Alberto González Pandiella

OECD

Alessandro Maravalle

OECD

Alberto González Pandiella

OECD

Alessandro Maravalle

OECD

Continuing the recent fall in income inequality and poverty will necessitate stepping up efforts to both address pressing social issues and bolster economic growth. Redoubling efforts to improve education outcomes would help Mexicans gaining the skills needed to participate in an evolving job market and boost Mexico’s growth potential. Mexico has much to gain from closing gender participation gaps, as it would lead to stronger growth overall and to a more equitable distribution of income and opportunities. Reducing informality would not only ensure greater job security and social protection for workers but also stimulate economic growth.

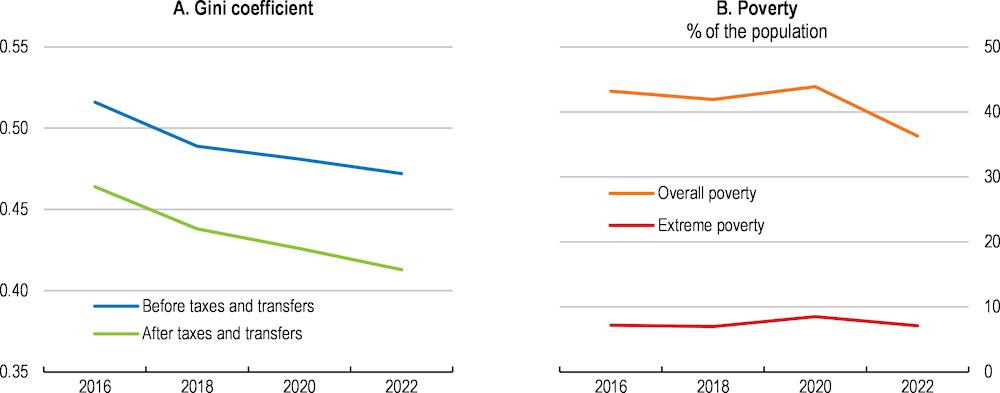

Reducing income inequality and poverty are long-standing challenges for Mexico. After increasing during the pandemic, both inequality and poverty rates have recently fallen (Figure 4.1). Increases in minimum wages and in some social transfers, particularly universal non-contributory pensions, contributed to that outcome. Around 34% of Mexican households are receiving support from government social programmes, up from 28% in 2018 (CONEVAL, 2023[1]). Despite this progress, extreme poverty has remained broadly stable around 7%. This chapter discusses the critical long-standing challenges of improving education outcomes and reducing gender gaps and informality, which are key to continue alleviating poverty and inequalities in Mexico and to stimulate economic growth. Besides addressing these challenges, improving the targeting of social programmes is another pending challenge, as discussed in detail in the 2022 Economic Survey. Building a national registry of social programmes beneficiaries, covering programmes run by different levels of government, as recommended in that survey, would be a decisive step to improve targeting and reduce inequality and poverty.

Note: Panel B uses the multi-dimensional indexes of poverty compiled by CONEVAL. The population in (extreme) poverty refers to people with an insufficient monthly income to acquire necessary food, goods and services (food) and with at least one (three) social deficiency.

Source: México cómo vamos; CONEVAL.

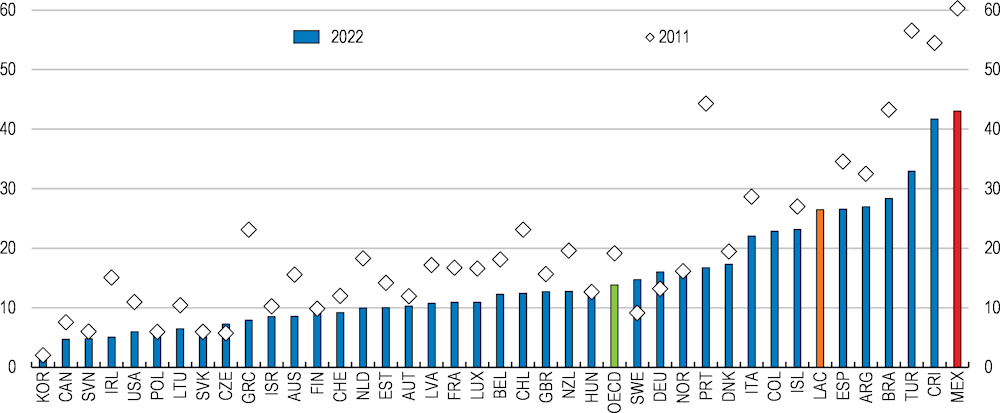

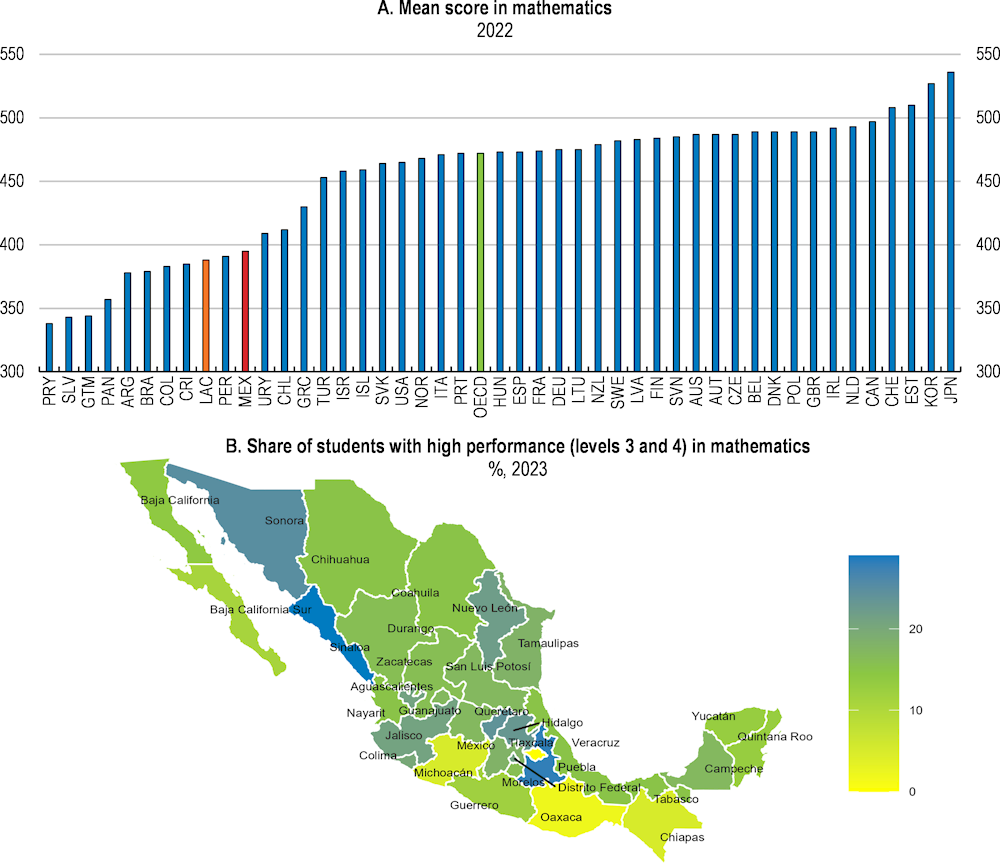

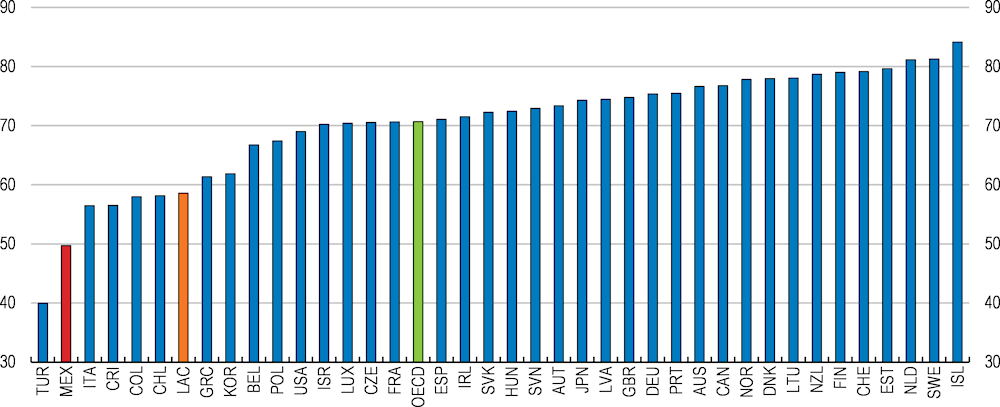

Mexico has a relatively young population, with significant potential to adapt to global trends that are reshaping skill needs, such as digitalization or decarbonization. Good skills are also becoming central in strategies to attract foreign direct investment. Realizing this potential requires tackling two challenges. First, while access to education is nearly universal in Mexico, still too many students leave the education system without completing secondary education (Figure 4.2). A second challenge is that there is room to increase education quality (Figure 4.3, panel A) and to reduce regional differences (Figure 4.3, panel B). Moreover, Mexico’s education system was severely impacted by the pandemic, which caused one of the longest schools’ closures in the OECD and widened educational lags (CONEVAL, 2023[1]). As in other OECD countries, 2022 PISA results were down in Mexico compared to 2018 in mathematics, science and reading. The fall was particularly acute in mathematics, as it reversed most of the gains observed over the 2003-2009 period, and average scores returned close to those observed in 2003 (OECD, 2023[2]).

Percentage of 25-34-year-olds with below upper-secondary education as the highest level attained

Note: LAC is a simple average of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, and Brazil.

Source: OECD Education Database.

Note: Panel A: LAC is an unweighted average of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru.

Source: OECD PISA International Dataset; Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad.

Overall, a first worthy step would be to assess the effectiveness of the education system as a whole with a view to design and set up measures to increase graduation rates and quality, as illustrated by positive experiences in several OECD countries (Box 4.1). More comprehensive and homogeneous information about registered students, number of teachers and individual students’ trajectories would enable a robust evaluation of education policies, help to adjust its design, and make the most of education spending. It would also allow putting in place early warning mechanisms to identify students in need of targeted tutoring support and assessing and resolving teachers’ training needs.

For younger children, extending schedules beyond the current 4.5 hours per day at primary school would have a positive and long-lasting impact on students’ performance and decrease delays in schooling completion (Cabrera-Hernández et al., 2023[3]), particularly in schools in more vulnerable areas (CONEVAL, 2018[4]). Strengthening early childhood education and care would also particularly improve education outcomes of children in low-income households. Both lengthening primary schools’ schedules and widening the availability of early education would also facilitate female labour market participation, as elaborated in the next section of this chapter.

Several OECD countries have stepped up efforts to improve educational data systems and to foster robust evaluations to upgrade education policies.

Collecting comparable data: Australia and the United States, countries with highly decentralized education systems, as Mexico, illustrate the benefits of collecting comparable data and having a shared information system. For example, in the state of Maryland in the United States, whose public school system is among the highest performers nationwide, schools use data to monitor learning progress and student’s needs. Australia built a national repository of detailed information on all schools in the country, based on a legal framework established at federal level which ensures regular and mandatory reporting by schools. Funding allocation is dependent upon data reporting, which incentivizes data collection and school buy-in. It has contributed to a data-driven culture with open data access for education stakeholders and a focus on learning of disadvantaged groups (Abdul-Hamid, 2017[5]). Increasing data availability and their timelines help to establish early warning systems, which can prevent students dropping out. In the city of Chicago, a large and diverse education system, they contributed to an increase in secondary graduation rates from 52% in 1998 to above 90% by 2019 (OECD, 2021[6]).

Evaluation: Several OECD countries have put evaluation at the forefront of efforts to enhance the quality, equity and efficiency of education systems. Norway established a comprehensive evaluation and assessment framework that provides monitoring information at different levels, fosters schools accountability and monitors the equity of education outcomes (OECD, 2011[7]). France, through the IDEE programme, facilitates access for researchers to educational administrative data and seeks to strengthen research partnerships among education professionals, policymakers, and research centers.

Education spending needs to be better targeted to reduce differences in education outcomes across states. The distribution of the main earmarked transfer for education is based on a formula including different criteria, such as the number of students and education quality. The formula could be improved by giving a greater weight to education quality and using a broadly agreed and transparent definition of education quality. Incentives could also be improved by providing additional resources to those states that achieve an improvement in education outcomes. Experience in some countries in the region, such as Brazil, illustrate that an effective mix of increasing resources and introducing incentive mechanisms can lead to significant improvements in education outcomes. The state of Ceará, which, starting from a low level, became one of the states with the best quality education in Brazil (OECD, 2018[8]), attests to that.

There is also room to further increase the share of tertiary graduates and aligning training supply with labour market needs, particularly as concerns digital skills. Increasing quality in primary and secondary education is a necessary step to continue Mexico’s progress in increasing tertiary graduation rates (Figure 4.4). While Mexico graduates one million tertiary students every year, one third of them in STEM areas, with ongoing changes in skill demand at the global level and nearshoring in Mexico, efforts to align training supply with labour market needs are advisable. Using skill anticipation assessments and systematic consultation with the business sector at the state level, remain important. Some states are moving in that direction and are stepping up efforts to adapt tertiary programmes to increasing demand for more specialised skills.

Redoubling efforts to ensure that all Mexicans, including those that abandoned the education system with low skills, acquire relevant skills would also help to reduce firms’ difficulties in finding the skills they require. 75% of employers report difficulties filling jobs due to lack of the appropriate skills, a proportion that is increasing (IMCO, 2023[9]). Skilled trades, engineers and production operators/machine operators are within the top five jobs employers report having difficulty filling. Scholarship programmes, such as Becas Benito Juarez, have become the backbone of social policies and their impact on providing recipients with skills helping to access formal quality jobs should be thoroughly evaluated.

Dual vocational programs, designed and launched in partnership with German authorities and in strong collaboration with the private sector, are being gradually deployed across the country with positive outcomes in terms of acquired skills (SEP, 2023[10]). Efforts to facilitate that more students and firms participate in dual programmes would boost the availability of technical skills and access to formal jobs. This could be achieved by reserving a share of scholarships for dual vocational programmes and by creating institutional arrangements enabling SMEs to participate in training activities. Experience in OECD countries also suggests that vocational programs can be particularly useful to reskill adult workers that left the education system before completing their studies.

Percentage of 25-34-year-olds with tertiary education as the highest level attained

Note: LAC refers to Chile, Costa Rica, Argentina, and Brazil.

Source: OECD Education Database.

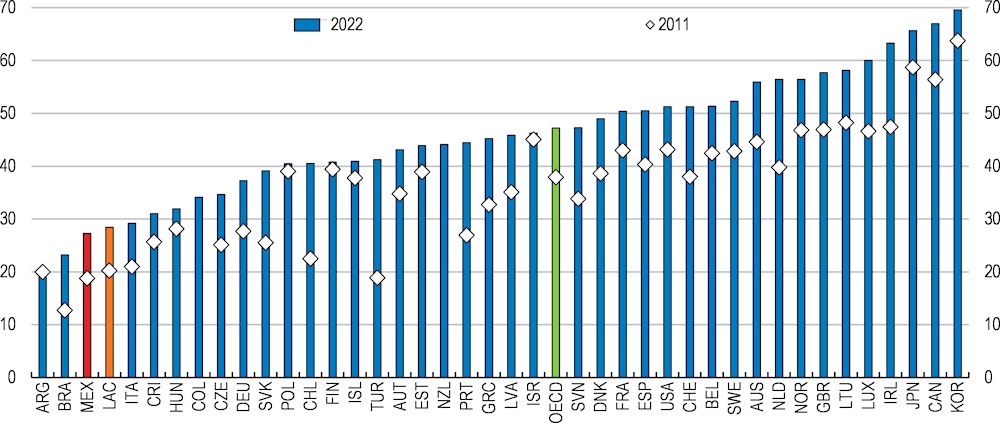

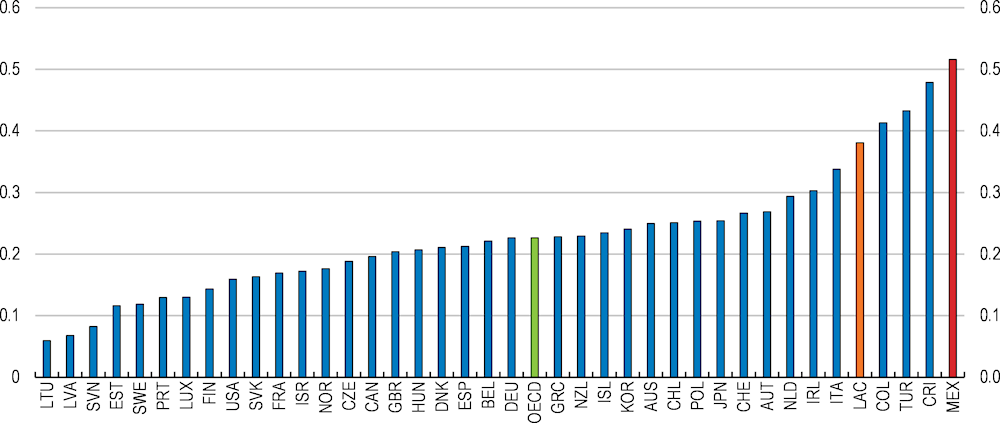

Gender equality is not only a moral imperative but also translates into higher economic growth and well-being. Female labour force participation in Mexico has recently increased but it continues to significantly lag other OECD and Latin America countries (Figure 4.5). Gains from increasing the integration of women into the labour market are particularly large for Mexico (Figure 4.6). Growth would be boosted by increasing labour input and also by improving productivity, as it would allow a better matching between workers and jobs. Making a more efficient use of the available female talent would also boost Mexico’s competitiveness and help to grasp nearshoring opportunities.

% of female population aged 15-64, 2022

Note: LAC is a simple average of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, and Brazil. Data for Argentina refer to the year 2021.

Source: OECD Labour Force Statistics.

Difference relative to the baseline in projected average annual rate of growth in potential GDP per capita, percentage points

Note: The projections assume that labour force participation and working hours gaps close by 2060. For labour force participation, this is based on convergence of male and female levels to the highest level for each 5-year age groups in each country, following baseline labour force

projections over the period 2022-60. LAC is a simple average of Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica.

Source: (OECD, 2023[11]).

Beyond the gap in participation, gender gaps exist also in the quality of jobs, with informality being more prevalent among women and with women earning less than men. The average monthly gender pay gap for all full-time workers is 17% in Mexico, compared to the OECD average of 12%. Many factors explain wage gender gaps, including women’s higher probability of career interruptions, occupational and sectoral segregation, employer discrimination, and women’s disproportionate responsibility for unpaid work at home.

Domestic and care responsibilities fall disproportionally on Mexican women, hampering their prospects to complete education or be in the labour force. On average, Mexican women devote 40 hours per week to domestic and care work while men spend 15 hours (INEGI, 2021[12]). The gap is wider in households with children below 6 years old and in rural areas. Women are also more likely to make career breaks around childbirth, contributing to a motherhood penalty in wages. Excessively long working hours, prevalent in Mexico, particularly hinders women. Promoting and encouraging, both in the public and in the private sector, flexible working hours, the temporary use of part-time work for family reasons and remote work can help women and men combine family responsibilities with paid work and help to reduce gender gaps.

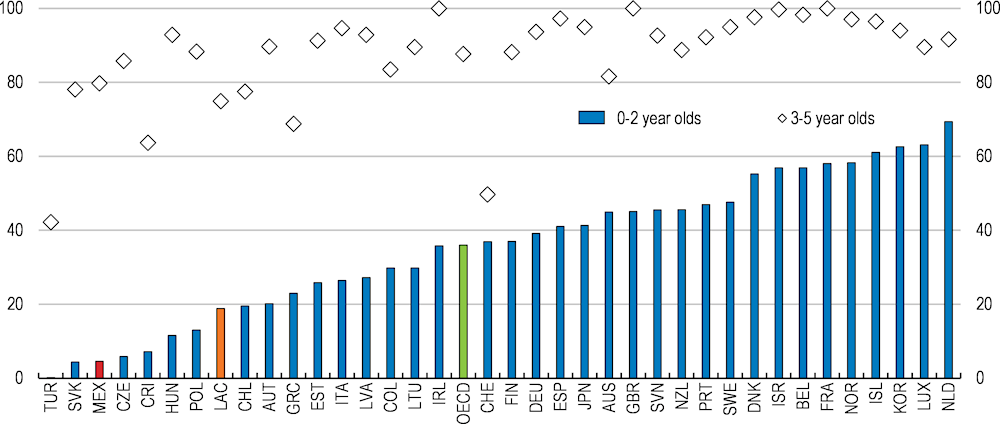

A comprehensive early childhood education and care system is key to facilitate women’s participation in the labour market and reduce gender gaps. Mexico has made progress in the enrolment of 3-5 years olds but has room to increase enrolment of youngest kids (Figure 4.7). Subsidies put in place to replace the network of childcare facilities (Estancias Infantiles) discontinued by the federal government in 2019 are insufficient to cover the cost, and the number of recipients is relatively small. The Finance Ministry, in cooperation with other ministries and institutions from the federal government, has been for some time analysing different strategies to set up a federal network of childcare facilities, also in coordination with subnational governments and the private sector. Achieving full coverage for children under 6 years old would cost 1.2% of GDP annually, while Mexico currently spends 0.5% of GDP (UN, 2020[13]). While the initiative is still in a planning phase (Table 4.1), public-private collaboration is more advanced in some states. Early education facilities can also be a valuable tool for employers and municipalities to attract and retain employees in high demand. To fully grasp the potential benefits of a childcare system, it is fundamental that, while prioritising low-income workers, all households can access the network over time, including informal workers.

Percentage of children enrolled in education services, 2020 or latest available

Note: LAC is a simple average of Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica.

Source: (OECD, 2023[11]).

Beyond early education, school schedules in elementary schools also have an important bearing on women employment. Reforms in several OECD countries (Box 4.2) attest that extending primary schools schedules can significantly foster mother’s labour force participation, employment and hours worked. Mexico’s own experience with full-day schedules is positive (Cabrera-Hernández et al., 2023[3]). After the federal government discontinued the programme in 2022, full-day primary schools remain in place in 6 states.

|

Past recommendation |

Actions taken since the 2022 survey |

|---|---|

|

Establish a network of childcare facilities, giving priority to low-income households. |

Planning has started |

|

Put in place programmes aimed at reintegrating back to schools those who dropped during the pandemic and provide targeted support and tutoring to those with learning difficulties. |

No action taken |

|

Establish a federal unemployment insurance scheme. |

No action taken |

In 1997, Chile began to implement a national education reform in the public school system that increased weekly hours of instruction without extending the number of school days. For most primary schools, the policy meant changing from a system of half-day shifts to continuous full-day schedules. Impact evaluation of the reform signals an important positive causal effects on mother’s labour force participation, employment, weekly hours worked, and months worked during the year (Berthelon, Kruger and Oyarzún, 2023[14]). According to the evaluation, increasing the share of full-time schools by 30 percentage points would boost mothers’ employment and participation by around 9% during a one-year period. Lower-educated and married mothers benefit the most from the reform. Similarly, after-school programs have also had positive effects on mothers’ employment in Switzerland (Felfe, Lechner and Thiemann, 2016[15]) and shorter schedules lead to lower participation of mothers of elementary school children in Japan (Takaku, 2019[16]).

Promoting the take-up of paternity leave entitlements for fathers would also help. The gender division in the use of parental leave in OECD countries has tended to become more even and is even approaching 50/50 in some countries (e.g. Iceland, Portugal and Sweden). Mexico provides 12 weeks of paid maternity leave and 1 week of paternity leave. Contrary to mothers leave that is financed via the social security system, fathers leave is fully paid by the employer. Fathers’ leave take-up has been low, as there is social stigma, and it is only available to formal workers. Financing the leave entitlement via the social security system, as for mothers in Mexico and for fathers in many OECD countries, could facilitate take-up and break stigmas (OECD, 2017[17]).

Care responsibilities for the elderly also fall disproportionally on women. Gradually expanding elderly formal care services, including both home-based and community-based care, would also contribute to higher female labour market participation. They can also mitigate increases in health spending, as they foster prevention and reduce hospitalizations. The budget impact of covering two million of dependent elderly, out of the 3 million elder dependants existing in Mexico, would be 0.5% of GDP. It would also have a positive impact on job formality, as 800000 formal jobs would be created (UN at al., 2020[18]).

Mexico has made good progress in improving female political representation. The share of women in Congress has been on an increasing trend and now reaches 52%. Conversely, female participation in private company boards, at 7%, is lower than observed in most OECD countries (27% on average). Promoting gender diversity in leadership positions in private companies can contribute to enhance diversity and improve economic outcomes. There is a requirement for listed companies to report on their progress to reduce gender imbalances, but the requirement is frequently unmet. Ensuring that the requirement is met would promote gender equality, as exemplified in several OECD countries, such as Australia or the United Kingdom (ILO, 2020[19]). Increasing gender pay gap transparency in those reports, by including mandatory pay-gap reporting, is a promising avenue to reduce gender pay gaps (OECD, 2021[20]). This is currently required in over half of OECD countries (OECD, 2023[21]). Recently adopted initiatives, such as the creation of the interinstitutional committee for gender equality in financial entities, bringing together 20 institutions from the public and private sectors, and the inclusion of gender indicators in the sustainable taxonomy (see chapter 2), are valuable steps to promote higher gender equality.

Mexico has put in place several important labour market reforms which have started to strengthen labour market inclusiveness. These reforms include changes underlying the updated North American Trade Agreement to enhance conflict resolution, workers’ representation and collective bargaining. 79 new trade unions have been created and more than 30500 collective contracts have been registered, covering more than 7 million workers. A key reform was the creation of new independent and specialized courts, the so-called centres for labour conciliation and registration, to expedite conflict resolution between workers and employers. Four out of five labour conflicts are now resolved in less than 45 days at pre-court level and the average resolution time in courts is now 6.5 months. This implies a resolution of labour disputes that takes 87% less time than with the previous system. The implementation of the reforms also requires efforts by states and municipalities, such as aligning local legislation, strengthening labour inspection, providing legal assistance or collecting and maintaining data on labour-related issues. Progress by states and municipalities is heterogenous and could be facilitated by increasing the use of digital justice tools, which can enable remote access, expedite procedures and reduce costs by standardising and automating processes.

Besides the reforms embedded in the trade agreement, another key reform, agreed with social partners, aimed at reducing fraud in the use of outsourcing. Before the reform, around 20% of formal workers were subcontracted and under an outsourcing scheme. After the reform, subcontracting is only allowed for specialized services that are not part of the main activity of the firm. Subcontracting firms must be officially registered in the Labour Ministry to be able to provide outsourcing services. As a result of the reform, around three million workers shifted employer with an average increase in declared wages of 4.2%. Wage increases were larger in the bottom of the income distribution, with a 42% increase for workers in the first income decile. Other important reforms include a pension reform, also agreed with the private sector, and aimed at widening pensions coverage and entitlements (Box 4.3), a legal change to increase the annual minimum leave entitlement from 6 to 12 days and granting social security rights to domestic workers, which reduces their informality.

Mexico has recently implemented a number of changes to its pension system, as detailed in the 2022 Economic Survey. A key change is the reform of contributory pension system, agreed with the private sector and legislated in 2021. The reform aims at increasing coverage (currently only 30% of the old population gets a pension) and replacement rates. To avoid a detrimental impact on formal job creation for low-wage workers, the reform will be funded with a gradual increase in employers’ contributions, phased in from 2023 to 2030, under a progressive scale (i.e. the contribution is higher for workers with higher wages). The federal government also provides funding in a progressive way, covering 60% of contributions for workers at the bottom of the income distribution and 0% at the top. Employee’s contribution remains unchanged and flat at 1.13%. According to government estimates 80% of formal workers would get access to a pension once the reform is fully implemented, with replacement rates increasing particularly for low-income workers.

A key pending challenge ahead to boost labour market inclusiveness is to reduce informality, which has recently trended down but still affects around 55% of workers. Almost 40% of people live in completely informal households (OECD et al., 2023[22]). Some of the reforms recently implemented, such as the reform to reduce fraud in the use of outsourcing or the special programme targeted at domestic workers, are helping to facilitate job formalization. Jovenes Construyendo el Futuro, an internship programme aimed at aiding unemployed young workers get some working experience, has also good potential to foster formality. Its effectiveness in helping youth to step in and remain in the formal labour market should be part of the ongoing evaluation of the programme. While there is no silver bullet to reduce informality and actions are needed in several areas, as discussed in the 2022 Survey, some of the policy reforms suggested in this Survey could be part of such comprehensive strategy. This includes reducing the regulatory cost and burden of setting up and growing a formal firm (as discussed in chapter 3) and improving human capital (discussed earlier in this chapter). Lengthening school schedules and widening access to early education and childcare would also foster formality, as the reduced schedules and lack of childcare push many women into informal work arrangements, that are often the only solution to combine work and care needs.

Enhancing social protection can also incentivize the transition from informal to formal employment. A good example is the recent reform of contributory pensions, which, by improving the access to more attractive pension benefits, encourage participation in formal employment. In the same vein, improving access and coverage of the social safety net could boost formal employment. This could be achieved by providing income support through the personal income tax system, for example through a negative income tax. For the time being social programmes are fragmented and there is room to improve their coverage of low-income households (OECD, 2022[23]). Channelling the income support programmes run at federal level through the personal income tax would enable better targeting support towards informal and poor workers. It would also foster financial inclusion and reduce the scope for clientelism associated to some social programmes. According to this proposal, all workers would be required to register with the tax authority and file personal income taxes. Those whose revenue is below a defined threshold would be exempt from paying the tax and, conditional on the filing, would instead receive a payment. This payment would decrease gradually as the individual earns more income from work. Mexico’s personal income tax system has a larger coverage than in other Latin American countries (e.g. the income threshold to start paying is set at a multiple of 0.6 the average wage, against a multiple of nearly 2 in Costa Rica or 3 in Colombia), making this proposal feasible. Experience from some OECD countries, such as United States with the earned income tax credit, is positive (Hoynes; Patel, 2017[24]), as it has increased formal participation among groups with lower labour market attachment and it reduced poverty. Continuing efforts to strengthen the enforcement of labour and tax regulations and facilitating the formalisation of firms (see Chapter 3) should also be part of a comprehensive strategy to reduce informality.

|

MAIN FINDINGS |

CHAPTER 4 RECOMMENDATIONS (Key recommendations in bold) |

|---|---|

|

Redoubling efforts to enhance human capital |

|

|

Too many students leave the education system without completing secondary education. There is room to increase education quality and to reduce regional inequalities. |

Identify students in need of support, provide them with targeted tutoring and assess and resolve teachers training needs. Establish robust and systematic mechanisms to evaluate education programmes based on comprehensive and homogeneous statistics. Give a higher weight to education quality in the formula underlying the basic education transfer to states and provide additional funding to states succeeding in improving quality. Use skill anticipation assessments and consult systematically businesses at state level to align university and vocational education and training with labour market demand. Identify which training programmes are most effective in equipping workers with relevant skills and strengthen them. Evaluate scholarships to assess if recipients access formal quality jobs. |

|

Dual vocational programs are being gradually deployed across the countries with positive outcomes in terms of acquired skills. |

Reserve a share of scholarships for dual vocational programmes and set up institutional arrangements enabling SMEs to participate in training activities. |

|

Increasing gender equality |

|

|

Despite a recent increase, female labour force participation, at 50%, lags participation in OECD and other Latin America countries. Domestic and care responsibilities fall disproportionally on women |

Establish a federal network of early education and care facilities giving priority to low-income households. Increase the number of primary schools providing full-day schedules. Expand elderly formal care services, including home-based and community-based care. |

|

Excessively long working hours hinder female access to the job market. |

Promote the use of flexible work hours, temporary part-time work for family reasons and remote work. |

|

Mexico provides 12 weeks of paid maternity leave and 1 week of paternity leave. The take-up of paternity leave is low. The leave is fully paid by employers. |

Lengthen fathers’ paid leave entitlement and finance it via the Social Security System. |

|

Female political representation has improved notably but there is room for increasing female participation in private company boards. |

Introduce a mandatory reporting of pay-gap for listed companies. Ensure the requirement for listed companies to report on progress to reduce gender imbalances is met. |

|

Continuing to boost labour market inclusiveness |

|

|

Mexico has implemented labour reforms to enhance conflict resolution workers representation and collective bargaining. Reforms are paying off. Implementation efforts at state and municipal level are heterogenous. |

Fully implement the labour reforms at state and municipal level, for example by increasing the use of digital justice tools. |

|

55% of workers are informal, hindering well-being and productivity. |

Pursue a comprehensive strategy to reduce informality, including by providing income support to low-income households through the personal income tax or reducing firms registration and licensing costs at state and municipal level. |

[5] Abdul-Hamid, H. (2017), “Data for Learning: Building a Smart Education Data System. Washington, World Bank Group.”, Washington, World Bank Group..

[14] Berthelon, M., D. Kruger and M. Oyarzún (2023), “School schedules and mothers’ employment: evidence from an education reform”, Review of Economics of the Household, Vol. 21/1, pp. 131-171, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09599-6.

[3] Cabrera-Hernández et al. (2023), “Full-time schools and educational trajectories: Evidence from high-stakes exams”, Economics of Education Review, Vol. 96, p. 102443, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2023.102443.

[1] CONEVAL (2023), “Medición de Pobreza 2022”.

[4] CONEVAL (2018), “Impacto de Programa Escuelas de Tiempo Completo 2018.”.

[15] Felfe, C., M. Lechner and P. Thiemann (2016), “After-school care and parents’ labor supply”, Labour Economics, Vol. 42/C, pp. 64-75, https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:labeco:v:42:y:2016:i:c:p:64-75.

[24] Hoynes; Patel (2017), “Effective Policy for Reducing Poverty and Inequality?””, Journal of Human Resources.

[19] ILO (2020), Women in business and management: improving gender diversity in company boards (voluntary targets vs quotas).

[9] IMCO (2023), “El panorama de las vacantes y la población disponible en México”.

[12] INEGI (2021), Encuesta para la Medición del Impacto COVID-19 en la Educación (ECOVID-ED) 2020, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía.

[11] OECD (2023), Joining Forces for Gender Equality: What is Holding us Back?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/67d48024-en.

[2] OECD (2023), “PISA 2022 Results: Factsheets. Mexico Country Note”.

[21] OECD (2023), Reporting Gender Pay Gaps in OECD Countries: Guidance for Pay Transparency Implementation, Monitoring and Reform, OECD, Paris.

[23] OECD (2022), “OECD Economic Surveys: Mexico 2022”.

[6] OECD (2021), OECD Digital Education Outlook 2021: Pushing the Frontiers with Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain and Robots, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/589b283f-en.

[20] OECD (2021), Show me the Money : Pay Transparency Policies to Close the Gender Wage Gap, OECD Publishing.

[8] OECD (2018), “OECD Economic Surveys: Brazil 2018”.

[17] OECD (2017), “Building an Inclusive Mexico: Policies and Good Governance for Gender Equality”, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[7] OECD (2011), “OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Norway”.

[22] OECD et al. (2023), “Latin America Economic Outlook”.

[10] SEP (2023), “Consolidación y escalamiento del sistema de educación dual en México. Resultados de la Encuesta de Monitoreo y Evaluación 2022-2023”, Secretaria de Educación Pública; Sistema de Educación Dual Superior; Cooperación Alemana; GIZ.

[16] Takaku, R. (2019), “The wall for mothers with first graders: availability of afterschool childcare and continuity of maternal labor supply in Japan”, Review of Economics of the Household, Vol. 17/1, pp. 177-199, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-017-9394-9.

[13] UN (2020), Costos, retornos y efectos de un Sistema de cuidado infantil universal, gratuito y de calidad en México, ONU Mujeres and CEPAL, https://www2.unwomen.org/-/media/field%20office%20mexico/documentos/publicaciones/2020/diciembre%202020/twopager_cepal_onumujeres_esp.pdf?la=es&vs=2542 (accessed on 11 October 2021).

[18] UN at al. (2020), “El cuidado de las personas mayores en situación de dependencia en México: propuesta de servicios, estimación preliminar de costos e identificación de impactos económicos.”, United Nations Mexico, Joint SDG Fund, INMUJERES, CEPAL and United Nations Women.