This chapter reviews Greece’s approach to delivering in partner countries and through partnerships to determine whether this is in line with the principles of effective development co-operation. The Directorate General of International Development Cooperation-Hellenic Aid has not maintained its network of partners during the recent period of reduced activities. However, civil society organisations (CSOs), academics and the private sector are keen to engage in a dialogue on the future direction of Greece’s development co-operation, and the partnerships that could deliver this. Once Greece resumes country-level engagement, it should develop country strategies in close consultation with its key partner countries. The development impact of Greece’s scholarship programme needs to be determined.

OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Greece 2019

Chapter 5. Greece’s delivery modalities and partnerships

Abstract

Partnering

Peer review indicator: The member has effective partnerships in support of development goals with a range of actors, recognising the different and complementary roles of all actors

The Directorate General of International Development Cooperation-Hellenic Aid of the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs has not maintained its network of partners during the recent period of reduced activities. However, civil society organisations (CSOs), academics and the private sector are keen to engage in a dialogue on the future direction of Greece’s development co-operation, and the partnerships that could deliver this. Through its response to the migration crisis, Greece has gained valuable experience on joint approaches, which could serve as a model for development co‑operation.

Results-oriented partnerships can help deliver future development co-operation

The current context has had a significant impact on the Greek Government’s ability to partner with a range of actors in its development co-operation. Country-level engagements have halted; aid is delivered through scholarships and in-donor refugee costs, and contributions to multilateral organisations. As the economy recovers and Greece considers stepping up its development co-operation, it needs to determine which delivery modalities and partnerships might best serve its intentions and policy. To establish efficient and effective partnerships, Greece should consider whether:

the partnerships are relevant to global, regional or country-level sustainable development needs, recognising links with other complementary policies, initiatives and processes

programming and budgeting are predictable and flexible, and transaction costs are minimised1

funding is transparent and delivers value for money for the taxpayer, and monitoring focuses on results

joint approaches could suit the intended objective.

In the past, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) were DG Hellenic Aid’s primary partner when implementing its aid programme. Past OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) peer reviews recommended that instead of relying on general calls for proposals, Greece should favour results-oriented partnerships with trusted NGOs, embedded in an approach based on country strategies (OECD, 2013a, 2006).2 The recent domestic experiences of NGOs provide a valuable basis for building such results-oriented partnerships: with fewer opportunities to work abroad, many development NGOs started supporting the response to the refugee crisis or helping vulnerable Greeks weather the economic crisis.

Greece collaborated flexibly with partners in responding to the migration crisis

Greece has made good use of European Union instruments and policies to respond to the migration crisis. This experience can provide valuable insights on joint approaches. Greece’s interaction with the European Commission’s Structural Reform Support Service and Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO) has allowed it to build progressively a stable system for managing migration, both in the island hotspots and on the mainland.

Greece’s geographic location makes it a key entry point to the European Union; hence, the recent migration crisis hit the country hard. Greece’s first priority was to save and protect lives. It engaged its coastguard, police and army to manage shelter, food and healthcare, complemented significantly by CSOs and the Greek population’s solidarity. The Greek response is guided by the vision of creating safe pathways for migration and strengthening solidarity with host countries. Greece has managed to change its legislation to provide the appropriate tools for addressing the migration crisis. For example, it grants asylum seekers access to basic services and education, ensuring good prospects for successful integration in Greek society (Box 5.1).

However, managing the inflow of migrants remains a challenge. At the beginning of the migration crisis, the European Union’s Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO) quickly helped Greece cope with the cost by directly funding humanitarian partners, including the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which co-manages the main refugee reception programme with the Greek Government (UNHCR, 2018). As the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs (DG HOME) gradually takes over the European Union’s support to Greece in managing migration, the use of national financial and administrative systems will increase. This transition period represents a major risk to the provision of services to refugees by Greek NGOs and municipalities, which are managing the aid to asylum seekers, and may hamper the effectiveness and efficiency of Greece’s response. To manage this transition effectively, Greece will have to adjust its administrative processes swiftly, notably to speed up disbursements and ensure service continuity.

Box 5.1. Greece quickly developed mechanisms for initial reception and integration of refugees

In 2015, 84% of all illegal border crossings into the European Union took place in Greece (Frontex, 2015). During the first weeks of the emergency phase, Greece relied on its own security apparatus, complemented by the efforts of local municipalities, CSOs and the Greek population. The magnitude of the influx rapidly exceeded Greece’s already stretched capacity to manage the security, legal and humanitarian aspects of the migration flow.

As most migrants arriving in Greece did not apply for asylum there, the Greek Government emphasised the European dimension of the crisis; it asked for European solidarity, and the deployment of existing tools and emergency funds (Migration Policy Centre, 2015). As a result, over USD 1.44 billion in EU funding has been allocated to Greece to support migration management since the beginning of 2015, including USD 435.9 million in emergency assistance and over USD 488 million to cover projects under the EU Emergency Support Instrument (European Commission, 2018). In 2016, the Greek Government created a dedicated Ministry of Migration Policy, which is responsible for designing and managing Greece’s overall immigration policy, as well as migrant reception and identification. The activation of the EU-Turkey Statement in March 2016 (European Council, 2016) curbed the migration flow significantly.

At the height of the migration influx in 2015, Greece provided shelter to 857 000 migrants (European Asylum Support Office, 2017). Because the migration pattern is mixed, with people coming from countries in conflict and from countries that are not (International Organization for Migration [IOM], 2017), the identification and asylum-granting process in the Greek islands is very long. By mid-2018, Greece was still hosting 65 000 persons with refugee profile, including 17 000 still waiting on the islands.

Since the early days of the crisis and up until mid-2018, Greece has adapted its domestic policies to create the conditions for peaceful co-existence between refugees, asylum seekers and the Greek population. Once they have arrived on the mainland, refugees can access the Emergency Support to Integration and Accommodation programme funded by the European Union (UNHCR, 2018), which provides them with shelter and financial support (ranging from USD 101.50 to USD 620 per month depending on family composition). They receive a social security number, which offers them access to healthcare, education, Greek language courses, free transportation and the labour market. Greece focuses on access to education, integrating asylum seekers’ children into regular Greek classes in a bid to spare children from experiencing a long gap without formal education, which would create a lost generation of uneducated youth in Europe. Those measures are good examples of policies carefully translated into action.

Sources: European Asylum Support Office (2017), “Operating plan agreed by EASO and Greece”, European Asylum Support Office, Valletta Harbour and Athens, https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Greece%20OP%202018-13-12-2017.pdf; European Commission (2018), “EU-Turkey Statement – Two Years On”, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20180314_eu-turkey-two-years-on_en.pdf; European Council (2016), “EU-Turkey Statement”, European Council, Brussels, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/; Frontex (2015), Risk Analysis for 2016, https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Annula_Risk_Analysis_2016.pdf; IOM (2017), “Migration flows to Europe 2017 overview”,

https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2017_Overview_Arrivals_to_Europe.pdf;

Migration Policy Centre (2015), http://www.migrationpolicycentre.eu/greece/; UNHCR (2018), “ESTIA: A new chapter in the lives of refugees in Greece”, http://estia.unhcr.gr/en/home/.

Country-level engagement

Peer review indicator: The member’s engagement in partner countries is consistent with its domestic and international commitments, including those specific to fragile states

Once Greece resumes country-level engagement, it should develop country strategies in close consultation with its key partner countries. The development impact of Greece’s scholarship programme needs to be determined.

Greece should base its future country-level engagement on country strategies

The 2006 and 2011 DAC peer reviews recommended that Greece base its country-level engagement on country strategies (OECD, 2006, 2013). Due to the suspension of bilateral programmes in 2011, Greece has not developed country strategies. When it resumes its country engagement in the future, Greece should consider strategies that:

apply the principles of ownership and mutual accountability

apply the principles of development effectiveness to which Greece has subscribed

rest on contextual analysis, using an appropriate mix of aid-delivery instruments and partners in response to partner countries’ changing needs and capacity

are transparent about conditions (if any).

Greece’s technical co-operation responds directly and flexibly to countries’ demands, and mostly focuses on policing and firefighting (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018).3 Although small in size during the reviewed period, it is valued by its immediate neighbours and is a good basis for structuring a future bilateral programme. Furthermore, Greece has signed a number of bilateral agreements on topics including securing sports events; fisheries and aquaculture; the environment and climate change adaptation; tourism; scientific exchange; diplomatic training; and EU accession processes.

The impact of Greece’s scholarship programme is uncertain

Although they have decreased over the years, scholarships remain Greece’s most important bilateral activity, along with support to refugees. An integrated and coherent scholarship programme could be an important component of future country strategies. The current programmes are not aligned with partner countries’ priorities, and partner countries are not involved in selecting students and fields of study.

In 2002, the DAC recommended that Greece reduce the number of scholarship schemes, and streamline selection procedures and award conditions (OECD, 2003). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs publishes a voluntary list of 25 priority countries for the scholarship programmes; this is a welcome step towards greater coherence. Nevertheless, the number of programmes is still high, each acting independently, without a coherent approach.4

Greece has taken initial steps to evaluate the impact of its scholarships on capacity building in developing countries, as recommended in the 2011 DAC peer review (OECD, 2013). Following approval by the Minister of Foreign Affairs in July 2018 of a strategy paper on scholarships, an inter-ministerial meeting has agreed a road-map to implement this strategy.

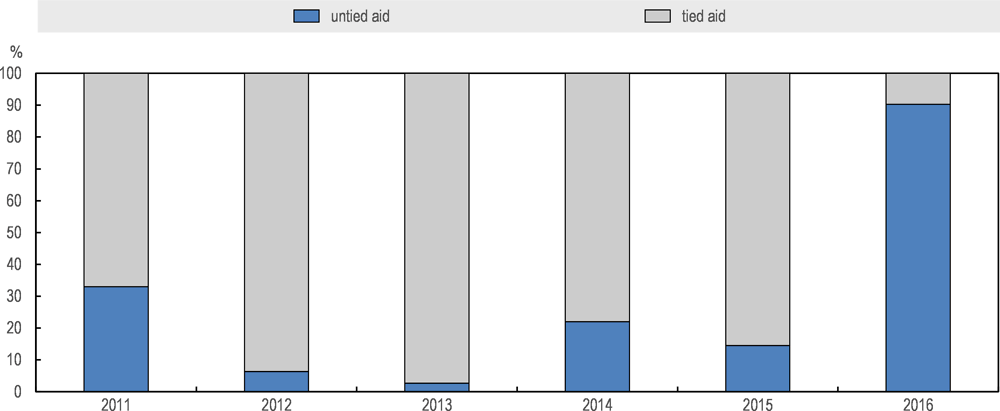

Greece’s bilateral co-operation is highly tied

Greece’s aid is traditionally highly tied. Since 2011, tied aid has comprised at least 67% of bilateral official development assistance (ODA), except for 2016, where only 9.7% of bilateral ODA was tied (Figure 5.1). The high percentage of tied aid is a result of Greece’s focus on scholarships and imputed student costs, which the DAC defines as tied aid. Their sharp reduction, from USD 10 million in 2015 to USD 2 million in 2016, explains the increase in untied aid in 2016 (Annex B, Table B.2).

Figure 5.1. Greece's untied aid status, 2011-16

Note: Excluding administrative costs and in-donor refugee costs.

Sources: OECD (forthcoming), Development Co-operation Report 2018: Joining Forces to Leave No One Behind; OECD (2017), Development Co-operation Report 2017: Data for Development, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2017-en; OECD (2016), Development Co-operation Report 2016: The Sustainable Development Goals as Business Opportunities, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2016-en; OECD (2015), Development Co-operation Report 2015: Making Partnerships Effective Coalitions for Action, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2015-en; OECD (2014), Development Co-operation Report 2014: Mobilising Resources for Sustainable Development, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2014-en; OECD (2013b), Development Co‑operation Report 2013: Ending Poverty, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2013-en.

References

Government sources

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2018), “Memorandum submitted by the Greek Authorities to the Development Assistance Committee/DAC of the OECD”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Athens (unpublished).

Other sources

EASO (2017), “Operating plan agreed by EASO and Greece”, European Asylum Support Office, Valletta Harbour and Athens, https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Greece%20OP%202018-13-12-2017.pdf.

European Commission (2018), “EU-Turkey Statement – Two Years On”, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20180314_eu-turkey-two-years-on_en.pdf.

Frontex (2015), Risk Analysis for 2016, European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union, Warsaw, https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Annula_Risk_Analysis_2016.pdf.

IOM (2017), “Migration flows to Europe 2017 overview”, International Organization for Migration, Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2017_Overview_Arrivals_to_Europe.pdf.

Migration Policy Centre (2015), “Greece”, webpage, http://www.migrationpolicycentre.eu/greece/ (accessed 10 July 2018). OECD (forthcoming), Development Co-operation Report 2018: Joining Forces to Leave No One Behind, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2017), Development Co-operation Report 2017: Data for Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2017-en.

OECD (2016), Development Co-operation Report 2016: The Sustainable Development Goals as Business Opportunities, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2016-en.

OECD (2015), Development Co-operation Report 2015: Making Partnerships Effective Coalitions for Action, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2015-en.

OECD (2014), Development Co-operation Report 2014: Mobilising Resources for Sustainable Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2014-en.

OECD (2013a), Development Co-operation Report 2013: Ending Poverty, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2013-en.

OECD (2013b), OECD Development Assistance Peer Reviews: Greece 2011, OECD Development Assistance Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264117112-en.

OECD (2006), "DAC Peer Review of Greece", OECD Journal on Development, Vol. 7/4, OECD, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/journal_dev-v7-art40-en.

OECD (2003), "Development Co-operation Review of Greece", OECD Journal on Development, Vol. 3/2, OECD, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/journal_dev-v3-art12-en.

UNHCR (2018), “ESTIA –A new chapter in the lives of refugees in Greece”, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Greece website, http://estia.unhcr.gr/en/home/ (accessed 9 August 2018).

Notes

← 1. Greece could complement its annual budget planning with an indicative multi-year plan.

← 2. Greece’s general call for proposals tended to disperse funds too widely, limiting the possibility of a strategic approach and leading to “a supply-driven system instead of a partner country demand-led approach which would foster ownership” (OECD, 2006).

← 3. In 2015, the Hellenic Police (Ministry of Interior) trained Albanian, Sudanese and Ukrainian police officers on topics including traffic legislation; combating human trafficking and drug trafficking; managing evidence and crime data; and border controls. The Hellenic Fire Service (Ministry of Citizen Protection) helped fight forest fires in Albania in 2012 and donated firefighting materials to the country in 2014. In 2012, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport provided assistance and technical support for evaluating and monitoring the reconstruction of a hospital in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and a road project in Albania.

← 4. Five ministries and one state foundation offer scholarship programmes for foreign students: the Ministry of Education Research and Religious Affairs; the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Insular Policy; the Ministry of Health; the Ministry of Rural Development and Food; and the State Scholarship Foundation.