Michael Koelle

OECD Economic Surveys: Israel 2023

2. Addressing labour market challenges for sustainable and inclusive growth

Abstract

High employment growth has sustained Israel’s high GDP growth in recent decades, but demographic change and labour market duality put future growth at risk. Policy action is required to stimulate employment and raise labour productivity, especially among population groups with weaker labour market outcomes. A particular concern is closing employment gaps of Haredim and Arab‑Israelis and ensuring gender equality in the workplace, which would simultaneously improve opportunities for all Israelis and the aggregate labour productivity of the economy. This will require setting appropriate work incentives and providing better support for working parents; improving skills at all stages of the learning cycle; as well as increasing mobility and improving reallocation towards high productivity jobs and firms, in particular in the high-tech sector.

Demographic change and labour market duality put future growth at risk

Demographic developments challenge future growth

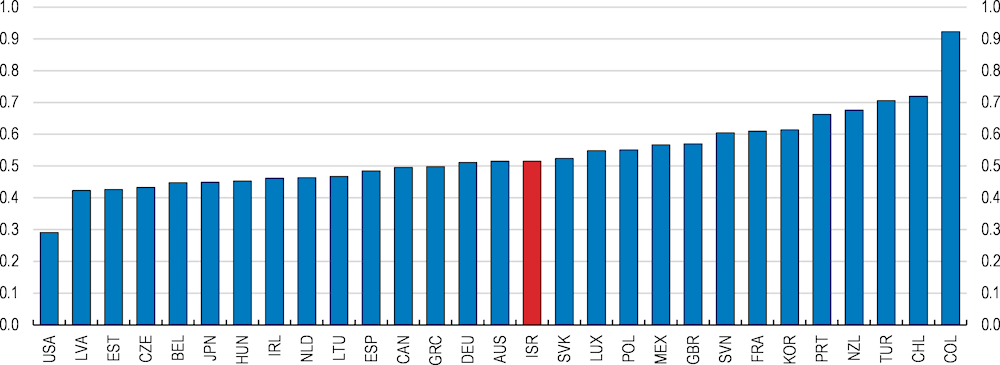

Israel’s high GDP growth in the last three decades was largely driven by growth in employment (Figure 2.1). Employment has contributed about ⅔ to growth, reflecting the absorption of immigrants from the former Soviet Union in the 1990s and strong population growth. In addition, broad population segments were integrated into the labour market. The employment rate has increased by about 10 percentage points in the last two decades and is around the OECD average. However, overall employment growth has been on a slow but constant downward trend for three decades, and has started to decline more strongly in the last few years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic. Labour productivity growth has not been enough to compensate for the slowdown in employment growth, reflecting the persistent productivity gap of Israel compared to other OECD countries (see Chapter 1).

Figure 2.1. Employment growth has been driving Israel’s growth since the 1990s

Contributions to GDP growth, percentage points

Note: Productivity is calculated as GDP per hour worked.

Source: OECD Productivity database; OECD National Accounts database; and OECD calculations.

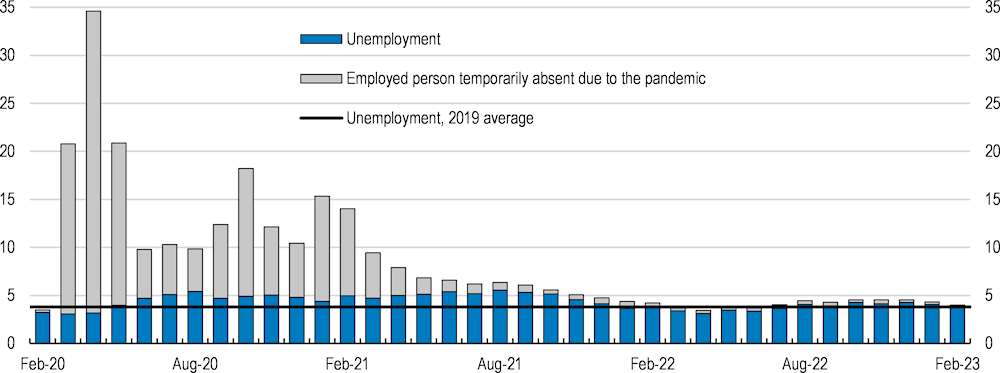

The labour market has recovered from the pandemic, helped by strong policy support. The unemployment rate has fallen to its pre-pandemic level and the share of people who were temporarily absent from work due to Covid-19, which reached heights of 30% during the first wave of the pandemic, fell close to zero in early 2022 (Figure 2.2). The employment rate also recovered to its pre-pandemic level, suggesting that, unlike in some other OECD countries, the pandemic seems to have had no lasting effects on labour force participation. The swift labour market recovery was helped by decisive policy support, notably the furlough scheme that allowed workers put on temporary lay‑off to receive income support without being outright dismissed. Fiscal support to firms and the strength of the high-tech sector throughout the pandemic also contributed to the labour market recovery.

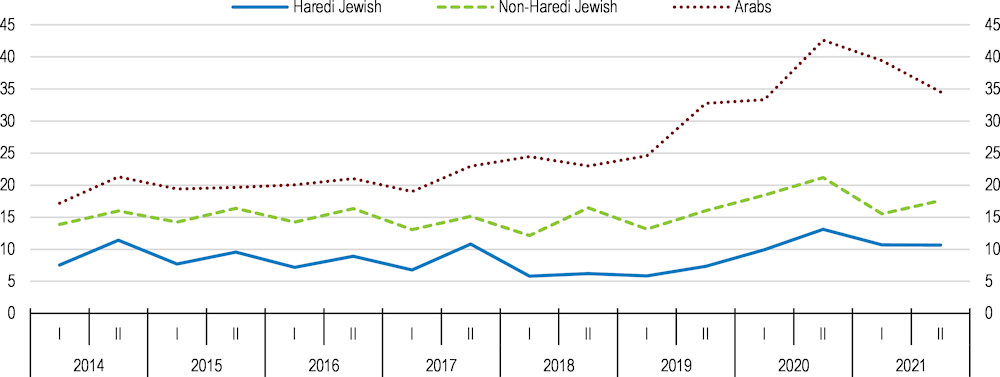

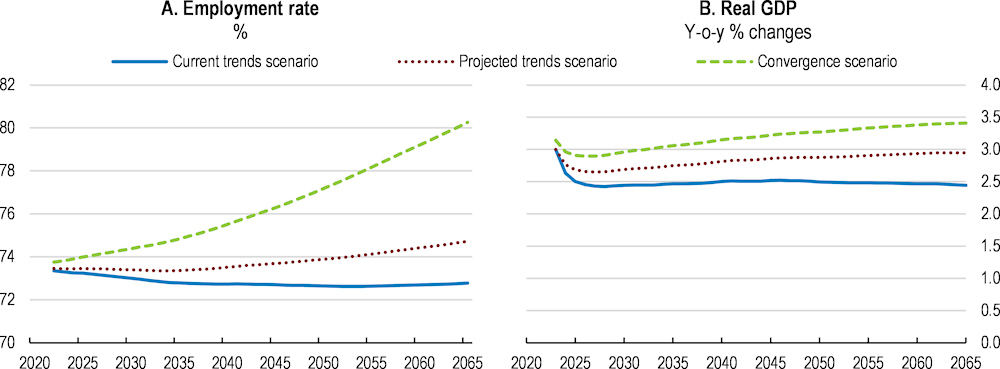

Demographic change puts past achievements at risk. The share of population groups with weaker labour market outcomes is projected to increase dramatically in the coming decades, with the combined share of Arab-Israelis and Haredim rising to 50% of the working-age population by 2060, from 30% today. Ministry of Finance (2019[1]) simulations suggest that under current trends, this would bring down potential GDP growth to around 2.5% per year, from around 4% in the last two decades (Figure 2.3). It would also pose substantial risks to debt sustainability due to lower tax bases and less growth (see Chapter 1). The growth slowdown will be driven both by a stagnating quantity of employment (around the current rate) and by a deteriorating quality of employment in the growing population segments. By contrast, if all the gaps in employment and labour productivity were closed by 2065, long-run growth could be maintained at around 3.5% per year, not far from current levels. The key to unlocking the potential for continued high growth rates of the Israeli economy therefore lies in addressing structural challenges in the labour market, including disparities in employment, wages and labour productivity.

Figure 2.2. The labour market recovered quickly from the pandemic

As percent of the labour force

Note: The "Employed person temporarily absent due to the pandemic" category includes employees on unpaid leave, employees who were absent during the week due to reduced workload, work stoppage or other reasons related to the pandemic and excludes quarantined persons.

Source: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics; and OECD calculations.

Figure 2.3. Demographic change puts pressure on future employment and growth

Note: Simulated employment rates and real GDP growth under current population projections and different scenarios with assumptions about future employment rate and wage developments in each of the following demographic groups: Arab-Israeli men, Arab-Israeli women, Haredi men, Haredi women, non-Haredi Jewish men, non-Haredi Jewish women. The current trends scenario assumes trends of the last decade; the projected trends scenario uses projections from Ministry of Finance long-term growth model; and the convergence scenario assumes full convergence of employment rates and wages in each group to the level of non-Haredi Jewish men by 2065.

Source: Ministry of Finance of Israel (2019), “On the economic consequences of the integration of ultra-Orthodox and Arabs in the labour market in the coming decades”.

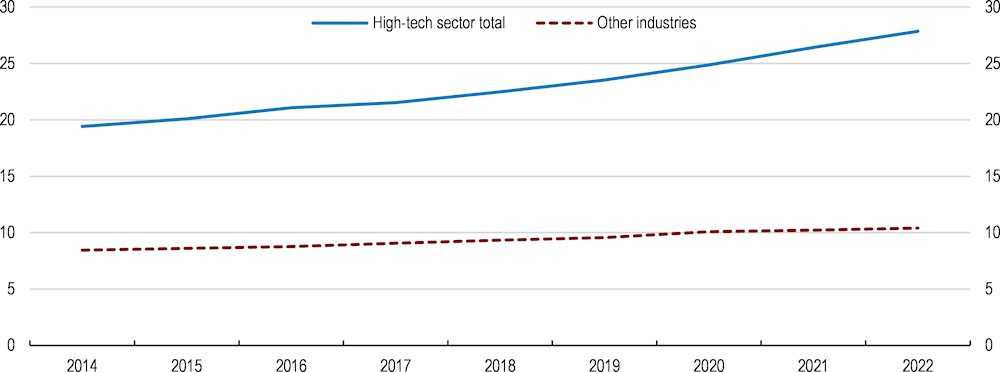

Labour market disparities are large

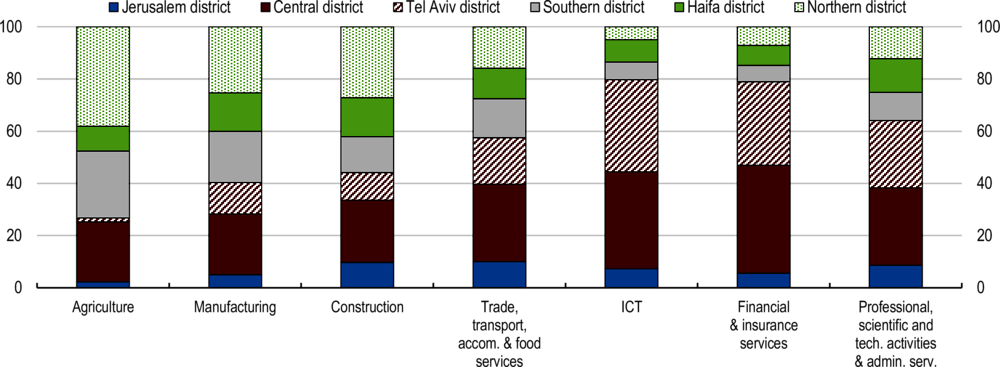

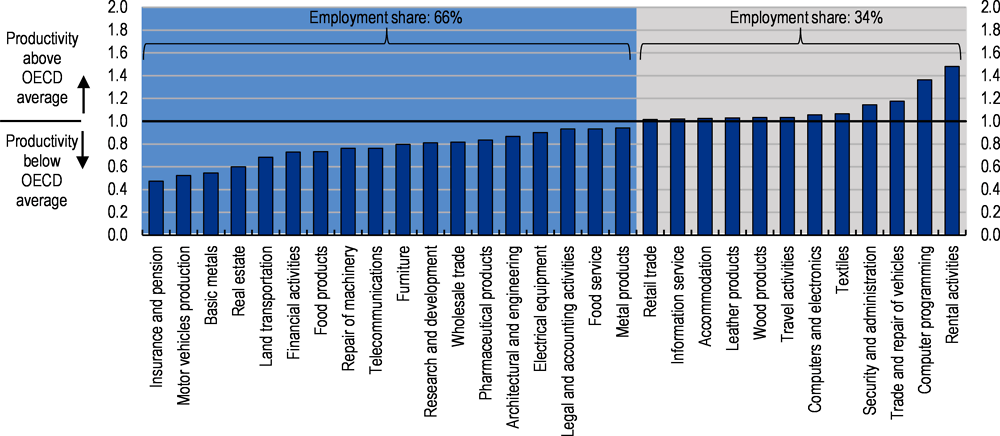

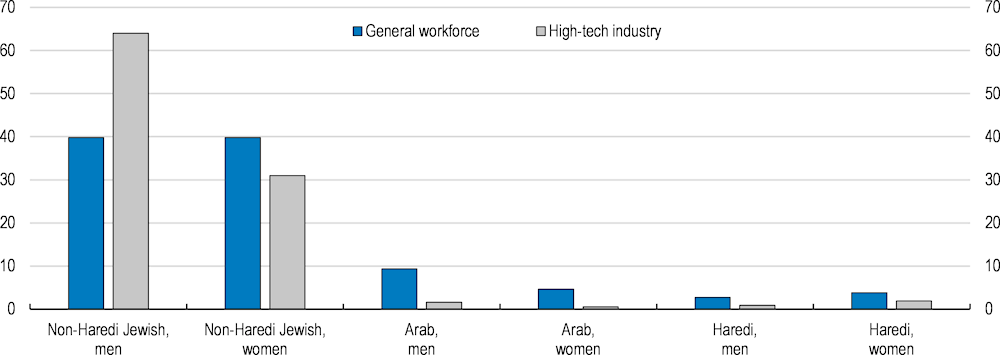

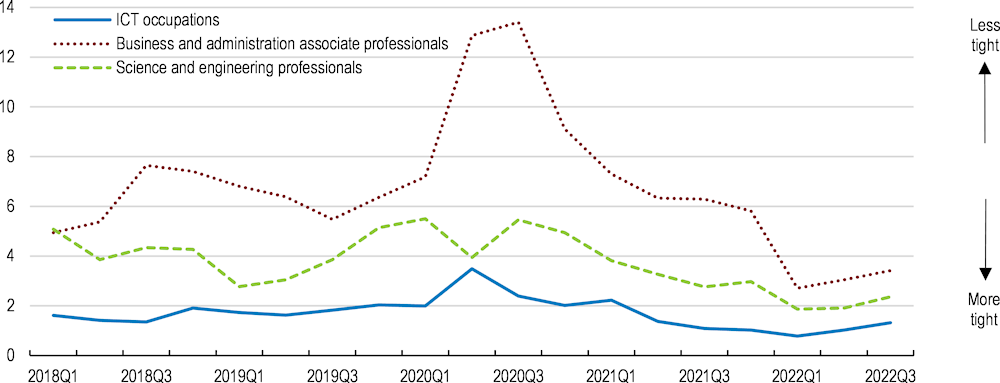

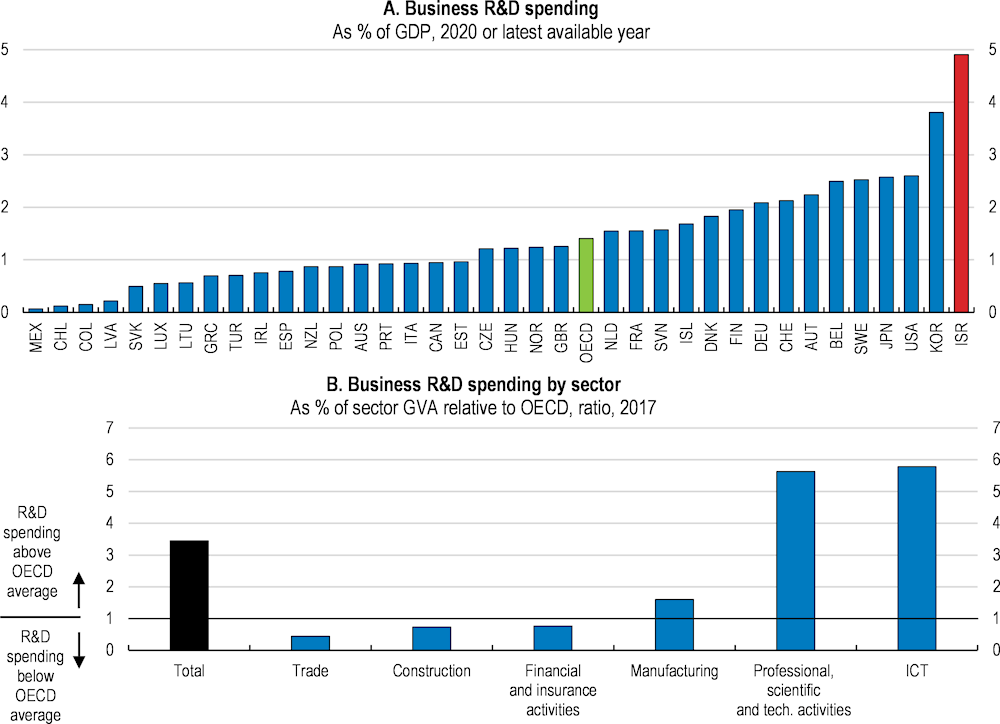

Israel’s labour market is shaped by its dual economy. Highly competitive industries, in particular the vibrant high-tech sector, coexist with low-productivity, low-wage sectors that employ the majority of Israelis (Figure 2.4). The high-tech sector accounts for about 12% of all employment, 15% of GDP, half of exports and a quarter of personal income tax receipts (Israel Innovation Authority, 2021[2]). The high-tech sector has weathered the pandemic well thanks to increased global demand for digital services, its ability to move to remote working more easily than other sectors, and government efforts to facilitate its activity during the lockdowns. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may provide another demand push for the digital security services and defence equipment that the sector is particularly renowned for. Securing sufficient talent to meet demand is the main bottleneck to continued expansion of the sector, and persistent labour shortages have contributed to large and rising wage premia.

Figure 2.4. Employment is still concentrated in low-productivity sectors

Israel/OECD relative productivity ratio

Note: Productivity is measured as value added per employee. Relative productivity for each sector is defined as the productivity of the sector in Israel divided by the average productivity of the same sector in OECD countries. Data is for 2017 and is limited to manufacturing and market services (respectively, categories C and G-N according to the ISIC Rev.4 classification).

Source: Bank of Israel; Israel Central Bureau of Statistics; and OECD calculations.

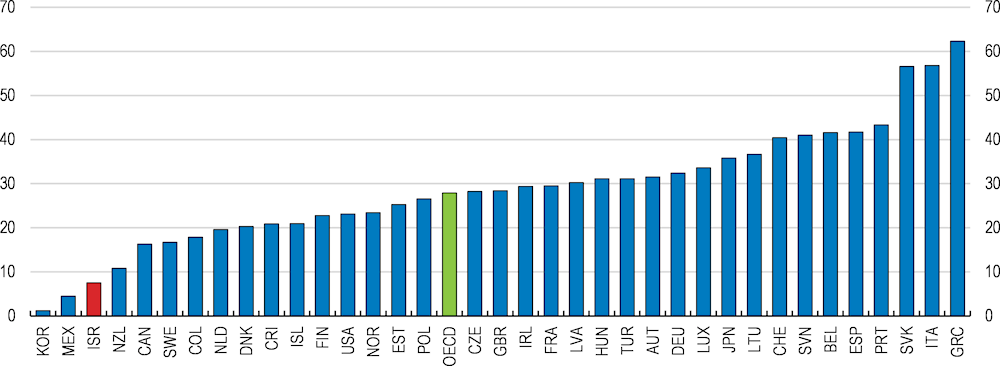

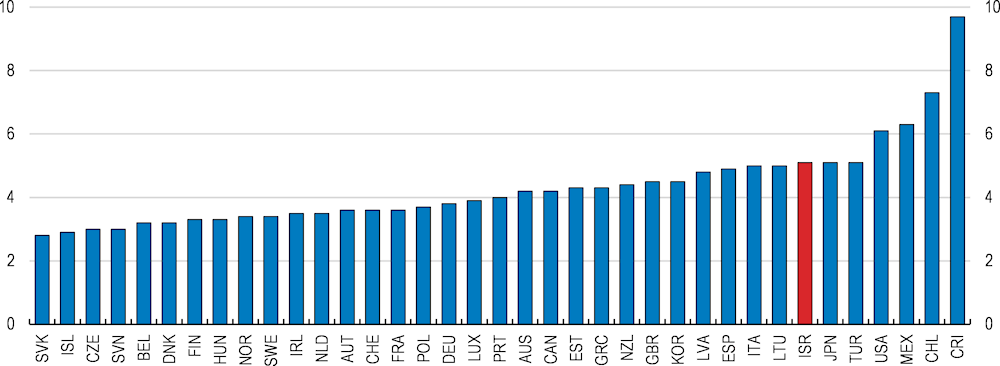

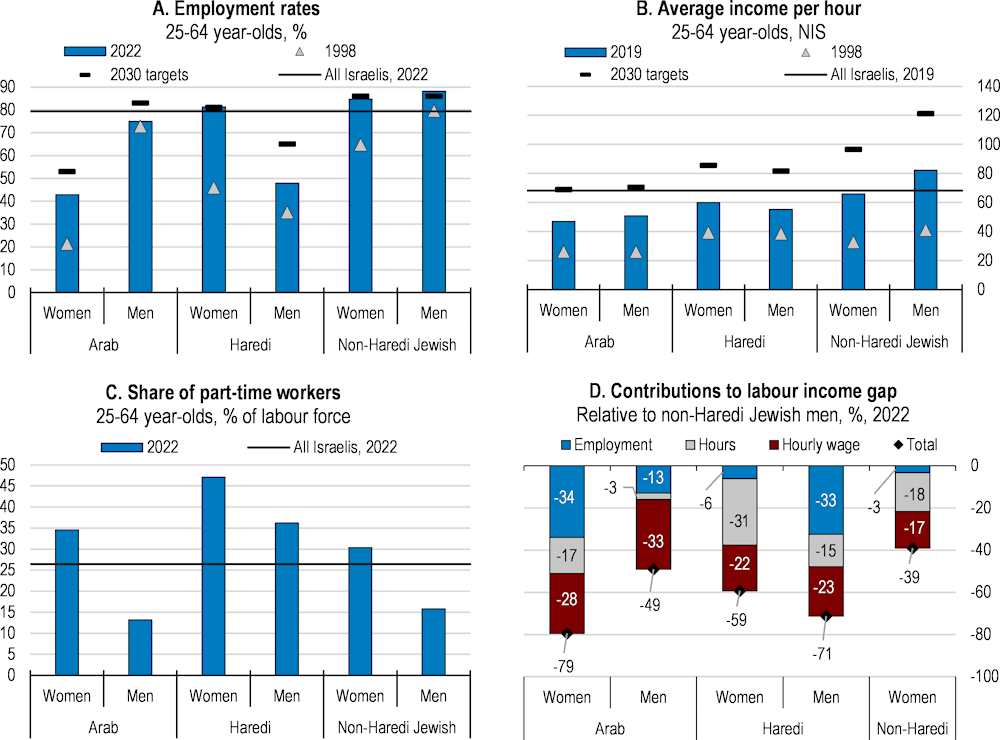

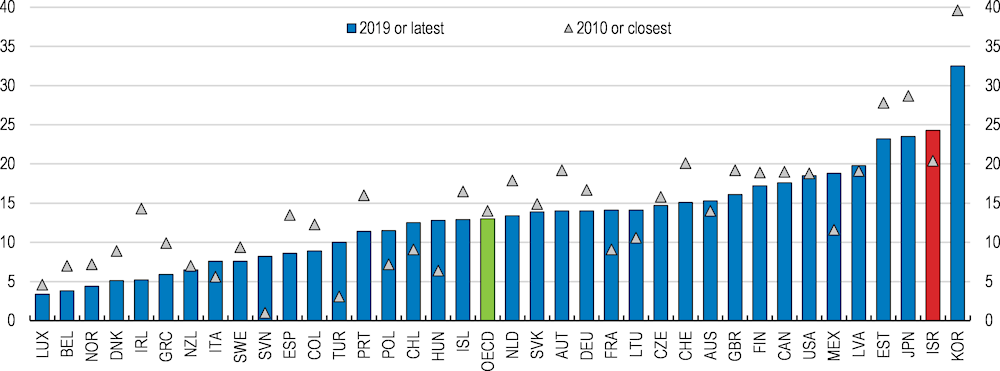

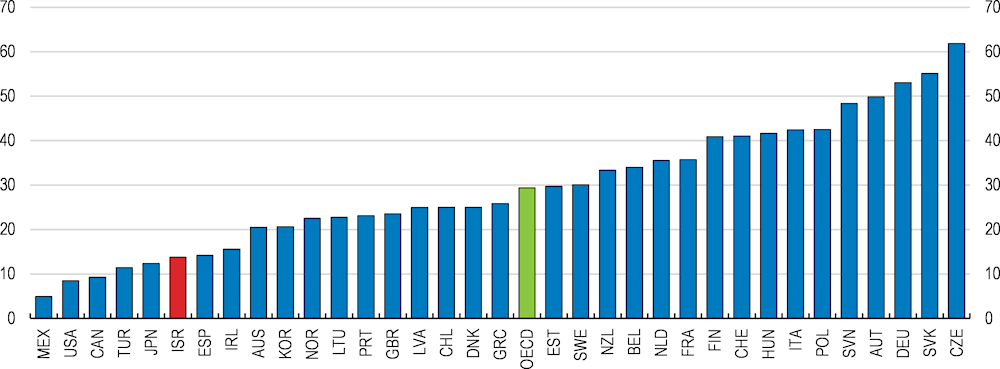

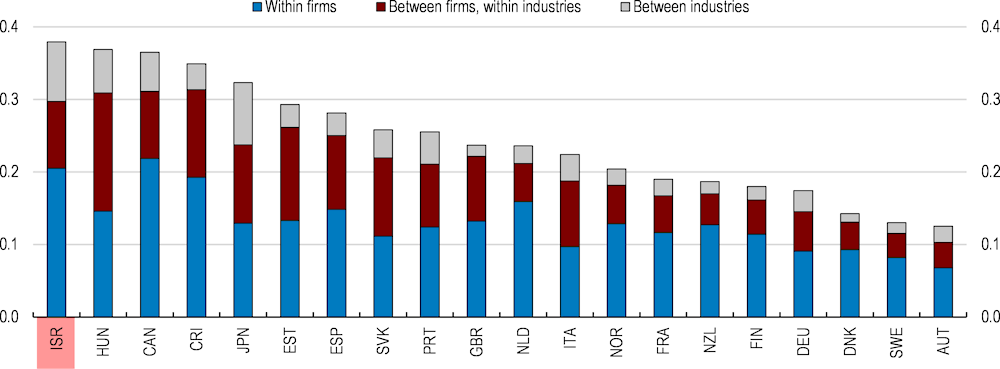

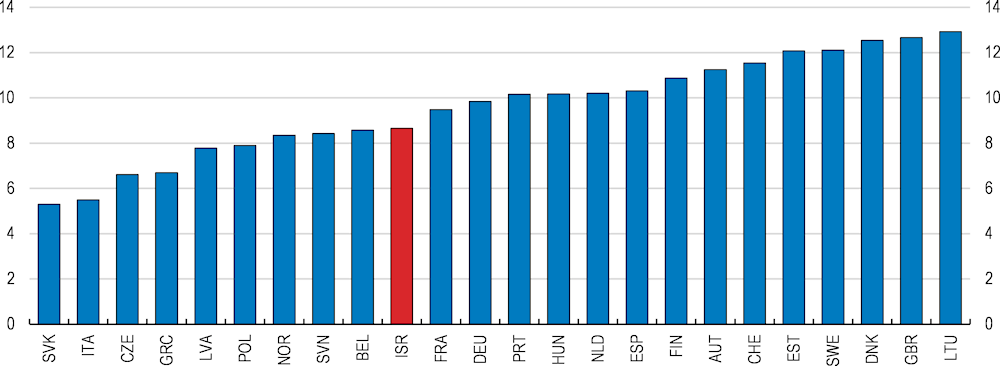

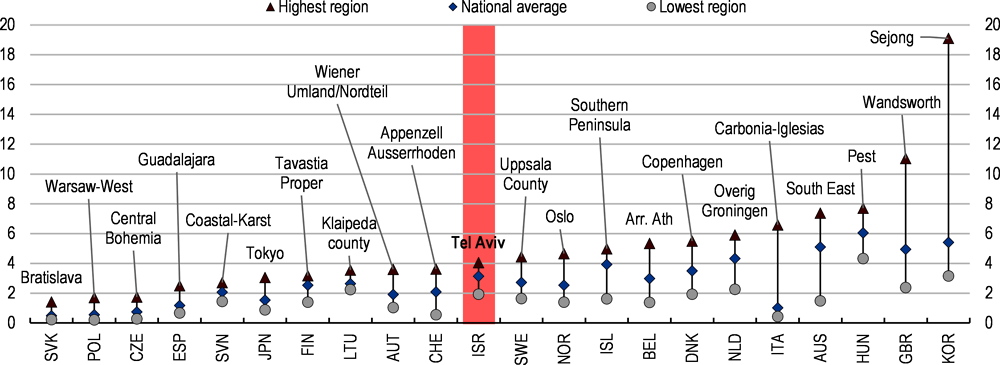

Income inequality in Israel is higher than in most other OECD countries (Figure 2.5). This is a result of business sector duality, a low degree of redistribution through the tax and transfer system, and inequalities in labour market outcomes across different population groups, defined by gender and ethno‑religious status (Figure 2.6). Large gaps exist in all dimensions of labour market participation: employment rates, hours, and hourly wages. However, as Panel D of Figure 2.6 shows, each population group faces particular dimensions where they are especially underrepresented in the labour market. Policies to improve labour market integration therefore need to target the specific constraints and barriers that each group faces. Moreover, there is substantial heterogeneity even within population groups, for example in skill levels and trends in education, that will partly require solutions to be further differentiated.

The weak labour market outcomes of the Haredim, especially men, largely reflect a different valuation of work and secular education relative to spiritual activities (OECD, 2020[3]; OECD, 2018[4]) as well as community-specific incentives set by public policy that discourage labour force participation. Haredi men are expected by their community to devote their time fully to religious studies. Especially Haredi boys are exposed to little teaching of the national core curriculum, which limits their further educational and career opportunities. Haredi men in religious seminaries (‘yeshivas’) can receive government stipends and are exempt from otherwise compulsory military service. Many of the Haredi men who work do so in part‑time jobs within the community, for example as yeshiva teachers or scribes. The labour market situation of Israeli Haredim contrasts with that in other countries such as the United Kingdom or the United States, where labour market participation and incomes are much closer to the general Jewish population (Pew Research Center, 2013[5]). Haredi women dramatically increased their labour force participation from 50% to 80% in less than two decades, following cuts to non-work household benefits in the early 2000s. As a result, many Haredi women have become the main earners in their households, and earn slightly higher hourly wages than men. This occurred despite little decrease in fertility, and is partly facilitated by the flexible timing of their husbands’ study. However, wage levels of Haredi women still lag behind non-Haredi Jewish women, and part-time work is more common than in other population groups.

The main challenges for this population group are twofold. First, bringing more Haredi men into the workforce is a crucial policy challenge in Israel in light of the demographic trends, which indicate an increase in the share of Haredim in the working-age population from 10% today to 30% by 2060. This objective requires removing barriers and policy disincentives to labour force participation as well as equipping Haredi men with better market-relevant skills by improving their participation in core studies. Second, policies should aim at increasing employment quality for all Haredim, particularly for women, improving their job opportunities in the labour market and productivity in the workforce, through life-long learning and work placement programmes targeted at the community.

Figure 2.5. Income inequality is high

Disposable household income interdecile ratio (P90/P10), working age population, 2019 or latest available year

Note: The P90/P10 ratio is the ratio of the upper bound value of the ninth decile (i.e. the 10% of people with highest income) to that of the upper bound value of the first decile.

Source: OECD Income Distribution database.

Arab-Israelis face gaps in almost every dimension of the labour market, which need to be addressed by a combination of policies in many different areas. The wage gap between Arabs and Jews has been widening since the early 2000s, and on average, the hourly wage of Arab-Israelis is about half the hourly wage of non-Haredi Jewish men. Average hourly pay is equally low for both Arab men and women. The low gender wage gap among Arab-Israelis can partly be explained by the large share of minimum wage earners, among both men and women (Larom and Lifshitz, 2018[6]). The rapid improvement in Arab-Israeli women’s education in recent years has been associated with rising employment (and falling fertility rates), but employment rates and hours worked still remain the lowest among all groups. Employment rates of Arab-Israeli men fell before the pandemic by about 5 percentage points, largely due to reductions in employment in the construction sector (MoF, 2021[7]). As discussed in detail below, the large labour market gaps of Arab-Israelis reflect significant differences in educational outcomes; an underrepresentation in high-paying occupations and sectors; a lack of Hebrew fluency and English language skills among many Arab speakers; geographical disparities given the residential segmentation of Israeli municipalities; and partly also possible discrimination. Significant improvements of the labour market situation of Arab-Israeli requires policy interventions and structural reform in each of these areas.

Figure 2.6. Large labour market gaps exist in employment, hours and wages

Note: In Panel A, the official 2030 government targets presented refer to the age groups 25-66.

In Panel B, the 2030 government targets should be considered as illustrative. In this respect, the official 2030 government targets refer to the age group 25-39 and are expressed as average rate of annual increase in the nominal monthly wage. These have been applied to the 2019 average income per hour for Arab Men and Haredi Women, aged 25-64. For Non-Haredi Jewish men and women, targets have been estimated by the OECD (as an average of the historical growth rates in hourly income over the last decade) and applied to the 2019 average income per hour of the respective categories. The latter two were also applied to the Haredi men and Arab women categories, as the government indicated that wage growth for these two categories should have similar rates of increase as the Non-Haredi Jewish men and women, respectively.

In Panel D, data for hourly wage refer to 2019. Contributions are illustrative and only concern direct contribution of each dimension, without considering interaction effects between dimensions. The size of each contribution is proportional to the gap in this dimension relative to all other dimensions for the same demographic group.

Source: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics; and OECD calculations.

The five-year plan for economic development of the Arab-Israeli community provides a comprehensive framework to coordinate a range of policy actions in this respect (Box 2.1). Importantly, it provides a package to simultaneously address multiple barriers to integration that interact with each other, such as deficits in education, housing, transport and employment. As experience from other OECD countries shows, a key success factor in raising the living standards of minority groups is the degree to which special programmes are integrated into mainstream policy (OECD, 2019[8]). For example, the Living Standards Framework of the government of New Zealand provides a comprehensive assessment tool of living standards and integration into society of each major population group, including Māori and Pacifika minorities. This facilitates continuous assessments of gaps and a tailored and targeted provision of investments and social services. The five-year development plan should therefore not be seen as a stand‑alone policy, but rather in conjunction with the general policies in each of the areas concerned (e.g. education, job mobility). The Plan complements these individual policy areas with a holistic vision to achieve the overarching goal of better economic integration of Arab-Israelis.

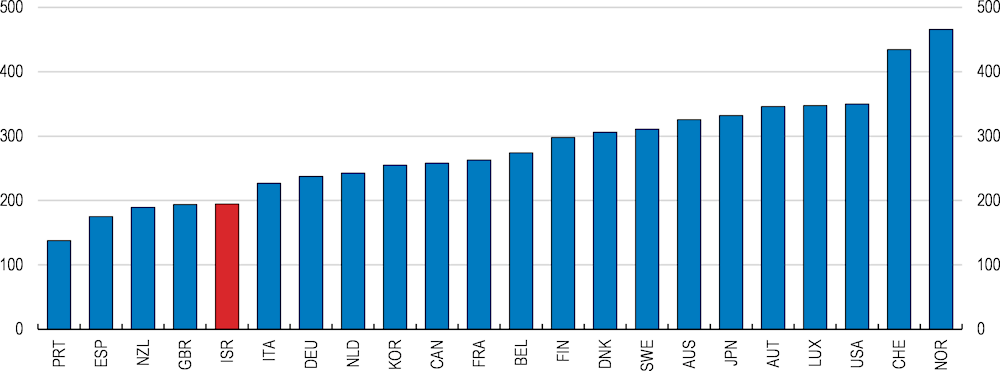

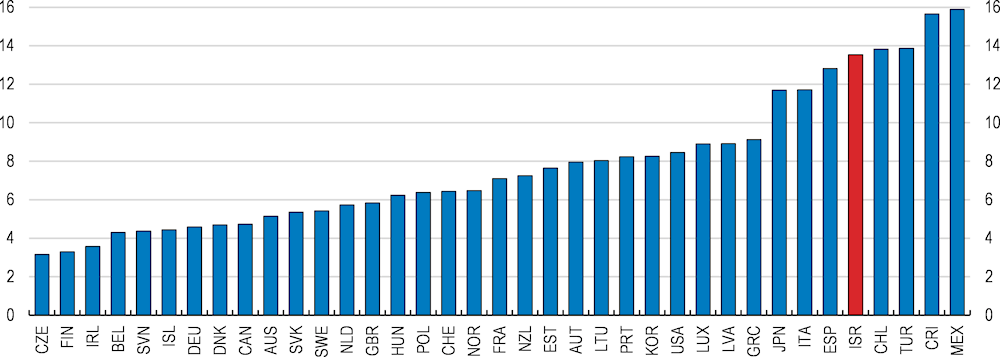

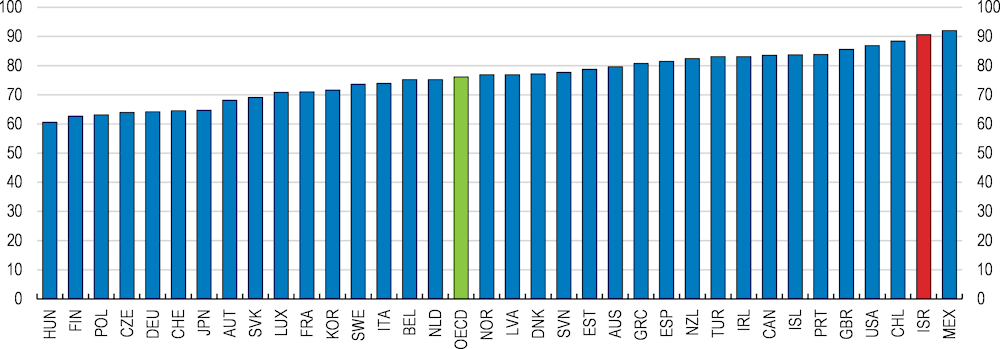

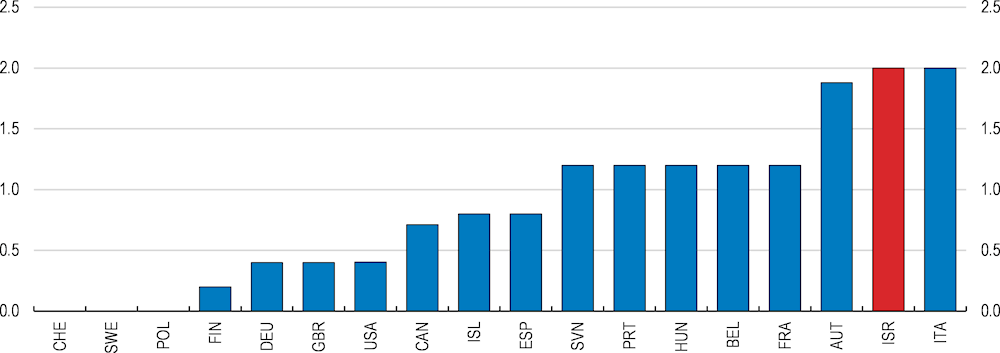

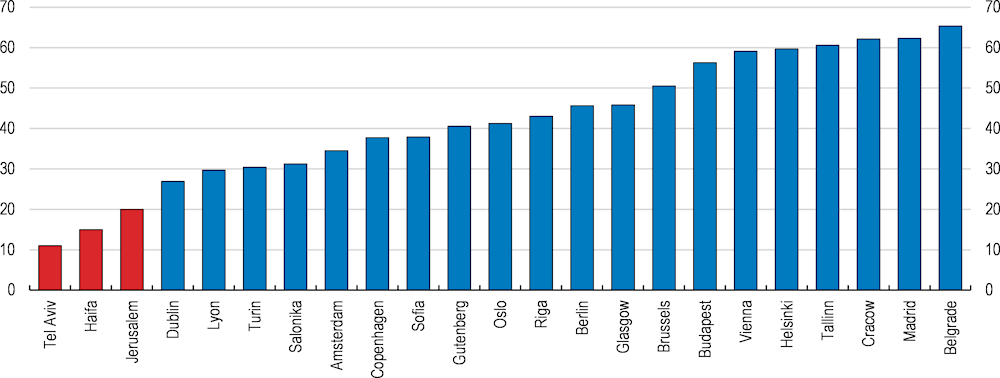

Israel has one of the highest gender pay gaps in the OECD (Figure 2.7). The median wage for women in full-time work is about 23% less than for men. In contrast to most other OECD countries, the gender pay gap has not fallen in the last decade. Gaps in hourly wages and hours worked explain most of gender inequality within the majority population group of non-Haredi Jews (Figure 2.6, Panel B). At the same time, this group has a very high female labour force participation rate. As a result, the gender income gap in Israel (which, in addition to pay, accounts for differences in participation) is similar to that observed in other OECD countries (Ciminelli, Schwellnus and Stadler, 2021[9]). By contrast, gaps in part-time status and employment are the main drivers of gender inequality among Arab-Israelis and Haredim. The increase in female labour force participation rate among Jewish women was a main driving force in the rise of the overall labour force participation rate (MoF, 2016[10]). The largest factor behind the wage gap that remains after controlling for working time differences is the occupation and industry where women work in (Fuchs, 2016[11]). This suggests that policies which improve the representation of women in high-paying jobs and firms can go a long way in narrowing the gender wage gap, especially for Jewish women. By contrast, increasing the employment rate is still an important priority for Arab women.

Figure 2.7. The gender pay gap is one of the highest in the OECD

Median wages, full time employees, %

Note: The gender pay gap is defined as the difference between median wages of men and women relative to the median wages of men. Data refer to full-time employees (aged 15 years and over), defined as those individuals with usual weekly working hours equal to or greater than 30 hours per week.

Source: OECD Gender Wage Gap database.

Box 2.1. The economic plan to reduce social gaps in the Arab society by 2026

The five-year economic plan (established in Government Resolution 550) takes a systemic and holistic approach to reduce the multiple gaps between Arab-Israelis and the general population that are documented in this chapter, with investments into education, infrastructure, digitalisation and other areas. The plan simultaneously addresses multiple deprivations and barriers to economic integration of Arab-Israelis.

This follows on a similar 5-year plan created in 2015 (Government Resolution 922), and builds on the lessons learned from it. Implementation of the previous plan was weak, and only about half of the allocated budget was spent. Factors which hindered the execution were the lack of specific targets and limited coordination between the authority in charge of the plan and the relevant ministries. The authority further suffered from limited management capacity, including for monitoring the plan’s implementation (Bank of Israel, 2022[12]; The Knesset, 2021[13]). In contrast, the new plan has specific targets and mechanisms to monitor implementation against targets.

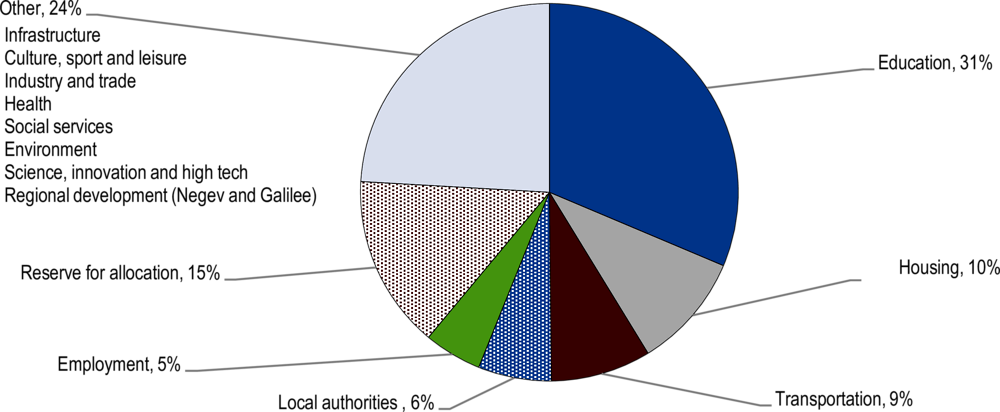

The budget of the plan is approximately 30 billion NIS (2% of GDP), of which 15.4 billion NIS are new financial commitments. In contrast to the previous plan, which mainly focussed on infrastructure development, the new programme places a greater emphasis on social aspects and on human capital (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8. Distribution of budget allocation of the Economic Plan for the Arab Society

The plan includes the following priority areas:

Education: close gaps in education by improving the quality of teaching in Arab schools by strengthening local school management and invest into school infrastructure. Targets exist for boosting Hebrew language literacy, improving Arab students' performance in the 2025 PISA, and dropout reduction.

Housing: construct 9,000 new publicly owned housing units by 2026, plan 85,000 new privately and publicly owned housing units, renew electricity, lighting, and sewage infrastructure in old Arab towns.

Transportation: upgrade infrastructure and public transport in Arab towns, and improve road safety.

Employment: increase employment rate and human capital quality with an emphasis on the 18-35 age group by establishing local employment centres, increasing access to VET and technical colleges, and providing incentives to employers to integrate Arab employees. The high-tech sector special programme subsidises STEM students and interns in high-tech firms, and the “gap year” programme enhances skills of young adults.

Digitalisation: increase digital literacy; translate digital governmental services into Arabic; connect 80% of households in Arab localities to high-speed broadband.

Local authorities: reduce the gap in per capita expenditure, increase Arab municipalities’ own revenues, improve management capabilities and promote regional cooperation.

The adoption of ambitious new employment targets for 2030 sends a strong signal that the authorities prioritise reforms to meet all these challenges. The targets are based on recommendations by an independent committee including the government and social partners, and led by academic experts. The targets foresee maintaining the employment rate for non-Haredi Jews at their current levels, which are high by international comparison. At the same time, the targets call for an ambitious increase in employment rates for the groups with currently low labour force participation, notably Arab-Israeli women and Haredi men, as well as workers with disabilities across all population groups. Overall, if all of the targets were achieved, this would bring the employment rate in 2030 to just above 80%, which would be in the highest quintile of the OECD (The Employment 2030 Committee, 2020[14]).

The inclusion of wage targets in addition to employment puts a welcome emphasis on the quality and productivity of jobs and not only their quantity. Only closing employment gaps will not be sufficient to maintain or further expand the productive potential of the Israeli workforce. Improving worker productivity and promoting access to high-paying jobs would lead to better wages for underrepresented groups, strengthening incentives for market participation and for acquiring higher education in well-remunerated fields, including through the encouragement provided by role models from their own community. Since the high incidence of part-time work among certain groups such as Haredim affects negatively the productivity per worker, the government should carefully monitor this dimension of labour market gaps in addition to the hourly wage.

The government needs to ensure effective actions are taken to meet the targets: raising labour market participation by setting appropriate work incentives and improving support for working parents; increasing the job productivity of underrepresented groups through better skills; and improving mobility for all population groups into well-performing firms and jobs, including the shortage-facing high-tech sector.

Raising labour market participation

Providing work incentives through the tax and benefits system

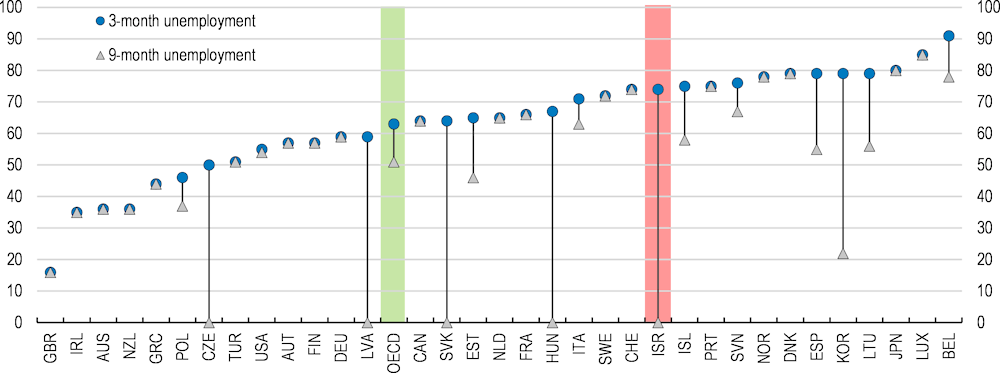

The Israeli tax and benefit system sets strong work incentives. Israel taxes personal income on an individual basis, with a fairly progressive tax rate schedule. The personal income tax has a basic tax allowance set at around the full-time minimum wage. Tax liabilities are further reduced through tax credits that are targeted at families with young children and single parents. As a result, most workers with earnings below the median wage have in practice no income tax liabilities. Personal and child tax credits are more generous for women, incentivising female labour force participation. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), discussed below, further adds to the progressivity of the tax schedule. Unemployment insurance offers replacement rates in line with other OECD countries for those who lose their jobs, but benefit duration is relatively short, ranging from 50 to 175 days, depending on employment history and household composition (Figure 2.9). Social assistance and housing benefits can be received for longer, especially by unemployed persons with children, but the resulting net replacement rates are still lower than in most other OECD countries. This specific design contributes to Israel’s low overall unemployment rate – 3.8% before the pandemic, compared to an OECD average 5.4% – and one of the lowest shares of long-term unemployed among OECD countries (Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.9. The unemployment insurance system provides strong work incentives

Net replacement rate in unemployment, %, 2022 or latest available year

Note: Net replacement rates in unemployment measure the proportion of income that is maintained after T months of unemployment. Data refer to a single person without children, with previous in-work earning at 67% of the average wage, excluding social assistance and housing benefits. 2021 data for Israel.

Source: OECD tax benefit models and policy, http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

Figure 2.10. The incidence of long-term unemployment is low

Unemployed for more than 1 year, as % of total unemployment, 2021

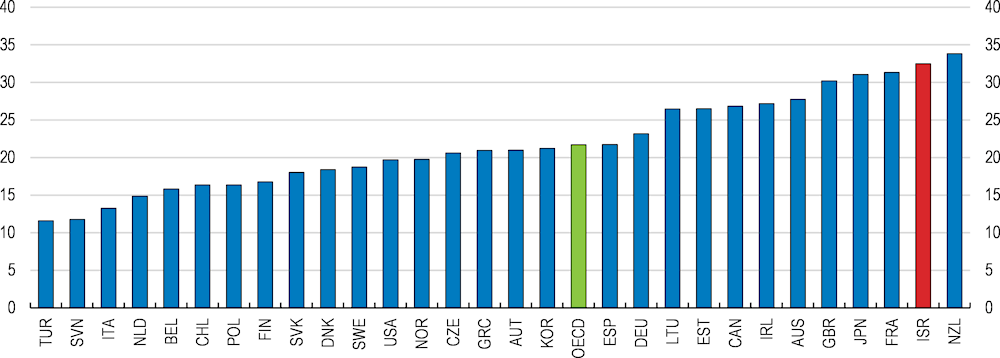

However, the rapid withdrawal of unemployment benefits potentially contributes to skills mismatch; among other factors such as limited Hebrew proficiency among immigrants and Arab-Israelis (Bleikh, 2020[15]). The share of over-qualified workers is one of the highest in the OECD (Figure 2.11). The short duration of unemployment benefits gives strong incentives for workers who become unemployed to find a new job quickly. Since finding a good match for their skills and experience takes time, many jobseekers will therefore settle for a position that does not fully utilise their potential, resulting in mismatch. Mismatched workers are paid less than suitably matched workers with similar qualifications, and this wage penalty is particularly high in Israel (OECD, 2016[16]). Evidence from other OECD countries suggest that mismatch especially affects labour market outcomes of disadvantaged workers, who are less likely to be able to support their job search from own funds or other sources (Farooq, Kugler and Muratori, 2020[17]). In this respect, the Israel Employment Services has many recurring clients that cycle between short-term jobs and unemployment. With a benefits system oriented towards strong work incentives, active labour market policies have an important role to play in improving job quality and the integration of underrepresented groups into the labour market, as recognised in the OECD Jobs Strategy (OECD, 2018[18]). The government should review the design of unemployment insurance with a view to strike the right balance between work incentives and supporting good job matches and employment quality.

Figure 2.11. Skills mismatch is high

Share of over-qualified workers, %

Note: Based on Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data (2012, 2015). Data for BEL refers to Flanders, while data for GBR refers to England.

A worker is classified as over-qualified when the difference between his or her qualification level and the qualification level required in his or her job is positive. The Survey of Adult Skills asks workers to report the qualification they consider necessary for their job today.

Source: OECD (2016), “Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills”, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.

An important element to improving the quality of job placements consists of providing jobseekers with the right training and incentivising them to take it up. A welcome recent reform abolishes the financial penalty (reduction in unemployment benefits) for jobseekers in professional training programmes, which strongly reduced the incentives for re-skilling and upskilling. As discussed further below, incentives for undergoing re-training can further be strengthened, for example by introducing time accounts or individual learning accounts (OECD, 2017[19]). This is especially important given the concurrent reform in financing of VET providers which should increase the quality of training. Adult learning should continuously offer opportunities to the large share of workers lacking basic skills, including language skills in Hebrew and English. The COVID-19 crisis underlines the importance of training in general digital skills (OECD, 2021[20]), which are comparatively low among the Israeli workforce, as pointed out in previous Surveys (OECD, 2018[4]; OECD, 2020[3]). Finally, the implementation of adult training is fragmented across the Ministry of Economy, the Israel Employment Service, the Authority for the Economic Development of the Arab Sector within the Ministry of Social Equality, and local training institutes. This calls for improved coordination and mutual recognition of training, even as competition among training providers and variation in training programmes offered to workers should be encouraged.

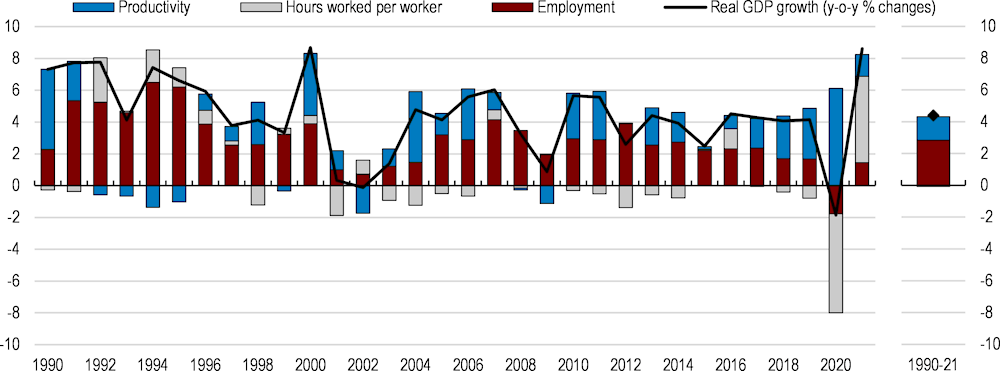

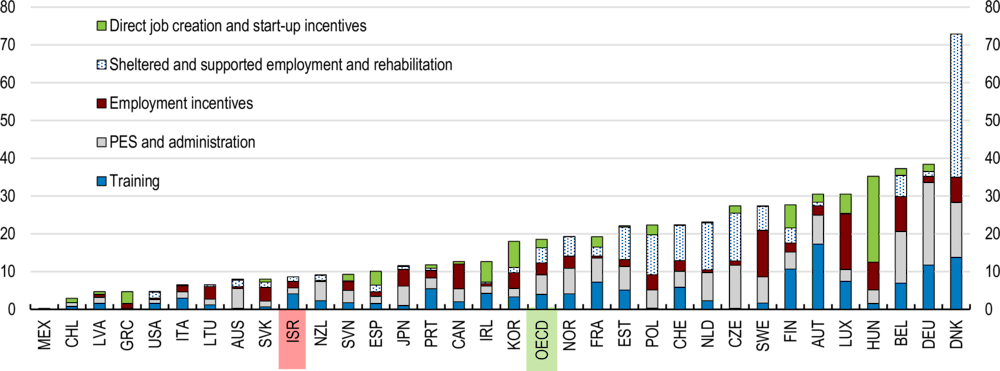

There is room to expand other components of active labour market policies (ALMP) in order to help workers find high quality jobs (Figure 2.12). For example, well-targeted hiring subsidies for specific groups or jobs have been shown to be effective measures for boosting job growth of disadvantaged groups (Cahuc, Carcillo and Le Barbanchon, 2018[21]) and have been recently introduced or strengthened in a number of OECD countries, such as Australia, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom. In Canada, for example, temporary wage subsidies are available for certain new hires, especially minorities, young workers, workers with disabilities, or in specific sectors such as STEM. In 2021, the Israeli government introduced a pilot hiring subsidies scheme for specific populations, including Arab-Israelis, Haredim, and workers with disabilities (Labour Division, 2021[22]). This programme should be closely monitored and its effects evaluated. The implementation and evaluation of job placement services could be even more enhanced by greater integration of the Israel Employment Service’s administrative data on jobseekers with other labour market data, as part of a single labour market data hub (see below). Systematic impact evaluation of new and existing programmes would help identify the programmes that are most effective and that should be expanded.

Figure 2.12. ALMP spending is low

ALMP spending per unemployed, as % of GDP per capita, 2019

Note: ALMP refers to active labour market programmes. Data for AUS, NLZ and USA refer to the 2018/19 fiscal year.

Source: OECD Labour Market Programmes database.

Being in work is not sufficient for staying out of poverty for a comparatively high share of workers (Figure 2.13), especially for those in single earner and large households. To support the incomes of low earners, Israel operates an Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) scheme, first introduced in 2007. This targeted support system contributes to increasing employment and reducing poverty among vulnerable populations, with strong individual incentives for participation due to high ceilings on family income (Brender and Strawczynski, 2020[23]) at a low budgetary cost (IMF, 2018[24]). However, the current level of EITC is not sufficient to lift the typical Arab-Israeli or Haredim household above the poverty line (OECD, 2020[3]). In 2018, an EITC reform (the “Net Family Program”) expanded the wage threshold after which the EITC bonus starts to taper off by 50% for fathers and 30% for families where both parents work. These changes restored gender balance and strengthened work incentives for second earners. However, this reform was temporary and only applied to a single tax year. Instead, other temporary EITC supplements were introduced in 2020 and 2022 to support households in light of COVID-19 and the high cost of living, but without the added work incentives of the 2018 reforms. The government should permanently re‑introduce the changes of the 2018 reform, as recommended in the 2020 Survey (OECD, 2020[3]). Specifically, the second-earner bonus should be re-introduced, and the withdrawal threshold of fathers should be aligned with that of mothers. This would provide low-income households both with a stable in‑work benefit and a longer-term work incentive, which would encourage investments into job search and skills.

In addition, the government should improve the EITC take-up rate of around 70%, which is mainly driven by very low take-up among Arab-Israelis (State Comptroller of Israel, 2020[25]). This is lower than e.g. EITC take-up in the United States, which is around 80% (Goldin et al., 2022[26]). In the first years after the introduction, the Israeli government sent out reminder letters to workers who were likely eligible for EITC and the evidence suggests they resulted in an increased uptake (Strawczynski and Myronichev, 2014[27]). The government should simplify procedures for obtaining EITC, for example by moving towards auto-enrolling workers who are eligible based on their tax records. The Tax Authority, relying on salary information provided by employers, already processes taxes without the need for workers to file a tax return, and should therefore already have all necessary information for checking EITC eligibility and processing payments (Lior, 2022[28]). Reminder letters can be re-introduced as a temporary solution until the administrative systems for auto-enrolment have been completed. As part of the same reform, monthly or quarterly advance payments based on preliminary eligibility assessments should be made. Currently the EITC is paid on an annual basis several months after the end of the tax year, which reduces intended work incentives and effects on poverty reduction.

Figure 2.13. The share of working poor is high

Share of workers in poverty, %, 2020 or latest available year

Note: Workers with income below the poverty line after taxes and transfers, living in households with a working-age head and at least one worker. 2019 for Israel, 2021 for CRI and USA.

Source: OECD Income Distribution database.

Negative work incentives limit the employment of Haredi men. First, full-time yeshiva students receive a monthly government stipend. Second, a day-care subsidy for low-income families requires mothers but not fathers to be employed, an exemption which largely benefits Haredi fathers in yeshivas. Third, Haredi men under the exemption age (currently 24 years) are in principle conscripted into the army, yet they can secure repeated deferrals as long as they are engaged in full-time religious study (but not in other education or employment). This creates incentives for remaining out of market-relevant education or employment for a long time (i.e. until the exemption age), which has long-term consequences through scaring effects from reduced human capital accumulation and missing labour market experience. In addition, the withdrawal of stipends and additional community financial support implies very high marginal tax rates for young Haredi men if they decide to become employed (Batz and Krill, 2019[29]).

Evaluations of temporary reforms in 2014 that lowered stipends, restricted the day care subsidy eligibility (Batz and Krill, 2019[29]) and lowered the military exemption age from 24 to 22 years (Zofnik and Zussman, 2021[30]) suggest that, while not quantitatively large, the labour supply effects of these reforms were positive and lasting. Moreover, the Israeli High Court previously found the student stipend and the military exemption rules to be discriminatory, since they do not apply to students in other educational institutions such as universities. Government stipends for full-time religious study should be reduced (and brought closer to living expenses support for other types of post-secondary education) and the military draft exemption age should be lowered in order to attract more Haredi men into labour market relevant education and employment at early ages. In addition, day care subsidies should require both parents to be employed. Since the current eligibility criteria already condition the subsidy on the mother being employed, this should not have significant detrimental consequences on labour force participation of women; nevertheless the government should carefully monitor a reform for any such effects.

Israel introduced a successful furlough scheme during the COVID-19 crisis. The scheme provided income support to workers with jobs that were temporarily made unviable by pandemic restrictions, via the unemployment insurance (UI) system. As in the United States, for example, this allowed temporarily laid‑off workers quick access to income support through an established administrative infrastructure, with the crucial difference that in Israel the contractual work relationship was not severed (OECD, 2020[31]). As a result, many workers quickly returned to work when pandemic restrictions eased (see Figure 2.2). At the same time, the scheme seems to not have prevented efficient reallocation, as there was no noticeable decrease in job mobility in the recovery from the pandemic compared to its level in 2019 (Israel Democracy Institute, 2021[32]; Betz and Geva, 2022[33]). The scheme was discontinued in June 2021.

The introduction of a permanent job retention scheme could provide the basis for providing and scaling up fast and predictable support to workers in future crises without the need for recurrent legislation. Such a scheme should be better targeted to the actual needs for temporary job retention support. Two policy options for better targeting are allowing for flexibility in choosing the hours not worked, and introducing employer co-financing. First, many job retention schemes offer the possibility of a partial adjustment of hours in addition to full furloughs (OECD, 2021[20]), such as the Kurzarbeit scheme in Germany and chômage partiel in France. This allows better targeting of support to the actual shortfall in hours, resulting in potential fiscal savings relative to subsidising only complete furloughs (Effenberger, Koelle and Barker, 2020[34]). Such partial hours adjustment could still take place in the existing institutional set-up, with payments channelled through UI, as the examples of partial lay-offs in Norway and Finland show. However, such a more granular scheme comes with greater demands on monitoring of the actual time worked, on which administrative information is currently limited. Second, requiring a small participation to the costs of job retention support better incentivises firms to select into the scheme in case of temporary but not permanent shocks, preventing workers from becoming trapped in non‑viable jobs. Many countries have now introduced co-financing requirements to their schemes (OECD, 2022[35]). In Israel, co-financing could take the form of a mandatory employer-paid top-up to the relatively low statutory replacement rate (53% at the average wage) or payment of social security contributions over hours not worked, which was left unfunded during the COVID-19 furlough scheme.

Labour force participation of older workers will become increasingly important for overall employment due to population ageing. A welcome recent retirement reform will raise women’s statutory retirement age to 65, closer to that of men (67). As recommend in Chapter 1, the retirement age gap between women and men should be fully closed, and the statutory retirement age thereafter linked to life expectancy. In addition, incentives for workers to continue participating in the labour market past the statutory retirement age could be strengthened, for example by lowering the 60% deduction rate of basic old-age pensions and by reviewing the design of the pension bonus awarded to workers who continue to work past statutory pension ages with a view to make it actuarily neutral. A recent reform which increases the threshold at which income earned by pensioners starts being deducted from their pension is a step in the right direction.

Improving women’s participation in all segments of the economy

In general, the individual system of income taxation creates no negative distortions for second earners, and higher personal and child tax credits favour women. However, recent international evidence points to childbirth as one of the main triggers of gender differences in employment and wages (Ciminelli, Schwellnus and Stadler, 2021[9]; Kleven et al., 2019[36]; OECD, 2021[37]). In Israel, the estimated long-run child earnings penalty – the earnings loss for women after the birth of their first child, relative to men – among non-Haredi Jewish women is 28% (Yakin, 2021[38]). While this is somewhat lower than in other OECD countries, overall childbirth can be still considered a major contributor to the high gender wage gap, given that maternity is much more prevalent and fertility higher than in other OECD countries. The government should therefore target policies specifically at closing the career penalty for mothers. Since the main constraints to full participation differ for women of different population groups, differentiated policies are needed: increasing childcare provision for the Arab population to ease Arab women’s labour force participation, and enabling more equal allocation of household tasks in dual-earner Jewish families in order to incentivise a more gender-equal choice of working hours and pursuit of high-paying jobs.

Lack of available and affordable early childcare hinders the labour force participation of Arab-Israeli women. Pre-school attendance is almost universal for children of all communities from age three, the age at which it becomes free and mandatory. However, only one third of children under the age of three of Arab mothers without an academic education attend preschool; and two thirds of children of Arab mothers with an academic education (Vaknin and Shavit, 2022[39]). International evidence suggests that provision of early childhood education and care reduces gender disparities (Olivetti and Petrongolo, 2017[40]). Previous reductions of childcare costs in Israel have been found to increase employment of mothers of young children (Shachar, 2012[41]; Shachar, 2022[42]). Despite higher budgetary allocations for construction of day-care centres in Arab municipalities in recent years, implementation lagged behind due to difficulties with zoning and land availability in Arab municipalities (OECD, 2020[3]) and a lack of coordination between infrastructure construction and the furnishing and staffing of day-care centres (Madhala et al., 2021[43]). The government should ensure the timely and effective implementation of currently planned expansions of childcare in Arab municipalities.

The lack of synchronisation of school and work holidays creates barriers for female labour market outcomes. Unusually among OECD countries, Israel operates a six-day school week, whereas the working week has only five days. With longer school vacations to compensate for the longer school week, schools are closed on many days that are usual working days (Bank of Israel, 2019[44]). This increases the childcare burden for parents of school-age children, who need to find alternative childcare arrangements, or provide such childcare themselves. This has important gender implications in the labour market because the burden of childcare typically falls on women. In order to provide childcare on school closure days, women might move into part-time work, jobs with flexible hours, or less demanding roles where watching children alongside work hours is more feasible. The government has started to address this problem by introducing summer schools and holiday schools, but this reduces the “vacation day gap” only by a small amount (Bank of Israel, 2019[44]). The government should therefore align the school week with the work week by moving to a five-day school week while keeping the overall number of instruction days fixed. In addition, the government should offer vacation schools on the remaining non-school days to enable a better balance. For example, in France, which has the lowest number of instruction days of all OECD countries (OECD, 2021[45]), municipalities provide “leisure clubs” (centres de loisirs) on most non-school days. These clubs are run by non-teaching staff and provide extra-curricular activities at subsidised costs that are differentiated by household income.

Earmarking a part of parental leave to fathers can enable a better balancing of careers and families across men and women. The gender wage gap in today’s advanced economies largely results from the underrepresentation of women in the highest-paying jobs (Goldin, 2014[46]). In Israel, for example, women are only one third as likely as men to be managers (Kasir and Yashiv, 2020[47]), and women are under-represented in high-paying sectors such as in high-tech. One reason for this “glass ceiling” is that women often select into occupations with lower and stable hours that match with day-care and school times, whereas more men choose to work in a higher-paid jobs that demand presence whenever required by business needs, resulting in long and unpredictable hours (Goldin, 2014[46]). The introduction of reserved parental leave for fathers helps some families to break this pattern of specialisation, as evidence from Nordic countries shows (Albrecht, Skogman Thoursie and Vorman, 2015[48]). Fathers who take paternity leave tend to take on more childcare responsibilities afterwards, reducing the gender gap in unpaid family labour; an effect demonstrated for example in the Canadian province of Québec (Patnaik, 2019[49]). A more equal gender distribution in parental leave as well as take-up of workplace flexibility by parents will make employers less reluctant to hire or promote women, thus reducing gender gaps in employment and wages. Most OECD countries have now in place some form of reserved paternity leave (OECD, 2021[50]). Israel is an exception. Fathers can claim any unused part of the mothers’ 15 weeks of paid maternity leave entitlement, but have no individual entitlement for themselves. The government should introduce paid parental leave reserved for fathers that add to current entitlements for mothers. To incentivize take-up, the authorities should follow best practices and ensure paternity leave is well-paid, linked to earnings (up to a ceiling), and allow for flexible scheduling between spouses according to individual personal and professional circumstances (OECD, 2016[51]; OECD, 2022[52]).

Ensuring gender equality in all segments of the economy is a cross-cutting theme and goes beyond issues related to maternity and paternity. Women are among the priority groups targeted by a comprehensive strategy to broaden the high-tech talent pool, given their current underrepresentation in the sector, as discussed below. An expansion of STEM places should also go hand in hand with actions to improve the representation of women in these subjects. Moreover, given that parents caring for young children typically have lower job mobility and tend to favour shorter commutes to workplaces closer to home and childcare centres (Caldwell and Danieli, 2022[53]), policy recommendations to increase job mobility – especially improving public transport – also have the potential to benefit women. Finally, as discussed above, the proposed changes in the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) would improve gender balance.

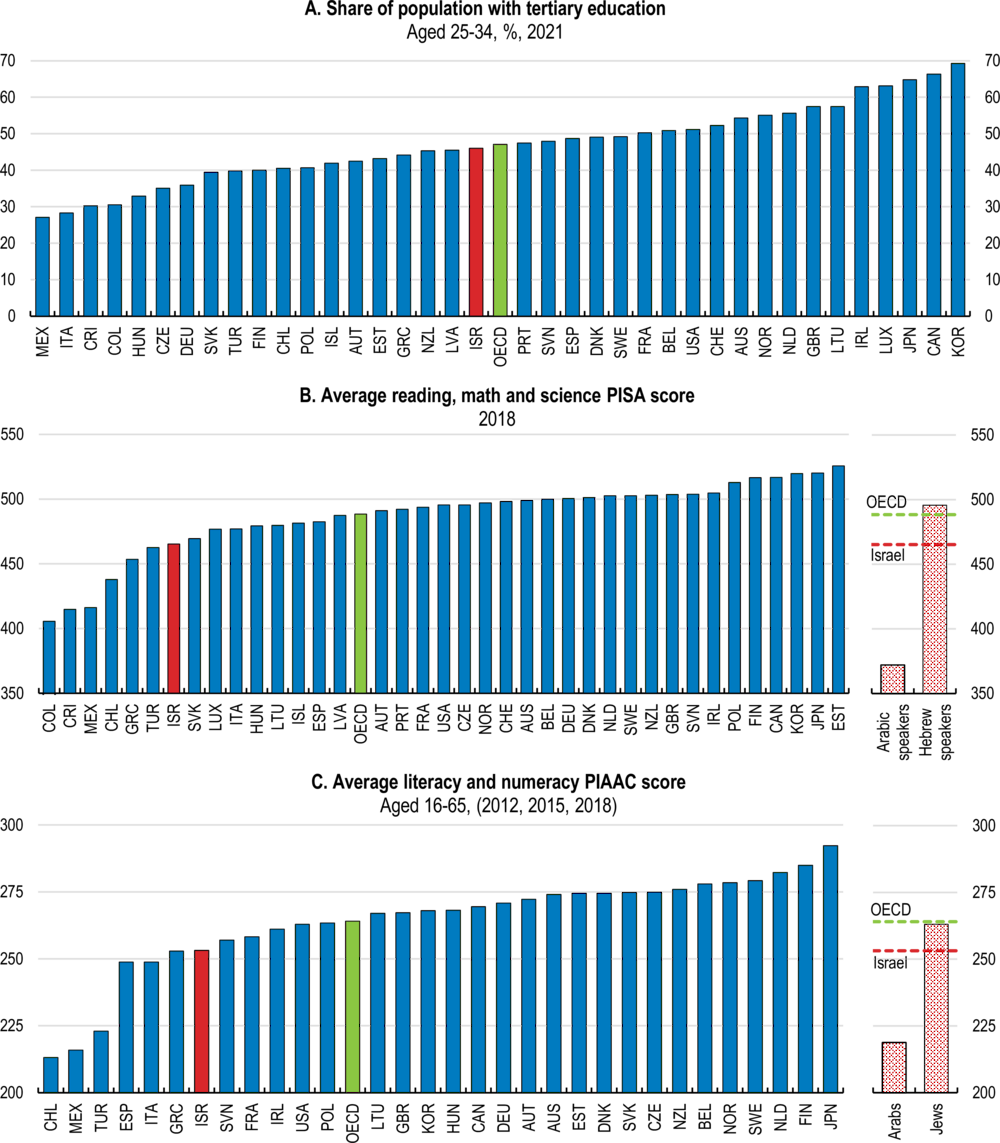

Improving skills for all

While the share of young Israelis with a tertiary education is about the OECD average, their level of skills lags behind other OECD countries (Figure 2.14). On average, on the PISA assessment, Israeli pupils perform significantly below most other OECD countries. After some progress between 2006 and 2015, PISA scores of Israeli pupils decreased again in 2018. Poor skills of school-age pupils carry over to low adult skills. Israel’s performance in the OECD assessment of adult skills PIAAC mirrors the results that the country obtains in PISA. These low average skills are largely the result of particularly low skills in certain population groups, especially Arab-Israelis. Israel has the highest dispersion of proficiency scores among all OECD countries (OECD, 2020[3]; OECD, 2018[4]). Given that Israel is also among the countries where skills differences have the largest consequences for wage differences, this translates into large wage inequality (OECD, 2018[4]). Improving the equity of the education system and closing skills gaps at all stages of the learning cycle is therefore a key pre-requisite for narrowing later gaps in the labour market. More flexible, institutionalised pathways between secondary schooling, VET, and tertiary studies would widen opportunities for those who left earlier education stages with insufficient skills.

Levelling differences in the schooling system

The schooling system is segmented along ethno-religious lines. It is divided into four main streams: the Arab stream (where the language of instruction is Arabic), the Haredi stream (with gender-segregated schools, and in particular for boys a focus on religious study), and two state Hebrew streams (one secular, one religious) that teach the national core curriculum in their schools. For historical, cultural, and political reasons, the Haredi community holds large autonomy over the curriculum and instruction in their education system. Education is free and mandatory for all children aged 3 to 18. The state provides 90% of all school funding, with the remainder coming from local governments, non-profit educational organisations, and private households (OECD, 2018[4]). Tertiary education is also largely funded by the state, though private colleges and one private research university exist.

Figure 2.14. Israel performs average in advanced educational credentials, but lags in skills

Note: In Panel A, 2020 data for CHL. In Panel B, Hebrew speakers should be interpreted as “non-Haredi Jews”.

Source: OECD Education Statistics database; OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en; and OECD (2019), Skills Matter: Additional Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1f029d8f-en.

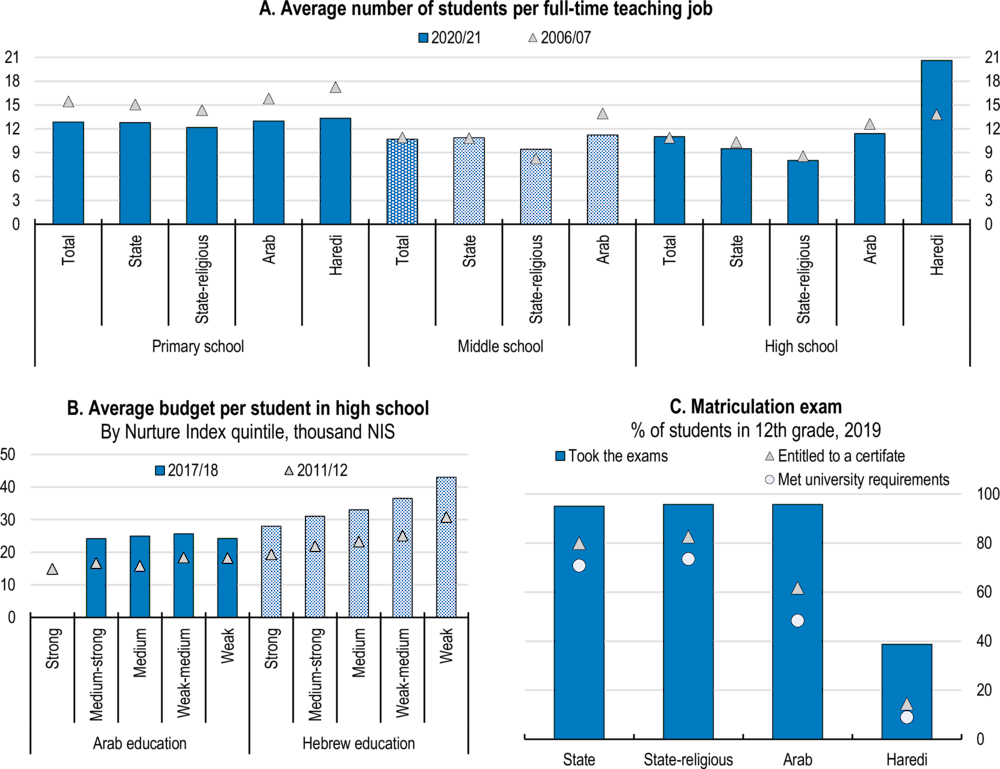

Resources in the education system are not systematically directed to where they are most needed. Despite some improvement in recent years, the Arab and Haredi education systems still count with less resources in terms of funding, teacher-pupil ratios, or teacher skill endowments than the two systems (state and state-religious) educating non-Haredi Jews (Figure 2.15). In 2016, the government started an education reform aiming to allocate more funding to schools in disadvantaged communities (OECD, 2018[4]; Blass and Shavit, 2017[54]). However, this has mostly benefitted disadvantaged Hebrew schools, whereas Arab schools continue to be under-funded with the largest gap among the more disadvantaged schools. The government should direct additional funding towards Arab schools with weak learning outcomes – which are the most underfunded type of schools (Figure 2.15, Panel B) – equalising their funding to schools with similar profiles (index of socio-economic background) in the Hebrew sector.

Figure 2.15. Large inequalities exist in education provision across groups

Note: In Panel A, data for Haredi are not available for the middle school category. In Panel B, data for Arab are not available for the first quintile (i.e. "strong") for 2017/18. The Nurture index of the Ministry of Education measures the socio-economic background of a school’s student population.

Source: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics; Nachum Blass (Taub Center for Social Policy Studies); and Israel Ministry of Education.

Schooling resources go beyond funding per pupil or class sizes. Better incentives are needed to attract qualified teachers in the schools with the highest needs. Similarly, it is increasingly difficult to attract graduates with lucrative job opportunities in the private sector, such as those specialised in maths and sciences, into the teaching profession. This will require better baseline salaries, especially for early-career teachers (OECD, 2018[4]). A recent wage agreement, which boosts salaries of starting teachers by up to 30% in nominal terms, will improve the competitiveness of the teaching profession, especially in high cost-of-living areas. Incentives could further include special provisions for priority subjects or regions, which already exist for some municipalities. For example, in Estonia new teachers are offered an allowance for three years if they locate in rural areas and in Korea, teachers in high-needs schools have better working conditions and receive credits for future promotions to administrative activities, as well as better choice over the next school in which to work (OECD, 2017[55]).

Strengthening schools also requires changes to the curriculum and the organisation of teaching. For the Arab stream, a long-standing issue is the lack of Hebrew language instruction. As discussed in past surveys (OECD, 2020[3]) (OECD, 2018[4]), described by Israeli researchers (de Malach, 2021[56]; Labour Division, 2019[57]), and voiced by professionals committed to diversity initiatives at universities and the high-tech industry, insufficient Hebrew proficiency limits the opportunities of many graduates of the Arab education system. The government should increase the provision of Hebrew language instruction in the Arab stream, and restructure the curriculum to put practical knowledge and application of the language at the centre. A useful tool to achieve this is to promote teacher exchanges between the Arab and Hebrew streams to facilitate teaching by native speakers, which could partly cover core subjects other than the languages itself. English language teaching should also be strengthened. In addition, outdated teaching standards in the Arab education system, with a very traditional pedagogy focussing largely on rote learning, provide insufficient preparation to pupils for the intellectual challenges of higher education and should be reviewed.

The main challenge of the Haredi education system is its lack of instruction in the core curriculum. Given the large degree of autonomy enjoyed by the stream, funding allocations with conditions attached is the main policy lever available to the government. In principle, funding for Haredi schools is already proportional to the share of core curriculum subjects taught (OECD, 2018[4]). However, limited oversight, lack of inspectors, and the absence of participation in standardised testing mean that there is very limited supervision. At the same time, there is considerable unmet demand among Haredi parents for core curriculum teaching in addition to religious subjects (Gal, 2015[58]). One step in the right direction was the establishment of a “state” Haredi stream – where schools teach the full core curriculum in addition to religious subjects and are under full supervision of the Ministry of Education while retaining cultural autonomy. However, since its first establishment in 2004, the model has not yet been formalised in legislation, creating legal uncertainty that prevents more schools from joining (Hazan-Perry and Katzir, 2018[59]). While enrolment in this stream has increased in recent years, pupils joined not only from Haredi schools but also from the state-religious stream, increasing the burden on the Ministry of Education’s budget without achieving the desired goals. The authorities should improve the general accountability of Haredi schools for the state funding they receive for teaching core subjects. This would include strengthening administrative capacities of the Haredi branch in the Ministry of Education and improving the effectiveness of inspections by investing into evaluation of learning gains in core subjects.

Broadening participation in tertiary education

Access to tertiary education has improved significantly in recent years, but remains low for certain groups. Public and private colleges account for the greatest share of the rapid expansion of higher education (Hazan and Tsur, 2021[60]), and 12% of adults hold tertiary credentials below a bachelor’s degree, for example professional colleges (OECD, 2021[45]). The share of Arab-Israelis in tertiary enrolment doubled to 20% within only a decade, but the group is still underrepresented in higher education (Amaria and Krill, 2019[61]). Women make up more than 60% of all Arab university students. While Arabs are still more likely to choose professional and teacher training colleges over universities, the gaps are shrinking.

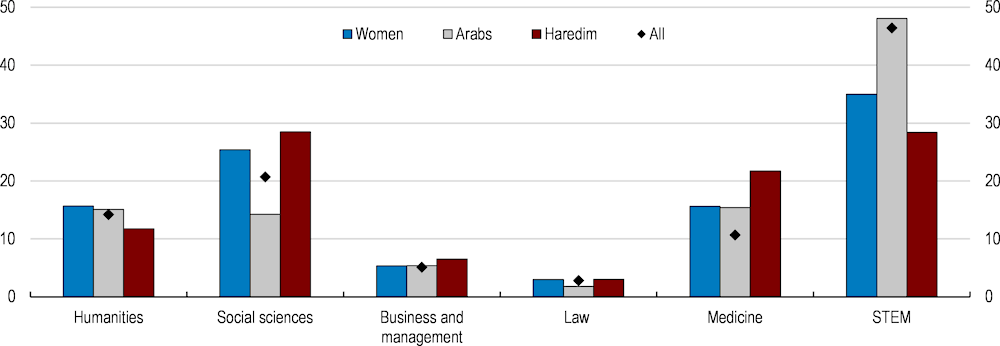

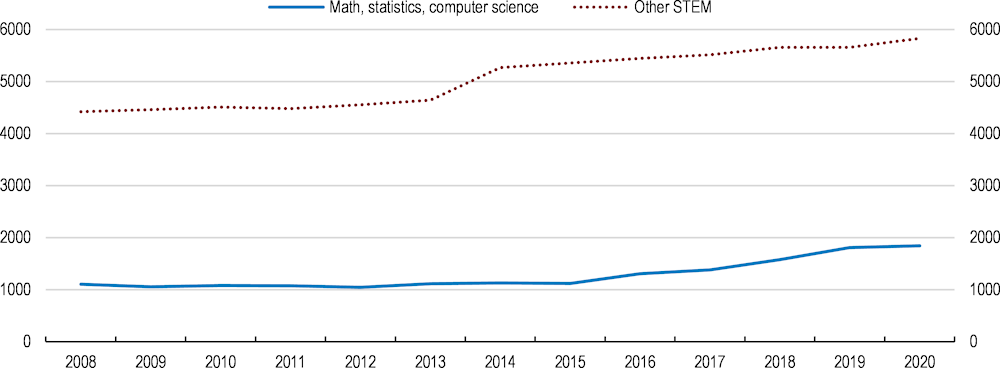

Many university students major in STEM subjects such as mathematics, statistics, computer science or engineering (Figure 2.16). Arab-Israeli students are now relatively well-represented in professions with high earnings potential such as STEM and business and management, as well as in medical studies, although within those fields they still are under-represented in the subfields with the highest earnings potentials. For example, their share in the medical field is skewed towards paramedical courses rather than training to be a doctor (for which many Arab-Israeli students go abroad). Women are underrepresented in STEM, although their share has significantly increased over the last decade and the female representation in STEM subjects in Israel is higher than in many other OECD countries (Mostafa, 2019[62]). As in other countries, female representation in STEM is partly a reflection of gender stereotyping and subject specialisation already in upper secondary school. In the specific case of Israel, women are also less exposed to technological roles during their military service compared to men (Israel Innovation Authority, 2022[63]). Promoting female role models at all stages of the education system, building girls’ confidence, and training teachers to recognise and address biases are policies seen as promising to improve female representation in STEM (OECD, 2017[64]).

The vast under-representation of graduates of the Haredi school system in higher education – only 2% of all students – is to some degree a reflection of insufficient preparation by the school system. Only around 10% of Haredi pupils (and only 3% of boys) take and pass the matriculation exams that are a general requirement for college admission. Many members of the community further avoid co-educational campuses for cultural reasons. There has been some success with offering post-secondary courses – such as computer science at the “practical engineering” level, a two-year vocational degree – in seminaries for Haredi women. These are segregated by gender, are organised as a community enclave, and admission requirements are tailored to the secondary credentials issued by Haredi girls schools. This education has allowed for a successful labour market integration of Haredi women into skilled professions (Labour Division, 2019[57]). Overall, expanding higher education access for the Haredim rests on a combination of three policies that are discussed below and above: (i) improving pathways between post-secondary VET degrees and tertiary studies, which would open up opportunities for those who acquire skills at a later learning stage, (ii) improving education quality in the Haredi school system to prepare pupils better for higher education, and (iii) incentivising Haredi families to participate in labour market relevant education and training, especially core subjects in secondary school, and improving their performance in matriculation exams.

Figure 2.16. Many university students choose STEM subjects, but some groups still lag behind

Share of fields of study among population groups, %, first-degree first-year students, academic year 2019-20

Note: STEM stands for Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. It comprises the sum of categories “Natural science and mathematics”, “Agriculture” and “Engineering and architecture” as reported by the Central Bureau of Statistics.

Source: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics.

Average wage gaps between university and college graduates are significant. The fact that colleges tend to be less selective than traditional universities, as well as differences in the quality of education they provide, contribute to a lower valuation of their degrees on the market. Moreover, university students benefit from a more challenging learning environment with high-ability peers, as well as from access to better alumni networks (Krill, Hakt and Fischer, 2018[65]). Graduates of colleges earn 10-20% less than university graduates on average (Achdut et al., 2018[66]), and they struggle more to find adequate jobs for their formal level of qualification (Lipiner, Rosenfeld and Zussman, 2019[67]). To better inform post-secondary education choices, the government has recently launched the online tool Avodata with salary and employment information of graduates by field, based on statistical analysis of labour force data. It also provides information on the wage returns to careers by educational institution, enabling prospective students to make better informed enrolment choices. This is in line with recommendations in previous Surveys (OECD, 2018[4]) to introduce mandatory tracking of graduate outcomes by universities.

A high share of young Arab-Israeli men are not in education, employment or training (Figure 2.17). This share had been progressively increasing before 2020 – in contrast to young Jewish men, for whom it had been declining. A major explanation for the persistent difference in NEET rates is the fact that about 35-40% of non-Haredi Jews of similar age are in mandatory military service in the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) and therefore are counted as working. Moreover, due to their exemption from military service, Arab-Israelis need to make career choices including about post-secondary studies around age 18, whereas their Jewish classmates tend to arrive at this juncture in their mid-20s. The structured environment of the IDF also offers opportunities to make up for missed education in teenage years, including re-taking the Bagrut exams. Other explanations are weaker educational outcomes among Arab-Israelis (see Figure 2.15) which render many of them ineligible for university studies, and lack of good employment or education opportunities in Arab cities. NEET rates are particularly high for young Arab men from weak socio-economic backgrounds (Haddad Haj-Yahya and Shaviv, 2021[68]), reflecting the low degree of inter-generational mobility among Arab-Israelis (Batz and Krill, 2019[29]; Batz and Geva, 2022[69]). This has individual as well as societal consequences, as lack of opportunities and perspectives make young Arab men more vulnerable to recruitment by organised crime (Haddad Haj-Yahya and Shaviv, 2021[68]).

Figure 2.17. A high share of young Arab men are not in education, employment or training (NEET)

Share of NEET in population, men aged 18-24, %

A long-standing proposal in Israel is a “gap year” around age 18 to provide Arab-Israelis with opportunities for skills and personal development that military service usually provides to Jewish Israelis, including more maturity and independence when entering post-secondary education. Such a programme is currently being implemented at large scale. The government should carefully monitor and evaluate this policy, and whether it serves its purpose of improving integration of young Arab-Israelis into post-secondary and tertiary education and subsequently the labour market. There is a risk that the current programme, with a focus on crime prevention and at-risk youth, may not be perceived as an attractive option by many young Arab-Israelis, and perhaps may even give a negative signal to future employers.

There is also a risk that a gap year simply pushes the problem of NEET youth by one year into the future, if there are no incentives for programme providers to achieve good post-programme outcomes. The development of skills and exploration of interests during a gap year should be complemented with guidance on further education and career choice, for example in cooperation with existing local employment centres in Arab municipalities. The goal should be that each graduate from the “gap year” has a clearer plan of their future career path, be it admission to university, a place in a VET programme, or enrolment in a programme to re-take the Bagrut exam. The government should consider conditioning the funding of “gap year” providers on successful placements in follow-up programmes.

In addition to general programmes as the “gap year”, existing and planned sectoral programmes that provide orientation to young people about professions and careers could help bridge the gap between school and work or professional training. According to practitioners and sector experts, in order to be effective such programmes should include targeted support to address the specific barriers that young Arab-Israelis face, such as language barriers and lack of opportunities in their place of upbringing, and offer personalised professional and socio-emotional support. Examples include initiatives at universities in the form of foundation year programmes to improve access of underrepresented groups who receive insufficient preparation in secondary education, or in the high-tech sector to organise coding bootcamps to attract more talent from underrepresented groups to the sector.

Embedding high-quality vocational and educational training in a national qualifications framework

Adult learning plays an especially important role in context of the fragmentated schooling system and the skill gaps it produces. In all OECD countries, digitalisation and automation pose risks to existing jobs especially of those with qualifications below the tertiary level (OECD, 2019[70]). Adult learning systems that promote life-long learning help re-skill and upskill those workers. In Israel, adult learning can further build job-relevant skills that individuals fail to acquire at earlier educational stages. A major component of adult learning systems is vocational education and training (VET), which equips school leavers who do not continue to higher education with workplace-relevant skills. The VET system in Israel consists of four different pathways, and military service plays a major role in shaping these pathways as well as the incentives of technical students and employers (Box 2.2)

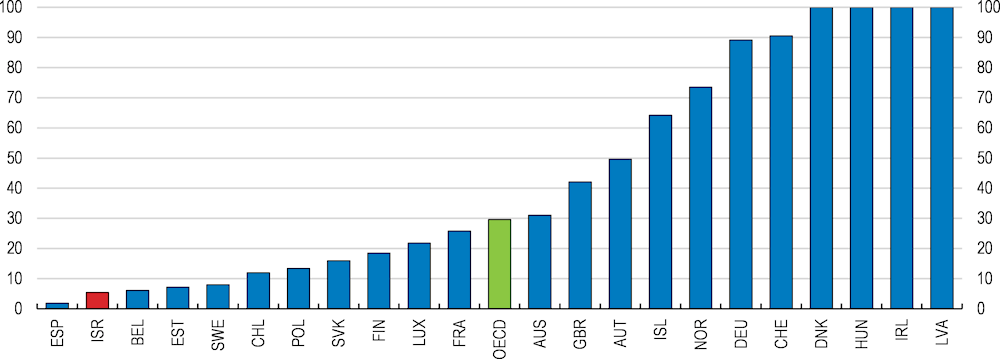

Few young Israelis pursue VET as terminal degrees (Figure 2.18). More than nine out of ten young Israelis aspire to professional occupations that typically require university or other tertiary degrees (Figure 2.19). This may partly be influenced by the importance of education in Jewish history (Botticini and Eckstein, 2015[71]) and the high returns to professional qualifications, e.g. university degrees (Achdut et al., 2018[66]). But it likely also reflects the low status that is given to VET tracks, which are often seen as options of last resort for weak students, high-school drop-outs, or those that did not pass the Bagrut exam (Kuczera, Bastianić and Field, 2018[72]). The latter is the gateway to higher education, and while about 95% of all non-Haredi secondary pupils take the exams, only 80% receive a matriculation certificate and 70% do so with results sufficient for university admission (see Figure 2.15, Panel C). While some reputable and successful programmes with high labour market returns exist in certain technical fields, notably a two-year practical engineering degree (MAHAT), a significant part of the VET system seems to offer low returns and is not perceived as attractive by many young adults. Increasing the attractiveness of VET would boost skills at the lower end for a relatively lower budgetary cost than tertiary education.

The authorities are aware of the need to reform VET. Main reform proposals, including by the National Economic Council at the Prime Minister’s Office (National Economic Council, 2016[73]), the OECD (Kuczera, Bastianić and Field, 2018[72]; Musset, Kuczera and Field, 2014[74]), and the Committee for Employment Advancement towards 2030 (The Employment 2030 Committee, 2020[14]), emphasise the need to: (i) create a National Qualifications Framework; (ii) modularise educational degrees to create flexible pathways for mobility between upper-secondary schooling, post-secondary VET, and tertiary degrees; and (iii) improve the quality and labour market relevance of VET, including through integrated work-based training.

Box 2.2. The VET System in Israel

The VET system consists of four pillars:

Upper-secondary “technological tracks” under supervision of the Ministry of Education, which is a form of compulsory schooling for under 18-year-olds, leading to a Bagrut exam.

An extension of upper-secondary VET (“13th and 14th year”), taught in vocational secondary schools under supervision of the Ministry of Education, which requires previous completion of upper-secondary technological tracks with a full Bagrut exam.

Post-secondary VET provided by technological colleges, some of which are members of large school networks. These provide one or two year courses that lead to an occupational certification, under the purview of the Labour Branch in the Ministry of Economy.

Short adult learning VET courses, offered as on-the-job training or for unemployed workers. These are financed by the Labour Branch and subsidiary agencies (such as the Israel Employment Service), sometimes as part of active labour market programmes, sometimes offered at a local level, e.g. in local employment centres.

Military service plays an additional role in the Israeli VET landscape. Serving in the IDF is mandatory for all non-Haredi Jewish Israelis, and consists of three years of service for young men and two years for young women. Most Israelis complete military service between their secondary education and further studies. Given the length of service, many young adults are trained in a technical profession by the army, and qualifications are typically recognised in civilian life. The “13th and 14th year” pathway also takes place in close coordination with the IDF. Students generally need a deferral of military service in order to enrol into the programme, they often receive a scholarship from the IDF, and complete a longer military service where they exercise the technical professions they were trained in. The army also offers school drop-outs or those who failed to pass the Bagrut the opportunity to complete their secondary schooling. Finally, military experience also plays a key role in future study and career choice.

Work-based learning should be strengthened to improve the quality and relevance of VET. Currently work-based learning is very low (Figure 2.20), reflecting limited employer involvement in accredited VET training (as opposed to unaccredited short training programmes responding to specific employer training needs). Employers have limited incentives to invest into general rather than specific training, due to the externality involved with portable skills. This is a problem especially in Israel given the long military service, which means that firms cannot benefit from work-based VET as a tool to recruit secondary graduates, in the way apprenticeships work in other countries. The flipside, however, is that many VET graduates from the “13th and 14th year” can put their acquired technical skills immediately into practice during their military service. They enter the civilian labour market with substantial practical experience in their profession. Work-based learning should therefore focus on post-secondary VET.

One possibility to overcome barriers to employer participation would be to introduce sectoral training levies or the establishment of sectoral training associations, in agreement with social partners. These have been successfully implemented in several European countries, and share the cost of work-placed training between all employers of a sector. For example, Hungary recently introduced Sectoral Training Centres to provide training and help firms dealing with administrative tasks. In Germany, there is a long tradition of training centres governed by the Chambers of Commerce.

Apprentice wages are relatively low, which lowers the cost for firms (Kuczera, Bastianić and Field, 2018[72]). However, many VET students are older if they enrol in the programme after military service, and around half complete VET courses part-time in the evening while engaging in full-time work. Therefore they may demand higher compensation for work placements than young apprentices in other countries. The government could financially support work placements, especially of underrepresented groups and those without practical professional experience from military service. In Canada, for example, CAD 5000 (and higher amounts for certain disadvantaged and priority groups) are available for firms who offer work placements to post-secondary students.

Figure 2.18. Take-up of VET is low

Share of young adults with upper-secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary qualifications that also hold VET, adults aged 15 to 34, %, 2018 or latest available year

Note: VET refers to Vocational Education and Training. OECD is an unweighted average of the countries shown.

Source: OECD (2020), OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1686c758-en.

Quality of VET can also be improved by empowering students to make better informed choices about programmes and training providers. This complements the authorities’ current efforts to increase the quality of training providers and to provide training with good value for money. The government will condition funding for post-secondary VET institutions on demonstrated minimum wage returns, 6% for most courses and 4% for shorter programmes. To guide student enrolment choices, statistical information on wage returns and graduate outcomes in VET is now made public through the Avodata tool that also publishes wage information for tertiary education graduates. Ideally the collection, analysis and dissemination of labour market information of VET graduates should be integrated into a single labour market data hub (see below).

The government should expedite and complete the process of creating a National Qualifications Framework (NQF). Such a framework would help give clear recognition to the different secondary and post-secondary qualifications, including VET, as part of an integrated model of life-long learning. This is important in the context of fragmented accreditation: secondary vocational schools are supervised by the Ministry of Education, technical colleges offering VET are accredited by the Labour Branch in the Ministry of Economy, while academic colleges and universities are accredited by the Council of Higher Education, and the IDF has its own system of qualifications. In addition, short-cycle adult training course are offered by a plethora of providers, including the IES, different ministries, and many local and private institutions. In a changing world of work, such incremental training to update and upgrade skills is becoming increasingly important (OECD, 2019[70]). Clearly defined learning outcomes would provide transparency about the educational content and the level of skills acquired, and help to establish comparisons or equivalence of individual components of different qualifications. This could raise the profile of VET qualifications by clarifying the skills they provide. Israel has been working with the European Training Foundation to establish a national framework on the model of the European Qualifications Framework (Box 2.3) and a working group of experts has been established. However, few concrete steps have been taken, despite a government resolution from 2015 that created the necessary legal basis for developing the NQF (European Training Foundation, 2021[75]).

Figure 2.19. More young people aspire to skilled professions than in most other countries

% of 15-year-olds who aspire to skilled occupations, PISA 2015

Note: Skilled occupations include professionals, managers, technicians and associate professionals, which typically require post-secondary education and training including post-secondary vocational and longer academic degrees. PISA data in Israel are representative for the Non-Haredi Jewish and Arab education streams.

Source: Kuczera, M., T. Bastianić and S. Field (2018), Apprenticeship and Vocational Education and Training in Israel, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302051-en.

Figure 2.20. Work-based learning is low

Share of VET students enrolled in combined school- and work-based programmes, 2020

Note: VET students in upper-secondary education.

Source: OECD Education Statistics database.

Box 2.3. The European Qualifications Framework (EQF)

In the European Union, the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) forms the basis for 38 national qualifications frameworks. The EQF groups qualifications into eight reference levels defined in terms of learning outcomes, each with an increasing level of complexity, abstraction, and demands on autonomous thinking and judgement. The framework eases the portability and transfer of qualifications across systems, sectors and learning contexts. It also facilitates the recognition of qualifications obtained abroad. By mapping qualifications based on learning outcomes, the EQF helps establish equivalence of qualifications from different education and training sectors, and clarifies where and how they are related to each other. This helps in pointing out pathways between different qualifications, and in defining how different qualifications should be valued.

The EQF serves as an important reference point for NQF, including for countries that are not members of the European Union. Türkiye, Switzerland, and Norway all have referenced, i.e. formally linked, their NQF to the EQF. Australia and New Zealand have carried out pilots comparing their NQF with the EQF. In many countries, the EQF has served as a blueprint for the development of comprehensive national qualifications frameworks based on learning outcomes.

The government should also enhance mobility between different qualifications. Currently, the opportunities to acquire labour market skills for young people who fail to obtain a Bagrut are limited. All secondary schools, including vocational schools, notionally prepare pupils for the Bagrut examination, which is the only fully recognised secondary qualification. The Bagrut exam forms a single entry gate to tertiary education. Most tertiary education programmes require a Bagrut to a certain standard, plus satisfactory performance on a national psychometric test. Many Haredi or Arab-Israeli students do not meet this requirement. One option for them is to attend foundation year programmes offered by some universities to prepare talented but insufficiently prepared candidates for admittance as full undergraduate students. The government should support expansion of these pathways to enable more students to access higher education. Another option for students with insufficient Bagrut results is to choose other degrees instead. For example, a third of institutions that train practical engineers are Haredi seminaries, which exclusively enrol Haredi women. Despite their generally good reputation and earnings potential relative to other non-technical fields, practical engineer graduates tend to play a subsidiary role in workplaces, since they are not educated to the same level as a full engineer trained at an academic college or university.