitarian assistance is included in the calculations.

Source: OECD (2023[6]) Creditor Reporting System: Aid activities, (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00061-en.

Technical co‑operation is considered a niche element of bilateral support but makes up only a small portion of ODA. Czechia has identified technical co‑operation to countries in transition, in particular in the realm of EU accession, as a niche and added-value element of bilateral support. Yet this support is not highly visible in disbursement. Indeed, technical co‑operation only made up 3.0% of gross ODA in 2021. This confirms the challenge identified in the 2016 peer review to capitalise on this evolving comparative advantage (OECD, 2016[5]).

More clarity on how different horizontal, regional, country and flagship programmes contribute to shared objectives would strengthen the added value of the bilateral programme. Looking at budget allocations and at the diversity of programmes additional to priority country programmes, it is difficult to identify the focus of bilateral development co‑operation. Given the limited volume of bilateral ODA, continued progress in focusing the bilateral programme would enable Czechia to engage in more long-term and complex priorities, and identify precise objectives for the bilateral programme. This, in turn, would allow the country to make the case for increased investments in a context of stretched resources (see Improving bilateral programming for development effectiveness).

The fiscal and political situation presents a challenging context for securing an increased ODA budget

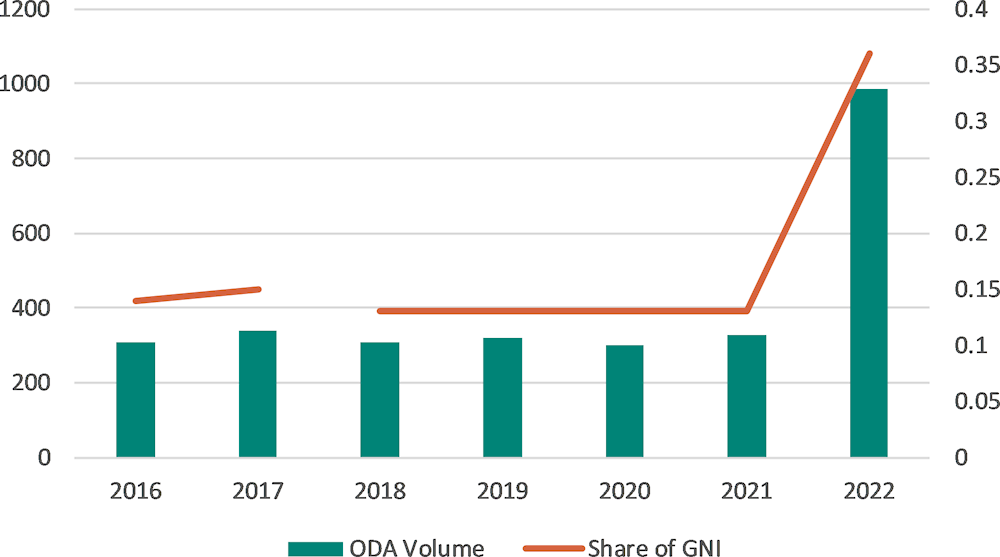

Before 2022, Czechia had not been on track to reach its national commitment to provide 0.33% of gross national income (GNI) as ODA as part of the collective EU commitments to achieve a 0.7% ODA/GNI ratio by 2030. Indeed, since the last peer review, Czech ODA has remained relatively stable at around USD 317 million per year. This represents between 0.13% and 0.15% of GNI over 2016 to 2021 (see Figure 3). This is below the DAC average, which fluctuated between 0.3% and 0.33% over the same period. In 2022, ODA increased exponentially to USD 987.1 million (preliminary data) (USD 977.9 million in 2021 constant terms), representing 0.36% of GNI. This 167% increase is primarily due to the cost of hosting Ukrainian refugees in Czechia, which was largely additional to past ODA spending. According to preliminary data, ODA volume excluding in-donor refugee costs went down by 6.1% between 2021 and 2022 as in-donor refugee costs represented 65.4% of total ODA (OECD, 2023[9]).

Figure 3. ODA has been below national commitments except for 2022

Note: For 2016 and 2017, ODA volumes are calculated as net flows; from 2018 onwards, they are calculated on a grant equivalent basis. Given that Czechia provided all its ODA as grants from 2016 to 2022, net flows equal grant equivalent.

Source: OECD (2023[6]) Creditor Reporting System: Aid activities, (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00061-en.

The current fiscal and political situation presents a challenging context for securing an increased ODA budget that goes beyond managing the repercussions of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Building political and public support for a budget increase for ODA had been largely left to the MFA to address with the Ministry of Finance, with little support from Parliament or other departments. For instance, the Council for Foreign Development Co‑operation has discussed ODA financing, but this has not yet led to a higher budget – except for 2022 and the increased support to Ukrainian refugees. As Russia’s war against Ukraine has derailed Czechia’s post-pandemic recovery and further disrupted the impressive catch-up with OECD average incomes (OECD, 2023[1]), government policy is focused on fiscal consolidation. This might further affect the development co‑operation and humanitarian budget as cuts in public spending are expected.

There are opportunities to create a compelling values-based narrative to build public support

There are opportunities to increase public support for long-term development co-operation, currently lower than the European average. According to the 2022 Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2022[10]), respondents in Czechia are among the least likely to agree that tackling poverty in partner countries should be one of the main priorities of their national government (40% vs. EU average of 67%). Public support for hosting Ukrainian refugees in Czechia in the spring of 2022 was high. Three-quarters of the population (75%) agreed the country should accept refugees from Ukraine at a time when Czechia had already welcomed the largest per capita number of Ukrainian refugees. In the first six months of the war, an unprecedented wave of solidarity in Czechia led to more than USD 180 million in funds raised privately for Ukrainian support (České Noviny, 2022[11]). Nevertheless, a recent survey shows a recent decline in public support. By March 2023, support for accepting Ukrainian refugees in Czechia had dropped to 56% (CVVM, 2023[12]).

Political support to democracy, human rights and civil society beyond priority countries is high. As stated in the 2022 Policy Statement of the Government of the Czech Republic, “the promotion of democracy, human rights and civil society is the morally right thing, but it is also advantageous for our State” (GoCR, 2022[2]). Political backing for the Transition Co‑operation programme (see Box 1) and the upcoming creation of a new parliamentary sub-committee on democracy and human rights are clear illustrations of such ambition. Similar political backing is visible for humanitarian assistance, in particular with regards to disaster risk reduction, as illustrated during the Czechia EU presidency. Political support for longer-term development assistance via an increased bilateral budget is less obvious and is in some instances linked to expectations of return in the form of follow-up projects for Czech companies (see Recommendations).

Box 1. With the transition promotion programme, Czechia leverages its expertise to promote human rights in difficult environments

More and more countries are moving towards authoritarianism and weakening human rights. Supporting civil society’s efforts towards democracy by helping local human rights activists, independent journalists and political prisoners is crucial but complex. Czechia mobilises its historic experience with totalitarianism and transition to democracy to better understand the challenges that other countries are facing.

Created in 2005, the Transition Promotion Programme aims to support democracy and human rights by applying the Czech experience to social transition and democratisation. It leverages the expertise of Czech civil society organisations (CSOs) to (1) support civil society, including human rights defenders; (2) promote freedom of expression and information, including freedom of the media; (3) promote an equal and full political and public participation; (4) support institution-building in the area of the rule of law; (5) promote equality and non-discrimination; and (6) promote human rights in employment and in the environmental context. Its annual budget has gradually increased to USD 3 million in 2022. Countries of co‑operation include Armenia, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kosovo, Cuba, Moldova, Myanmar, Serbia, Ukraine and Viet Nam.

Czechia has provided training to human rights activists and contributed to raising awareness in various politically constrained settings. For instance, in Cuba, Czechia supported dissidents and activists to deepen their know-how of documentation of personal testimonies through oral-historical methods, and more than 200 testimonies have been published. In Myanmar, Czechia supported training for progressive lawyers and regional parliamentarians. In Georgia, it used documentary films to educate youth members of national minorities about human rights and media literacy.

At the international level, Czechia has leveraged its first-hand knowledge of human rights violations to support political prisoners. Czech CSOs and Ukrainian grassroots initiatives have worked together to publicise the names of imprisoned activists and journalists from occupied territories. These names have been published in EU statements and in the UN Human Rights Council. International publicity puts pressure on Russia to release them. Czechia has also provided emergency fast track visas or long-term residence permits to those in need.

The programme has enabled building long-term relations with grassroots organisations in developing countries, including in countries where diplomatic relationships are tense. In line with the DAC Recommendation on Enabling Civil Society in Development Co-operation and Humanitarian Assistance Pillar One related to “Respecting, Protecting and Promoting Civic Space”, it is contributing to strengthening both CSOs and civic spaces. Nevertheless, the programme is facing implementation challenges, as reallocation of funding, even for small amounts, is associated with burdensome administrative procedures.

Note: This practice is documented in more detail on the Development Co-operation TIPs • Tools Insights Practices platform at www.oecd.org/development-cooperation-learning.

Source: Interviews and MFA (2015[13]), Human rights and transition promotion policy concept of the Czech Republic.

Global development education is high on the political and policy agenda, which might contribute in the long term to increased public support, as well as civic engagement and international solidarity. Czechia has developed a concerted strategy for global development education 2018-30 across government (GoCR, 2017[14]). To that end, it has leveraged European declarations and materials to make the case for global education and to update school curricula. Key priorities include critical thinking, media and digital literacy, and sustainability. Funding for development awareness increased slightly from USD 0.74 million to USD 1.89 million between 2019-21 (USD constant price). Nevertheless, implementation is key and this new strategy will require time to achieve measurable results.

Czechia can build on ongoing transparency efforts to build a stronger coalition for support by communicating shared results. Czechia has employed good practices to engage key stakeholders and communicate on its development co‑operation. This includes consulting on the development co‑operation strategy, as well as country strategies, and publishing projects and programme evaluations. The country also provided information on all its funded projects through the mapotic.com website, presenting a global map of ODA. Nevertheless, communication remains siloed. Most programmes have their own communication materials and branding and do not showcase how the different initiatives contribute to shared objectives. In addition, communication is mainly focused on general project-level information and activities. This makes it difficult to understand the results of Czech bilateral co‑operation and its positive contribution to long-term development. Further efforts to showcase the long-term results of key Czech priorities might support increased investment in the bilateral programme if accompanied by further improvement of the institutional set-up (next section).

Recommendations

Czechia should continue to focus its development co-operation to better reflect strategic priorities in its allocations and to provide a clear basis for communicating the added value of Czech development co-operation to the public and parliament.

Capitalising on having met its national commitment of 0.33% of GNI as ODA in 2022, Czechia should agree on a long-term plan to maintain the ODA/GNI ratio at least at the level of the national target.

Fit for purpose: An institutional set-up hampered by rigidities and capacity constraints

Institutional and methodological reforms have focused agency work on implementation and increased country perspectives in decision making

The latest institutional reform has shaped the roles of the MFA, CzDA, Czech embassies in priority countries and the Council for Foreign Development Co-operation. The development co‑operation methodology, revised in 2021 in consultation with stakeholders, clarified the roles of the respective counterparts (MFA, 2021[15]). This process considered outcomes and recommendations from audits and controls of Czech development co-operation, including of CzDA as an institution (which found limitations in internal control and management of funds). The agency refocused on implementation and project management to increase its capacity to implement large-scale projects, reinforce the commitment and disbursement of funds, and deliver on delegated co‑operation with the European Commission and other bilateral or multilateral partners. The MFA has retained strategic decision making and management of some horizontal programmes and is now actively consulted on the feasibility and selection of funding instruments during formulation. The methodology also enhanced the consultative role of the Council for Foreign Development Co‑operation and the role of embassies (see next section).

Empowered country presence could improve efficiency and effectiveness

The institutional reform also increased country presence through Czech embassies, enabling a development co‑operation responsive to country context, and active engagement in co‑ordination of providers. Most of Czechia’s country presence is through development diplomats posted in its six priority countries and in most countries where it engages in the Humanitarian-Development Nexus.8 Embassies can also recruit local staff as project co‑ordinators to support development diplomats with project management and local institutional knowledge. Since the Czech Development Co‑operation methodology was revised in 2021 (MFA, 2021[15]), embassies have more responsibility in informing the selection of priority countries, identifying, and monitoring projects, and identifying opportunities for EU delegated co-operation. This increases the local perspective in decision making. As the sole representative of Czechia in countries, embassies actively co-ordinate with other development co-operation providers (see Improving bilateral programming for development effectiveness). In Georgia, for example, such an approach has enabled Czechia to identify niche sectors while responding to the needs its local partners.

Further empowering country representation, be it through the embassies and through agency staff, would increase efficiency and effectiveness. While the role of embassies has expanded and the number of staff overseas increased, the ratio of staff in headquarters remains high (80%), and among the highest compared to other DAC members with similar sized bilateral portfolios.9 CzDA still cannot be represented officially in partner countries and territories and register country offices. Consequently, it cannot open bank accounts, recruit local staff or post Czech staff. It did find temporary leeway for staff in charge of EU delegated co‑operation, but this sometimes confused other providers with regards to representation and division of labour (see next section). In addition, most development diplomats have a portfolio combined with economic or consular activities,10 which affects their ability to engage on the development agenda. Diplomats’ time is stretched between their responsibilities for engaging and co‑ordinating with government and partners, directly managing the small grant scheme for local CSOs,11 supporting implementing partners and monitoring agency projects. In addition, embassies in priority and specific countries and territories do not systematically have a full overview of all activities beyond those administered by the agency. Finally, there is no delegation of authority to embassies, as Prague makes all decisions and controls all functions. This adds an administrative burden to already stretched resources. Czechia plans to engage in more complex contexts, including larger projects in Africa where its network of implementing partners is not as strong. An increased country presence would be critical to identify strong partners and adapt programmes as contexts evolve.

Long administrative procedures, tight capacities and a focus on Czech partners have consequences on efficiency, partnerships and development impact

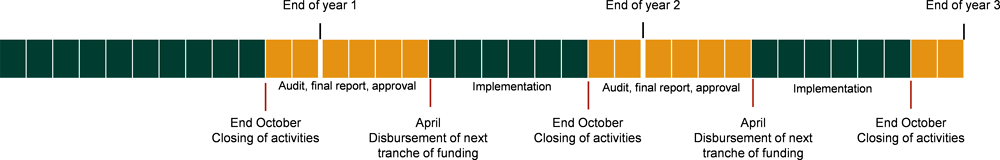

Long administrative procedures with centralised control mechanisms are impacting efficiency and effectiveness. Most of the bilateral programme is delivered through multiple small projects. All public institutions engage in 346 new projects per year with an average budget of USD 104 000 per project (as recorded in the OECD Creditor Reporting System); CzDA alone takes on 56 new projects per year with an average budget of USD 99 000.12 Each project, without distinction between project size or professional capabilities of the implementer, is subject to one-year financing and comprehensive auditing rules with centralised decision making. While three-year projects are becoming more common, most projects still have yearly contracts. This leads to a high administrative burden, start-up delays and shortened implementation periods for partners (see Figure 4). Partners can continue to implement projects between the closing of activities (in October when reporting to embassies) and the approval of the next tranche of funding. However, they have to mobilise their own cash flow from October to April/May. This is proving challenging for partners with limited financial capacities as for those responsible for capital-intensive projects. It also impacts predictability for both partner governments and implementing partners and makes it more difficult to invest in longer-term change. The tasking of a ministerial working group to work on facilitating multiannual funding for activities outside of Czech borders is a positive step.

Figure 4. Annual planning shortens implementation timeframes for partners reporting to embassies

Note: Partners can continue implementing projects during the audit and approval phase with their own cash flow. Closing of activities can be postponed to November for projects not reporting to embassies.

Regulations prevent from working more directly with local partners, which hampers effectiveness and partnerships. Partnership is a key value of Czech development co‑operation. All projects must be implemented in collaboration with a partner registered in the priority or specific country or territory. However, most funding (in terms of volume) – from grants to CSOs to private sector instruments – is tied to Czech partners. Except for the small grant scheme, localised humanitarian projects and EU delegated co-operation, the agency and the ministry cannot engage directly with a local partner (see Recommendations). In addition, regulations of grants add complexity to the partnerships between Czech and local non-governmental organisations (NGOs): Czech NGOs can only transfer EUR 80 000 (= USD 84 210) per year to their local implementing partners. Working with Czech partners can bring specific added value by mobilising Czech expertise. It can also contribute to strengthening advocacy and broad-based public support for development co‑operation. However, such an approach can also create inefficiencies and limitations in finding the implementing partner best fit for purpose. In practice, it also limits accountability between CzDA and the end beneficiary as there are no contractual frameworks between the two, only through intermediaries. Finally, in some instances, the rationale for selecting implementing partners led to misunderstanding with European partners when engaging in joint programming. Czechia can learn from its experience with its untied instruments for continued progress in engaging more directly with local actors for increased efficiency and sustainability.13

Capacity constraints increase implementation delays and reduce space for strategic engagement. Both the MFA and CzDA suffer from limited administrative, managerial and financial capacities, and lack of digital solutions, which contribute to administrative delays. A low ceiling on recruitment in the agency14 and relatively low allowance for administrative costs15 restrict flexibility in managing human resources. While highly committed and energetic, the 15 staff in the MFA and the 21 in CzDA in headquarters have limited capacity to engage in policy guidance and to develop or identify relevant technical tools. Meanwhile, embassy staff are stretched between co-ordination and monitoring (see Improving bilateral programming for development effectiveness). Nevertheless, Czechia has made efforts to increase capacities. For instance, the United Nations Volunteers programme helps build expertise of potential recruits and the MFA has made efforts to train staff on development co‑operation, including by adding content on development co-operation in the Diplomatic Academy curricula. However, not all training materials, including those offered through the Diplomatic Academy, are offered to agency staff or local project co‑ordinators. They are also aimed more for generalists than technical staff. As observed in the 2016 peer review, increased tailor-made training and networks of development diplomats could further strengthen capacities given that tasks demanded of embassies are often technical.

The advantages of the institutional set-up are not fully leveraged

While the latest institutional reform sought to increase the agency’s capacities in legal issues, procurement, risk management, cross-cutting issues and quality control, the resourcing of the agency and regulatory framework hamper effectiveness. Multiple rotation at director level has slowed settlement of internal reforms. Stretched human resources facing limited opportunities for geographic mobility or career development are affecting institutional learning and effective implementation. For instance, while CzDA can mobilise external expertise for strategic and thematic support, core staff are mostly focused on administration. As such, they have limited opportunities to learn and engage in expert networks and learn from peers. Nevertheless, the MFA is working to increase salaries in the agency to attract and retain staff. In addition, due to its inability to be present in priority countries, CzDA also relies partly on development diplomats for monitoring. With all development projects being monitored at least twice a year, CzDA and the embassies in priority countries jointly prepare annual monitoring plans. These divide responsibilities with some share of monitoring undertaken by CzDA headquarters staff (usually during one business trip), and the rest by development diplomats and local co‑ordinators. This competes with diplomats’ time to engage in policy dialogue and undermines the rationale for a stand-alone agency.

In the institutional set-up and resource-constrained context, Czechia does not make the most of working through an agency. According to an internal cross-analysis of DAC members, institutional models that divide strategy and implementation are successful under three conditions. First, mandates and division of labour must be clear. Second, staff must have the right capabilities. Third, funding models must be flexible enough to fund emerging priorities. Models where different institutions manage policy and implementation can, in theory, help strengthen technical expertise. However, they can also limit career opportunities for agency staff and expertise for Foreign Affairs policy staff, especially in contexts where human resources are constrained. Agencies implementing programmes on behalf of other development co‑operation providers can also become hostage to other policy agendas. In the case of Czechia, the division of labour between the agency and the MFA in headquarter is clear. Risks of overlap between policy setting and implementation are limited, and bilateral and delegated co‑operation are clearly aligned. However, the agency set-up does not enable strengthening of its development expertise or support delegation of authority, which are critical for adaptive management.

There is potential to mobilise more learning from EU delegated co-operation to reinforce the system

Czechia is engaging in EU delegated co-operation in a responsible manner and learning from its experience. EU delegated co‑operation represents only a small share of the development agency budget: 4% of funds administered by the agency (including salaries) (MFA, 2021[16]). Czechia engages in EU delegated co-operation after considering the capacity of the agency to deliver on the projects. It does so in countries where it has developed an identified niche, mainly as a junior partner. CzDA administers five projects in the three middle-income priority countries (two in Bosnia and Herzegovina, two in Georgia and one in Moldova) as a junior partner. It plans to expand to Zambia where it would act as a senior partner for the first time. In addition, Czechia invested time to learn from its first EU delegated project launched in 2018 in Moldova. Following an internal evaluation of the project, Czechia identified and worked on key challenges to improve implementation. This includes communication among partners at inception phase and strengthening representation and capacities in-country. The agency has created guidelines to support staff with implementing delegated co‑operation. Czechia has also found ways to post staff funded by EU delegated co‑operation in partner countries even if the agency cannot formally register offices in other countries.16

Further investment in institutional learning would help Czechia reach its objectives of institutional strengthening and move from individual learning to system improvement. According to the development co‑operation strategy, engaging in EU delegated co‑operation should help disseminate and multiply agency programmes, and support the agency as a reliable partner of the European Union (MFA, 2017[4]). Clear alignment between EU delegated co‑operation and country strategies contributes to the objective of multiplying bilateral programmes (see Improving bilateral programming for development effectiveness). However, it is less clear how investments are strengthening the agency beyond clear individual learning. As observed in Georgia, staff are learning from engaging with senior partners, including on technical expertise such as gender mainstreaming or results monitoring. However, staff recruited for EU delegated co-operation and posted in partner countries only administer delegated projects, as contractually expected. Meanwhile, oversight and monitoring of the bilateral programme, including agency projects, relies on the embassy. This does not facilitate learning exchanges between agency and embassy staff, as observed in Georgia. In addition, staff working on EU projects are recruited on short-term contracts with no opportunities to stay in the agency after one extension, given the cap of 21 staff within the agency. With this constraint, and limited mechanisms for learning and experience sharing in Prague and in partner countries, the current set-up does not allow the agency to leverage the strengthened expertise and consolidate core capacities fully and systematically.

As Czechia plans to engage more in EU delegated co-operation, it will need to further strengthen core functions of CzDA, while ensuring investments do not come at the expense of resourcing the bilateral programme. Czechia also plans to engage in EU delegated co‑operation as a senior partner in Zambia in view of relevant experience and a network of local partners, collected and developed in recent years. Such an evolution will require an empowered country presence to manage the implementation risks linked to larger projects under EU regulations when agency staff in countries have neither decision-making authority nor official status. Decentralising operations to country representatives requires investing in strong headquarters support in addition to covering costs of posting staff. However, these needed investments in the agency must also strengthen core capacities to ensure EU delegated co‑operation does not come at the expense of the bilateral programme.

Recommendations

Czechia should re-assess its institutional set-up and the functioning of an agency within it, including by:

addressing constraints being faced by CzDA in terms of number of staff and country presence and their implications for the institutional set-up

delegating more authority to Czechia’s in-country representation

building mechanisms to ensure that investments in EU delegated co-operation reinforce Czech bilateral development co-operation.

Czechia should continue strengthening human resource capacities within the MFA and CzDA, including by investing in training programmes accessible to all staff, and optimising the balance between administrative and specialist skills, including by making use of external expertise when relevant.

To select the most relevant partners to achieve development objectives, Czechia should continue to make progress in untying its development co-operation across all instruments and reduce obstacles to partnering with non-Czech entities, especially local ones.

Czechia should identify ways to provide multi-year funding, building on the work of the multi-annual financing task force and experience with humanitarian support, and to streamline procedures for multi-year projects.

Improving bilateral programming for development effectiveness

Effective co-ordination with other development co-operation providers, especially with the European Union, helps bring programmes to scale

Czechia supports multilateral institutions effectively, but contrary to its strategy, the number of multilateral partners remains relatively high. Most support to multilaterals is core funding (92% in 2021, or USD 278 million), virtually all of which is assessed contributions. When engaging with multilateral partners, Czechia generally uses partner reporting systems. The ministry now engages systematically with permanent representations in Geneva and Brussels when designing and engaging in earmarked programmes to ensure synergies between its EU and other multilateral engagements which is good practice. In line with its strategy, it has aligned earmarked funding to multilaterals with sectoral and geographic priorities. For instance, the partnership with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and earmarked contributions to UN Volunteers and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are focused on priority countries and aim to complement Czech programmes. The development co‑operation strategy aims to prioritise a small number of partners so the country can bring visible added value and assert its influence effectively (MFA, 2017[4]). However, the number of multilateral partners remains high. In 2021, Czechia had 22 multilateral partners benefiting from earmarked contributions (OECD, 2023[6]). This raises questions about the ability of Czechia to engage strategically in these partnerships.

Czechia increasingly co‑ordinates its development co‑operation with European member states and the European Union, in line with its geographic and thematic priorities. According to the development co‑operation strategy, Czechia “will pro-actively advance its national priorities and promote its expertise, especially in the European Union” (MFA, 2017[4]). The MFA structure was recently changed, with one division focusing on the European Union which reflects its growing importance. Most trilateral projects17 supported by Czechia are with the European Union. This allows the country to leverage the expertise of its NGOs to support EU development projects (MFA, 2019[17]). The five delegated co-operation engagements of Czechia focus on priority countries and on selected sectors identified in the bilateral development programme, bringing substantial additional funding that complements bilateral activities.18

Czechia increasingly co-ordinates with other European development co‑operation providers on specific themes, but its geographic focus is dispersed. Czechia is part of 15 Team Europe Initiatives (TEIs), which is significant for the volume of bilateral ODA. In these TEIs, the country focuses on sectors where it has expertise such as agriculture, environment, natural resources, and health. Sometimes, it shapes TEIs to include these priority sectors. However, while the thematic focus of Czech engagement is clear, it is not the case regarding geographic concentration. Czechia participates in TEIs beyond its priority countries (e.g. TEIs in Tunisia, the Sahel, Mongolia, Armenia, Ghana). This could be used as a good way to learn about potential priority countries but could also lead to dispersing its resources too widely (see Fit for purpose: A long-term strategy facing resource challenges).

In Georgia, Czechia has positioned itself in niche sectors, contributing to efficient division of labour among development co‑operation providers. Czechia has positioned itself in three sectors: protected landscapes (building on experience with similar forests in Czechia); good governance (building on Czech experience transposing EU directives into Czech laws) and primary health sector (leveraging Czech CSO expertise). In two of these sectors, Czech projects are being scaled-up with the involvement of other development co-operation providers. For protected landscapes, it is working with Austria and the Slovak Republic. Meanwhile, it works with Expertise France for health and social protection. Czechia participates actively in such co‑ordination by co‑chairing one of the working groups in Georgia. The embassy has also actively participated in EU joint analysis, laying the ground for a shared EU vision of development priorities.

Building on successful efforts to reduce fragmentation and create synergies would further increase impact and sustainability

Czechia has developed what it calls integrated approaches or integrated solutions to reduce fragmentation of its development co‑operation and to increase impact and sustainability. Greater integration aims to create a multi-sectoral and multi‑instruments approach by linking the different projects right from the planning stages. This approach was included in the methodology for international development co‑operation (MFA, 2021[15]) as part of its overall revision and update in 2021 to support integration across the programming cycle.

The integrated approach, piloted through several models, helped reduce fragmentation of the bilateral portfolio. First, Czechia has made efforts to better connect the development co‑operation and humanitarian portfolio under the Department for Foreign Development Co‑operation and Humanitarian Aid. This was especially true under the disaster risk reduction agenda where it supported early warning mechanisms, as well as training on crisis management and resilience building in priority countries. Second, through a UNDP trust fund, Czechia is connecting two instruments (Experts on Demand and a Challenge Fund) to provide innovative and technical solutions to partner countries and territories. By upgrading the “Sending of Teachers Programme” into the “Capacity Building for Universities Programme” and aligning it more closely with the “Government Scholarship Programme”, the MFA is building synergies between two instruments while increasing geographic focus (see Box 3). Third, within country programmes, Czechia manages “integrated projects” that aim to solve development challenges by providing both policy and practical solutions and across sectors. One example is the sustainable development of the Area of Aragvi Protected Landscape and the Local Communities project in Georgia (see Box 2). This integrated approach is made possible at country and territory level by three factors. First, budget allocations defined by country give flexibility to plan across sectors and themes. Second, the MFA and CzDA can mobilise a diversity of instruments.19 Finally, the role of Czech representation in countries has increased during inception and monitoring, making it possible to connect programmes.

The “integrated” approach will require investment in strategic planning at country level. Country programmes remain fragmented in multiple projects. In its priority partner countries, Czechia implements an average of 27 projects per year (excluding scholarship and core contributions) in a maximum of three sectors. Most implementation is through calls for tenders and project proposals. Even within sectors, the coherence between projects can improve. For instance, an evaluation of health projects in Cambodia (MFA, 2023[18]) found that projects were complementary but operated side by side and did not lead to synergies. In Georgia, the “integrated” projects represented 35% of the volume of commitments under the country strategy: 30% were originally designed as integrated and 5% were added during implementation. In other words, two-thirds remained fragmented. Experience in Georgia highlighted the importance of dedicating more time and expertise to design comprehensive solutions within country programmes and subsequent projects rather than relying on ad hoc synergies (see Box 2).

Box 2. Integrating projects for better impact in the Aragvi Protected Landscape

Despite extensive natural resources and tourism development potential in the Aragvi area, insufficient infrastructure, including electricity network and public services, as well as lack of viable economic opportunities, contribute to a population drain. In addition, some remote areas are inhabited only four to six months a year.

“Sustainable development of the Area of Aragvi Protected Landscape”, launched in 2018, aims to provide a multi-sectoral and multi-layer solution to strengthen the socio-economic well-being of the local communities while protecting the natural and cultural heritage of the region. Initially piloted by Czechia, it now mobilises different strategies and funding instruments of Czech and Slovak development co‑operation, with co-financing from Austria for a total budget of about USD 3 million: capacity building and awareness raising, grants, empowerment of the local population for decision making and technical assistance.

During implementation, the programme contributed to the following:

improved external co-ordination by leveraging additional funding and engaging with more development co‑operation providers, namely Austria and the Slovak Republic (Slavkov co‑operation)

improved internal co‑ordination by mobilising multiple Czech instruments around a shared goal, thereby creating more consistency in the Czech bilateral portfolio in Georgia and filling in gaps not identified at formulation stage.

This pilot integrated approach highlighted the importance of investing time and expertise in the preparatory phases based on the in-depth analysis and solid management structure of the programme.

Note: This practice is documented in more detail on the Development Co-operation TIPs • Tools Insights Practices platform at www.oecd.org/development-cooperation-learning.

Source: internal monitoring reports and interviews.

The integrated approach could be further leveraged by looking at all instruments and programmes mobilised in each partner country. Indeed, country strategies mainly reflect activities by CzDA and not necessarily those implemented by Czech line ministries, limiting opportunities for integration. However, clear opportunities exist to build synergies, including between CzDA projects and the Transition Promotion Programme in countries where both are active. This is especially the case where Czechia aims to increase its engagement with civil society.20

A clearer focus on poverty, systematic mainstreaming of cross-cutting issues and increased learning from results would increase effectiveness

Active engagement and open dialogue with governmental and subnational partners enable a bottom-up approach to identify needs and align to country priorities. Bilateral development programmes are based on partner country strategies and are submitted for partner country’s approval. At project level, based on the new methodology for international development co‑operation, local partners initiate new project concepts by filling an “identification” form stating rationale, and expected outputs and outcomes. Ensuring alignment with a partner’s needs through this bottom-up approach is a good first step towards development impact.

However, the focus on leaving no one behind is not systematic across projects, even though the overall strategy aims at reducing poverty and inequality. For instance, the protected landscapes project in Georgia has defined inclusive targets for its beneficiaries: at least 40% women and 40% men, at least 20% youth under 30, at least 2% of people with disabilities and a balanced representation of all three cultural communities in the region. Similarly, the Development of Adult Alternative Social Services project in Georgia targets adults with physical and mental disabilities. However, other projects, notably in infrastructure, do not have explicit leave-no-one-behind objectives, even though the principle is pivotal in the Agenda 2030 and an integral part of development co‑operation activities. CzDA is developing new social and environmental standards that include particularly vulnerable groups such as Indigenous Peoples, internally displaced people, ethnic minorities, youth, children and people with disabilities. This is a positive first step to ensure that all projects focus on tackling poverty and exclusion, even when the main focus is to support the transition of economies.

Czechia has advanced on cross-cutting priorities. The development co‑operation strategy, as well as bilateral development programmes, identifies the following cross-cutting priorities: good governance; human rights, including gender equality; and protection of the environment and climate. Czechia has made progress on these priorities, with performance on gender and environment markers increasing, although it remains slightly below the average of DAC members.21 Addressing cross-cutting issues is part of administrative requirements: implementing partners fill templates with sections on cross-cutting issues to ensure that projects do no harm or make positive contributions.

However, implementation varies greatly across implementing partners and countries. For instance, the Czech non-profit organisation People in Need22 has expertise in promoting gender-sensitive and gender-transformative projects. It also has experience creating “local action groups” that promote good governance and participation of local stakeholders to decision-making processes. However, other implementing partners, including in the private sector, have less expertise and interest on these topics. CzDA and the MFA have limited capacities to meaningfully assess, monitor, or learn from implementing partners on these priorities, which can create risks for Czech development co‑operation. At country level, staff sometimes undertake gender assessments to inform project design, learning from other providers such as the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). However, such practice is not promoted across countries.

The MFA is developing principles and internal checklists for its cross-cutting priorities. Czechia had developed a comprehensive methodology for evaluation of cross-cutting themes in development co-operation. However, this methodology is designed for evaluation (not to support project design and monitoring) and has not been used due to its complexity. The MFA is therefore developing principles for its cross-cutting priorities based on its international commitments. It is also preparing internal checklists to ensure that cross-cutting priorities are considered at all stages – from programming to evaluation. In addition, CzDA is developing detailed standards for each cross-cutting priority.

Continuing to strengthen capacity in headquarters, as well as developing systematic processes and clear central guidance, would help bridge the gap between policy and implementation of cross-cutting issues. In MFA headquarters, one staff is responsible for cross-cutting themes but has limited time for them as they come on top of other operational tasks. As Czechia prepares new guidance on cross-cutting priorities, it may benefit from and could engage more with OECD DAC networks and communities of practice. Czechia could use the DAC Secretariat and the statistical peer review mechanisms to improve the screening and use of gender and Rio Markers. Going forward, Czechia would benefit from having dedicated staff on cross-cutting issues and from stronger guidance and training to all staff to ensure that cross-cutting priorities inform project design and are systematically monitored.

There are positive examples of mobilising evaluation findings for decision making to improve the quality of programming. Czechia has made progress on the past peer review recommendation to use evaluations for evidence-based decisions and accountability. The evaluation function is embedded in the Department of Development Co‑operation and Humanitarian Aid. Since it is not in charge of project implementation, the function is relatively independent. The department also collaborates with the Czech Evaluation Society, which brings together evaluators and evaluating companies, conducts training and workshops, and disseminates a public code of conduct for evaluators. Czechia now has a two-year evaluation plan, proposed by the MFA in consultation with CzDA and other stakeholders responsible for ODA programmes and approved by the Council for Foreign Development Co-operation. It generally focuses on strategic evaluations, looking at sectors, countries or instruments rather than at project level – which is good practice. Following a meta-evaluation managed by the MFA, all evaluations include recommendations now ranked by priority level, which makes them more useful for decision making. Evaluations have been used to redesign some instruments of Czech development co‑operation. These include the scholarships programme (see Box 3) and the Business to Business (B2B) programme (see Recommendations). All evaluations are published on the MFA website with a summary in English.

Box 3. Learning from evaluations to improve scholarships and support universities in partner countries

Czechia has redesigned its scholarships programme to reduce brain drain, increase rate of success and contribute to development co-operation. Before, many students studied in Czech, which may have encouraged them to stay in Czechia after their scholarships ended rather than returning home. With the redesign, scholarship students are mostly enrolled in English-language programmes. The programme also promotes a guarantee of assignment upon return from the home university and favours higher degrees to minimize drop-outs. It is closely linked to bilateral development projects, encouraging study in related sectors. This enables returning former scholarship holders to obtain expert positions in project implementation or evaluation in development co‑operation projects.

The Sending of teachers programme has been redesigned to a programme called “Capacity building of public universities in developing countries”, focusing on education, research and management (e.g. fundraising, partnerships with private sector, etc.). It includes mutual mobility of teachers, students, and non-teaching staff of universities. To increase participation of Czech universities, the programme now allows them to send teachers for short periods (e.g., one to three months), which makes it easier for smaller universities to get involved.

This approach has started to bring results. The language of study for scholarship holders shifted from 77% in Czech to 66% in English. The focus of scholarships on students with higher degrees has reduced the drop-out rate from 50% to less than 10%. Participation of Czech and partner universities has increased from 2 to 13.

Focusing on fewer countries deepened partnerships. Both programmes are now focused on the same seven countries. Students with strong potential to become future teachers or researchers on subjects of mutual interest are encouraged to apply to the scholarships programme. Focusing on fewer countries has helped deepen the scope of the partnerships with universities (now including management and research collaboration) and enhance synergies between scholarships and development co‑operation.

In both cases, evaluations including internal and external stakeholders have proven to be a strategic tool to improve programmes. Inclusive discussions with all stakeholders, including successful and unsuccessful scholarship holders helped understand how to improve programmes.

In addition, adjusting to the needs of partner universities was key. Following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, Czechia has focused on supporting partner universities in Ukraine and Moldova to integrate internally displaced students and deploy digital solutions.

Note: This practice is documented in more detail on the Development Co-operation TIPs • Tools Insights Practices platform at www.oecd.org/development-cooperation-learning.

Source: Interviews, MFA (2018[19]), Evaluation of the Government Scholarship Programme of the Czech Republic for students from developing countries provided in 2013-2017 and MFA (2019[20]), Evaluation of the Sending of teachers to developing countries over the period 2016-2018

Strengthening the long-term focus, reliability and usage of the results systems across instruments would allow Czechia to better manage ODA for sustainable results. Results are not sufficiently focused on long-term outcomes and not systematically used for decision making. Both bilateral co‑operation programmes and project documents include target outputs and outcomes linked to specific SDGs and aligned with partner country objectives (See Table 1). However, in some project documents, what are identified as outcomes are rather outputs. This distinction limits Czechia’s ability to measure and understand change. Furthermore, it is sometimes difficult to assess the contribution of the Czech projects to identified outcomes because the short-term nature of the projects does not always allow for long-lasting results. An evaluation in Cambodia (MFA, 2023[18]), for instance, showed that new equipment helped improve hygiene and access to drinking water in hospitals23 but that training of medical staff required more time.24 In addition, capacity to measure baseline indicators and set targets is limited, which affects the reliability of results. Finally, there is some reflection in each country strategy on learning from past results, but overall results are not systematically used to adjust projects and inform programming. Due to lack of delegation of authority, staff in country offices have limited leeway to adjust projects when results are not achieved or the context changes. Headquarters staff also have limited capacity to adjust projects due to the high number of projects overseen per country manager and the focus on financial management rather than results-based management.

Table 1. Project documents have target outputs and outcomes linked to specific SDGs

Example from the “Improving quality of maternal and child healthcare services in three hospitals in Kampong Chhnang province” project in Cambodia

|

Objective stated in Cambodia bilateral programme |

Project objective |

Project outcome indicators |

Project output indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

|

End preventable deaths of newborns and children under five years of age and reduce maternal mortality in selected areas (SDG 3.1. +3.2.) |

Reduce mortality rates of newborns, children under five years of age and mothers at three target hospitals. |

|

|

Source: Cambodia bilateral programme and Cambodia maternal health project document.

Recommendations

Czechia should pursue its efforts to develop a more programmatic approach by developing country strategies that encompass all Czech instruments across government, identifying a limited number of long-term results it expects to achieve in each country, and by investing in strategic planning.

Czechia should invest time and resources in defining robust country-level baselines and targets that can be monitored and used for decision making and communication to improve delivery of the bilateral programme.

To strengthen the quality of its development co-operation, Czechia should bridge the gap between policy and implementation by:

ensuring that all country strategies and development projects explicitly address poverty and/or inequality

continuing to strengthen capacity in headquarters and use guidance to systematically consider good governance; human rights, including gender equality; and protection of the environment and climate.

Enabling private sector engagement

Czechia has developed a pragmatic approach to test and improve instruments to engage the private sector but with mixed results and no dedicated strategy to structure the efforts

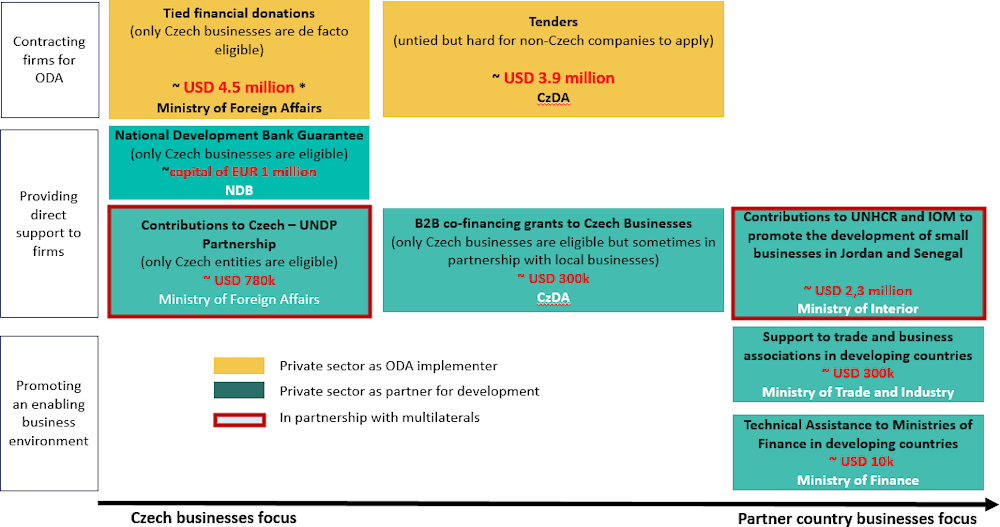

Czechia has multiple instruments to engage the private sector, but private sector actors remain primarily ODA implementers. Czechia works with several instruments managed by six institutions, with different objectives (see Figure 5). These range from contracting firms for their expertise to providing direct support to Czech firms and promoting an enabling business environment through technical assistance. However, all have relatively small budgets. In line with peer review recommendations in 2016, Czechia has tried to engage with private sector actors as development partners. However, private sector actors remain primarily ODA implementers with high volumes of ODA channelled through tenders and tied financial donations,25 a relatively new instrument created during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 5. Private sector actors are primarily engaged as ODA implementers, but several other instruments have been developed

Note: *These figures are for 2022. Others are for 2021

Source: OECD (2023[6]) Creditor Reporting System: Aid activities, (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00061-en, MFA (2021[21]), Development Co-operation of the Czech Republic in 2021, and information collected during peer review from the MFA.

Czechia has refined its B2B instrument pragmatically, but the private sector seems to have limited appetite for it. The B2B programme has been in place for several years, but it is small and decreasing in scale. Disbursements in 2022 were less than USD 360 000, four times less than in 2019 (MFA, 2019[22]; MFA, 2021[21]). 26 Following an independent evaluation of the programme in 2019, the MFA sharpened eligibility criteria and decreased subsidies27 offered to private sector entities to ensure stronger commitment to projects and to further promote sustainability. These adjustments, however, seem to have reduced the pool and appetite of private sector actors for this instrument, along with the limitations caused by the pandemic.

Czechia has also launched a guarantee which is a good way to mobilise private sector financing for development, but similarly, private sector interest seems to be lacking. In 2018, NDB launched the International Development Co‑operation Guarantee, a pilot programme endowed with EUR 1 million (= USD 1.05 million in 2022), but to date the guarantee has not been used. This is mainly due to limited demand from Czech small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to invest in development projects in developing countries and from Czech commercial banks to finance such projects, even with a guarantee. The European Commission is pillar-assessing NDB so it can benefit from the European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD+) delegated guarantees. However, access to EFSD+ will increase the volume of the guarantee and therefore require NDB to develop its capacity to source more bankable projects. Yet NDB already finds it difficult to entice the private sector to use its guarantee.

The absence of a clear vision on why and how engaging with the private sector brings added value undermines the coherence and logic of testing various instruments. The development co‑operation strategy indicates the importance of private sector engagement. However, Czechia could usefully reflect further on why it engages with the private sector and how to maximise additionality and impact based on past results. It could also examine the potential added value from existing instruments working on the enabling environment, including learning from its own history of transition. Such a strategy could help improve understanding among stakeholders on the role of the private sector for development and promote a shared approach across ministries and instruments. For instance, Switzerland has developed a “General Guidance on the Private Sector” that defines the why and how of engaging with the private sector. For its part, the Netherlands has a Theory of Change that defines the challenges for private sector development, and the changes leading to desired impacts and outcomes.

Engagement with the private sector is too focused on Czech companies

Czechia has supported initiatives aimed at promoting local private sector development in partner countries, as part of its humanitarian and stabilisation efforts. In 2021, the two largest multilateral activities supporting private sector were managed outside of MFA. These were earmarked contributions to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in the framework of the Aid in Place migration-related programme managed by the Ministry of the Interior. They supported livelihoods in Senegal and Jordan, respectively, for more than USD 1 million each.28 Similar projects were implemented in the humanitarian assistance of the MFA in Jordan, Lebanon and the Sahel.

Czechia also supports trade and private sector development in partner countries through its Aid for Trade Programme and through technical assistance from the Ministry of Finance. The Aid for Trade Programme supports developing countries’ trade performance and integration into the world economy29 and includes technical support to associations of SMEs in partner countries. In addition, the Ministry of Finance has a small programme to provide technical assistance to finance departments in developing countries. It targets the field of public finance and regulation of financial markets, which can indirectly promote local private sector development.

However, most instruments managed by the MFA primarily focus on Czech companies, leading to a high level of tied aid. All instruments managed by the MFA and CzDA aimed at leveraging the private sector, such as B2B grants, the Czech UNDP-partnership and NDB guarantees, are primarily focused on Czech companies and sometimes their partners in developing countries. This is in line with the 2022 government programme that clearly states that development co-operation should support both partner countries and Czech companies (Government of the Czech Republic, 2022[1]). The share of untied ODA under the DAC recommendation on Untying has increased since the last peer review from 32% in 2014 to 58% in 2021. However, it remains below the DAC average and Czechia’s commitment to fully untie ODA in sectors and countries covered by the DAC recommendation.30

Czechia could make more efforts to open up tenders to international bidders. There are mechanisms to contract with local suppliers, but these are generally small contracts. The “tied financial donations” stabilisation instrument created during the COVID-19 pandemic allows recipients to select suppliers from a list, but in practice only Czech suppliers have been selected. Its volume has surpassed the procurement tenders managed by CzDA. While CzDA tenders published on the tender platform are de jure untied, processes make it difficult for non-Czech companies to participate (e.g. tenders published only in Czech). Czechia has not yet made ex ante notifications of untied tenders on the Untied Aid Public Bulletin Board. Meanwhile, its ex post contract awards reporting shows it has awarded five contracts above the EUR 1 million ex ante notification threshold (= USD 1.05 million in 2022) since 2018. Notifying ex-ante all tenders above EUR 1 million in one or more of the languages customarily used in international trade would effectively allow international competition and ensure best value for money for development co-operation projects.

Untying ODA would increase the cost effectiveness of development co-operation. Czechia needs to ensure it selects the most competitive options for addressing humanitarian and development challenges by fully untying tenders and tied financial donations. For instance, an evaluation of the “Inclusive Social Development and Health Care programme in Cambodia” in 2023 (MFA, 2023[18]) highlighted the high value of Czech equipment delivered to Cambodian hospitals but noted it was not adapted to actual needs.31 In addition, evidence has shown that tied ODA can increase project costs by as much as 15-30% (Clay, 2009[23]). Untying ODA, on the other hand, frees the recipient to procure goods and services from virtually any country, thus avoiding unnecessary costs. As Czechia has the ambition to use its NDB to provide concessional loans to municipalities, complying with the Untying commitment will become even more critical.32 More Czech companies are successful at international level, notably in the health and water sector. Consequently, the private sector might be increasingly ready to compete on open tenders, including those funded by other development co‑operation providers, and/or to rely on export credits and commercial financing. This is an additional argument for untying ODA. Finally, Czechia may develop linkages between NDB, Czech Export Guarantee and Insurance Company (EGAP) and Czech Export Bank (ČEB) to support development projects. If so, it will have to ensure these projects are in line with the Recommendation on Untying ODA [OECD/LEGAL/5015] and abide by the tied aid disciplines requirements of the Arrangement on officially supported export credits (OECD, 2022[24]).