This report presents the findings of the 2024 development co-operation peer review of the Republic of Korea (hereafter Korea) and includes the relevant peer review recommendations approved by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC). In accordance with the 2021 methodology, it does not cover all components identified in the peer review analytical framework. The report focuses on five areas of Korea’s development co-operation that were identified in consultation with Korea’s partners and Korean government representatives. It first analyses Korea’s overall development co-operation and humanitarian assistance architecture and systems from the perspective of Korea as a global development actor in pursuit of policy coherence. It then explores the extent to which Korea is fit for purpose to achieve its ambition and implement its expanding development co-operation programme. The report further examines how Korea manages for sustainable development results and impact, its human resource capacity, and how it could incentivise additional financial resources to meet global challenges. In each of these areas, the report identifies Korea’s strengths and challenges, the elements enabling Korea’s achievements, and the opportunities and risks that lie ahead.

OECD Development Co‑operation Peer Reviews: Korea 2024

Findings

Abstract

Context

Political context

The Republic of Korea (Korea) is a presidential republic. The president, elected for a single five-year term, has considerable executive powers, and appoints both the prime minister and the State Council or cabinet.

Two main political parties, the liberal Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) and the ruling conservative People Power Party (PPP), dominate the political landscape. Yoon Suk Yeol, the current president from the PPP, was elected in 2022. Korea has a unicameral legislature, the 300-member National Assembly whose members are elected to terms of four years. The DPK currently controls the National Assembly. The next legislative elections are scheduled for 10 April 2024.

The Yoon Suk Yeol administration presented a vision of a “global pivotal state” contributing to freedom, peace, and prosperity as its foreign policy. The vision reflects Korea’s commitment to assume a more active role advancing freedom, peace, and prosperity around the world.

Economic context

In 2023, Korea ranked as 13th largest among the world's economic powers and the fourth largest in Asia. It is known for its rapid economic transformation, which catapulted it from one of the poorest countries in the world in the 1950s to the high-income country it is today. Korea’s trajectory from official development assistance (ODA) recipient to donor is a powerful example that developing countries aspire to replicate.

Gross domestic product growth is projected at 1.5% in 2023, down from 2.6% in 2022, and is expected to increase to 2.1% in 2024. The National Assembly approved a more fiscally restrained 2023 budget that reflected the new government’s priority to address rising debt dependence.

Against the backdrop of a rapidly ageing population, fiscal consolidation is likely to continue. The proposed ODA budget for 2024 was for a 44% increase and 31.1% was finally approved. This increase will raise pressure on limited human resources since civil service headcounts are unlikely to increase at the same rate (OECD, 2023, pp. 186-188[1]).

At the same time, the overall 2024 budget approved a 2.8% increase over the previous budget – the smallest increase in government spending in almost two decades (Kim, 2023[2]).

Development co-operation in Korea

Development co-operation in Korea has enjoyed broad support across party lines, with the Korean government and citizens eager to share their own development experience with other countries; responses to a recent survey, however, indicate that public support has been declining and hovered at just under 80% in 2022 (Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, 2023[3]). Korea joined the OECD in 1996 and the DAC in 2010. Fourteen years after joining the DAC, Korea seeks to assume greater responsibility in international development co-operation efforts.

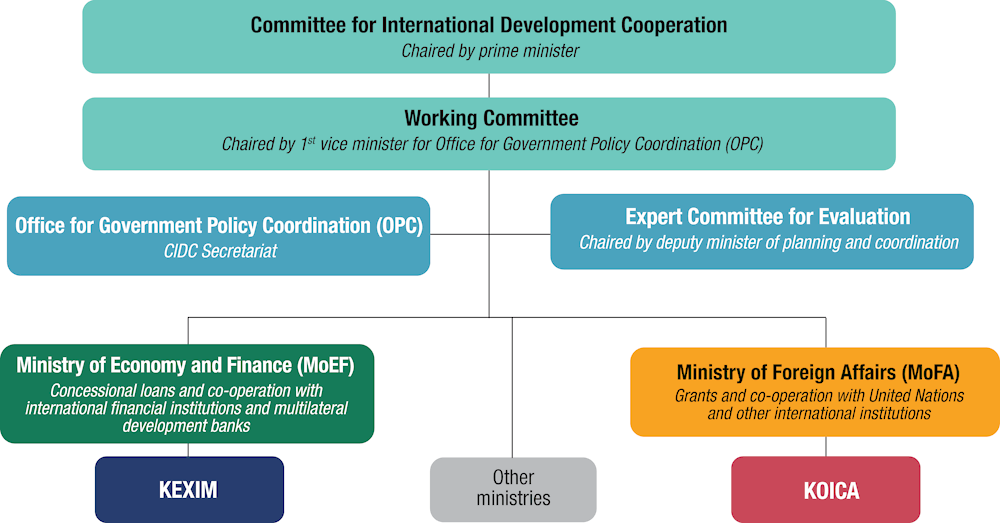

Since the 2018 OECD DAC Peer Review, Korea has laid the foundations of a strong institutional and policy architecture via the 2020 revision of the Framework Act on International Development Cooperation (Framework Act), which strengthens the integration and co-ordination function of the Committee for International Development Cooperation (CIDC) and expands its secretariat, the Office for International Development Cooperation. The CIDC has 29 members, among them the prime minister, who serves as the chair, and ministers from 14 ministries, heads of the Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) and the Export-Import Bank of Korea (KEXIM), and 12 civilian experts. The CIDC, as the co-ordinating organisation, works to enhance development effectiveness and policy coherence through better co-ordination across ministries.

The 3rd Mid-term Strategy for International Development Cooperation for 2021-25 (3rd Mid-term Strategy) aims to realise global values and mutual development through co-operation and solidarity; through inclusive, co-prosperous and innovative ODA; and via partnerships (Government of Korea, 2021[4]). At the same time, President Yoon’s strategic plan for ODA sets Korea on a course to become the world’s tenth-largest donor with larger-scale projects, a Korean brand, and a more developed ecosystem of private and civil society actors to complement the public administration’s efforts to scale up ODA and assume more responsibility in the international community (Korea Office for Development Cooperation, 2022[5]).

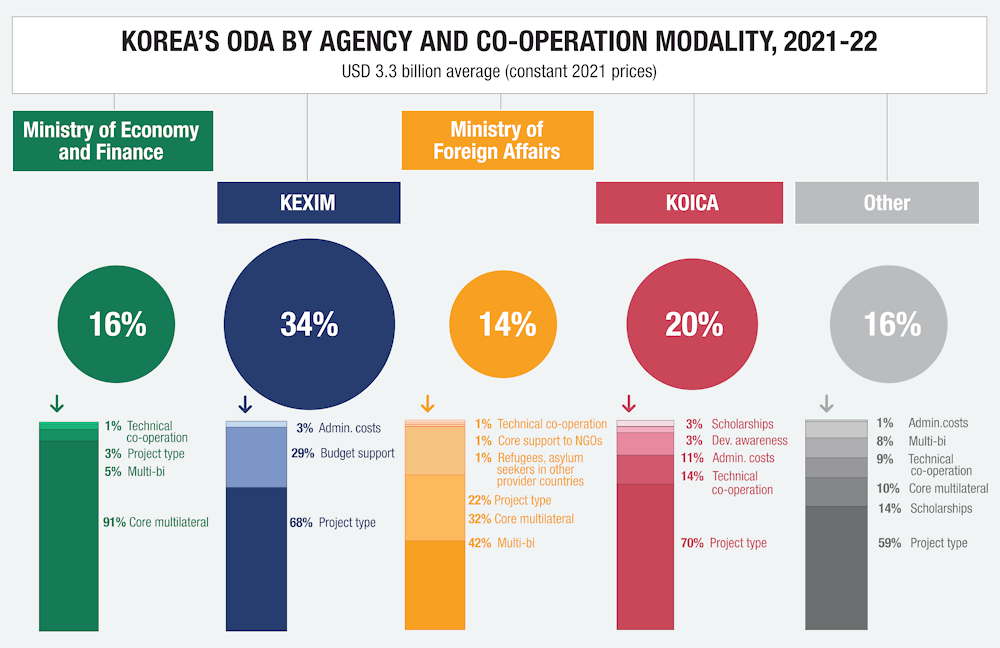

As supervising ministries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) and the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MoEF) are in charge, respectively, of the provision of grants and concessional loans. The MoFA supervises grant projects delivered by implementing agencies, mainly KOICA. The MoEF supervises KEXIM, which delivers loan programmes through the Economic Development Cooperation Fund (EDCF) (Figure 1). Most of Korea’s ODA budget is managed by the MoFA and MoEF and their respective implementing agencies, with the rest of this budget spread among 41 other government departments and institutions.1

The strengthened Expert Committee for Evaluation under the CIDC has been responsible for the introduction of a performance-based approach across Korea’s ODA through amendment of the Framework Act. The committee has a mandate to receive and review self-evaluations for programmes across the 45 ministries and agencies.

Figure 1. Architecture of Korea’s development co-operation system

Source: Government of Korea (2023[6]), ODA Korea - Organization: K-ODA System, https://www.odakorea.go.kr/eng/cont/ContShow?cont_seq=33.

Korea as a global development actor in pursuit of policy coherence

In the pursuit of its ambition to become a global pivotal state, Korea could leverage its enhanced commitment to international co-operation to strengthen its influence

In the Yoon administration’s conception of a global pivotal state, Korea will expand networks and co-operation with like-minded states that share its identity, values and strategic interests. The idea is to restore and maintain relationships for stability in the Indo-Pacific region (Chung, 2023[7]) while also expanding the networks to other parts of the world such as Central Asia and Africa. Extended to Korea’s development co-operation policy, this translates to providing co-operation to promote liberal democratic values; expanding ODA volumes and contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by carrying out high-quality development co-operation in line with that of other DAC members; strengthening global solidarity together with private sector actors; prioritising national diplomatic, economic and security interests; and playing leading roles in sectors where Korea has a comparative advantage (Korea Office for Development Cooperation, 2022[5]).

Korea’s growing presence as a donor in its partner countries is an opportunity for it to take the lead in global initiatives. Partner countries value the breadth of technical assistance and knowledge exchange provided by Korea’s diverse development actors, including through the knowledge sharing (KSP) and Development Experience Exchange (DEEP) programmes. While these activities often focus on the transfer of technical knowledge and skills in specific sectors, their impact could be amplified if they were better linked to discussions about the wider systemic context of a country and the international development co-operation landscape. Korea could heighten its impact by strengthening different partnerships. Lowering the turnover of staff who work as focal points for these partnerships could help Korea articulate a long-term strategic approach to global agendas and initiatives (see discussion of human resource capacity and the development ecosystem). Moreover, close cultural ties and diverse interactions (people-to-people exchanges and interactions in academia and the public sector) between Korea and partner countries provide a wide array of entry points that Korea could more consciously capitalise on in its development co-operation policies.

Korea has an opportunity to develop more strategic partnerships with several multilateral partners and expand its influence. A growing number of line ministries and agencies engage with multilateral organisations, including through high-level exchanges with senior executives. Often the different ministries and agencies have overlapping interests, which can interfere with the effectiveness of their communication with multilateral organisations. In interviews, multilateral partners remarked that Korea’s influence on their strategic direction and policies through their boards is relatively small relative to the size of its financial contributions. The CIDC could identify what Korea wants to achieve with key multilateral partners and help co-ordinate messaging among the ministries and agencies to increase Korea’s collective influence on key priorities such as those identified in the 3rd Mid-term Strategy. Lead ministries plan to intensify consultations with key multilateral partners to this end.

Building on its legacy from Busan and important financial support of development effectiveness at the global level, Korea can step up its engagement in donor co-ordination platforms, assuming leadership roles in strategic policy dialogue. By joining forces with other bilateral and multilateral donors in priority sectors, Korea could contribute to and support institutional and governance reforms in partner countries to enhance the effectiveness, impact and sustainability of Korea’s own bilateral development co-operation efforts. In Uzbekistan, Korea participates in the newly established donor co-ordination platforms but could be more active and visible, for example by leading working groups in sectors such as health and education where Korea has a significant presence. Such leadership may require adjusting the human resource configuration in partner countries (see discussion of human resource capacity and the development ecosystem). In the new Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC) work programme, Korea could also play a more prominent role in mobilising country missions and partners for the GPEDC monitoring.

Engaging the private sector as a partner in achieving sustainable development rather than as implementer of ODA projects is one avenue to leverage Korea’s influence for greater development impact (see discussion on incentivising additional financial resources to meet global challenges). In many partner countries, Korean private companies have a sizeable presence as investors and trade partners, pioneering investments in sectors with great potential for development impact such as digital connectivity and manufacturing. On the Center for Global Development’s Commitment to Development Index, Korea ranks in the top ten on bilateral investment agreements, which means that it includes fewer clauses that protect Korean investors at the expense of the development policy space of their hosts than do most of the other 40 reviewed countries2 (Center for Global Development, 2023[8]). Korea is among the ten largest aid for trade donors, having committed USD 1.7 billion (41.5% of its bilateral allocable aid) to promote aid for trade and to improve developing countries’ trade performance and integration into the world economy in 2021. There is room to apply a stronger SDG and development lens to trade and foreign investment policies overall. For example, Korea has somewhat restrictive services trade policies in certain sectors and ranks last on the average tariff rates (when weighted inversely by the incomes of its trading partners)3 (Center for Global Development, 2023[9]).

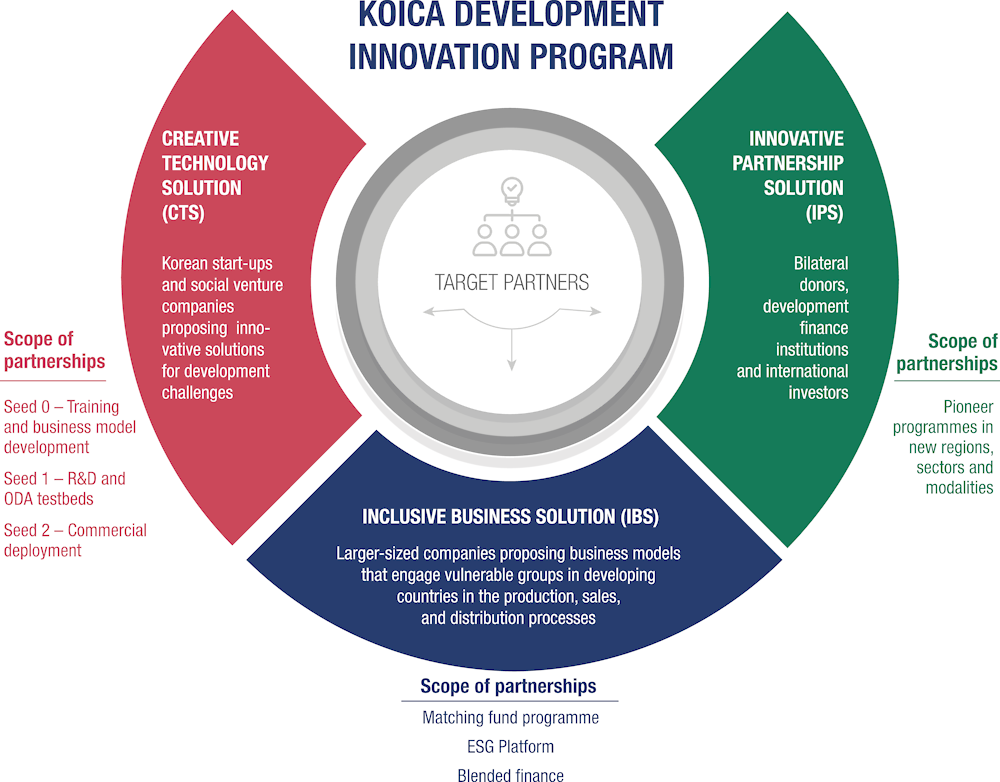

KOICA’s new environmental, social and governance (ESG) initiative, through which KOICA joins with Korean conglomerates to co-create and identify ESG project opportunities in developing countries, sets a promising example (Invest Korea, 2023[10]). Based on this new approach, Korea’s development actors shape and define corporate ESG visions and agendas, bringing the development perspective into corporate decision making in Korea (see discussion of incentivising additional financial resources to meet global challenges). This strengthened partnership with the private sector can serve as a mechanism whereby Korean private investors raise their concerns and suggestions about the business enabling environment in partner countries (Government of Korea, 2022[11]). In line with the new OECD Recommendation on the Role of Government in Promoting Responsible Business Conduct (RBC) (OECD, 2022[12]), there is likely to be an opportunity to link Korea’s RBC agenda with its development co-operation policies. One option would be to strengthen the cross-agency engagement of the National Contact Point for the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, hosted by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. Korean government authorities and businesses could also be more active in promoting dialogue between local authorities and the local and international business community in the partner country.

While an institutional framework governs policy coherence for sustainable development, the framework is not yet fully operational

There has been progress against the 2018 Peer Review recommendation to integrate SDGs into Korea’s development co-operation more systematically. The 3rd Mid-term Strategy is structured along the five Ps of the 2030 Agenda (People, Prosperity, Planet, Peace and Partnerships). SDGs are also incorporated into Korea’s country partnership strategies. Since 2016, the SDG targets associated with individual ODA projects must be specified in the annual implementation plan for grants. For this purpose, Korea developed the Performance Indicator Model, which is based on the SDGs and used to help define indicators for development co-operation projects during the project planning stage. The guidelines for drafting the implementation plan for grant projects require the use of these performance indicators. Since 2019, the model has also been incorporated in self-evaluation guidelines.

The current institutional framework governing policy coherence for sustainable development (PCSD) considers transboundary effects on developing countries. PCSD is governed by the 2022 Framework Act on Sustainable Development4 and its enforcement decree, which contain cross-government commitments to achieve sustainable development. A clause in the Act stipulates that the economic development of Korea should not come at the expense of the environment and social justice of other countries, thus providing a strong foundation for the National Council on Sustainable Development to ensure that government policies consider transboundary effects. The current strategy for sustainable development, the Fourth Basic Plan, serves as the basic platform for integrated policy action related to sustainable development. As the lead institution for PCSD, the National Council on Sustainable Development is mandated to evaluate national sustainability every two years. Previously under the Ministry of Environment, the Council will be under the direct oversight of the President's office, reflecting the willingness to attach greater importance to PCSD. However, the Council is yet to be established.

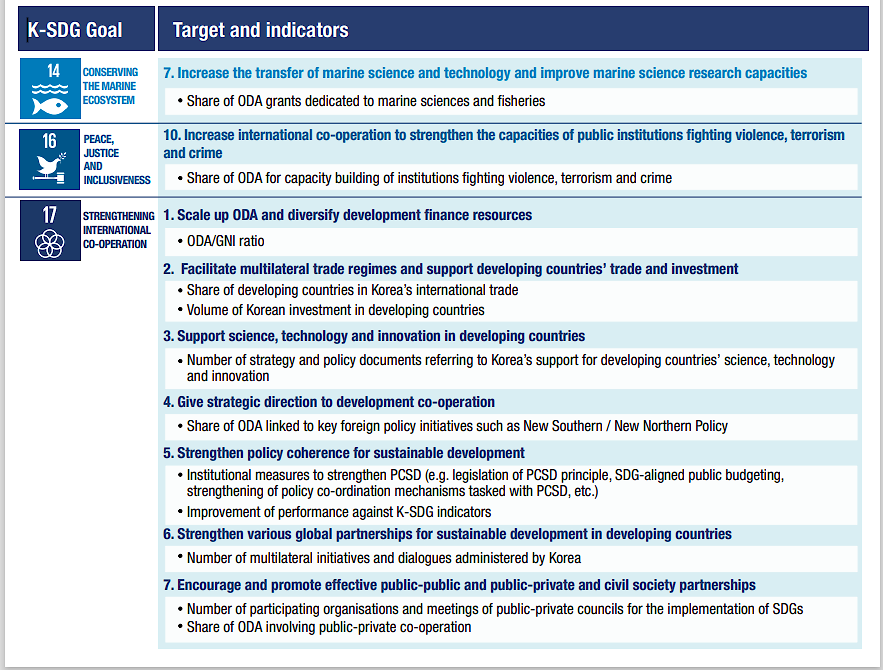

There is limited reference in ministries’ strategies and plans to the effects of domestic policies on the social, economic and environmental sphere in developing countries. Setting the national SDG goals, referred to as K-SDGs, was largely a bottom-up process, and more than half (57%) of the 119 targets address societal concerns specific to Korean circumstances5 (OECD, 2023[13]). However, these goals are not clearly reflected in the strategies and action plans of individual ministries6 (Government of Korea, 2020[14]), and Korea does not yet monitor whether and how K-SDGs are reflected at each stage of the policy process from planning to execution and evaluation. Research on trade and development and case studies on the United Kingdom and the Netherlands related to PCSD were commissioned in 2018 and 2021. The Fourth Basic Plan includes ODA as a policy area under SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals) alongside the promotion of a multilateral trade regime and technological innovation in developing countries. Other K-SDGs – including Goal 16 (peace, justice and inclusiveness) and Goal 14 (conserving the marine ecosystem) – also include ODA-related targets (Figure 2). Korea’s commitment to knowledge creation through investment in research and development (R&D) in science and technology for developing countries is a further example of its positive contribution beyond ODA (Center for Global Development, 2023[8]).

Figure 2. Korea’s Fourth Basic Plan for Sustainable Development includes a handful of K-SDG targets related to international activities

Source: Authors’ illustration based on Government of Korea (2020[14]), 제4차 지속가능발전 기본계획2021-2040 (Fourth Basic Plan for Sustainable Development 2021-40).

The CIDC is well placed to bring a development perspective to policy deliberations and raise awareness about areas of incoherence in relation to the transboundary effects of domestic policies on developing countries.7 It has a mandate to co-ordinate, deliberate on and decide policies related to international development co-operation (Art. 7.6 of the Framework Act ) and formulates mid-term strategies that set the direction for Korea’s development co-operation policies every five years based on an analysis of the relevant domestic and overseas environment for international development co-operation (Art. 11). These strategies could specifically include an analysis of the effects of Korea’s domestic policies on development partners, particularly those overseen by KOICA, KEXIM, and the other 14 ministries and agencies represented on the CIDC. The analysis could also feed into the work of the National Council on Sustainable Development, which monitors Korea’s overall progress on sustainable development.

While development objectives could be more systematically integrated into Korea’s domestic and international policies, some efforts are already being made at the local level in partner countries to align ODA with other policy areas. In Uzbekistan, Korea has begun to explore synergies across policy areas, for example between ODA support for vocational training and migration policies. Uzbekistan is a partner country to Korea’s Employment Permit Scheme (EPS), the largest temporary foreign worker programme operating on a bilateral basis among OECD countries. The EPS matches Korean small and medium-size employers with low-skilled workers from partner countries, accompanying them through their application process, selection, training and stay in Korea for up to three years (OECD, 2019[15]). In Uzbekistan, the EPS provides employment and skills training opportunities for a growing labour force that cannot be fully absorbed domestically. At the same time, Korea prioritises technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in its development co-operation with Uzbekistan to help address the high youth unemployment rate (14%), including through support for the implementation of a national skills certification system. As part of the support, KOICA also set up TVET centres, one of which trains and prepares workers to participate in the EPS (Box 2). Building on the linkages between the EPS and ODA, Korea could further explore ways to facilitate the reintegration of EPS participants after their return to Uzbekistan.8

The strong momentum for global climate action has led to a reinforcement of climate commitments and more greening of ODA

Korea has stepped up its climate ambitions and made efforts to institutionalise policy coherence for carbon neutrality. In December 2021, the government submitted its updated nationally determined contribution (NDC) (Government of Korea, 2021[16]) with the aim of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. A government-wide, cross-sectoral 2050 Carbon Neutral Strategy formulated in December 2020 established the Presidential Committee on 2050 Carbon Neutrality to lead policy efforts. Under the leadership of this committee, Korea introduced more detailed sectoral planning in the form of green growth promotion and technology innovation strategies that aim to achieve the 2030 NDC and the 2050 carbon neutrality target.

Achieving the emission reduction targets is seen as challenging, however. There are concerns that a rapid reduction of emissions in line with Korea’s international pledges could be difficult to realise in light of the policy measures currently in place (Climate Action Tracker, 2023[17]), although the current administration’s policy focus on supporting nuclear electricity generation in addition to renewables may improve the chances of achieving targets. Korea is the fifth-largest greenhouse gas emitter among OECD countries. Its industry structure is tilted towards high-emission industries such as iron and steel, cement, and petrochemicals. Further, the electricity market is structured to favour fossil fuels over renewable energy and enable the majority state-owned utility company KEPCO to continue fossil fuel subsidies. Concerns have been raised that such a rapid pace of emission reductions will put too high a burden on business in the emissions-intensive Korean economy as the country’s emissions peaked more recently than in most OECD countries (OECD, 2022[18]).

Recently, Korea has put greater emphasis on providing climate finance and greening ODA as a central pillar of its external climate action.9 Korea made a USD 300 million pledge to the second replenishment of the Green Climate Fund (GCF), a 50% increase over its pledge to the previous replenishment. Its 2021 Green New Deal ODA Strategy elaborates Korea’s approach to greening ODA10 and lays out a plan to provide more strategic and systematic support for partner countries’ green transitions, focusing on areas where Korean technologies are more advanced such as batteries, hydrogen, water resources, sanitation, electric transmission and distribution. The strategy set a target of increasing the share of green ODA from its level of 20% (2015-19) to the DAC average by 2025 (Government of Korea, 2021[19]).

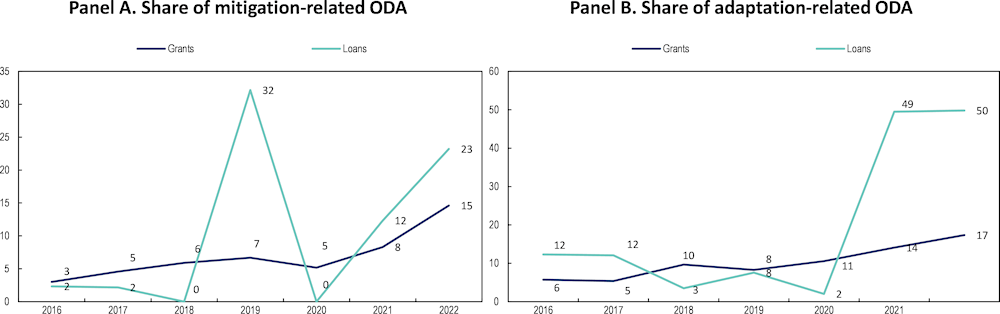

The recent increase in the share of climate-related ODA is a positive signal. As a result of Korea’s renewed commitment to greening ODA, the share of its climate-related ODA exceeded the average level of DAC members and reached 35% in line with the Green New Deal ODA Strategy. This is largely due to an increase in loans targeting climate adaptation, which jumped from an 8% share of total bilateral ODA in 2019 to a 50% share in 2022 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The share of climate-related ODA rose significantly in 2021, driven mainly by an increase in climate adaptation loans

Note: Percentage shares are calculated based on ODA commitments.

Source: Authors’ illustration based on OECD (2023[20]), “Creditor Reporting System: Aid activities”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00061-en.

However, continued efforts will be necessary to maintain Korea’s climate commitment over the long term. Historically, Korea’s track record in climate-related commitments has fluctuated, notably for mitigation-related ODA. After reaching higher levels (an annual average of 6% in 2008-13), when Korea promoted green growth and international climate leadership as a flagship agenda, the share of Korea’s climate mitigation-related ODA declined to an annual average of 2.5% in 2013-17 before increasing to reach peak levels between 2017-22 when it averaged 11%. This increase likely coincides with the adoption of the Green EDCF Strategy in 2021 and introduction of the Green Index. Establishing a legal basis for a strong climate orientation in ODA, for example in the Framework Act, could work to help ensure policy continuity over time with regard to the greening of ODA (Institute for Climate Change Action, 2023[21]). Furthermore, the climate focus could be more prominent in country partnership strategies through the systematic inclusion of climate assessments and linkages with NDCs and national adaptation plans.11

Based on the EDCF’s pilot Climate Change Impact Response Framework, Korea could further complement current efforts to expand climate-related ODA volumes by paying equal attention to the impact and quality of targeting of ODA. While Korea attempts to match climate-related ODA with needs by consulting with partner countries in designing and identifying projects, there is room to adopt a more rigorous approach such as climate-informed results frameworks that guide project design, planning, implementation and evaluation based on a quantitative assessment of climate-related needs and vulnerabilities12 in all ODA projects. The EDCF’s Climate Change Impact Response Framework sets a strong example in this regard (Box 1). Sharing and transferring the EDCF’s approach across Korea’s development co-operation system could contribute to realising the vision of the Green New Deal ODA Strategy to consistently apply criteria across ministries and implementing agencies to guide the classification, screening and monitoring of green ODA projects. The allocation of dedicated financial and human resources will be critical to maintain and operate the EDCF framework in the long term and introduce similar frameworks in other implementing agencies (Export-Import Bank of Korea and Deloitte, 2021[22]) (see discussion of human resource capacity and the development ecosystem).

Box 1. The EDCF’s green strategy and Climate Change Impact Response Framework

In line with Korea’s Green New Deal ODA Strategy, the EDCF formulated the Green EDCF Strategy and the Guideline for Applying the Climate Change Impact Response Framework (Export-Import Bank of Korea and Deloitte, 2021[22]) in 2021.

The framework introduces climate risk assessments for all projects starting from the feasibility study stage. In a preliminary screening, high-emission projects are flagged. The climate risk assessments further consider a project’s exposure to climate change and the nature and extent of the relevant climate hazard as well as climate vulnerability. Based on these risk assessments, projects are categorised as low, medium or high risk.

For medium- to high-risk projects, mitigation measures need to be put in place. The feasibility study must include a list of proposed mitigation measures with an evaluation of their effectiveness and feasibility. The EDCF and the partner country make the final choice jointly based on the priority of the project as well as the capacities and preferences of the partner country.

Moreover, for projects that are classified as climate related, the framework requires the setting of quantifiable performance indicators and goals, which are also integrated into the EDCF’s results framework. Baseline data for the indicators are collected during the feasibility study stage and continuously monitored and evaluated throughout the project cycle.

A key challenge to fully roll out the framework is partner countries’ resistance to the possible cost increases in EDCF loans due to the integration of climate components. Given the relative novelty of the EDCF framework, the policy direction at headquarters level will require both incentives and time before it translates into a stronger climate focus in KEXIM country offices.

Source: Export-Import Bank of Korea and Deloitte, (2021[22]), EDCF 기후변화 영향 대응체계 [EDCF Climate Change Impact Response Framework], https://www.edcfkorea.go.kr/HPHFFE091M01?curPage=1.

Recommendations

1. Korea should implement its 2022 Framework Act on Sustainable Development to strengthen Korea’s policy coherence for sustainable development and:

a. fully operationalise the National Council on Sustainable Development to co-ordinate domestic and international policies and their effects on the sustainable development goals

b. build on the National Council’s mandate to review implementation plans of ministries and consider and address the transboundary effects of domestic policies on developing countries, starting with a few key areas

c. leverage the role of the CIDC to bring a development perspective to inter-ministerial policy deliberations.

2. Korea should strengthen strategic partnerships and dialogue with MDBs, other multilateral partners and bilateral providers beyond the current level of engagement, mainly focused on project support, in order to gain more influence and build trust in line with Korea’s ambition to scale up ODA.

3. Building on the Green ODA Strategy, Korea should integrate climate considerations into development co-operation across all implementing ministries and agencies, including by accelerating efforts to roll out the EDCF Climate Change Impact Response Framework and the KOICA Climate Result Management Framework.

A fit-for-purpose development co-operation system to match Korea’s ambition

Increasing ODA levels and Korea’s influence is likely to require a step change in modalities and approaches

Fourteen years after joining the DAC in 2010, Korea is aligning its national interests and ambitions with global values to assume more responsibility and scale up ODA, as outlined in both its 3rd Mid-term Strategy and President Yoon’s strategic plan for Korea to become the DAC’s tenth-largest bilateral donor. To support these efforts, the Office of International Development Co-operation was created in 2021 under the Prime Minister’s Office for Government Policy Coordination (OPC) and is working to strengthen partnerships within and outside the government.

The 2024 approved ODA budget equivalent to USD 4.8 billion represents a 31.1% increase in ODA, an amount that would exceed 0.25% of GNI (gross national income), although the 3rd Mid-term Strategy does not put forward an ODA-to-GNI target.13 The budget increase marks a turning point for Korea’s development co-operation and, coming amid fiscal tightening across all other budget lines, will test the aid system’s fitness to deliver on such an increase. As set out in the president’s 2022 strategic plan for ODA, ODA volume will scale up through an increase in public funding and diversification of financial resources while Korea will also step up its influence and presence in the multilateral development system, connect or bundle projects to form packages, and implement large-scale programmes for infrastructure development14 (Korea Office for Development Cooperation, 2022[5]). Korea can work to more effectively implement its development co-operation including by exploring new bilateral modalities; expanding existing ones (such as budget support and blended finance); and testing decentralisation efforts by strengthening country office teams and devolving decision-making authority. At the same time, Korea can work to expand its partnerships with multilateral and civil society organisations (CSOs) and seek more cross-government complementarities and efficiency gains (see discussion on incentivising additional development finance to meet global challenges).

Close to two-thirds of bilateral ODA goes to Korea’s 27 priority partner countries. The OPC, operating as the CIDC’s secretariat, recently published country partnership strategies for the 27 priority partner countries that are identified in the 3rd Mid-term Strategy and collectively receive most (61%) of Korea’s bilateral ODA.15 Currently, 37 staff members work in the OPC. As the role of the OPC broadens to include more dialogue with external partners and early planning across a diversity of actors to secure greater impact through larger programmes, including at partner country level, ensuring that it has sufficient and qualified human resources in place to enable it to play a strategic co-ordination role will be paramount (see discussion of human resource capacity and the development ecosystem).

During the COVID-19 pandemic when many programmes and project-type assistance came to a halt, KEXIM (via the EDCF) extended programme- or policy-based loans to channel resources in a timely manner and bridge financing gaps. In this way, Korea was able to somewhat compensate for the uncertainty in ODA execution, which may remain an ongoing concern as the ODA budget increases. Between 2019-21, 14 countries, all but two of them priority partner countries, received budget support through this modality, which does not require the two-year planning period between project proposal and start of implementation (referred to as N-2). Institutionalising policy-based lending as a core business of KEXIM-EDCF could diversify modalities and help smooth year-to-year fluctuations if also accompanied by increased core multilateral contributions (see discussion on Korea as a global development actor) and co-financing with multilateral development banks (MDBs). This could also help Korea’s country dialogue and partnerships evolve over the longer term beyond specific project support.

Korea could consider how to increase its multilateral ODA to absorb spending increases, using its Multilateral International Development Strategy as a basis for decisions (Government of Korea, 2022[23]). To absorb a significant increase in ODA volumes when there is little time to plan for new bilateral ODA spending, many DAC members scale up their multilateral contributions as a way to capitalise on efficiencies. Korea’s 50% planned increase in its contribution to the GCF is an example. As Korea looks to gain more influence in international organisations, it could consider how to increase its relatively low share of multilateral ODA (22% of the total) via strategic partnerships. These partnerships can then serve as a foundation for more pooled funding and co-ordination with other donors as well as co-financing opportunities (see discussion of incentivising additional financial resources).

A more consistent poverty focus and gender mainstreaming would demonstrate Korea’s ambition to continue improving its development co-operation and its commitment to the SDGs

While its ODA programmes do not set out an explicit poverty focus, Korea concentrates its bilateral ODA largely in countries most in need.16 Country partnership strategies typically refer to up to three priority sectors and, with few exceptions do not refer to poverty reduction as a strategic objective. As noted in the 2018 Peer Review, Korea’s concentration on social sectors and economic infrastructure in partner countries demonstrates a strong intent to focus on poverty reduction programmes. However, the 2018 review found no evidence that Korea consistently demonstrates a strong poverty focus in the way it designs and targets its interventions (OECD, 2018[24]). For this reason, Korea would benefit from a clearer theory of change linking its different interventions to poverty reduction. KOICA’s TVET example shows how Korea’s Vocational Training Centres are integrated in national programmes, facilitate entry in the various labour markets for some of the most marginalised and vulnerable groups, and were successfully scaled up from their start in Tashkent to other regions in Uzbekistan (Box 2).

Among the universal values Korea is committed to, gender equality appears to be insufficiently recognised as a policy goal across all programming. The 3rd Mid-term Strategy largely refers to women’s equality and gender in terms of narrowing the digital divide of vulnerable groups and extending them support, including mentioning education as a means to further women’s employment. KOICA’s human rights impact assessment checklist refers to human rights protection for women. To enhance gender mainstreaming across the programme cycle, CIDC has issued guidelines for performance management and evaluation, and KOICA provides implementing partners with guidance and results frameworks to better integrate gender perspectives into programme management along with information on how to use the gender marker according to OECD DAC reporting directives. Apart from one person each at KOICA and KEXIM-EDCF in headquarters, there are no dedicated human resources for gender equality and women’s empowerment in the OPC, ministries, agencies, or country offices (KCOC; KoFID, 2023[25]). In 2020-21, gender was considered a principal or significant objective in only 25% of Korea’s bilateral ODA commitments compared with the DAC average of 44%. Strong academic and civil society institutions do important work on women’s empowerment and gender equality in Korea and could more usefully be drawn upon.

Box 2. Korea’s grant support for TVET centres in five vocational training centres in Uzbekistan

KOICA’s country portfolio evaluation of 16 projects in Uzbekistan cites the high potential of investments in human capital in Uzbekistan – the most populous country in Central Asia with 35 million people, 64% of whom are under the age of 30, and where 500 000 youths are entering the job market each year. The evaluation, which scores the vocational training cluster projects that started in 2012, found TVET to be a cluster of excellence in the overall country portfolio and one with a high potential for future growth (KMA Consultants Inc., 2021[26]).

As acknowledged in a 2020 KOICA lessons learned report, many vocational training centres (VTCs) failed to secure budgets from governments at the end of the project. Thus, an important consideration is dispatching a volunteer and/or advisory team from the beginning to help integrate support to strengthen local capacity both in managing textbooks, workbooks, educational equipment and materials and in operating curriculums (Korea International Cooperation Agency, 2020[27]).

An advantage of VTCs is that they can demonstrate results more quickly than other education programmes. Korea’s grant support for five vocational training centres (in Tashkent, Samarkand, Shahrisabz and Fergana plus a centre for the unemployed in the city of Urgench located close to the Republic of Karakalpakstan) is an example of how Korea works to address vulnerable populations and inequality outside of the capital and main cities. Over a period of 11 years, a total of 11 736 people (9 794 men and 1 942 women), completed training in information and communication technology (ICT), electronics, car maintenance, metal working, welding, the textile industry, and cosmetology. Overall, there was an 86% graduation rate leading to a 94% employment rate and a 97% satisfaction rate among hiring enterprises. Korea’s EPS also benefits from the skills training of Uzbekistan workers. Some features of the scheme are as follows:

Tashkent VTC plays an important role in training and improving the overall system in Uzbekistan with strong links to responsible ministries, donors, and the sector working group on education and TVET.

Samarkand VTC has strong links to 205 local enterprises.

Shahrisabz VTC has tailored programmes to facilitate women’s employment.

Fergana VTC serves as a teacher training centre for teachers from vocational colleges in 11 regions nationwide.

Lessons learned include the need to work with government from the start to ensure sustainability (Korea International Cooperation Agency, 2023[28]). For example, setting salaries to a level that can assure quality teaching must be done by presidential decree for each centre in Uzbekistan, which takes time. The government also wanted to make sure that the certification from TVETs was recognised beyond Korea and Uzbekistan, including by the European Union, to open further job market opportunities. More ownership by the government and local communities could be fostered if the government and Korea hosted a forum or regular opportunities for stakeholders to share progress and give feedback on projects.

Korea is considering opportunities to expand work on VTCs, improve the institutional system through capacity building, and enlarge the market including through policy- and programme-based loans with a potential to further link KOICA and KEXIM-EDCF activities.

Note: This practice is documented in more detail on the Development Co-operation TIPs • Tools Insights Practices platform at www.oecd.org/development-cooperation-learning.

Source: KMA Consultants Inc. (2021[26]), KOICA Country Portfolio Evaluation: Uzbekistan, http://www.koica.go.kr/sites/evaluation_en/article/view/890; Korea International Cooperation Agency (2020[27]), Evaluation Lessons of Education Sector, http://www.koica.go.kr/sites/evaluation_en/article/view/909.

The 2020 revision of the Framework Act is a sign that Korea expects to adopt a more coherent, cross-government approach to implement a larger budget

The 2020 revision of the Framework Act strengthens the integration and co-ordination function of the CIDC, the highest development co-operation decision-making body, to help overcome the separate supervision of loans and grants, including those managed outside the two main ministries (MoFA and MoEF). The CIDC has strategic accountability and oversight and the mandate to develop medium-term ODA policy and annual implementation plans and to co-ordinate ODA policies and plans.

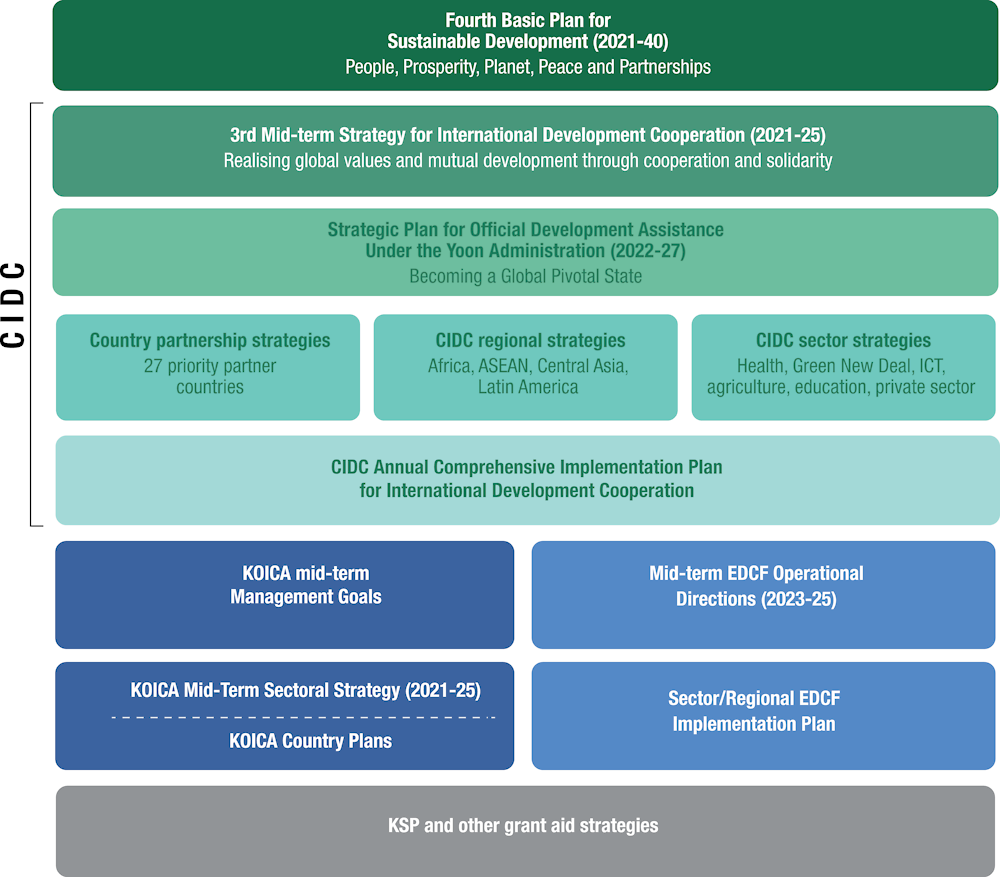

The CIDC has an opportunity to drive greater coherence across the increased number of strategies at different levels of government. Since the 2018 Peer Review, several inter-agency strategies have been enacted – for example on multilateral partnerships, green ODA, ICT and Africa. The strategies are detailed, link to the SDGs, and illustrate how Korea is working towards outlined objectives by identifying both projects that are underway and lead agencies and ministries. To support this, the Committee on Grant Strategy (chaired by the MoFA) and the EDCF Fund Management Council (chaired by the MoEF) have established grant and loan ODA strategies by sector and region. At the same time, KOICA and the EDCF (via KEXIM) continue to develop their own mid-term strategies, operational plans, and regional and sectoral strategies. Even though strategies at different levels are expected to align with the 3rd Mid-term Strategy and other strategies approved by the CIDC, the large number of strategies can be confusing to partners that may not understand why they are being approached by different entities or agencies in Korea's aid architecture and which strategy applies (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Korea’s various development strategies

Note: ASEAN = Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Source: Authors’ illustration based on Government of Korea (2023[29]), Self-Assessment of Korea.

The cross-government institutional capacity review is an opportunity to draw on the strengths of KOICA and KEXIM to support the delivery and quality assurance of ODA across the government. Given that ODA is not the core business of a number of entities responsible for ODA and that the Framework Act places added emphasis on performance management, experts from the evaluation committee are leading an institutional review to determine the capacity of implementers across the government to manage for results (Box 3). One avenue to explore is to draw on KOICA and KEXIM-EDCF expertise and strength in managing for results to lend cross-support to other agencies, although this would require additional resources.

Box 3. The Office for Government Policy Coordination’s cross-government effort to assess performance management capacities

In addition to the MoFA and MoEF, which supervise grants from KOICA and concessional loans from the EDCF (KEXIM), 41 other ministries and agencies in various sectors implement bilateral ODA in line with their area of expertise. The structural complexity of the fragmented ODA system creates challenges. One of these, as identified by Korea, is that is there may be gaps related to how different government entities measure performance and results of programmes that have development as a primary objective and that such gaps can affect the overall efficiency and effectiveness of its development co-operation.

The 2020 revision of the Framework Act strengthened the integration and co-ordination function of the CIDC. It established an Expert Committee for Evaluation to strengthen performance management. In May 2021, Korea adopted the Revision of ODA Performance Management System that mandates each implementing entity to conduct self-evaluations, the results of which inform annual implementation plans and future budgeting of programmes. As part of this effort, the CIDC is reviewing the ODA programme and performance management capacity across implementing ministries and agencies. The objective of the capacity assessment is to share experiences and, where feasible, share systems across implementing entities.

The review applies to all institutions with a budget of at least KRW 1 billion (USD 770 000). In 2022, 13 institutions were reviewed and in 2023, 12 were reviewed. The review looks at performance systems in place and the capacity of entities to conduct evaluations. For example, in terms of performance systems, it considers how planning and implementation align to Korea’s development co-operation strategies; the clarity of a performance plan and how efforts link across programming; and how consistently efforts are made to follow up on findings and maintain satisfactory or high performance. In assessing the self-evaluation capacity of entities, the review examines the evaluation system and clarity of the evaluation plan, ways in which evaluation quality is improving, and how proactively findings and recommendations are addressed and used.

A national research institute conducted the review and improvement plans, which consisted of a briefing session including each organisation and the CIDC, face-to-face interviews conducted by a private commissioner, and a desk review of performance data. Support and further consultation based on the review will continue in 2024. The results of the review will be used to design support to various entities in 2024.

Source: Authors’ interviews with Korean authorities.

The spread of Korea’s growing ODA programme and budget across over 45 other ministries and agencies represents opportunities and risks

In addition to MoFA, MOEF, KEXIM and KOICA, forty-one different government authorities manage 16% of Korea’s bilateral ODA, which risks diluting the quality and impact of Korea’s ODA. Yet, the sharing of Korea’s own development experience and advising in areas of expertise such as ICT, healthcare and green initiatives are an uncontested strength of Korea’s development co-operation (Figure 5). A real-time, integrated ODA reporting system is currently being rolled out, with implementing agencies sharing project information on a voluntary basis alongside incentives to link potential programmes at the country level. Such efforts can encourage entities without a permanent country presence in partner countries to work with other entities that are present. The sharing of experiences, sector expertise and knowledge requires a certain level of familiarity and experience in delivering and implementing programmes in partner countries, experience best drawn from KOICA and KEXIM-EDCF.

Figure 5. Korea’s ODA by government entity and co-operation modality, 2021-22

Source: Authors’ own illustration based on OECD (2023[20]), “Creditor Reporting System: Aid activities”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00061-en.

Korean embassies and KOICA country offices regularly support the different ministries and agencies that do not have permanent representatives at country level, which can detract from their more strategic work in partner dialogue and from delivering their own country programmes. As seen in Uzbekistan, where 34% of Korea’s ODA is implemented by other agencies,17 the embassy and KOICA often facilitate the visits of authorities responsible for implementing or evaluating grant projects and liaise with Uzbek officials. These additional tasks take time away from the important project management and stakeholder liaison activities and growing responsibilities of KOICA and the embassies. It would be worth exploring alternative ways of facilitating the development co-operation of Korean entities that do not have a country presence.

Korea will need to carry out integrated and large-scale ODA projects to realise the president’s strategic plan for ODA. In Seoul, the OPC is piloting strategic packaging of grants, loans, and public and private ODA to increase project size and build on synergies. Since 2017, project size has increased for KEXIM-EDCF and KOICA, but not for the MoFA.18 In view of growing ODA volumes, it is laudable that the Korean government is considering ways to create greater efficiencies and impact across its development co-operation programme, including across public and private investments. In an endeavour to create larger and more integrated projects, for example, the OPC is piloting an initiative to bundle ODA projects and programmes across instruments and government entities at the design stage, with a focus on the country level.19 Programmes identified by the OPC as having a packaging merit are prioritised and fast-tracked through the budget. The CIDC’s annual implementation plans also highlight opportunities for bundling grants and loan operations and indicate where duplication has been avoided20 (Government of Korea, 2023[30]). Since 2021, 19 packages21 in 10 countries have been identified.

Strategic packaging efforts led by the OPC are a good objective and could be facilitated by more integrated programming across agencies. In its piloting efforts, the OPC has been involved in operational decisions that have been quite detailed at times and also in spending reviews of projects managed by implementing agencies. These activities build on the work of grant and loan committees organised by the MoFA and MoEF since 2021-22 that also consider ways to bridge and sequence programmes across implementers in the same country. Efforts to strengthen linkages across projects have not yet resulted in an integrated approach to programming across implementing partners; each partner continues to plan, program and evaluate its ODA programme and efforts individually. A single overarching performance framework for each package and an evaluation of the pilot could help inform future adjustments. In the future as larger packaged programmes are developed at the initial idea and design stage, efforts across the government could be more streamlined.

Efforts by the OPC to co-ordinate and strengthen linkages across projects are likely to require greater decentralisation and human capacity and speedier procedures. Designing more integrated programming and packaging future investments into larger-scale projects are likely to be more effectively done at the country level. Yet, implementing agencies find more integrated programming challenging due to unsynchronised timelines and planning cycles across agencies and partner organisations. With its political convening power, the CIDC could issue guidance and instructions to cross-government entities managing ODA, embassies and country offices to drive greater collaboration in response to partner country priorities. This would require identifying a responsible party to take the lead on the design or to manage packages or programmes. Additional incentives are likely to be necessary, including in the form of human capacity at the country level where the embassy, KOICA and KEXIM-EDCF are insufficiently staffed to consider any expansion of current activities. By shifting packaging efforts to the partner country level, the CIDC and OPC could play an important role by working to address systemic challenges for a more integrated approach and communicating results in line with OPC’s strategic co-ordination role.

Implementing the humanitarian-development-peace (HDP) nexus will require working more across government and with partners

The 2024 budget proposal to more than double humanitarian assistance and Korea’s preference for multilateral channels are welcome as responses to growing needs. Ministries other than the MoEF and MoFA managed 13% of humanitarian assistance in 2021-22, with most of this portion managed via the World Food Programme (WFP). Korea is to be commended for the trust it places in and the contributions to the multilateral system, which is by far the preferred channel for its humanitarian assistance.22 Recent revision of the Overseas Emergency Relief Act opens the possibility to adopt a more flexible approach across humanitarian and development budgets in its multilateral support. This will be particularly crucial in protracted crises where humanitarian and development needs are not clearly delineated and as Korea determines how it could more directly support local communities, in line with the DAC Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus [OECD/LEGAL/5019] and Grand Bargain commitments to localise aid (KCOC; KoFID, 2023[25]). In 2021-22, 78% (USD 269 million) of humanitarian assistance was delivered via multilateral channels, while a very small portion – only USD 1.1 million – was delivered via local CSOs.23

Korea’s HDP nexus implementation plan and revised humanitarian assistance strategy are opportunities for Korea to consider a more holistic, cross-government response to crises. On average in 2020-21, 43% of Korea’s bilateral ODA went to fragile and conflict-affected states and crisis contexts.24 This share will continue to grow given that KOICA’s Conflict and Fragility Program is expected to increase by 266% from 2023 to 2024. The recent amendment enlarging the scope of the Overseas Emergency Relief Act beyond emergency relief would help make an HDP nexus approach legally binding across the government.25 The amendment would also helpfully establish a formal space for policy dialogue with all stakeholders including civil society in line with Korea’s current support and training to expand the capacity of Korean NGOs. Implementing the DAC Recommendation on the HDP nexus would pave the way towards a more integrated and longer-term engagement in fragile and conflict-affected contexts – one that, in addition to emergency response, considers conflict prevention and peace objectives and aims to reduce vulnerabilities (including those that are climate related). As is the case for most DAC members, such a shift is likely to require more cross-government co-operation and new ways of working that stretch beyond the current core humanitarian team of five officials in the MoFA plus KOICA country offices. Some DAC members have already adapted and modernised their administrative architecture with the nexus in mind. The successful implementation of KOICA’s Conflict and Fragility Program will also depend on more fluid co-operation across humanitarian assistance and development budgets. KOICA is working to adapt its administrative architecture to better reflect a more integrated approach in responding to crises in conflict-affected and fragile contexts.

Strengthening and working with civil society, academia, contractors and the private sector will enlarge the pool of development experts

Korea’s own development story helps cultivate a favourable public opinion of Korean development co-operation and could also be leveraged to attract more talent. Strong public and legislative support in Korea – even if slightly declining – are enviable compared with other DAC countries, and there is a minimum baseline of public awareness of ODA and the benefits it has already brought to Korean society and will continue to bring to the international community. The human resource plan focuses on supporting development co-operation talent by expanding the development ecosystem and making careers in international development more attractive to young graduates. For example, exploring ways to increase the uptake in the World Friends Korea Overseas Volunteer Program, which decreased in recent years, is one way forward (Government of Korea, 2022[31]).

Cross-government relationships, including with contractors and the private sector, can help operationalise the 3rd Mid-term Strategy and the human resource plan (Box 6). A development ecosystem consists of the public sector as well as the NGOs and private sector present in Korea and partner countries. Employing more development co-operation experts in all three sectors will diversify expertise and could attract development professionals working outside of Korean development co-operation. Promoting co-operation with civil society through longer-term partnerships and working more closely with private companies could help create more opportunities to employ development professionals. Through KOICA’s open position system, experts were hired from outside of government for five positions in 2018 and three in 2020. Today, only a handful of development consultants are involved in grant aid and technical co-operation, although efforts are being made to create a greater supply of experts (Box 4)

Historic linkages with academia in Korea and in partner countries are a powerful demonstration of rich people-to-people exchanges. As seen in Uzbekistan, partnerships between academic institutions based in partner countries and Korea are based on learning by doing and capacity building. Faculty exchanges and volunteer opportunities are defined in memoranda of understanding with Korean universities. Partners appreciate how Korea works to co-create concepts to build capacity on e-government and digitalisation and also brings the technical means and infrastructure improvement necessary to implement projects. For example, in 2007, Korea worked to establish the first library information system in Uzbekistan. Through exchanges, Korea is also able to promote global values through a more discrete and collective approach that may take more time but is considered by partners to be more sustainable, for example bringing Korean minorities to advocate for universal rights in Uzbekistan.

Box 4. Developing a pool of external evaluators for EDCF loan operations

KEXIM has historically had more difficulty finding qualified external evaluators for ex-post EDCF loan operations than other ODA agencies in Korea. The major bottleneck was evaluators’ lack of knowledge about loan operations more broadly.

To address this challenge more sustainably, in 2023 KEXIM-EDCF decided to work to improve the evaluation ecosystem in the medium to long term through a training programme for evaluators. KEXIM-EDCF had an idea of what the coursework should look like but did not have specific experience in developing such a curriculum. Partnering with the Ewha Woman’s University’s Graduate School of International Studies, including by offering courses in design and management with faculty members who had knowledge and experience conducting EDCF evaluations, was key to the collaboration to develop the pilot course. In developing a curriculum for international development co-operation researchers, lessons were also drawn from KOICA’s association with the Korea Society for International Development and Cooperation. Integrating the programme into a course at the graduate school allowed for more in-depth training and, as part of the coursework, practical experience in conducting an evaluation at a project site. In 2023, 17 students finished the coursework for this course and three students participated in a summer break trip to Viet Nam to do an actual aid post-assessment of a road project. An incidental consequence of the course is that foreign students attending the course – some of whom are government officials from partner countries – will have gained greater awareness of Korea’s ODA projects internationally. KEXIM-EDCF benefited from the graduate school’s holistic approach to development and focus on cross-cutting issues (environment, gender, targeting vulnerable groups, etc.) that together with more technical infrastructure expertise will continue to add depth to the evaluation of ODA and improve evaluation quality. There are indications that other universities and research institutes have asked to establish similar courses in evaluation.

For KEXIM-EDCF, an important lesson learned was that this type of training was doable but also requires firm commitment from both KEXIM and the graduate school. Moreover, the fact that the course was a project linked to an actual evaluation motivated many students to select the course. Since not all students participate in the fieldwork, which ideally involves four to five students and three to four researchers, the initial evaluation of the pilot course recommended that students who do not take part in the on-site evaluation should be involved in domestic stakeholder interviews that can be conducted in country (Export-Import Bank of Korea, forthcoming[32]). Granting an academic credit to students conducting the field work could attract greater participation. Finally, recognising students’ successful participation in the course, for example by awarding a certificate of completion, is worth considering as a way of increasing student interest and future employment opportunities.

Note: This practice is documented in more detail on the Development Co-operation TIPs • Tools Insights Practices platform at www.oecd.org/development-cooperation-learning.

Source: Export-Import Bank of Korea (forthcoming[32]), EDCF M&E 전문가 양성 프로그램: 이화여자대학교 [EDCF M&E Specialist Training Program: Ewha Woman’s University].

Since the 2018 DAC Peer Review, the Korean government has clarified its partnerships with civil society through a new policy and implementation plan. The Government-Civil Society Basic Policy Implementation Plan and different platforms for dialogue26 help monitor the implementation of 31 action points for short-, medium- and long-term implementation. They also are opportunities to explore longer-term partnerships and less transactional support. One example would be to expand the scope of KOICA’s incubation programme to build capacity of CSOs, activate multi-stakeholder platforms and diversify support beyond sectoral support to enhance civil society autonomy; another would be to eventually establish a joint government-civil society partnerships fund. In partner countries, the Government-Civil Society Basic Policy Implementation Plan aims to expand capacity-building support to local civil society; prioritise vulnerable groups; mainstream human rights, peace and women’s empowerment; and strengthen Korea’s support for prevention of sexual violence in conflict (Government of Korea, 2023[33]).

The Korean government has officially recognised civil society as a partner, but ODA funding to civil society still lags. It is noteworthy that it was only after the 2010 Group of Twenty Summit in Seoul that the internationalisation of Korean civil society took place, with CSOs starting to organise themselves to expand their role beyond that of implementer or facilitator to one that encompasses working to influence policies through advocacy and development awareness activities – as an equal partner (Kim and Hong, 2022[34]). Yet, in 2021-22, civil society only received 2% of Korea’s bilateral ODA (in project support only) compared with the 15% average share in DAC countries. There is yet little evidence that civil society’s contributions are given weight in the policy-making process. Expanding partnerships with civil society could also be a way for Korea to test a broadening of partnerships including with the private sector, international organisations and foundations. Multi-stakeholder partnerships could build on Korea’s narrative around its own development experience to add value and achieve more sustainable impact.

There are strong signs that Korea is prepared to incentivise Korean civil society to partner with regional or local civil society to help build mutual capacity and allow for greater focus on locally led development, including to address more sensitive issues. For example, KOICA projects are required to apply a human rights impact assessment checklist that looks at whether the programme has identified the programme’s core risks to human rights and how the programme considers human rights protection for vulnerable populations, gender-sensitive planning, protection of the rights of children and youth, and the safety of planned buildings and facilities. KOICA endeavours to support local partners by building capacity of local CSOs, although direct project-based support for local CSOs was suspended in 2015. As seen in Uzbekistan, finding ways to spend more time engaging with communities at the local level and with civil society, for instance by creating incentives for Korean civil society to partner with local civil society, could extend the scope, depth and reach of Korea’s current programming, including in sensitive areas such as gender-based violence. Addressing some of these core planning and implementation risks through civil society and with other donors will also help Korea manage for different risks across public investments.

Recommendations

4. Korea should consider the cross-government capacity review alongside evidence and learning from evaluations to help prioritise increased ODA volumes to implementers with high performance management capacity, in line with the 3rd Mid-term Strategy objectives.

5. The government should allocate ODA increases in line with needs and absorptive capacity of partners by encouraging the full use of existing modalities, including programme-based loans and policy dialogue.

6. To increase effectiveness and sustainability, Korea should engage in more upstream and regular policy dialogue with partner country authorities, partners and stakeholders on broader reform processes and the policy environment to help ensure the financial sustainability of its programming, using existing co-ordination mechanisms where possible.

7. Korea should strengthen the capacity of Korea’s civil society to deliver effectively and incentivise partnering with local civil society to broaden the reach of Korea’s programming, strengthen local capacity and foster locally led development.

Managing for sustainable development results and impact

Strong leadership by the Prime Minister’s Office (OPC) working with the MoFA, MoEF and the line ministries is essential to delivering on Korea’s ambition to scale up ODA based on results

The revision of the Framework Act on International Development Cooperation has strengthened performance management across government through a stronger OPC. The 2018 DAC Peer Review of Korea recommended that the CIDC take a stronger role in providing strategic-level oversight and accountability for development results by focusing more on policy-level issues (rather than operational-level decisions) (OECD, 2018[24]). The 2020 revision of the Framework Act27 strengthens the CIDC’s role in performance management throughout the project cycle and expands the use of evaluation results (Republic of Korea, 2020[35]). Evaluation results28 are considered by the CIDC’s Expert Committee on Evaluation when discussing and deciding the next comprehensive strategy and (annual) implementation plan. The MoEF budget office also considers evaluation results alongside national priorities in fine-tuning ODA allocations.

The OPC is well positioned to extract lessons for greater accountability in terms of a focus on sustainability of ODA programmes. The 2018 Peer Review noted that where projects were less than satisfactory, there was often a lack of attention to sustainability and limited understanding of how recurrent costs would be financed at the national or local level (OECD, 2018[24]). Recent evaluations repeatedly identify the sustainability of programming as a key risk. Projects with a high level of sustainability grew out of strong national ownership and political will. For a project on capacity building of e-government in Nigeria, for example, working with the Federal Ministry of Communications, Innovation and Digital Economy played a crucial role in building awareness with ministries, departments, agencies and members of parliament, which led to strong buy-in from the government and parliamentarians. In turn, the government of Nigeria used its own budget to establish an e-government standing committee for the training centre, helping to secure sustainability (Korea International Cooperation Agency, 2022[36]). Continued policy dialogue with the partner government in priority focus areas is a key strategy to mitigate risk and increase the likelihood of sustainability. A good example is the policy dialogue Korea has initiated in Uzbekistan to make its TVET centres more sustainable by securing increases in salaries via presidential decree (Box 2).

In addition to the need for complementary legal, institutional or other support, there is a further need to enhance partner countries' capacity and accountability in managing results and sustainability risks. For example, the Tashkent Medical Cluster, which includes the National Children’s Medical Center, a hospital for adults and the National Oncology Centre funded by the EDCF, offers state-of-the-art care. However, the facility is not easily accessible to the public since out-of-pocket costs are considerable. Recognising that the Uzbek national insurance policy does not extend coverage to hospital patients, Korea has been providing policy support to enhance the sustainability of the project. While this risk was likely identified at the onset, greater co-ordination among Korean implementers and dialogue with national authorities and other development partners might have led to a better understanding of ways the investment might have been more accessible to the general population, for instance through better sequencing of complementary investments. Continued dialogue and co-ordination are especially important when different implementers are involved in the feasibility study, design, and construction and supervision stages.29 For instance, an ex-post evaluation conducted within seven years of completion of a road improvement project in Sri Lanka showed that the minimum budget to maintain roads had not been allocated by Sri Lankan authorities. This was a critical condition for sustainability, not least since the road was in a mountainous region where slope sliding is inevitable (Economic Development Cooperation Fund, 2021[37]).

Country partnership strategies outline priorities that help focus requests from partner governments, as seen in Uzbekistan, and allow for some flexibility to fund outside the scope of focus areas. In Uzbekistan, the OPC designated KEXIM-EDCF as the lead agency in the elaboration of the country partnership strategy (CPS). The priorities outlined in each CPS allow Korea to have more structured conversations with partner governments on how to advance mutual priorities.30 Priority sectors specific to each country are allocated 70-80% of resources in a CPS, leaving 20-30% of resources that can be allocated more flexibly. Such flexibility allows for some adaptation based on regular monitoring (see discussion of managing for sustainable development results) and could serve to respond to some of the key risks and challenges identified across programming where these are not directly related to the focus areas.

Drawing lessons from evaluations could also enable the OPC to design instructions and clear criteria to fast-track spending and budget execution. Given the growing ODA budget and typically long lead times required to plan ODA investments, complete budget utilisation is a risk. The strengthened organisational structure31 and mandate of the OPC to manage for results put it on a strong footing to consider options to fast-track spending in a way that is consistent with the 3rd Mid-term Strategy objectives and performance. Transparent, measurable criteria to fast-track or accelerate implementation could expand upon the current prioritisation of strategic and national objectives. Designing clear instructions and delegating responsibilities at the partner country level to scope and design more packaged and larger programmes, with the expectation that high-quality proposals would be fast-tracked, are good incentives so long as project selection remains insulated from political expediency. The OPC could also help identify larger or more corporate programmes or partnerships that may not be country specific and that could be fast-tracked.

Korea’s strong emphasis on accountability could be more balanced with learning across the system. Different governmental bodies in Korea, in addition to carrying out evaluations, also conduct audits. For historical reasons,32 both the Board of Audit and Inspection and the National Assembly’s standing committees conduct audits. These are in addition to MoFA audits. Organising and responding to such exercises each year take a considerable amount of time away from other tasks. It is unclear whether ODA is audited more than other government activities, but evaluation and audit fatigue appears to overcome entities responsible for ODA at certain times of the year, suggesting there is a need to reconsider the balance between learning and accountability. Behind the CIDC’s drive to strengthen Korea’s ODA performance management is a desire to improve both the public’s understanding and the transparency of international development co-operation programmes. More clearly communicating Korea’s contribution to sustainable development and sharing lessons across implementers could enhance learning.

An organisational culture for results, reflected in KOICA and KEXIM’s strong performance management systems, offers a good example for other ministries and agencies

A strong internal organisation culture, dedicated resources and results methods including a Performance Indicator Model based on the SDGs together form a solid foundation on which Korea can continue to develop its performance-based management system. The 2018 DAC Peer Review underscored that other government ministries did not necessarily match the KOICA and KEXIM-EDCF efforts and that there was work to be done beyond these two agencies to ensure that results-based management is applied throughout the Korean development co-operation system – a point reinforced by a Board of Audit and Inspection finding in 2022 (Board of Audit and Inspection of Korea, 2023[38]). Building on the large number of evaluations, increased communication such as KOICA’s lessons learned reports (Box 5), and the solid project results-based management system it has built and fine-tuned over time, Korea is now turning its attention to building the capacity of other Korean actors that operate in partner countries to manage for results (Box 3). Enhancing country ownership, mutual accountability and transparency should be at the centre of such efforts. As a start, monitoring and evaluation reports of projects not managed by KOICA or KEXIM-EDCF could be more systematically shared.

Korea’s self-assessment indicates that Korea plans to enhance evaluation quality by diversifying evaluation methods, such as joint evaluations with partner countries and universities, with the aim to embed evaluation results into ODA projects (Government of Korea, 2023[29]). Areas for prioritisation could include strengthening partner capacity, including in conducting joint evaluations as KOICA is doing in many countries, and relying more on partners’ monitoring efforts. In Uzbekistan, a joint evaluation by KOICA and the Uzbek Ministry of Investment, Industry and Trade was cited, but this is not usually a main feature of evaluations conducted by overseas missions. Some multilateral development partners indicated that while the emphasis on evaluation for Korean projects and contributions is appreciated, conducting these jointly with partners would likely elevate the role of evaluations as an instrument that can be used to adapt programming and inform future project concept papers.

Korea has professional and robust implementers in KOICA and KEXIM-EDCF with a clear vision for reform and ensuring project and performance management systems and also has strong evaluation and feedback loops in place to adapt and manage for results. Korea – as demonstrated by the MoFA, MoEF, KOICA and KEXIM-EDCF – takes evaluation seriously and good use of public funds is scrutinised. For example, multilateral partners in partner countries speak of detailed feedback sessions and country dialogue with KOICA on grant implementation alongside increasing demands for evaluations to be conducted annually and conducted semi-annually around sector instruments and for ad hoc requests. Ex-post evaluations are conducted by major implementing partners seven years after project completion. Based on Korea’s strong performance management, the country’s core multilateral contributions already consider the results of the Multilateral Organisation Performance Assessment Network’s assessment of Korea’s development co-operation together with the government’s opinion of the assessment, outcomes achieved and budget execution rates – all elements that can help steer Korea as it considers multilateral ODA increases. Korea is working on a more supportive information technology system to publish evaluation outcomes.

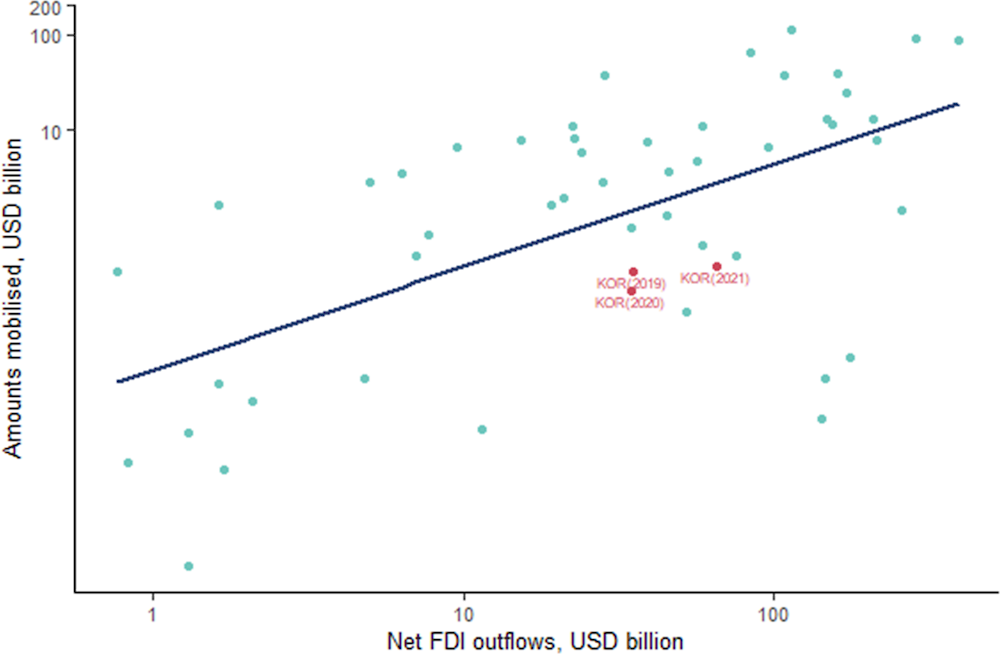

Box 5. KOICA’s lessons learned reports