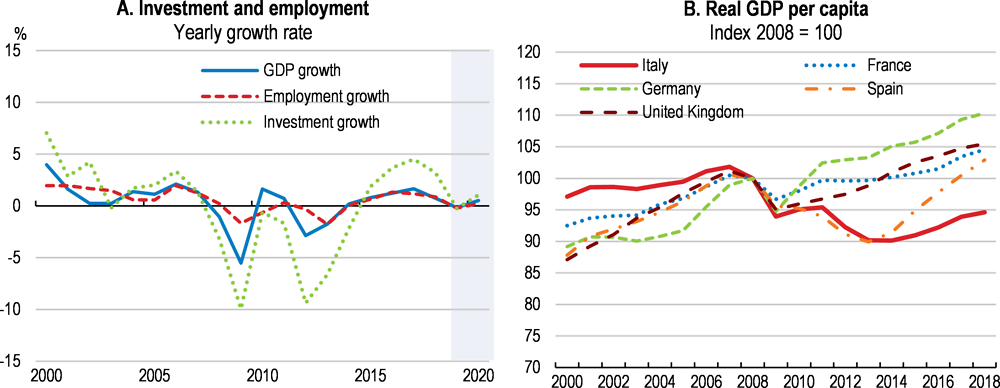

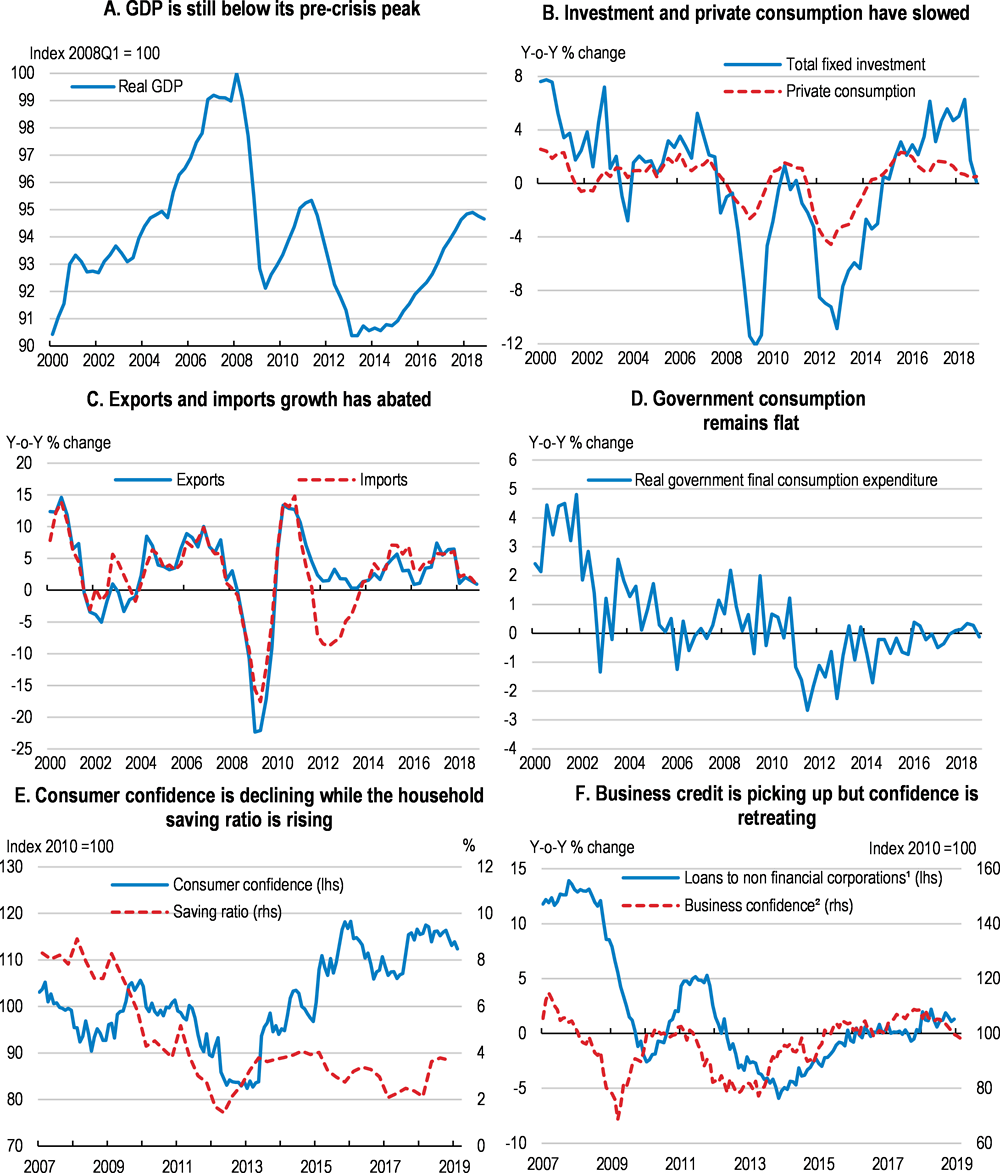

Supportive global economic conditions, expansionary monetary policy, structural reforms and prudent fiscal policy bolstered Italy’s gradual economic recovery for the past 4 years. Exports, private consumption and more recently investment were the main drivers of the recovery supported by rising external demand, a shift of export industries towards higher value added products and labour market reforms that contributed to raise the employment rate by 3 percentage points (Figure 1, Panel A).

OECD Economic Surveys: Italy 2019

Key policy insights

Figure 1. Italy’s economic recovery has been weak

However, the recovery is now slowing, after having been weaker than in other countries, and real GDP per capita is still below its pre-crisis peak (Figure 1, Panel B). Moreover, the social and economic wounds inflicted by the crisis have not yet healed. Poverty rates remain high, especially among the young, and real GDP per capita is roughly the same as 20 years ago. Low productivity growth and large social and regional disparities are long-standing challenges. While Italy does well in some areas of well-being, such as work-life balance, social connections and health status, it underperforms in others, such as environmental quality, education and skills, with Italian poorer regions performing markedly worse than more advanced ones.

Raising economic growth, reducing regional and social divides, and ensuring future generations enjoy the same environmental services as those of today will be challenging and require vigorous policy actions. Against this background, the main messages of this Survey are:

Developing and implementing a credible medium-term programme of deep structural reforms is key to boosting productivity, raising employment and job quality, and reducing poverty, alongside strengthening the fiscal balance. Further progress on raising public administration efficiency, reducing administrative barriers and raising competition would help to achieve this. Tax and government spending policies should focus on raising tax compliance, boosting efficient investment programmes and ensuring social spending is sustainable, well targeted and fair across generations.

Tackling the large social and regional divides hinges on raising employment in the formal sector and enhancing skills. Introducing in-work benefits along with a moderate guaranteed minimum income, such as the Citizens’ Income, would strengthen work incentives. Drastic improvements in job-search and training programmes are necessary to improve job prospects, reduce job-skills mismatch and poverty.

Improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the public administration and of regional policies is a pre-requisite to provide basic public goods and services across the whole country, protect the environment, and engender better opportunities and more economic and social security for all.

Growth has stalled amid persistent economic and social challenges

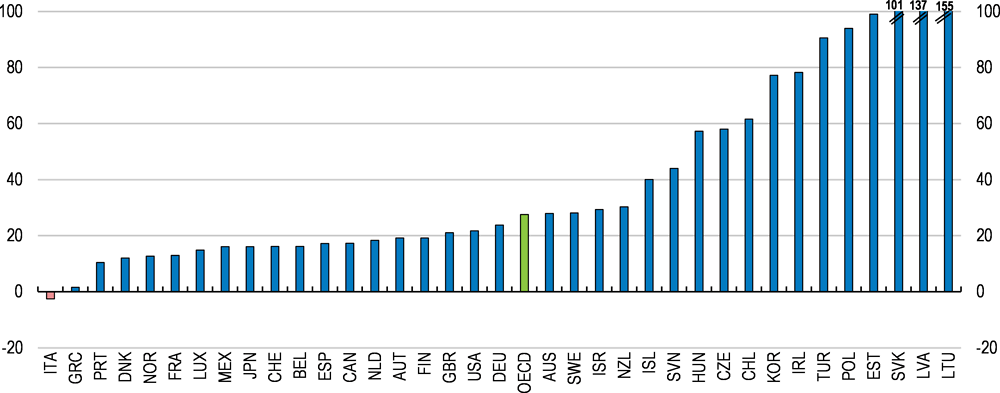

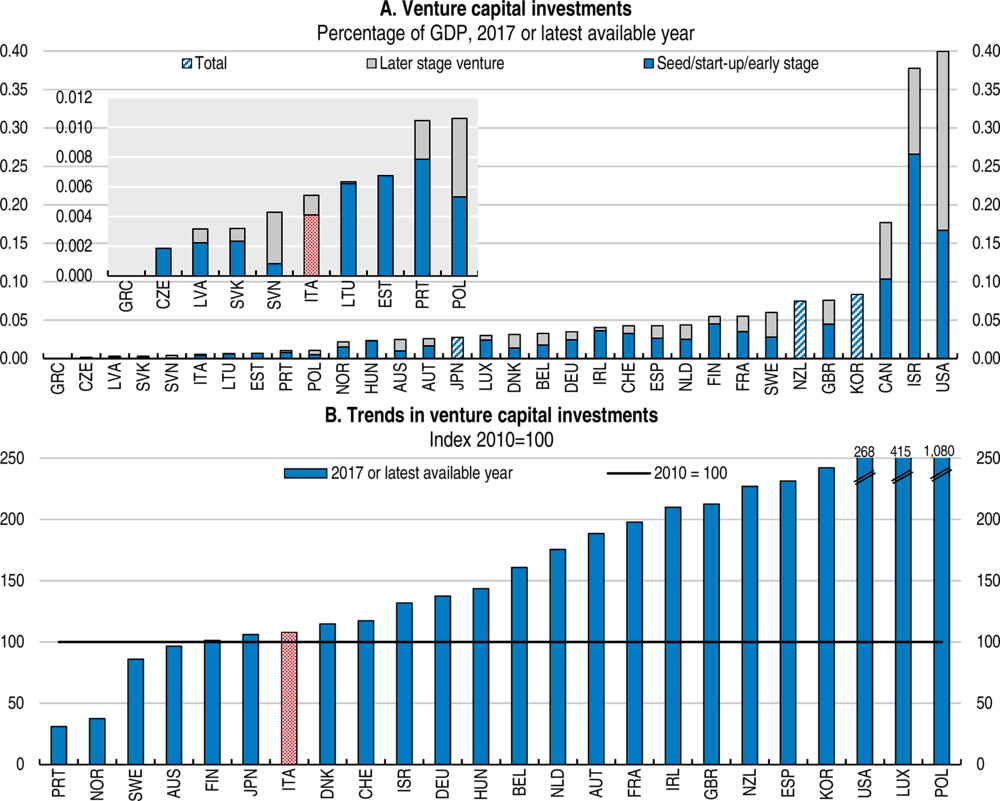

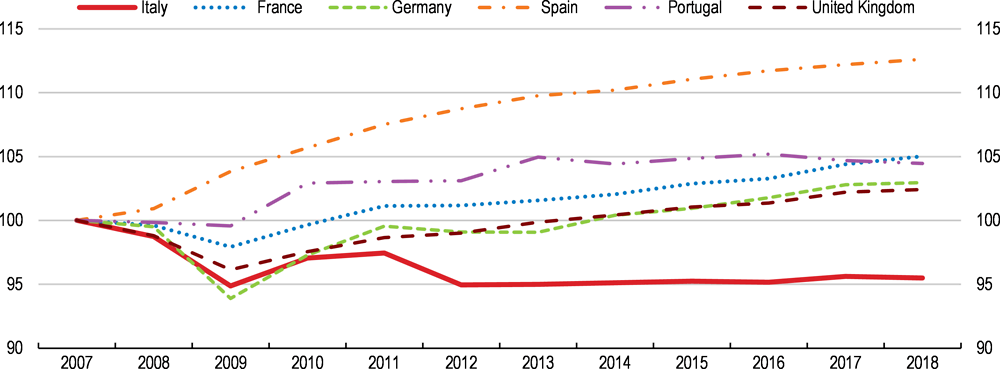

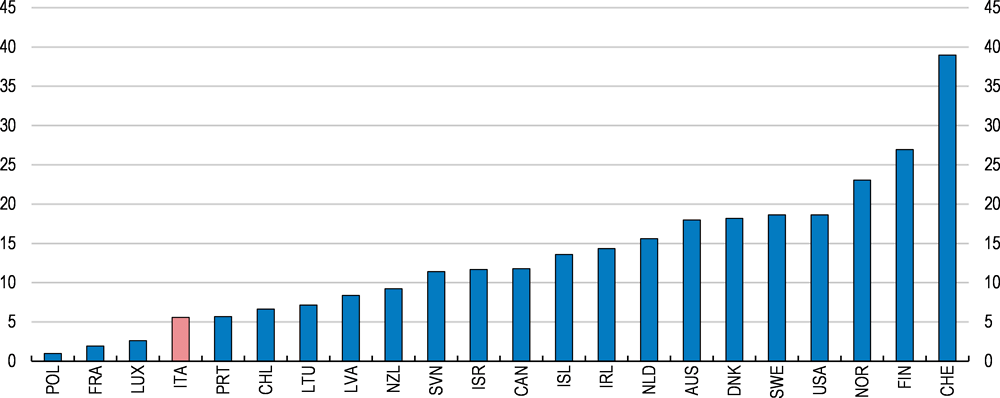

Italy continues to suffer from long-standing social and economic issues. Material living standards, as measured by GDP per capita, are about the same as in the year 2000 (Figure 2) and 8% below the pre-crisis peak. Absolute poverty rates for young people rose sharply in the aftermath of the crisis and remain high (Figure 3). Though the employment rate has increased, it is still one of the lowest among OECD countries. Job quality, as gauged by OECD Job Quality Framework is low (OECD, 2018[1]) and the mismatch between people’s jobs and their skills is high by international comparison. The level of investment, though recovering, is only 80% of the 2005-2008 average, while productivity growth has been sluggish or negative for the past 20 years.

Figure 2. Italy’s GDP per capita is at the same level of 20 years ago

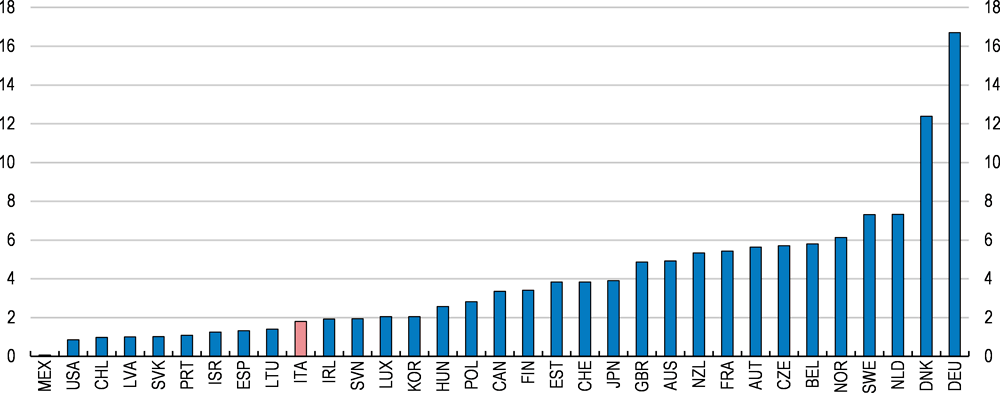

Percentage difference in real GDP per capita between 2000 and 2018

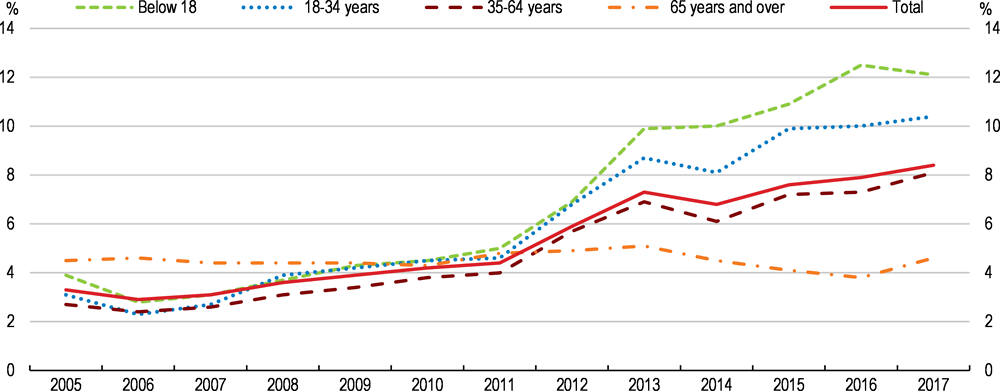

Figure 3. Poverty rates rose during the crisis and remain high, especially for the young¹

% of age groups living in households in absolute poverty

1. The ISTAT absolute poverty measure reports the share of individuals belonging to households with overall consumption expenditure below a socially necessary minimum, adjusting for the number and age of household members and price levels in the household’s location.

Source: ISTAT Poverty database.

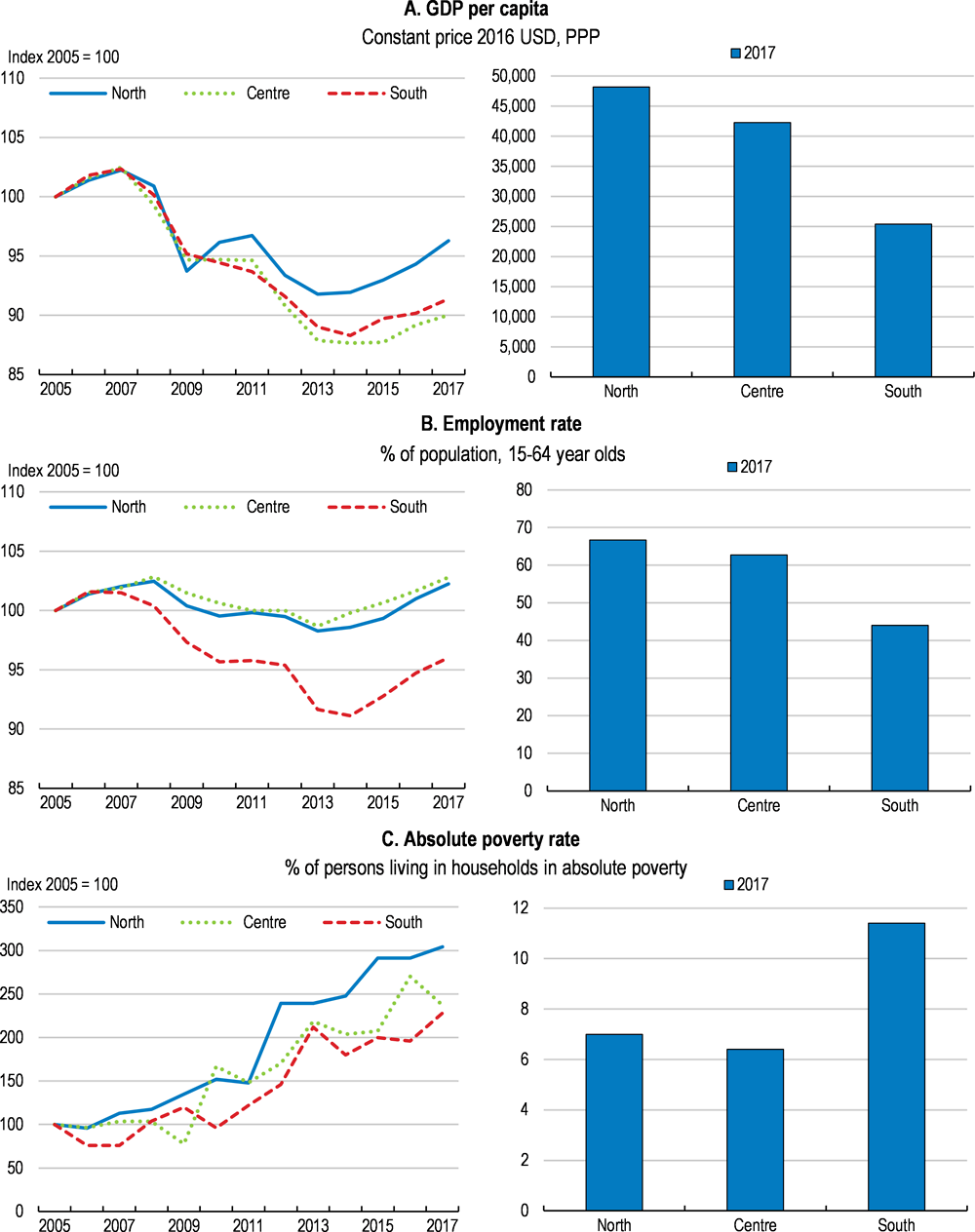

Italy’s society continues to be riven by large regional disparities. Large regional differences in GDP per capita and employment have widened further over the last 20 years while poverty rates spiked over the crisis also in northern regions and remain high (Figure 4) as detailed in the thematic chapter. Regional disparities in employment rates, which are especially pronounced for women, largely explain the differences in living standards between the richest and poorest regions. A high share of the young, especially in lagging regions, is not in employment, education or training, reducing human capital and damaging job prospects. The dearth of job opportunities pushes many young people to emigrate exacerbating Italy’s already fast population ageing and depriving the country of energy, talent and entrepreneurship.

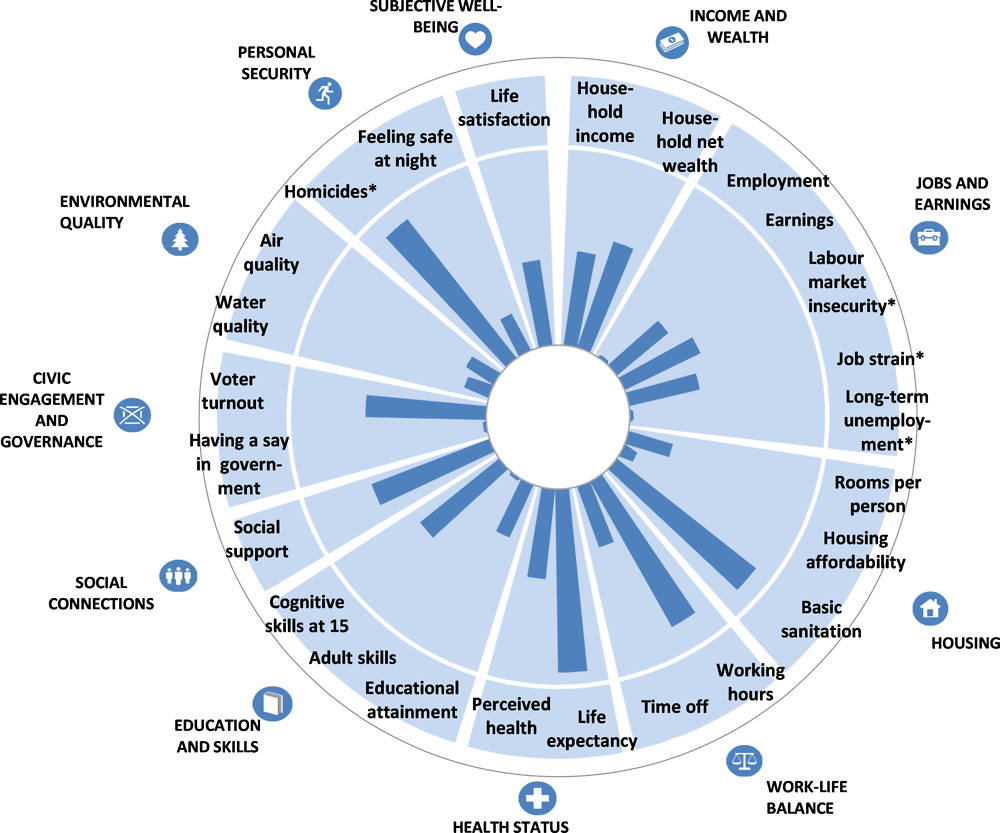

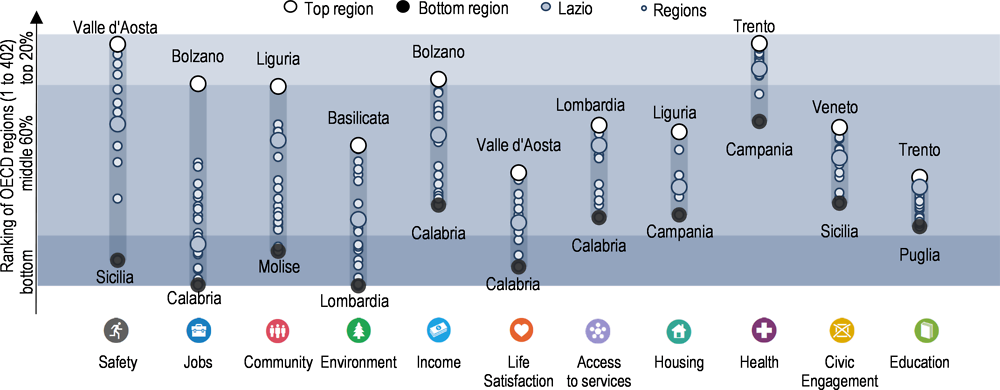

Italy’s well-being indicators continue to lag those in other countries in several dimensions, reflecting social, economic and environmental problems (Figure 5). While Italy performs better than the OECD average with respect to work-life balance, social connections and health status, it continues to underperform in other areas, especially subjective well-being, environmental quality, jobs and earnings, housing, and education and skills. Regional disparities are greater for wellbeing than income alone, with southern regions performing worse than northern ones with the exception of areas such as environment and to some extent civic participation (Figure 6).

Figure 4. Regional disparities in GDP per capita, poverty and employment are large and increasing

Figure 5. Italy’s wellbeing continues to lag peers in many dimensions

Note: This chart shows Italy’s relative strengths and weaknesses in well-being when compared with other OECD countries. For both positive and negative indicators (such as homicides, marked with an “*”), longer bars always indicate better outcomes (i.e. higher well-being), whereas shorter bars always indicate worse outcomes (i.e. lower well-being). If data are missing for any given indicator, the relevant segment of the circle is shaded in white.

Source: OECD (2017) OECD Better Life Index.

Figure 6. Italy’s regional dispersion in well-being is high

Source: OECD Regional Well-Being database.

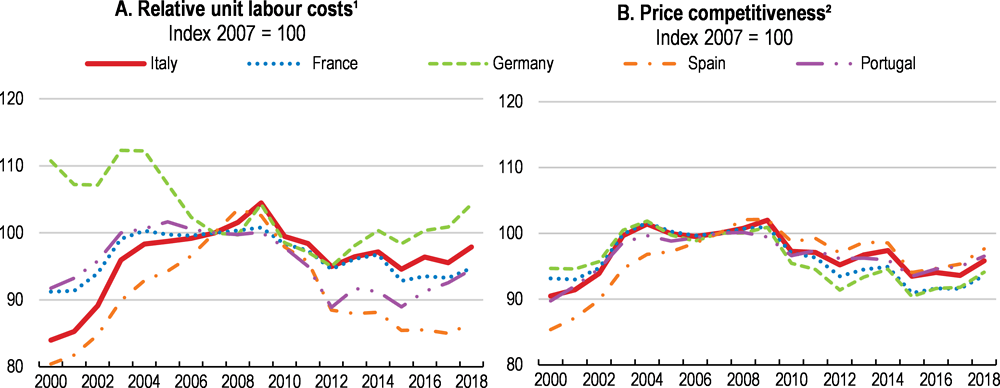

Growth has stalled

Exports and private consumption growth have weakened (Figure 7). Waning external demand and uncertainties about global trade arrangements have hurt exports (Figure 7, Panel C). Analysis suggests that since 2010 Italian exports have shifted to higher value added sectors, less exposed to competition from low cost countries (Bugamelli et al., 2017[2]). Relative price- and cost-based indicators have varied little since 2011 (Figure 8), suggesting that changes in prices and production costs have played only a minor role in the rise and fall of exports. Exports dropped in the first half of 2018 but recovered somewhat afterwards.

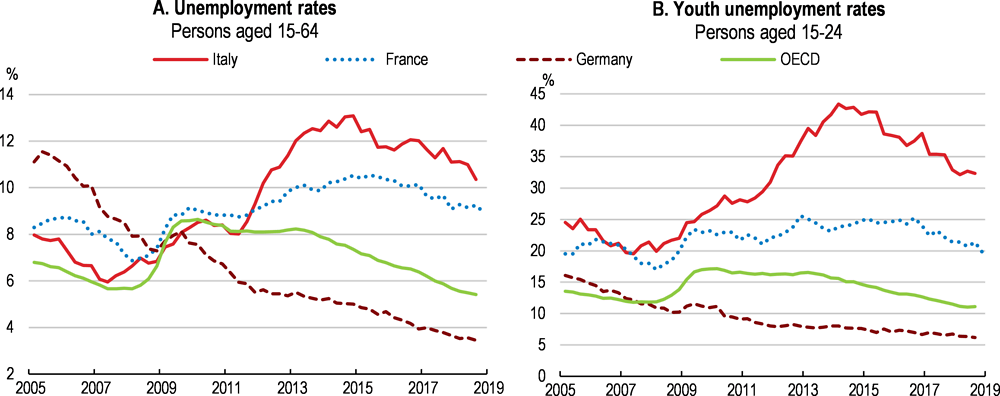

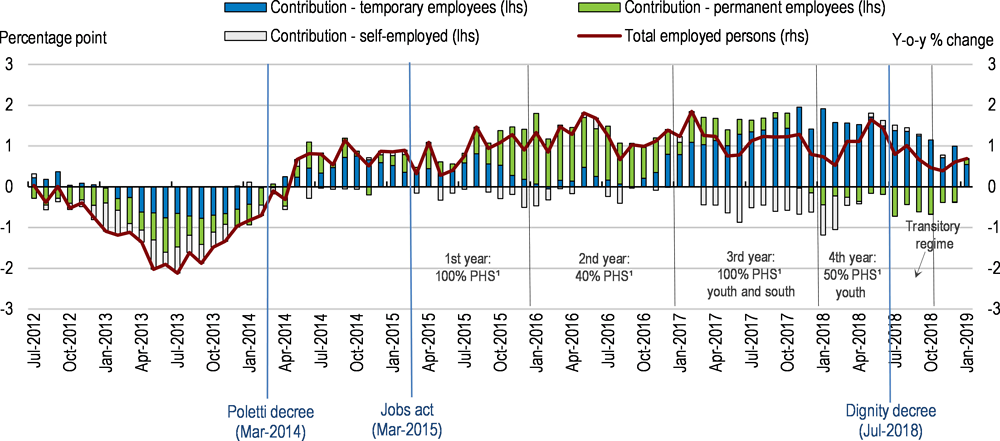

Slowing job gains and lower real wages have moderated private consumption growth, and along with rising uncertainty, helped raise the household saving rate (Figure 7, Panel E). Job quality is low (OECD, 2018[1]). An increasing share of new jobs is temporary following the expiration of social security contribution exemptions for permanent contracts. Unemployment has dropped but remains high, especially for youth and women (Figure 9), while discouraged job seekers have started to leave the labour force. At the same time, in 2018 energy prices pushed up consumer price inflation, which has risen slightly above private‑sector wage growth, curtailing household purchasing power gains. While public sector wages increased significantly in 2018Q2, after 10 years of wage freeze, private sector wage growth remains modest and below consumer price inflation.

Household debt remains stable at about 60% of gross disposable income, nearly 40 percentage points below the Euro area average. Moreover, the share of household debt held by vulnerable households (defined as those with a debt-service ratio above 30% of their disposable income and with disposable income below the median) is lower than in the past – about 11% against 24% in 2008 (Bank of Italy, 2018[3]).

Figure 7. The recovery has weakened as export and private consumption growth have abated

1. Adjusted for securitisation.

2. Manufacturing, construction, services and retail trade sectors.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 104 database, including more recent information; ISTAT; and Bank of Italy.

Figure 8. Relative unit labour costs and price competitiveness are flat

1. Ratio of own unit labour costs against those of trading partners. An increase corresponds to lower competitiveness.

2. Real effective exchange rate, CPI weights. An increase corresponds to lower competitiveness.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 104 database, including more recent information.

Figure 9. Unemployment has fallen but remains high, especially for the young

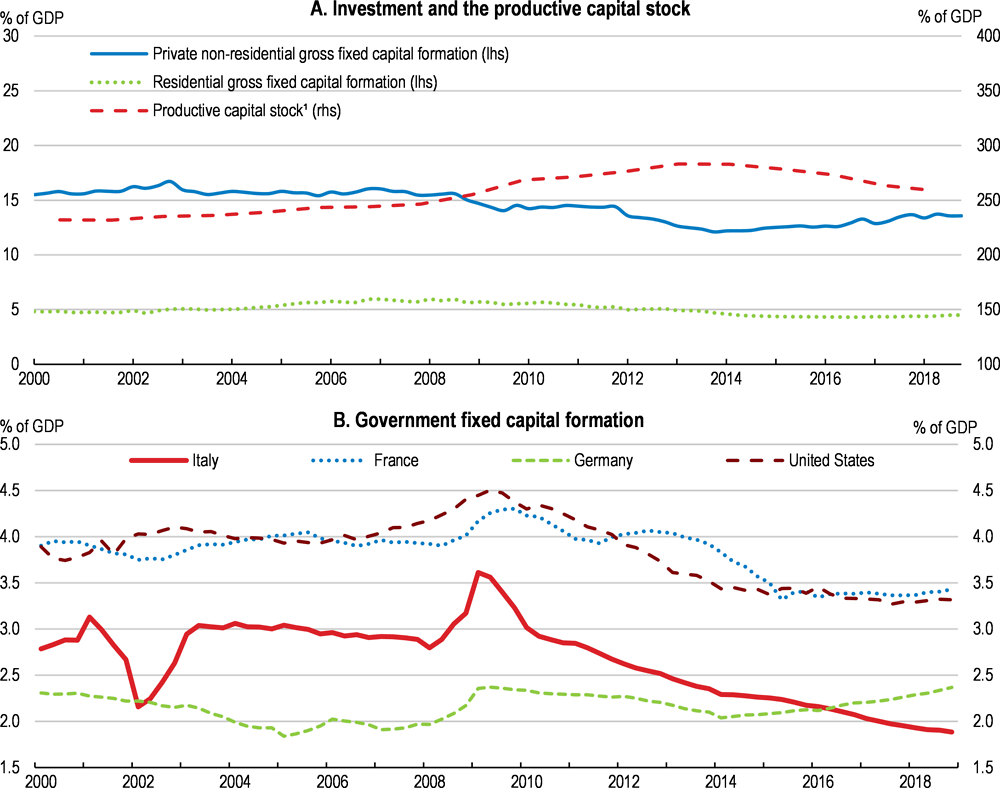

Productivity growth has remained sluggish since the early 2000s (Figure 10). An encouraging sign is that private investment has expanded since 2015, from a very low level, supported recently by fiscal incentives for private investment linked to the Industry 4.0 Plan and renewed bank lending to non-financial corporations (Figure 7, Panel F; Figure 11, Panel A). Bank lending rates have remained low, although they have started to rise since mid-2018 as government bond yields have risen. Bank lending to the manufacturing and services sectors has increased since late 2017, albeit recently at a more moderate pace, due to improving profitability and balance sheets. Bank lending to the construction sector is still falling, reflecting the sector’s still depressed conditions and low profitability.

Figure 10. Aggregate productivity¹ has not increased for many years

Index 2007 = 100

1. Real GDP per worker.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 104 database, including more recent information.

Public investment continues to fall, hampered by long-standing planning and execution delays that result in unspent funds. Public investment has dropped to less than 2% of GDP and is now at its lowest level in 25 years (Figure 11, Panel B). Since early 2015, construction activity has been hovering at levels 10% below mid-1990s levels, and 40% below the pre-crisis peak. However, some indicators point to an incipient recovery as the demand for mortgages and the number of building permits are rising, while house prices have stopped falling.

Expansionary fiscal policy and low growth increase the risks from high public debt

The 2019 budget involves net new measures amounting to 0.6% of GDP, mostly consisting of higher social spending (Box 1). After discussions with the European Commission, the government decided to lower the budget deficit target for 2019 from 2.4% to 2% of GDP, assuming GDP would grow by 1% in 2019. Following this decision, the Commission decided to stop the process of opening an excessive deficit procedure against Italy. The main measures for 2019 include repealing the planned VAT hike, lowering the early retirement age (for a three year period), introducing a new and more generous guaranteed minimum income scheme (the Citizen’s Income), and a reduction in the tax burden for the self-employed and micro-enterprises through the extension of the simplified tax regime (i.e. flat tax). These expansionary policies will be only partly offset by some spending cuts and higher business income taxes mainly through revenue-raising measures on banks and insurance companies, the abolition of the allowance for corporate equity and of the new entrepreneurial income tax and of the investment super-amortisation scheme. The budget law also foresees large hikes in VAT rates amounting to about 1.3% of GDP in 2020 and 1.6% in 2021, leading to a decline in the budget deficit, according to government projections, to 1.8% of GDP in 2020 and 1.5% in 2021.

Figure 11. Private investment is rising whereas public investment has fallen to record low levels

1. Total economy less housing.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 104 database, including more recent information; and OECD National Accounts database.

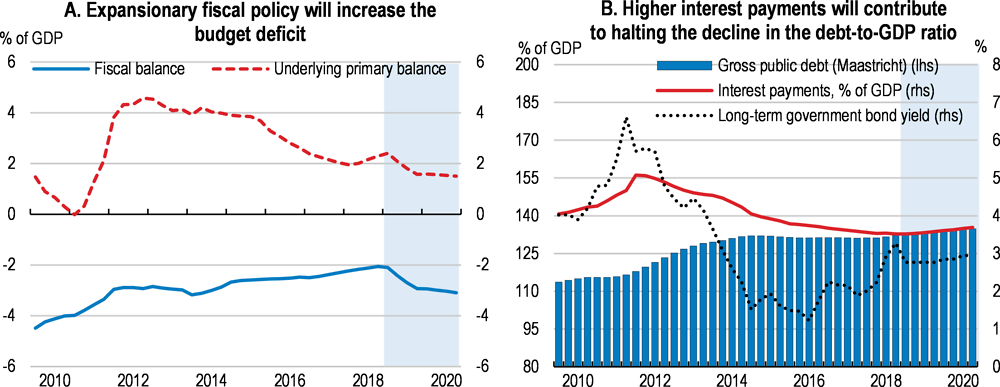

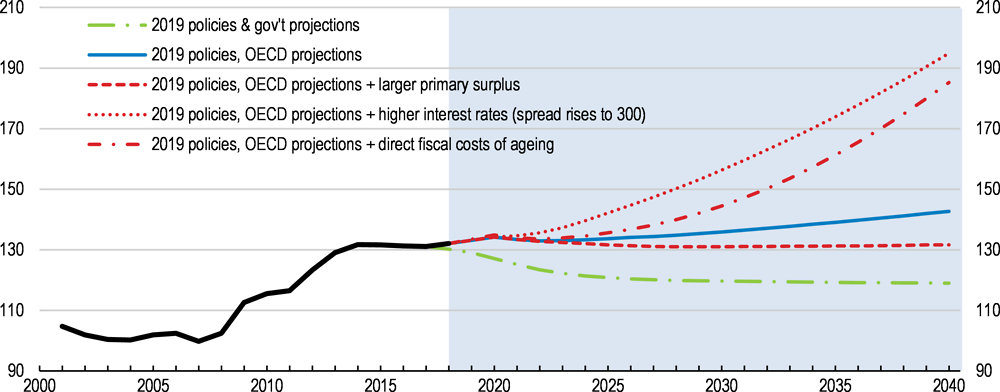

According to the projections presented in this Survey, the general government budget deficit will rise from 2.1% of GDP in 2018 to 2.5% in 2019 (Figure 12, Panel A). The difference with government’s projections is attributable to the projected fall in real GDP in 2019 (-0.2%) and lower increase in the GDP deflator. These projections also assume that the government will not implement the planned VAT hike for 2020-21. For this reason, and assuming no other major policy change, the budget deficit is projected to rise further to 3% of GDP in 2020. Given slow growth, low inflation and rising interest costs and a larger deficit, the public debt ratio (on a Maastricht basis) will cease to decline and increase to 135% of GDP in 2020 (Figure 12, Panel B). In the longer-term, under current policies the debt will gradually rise. If spreads widened again, the increase in the debt ratio would be considerably faster (Figure 13).

Figure 12. Fiscal policy will turn expansionary and the debt ratio will barely decline

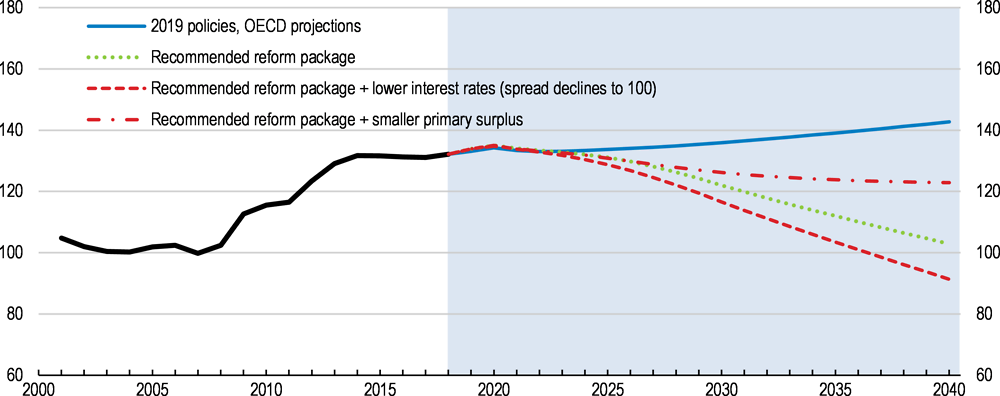

Figure 13. Under current policies the debt to GDP ratio will remain high and vulnerable to risks

Projected public debt under 2019 policies and budget and interest rate scenarios, percent of GDP

Note: The “direct fiscal costs of ageing” scenario assumes that ageing-related costs (pension spending, health care, long term care, less reduced spending on education as the school-age population declines) greater than the spending incurred in 2020 are funded through debt. Assumptions underlying each debt scenarios are summarised in Table 1.

Source: OECD calculations

Table 1. Assumptions of 2019 budget debt sustainability scenarios

|

|

2020 |

2025 |

2030 |

2035 |

2040 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2019 policies & gov't projections |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real GDP growth |

%, annual |

1.1 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

|

Primary fiscal balance |

% GDP |

2.0 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

|

|

GDP deflator growth |

%, annual |

1.8 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

Implicit effective nominal interest rate |

% |

2.9 |

4.0 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

|

|

Spread between effective interest rate and risk-free rate |

bps |

219 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

|

|

2019 policies, OECD projections |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real GDP growth |

%, annual |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

|

Primary fiscal balance |

% GDP |

0.6 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

GDP deflator growth |

%, annual |

1.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

Implicit effective nominal interest rate |

% |

2.9 |

4.0 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

|

|

Spread between effective interest rate and risk-free rate |

bps |

219 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

|

|

2019 policies, OECD projections + larger primary surplus |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Real GDP growth |

%, annual |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

|

Primary fiscal balance |

% GDP |

0.6 |

2.4 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

|

|

GDP deflator growth |

%, annual |

1.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

Implicit effective nominal interest rate |

% |

2.9 |

4.0 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

|

|

Spread between effective interest rate and risk-free rate |

bps |

219 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

|

|

2019 policies, OECD projections + higher interest costs (spread remains at 300) |

|

|

|

||||

|

Real GDP growth |

%, annual |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

|

Primary fiscal balance |

% GDP |

0.6 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

GDP deflator growth |

%, annual |

1.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

Implicit effective nominal interest rate |

% |

2.9 |

5.5 |

6.1 |

6.3 |

6.5 |

|

|

Spread between effective interest rate and risk-free rate |

bps |

219 |

300 |

300 |

300 |

300 |

|

|

2019 policies, OECD projections + direct fiscal costs of ageing |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Real GDP growth |

%, annual |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

|

Primary fiscal balance |

% GDP |

0.3 |

1.0 |

0.3 |

-0.9 |

-1.8 |

|

|

GDP deflator growth |

%, annual |

1.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

Implicit effective nominal interest rate |

% |

2.9 |

4.0 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

|

|

Spread between effective interest rate and risk-free rate |

bps |

219 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

|

Source: OECD.

Box 1. 2019 budget: main measures

According to the government’s budget documents and the Parliamentary Budget Office, the 2019 budget consists of measures that will increase spending by 0.4% of GDP and reduce revenues by 0.2% of GDP. The main measures are the following:

Cancelling the automatic increases in VAT rates: The 2019 budget law cancels the increase in VAT rates planned for 2019, amounting to about 0.7% of GDP. At the same time, it introduces new VAT safeguard clauses for 2020 and 2021 that will raise the standard VAT rate to 25.2% in 2020 and 26.5% in 2021 (from the current 22%), unless compensatory measures are undertaken.

Guaranteed minimum income: A guaranteed minimum income scheme (the Citizen’s Income) is introduced to replace the existing programme, which was introduced in 2018 (the REI). The new guaranteed minimum income is more generous than the REI as it is expected to pay up to EUR 780 per month to singles with no income, with the benefit adjusted to take into account family composition according to an equivalence scale (like the REI). This new measure is conditional on participating in job-search and training policies, and community jobs. The government allocated 0.3% of GDP from 2019 to 2021 for the Citizen’s Income.

New early retirement scheme: Workers aged 62 years and with 38 years of contributions will be allowed to retire with a reduced pension. This scheme is valid for three years. This measure will be partly financed with a reduction of the adjustment to inflation for pension above EUR 1 500 and a solidarity tax on high pensions. However, these two measures are expected to raise only 0.02% of GDP in 2019 and about 0.05% in 2020 and 2021. For 2019, the extra spending on the new early retirement scheme will depend on the take up rate and is expected not to exceed 0.2% of GDP in 2019 and 0.3% of GDP in 2020 and 2021. The 2019 budget also discontinue until to 2026 the link between the updates of early retirement contribution requirements and developments in life expectancy.

Flat tax: It raises the income thresholds from EUR 45 000 to EUR 65 000 of the simplified tax regime that applies a 15% tax rate to the income of self-employed and micro-enterprises. The budget also introduces from 2020 onwards a new bracket in the simplified tax regime between EUR 65 000 and EUR 100 000 of income that will be taxed at 20%. Eligibility is based on the previous year’s income. This measure will reduce tax revenues by less than 0.1% of GDP yearly in 2019-2021.

Tax changes for businesses: The budget repeals the allowance for corporate equity (which was introduced to restore the neutrality between debt and equity financing) and the tax on entrepreneurial income (IRI) that was scheduled to enter into force in 2019 and to apply the corporate income tax rate (24%) to all business incomes irrespective of the business’s legal form. The budget also lowers tax incentives linked to the Industry 4.0 plan while it increases the hyper-amortization scheme from 150 to 170% for investments up to 2.5 million euros.

Digital services tax: 3% tax rate on revenues from online advertising, sales and data processing. The tax applies to companies with a total amount of global revenues above EUR 750 million and revenues from digital services realized in Italy above EUR 5.5 million.

Measures to deal with tax debts. The extension of the “rottamazione cartelle” (file-shredding) measures (started by previous governments) allows the tax debtor to pay the tax debt in instalments over 5 years; fines and interest charges relating to the tax debt are written off. Other forms of tax amnesty are new and involve not only fines and interest charges but also the tax debt: “condono” writes off tax debts (including interest charges and fines) relating to motor taxes and fines, and local taxes incurred between 2000 and 2010 and up to EUR 1 000; “saldo e stralcio” writes off the tax debt (relating to personal income taxes and including social security contributions) incurred between 2000 and 2017 by paying a share (from 16% to 35% according to personal economic conditions) of the tax debt (including interest charges and fines); “liti pendenti”, allows taxpayers to terminate ongoing court disputes by paying a share of the tax debt (40% if the debtor won a first instance judgment, falling to 5% when the dispute is at the final appeal and the debtor all lower instance judgments; the debtor can write off also the debt by paying 90% of it if he is waiting for the first instance judgment).

The 2019 budget rightly aims to help the poor but given its composition, the growth benefits are likely to be modest, especially in the medium term. The guaranteed minimum income (the Citizen’s Income) strengthens anti-poverty programmes significantly by targeting transfers toward poor households. The transfer is conditional on individuals engaging in job-search and training programmes and community jobs. However, as discussed below and in the thematic chapter, the job-search and training programmes are inadequate in many regions, risking to blunt the effectiveness of the Citizen’s Income in reducing poverty and to inflate its costs.

The network of regional public employment services (PES) will be responsible for administering the Citizen’s Income. This contrasts with the administration of the Inclusive Income Scheme (REI), expanded in 2018, as municipalities’ social services were responsible for administering it and developing personalised social-inclusion projects in collaboration with the health services, the school system, public employment services and non-profit organisations offering services to poor individuals. To fulfil these responsibilities, many municipalities have strengthened their social services. Ensuring that PES closely and effectively collaborate with municipal social services, as planned, will deliver better and faster results.

The budget introduces a new early retirement scheme for people with 62 years of age and at least 38 years of contributions. This scheme is temporary and will expire in 2021. Those opting to retire earlier will receive a lower pension than what they would have received with pre-existing requirements. However, the planned reduction in the pension will not necessarily be actuarially fair with the result that the new scheme may increase pension spending permanently. The new early retirement scheme measure will lower growth in the long run by reducing the number of older people in work. If not actuarially fair it will worsen intergenerational inequality and add to already high pension spending.

Given Italy’s ageing demographics, health and long-term care spending needs will rise alongside pension costs. Italy has improved management of health and long-term care policies in recent years, compared with many countries, which will limit the increase in the costs of these policies to 0.6% of GDP between 2020 and 2030 (European Commission, 2018[5]). Nonetheless, if the rising costs from ageing are not offset through spending cuts or revenue measures they will threat the sustainability of the public debt (Figure 13).

The digital services tax envisaged by the 2019 budget (Box 1) has not yet been introduced as it needs implementing regulations. This type of tax follows several other countries introducing similar initiatives, and the European Parliament voting to support a similar EU-wide directive (European Parliamentary Research Service, 2018[6]). Many of the enterprises that would be subject to the digital services tax are headquartered in the United States. A G20/OECD process is developing measures that adapt existing approaches to taxing firms to the challenges of digital technologies. These technologies allow firms to undertake significant business in a country without being physically present, make intangible sources of value more important, and increase risks from aggressive tax planning (OECD, 2018[7]). Members of the G-20/OECD process are committed to reaching a consensus-based, long-term solution in 2020, and have not reached a consensus about the need or merit of interim measures (OECD, 2019[8]).

Past recommendations on fiscal issues

|

Past Survey Recommendations (Key recommendations of the 2017 Survey are in bold) |

Actions taken since 2017 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Evaluate the effectiveness of recently introduced research and development tax credits and other fiscal incentives in terms of innovation outcomes and forgone tax receipts. |

Extensive data being collected and analysed on firms benefiting Start-up Act (and Industry 4.0). |

|

Stick to the planned fiscal strategy so as to bring the debt-to-GDP ratio onto a declining path. |

The 2019 budget marks a significant departure from the previous fiscal strategy. |

|

Promote greater use of centralised procurement, cost information systems and benchmarking. |

Public procurement management continues to improve, through more contracting through central authority. Procurement agencies’ capacity is improving. IT systems are facilitating comparisons of prices paid by difference agencies. ANAC is taking a stronger role in supervising and authorising contracting. |

|

Strengthen the coordinating role of the central government to set and enforce minimum standards in project preparation and execution and to enhance the administrative capacity of all agencies using national and European funds for investment. |

The Government has proposed the creation of a task force to centralise information on ongoing projects through the active management of a centralized database and direct links with the expense terminals, systematically promoting the monitoring, evaluation and coordination of investments. The Government will also create a central unit with the task of offering technical assistance to ensure quality standards for the preparation and evaluation of programs and projects by central and peripheral public administrations are met. |

|

Continue to assess the magnitude of budgetary contingent liabilities, including the vulnerability of public finances to risks associated with the financial sector. |

New contingent liabilities are being accounted for correctly. The interventions in the banking sector have generated some contingent liabilities that have been audited by Eurostat and ECB and reflected in budget documents following their advice. Less than 3% of new firms with bank finance guaranteed through the Start-up Act have needed to call on this guarantee. |

|

Fully legislate and implement the already planned nationwide anti-poverty programme, target it towards the young and children and ensure it is sufficiently funded. |

A guaranteed minimum income programme, the REI, was rolled out nationally in Jan 2018 to all households with low income and assets conditional on participation in job search or other social services criteria. The delivery of REI social services builds on municipalities’ existing social protection services. The 2019 budget introduces a new guaranteed minimum income scheme (Citizen’s Income) to replace the REI that increases significantly the financial resources allocated to anti-poverty programmes and will to a large extent rely on Public Employment Services for job-search activation programmes. |

Growth will remain weak in the next two years

GDP growth is projected to contract by 0.2% in 2019 and expand by 0.5% in 2020. Rising uncertainty and higher interest rates will lower the propensity of households and firms to consume and invest, offsetting the effects of the fiscal expansion on activity. Slowing growth in Italy’s main trading partners will hinder export growth. Moderate investment growth will support weak import growth. Low inflation will result in modest real wage gains, which will only partly offset the negative effect of slowing employment growth and a rising household saving rate on private consumption.

The risk of renewed financial market turmoil would accelerate the expected gradual rise in borrowing costs for households and firms and sap confidence, reducing investment and consumption growth. Further spikes in government bond yields would hurt banks’ balance sheets and capital ratios, which could lead to lower lending. The aggravation of protectionism would harm international trade, lowering export growth and leading firms to cut back their investment plans. On the other hand, investment could prove more resilient than projected if the residential sector and construction recover faster than expected. Lower energy prices would boost household purchasing power and private consumption.

Table 2. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2010 prices)

|

|

2015 Current prices (EUR billion) |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

1 651 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

0.8 |

-0.2 |

0.5 |

|

Private consumption |

1 007 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Government consumption |

312 |

0.1 |

-0.2 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

279 |

3.7 |

4.5 |

3.2 |

-0.2 |

1.1 |

|

Housing |

72 |

1.5 |

3.1 |

3.4 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

|

Final domestic demand |

1 598 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

1.0 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

5 |

0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.1 |

-0.7 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

1 603 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

0.9 |

-0.4 |

0.6 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

493 |

2.3 |

6.4 |

1.4 |

2.7 |

2.3 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

446 |

3.8 |

5.8 |

1.8 |

2.1 |

2.7 |

|

Net exports1 |

48 |

-0.4 |

0.4 |

-0.1 |

0.2 |

-0.1 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

||||||

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

|

Output gap2 |

. . |

-3.4 |

-2.0 |

-1.5 |

-2.0 |

-1.9 |

|

Employment |

. . |

1.3 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

-0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Unemployment rate |

. . |

11.7 |

11.3 |

10.6 |

12.0 |

12.1 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

1.2 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

|

Consumer price index (harmonised) |

. . |

-0.1 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

Core consumer prices (harmonised) |

. . |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.8 |

|

Household saving ratio, net3 |

. . |

3.2 |

2.3 |

3.3 |

3.8 |

4.2 |

|

Trade balance4 |

. . |

3.4 |

3.2 |

2.8 |

. . |

. . |

|

Current account balance4 |

. . |

2.5 |

2.8 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

|

General government fiscal balance4 |

. . |

-2.5 |

-2.4 |

-2.1 |

-2.5 |

-3.0 |

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance2 |

. . |

-0.7 |

-1.4 |

-1.4 |

-1.5 |

-2.0 |

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance2 |

. . |

2.9 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

1.5 |

|

General government gross debt (Maastricht) 4 |

. . |

131.3 |

131.1 |

132.1 |

133.8 |

134.8 |

|

General government net debt4 |

. . |

127.4 |

125.0 |

125.2 |

126.8 |

127.9 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

1.5 |

2.1 |

2.6 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

3. As a percentage of household disposable income.

4. As a percentage of GDP.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 104 database, including more recent information.

Table 3. Low probability events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Vulnerability |

Possible outcome |

|---|---|

|

Slowing down of the reform process and confrontations with the EU in a context of slow global growth leading to a loss of confidence and downgrade of sovereign debt ratings |

Sovereign bond yields would rise markedly, pushing up debt servicing costs and leading to a debt crisis. |

|

Banks continue to increase sovereign bond holdings, aggravating the sovereign-bank loop in the context of political fragmentation and rising government bond yields |

Prolonged increase in government bond yields cause banks balance sheet losses, requiring banks to limit lending and seek recapitalization, and leading to lower equity values, loss of confidence and economic crisis. |

|

A steep rise in protectionism globally markedly reduces trade and the demand and prices for Italy’s exports |

A large and prolonged reduction in export production activity leads to lower investment and job losses, harming incomes and government revenues. |

Source: OECD.

Banks’ health has improved but is exposed to risks around the public finances

The improved health of the banking system is supporting private investment but its links with the public finances remain a risk. The government strategy to restore the banking sector to health based on a mix of resolution, recapitalisation and acquisitions has yielded fruit. The cost of the government intervention in the financial sector to date has been limited to about 0.3% of GDP, or 1.3% accounting for the assumption of some contingent liabilities. This compares favourably with the financial sector support offered by the government in other euro area countries (5.9% of GDP in Germany, 4.4% in Spain and 0.1% in France)

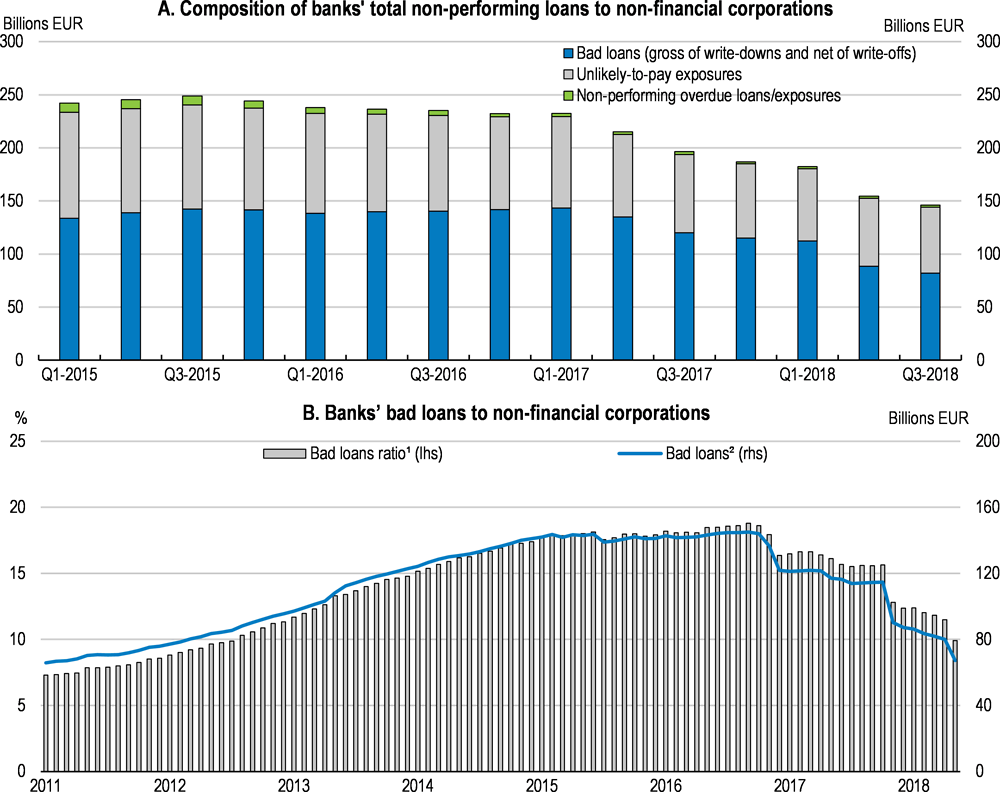

The stock of non-performing loans (NPLs) on banks’ balance sheet is falling (Figure 14). Loan quality has improved and the ratio of new non-performing loans to outstanding loans has dropped to pre-crisis level (2.8% for loans to non-financial corporations and 1.5% for loans to households). The reduction of the ratio of new non-performing loans is attributable to the 2015-18 economic recovery but also to a cautious approach by banks. In 2016-18, bank lending increased for firms in sound condition, while it continued to fall for riskier firms (Bank of Italy, 2018[3]).

The gross value of banks’ bad loans (the more severe type of NPLs) to non-financial corporations declined by almost 45% since its peak in February 2017 with banks disposing EUR 42 billion of bad loans in 2017 and nearly EUR 40 billion in 2018. From the late 2015 to the mid-2018, the coverage ratio for bad loans increased from 59 to 68% (from 45% to 54% for NPLs). Collateral and personal guarantees amounted to about 68% of the gross value of bad loans, in the mid-2018, as in the late 2016.

The progress in reducing NPLs is attributable to effective policy actions. The state-sponsored Guarantee on Securitization of Bank Non Performing Loans introduced in 2016 (OECD, 2017[9]) – which thus far has covered EUR 42 billion of securitised NPLs and has cost nothing to the Treasury – has been instrumental in developing a growing market for non-performing loans. In 2018 total NPL transactions in the secondary market were expected to be four times above those in 2017 and 20 times more than in 2013 (PWC, 2018[10]). Supervisors have undertaken robust and intrusive actions to accelerate NPL disposals. Significant banks submitted NPL-reduction plans and in 2018 banks’ disposals of NPLs were in line with those plans. Going forward, NPLs are expected to decline further. In March 2018, the eleven significant banks submitted updated NPL-reduction plans for the 2018-2020 period. At the end of 2018, the less significant banks with high NPLs also submitted plans according to the guidelines issued by the Bank of Italy in January 2018 to reduce NPLs (Bank of Italy, 2018[3]).

The rise in Italian government bond yields in 2018 has so far had only a limited effect on bank funding costs, though banks credit default swap (CDS) and banks’ bond yields have risen substantially and are now above those of European peers (Bank of Italy, 2018[3]). Banks have been increasingly relying on deposits to satisfy their funding needs. Recourse to the Eurosystem has remained stable since March 2017 after the last longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO II).

Though banks’ funding costs remain low for the time being, there is the risk they may rise considerably. The Italian government 10-year bond spread spiked in 2018. Though it receded from the peak in October 2018, it is still about 130 basis points higher than in April 2018. Estimates relating to the 2010-2011 period suggest that a 100 basis points increase in the 10-year government bonds’ spread could raise interest rates on fixed-term deposits and repos by about 40 basis points and yields on new bond issues by around 100 basis points (Bank of Italy, 2018[3]). Over the past two years, Italian banks have issued markedly fewer bonds, especially to households. The share of bonds in total bank funding dropped to just above 10% in late 2018 from 15% in late 2016. This share is lower than that of German and French banks (13.7% and 16.4% respectively) (Bank of Italy, 2018[3]). Italian banks’ recourse to international bond markets is especially limited.

Moreover, the end of the TLTRO II scheduled for 2020-21 and the introduction of the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities for bail in (MREL) will put additional upward pressures on banks’ funding costs. The introduction of the MREL might compel banks to issue large amounts of MREL-eligible bonds at the same time. Simulations by the EBA and ECB suggest that the cost of meeting MREL requirements will be limited for the whole banking sector but it could be high for smaller banks (ECB, 2017[11]; EBA, 2016[12]). In this context, the capacity of banks to issue large amount of MREL-eligible securities to investors other than households, while containing a general increase in funding costs, may depend on improving banks’ ability to sell these securities to international investors.

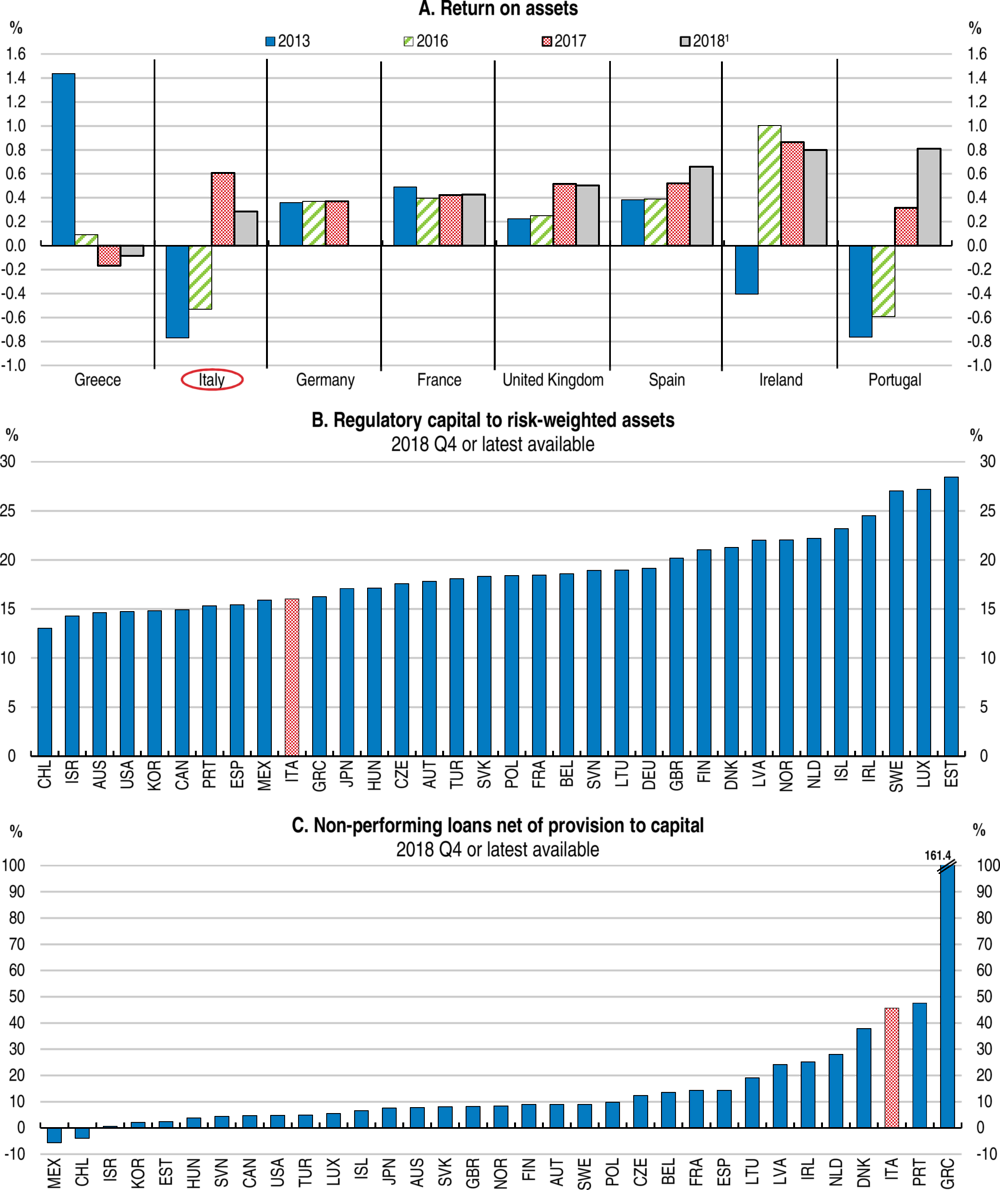

Figure 14. Banks’ non-performing loans to non-financial corporations have declined

Italian banks’ return on asset has markedly improved and in 2017 it was above peers in Europe, though it weakened in 2018 (Figure 15, Panel A). Banks’ capital ratios have increased and are well above regulatory thresholds (Figure 15, Panel B), though the common equity tier 1 ratio of Italy’s banking system decreased by 60 basis points between the late-2017 and the mid-2018. The latest EU-wide stress tests indicate Italian systemic banks could withstand severe economic shocks. Declining NPLs on banks’ balance sheets, and increased provisioning and capital have reduced the ratio of NPLs (net of provisions) to capital by more than 40 percentage points since 2016 to less than 50% (Figure 15, Panel C), though it remains large.

Despite this progress, banks still faces challenges. The banking sector is still downsizing and total bank assets declined by about 5% (EUR 200 billion) over 2017-2018. Profitability though improving remains low. In 2019, renewed tensions in the government debt market (if they were to materialise) and the slow-down in the economic recovery could weigh on it. Banks are aware of these challenges and are implementing reorganisation strategies aiming at improving efficiency. As part of these reorganisation strategies, the number of banking sector employees relative to the population has continued declining and in 2017 it was 30% below the EU average (against 26% in 2015). However, though the number of bank branches relative to the population has also decreased, it is still the third highest in the EU (and 62% above the EU average). Bank branches are small, employing about 10 people on average – 63% below the EU average. Continuing banks’ reorganisation strategies is key to lowering operating costs and improving profitability durably.

The reduction in non-performing loans have been uneven across banks. Improvements have been slower for small and medium-sized banks. The reform of cooperative and mutual banks, which requires that the largest cooperative banks turn into joint-stock companies and that mutual banks consolidate or join an Institutional Protection Scheme (a closely integrated network of mutual banks) – is still to be fully implemented. Two cooperative banks that had to turn into joint stock companies did not comply (one case was deferred to the European Court of Justice). About 230 mutual banks are expected to consolidate into 3 new banking groups. One of them started operations in early 2019. Two of them will be significant banking groups and as such will fall under supervision of the Single Supervision Mechanism and be subject to an asset quality review in 2019. Fully implementing the reforms of cooperative and mutual banks will strengthen smaller banks and help allay concerns over their viability.

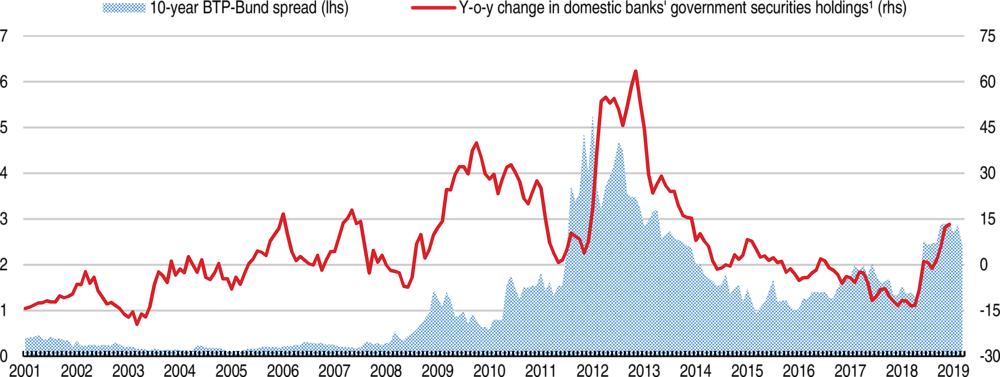

The health of Italian banks’ balance sheets remains closely linked to risks around public finances through public finances’ effects on sovereign bond yields and sovereign ratings. Italian banks have often acted as shock absorbers in the Italian sovereign bond market, buying sovereign bonds as yields rose (Figure 16). The surge in Italian sovereign yields in mid-2018 fits this pattern, with banks’ holding of Italian sovereign bonds rising by 0.7 percentage points compared with late 2017 to 9.5% of total assets. Large and sustained increases in sovereign bond yields can negatively impact banks through three main channels. First, higher government bond yields generally result in higher interest rates on deposits and yields on new bond issues, raising banks’ funding costs. Second, an increase in sovereign bond yields reduces the value of eligible collateral for Eurosystem refinancing operations, reducing banks’ liquidity. Third, the drop in government bonds’ prices valued at fair value reduces capital ratios (Bank of Italy, 2018[3]).

Figure 15. Banks’ health has improved but risks remain

1. Data for 2018 refer to either Q1 (United Kingdom), Q2 (France and Italy) or Q3 (Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain), depending on data availability.

Source: IMF Financial Soundness Indicators database.

While the larger banks appear sufficiently robust to withstand significant pressures from higher government bond yields, it may be more difficult for some smaller banks as government bonds account for a larger share of their assets. As at June 2018, the share in total assets of Italian sovereign bonds priced at fair value was 11.3% for less significant banks and 4.7% for significant banks. The Bank of Italy’s simulations suggest that an upward shift in the sovereign yield curve by 100 basis points would reduce the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio by 90 points for less significant banks and 40 points for significant ones (Bank of Italy, 2018[3]).

In the context of banks’ low equity prices, if government bond spreads were to rise durably, restoring capital ratios through recapitalisation operations would be expensive. This could lead to a feedback mechanism as banks’ losses and higher funding costs, engendered by higher government bond yields, might induce banks to reduce the supply of credit and increase lending rates, thus further slowing economic activity and undermining government revenues. Bofondi, Carpinelli and Sette (2017[14]) show that a similar process was at work during the 2011 European sovereign crisis, as Italian banks reduced credit supply – mostly because of an increase in funding costs – leading to a shortage of bank credit. Such a process, if protracted, could weaken the economy and lower confidence in the banking system, imperilling financial stability.

Figure 16. Italian banks have acted as countercyclical investors in Italian sovereign bonds

Percentage

1. Data refer to the "Deposit-taking corporations, except the central bank" sector (S122, as defined by the System of National Accounts 2008) and the "Cassa Depositi e Prestiti".

Source: OECD calculations based on Thomson Reuters and Bank of Italy.

Past recommendations on the financial sector

|

Past Survey Recommendations (Key recommendations of the 2017 Survey are in bold) |

Actions taken since 2017 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Set gradual, credible and bank-specific targets to reduce banks' non-performing loans (NPLs) consistently with recent ECB's Draft Guidelines. When banks deviate from targets, bank supervisor should require remedial actions such as additional capital requirements, sales of assets, suspension of dividend payments, and reduction of staff costs. |

NPLs have fallen following pro-active, robust and intrusive regulation and supervision. In March 2018, the four significant banks submitted updated NPL-reduction plans for 2018-2020, and, by the end of 2018, the less significant banks with high NPLs will have to submit plans for reducing NPLs. |

|

Continue to develop the secondary market for NPLs. |

A secondary market for NPLs has taken off with the participation of foreign and domestic investors. Banks and other financial institutions made large sales of NPLs into the secondary market in 2017 and first half of 2018, leading the stock of banks’ non-performing loans to decline. |

|

Use debt-equity swaps more frequently by allowing for cram down of creditors. |

No progress. The ongoing reform of the bankruptcy law should address this issue. |

|

Set clear guidelines for the valuation of collateral. |

The Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) issued guidelines for significant institutions in March 2017 and the Bank of Italy issued guidelines for less significant institutions in January 2018, for the treatment of NPLs, including collateral valuation. |

Improving well-being and boosting growth requires credible fiscal policies and ambitious structural reforms

Italy faces the double challenge of raising short and long-term growth and strengthening social inclusion and well-being, while at the same time reducing the high debt-to-GDP ratio to a more prudent level. Meeting these challenges requires a comprehensive reform programme spanning multiple policy areas – including employment and social policy, entrepreneurship, innovation and education, public administration and environmental management – while shifting government spending from current to capital expenditure and putting the public debt ratio on a gradual but steady downward path.

High government debt is a source of risks and limits fiscal policy choices

Italy’s government debt-to-GDP ratio is the third highest in the OECD, after Japan and Greece. Government borrowing costs rose sharply in 2018 following policy announcements concerning the planned large increase in the budget deficit – significantly deviating from EU fiscal rules – and policy choices partially reversing previous reforms, especially on pensions and the labour market. The 10-year sovereign yields reached over 3% in 2018 (1.5 percentage point above the level in early 2018) (Figure 16), far above peers.

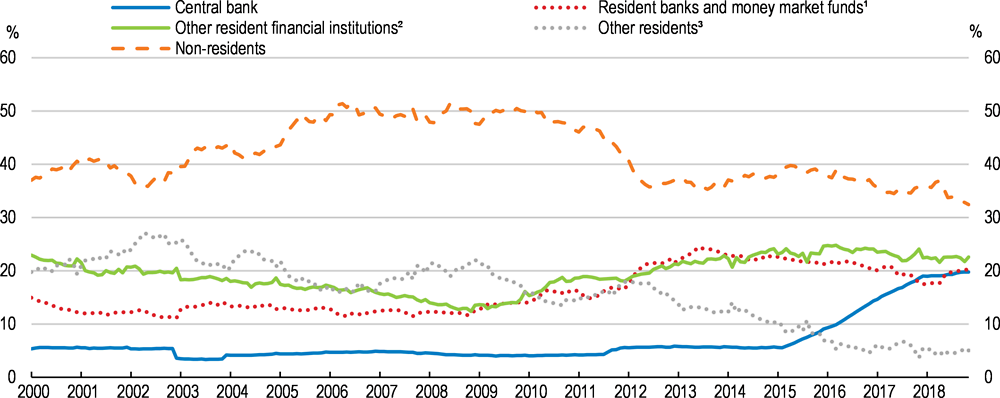

The high debt-to-GDP ratio leaves Italy vulnerable to increases in interest rates. In 2019, the government expects to issue debt securities for about EUR 380 billion, similar to 2018, and consisting of EUR 345 billion of redemptions and the rest of additional issues. The ECB’s quantitative easing (QE) policy has facilitated public debt refinancing and the share of the Italy’s sovereign debt securities held by the Bank of Italy rose from about 5% to nearly 20%, while that held by retail investors dropped to just 5% (Figure 17). In 2016, the central bank bought on the secondary market the equivalent of around 45% of the new medium- and long-term issues. In 2018, this share will fall to 24% and in 2019 it is expected drop to 9.5% as the ECB’s net purchases will fall to zero. The tapering of QE in 2019 means that the market will have to absorb larger shares of debt securities, which could put upward pressure on sovereign bond yields.

Figure 17. The ownership of government debt securities has changed significantly

Share of total general government debt securities

1. This category corresponds to the "Deposit-taking corporations, except the central bank" sector (S122) and the "Money market funds" sector (S123), as defined by the System of National Accounts 2008 (2008 SNA).

2. This category corresponds to the following sectors (as defined by the 2008 SNA): "Non-money market funds" (S124); "Other financial intermediaries, except insurance corporations and pension funds" (S125); "Financial auxiliaries" (S126); "Captive financial institutions and money lenders" (S127); "Insurance corporations" (S128); and "Pension funds" (S129).

3. This category corresponds to the following sectors (as defined by the 2008 SNA): "Non-financial corporations" (S11); "Households" (S14); and "Non-profit institutions serving households" (S15).

Source: Bank of Italy.

Markets have proved highly sensitive to uncoordinated fiscal policy announcements since mid-2018 and rising tensions with the European Commission, leading to spikes in bond yields. The 10-year government bond yield dropped by 90 basis points in December 2018 as tensions between the European Commission and the government over fiscal policy abated. The agreement on the 2019 Budget has stopped the opening of an excessive deficit procedure against Italy. Keeping clear communication on fiscal policy choices and a constructive and open-minded dialogue with the European Commission is key to maintaining investors’ confidence and avoiding drastic increases in bond yields, increasing further debt servicing costs and imperilling debt sustainability.

Italian public debt is currently just above the thresholds for investment grade of several major ratings agencies. On current OECD projections, the public debt ratio will cease to decline and rise to 134% of GDP on a Maastricht basis over the next two years. In addition, as in other countries, Italy faces over the medium-long run significant increases in public expenditure due to ageing population. The decision to partially reverse the 2012 pension reform by creating a new early retirement scheme (though only for the 2019-2021 period) will raise pension costs in the short-term, as well as in the longer-term if the new early retirement scheme is not actuarially fair. This may endanger the sustainability of the pension system and worsen intergenerational equity as discussed in the thematic chapter. Closing this new temporary early retirement scheme and ensuring that actuarial fairness is maintained also by keeping the link between retirement age and life expectancy are key to dealing with ageing population and ensuring the sustainability of the pension system.

All these factors underline that fiscal policy is vulnerable to changes in interest rates limiting fiscal policy choices to boost growth and pursue social goals. Without sustainable fiscal policy, the room for the public sector to enhance infrastructure, provide benefits and help the poor will inevitably narrow. A medium-term plan to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio is a prerequisite to improve fiscal credibility and reduce the large risk premium on government borrowing. This should be based on the following:

Steadily raising the primary surplus to above 2% would help to put the debt-to-GDP ratio on a stronger downward path (see next section). Lower borrowing costs and improved confidence would likely offset the dampening effect on activity.

The advice of the independent Italian Parliamentary Budget Office should help to frame policy and to ensure forecasts are realistic. Designing budgets within the EU Growth and Stability Pact, which should be implemented in a pragmatic way, would help to strengthen credibility by providing an anchor to fiscal policy.

Incorporating thorough and effective spending reviews in the annual budget, as the 2016 reform of the budget making process allows, would help to develop a culture of performance in line ministries, reallocate spending towards most effective programmes and curtail current spending growth.

Structural reforms are needed to strengthen social inclusion and boost growth

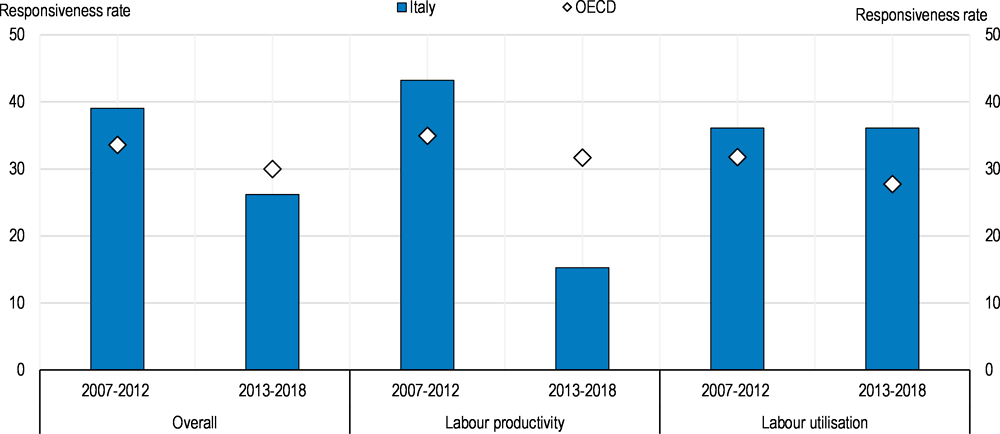

The numerous and long-standing challenges Italy faces require reforms spanning several policy areas. Developing a multi-year reform package is a prerequisite to address these challenges and restore confidence in the reforming capacity of the country. Reforms undertaken in recent years have started to address some of these challenges. These include the Good School (Buona Scuola) reform (increasing resources and autonomy for schools and introducing school-to-work experience for students), the pension reform (linking retirement age with life expectancy), the Industry 4.0 plan (boosting investment and innovation), the public administration reform, the Jobs Act and the national antipoverty programme. Overall, reforms over the past 10 years – as gauged by the OECD reform responsiveness index – have focused on labour market issues (Figure 18). This reflects the right priority of tackling the long-standing challenges of the Italian labour market as highlighted by the low employment rate and job quality, although recent decisions and a Constitutional Court pronouncement have partially reversed these reforms. Going forward, it will be important not to reverse such reforms further while also boosting productivity growth by increasing competition in markets that are still protected, such as local public services, raising innovation and business dynamics, enhancing public administration efficiency and reducing administrative barriers to entrepreneurship and business dynamism.

Figure 18. Reforms in the past 5 years have focused on labour issues

Reform responsiveness rate

Note: The responsiveness rate is calculated as the average ratio of reforms undertaken to reform opportunities.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2018) Going for Growth.

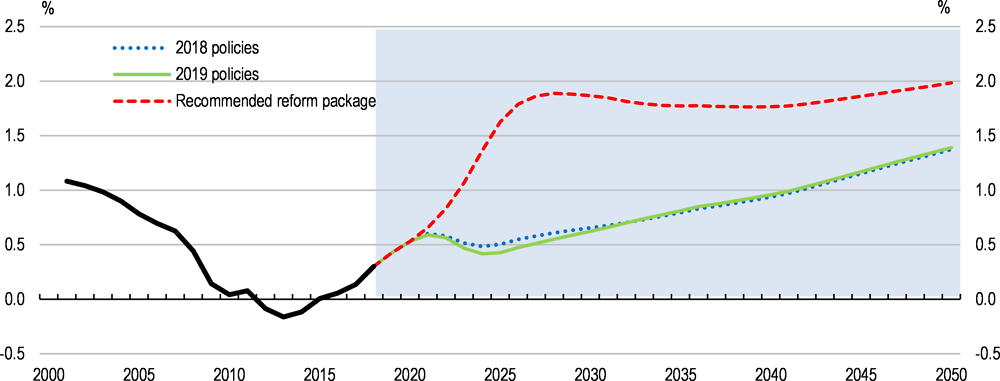

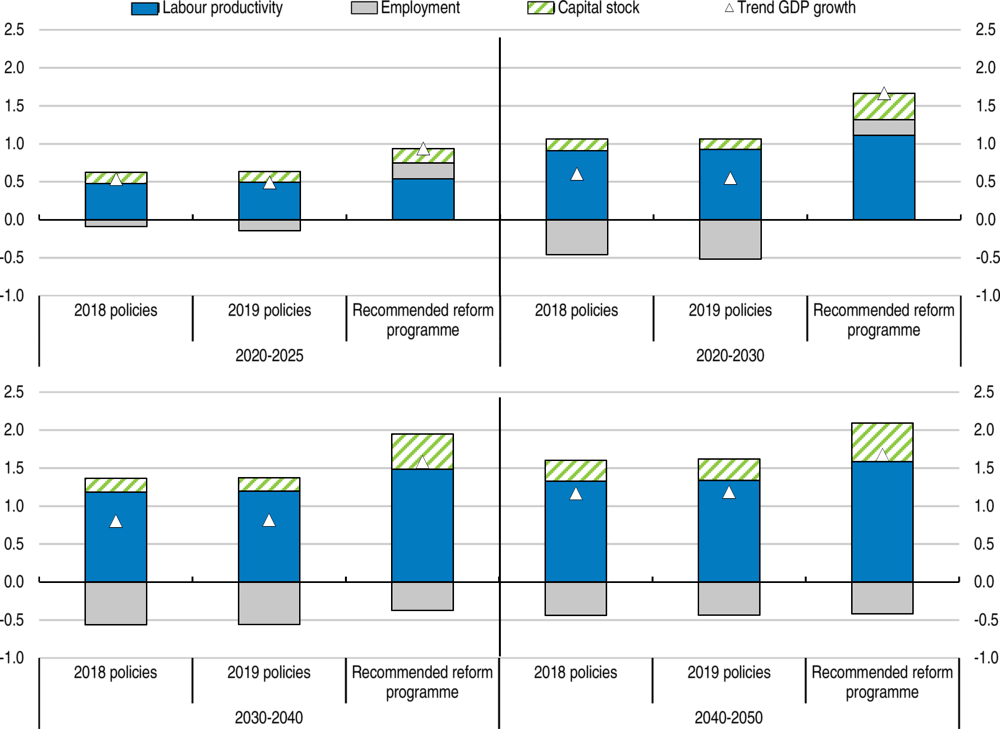

OECD estimates suggests the reform package proposed in this Survey would lift growth and reduce poverty by increasing employment, raising productivity and strengthening incentives to invest (Figure 20 and Figure 21). By 2030, trend GDP growth would increase from 0.6% under current policies to above 1.7% under the reform package recommended below (Figure 20 and Table 4). Between the end of the 2020s and 2040, trend growth will decline mainly because of ageing, which will continue to shrink the working age population. Increasing productivity growth is therefore key to offsetting the large negative effect of demographics and to boost growth.

The proposed reform package is wide ranging. Among the proposed reforms, the strengthening of the effectiveness and efficiency of public administration and the justice system, the expansion of active labour market programmes, better-targeted social benefits that reduce inequality and the tax wedge would bring the greatest benefits. Those concerning the reform of public administration and justice system would have the largest impact on GDP growth as they are key to strengthening the rule of law, but would also be the most challenging to implement. However, the new early retirement scheme, if not actuarially neutral, and the temporary break (up to 2026) of the link between the updates of early retirement contribution requirements and developments in life expectancy, as done by the 2019 budget, will offset some of the benefits of the proposed reforms (Table 4).

The current government has expressed its intention to continue the process of reforming the public administration that previous governments have started. This is welcome, but at the same time, the government should not underestimate the challenges and degree of commitment needed to achieve results. As underlined by a recent white book on public administration reforms that has collected suggestions from a wide range of experts and civil society (ForumPA, 2018[15]), public administration reforms should enhance transparency and accountability and focus on the following:

Reducing the number of laws and regulations and more extensive use of single codes and manuals, accompanied by more reliance on clear outcomes and targets rather than procedural rules.

Building platforms and networks of experts for the identification and dissemination of best practices and further promoting yardstick competition at central and sub-national levels; those public administration agencies at central and local levels that repeatedly fail to reach minimum standards or agreed targets should undergo a reorganisation process involving if necessary management changes and requalification of personnel.

Increasing efforts to digitalise the public administration adopting a horizontal approach following the positive example of the Digital Transformation Team (see Box 2); to ensure continuity and a strong mandate, the government should turn the Digital Transformation Team into a permanent body in the Prime Minister’s Office rather than disbanding it as currently planned.

More effective human resource management through hiring procedures and allocation of staff based on skills needed in each job vacancy, more training and learning opportunities at different stages of careers, and raising accountability by clearly identifying who is responsible for what.

The justice system plays a crucial role in upholding the rule of law and enhancing mutual trust. Reforms have been focussing on the use of digital technologies, including the e-trial (allowing parties to submit documents in electronic forms), increasing court specialisation, improving administrative procedures to increase courts’ efficiency and addressing staffing shortages. The Criminal Procedural Code was reformed in 2017. Following these reforms, which are still ongoing, Italy’s justice system has reduced the sizeable backlog of unresolved administrative and civil cases. The time needed to resolve litigious civil and commercial cases has been declining since 2014, though it is still among the longest in the EU. Cases reaching second and third instances courts are exceptionally long. While public spending on the justice system is near the European average, the number of judges is comparatively low and residents have less confidence in the justice system than in most EU countries (European Commission, 2018[16]).

Italy should continue to reform and modernise its justice system. Given the complexity of the justice system, the reform effort will have to be sustained over years and results will appear gradually. The government’s intention to reform the civil procedural code and streamline civil trials based on case-management system (Ministry of Justice, 2019) is welcome. More could be done to promote alternative resolution dispute methods, which are still too little used in Italy, especially in labour, civil and commercial disputes.

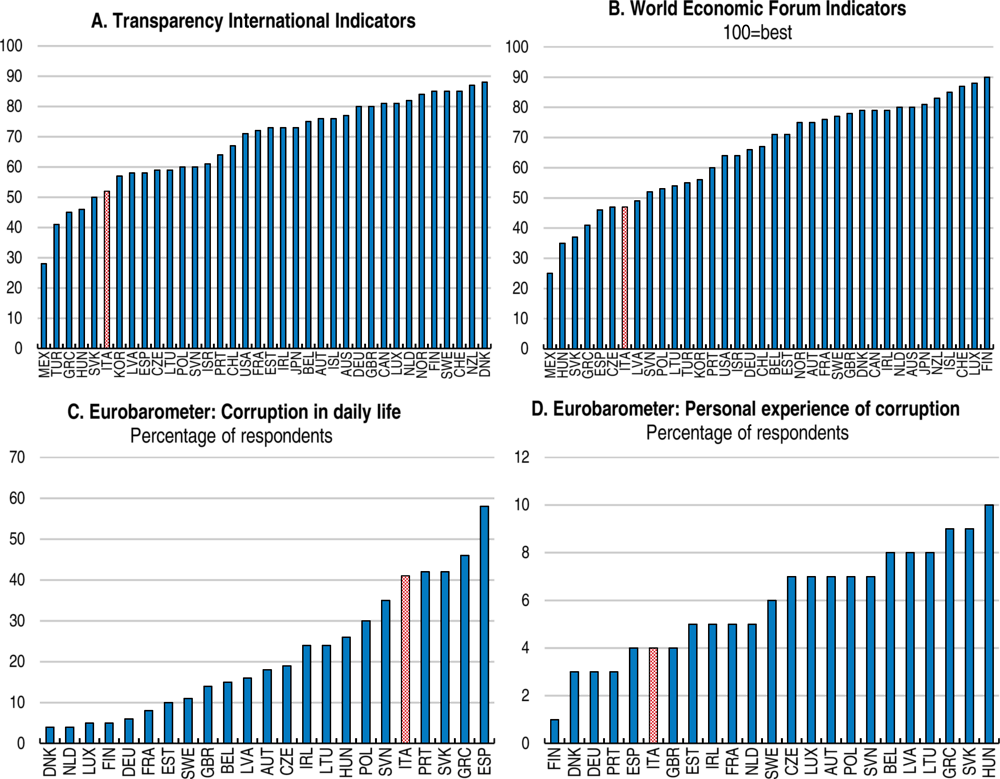

Public administration reforms must go hand-in-hand with continued efforts to fight corruption. The legislative framework on anti-corruption has evolved remarkably since the systematic intervention in 2012, which established a path for reforms that are still ongoing. The Anti-corruption Authority (ANAC), which is independent from the government, was established in 2014. Since then, it has gradually gained a prominent role by offering advice to central and sub-national governments and agencies on adopting and strengthening corruption-preventing measures, managing the electronic platform to collect information from whistle-blowers and issuing guidelines and regulations on public procurement contracts. ANAC can apply administrative sanctions to public officials not complying with the obligation of adopting anti-corruption plans or codes of conduct. Through its experience with hosting the Expo 2015, Italy has developed with the OECD a model to manage large and ad hoc procurements while minimising corruption risks (United Nations, 2009[17]). Besides having significant powers regarding transparency, integrity and anti-corruption plans, ANAC is responsible for issuing the implementing regulation of the 2016 public procurement code and overseeing public procurement and contracts

The 2016 public procurement code is innovative and well-designed. The new code has enhanced transparency of contracting authorities and contracting entities relating to public procurement. The code sets standard timeframes and conditions for participation in public tenders, awarding tender criteria, legal recourse and appeal processes. The code also establishes a register for members of public-tender boards, which is expected to enter into force in 2019. To enhance general transparency and integrity of procurement, ANAC collects, analyses and publishes all relevant procurement data.

While some aspects of the Public Procurement Code may need to be streamlined, the role and power of ANAC should be protected. The Code’s implementation delays are not attributable to ANAC. They are instead due to the novel aspects of the Code aiming at lowering corruption risks, and enhancing competition in bidding processes and project quality. However, these innovative aspects also require some time for all stakeholders to understand them and to provide feedback to ANAC before it issues implementing regulations. To expedite the implementation of the new Code, the government should issue the implementing decree that sets the criteria to identify the qualifying contracting authorities for public procurement contracts on which ANAC already provided advice. The government should follow up on ANAC’s Triannual Plan to Prevent Corruption (updated annually), as it contains useful recommendations to reduce corruption risks in different policy areas at sub-national and central levels. The latest plan focuses on revenue agencies, use of European funds and waste management (ANAC, 2018). The government should also stagger the appointment of the ANAC’s board members to avoid replacing all board members at the same time.

The reforms undertaken in the past ten years to fight corruption and improve public procurement go in the right direction and show the seriousness and determination of Italy’s successive governments on this issue. Despite this, indexes of perceived corruption are still generally high compared to other countries (Figure 19). This could be due to two not mutually exclusive reasons. First, the reforms of the past ten years have not yet produced the expected benefits as implementation and following due processes take time. Second, perception indexes may not adequately measure corruption. For instance, according to the Eurobarometer survey, Italy has a high percentage of respondents reporting a high level of corruption in daily life but at the same time the percentage of respondents reporting to have personal experience of corruption is low.

Measuring corruption, and more generally the efficiency of the public administration, on a more objective basis is key to designing and implementing effective anti-corruption measures and enhance trust in the government. To this end, Italy is actively participating in different international initiatives, at the G20, UN and the OECD, aiming at developing indicators to measure corruption and progress in reducing it more objectively. The OECD has been working on open data, quantitative analysis and the use of data analytics to combat fraud, waste and abuse, and to promote public integrity and improved government performance (High-Level Advisory Group, 2017[18]).

Past recommendations on public sector efficiency

|

Past Survey Recommendations |

Actions taken since 2017 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Approve and fully implement the public administration reform to open up to competition local public services. |

Public administration reform has been approved and implemented. The opening to competition of some local public services is still. The reform of local state owned enterprises is ongoing but has been delayed. |

|

Ensure that legislation is clear, unambiguous and supported by improved public administration, including through reduced use of emergency decrees. |

The use of emergency decrees has declined. The public administration reform has been approved and implemented and measures are ongoing. A Freedom of Information Act (FoIA) was approved, which establishes a general civic access: citizens are allowed to access data and documents of the Public Administration even if those are not made public. The same Decree that introduced the FoIA, sets an obligation for Public Administrations to publish their data bases. |

|

Make more extensive and better use of regulatory impact analyses, especially by engaging with stakeholders in ex-ante consultative processes. |

The anti-corruption agency (ANAC) provides guidance on various issues relating to the prevention of corruption. Its regulations have the power of soft laws. As regards whistle-blower protection in the public and private sector, ANAC has become the main channel for receiving the reports. In the public sector ANAC is not only a reporting channel, but also the governance and regulatory authority. No change on Regulatory Impact Assessment |

|

Further streamline the court system, with more specialisation where appropriate; increase the use of mediation; enhance monitoring of court performance. |

Continued judicial system reforms, although performance remains uneven, and times to resolve cases is significantly slower in southern regions. |

|

Consider establishing a Productivity Commission with the mandate to provide advice to the government on matters related to productivity, promote public understanding of reforms, and engage in a dialogue with stakeholders. |

No progress. |

|

Reducing corruption and improving trust must remain a priority. For this, the new anti-corruption agency ANAC needs stability and continuity as well as support at all political levels. |

ANAC continues to operate and has gained a prominent role in corruption prevention activities. It as an importation in public procurement procedures and responsible for issuing implementing regulation concerning the 2016 public procurement code. The code has yet to be implemented in full. In 2018 the government put forward and the parliament approved a new law (Corruption-Sweeping Law, “Spazzacorrotti”) lengthening prison sentences for corruption convictions, eliminating the statute of limitations after a first degree judgment (for all judicial cases not just for corruption), allowing for undercover agents in corruption investigations and setting a measure of debarment (so called Daspo) for both public officials and private individuals, as well as companies, convicted for corruption, which will be banned from contracting with public administrations. The reform of the Criminal Codes, entered into force in August 2017 includes a reform of the time limitation regime, thus enhancing the capability of the criminal system to fight corruption. As for the Civil Code, an important step forward has been made with the introduction of innovative provisions regarding corruption in the private sector. |

|

Reduce public ownership, especially in TV media, transport and energy utilities, and local public services. Privatise and liberalise energy and transport sectors. Complete framework for regulation of water and other local public services, ensuring regulatory independence. Introduce national oversight of regional regulatory competences (e.g. retailing, land-use planning). |

Privatisation programme has made little progress. The latest large privatisation concerns the disinvestment of 46.6% equity stake in the air traffic controller (ENAV) in 2016. A 2018 decree (Mille Proroghe decree) postponed the price liberalisation for gas and electricity by one year to 1st July 2020. |

Figure 19. Indicators of perception of corruption

Note: “Transparency International indicators” refers to the average of five sub-indicators available for all OECD countries in the “Corruption Perception Index”; “World Economic Forum indicators” refers to the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey; “Eurobarometer: corruption in daily life” refers to the share of respondents who agreed with the statement “You are personally affected by corruption in your daily life”; “Eurobarometer: experience of corruption” refers to the share of respondents who answered positively to the question “In the last 12 months have you experienced or witnessed any case of corruption?”.

Source: Transparency International; World Economic Forum; and Eurobarometer.

Figure 20. Reforms to raise participation and improve the business climate would lift Italy’s growth prospects

Trend annual real GDP growth rate, alternative policy scenarios

Note: Policy scenarios are described in Table 4.

Source: OECD calculations based on Y. Guillemette, et al. (2017), "A revised approach to productivity convergence in long-term scenarios", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1385, OECD Publishing, Paris.; M. Cavalleri, and Y. Guillemette (2017), "A revised approach to trend employment projections in long-term scenarios", and OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1384, OECD Publishing, Paris.; Y. Guillemette, A. de Mauro and D. Turner (2018), “Saving, Investment, Capital Stock and Current Account Projections in Long-Term Scenarios”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers.

Table 4. Effects of reforms on real GDP growth

|

|

2025 |

2030 |

2040 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

% difference in level of real GDP, relative to 2018 policies: |

|||

|

2019 policies |

|

|

|

|

Pension reform reduce effective retirement age by 3 years in 2021, declining to 1.4 years in 2024, and by 0.8 years from 2032 |

-0.3% |

-0.4% |

-0.3% |

|

Citizen’s Income reduces inequality by 0.81 points on the Gini coefficient and increase the labour tax wedge on singles at 100% of the average wage by 2.2 percentage points. |

-0.2% |

0.9% |

2.1% |

|

Active labour market programme spending increased by 25% per unemployed person in 2025, then returns to baseline by 2025 |

0.1% |

0.0% |

-0.1% |

|

Overall effect |

-0.2% |

-0.5% |

-0.4% |

|

Recommended policy package |

|||

|

Guaranteed minimum income scheme, in-work benefits, and tax and social security contribution reforms reduce inequality and the tax wedge |

0.9% |

2.4% |

3.8% |

|

Active labour market programme spending increased by 9% points per unemployed person in 2021 then by an additional 37% points by 2025 to be 130% above baseline |

0.9% |

3.7% |

6.3% |

|

R&D spending rises from 1.3% of GDP to 2.0% of GDP by 2025, to near the average of other G7 countries |

0.0% |

0.1% |

0.6% |

|

Family benefits in-kind increase by 40% by 2030, to reach OECD average relative to GDP |

0.0% |

0.2% |

0.5% |

|

Reform of public administration and justice system (rule of law rises gradually to close half of Italy's gap with the OECD average by 2030) |

0.2% |

1.1% |

4.4% |

|

Overall effect |

2.0% |

7.6% |

16.2% |

Note: Reduced tax expenditure and tax evasion, increased and more effective public investment and more efficient public procurement and asset management, presented in the fiscal impact table, is not included in these estimates of the effects of the recommended reform package on real GDP growth.

Source: OECD calculations.

Figure 21. The recommended reform package would help to offset the growth effects of ageing and the decline in the working age population

GDP growth, annual average and contributions

Note: Growth rates and contributions are the average of annual log changes.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Economic Outlook 104, including more recent information; and Guillemette, Y. and D. Turner (2018), "The Long View: Scenarios for the World Economy to 2060", OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Box 2. Italy’s Digital Transformation Team

Italy’s Digital Transformation Team is an agency created in 2016 on a temporary basis to accelerate the implementation of the government’s digital agenda. In addition to completing the long overdue three-year Plan for Digital Transformation, the Team has developed digital platforms to simplify interactions with the public administration concerning the digital identity, the national resident population register, the electronic identity card and digital payments. In addition the Digital Transformation Team has offered its expertise to various municipalities, and public administration bodies, including the Court of Auditors, the Revenue Agency and the National Social Security Institute on specific projects. The Team is scheduled to be disbanded in 2019.

Figure 22. The recommended reform package would improve debt sustainability

Projected public debt under various reform and growth scenarios, percent of GDP

Table 5. Assumptions of recommended reform package debt sustainability scenarios

|

|

2020 |

2025 |

2030 |

2035 |

2040 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2019 policies, OECD projections |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real GDP growth |

%, annual |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

Primary fiscal balance |

% GDP |

0.6 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

GDP deflator growth |

%, annual |

1.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Implicit effective nominal interest rate |

% |

2.9 |

4.0 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

|

Spread between effective interest rate and risk-free rate |

bps |

219 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

|

Recommended reform package |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real GDP growth |

%, annual |

0.5 |

1.3 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

|

Primary fiscal balance |

% GDP |

0.6 |

1.8 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

|

GDP deflator growth |

%, annual |

1.4 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Implicit effective nominal interest rate |

% |

2.9 |

4.0 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

|

Spread between effective interest rate and risk-free rate |

bps |

219 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

|

Recommended reform package + lower interest rates (spread declines to 100) |

|

|

|

|||

|

Real GDP growth |

%, annual |

0.5 |

1.3 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

|

Primary fiscal balance |

% GDP |

0.6 |

1.8 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

|

GDP deflator growth |

%, annual |

1.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Implicit effective nominal interest rate |

% |

2.9 |

3.5 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

|

Spread between effective interest rate and risk-free rate |

bps |

219 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Recommended reform package + smaller primary surplus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real GDP growth |

%, annual |

0.5 |

1.3 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

|

Primary fiscal balance |

% GDP |

0.6 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

GDP deflator growth |

%, annual |

1.4 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Implicit effective nominal interest rate |

% |

2.9 |

4.0 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

|

Spread between effective interest rate and risk-free rate |

bps |

219 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

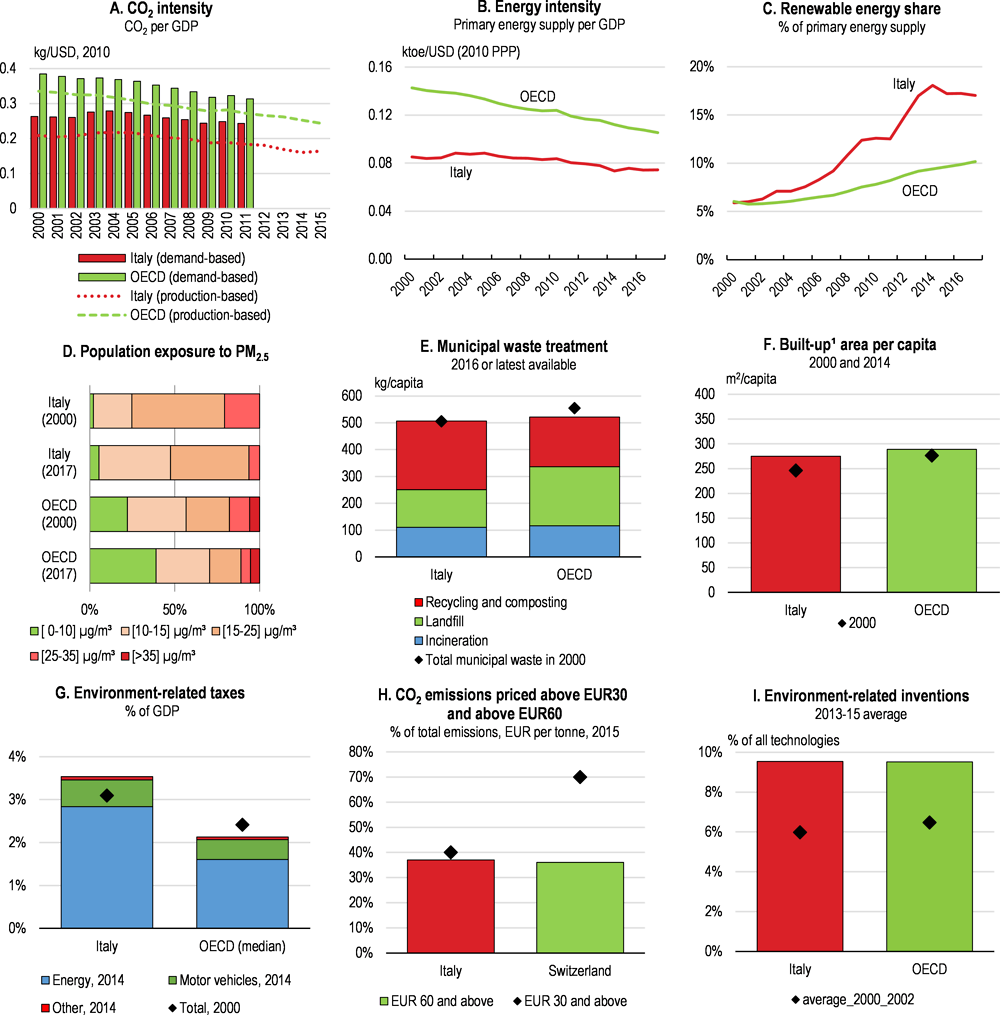

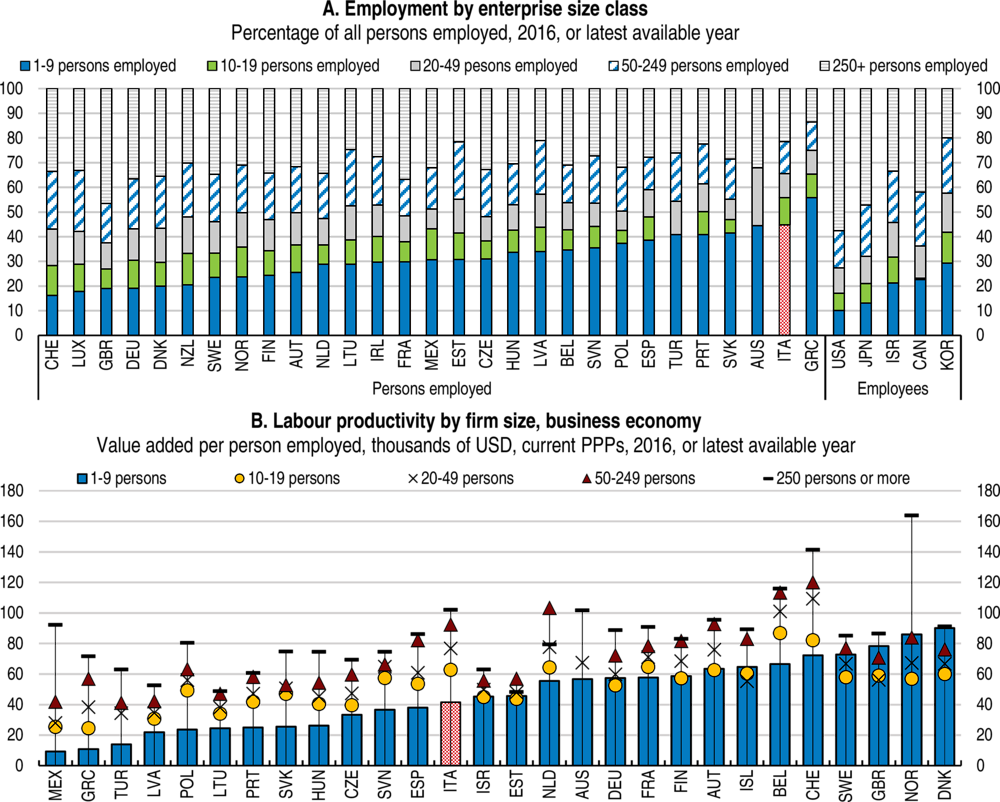

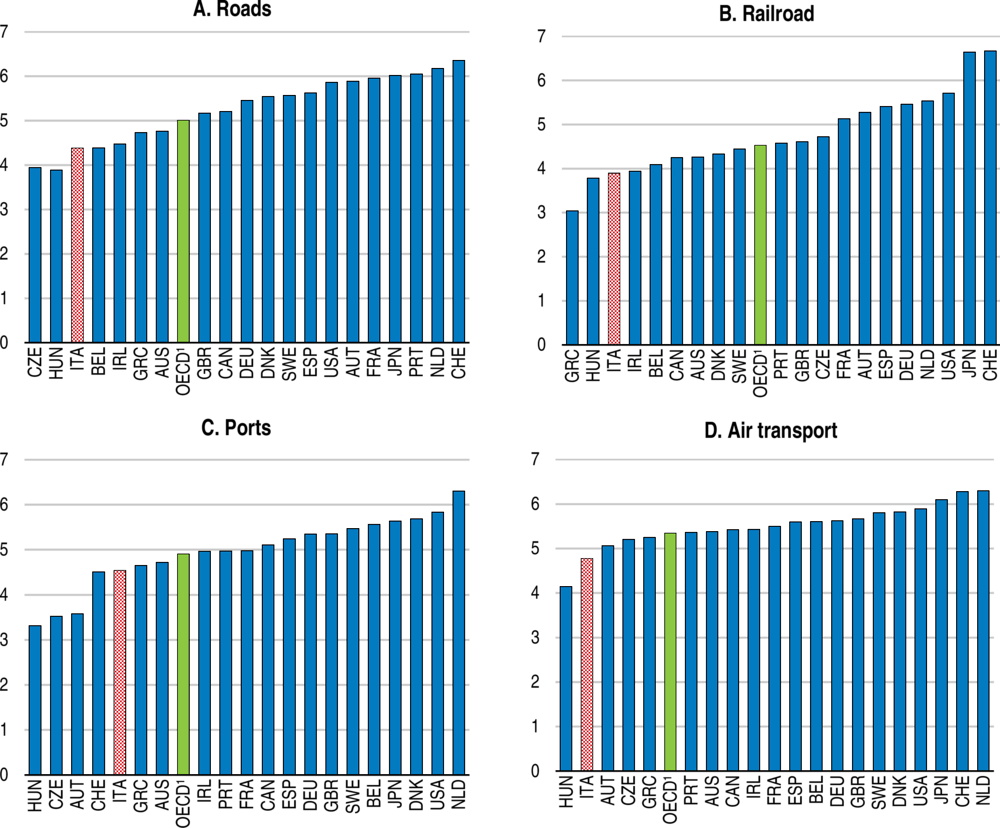

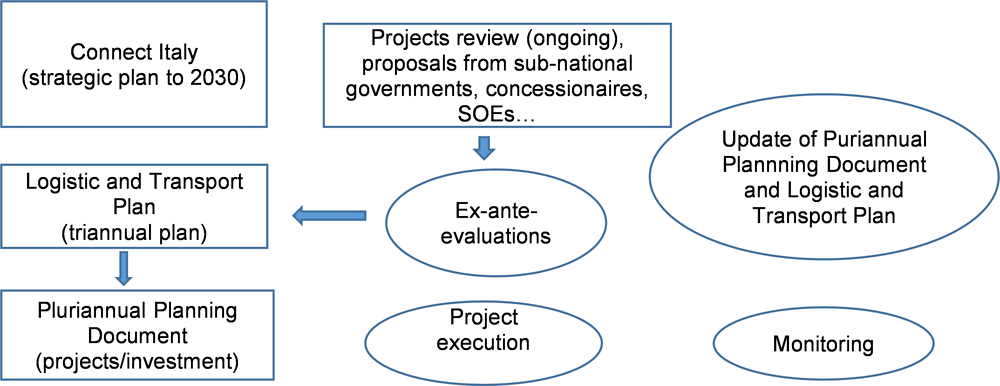

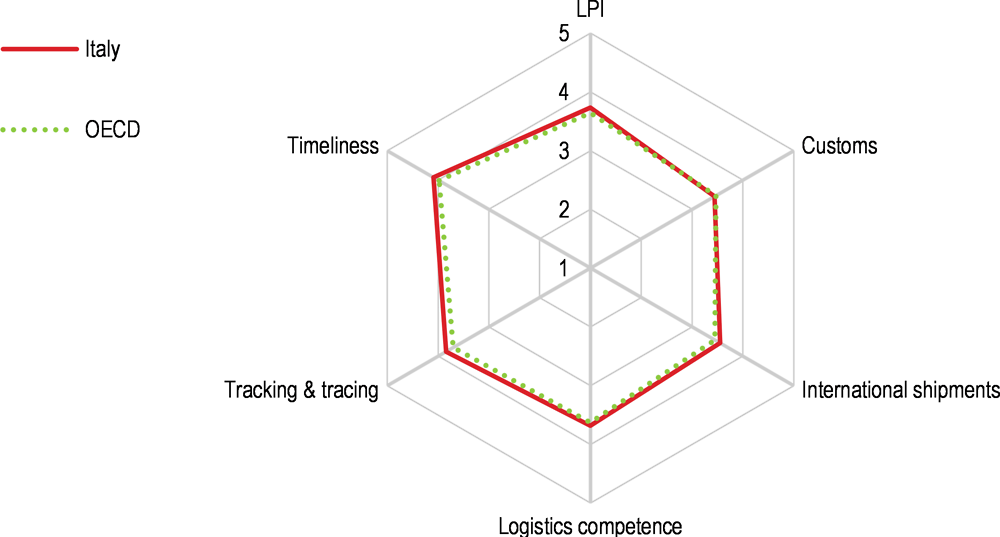

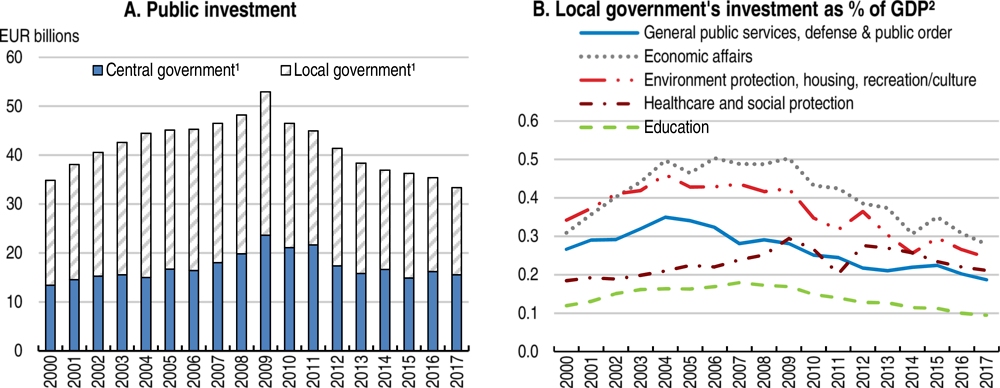

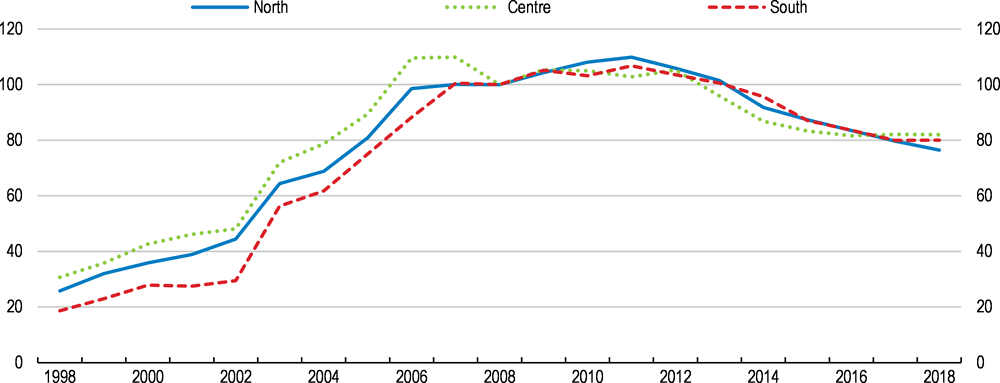

150 |