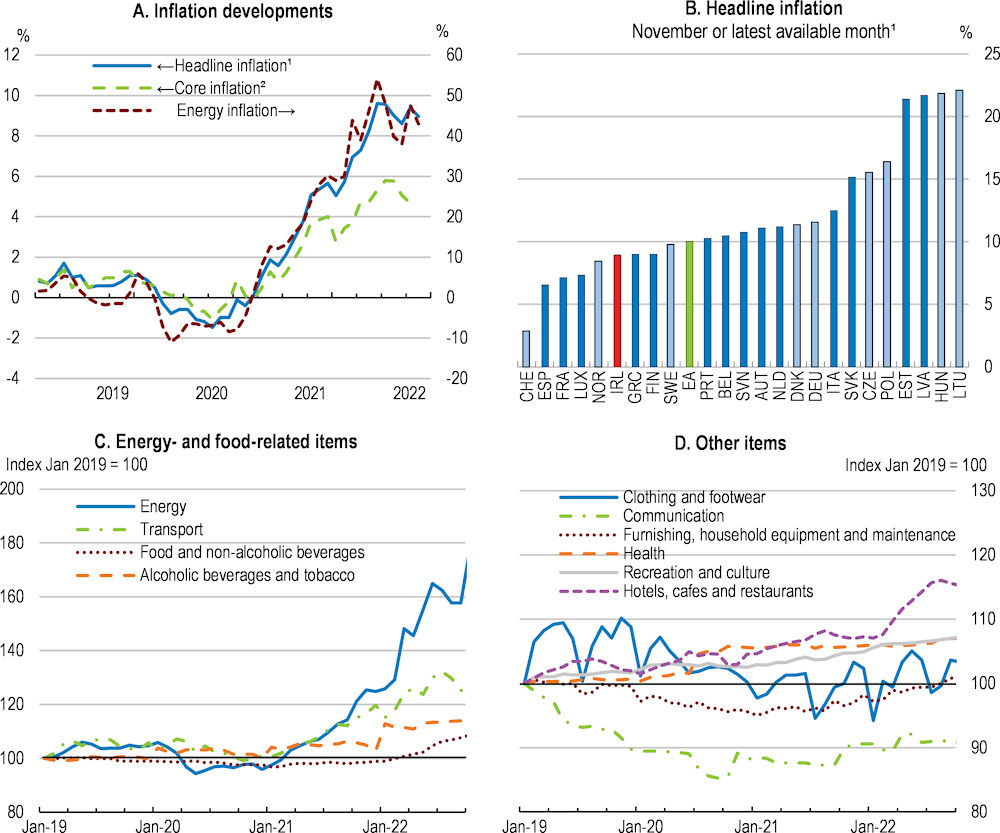

In recent decades, Ireland made impressive strides in developing its economy and raising living standards. This progress has allowed the economy to weather the COVID-19 pandemic and cope effectively with the repercussions from Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. The economy has recovered, but inflationary pressures emerged and while the outlook is favourable, risks are tilted to the downside. The financial sector appears to have withstood the recent shocks, but faces some structural problems, including high legacy mortgage arrears. Fiscal policy had enough room to react to the crises forcefully and shield households and businesses from the full weight of the shocks. A number of pressures will affect fiscal policy in the short run and its sustainability over a longer horizon, including ageing, ensuring adequate supply of affordable housing, and combatting climate change. Labour force participation is still weak for those with lower education attainment and rising house prices are creating affordability concerns. The government has launched an ambitious Housing for All initiative to boost residential accommodation, which will require action to enable a stronger supply response. Ireland did not meet its 2020 emission reduction target. A major plank of abatement policy is the establishment of carbon budgets and sectoral emissions ceilings. The agriculture sector presents particular difficulties for abatement.

OECD Economic Surveys: Ireland 2022

1. Key Policy Insights

Abstract

1.1. Having withstood the COVID-19 shock, the economy faces further challenges

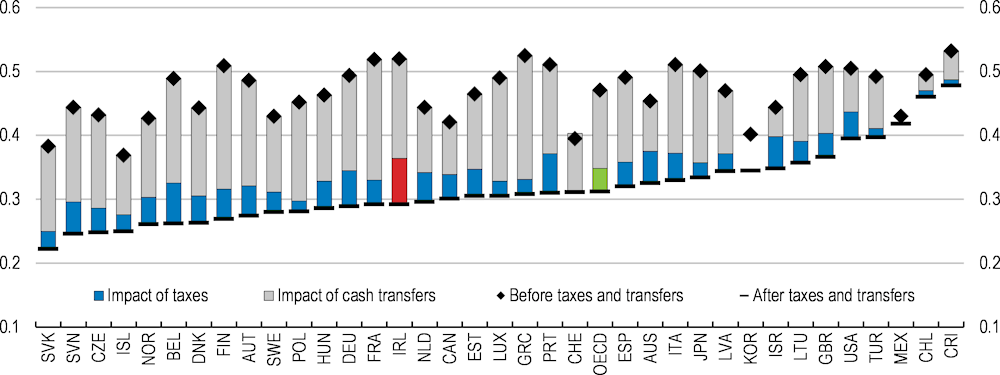

In recent decades, Ireland made impressive strides in developing its economy and raising living standards. Life expectancy at birth is now among the highest in the OECD, from relatively low levels in the 1990s, and the population’s self-reported health status was the best in the European Union in 2019. Thanks to a highly redistributive tax and transfer system, inequalities in disposable income are limited. The gap between the highest and lowest disposable incomes, as well as measures of poverty rates, are among the smallest in the OECD. Moreover, education is high quality with limited impact of socio-economic status. The relatively-young and well-educated population has been a key pull factor in the country’s successful strategy to attract foreign direct investment, together with a supportive business environment.

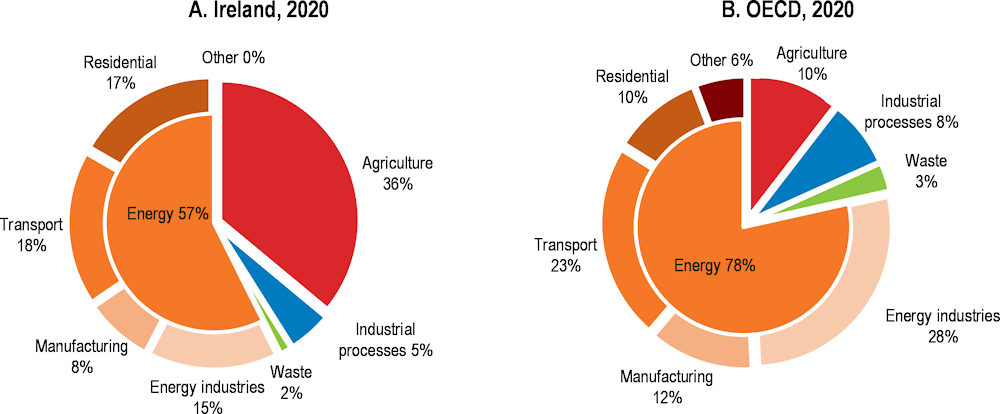

The economy weathered the COVID-19 pandemic and is coping effectively with the repercussions from Russia’s war against Ukraine. The lockdown was one of the strictest in the OECD and vaccination rates rose to amongst the best in the OECD. Benefitting from fiscal space, government policy reacted forcefully to support firms and households and preserve worker attachment to firms. Exports from the multinational part of the economy benefited from strong demand for medical and information communication technology goods and services. As a result, trend headline GDP growth remained robust while modified domestic demand, a national indicator that excludes globalisation-related investment in aircraft for leasing and on-shored intellectual property assets (Box 1.1), declined by 4.8% in 2020, before returning to pre-pandemic levels in the third quarter of 2021 (Figure 1.1, Panel A). The reopening of the economy was accompanied by a strong bounceback in activity and the unemployment rate dropped quickly (Panel B). The war in Ukraine has affected the Irish economy through the slowdown in global demand, particularly in major European trading partners, and the surge in energy and food prices, but the government announced a wide set of measures to support households and firms.

Figure 1.1. Robust external demand and extended income support sustained the economy

1. Excludes those large transactions of foreign corporations that do not have a big impact on the domestic economy.

2. The COVID-adjusted unemployment rate is an estimate of the share of the labour force that was not working due to unemployment or COVID-related absences.

Source: OECD, National Accounts database; Central Statistics Office; and Eurostat.

Ireland faces challenges to sustain growth and improve well-being over the longer term. To wit, the country’s ambitions to overhaul the health system to improve quality of care and value for money, ensure affordable housing and achieve a just carbon transition. In each area, substantial public spending is potentially needed and ensuring spending efficiency will be required. While the fiscal position is currently strong, with buoyant revenues, risks loom and cost-efficient policies will be needed.

Box 1.1. Different measures to capture the underlying dynamics of the domestic Irish economy

To better capture the underlying dynamics of the Irish economy, the Central Statistics Office publishes some alternative metrics, such as Modified Domestic Demand (MDD) and Modified Gross National Income (GNI*). The former measures domestic demand, but excludes volatile components of investment spending by multinationals, namely on-shored intellectual property assets and investment in aircraft for leasing, which have very little impact on the domestic economy. GNI* goes further by taking into account the import content of domestic expenditure and the contribution to growth from domestic net trade (i.e., excluding multinational dominated trade), thereby allowing for a comprehensive assessment of productivity trends. In particular, relative to the standard GNI, GNI* excludes the factor income of firms that have re-domiciled their headquarters to Ireland, as well as the depreciation of trade in on-shored intellectual property assets, R&D service imports and aircraft owned by aircraft-leasing companies. A related alternative metric is the modified current account balance (CA*), which removes a number of globalisation-related distortions, including trade and depreciation of intellectual property assets and aircraft related to leasing along with profits of redomiciled firms. Table 1.1 presents some of the main variables presented in the Basic Statistics Table at the start of this Survey as a share of GNI*.

Table 1.1. Selected variables as a share of GNI* and GDP

|

2021 |

% of GNI* |

% of GDP |

|---|---|---|

|

General government expenditures |

45.2 |

24.8 |

|

General government revenues |

42.2 |

23.2 |

|

General government gross financial debt |

120.0 |

65.9 |

|

General government net financial debt |

74.4 |

40.9 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

244.7 |

134.4 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

172.9 |

95.0 |

|

Modified current account balance |

11.1 |

6.1 |

|

Gross domestic expenditure on R&D |

2.3 |

1.2 |

|

Public and private spending on health |

12.3 |

6.7 |

|

Public and private spending on pensions |

7.0 |

3.8 |

|

Public and private spending on education (% of GNI) |

5.9 |

4.2 |

Source: OECD, National Accounts database; Central Statistics Office; World Bank, World Development Indicators; OECD, Health Expenditure and Financing database; OECD, Social Expenditure database; Department of Finance (2021), Forecasting GNI* - Detailing the Department of Finance Approach, Dublin; Central Statistics Office, Modified GNI; and Department of Finance (2019), The Balance of Payments in Ireland: Two Decades in EMU, Dublin.

Health care reform is a major political initiative. While measures of health sector performance are good overall and the system weathered the COVID-19 pandemic better than initially feared, care provision is relatively expensive and facing mounting spending pressures as the population begins to age rapidly. The Sláintecare reform presents opportunities to reform a complex healthcare system and provide more integrated cost-efficient care. At the same time, the government is facing the legacy of past underinvestment in the sector and the build-up of long waiting lists, which will need to be addressed over time.

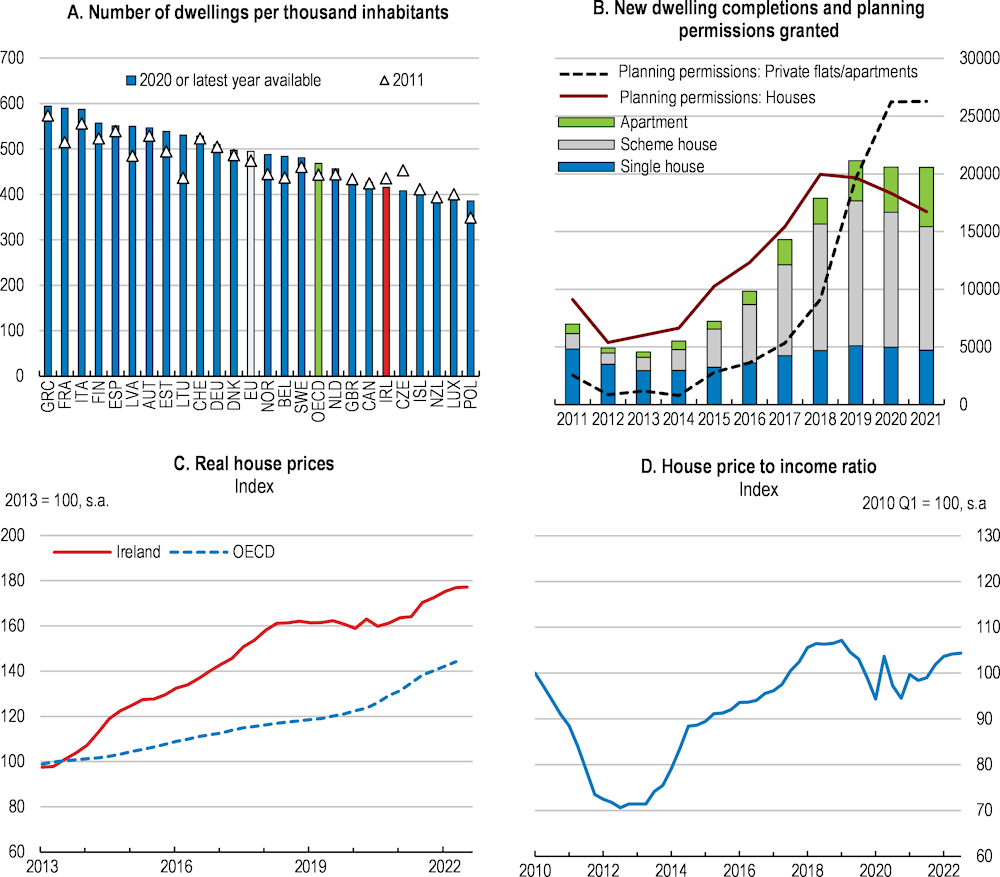

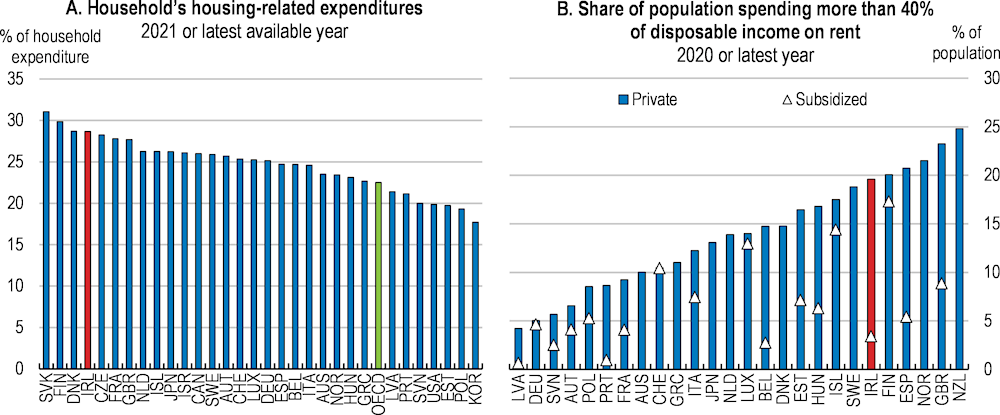

Spending pressure has also emerged in the housing sector. A prolonged period of underinvestment, combined with a legal and regulatory system that hinders supply, account for a relatively old housing stock, housing shortages (particularly in the rental market) and weak housing supply. This has put upward pressure on house prices and rents and has led the government to introduce the Housing for All reforms in 2021. Addressing the issue will require sustained effort and faces implementation challenges, including labour shortages in the construction sector. Labour mobility, in turn, is affected by housing shortages and costs.

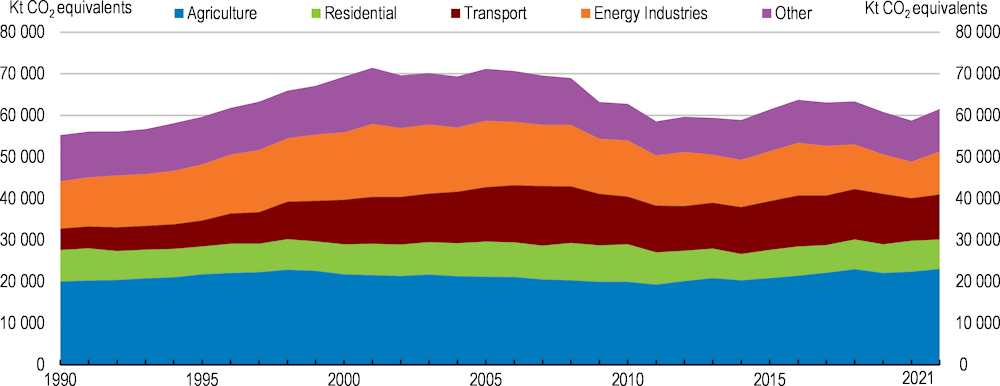

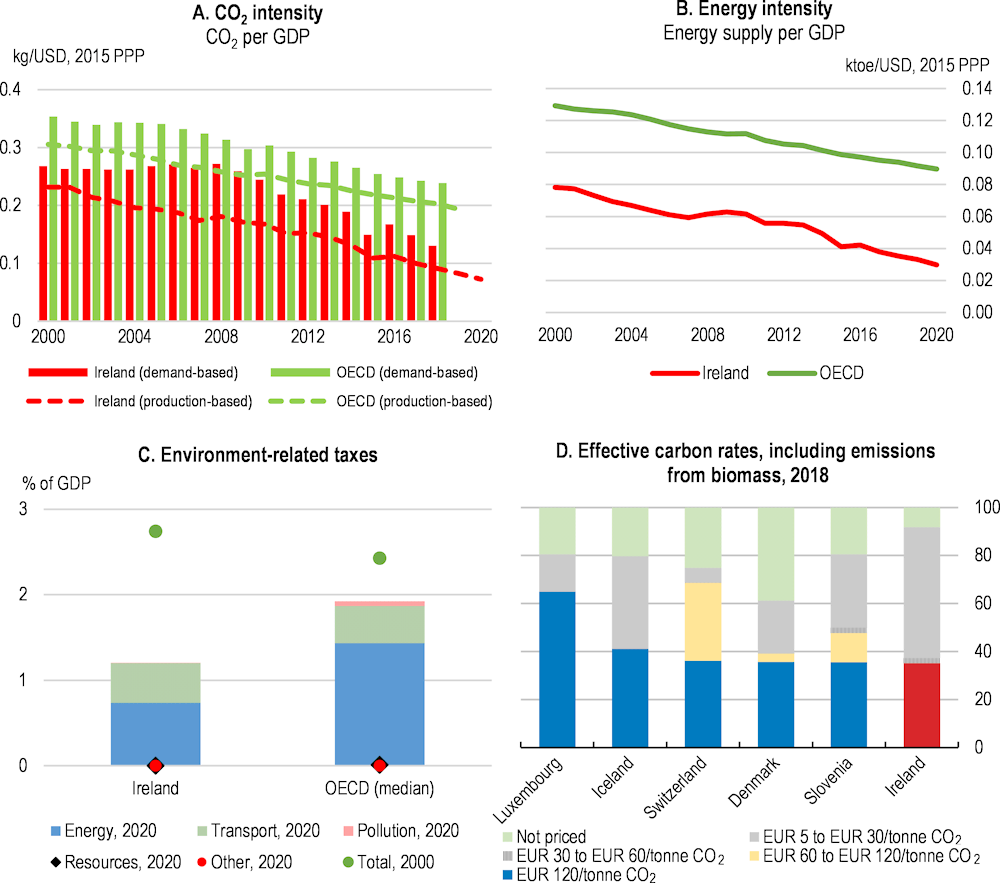

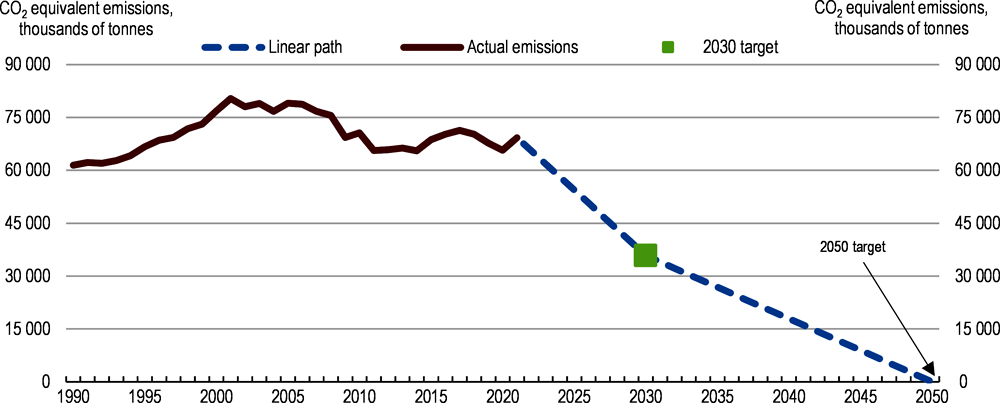

A third major pressure on policy is addressing climate change. Having missed the abatement target in 2020, the government has adopted a net-zero greenhouse gas emission target for 2050 with an interim target for 2030 and has begun to elaborate policies to meet them combining market-based and regulatory measures. Meeting the targets cost-efficiently will require significant reforms. Furthermore, investment needs in the transport sector and energy efficiency improvements in the existing housing stock will add to the demand for labour in construction, which should be addressed urgently. Achieving emission reductions in agriculture is difficult without a major downsizing of the sector, possibly calling for greater effort elsewhere. In addition, the regulatory and legal barriers facing major investments are also potential constraints on maximising the potential of renewables.

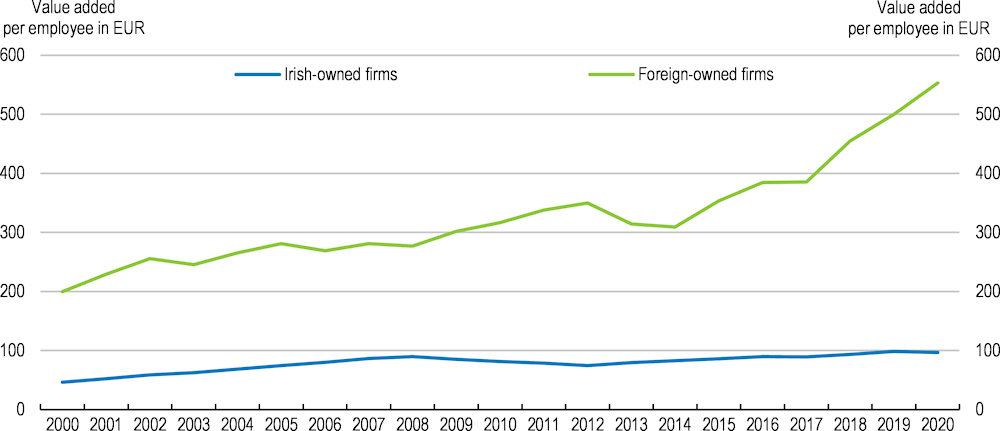

Despite openness to new technologies, spillovers to domestic firms from the multinational sector have been limited, resulting in modest productivity growth (OECD, 2020a). In addition, certain groups face difficulties maintaining attachment to the labour market and heightened risk of poverty. Measures fostering the acquisition of digital and green construction skills and improving access to finance for innovative SMEs, would likely boost participation and productivity in the domestic-oriented economy.

Against this background, the key messages of this Survey are:

Current revenue buoyancy has allowed Ireland to weather the COVID-19 pandemic and the repercussions of the Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, but action will be needed to put public finances on a sounder footing in the face of foreseeable pressures from ageing, including by addressing pro-cyclicality in spending and not delaying measures to meet the longer-term challenges.

Past underinvestment in housing and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions call for major investments. The government is boosting investment in these areas, but action is also required to reduce regulatory and legal hurdles, to reduce uncertainty and high transaction costs, which could derail progress on both fronts.

The government has launched a major reform of the health sector, Sláintecare. The sector is complex, relatively expensive and suffering from legacy issues, such as elevated waiting lists, that will be difficult to resolve quickly. Moving to a more integrated system of primary, community and hospital care offers solutions. It will be important to seek out efficiency gains and avoid raising spending to address short-run pressures.

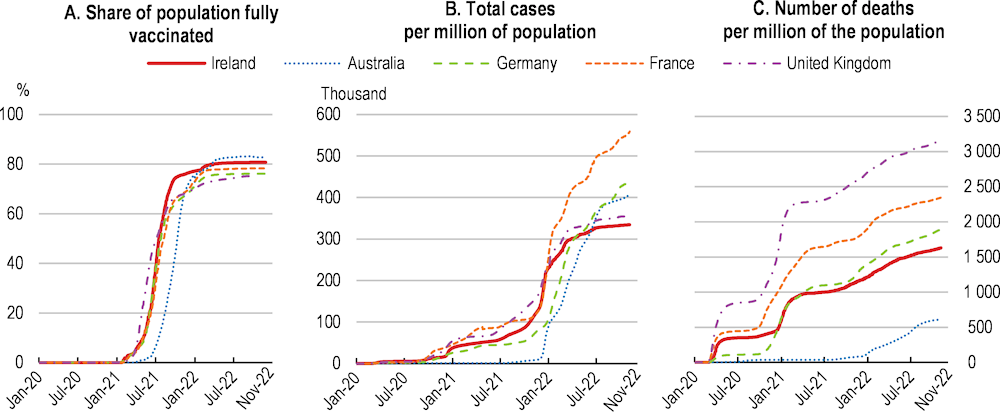

1.2. Growing uncertainties will dent the pace of the recovery

During the pandemic, Ireland experienced several waves of infection and implemented strict containment policies and lockdowns involving curfews and the closing of non-essential businesses. This had a severe impact on the domestic-oriented sectors of the economy, with private consumption falling by around 12% in 2020. At the same time, strong external demand for pharmaceuticals, medical supplies and other pandemic-related goods and services – including information and communication technologies – boosted profits in sectors dominated by multinational enterprises and enabled Ireland’s total economy to avoid a recession, unlike virtually all other OECD economies. Strong roll-out and take-up of vaccines supported a gradual re-opening of activities in mid-2021, as sanitary conditions eased somewhat, and helped contain the impact of the Omicron variant on Ireland’s health system (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Success in vaccination helped overcome COVID-19

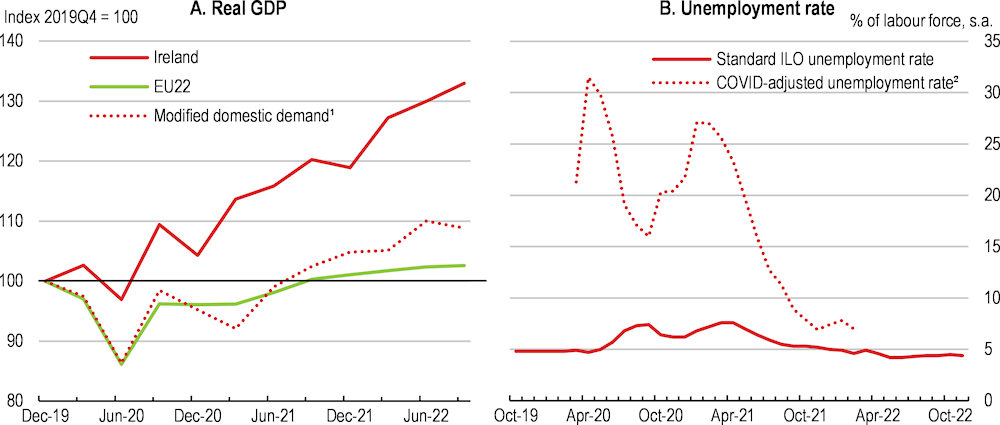

The domestic economy grew strongly in the first half of 2022 as the positive impetus from the full relaxation of containment measures partly compensated for higher inflation and uncertainty exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Growing wages and household excess savings, which still remain well above pre-pandemic levels, sustained consumer spending, as the economy reopened. However, with the sharp fall in consumer confidence (Figure 1.3, Panel A) and high inflation, private consumption growth moderated in the third quarter of 2022. The fall of confidence was less pronounced among businesses, which largely passed rising costs on to consumers (Panel B). Nevertheless, high uncertainty, lower real household disposable incomes and tightening financial conditions are weighing on domestic firms’ business outlook.

The labour market recovered strongly in the aftermath of the pandemic. The simultaneous winding down of the emergency pandemic unemployment payments and the employment wage subsidy schemes led to a rebound in the labour force. At the same time, job vacancies remain high at 1.5% (0.8% in the first quarter of 2020), but lower than the EU average of 2.9% in the third quarter of 2022. The pandemic also affected job transitions. In late 2021, 45% of people who returned to work were with another employer ̶ 31% in the same sector and 14% in a different sector (Department of Social Protection, 2022).

Figure 1.3. The risks to the recovery are considerable

1. Composite of manufacturing and services sectors.

Source: European Commission, Business and Consumer Surveys; and AIB / HIS Markit PMI indices.

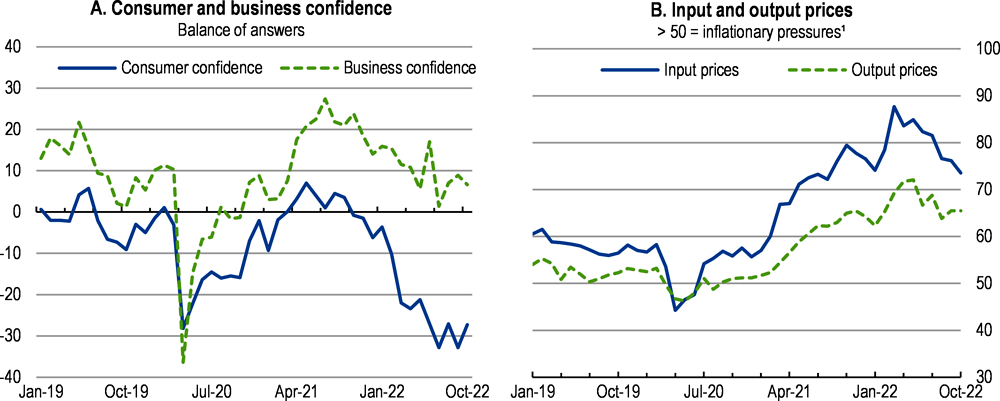

Consumer price increases, while still driven by high energy prices, have become more broadly-based (Figure 1.4). Headline inflation was 9% in November, albeit below the 10% euro area average, and energy prices were up by 43%. Firming prices of transport, hospitality, and recreational services, in the wake of the full re-opening of the economy, contributed to the rise in core inflation, which stood at 4.7% in October. The share of goods recording price increases of over 5% increased to almost 60%. Soaring prices of energy and other essentials disproportionately affect poorer households (CSO, 2022) – particularly elderly, youths and lone parents (ESRI, 2022), which can further raise inequalities before taxes and transfers. Elevated input costs coupled with reduced demand pose a threat to SMEs relying on household discretionary spending.

Figure 1.4. Inflationary pressures have become broad-based

Harmonised indices

1. Preliminary estimates for November; light blue bars are October values.

2. Excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco.

Source: Eurostat, Monthly Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices.

Public support measures to limit the adverse impact of surging energy bills are sizeable. The first set of measures (0.6% of 2021 GDP and 1.1% of GNI*) included means-tested fuel allowances and some additional lump-sum payments to recipients, electricity credits, temporary reductions in fuel excise duties and VAT rates on electricity and gas, and a 20% reduction in public transport fares. The one-off and temporary cost-of-living package announced in Budget 2023 (€2.7 billion in expenditure and €1.7 billion in tax measures) extends these initial policies. It also includes additional welfare payments to all social protection recipients, an additional child benefit payment, support to eligible students, additional allocation of funds to support public services and community organisations (€300 million) and a new business energy support scheme (€1.2 billion). The share of targeted measures increased from 11% in the initial package to 40% in the new package (Central Bank of Ireland, 2022a), which is welcome (see below for a discussion).

Direct macroeconomic risks from Russia’s war against Ukraine are limited, as Ireland’s goods trade with Russia, Ukraine and Belarus is modest (Box 1.2). However, specific shocks could hit agriculture and some industries dependent on specialised energy inputs. As for trade in services, the aircraft leasing industry could be affected, although the impact on the domestic-oriented economy would be negligible. Following the Government’s commitment not to cap their number, Ireland had welcomed around 62 000 Ukrainian refugees by early November (equivalent to 1.2% of the country’s population), with state accommodation provided to about two thirds of them. At the same time, Ireland’s financial support for Ukrainian beneficiaries of temporary protection to cover basic need is amongst the EU’s most generous (OECD, 2022). Budget 2023 allocates €2 billion to provide support to refugees. Measures currently under discussion to meet their accommodation needs, in a context already marked by severe housing imbalances, include the building of modular housing on public serviced sites, reconversion of vacant or unused buildings and monthly allowances to assist Irish households with hosting costs.

Box 1.2. The impact of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine

Ireland’s trade links with Russia, Ukraine and Belarus are modest and, as a result, the direct macroeconomic risks are limited. However, specific shocks could hit agriculture and some industries dependent on fertilisers and specialised energy inputs. Total exports to and imports from Russia were €3.7 billion and €0.65 billion, respectively, in 2020, accounting for around 1% of total exports and 0.2% of total imports.

The main exports to Russia have been computer services (50%), aircraft leasing (25%) and pharmaceutical products (5%). Ireland has become an international hub for special purpose vehicles engaged in aircraft leasing. The war will have a sizeable impact on the Irish aircraft leasing industry, which currently manages over €100 billion in assets. About 150 planes are rented to Russian airlines and there are significant uncertainties over the possibility to recover these Irish-owned planes from Russia, which recently introduced new legislation allowing foreign aircrafts to be registered in the country. Reversals in aircraft leasing activities will likely create some volatility in future GDP numbers, through changes in both investment flows and imports.

Imports of goods from Russia account for around one-half of a percentage point of total goods trade and are mainly composed of energy products and fertilisers. Ireland sourced only 6% of its oil imports from Russian suppliers in 2021 – and no gas at all. On the other hand, the share in the imports of coal, coke and briquettes hovers around 65-70%, but this accounts for only around €140 million or 0.13% of total imports. More than 25% of Ireland’s imports of fertilisers came from Russian manufacturers. Business services account for around one-half of total imports from Russia.

Around 70 firms connected to Russia with total assets of €62 billion are involved in funds activity in the Irish Financial Services Centre. However, the impact of these firms on the domestic economy in terms of corporate taxation and administrative costs paid is quite low. While liquidity and solvency issues for these firms may raise reputational risk for the Irish financial sector, these assets are not owned by Irish firms and households.

The secondary impacts through energy prices and demand from European economies are more pronounced. Rising costs of energy and fertilisers are putting upward pressure on home heating, transport and food prices, which are among households’ largest spending items. The slowdown in activity in major trading partners reduces demand for exports, although the composition of exports enabled them to remain resilient despite weaker demand.

The unwinding of COVID-19 pandemic support and the effects of renewed inflationary pressures have the potential to increase business insolvencies. As in most OECD countries, insolvencies did not pick up even after the phasing out of emergency support measures (PWC, 2022a). However, insolvencies increased by 49% in the third quarter of 2022 compared to a year ago, even though they remain below pre-pandemic levels (PWC, 2022b). Around 4% of active Irish businesses may require restructuring, liquidation, or some form of company dissolution (McCann and McGeever, 2022). In this context, the Small Company Administrative Rescue Process (SCARP), introduced in 2021, is welcome. Relative to the more formalised examinership legal alternative, SCARP’s streamlined insolvency process could effectively accelerate the debt restructuring proceedings of insolvent but still viable SMEs, and the exit of zombie firms. Nevertheless, given the possibility that creditors may challenge proposals in court and the difficulties very small companies may face in funding even modest professional fees associated with restructuring, effective monitoring will be key.

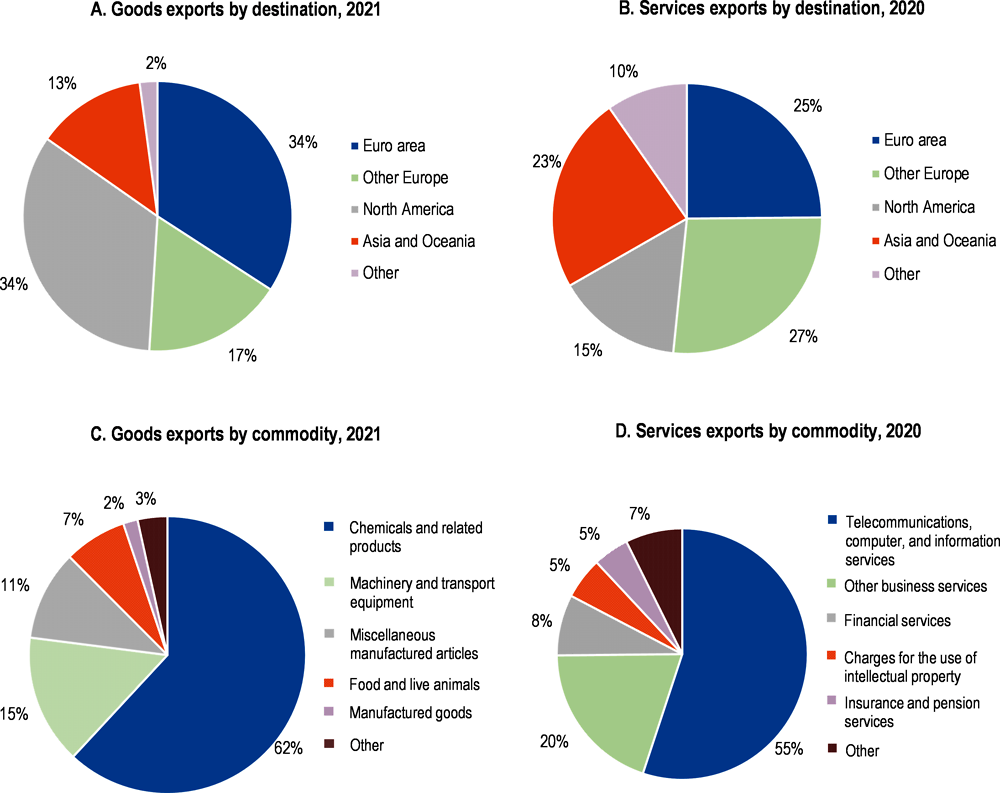

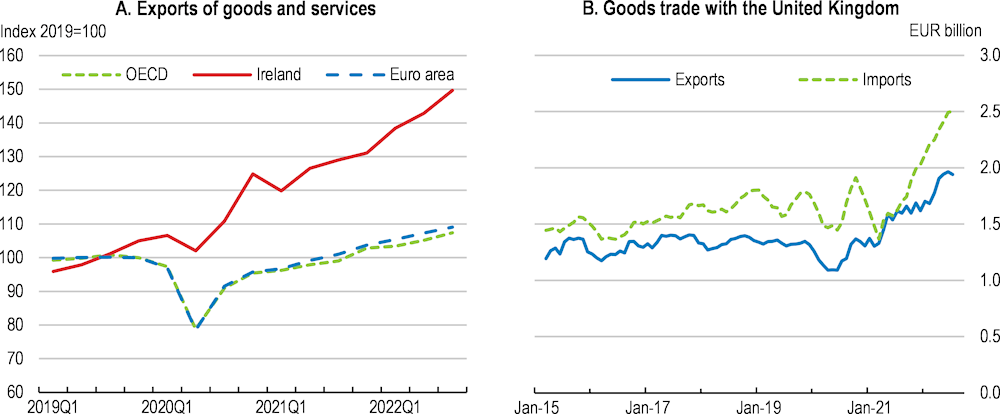

The multinational portion of the economy saw a dramatic surge in exports during the pandemic (Figure 1.5, Panel A), thanks to the concentration in goods and services in high demand, in particular pharmaceutical goods, medical devices and ICT services, and geographically diversified markets (Figure 1.6). The new trading relations with the United Kingdom do not yet include restrictions on Irish exports of goods to Great Britain, and thus do not appear to have derailed Irish exports, while rising energy prices are pushing up the value of imports from the United Kingdom (Figure 1.5, Panel B). However, risks remain around the future of the Northern Ireland Protocol and the trading relationship with the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom has not yet implemented fully the Trade and Co-operation Agreement, whose checks on imports could hurt Irish exports. Trade with the rest of Europe has been affected. The loss of cabotage opportunities on the UK landbridge has led to a switch to shipping directly to Europe, mainly France. The port of Dublin has become an important node for European trade and has managed successfully to reorient shipping to accommodate more unaccompanied haulage, but further expansion may require greater development of other ports, such as Rosslare.

Figure 1.5. Trade has remained robust despite potential obstacles

Note: Panel A shows export volumes; Panel B shows the 5-month centred moving average.

Source: OECD, National Accounts database; and Central Statistical Office.

GDP and modified domestic demand growth are projected to be 10.1% and 8%, respectively, in 2022, reflecting the post-pandemic rebound in activity in the first half of the year. Going forward, falling real incomes due to inflation will hold back consumer spending up to 2023, despite significant wage growth. High costs and low confidence will reduce firms’ incentives to invest. Public investment support through the National Development Plan will partly offset weaker private business and residential investment, with Budget 2023 allocating €11.7 billion to capital expenditure in 2023. Modified domestic demand will thus only grow by 0.9% next year, before rebounding to 3.1% in 2024. As exports in multinational-dominated sectors, though moderating, will remain supportive, GDP is projected to grow by 3.8% in 2023 and 3.3% in 2024 (Table 1.2). Inflation is projected to gradually ease by 2023, but with still relatively elevated core inflation.

If funding costs were to rise faster than expected, some domestic firms might downsize or ditch their investment plans. Additionally, protracted uncertainties around the full implementation of Brexit agreements may weaken firms’ competitiveness. Persistently high input price inflation, while weighing on firms’ profitability, could also hamper the fiscal sustainability of the ambitious government agenda to subsidise residential construction and retrofitting, in a bid to boost housing supply and ease pressure from high house prices and rents. These, however, could increase further because of additional demand for accommodation triggered by growing numbers of Ukrainian refugees. Furthermore, energy supply disruptions in the winter of 2023-24 could affect growth, including through weaker external demand. On the upside, GDP growth may turn out stronger, as multinational-dominated exports of pharmaceutical and medical goods may be more resilient than foreseen to slowdowns in major trading partners. In addition, other lower probability threats to the outlook could derail the recovery (Table 1.3).

Figure 1.6. Exports are geographically diversified and largely chemicals and ICT services

Table 1.2. Growth is projected to slow

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (EUR billion) |

Percentage changes, volume (2020 prices) |

|||||

|

GDP at market prices |

355.7 |

5.6 |

13.4 |

10.1 |

3.8 |

3.3 |

|

Private consumption |

104.2 |

- 11.9 |

4.5 |

5.7 |

1.3 |

3.1 |

|

Government consumption |

42.8 |

10.4 |

6.1 |

2.5 |

- 0.3 |

- 0.8 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

193.5 |

- 17.0 |

- 39.1 |

2.7 |

4.1 |

3.1 |

|

Final domestic demand |

340.6 |

- 12.4 |

- 18.0 |

4.9 |

2.1 |

2.3 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

4.3 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

- 0.6 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

344.9 |

- 12.1 |

- 18.0 |

4.1 |

1.0 |

2.4 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

455.7 |

11.1 |

14.0 |

12.5 |

5.4 |

4.0 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

444.8 |

- 2.2 |

- 8.3 |

9.4 |

4.7 |

3.8 |

|

Net exports1 |

10.9 |

16.9 |

27.9 |

7.9 |

3.0 |

1.9 |

|

Memorandum items |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Modified total domestic demand², volume |

_ |

- 4.8 |

5.9 |

8.0 |

0.9 |

3.1 |

|

GNI*3 |

_ |

-4.6 |

15.4 |

|||

|

GDP deflator |

_ |

- 0.5 |

0.4 |

6.1 |

4.1 |

1.9 |

|

Harmonised index of consumer prices |

_ |

- 0.5 |

2.4 |

8.4 |

7.2 |

2.9 |

|

Harmonised index of core inflation4 |

_ |

- 0.1 |

1.7 |

4.8 |

4.6 |

3.0 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

_ |

5.8 |

6.2 |

4.7 |

5.3 |

5.1 |

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of disposable income) |

_ |

21.6 |

20.2 |

16.8 |

14.6 |

12.4 |

|

General government financial balance5 (% of GDP) |

_ |

- 5.0 |

- 1.7 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

|

General government financial balance5 (% of GNI*) |

_ |

- 9.4 |

- 3.0 |

|

|

|

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP) |

_ |

72.1 |

65.9 |

59.8 |

56.2 |

52.9 |

|

General government gross debt (% of GNI*) |

_ |

134.9 |

120.0 |

|

|

|

|

General government debt, Maastricht definition6 (% of GDP) |

_ |

58.2 |

55.4 |

49.4 |

45.7 |

42.5 |

|

General government debt, Maastricht definition6 (% of GNI*) |

_ |

108.9 |

100.9 |

|

|

|

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

_ |

- 6.8 |

14.2 |

16.4 |

18.9 |

18.7 |

|

Modified current account balance7 (% of GNI*) |

_ |

6.6 |

11.1 |

|

|

|

Note: OECD Economic Outlook 112 projections for 2022-24 with updated annual national account historical data for 2020 and 2021 but not taking into account the quarterly data released on 2 December 2022 for 2022 Q1-Q3.

1. Contributions to changes in real GDP, actual amount in the first column.

2. Excludes those large transactions of foreign corporations that do not have a big impact on the domestic economy.

3. Excludes the factor income of firms that have re-domiciled their headquarters to Ireland, as well as the depreciation of trade in on-shored intellectual property assets, R&D service imports and aircraft owned by aircraft-leasing companies.

4. Harmonised index of consumer prices excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco.

5. Includes the one-off impact of recapitalisations in the banking sector.

6. The Maastricht definition of general government debt includes only loans, debt securities, and currency and deposits, with debt at face value rather than market value.

7. Modified current account balance removes a number of globalisation-related distortions, including trade and depreciation of intellectual property assets and aircraft related to leasing along with profits of redomiciled firms.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook 112 (database) and Central Statistics Office.

Table 1.3. Low-probability events that could lead to major changes to the forecast

|

Shock |

Likely outcome |

Policy response options |

|---|---|---|

|

Escalating trade tensions |

Some exporters could face difficulties in accessing key markets. |

Help vulnerable companies identify new market opportunities. |

|

Outbreak of a new vaccine-resistant COVID variant |

New waves of vaccine-resistant infections could potentially lead to new lockdown measures, further reducing confidence and lowering domestic consumption. |

Monitor health developments closely and continue to encourage vaccination, including booster shots. Keep contingency plans for moving to online work where possible and maintain stocks of personal protective equipment even as infection rates slow. |

|

Cyberattacks could halt operations in the financial sector or in key infrastructure. |

Interrupted access to key services could disrupt economic activity. |

Work to identify potential weaknesses and how to ensure continuity of service and data security. |

1.3. The financial sector is facing legacy and new challenges

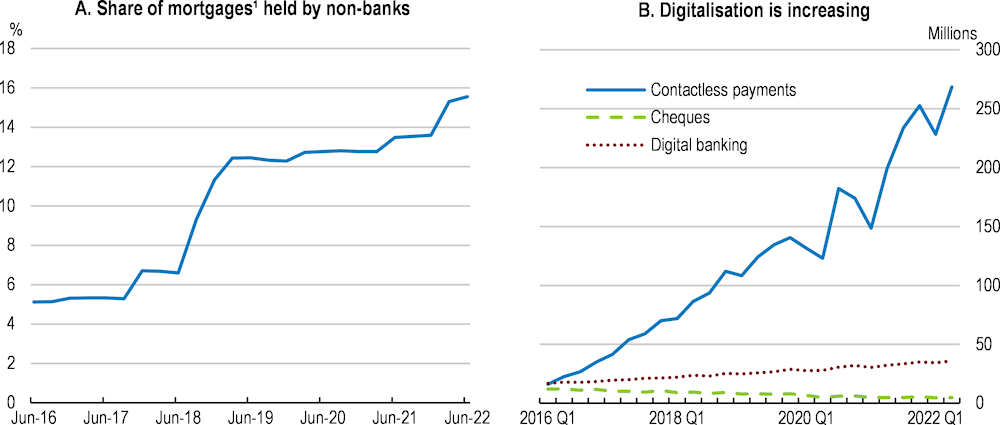

The financial sector has withstood the COVID-19 pandemic. Retail banks returned to profitability after the losses incurred during the first year of the pandemic. Credit growth picked up from the lows during the lockdowns, largely driven by non-financial corporate sector borrowing. Non-bank financial institutions are growing in importance (Figure 1.7, Panel A). Non-performing loans on banks’ balance sheets have been falling steadily for both businesses and households, partly driven by loan sales to other parts of the financial system. Furthermore, residential mortgages no longer account for the majority of non-performing loans, representing further progress in addressing the legacy of the 2008 burst of the housing bubble. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has spurred further digitalisation, with strong growth in the use of digital and contactless means of payment (Panel B).

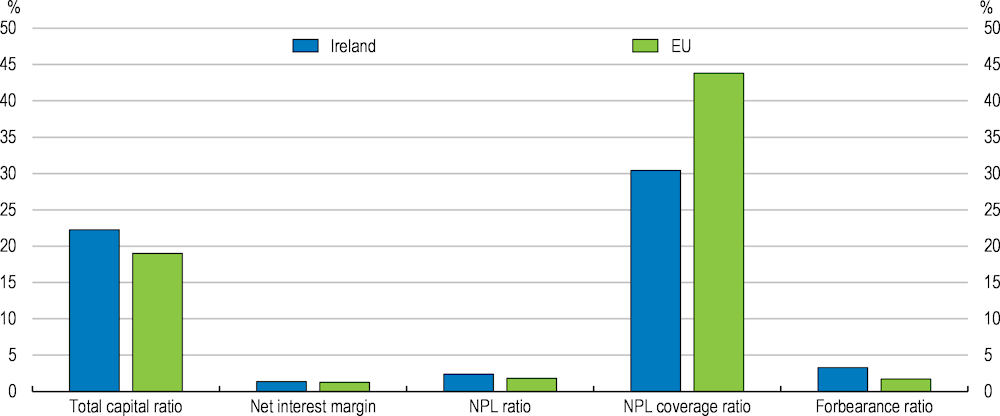

Figure 1.7. The financial sector is somewhat less dominated by banks and increasingly digital

Even so, a number of structural issues remain, some stemming from the legacies of the 2008 global financial crisis. Mortgage arrears are still relatively elevated and non-performing loans in the commercial sector are also above pre-pandemic norms. Borrowing costs are relatively high and retail banks’ return on equity is somewhat lower than elsewhere in the European Union. This is partly a reflection of restructuring costs incurred to lower operating costs and diversify income sources. However, capital ratios exceed the EU average (Figure 1.8) and a higher inflation environment may offer opportunities to increase profits.

Retail banks account for around 60% of lending by the banking sector, and the announced withdrawal of two of the five retail banks will increase concentration in the sector, as their businesses are expected to be largely taken over by the remaining three (IMF, 2022a). To some degree, the growing importance of non-bank financial institutions will mitigate the potential reduction in competition. New services are being offered by the recent entrants, such as digital payment services and Irish customers appear to be relatively receptive to innovation. However, these non-bank financial institutions do not offer a full suite of banking services and potentially benefit from an uneven playing field, not being subject to the same regulatory measures. Prudential supervisors need to keep a careful eye on developments, both to protect customers and prevent the build-up of financial risks in the non-bank sector. The Central Bank of Ireland has been taking action to ensure consumer protection. In 2022, it fined two of the large banks around €100 million each over their actions of denying tracker mortgages or not passing decreasing market interest rates onto borrowers with tracker mortgages. In October 2022, the Central Bank of Ireland launched a review of the consumer protection code, which is welcome.

Figure 1.8. Capital ratios are somewhat higher than the EU average

Q2 2022

Macroprudential tools served to support the financial sector during the recent crises. During the pandemic, the Central Bank of Ireland set the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) to zero. The institution-specific capital buffers for the systemically important institutions range between 0.5 and 1.5%. The Central Bank of Ireland announced an increase in the CCyB rate to 0.5% in June 2022 (effective from June 2023) and indicated that, depending on the evolution of macro financial conditions, a CCyB rate of 1.5% is expected to be announced by mid-2023. The expected tightening of the countercyclical buffer should be followed through, given the economy’s exposure to external shocks.

1.3.1. Dealing with mortgage arrears

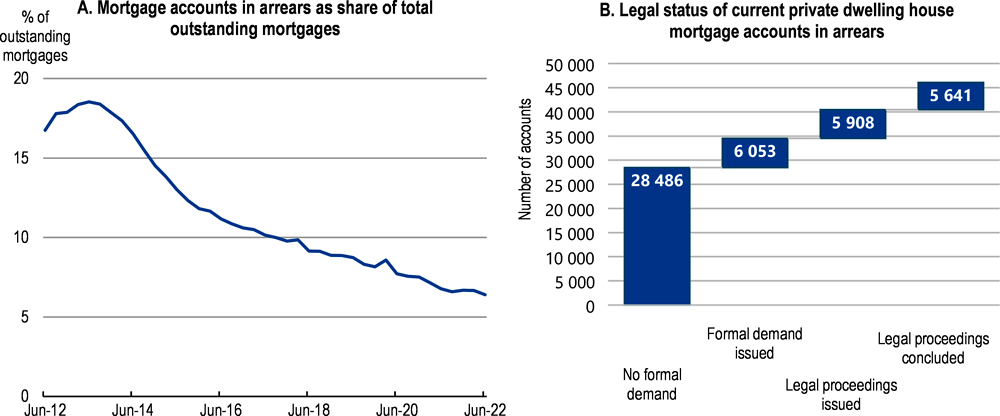

The ratio of non-performing mortgage loans at 3.6% was higher than the EU average of 1.7% in the first quarter of 2022. Despite a steady decline in recent years, mortgage arrears as a percentage of outstanding mortgages were still around 6.4% in June 2022, concerning about 46 000 principal dwelling houses (Figure 1.9, Panel A). Of these, no formal demand for legal proceedings had been issued for 62% and 1.4% had been restructured (Panel B). Resolving mortgage arrears remains a significant problem. Lenders are required to adhere to the Central Bank of Ireland’s Code of Conduct on Mortgage Arrears and follow a Mortgage Arrears Resolution Process. Around 21 000 primary residences have been in arrears for over two years. About half these were either restructured or the account holder was co-operating with the mortgage holder. Of the remaining, when the account is not co-operating and thereby loses the protection of the Mortgage Arrears Resolution Process, the lender had issued legal proceedings for about one half of the accounts. The ability of banks to enforce collateral is weak and time consuming. The number of homes repossessed by banks when borrowers have been delinquent remains very low. In the second quarter of 2022, just 11 principal dwelling homes and two buy-to-rent houses were repossessed on the basis of a court order. For primary residences, this is notwithstanding 5 641 legal cases having been concluded in the second quarter of 2022 with arrears outstanding. Furthermore, another 5 908 legal cases were in process in the second quarter of 2022, of which around one third had been ongoing for over five years since the first court hearing (Central Bank of Ireland, 2022b), partly reflecting the frequent adjournment of mortgage arrears cases before the courts.

Figure 1.9. Outstanding mortgage arrears are a legacy of the property collapse

Q2 2022

Addressing these legacy issues will require flexible and innovative policies, given the relatively low repayment capacity of a large number of debtors (Kelly et al., 2021). The 2020 Economic Survey of Ireland recommended granting creditors a collateral possession order for a future date to speed up non-performing loan resolution. Greater use of the ‘suspended’ possession order, like in the United Kingdom, could encourage engagement between the borrower and lender by granting lenders a collateral possession order which is suspended for a future date, with the suspension conditional on the borrower complying with well-defined criteria. For example, suspended possession orders in the United Kingdom allow the borrower to remain in the residence while continuing to pay off arrears. If the conditions are not met, the creditors can ask the courts to issue an eviction order. However, care should be taken to avoid unintended consequences, such as encouraging collateral to be run down by debtors.

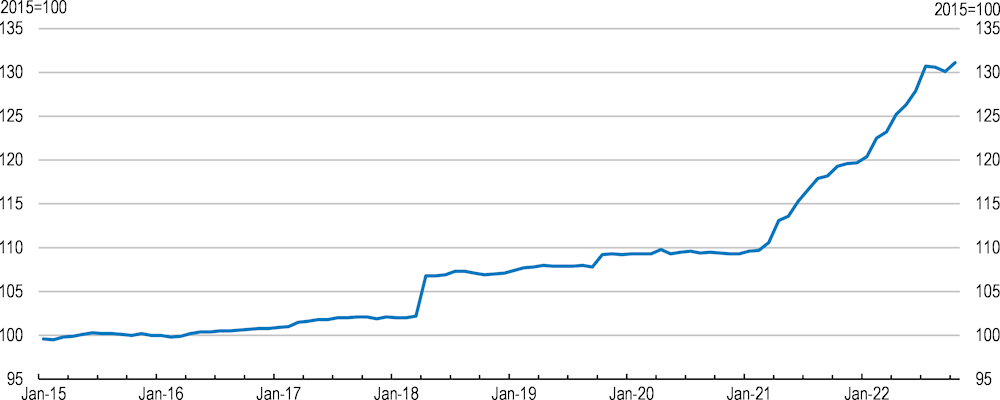

Besides creating vulnerabilities, low resolution rates of mortgage arrears might be contributing to the low credit supply by banks to private households and small construction firms, with banks favouring lending to real estate investment trusts. At least half of households who rent from a local authority and from the private market are unable to access the credit needed to purchase a property at the median price of a dwelling in Dublin based on current loan-to-income (LTI) mortgage criteria (Government of Ireland, 2021a). Following a review of its 2015 macroprudential framework for mortgage lending, the Central Bank of Ireland relaxed its lending standards in October by raising LTI limits for first-time buyers from 3.5 times of annual gross income to four times and increasing loan-to-value limits for second and subsequent buyers from 80% to 90%. While these changes can help improve affordability in the face of rising interest rates and costs, they can also increase housing demand and prices and financial stability risks. Hence, they should be monitored closely.

The share of new mortgage lending from non-bank lenders has increased from less than 3% in 2018 to 13% in 2021 (Gaffney, Hennessy and McCann, 2022). Non-banks now account for almost one third of new lending in the refinancing and buy-to-let segments of the market. Non-banks have been reducing interest rates more rapidly than banks since 2018, and were charging a lower average rate to first-time buyers than retail banks in 2021 (Central Bank of Ireland, 2022c). Some of these lenders have responded to tighter global financial conditions with increases in interest rates for prospective new mortgage borrowers since the summer of 2022. Rising potential risks from non-bank lending to financial stability should be addressed. The monitoring of non-bank lenders beyond those engaged in mortgage activities should also be expanded (IMF, 2022b).

Non-banks are also playing an active role in the commercial real estate market (CRE), with property funds accounting for nearly 44% of the CRE market (Central Bank of Ireland, 2021a). Given the size of the sector, the impact of widespread forced sales by Irish property funds on the CRE market on financial and macroeconomic stability could be significant. The Central Bank of Ireland has introduced macroprudential measures in the non-bank sector, targeting those Irish-domiciled investment funds with over half their assets in the Irish property market and thus are particularly exposed to domestic real estate shocks. The new measures introduce liquidity timeframe guidance and a leverage limit tailored to these investor funds, with an aim to safeguard the resilience of this growing form of financial intermediation (Central Bank of Ireland, 2022d). Such stronger macroprudential measures for non-banks can help address vulnerabilities posed by those property funds with high levels of leverage and liquidity mismatch. They can also help level the playing field with banks.

1.3.2. Innovation in the financial sector

Fintech is relatively well-developed in Ireland (Ziegler et al., 2021), and is expected to expand further with new advances in technology and increased demand following the pandemic. For SMEs, non-bank lenders account for an estimated 37% of the value of total new lending (Heffernan et al., 2021). Such forms of finance can both introduce competition to the traditional banking sector and provide access to finance for entities that have trouble obtaining credit from traditional banks. Indeed, bank financing has been relatively expensive, particularly for SMEs in Ireland (National Competitiveness and Productivity Council, 2021a). In the context of the government’s International Financial Services Strategy Ireland for Finance, the Department of Finance established the Fintech Steering Group, and FinTech and digital finance is a priority theme in the 2022 Update to the Ireland for Finance Strategy. Enterprise Ireland launched the ‘Start in Ireland’ portal aimed at supporting entrepreneurs (including Fintech firms) at different stages of development with information for potential, new and existing start-ups (Government of Ireland, 2022a).

While allowing space for innovation to improve access to digital financial services, ensuring resilience and managing risks arising from Fintech are also key. Since many of these lenders rely on market-based funding rather than insured deposits, the resilience of this supply of financing may be more vulnerable to a downturn or higher interest rates and pose legal and administrative challenges for recovery resolution. Since 2018, the Innovation Hub of the Central Bank of Ireland has enabled informal engagement with these lenders about regulations. The Central Bank recently increased its supervision of regulated Fintech institutions, whose number went from low single digits to 40 in the past four years. A letter of supervisory expectations circulated in December 2021, including on regular reporting and establishing risk frameworks and exit strategies, asked for compliance reviews by institutions. However, many financial service providers remain unregulated. Hence, ensuring regulators have the power to obtain relevant information from such providers, as recommended by the 2020 Economic Survey of Ireland, is also crucial.

Table 1.4. Past OECD recommendations on financial stability and actions taken

|

Recommendations in past surveys |

Actions taken since 2020 |

|---|---|

|

Consider granting lenders a collateral possession order for a future date. Raise provisioning requirements for non-performing loans, including by implementing new European Union regulations related to provisioning. |

No action taken. EU Regulation 2019/630 on minimum loss coverage for non-performing exposures is implemented in Irish law. |

|

Introduce a systemic risk buffer to boost banks’ capital in order to further safeguard financial stability. |

In 2020, the Central Bank of Ireland was given powers to set the systemic risk buffer and identify exposures and subsets of institutions to which it applies. |

|

Ensure regulators have the power to obtain relevant information from unregulated financial service providers. |

No action taken. |

1.4. Ensuring fiscal sustainability is key

1.4.1. The budget position is currently favourable

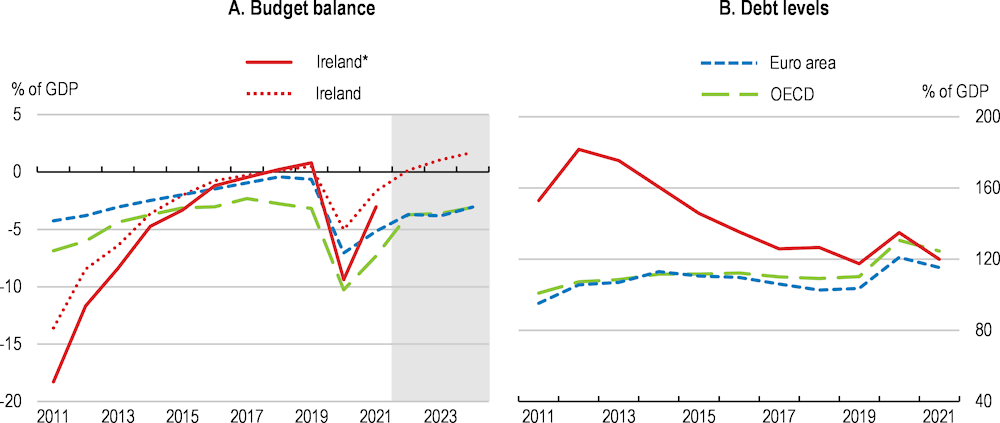

The economic rebound is helping to repair public finances. The robust interventions in the face of the pandemic pushed up public spending dramatically, causing budget deficits and debt to balloon, albeit by less than the rest of the OECD on average (Figure 1.10). At the same time, revenues surged, particularly personal and corporate income taxes. The budget deficit shrank in 2021 as the boost to exceptional spending - the pandemic unemployment payment and wage subsidy schemes - was wound down. The budget position is projected to return to balance by 2022, thanks to exceptionally high levels of corporation tax receipts. A spending rule, limiting permanent spending increases to 5% per annum (broadly the sum of trend growth of an underlying measure of economic activity assumed to be 3% and the 2% inflation target) over the medium term, was recently introduced, which improves the fiscal framework (Box 1.3).

Figure 1.10. The budget position is projected to return to balance

Note: Ireland* uses GNI* as a denominator instead of GDP. Debt is government gross financial liabilities.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook (database); and Central Statistics Office.

In September, the government announced a package of one-off measures (€4.4 billion) to cushion the effects of high inflation on households and firms, and budgetary measures for 2023 (€6.9 billion). Budget 2023 implies an increase in the core expenditure growth rate from 8.1% to 9.1% in 2022 and from 5% to 6.3% in 2023, compared to the April Stability Programme (Government of Ireland, 2022b). The announced overall fiscal stance, which aims to balance between providing support and not adding to inflation, is broadly appropriate.

Around half of the announced temporary measures are targeted (Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, 2022a), while some (electricity credits, double child benefit payment, extension of the VAT and excise reductions on fuel, gas, and electricity) remain untargeted, as in many other OECD countries. As surging energy prices represent a terms-of-trade shock, which is arguably permanent given the expected path of fossil fuel prices, economic agents ultimately need to adjust. In this context, cushioning the blow should not become an obstacle to this process, which at the same time represents a potential constraint on fiscal policy if the measures become entrenched. Furthermore, to ensure greater fiscal and environmental sustainability, such measures should be withdrawn or phased out, and additional persistent stimulus to demand should be avoided in the current context of high inflation. Any further fiscal measure, if needed, should be temporary and better target poorer households, particularly in the event of major increases in food prices, keep the impact on domestic activity broadly neutral and be designed not to distort price signals so that incentives for energy savings are maintained.

Box 1.3. Ireland’s domestic fiscal framework

As a member of the European Union, the public finances in Ireland are subject to the provisions of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). The EU fiscal framework seeks to ensure sound public finances within the Union, avoiding excessive deficits and/or debt levels and encouraging appropriate counter-cyclical fiscal policy. The SGP is a rules-based framework within which Member States’ budgetary decisions are made. Ireland’s domestic fiscal framework was set out in the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2012, and mirrors the European framework. That same year, the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council was formally established, which assesses the government’s forecasts, compliance with fiscal rules and fiscal stance. In 2013, a Medium-term Expenditure Framework introduced three-year government and ministerial expenditure ceilings.

In view of the challenges related to the measurement of both the size and cyclical position of the Irish economy, the Irish Government decided to reinforce the fiscal framework and introduced a domestic expenditure rule in 2021, whereby permanent spending is allowed to increase by 5% per annum (broadly the sum of trend growth of an underlying measure of economic activity assumed to be 3% and the 2% inflation target) over the medium term (Department of Finance, 2021). This rule is designed to meet the dual objectives of expanding public services while maintaining public finances on a sustainable trajectory.

To minimise the risk of relying on volatile and unpredictable receipts to fund permanent increases in expenditure, the Government has also published a new metric, the underlying fiscal balance (GGB*), which excludes estimates of ‘excess’ corporation tax (CT) receipts, as these are potentially transitory. The Department of Finance uses scenario analyses to quantify the level of ‘windfall’ receipts, i.e., the amount that cannot be explained by underlying drivers (Department of Finance, 2022). These include, among others, comparing: i) the current share of CT receipts with its long-run average share (2000-21) in both total tax receipts and GNI*; ii) actual CT receipts to a scenario where CT increased in line with GNI* growth from 2014 onwards (2014 is chosen as it is prior to the level shift in CT receipts in 2015 and preceded, in general, the significant changes in intellectual property on-shoring that have taken place in recent years); and iii) CT receipts with a scenario in which CT payments by foreign multinationals increase in line with wages in the foreign-owned sector from 2014 onwards. The spending rule aims to ensure that expenditure policy is decoupled from windfall tax revenues, and in particular from ‘excess’ corporation tax receipts, in the years ahead.

Source: Department of Finance (2019), Addressing Fiscal Vulnerabilities, Dublin; Department of Finance (2022), De-Risking the Public Finances – Assessing Corporation Tax Receipts, Dublin; and Department of Finance (2021), 2021 Summer Economic Statement, Dublin.

While pressure on spending has increased, revenues have been extraordinarily buoyant. Corporate and personal income tax receipts have soared on the back of surging profits and strong employment and wage growth, and consumption tax revenues also grew strongly. In 2021, total tax revenues rose by 20% over 2020 (more than €11 billion). Corporate taxes amounted to €21.1 billion at the end of November 2022, amounting to an annual increase of €7.6 billion. Government tax revenues are heavily dependent on corporate tax receipts, accounting for over one-fifth of total revenues in 2021 and rising to one fourth in the first half of 2022. The extremely strong export performance of the major multinationals in the pharmaceutical, medical goods and information and communications technologies sectors account for some of the buoyancy. However, this creates a vulnerability to more subdued export performance in the future and a reconfiguration of the location of production and intellectual property in response to changes in the international tax environment. Just ten companies account for about one half of all corporate income tax receipts.

Various estimates suggest that EUR 6 billion to 9 billion of revenues are potentially transitory and could leave Ireland (Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, 2022b; Department of Finance, 2022a). Without these excess (windfall) receipts, the fiscal balance would be a deficit of €8 billion (-3.1% of GNI*), compared to a surplus of €1 billion (0.4% of GNI*) in 2022 (Government of Ireland, 2022b). Against this background, upside revenue surprises should be saved in the National Reserve Fund (so-called Rainy Day Fund, created in 2019, but liquidated due to the pandemic) as a way of reducing reliance on potentially transient forms of income, while preparing for long-term fiscal challenges, rather than facilitating an upward creep of spending. By design, the Fund has caps on yearly and overall contributions of EUR 500 million and EUR 8 billion, respectively. In September, the government announced the replenishing of the fund with €2 billion in 2022 and €4 billion in 2023, which was approved by a resolution by the lower house of Parliament. These caps should be lifted to make the fund more effective, and contributions more automatic and further windfall tax revenues should be continued to be directed to the Fund.

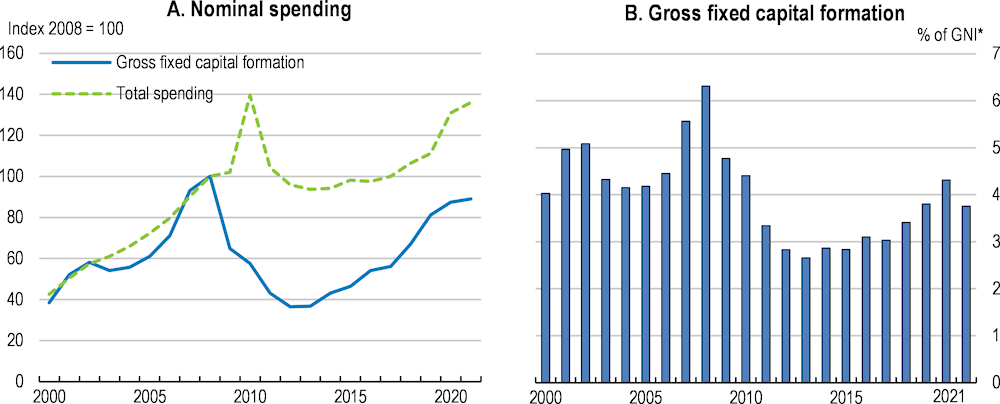

In the past, fiscal policy has been pro-cyclical (Cronin and Mcquinn, 2017). Notably around the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), the boost in spending before and the sharp retrenchment after the peak were pronounced. As is often the case, the retrenchment in spending was felt more severely in investment (Figure 1.11). Not only does pro-cyclicality increase the amplitude of the shock, but it has longer-term impacts through the curtailment of longer-term spending, particularly investment. Some of the challenges confronting policymakers today, such as housing and healthcare, are a legacy of the need to cut spending too quickly during the GFC. In this regard, while revenues are exceptionally strong, recurrent spending should not be allowed to drift up.

Figure 1.11. Government spending has been quite volatile, particularly public investment

Note: Figures are for public spending and public gross fixed capital formation.

Source: Central Statistical Office.

The establishment of the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council in 2012 has provided a constraint on fiscal policy and warnings against excessive spending growth during the economic expansion (Bach, 2020; Jonung, Begg and Tutty, 2016). Output gap-based estimates of the structural balance are too uncertain in a small very volatile economy, such as Ireland, to provide a useable anchor for fiscal policy. As such, the move to the recently introduced country-specific spending rule is a pragmatic approach to bring more predictability to fiscal policy. The planned increase in spending to cushion households from high inflation (see above) will temporarily push spending above the new 5% rule. Going forward, it will be important to return to adherence to the new rule as soon as possible to move fiscal policy onto a more predictable stable spending path to reap the full benefits, including greater resilience to future shocks.

The fiscal framework could be further improved to recognise the impact of tax measures, give it legislative status, capture the full range of general government spending, and link it to debt targets (Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, 2022b). The legislative requirement should be considered as it would imply a clearer specification of the rule and could be linked to a “comply or explain” requirement to improve its effectiveness. It will be important to align these with forthcoming changes to EU fiscal rules. Publishing departmental expenditure ceilings would also improve the transparency of the rule (Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, 2021). In addition, longer-horizon medium-term budgets should be prepared. Moreover, it is essential to regularly update and publish the cost of the government’s major medium-term commitments discussed below (e.g., achieving climate objectives, implementing the health care reform, Sláintecare, and pensions).

1.4.2. Over the longer run, fiscal pressures will emerge

A number of underlying pressures and recent policy changes combine to create threats to fiscal sustainability in the long run. Substantial spending growth is in store for housing, ageing, health and the energy transition. Moreover, changes in international taxation with the agreement of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting in October 2021 may have implications for Ireland’s tax revenues since the agreement calls for a higher statutory income tax rate for large firms registered in Ireland.

Pension sustainability

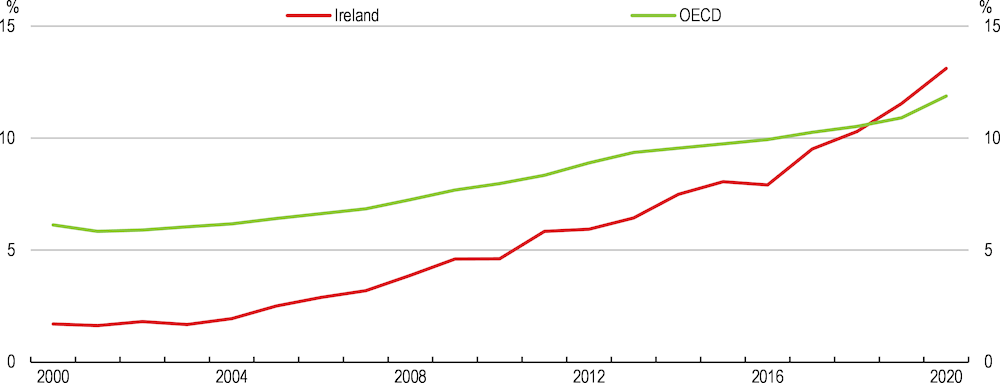

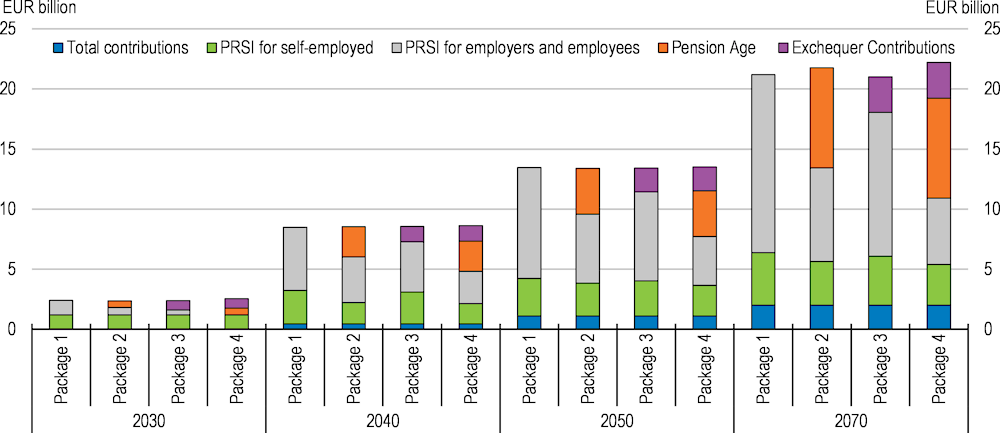

As the population begins to age more rapidly, state pension expenditures are projected to rise from 3.8% of GNI* in 2019 to 7.9% in 2050 and 9.2% in 2070 (Pensions Commission, 2021). Including public sector pensions, pension expenditures would rise from 7.4% of GNI* in 2019 to 12.1% by 2050 (Department of Finance, 2021). Increasing longevity is projected to create an annual shortfall in social security contributions of around €2.4 billion in 2030, which will increase steadily to €13 billion in 2050 (Pensions Commission, 2021).

A planned increase in the state pension age, to ensure future sustainability, by one year to 67 at the beginning of 2021 and to 68 in 2028 was repealed. In addition, a pathway to early retirement was opened by the amendment of existing rules for jobseeker benefits for those required to retire under a contract of employment at 65 through the introduction of a new benefit for 65 year olds in 2021 (one year before the state pension age, with a payment matching that of unemployment benefits but without job-search requirements). A 2021 review by the Pensions Commission set out a preferred reform option (Package 4), which includes gradual increases in the pension age from 2028, higher social security contributions for employees, employers and the self-employed, and other unspecified funding sources (mostly likely further tax increases or spending reductions elsewhere) (Figure 1.12).

The pension reform announced in September puts the burden of adjustment on social security contributions (Pay-related Social Insurance) rather than the state pension age, which is kept at 66. The reform provides incentives for those who continue to work beyond 66 to receive a higher pension payment from 2024, moves towards to a total contributions approach to link pension rates to the number of working years and paid contributions (to be phased in the next 10 years from 2024), and commits to review and adjust the level and rate of increase in social insurance rates every five years. In addition, a number of aspects are designed to improve equity: an enhanced state pension provision for long-term carers from 2024 and a commitment to explore the design of a scheme to provide a benefit payment for people who, following a long working life (40 years or more), are not in a position to remain working in their early 60s. Finally, the reform will introduce measures that allow, but do not compel, an employee to stay in employment until the state pension age, while the Pensions Commission had recommended to avoid setting retirement ages in employment contracts before the state pension age, which could further help close the gap between effective retirement age of 63.6 and the state pension age of 66.

Figure 1.12. Pension reforms should utilise a mix of policy tools

Contributions of policy reforms to projected shortfalls

Note: PRSI refers to pay-related social insurance. All packages include PSRI increases for the self-employed of 4% to 10% initially by 2030, followed by increases of 3.5 percentage point (pp.) by 2040 and 1.1 pp. by 2050 in Package 1, 2.95 pp. by 2040 and 0.15 pp. by 2050 in Package 2, 2.8 pp. by 2040 and 0.9 pp. by 2050 in Package 3, and 2.4 pp. by 2040 and 0.1 pp. by 2050 in Package 4. PSRI increases employers and employees each face are of 0.6 pp. by 2030, 1.6 pp. by 2040 and 1.1 pp. by 2050 in Package 1, 0.3 pp. by 2030, 1.6 pp. by 2040 and 0.15 pp. by 2050 in Package 2, 0.2 pp. by 2030, 1.55 pp. by 2040 and 0.9 pp. by 2050 in Package 3, and no increase by 2030, increases of 1.35 pp. by 2040 and 0.1 pp. by 2050 in Package 4. Packages 2 and 4 include an increase in the state pension age gradually from 2028 to 67 by 2031 and from 2033 to 68 by 2039. Packages 3 and 4 include exchequer contributions of 10% of state pension contributory expenditures.

Source: Pension Commission (2021).

While some measures are in line with the recommendations of the Pensions Commission, two main concerns and uncertainties remain. First, while some of the reforms, such as the move to a total contributions approach, incentives to work to age 70, and possible increases in the taxation of older individuals, can make the pension system more sustainable, there are no calculations of the fiscal impact of the reform. For example, higher pensions for retiring at age 70 could be cost-neutral, depending on the design (Pensions Commission, 2021). Second, the Pension Commission’s report stated that a mix of different measures, including a gradual increase in the state pension age to 67 between 2028 and 2031 and to 68 in 2039, should be part of the policy mix, as using any one of the policy levers by itself to meet the projected shortfalls would require such an extreme change that it would be almost impossible to implement. Keeping the pension age at 66 puts more pressure on the tax system and will increase labour costs. For a worker on a typical annual wage of about €35 000, around €1 800 additional taxes per year would be needed in the coming decades (Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, 2022b). Hence, an increase in the pension age should be part of the reform package.

In the medium term, a more ambitious change to make reforms long-lasting, without a need for constant political negotiations over short-term solutions, would be to adopt an automatic adjustment mechanism, as some EU countries have (e.g., Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands), to help lower uncertainties affecting financial sustainability. For example, the introduction of an automatic link between the retirement age and life expectancy would lower pension spending by one percentage point of GDP in Ireland in 2070 (European Commission, 2021a).

Health

Along with pension spending, the healthcare sector is a major driver of public spending in the longer term. The impact of ageing is projected to raise health and long-term care spending from around 8.5% of GNI* in 2019 to as much as 13.2% in 2050 (Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, 2020). In the short run, the costs of implementing Sláintecare to reform the healthcare sector by moving away from a largely hospital-based system to one that will better integrate primary, community and long-term care, reducing waiting lists and addressing the legacy of underinvestment (see Chapter 2) are weighing on public finances.

Climate change, housing and infrastructure

The government has committed to meeting a net-zero greenhouse gas emission target by 2050, with an interim target for 2030. The National Development Plan has identified avenues for green investment (e.g., energy efficiency in buildings, sustainable mobility), while around half of the recovery and resilience plan funds are allocated to the green transition (see below). As the government is still elaborating the policies to meet these targets, the full fiscal implications cannot be quantified yet. However, these policies are likely to involve stepping up green public investments and a variety of incentives for households and businesses to take action. The 2021 Climate Action Plan indicates that investment needs of around 2% of GNI* annually would not yield a positive return and by implication require government support or regulation (Government of Ireland, 2021b). Other estimates highlight that the cost of meeting the 2030 targets could be higher if sectors where emission reductions are difficult to achieve in the short to medium run, such as agriculture, are not required to make the same abatement effort. In these conditions, required public spending to achieve much larger cuts in emissions from energy could double (FitzGerald, 2021).

The Housing for All Strategy has committed €20 billion over the next five years to address the housing shortage by improving zoning, land availability, and provision of social and affordable housing (see below for details). In addition, spending on infrastructure to meet the greenhouse gas emission reduction targets will require substantial public spending. This includes putting in place the infrastructure to harness the potential for renewable energy and increase the use of electrification in both the transport and residential and commercial buildings. As part of the National Development Plan, the government plans to increase capital spending to 5.4% of GNI* and keep it roughly at that level to address some of the key infrastructure needs. This is about a one percentage point increase from 2020 and if maintained would help limit the pro-cyclicality of investment spending. This would potentially boost output by 0.7 to 0.9% by 2030 (Conroy, Casey and Jordan-Doak, 2021). However, the number of construction workers is constrained and the competing demands of increasing housing supply and climate change mitigation may bid up prices in the sector absent efforts to boost supply.

Taxation of multinational enterprises

In October 2021, Ireland joined the Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting. This will mark a sea change with Ireland obliged to raise its corporate income tax rate from 12.5% to 15%. The current Irish corporate income tax rate was phased in starting in 1996 (there was a special rate for manufactures of 10% and before that, an exports profits tax relief meant the effective rate was 0%). The international tax agreement is set to be implemented in 2023 at the earliest. The revenue consequences are uncertain, but government estimates suggest a revenue loss of around €2 billion compared with business as usual once Pillars 1 and 2 are fully implemented.

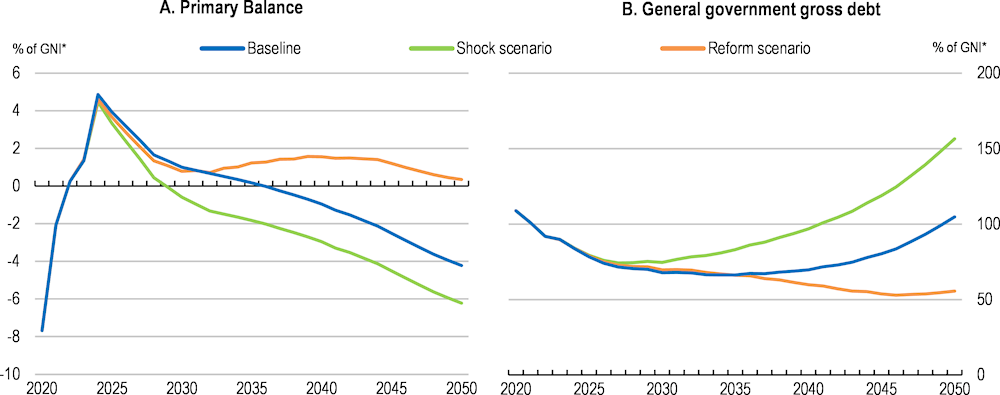

Debt sustainability analysis

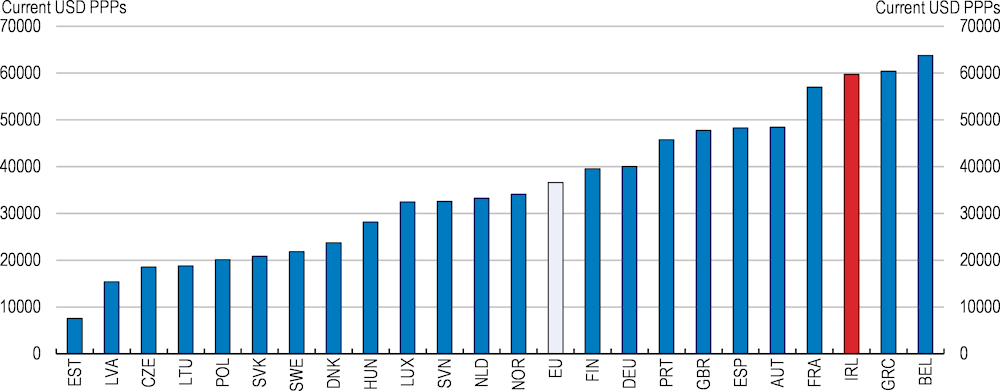

Debt levels are already elevated, at 100.8% of GNI* in 2021 (as against an EU average of 75.1% of GDP). On a per capita basis, they are quite high compared with other EU countries (Figure 1.13), suggesting limited room for further increases without heightening risks to fiscal resilience. While the short-term outlook for fiscal policy is relatively benign and debt levels are projected to decline, in the longer term, as the various spending and revenue pressures begin to materialise, the picture is more worrying. According to OECD projections, public debt will not stabilise by 2050 without significant reforms (Figure 1.14).

Figure 1.13. Debt on a per capita basis is elevated

Gross government debt per capita, 2021 or latest available data

Note: Data for the United Kingdom refer to 2020.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD, National Accounts database.

Figure 1.14. Reforms are needed to ensure debt sustainability

Note: The baseline scenario is calibrated on OECD long-term model simulations and Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (2020) spending assumptions, adjusted for recent fiscal outturns. The shock scenario assumes a gradual erosion of tax revenue (€4 billion per annum by 2032, at 2020 constant prices). The reform scenario builds on the shock scenario assuming pension reforms following package 4 proposed by the Pension Commission, an improvement in public sector cost efficiency (mainly in the health sector phasing in 15% gain in spending efficiency over 20 years). All scenarios include ageing costs.

Source: OECD secretariat calculations.

Table 1.5. Past OECD recommendations on fiscal and pension policies and actions taken

|

Recommendations in past surveys |

Actions taken since 2020 |

|---|---|

|

Use windfall corporate tax revenues to pay down general government debt or to further build up the Rainy Day Fund. |

As set out in the Programme for Government, windfall gains, such as excess corporation tax receipts, the NAMA surplus and the drawdown of the Rainy Day Fund, have been utilised to reduce the Exchequer borrowing requirement. In September 2022, the government announced the replenishing of the Rainy Day Fund, renamed National Reserve Fund, with €2 billion in 2022 and €4 billion in 2023 |

|

Delink the Christmas bonuses of welfare recipients from revenue outturns and systematically include these amounts in government budget plans. |

No action taken. |

|

Create domestic fiscal rules based on measured modified gross national income (GNI*) and an estimate of potential output growth that is tailored to the Irish context. Continue to set, and report progress against, medium-term government debt targets as a share of GNI*. |

An expenditure rule was introduced in 2021, allowing permanent expenditure to increase in line with the economy’s estimated trend growth rate. Tax revenues will be allowed to fluctuate in accordance with the economic cycle without amending the ceiling. Recent budget and summer economic statements only reported government debt as a share of GNI*. |

|

Streamline the Value Added Tax system, moving from five rates to three. |

Options to streamline the VAT system, including the reduction in the number of VAT rates, are in discussion as part of the Tax Strategy Group papers. |

|

Reassess property values more regularly for the purposes of calculating the local property tax. At the same time, protect those low-income households adversely impacted. |

The Finance (Local Property Tax) (Amendment) Act 2021 provides that property valuations will be reviewed every four years, increases the income threshold for tax deferrals and reduces the interest rate on deferred taxes. |

|

Implement the main proposals of the Sláintecare report, establishing a single-tiered health service that provides universal access to primary care. |

Progress in 2021 includes additional beds and primary care centres, the new general practitioner’s direct access to diagnostics scheme, increased funding for home support, reduction in waiting lists and the establishment of 49 Community Healthcare Networks, 15 specialist teams for older persons and two chronic disease management teams. |

|

Ensure that all legislative requirements for the National Service Plan are fulfilled by the Health Service Executive. |

An additional weekly flash reporting sets out a close to real time estimate of the cumulative expenditure on each COVID-19 measure and a monthly working capital report has been instituted by the Health Service Executive to the Department of Health. |

|

Index future increases in the state pension benefit to inflation. Implement the planned increase in the state pension age to 68 by 2027 and link changes to life expectancy thereafter. |

In September 2020, the government announced that a smoothed earnings method to calculate a benchmarked/indexed rate of State pension payments would be introduced as an input to the annual budget process from 2023. The legislative provisions for increasing the State Pension Age were repealed in the Social Welfare Act 2020 and are not part of the pension reform announced in September 2022. |

1.5. Labour and product markets meeting the economy’s needs

The national recovery and resilience plan (Box 1.4) includes a number of initiatives which can improve employment (boosting digital skills and improving active labour market policies for jobseekers) and productivity growth of domestic firms (supporting their digitalisation, reducing barriers to investment, such as regulatory barriers to entrepreneurship, housing affordability and skill shortages). According to calculations by the European Commission, not including the impact of structural reforms, the plan can lift Ireland’s GDP by 0.3-0.5% by 2026 and create 6 200 additional jobs (European Commission, 2021b). Ireland also published an Economic Recovery Plan in 2021, which among other initiatives, aims to create 50 000 additional training places by 2025 to boost employment (Government of Ireland, 2021c). Box 1.5 quantifies the potential impact of some of the structural reforms discussed in this Survey.

Box 1.4. Ireland’s recovery and resilience plan

Ireland’s recovery and resilience plan (€989 million in grants, 0.3% of 2019 GDP) includes 25 measures (16 investments and 9 reforms) and is structured around three axes:

1. Green transition (52.4%): to encourage a shift from private cars to rail transport, promote energy efficiency in residential and public buildings and businesses, and support bio-diversity (restoration and rehabilitation of wetlands to change land use from peat extraction to carbon sequestration).

2. Digitalisation (29.4%): to support the digitalisation of the public sector, especially the healthcare system, the digitalisation of SMEs and the promotion of digital skills (e.g. provide connectivity and ICT equipment to disadvantaged learners in schools).

3. Social and economic recovery and job creation: to support access to the labour market and upskilling of workers with a focus on green and digital skills, boost the quality of higher education (e.g. new education and training programmes in technological universities, regional innovation hubs) and lifelong learning, to increase the supply of social and affordable housing and support the fight against money laundering.

Source: Government of Ireland (2021d), National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Dublin.

1.5.1. Boosting employment and labour mobility

Labour force participation at around 80% (for those aged 25-64) is above the OECD average and well above the rates prevailing in the 1990s. Following the pandemic, participation rates increased for many groups, such as female, young and older workers, likely reflecting cyclical factors, tight labour markets and remote working, but they remain low for those with lower educational attainment. At the same time, job vacancies remain high at 1.5%, but lower than the EU average of 2.9%. According to an October 2021 survey, difficult-to-fill vacancies were high in life sciences, information technology, construction, health and financial activities (SOLAS, 2021). Skill mismatches play a role as do disincentives embedded in the tax and benefit system and in some cases barriers to geographical mobility, although the rise of remote work could help the latter (SOLAS, 2022). Addressing these issues would help raise participation and for some groups reduce the incidence of poverty.

Changes in the structure of the economy after the pandemic could complicate labour force attachment as sectors that often serve as pathways into employment, such as the hospitality sector, may slim down. Other uncertainties include the extent to which international migration contributes to labour force growth in the future. Ukrainian refugees can help alleviate some labour shortages if they are well integrated into Irish labour markets. Around 64% of them are of working age (aged 20-64), of which 68% are women. Ireland has provided them with work rights, access to housing and health, social welfare payments where appropriate, as well as vocational training and job assistance to speed up their integration (OECD, 2022a). However, the employment rate of refugees remains low at 14.8% so far, with language as the main barrier to labour market entry.

Box 1.5. Potential impact of reforms on growth and the fiscal balance

Table 1.6 broadly illustrates the growth impact of some key structural reforms proposed in this Survey. The fiscal impacts presented in Table 1.7 do not take into account indirect effects, such as those induced by the positive impact of the reforms on growth and public revenues, and some recommendations are not quantifiable.

Table 1.6. Potential impact of selected proposed reforms on GDP per capita

|

Policy |

10 year effect |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Improve the business environment (Section 1.5.2) |

Improve the OECD PMR indicator by 0.2% to the average of the quartile of countries with the most competition-friendly competition policy settings. |

1.5% |

|

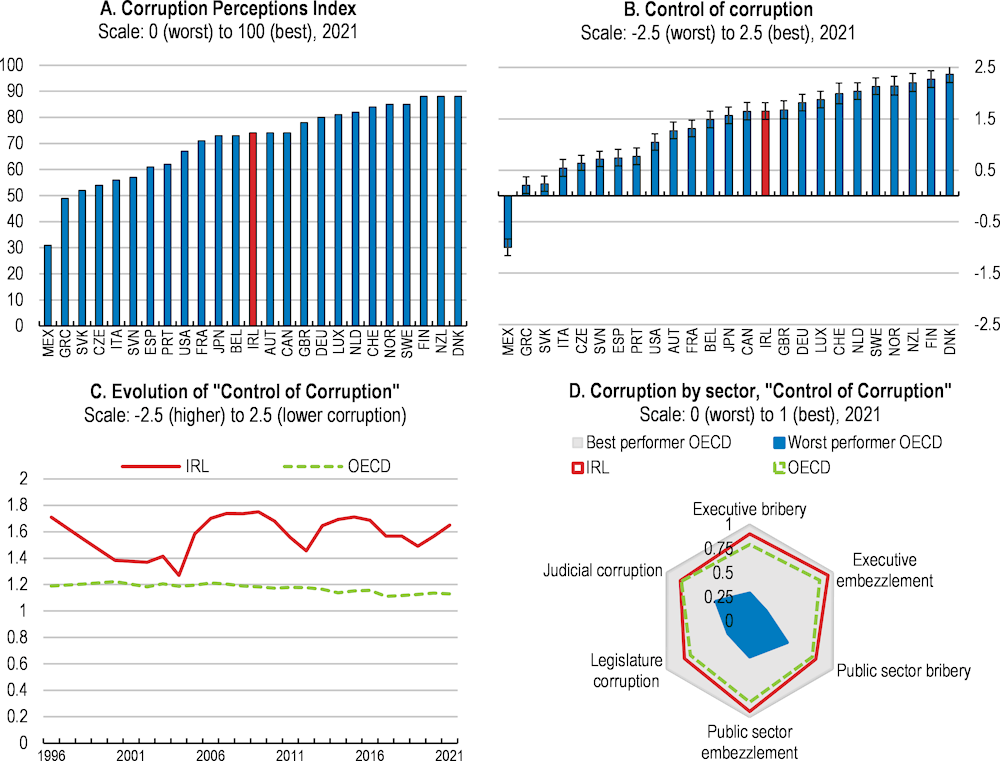

Address remaining gaps in corruption (Section 1.5.2) |

Improve the institutional framework conditions (rule of law) by 0.1% to the OECD average. |

1.4% |

|

Increase training and employment (Section 1.5.2) |

Increase ALMP spending per unemployed as a % of GDP per capita by 0.6% to the OECD average |

0.9% |

|

Total |

3.8% |

Note: These estimates are illustrative. The impact on the level of GDP per capita is estimated using historical relationships between reforms and growth in OECD countries. The model does not capture policy-induced changes in deep-rooted preferences like risk aversion and their subsequent effects on economic variables. These numbers are similar to those in the 2020 Economic Survey of Ireland.

Source: OECD calculations based on (Égert and Gal, 2017).

Table 1.7. Illustrative direct fiscal impact of selected recommended reforms

|

Reform |

Medium-term fiscal impact (savings (+)/ costs (-)) (% of GDP) |

|---|---|

|

Improve health spending efficiency (Chapter 2) |

+1% |

|

Support to new training programmes (Section 1.5.2) |

-0.6% |

Note: The policies are to: i) close half the gap of current health spending as a share of GNI* in Ireland with the OECD average health spending as a share of GDP; and ii) increase ALMP spending per unemployed as a % of GDP per capita by 0.6% to the OECD average.

Source: OECD calculations.

Providing the skills needed

Ireland is nearing the end of a 10 year skills strategy in 2025 to create a well-trained and skilled labour force capable of responding to the needs of the economy. An OECD Skills Strategy project is currently assessing how the strategy might need to be adapted to ensure that it is still fit for purpose (OECD, forthcoming). The evolution of the economy in recent years has shown growing demand in some sectors, not least construction more recently, but also in high-tech activities. The implications of the Climate Action Plan dictate that some sectors of the economy will diminish in importance and workers will need to change jobs, pointing to the importance of helping workers acquire new skills and find new employment opportunities. Hence, the focus of the recovery plan on strengthening access to training, particularly for digital skills, is welcome.

The public employment services have been given more resources and reorganised to help workers into employment more effectively. Greater use of digitalisation during the pandemic has allowed online interactions, which a majority of jobseekers prefer and helps tailor programmes to the individual. Online meetings have also facilitated interactions with a broader range of potential employers. As an emergency response to COVID-19 pandemic, eligibility for online further education and training programmes (e.g., e-College) were extended. In the construction sector, training efforts are carried out with employers and targeting the skills in short demand and aiming to bring greater innovation into the sector. Since 2016, 41 new ones have been added to the existing 25 more traditional craft apprenticeships, including one in the healthcare sector, and Budget 2023 includes additional support for craft apprenticeship programmes. Whereas in the past apprenticeships were mainly taken up by males, the take-up is now more gender-balanced. The developments in job search and training are laudable and should be evaluated over time to ensure they do contribute to better job outcomes and the best use of public funds. This can inform the elaboration of the next national skills strategy. Innovative training, however, should not become a barrier to entry, for example by creating occupational licensing.

Boosting female labour force participation