Alberto González Pandiella

OECD

Alessandro Maravalle

OECD

Alberto González Pandiella

OECD

Alessandro Maravalle

OECD

Mexico has large potential to boost its productivity and attract investment from companies looking to relocate their operations to North America. It also has an historic opportunity to spread the benefits of trade throughout the country, integrate SMEs more forcefully into value chains and to create more and better value chain linkages. Nearshoring is also an opportunity to step up efforts to address and mitigate climate change. Fully realising these opportunities will require addressing long standing challenges related to transport and digital connectivity, regulations, the rule of law, renewable energy or water scarcity.

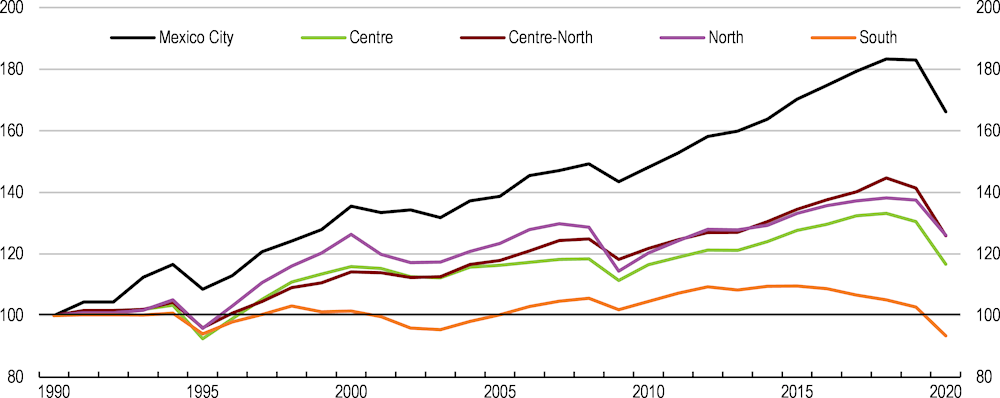

Mexico is very open to foreign trade and investment. The 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) triggered a transformation of the Mexican economy, which became deeply integrated into global value chains in manufacturing sectors such as auto or electronics, with exports as a share of GDP tripling since 1988. The modernised trade agreement in North America and the ongoing redrawing of global value chains (GVCs) are bringing substantial additional opportunities to Mexico that can help spread the benefits of trade throughout the country, beyond the Northern and Central regions, which greatly benefited from the new export opportunities brought by NAFTA, in contrast with Southern regions (Figure 3.1). Spreading the benefits of nearshoring would also avoid creating excessive agglomeration, adding to already existing difficulties to access affordable housing and public services (see chapter 5), and belts of urban poverty.

The recent upheaval of public investment aims at particularly benefiting southern states. A key infrastructure project is the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, which seeks to create a logistics hub in south-eastern Mexico by connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans through a railway system, both for cargo and passengers. It involves the improvement of ports and the creation of 10 industrial parks.

Real GDP per capita by region groupings, index, 1990 = 100

Note: Data referring to the "South" exclude Campeche, where oil production is concentrated and whose GDP-per capita does not fully reflect living standards.

Source: INEGI.

Nearshoring is also an opportunity for Mexico to take a leap forward in the fight against climate change. At a moment when global manufacturing activity increasingly seeks to decarbonize its production processes, Mexico's large and unused renewable energy resources are a remarkable competitive advantage. Shifting to low-carbon energy sources would facilitate both attracting investment and reducing Mexico’s carbon footprint. Enhancing transportation infrastructure and logistics would also reduce emissions associated with the transportation of goods. In the same vein, with companies increasingly factoring in environmental considerations when choosing their manufacturing and production locations, strengthening climate change mitigation can be another avenue to increase competitiveness by enhancing the reliability of certain inputs, such as water, and reducing operational risks for companies.

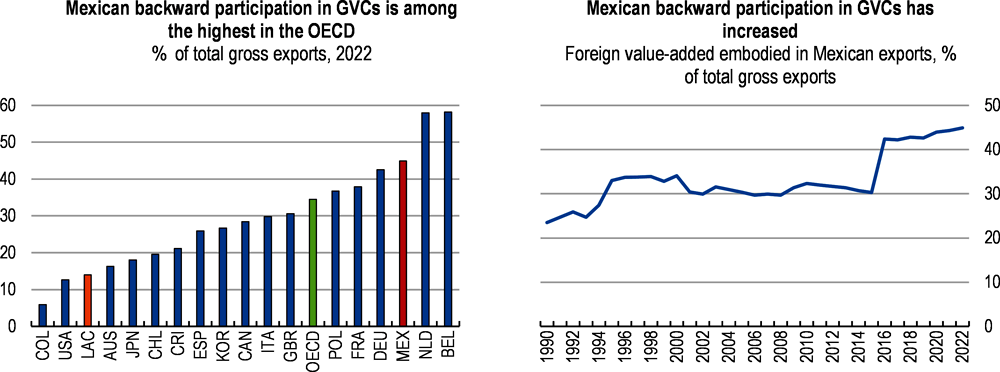

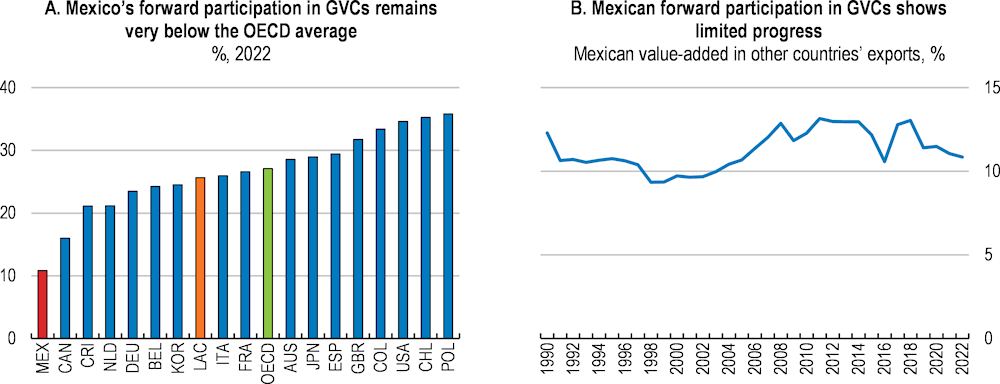

Nearshoring also holds the promise to improve supply chain linkages, shifting from low-cost assembling processes to higher value-added functions being carried out in Mexico. Mexico is well integrated into GVCs from a backward perspective (i.e. the share of foreign value added in Mexico’s gross exports is large). Such participation has been increasing overtime (Figure 3.2 and (Vidal and González Pandiella, forthcoming[1])), serving as a strong engine of exports and jobs. Conversely forward participation (i.e. the share of Mexican value added embodied in foreign countries’ exports) is low and shows more limited progress overtime (Figure 3.3).

Note: LAC is an unweighted average of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru.

Source: UNCTAD-Eora Multi-Region Input-Output tables (MRIO) (1990-2017); and estimations (2018-2022).

Note: LAC is an unweighted average of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru.

Source: UNCTAD-Eora Multi-Region Input-Output tables (MRIO) (1990-2017); and estimations (2018-2022).

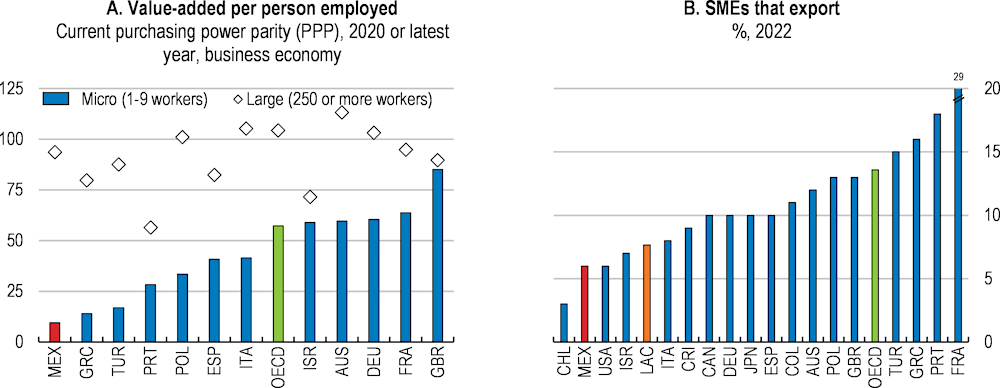

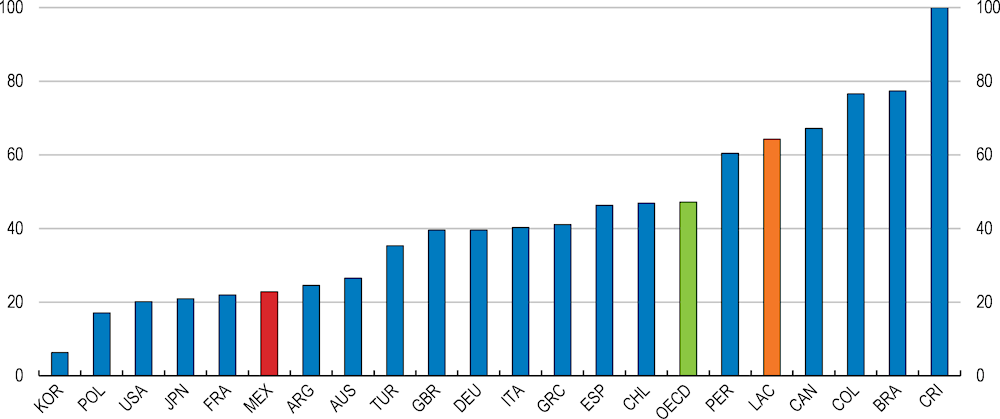

Another key challenge is to increase the participation of Mexico’s SMEs in international trade. SMEs are the backbone of the Mexican economy, representing more than 99% of the companies in the country and generating around 70% of employment. But only 5% of SMEs participate in foreign trade. A key barrier is that Mexican SMEs tend to be very small, with a high share of low productive micro-firms below 10 employees (Figure 3.4). Boosting SMEs’ productivity is essential for them to access international markets as it enables them to meet international quality standards and to offer competitive prices. A new policy package has been launched (Mano a mano, in Spanish) to support SMEs’ institutional, digital and financial inclusion. Specific programmes to promote women’s participation in trade (Mujer Exporta Mexico, in Spanish) have also been deployed.

Note: LAC is an unweighted average of Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica.

Source: OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2023.

Becoming suppliers or partners for FDI firms can help Mexican SMEs to boost their productivity and value added, as illustrated by positive experiences in some OECD countries (Box 3.1) and could act as a steppingstone for them to operate internationally more extensively. Mexico has put in place a four-stage programme to facilitate SMEs becoming local suppliers of companies growing in Mexico or relocating there. This includes diagnosis of each sector needs, putting in pace training programs targeted at SMEs, and matching processes between local SMEs and foreign firms. Strong collaboration with the private sector will be essential for the success of this initiative. Certification procedures can also facilitate SMEs becoming suppliers to larger firms. By obtaining internationally recognized certifications in areas such as product safety and quality or environmental sustainability, SMEs can demonstrate their commitment to meeting high standards and ensuring product or service reliability, making large firms more inclined to engage with them as trusted suppliers. Going through the certification process tends to be costly and lengthy. Simplifying certification procedures and providing assistance to SMEs, including financial support, can make certification procedures more accessible and increase SMEs chances of tapping into global value chains.

By bringing financing, advanced technology, and know-how to host countries, foreign direct investment can have positive spillover effects on domestic firms. These positive spillovers cannot be taken for granted and empirical evidence about them is mixed. Costa Rica is one of the few cases in which there is robust empirical evidence of positive spillovers (Alfaro-Urena et al., 2019[2]). Firms that supply foreign-owned firms have, four years after the first sale, 33% higher sales, 26% more employees, 22% more net assets, and 23% higher total input costs. Total Factor Productivity increases range from 4% to 9%. Costa Rica has put in place explicit policies to promote these linkages. Procomer, a public institution working alongside the Ministry of Trade, offers a series of services to promote linkages between local firms and multinationals firms in the country. They recruit and evaluate local potential suppliers and assess whether they are suited to become providers of foreign firms. Among other elements, they evaluate their infrastructure, production capacity, marketing or human capital and provide them with recommendations and support to upgrade performance. Procomer also facilitate exchanges between local firms and international ones through an electronic platform. Around 70% of multinationals participate in these exchanges by detailing their expectations on the products and services to be supplied, visiting potential local suppliers, carrying audits and advising about upgrades to be implemented by local firms. Beyond the traditional matchmaking between domestic SMEs and multinationals, Costa Rica has recently established additional support programmes to strengthen linkages between SMEs and large institutions in the public sector, such as the Social Security Fund or the Costa Rican Electricity company, and in new sectors, such as tourism and agriculture.

Mexico’s large size implies that the average distance of exports to ports and airports is 3500 kilometres, significantly higher than in peer countries (World Bank, 2022[3]). Improving infrastructure and logistics, including in remote areas, is therefore key to attract investment, boost productivity and would also contribute to reduce carbon emissions. Several infrastructure projects are underway to improve connectivity, including the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Maya Train, which interconnects southern states, or suburban trains in Monterrey and Mexico State.

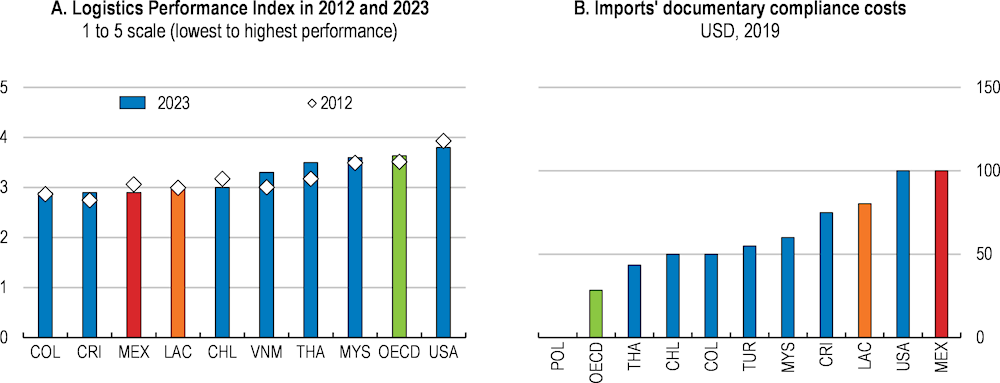

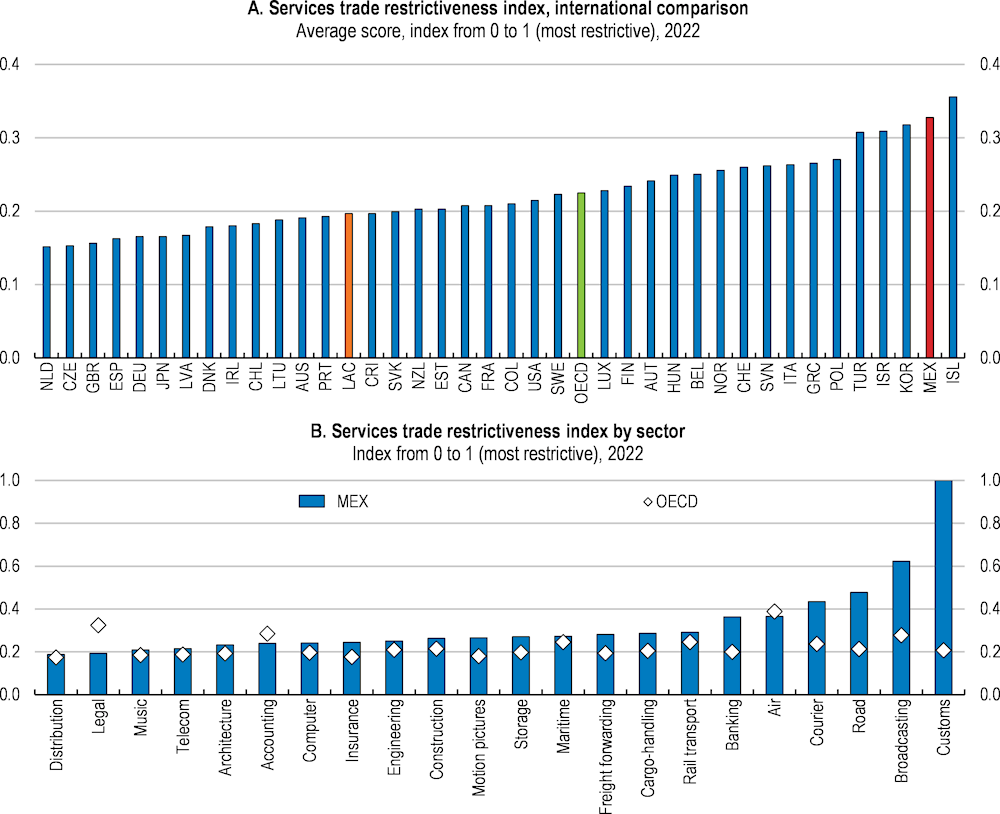

Logistic performance indexes suggest that, beyond improving infrastructure, Mexico has also room to improve the quality of logistics services (Figure 3.5), which encompasses trucking, forwarding and customs brokerage. The cost to import a container following documentary compliance is US$100 in Mexico, compared with less than US$60 in Malaysia, Turkey, and Thailand. Mexico also shows one of the highest import times spent complying with documents (18 days) and at the border (44 days), compared with only 1 and 0 days in Poland or 2 and 7 days in Turkey, respectively (World Bank, 2022[3]). Mexico performs better on the cost and time to export. According to OECD’s Trade Facilitation Indicators, Mexico has room to reduce logistics costs by making a greater use of advanced rulings and improving the availability of information, including by digital means, and appeal procedures. These are initiatives which are less demanding in terms of financing than building physical infrastructure, but the resulting payoff could be large. The existing national committee for trade facilitation, putting together relevant government agencies and the private sector, will be a valuable tool to continue moving Mexico towards OECD best practices in trade facilitation. Likewise, the ongoing cooperation with the United States through the High-Level Economic Dialogue to enhance trade facilitation and borders infrastructure can trigger a material improvement in the Northern area. Reducing existing trade barriers in logistics-related services (Figure 3.6), such as customs brokerage, road transportation, cargo handling or storage, would improve competition and reduce costs.

Note: LAC is an unweighted average of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru.

Source: World Bank Logistics Performance Index 2023.

Note: LAC is an unweighted average of Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica.

Source: OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index.

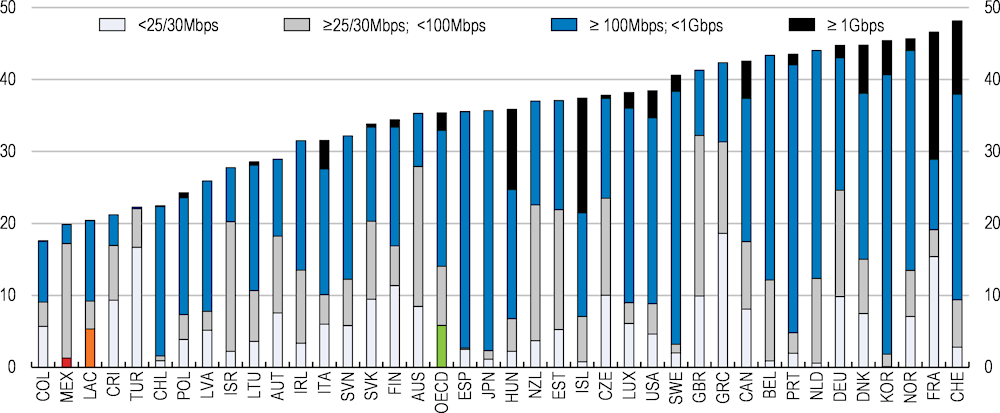

Boosting digital connectivity can also help to overcome remoteness of regions and promote participation of SMEs in international trade. About 30% of entrepreneurs do not have Internet access and rural areas and remote communities are often underserved, with limited access to high-speed internet (Figure 3.7). Access to digital infrastructure is uneven across Mexico (Figure 3.8). While there have been recent investments in digital infrastructure, investment levels in this area are still relatively low compared to other countries. Streamlining regulations would encourage higher investment. The regulatory process is complex and fragmented, with multiple government agencies and regulatory bodies involved in overseeing different aspects of the sector. Regulations tend to be overly complex with significant divergences at the local and municipal level, which is a critical obstacle to infrastructure deployment.

Fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants, by speed tiers, December 2022

Note: Mbps = megabits per second and Gbps = gigabits per second. LAC is an unweighted average of Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica.

Source: OECD Broadband Portal (database)

Digital infrastructure development index, from 0 (lowest) to 100

Note: The Digital infrastructure development index refers to coverage, access, quality, affordability, and infrastructure of data.

Source: Centro México Digital (2023), Índice de Desarrollo Digital Estatal 2023.

Mexico's ICT market is highly concentrated (OECD, 2022[4]), with one company having more than 60% of mobile subscribers. Limited competition can raise prices and slow the development of new digital infrastructure. Opening markets by favouring the entry of new provides would spur competition, promote investment, enhance access and improve quality. Southern states are likely to benefit the most from it. While the sharing of infrastructure by dominant companies is mandatory, this has not been enforced effectively, with dominant companies challenging the scope and application of the sharing rules. Maintaining an independent and well-resourced telecommunications regulator would be essential to facilitate more competition in the sector and to enforce existing regulations about infrastructure sharing. The federal administration has stopped appointing new commissioners, resulting in several vacancies in the board regulator, which reduces the regulator’s scope of action. Filling those vacancies is a first critical step to ensure that the regulator can operate effectively and that the existing regulations to foster competition are fully applied, including by sanctioning incumbent dominant companies when they do not meet the requirements established in laws. Modernising regulations, by applying additional mechanisms to accelerate effective competition, removing obsolete requirements, strengthening cybersecurity or establishing regulations for deploying private networks into industrial parks, would also be key to boost digitalization.

Pro-competition regulation in goods and services markets can lift productivity and facilitate investment, both by domestic and foreign firms. Weak competition favours high prices and rent seeking behaviours and weakens innovation incentives. Fostering competition can also contribute to the fight against climate change. This is particularly the case in energy markets, where higher competition can drive down prices of green energy options and incentivise investment in cleaner and more efficient technologies, contributing to a lower carbon footprint. Mexico’s electricity and oil markets are good examples of how strengthening competition, in the case of these two markets by enabling higher private sector participation (see also the renewable energies section below and 2022’s Mexico Economic Survey), would simultaneously make Mexico more attractive to attract investment and enhance efforts to combat climate change.

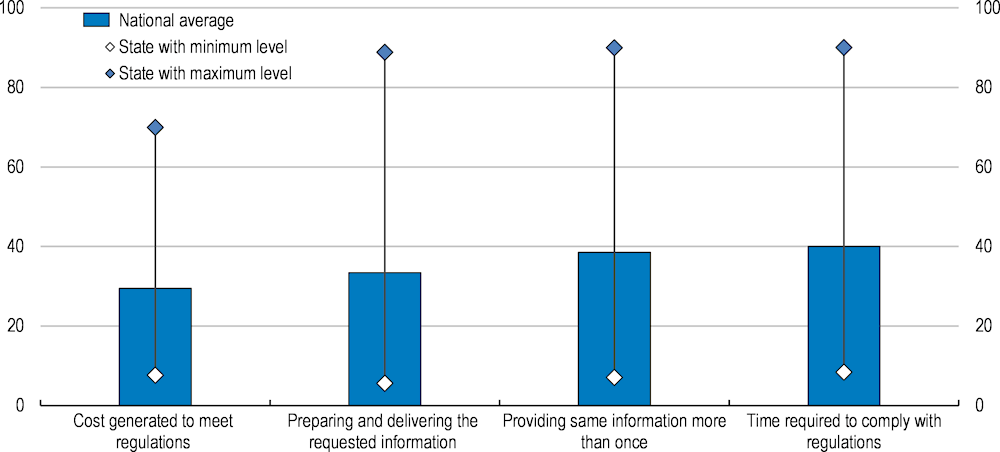

Perceptions of barriers to meet regulatory requirements, % of enterprises, 2020

Source: INEGI, Encuesta Nacional de Calidad Regulatoria e Impacto Gubernamental en Empresas 2020 (ENCRIGE).

Overall, Mexico has made good progress in improving regulations at federal level, including by establishing regulatory impact assessment. At the same time, Mexico's federal system gives a significant amount of autonomy to its states and municipalities in terms of regulations. While this can allow for greater flexibility and responsiveness to local needs, it also creates a complex regulatory environment with varying requirements and standards across different regions. 40% of Mexican firms cite the time required to comply regulations as a key barrier for their operations. In some states the share reaches 80% (Figure 3.9). Regulations related with the establishment of formal companies, such as licensing and permitting procedures, are particularly complex. This complexity can make it difficult for businesses, particularly SMEs, to navigate the regulatory environment, leading to increased costs and delays in approval processes. It also makes it challenging for firms to grow and to expand across different states, as they would need to navigate varying regulations and compliance requirements, which also hampers competition. It can also create opportunities for corruption, as officials may use their discretion to enforce regulations selectively or demand bribes in exchange for regulatory compliance. Efforts have been made to address this issue in Mexico, such as through the creation of federal standards for certain sectors and the implementation of e-government platforms to streamline regulatory processes. However, further policy efforts are warranted (Table 3.1).

|

Past OECD recommendations |

Actions taken since the 2022 survey |

|---|---|

|

Provide investors with certainty about existing contracts and regulatory stability. |

No action taken |

|

Continue to strengthen the fight against corruption, including by boosting technical expertise in anticorruption agencies. |

No action taken |

|

Establish a comprehensive strategy to reduce the cost of formalization, including reducing firms’ registration costs at the state and municipal level. |

No action taken |

Establishing regional regulatory harmonization agreements could reduce regulatory heterogeneity and the associated cost. Mexicos’s National Commission for Regulatory Improvement (CONAMER), is responsible for coordinating regulatory improvement efforts across different levels of government in Mexico. CONAMER has started to compile the National Catalogue of Regulations, Procedures and Services (Catálogo Nacional de Regulaciones, Trámites y Servicios), a tool aiming at compiling information about all regulations from federal government, state and municipal governments. So far regulations from 5 out of 32 states and 7 out of 2541 municipalities are in the catalogue. Work has started with other 123 municipalities. Completing the catalogue would be a key step to enhance transparency. It could be followed up by introducing a legal requirement that government agencies are not entitled to request any document that has been already provided to another government agency. This could reduce regulatory overlaps and encourage the deployment of e-government platforms to allow firms and individuals to submit and track all regulatory requirements online. Some states and municipalities, such as the State of Yucatan and the City of Puebla, have recently put in place one-stop e-government platforms, where all licences and permits to start operations can be resolved online, reducing or eliminating the need for physical visits to different regulatory agencies. Deploying this platforms throughout the country would reduce significantly regulatory burden, benefiting particularly SMEs.

CONAMER has also established certification procedures to promote regulatory improvement across states and municipalities. States, municipalities or federal agencies successfully fulfilling a set of requirements about regulatory improvement established by CONAMER obtain a certificate of regulatory quality. These procedures increase transparency and certainty for firms and individuals and have the potential to trigger simplification efforts across the three levels of government. First certifications were issued in mid-2020. A gradual process of certification is taking place but there is room for a larger share of municipalities and states going through the certification procedures. Efforts to continue promoting and publicizing these certificates and to encourage its adoption, for example by providing additional financing to states adopting them, are warranted.

Beyond regulations, independent and well-resourced competition authorities and sector regulators are critical building blocks for a solid competition framework. Mexico’s competition authority ability to attract and retain skilled staff has been hampered by a budget cut and the application of salary ceilings. The scope of action of some regulators has been limited, as some positions in their boards have remained vacant, as no candidate was proposed by the government. Ensuring that the competition authority and regulators in key markets, such as telecommunications or energy, remain independent and operative is fundamental to achieve competitive prices of goods and services that are key inputs for Mexican firms, thereby increasing their competitiveness, the ability to attract foreign investment and improving the prospects for stronger linkages between foreign and domestic companies.

Ensuring investors, both domestic and foreign, with certainty about existing contracts and with regulatory stability, as recommended in the 2022 Economic Survey of Mexico, would also enhance competition. This would facilitate attracting investors, leading to stronger competition within goods and services markets.

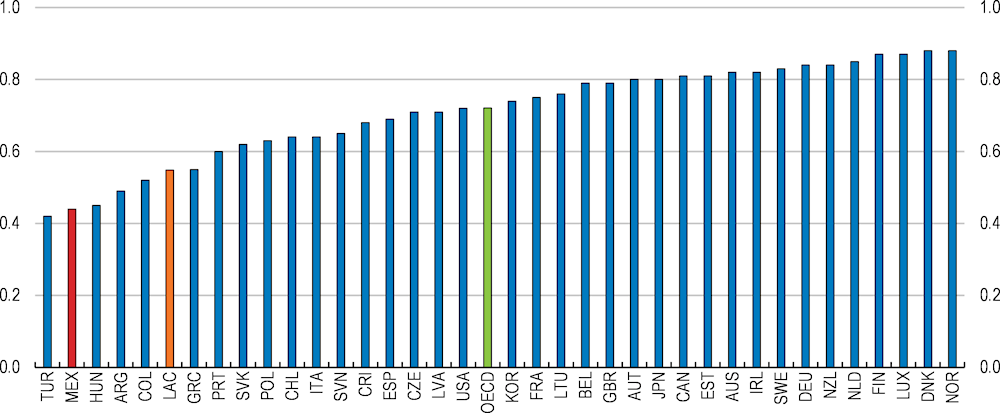

Governance and the quality of institutions also matters for productivity growth and FDI attraction. A key challenge in Mexico is that, while appropriate legislation may be in place, enforcement is weak (Figure 3.10). This can limit the growth and productivity of domestic SMEs, as they can opt for limiting commercial relationships to avoid having commercial disputes. Weak enforcement also hampers financial inclusion, by complicating collateral seizures. Enforcement of environmental standards and regulations, which have become more sophisticated in Mexico City and other major cities , is also lacking (SGI, 2022[5]), hindering the green transition.

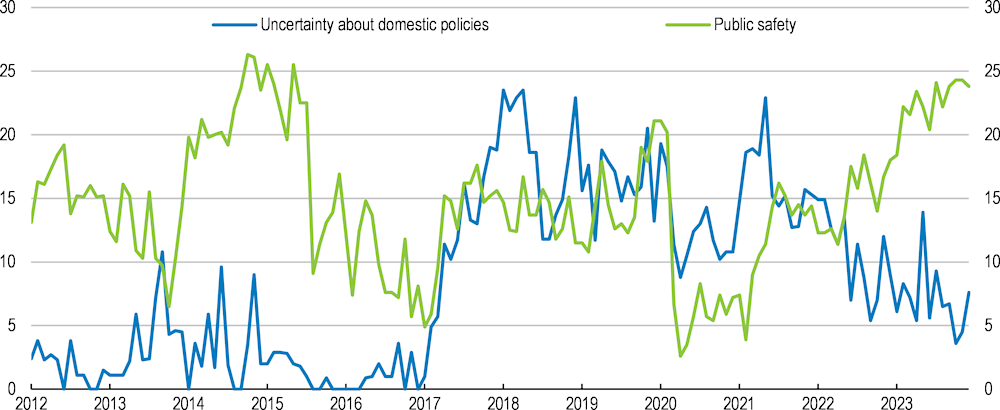

Improving law enforcement would also help in the fight against crime, which remains high (Figure 3.11), is a key concern for firms (Figure 3.12) and hinders citizens’ well-being, particularly women. Low enforcement means that impunity remains also high, reaching 90% in some states. Crime and impunity translate into higher costs for firms, limiting the potential benefits of nearshoring. They increase the need to invest in safety measures, diverting resources that firms could have invested in productivity-enhancing areas.

Extent to which legislation is fairly and effectively implemented and enforced, index from 0 to 1 (highest), 2023

Note: LAC is an unweighted average of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru.

Source: Factor 6 of the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index.

Homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants

Share of specialists’ responses identifying uncertainty and safety as risks for economic growth, %

Note: Specialists were asked the following question: "In your opinion, what are the three principal factors that will limit growth in economic activity over the next six months?"; they could select up to three factors.

Source: Banxico (Encuestas Sobre las Expectativas de los Especialistas en Economía del Sector Privado).

The federal government's spending on public security and justice accounted for 1.3% of GDP in 2020, below the 1.5% of GDP recorded in 2018. Ensuring that the judiciary system, including judges, lawyers and police, receive adequate resources, training, an integrity framework and technology, would be key to accelerate the decline in crime rates and speed courts performance, which would help to reduce impunity and improve contract enforcement. Efforts to increase the digitalization of the Mexican justice system would be particularly valuable. By implementing modern technologies, such as digital case management systems, electronic evidence submission, and online court proceedings, the justice system can streamline processes, reduce paperwork, and expedite case resolutions. Digital platforms can also enhance transparency and accessibility, allowing citizens to track their cases online and reducing the likelihood of corruption. Data analytics can also assist judges and law enforcement agencies in making informed decisions and allocating resources more effectively. Increasing the use of out-of-court mediation mechanisms to settle commercial disputes would also help to accelerate commercial disputes resolution and alleviate pressures in courts. The successful experience of some municipalities previously burdened by high criminal violence suggests that strengthening collaboration between citizens, the three levels of government and the respective military and police forces, providing them with top technology and improving police remuneration, can help to reduce crime and violence (Aguayo and Dayán, 2021[6]).

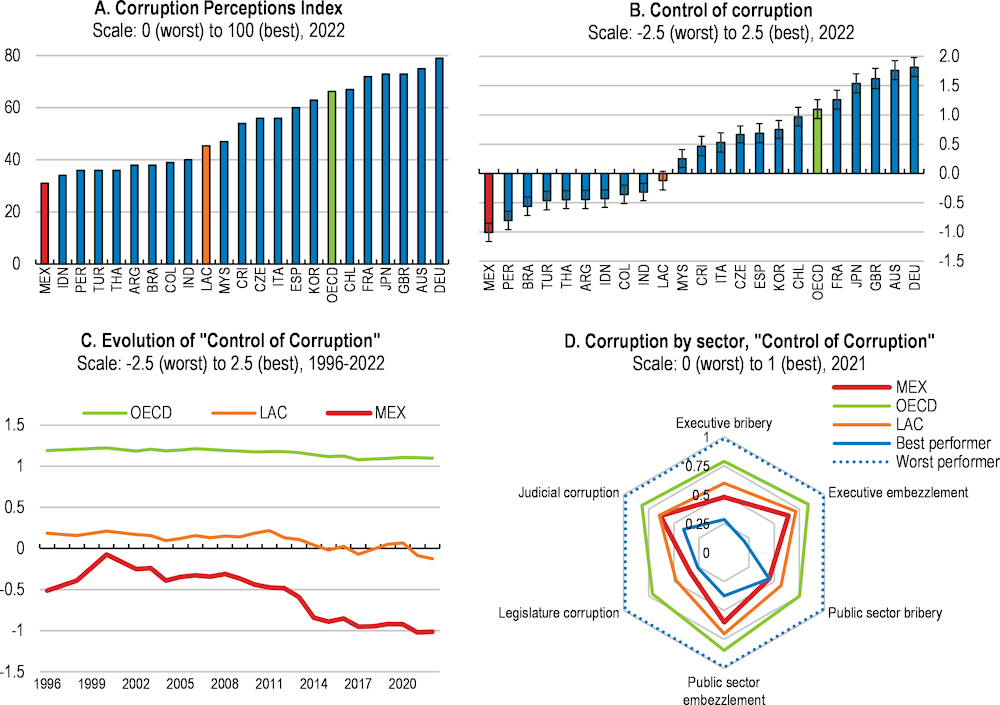

Mexico has been making efforts to fight corruption, including the launch of a National Anti-Corruption System, which included a new anti-corruption prosecutor's office and an independent administrative tribunal, although the impact of these efforts remains to be tested in practice. It also created a Citizen Participation Committee to oversee and provide input on anti-corruption measures. Efforts have been also pursued at state level, with heterogenous results. Corruption perceptions continue well above those in OECD and regional peers (Figure 3.13). Pursuing policy efforts in this area is therefore warranted. Strengthening the resources and independence of anti-corruption agencies, including at state level, would increase their ability to investigate and prosecute corruption cases more effectively. Indeed, of the 31 445 cases opened by state anticorruption attorneys, only 243 ended up in a sanctioning sentence (less than 1%). Ensuring the full appointment of key positions in the anti-corruption institutions is critical for its functioning. There is also room to increase the use of public procurement, to limit the scope for corruption in direct awards. Some states have made good progress in strengthening public procurement governance and limiting direct contracting (OECD, 2023[7]). Replicating these efforts in other states would boost public spending efficiency and reduce the scope for corruption. Increasing the use of e-procurement processes and professionalising the public procurement workforce, both in the federal government and at state level, has also good potential to reduce the scope for corruption, as illustrated by experiences in several OECD countries (Box 3.2).

E-procurement, the use of information and communication technologies in public procurement, can increase transparency, reduce direct interaction between procurement officials and companies, increasing competition and allowing for easier detection of irregularities and corruption, such as bid rigging schemes. The digitalisation of procurement processes strengthens internal anti-corruption controls and detection of integrity breaches, and it provides audit services trails that may facilitate investigation activities (OECD, 2016[8]). Korea introduced in 2002 a fully integrated, end-to-end e-procurement system called KONEPS, which covers the entire procurement cycle electronically. Evaluations signalled a significant increase in integrity perceptions after adopting KONEPS. Estonia also illustrates the merits of putting in place user-friendly e-procurement processes. The register is free of charge for all contracting authorities and suppliers and offers the full range of e-procurement services, including e-notification, e-access and e-submission. After the introduction of e-procurement in Estonia, corruption cases related to public procurement remain limited (EC, 2015[9]).

Note: LAC is an unweighted average of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru. Panel B shows the point estimate and the margin of error. Panel D shows sector-based subcomponents of the “Control of Corruption” indicator by the Varieties of Democracy Project.

Source: Panel A: Transparency International; Panels B & C: World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators; Panel D: Varieties of Democracy Project, V-Dem Dataset v12.

Mexico’s large renewable resources stand as a potent competitive advantage, aligning with ongoing manufacturing companies’ efforts to decarbonize their production process, which requires abundant clean energy. Mexico’s renewable resources are well distributed throughout the country, facilitating that all Mexican regions could reap the benefits of nearshoring. Solar power potential is very high in large parts of the country, particularly in the west. Moreover, the southeast region combines significant solar, wind and geothermal potential and the largest water resources in Mexico. This gives the region the potential to become an energy hub, exporting clean energy to the rest of the country and to Central America.

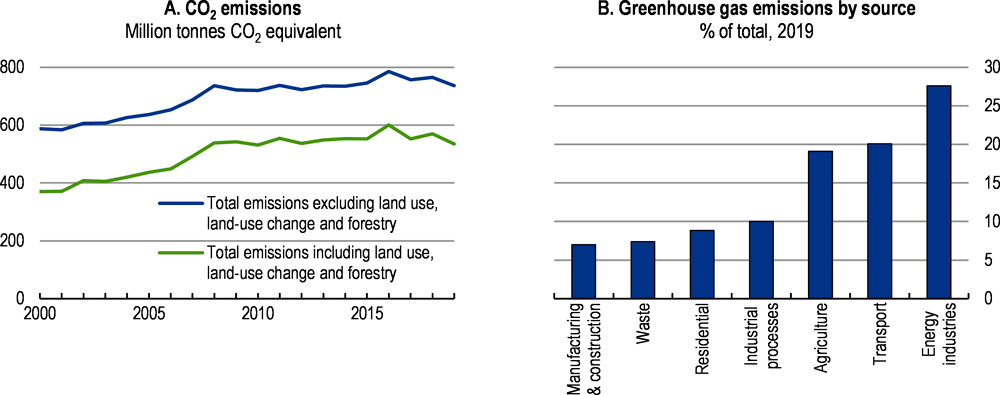

Source: OECD, "Air and climate: Greenhouse gas emissions by source", OECD Environment Statistics (database); and OECD Green Growth Indicators.

Carbon pricing is increasing in many countries, which has triggered concerns about carbon leakage and some proposals to introduce border carbon adjustment mechanisms (EU, 2023[10]). At the same time, Mexico is already suffering from climate change and has one of the highest prevalence of extreme climate-related events in Latin America (Cárdenas et al., 2021[11]). Mexico updated its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) in 2022, committing to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emission by 35% from business-as-usual levels by 2030 without condition, and by 40% if external support is secured. These updated targets are less ambitious than those set in 2016, are not consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit in the Paris Agreement (Climate Action Tracker, 2022[12]), and do not set net zero targets nor targets beyond 2030. Thus, stepping efforts to transition towards carbon neutrality would help to address and mitigate climate change and, at the same time, would help Mexico to maintain and reinforce its trade competitiveness in a global economy that is transitioning towards lower carbon content.

A forceful shift to renewables energy would be a key building block in such strategy to reduce GHG emissions, as energy and transport sectors are the largest emitters (Figure 3.14). Conversely, the land use, land-use change and forestry sector has been a stable sink of GHG emissions over the last 20 years. Transitioning towards massive urban and interurban transport, as discussed and recommended in the 2022 Economic Survey and in chapter 5 in this survey, would also be key to reduce traffic congestions and emissions.

Improving carbon pricing is another key building block of a more forceful decarbonization strategy. Mexico was the first emerging economy to introduce a carbon price in 2014. At 2 EUR per ton of CO2, the federal carbon tax is well below the low-end estimate of climate-related costs of carbon emissions of around 60 euros per tonne (Marten and Dender, 2019[13]). It covers road fuels, but not fuels used in other sectors, such as natural gas, and coal is taxed at a reduced rate. Broadening the carbon tax base and gradually increasing the rate would induce further emission cuts. It also implies significant political economy challenges. Phasing in the increase in a gradual manner and using part of the additional revenues to offset the effects of higher energy prices on low-income households could facilitate buy-in. Besides higher carbon taxes, non-price measures will also be needed to address climate change (OECD, 2022[4])].

Mexico piloted in 2020 and 2021 an emissions trading scheme, the first in Latin America, covering 300 large entities in the energy and industry sector. During the pilot phase emission allowances were freely allocated. The pilot phase was planned to be followed by a transition to a fully-fledged emission trading scheme in 2023 with several hundred companies expected to participate. Pursuing these plans would be a significant step ahead to reduce emissions.

Despite the strong renewables potential, about 90% of primary energy supply comes from fossil fuels and the share of electricity generated from renewable sources remains low in comparison with OECD and peer regional countries (Figure 3.15). By law at least 35% of electricity generation should come from clean energy sources by 2024, including hydroelectric, however, this share stood at 26.1% in 2022 down from 27.5% in 2021 (IMCO, 2023[14]) and both wind and solar generation fell during 2022 for the first time since there are registers.

% of total electricity generation from renewable sources, 2021 or latest year

Note: LAC is a simple average of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru.

Source: OECD Green growth indicators.

While recent government initiatives, including the Sonora Plan to build the largest solar plant in Latin America and new projects executed by the public utility company aim at increasing renewables generation, more will be needed to convert Mexico’s renewables potential into a competitive advantage. Critically, it will require regulations that promote private sector investment in renewables projects and regulatory and legal certainty. Since 2018 private sector renewable generation has been subject to large uncertainty. In 2019 long-term auctions for renewable energy generation were suspended. In 2021 a constitutional reform proposal established a guaranteed market share for the state-owned electricity company of at least 54% and eliminated independent regulators overseeing competition and granting permits (OECD, 2022[4]). Once regulations promoting private sector investment get in place, ongoing efforts to develop sustainable financing instruments (see Chapter 2) can make an important contribution to greening the electricity matrix, by facilitating that private sector projects get financing at better terms.

Improving transmission and distribution infrastructure will also be essential. Transmission and distribution grids have suffered from underinvestment for some time. Saturation and congestion in several corridors have increased (Carrillo et al.;, 2022[15]), and will increase further, as electricity demand is expected to grow significantly. Since 2013, the state company in charge of the grids has not spent the resources allocated in the federal budget for physical investment in transmission. Ensuring that budget allocations are used to improve the grids, and gradually increasing investment, will be essential to ensure a reliable and cost-effective availability of clean electricity around the country.

The shift to renewable energies could have a marked impact on workers in regions highly dependent on oil, such as Campeche or Tabasco. Deploying comprehensive training programs for displaced workers, equipping them with the necessary skills to access job opportunities in new sectors, is key to minimise the social impact of job displacements. It can also facilitate addressing skill shortages in thriving sectors, such as those related to new manufacturing activities getting relocated to Mexico or those related with the deployment of renewable energy parks.

Ensuring sustainable water management is paramount to leverage nearshoring opportunities effectively. Efficient water management would not only safeguard the country's limited water resources but also enhance the reliability of water supply for businesses, reducing operational risks and costs. It should also be a key building of Mexico’s climate change adaptation strategy and, by promoting environmental sustainability and compliance with international standards, would make Mexico an even more appealing destination for nearshoring.

Over the past decades, the amount of water available for each person has declined drastically due to climate change and population growth and Mexico has one of the lowest shares of the population connected to public wastewater treatment plants in the OECD (OECD, 2017[16]). A key challenge to better water management is improving the accuracy and availability of up-to-date data on water resources, use, and quality. There is also room to strengthen water governance, as responsibilities are highly fragmented, which hampers policy coordination and accountability. There is a mandate from the Supreme Court to issue a General Water Law by August 2024, which is an opportunity to improve water governance and regulations, for example by granting the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) a stronger stewardship role in the sector. The methodology to set water tariffs is heterogeneous, as it is decided at municipal level, and lacks transparency (IMCO, 2023[17]). Prices do not reflect the cost of the provision of water, with the difference being covered trough subsidies from the Federal Government. Mexico needs also to invest in water supply and sanitation infrastructure to reduce leakages – currently around 46% of water is lost due to leakages (Lopet et al., 2017[18]) – and improve water treatment and distribution. Such investments could be supported by enhancing the cost-recovery capacity of tariffs. Affordability issues can be tackled through targeted transfers to low-income households.

|

MAIN FINDINGS |

CHAPTER 3 RECOMMENDATIONS (Key recommendations in bold) |

|---|---|

|

Boosting productivity |

|

|

Large infrastructure projects are underway to improve connectivity but there is room to enhance logistics and trade facilitation. |

Make a greater use of advanced rulings at customs and improve the availability of information, including by digital means, and appeal procedures. Remove foreign direct investment restrictions in logistics-related services, such as customs brokerage, road transportation, cargo handling or storage. |

|

Certification procedures can facilitate SMEs becoming suppliers to larger firms by demonstrating their commitment to meeting high standards and product reliability. Going through the certification process is costly and lengthy. |

Simplify certification procedures and support SMEs, including financially, in achieving certifications in areas such as product quality or environmental impact. |

|

Many parts of the country still lack access to high-speed internet. Regional differences in digital connectivity are large. The telecommunication market remains very concentrated. |

Streamline and harmonize e-communications regulations. Enforce the sharing of the digital infrastructure. Maintain an independent and well-resourced telecommunications regulator and ensure that existing regulations to foster competition are fully applied. Modernise telecommunication regulations by strengthening cybersecurity, establishing regulations for deploying private networks into industrial parks and removing obsolete requirements. |

|

The regulatory framework is complex and imply high compliance costs due to heterogeneous requirements and standards across states and municipalities. Procedures have been established to promote regulatory improvement across states and municipalities. There is room to increase their take-up. |

Complete the National Catalogue of Regulations, Procedures and Services. Continue to deploy e-government platforms at state and municipal level to allow firms to submit and track all regulatory requirements online. Further promote regulatory improvement certificates and encourage its adoption by providing additional financing to states adopting them. |

|

The competition authority ability to attract and retain skilled staff has been hampered by a budget cut and the application of salary ceilings. The scope of action of some regulators has been limited, as some positions in their boards have remained vacant. |

Ensure that the competition authority and regulators in key markets, such as telecommunications or energy, remain independent and operative. |

|

Enforcement of existing legislation is weak. Crime and impunity remain high in many states, hindering economic activity and citizens’ well-being, particularly impacting women. |

Further advance the digitalization of the judiciary system by providing it with adequate resources and training. Increase the use of out-of-court mediation to settle commercial disputes. Strengthen collaboration between the three levels of government and the respective police and military forces and the interconnection of their IT systems. |

|

Corruption perceptions remain high. The coverage of public procurement is low. Direct awards create opportunities for corruption. |

Continue to strengthen the fight against corruption, including by strengthening the resources, technical expertise, and independence of anti-corruption agencies, including at the state level. Limit direct awards and increase the use of public procurement. Strengthen e-procurement processes in federal and state governments by covering all the public procurement cycle and adopting internationally accepted standards. Strengthen the professionalization of the public procurement workforce. |

|

Increasing renewables and improving carbon pricing and water management |

|

|

The bulk of primary energy use comes from fossil fuels. Mexico’s renewable resources potential are large and well distributed throughout the country. Regulation uncertainty undermines renewables generation. Transmission and distribution grids suffer from underinvestment. |

Adopt regulations that promote private sector participation in renewables generation, ensure legal certainty and expand and improve electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure. |

|

The carbon price is well below the low-end estimate of climate-related costs of carbon emissions |

Gradually increase the carbon tax, broaden its base, and use part of the revenues to offset the effects of higher energy prices on low-income households. |

|

Water stress is high and being exacerbated by climate change, over-extraction, inefficient water management, and pollution. Policy responsibilities are highly fragmented, hampering coordination and accountability. Forty-six percent of water is lost due to leakages. |

Enhance the water information system to ensure it provides accurate and up-to-date data on water availability, use, and quality. Improve water governance and regulations by grating the National Water Commission a stronger stewardship role. Gradually increase investment in infrastructure for water treatment and distribution. Improve the methodology to set water tariffs to enhance their cost-recovery capacity. |

[6] Aguayo and Dayán (2021), “Defeating Los Zetas. Organized Crime, The State and Organized Society in La Laguna, Mexico, 2007-2014”, El Colegio de Mexico.

[2] Alfaro-Urena et al. (2019), “The Effects of Joining Multinational Supply Chains: New Evidence from Firm-to-Firm Linkages”, Avaiable at SSRN, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3376129 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3376129.

[11] Cárdenas et al. (2021), “Climate policies in Latin America and the Caribbean. Success Stories and Challenges in the Fight Against Climate Change”, Inter-American Development Bank.

[15] Carrillo et al.; (2022), “The energy Mexico needs”, IMCO.

[12] Climate Action Tracker (2022), Country Assessments: Mexico, https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/mexico/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

[9] EC (2015), “Public procurement – Study on administrative capacity in the EU Estonia Country Profile”.

[10] EU (2023), “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism regulation in the Official Journal of the EU”, European Union, 17 May 2023.

[17] IMCO (2023), “El costo del agua en México: Un análisis de tarifas y de sus impactos para la sociedad.”.

[14] IMCO (2023), “Se estanca el crecimiento de las energías eólica y solar fotovoltaica en México”, Nota Informativa.

[18] Lopet et al. (2017), “El agua en México. Actores, sectores y paradigmas para una transformación social- ecológica”, Fundación Friedrich Ebert..

[13] Marten, M. and K. Dender (2019), “The use of revenues from carbon pricing”, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No. 43, OECD, Paris.

[20] Marten, M. and K. van Dender (2019), “The use of revenues from carbon pricing”, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No. 43, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[7] OECD (2023), “Follow-up Review on Public Procurement in the State of Mexico. Identifying Critical Reforms for the Future”.

[4] OECD (2022), “OECD Economic Surveys: Mexico 2022”.

[19] OECD (2019), Supplement to Taxing Energy Use 2019: Country Note - Mexico, OECD publishing, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/taxing-energy-use-mexico.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2021).

[16] OECD (2017), “Improving climate adaptation and water management. Mexico Policy Brief”.

[8] OECD (2016), “Preventing Corruption in Public Procurement”.

[5] SGI (2022), “Sustainable Governance Indicators: Mexico Note”.

[1] Vidal and A. González Pandiella (forthcoming), “A review of Mexico’s participation in Global Value Chains”, Technical Background Paper.

[3] World Bank (2022), “Productivity Growth in Mexico. Undestanding main dynamics and key drivers”.