From an international perspective, New Zealand fares well in several aspects of current well-being, but faces challenges in housing affordability, household income and earnings, mental health, and child well-being. There are also large inequalities for health and educational outcomes, and a high share of economically vulnerable people. Social capital is a particular strength, but New Zealand’s natural assets are being depleted. The Treasury has developed its Living Standards Framework and associated Dashboard to integrate well-being evidence more systematically in its advice to the Government. The Dashboard is consistent with international measurement practice, but has some indicator gaps, particularly for natural capital. The New Zealand Government is applying a well-being approach to policy and budget decision-making, including legislating for well-being objective-setting and reporting. Continuing to develop the evidence base that supports the well-being approach is critical. Effective implementation requires further investment in methodological development, civil service capacity-building, and strong leadership across government.

OECD Economic Surveys: New Zealand 2019

Chapter 1. Well-being: performance, measurement and policy innovations

Abstract

Introduction

The past decade has seen increasing interest in using well-being evidence in a more systematic way to support policy making. Evidence-informed policy is core practice in OECD countries, yet all governments struggle to integrate evidence effectively across the wide range of well-being outcomes that matter to people. An emphasis on GDP growth, economic efficiency, and managing fiscal pressures can mean that the wider impacts of policies on people’s lives - including household living standards, social and environmental outcomes - are often less systematically quantified and assessed. The sustainability of outcomes over time, and their distribution across the population, also often get less focus than shorter-term and aggregate outcomes. And although much policy evidence goes well beyond the analysis of economic and fiscal impacts (for example in health, education and environmental spheres), this is often constrained by departmental silos. This means that policy trade-offs are not always well evidenced and debated, and there are missed opportunities for synergies across policy settings. As a result, opportunities for efficiency savings are lost, priority-setting is less well-informed, and accountability for the broader impact of policy on people’s lives is reduced.

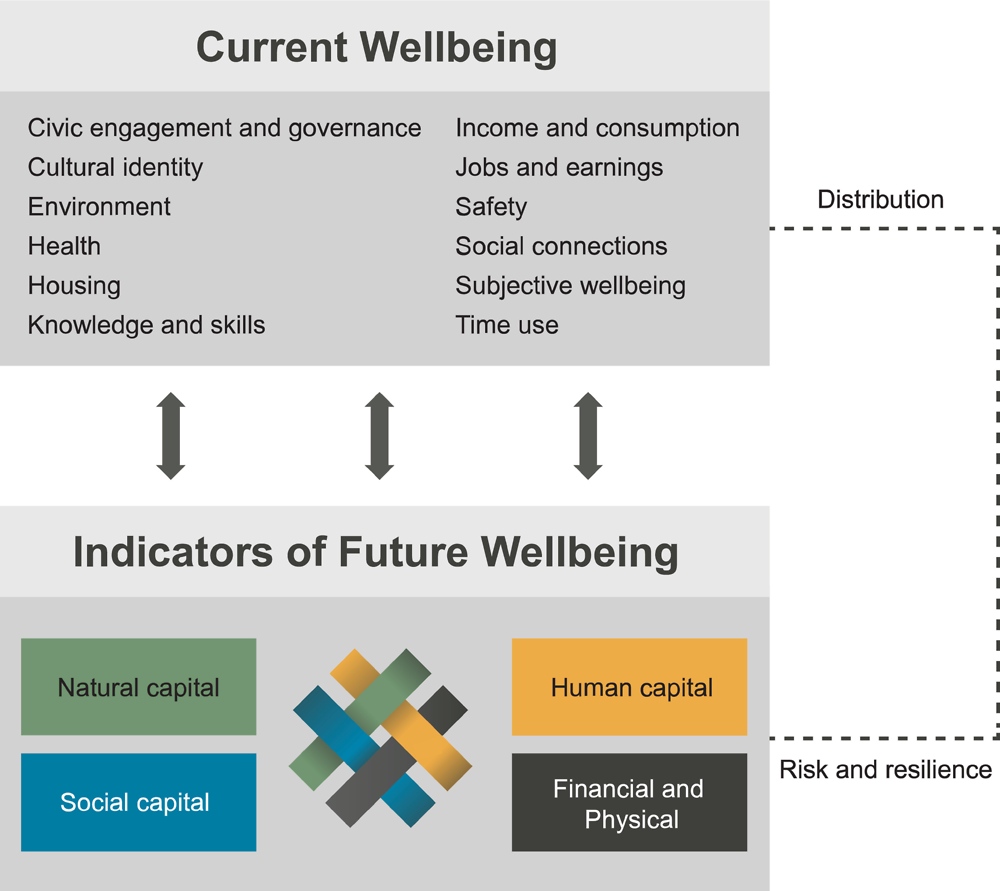

In recognition of these challenges, the New Zealand Treasury began to develop a Living Standards Framework in 2011 (Figure 1.1 shows the most recent version). Its primary aim is to improve the depth, breadth and quality of Treasury’s policy advice to current and future Governments (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[1]), prompting analysts to consider the broad well-being impacts of policy options. The Living Standards Framework has supported the current Government’s strategic emphasis on improving the well-being of New Zealanders and their families (New Zealand Government, 2018[2]). Nevertheless, the Framework remains first and foremost a tool developed by and for Treasury analysts, to provide high quality policy advice in the context of the priorities set by the government of the day.

Figure 1.1. New Zealand Treasury’s Living Standards Framework, 2018 edition

Source: New Zealand Treasury (2018), Living Standards Framework: Introducing the Dashboard, https://treasury.govt.nz/publications/tp/living-standards-framework-introducing-dashboard

Measurement challenges hinder people-centred policy analysis, but high-quality and internationally comparable measures of well-being and sustainability are increasingly becoming part of national statistical practice in OECD countries. Since the early 2000s, several governments have developed multidimensional frameworks and dashboards of well-being indicators. In New Zealand, measures of well-being have been collected in various forms for nearly two decades. In December 2018, the Treasury publicly released its first Living Standards Framework Dashboard, with 55 indicators spanning the dimensions shown in Figure 1.1 (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[3]). Quantifying well-being outcomes can raise their profile in public policy debates, but frameworks and measurement initiatives are only the first step in building and applying a broader evidence base to policy. The challenge now faced by governments is how to embed well-being evidence more systematically throughout policy decision making, including in budgets, cabinet committees and other routine processes, such as policy evaluation. Recent applications of the Living Standards Framework, including through a “Wellbeing Budget” in 2019, are important steps in this direction.

This chapter examines the use of well-being frameworks and evidence as tools for better policy-making, and offers recommendations for New Zealand in three key areas. The first relates to opportunities for raising well-being in New Zealand, as viewed from an international perspective. The second concerns the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework and measurement Dashboard, exploring how these compare to other initiatives internationally, as well as New Zealand’s current policy priorities. The third addresses integrating the Living Standards Framework more systematically into the machinery of government, to improve the evidence base and how policy advice is generated and used.

New Zealand’s well-being in an international context

Improving the well-being of New Zealanders and their families is one of three strategic priorities for the coalition government (New Zealand Government, 2018[2]), alongside building a productive, sustainable and inclusive economy, and providing new leadership by government. Applying the OECD approach to measuring well-being (OECD, 2017[4]; OECD, 2011[5]), this section offers an international perspective on opportunities to raise New Zealander’s outcomes from three different viewpoints: comparative current levels, trends since 2005, and the size of inequalities relative to those observed in other OECD countries. It also discusses how the priorities selected for the 2019 Budget align with this international analysis.

The big picture on New Zealand’s well-being

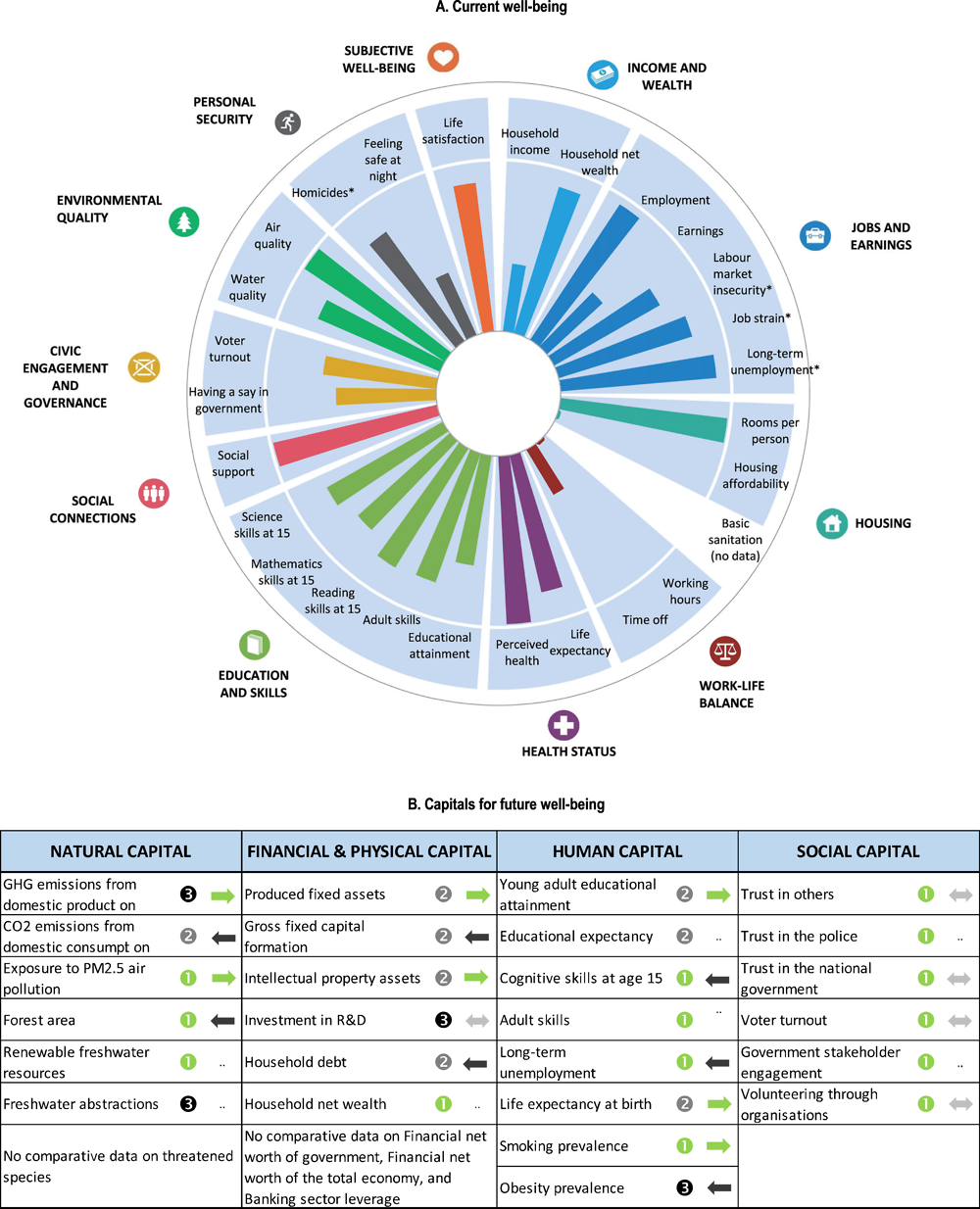

The OECD’s How’s Life? framework measures well-being through a set of more than 50 indicators (Figure 1.2). These are drawn from nationally representative data, generally sourced from national statistical office or OECD datasets. The majority of indicators are based on objective data, used to capture aspects of people’s living conditions today and the four capitals (financial and physical, natural, social and human) that help to sustain well-being over time. These are complemented by a limited number of subjective measures, such as life satisfaction, to take into account how people experience their lives.

Relative to other OECD countries, New Zealand performs well across several headline indicators of the How’s Life? framework (Figure 1.2).1 Nevertheless, there is still room for improvement, and some negative trends need to be counteracted. Good average performance sometimes also masks well-being inequalities that are larger than the OECD average.

Figure 1.2. On average, New Zealand performs well on several OECD How’s Life? indicators

Note: This chart shows New Zealand’s relative strengths and weaknesses in well-being compared with other OECD countries. For the current well-being wheel, for both positive and negative indicators (marked with an “*”), longer bars always indicate higher well-being. No comparative data is available on basic sanitation. For the future well-being dashboard: = top-performing OECD tier, = middle-performing OECD tier, = bottom-performing OECD tier. Change is shown from 2005 to the latest available year, which is generally 2016. Forward arrows (in green) signify improvement over time, backward arrows (in black) indicate worsening, and level arrows (grey) indicate little change. Missing time trend data is indicated as “..”.

Source: Adapted from OECD How’s Life? 2017 (2017[4]) unless otherwise indicated in the StatLink.

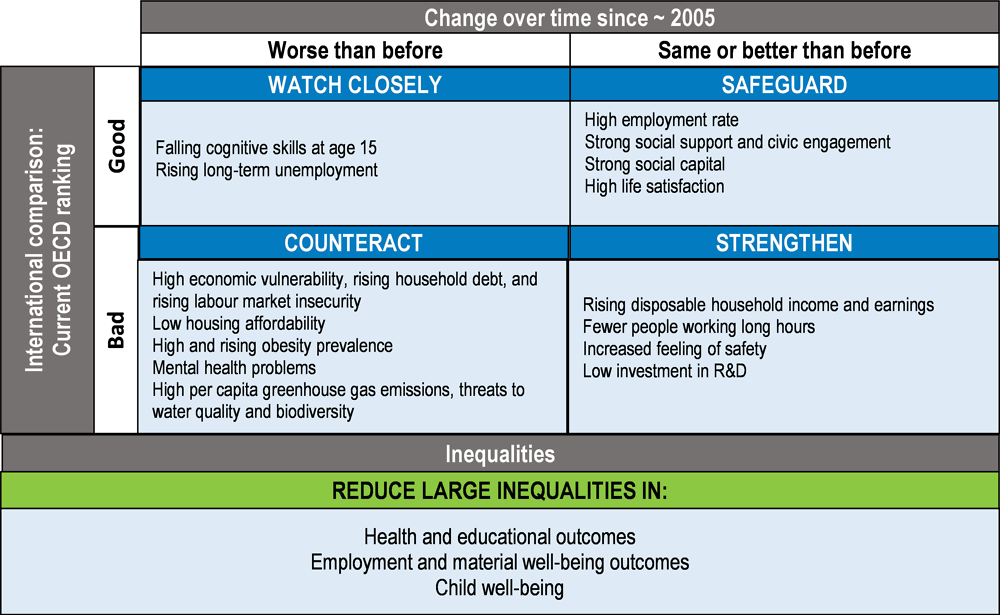

Combining comparative well-being performance with data on changes since 2005, and the distribution of outcomes across population groups, can inform priorities for policy action (Figure 1.3). Outcomes to safeguard are those where New Zealand performs well internationally, and recent changes have been either positive or stable (top right quadrant). These include a comparatively high employment rate, strong social capital and civic outcomes, and good air quality. In other areas, New Zealand starts from a comparatively lower base but has made progress in recent years which requires further strengthening (bottom right). This includes rising household disposable income and earnings, fewer people working very long hours, growing investment in research and development, and increases in people’s feelings of safety. A companion paper (Fleischer, Frieling and Exton, forthcoming[6]) discusses these in greater detail.

Figure 1.3. Opportunities for improving New Zealand’s well-being: an international perspective using the OECD approach

Note: OECD time series data are not available for all indicators, including renewable freshwater resources, freshwater abstractions, threatened species, household net wealth, adult skills, educational expectancy, trust in the police and government stakeholder engagement. These indicators have therefore not been included here.

Indicators in which New Zealand still ranks well but has lost ground over the past decade should be watched closely (top left). They include rising long-term unemployment and falling cognitive skills at age 15. Areas of poor and worsened performance require urgent action to counteract them (bottom left). This includes low and worsening housing affordability, high economic vulnerability, rising household debt, high per capita greenhouse gas emissions, high and rising obesity rates, and mental health problems. New Zealand’s water quality and biodiversity are also under threat (OECD, 2017[7]). Analysis of inequalities points to the importance of reducing gaps in health and educational outcomes, which are particularly high by international standards, as well as child well-being, and large ethnic differences in a broad range of well-being dimensions.

Key opportunities for improving New Zealand’s well-being

Reduce health inequalities, and address mental health and obesity challenges

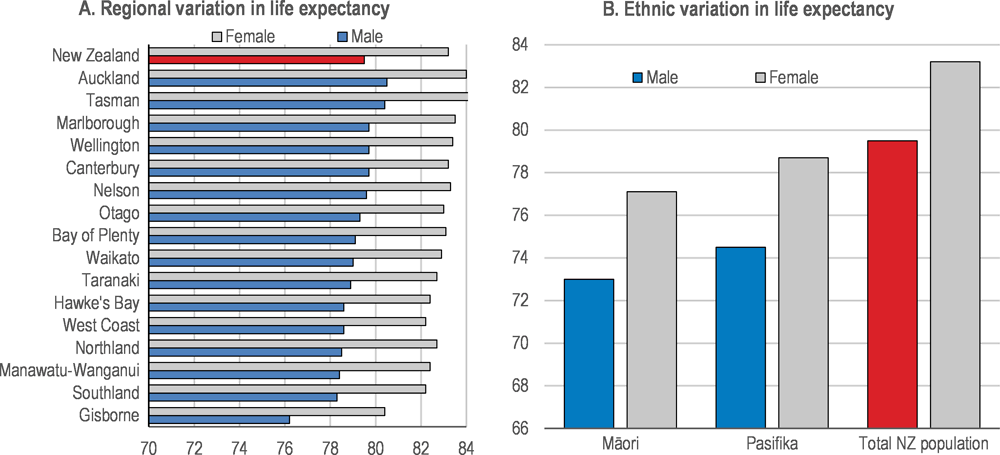

88% of New Zealanders report being in good health, and life expectancy is about 1.5 years above the OECD average. Nevertheless, inequalities in life expectancy, measured as the standard deviation in age of death, are among the largest in the OECD (OECD, 2017[4]). Life expectancy varies considerably between regions and ethnic groups (Figure 1.4). Rates of amenable mortality - i.e. deaths under age 75 that could potentially be avoided given effective and timely healthcare - are about 2.5 times higher for Māori and Pasifika than for the rest of the population (Ministry of Health, 2017[8]).

Figure 1.4. Inequalities in health outcomes in New Zealand

Median years of life, average 2012-14

Source: Stats NZ, New Zealand Period Life Tables 2012-14, http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/health/life_expectancy/NZLifeTables_HOTP12-14.aspx.

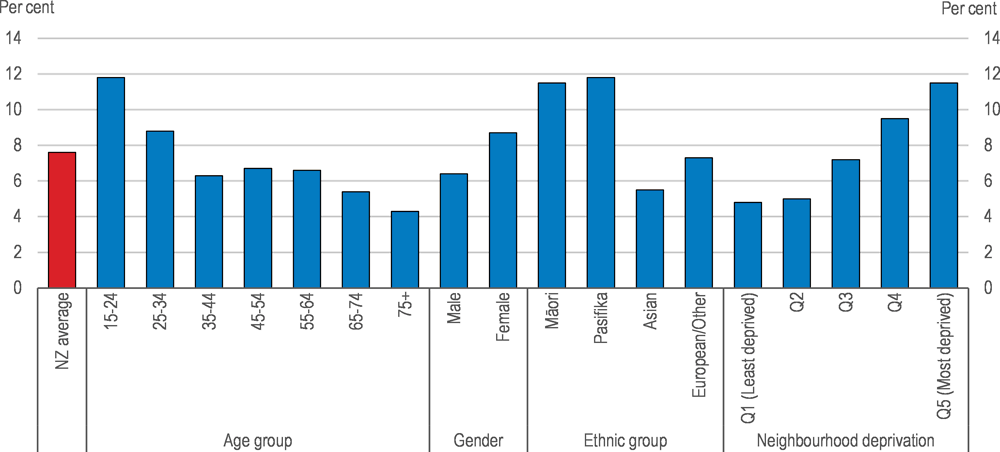

Between 2006 and 2017, New Zealand’s prevalence of serious non-fatal intentional self-harm injuries increased substantially (to 5.3 per 100 000 people, up from 3.1 in 2006) and provisional data indicate an increase in suicides between 2015 and 2017 (Stats NZ, 2018[9]). New Zealand’s overall suicide rate is close to the OECD average (OECD, 2019[10]; Stats NZ, 2018[9]), but its teenage suicide rate is among the highest in the OECD (discussed below). Mental health risk in New Zealand varies considerably with age, gender, ethnicity, and neighbourhood conditions (Figure 1.5): people living in the most socio-economically deprived areas are nearly three times more likely to report having experienced psychological distress in the past four weeks than people in the least deprived areas (adjusting for age, sex and ethnicity differences among neighbourhoods).

Figure 1.5. Large variation in the prevalence of psychological distress in New Zealand

Share of the population with “(very) high” probability of anxiety or depressive disorder, K10 score ≥ 12

Note: Unadjusted prevalence rates for each group. Ethnic groups are based on total response groups, meaning that each person has been allocated to all ethnic groups that they have identified with.

Source: Ministry of Health, Annual Data Explorer 2016/17, https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2016-17-annual-data-explorer.

In contrast with its low overall smoking prevalence (OECD, 2017[4]), New Zealand has the third highest adult obesity rate in the OECD, rising from 27% in 2006/07 to 32% in 2017/18 (Ministry of Health, 2019[11]). The prevalence of key health risks including obesity, physical inactivity and smoking is higher among Māori, Pasifika and people living in socio-economically deprived areas (Ministry of Health, 2017[12]).

Improve well-being for children and youth

New Zealand’s child poverty rate (based on a threshold set at half of the median income of each country, before housing costs) was 16.5% in 2018 (Stats NZ, 2019[13]), three percentage points above the OECD average in 2016 (OECD, 2019[14]). Rates are higher among Māori and Pasifika children, as well as for those living in sole-parent or jobless households (Ministry of Social Development, 2017[15]). Children in New Zealand are disproportionately affected by household crowding, with 16% of 0-19 year-olds living in crowded houses in 2013, as compared to a 10 % population average (Stats NZ, 2019[16]).

Child health concerns include a relatively high teenage birth rate (16 per 1000 women aged 15-19 in 2016, compared to an OECD average of 12.4 (OECD, 2018[17]), and high rates of obesity in children aged 2-14 years - which have risen from 8% in 2006/7 to 12% in 2016/17 (Ministry of Health, 2017[12]). New Zealand’s suicide rate among young people aged 15-19 is over three times higher than the OECD average, and has increased by one third since 2000, counter to the OECD average fall of nearly 15% (OECD, 2017[18]).

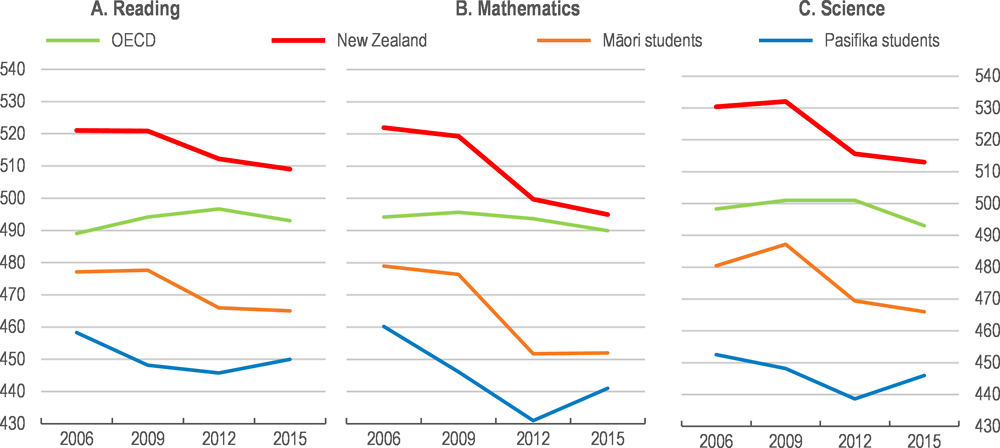

Cognitive skills of students at age 15 fell between 2006 and 2015, and educational inequalities are wide (Figure 1.6). In general, the gap in achievement between students from advantaged and disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds is relatively large in New Zealand (May, Flockton and Kirkham, 2016[19]). Other student outcomes are also worrying: in 2015, New Zealand had the second worst score on the OECD Index of Exposure to Bullying, with 18% of students reporting frequent instances of being bullied. New Zealand students have also reported a weakening sense of belonging in school since 2003 (OECD, 2017[20]; TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, 2016[21])

figure 1.6. Average cognitive skills for students aged 15 have fallen in New Zealand

Source: OECD, PISA Results, various years; S. May, J. Flockton and S. Kirkham (2016), PISA 2015 - New Zealand Summary Report, Ministry of Education.

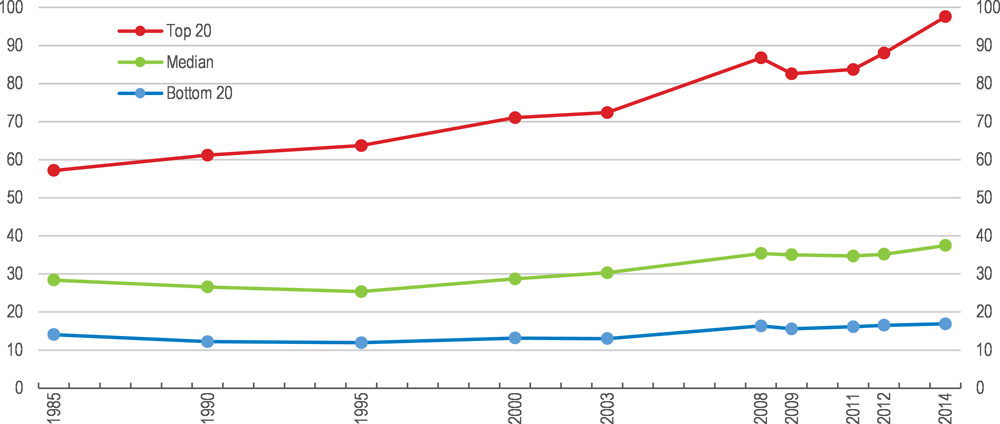

Secure better material conditions for all and reduce high economic vulnerability

Income inequalities in New Zealand have increased since the mid-1980s (Figure 1.7). Disposable income for New Zealand’s top income quintile is 5.8 times larger than that for the bottom quintile (OECD, 2017[22]).2 Between 2015 and 2018, the net worth of the richest 20% of New Zealand households increased (by NZD 394 000), while that of the bottom 40% did not change (Stats NZ, 2018[23]). In 2015, the age-standardised median net wealth of New Zealand Europeans was more than three times higher than that of the Asian population, five times that of Māori, and nine times that of Pasifika - though collective assets, such as Māori land and trusts, are not well captured by these statistics (Stats NZ, 2016[24]).

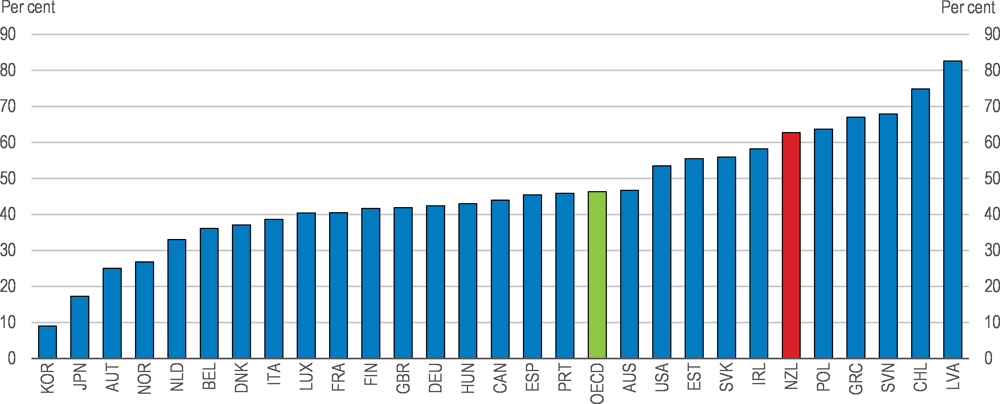

Compared to other OECD countries, the economic vulnerability of individuals is high: nearly two thirds of New Zealanders would be at risk of falling into poverty if they had to forgo three months of their income (Figure 1.8). Poor housing affordability in New Zealand (OECD, 2017[4]) further aggravates these vulnerabilities, with the burden disproportionately falling on those with lower incomes. Low-income households are less likely to own their home, and the majority of low-income renters now spend more than 40% of their gross income on housing (Chapter 3). Household debt as a share of income increased from 99% in 1998 to 164% in 2018 (Reserve Bank of New Zealand, 2019[25]).

Figure 1.7. Incomes for the top 20% have far outpaced the rest

Real annual equivalised household disposable income, thousand 2010 NZD

Note: Households’ annual equivalised disposable income is calculated as the income of each household adjusted by the square root of household size. The figure shows absolute levels of median income as well as averages for people in the top 20% and the bottom 20% of the income distribution. This differs from the approach taken in the Living Standards Framework Dashboard, which reports income by percentiles. Data collections have been carried out periodically since 1985; the horizontal access indicates the years for which data are available.

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Income Distribution database, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=IDD.

Figure 1.8. Asset-based poverty

Share of individuals with liquid financial wealth below 3 months (25%) of the national annual income poverty line, 2015 or latest available year

Source: Balestra, C. and R. Tonkin (2018), “Inequalities in household wealth across OECD countries: Evidence from the OECD Wealth Distribution Database”, OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2018/01, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/7e1bf673-en.

New Zealand has a high level of employment, and a low rate of long-term unemployment. Nevertheless, both long-term unemployment and labour market insecurity increased following the global financial crisis, and have not yet returned to pre-crisis levels (OECD, 2017[22]), consistent with wider OECD trends. In 2018, the number of New Zealanders unemployed for over one year was four times higher than in 2008 (Stats NZ, 2018[26]), while labour market insecurity was 70% higher in 2015 than in 2007 (OECD, 2017[4]).

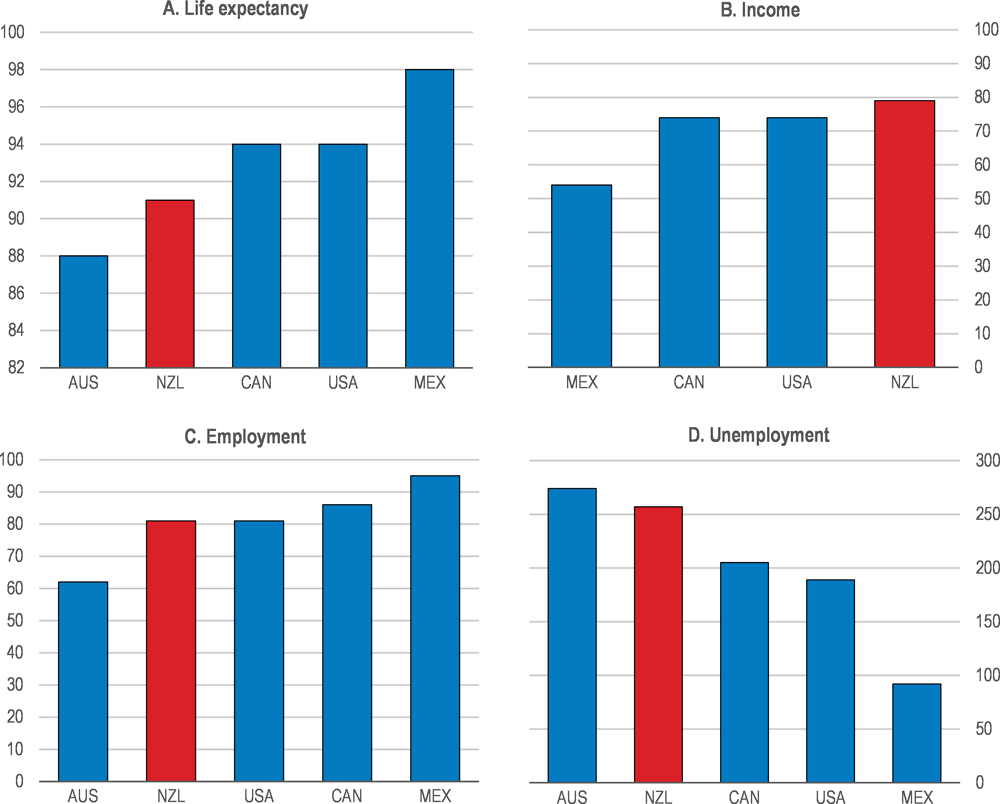

Raise outcomes for Māori

Gaps between Māori and non-Māori on life expectancy, employment and unemployment are larger than gaps between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples in Canada, the United States and Mexico (Figure 1.9).3 Over the last intercensal period (2006-2013 in New Zealand) the differences between Māori and non-Māori widened for income, employment, unemployment and upper secondary educational attainment, while many of these gaps were shrinking in other OECD countries (OECD, 2019[27]).

The Treasury’s Living Standards Framework Dashboard provides an analysis of outcomes for four major population groups (European, Māori, Pacific, and Asian), each of which have different profiles of well-being strengths and challenges (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[28]). For example, New Zealand Europeans report high levels of cultural identity (feeling they are able to be themselves in New Zealand), and have comparatively high housing, income and consumption outcomes. Although Māori experience lower well-being across most domains, differences in cultural identity for Māori are relatively small. Asians fare well on knowledge and skills, health, and safety, but have lower housing, income and consumption outcomes, and feel less able to be themselves in New Zealand. Pacific people report high social connections and subjective well-being, but poor housing, income and consumption, and cultural identity outcomes. Addressing inequalities and better understanding the requirements for strong well-being will be important for sustaining New Zealand’s well-being over time, as Māori, Pasifika and Asians are projected to make up an increasing proportion of New Zealand’s population over the next 20 years (Stats NZ, 2017[29]).

Figure 1.9. Māori fare better than other OECD indigenous peoples on income gaps, but often worse on life expectancy, employment and unemployment gaps

Values show indigenous levels as a percentage of non-indigenous levels

Note: The life expectancy rate of Indigenous Canadians is the weighted average of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women and men. Median income refers to total personal income for Canada; median household income for Mexico; median personal income for New Zealand; and median earnings for the United States. Non-Indigenous peoples’ income corresponds to the median earnings of the total population for the United States. Employment and unemployment refer to people aged 15-64, as a percentage of the population of the same age, except for Canada where it refers to populations aged 15 and over.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2019), Linking Indigenous Communities to Regional Development, OECD Publishing, Paris. See StatLink for data sources and reference years.

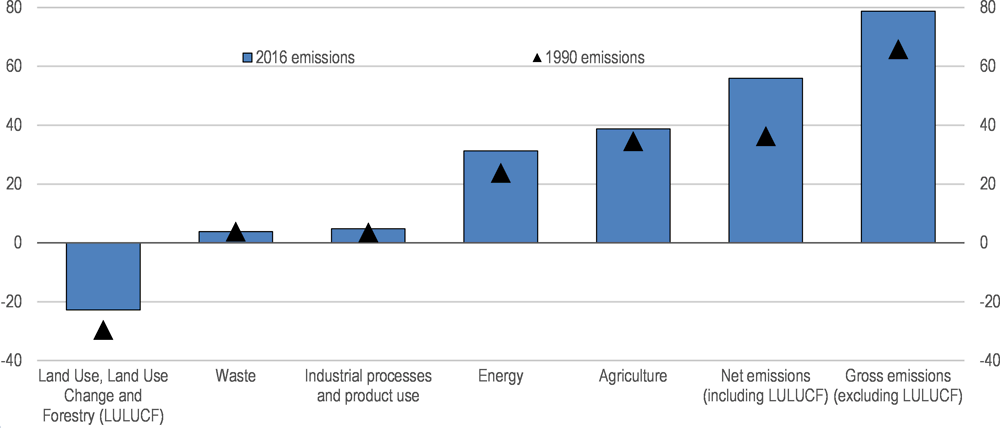

Curtail greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity loss; improve water quality

The natural environment is an essential part of New Zealand’s national identity, receiving a top rating from New Zealanders in terms of its importance in defining their country (Stats NZ, 2017[30]). New Zealand’s air quality is very good by international standards and has improved over the past decade, driven mainly by a shift to cleaner home heating (Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ, 2018[31]) (OECD, 2018[32]). However, expansion of primary production over the past decades, in particular dairy farming, has increased net greenhouse gas emissions since 1990 (Figure 1.10), freshwater contamination, and threats to biodiversity (OECD, 2017[7]). High rates of population growth are placing further pressure on the environment, particularly in urban areas.

Figure 1.10. New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions by sector

Megatons CO2-equivalent

Note: Net emissions from the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) sector are shown as a negative number because the sector removes more CO2 from the atmosphere than it emits. Columns may not sum up to the total due to rounding. Percentages are calculated from unrounded values.

Source: Ministry for the Environment (2018), New Zealand’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory: 1990-2016, mfe.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media/Climate%20Change/final_greenhouse_gas_inventory_snapshot.pdf

New Zealand’s gross greenhouse gas emissions per capita and per unit of GDP are among the five highest in the OECD, largely due to its sizeable agricultural sector which accounts for nearly half of New Zealand’s total emissions (OECD, 2019[33]). New Zealand forests offset just under a third of its gross emissions. Net emissions increased by 54% between 1990 and 2016 (Figure 1.10), as more forests were harvested, fewer trees were planted, and gross emissions rose (Ministry for the Environment, 2019[34]).

The 2019 Budget priorities and the international evidence on well-being

Five priorities for New Zealand’s first well-being budget were set out in the 2019 Budget Policy Statement (New Zealand Government, 2018[35]):

Creating opportunities for productive businesses, regions, iwi (Māori tribes) and others to transition to a sustainable and low-emissions economy;

Supporting a thriving nation in the digital age through innovation, social and economic opportunities;

Lifting Māori and Pasifika incomes, skills and opportunities;

Reducing child poverty and improving child well-being, including addressing family violence;

Supporting mental well-being for all New Zealanders, with a special focus on under 24-year-olds.

The budget priorities were developed through analysis of New Zealand well-being evidence, in consultation with Chief Science Advisors, and sector experts. They are in line with some of the well-being challenges identified through comparison with other OECD countries (e.g. Figure 1.3). The first budget priority addresses the urgency to counteract New Zealand’s high per capita greenhouse gas emissions and deteriorating natural capital. The second resonates with the identified need to strengthen investment in research and development. The third priority responds to the large ethnic inequalities in well-being outcomes in New Zealand. The fourth and fifth priorities are in line with the finding that child well-being and mental health are areas of high concern for New Zealand. However, many of these priorities reflect long-term systemic challenges that are unlikely to be reversed by a single short-term funding injection. Consideration must therefore be given to what can be done to foster better outcomes on a longer-term basis, through both budgetary and non-budgetary mechanisms.

While prioritisation means focusing on a relatively narrow set of issues, international evidence points to other opportunities to raise New Zealand’s well-being, in addition to those identified in the 2019 Budget priorities. For example, housing affordability is not explicitly mentioned in the five priorities – although the government has argued that better housing will be a key mechanism for delivering the priorities (Institute of Public Administration New Zealand, 2019[36]) and has several ongoing initiatives to address this (Chapter 3). New Zealand’s comparatively high rates of economic vulnerability, rising labour-market insecurity, and falling cognitive skills among students at age 15 are also not directly considered among the budget priorities, nor are high rates of obesity and large health disparities – though many of these outcomes are interrelated with the priorities selected. Ethnic inequalities are in need of urgent attention, but there are also other fault lines in New Zealand’s well-being, including challenges faced by people in low-income households and single-parents. One test of the five budget priorities will be the extent to which they drive programmes that have positive spill-overs for these other well-being outcomes, which would indicate that efficient and effective policy levers have been selected.

New Zealand’s Living Standards Framework from an international perspective

Frameworks for well-being in OECD countries

New Zealand Treasury’s Living Standards Framework, launched in 2011, was one of the earliest well-being policy frameworks to be developed among OECD countries. In December 2018, the Treasury publicly released its Living Standards Framework Dashboard, which operationalises the conceptual framework through a concrete set of indicators (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[37]). Information in the Dashboard is organised on three different levels: current well-being among different population groups, which also considers the relationships between well-being domains (our people); trends over time and international comparisons (our country); and the four capitals (our future) (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[3]). This builds on a long history of well-being measurement across the New Zealand Government more broadly (Box 1.1).

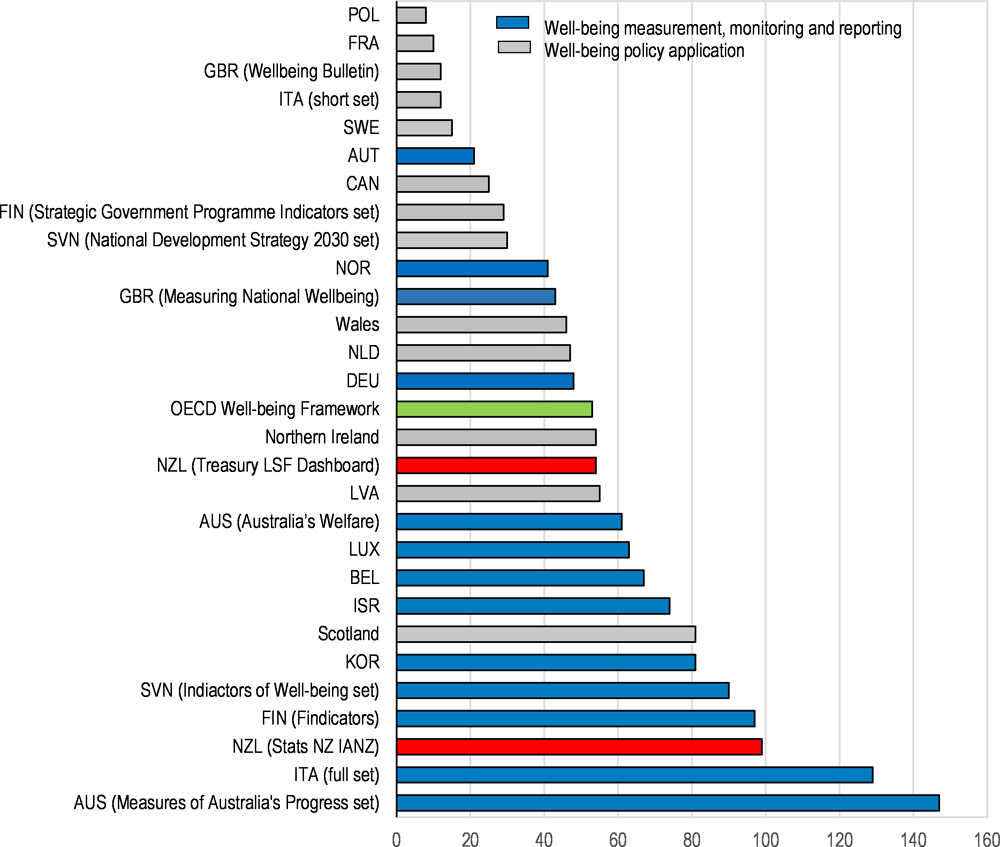

Among other OECD countries, a general distinction can be made between frameworks focused on the measurement, monitoring and reporting of well-being (often, but not exclusively, led by national statistical offices), and those developed to support more direct policy applications (often led by treasuries, or other central bodies such as the Prime Minister’s Office) (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. National well-being frameworks across the OECD, selected countries

|

Lead body |

Launch year |

Public consultation |

Number of dimensions |

Number of indicators |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OECD Well-being Framework |

OECD |

2011 |

15 |

53 |

|

|

Well-being measurement, monitoring and reporting |

|||||

|

Measures of Australia’s Progress |

Australian Bureau of Statistics |

2002 |

✓ |

26 |

147 |

|

Australia’s Welfare |

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare |

2015 |

19 |

61 |

|

|

How’s Austria? |

Statistics Austria |

2012 |

3 |

21 |

|

|

Belgium Complementary Indicators to GDP |

National Accounts Institute + Federal Planning Bureau |

2016 |

13 |

67 |

|

|

Belgium Sustainable Development Indicators |

Federal Planning Bureau |

2019 |

17 |

70 |

|

|

Finland Findicators |

Statistics Finland |

2009 |

12 |

97 |

|

|

Well-being in Germany |

Federal Chancellery |

2016 |

✓ |

11 |

48 |

|

Italy Measures of Equitable and Sustainable Well-being (full set) |

National Institute of Statistics + National Council for the Economy and Labour |

2013 |

✓ |

12 |

129 |

|

Israel Well-being, Sustainability and National Resilience Indicators |

Central Bureau of Statistics |

2015 |

✓ |

11 |

88 |

|

Korea Quality of Life Indicators |

Statistics Korea |

2014 |

12 |

81 |

|

|

Luxembourg Index of Well-being |

Statec, Economic and Social Council + the Higher Council for Sustainable Development |

2017 |

✓ |

11 |

63 |

|

Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand |

Stats NZ |

(forthcoming) |

✓ |

24 |

99 |

|

Norway - How We Are Doing |

Statistics Norway |

2017 |

10 |

41 |

|

|

Indicators of Well-being in Slovenia |

Institute of Macroeconomic Analysis and Development, Statistics Slovenia, Slovenian Environment Agency + National Institute of Public Health |

2015 |

✓ |

20 |

90 |

|

United Kingdom Measures of National Well-being |

The UK Office for National Statistics |

2011 |

✓ |

10 |

43 |

|

Well-being policy application |

|||||

|

Australian Treasury's Well-being Framework |

Treasury |

2004 |

5 |

N/A |

|

|

Canadian Federal Sustainable Development Strategy |

Minister of Environment and Climate Change |

2008 |

✓ |

13 |

25 |

|

Finland Strategic Government Programme Indicators |

Prime Minister’s Office |

2015 |

5 |

29 |

|

|

France New Indicators of Wealth |

Prime Minister’s Office |

2015 |

✓ |

3 |

10 |

|

Italy Measures of Equitable and Sustainable Well-being (short set) |

Ministry of Economics and Finance |

2016 |

✓ |

8 |

12 |

|

Latvia 2030 |

Cross-Sectoral Coordination Centre, under the authority of the Prime Minister |

2010 |

✓ |

7 |

55 |

|

Netherlands Monitor of Well-being |

Netherlands Cabinet + Statistics Netherlands |

2017 |

15 |

47 |

|

|

New Zealand Living Standards Framework Dashboard |

Treasury |

2011/18 |

✓ |

16 |

55 |

|

Northern Ireland Outcomes Delivery Plan |

Northern Ireland Executive Office |

2018 |

12 |

54 |

|

|

Poland Responsible Development Index |

Polish Economic Institute |

2019 |

3 |

8 |

|

|

Scotland National Performance Framework |

Scottish Government |

2007 |

✓ |

11 |

81 |

|

Slovenia National Development Strategy 2030 |

Slovenian Government |

2017 |

✓ |

12 |

30 |

|

Sweden New Measures of Well-being |

Ministry of Finance |

2017 |

15 |

15 |

|

|

United Kingdom Personal and Economic Well-being bulletin |

Office for National Statistics |

2019 |

2 |

12 |

|

|

Well-being of Wales |

National Assembly for Wales + Welsh Government Chief Statistician |

2015 |

✓ |

7 |

46 |

Note: Launch time refers to the actual release of a framework, rather than commissioning of its development. Number of indicators refers to the dashboards as of May 2019. Measures of Australia’s Progress was discontinued in 2013, and the Australian Treasury’s Well-being Framework in 2016. Australia’s Welfare reports have been published since 1993. The Canadian Federal Sustainable Development Strategy refers to the 2016-19 version. The Scottish Government’s National Performance Framework was first launched in 2007; the number of dimensions and indicators refers to the refreshed 2018 edition.

Source: Exton and Shinwell (2018[38])

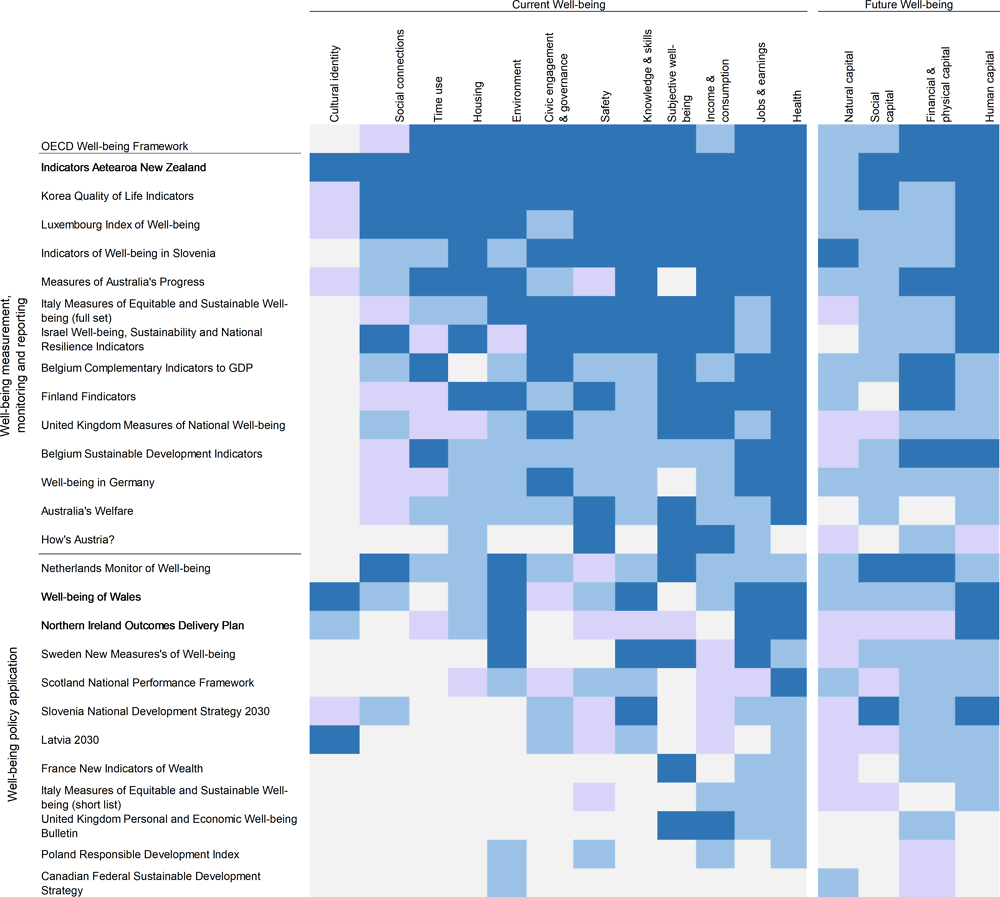

The Living Standards Framework’s conceptual underpinnings

The Living Standards Framework has undergone several iterations (Exton and Shinwell, 2018[38]). The December 2018 edition (Figure 1.1) is in line with international practice in terms of the dimensions and concepts covered (Figure 1.12, further down). For example, all existing national frameworks across the OECD feature well-being as a multidimensional construct, and take into account both objective and subjective aspects of people’s lives. Common domains of current well-being include income, jobs, housing, health, skills, safety, time use, environment, social connections and subjective well-being. The Living Standards Framework also reflects the specific New Zealand context, most notably through the inclusion of a cultural identity dimension, recognising New Zealand’s unique culture, including the partnership enshrined in the Treaty of Waitangi, multicultural origins and diverse immigrant population.

A comparative strength of the Living Standards Framework is that it makes a conceptual distinction between individual well-being outcomes “today” and the broader systems and means to sustain these over time (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[39]). Differentiating between current and future well-being helps to monitor whether a country is maximising the former at the cost of the latter, to clarify intertemporal trade-offs in policy design, and to emphasise the intergenerational character of well-being (Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi, 2009[40]; UNECE, 2013[41]; UNU-IHDP and UNEP, 2014[42]; OECD, 2015[43]) While several dashboards mix sustainability indicators with current well-being outcomes, only three other initiatives – the OECD Well-being Framework, Belgium’s Complementary Indicators to GDP and the Dutch Well-being Monitor – currently make explicit this distinction between current well-being and sustainability. In a further step, the Living Standards Framework also acknowledges the roles of risk and resilience, which are key components of a systems approach to sustainability that emphasises interactions among the four capitals, and their joint role in producing current well-being outcomes (De Smedt, Giovannini and Radermacher, 2018[44]).

Box 1.1. New Zealand’s long history of well-being measurement and evidence-building

Well-being measurement in New Zealand has a long history and spans multiple ministries and public bodies. As early as 2001, the Ministry of Social Development published its first Social Report (Ministry of Social Development, 2011[45]), with very similar domains to those for current well-being included in both the OECD approach and the Living Standards Framework Dashboard. The Social Report also strongly influenced the design of the biennial New Zealand General Social Survey, first fielded in 2008 to collect information about multiple well-being outcomes and their distribution across groups (Stats NZ, 2017[46]; Fleischer, Smith and Viac, 2016[47]).

Data availability expanded significantly in subsequent years, particularly in the social and environmental domains. In 2008 and 2010, Stats NZ produced two iterations of Measuring New Zealand’s Progress using a Sustainable Development Approach, building on the earlier Monitoring Progress Towards a Sustainable New Zealand Reports from 2002 and 2003 (Stats NZ, 2011[48]). In 2011, a paper by the Treasury provided a snapshot of New Zealand’s Living Standards (New Zealand Treasury, 2011[49]). Also in 2011, Stats NZ released the first prototype of its Integrated Data Infrastructure, a large database containing microdata about people and households from a wide range of government agencies, Stats NZ surveys and Census, as well as non-government organisations (Stats NZ, 2018[50]). This infrastructure provides a rich source of information for the Social Investment Agency, which strategically advises the government on improving outcomes for New Zealanders. Since its establishment in 2015, the Agency has produced various case studies on using a well-being approach to public policy, including on the well-being impacts of social housing (SIA, 2018[51]; SIA, 2018[52]; SIA, 2018[53]). The Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ launched their Environmental Reporting series the same year (Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ, 2015[54]).

The Treasury’s 2018 Living Standards Framework Dashboard is a natural extension and consolidation of this previous work. Stats NZ’s Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, is a further large-scale well-being and sustainability dataset due to be launched in mid-2019.

Broad-based stakeholder support for well-being frameworks is an important factor for their uptake and longevity. Public consultation has often played a role in the development of measurement frameworks in other countries (Table 1.1). The Treasury invited feedback on its Living Standards Framework Dashboard proposal by publishing it on its website. 500 responses were received, as well as 60 submissions from the business and NGO sectors, academics, individuals, and government agencies (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[37]). While this implies a high per capita response rate when compared to similar consultations in other countries, these remain relatively low numbers.4 Nevertheless, the Treasury was able to build on previous public outreach over the past four decades (e.g. consultations by the Royal Commissions on Social Security, as well as for the Ministry of Social Development’s Social Report, Stats NZ’s New Zealand General Social Survey, Measuring New Zealand’s Progress Using a Sustainable Development Approach, and the Environmental Reporting Series). In developing its well-being approach, the Treasury has been transparent in putting material, from discussion papers to the budget guidance and cost-benefit analysis tools, into the public domain (e.g. (King, Huseynli and Macgibbon, 2018[55]; Janssen, 2018[56]; Van Zyl and Au, 2018[57]; Frieling, 2018[58]; Morrissey, 2018[59]; Yong, 2018[60]; Tavita and Levi-Teu, 2018[61]; New Zealand Treasury, 2018[62]), providing a platform for engagement and debate within New Zealand, and a valuable resource for other governments.

From frameworks to measurement: the Living Standards Framework Dashboard

Across OECD countries, the shape and size of well-being frameworks, and the associated dashboards of indicators, have varied according to their use. Frameworks focused on monitoring and reporting typically involve building a large evidence base on the state of a country’s well-being (i.e. an indicator set) and making this information publically available.5 The goal of these diagnostic exercises is usually to provide a comprehensive account of how life is going for people, including trends over time and inequalities among population groups. At the other end of the spectrum, frameworks that have been developed for specific policy applications often have far fewer indicators, as in France, Italy and Sweden, where a small set of indicators are reported during budgetary discussions. The Living Standards Framework Dashboard falls in the middle of this spectrum (Figure 1.11). It covers 554 indicators, including a few indicators for each of the 12 domains of current well-being and the four capitals.6

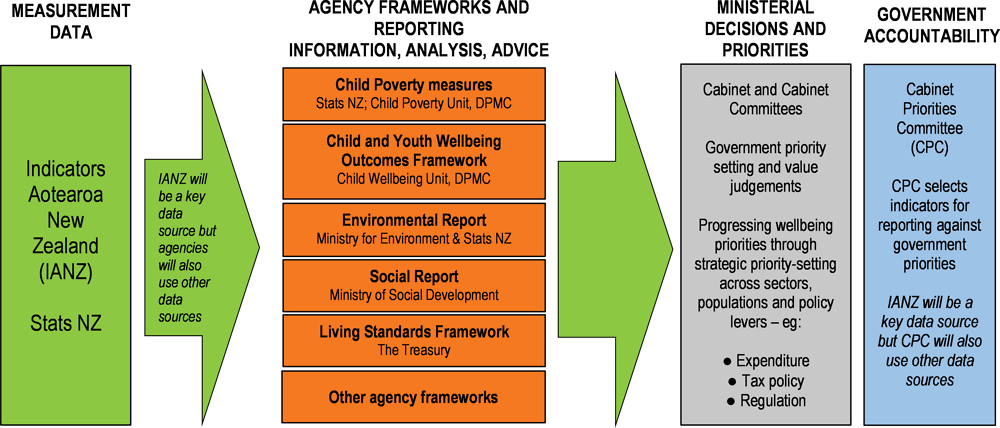

From mid-2019, Stats NZ’s Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand (IANZ) initiative is expected to provide a suite of nearly one hundred well-being and other contextual indicators (Stats NZ, 2019[63]). This places it among the larger indicator sets in OECD countries (Figure 1.11), alongside several other broad-based well-being monitoring initiatives from national statistical offices. When the IANZ and Living Standards Framework Dashboard begin to be published in parallel, it will be important to clarify their different functions and complementarities. In the future, the Treasury’s Dashboard, and the well-being approaches in several other New Zealand government agencies, are expected to draw from data provided in IANZ (see Figure 1.13, below). At the same time, some in-depth features of the Treasury’s Dashboard, such as international comparisons, are not expected to feature in the IANZ data set, and will need to be drawn from other sources of data and analysis.

The Dashboard’s indicator coverage is broadly consistent with that in other countries, but includes some gaps

The Living Standards Framework Dashboard is consistent with an emerging international consensus on the key “ingredients” of well-being: detailed content mapping of the Living Standards Framework dimensions and indicators against other well-being frameworks across the OECD shows a large degree of overlap, even if indicators are organised into domains in slightly different ways across countries (Figure 1.12).

Despite the overlap with other well-being frameworks, several themes and indicators consistently included in other countries’ approaches do not feature in the Living Standards Framework Dashboard (Table 1.2). A variety of factors may explain these differences, ranging from data availability issues, to conceptual issues, to the need for parsimony and to focus on areas of greatest importance in the New Zealand context. When the Dashboard was introduced, the Treasury noted that further work was needed in particular to integrate Te Ao Māori perspectives and concepts of well-being; to develop indicators for New Zealand cultural identity; and to recognise the critical role of child well-being in intergenerational outcomes (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[1]). In addition, the Treasury signalled the need for future work on the risk and resilience components of the framework, institutions, knowledge and skills, human capital, the environment and natural capital, and trade-offs among the domains.

Figure 1.11. The LSF Dashboard has a middling number of indicators

Number of indicators per well-being framework

Note: The number of indicators refers to unique headline indicators as of May 2019. Information on Stats NZ’s IANZ initiative is based on the proposed indicator list released on 9 April 2019.

Source: See StatLink for details of the data sources.

In an international context, areas where the Dashboard’s measurement gaps are greatest include natural capital, human capital and innovation (Table 1.2) (Fleischer, Frieling and Exton, forthcoming[6]). In some cases the data gaps in the current Dashboard mean that it is not reflecting existing indicators of high relevance, both to New Zealand’s well-being performance internationally, and to the five priorities set out for the 2019 Wellbeing Budget. For example, maintaining and protecting New Zealand’s unique natural capital base is of central importance for the sustainability of well-being and growth, as reflected in the priorities for the 2019 Budget (New Zealand Government, 2018[35]). Yet this is the area where the Treasury’s Dashboard deviates the most from practice around the OECD (Table 1.2).7 A further budget priority emphasises innovation, yet measures of investment in research and development or adult skills and lifelong learning, both of which feature in many other national well-being frameworks and speak to this priority, are currently absent.

Figure 1.12. The Living Standards Framework compared to other well-being frameworks

Comparison at the indicator level per Living Standards Framework dimension

Note: A dark blue shade indicates that 50% or more of the indicators included in the Living Standards Framework dimensions are also contained in the other well-being dashboard. Light blue indicates that less than 50% (but more than 0) are contained in the other well-being dashboard. Purple indicates that a dashboard includes the concept envisioned by the respective Living Standards Framework dimension, but in a very different way and with no comparable indicators. White indicates that the dimension of the Living Standards Framework is not covered in other frameworks. Only fully operationalised indicators (as of May 2019) are considered. Norway - How We Are Doing and the Finland Strategic Government Programme Indicators are not included as indicator details in English were not available.

Source: Fleischer, Frieling and Exton (forthcoming[6])

Table 1.2. Missing indicators commonly included in other well-being frameworks

Selected indicators not featured in the Living Standards Framework Dashboard

|

Indicator |

Other well-being frameworks featuring this indicator |

# Frameworks |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Natural capital |

|

OECD, Australia (MAP + Welfare), Austria, Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators), Canada, Finland (Findicators+ Government Programme Indicators), France, Germany, Italy, Korea, Latvia, Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being + National Development Strategy), Sweden, UK (Measures of National Well-being), Wales |

23 |

|

Australia (Welfare), Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators), Canada, Italy, Latvia, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being + National Development Strategy), Sweden, UK (Measures of National Well-being), Wales |

14 |

|

|

Canada, Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators), Finland (Findicators+ Government Programme Indicators), Latvia, Netherlands, Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, Scotland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being + National Development Strategy), UK (Measures of National Well-being), Wales |

13 |

|

|

Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators), Canada, Finland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being + National Development Strategy), Wales |

11 |

|

|

Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators), Korea, Latvia, Luxembourg, Northern Ireland, UK (Measures of National Well-being), Wales, Finland (Government Programme Indicators) |

9 |

|

|

Safety |

|

Australia (MAP + Welfare), Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators), Finland, Germany, Italy, Israel, Korea, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being + National Development Strategy), UK (Measures of National Well-being) |

17 |

|

Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators, Finland, Italy, Israel, Korea, Slovenia (Measures of Well-being) |

7 |

|

|

Human capital |

|

OECD, Australia (MAP), Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators, Finland, France, Italy, Israel, Korea, Netherland, Scotland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being), UK (Measures of National Well-being), Wales |

14 |

|

OECD, Australia (MAP + Welfare), Finland, Israel, Luxembourg, Netherland, Slovenia (Measures of Well-being) |

8 |

|

|

Austria, Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators), France, Italy, Korea, Latvia, Luxembourg, Northern Ireland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being) |

11 |

|

|

Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators), Italy, Israel, Finland (Government Programme Indicators), Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, Scotland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being), UK (Measures of National Well-being) |

9 |

|

|

Social capital |

|

OECD, Australia (MAP), Germany, Italy, Israel, Korea, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, UK (Measures of National Well-being), Wales |

12 |

|

Australia (MAP), Germany, Italy, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Slovenia (National Development Strategy) |

6 |

|

|

Financial and physical capital |

|

OECD, Australia (MAP), Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP), Canada, Finland (Findicators + Government Programme Indicators), France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Scotland |

12 |

|

Knowledge and skills |

|

OECD, Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP), Germany, Israel, Italy, Korea, Scotland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being + National Development Strategy) |

9 |

|

Time use |

|

Germany, Italy, Israel, Korea, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being), UK (Measures of National Well-being) |

10 |

|

Finland, Germany, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg, Netherland, Northern Ireland |

7 |

|

|

Social connections |

|

OECD, Australia (MAP + Welfare), Belgium (Sustainable Development Indicators), Italy, Israel, Korea, Latvia, Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, UK (Measures of National Well-being) |

10 |

|

Income and consumption |

|

Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP + Sustainable Development Indicators), Finland, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being) |

8 |

|

Jobs and earnings |

|

Australia (MAP), Germany, Italy, Israel, Korea, Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, Wales |

7 |

|

OECD, Italy, Luxembourg |

3 |

|

|

OECD, Belgium (Complementary Indicators to GDP), Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand |

3 |

|

|

Civic engagement and governance |

|

OECD, Australia (MAP), Germany, Scotland, Wales |

5 |

|

Health |

|

Australia (Welfare), Belgium (Sustainable Development Indicators), Luxembourg, Slovenia, UK (Measures of National Well-being) |

5 |

|

Housing |

|

Israel, Korea, Scotland, UK (Measures of National Well-being), Wales |

5 |

|

Australia (MAP + Welfare), Wales |

3 |

|

|

Subjective well-being |

|

Korea, Slovenia (Indicators of Well-being), UK (Measures of National Well-being) |

3 |

|

Cultural identity |

|

Northern Ireland, Wales |

2 |

|

Australia (MAP) |

1 |

Note: For Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand, only already developed indicators are listed.

Source: Fleischer, Frieling and Exton (forthcoming[6])

Natural capital measurement is a particularly challenging area in need of further investment. It is a domain that is poorly covered in the OECD’s well-being framework, strongly hindered by a lack of internationally comparable data, and by the very wide range of indicators needed to capture environmental resources and ecosystem services comprehensively (OECD, 2017[4]; OECD, 2013[64]; OECD, 2015[43]). Nevertheless, several international indicators are available, and OECD data indicate that New Zealand performs poorly relative to other countries in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and soil nutrient balance, while Stats NZ data indicate worsening nitrogen pollution in rivers, measures that are currently missing from the Living Standards Framework Dashboard (Fleischer, Frieling and Exton, forthcoming[6]; OECD, 2017[7]). Most other well-being frameworks in OECD countries include related indicators (e.g. greenhouse gas emissions, CO2 emissions, carbon footprint) and energy (e.g. share of energy renewably produced). Likewise, the Living Standards Framework Dashboard includes no information on the state of New Zealand’s protected areas. Although the Dashboard has measures of drinking water quality and water ‘swimmability’ (i.e. the share of tested river sites deemed safe to swim in under normal conditions), measures used elsewhere include nitrates/nutrient pollution in rivers and lakes, a particularly important issue in New Zealand (OECD, 2017[7]; New Zealand Treasury, 2011[49]).8

New Zealand is generally well-placed in terms of existing data infrastructure to fill some of these comparative gaps (Fleischer, Frieling and Exton, forthcoming[6]). Where these indicators are considered beyond scope by the Treasury, they could be considered for inclusion in other agency-specific frameworks (Figure 1.13), or in the forthcoming Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand dataset from Stats NZ – which is expected, over time, to address around half of the data gaps identified here (Stats NZ, 2019[63]). To ensure a good read-across with other international approaches, the international comparability of these measures will also be key.

Applying a well-being lens to policy in New Zealand

Implementing a well-being approach to policy

New Zealand is among a small but growing group of countries taking steps to embed well-being more deeply and systematically into policy processes (Exton and Shinwell, 2018[38]; Durand and Exton, 2019[65]). Since 2015, France, Italy and Sweden have each introduced well-being indicators in their budget deliberations. Slovenia, Scotland, Paraguay, Ecuador and Colombia have drawn on well-being evidence to inform their National Development Strategies and performance frameworks. Wales, the United Kingdom, Ecuador, Bhutan and the United Arab Emirates have each experimented with creating new institutional structures to champion well-being or to support a strengthening of the evidence base (such as Commissioner or Ministerial-level posts, or dedicated centres for gathering and disseminating evidence). The United Kingdom What Works Centre and Treasury have meanwhile provided analysts with methodological guidance and support to consider well-being impacts in ex ante appraisal and ex post evaluation of policy proposals and programmes.

Box 1.2. Well-being policy in New Zealand and the Living Standards Framework

The New Zealand Government has identified a broad range of changes to the public finance and state sector system that are needed to support its well-being vision. Some of these changes are led by the Treasury, often with implications for other ministries and agencies (e.g. the 2019 Wellbeing Budget), but others are led in other agencies (e.g. the Department for the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s Child Poverty and Well-Being work; Stats NZ’s Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand). The government’s well-being approach includes:

Embedding well-being in the Public Finance Act (1989). The current proposals will require the government to set out each year how its well-being objectives, together with its fiscal objectives, will guide its budget. The well-being objectives themselves will be set by the government of the day.

The 2019 Wellbeing Budget, in which well-being evidence was used to shape the Budget priorities (New Zealand Government, 2018[35]), as well as to assess budget bids from government departments (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[62]). Agencies were also strongly encouraged to collaborate when developing budget bids.

The Child Poverty Reduction Act, passed in late 2018, requires the government of the day to set long-term (10-year) and intermediate (three-year) targets on a defined set of child poverty measures, and to report annually on those measures. On Budget day, the government must report on progress towards its child poverty targets, and how measures in the Budget will affect child poverty. The Children’s Act 2014 was also amended to require successive governments to develop and publish a child and youth well-being strategy, with a particular focus on improving the well-being of all children and young people; children with greater needs; reducing child poverty and mitigating the impacts of child poverty and of socio-economic disadvantage experienced by children; and improving the wellbeing of the core populations of interest to Oranga Tamariki-Ministry of Children. This includes setting desired outcomes, actions to achieve them, and reporting on measures of progress (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2019[66]).

The Local Government (Community and Well-Being) Amendment Act (2019) reinstates wording that was previously included (from 2002-2012) in the Local Government Act, stating that the purpose of local government is to “promote the social, economic, environmental and cultural well-being of communities, in the present and for the future”.

Embedding well-being into agencies’ performance reporting. The government expects agencies to describe their contribution to improving inter-generational well-being. The Treasury is currently working with agencies to understand how best to embed a focus on intergenerational well-being in accountability documents. This is based on principles such as taking a longer-term view; thinking broadly about impacts, both positive and negative; working collectively towards shared outcomes; and recognising and building on existing frameworks, strategies or indicators. This ties into the government’s wider proposals to revise the State Sector Act (1992) and to enable a more coordinated, joined up public service.

The Treasury has been developing its Living Standards Framework since 2011. It was developed as a conceptual tool to support improvements in the quality of the Treasury’s advice through reminding Treasury analysts of the wider dimensions of well-being that should be taken into account when formulating policy advice, and in considering the trade-offs between alternative policy options (Au and Karacaoglu, 2015[67]; Exton and Shinwell, 2018[38]). Although not initially intended as a well-being measurement initiative, illustrative indicators were put forward for discussion, even in the early stages of developing the Framework (New Zealand Treasury, 2011[49]). The work has been stepped up since 2017 to support the government’s well-being approach:

The Living Standards Framework was updated in 2018, and a new Dashboard of well-being indicators was released. Amongst other uses, the Dashboard aims to complement the standard macroeconomic and fiscal reporting that the Treasury publishes as part of the Budget process. For example, the 2019 Budget Policy Statement included a “Wellbeing Outlook”, based on the Dashboard, to complement the standard Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

Proposed amendments to the Public Finance Act will require the Treasury to produce a periodic report on current and future well-being every four years (Institute of Public Administration New Zealand, 2019[36]).

The Treasury has also adopted a well-being approach in its longer-term statutory reporting. In the 2018 Investment Statement, which analyses the government balance sheet and its management, the Living Standards Framework provided an organising framework. The Statement, required at least every four years, also includes a chapter on how to broaden it to include natural capital considerations.

The Community for Policy Research was launched in November 2017 as a multidisciplinary network of external researchers whose work could be used to improve the advice of Treasury. To steer this, Treasury has published a short booklet listing its key research interests, clarifying the broad areas and research questions of greatest relevance to addressing priority gaps in the Treasury evidence base (New Zealand Treasury, 2017[68]).

Despite the different origins and context of the Living Standards Framework, New Zealand often faces policy implementation challenges similar to those in other countries. One challenge is simple awareness: communicating clearly what well-being is, how it can be measured, and why it matters for policy. The tools typically used to generate policy advice, and the theoretical and applied analysis on which these rest, are rarely centred on well-being, and often struggle consider economic, environmental and social impacts in an integrated way – even if recent work is beginning to turn this around. Well-being policy makes new demands on the evidence base, and the research response will take time to build. Much of the evidence will be generated outside of government departments, and perhaps even New Zealand itself, so evidence demands must be stated clearly, and communicated effectively. Signalling a long-term commitment to using well-being evidence will enable actors within the evidence pipeline to invest the long-term resources needed to meet these demands.

Further challenges include joining up across sectors, adopting a multidimensional approach to policy impact appraisal and evaluation that can forge collaboration across departmental silos, surfacing trade-offs and capitalising on synergies. The robustness of policy analysis tools must be maintained throughout, with good quality checks in place. Tackling these issues will require clear direction and leadership, continuous learning, and culture change, not only within government and the civil service, but also the wider community that shapes policy. These challenges, discussed in more detail below, should inform the next steps planned by the New Zealand Government, as well as the review and update of the Living Standards Framework and its Dashboard of measures, currently planned for 2021 (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[3]).

Building a joined-up well-being information system that can meet new policy needs

Good quality, timely, and comprehensive data play a crucial role in policy advice

The 2018 Living Standards Framework Dashboard represents an important step in consolidating well-being evidence for New Zealand. It draws data from several different sources including Stats NZ, the OECD, the Ministries of Health, Education, Environment and Justice. Despite some important data gaps (discussed above), a long tradition of measuring well-being in New Zealand means that The Treasury has a range of quality data to draw from (Box 1.1). The release of Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand by Stats NZ in mid-2019 will provide a key data source, feeding into the Living Standards Framework Dashboard and several other well-being reporting initiatives across government (Figure 1.13).

Figure 1.13. The anticipated Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand data pipeline

Source: New Zealand Treasury (2019), Presentation by Gabriel Makhlouf to the OECD, 22 January.

The steps being taken to implement a well-being approach across government (Box 1.2) place new demands on the statistical system, which is already under some strain (Stats NZ, 2018[69]). To build up the necessary well-being evidence base, data should be collected frequently, and reported in a timely manner. Doing so will provide policy makers with more rapid and regular information, as well as a richer source of material for the necessary research on critical policy levers. However, these demands are at odds with current statistical practice both in New Zealand and throughout the OECD, where well-being measures are often collected and reported with very low frequency and timeliness (Fleischer, Smith and Viac, 2016[47]). In New Zealand, the General Social Survey, a major source of well-being data, is conducted every two years. The Census, conducted every five years, is another important source. Time use data, critical for the Living Standards Framework’s time use domain, and for analysing unpaid work, leisure, social connectedness, cultural participation, health behaviours, etc. was last collected by Stats NZ in 2009/10, 11 years after the preceding data collection in 1998/99. In addition, around one-third of the proposed indicators for the Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand dashboard are currently still to be developed (Stats NZ, 2019[63]) – meaning that investment in new data sources and methods will be needed.

With any comprehensive well-being indicator set that aims to inform policy making, the cost burden of filling data gaps, providing more frequent and more granular data collections and more timely reporting must be considered. To help manage these pressures, it may be necessary for the government to identify a narrower set of top priority indicators (see below). Indeed, Stats NZ have stated their intention to select a core set of 20-25 indicators to provide a broad overview of progress, accompanied by 80-90 second tier measures in Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand (Stats NZ, 2018[70]). Some Stats NZ survey instruments, such as the Household Labour Force Survey and the Quarterly Employment Survey, are already fielded quarterly. The General Social Survey could be conducted on an annual, rather than two-yearly, cycle, and could incorporate some items currently only captured in the five-yearly Census. Additionally, Stats NZ should consider the use of administrative data and other Big Data sources. Some of these are already being explored in the context of the Census Transformation Programme (Stats NZ, 2019[71]).

A more joined-up approach to defining well-being is needed in government

The Living Standards Framework is a tool owned by the Treasury, rather than the wider New Zealand Government. Since it is neither a development strategy, nor a performance monitoring framework, it does not set specific goals or targets that unite government departments around a set of common objectives - an approach adopted in Scotland and Slovenia, for example, to galvanise government action and cooperation (Exton and Shinwell, 2018[38]; Durand and Exton, 2019[65]). The decentralised approach to well-being reporting in New Zealand, with several different frameworks and indicator sets operating in parallel, enables government ministries and agencies to tailor the breadth and depth of their analysis to the needs, audiences and policy problems at hand. Yet one important downside of this decentralised system is that there is no definitive account of New Zealand’s well-being – nor one consistent framework under which the different approaches are nested. For example, the “four well-beings” referred to in the Local Government (Community Well-being) Amendment Bill (Box 1.2, above) are quite different to the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework. The lack of coordination risks creating confusion among both stakeholders and the research community tasked with generating the evidence base, and will frustrate attempts to map indicators at the different levels of policy-making (Burton, Morrissey and Ng, 2018[72]). It also means that creating a more collaborative “whole-of-government” approach, another key objective for the current government, may become harder to realise.

Chief Executives across the public service should consider adopting a common conceptual framing of well-being – such as the Living Standards Framework - as an organising construct within which agency well-being frameworks can be nested. Greater clarity should also be provided on the respective roles of and connections between the approaches used in different parts of the public sector. This does not mean that all departments and agencies should adopt the same indicators as the Living Standards Framework Dashboard, since greater or less granularity may be required in specific domains. Nor would it necessarily mean covering all domains of the framework, since some may be of lesser relevance for a specific government agency. But it would mean that all indicator sets would be articulated in relation to one central framework, and stakeholders could easily understand how they interrelate. Although the Treasury did consult with other ministries, and the current approach builds on more than a decade of well-being work in New Zealand, the speed with which the current Living Standards Framework and Dashboard have been developed left little room to seek cross-government consensus. This goal should be pursued in the future, not least because the 2019 Wellbeing Budget already required all departments to use the Living Standards Framework in preparing their budget spending bids.

A small set of priority indicators could help raise awareness and focus attention

Comprehensive dashboards produced by independent public bodies, such as national statistical offices, are essential for general well-being monitoring. They also play an important role in ensuring that well-being is not defined as (or associated with) a narrow set of political priorities. Nevertheless, to capture the attention of senior leaders, politicians, media and the wider public, a smaller dashboard can be a valuable addition to larger diagnostic data sets (Jeffrey and Michaelson, 2015[73]; Kanbur, Patel and Stiglitz, 2018[74]; France Stratégie, n.d.[75]; Scott and Boyd, 2017[76]). This approach has been followed in a number of OECD countries. For example, implementation of the new budget laws in France and Italy resulted in 10 and 12 indicators respectively, while Sweden’s well-being dashboard, also presented to inform the budget process, contains 15.

The process for selecting small headline sets of indicators has varied across countries: in France, the 10 New Wealth Indicators were the product of public consultation, with final decisions then taken by the government; in Italy, decisions on 12 budget indicators were made by an expert committee established by the Prime Minister; in Sweden, Statistics Sweden developed the framework, in consultation with government offices (Exton and Shinwell, 2018[38]). In the United Kingdom, the national statistical office has released a new quarterly Personal and Economic Well-being Bulletin, which features 12 indicators (ONS, 2019[77]). The Welsh Government is currently undertaking a public consultation on a set of around 12 National Milestones, which will incorporate specific target levels (Welsh Government, 2018[78]), to complement its 46 measures of well-being (Table 1.1, above). One critical input in this selection should be key findings from the larger-scale well-being monitoring dashboards, which in New Zealand would be the Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand data set and the current Living Standards Framework Dashboard. Without these, priority selection will have less of an empirical basis, and be less transparent (Fleischer, Frieling and Exton, forthcoming[6]).

The well-being objective-setting that the New Zealand Government would be required to undertake in the currently proposed amendments to the Public Finance Act (Institute of Public Administration New Zealand, 2019[36]) could be accompanied by a set of priority headline indicators. These could in turn provide the basis of the annual reporting required under the proposed amendments. In the more immediate future, the five priorities set out for the 2019 Wellbeing Budget (New Zealand Government, 2018[35]) could provide one stimulus for a smaller set of indicators – though (particularly in light of the current frequency and timeliness of well-being data) these should be adopted for a longer time horizon, rather than an annual budget cycle. For example, the targets required by the new Child Poverty Reduction Act (New Zealand Parliament, 2018[79]), which must span both medium (three-year) and longer term (ten-year) timeframes, will provide clear focus and accountability over what should be realistic time horizons for policy-related changes to occur.

Adapting the policy toolkit to put well-being at the centre

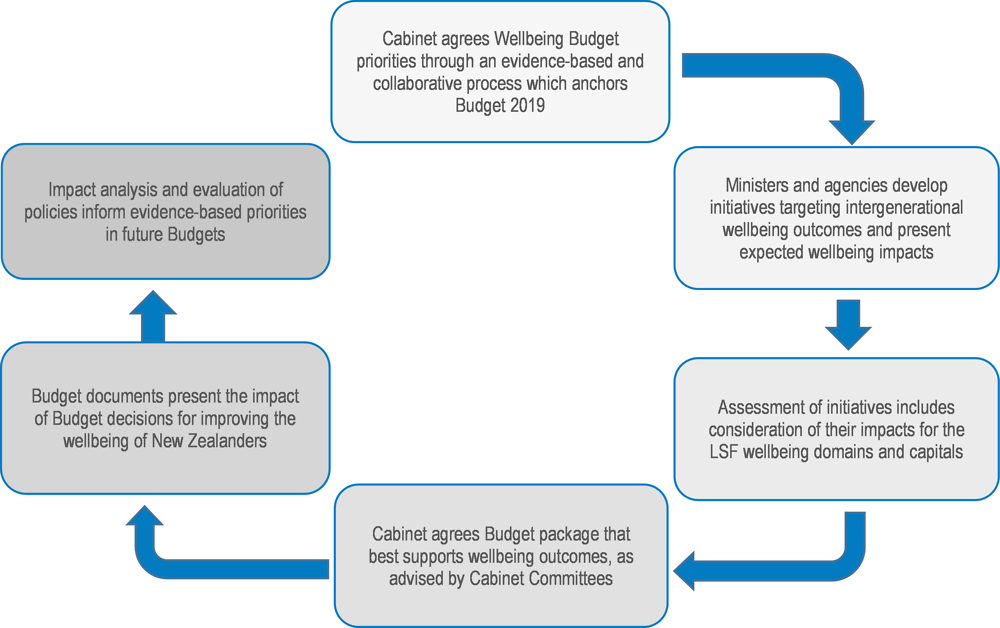

The budget process is a key mechanism to operationalise a well-being approach

New Zealand’s 2019 Budget aims to use well-being evidence at every stage of the cycle, from setting priorities to evaluating results (Figure 1.14). Since the budget process engages all government departments, it offers a lever for capacity-building among analysts across the public service, and a way to forge more collaborative approaches and evidence-sharing. It also has the potential to generate savings through reconciling misaligned bids; consolidating those bids that should produce strong synergies in terms of outcomes; and, by looking across a number of bids that all impact on the same well-being outcome(s), choosing the one(s) associated with the strongest evidence and greatest impacts. The impact of greater alignment can be substantial. For example, the Treasury has assessed that, even under highly restrictive assumptions, better aligning policy could be fiscally equivalent over 40 years to raising the age of eligibility for the state pension by two years (Burton et al., 2016[80]).

Figure 1.14. New Zealand's Wellbeing Budget process

Source: New Zealand Government (2018), Budget Policy Statement, Budget 2019, www.budget.govt.nz/budget/2019/fiscal-strategy/bps2019.htm.

To support the 2019 Budget, the Treasury required all initiatives seeking new funding to include a well-being analysis and intervention logic. First, the template for funding proposals asked departments to quantify how their initiative is expected to impact on twelve current well-being domains (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[62]). Not every domain of current well-being was assessed for every initiative: departments were instead asked to outline one primary and up to three secondary well-being domains impacted. The template also required a description of who is affected; the magnitude of the impact; the timeframes in which the impact will be realised; and a description of the evidence base and quality. In addition, initiatives were assessed on whether they were expected to “increase”, “decrease” or “maintain” each of the four capital stocks. Finally, departments were also asked to consider whether initiatives help to build resilience or respond to risks to well-being.

Guidance to agencies submitting bids indicated that initiatives that align with one or more of the five Budget 2019 priorities, and show cross-agency and cross-portfolio collaboration, would be prioritised. As is commonly found in budgets across the OECD, a majority share of New Zealand’s budget is reserved for baseline spending, which limits the discretionary funds available for new initiatives. New spending announced in the 2019 Wellbeing Budget constitutes only around 4% of core Crown expenditure. One of the Treasury’s future challenges will therefore be to develop approaches for reviewing how effectively the baseline spending of government agencies supports New Zealanders’ well-being. As a first step in the 2019 Budget, each Minister was asked to undertake a review of spending and identify at least 1% of baseline spending that is not aligned with the government’s aims, or is of lowest priority.

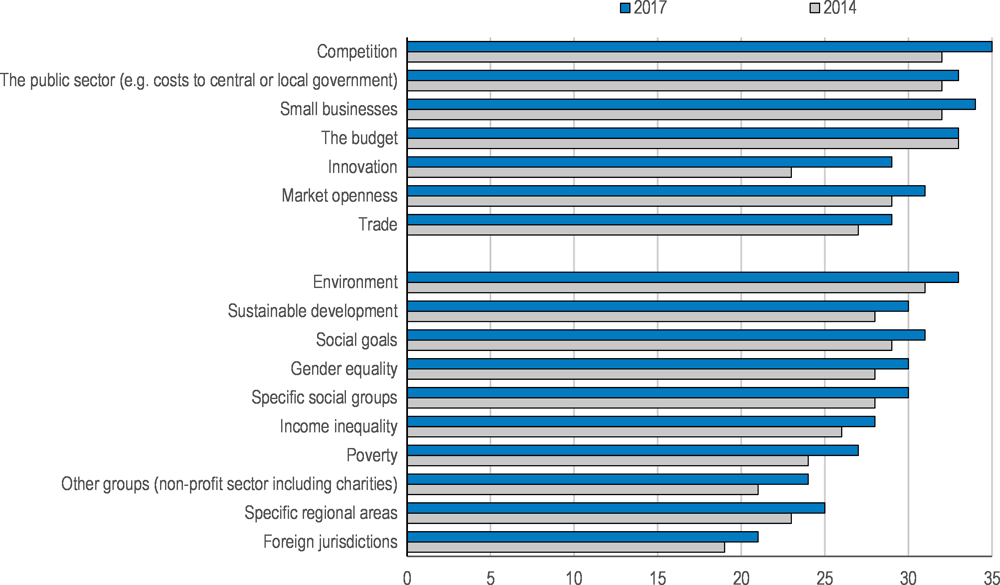

Existing policy tools already account for several aspects of people’s well-being, albeit unevenly

While France, Italy and Sweden have each recently introduced new dashboards of well-being indicators in their budget processes, the approach taken in New Zealand is a much more comprehensive and integrated one than seen elsewhere to date. Nevertheless, several countries have started to address the question of how to go beyond GDP when performing ex ante policy appraisal and ex post policy evaluation. For example, international practice on regulatory impact assessments has seen a gradual shift towards considering the wider benefits and costs of regulation (Figure 1.15). Nevertheless, economic impacts, such as on competition and small businesses, impacts on the environment, and on the public sector and budget remain the most frequently assessed types of impacts. The analysis of social impacts, such as income inequality and poverty, is expanding but not as developed (OECD, 2018[81]; Deighton-Smith, Erbacci and Kauffmann, 2016[82]).

In New Zealand, regulatory impact assessments are a formal Cabinet requirement for regulatory changes (OECD, 2016[83]). The Treasury provides guidance and quality assurance of this process, including periodically commissioning independent reviews (OECD, 2015[84]). New Zealand’s response to the OECD Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2017 indicated that each of the impacts in Figure 1.15 are assessed for some primary laws and subordinate regulations, but none are required to be assessed for all regulations. The templates provided for the purposes of impact assessment (New Zealand Treasury, 2017[85]) are very flexible: they require a statement about who is affected and how, as well as a summary of costs and benefits, and a description of stakeholder views, but there are no mandatory requirements to consider impacts for specific groups of citizens (e.g. by gender or ethnicity), or to assess equity concerns (e.g. income inequality) or specific outcomes (e.g. environmental or health impacts). The accompanying guidance (New Zealand Treasury, 2017[86]) notes that relevant impacts can include economic, fiscal, compliance, social, environmental and cultural impacts, but no further advice is provided on what social, environmental and cultural impacts are or how they might be considered.

Figure 1.15. Regulatory impact assessments in OECD countries are increasingly considering a wider range of impacts

Number of OECD jurisdictions considering impacts for at least some regulations

Note: Data is based on responses to the OECD Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, from 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2018), Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.