Caroline Klein

Jonathan Smith

Caroline Klein

Jonathan Smith

The Danish labour market is strong, but tensions have increased since the pandemic. The post-pandemic recovery boosted labour demand, but structural factors, such as late labour market entry by the young, changing skills requirements and obstacles to the recruitment of migrants, contribute to persistent shortages and impact the wider economy. Lowering the effective tax rate on labour income could reduce disincentives to higher working hours and to moving from part-time to full-time employment. Adapting the workplace to an ageing population and adjusting early retirement schemes could help to extend working lives. Targeting the tenth grade to students with greater learning needs, reducing student allowances and introducing an income-contingent loan system for master’s students could also encourage faster entry into the labour market. There is room to increase the recruitment of foreign-born workers, as well as improving their integration. The demographic, digital and green transitions will transform jobs and skills requirements, demanding an agile education and training system throughout the working life. Encouraging vocational education and training, notably by facilitating mobility between vocational and academic tracks, would ensure strong skills in areas where workers are lacking.

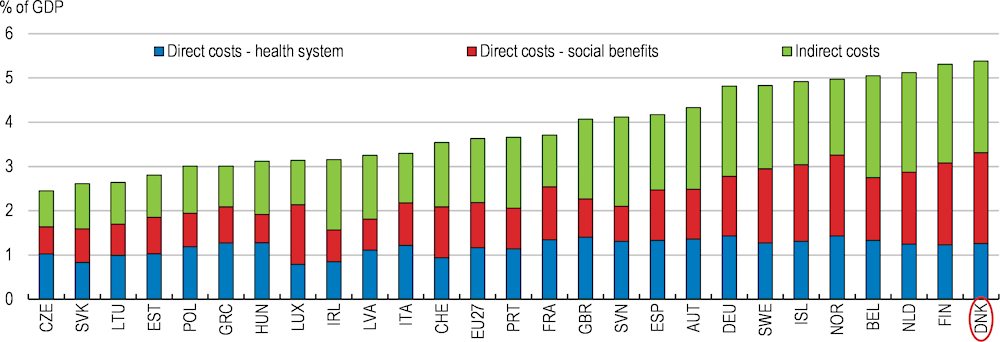

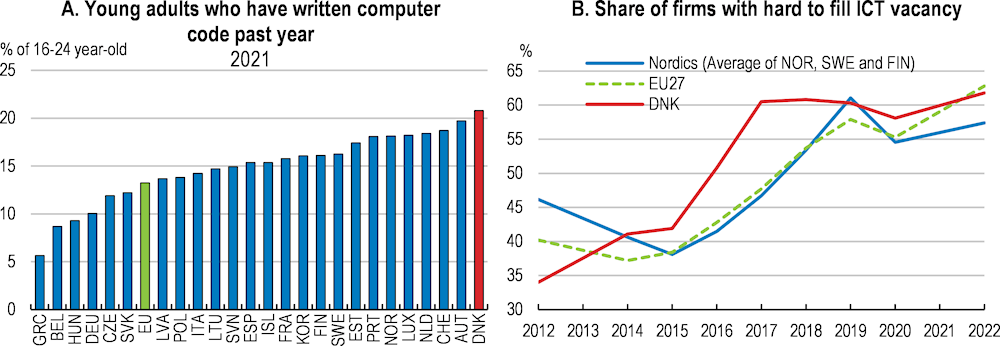

Tensions in the Danish labour market increased dramatically after the pandemic. Employment has reached record high levels and recruitment difficulties worsened, especially in some sectors, such as construction, information and communications (ICT), and healthcare, where shortages have been persistent. While cyclical factors such as the fast post-pandemic recovery played an important role and similar trends can be seen in other countries, structural factors hold back the availability of labour, as reflected in low hours worked and late labour market entry by the young. Structural megatrends in terms of population ageing, the green transition, and digitalisation will transform labour demands and skills needs.

Against this background and while increasing the labour force is not an objective in itself, tackling and managing labour shortages is key. Shortages risk adding to supply-driven inflation pressures in the current environment and could trigger unwelcome competitiveness losses via increases in wages. Labour shortages are a barrier to investment and business dynamism, which can negatively affect economic growth. Shortages of labour in key sectors, such as long-term care and the public sector, could make it difficult to maintain living standards.

This chapter identifies where labour market tensions are likely to persist and intensify, the underlying causes, and proposes avenues to increase labour supply and address shortages. It presents policies to sustain labour force participation and to develop and better use the competences of the Danish workforce in the context of demographic changes, and the digital and green transitions. These include reducing the disincentives to work and retire later; better attracting and integrating migrants; encouraging the young to start work earlier; and providing the relevant skills to thrive in this changing environment, including policies to adapt the education system to future labour market needs.

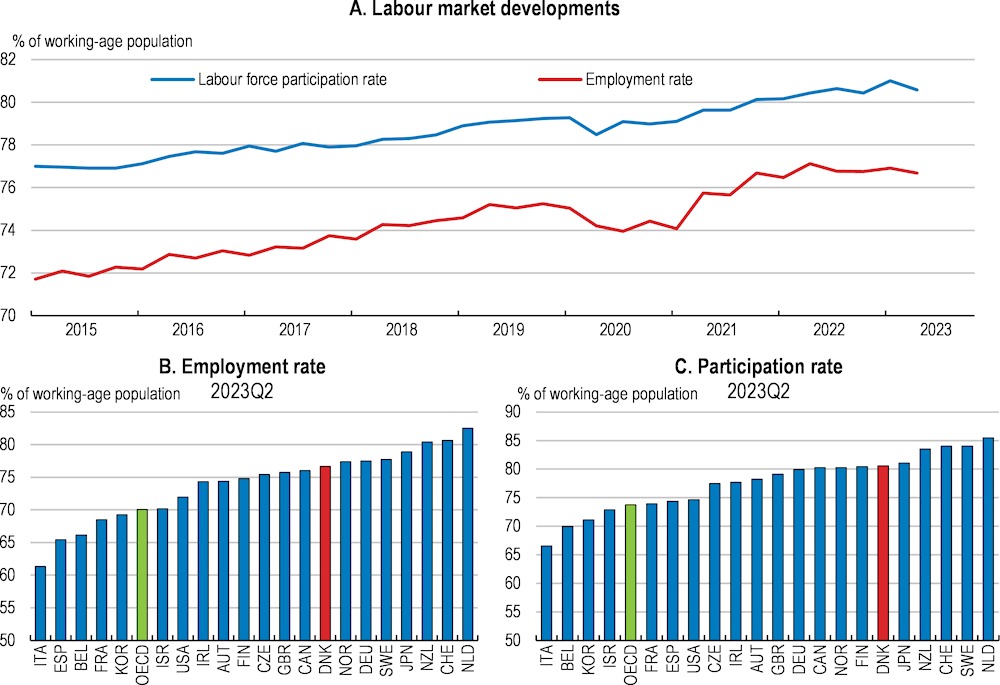

Denmark’s labour market generally works well. The employment rate – the share of the working-age population in employment – has increased fast over the past decade and is relatively high compared to many other OECD countries (Figure 2.1). Rising labour market participation, including of groups with historically lower attachment to the labour market, notably older and foreign-born workers, and a falling number of unemployed have contributed to this performance. This reflects good economic conditions, a well-developed labour market institutional set-up, and policy measures that strengthened work incentives and integration programmes. Working conditions in Denmark are good by international standards, with low job strain (from high work demands and insufficient resources) and flexible working arrangements (OECD, 2018; European Working conditions Survey, 2021). Overall, gender gaps are low by OECD standards, with women’s wages, participation, and employment rates close to those of men.

Note: Panels A and B refer to the share of the population aged 15-64.

Source: OECD Short term labour market statistics.

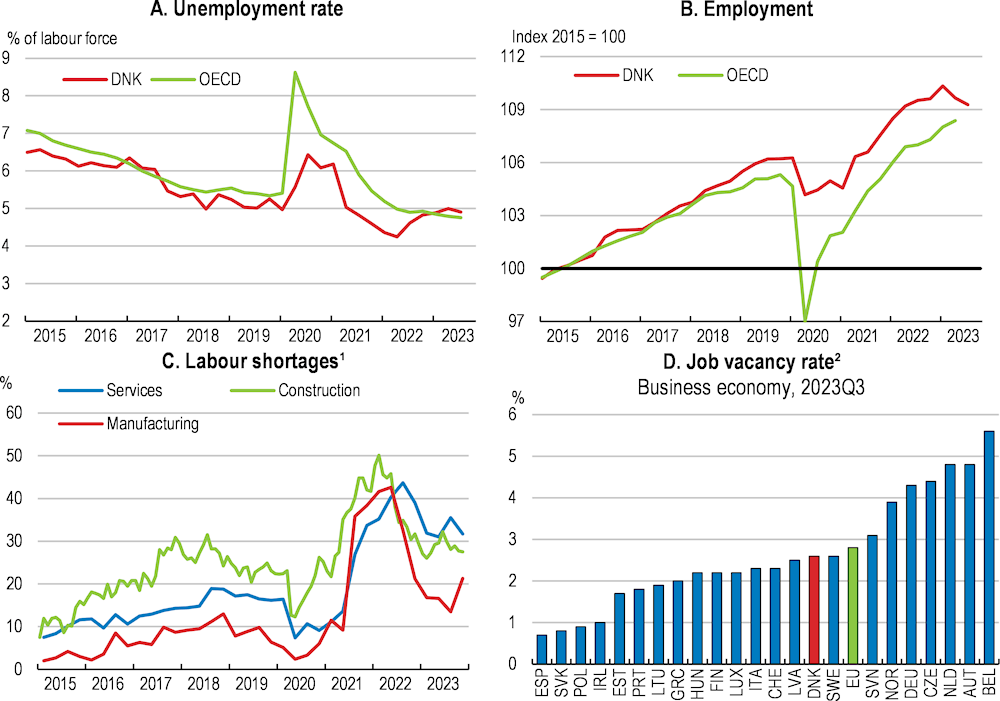

The labour market has been resilient to economic shocks over the past few years and is very tight. During the COVID-19 crisis, the unemployment rate increased by around 1 percentage point, less than in most EU countries, and quickly returned to its pre-crisis level (Figure 2.2, Panel A). A temporary job retention scheme largely avoided substantial job losses, while allowing people to return to their jobs once the economy improved (OECD, 2021a). After the strong recovery in 2021 and despite some growth slowdown since 2022, employment has continued to grow until early 2023, reaching record high levels (Figure 2.2, Panel B). The number of people not in employment (either unemployed or inactive) has declined steadily in recent years with an increasingly small fraction of this group available for work.

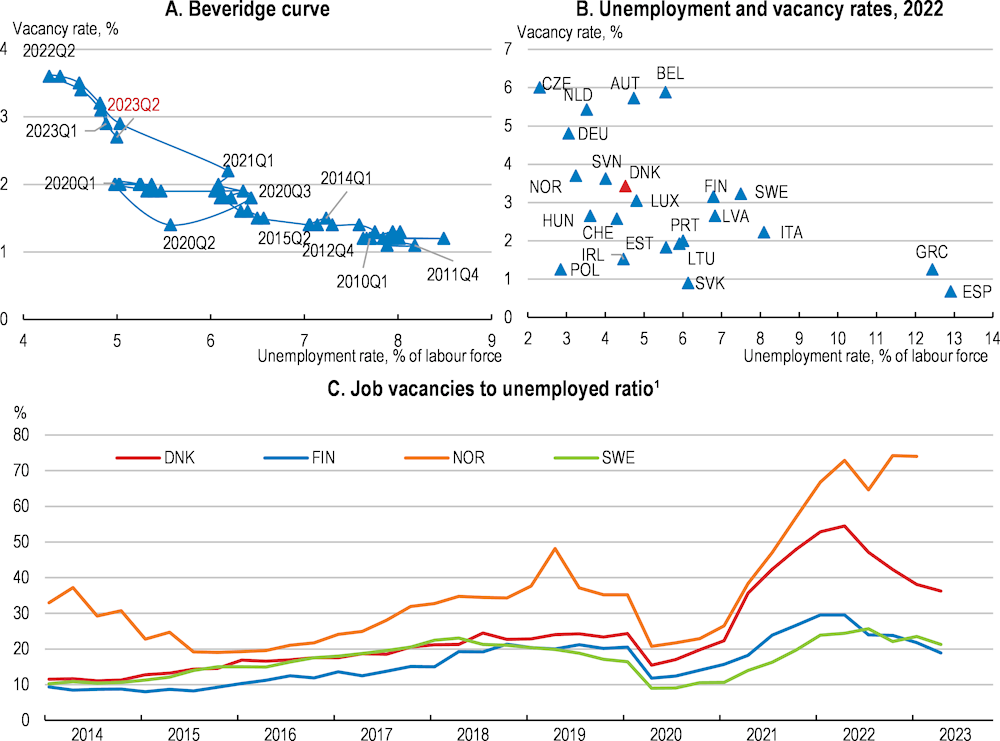

Strong labour demand combined with fewer available workers has led to an increasing number of firms reporting labour shortages. Labour shortages reported by firms peaked after the economy re-opened and still exceed their pre-crisis level (Figure 2.2, Panel C). Between September 2022 and February 2023, around one in four companies reported difficulties to recruit (STAR, 2023). The simultaneous increase in vacancies and decrease in unemployment drove the vacancies-to-unemployment ratio to all-time highs (Figure 2.5, Panel C). This has however declined since 2022, as has the number of failed recruitments attempts and the job vacancy rate (the number of job vacancies divided by the number of occupied and vacant posts), which now stands close to the EU average (Figure 2.2, Panel D).

Cyclical factors played a role in this tightness as the economy has rebounded, but structural trends have increasingly been driving labour market shortages, which predate the pandemic. Digitalisation and the green transition are altering the skill composition of labour demand, particularly given Denmark’s ambitious climate goals, and this is also exacerbating the challenges of demographic change. Severe shortages are already prevalent in fields directly affected, such as long-term care and engineering, with labour supply falling increasingly short of demand (McGrath, 2021).

1. Percentage of firms reporting shortages of labour as the main factor limiting their business.

2. The job vacancy rate is the number of job vacancies as a percent of total occupied posts plus job vacancies

Source: OECD Analytical Database; DG ECFIN - Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs.; and Eurostat (JVS_Q_NACE2).

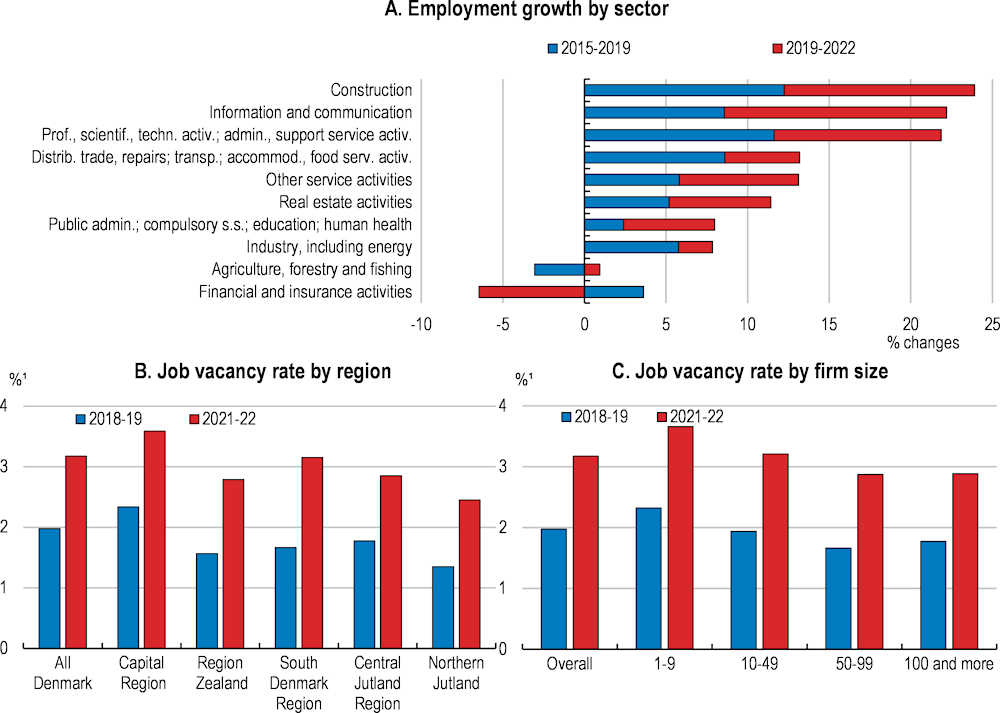

Employment has grown strongly in almost all sectors of the economy since 2015 and tensions in the labour market have increased in all regions and types of firms, making it difficult for businesses to operate at their desired production level (Figure 2.3). Staff shortages were reported by 42% of Danish businesses in the first quarter of 2022, and 21.2% of employers identified labour shortages as the main factor limiting production in the fourth quarter of 2022, up from 6.4% in the fourth quarter of 2019 (European Commission, 2023a; EIB, 2023a). Labour shortages have been more pronounced and persistent for some activities and in small firms (STAR, 2023; Figure 2.3, Panels A and C). In the service sector, 39% of firms (in the fourth quarter of 2022) identified labour shortages as the main obstacle for carrying out business, higher than the EU average of 30%, and more than double the figure of 16% in the fourth quarter of 2019 (European Commission, 2023a). Construction has experienced intense skill shortages since the COVID-19 crisis, due to high demand for housing and government support for energy efficiency renovations. Tensions in ICT and healthcare have also accentuated, similar to other countries, during and in the aftermath of the pandemic (McGrath, 2021).

1. The job vacancy rate is the number of job vacancies as a percent of total occupied posts plus job vacancies.

Source: OECD Quarterly national accounts; and Statistics Denmark.

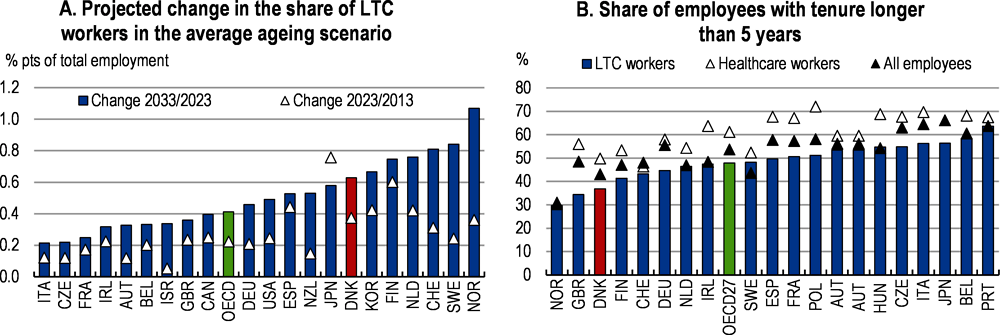

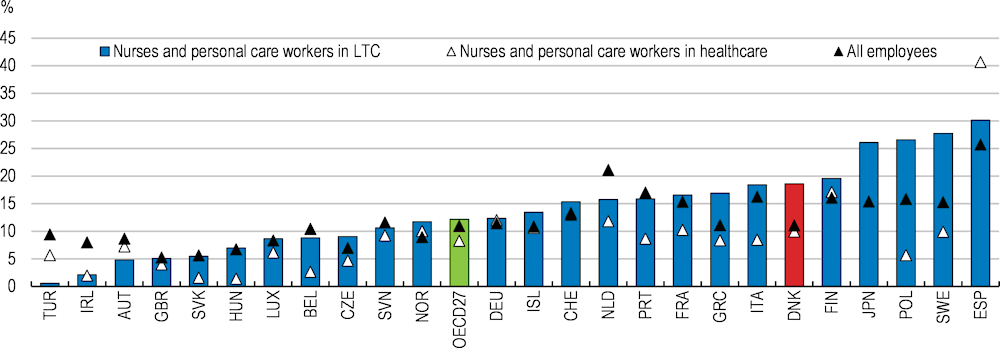

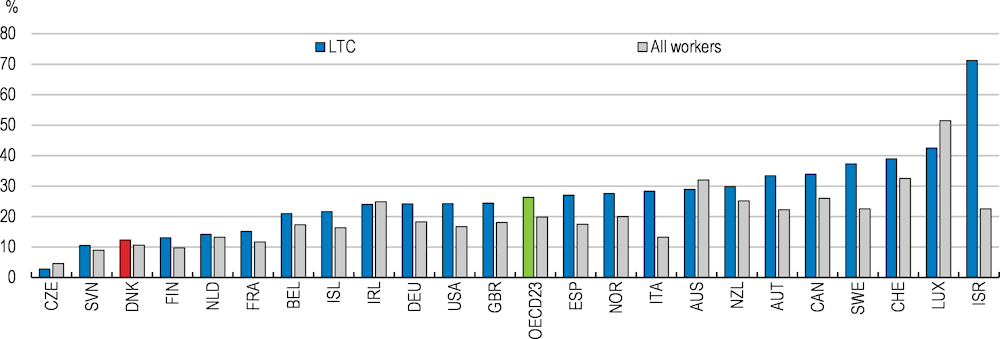

An important area of labour shortages is the public sector, particularly activities related to health and long-term care, given demographic changes (European Commission, 2023a). Public employment in Denmark accounts for around 30% of total employment, well above the OECD average, but comparable to other countries with strong welfare states (Figure 2.4). Public sector employment increased during the COVID-19 crisis and has not returned to its pre-crisis level yet. Employment growth has been relatively fast in the central administration and the regions (Figure 2.4, Panel B). Despite the increase, total public employment as a share of employment is below historical averages, which suggests this growth has not crowded out private sector employment. The number of public employees per 100 citizens was also below historical averages in 2022. Employment in municipalities is only just above the level in 2008, despite the decentralisation of and increasing demand for welfare services. Recruitment difficulties have been acute in the healthcare and the long-term care sectors with lack of staff identified as the biggest challenge for Danish health authorities. For example, around 18% of advertised nursing positions were unfilled as of June 2023, only slightly down from around 25% before the pandemic (STAR, 2023), and a shortage of around 15,000 healthcare assistants and helpers is expected by 2035 (Ministry of Finance, 2023).

Persistent labour shortages are detrimental to economic growth and well-being, and compound challenges related to demographic change. While raising employment is not an objective in itself, human capital is a key resource in the production process which cannot be perfectly substituted. Shortages can be particularly problematic for specialised skills needed to raise productivity, particularly in the ICT sector, and specific labour shortages can have a disruptive negative impact on the provision of essential goods and services, such as retail trade and healthcare, and reduce both the volume of potential output in the long run and the productivity of capital investment, thereby weighing on productivity growth and business dynamism. Labour shortages are viewed as the highest barrier to investment across all sectors and firm sizes in Denmark (EIB, 2023a). They can lower the quality of matching of workers and jobs, and shortages in knowledge-based services and ICT could impede the diffusion of technologies (Sorbe et al., 2019). As stressed in the 2019 Economic Survey of Denmark, the lack of skilled labour force could partly explain issues for new firms to scale up (OECD, 2019a). While increases in wages help to narrow the gap between labour demand and supply, caution is needed in the current inflationary environment to avoid excessive wage increases that might unduly harm competitiveness. It is also important to ensure the necessary allocation of resources across sectors in a sustainable way, which may not happen purely through wage changes even with Denmark’s relatively flexible wage-setting system.

The growth in labour demand and shifts in relative demand between sectors have so far been facilitated by two features of the Danish labour market. First, the Danish labour market model, the so-called “flexicurity model”, with low hiring and firing costs and decentralised wage negotiations, has allowed for swift adjustment. After the lockdowns, job mobility was high, with rapid reallocation and high turnover of workers (Danish Ministry of Finance, 2021). Indicators suggest labour shortages reflect the growing imbalance between labour demand and supply rather than a decline in matching efficiency. The Beveridge curve, which captures the relationship between the job vacancy rate and unemployment, shows an improvement in the matching of labour supply and demand over the past years (Figure 2.5).

1. Job vacancies in business economy sectors.

Source: OECD Analytical Database; Eurostat (JVS_Q_NACE2).

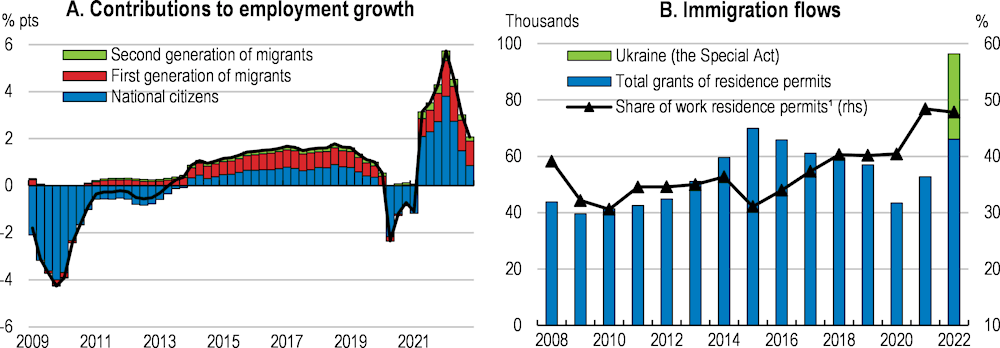

Second, foreign-born workers have significantly contributed to employment growth, both through higher employment of foreign-born residents of Denmark and immigration (Figure 2.6). The employment rate of the foreign-born reached record highs in 2022 and continued to improve from around 66% before the pandemic to 69%, narrowing the gap to natives. After a halt in 2020, migration flows have accelerated significantly, with a relatively high share of labour migration. A record high number of 121,000 people immigrated to Denmark in 2022 (corresponding to around 2% of the Danish population), up from 76,000 in 2021, with net migration at around 58,000 (around 1% of the population). This was partly driven by around 30,000 Ukrainian refugees in that year, with around half finding employment by mid-2023. Around 12.2% of full-time workers in Denmark in 2022 were foreign-born, up from 5.7% in 2008. Of the foreign-born employed in Denmark end 2021, around half came to Denmark primarily for work, while refugees and family reunification account for most of the other half (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2022).

1. Includes Work and EU/EEA, Wage-earners residence permits.

Source: Statistics Denmark and OECD calculations.

The capacity to mobilise the domestic work force and to increase international recruitment to respond to growing labour demand likely helped to contain labour cost growth (Figure 2.7, Panel A). Labour shortages risk adding to supply-driven inflationary pressures and can trigger competitiveness losses as a result, but wages have not fully adjusted to strong inflation in 2021 and 2022 and indeed decreased significantly in real terms (see Chapter 1). Following the latest collective bargaining in spring 2023, wage growth is expected to accelerate but to be contained in the coming years. Nominal wages are set to accelerate to compensate for past high inflation and increase around 9-10% over the next two years (OECD, 2023a). Estimates of the impact of labour market tightness on wages suggest that the wage setting curve has been relatively flat at the firm level over the past years (Hoeck, 2022). However, there are large discrepancies across sectors, with a strong acceleration of labour cost inflation in construction and information and communication, both of which have performed very well with a strong demand for skills (Figure 2.7, Panel B).

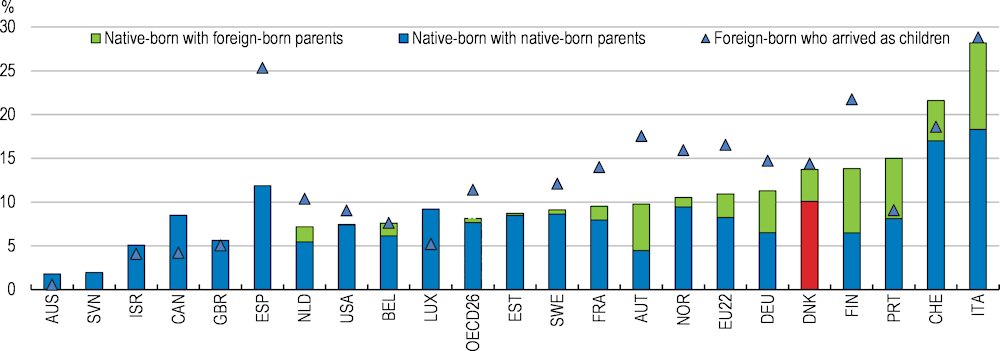

International comparisons suggest Denmark still has room to raise employment rates as, despite large improvements over the past years, they remain below levels seen in the best performing OECD countries (Figure 2.1, Panel B). There is substantial room to mobilise migrants more fully (Figure 2.8). While the composition of migrants can vary across countries and Denmark has seen the employment rate for the foreign-born population increase by 12.1 percentage points since 2015, Denmark lags the best performing countries with respect to the employment of first-generation immigrants and even more so for second-generation children when both parents are immigrants, who have an employment rate barely above the EU average (Figure 2.8, Panel B).

There is also room to improve employment rates among native workers. Prime age native workers exhibit unremarkable employment rates, just above the EU average (Figure 2.8, Panel C), and they have improved very little over the past years, increasing by only 0.4 percentage points since 2015. Employment rates of the older workforce have improved significantly lately, increasing by 7.8 percentage for 50-64 year olds since 2015, but there is still scope to increase employment rates further, particularly for those aged 65 and above (Figure 2.8, Panel C). The employment rate of those aged 15-24 years is high relative to the average but hides a relatively high incidence of part-time work (Figure 2.8, Panel C). There are also 6.7% of 15-24 year olds not in labour or education, below the EU average of 9.6%, but above Norway, Sweden, and Iceland. 23% of these are the children of parents with low skill levels, which emphasises the need for skills development, as Denmark also exhibits a larger employment gap relative to the best performing countries for the lowest educated (Figure 2.8, Panel D).

While employment rates are high, average working hours per worker are among the lowest in the OECD, alongside Germany and the Netherlands. Higher employment rates are typically associated with lower average hours as more people enter into the labour force and work part-time. The incidence of part-time work is higher in Denmark than in many OECD countries, and slightly higher than in the other Nordics (Figure 2.9, Panel A). There is a high incidence of part-time work amongst the young because most students work part-time (normally around 10-20 hours a week) alongside their studies. “Flex jobs”, a flexible job arrangement with reduced hours for those with limited work capacity, also adds to use of part-time (93,381 people were in flex jobs in 2022). The scheme allows those with disabilities and approved for flex jobs to maintain contact with the job market by working a limited number of hours. In addition to their agreed wage, a flexible salary allowance of no more than 98% of the maximum unemployment payment is paid from the municipality. Like in other OECD countries, women are overrepresented among part-time workers. Around 22% of employed women worked part-time in 2021, almost double the share of men (13%). Around 90% of part-time work was reported as voluntary in 2021, which points towards measures to remove distortions that may create a bias towards not working full time.

Working hours in full time jobs are amongst the lowest in the OECD (Figure 2.9). In general, working hours are laid out through collective agreements, with most agreements specifying a normal working week of 37 hours. This may reflect social preferences, as well as factors such as taxation. The average annual hours worked in Denmark is 1,363 hours, the second lowest in the OECD, and significantly lower than the OECD average of 1,716 hours with the incidence of part-time work also playing a role. Working hours have been on a declining trend over the past decade (Figure 2.9, Panel C). The gender gap in paid working hours slightly exceeds the EU and the Nordic average: on full time jobs, women work around two hours less than men per week on average (Figure 2.9, Panel B). However, like in most OECD countries, Danish women work on average one hour more per day on unpaid work, such as housework and childcare, than men (Bonke and Christensen, 2018; OECD, 2020c). Working hours for full-time workers in public services are also shorter: on average, public-sector employees work around 2 hours less per week compared to private sector employees. The abolition of a public holiday, the Great Prayer Day, from 2024 aims at raising worked hours per year and is estimated to increase labour supply between 0.14% and 0.34% depending on the methodology used (Minasyan, 2023). However, the positive impact of this measure might be muted in the long run should workers adjust working hours to restore their leisure time (DORS, 2023).

Difference in employment rates

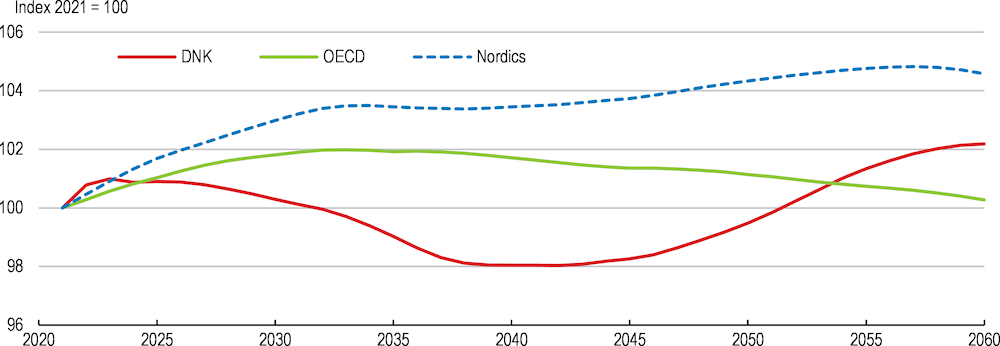

Population ageing is accelerating, slowing growth of the labour force and creating new pressures. The growth of the working age population has decelerated significantly over the past decade and is projected to turn negative between 2025 and 2040 before rebounding (Figure 2.10). The share of people close to retirement age in the working age population, people aged between 60 and 69, is projected to increase by around 2 percentage points by 2030. Increases in employment rates among 55+ year-olds, which is important due to population ageing, has however contributed to the fast ageing of employees (Figure 2.10), Greater job separation due to retirement implies an increase in job openings in all occupations by 2030 (CEDEFOP, 2018a). As working age cohorts decline and the dependency ratio increases, the ageing of the workforce will weigh on growth potential and complicate the recruitment needed to replace people retiring over the coming years.

15-69 year-old population projections

Note: Population projections based on the “Main variant” scenario.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022). World Population Prospects 2022, Online Edition; and OECD Population projections database.

Reforms have been implemented to increase the effective retirement age and somewhat offset the effect of population ageing by raising labour supply among older workers (Box 2.1). The indexation of the retirement age to life expectancy is designed to mitigate the impact of growing longevity by increasing the length of working lives. The labour force is projected to continue growing as a result, but the annual growth rate is projected to decelerate significantly from around 0.7% over the past ten years to around 0.2% by 2040 (Danish Ministry of Finance, 2022). In addition, labour supply growth could fall below expectations, if the effective retirement age and older workers’ employment rates do not increase as fast as projected. Work capacity might not increase in line with life expectancy, especially in physically demanding occupations and self-financed early retirement could increase. This poses a risk to growth potential and for the sustainability of public finances (see Chapter 1).

The share of mature workers, defined as those aged 55+, has increased significantly since 1990, from 11% to 22% in 2021. It is set to continue to rise to around 26% by 2050 and to remain high as working lives are prolonged due to improving longevity and future increases in the effective retirement age.

Decomposing this increasing share of older workers shows that since 2015, the acceleration of the ageing of the workforce has mainly been driven by higher employment rates among older workers, rather than increases in the number of people in these groups. This has particularly been the case in industry as opposed to the public sector, which suggests a stronger retention capacity of older workers in industry. The employment rates of older workers contributed to the ageing of the workforce to a lesser degree in the public sector. Compared to a set of European countries, ageing has been faster in Denmark in most sectors, but not in public services, such as administration and education.

Using register and micro data allows for the identification of discrepancies across sectors and occupations on the degree and the pace of ageing in Denmark. While the share of older workers increased in aggregate by around 5 percentage points since 2010, this change was more pronounced in occupations with lower levels of qualifications when compared to the national average. Pension adequacy has not deteriorated, but the use of early retirement has declined, for which manual workers were over-represented.

The share of workers aged 55+ among employees is relatively high and is rising fast in occupations with acute recruitment difficulties, such as the healthcare and ICT sectors, as well as among manual workers in manufacturing and transport (operators, assembly, and transport workers).

Comparing age distributions across countries points to comparable ageing challenges in neighbouring countries, thus potential high competition for mobile skilled workers. Some occupations stand out as having a more pronounced and faster ageing both by Danish and international standards, including care workers, drivers, plant and machine operators, and science and engineering associate professionals.

A simple cross-country econometric analysis finds that occupations with higher shares of women, lower educated employees and more remote work have an above average share of older workers. By contrast, occupations with a strong employment growth, higher share of foreign-born workers and low job tenure have a lower share of older workers. No correlation was found with automation risks measured following Quintini and Nedelkoska (2018). Other empirical work finds that the share of older workers is not correlated with whether the occupation is green or brown (Causa et al., 2023).

Source: Own calculations based on EU LFS data.

Despite intensifying immigration over the past decade, Denmark has a relatively small foreign-born population compared to most OECD countries (Figure 2.11). Restrictive migration policy plays a role. Most foreign workers are from the EU as they can reside and work in Denmark under EU law (OECD, 2021a). The largest groups of immigrants are from Poland, Romania and Ukraine. The number of Ukrainian immigrants working in Denmark increased rapidly following the Russian invasion. Many of these Ukrainian immigrants are only entitled to a temporary residence permit under the Special Act, the Danish law on temporary residence permits for refugees from Ukraine.

Third-country foreign workers face stringent entry conditions based on strict employment, salary level or specific profession criteria. The minimum annual salary to recruit a non-EU resident is generally high (465,000 DKK, equivalent to around 87% of the average wage) and hinders recruitment of medium-skilled or newly trained employees. Since 2023, the pay limit was reduced to 375,000 DKK when the register-based unemployment rate is below 3.75%. The Positive List schemes for skilled workers and highly educated workers, that allow non-EU applicants to apply for residence and work permits in professions experiencing labour shortages, do not extend to all professions under stress. As of July 2023, the Positive List for People with a Higher Education includes 30 job titles, while the Positive List for Skilled Work includes 36, down from 46 job titles each for both lists in 2022.

Share of foreign-born population, 2021 or latest year

Recent policy changes have relaxed work visa rules for highly skilled migrants. The new lower pay limit will apply so long as seasonally adjusted register-based unemployment is below 3.75%. Changes also extended the post-study visa stay of foreign students after graduation; extended the Fast Track scheme, which allows certified companies to employ foreign nationals who meet certain conditions more quickly and easily, to companies with at least 10 employees instead of 20; and the set up a start-up visa scheme for entrepreneurs.

However, more could be done to facilitate international recruitments to meet skills shortages. The pay limit remains high, at around 70% of the average wage, and it should not be linked so tightly to overall demand conditions. The government plans to introduce a new scheme with lower limits for certified companies, but an annual quota will be set on the number of permits. The pay limit should also include other salary benefits, such as employee share options often used by start-ups. The Positive List for high skilled workers should be expanded to include experience-based knowledge in shortage areas. Recognition and validation of qualifications acquired abroad can be affected by uncertainty and lack of information regarding foreign educational systems. Denmark could take inspiration from Germany’s introduction of the Skilled Workers Immigration Act (Fachkräfteeinwanderungsgesetz) to allow medium-skilled migrants to be recruited from non-EU countries in specific occupations, including facilitating their access to training and reducing visa processing times (Box 2.2).

The Skilled Workers Immigration Act (Fachkräfteeinwanderungsgesetz) came into force in March 2020 to allow medium-skilled migrants to be recruited from non-European Economic Area countries in specific occupations. The Federal Ministry of the Interior issued 30,000 visas over the first year of the policy. The Act permits migrants with recognised qualifications to search and apply for these specific jobs, thereby making it easier for those with vocational training and/or practical professional knowledge to immigrate to Germany. The Act also aimed to reduce red tape and bureaucracy, while opening migrants’ access to training. For example, the requirement on employers to prove there is no domestic worker who could fill the role was removed.

Further changes were agreed in March 2023 to further relax the rules and speed up the process. Many medium-skilled migrants come to Germany under apprenticeship contracts, therefore the strict criteria for the recognition of skills acquired abroad was relaxed. The requirement for a professional qualification in a specific field was replaced by two years of educational experience plus two years of professional experience. Skilled workers can start working in Germany even while their qualifications are being certified. A new feature of the reform was also added, the points-based Opportunity Card (Chancenkarte), which allows non-EU migrants to enter Germany even without a job offer if they meet certain criteria including qualifications, work experience, German language proficiency, age, and a connection to Germany. Skilled workers can obtain a permanent settlement permit (Niederlassungserlaubnis) after three years compared to the previous four-year requirement. The reform also waives foreign degree recognition in non-regulated professions, extends the list of occupations that qualify for a residence permit and repeals the labour market tests for apprenticeships.

Source: OECD (2023) OECD Economic Surveys: Germany 2023.

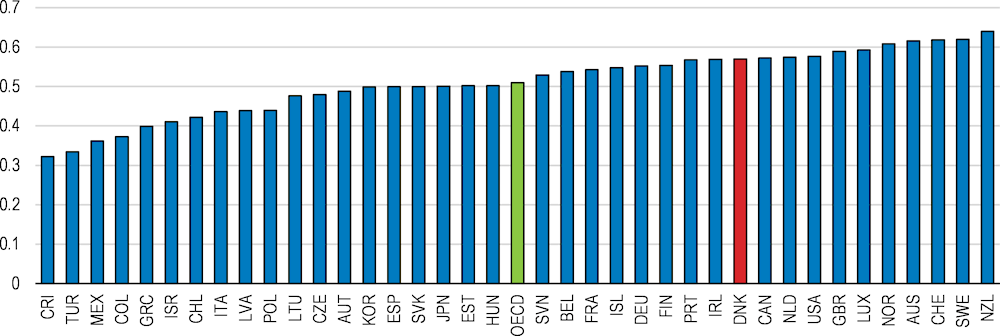

Incentives to attract high-skilled foreign workers should be strengthened given growing competition from other European economies that also face labour shortages. Frequent rule changes, with often increasingly difficult residency rules both for permanent residency and citizenship, create insecurity and uncertainty for migrants or potential migrants, a key factor in the attractiveness of a country for high-skilled workers (OECD, 2023i). The immigration law has been amended 135 times between 2002 to 2019: these numerous changes lead to legal ambiguity and unpredictability for migrants and firms alike. More stable and certain pathways to permanent settlement would increase the attractiveness of Denmark and create a more welcoming environment for highly skilled workers, particularly as labour markets tighten in the countries from which foreign employees are recruited (Hanushek et al., 2015). The 2023 OECD Indicators of Talent Attractiveness, which measures the capacity to attract and retain talented migrants accounting for policies and practices for admission, ranked Denmark 11th in overall attractiveness to highly skilled migrants, well behind the leading countries (Figure 2.12).

Administrative burdens on residency should be reduced as these are complex and lengthy and further reduce Denmark’s attractiveness (OECD, 2019a). It is thus welcome that the government plans to allocate additional funds to ensure faster and more efficient case processing. Denmark could learn from a successful Finish experiment in which foreign tech workers and their families were encouraged to temporarily move to Finland. All necessary paperwork and logistics, such as accommodation and school places, were fixed in advance. The scheme proved extremely successful with 5300 applications, of which 60 were investors and 800 entrepreneurs wanting to start their own business.

Talent Attractiveness index for highly educated workers, 0 = worst and 1 = best, 2023

Note: The OECD Indicators of Talent Attractiveness (ITA) are grouped in seven dimensions, each representing a distinct aspect of talent attractiveness: (1) quality of opportunities, (2) income and tax, (3) future prospects, (4) family environment, (5) skills environment, (6) inclusiveness, and (7) quality of life. An optional health dimension is available to users (8) health system performance.

Source: OECD, Talent attractiveness 2023 - https://www.oecd.org/migration/talent-attractiveness.

Adjustments to a range of policies are needed to reduce work disincentives and address shortages. This section proposes avenues to address barriers to longer working hours and lives. It presents policies to sustain labour force participation, including reducing labour taxation that disincentives working full-time and retiring later, and adapting the work environment to ensure those with work capacity can remain in the labour market. It then considers the issue of entry into the labour market when young, improving the integration of migrants, and improving access to mental health services.

The Danish tax and benefit system is based on a solid tax-financed welfare state, providing quality public services with elevated income replacement rates for those out of work, but subject to strong activation and training requirements. Activation, search, and training services are run through municipal job centres, where DKK 5 billion of the national DKK 12 billion budget for employment schemes is spent.

The government plans to reform public employment services to achieve large efficiency gains and reduce the cost of activation policies by more than a quarter. This includes abolishing the local job centres. Details of their replacement are yet unknown, but an expert group has been tasked with reviewing the employment system and reporting by June 2024. Job centres have successfully assisted the unemployed in their job search, including achieving necessary education and upskilling, but this has come at high cost. Denmark has the highest amount of spending on active labour market policies in the OECD at more than 2% of GDP, despite the low level of unemployment. Ineffective programmes should be phased out as recommended in past Economic Surveys (OECD, 2019, 2021), but high-quality support for job seekers must be maintained. Benefits of the reform will critically depend on its design and careful monitoring is needed. Denmark could learn lessons from Sweden, the United Kingdom and Australia who have sought to achieve efficiency savings via increased digitisation of services and the use of private providers. Privately contracted services can lead to significant efficiency gains, but the design must ensure incentives are aligned to provide quality services to all jobseekers, including in less profitable delivery areas (Box 2.3).

Sweden

Since 2019, Sweden has embarked on a major reform of its public employment service, shifting from providing in-house services towards an increased use of private providers. This included a significant downscaling of local physical presence across Sweden, a reduction in the number of staff, and increasing digitalisation of services.

Outsourcing to private providers was intended to spur innovation and result in better-quality services at a lower cost via encouraging competition in the local area. But creating a market where employment services are largely contracted out requires carefully considering many factors, such as achieving fair and informed competition between providers, ensuring the provision of services at the local level, and creating a suitable outcome-based compensation model. In Sweden, independent providers are paid a daily allowance plus a performance-related payment. This is differentiated based on the jobseeker’s employability to ensure providers do not focus all their attention on those that are closest to the labour market.

A public ratings-based system of providers was introduced to help jobseekers make informed choices. Although it is too early to properly evaluate these reforms, there have been some indications that remote and sparsely populated regions are not being sufficiently covered by private sector providers, due to insufficient incentives to enter non-profitable areas. Simplifying application requirements for providers active in other regions could enhance provision.

United Kingdom

Employment services in the UK are delivered primarily through “Jobcentres Plus”, which operates job centres across the country, and works with a network of contracted providers to deliver a range of employment support measures, such as training, self-employment support, and case management. Enhanced digitisation of services has been occurring since 2016.

Digital platforms are available for online job search and vacancy matching, and free Wi-Fi and access to computers have been made available at job centres since 2018. Jobseekers are expected to use digital services through their online account, for example to message their work coach, upload documents, or record job search evidence. Those that find it difficult to use of digital services receive assisted digital support. As part of the digitisation process, over 100 local jobcentres (around 15%) were closed.

Nevertheless, mandatory personal attendance at Jobcentres Plus interviews remains a core requirement to receive Universal Credit and most other working-age benefits. A Department for Work and Pensions service and experience survey following digitisation showed that many found it convenient to access services online, although those with poor levels of literacy or digital skills found the transition quite challenging (DWP, 2018).

Australia

A new online employment services model, Workforce Australia, was implemented during the summer of 2022 to help reduce the caseload for providers and allow for more emphasis on jobseekers that are furthest away from the labour market. Jobseekers sign up either online or through the Assisted Customer Claim call centre and are referred to the appropriate employment service based on an online or telephone interview: digitally literate job ready jobseekers continue to manage their job search and reporting requirements via an online self-service tool; those that require some skills training enter the “digital plus” stream where they can receive additional services via a contracted provider; and those that face significant barriers to work enter the “enhanced services stream” and receive full in-person support. Aligning incentives between contracted providers and the needs of all jobseekers has been the greatest challenge, with private providers often focusing their efforts on the lowest cost jobseekers.

Online services are supported by safeguards, including assistance from a Digital Services Contact Centre and the ability for jobseekers to choose to transfer to a contracted provider. If jobseekers do not find work or appropriate training within 12 months, they are moved to independent provider services to receive more personalised and intensive case management. In September 2022, 82.3% of individuals who used Online Employment Services were employed three months later, and 89.7% were either working, studying or both.

Source: OECD (2023i) Organisation of public employment services at the local level in Sweden.

As marginal effective labour taxation is high and the wage distribution compressed, relatively low financial gains for workers can weaken full participation in the labour market, especially for second earners and homeowners (Bingley, 2018) and reduce incentives to invest in education. Lower income taxation is found to correlate with higher average working hours, primarily caused by employees changing jobs to positions with higher agreed working hours (Sigaard, 2023). Financial disincentives to work measured by the ratio of transfers people received while not working and labour income have declined since 2009, partly due to past tax reforms and reductions in social assistance benefits in real terms (Danish Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2023a). The January 2022 reform package, “Denmark can do more II”, includes measures to increase labour supply by strengthening work incentives, with an objective to increase by around 12,000 the number of people in work by 2030, an increase of around 0.4% in employment. For instance, in 2022, the unemployment benefits received by recent graduates under 30 years old were reduced by more than EUR 500 (to around EUR 1275) after the first three months in unemployment and their duration to one year (from two).

A reform initiated in 2023 will reduce labour income taxation (Box 2.4). The marginal tax rates paid by employees on labour income, which mostly consists of the personal income tax as social security contributions are low in Denmark, are relatively high by international standards (Figure 2.13). The reform includes increases in the earned income tax credit, which should reduce the marginal tax on earned income by 0.5 percentage points for those earning less than the average wage. At the same time, marginal effective tax rates will remain well above OECD average and could be reduced further by increasing property taxation (see Chapter 1).

Net personal marginal tax rates, principal earner, 2021

Note: The Marginal Effective Tax Rate (METR) measures how much of additional earnings are taxed away through the combined effect of increasing tax and decreasing benefit. It includes the personal income taxes, social security contributions paid by employees, social assistance, temporary in-work benefits and housing benefits.

Source: OECD Taxing wages comparative tables.

As social security contributions are low by OECD standards, the personal income taxation mostly consists of the State income tax and the municipal tax (individual taxation). The impact of the 2023 reform of the personal income tax on the marginal effective tax rate is illustrated in Figure 2.14. The system incorporating the reforms can be summarised as:

An 8% labour market contribution levy is first deducted from all taxpayers' earned income.

The State tax is levied at one of two rates, 12.06% and 15% for income above DKK 618 400 before deduction (1.3 times the average wage).

With the reform, the tax rate would be adjusted as follows:

For income between DKK 618 400 and DKK 750 000 before deduction (1.6 times the average wage), the tax rate is reduced by 7.5 percentage points

For income between DKK 750 000 and DKK 2.5 million, the tax rate is unchanged

For income above DKK 2.5 million before deduction (5.4 times the average wage), the tax rate increases by 5 percentage points, effectively introducing a new top rate.

Local income taxes are levied by municipalities with the average rate at around 25% (they vary from 23.1% to 26.3% in 2023)

The top marginal tax rate is capped. If the marginal tax rate including local tax exceeds 52.07%, the top tax bracket rate is reduced by the difference between the marginal tax rate and 52.07%. With the reform, the cap will be reduced by 7.5 percentage points to 44.57%, but the additional taxes for incomes above DKK 0.75 million will not be subject to the cap.

Marginal tax rates on labour income by level of income

Working taxpayers receive an employment allowance of 10.65% of earned income to a maximum of DKK 44,800 when calculating local taxable income. Single parents get an extra employment allowance of 6.25% with a maximum allowance of DKK 24,400. With the reform, the allowance rate will increase by 2.1 percentage points (and 5.25 percentage points for single parents) and the maximum deductible amount by around 25% (and 84% for single parents). An additional employment allowance of 1.4% from 2026 increasing to 3.9% from 2030 will be introduced for senior workers two years or less before their legal retirement age. The maximum additional allowance for senior workers is DKK 5,400 from 2026 and will be increased to DKK 14,800 in 2029 and DKK 15,200 in 2030 (2023 income level).

Allowances are provided to working taxpayers and for pension contributions (with a cap). Some work-related expenses are deductible from taxable income (with caps), such as contributions to unemployment insurance and trade unions, expenses relating to transportation to the workplace, contributions/premiums paid to private pension saving plans (except lump sum savings).

A tax-free lump-sum transfer is allocated to people working at least 1,560 hours per year (30 hours per week) the first two years after the legal retirement age. The tax-free transfer amounts to DKK 45,415 the first year and DKK 27,033 the second year. With the 2023 tax reform the tax-free transfer will be increased by 11 percent in 2026 and by around 30 percent in 2029.

Source: OECD (2023f), Danish Ministry of Taxation (2023)

As recommended in past Economic Surveys of Denmark (OECD, 2019a; OECD, 2021a), the reform will cut the personal income tax rate for upper middle-class households by adding a new tax bracket for incomes up to 1.6 times the average wage. The top income tax rate is currently paid at a relatively low level of income by international standards (around 1.3 times the average wage). The top tax rate will also increase by 5 percentage points and apply to revenues above DKK 2.5 million (more than five times the average wage), impacting only a limited number of taxpayers and likely have a very modest negative impact on labour supply. Overall, this reform would increase financial gains from work for most taxpayers (Figure 2.14) and is estimated to boost employment by around 5 000 full time individuals by 2030 (Danish Ministry of Taxation, 2023). The effects of the reform on the labour supply could be lower than expected, as small changes in taxation are found to be less successful at changing behaviours (Kleven and Schultz, 2014). The reform is estimated to cost around DKK 6.75 billion (2.4% of GDP), considering the positive impact on higher labour supply on tax revenue.

Raising the top tax rate, which is already among the highest in the OECD, could pose risks to financial incentives and of tax avoidance, but it would only apply to a small number of households. Empirical evidence points to diminishing revenue returns of increasing the effective marginal tax rates that apply at substantially above-average income levels (Akgun et al., 2017). Deepening the gap between the taxation of individual income and corporate income incentivises retained earning strategies and favours incorporation by entrepreneurs, which has been increasing over the past two decades (OECD, 2023b). The Danish tax system (the VSO “corporate tax scheme”) allows business owners to retain earnings and, until earnings are distributed, or capital gains realised, to only pay the corporate tax rate, which at 22% is well below the top marginal income tax rate. Careful assessment and monitoring of the impact of the reform on tax optimisation will be required.

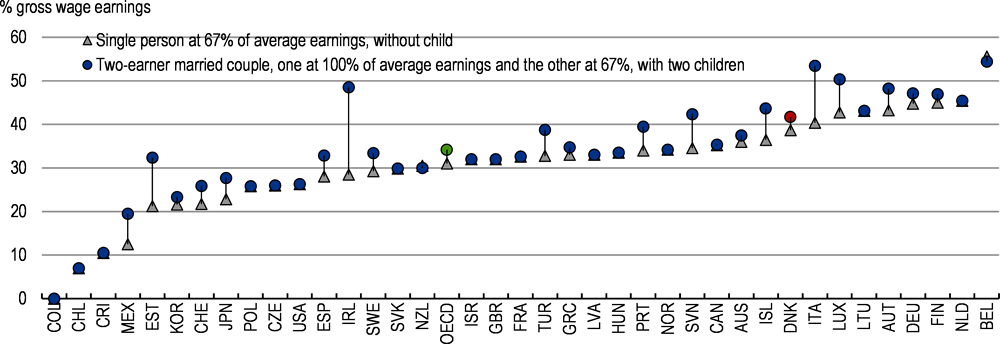

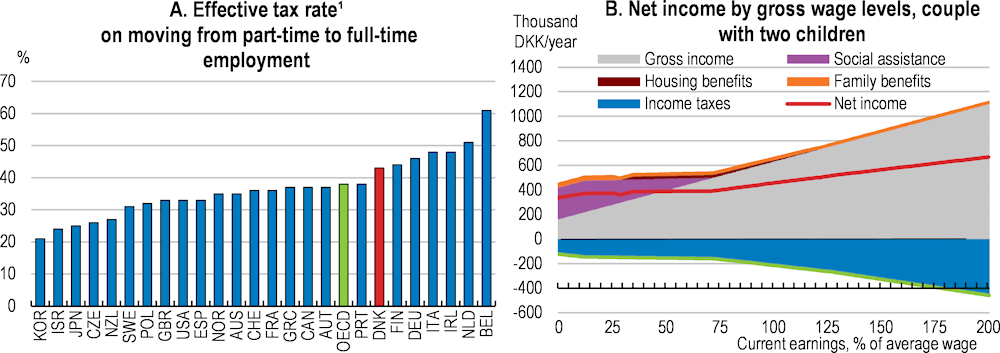

Denmark has a generous and complex benefit system that contributes to reducing inequality to relatively low levels. Despite having strong activation and job search requirements, the system also features some financial disincentives to work. Many benefits are means-tested, including family and housing benefits and some (including social assistance) have a withdrawal rate close to 100%. As a result, low-to middle income families receiving benefits face a high effective marginal tax rate and gain little by raising hours worked (Figure 2.15). The withdrawal of their benefits when income increases significantly reduces their incentives to expand work effort. As stressed in the 2021 Economic Survey, in-work benefits targeted at families earning less than the average wage and receiving means-tested social benefits could be a powerful lever in raising incentives to work longer hours (OECD, 2021a). At the same time, the compressed wage distribution complicates the introduction of such benefits as many people might be eligible for benefits if the tapering was very gradual. The government established a temporary job premium scheme for cash assistance recipients who have received benefit for at least 1 year within the last 3 years. A DKK 5,000 tax-free lump sum will be paid when benefit recipients leave the cash assistance system and are employed for 6 consecutive months. The job premium scheme is set to expire in mid-2024. Its impact should be evaluated, and the measure maintained if it proved effective in raising work effort.

1. Tax rates include personal income taxes, social security contributions paid by employees, social assistance, temporary in-work benefits and housing benefits; Panel A refers to the share of gross earnings in a job that pays the average wage when increasing hours worked from 50% to 100% of full-time employment, for a second earner with two children and a partner working full-time in a job that pays the average wage.

Source: OECD Benefits, Taxes and Wages (database).

Past pension reforms including increasing the legal retirement age and restricting early retirement schemes have contributed to increasing employment rates of older (55+ year old) workers. The statutory retirement age reached 67 in 2022 (and 64 in 2023 for early retirement). The duration of voluntary early retirement programmes has been shortened from five to three years with the minimum age raised in line with the statutory retirement age. These measures coincided with an increase of the employment rate of the affected cohorts by more than 6 percentage points. Like in many other OECD countries, employment rates tend to fall sharply at the legal retirement age.

The Danish pension system is based on a combination of means-tested public pension benefits, quasi-mandatory occupational pension schemes, and private savings. Financial incentives for prolonging working lives when approaching the retirement age are strong and have been reinforced. Drawing down pension savings earlier than three to five years before the legal retirement age is heavily taxed, while pension savings offer tax allowances (see Box 2.4). Since January 2023, means-tested public pensions have been paid independently of a spouse's or cohabitant's earned income. This should help mitigate disincentives to work longer due to a high earning spouse. Furthermore, labour income has been exempted from means testing in the calculation of public pension benefits since 2023. The 2023 personal income tax reform includes an additional employment allowance for workers close to the retirement age and increases in the tax-free lump-sum transfer allocated to those working the first two years after the legal retirement age (see Box 2.4).

The strict indexation mechanism of the legal retirement age should also foster labour supply, with some risks. The statutory retirement ages are adjusted to life expectancy gains every five years, conditional on approval by Parliament. This measure targets an expected retirement period of 14.5 years. As a result, the average pension payment period will be progressively reduced and a person entering the labour market at 22 in 2020 is expected to reach the legal retirement age at 74, the highest in the OECD (see Chapter 1). A reduced length of retirement of future generations can undermine the political acceptability of the indexation and raise incentives for early retirement. Wealthy households with high private savings, large replacement rates and valuable assets may increasingly opt for a self-funded early retirement as the retirement age increases and expected time in retirement diminishes (Box 2.5). Relaxing the indexation rules of legal retirement ages after 2040, without critically undermining fiscal sustainability according to experts’ projections (Pension Commission, 2022), could temper any further lengthening of working lives.

While many efforts are being made across countries to retain older workers in the labour force as the population ages, rising prosperity and shifting attitudes towards work may lead some of them to voluntarily reduce working hours or take early retirement to enjoy more leisure time. In Denmark, compulsory pension savings are high and the comprehensive welfare system mitigates age-related costs, so self-funded voluntary early retirement may seem attractive.

Basic economic theory assumes that individuals optimise their utility over time by consuming goods, services, and leisure when not working. As labour income increases, two opposing forces come into play: the "income effect" may reduce work effort as people demand more leisure, while the "substitution effect" increases it. Models suggest that labour supply may decline after reaching a certain income threshold, known as the backward bend of the labour supply curve. In addition, higher pensions and housing wealth may increase the demand for leisure time as people age.

In practice, retirement decisions hinge on a large range of factors, including labour income, pension savings, available early retirement options, health status, work conditions, and family circumstances. Retirement entitlement strongly predicts early retirement, and wealth demonstrates a clear association with early retirement (Kuhn et al., 2021). Homeownership also increases the likelihood of early retirement, especially in pension systems that allow flexible pension savings withdrawal. Increasing financial incentives to prolong working lives could lead to lower working hours before retirement (Gustafsson, 2021).

In reality, the employment rate of older workers and the effective retirement age has increased significantly over the past decade. Early retirement decisions have been predominantly driven by poor health, low employability, and strenuous working conditions, rather than a desire for leisure (Qvist, 2021).

Nevertheless, an estimated 6,000 individuals chose self-funded early retirement in Denmark in 2022, primarily individuals with substantial personal assets and savings. There is some evidence of similar trends in other countries with high pension savings, such as Australia. However, while most Danes save enough to enjoy a comfortable retirement, ordinary workers typically lack the financial resources to retire early based on their own savings. Financial incentives to continue working are strong. Early withdrawal of assets from programmed withdrawal or life annuity schemes is subject to a fixed 60% tax rate. Many occupational plans do not offer early withdrawal options (OECD, 2018).

Changes in future retirement decisions are difficult to predict, given the multiplicity of underlying factors. Higher interest rates and the maturing of the pension system could lead to self-funded retirement becoming more widespread, particularly among homeowners. Public opinion polls suggest a notable shift in people's attitudes towards work, emphasising self-fulfilment and diminishing personal commitment to work (Haerpfer et al., 2022). Structural transformations, especially in the wake of the pandemic can lead to further changes.

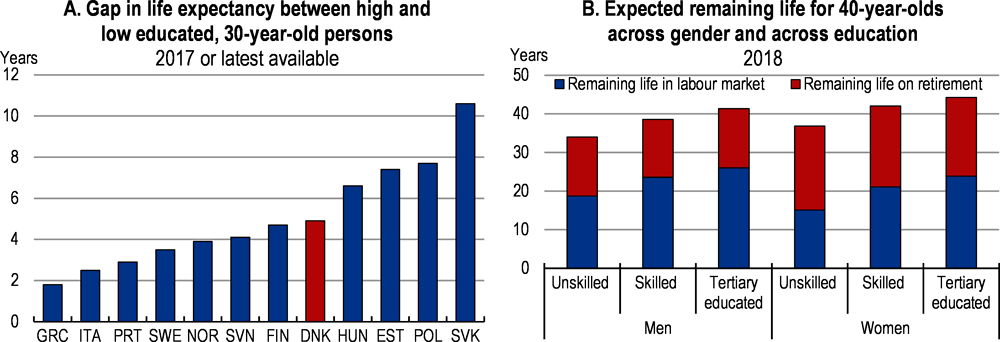

Denmark has four early retirement schemes, including three directed to workers with reduced work capacity and long careers that partly overlap (Box 2.6). Around half of workers currently use early retirement schemes when leaving the labour market. Workers with a low education level have a lower life likelihood than the average (Figure 2.16) and are overrepresented among early retirees. Thanks to the early retirement schemes, they tend to leave the labour market earlier and spend the same time in retirement as more educated workers with longer life expectancies (Figure 2.16). The main cause of early retirement is a poor health status and policies protecting those unable to pursue their careers are an important social safety net. At the same time, there is room to strengthen eligibility criteria to access disability benefits. To receive the senior disability pension for those close to retirement age (Seniorpension), which can be taken up to six years before the legal retirement age, the degree of work capacity is assessed vis-a-vis the latest job of the recipient and eligibility is not reassessed after pension benefits are allocated. Furthermore, the number of younger people receiving disability benefits (Førtidspension) aimed at those above 40 years of age has increased significantly over the past years.

The number of workers eligible for the voluntary early retirement scheme Efterløn will decline substantially in the coming years. The scheme is much less attractive than in the past and the share of less educated workers who are more likely to use the scheme, is falling. Nevertheless, further reforms can limit inflows in alternative pathways to retirement and allow people to work even when age reduces their work capacity. The take up of disability-based pension might increase as the retirement age rises, notably among workers in physically demanding occupations or if life expectancy improvements do not fully translate into longer lives in good health. The government could simplify the early retirement system by aligning the benefit periods of available schemes to three years. With this reform, early retirement would be possible only three years before the legal retirement age (instead of six for the current Seniorpension scheme). Further measures could be taken to ensure those approaching the retirement age with reduced work capacity have access to rehabilitation programmes when needed, and do not face disincentives to continue working or work longer hours, for instance by assessing work capacity vis a vis different types of jobs in the Seniorpension scheme, and reassessing eligibility on a regular basis depending on the distance from the legal retirement age. Encouraging longer working hours in subsidised jobs directed to those with reduced work capacity (flex jobs) could also help. Unintended consequences of restricting the access and generosity of the early retirement scheme, including the use of alternative pathways to early retirement (unemployment benefits) and rising inequality at old age should be carefully monitored. Denmark should also ensure that equality in the length of retirement is preserved and options to retire earlier for workers with a very long contribution history are maintained.

Note: Panel B tertiary educated is the unweighted average of KVU/MVU and LVU.

Source: Eurostat (DEMO_MLEXPECEDU); and Ministry of employment: Pension Commission's report 2022.

Denmark has four main disability and early retirement schemes, two voluntary retirement schemes and two need-based schemes.

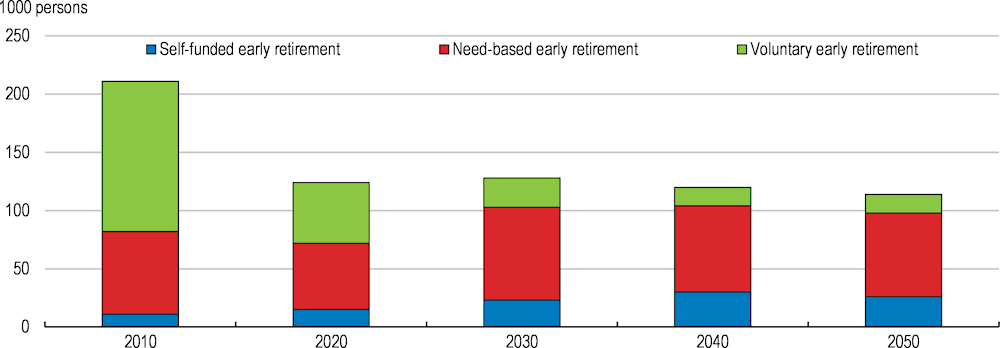

Efterløn is available to members of an unemployment insurance fund who have paid contributions for 30 years and reached the legal age for early retirement (currently 64). The take up of this scheme has declined significantly over the past two decades and is expected to stabilise at very low levels by 2030. A reform in 1998 raised the costs of opting into the scheme; measures in 2012 made it possible to withdraw previous contributions at a tax discount and changed participation in the scheme from an opt-out system to an opt-in system. As the amount paid is capped and reduced by 64% of private pension payments, its return will fall as private pension schemes mature and the number of recipients is set to decline (Figure 2.17)

Tidlig Pension is a flat means-tested benefit awarded to people with very long work records (41-43 years) and low pensions savings up to 3 years before the legal retirement age. The benefit which is close to the basic public pension benefit for singles can be combined with occupational pension benefits. Strong means-testing means that working is financially unattractive. The take up of this scheme has been low so far.

Incidence of early retirement from 0 to 6 years before the legal retirement age, number per 1000 persons

Note: The "Need-based early retirement" category comprises the Seniorpension and the Førtidspension schemes. The "Voluntary early retirement "category comprises the Tidlig Pension and the Efterløn schemes.

Source: Ministry of Finance.

Førtidspension is awarded to people over 40 (with some exceptions) who have a permanent and significantly reduced ability to work.

Seniorpension (introduced in 2020) has the same benefit conditions as Førtidspension but is awarded to people close to retirement age who have a reduced ability to work and a long work history. It gives the opportunity to retire six years before the statutory retirement age if the ability to work is reduced to 15 hours or less per week on the latest job.

Overall, the share of older people using the disability and needs-based pension benefits is projected to remain stable after 2030 despite rising retirement ages (Figure 2.17). Voluntary early retirement is projected to decline, as fewer workers will be eligible for Efterløn and self-funded early retirement is set to remain contained at around 3% in 2040.

Source: Antal modtagere af tilbagetrækningsydelser før folkepensionsalderen fra 2004-2060; A new early pension scheme in Denmark since 1 January 2021 ESPN Flash Report 2021/01; Denmark’s National Reform Programme 2023.

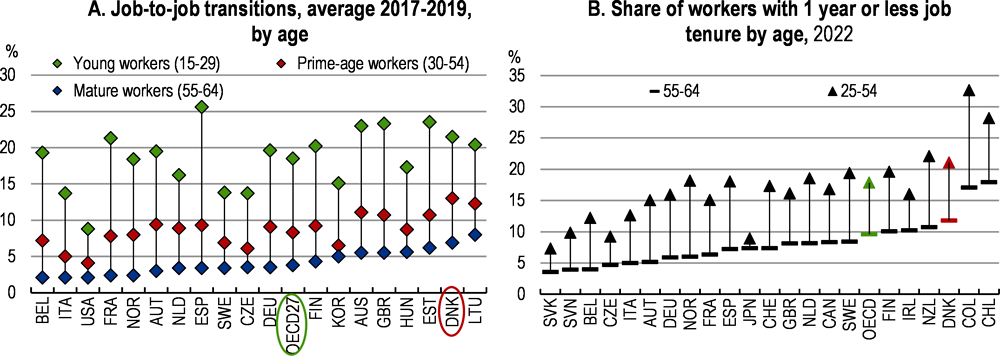

Improving employability of older workers would help to draw talent from workers of all ages and to support mobility in the labour market. Job-to-job mobility is high in Denmark by international standards, including for older workers and even for those with low levels of educational attainment. Demographic changes will affect job transitions because, as in other OECD countries, job mobility tends to decline with age (Figure 2.18), Similar to other countries, hiring rates are also lower for workers aged 60-64 years than for younger ones, but the gap between hiring rates of prime-age and older workers is smaller in some countries such as Japan or some Eastern European countries, suggesting room for improvement in Denmark (Figure 2.18). Survey data show that around a third of Danish retirees would have liked to have worked longer (Ransby, 2020), but older workers report age as a key barrier to finding a job (Thomassen et al., 2022). The proportion of older workers back in the workforce after 12 months of unemployment is significantly lower compared to prime age workers, particularly for 60-64 year-olds.

Source: OECD (2023), Retaining Talent at All Ages, Ageing and Employment Policies, https://doi.org/10.1787/00dbdd06-en; and OECD Job tenure database.

Age is a common reason for work-related discrimination and negative attitudes against older workers is a major barrier in many OECD countries (OECD, 2022d). In 2022, Denmark introduced a law that prevents employers from asking the age of a job applicant. Blind recruitment has been introduced in many countries, such as in the UK and Australian civil service. Nevertheless, Danish firms must accompany this with diversity training programmes to tackle conscious and unconscious biases and stereotypes, as age bias can be found in all parts of the recruitment process (OECD, 2022d). Formal returner or re-entry programmes can also help employers tap into older workers’ skills and experience. These programmes could be directed to older workers at risk of being made redundant or those looking for a career change. Those with a long career break can combine part-time work with training to update outdated skills and overcome difficulties in new work (Hartlapp and Schmid, 2008; Shacklock, Fulop and Hort, 2007). The government could provide guidance to businesses and develop frameworks alongside social partners that firms can tap into. The UK for example, has a formal programme (“The New Deal 50 Plus”) that helps facilitate re-entry through formalised training aimed to boost skill development, employability of workers, and productivity (OECD, 2022d).

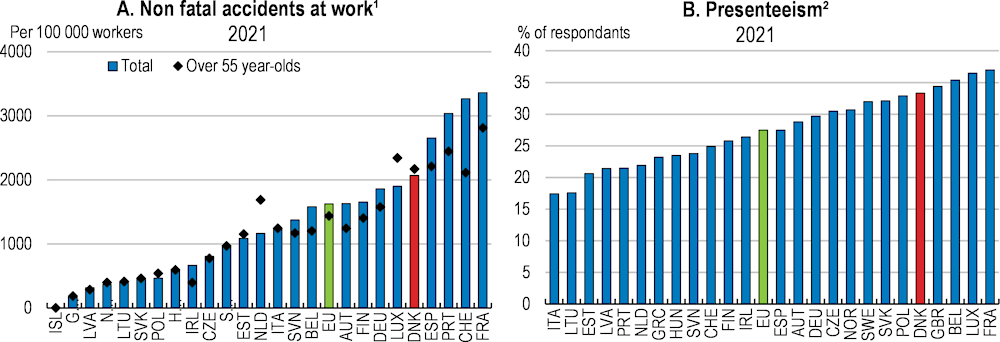

Strengthening the prevention and promotion of healthy lifestyles, and adjusting the workplace is needed to reduce push factors into retirement, particularly for those with physical work demands who tend to retire earlier and have significantly shorter working lives (Qvist, 2021; Pedersen et al., 2020). Denmark has room for improvement in terms of work accidents and “presenteeism”, meaning attending work when unwell (Figure 2.19). Self-reported incidents are high, and, although self-reporting can bias upwards statistics, this is still larger than in other countries with strong welfare states where incentives to report are also high, such as Sweden or Norway. Presenteeism can be detrimental to employee health in the long run, as it can mask serious illness and is often associated with poor working conditions (Saint-Martin, Inanc and Prinz, 2018). In March 2023, a new agreement was established on an improved working environment and strong action against social dumping. This is welcome, as the agreement provides the Danish Working Environment Authority with a historically high level of funding and contains several initiatives to ensure a healthier and safer working life. Changing tasks or work content of older workers to ease the burden of physical work can enable these employees to prolong their careers. Examples of such programmes can be found in Finland and Norway (Box 2.7), where early-intervention models with follow-up actions for those with reduced work ability have found success (OECD, 2022d).

1. Agriculture; industry and construction (except mining); services of the business economy. Iceland data refers to 2020.

2. Individuals who responded “yes’ to the question “Over the past 12 months, have you worked when you were sick?”

Source: Eurostat (HSW_MI01); and Eurofound (2023), European Working Conditions Telephone Survey 2021 dataset, Dublin, https://eurofound.link/ewcts2021data.

A company introduced a comprehensive set of programmes with the aim to increase the average retirement age by six months, the “Life Phase Policy”. The initiative included: management training to cope with the challenges of different age levels in the workforce; annual health monitoring, with dietary and training advice and a special focus on older workers; the option for employees over 62 years old to change working hours according to their needs; and the option to be relocated to less physically demanding jobs after retraining. Following this initiative, the actual retirement age has increased by three years from 63 to 66. In addition, the company has reduced sick leave and very few employees have been declared medically disabled.

A company where the nature of the work is physically demanding and around half of the workers are aged over 45, implemented an early-intervention model with follow-up actions for those with reduced work ability. The interventions are carried out in cooperation with foremen, occupational health services and insurance companies, under the lead of the company’s head of health and well-being. Vocational rehabilitation is provided to allow tasks and/or roles to be adjusted so workers can continue their careers until retirement. It is estimated that, of those that faced early retirement from a physically demanding role, up to two-thirds could remain in place due to vocational rehabilitation. In addition, a smartphone Safety-App was introduced. Employees gain access to ideas on easing the burden of physical work and improving safety at the workplace. The app enables safety observations to be collected via photos to illustrate any shortcomings. This feature is particularly useful for foreign workers who do not speak Finnish. Lastly, workers who are under mental strain are supported and monitored by lifestyle assessment measurements which help employees to recognise stress and identify areas for improvement (physical activity, nutrition, sleep).

Source: OECD (2022d) Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce.

Young people in Denmark leave the school system later than in most other countries. While it has fallen over the past decade, time to graduate in Denmark is among the longest in the OECD, with a high proportion of Danish students entering university later and then doing master’s degrees (Figure 2.20). Students tend to start upper secondary education relatively late compared to peers, as around 30% of pupils opt for an additional academic year (10th grade) before starting high school to discern their chosen path. As recommended by the OECD in 2009, the 10th grade should be only targeted at students with the greatest learning needs (OECD, 2009).

2021

Danish students on average take 5.2 years to complete a bachelor’s and a master’s degree (which 90% of bachelor’s students go on to take), when it is on average around four years in some countries such as the UK, Ireland, or Australia. This slower pace of education does allow many students to undertake part-time work alongside their studies, which adds to the part-time labour supply, and can improve chances of full-time employment post-graduation, but it delays entry into their chosen full-time occupation. A major reform of the tertiary education system in Denmark has been announced with respect to the length of master’s degrees that should accelerate post-study entry into the labour market. A differentiated model of second-cycle education with different options will be implemented, which will include an ambition of 30% of master’s degrees becoming either 1.25 year master’s programmes (75 ECTS) or part-time master’s programmes combined with relevant employment. The reforms will create a model similar to comparable EU countries, such as in the Netherlands where master’s degrees can be one year. While the reform increases flexibility to respond to different labour market needs, through faster training for high-skilled work, and student choice, the effects and outcomes on quality and productivity should be monitored. The Danish Economic Council has pointed to a potentially negative impact on productivity (DTU, 2023; Reform Commission, 2023). In addition, less part-time work and/or internships may be possible given possible increased course intensity, therefore any effects on post-graduation employment rates should be assessed. Lessons from the Dutch experience suggest it is important to carefully consider which programmes are shortened, as some courses are difficult to condense into shorter time periods. Domestic and international recognition for labour market and academic purposes also needs to be assessed to ensure mutual recognition (as achieved by the UK) of the new one-year (90 ECTS) master's degrees as equivalent to a two-year (120 ECTS) master’s, as part of the Bologna process. Ensuring mutual recognition as envisioned in the planned reform will secure the attractiveness of Danish students in international job markets and increase the attractiveness of Denmark for international students.

Generous grants for students play a key role in the length of studies at university. Students who have been resident in Denmark for long enough get free education and a generous living allowance of around USD 1000 per month while they are studying. They are also allowed to take a year of effective leave, with fewer courses, while still receiving their living allowance. Reform is underway, with the maximum grant to be reduced by one year to a maximum of five years. This should help encourage students to opt for a shorter education path, and reduce the prevalence of students who switch subjects, thereby delaying graduation. Nevertheless, the grant and loan system remains very generous by global standards and still higher than in other Nordic countries. A further reduction in support could be considered. This could include widening of the use of student loans, as in Australia or New Zealand, where repayment conditions are linked to subsequent income and labour market status over an extended repayment period, and as recommended by the Reform Commission for master’s degrees. Such a reform could also enhance the incentives to choose educational fields in greater demand and with higher wages.

Denmark has a comprehensive integration policy for foreign-born people focused on labour market participation, but there is scope for improvement. Implementation of integration policy is decentralised to the municipalities, which allows policies to be interpreted and adapted to local circumstances, but as highlighted in the 2021 Economic Survey, this has led to variable quality and success (OECD, 2021a; European Commission, 2021c; Jakobsen et al., 2021). The latest Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX), which measures immigration policies across 56 countries and identifies links between those policies, outcomes, and public opinion, ranked Denmark 26th among OECD countries for its integration policies (Figure 2.21). Denmark was one of the few countries whose index worsened from the previous exercise (Migrant Integration Policy Index, 2020).

Quality of integration policies for immigrants, 0 = worst and 100 = best, 2019

Special allowances were made for Ukrainian refugees with the passing of the Special Act in March 2022. This law allowed Ukrainians to bypass the asylum system and speed up obtaining a two-year residency permit, alongside employment and social assistance. As of 31 July 2023, 37,942 Ukrainians had received residency permits under the special law, and 29,077 are registered as residing in a municipality. Once registered, Ukrainian refugees must take Danish-language classes and actively seek employment to receive around USD 800 per month as well as other social assistance, such as housing and health care. Residence is valid until 17 March 2024, with the possibility to extend for one-year only. Further extensions would require an application for asylum or a residence permit on other grounds. The Special Act is scheduled to expire in March 2025.

Municipalities see insufficient Danish language skills as one of the greatest barriers facing first-generation unemployed migrants (Jakobsen et al., 2021), including Ukrainian refugees, and Denmark’s focus on integration through rapid employment can crowd out language learning (Damm et al., 2022b). Language skills are a prerequisite for integration into the local community and workplace, and the single most important determinant for labour market integration (OECD, 2021h). Studies have shown that language programmes are crucial to enhanced employment probabilities, and particularly in the longer-term where most effects are found to materialise (Arendt et al. 2021). The beneficial effects are also found to extend to the children of migrants (Foged, 2023). While Denmark’s integration programme combines language learning with job training, evidence has shown that once a job is secured, the probability of engaging and finishing the language course is much reduced, damaging longer-term opportunities (European Commission, 2022). On average, refugees who secured a job within their first four years in Denmark were likely to be employed in jobs with very low language comprehension requirements. In 2022, refugees made up around 28% of all immigrants, although this was buoyed by the large number of Ukrainians. Only 31% of the foreign-born who moved to Denmark in 2021 started language lessons, although this may reflect the ability to use their English language skills. By contrast, in Sweden and Norway, education is more highly prioritised, and language learners receive financial assistance that is conditional upon course attendance and complementary with paid work (OECD, 2021h). Two to three times as many newly arrived migrants enter education compared to Denmark. Denmark should place a greater emphasis on language-learning as the primary pillar of its integration strategy. Municipalities should increase efforts to follow up on students who either do not take up the offer of lessons or drop out, and language centres should be empowered to do so as well. Denmark could also reconsider the rule that prevents the foreign-born from obtaining free language lessons after five years.

Foreign-born people living in Denmark for less than 9 of the last 10 years (from non-EU countries) receive integration benefits whose amount are lower than regular social assistance benefits, conditioned to the participation to integration and activation programmes (Martisen, 2020). Past reforms reducing social assistance for migrants had a mixed effect on employment rates, but increased poverty risks (Dustmann et al., 2023). An increased work obligation of 37 hours per week will be introduced from January 2025 for migrants receiving cash benefits. The estimated effects of this measure on labour supply are subdued (250 full time jobs, Ministry of Finance, 2021) and implementation difficult and costly. Job centres have not been able to find adequate jobs, especially for people with weak attachment to the labour market, as they have been unable to support migrants to meet the current activation criteria. Furthermore, there is little evidence of the positive impact of imposing work requirements (European Commission, 2021c).

Most migrants obtain their qualifications abroad, but the limited transferability of these qualifications and skills restricts their labour market integration. Analysis by one of the larger Danish labour unions, Faglig Fælles Forbund (3F), found that half of those overqualified for unskilled jobs were migrants with higher education from their home country (Myklebust, 2021). Foreign qualifications, particularly those from non-OECD countries, do not have the same signaling effect as domestic qualifications, partly due to employer uncertainty and lack of information regarding foreign education and training systems, and (presumed) poorer-performing qualification systems abroad (OECD, 2017). The Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science offers assessments of all levels of educational qualifications. It specifies what a person’s foreign qualification corresponds to in Denmark, which educational level and, if possible, which field of education. The assessment is free of charge and takes around 2 months once the required documentation is received. Early detection mechanisms could be fostered to identify individuals whose foreign-acquired skills and qualifications can be easily supplemented to provide formal qualification in fields where labour shortages are the most acute. The Netherlands, for instance, matches the level of education previously obtained in the country of origin with the Dutch requirements and indicates the number of additional courses needed to obtain an equivalent professional degree (OECD, 2023g). To assess non-formalised skills, obtained for example through work experience, Denmark could take inspiration from Germany and Austria where tools exist that can be used to assess competence. The German “myskills” assessment tool, for instance, uses online identification tests to assess various specific skills that can be transferred to the practical working environment (OECD, 2020b). Online platforms have great potential to facilitate matching, particularly for migrants, as they lack home country specific networks and social capital, but these platforms must be designed in a way that is both accessible and accounts for the specific challenges faced by migrants, employers, and public employment services.